Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 12

April 2, 2022

A hypocritical rant about watching films on tiny screens (or watching them back to front)

Occupying the top spot on my movie watchlist just now is SS Rajamouli’s epic RRR, but if “watchlist” makes you think of streaming platforms, let me clarify that I’ll see it the only way a big-canvas film should be experienced: on a very large screen. I remember being floored by Rajamouli’s Bahubaali in a movie hall, but feeling underwhelmed, even bored, when I caught parts of it on TV years later. Watching RRR in a theatre will also be a small step in atoning for a movie-watching blasphemy – and an accompanying hypocrisy – that I have often indulged in. Here’s the gist of it: for years I have given friends pedantic lectures about the ghastliness of watching films – especially certain types of films – on very small screens. I list all the usual arguments, grumble that anyone who watches a film that way is only engaging with it at the plot-and-dialogue level without registering any of its visual qualities, the things that make it C-I-N-E-M-A. I quote from essays on the subject. (Pauline Kael: “Reduced to the dead greys of a cheap television print, Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons is as lifelessly dull as a newspaper Wirephoto of a great painting.” David Thomson: “How can one tell one’s students or one’s children what it was like seeing Vertigo or The Red Shoes from the dark? We watch television with the lights on! Out of some bizarre superstition that it protects our eyes. How so tender for one part of us, and so indifferent to the rest?”)

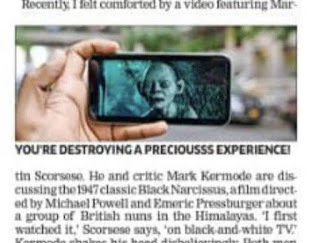

And yet: throughout my own career as a movie nerd (from note-taking pre-teen to professional writer), I have watched countless films – especially older films – in less than optimum conditions. On videocassette, on TV, finally on a laptop screen. In the 1980s my family hardly ever went to movie halls, so even mediocre films watched thus still seem grand and larger than life in my mind’s eye: an indelible memory of my multi-starrer-obsessed childhood is a scene from the 1986 Dosti Dushmani where the three heroes (Jeetendra, Rajinikanth, Rishi Kapoor) ride their bikes side by side, singing of friendship (Poonam Dhillon may have been perched behind one of them, feigning polite interest) – not because either song or film was good but because it was such a rare experience. On the other hand, I shudder to think that I watched some of the most visually ambitious films of that time, such as Mukul Anand’s Hum, on videocassette with animated underwear ads running across the bottom of the screen. Or that my obsession for old Hollywood – including widescreen-format films whose use of space and framing is integral to their effect – has been built around TV viewings. Recently I was comforted by a video featuring that most excitable of movie buffs, Martin Scorsese. He and critic Mark Kermode are discussing the 1947 classic Black Narcissus, about a group of British nuns in the Himalayas, unsettled by the otherworldliness of the environment and their memories of their earlier lives.

And yet: throughout my own career as a movie nerd (from note-taking pre-teen to professional writer), I have watched countless films – especially older films – in less than optimum conditions. On videocassette, on TV, finally on a laptop screen. In the 1980s my family hardly ever went to movie halls, so even mediocre films watched thus still seem grand and larger than life in my mind’s eye: an indelible memory of my multi-starrer-obsessed childhood is a scene from the 1986 Dosti Dushmani where the three heroes (Jeetendra, Rajinikanth, Rishi Kapoor) ride their bikes side by side, singing of friendship (Poonam Dhillon may have been perched behind one of them, feigning polite interest) – not because either song or film was good but because it was such a rare experience. On the other hand, I shudder to think that I watched some of the most visually ambitious films of that time, such as Mukul Anand’s Hum, on videocassette with animated underwear ads running across the bottom of the screen. Or that my obsession for old Hollywood – including widescreen-format films whose use of space and framing is integral to their effect – has been built around TV viewings. Recently I was comforted by a video featuring that most excitable of movie buffs, Martin Scorsese. He and critic Mark Kermode are discussing the 1947 classic Black Narcissus, about a group of British nuns in the Himalayas, unsettled by the otherworldliness of the environment and their memories of their earlier lives.

When I first watched it, Scorsese says, it was heavily edited. And… [Meaningful Pause] it was on black-and-white TV. Kermode shakes his head disbelievingly, both men crack up. And anyone who knows this film will understand why. Bright, bold, unflinching in its use of colour, featuring the use of spectacular matte paintings as a stand-in for Indian landscapes, and some startling moments that centre on colour effects (such as a character’s garish red makeup), Black Narcissus can scarcely have made any sense in monochrome. And yet Scorsese grew to love it (and did eventually watch it the way it needed to be watched). The present day – where someone might, heaven forbid, watch a Blade Runner 2049 or a Lord of the Rings on a phone screen – may seem especially conducive to viewing transgressions (even if this plague hadn’t chased us out of movie halls). And yet that Scorsese interview is a reminder that hand-wringing conversations about how to watch films don’t date back to just the last few years (or to the videocassette era); for much of film history even dedicated movie buffs have sometimes watched great films in inappropriate conditions. Even within the ambit of the big-screen experience, there have been terrible traditions such as the old one in the US where viewers would come in at any point during a screening, watch it till the end, and then catch up with what they had missed in the next show: thus effectively turning a conventional narrative film into a proto-Christopher Nolan jigsaw puzzle. (This was also the catalyst for Alfred Hitchcock’s famous admonition while barring viewers entry mid-screening: “We have discovered that Psycho is unlike most motion pictures. It does not improve when run backwards.”) As it happens, I once experienced a minor variant on this when I watched Sholay on a big screen for the only time, as a child: because my thoughtless family showed up 15 minutes late, I caught only a bit of the train-attack flashback near the film’s beginning, and stayed confused for years about the exact chronology of the story. So does all this mean that I’ll stop lecturing friends? No, since I have a trump card. I have never watched a film, even a short film, on a phone-sized screen – that’s a frontier I have no intention of crossing. There might not be an enormous difference between a laptop screen and a smartphone screen, but as tennis commenters say it’s a game of inches. I might rethink this though if a finger-nail-sized viewing device comes along… (An earlier post about related things is here. I have also written about this in The World of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, in the context of watching Anand on a big screen with a very enthusiastic crowd)

When I first watched it, Scorsese says, it was heavily edited. And… [Meaningful Pause] it was on black-and-white TV. Kermode shakes his head disbelievingly, both men crack up. And anyone who knows this film will understand why. Bright, bold, unflinching in its use of colour, featuring the use of spectacular matte paintings as a stand-in for Indian landscapes, and some startling moments that centre on colour effects (such as a character’s garish red makeup), Black Narcissus can scarcely have made any sense in monochrome. And yet Scorsese grew to love it (and did eventually watch it the way it needed to be watched). The present day – where someone might, heaven forbid, watch a Blade Runner 2049 or a Lord of the Rings on a phone screen – may seem especially conducive to viewing transgressions (even if this plague hadn’t chased us out of movie halls). And yet that Scorsese interview is a reminder that hand-wringing conversations about how to watch films don’t date back to just the last few years (or to the videocassette era); for much of film history even dedicated movie buffs have sometimes watched great films in inappropriate conditions. Even within the ambit of the big-screen experience, there have been terrible traditions such as the old one in the US where viewers would come in at any point during a screening, watch it till the end, and then catch up with what they had missed in the next show: thus effectively turning a conventional narrative film into a proto-Christopher Nolan jigsaw puzzle. (This was also the catalyst for Alfred Hitchcock’s famous admonition while barring viewers entry mid-screening: “We have discovered that Psycho is unlike most motion pictures. It does not improve when run backwards.”) As it happens, I once experienced a minor variant on this when I watched Sholay on a big screen for the only time, as a child: because my thoughtless family showed up 15 minutes late, I caught only a bit of the train-attack flashback near the film’s beginning, and stayed confused for years about the exact chronology of the story. So does all this mean that I’ll stop lecturing friends? No, since I have a trump card. I have never watched a film, even a short film, on a phone-sized screen – that’s a frontier I have no intention of crossing. There might not be an enormous difference between a laptop screen and a smartphone screen, but as tennis commenters say it’s a game of inches. I might rethink this though if a finger-nail-sized viewing device comes along… (An earlier post about related things is here. I have also written about this in The World of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, in the context of watching Anand on a big screen with a very enthusiastic crowd)

