Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 19

May 4, 2021

Home and the world: a short review of Nomadland

(Have been doing some very short, snippet-ish reviews lately for India Today, Reader’s Digest and a couple of other publications. Don’t usually feel motivated enough to share those, but here is a little piece about Nomadland, which won a few top Oscars last month – and which, as it happens, was the first film I watched in a hall after more than a year of abstinence. Now, of course, it looks like it will be the last such experience for several months.

Also: with all the Satyajit Ray talk of the past week, I couldn't resist a "Ghare Baire" reference in the title of this post)

---------------

Some of the most stimulating moments in film history have occurred at points where documentary and constructed narrative intersect, or even blur into each other. Nearly a hundred years ago, Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North – about the Inuit people of the Canadian Arctic – introduced movie viewers to the daily rigours of a world they knew little about; but doing this entailed a certain degree of artifice and the use of scripted scenes, such as the one where a hunter is made to use a harpoon rather than a gun. A century on, Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland, which won the best picture and director Oscars this year, also melds unflinching reality with a fictional narrative, and similarly does this while chronicling lives outside the mainstream: in this case, the van-dwelling “nomads” of modern-day America, who live on the road and form communities and camps to help each other.

There are scenes in this film that could easily have come out of a straight documentary, including the appearances by real people – such as Bob Wells, president of the Homes on Wheels Alliance – speaking as if being interviewed for the camera. Yet, in adapting its script from a non-fiction book by Jessica Bruder, Nomadland organises itself around an invented character. After losing her job during the Great Recession, the recently widowed Fern (played by Frances McDormand, her face a study in both desolation and hope, much like the landscape she moves through) hits the outdoors with her van and gradually finds a support system, or a series of support systems. In the process, through her eyes, we learn about this vital culture and way of life.

There are scenes in this film that could easily have come out of a straight documentary, including the appearances by real people – such as Bob Wells, president of the Homes on Wheels Alliance – speaking as if being interviewed for the camera. Yet, in adapting its script from a non-fiction book by Jessica Bruder, Nomadland organises itself around an invented character. After losing her job during the Great Recession, the recently widowed Fern (played by Frances McDormand, her face a study in both desolation and hope, much like the landscape she moves through) hits the outdoors with her van and gradually finds a support system, or a series of support systems. In the process, through her eyes, we learn about this vital culture and way of life.

So here is a professional actress playing a scripted character and interacting with real-life nomads who are playing themselves – or rather, versions of themselves. (One person, Swankie, is shown as dying of cancer in the film though she is still alive in reality.) Nomadland has verisimilitude but also a cinematic sweep and a sense of the innately dramatic moment. On the whole I admired it – from a distance – more than I felt emotionally touched by it, but in a few scenes, when an immediate connect took place, the effect was devastating: take the moment when a friend of Fern, trying too hard to be helpful, accidentally breaks her plates, and we see how shattered she is – with nothing underlined, one senses how much these physical belongings (which probably carry memories of her time with her husband) meant to her, even though she is now leading a life that involves letting go of possessions. It feels strange, at a time when we are all being asked to stay indoors, to watch the unsheltered Outside being presented as a character in itself – and as a way of life that is nourishing even as it is risky. But this is a story about being adrift and tethered at once. For some, its opening and closing scenes may evoke John Ford’s classic The Searchers (which is also about new and fluid definitions of “home”), but Nomadland, even as it continues the legacy of the revisionist Western, is essentially a one-of-its-kind film about a new time and place, heartfelt in its contrasting of Fern’s chosen life with the more structured possibilities that might be available to her.

It feels strange, at a time when we are all being asked to stay indoors, to watch the unsheltered Outside being presented as a character in itself – and as a way of life that is nourishing even as it is risky. But this is a story about being adrift and tethered at once. For some, its opening and closing scenes may evoke John Ford’s classic The Searchers (which is also about new and fluid definitions of “home”), but Nomadland, even as it continues the legacy of the revisionist Western, is essentially a one-of-its-kind film about a new time and place, heartfelt in its contrasting of Fern’s chosen life with the more structured possibilities that might be available to her.

