Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 13

February 12, 2022

On two new Macbeths: a playfully intense Bengali web-series and an austere American film

Wrote a short piece about Macbeth adaptations for India Today, centering on the two most recent ones: The Tragedy of Macbeth (gorgeous-looking film, though I had a few reservations about it) and the Bengali series Mandaar, which sags a bit in the mid-section but makes some very interesting choices

-----------------------------------

Everyone in the coastal village of Geilpur smells of fish, someone observes in the new Bengali series Mandaar. “And I’m a cat. Meow!” replies a newly arrived cop named Mukaddar, speaking in effete-sounding English. In another scene he liberally pours ketchup over the catfish on his plate, a culinary travesty.  On the face of it, such moments don’t belong in a Macbeth adaptation, but then those fish do appear to be “stepped in blood”, and Mukaddar (played by director Anirban Bhattacharya) is a stand-in for Shakespeare’s Macduff – a more corrupt and lecherous version. Mandaar nicely recasts the play’s characters. Mandaar/Macbeth (Debasish Mondal) is a strongman who works for a local leader, and whose impotence is a source of frustration for his wife, the sensuous Laili (Sohini Sarkar), obsessed with having a child. The story’s equivalent of the young prince Malcolm is a tantrum-throwing kid who wears a Che Guevera T-shirt one day and a Tom & Jerry shirt the next.

On the face of it, such moments don’t belong in a Macbeth adaptation, but then those fish do appear to be “stepped in blood”, and Mukaddar (played by director Anirban Bhattacharya) is a stand-in for Shakespeare’s Macduff – a more corrupt and lecherous version. Mandaar nicely recasts the play’s characters. Mandaar/Macbeth (Debasish Mondal) is a strongman who works for a local leader, and whose impotence is a source of frustration for his wife, the sensuous Laili (Sohini Sarkar), obsessed with having a child. The story’s equivalent of the young prince Malcolm is a tantrum-throwing kid who wears a Che Guevera T-shirt one day and a Tom & Jerry shirt the next.

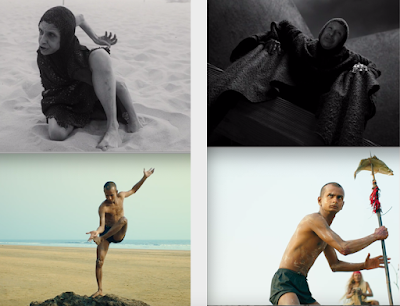

After setting things up with a striking version of the “Fair is foul and foul is fair” opening, this five-episode series meanders for a while – but it soon builds in intensity again, with some powerful scenes such as one where Mandaar, beset by ghostly visions, pursues Pedo, the weird young boy who is one of the “witches”. Or a nightmare shot in desaturated colours, emphasising the redness of the characters’ clothes while rendering much else monochrome. More than any of Shakespeare’s other works, “the Scottish Play” (as it is sometimes called for superstitious reasons) has been brought to the screen across different cultures and milieus. What is it about Macbeth that so appeals to filmmakers, from legends such as Orson Welles, Akira Kurosawa and Roman Polanski to the makers of today’s web-series? Perhaps it’s the unforgiving darkness of the story (both protagonists, Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, commit crimes and descend into crippling paranoia or guilt; the other tragedies have important sympathetic characters who provide a moral compass, like Ophelia, Desdemona or Cordelia). Or it could be the many setpieces that make for such powerful imagery, such as Lady Macbeth’s hand-washing. Or the witches: nearly every movie version has found an inventive way to depict them – most amusingly perhaps in Vishal Bhardwaj’s Maqbool, where two gossipy cops fill in for the prophesying crones.

More than any of Shakespeare’s other works, “the Scottish Play” (as it is sometimes called for superstitious reasons) has been brought to the screen across different cultures and milieus. What is it about Macbeth that so appeals to filmmakers, from legends such as Orson Welles, Akira Kurosawa and Roman Polanski to the makers of today’s web-series? Perhaps it’s the unforgiving darkness of the story (both protagonists, Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, commit crimes and descend into crippling paranoia or guilt; the other tragedies have important sympathetic characters who provide a moral compass, like Ophelia, Desdemona or Cordelia). Or it could be the many setpieces that make for such powerful imagery, such as Lady Macbeth’s hand-washing. Or the witches: nearly every movie version has found an inventive way to depict them – most amusingly perhaps in Vishal Bhardwaj’s Maqbool, where two gossipy cops fill in for the prophesying crones.

Even last year’s Malayalam film Joji, though only tenuously inspired by Macbeth, does witty things with some of the play’s iconic moments: with the story playing out in Covid time, the instruction “Put on a mask and go there” is a practical one, but also a nod to the many mask references (“False face must hide what the false heart doth know”) in the original work.

On one hand, non-Anglophone adaptations like Mandaar and Joji provide their own spins on Shakespeare’s prose and on key passages: take the use of Noh theatre elements in Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood, which brings a still, eerie quality to scenes such as the appearance of Banquo’s ghost. On the other hand, there are English-language versions that offer straightforward treatments of the verse but present familiar scenes in new ways. The latter type of film is currently represented by Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth, so stunningly shot in black-and-white that the over-used cliché “every frame looks like a painting” really seems to apply here. An alienating, dread-filled atmosphere is created by the framing and set design, which includes giant hallways and endless corridors; in their introductory scenes, characters walk from a distance right up to the camera, as if inviting us into a private abyss.

And yet, even a “pure” Macbeth like this one can have off-kilter moments that take licence with Shakespeare’s words. In the scene where Macbeth thinks he sees a dagger directing him towards Duncan’s room, the illusory weapon is presented as a bright vertical shape on a door far away, and his physical gestures don’t quite match the words of his soliloquy – which adds to the viewer’s dislocation. “Come, let me clutch thee,” Macbeth says to the dagger, followed by “I have thee not and yet I see thee still.” The directors who have tried to bring this strange, haunting play to the screen must often have felt the same way about their elusive source material.  P.S. One thing these two works have in common: two very supple witches. Kathryn Hunter’s performance as the Three Witches in The Tragedy of Macbeth has understandably won a lot of praise (though I wish she had more screen time) – known for her physical agility over a distinguished stage career, she brings an astonishing, crab-like flexibility to the role that makes her graceful and creepy at the same time. (You can easily turn the sound off, forget about the verse, and just watch her.) And in Mandaar, Sudeep Dhara plays the young Pedo, the companion of the “head witch” – lithe, loose-limbed, this character features in some of the most unsettling scenes in the series.

P.S. One thing these two works have in common: two very supple witches. Kathryn Hunter’s performance as the Three Witches in The Tragedy of Macbeth has understandably won a lot of praise (though I wish she had more screen time) – known for her physical agility over a distinguished stage career, she brings an astonishing, crab-like flexibility to the role that makes her graceful and creepy at the same time. (You can easily turn the sound off, forget about the verse, and just watch her.) And in Mandaar, Sudeep Dhara plays the young Pedo, the companion of the “head witch” – lithe, loose-limbed, this character features in some of the most unsettling scenes in the series.

February 9, 2022

Reader’s Digest memories (plus a piece about The Lost Daughter and The Power of the Dog)

Over the past two or three years, I have done some tiny “reviews” for Reader’s Digest India. I don’t usually share them here since these are far from in-depth pieces (or even decent-sized Facebook posts), they are snippets with very basic observations – but it’s still always cool to see my byline in a magazine that was such a fixture in my house when I was growing up: a respectable-seeming “international” publication that parents and grandparents used to read (and I used to flip through for the Laughter the Best Medicine and Life’s Like That pages, full of mostly anodyne jokes with one or two gems here and there).  In the current issue, I have a two-pager (still a short piece, but 550 words is better than 270 words) about two excellent recent films, The Lost Daughter and The Power of the Dog – touching on how both, in different ways, are about societal expectations and gender straitjackets. (The piece is pasted at the end of this reminiscence.) But it was only when I bought a copy of the issue that I realised it was a 100th anniversary special – which of course makes it even more pleasing to have my name in it. It also got me remembering a period in 1991-92 when I was obsessed with old American and British cinema, and gathered a lot of information (this being pre-internet) about some of my favourite actors/directors from the old Reader’s Digests that my grandparents had lying around in their Panchshila Park house. Many of them had special features on people like Orson Welles and Laurence Olivier and Barbara Stanwyck – unremarkably written but often a treasure trove of anecdotes or biographical information.