March 18, 2022

I come to praise Olivia Colman (though the Oscar nerd in me doesn’t want her to win the best actress award)

For a First Post series about the Oscars, I set out to make the “shocking” declaration that I didn’t want Olivia Colman to win this year. But of course, the piece ended up more as a Colman tribute, as everything eventually does…

-------------------

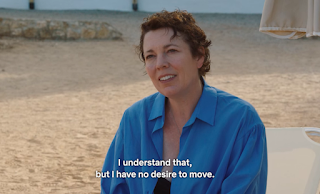

Since even those of us who are Oscar sceptics or agnostics tend to make award-related declamations at this time of year, here’s one: I’d rather Olivia Colman didn’t win best actress for The Lost Daughter.

But before I am impaled on that statement, damned by film buffs with impeccably good taste, let me sue for peace with the following clarification: like most sentient people who have watched any of her work, I am a big Colman fan. I have enjoyed everything I have seen her do, from her leading role in Broadchurch to smaller but powerful parts in films like Murder on the Orient Express or shows like The Night Manager.  I even liked her as Queen Elizabeth II in the third and fourth seasons of The Crown, though that might be considered a thankless role, a waste of an actor with such a vibrant personality: by the time Colman played the monarch, Elizabeth had been turned into a cipher, a polestar around which the other characters – including volatile people like Princess Diana and Margaret Thatcher – orbited and curtseyed. (Claire Foy, who played the younger version of Elizabeth, at least got a chance to depict a princess still sorting out tumultuous personal relationships, who hadn’t fully settled into placing duty above emotion.)

I even liked her as Queen Elizabeth II in the third and fourth seasons of The Crown, though that might be considered a thankless role, a waste of an actor with such a vibrant personality: by the time Colman played the monarch, Elizabeth had been turned into a cipher, a polestar around which the other characters – including volatile people like Princess Diana and Margaret Thatcher – orbited and curtseyed. (Claire Foy, who played the younger version of Elizabeth, at least got a chance to depict a princess still sorting out tumultuous personal relationships, who hadn’t fully settled into placing duty above emotion.)

In fact, my favourite Olivia Colman Crown moment was a video of her and other cast members, in full costume, performing a little dance between filming – freed of the encumbrance of her role, here she was, goofy smile in place, gliding around and waving her arms more enthusiastically than anyone else. It was delightful (here's the YouTube link), and it made one feel like all monarchies would be a lot cooler if queens modelled themselves on Olivia Colman.

Even in last year’s The Father, which was emphatically an Anthony Hopkins film with an author-backed role for the octogenarian – who won his second Oscar for it – I never thought Colman was overshadowed: as the despairing daughter of a dementia-afflicted man, she effortlessly caught the many shades of a caregiver playing a supporting part in someone else’s story – balancing love, concern and guilt with the knowledge that she must find a way to move on with her life, otherwise she might break down herself. Anyone who has been in a comparable situation should be able to relate with every trace of self-doubt or hurt or exasperation that flitted across her expressive face.

****

If Colman played a child struggling with her duties toward a parent in The Father, in her current Oscar-nominated role in The Lost Daughter she plays someone who carries an even greater weight of societal expectation: a mother. On holiday in Greece, as middle-aged college professor Leda observes the shenanigans of a boisterous family around her, she is led into memories of her time as a young mom burdened with the “crushing responsibility” of children – at a point in her life when she was trying to concentrate on her work and make a name in the competitive, exclusionary, often sexist world of academia. Colman vividly depicts Leda’s surfaces – here is someone who tries to be polite and social up to a point but also has an innate impatience and doesn’t suffer fools gladly – while also letting us sense something of her restless inner life: does she really regret some of the choices she made in the distant past, or was it all inevitable? Is it possible to both love your children and, on some level, wish you had never had them?

Colman vividly depicts Leda’s surfaces – here is someone who tries to be polite and social up to a point but also has an innate impatience and doesn’t suffer fools gladly – while also letting us sense something of her restless inner life: does she really regret some of the choices she made in the distant past, or was it all inevitable? Is it possible to both love your children and, on some level, wish you had never had them?

It’s a stunning performance. And yet, to return to the blasphemy that kicked off this piece, I would be a tad annoyed if she were to win best actress this year.

This has nothing to do with the quality of her work, or with the idea that there is someone better or more deserving in the competition. (I am in no position to make such judgements anyway, having watched only one of the other best actress-nominated performances – Nicole Kidman as Lucille Ball in Being the Ricardos. She was okay, though perhaps that’s my bias speaking – only Lucy can play Lucy.) In any case, the idea that Oscars go to the objective “best” in a category is the sort of conceit that only a child can believe in – it has never been true of any competitive awards in the arts.

No, there are other, more whimsical reasons. One is a residue from the nerdy adolescent years I spent being obsessed with the Oscars. Obsessed, not because I hoped that my favourites would win, but because I was interested in the awards’ long history and in their complicated workings: I spent a lot of time poring over analyses and charts and alternate-world scenarios to try and understand how many combinations of factors (apart from merit) went into determining both the shortlist of nominees and the eventual winners.

One of those factors, for example, was the “holdover” prize, a term used for a situation where an admired actor (or director, or sometimes a writer or cinematographer) doesn’t win for their most celebrated work but is compensated later by being awarded for something that most people agree isn’t their best. Much-discussed examples include James Stewart getting best actor In 1940 for what was mainly a solid supporting part in The Philadelphia Story (it was widely seen as a holdover for his iconic role in Mr Smith Goes to Washington the previous year); or Al Pacino winning for Scent of a Woman decades after not winning for The Godfather films or Dog Day Afternoon. This also applies to the lifetime-achievement awards given to legends who never won in the competitive categories in their prime.

But if the holdover is a well-known Oscar phenomenon, what about the inverse situation, where an actor is awarded relatively early in a career for what might not be his or her most worthy work… and then, just a few years later, they do something truly extraordinary but now the feeling in the air is: should this person get a second award so soon?

Olivia Colman might be in that situation this year. A mere three years ago she won best actress for a very flamboyant role as the depressed, tantrum-throwing Queen Anne in The Favourite. She was terrific (again, lest I haven’t made it clear: Colman is terrific in everything), but the rub was that Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz had equally central parts (the film was really about their characters’ rivalries) and were very good in less showy roles; and yet they were relegated to the supporting actress category. Given this minor injustice, the old Oscar pedant in me feels it's too soon for Colman to get another best actress prize.

The other reason has to do with a weird protectiveness I feel about Colman – I’d prefer her to stay relatively unsullied by Oscar’s claws.