May 1, 2021

Fathers and sons: remembering Lalit Behl in two fine films

The actor Lalit Behl died of Covid-related complications on the 23rd. I wrote this short piece for First Post about his wonderful performances in Mukti Bhawan and Titli (the first of which -- centred on the idea that dying can be a leisurely, contemplative affair -- makes for surreal viewing in the current situation).

------------------

In one of many hard-hitting scenes in the 2014 film Titli – about a law-breaking, lower-middle-class Delhi family and a young man who wants to escape it like a butterfly fleeing a chrysalis – there is an explosion of violence from the eldest son Vikram. It is unsettling, claustrophobic, rage-filled, and much of the viewer’s attention will understandably focus on Ranvir Shorey’s visceral performance as Vikram – yet one’s eyes are drawn also to the family patriarch, in white kurta-pyjama, shuffling in and out of the cluttered frame, watching this ferocious battle between his sons. He mutters under his breath, nonchalantly dips biscuits in his cup of tea even as people scream around him; his eyes manage somehow to be droopy and shifty at the same time.

Lalit Behl plays this small but indelible role (in a film directed by his son Kanu) and he is pitch perfect. For much of the narrative, the father is in the background – but in his unobtrusive way he is keeping an eye on the power equations within the dysfunctional family, and moments like this suggest there’s more to him than meets the eye. Later, in a telling little exchange with his daughter-in-law, he proposes that the family go together to Vaishno Devi, where he had gone years ago with his wife: “Usske baad maine haath nahin uthaaya kisi pe.” (“After that I never raised my hand on anyone.”)

Lalit Behl plays this small but indelible role (in a film directed by his son Kanu) and he is pitch perfect. For much of the narrative, the father is in the background – but in his unobtrusive way he is keeping an eye on the power equations within the dysfunctional family, and moments like this suggest there’s more to him than meets the eye. Later, in a telling little exchange with his daughter-in-law, he proposes that the family go together to Vaishno Devi, where he had gone years ago with his wife: “Usske baad maine haath nahin uthaaya kisi pe.” (“After that I never raised my hand on anyone.”)

Without clearly spelling anything out, that line – and the insouciant way in which it is delivered – hints at a history of violence in a family ridden with masculine energies: the effect that his upbringing probably had on his sons, the fount of the anger and despair that runs through the narrative. It gives heft to the film, and helps us understand the protagonist and his rebellion.

Behl, who died on April 23 aged 71, had a long career in theatre and television as actor, director and producer, but his most notable film performances over the past decade were as two different sorts of fathers in two fine, low-key productions. Titli was the first of these, but the longer role was in Shubhashish Bhutiani’s Mukti Bhawan (English title Salvation Hotel) where Behl plays Daya, a man who believes his time has come and decides to go to Benares to await death. In the process he greatly inconveniences his busy son Rajiv, who feels obliged to go along for what could be an interminable stay. “Tez chalao,” Rajiv tells the cab-driver when they are on their way to Benaras; “Dheere chalo,” the father says – I don’t want to die before we get there. The two men, with their contrasting attitudes and priorities, will soon find themselves together in a place where time stands still. Mukti Bhawan is a comedy-drama that effortlessly weaves droll little moments into the fabric of a bleak larger picture – the essential sadness imbuing the story is only felt with hindsight. And in the same way that Behl’s performance in Titli manages to be both placid and faintly menacing, his performance here seamlessly covers two modes. On the one hand, there is the poignant seriousness of Daya’s desire to prepare for his end; on the other hand, there is the surreal effect this proclamation has on his family, especially his son. In a scene midway through the film where Daya thinks he is dying at last, he expresses remorse to Rajiv for having poured cold water on his childhood dreams: “You used to write such innocent poetry, but I never let you bloom. I have been such a bad father.” Behl’s work here accommodates both the tenderness of this “deathbed” moment as well as the sheepishness of the morning after when Daya – still very much alive and feeling better – replies with a nod of his head and a “Fit” when his son asks how he is.