In the current issue, I have a two-pager (still a short piece, but 550 words is better than 270 words) about two excellent recent films, The Lost Daughter and The Power of the Dog – touching on how both, in different ways, are about societal expectations and gender straitjackets. (The piece is pasted at the end of this reminiscence.) But it was only when I bought a copy of the issue that I realised it was a 100th anniversary special – which of course makes it even more pleasing to have my name in it. It also got me remembering a period in 1991-92 when I was obsessed with old American and British cinema, and gathered a lot of information (this being pre-internet) about some of my favourite actors/directors from the old Reader’s Digests that my grandparents had lying around in their Panchshila Park house. Many of them had special features on people like Orson Welles and Laurence Olivier and Barbara Stanwyck – unremarkably written but often a treasure trove of anecdotes or biographical information.

Some memories of reading those articles are still very vivid: for instance, it was from a Reader’s Digest interview of Sophia Loren that I first learnt that Cary Grant had died in 1986. The piece had Loren mentioning that Grant, decades after he had proposed to her, phoned her unexpectedly one night to ask how she was doing, and to chat generally; and that he died the next day. (It was a bit of a shock: Grant had always seemed so alive and so timeless in the films of his I had watched, like The Awful Truth and Arsenic and Old Lace and Bringing up Baby; of course I knew he would have been in his eighties or nineties if he were still around, but to see the words coldly printed in the article was another matter.)

Then there was the Olivier piece, with a photo of him looking much younger than I had ever seen him, a still from Wuthering Heights where he played Heathcliff to Merle Oberon’s Cathy. (This piece also had a very exciting, possibly apocryphal account of David O Selznick seeing Vivien Leigh for the first time when she visited the sets of pre-production Gone With The Wind with Olivier – the burning of Atlanta was being filmed, Selznick saw her profile by the light of the flames – and knew she was Scarlett.) I have some of those issues stored somewhere, should look for them.

Here is the Lost Daughter/Power of the Dog piece. Written when it looked like Maggie Gyllenhaal had a good chance of being nominated as best director – sadly she wasn’t…

******

Among the cinematic highlights of the past few years have been a number of films helmed by women (take Chloé Zhao’s much-feted Nomadland), and two of the more recent ones are heavily favoured for Oscar nominations this month. If, as seems probable, both Jane Campion (The Power of the Dog) and Maggie Gyllenhaal (The Lost Daughter) are nominated for best director, it will be the first time in Oscar history that two women will compete in that category. While Campion is a respected veteran, Gyllenhaal – better known as an actress – is a first-time director. But this gap in experience aside, some things are common to their films.

Both are immersive works that reward patient viewing – they demand (and deserve) viewers with the willingness to grasp the dramatic beats and the revelation of character that occur during scenes where not much appears to be happening at a plot level. Also, both stories are – in different ways – about parents and children, responsibilities and burdens, and about the societal expectations and gender straitjackets that can encase women and men. Early in The Lost Daughter, during what’s meant to be a working vacation in Greece, the middle-aged protagonist Leda (Olivia Colman) sees a family crisis unfold: a young woman is looking for her little daughter who has vanished. The child turns out to be safe, but for a few dreadful moments it seems possible that she may have wandered deep into the sea. And we get flashbacks – through Leda’s perspective – to her own youth, and to a daughter, Bianca, who was similarly lost on a beach.

Early in The Lost Daughter, during what’s meant to be a working vacation in Greece, the middle-aged protagonist Leda (Olivia Colman) sees a family crisis unfold: a young woman is looking for her little daughter who has vanished. The child turns out to be safe, but for a few dreadful moments it seems possible that she may have wandered deep into the sea. And we get flashbacks – through Leda’s perspective – to her own youth, and to a daughter, Bianca, who was similarly lost on a beach.

At this stage, it seems possible that Leda’s child might have been lost forever (a little while later we see her speaking on the phone to her other daughter; Bianca’s fate is still up in the air). But The Lost Daughter doesn’t centre around a single dramatic incident – the mystery at its heart is more measured, and concerns a woman’s reflections on her struggles and choices. In further flashbacks, we see the younger Leda feeling frustrated and tethered as she tries to balance her work life – she wants to feel valued in her work as an academic – with looking after her little daughters; in the present day, the older Leda says “I was selfish […] I was an unnatural mother.” But the film raises the question: is it so selfish or unnatural to want to be one’s own person, to dream for oneself, even while being a parent? Filial relationships also lie at the heart of The Power of the Dog, in which the lives of a sensitive young man named Peter and his widowed mother Rose are affected when she remarries and her new husband’s brother Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch) is sneering and resentful of their presence. But an unusual dynamic develops between the seemingly predatory Phil and his main target, the “effeminate” Peter. We get glimpses of the former’s past, and realise that he is tormented by memories of a mentor who may have been both a father-figure and a lover. The hyper-masculine character soon turns out to have weak spots and demons, while the shy young man shows new dimensions too.

Filial relationships also lie at the heart of The Power of the Dog, in which the lives of a sensitive young man named Peter and his widowed mother Rose are affected when she remarries and her new husband’s brother Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch) is sneering and resentful of their presence. But an unusual dynamic develops between the seemingly predatory Phil and his main target, the “effeminate” Peter. We get glimpses of the former’s past, and realise that he is tormented by memories of a mentor who may have been both a father-figure and a lover. The hyper-masculine character soon turns out to have weak spots and demons, while the shy young man shows new dimensions too.

To reveal more about the plots of these two works would be a disservice, because in a sense they are both slow-burn suspense films – you might even call them psychological thrillers. However, more than an exciting climactic revelation, the suspense here involves what we learn about people, their relationships and their capabilities. And it’s hard to escape the feeling that the quietly observant quality of these films comes from the women’s touch behind the camera.

February 7, 2022

Sports movies are too "filmi"? Think again

My Economic Times column, which I couldn’t resist turning into a small tennis tribute after last week’s Australian Open final (which I think was Rafa Nadal’s greatest win ever, given the circumstances and his age/mileage). Have written much longer tennis pieces than this elsewhere, of course…

-------------------------------------

We know about the many clichés of the mainstream sports film: the underdog’s journey told through a hyper-dramatic lens, with the piling up of obstacles, the fall from grace, the comeback, the last shot at redemption. And then the improbably down-to-the-wire finale involving the penalty goal that must be taken, or the six runs needed off the last ball, or the rare wrestling manoeuvre executed with a mere second left.  The movie’s overall tone might of course vary: here, from pre-liberalisation Hindi cinema, is a fresh-faced Aamir Khan hitting a six to seal a win (while helicopters and gun-toting villains and a nodding Dev Anand decorate the skies above the stadium) in the cheesy Awwal Number; and here is a portlier Aamir nearly three decades later in the more gritty Dangal, locked in a room while his daughter-protégé pulls off that complicated five-pointer. But the basic principle holds. Watching an inspirational film in this genre means suspending disbelief at some point, accepting that the climax isn’t meant to be realistic but cathartic and rousing in a way that good melodrama can be.

The movie’s overall tone might of course vary: here, from pre-liberalisation Hindi cinema, is a fresh-faced Aamir Khan hitting a six to seal a win (while helicopters and gun-toting villains and a nodding Dev Anand decorate the skies above the stadium) in the cheesy Awwal Number; and here is a portlier Aamir nearly three decades later in the more gritty Dangal, locked in a room while his daughter-protégé pulls off that complicated five-pointer. But the basic principle holds. Watching an inspirational film in this genre means suspending disbelief at some point, accepting that the climax isn’t meant to be realistic but cathartic and rousing in a way that good melodrama can be.

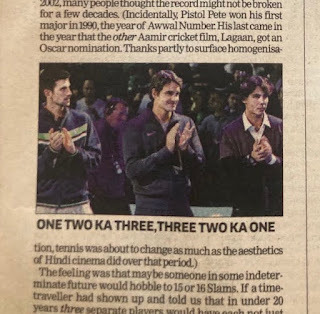

But if we are discussing the absence of “realism” in a fictional movie, one might ask: how much of the Federer-Nadal-Djokovic super-era in men’s tennis has been plausible? Speaking as an obsessive Rafa Nadal fan (but also as a grudging admirer of Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic – AND an appreciator of a dozen superb players who have achieved much less than these three, Andy Murray, David Ferrer and Stan Wawrinka among them): one consequence of following tennis in the past decade and a half is that my ideas about the dramatic tropes of sports movies have shifted.

Speaking as an obsessive Rafa Nadal fan (but also as a grudging admirer of Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic – AND an appreciator of a dozen superb players who have achieved much less than these three, Andy Murray, David Ferrer and Stan Wawrinka among them): one consequence of following tennis in the past decade and a half is that my ideas about the dramatic tropes of sports movies have shifted.