Though the awards throughout their history have tried to balance or spread the acting honours among a wide swathe of performers, they occasionally latch on to a few actors as perpetual favourites or contenders. And when Oscar fixates thus on people, more often than not it has the effect of straitjacketing them, making them look boringly honourable.  Consider Katharine Hepburn, who was one of my favourite actors (in a certain sort of role) and more importantly one of my favourite public personalities of the last century, but whose final three best actress Oscars – all given after she turned 60 – had an element of myth-making and canonising to them. (One of those awards – in the hot-button “issue” film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner – came a few months after Hepburn’s long-time partner Spencer Tracy died, and she saw it as much as a posthumous award for him; the last, for On Golden Pond, felt like another sympathy gesture for a film that had brought two screen legends – her and the terminally ill Henry Fonda – together for the first time in their seventies.) Hepburn didn’t win for some excellent performances earlier in her career in small gems like Alice Adams or Summertime, but the floodgates opened once she went past a certain age and could be treated as a grande dame performing nobly in “significant” works.

Consider Katharine Hepburn, who was one of my favourite actors (in a certain sort of role) and more importantly one of my favourite public personalities of the last century, but whose final three best actress Oscars – all given after she turned 60 – had an element of myth-making and canonising to them. (One of those awards – in the hot-button “issue” film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner – came a few months after Hepburn’s long-time partner Spencer Tracy died, and she saw it as much as a posthumous award for him; the last, for On Golden Pond, felt like another sympathy gesture for a film that had brought two screen legends – her and the terminally ill Henry Fonda – together for the first time in their seventies.) Hepburn didn’t win for some excellent performances earlier in her career in small gems like Alice Adams or Summertime, but the floodgates opened once she went past a certain age and could be treated as a grande dame performing nobly in “significant” works.

More recent entrants in this club of patron saints have included Meryl Streep, Daniel Day-Lewis and, most recently, Frances McDormand, who won a third best actress Oscar last year for Nomadland (a film that you’re only supposed to watch in reverential silence and discuss in hushed tones). McDormand is a wonderfully unpredictable presence who first won for the lovely, offbeat Fargo, but now she has been shoehorned into the Hall of Worthies, doomed for all time to bear the insignia “three-time Academy Award winner” before her name.

Maybe, in the end, that’s all there is to my wish: I want Olivia Colman to escape the morbidly respectable fate of becoming a multiple Oscar winner while she’s still just in her forties. She’s too dynamic and too interesting for such overrated honours. Even as a queen, she looks better kicking up her heels in a behind-the-scenes dance act than sitting on a throne with a heavy crown on her head and a stoical look on her face.

[Earlier First Post pieces are here]

March 16, 2022

On the new marital (erotic) thriller Deep Water

Had hoped for more from this new film based on Patricia Highsmith’s 1957 novel (and directed by Adrian Lyne, who is still making erotic thrillers in his eighties… which could be part of the problem here). The film retains the snails that so often appeared in Highsmith’s writings, but it’s just as sluggish as they are. Wrote this for First Post

Had hoped for more from this new film based on Patricia Highsmith’s 1957 novel (and directed by Adrian Lyne, who is still making erotic thrillers in his eighties… which could be part of the problem here). The film retains the snails that so often appeared in Highsmith’s writings, but it’s just as sluggish as they are. Wrote this for First Post-----------------

Anyone familiar with the dark and caustic writings of Patricia Highsmith will know that her work didn’t show a high regard for human nature – or for sacred human institutions like marriage. Across a range of short stories, Highsmith depicted marriage as a form of self-cannibalising in which personalities are swallowed up, laying bare the many ways in which spouses can wound, dominate or play games with each other (while also masochistically inflicting hurt on themselves).

For instance, in the chilling “When the Fleet was in at Mobile”, a diffident woman (who might be an unreliable protagonist) escapes her bullying husband after administering him a dose of chloroform – but finds that it isn’t so easy to return to a happy past. Even in the more light-hearted Highsmith stories about husbands and wives, you learn not to bat an eyelid when you come across a passage like this: “Sarah’s idea was to kill Sylvester with good food, with kindness, with wifely duty.” (That’s from “The Fully Licensed Whore, or The Wife”.) Or this from “The Breeder”, where a man finds himself with 17 children after barely a decade of marriage: “He was just sane enough to realise that his mind, so to speak, was gone. He was aware that he didn’t want to go back to work, didn’t want to do anything.”

I haven’t read Highsmith’s 1957 novel Deep Water, but I had no trouble identifying her touch in the broad outlines of the new film by that name – even if the story has been modernised and altered. (In an early scene, an oddball mix of the very new and the very quaint, a little girl asks Alexa to play “Old MacDonald Had a Farm”.)

I haven’t read Highsmith’s 1957 novel Deep Water, but I had no trouble identifying her touch in the broad outlines of the new film by that name – even if the story has been modernised and altered. (In an early scene, an oddball mix of the very new and the very quaint, a little girl asks Alexa to play “Old MacDonald Had a Farm”.)Deep Water centres on the relationship between Vic (Ben Affleck) and Melinda (Ana de Armas), with their interactions making it obvious (even for those who go in knowing nothing about the plot) that there is something off, or unconventional, about their marriage. On the one hand they have been together for years, they have a child, the family appears stable (they even get a puppy!), and they seem to socialise often with a common group of friends. But Vic and Melinda don’t sleep in the same room, and when he sees her making out with a young man at a party, it isn’t presented as a shocking betrayal that will blow their relationship apart: Vic is disturbed but not exactly surprised, and he deals with the situation in his own private way – by telling the young man, pleasantly, that he had killed another of Melinda’s special “friends”.

This little episode sets the plot in motion, paving the way for the tension that arises when the body of that missing friend turns up a while later. More deaths follow. It’s hard to really talk about specifics, so I’ll be vague and say that our ideas about Vic – what he is and isn’t capable of doing – change as the story progresses (perhaps some of it comes as a surprise to him too). But around halfway through, as the ambiguity of the early scenes is lost and we get a clearer sense of what exactly is happening, the film also becomes more predictable and refuses to gather steam as a thriller.

****

While many of Highsmith’s writings (not just her famous Ripley novels) have been adapted for the screen, it isn’t the case that the adaptations are always faithful: arguably the most well-known film based on a Highsmith book, Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951), made a crucial alteration in the book’s plot, allowing the leading man to retain his moral compass in keeping with the pressures of studio-era Hollywood. So Deep Water shouldn’t be judged on how closely it adheres to its source.

But this point has to be made: by moving the story to the present day, the film inevitably changes the way we look at its characters and their situation. What was transgressive, dangerous or at least very uncommon in small-town America in the 1950s – an open marriage and its effect on a community – is much less so today, and this blunts the edge of the main situation. What director Adrian Lyne and his writers Zach Helm and Sam Levinson seem to have done to compensate for this is to make the Vic-Melinda relationship more sexually charged, with much of that current coming from the arrangement between them: Vic is often an inexpressive, unemotional fellow (which partly accounts for Melinda’s frustrations), but he is most turned on by his wife, becomes most alive and passionate, when he sees or imagines her in sexual situations with other men.

So this is a thriller that’s largely about male jealousy and what it might lead to. In keeping with that focus, the perspective we get throughout is Vic’s: the things he sees or hears, or thinks about. Even while living in the same house, he often watches Melinda like a stalker, spying on her – while she speaks on the phone or dances with someone – through stairways and halls and corridors. He isn’t a “normal” husband, he says more than once – he doesn’t want to control her. But what is he doing exactly? What game are they playing? The real workings of their relationship (how they fell in love in the first place, how things changed over time) never quite become clear. And this is largely because we don’t get Melinda’s untrammelled point of view – we might conjecture that she does what she does because she is deeply in love with Vic and wants to stoke his hidden fires, but there isn’t enough evidence of this.