Mukti Bhawan is a comedy-drama that effortlessly weaves droll little moments into the fabric of a bleak larger picture – the essential sadness imbuing the story is only felt with hindsight. And in the same way that Behl’s performance in Titli manages to be both placid and faintly menacing, his performance here seamlessly covers two modes. On the one hand, there is the poignant seriousness of Daya’s desire to prepare for his end; on the other hand, there is the surreal effect this proclamation has on his family, especially his son. In a scene midway through the film where Daya thinks he is dying at last, he expresses remorse to Rajiv for having poured cold water on his childhood dreams: “You used to write such innocent poetry, but I never let you bloom. I have been such a bad father.” Behl’s work here accommodates both the tenderness of this “deathbed” moment as well as the sheepishness of the morning after when Daya – still very much alive and feeling better – replies with a nod of his head and a “Fit” when his son asks how he is. The heavy-lidded eyes with just the hint of a twinkle in them, the shuffling walk, the quiet gesture, the knowing humour, the gaze that manages to be piercing and laidback at once. These are essential facets of this performance as a man who is supposedly freeing himself of worldly matters but still complains about the tastelessness of the food given to him – a man who finds companionship and banter, things to live for in the city of salvation. As a parent, Daya is a pest but also a teacher and a spiritual guide, showing his son the slower, more contemplative side of life – and eventually encouraging Rajiv to be a better parent to his own young daughter. In this sense, Behl’s performance feels like a complement to his Titli role where the father’s lack of empathy or sensitivity seems to have permanently infected his family.

The heavy-lidded eyes with just the hint of a twinkle in them, the shuffling walk, the quiet gesture, the knowing humour, the gaze that manages to be piercing and laidback at once. These are essential facets of this performance as a man who is supposedly freeing himself of worldly matters but still complains about the tastelessness of the food given to him – a man who finds companionship and banter, things to live for in the city of salvation. As a parent, Daya is a pest but also a teacher and a spiritual guide, showing his son the slower, more contemplative side of life – and eventually encouraging Rajiv to be a better parent to his own young daughter. In this sense, Behl’s performance feels like a complement to his Titli role where the father’s lack of empathy or sensitivity seems to have permanently infected his family.

“Mrityu ek prakriya hai,” Daya is told at one point. “Death is a process – are you ready to begin that process?” It feels painful to re-watch Mukti Bhawan just now, when the gruesome second wave of Covid-19 has – temporarily, one hopes – made nonsense of the idea that dying can be a leisurely, carefully planned-out endeavour. There is such a stark difference between a story about waiting for weeks in a Benares “salvation hotel” and a real-world situation where death comes swiftly and Covid protocols must be coldly followed with no elaborate or personal farewells – the world that Lalit Behl himself departed from. Looked at in this new context, both the plaintiveness and the dark comedy of Mukti Bhawan become sharper, more pronounced and immediate. And Behl’s performance – as a man who is wise and stubborn, parental and childlike, composed and annoying, all at the same time – anchors the film, giving it humanity and allowing us to buy into its biggest conceit: that death can be dignified even when the road leading to it is full of missteps and potholes. It is a useful thought in the current time.

April 30, 2021

Satyajit Ray's 100th - a discussion

My online film club will be chatting about Satyajit Ray on the evening of May 2, his birth centenary. Starting 8 pm IST. Anyone who’d like to join (it will be very informal and free-flowing, no pressure to participate in the discussion), mail me at jaiarjun@gmail.com - or leave your mail ID in the comments here. And pass on the word to others who might be interested.

My online film club will be chatting about Satyajit Ray on the evening of May 2, his birth centenary. Starting 8 pm IST. Anyone who’d like to join (it will be very informal and free-flowing, no pressure to participate in the discussion), mail me at jaiarjun@gmail.com - or leave your mail ID in the comments here. And pass on the word to others who might be interested.