Consider that when Pete Sampras won his record-extending 14th Slam just before retiring, many people thought the record might not be broken for a few decades. (Incidentally, Pistol Pete won his first major in 1990, which was the year of Awwal Number. His last came in 2002, the year that the other Aamir cricket film, Lagaan, got an Oscar nomination. Thanks partly to surface homogenisation and increased media interest, tennis was about to change as much as the aesthetics of Hindi cinema did over that period.) The feeling then was that when Sampras’s record was broken, maybe someone would hobble to 15 or 16 Slams, in the same underwhelming way that Kapil Dev got to 432 Test wickets.

If a time-traveller had shown up on a primitive tennis forum in September 2002 and told us that in under 20 years THREE separate players would have each not just raced past Sampras but added six more Slams to the tally – continuing to look fit and hungry in their mid-thirties – this oracle would be laughed out of the chat-room, and possibly reported for being a dangerous lunatic. And that would have been the absolutely correct response.

Which is another way of saying that the stories and the twists involved in the tennis “trivalry” of the past 16 years could make up a dozen or more sports films – most of which would be dissed for being over the top (assuming they were greenlit in the first place). There isn’t enough space here to list the many ebbs and flows, but there have been personality conflicts and redemptive wins, kingdoms lost and regained, astonishing returns from injuries, and scarcely believable five-set epics (in the past year, both Nadal and Djokovic won major finals after being two sets down against much younger, fresher opponents). There have been many bizarre coincidences and symmetries too: last week Nadal won the second-longest Slam final of the Open Era exactly 10 years to the day after he had lost the longest Slam final on the very same court.

In the social-media age, there has been unprecedented fan madness and continuous shifts in our perceptions of these champions: in the early years, Nadal was the underdog trying to dethrone the universally loved Federer; in later years that mantle fell on Djokovic, whose fans, more than any other fan base, enjoy nurturing their victimhood. There was the “Novax” rumble that saw Djokovic kept out of the Australian Open because of his non-vaccinated status, and the absurdity of his father likening him to the slave leader Spartacus in an interview. You couldn’t make some of this up. And yet, for all the craziness of the matches and the career ups and downs, watching Nadal after the final last week – with his characteristic level-headedness and the refusal to participate in the foolish “GOAT debate” that too many tennis fans and journalists are obsessed with – was to be reminded that there is a lower-key film playing parallelly to the hyper-dramatic one. For all the adrenaline and the fist-pumping, Nadal off the court is a bit like the working-class protagonist of a Ken Loach film, pragmatic, cautiously hoping for the best. It’s as if Sylvester Stallone staggered out of the ring, bruised and sweaty and grimacing, and morphed into Amol Palekar, smiling shyly and speaking tentative sentences. Who would be silly enough to script something like that?

And yet, for all the craziness of the matches and the career ups and downs, watching Nadal after the final last week – with his characteristic level-headedness and the refusal to participate in the foolish “GOAT debate” that too many tennis fans and journalists are obsessed with – was to be reminded that there is a lower-key film playing parallelly to the hyper-dramatic one. For all the adrenaline and the fist-pumping, Nadal off the court is a bit like the working-class protagonist of a Ken Loach film, pragmatic, cautiously hoping for the best. It’s as if Sylvester Stallone staggered out of the ring, bruised and sweaty and grimacing, and morphed into Amol Palekar, smiling shyly and speaking tentative sentences. Who would be silly enough to script something like that?

February 5, 2022

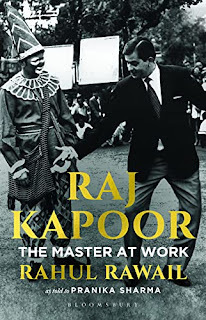

Raj Kapoor: The Master at Work – Rahul Rawail on his mentor

(In this week’s India Today, my review of Rahul Rawail’s chatty new book about his "Raj uncle" who became "Raj sahab")

-----------------

The first time Rahul Rawail – aged barely 16 – saw Raj Kapoor in action on a film set, “it was like watching him conduct a symphony”. This experience was followed by many others of its type. “I saw the Immortal Master weave his magic”, he tells us in this book’s prologue; later descriptions include “the puppeteer who deftly manipulated the strings”, “the one man who was the epicenter of Indian cinema”, and “the most distinguished filmmaker and the world’s most competent teacher”. Rawail, a childhood friend of Rishi Kapoor, began assisting Raj Kapoor on Mera Naam Joker, and went on to work on Bobby – two films, very different in content, tone and scale, that represented a transitional period in RK’s career. Mera Naam Joker was not only his pet project, a grand epic (some would say grand folly), but also the last film he directed where he played the lead role, and its commercial failure cemented the passing of an age. Bobby, a teenage love story which became a superhit, represented a new beginning centred around a new generation. Rawail was around for both (as well as the RK productions Kal Aaj aur Kal and Dharam Karam), and he provides many inside stories, both about the making of these films and more generally about Raj Kapoor’s working methods, quirks, and his knowledge of the many departments of filmmaking.

Rawail, a childhood friend of Rishi Kapoor, began assisting Raj Kapoor on Mera Naam Joker, and went on to work on Bobby – two films, very different in content, tone and scale, that represented a transitional period in RK’s career. Mera Naam Joker was not only his pet project, a grand epic (some would say grand folly), but also the last film he directed where he played the lead role, and its commercial failure cemented the passing of an age. Bobby, a teenage love story which became a superhit, represented a new beginning centred around a new generation. Rawail was around for both (as well as the RK productions Kal Aaj aur Kal and Dharam Karam), and he provides many inside stories, both about the making of these films and more generally about Raj Kapoor’s working methods, quirks, and his knowledge of the many departments of filmmaking.

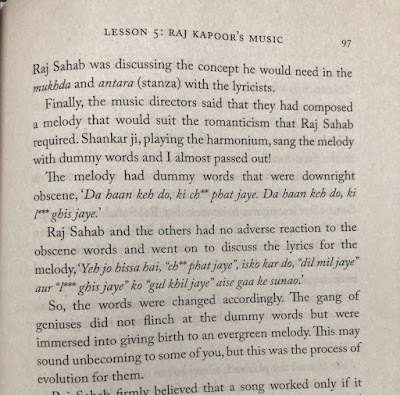

Here are anecdotes about RK as technician, editor, teacher, director of actors… and as gourmand too, a running theme being his love for food, which led him to go out of his way to catch the Deccan Queen to Pune so he could enjoy the train’s distinct meals. (The long editing sessions, we learn, began with everyone spending over an hour deciding on the vast menu for breakfast, lunch and dinner.) Here also are accounts of the “Dambara nights”, where iconic scenes from RK films were screened, and of musical addas that involved the substitution of obscene “dummy lyrics” while putting together what eventually became gentle, timeless songs. There are analyses of scenes such as the “trilateral shot” featuring the three protagonists in the Sangam climax. And there are entertaining asides about the eccentricities of the actor Prem Nath (Raj Kapoor’s brother-in-law), who, going by his appearances here, could well have been a memorable comic figure in a fictional work.

In terms of writing and structuring, The Master at Work is very uneven, with more than a fair share of typos – starting with the very first sentence of a Foreword where the word is spelt "forward" – but its strength lies in the personal, conversational tone. Biographical works are frowned upon when they treat their subjects with dewy-eyed reverence, but this book wasn’t intended as an objective study – the lens (or the POV) is a very intimate one. Besides, though Rawail is consistently respectful of his mentor, reading between the lines one gets a sense of humility and hubris, pride and self-deprecation, jostling against each other in RK’s personality – something that has been discussed in other studies, such as Madhu Jain’s book The Kapoors.

RK Studios, where Rawail began his apprenticeship, was a shrine for the youngster who would later become a director himself – helming some notable films of that unfairly-maligned decade, the 1980s, such as Arjun and Dacait. Importantly, then, this book is partly about Rawail as well, and not just because it ends with a few chapters about his own, RK-influenced work, including a candid account of his clashes with actor-producer Rajendra Kumar during the making of the 1981 Love Story.

Contemporary Indian film literature – the anecdotal or gossipy variety anyway – is so full of repetition, of familiar stories recycled, that it’s sometimes just a relief to come across a singular perspective. At one point Rawail tells us that even today when he watches the party scene in Bobby, all he can see is two junior artistes gobbling up expensive pista and badaam that had been provided in rationed quantities, an incident which caused him much stress during the shoot. It’s the sort of observation that you could only possibly find in this book, and there are many others like it. If this is what a hagiography can be like, bring on a few more. P.S. from the book – here is an account of the composition of a Mera Naam Joker song that wasn’t used. (Those with delicate sensibilities, avert your eyes from the image on the left.)

P.S. from the book – here is an account of the composition of a Mera Naam Joker song that wasn’t used. (Those with delicate sensibilities, avert your eyes from the image on the left.)