So this is a thriller that’s largely about male jealousy and what it might lead to. In keeping with that focus, the perspective we get throughout is Vic’s: the things he sees or hears, or thinks about. Even while living in the same house, he often watches Melinda like a stalker, spying on her – while she speaks on the phone or dances with someone – through stairways and halls and corridors. He isn’t a “normal” husband, he says more than once – he doesn’t want to control her. But what is he doing exactly? What game are they playing? The real workings of their relationship (how they fell in love in the first place, how things changed over time) never quite become clear. And this is largely because we don’t get Melinda’s untrammelled point of view – we might conjecture that she does what she does because she is deeply in love with Vic and wants to stoke his hidden fires, but there isn’t enough evidence of this. The result is an uneven, oddly paced film that feels like some connecting scenes mysteriously went missing in the editing room. It has a couple of funny moments early on, and other promising touches: for instance, the snails that Vic is breeding and seems to be obsessed with. (Snails were a Patricia Highsmith obsession too, they appear in many of her stories, including the horror stories. And they seem to fit this tale for another reason: the creatures have fluid sex lives, being hermaphrodites with both male and female reproductive organs.) But the scenes where the protagonists banter, or fight, aren’t anywhere near as electric as they might have been, and one key character – a writer who seems to suspect Vic of very dark things and see this situation as material for a new novel – never quite makes sense. (By the climax, he comes across as unintentionally funny.)

Most of all – and this may be the cardinal sin given that it’s directed by Lyne, whose stock in trade has been middlebrow erotic thrillers like Fatal Attraction, 9 ½ Weeks, Unfaithful and Indecent Proposal – this isn’t a particularly sexy film. And this despite the presence of Ana de Armas who manages to be both sensuous (even while she is presented to us through Vic’s controlling, insecure gaze) and a basically sympathetic, melancholy figure. If she had been given more screen time, if we had a clearer sense of what Melinda feels about her situation and what exactly is at stake for her, this may have been a better film all around.

Most of all – and this may be the cardinal sin given that it’s directed by Lyne, whose stock in trade has been middlebrow erotic thrillers like Fatal Attraction, 9 ½ Weeks, Unfaithful and Indecent Proposal – this isn’t a particularly sexy film. And this despite the presence of Ana de Armas who manages to be both sensuous (even while she is presented to us through Vic’s controlling, insecure gaze) and a basically sympathetic, melancholy figure. If she had been given more screen time, if we had a clearer sense of what Melinda feels about her situation and what exactly is at stake for her, this may have been a better film all around. A podcast about 50 years of The Godfather

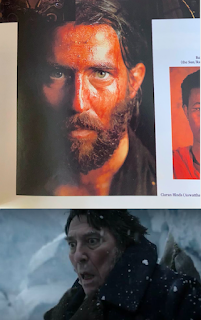

P.S. in the podcast I mention some of those great dissolves in The Godfather Part II, transitioning from Michael in the present to Vito in the past. Here are two of them: the second scene, as the writer Ryan Gilbey noted once, makes it seem like Michael is being absorbed into his father’s body. (Think about it in a certain light and it also looks like a moment from a Cronenberg film like The Brood. Or from the creepy opening-credit sequence of De Palma's Sisters.)

P.S. in the podcast I mention some of those great dissolves in The Godfather Part II, transitioning from Michael in the present to Vito in the past. Here are two of them: the second scene, as the writer Ryan Gilbey noted once, makes it seem like Michael is being absorbed into his father’s body. (Think about it in a certain light and it also looks like a moment from a Cronenberg film like The Brood. Or from the creepy opening-credit sequence of De Palma's Sisters.) For a very long time (before the 1995 film Heat was made) these scenes were also the answer to the movie-nerd trick question “Have Al Pacino and Robert De Niro ever appeared in the same frame in a film?”

March 12, 2022

Nightmare Alley – the old one and the new one (and a discussion about “carnival noir”)

A belated sequel to the film noir discussions I had with my online group a year ago. As some of you would know, Guillermo Del Toro’s new film Nightmare Alley is one of the best picture nominees at the Oscars this year. Based on a 1946 novel by William Lindsay Gresham, it centres on a young drifter named Stanton who goes from being a carnival worker to swindling rich people as a mind-reading “spiritualist”. The story was first filmed in 1947, with Tyrone Power uncharacteristically cast in the lead – the film didn’t do too well when it came out, but it developed a cult following in later decades and is now viewed as a key work of that incredibly rich period for film noirs, the late 1940s.

I watched both films earlier this week, and enjoyed them. (Note: Del Toro, though he’s a huge movie enthusiast himself, sees his version as a direct adaptation of the novel rather than a remake of the 1947 film. I haven’t read the book, but it’s easy to see that the new film could do more explicit things with the subject matter than a 1940s film could.) I thought it might be interesting to have a discussion not just about the two versions but also more generally about that sub-genre of American cinema, the dark carnival narrative set in a subterranean world populated by social outcastes or “geeks”. This could include films that are set entirely in carnivals or circuses or fairgrounds – like the 1932 classic Freaks – or films with important scenes in that dangerous-seeming environment: e.g. Orson Welles’s Lady from Shanghai or Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train.

I watched both films earlier this week, and enjoyed them. (Note: Del Toro, though he’s a huge movie enthusiast himself, sees his version as a direct adaptation of the novel rather than a remake of the 1947 film. I haven’t read the book, but it’s easy to see that the new film could do more explicit things with the subject matter than a 1940s film could.) I thought it might be interesting to have a discussion not just about the two versions but also more generally about that sub-genre of American cinema, the dark carnival narrative set in a subterranean world populated by social outcastes or “geeks”. This could include films that are set entirely in carnivals or circuses or fairgrounds – like the 1932 classic Freaks – or films with important scenes in that dangerous-seeming environment: e.g. Orson Welles’s Lady from Shanghai or Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train.

(The carnival was a very important space in American pop culture of a certain period, definitely from the 1920s to the 1950s – in some books and films it has almost as transformative a function as the forest/aranyak has had over a much longer period in literature, ranging from the vanns of Indian mythology to Shakespeare’s Arden. And I think Stanton’s journey in Nightmare Alley is a fine example of the carnival as portal or distorting mirror.) I have sent prints of the films to my online group, and hope to schedule a discussion for next week or next weekend. Anyone else who’s interested, let me know (mail me at jaiarjun@gmail.com) and I’ll send the films across.

(The carnival was a very important space in American pop culture of a certain period, definitely from the 1920s to the 1950s – in some books and films it has almost as transformative a function as the forest/aranyak has had over a much longer period in literature, ranging from the vanns of Indian mythology to Shakespeare’s Arden. And I think Stanton’s journey in Nightmare Alley is a fine example of the carnival as portal or distorting mirror.) I have sent prints of the films to my online group, and hope to schedule a discussion for next week or next weekend. Anyone else who’s interested, let me know (mail me at jaiarjun@gmail.com) and I’ll send the films across.

March 8, 2022

“Whoa, that’s the same person?” (and other thoughts in the binge-viewing era)

(Did this piece for the Economic Times. More soon on other epiphanies involving performers whom one sees in different contexts across shows and films)

------------------- A few months ago I watched the veteran Irish actor Ciaran Hinds play Julius Caesar in the series Rome. Hinds has been a familiar presence in many films and shows (he is an Oscar nominee this year for Belfast), and here he was in the Ides of March scene, blood-soaked, flailing about, and Et-Tu-ing. What I didn’t know though was that the same actor had once played the perpetrator of a famous underhanded killing from Indian mythology: the night-time guerrilla attack on the Pandava camp in the Mahabharata. A younger, leaner Hinds was Ashwatthama in Peter Brook’s stage and screen productions of the epic (he also doubled up as Nakula – anyone can – on stage).