April 20, 2021

On villainy - in Trial of the Chicago 7 and Masters of the Universe

(Things being the way they currently are, there is much reason to want to escape into the distant past. So here's a piece about why Trial of the Chicago 7 – a political film about a real-life 1969 trial – led me into some He-Man nostalgia. Did this for First Post)

---------------

Among the pleasures of watching Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7, with its marvelous ensemble cast and careful structuring of a complex, multi-character story, one pleasure I wasn’t anticipating was a nostalgic one. It was induced by the performance of the 82-year-old Frank Langella, who I hadn’t initially realised was in the film. The character Langella plays is the real-life judge Julius Hoffman, who presided over the 1969 trial of anti-Vietnam War protestors charged with inciting a riot in Chicago. Hoffman often let his own political conservatism show over the course of the proceedings – scuttling the defence’s efforts whenever possible, going easy on the prosecution, barely disguising his disapproval of the defendants – and he sits comfortably in the role of antagonist in this film. (That’s assuming the viewer to be someone who doesn’t think protesting government policies automatically makes one unpatriotic; or, as we like to say in India, “anti-national”.)

The character Langella plays is the real-life judge Julius Hoffman, who presided over the 1969 trial of anti-Vietnam War protestors charged with inciting a riot in Chicago. Hoffman often let his own political conservatism show over the course of the proceedings – scuttling the defence’s efforts whenever possible, going easy on the prosecution, barely disguising his disapproval of the defendants – and he sits comfortably in the role of antagonist in this film. (That’s assuming the viewer to be someone who doesn’t think protesting government policies automatically makes one unpatriotic; or, as we like to say in India, “anti-national”.)

The first major exchange involving Hoffman is played as wry comedy: apparently very concerned that the jury might confuse him with a defendant who shares the same last name – the Youth International Party founder Abbie Hoffman – the old judge repeatedly interrupts an opening speech to clarify that they are not related. This gives the cheeky Abbie (played by Sacha Baron Cohen, an Oscar nominee for best supporting actor this year) an opening to retort with a deadpan “Dad! No!”

It’s a fun little scene, sharply played by Langella and Baron Cohen, but in a way it is also a set-up for the viewer. Lulled into complacency by this banter, you might think “Ah. Grouchy old man, probably a bit of a pest, but basically harmless.” If so, the carpet will soon be pulled out from under your feet. Because as the film continues, the judge’s biases, combined with his stature, build towards darker moments – culminating in a depiction of the infamous real-life incident when Judge Hoffman ordered Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale to be gagged and shackled in the courtroom.

Here is a denizen of the old order, a guardian of status quos, someone capable of using his power to do real harm – and this is of course something that we still see around the world. You don’t have to look much further than some of the extraordinary statements made by judges and chief justices in India in recent times, such as the one where an alleged rapist was politely asked if he was willing to marry his victim (in which case he would be let off lightly). Or the gratuitous persecution of student activists and farmer protestors in courts of law that are meant to be impartial. But to return to my moment of nostalgia: the sight of Frank Langella, shot from low camera angles, framed as a magisterial figure in a black robe, dispensing injustice, struck a chord for a much younger version of me. It reminded me of another antagonist that Langella had played in a very different sort of film that I cherished for a while in my childhood. The film was the 1987 Masters of the Universe, based on the He-Man comics, with the Swedish beefcake Dolph Lundgren as He-Man, a pre-Friends Courtney Cox in a supporting role… and Langella, unrecognisable beneath makeup, as the skull-faced fiend Skeletor.

But to return to my moment of nostalgia: the sight of Frank Langella, shot from low camera angles, framed as a magisterial figure in a black robe, dispensing injustice, struck a chord for a much younger version of me. It reminded me of another antagonist that Langella had played in a very different sort of film that I cherished for a while in my childhood. The film was the 1987 Masters of the Universe, based on the He-Man comics, with the Swedish beefcake Dolph Lundgren as He-Man, a pre-Friends Courtney Cox in a supporting role… and Langella, unrecognisable beneath makeup, as the skull-faced fiend Skeletor.

****

Like many Indian kids in the mid-1980s, I had developed an interest in the Masters of the Universe franchise through the cartoon series that played on TV (with Prince Adam’s roared “By the power of Greyskull…”) as well as the little plastic “He-Man toys” available in the market (I called them action figures, but my mother never missed a chance to point out that they were dolls for boys). Only around six or seven such toys were available in India, but during a two-month vacation in London I discovered dozens of Masters of the Universe characters I’d never even heard of before. On every trip to the Selfridges store, I bought a few of these, along with the accompanying comic books that usually explained a character’s provenance; at the end of our stay, my mother and grandmother had quite a time packing the “dolls” into our suitcases, but eventually we managed to bring them all back home, to the astonishment of my Delhi friends.