Of all things, this reminded me of a bonfire evening during a trip to Kabini a few years ago. During one of those soirées that I always feel very out of place in, a fellow we had just met began singing old Hindi-film songs like “Kabhi Kabhi Mere Dil Mein…” Except that he replaced some of the songs’ words with “dirty” ones, mainly slang descriptions of genitalia and such, thus skilfully altering the original meanings.

What was interesting, though, was that he sang well, and soulfully. If you could listen only to the cadences of his voice, blocking out the words (and this is something I usually do while listening to Hindi film songs anyway; my brain prioritises the tune over the lyrics), it was obvious that he had a real feel for the songs. The whole thing became tedious after a while (as these things tend to do), but while it lasted it was brilliantly funny and vulgar and moving, and other things in between. Remembering that evening much later, I thought about the associations that get built around human constructs like words with specific meanings; how one random combination of syllables, one turn of phrase, draws gasps of genteel appreciation while another is labelled obscene or unfit for polite company.

Anyway, do read this passage from the RK book. Regardless of the lies that some of you believe about the old days being oh-so-refined-and-sophisticated, it’s likely that many of the beautiful, gentle old melodies that we love were created in bawdy circumstances.

January 27, 2022

Thoughts on Minnal Murali, and a chat with Tovino Thomas

Last week I did a short phone interview with the actor Tovino Thomas, for India Today. The Q&A is below. Before that, some thoughts on Tovino, whose work I have been enjoying in recent times – especially last year’s Kala (which he also co-produced) and Kaanekkaane, and the new superhero film Minnal Murali (which was the peg for the India Today interview).

Last week I did a short phone interview with the actor Tovino Thomas, for India Today. The Q&A is below. Before that, some thoughts on Tovino, whose work I have been enjoying in recent times – especially last year’s Kala (which he also co-produced) and Kaanekkaane, and the new superhero film Minnal Murali (which was the peg for the India Today interview).Though Tovino is, to put it mildly, a good-looking man with considerable screen presence, that in itself doesn’t account for the part he is playing in the ongoing Malayalam cinema renaissance. What’s more notable is that much of his best work gets its tension from the contrast between his hunky charm on the one hand, and a vulnerability – or in some cases, unlikability – in his characters.

Some fine films have used this dichotomy to terrific effect: in both Kala and Kaanekkaane, for instance, Tovino’s personality and physical appearance help subvert a narrative, or keep us guessing. In the heavily stylized Kala, the establishing sequences, including an intense lovemaking scene, suggest that his alpha-male character Shaji is the protagonist (even though he looks a little too feral to be a straight “hero”). But as the narrative continues Shaji loses much of his self-assurance and we see him in a very different light. Meanwhile, in Kaanekkaane, as a man whose wife died in an accident, Tovino looks lost and distracted, then shows heartfelt emotion near the end – but much of the film’s suspense hinges on the possibility that the character is a philanderer who lied to his ex-father-in-law; so what else might he be capable of?

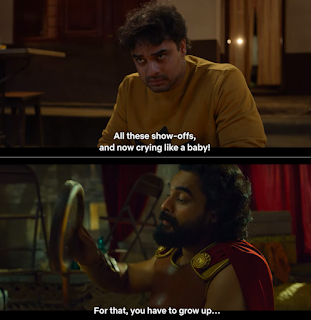

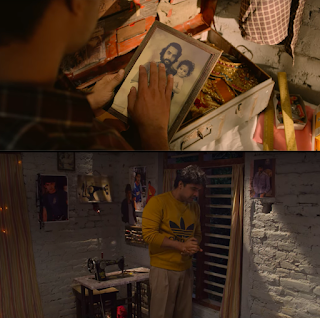

Different sides of the actor’s persona are also on view in Minnal Murali, the acclaimed new superhero film with Tovino as a small-town tailor, Jaison, who discovers new possibilities in himself after a freak lightning strike. The film moves inevitably towards a climax where Tovino gets to strike a heroic pose in his custom-fitted costume, but long before that we see Jaison as a man-child who sulks and mumbles “I deserve a better life!” to himself. In the initial scenes it is the eventual “super-villain” Shibu (wonderfully played by Guru Somasundaram) who seems more soulful and sympathetic, appearing to use his superpowers for a noble cause – saving a little girl – while Jaison is still goofing around. But soon their arcs change. Both men are in some way “unsuitable” – and harassed by people around them, including the police – but as one grows in stature the other regresses.

Different sides of the actor’s persona are also on view in Minnal Murali, the acclaimed new superhero film with Tovino as a small-town tailor, Jaison, who discovers new possibilities in himself after a freak lightning strike. The film moves inevitably towards a climax where Tovino gets to strike a heroic pose in his custom-fitted costume, but long before that we see Jaison as a man-child who sulks and mumbles “I deserve a better life!” to himself. In the initial scenes it is the eventual “super-villain” Shibu (wonderfully played by Guru Somasundaram) who seems more soulful and sympathetic, appearing to use his superpowers for a noble cause – saving a little girl – while Jaison is still goofing around. But soon their arcs change. Both men are in some way “unsuitable” – and harassed by people around them, including the police – but as one grows in stature the other regresses. In this very atypical setting (for the genre), there is slapstick comedy, and the story builds in mundane, unglamorous contexts: Jaison tests his powers by juggling kitchen utensils and stopping a dirty-looking ceiling fan with one hand; clumsily, he discovers that flying is not one of his new gifts. And Tovino – listed the most desirable man from Kerala in a 2018 survey – sends up his own image as a style icon: in one scene, Jaison poses for a camera in an “Abibas” shirt (which he thinks is the real thing) and goes “Stylish, right?” He’s still a long way from being a saviour, and it’s one of the reasons why Minnal Murali is such an unusual and charming superhero movie.

Another thing I liked about the film was that though no time period is specified, it seemed to be set in a pre-liberalisation India that was much more cut off from the rest of the world. (Of course, the small-town Kerala setting already places the film at a remove from the big-city superhero movie; but period-wise it helps that this is a world without the internet or cell-phones.) Speaking as an 80s kid, it was comforting to feel that when Jaison’s little nephew gushes to him about American superheroes, the Superman and Batman being talked about might be the Christopher Reeve and Michael Keaton versions, and that Spiderman is a 5.30 pm cartoon show rather than a feature film. It felt like this dissociated the film from today’s Marvel and DC franchises, which have cluttered the superhero landscape so much that even fans sometimes find it hard to follow the chronologies and interrelationships; or from the ponderous “it’s dark and brooding, so it’s more meaningful than your regular comic-book stories” world of Christopher Nolan’s Batman films.

Here is the Q&A:

As an actor, how satisfying was it to do Minnal Murali? There is a perception that superhero movies aren’t good for “serious” actors, but I felt you got to do a bit of everything in this film.

Yes – I enjoyed playing the many shades of Jaison, from a self-centred, juvenile guy to a superhero who becomes selfless. It’s a gradual transformation, we wanted to keep it subtle, and I had to think like this character: if someone like Jaison gets a superpower, he won’t go out and start saving people the next day, he will just be excited to start with. Evolving into something good over a period of time, looking beyond his own selfish concerns – that’s what provided the character arc and made it worthwhile as an actor.

Did Basil Joseph (the director) and you set out to make it as rooted as possible, to be different from the regular type of superhero movie?

That came naturally to us – Basil and I are both small-town boys who dreamt of cinema as youngsters, then met at some point. I did Godha (2017) with him, we became good friends, our families are close now. It’s a very good working relationship too: he gave me the space to improvise, and I can see it on his face when I give a good performance, which is very encouraging. Also, we both have kids inside us – we don’t want to grow up!

With our budgets, we couldn’t do a Marvel or DC-type film anyway, and you can’t have superheroes flying around skyscrapers in a Kerala setting. We wanted it to be grounded, relatable, we wanted people to believe almost everything in it. So even the reason for the character’s transformation is a natural force, lightning. And we have used practical effects instead of VFX to make it look more realistic. The emphasis was on emotions and character development, which is something that Malayalam cinema has a reputation for.

With a Chitrahaar reference early in the film, the posters shown (Anil Kapoor and the very young Aamir Khan), no mobile phones or internet, I got the impression it was set in the late 1980s. Is that right? If so, it adds to the old-world charm of the story and the sense that it doesn’t belong to a technology-saturated universe.