A few months ago I watched the veteran Irish actor Ciaran Hinds play Julius Caesar in the series Rome. Hinds has been a familiar presence in many films and shows (he is an Oscar nominee this year for Belfast), and here he was in the Ides of March scene, blood-soaked, flailing about, and Et-Tu-ing. What I didn’t know though was that the same actor had once played the perpetrator of a famous underhanded killing from Indian mythology: the night-time guerrilla attack on the Pandava camp in the Mahabharata. A younger, leaner Hinds was Ashwatthama in Peter Brook’s stage and screen productions of the epic (he also doubled up as Nakula – anyone can – on stage).

I first watched the Brook film in the early 1990s, but have revisited it since, and shown scenes from it during a Mahabharata-in-pop-culture online course I taught with my writer friend Karthika Nair. You could even say I was over-familiar with it. And yet I never made the Hinds connection until I happened to flip through a book about the production. It is one of a few “Whoa! That was the same person?” moments I have had lately, while watching actors across a range of shows and films.  There are too many such epiphanies to list here, but another recent one was the realisation that the educator Kamla Chowdhry in the new historical show Rocket Boys was played by the same actress (Neha Chauhan) who was the salesgirl in Love, Sex aur Dhokha more than a decade ago. LSD was a favourite film back in the day, and I remember wondering what had happened to its lower-profile actors. But it took a perusal of IMDB before I made the connection between the T-shirt-and-jeans-clad Rashmi, emotionally abused by a co-worker, and the elegant Kamla.

There are too many such epiphanies to list here, but another recent one was the realisation that the educator Kamla Chowdhry in the new historical show Rocket Boys was played by the same actress (Neha Chauhan) who was the salesgirl in Love, Sex aur Dhokha more than a decade ago. LSD was a favourite film back in the day, and I remember wondering what had happened to its lower-profile actors. But it took a perusal of IMDB before I made the connection between the T-shirt-and-jeans-clad Rashmi, emotionally abused by a co-worker, and the elegant Kamla.

Such lack of recognition is understandable in some cases: say, when an actor whom one doesn’t know well is heavily made up. (I was astonished to find that the Danish actor David Dencik, from the crime show The Chestnut Man, was also the worried Mikhail Gorbachev, “apologising to friends and enemies” – as a current Russian leader is definitely not doing – in Chernobyl.) But at other times one wonders if the old brain cells and memory receptors are corroding fast due to age.

For obvious reasons I prefer alternate explanations, so here’s one: such disorientation is inevitable in this cluttered era of movie-and-series viewing (or as some nasty people put it, “content consuming”). We have a much larger pool of things to see than ever before: those of us who move outside comfort zones (rather than obediently following algorithms) might, in the same week, watch a Tamil film followed by a Nordic crime series and then a mainstream Hindi film populated by shiny debutants who turn out to be the grandchildren of actors we knew in the 1980s. We encounter a number of performers, across cultures and genres, whom we may have only seen fleetingly before.

How this affects you – or whether you even realise it – also hinges on the type of viewer you are. I am the sort who keeps a film’s or show’s Wikipedia page open while watching it, so I can check little things like an interesting performer’s filmography, or (in the case of a convoluted narrative) a plot point that wasn’t clear. This is partly necessitated by being a professional writer who must take notes, but it is a personality kink too. I don’t understand how people binge their way through show after show after show without taking a break to process what they have just watched (and give their eyes a rest), to think about performance, visual design, narrative structuring. And this isn’t about age-related fatigue: even as a much younger, fresher movie buff, I couldn’t bring myself to watch three or four films back to back at a festival. Which is not to say that such confusion didn’t happen in an earlier time. As a teenager getting into world cinema in the early 1990s (when one didn’t constantly have information on one’s fingertips via the internet), I remember how thrilling it could be to form an impression of a previously unencountered actor’s persona or “type” in a foreign film, and then to subsequently see him or her in a very different role or environment. After watching Toshiro Mifune as the scruffy, bearded Samurai in Edo period settings in Yojimbo and The Hidden Fortress, how weird to see him as a clean-shaven cop, walking the noirish mean streets of 1940s Japan in contemporary clothes in Stray Dog.

Which is not to say that such confusion didn’t happen in an earlier time. As a teenager getting into world cinema in the early 1990s (when one didn’t constantly have information on one’s fingertips via the internet), I remember how thrilling it could be to form an impression of a previously unencountered actor’s persona or “type” in a foreign film, and then to subsequently see him or her in a very different role or environment. After watching Toshiro Mifune as the scruffy, bearded Samurai in Edo period settings in Yojimbo and The Hidden Fortress, how weird to see him as a clean-shaven cop, walking the noirish mean streets of 1940s Japan in contemporary clothes in Stray Dog.

Once, upon realising that Chishu Ryu, the old man in the Japanese classic Tokyo Story, was still only in his forties and youthful-looking in other films of the time, I wondered if this was a case of extraordinary versatility or a viewer’s disconnect caused by unfamiliarity. Would a non-Indian viewer, wading bravely into popular Hindi films of the 1980s, have a similar experience if he saw Rajesh Khanna for the first time as the elderly man in Avtar (another Tokyo Story-like film about the generational divide and the neglect of old people)? Would this viewer be astounded if he then saw RK as he was at the time, still playing romantic hero – even if the films and performances were pedestrian?

These are questions to ponder, but alas, one can only think about them – if one does – in the very narrow spaces between our binge-watching sessions.

March 6, 2022

A rant about 'respected' RWA members (and a Cat People video)

A couple of weeks ago there was a nice online discussion about the lovely anthology Cat People (edited by Devapriya Roy), in which I have an essay about my mother and about our cats of old. The link to the video is here. As you can see, around the 30-minute mark, I briefly activate my Activist Mode and rant about people in my neighbourhood who say that we "should think of human welfare instead of animal welfare”. (As if those are mutually exclusive things, and as if we don't already live in a completely human-shaped-and-dominated world.) The most dramatic-sounding thing I said during the session — though in my view it’s still an understatement — was: This planet is almost dead because of thousands of years of “human welfare”. I have written various posts about this broad subject before (this for instance), but the most recent provocation happened at a colony meeting where the agenda was for the AWBI to mediate between those who feed dogs and those who have various issues with the colony’s animals and their carers. (I’m trying to choose my words carefully: one of the things we have been encouraged to do as part of these conciliatory efforts is to not use polarising terms such as “animal lovers” and “animal haters”, which pave the way for each side to label, alienate or judge the other. That makes sense to me anyway; for reasons that I won’t get into here, I don’t instinctively think of myself as an “animal lover” or even a “dog lover”. It’s more complicated than that.) Anyway, this meeting began with the amicus curiae, an Animal Welfare Board representative, spelling out the salient issues facing small, congested colonies like ours — including the need to clearly designate feeding spots — and the importance of setting up an “animal welfare committee”. At the very first mention of this dangerous-sounding term “animal welfare”, a Respected Elderly Man cleared his throat very loudly, looked around to make sure that all eyes were on him (this is usually a prelude to terrifying things; we see it all the time at literature festivals when audience questions are invited after a session), and said, in the grand, pause-laden manner of one who thinks he is delivering a scintillating insight (or witticism) that has never before been voiced: “I would like to ask a question. [Solemn pause.] We are hearing this term ‘animal welfare’ a lot. May I ask, is there also such a thing as… *human* welfare?” This particular octogenarian, not surprisingly, was a former RWA president himself. Again not surprisingly, he succeeded in disrupting the flow of the amicus curiae’s measured talk and drawing chuckles from most of the people gathered there: both those who approved of what he was saying and those who wanted to indulge him or “lighten” the atmosphere. *He* wasn’t joking though: he truly, genuinely believed in the validity of what he was saying. And this despite having lived in Saket long enough to know firsthand of a time, a mere 50-55 years ago, when we homosapiens began encroaching on what was then forest land. I try not to be judgemental of people who have led almost fully anthropocentric lives: I know from firsthand experience that it isn’t easy (especially if you’ve always been in an urban environment or if you have large human families to worry about) to develop a serious interest in — to *look closely at and think about* — other species. This June will mark 10 years since my Foxie went. Before she came into my life in 2008, I barely registered the presence of dogs, even though my mother was crazy about them. (Some of the most ardent animal-carers I know have had similar life trajectories. One of them, Hemali Sodhi, has written movingly in her Introduction to The Book of Dog about a time when she was terrified of