Having also heard that a live-action Masters of the Universe film was coming out that summer, I picked up a promotional book that had a plot synopsis, movie stills, and a page featuring information on all the main characters, with blanks where the mug-shots of the characters were supposed to be. You had to fill those blanks by collecting stickers from candy stores – they came with purchases of specific chocolates – and I made multiple trips to Tescos to get as many as possible.

Shortly after returning to India, I acquired a videocassette of the film and watched and re-watched it, showing it to friends. I could tell that it was a less sophisticated cousin to other fantasy franchises like Star Wars or the Christopher Reeve Superman series. But I had a fascination for Langella’s Skeletor – for the commanding walk and the stentorian voice emanating from behind the cheesy makeup. Here was a super-villain to relish, in a similar league as Darth Vader and Mr India’s Mogambo and a few others. In Trial of the Chicago 7, the Bobby Seale scene includes a moment where Langella’s judge comes close to sounding like a larger-than-life villain from a fantasy film. “Marshals, take that defendant into a room and deal with him as he should be dealt with,” he says imperiously; this is followed by shots of Seale being “dealt with” – pushed and punched around some, bound and gagged – before being brought back into the courtroom. Seen in isolation, this plays almost like a depiction of a super-villain’s sadistic henchmen toying with a victim. And it reminds me oddly of the Masters of the Universe scene where Skeletor, incensed by his minions’ failure to capture He-Man, dispatches one of them with a colourful death ray (or something such).

In Trial of the Chicago 7, the Bobby Seale scene includes a moment where Langella’s judge comes close to sounding like a larger-than-life villain from a fantasy film. “Marshals, take that defendant into a room and deal with him as he should be dealt with,” he says imperiously; this is followed by shots of Seale being “dealt with” – pushed and punched around some, bound and gagged – before being brought back into the courtroom. Seen in isolation, this plays almost like a depiction of a super-villain’s sadistic henchmen toying with a victim. And it reminds me oddly of the Masters of the Universe scene where Skeletor, incensed by his minions’ failure to capture He-Man, dispatches one of them with a colourful death ray (or something such).

Scary as Langella’s Skeletor once was for me, it should be obvious why, as a politically aware adult, I find his Hoffman portrayal a little scarier. But if you’re a nerdy enough movie buff, the world of realistic films and the world of mythical-fantasy ones keep colliding in surprising ways. An important scene in Trial of the Chicago 7 involves the testimony of a former Attorney General who takes the stand and says things that discomfit Judge Hoffman, the prosecuting attorneys and anyone else who has pegged the Chicago 7 as incendiary riot-mongers. Though this witness’s testimony is not admitted in the trial, it causes a shift in the proceedings. Watching the film, I was amused that this short dramatic part, of the saviour who shows up the bigots, was played by… Michael Keaton! Back in the late 1980s, we kids mainly knew Keaton as Bruce Wayne of Gotham City. For my child-self, this scene – in a serious, grounded and “respectable” film – felt like a momentary melding of superhero universes. Batman 1, Skeletor zero.

---------------------

BONUS: in light of the latest Address to the Nation by an Indian leader last night, here is an early scene from Masters of the Universe: Skeletor singlehandedly vanquishing a Coronavirus and then boasting about it to the people of Eternia through special telecast. No viruses or prime ministers were harmed in the making of this screen-grab.

BONUS: in light of the latest Address to the Nation by an Indian leader last night, here is an early scene from Masters of the Universe: Skeletor singlehandedly vanquishing a Coronavirus and then boasting about it to the people of Eternia through special telecast. No viruses or prime ministers were harmed in the making of this screen-grab.

[My earlier First Post pieces are here]

April 14, 2021

People, places, nostalgia and imagination in Bombay Rose and Ottaal

(My latest Well Begun column for First Post is about two lovely films, Gitanjali Rao’s animated Bombay Rose and Jayaraj’s Ottaal)

-------------------

It starts with abstract dabs of paint, mainly shades of brown. They spread slowly across the screen – a brush-stroke here, another there. At first there is no telling what they will add up to, but soon there are enough of them to form a larger picture: the skyline of a city, or a ramshackle section of a city. More specific images now crowd the frame: a busy road, people walking, vehicles zipping by, movie hoardings. A setting has been established, a narrative begun.