With a Chitrahaar reference early in the film, the posters shown (Anil Kapoor and the very young Aamir Khan), no mobile phones or internet, I got the impression it was set in the late 1980s. Is that right? If so, it adds to the old-world charm of the story and the sense that it doesn’t belong to a technology-saturated universe.Close enough – we thought of it as being set in 1994 or 95, which was the time of our childhoods, with so many things that we remembered from then. And yes, it would have been a very different type of film if it had computers and mobile phones in it. Technology would have had to play some role in the plot. But we also don’t want to restrict ourselves in future Minnal Murali films. We have passed the first exam, which was the character’s origin story – after this we can do more, take more liberties, change the setting if needed.

Even though this is a grounded superhero film, we are hoping that its success will get regular viewers more interested in Malayalam movies – which is something that a popular-genre film like Minnal Murali can do if it is well made. We in Kerala watch French or Korean movies, so why can’t people watch Malayalam movies? Especially in the OTT era when there is good distribution and promotion for our films. Cinema is a visual language, after all.

Looking at Malayalam cinema from the outside, it seems like there is a lot of genuine collaboration, a spirit of kinship. I have seen you thanked in the credits of films that you weren’t directly involved in the making of (The Great Indian Kitchen, for example). Is the industry more close-knit than the Hindi cinema world?

I think so, yes. There is lots of multi-tasking in our industry – for example, Minnal Murali’s cinematographer Sameer Thahir is also a director and screenwriter. There is healthy competition, based on the idea that the industry as a whole should grow. I have done a cameo recently in Kurup, played a supporting part in a woman-centric film like Uyare, a small part in a Mohan Lal film (Lucifer) – there was no ego involved, and that’s true for most of us. I also like to help out or be involved with films even when I’m not acting in them.

You have been taking uncharted paths as an actor, and now as a producer. Do you choose scripts that will let you experiment or do something different from audience expectations?

I always wanted to be a very good actor and to push my limits – I consider money and fame to be by-products of that process. I’m not saying I’m a great actor, there is scope for improvement, I have taken wrong decisions – but once I understand this then I do my best to correct it. Also, I have to be entertained by what I’m doing – I will get bored of myself if I keep doing the same sorts of films or characters. This is also why I try to change my look as much as I can from one role to another, and keep my characters as different as possible. By the way, do watch the trailer of Naaradan, the film I have just done with Aashiq Abu – I have a different appearance there as well, and I’m very enthusiastic about the film.

Even within the Minnal Murali canvas, you look boyish as the young Jaison, but authoritative and like a true hero, a larger-than-life figure, as his father in the flashback scenes.

Yes, that again was something we worked on carefully – that contrast and the sense of character development, the sense that this boy has to grow up to truly understand his father and fill those shoes.

As for producing films: when I come across an amazing script – like Kala, which I had conviction about – I want to push it. But I don’t want to be a full-time producer, I want to concentrate on acting. 2021 was a very good year for me, with three completely different movies and characters (Kala, Kaanekkane, Minnal Murali), and I expect as much from this year.

[Related post: some thoughts on Malayalam cinema as an outsider - a piece I did for Outlook magazine last year]

January 22, 2022

Munich: The Edge of War – an elegant, often-engrossing historical thriller (with an unintentionally funny Hitler)

(I mostly liked this new film, set around the 1938 Munich Agreement, though there were a few odd things in it. Did this review for First Post)

-----------

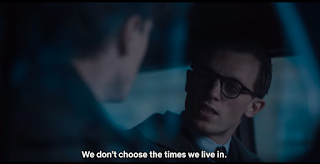

In the opening scene of a film that has just released on Netflix, a young nationalist speaks of a new era that is beginning in his long-suffering country, and of the larger-than-life leader – with a personality cult having grown around him – who is making it possible. “They are a bunch of thugs and racists,” replies his friend, referring to the leader and his party, but the first young man is having none of it. “We are now the proudest nation on earth,” he says.  It’s the sort of conversation that might well happen in the India of today – between two people who pejoratively call each other “sickular” and “bhakt” – but the scene is from Munich: The Edge of War, and the reference is to 1930s Germany. Paul von Hartmann (played by Jannis Niewöhner) is the German student in Oxford, while Hugh Legat (George MacKay) is his English friend, and their ideological differences will eventually rupture their relationship (after an argument that includes Paul’s hair-raisingly familiar claim that “voting for Hitler is not voting against Jews – it’s voting for the future”).

It’s the sort of conversation that might well happen in the India of today – between two people who pejoratively call each other “sickular” and “bhakt” – but the scene is from Munich: The Edge of War, and the reference is to 1930s Germany. Paul von Hartmann (played by Jannis Niewöhner) is the German student in Oxford, while Hugh Legat (George MacKay) is his English friend, and their ideological differences will eventually rupture their relationship (after an argument that includes Paul’s hair-raisingly familiar claim that “voting for Hitler is not voting against Jews – it’s voting for the future”).

Years later, their paths will cross again – at the site of the 1938 Munich Agreement between Hitler and the British PM Neville Chamberlain, where the fate of Czechoslovakia is to be decided. That’s the premise of this political thriller, adapted from Robert Harris’s 2017 novel Munich (with “The Edge of War” awkwardly added to the film’s title, presumably to avoid confusion with Steven Spielberg’s Munich).

History tells us that the Munich agreement (also known as the Munich Betrayal) was a case of European leaders falling over themselves to appease a fascist who would never be content with simply annexing one small country; as Hitler’s ambitions and claims grew over the next year, the Second World War became inevitable, and the Munich pact is now generally viewed as a giant folly. But in Harris’s dramatized alternate history – starring the fictional Hugh and Paul – more complex games of realpolitik were afoot and Chamberlain is cannier and wiser than he is usually credited as being.

Those who find that too much of a leap of faith will do better to focus on the fictionalised espionage story, convoluted as it sometimes is. Former friends Hugh and Paul are on the same side now, since Paul has come to recognise the damage being wrought in his country and is part of a secret anti-Nazi resistance. But it takes Hugh – now a secretary in the British  Foreign Ministry – some time to fully process what the stakes are. Like many others, he clings to the hope of lasting peace. Paul, who is more urgent (“To hope means waiting for someone else to do it”), more passionate (“The great characteristic of the English is distance. Not only from one another but from feeling”) and understands Hitler better, knows that war is coming. The question is when, and how prepared can the Allies be for it.

Foreign Ministry – some time to fully process what the stakes are. Like many others, he clings to the hope of lasting peace. Paul, who is more urgent (“To hope means waiting for someone else to do it”), more passionate (“The great characteristic of the English is distance. Not only from one another but from feeling”) and understands Hitler better, knows that war is coming. The question is when, and how prepared can the Allies be for it.

****

This is an uneven, sometimes perplexing narrative. At its best, it’s a touching story about friendship, about the ways in which the personal and the political can collide, and about the gulf between youth and experience. (On the one hand, there are young men cocky enough to believe that the world’s fate lies in their hands; on the other, an old man, committed to protocols, says “This is most improper” when asked to participate in an urgent secret meeting.) The lead performances are very good, and as Chamberlain the veteran Jeremy Irons effortlessly shifts registers between a doddering relic from a PG Wodehouse book and a dignified statesman determined to see peace. There are some nice supporting turns too – including one by the cleverly cast August Diehl, as sinister and watchful a Nazi as he was in the guessing-game scene in Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds. The film elegantly suggests the dilemma at the heart of its story: when a situation is so bad that the only options are to embrace disaster right now or to risk much greater disaster in the future, can one find the hope or resolve to do the right thing? Is there even a “right thing”? In its more underwhelming moments, though, there is much ponderous dialogue (“Friends, history is watching us.” Really?) along with some strange choices. Almost every time the Führer (played by Ulrich Matthes, who looks about as Hitler-like as Raghubir Yadav did in Dear Friend Hitler, or as Asrani did as the jailer in Sholay) appeared on screen, I wanted to giggle – which was probably not the intended effect. As portrayed here, Hitler shows the same disdain for Oxford education as Narendra Modi once did for Harvard; there is also a bit of business involving Paul’s wristwatch that was probably meant to make the dictator seem menacing but felt like slapstick comedy to me. You don’t want the Hitler in this film to remind you of Inglourious Basterds, though the story does steer close to providing a similar wish-fulfilment ending.

In its more underwhelming moments, though, there is much ponderous dialogue (“Friends, history is watching us.” Really?) along with some strange choices. Almost every time the Führer (played by Ulrich Matthes, who looks about as Hitler-like as Raghubir Yadav did in Dear Friend Hitler, or as Asrani did as the jailer in Sholay) appeared on screen, I wanted to giggle – which was probably not the intended effect. As portrayed here, Hitler shows the same disdain for Oxford education as Narendra Modi once did for Harvard; there is also a bit of business involving Paul’s wristwatch that was probably meant to make the dictator seem menacing but felt like slapstick comedy to me. You don’t want the Hitler in this film to remind you of Inglourious Basterds, though the story does steer close to providing a similar wish-fulfilment ending.