A couple of weeks ago there was a nice online discussion about the lovely anthology Cat People (edited by Devapriya Roy), in which I have an essay about my mother and about our cats of old. The link to the video is here. As you can see, around the 30-minute mark, I briefly activate my Activist Mode and rant about people in my neighbourhood who say that we "should think of human welfare instead of animal welfare”. (As if those are mutually exclusive things, and as if we don't already live in a completely human-shaped-and-dominated world.) The most dramatic-sounding thing I said during the session — though in my view it’s still an understatement — was: This planet is almost dead because of thousands of years of “human welfare”. I have written various posts about this broad subject before (this for instance), but the most recent provocation happened at a colony meeting where the agenda was for the AWBI to mediate between those who feed dogs and those who have various issues with the colony’s animals and their carers. (I’m trying to choose my words carefully: one of the things we have been encouraged to do as part of these conciliatory efforts is to not use polarising terms such as “animal lovers” and “animal haters”, which pave the way for each side to label, alienate or judge the other. That makes sense to me anyway; for reasons that I won’t get into here, I don’t instinctively think of myself as an “animal lover” or even a “dog lover”. It’s more complicated than that.) Anyway, this meeting began with the amicus curiae, an Animal Welfare Board representative, spelling out the salient issues facing small, congested colonies like ours — including the need to clearly designate feeding spots — and the importance of setting up an “animal welfare committee”. At the very first mention of this dangerous-sounding term “animal welfare”, a Respected Elderly Man cleared his throat very loudly, looked around to make sure that all eyes were on him (this is usually a prelude to terrifying things; we see it all the time at literature festivals when audience questions are invited after a session), and said, in the grand, pause-laden manner of one who thinks he is delivering a scintillating insight (or witticism) that has never before been voiced: “I would like to ask a question. [Solemn pause.] We are hearing this term ‘animal welfare’ a lot. May I ask, is there also such a thing as… *human* welfare?” This particular octogenarian, not surprisingly, was a former RWA president himself. Again not surprisingly, he succeeded in disrupting the flow of the amicus curiae’s measured talk and drawing chuckles from most of the people gathered there: both those who approved of what he was saying and those who wanted to indulge him or “lighten” the atmosphere. *He* wasn’t joking though: he truly, genuinely believed in the validity of what he was saying. And this despite having lived in Saket long enough to know firsthand of a time, a mere 50-55 years ago, when we homosapiens began encroaching on what was then forest land. I try not to be judgemental of people who have led almost fully anthropocentric lives: I know from firsthand experience that it isn’t easy (especially if you’ve always been in an urban environment or if you have large human families to worry about) to develop a serious interest in — to *look closely at and think about* — other species. This June will mark 10 years since my Foxie went. Before she came into my life in 2008, I barely registered the presence of dogs, even though my mother was crazy about them. (Some of the most ardent animal-carers I know have had similar life trajectories. One of them, Hemali Sodhi, has written movingly in her Introduction to The Book of Dog about a time when she was terrified of

dogs.) But even so, I am sometimes stunned at the realisation that so many “honourable” senior members of our societies — people who have reached high positions in their respective fields — think of other creatures as nothing more than pests that have to be put up with (because, well, all those animal lovers make such a noise). Screenshots of yesterday’s Supreme Court order, misinterpreted by many people as saying that it is no longer permitted to feed street animals, are being used as a bludgeon by countless RWAs to bully animal-feeders even more, especially the ones who don’t have a good support system around them. The gloating messages I have been seeing about this on my colony WhatsApp groups provide a clearer sense of why things are now so bad for this planet than any politically charged Left-vs-Right arguments can. More on this soon. (I wish I could disclose details of some conversations from the meetings or almost-meetings with the RWA, but that would be unwise. Some of it should go into a book anyway.) Meanwhile, do watch the Cat People video if you feel like, and do consider picking up the book too. It's a great collection.

dogs.) But even so, I am sometimes stunned at the realisation that so many “honourable” senior members of our societies — people who have reached high positions in their respective fields — think of other creatures as nothing more than pests that have to be put up with (because, well, all those animal lovers make such a noise). Screenshots of yesterday’s Supreme Court order, misinterpreted by many people as saying that it is no longer permitted to feed street animals, are being used as a bludgeon by countless RWAs to bully animal-feeders even more, especially the ones who don’t have a good support system around them. The gloating messages I have been seeing about this on my colony WhatsApp groups provide a clearer sense of why things are now so bad for this planet than any politically charged Left-vs-Right arguments can. More on this soon. (I wish I could disclose details of some conversations from the meetings or almost-meetings with the RWA, but that would be unwise. Some of it should go into a book anyway.) Meanwhile, do watch the Cat People video if you feel like, and do consider picking up the book too. It's a great collection.February 26, 2022

Bhabha scattering: a shout-out for Rocket Boys

Wrote this short review of the fine new series Rocket Boys, for Reader’s Digest

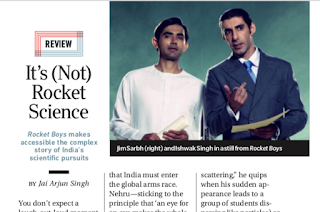

--------------- You don’t expect a laugh-out-loud moment from a discussion about nuclear war – unless you’re watching a black satire like Dr Strangelove. But that’s what happens in one of many memorable scenes in the new series Rocket Boys, a dramatized account of India’s space and nuclear programmes and the physicists who made it possible. It’s 1962, and amidst the chaos of the Chinese invasion of Indian territory, Homi Bhabha (played by Jim Sarbh) is trying to persuade Prime Minister Nehru (Rajit Kapoor) that India must enter the global arms race. Nehru – initially sticking to the principle that “an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind” – expresses concern that Bhabha might be using their close relationship for his own personal agenda. To which an exasperated Homi explodes: “What will I personally do with an atom bomb, Bhai? Bury it in my backyard? Keep it in the Homi Atomic Bhabha Museum?”

You don’t expect a laugh-out-loud moment from a discussion about nuclear war – unless you’re watching a black satire like Dr Strangelove. But that’s what happens in one of many memorable scenes in the new series Rocket Boys, a dramatized account of India’s space and nuclear programmes and the physicists who made it possible. It’s 1962, and amidst the chaos of the Chinese invasion of Indian territory, Homi Bhabha (played by Jim Sarbh) is trying to persuade Prime Minister Nehru (Rajit Kapoor) that India must enter the global arms race. Nehru – initially sticking to the principle that “an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind” – expresses concern that Bhabha might be using their close relationship for his own personal agenda. To which an exasperated Homi explodes: “What will I personally do with an atom bomb, Bhai? Bury it in my backyard? Keep it in the Homi Atomic Bhabha Museum?”