Gitanjali Rao’s animated film Bombay Rose opens with this movement from haziness to clarity; with nebulous blocks used to construct something sharp and defined. A little later, similar blurry boxes of colour will resolve themselves into a small marketplace where we are introduced to two of the film’s protagonists – a flower-seller named Kamala and her school-going sister Tara.  These opening scenes depict one version – or one specific experience – of Bombay, and others will soon follow: this is a set of interlinking stories about people from different backgrounds and religions, facing various demons and various types of loneliness. For each of them, “Bombay” is as much a state of mind as a place – the city is of course a bustling physical entity, but it is also a fluid one, constantly shaped and reshaped in the characters’ imaginations. Kamala fantasises about being a princess in a genteel bygone era (and is brought back to rude reality by a dalaal who wants to send her to Dubai). Her boyfriend Salim is nourished by the escapist dreams of Bombay’s cinema – and its heroes who can make the impossible possible – but also haunted by memories of the Kashmir he was forced to flee when his parents were gunned down. And, in some of the film’s most elegiac passages, when Shirley D’Souza – an old actress who worked in the 1950s – walks through her nook of the city, colour yields to black and white and the landscape she passes transforms into what it once was – what it still is in her mind’s eye.

These opening scenes depict one version – or one specific experience – of Bombay, and others will soon follow: this is a set of interlinking stories about people from different backgrounds and religions, facing various demons and various types of loneliness. For each of them, “Bombay” is as much a state of mind as a place – the city is of course a bustling physical entity, but it is also a fluid one, constantly shaped and reshaped in the characters’ imaginations. Kamala fantasises about being a princess in a genteel bygone era (and is brought back to rude reality by a dalaal who wants to send her to Dubai). Her boyfriend Salim is nourished by the escapist dreams of Bombay’s cinema – and its heroes who can make the impossible possible – but also haunted by memories of the Kashmir he was forced to flee when his parents were gunned down. And, in some of the film’s most elegiac passages, when Shirley D’Souza – an old actress who worked in the 1950s – walks through her nook of the city, colour yields to black and white and the landscape she passes transforms into what it once was – what it still is in her mind’s eye.

This depiction of the past moving alongside the present is one of the most striking things about Bombay Rose. Old songs like “Aaiye Meherbaan” fleetingly grace the soundtrack. A reflection of Shirley in a mirror shows a younger version of her. Ghosts dance in a graveyard. The sleeve of a shirt – draped across a chair as a stand-in for a long-dead lover – appears to move as if in response to a remark (before one realises that a cat had brushed against it). A weary clock-maker – seemingly a relic of a bygone world, no longer “relevant” – comes alive when presented with a task that only someone like him can do; he asks for his tools – “mota chashma! chaabi!” – like a surgeon focused on his work.

While this is a Bombay film, and is about the many possibilities of that city, one can also argue that it isn’t about any one place: it is about people and the things they carry inside them, from memories of the past to projections of an imagined future. Watching it, I was strangely reminded of the 2015 Malayalam film Ottaal, even though there isn’t much surface similarity between these two works or their settings.  Ottaal, intelligently adapted from a Chekhov short story, begins with ethereal images of the Kuttanad backwaters where a child – soon to be sent away from the only home he knows – spends much of his time minding ducks with his grandfather, their boat rowing across a breath-taking network of canals. To a viewer who is more interested in the quick movement of plot than in the establishing of mood, these scenes might feel self-indulgent or pretentious or slow – but as the film progresses, their importance will become clear. These images are essential markers of a childhood that is about to end: they show how much this boy is part of his setting, and what he is going to be separated from. They are also sights that he desperately needs to preserve in his mind – how fitting it is, then, that the film does everything it can to make these images unforgettable.