Also, even as one acknowledges the horrors of Nazi Germany and the need for that regime to be defeated, for an Indian viewer with knowledge of colonial history and British atrocities (even around the time of the events depicted here), there is naturally some ambivalence built into watching a film like this where the good guys and the bad guys are so clearly defined. It’s hard not to raise an eyebrow during a scene where Hitler’s imperialist expansion is described as being the opposite of everything the British PM stands for.

In fairness the film does touch on this at one point. “You’re one to talk about exploiting others, Englishman!” Paul says. “I know I’m a hypocrite, but I know fanaticism when I see it,” responds Hugh. Their conversations – where we see two young men weighing ideological positions, recognising the contradictions in themselves and in their world – are ultimately at the heart of this odd but engrossing film.

(My earlier First Post pieces are here)

January 8, 2022

Mix and match: Aranyak, The Leopard Man, The Power of the Dog

In my Economic Times column, thoughts on beasts and men (or victims and predators) in an enjoyable new crime series Aranyak, a 1940s B-horror film and Jane Campion’s new Western

--------------------

The opening image of the new series Aranyak involves a movement from a dark space to a well-lit one: the camera follows a man in a leopard costume through a “cave” onto the stage of an auditorium where fond parents are watching a school production. It’s fun and games at first, but then the music becomes minatory, there are unsettling close-ups of the “leopard” holding a “rabbit”, and we realise that this is a performance within a performance. A human, mimicking a predatory animal, turns out to be a predator himself. The transition from wilderness (or an impression of wilderness) to civilisation, and the blurring of Man and Beast, are central to this story, which is actually set a few years after that school-play scene. The main Aranyak narrative centres on a murder in a fictional hill town, and the widespread local superstition that a mythical creature – half man, half animal – is on the rampage. Early in the show, police inspector Kasturi (Raveena Tandon) finds a snarling leopard (a real black leopard, albeit one that’s obviously computer-generated) in her house’s compound, menacing her daughter. But we are also invited to reflect that this creature is one of many victims of human encroachment into the natural world. (An important character, a smarmy parliamentarian, is trying to convert forest land into a tourism project. “If it continues like this,” someone says sardonically, “all the wild animals will enter our homes.”)

The transition from wilderness (or an impression of wilderness) to civilisation, and the blurring of Man and Beast, are central to this story, which is actually set a few years after that school-play scene. The main Aranyak narrative centres on a murder in a fictional hill town, and the widespread local superstition that a mythical creature – half man, half animal – is on the rampage. Early in the show, police inspector Kasturi (Raveena Tandon) finds a snarling leopard (a real black leopard, albeit one that’s obviously computer-generated) in her house’s compound, menacing her daughter. But we are also invited to reflect that this creature is one of many victims of human encroachment into the natural world. (An important character, a smarmy parliamentarian, is trying to convert forest land into a tourism project. “If it continues like this,” someone says sardonically, “all the wild animals will enter our homes.”)

Structurally, Aranyak is comparable to the acclaimed series Mare of East Town, which is also a crime investigation with a solid lead role for a middle-aged actress (Kate Winslet), and set in a place where everyone knows everyone else – resulting in a tangled weave of suspects, personal histories and interrelated motives. But one of the joys (and hazards) of being a full-blown movie nut is how often you see connections between generally unrelated works: how a similarity of name, or a character arc, or just a particular scene, can lead you down various rabbit-holes. Or leopard-caves. Just one whimsical example: watching a scene involving a cute rabbit – fussed over but eventually disembowelled for medical purposes – in Jane Campion’s new film The Power of the Dog, I thought of the kidnapped “Rabbit” in Aranyak. The Campion scene was also a reminder of the different contexts in which someone can be victim or prey: the bunny-killer is a shy, bullied young man who we are meant to be rooting for but who turns out to be steelier than expected. (Along similar lines, Aranyak ends with the suggestion – heralding a second season – that the “victim” from its opening scene may have become a threat.)

Much as I liked the threads that jostle for our attention over Aranyak’s eight episodes, I also fixated on a specific aspect of it: the repeated references to the much-feared “nar-tendva” – or “leopard man”, as the subtitles had it. This had me thinking about a 1943 film by that name, produced by Val Lewton, who was a master of low-budget psychological horror in that decade. The differences between The Leopard Man and Aranyak are more pronounced than the similarities, given the changes in filmmaking styles and tones over eight decades (from the world of the 1940s B-movie to the polished and expansive OTT universe of today). The Lewton “flick” – as it would have been described by most people in its time – is in black-and-white, looks creaky to modern eyes, and at 66 minutes it is one-fifth the length of Aranyak. But like the new series, it involves a human criminal who may be using fear of the unknown – or fear of wild beasts – as a cover for his own dark pursuits.

The differences between The Leopard Man and Aranyak are more pronounced than the similarities, given the changes in filmmaking styles and tones over eight decades (from the world of the 1940s B-movie to the polished and expansive OTT universe of today). The Lewton “flick” – as it would have been described by most people in its time – is in black-and-white, looks creaky to modern eyes, and at 66 minutes it is one-fifth the length of Aranyak. But like the new series, it involves a human criminal who may be using fear of the unknown – or fear of wild beasts – as a cover for his own dark pursuits.

Once a broad connection between two such works is made, other little things fall in place. Both film and show make references to wild creatures wanting to stay away from concrete and cement dwellings unless they have no other option. If the real leopard in Aranyak looks like a CGI creation (hence not “scary” to the eyes of discerning viewers), the black leopard shown in The Leopard Man is underwhelming too: it looks puny and out of its depth in a scene where a nightclub performer brings it (on a leash!) to a crowded party. In both cases, though probably unintended, the effect is that the relative harmlessness of the “wild creature” is emphasized. The bigger menace, as is often the case, comes from humans – especially when they combine the feral side of their natures with the big-brained ability to contrive and manipulate. Run, rabbit, run.

January 5, 2022

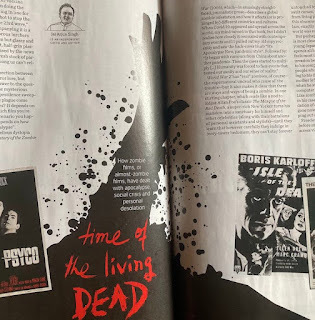

Our zombie selves in Covid time: an apocalyptic essay

Outlook magazine had a year-end special built around the cheerful theme “Apocalypse”. I wrote a piece about zombies in film/literature/Covid times. (This includes Max Brooks’s marvelous book World War Z, as well as one of my favourite Val Lewton films I Walked with a Zombie, which I discussed during an online class a year ago. Here is the piece…

---------------

It’s one of many mutation-vaccine memes that has been doing the rounds lately. “Waiting in line for your 56th booster shot to stop the 89th variant that comes with the 23rd wave” reads the text. The image accompanying it is a close-up of one of those malodorous lurchers from a zombie movie – eyes open but glassy and unseeing, slash marks on throat, half-grin plastered on his (its?) face, as if pleased by the news that the local pharmacy has a fresh stock of paracetamol.

At this point, who among us can’t relate to this shuffling wretch? There is a long-standing connection between zombies and pandemics in horror lore, but there isn’t always a definite answer to the question: which came first? Does the mysterious emergence of zombies lead to pestilence sweeping across the land, or does the plague come first, turning us all into zombies? It depends on which book you’re watching, which film you’re reading… or which real-life scenario you happen to be inhabiting. It also depends on how you define “zombie”, or “apocalypse”.

There is a long-standing connection between zombies and pandemics in horror lore, but there isn’t always a definite answer to the question: which came first? Does the mysterious emergence of zombies lead to pestilence sweeping across the land, or does the plague come first, turning us all into zombies? It depends on which book you’re watching, which film you’re reading… or which real-life scenario you happen to be inhabiting. It also depends on how you define “zombie”, or “apocalypse”.

Consider Max Brooks’s marvellous dystopia book World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War (2006), which – in amusingly straight-faced, journalistic prose – describes a global zombie infestation and how it affects (or is prolonged by) different countries and cultures. When Covid-19 got underway, my mind turned to that book, but I didn’t realise how closely it resonated with contemporary events until I pulled out my old copy recently and saw the back-cover blurb “It’s Apocalypse Now, pandemic style”. Followed by: “It began with rumours from China about another pandemic. Then the cases started to multiply […] Humanity was forced to face events that tested our sanity and our sense of reality.”