Here and elsewhere, Rocket Boys gets much of its energy from Bhabha’s charismatic, witty presence: whether he is bantering with his mother, or making a science joke (“Bhabha scattering” he quips when his appearance leads to a group of students nervously dispersing like particles), or losing his temper when an unexpected glitch appears on the day of a reactor launch. In the acclaimed web-series Chernobyl, a scientist describes the processes by which stability is maintained inside a nuclear reactor, with the reactivity increased and reduced in turn. (“This is the invisible dance that powers entire cities without smoke or flame. And it is beautiful.”) Sarbh’s excellent performance serves a comparable function for Rocket Boys – it supplies both the necessary power and the lighter, moderating moments. He is well supported by the more low-key Ishwak Singh, who plays the other protagonist – Vikram Sarabhai, whose path first crossed with Bhabha’s in the early 1940s, leading to a friendship and association that was (at least in this telling) sometimes troubled by a clash of ideologies. Rocket Boys begins by tracing the lives of these two men during the lead-up to India’s independence: early disappointments and pitfalls, tentative collaborations, the setting up of institutes that would help realise the new nation’s ambition of self-reliance. And the personal lives too. It could be argued that the series gets a bit weighed down at one stage as it details the courtship and wedding of Vikram and Mrinalini Sarabhai – but it’s hard to blame the show-runners, given that Mrinalini, a celebrated classical dancer and choreographer, was an important figure in her own right; and that the rockier aspects of this marriage provide a good lens for examining gender roles and feminist struggles in this time and milieu. In any case, both Regina Cassandra as Mrinalini and Saba Azad as Homi’s girlfriend Pipsy are strong and elegant presences. It is also creditable – considering how defensive and controlling the families of public figures tend to be – that Mallika and Kartikeya Sarabhai, who were consultants for this series, had no problem with the depiction of their father’s extra-marital relationship with his colleague, the educator Kamla Chowdhry.

Rocket Boys begins by tracing the lives of these two men during the lead-up to India’s independence: early disappointments and pitfalls, tentative collaborations, the setting up of institutes that would help realise the new nation’s ambition of self-reliance. And the personal lives too. It could be argued that the series gets a bit weighed down at one stage as it details the courtship and wedding of Vikram and Mrinalini Sarabhai – but it’s hard to blame the show-runners, given that Mrinalini, a celebrated classical dancer and choreographer, was an important figure in her own right; and that the rockier aspects of this marriage provide a good lens for examining gender roles and feminist struggles in this time and milieu. In any case, both Regina Cassandra as Mrinalini and Saba Azad as Homi’s girlfriend Pipsy are strong and elegant presences. It is also creditable – considering how defensive and controlling the families of public figures tend to be – that Mallika and Kartikeya Sarabhai, who were consultants for this series, had no problem with the depiction of their father’s extra-marital relationship with his colleague, the educator Kamla Chowdhry.

Other famous personalities move across this firmament too: Nobel laureate CV Raman, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira Gandhi, and an earnest young scientist named APJ Abdul Kalam who plays a big role in the later episodes. Some incidents are fictionalised, or at least heavily dramatized; one important character is a composite of various real-life figures who were Bhabha’s rivals and may have been jealous of his connections. But to its credit, Rocket Boys, even while it presents Bhabha and Sarabhai as heroes for a young country, never glosses over their social privileges. Its depiction of Nehru is pragmatic and layered too: on one hand he is shown as a conscientious, self-examining leader, a man of progress genuinely encouraging the scientific spirit; on the other hand, in his interactions with Homi there is a sense of a cushy insiders’ club at work. All this raises the show above easy categories of “liberal”, “conservative”, “elitist”, “pro-Congress” or “anti-Nehru” – it is, foremost, a well-designed narrative about the many vagaries of history, politics and development. And it makes physics seem exciting, which is an achievement in its own right.

P.S. this is a comment I wrote in response to a question on Facebook, about the alleged inaccuracies in the show as well as the politics of creating a fictional antagonist (Raza Mehdi) who resents Homi Bhabha’s success and who happens to be Muslim:

I think it's very useful to have information about the inaccuracies in a dramatised historical series (I read similar very critical pieces about Chernobyl and The Crown, two shows that I liked better than Rocket Boys) - it can be illuminating and can open doors to further reading about the subject if you're that way inclined. And a viewer should never be so naive as to take everything in a historical series at face value anyway. Though at the same time it's good to be aware that the people who are pointing out the "inaccuracies" or "problems" also often have their own biases and blind spots (or in some cases might be too close to or too emotionally invested in the subject - as a nuclear physicist nitpicking about the technical flaws in Chernobyl would be; or an anti-monarchist raging about what they interpret as a sympathetic depiction of a royal).  About the Raza Mehdi character in Rocket Boys: I am still unsure why they felt the need to fictionalise Meghnad Saha (what I heard was that Mehdi wasn't based on a single figure but was a composite). But personally I didn't think there was anything conniving about making him a Muslim, because I didn't see him as a "villain" at all: I thought he was depicted largely as a sympathetic, sincere character, and some scenes -- like the one in the Parliament where he questions if this really is a democracy -- were geared towards making the viewer think about the elitist circle surrounding Nehru. (In fact, in the very first scene where Nehru appears in episode 4, where Mehdi goes up to him at the party and Nehru is clearly being distant with him, even fobbing him off, I found myself feeling sorry for Mehdi - and even wondered if the show was going to make villains of Nehru and his coterie.)

About the Raza Mehdi character in Rocket Boys: I am still unsure why they felt the need to fictionalise Meghnad Saha (what I heard was that Mehdi wasn't based on a single figure but was a composite). But personally I didn't think there was anything conniving about making him a Muslim, because I didn't see him as a "villain" at all: I thought he was depicted largely as a sympathetic, sincere character, and some scenes -- like the one in the Parliament where he questions if this really is a democracy -- were geared towards making the viewer think about the elitist circle surrounding Nehru. (In fact, in the very first scene where Nehru appears in episode 4, where Mehdi goes up to him at the party and Nehru is clearly being distant with him, even fobbing him off, I found myself feeling sorry for Mehdi - and even wondered if the show was going to make villains of Nehru and his coterie.)

Anyway, at the very end of the show, the true "betrayal" (if one has to think in hero-villain binaries) comes from elsewhere, right? Not from the Muslim character.

February 18, 2022

Runaway buffaloes, luckless dogs and some unforgettable humans – on S Hareesh’s short-story collection Adam

(Wrote this review of a super new book for Open magazine)

-------------------

Among the many electric passages in Adam, a collection of stories by the Malayali writer S Hareesh, my favourite came at the end, in a tale called “Night Watch”. An old man has died and his long-time enemy has come straight to the house, apparently to help with the last rites but also to gaze upon the dead body with some satisfaction. Soon after this we are told of a public confrontation between the two adversaries a week earlier – a verbal battle that escalated to seemingly apocalyptic dimensions, with abuses so rich and profound that the story’s narrator can’t even specify what they are.  “Gesturing dramatically with his hands, Sankunniyaasan uttered a phrase that annihilated all moral values in the collective mind of the audience,” we learn – and then “Madhavan delivered a response that could not have been possible even in the farthest reaches of a nightmare.”

“Gesturing dramatically with his hands, Sankunniyaasan uttered a phrase that annihilated all moral values in the collective mind of the audience,” we learn – and then “Madhavan delivered a response that could not have been possible even in the farthest reaches of a nightmare.”

“Those who were still listening to the barrage of blight felt that all the words they had spoken, or would ever speak, in their entire lives were forever filthy.”

Breath-taking in its playfulness and intensity, this passage shows a distinct aspect of Hareesh’s work – the ability to work in the epic mode and the realistic or mundane one at the same time. As the episode builds, one thinks of warriors in ancient literature – say, Bheeshma and Parashurama in the Mahabharata – assailing each other with world-destroying weapons like the Brahmastra. (“They began with a few choice but ordinary words, but the sparks from these spread until a forest fire of larger and meatier words blazed […] the enemies turned into wizards who conjured up new and imaginative obscenities, slicing and splicing existing ones.”) And yet, one never forgets that this is a real setting involving two aged, mundu-clad men who have just participated (without speaking to each other) in a card game behind a paan shop.