Ottaal, intelligently adapted from a Chekhov short story, begins with ethereal images of the Kuttanad backwaters where a child – soon to be sent away from the only home he knows – spends much of his time minding ducks with his grandfather, their boat rowing across a breath-taking network of canals. To a viewer who is more interested in the quick movement of plot than in the establishing of mood, these scenes might feel self-indulgent or pretentious or slow – but as the film progresses, their importance will become clear. These images are essential markers of a childhood that is about to end: they show how much this boy is part of his setting, and what he is going to be separated from. They are also sights that he desperately needs to preserve in his mind – how fitting it is, then, that the film does everything it can to make these images unforgettable.

A decade and a half ago, when it seemed likely for a while that I would have to shift out of the south Delhi neighbourhood I had lived in since age ten, a sudden burst of nostalgia crept up on me and I wandered the length of the colony for an afternoon, camera in hand – taking photos of the many little sights and landmarks, however unremarkable and non-photogenic, that I thought I was going to lose. A few moments in Ottaal reminded me of that rush to collect images.  Similarly, watching Shirley D’Souza and Tara on their walks in Bombay Rose, I thought about the ways in which my neighbourhood has changed over the decades, through a gradual accumulation of events: how a leafy park where we used to play cricket as children turned into an overcrowded parking space where residents scowl at each other while manoeuvring their cars; how a large mall complex sprang up in what was once vast barren land occupied only by a dying old tree; how a video-cassette parlour morphed into a DVD store and then disappeared altogether, and a single-screen hall became a shining multiplex. And about how one’s sense of self also changes along with these things, so that you might find yourself – during a walk through the colony – alternating between being a child and an adult with just a small shift in perspective, or with a change in the play of light as you glance at something.

Similarly, watching Shirley D’Souza and Tara on their walks in Bombay Rose, I thought about the ways in which my neighbourhood has changed over the decades, through a gradual accumulation of events: how a leafy park where we used to play cricket as children turned into an overcrowded parking space where residents scowl at each other while manoeuvring their cars; how a large mall complex sprang up in what was once vast barren land occupied only by a dying old tree; how a video-cassette parlour morphed into a DVD store and then disappeared altogether, and a single-screen hall became a shining multiplex. And about how one’s sense of self also changes along with these things, so that you might find yourself – during a walk through the colony – alternating between being a child and an adult with just a small shift in perspective, or with a change in the play of light as you glance at something.

What these two films have in common is how they create a sense of a setting as something inseparable from the inner lives of the protagonists. They are plaintive depictions of how places define us and are defined by us. For both the old actress in Bombay Rose and the little boy in Ottaal, there will be no going back to their secure spaces – except in the world of the imagination.

[Earlier First Post columns are here]

April 13, 2021

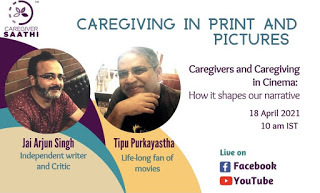

A conversation about caregiving and illness in cinema

Some information about an upcoming event by Caregiver Saathi: on Sunday, April 18, I will be in conversation with my cinephile friend Tipu Purkayastha (whose presence has enlivened so many of my online film-club discussions and courses in the last few months). We will talk about various representations of caregiving and illness in cinema -- from Anand to Amour, from Khamoshi to The Father -- and I will also draw a bit on my grisly experiences in this field in the past few years.

Some information about an upcoming event by Caregiver Saathi: on Sunday, April 18, I will be in conversation with my cinephile friend Tipu Purkayastha (whose presence has enlivened so many of my online film-club discussions and courses in the last few months). We will talk about various representations of caregiving and illness in cinema -- from Anand to Amour, from Khamoshi to The Father -- and I will also draw a bit on my grisly experiences in this field in the past few years. Anyone interested, please show up and spread the word. To register for the session, go here. (You will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the meeting.)

You can watch it on Facebook and Youtube too. (FB link here; YouTube link here.) And mark your calendars here.

Please mail me (jaiarjun@gmail.com) for any clarifications.