World War Z has “real” zombies, of course – the supernatural undead who cause all the trouble – but it also makes clear that there are ways and ways of being a zombie. In one stirring chapter, which reads like a nod to Edgar Allan Poe’s classic story “The Masque of the Red Death”, a super-rich New Yorker turns his mansion into a sanctuary for himself and other celebrities (along with their battalions of personal assistants and stylists) – until they learn that however carefully they indulge in ivory-tower hedonism, they can’t stay forever untouched by a raging plague. When the assault comes, it comes not from zombies but from living people on the outside, enraged by this obscene display of privilege. “It was bedlam, exactly what you thought the end of the world was supposed to look like.”

But perhaps the zombie-in-apocalypse theme is most clearly realised in the section about a young Japanese man named Kondo who spends all his time on the internet, where he feels most in control. Long before the zombie invasion begins, Kondo is an automaton: glued to his computer, mechanically interacting with people whom he doesn’t really know, staggering to his door to collect the meal trays his mother left for him outside. Little wonder that when he awakens to an unthinkable crisis – no computer or internet – he goes nearly insane. Like the zombies, he needs something to feed on: in his case, the glow of the screen and the validation of other cyber-residents. But that is gone now, and he is so socially inept that stepping out of his building is barely an option.

Prescient as Brooks’s book was, it was written before smart-phones, social media, and easy-to-access video-meeting rooms – and these are things that don’t figure in the narrative (at least not to the degree that they have now infected our world). I think of Kondo the almost-zombie whenever I come across a tragic-comic news items about a young person, so lost in a phone screen while walking, that they tumble into an uncovered manhole or something such (still gazing into the phone, their minds not having yet processed all the signals).  It is easy to recognise the zombies in ourselves in the cyber-age, where one can stay cut off from the outside world for long durations. (This even before a nasty little virus came along and forced us all into our houses, giving many of us the excuse we wanted to never meet anyone.) It is also easier than ever to grumble that technology has facilitated alienation and living-dead behaviour. But in fairness, versions of this have been happening for hundreds of years. Think of all the stories about insensate, vaguely human-like creatures – going back to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and beyond – that were responses to new technological developments; born of the fear that in moving away from the comforting moral certainties of religion towards something more diffused and unpredictable, people would lose their humanity.

It is easy to recognise the zombies in ourselves in the cyber-age, where one can stay cut off from the outside world for long durations. (This even before a nasty little virus came along and forced us all into our houses, giving many of us the excuse we wanted to never meet anyone.) It is also easier than ever to grumble that technology has facilitated alienation and living-dead behaviour. But in fairness, versions of this have been happening for hundreds of years. Think of all the stories about insensate, vaguely human-like creatures – going back to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and beyond – that were responses to new technological developments; born of the fear that in moving away from the comforting moral certainties of religion towards something more diffused and unpredictable, people would lose their humanity.

Zombies are a direct bequest of that legacy. One of the most famous zombie films, George Romero’s 1968 Night of the Living Dead, begins with a cemetery scene where a young man (a non-zombie at this stage) is sardonic about traditional things such as putting a wreath on his father’s grave, and doesn’t even go to church. These “blasphemies” of a cold modern age prepare us for the arrival of the living dead. But a question hangs over the film: was that man already dead inside?

****

Historically too, even in the age of early, low-budget horror movies, some of the most notable cinematic “zombies” weren’t supernatural: they were regular people who had been petrified into inaction – through circumstances, or because they had looked for too long into an abyss. The hopelessness might be engendered by personal tragedy, general distress about their immediate surroundings, or cosmic destruction at an unthinkable scale.

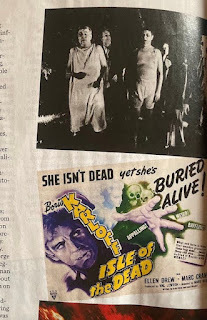

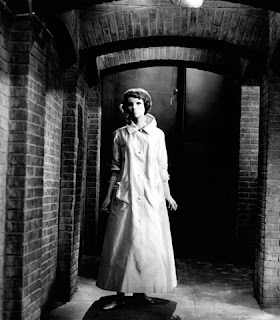

Consider the wonderfully atmospheric I Walked with a Zombie (1943), produced by a master of subdued horror, Val Lewton. This film’s sensationalist B-movie title doesn’t begin to convey its quiet, haunting beauty and how it deals not with external terrors but with a soul-destroying conflict within a family where a young woman has turned catatonic after an illicit affair. Or take another tragic young woman from the genre – Christine, the disfigured protagonist of the 1960 Eyes Without a Face, who wanders desolate through the rooms of a large mansion while her scientist father tries to restore her features. Or another legendary horror-film character who must also have spent long lonely hours walking through an old house, Norman Bates in Psycho, rendered zombie-like by his crippling dependence on his long-dead mother.  If the heroine of Eyes Without a Face wears a mask – like someone living through a pandemic – there are other similarly isolated characters in dystopian films. In the climactic scene of the chilling The Face of Another (1964), a doctor has a nightmare vision of countless masked people – soulless ciphers – walking through the streets of a city. For the protagonists of these films, “apocalypse” is a very personal thing, as it would be for most of us in their situation: how does it matter to them if the rest of the world goes on as normal? In another Val Lewton-produced work, Isle of the Dead, a group of people are stranded on an island as a plague rages around them. They scrub their hands, wear masks when possible, and are very aware of the external dangers; but their inner demons are what consume them.

If the heroine of Eyes Without a Face wears a mask – like someone living through a pandemic – there are other similarly isolated characters in dystopian films. In the climactic scene of the chilling The Face of Another (1964), a doctor has a nightmare vision of countless masked people – soulless ciphers – walking through the streets of a city. For the protagonists of these films, “apocalypse” is a very personal thing, as it would be for most of us in their situation: how does it matter to them if the rest of the world goes on as normal? In another Val Lewton-produced work, Isle of the Dead, a group of people are stranded on an island as a plague rages around them. They scrub their hands, wear masks when possible, and are very aware of the external dangers; but their inner demons are what consume them.

Personal tragedy often runs alongside social commentary in these stories: for instance, I Walked with a Zombie is set on an island with a history of colonialism and racial oppression; the white characters in the film may have infected the place through generations of exploitation. But then, anyone who knows the history of horror cinema knows that the genre, however otherworldly or fantastical it might seem, has always had powerful subtexts. “Unusual Times Demand Unusual Pictures” said an advertisement for the Depression-Era film White Zombie; as David Skal put it in his fine book The Monster Show, part of the reason why this film was scary was that “millions already knew that they were no longer completely in control of their lives; the economic strings were being pulled by faceless, frightening forces”. Decades later, when the American economy was in a much healthier place, along came Romero’s 1979 Dawn of the Dead – a witty commentary on the giant-shopping-mall era, where rampant consumerism could turn people into zombies.

And then there is the end of the world, non-pandemic-style – and outside the horror genre. I’m thinking about two very different types of films made in different cultures in 1955, both of which involve terror of nuclear annihilation: Akira Kurosawa’s plaintive drama I Live in Fear and Robert Aldrich’s B-noir Kiss Me Deadly. Both have scenes involving bright flashes of light that might signal Armageddon, and people who are paralysed by fear. The protagonist of I Live in Fear, an old man traumatised by  Hiroshima and Nagasaki, cowers when his house is lit up by lightning during a storm, imagining it to be another atom bomb attack. In Kiss me Deadly, when a woman opens a mysterious, glowing suitcase, we realise that this is a horrific Pandora’s Box containing a form of all-consuming nuclear power; and the house goes up in flames. Both the old man and the woman are rendered immobile and sub-human… like you-know-what.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, cowers when his house is lit up by lightning during a storm, imagining it to be another atom bomb attack. In Kiss me Deadly, when a woman opens a mysterious, glowing suitcase, we realise that this is a horrific Pandora’s Box containing a form of all-consuming nuclear power; and the house goes up in flames. Both the old man and the woman are rendered immobile and sub-human… like you-know-what.

From the fears of rapid industrialisation to the world wars, from the possibility of mutually assured nuclear destruction to climate change… and now to Covid-19 and its many avatars: every age has had its own zombie-generators. Each situation poses its own special challenges, but maybe some things don’t change all that much over the centuries. Writing about White Zombie in 1932, a reviewer quipped that zombies were especially useful in the busted economy, “since they don’t mind working overtime”. Something similar might be said for some of us in Covid’s WFH world, where the line between work time and leisure time has been blurred, where there is no “switching off”, and we stare into the depths of our many screens, fingers involuntarily tapping away to indicate slight signs of life. Perhaps the next major zombie film should be about the undead launching their most macabre attack yet… by infiltrating our online video meetings.