Somehow the much-used descriptor “magic realism” doesn’t seem an adequate description of this effect; the events being described in most of these stories aren’t mystical or otherworldly (with one or two possible exceptions), but the nature of the telling creates that impression. Or maybe something about the setting lends itself to poetic exaggeration.

There are unexpectedly funny little moments in all these stories. In “Kavyamela”, when a blind man revisits a large rock off which he had once fallen and broken his leg, we are told that he “walked up to the rock and sat on it as if in vengeance”. Dogs in heat are described as “flirting” or “canoodling” with each other. Though death is a theme that runs through this book, the treatment can be simultaneously comic and tragic. For instance, in “Magic Tail”, a young woman has to transport her father’s dead body a long way home; it’s a sad occasion and her grief is genuine, but somehow, in an intriguingly matter-of-fact way, the journey also becomes an occasion for flirtatious banter – and possibly more – between her and the acquaintance who is driving her (in a Maruti Omni converted into a hearse). It is as if this proximity to death has awakened their sexuality.

Elsewhere, an ambiguity surrounds death itself. “I’ve finally defeated you,” thinks Sankunniyaasan, looking at Madhavan’s dead body in “Night Watch” – but has he really, or is there more to come? Will they continue their eternal battle in the afterlife? Two of the most haunting stories in this collection imply a blurring of the line between living and not-living. In “Alone”, a man on his way home from work gets off the bus and finds himself on a dark, deserted path, not sure of even the direction he must walk in – and soon realises that the reason for his fear and sense of dislocation is that it is the first time he has been completely alone. (“He was never alone in the bus because he was not the one who got out last.”) This strange, compelling tale is open to interpretation – perhaps what is being described is the loneliness of the afterlife. (“What if, in other places, the sun had risen several times? What if this place would never again see the light of day? What if eons had gone by since his wife and children had stopped crying for him?”) A similar tone is achieved in “Death Notice”, which describes many deaths of non-human creatures – a cow dies after a childbirth gone badly wrong, a new-born litter of puppies are killed, a turtle is caught and cooked – and then gives us two men playing a macabre game involving newspaper obituaries, before a final twist in the tale.  Then there are the two longest pieces in the collection, “Maoist” and the title story “Adam”, both of which centre on animals but are about the intersection of many worlds: human and canine, human and bovine, and of course the many divides and conflicts within our species. “Adam” can loosely be summarised as a story about four puppies from the same litter, each living out a very different destiny, but that wouldn’t begin to convey the full scope of this tale, and how smoothly it tells its many stories. One pup, who becomes Victor, ends up working as a police dog, the pride of the force for years – though even this doesn’t preclude a sad end. Another, Candy, leads a comfortable life until her master gets married to someone who doesn’t much like dogs. Yet another, Arthur, gets a new name after being kidnapped. Their circumstances change over time, and the narrative takes the shape of vignettes, one flowing into the next, as if the narrator is a celestial book-keeper recounting the highlights of various lives. In another writer’s hands it would seem like the animals are being used only as metaphors for human struggles, but that isn’t the case here – the dogs are dogs, what happens to them feels organic and truthful, and in any case we are also privy to the stories and shifting fortunes of the actual humans in the story.

Then there are the two longest pieces in the collection, “Maoist” and the title story “Adam”, both of which centre on animals but are about the intersection of many worlds: human and canine, human and bovine, and of course the many divides and conflicts within our species. “Adam” can loosely be summarised as a story about four puppies from the same litter, each living out a very different destiny, but that wouldn’t begin to convey the full scope of this tale, and how smoothly it tells its many stories. One pup, who becomes Victor, ends up working as a police dog, the pride of the force for years – though even this doesn’t preclude a sad end. Another, Candy, leads a comfortable life until her master gets married to someone who doesn’t much like dogs. Yet another, Arthur, gets a new name after being kidnapped. Their circumstances change over time, and the narrative takes the shape of vignettes, one flowing into the next, as if the narrator is a celestial book-keeper recounting the highlights of various lives. In another writer’s hands it would seem like the animals are being used only as metaphors for human struggles, but that isn’t the case here – the dogs are dogs, what happens to them feels organic and truthful, and in any case we are also privy to the stories and shifting fortunes of the actual humans in the story.

A similar effect is achieved, though perhaps in a more focused way, in the brilliant “Maoist”, which may be the most well-known story here since it was the seed of Lijo Jose Pellissery’s acclaimed 2019 film Jallikattu (which was scripted by Hareesh and selected as India’s entry to the Oscars). “Maoist” uses the story of two runaway buffaloes (in the film there is one animal) as a funny, hard-hitting sociological study of an entire village and its class politics. As the hunt for the buffaloes gathers pace, we are introduced to a range of characters who represent different hierarchies and types. The family of Varky the butcher has the nickname “Kaalan” not because Kaalan, the God of death, rides on a buffalo, but because of the clan’s extraordinarily long legs (or “kaalu”), which makes them instantly identifiable. We learn about the politics of meat-eating, slaughter and packaging (local dignitaries get meat cut into fine, neat pieces; lesser customers get carelessly hacked “seconds”.) From landowners to rowdies to Communists, everyone is affected by the incident. A young man posts a video of the buffalo chase on Facebook, leading to “likes” and “shares” and astonished comments from around the world.

Here again, Hareesh’s prose often operates in a grand meter without losing sight of the everyday: a passage about how the pursuit causes ebbs and flows in different people’s destinies begins with the showy line: “Presently, as though ordained by God himself, the land witnessed the complete fall from grace of two of its prominent personages even as one of its lesser citizens emerged from a life of insignificance…” To watch Jallikattu after reading this story is to marvel at how thirty-odd pages of conversational prose can create such an elaborate universe, within the borders of a small Keralite village – while also spawning a visually striking film with long passages of silence.

Reading Hareesh’s novel Moustache (originally Meesha; also translated into English by Jayasree Kalathil) a couple of years ago, I loved the scope and ambition of the narrative, but also felt it was too exhausting to take in all at once; that it may have worked better as a collection of linked but standalone short stories. The pieces in Adam suggest that Hareesh is in his element in the short-story format. These rich, imaginative tales need more than one reading to fully process the ways in which they blur the line not just between humans and other forces of nature, but also between life and death, dreaming and wakefulness.

(Here is a piece about Hareesh’s Moustache)

February 17, 2022

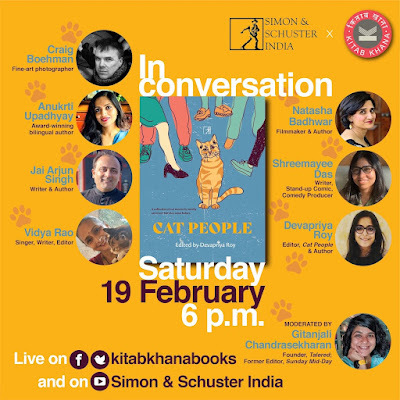

A few Cat People, in conversation

This conversation around our beloved cat anthology is happening on the 19th, at 6 pm - with the editor Devapriya Roy and a few of the contributing writers. Please mark your calendars and try to be there. (You can go to the Kitab Khana Facebook page or the Simon & Schuster India YouTube page for the live video.)

This conversation around our beloved cat anthology is happening on the 19th, at 6 pm - with the editor Devapriya Roy and a few of the contributing writers. Please mark your calendars and try to be there. (You can go to the Kitab Khana Facebook page or the Simon & Schuster India YouTube page for the live video.)A little more about Cat People and The Book of Dog in this post.

Jai Arjun Singh's Blog

- Jai Arjun Singh's profile

- 11 followers