December 20, 2021

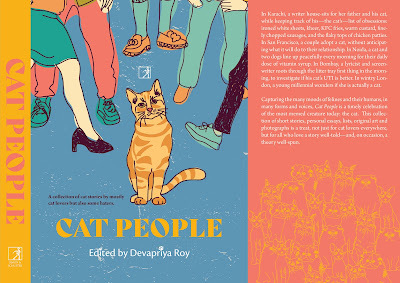

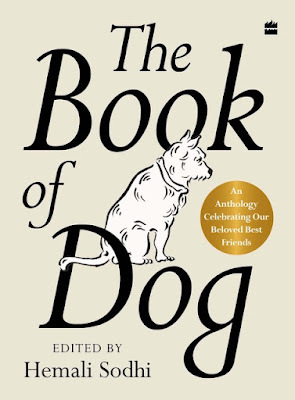

Two new anthologies: Cat People and The Book of Dog

Some news about two new books that I am in (and am very proud of, and looking forward to experiencing as a reader too). Entirely by coincidence, one is an anthology about cats and the other is an anthology about dogs. Different publishers, different editors, and the essays I contributed were commissioned (and written) many months apart – but as these things sometimes happen, the promotional announcements for both books are in the same week, and both are now available for pre-order.

Presenting:

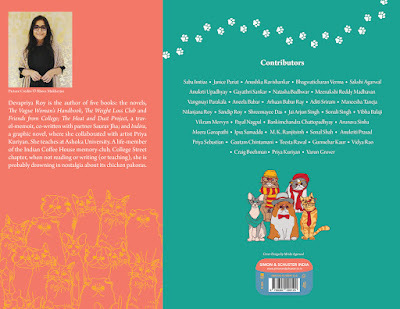

Cat People (edited by Devapriya Roy)

and

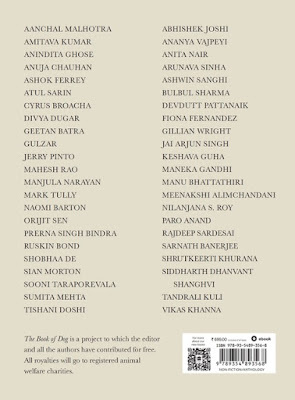

The Book of Dog (edited by Hemali Sodhi)

You can scroll down and gape at the list of contributors. Incidentally, as far as I can tell, I am one of only three writers who are in both the cat and the dog book, along with Nilanjana S Roy and Arunava Sinha (two giants of the Indian literary world who have been inspirations for very long). I am as pleased about this as I was to be the only male contributor to the Zubaan anthology Of Mothers and Others nearly a decade ago.

A word about my two essays. The cat piece was one of my most intense (sometimes painful) writing projects of the past few years: a personal essay about my mother and her relationship with animals, about our cats of yore, about old diary entries and how they often contradict one’s memories. Massively self-indulgent, possibly of little interest to anyone other than myself (he says, while hastening to remind the reader that there are many other worthy writers in this anthology) – but I was very happy to have written it in the way I wanted to write it. (The first draft was something like 10,000 words, I eventually cut it down to under 6,000 words. One bit that was removed was a sub-section about the great 1944 film Curse of the Cat People, which I discovered afresh during the Val Lewton course last year. Will revisit and finish that piece soon.)

The dog essay, a little shorter and chattier, is about something that is absolutely central to my daily life: the concept of the “part-time dog” – street dogs that one looks out for on a regular basis and feels responsible for, but also experiences unease about for various intersecting reasons. It is a tribute to some such animals I have known, including the legendary Chameli and Kaali, both of whom have appeared in my earlier posts. And my Lara’s mother, who died earlier this year. Royalty proceeds from this book go to registered animal-welfare charities.

Here are the pre-order links: Cat People and The Book of Dog. Please do spread the word to anyone who might be interested – and let me emphasise that these books aren’t only for animal-lovers (though that will naturally be the primary readership), they are for anyone who likes good, heartfelt writing. Have a look at those two contributors’ lists again.

BONUS

At an unrelated event yesterday, Hemali Sodhi and I continued our dubious longstanding tradition of posing with dog biscuits (or, in this case, a milk bone). Our first such photo session since the pandemic began. See:

December 18, 2021

A monumental feat – the Sabz Burj restoration

Wrote this short piece for India Today about the newly restored Sabz Burj – a 16th century mausoleum – in Nizamuddin. It looks especially brilliant now with the lights on at night, and it’s a very good idea to have a look while visiting Sunder Nursery or Humayun’s Tomb.

(And yes, that’s Cereberus the hound in the first photo, guarding the tomb’s gates. He was happy to pose…)

---------------------------------

If you crossed the roundabout at the juncture of Delhi’s Lodhi Road and Mathura Road a few years ago, your eyes may have dimly registered the unremarkable-looking monument standing there; one among countless old structures that dot this city of many histories. Take the same route today and your sensory experience will be very different: even through dust and haze and the eyesores of bumper-to-bumper vehicles, the newly renovated Sabz Burj, its blue-tiled dome gleaming, will catch your eye from some distance away. The identity of the nobleman for whom this octagonal mausoleum was built – probably in the 1530s, during Humayun’s reign – is unknown, but there is no longer any question that the burj was an important part of the large necropolis that existed around the Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia Dargah.

If you crossed the roundabout at the juncture of Delhi’s Lodhi Road and Mathura Road a few years ago, your eyes may have dimly registered the unremarkable-looking monument standing there; one among countless old structures that dot this city of many histories. Take the same route today and your sensory experience will be very different: even through dust and haze and the eyesores of bumper-to-bumper vehicles, the newly renovated Sabz Burj, its blue-tiled dome gleaming, will catch your eye from some distance away. The identity of the nobleman for whom this octagonal mausoleum was built – probably in the 1530s, during Humayun’s reign – is unknown, but there is no longer any question that the burj was an important part of the large necropolis that existed around the Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia Dargah.

For the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) team that began work on the renovation a few years ago, the challenges were obvious. Much of the incised plaster patterns on the eight walls (each a different design) had faded or disintegrated, as had some of the striking large medallions with Quranic inscriptions. Previous restorations had created problems: the use of cement, for instance, leading to increased water penetration. The entire set of turquoise-blue tiles on the dome (approximately 8,000 in number) have now been replaced and fixed with lime mortar, as have a large percentage of the tiles – in four distinct colours – on the monument’s drum or “neck”.

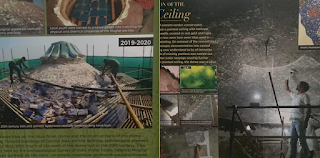

As Ratish Nanda, CEO, AKTC, points out, something of this vintage can’t magically be restored to exactly what it was hundreds of years ago; a certain degree of conjecturing – rooted in careful studies of Timurid architectural trends and construction methods – is inevitable. Take the burj’s sandstone jaalis (lattice screens), which no longer existed and had been replaced with aesthetically jarring metal grills – possibly during a period in the early 20th century when the structure was used as a police station. In recreating these jaalis, the team didn’t know the precise 16th century design, but as Nanda says, the important thing was to restore the integrity of the material originally used, and the processes by which the screens were made.  The big discovery during the restoration was the uncovering of what survived of an intricately painted ceiling in the domed chamber – the earliest existing painted ceiling for a Mughal Era structure. Faded though it is in its current form, a decision was made not to tamper with it to make it look shinier and more “touristy”. “We differentiate between craft and art, and have different approaches for them,” Nanda says, making it clear that the uncovered ceiling was being treated as an example of the latter. A reconstruction drawing has been made by the painter Himanish Das, however, and it creates a mental image of now-forgotten artists lying, Michelangelo-like, on their backs as they did this painstaking work.

The big discovery during the restoration was the uncovering of what survived of an intricately painted ceiling in the domed chamber – the earliest existing painted ceiling for a Mughal Era structure. Faded though it is in its current form, a decision was made not to tamper with it to make it look shinier and more “touristy”. “We differentiate between craft and art, and have different approaches for them,” Nanda says, making it clear that the uncovered ceiling was being treated as an example of the latter. A reconstruction drawing has been made by the painter Himanish Das, however, and it creates a mental image of now-forgotten artists lying, Michelangelo-like, on their backs as they did this painstaking work.

There is a poignant subtext here: located where it is, at a congested roundabout that’s tricky to cross, the Sabz Burj is not the sort of tourist attraction that will draw large crowds the way the nearby Sunder Nursery or Humayun’s Tomb do. Relatively few people will step into the interiors and see the remains of the grand ceiling. Many will, however, get to gawp at the beautiful exterior – a reminder that a diligent restoration can make the past feel more real and, well, present.

Jai Arjun Singh's Blog

- Jai Arjun Singh's profile

- 11 followers