April 12, 2021

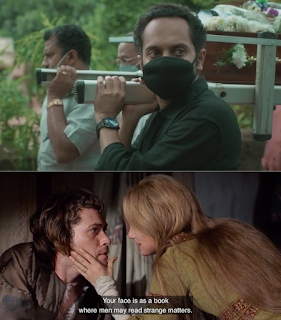

False faces and Covid masks (quick thoughts on the “Macbeth-inspired” Joji)

When I heard Dileesh Pothan’s new film Joji being described as a “Macbeth adaptation”, I mailed the information to my film-club group (with whom I had discussed cinematic treatments of Macbeth just last month). I hadn’t watched Joji at the time, but had heard good things about it, which wasn’t surprising: it stars Fahadh Faasil, who has been one of the most admired Indian actor-producers of the past few years; Pothan himself had helmed two slice-of-life films I enjoyed greatly – Maheshinte Prathikaaram (Mahesh's Revenge) and Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum (The Mainour and the Witness) – in addition to being associated with Kumbalangi Nights, Ee.Ma.Yau., and other films that have helped create the huge recent buzz around Malayalam cinema; and Syam Pushkaran, who co-wrote Pothan's earlier films as well as Kumbalangi Nights, also wrote Joji.  When I did get around to watching Joji, there were little moments that struck me immediately as Macbeth homages, e.g. the witty scene where Joji’s sister-in-law Bincy tells him to “put on a mask and come” (outside his room, to participate in a ceremony for his dead father). With the story playing out in a Covid-19 world, “put on a mask” is a practical instruction — but it is also a nod to the many mask references in the play. (“False face must hide what the false heart doth know.” “…make our faces vizards to our hearts/ Disguising what they are.” And of course: “Your face, my thane, is as a book where men may read strange matters ... look like the innocent flower, But be the serpent under it.”)

When I did get around to watching Joji, there were little moments that struck me immediately as Macbeth homages, e.g. the witty scene where Joji’s sister-in-law Bincy tells him to “put on a mask and come” (outside his room, to participate in a ceremony for his dead father). With the story playing out in a Covid-19 world, “put on a mask” is a practical instruction — but it is also a nod to the many mask references in the play. (“False face must hide what the false heart doth know.” “…make our faces vizards to our hearts/ Disguising what they are.” And of course: “Your face, my thane, is as a book where men may read strange matters ... look like the innocent flower, But be the serpent under it.”)

And then there’s a wry take on Lady Macbeth’s “Out, damn spot”. Bincy at the washing machine in a pivotal scene – and later issuing another instruction about washing clothes.  Fun as it is to play this connect-the-dots game between Pothan’s film and Shakespeare’s play, and much as I enjoyed Joji on its own terms, I ended up puzzled by how many people were rushing to label this a "Macbeth adaptation" – even if Pothan was inspired by the play and wanted to pay tribute to it. This film doesn’t really play like a spiritual descendant of Macbeth, and I wouldn’t have thought of it in those terms if it hadn’t been for all the publicity (including the pre-credits acknowledgement). Too many little points to mention [with the big differences in plot being the least important], but here’s a relevant one made by one of my film-club members Meet Modi: the Joji character isn't internally conflicted — remorseful or guilt-ridden — in the way that Macbeth is [I think of him as being closer in some ways to the pure psycho Faasil played in Kumbalangi Nights]. And once that conflict, and what it leads to, is taken away, how much of the soul of the play remains?

Fun as it is to play this connect-the-dots game between Pothan’s film and Shakespeare’s play, and much as I enjoyed Joji on its own terms, I ended up puzzled by how many people were rushing to label this a "Macbeth adaptation" – even if Pothan was inspired by the play and wanted to pay tribute to it. This film doesn’t really play like a spiritual descendant of Macbeth, and I wouldn’t have thought of it in those terms if it hadn’t been for all the publicity (including the pre-credits acknowledgement). Too many little points to mention [with the big differences in plot being the least important], but here’s a relevant one made by one of my film-club members Meet Modi: the Joji character isn't internally conflicted — remorseful or guilt-ridden — in the way that Macbeth is [I think of him as being closer in some ways to the pure psycho Faasil played in Kumbalangi Nights]. And once that conflict, and what it leads to, is taken away, how much of the soul of the play remains?

(Comparisons have also been made, story-wise, to King Lear; and someone on my Facebook post about the film suggested that Joji is more like Richard III in some ways – presumably because Richard is the Shakespearean character who is closest to the coldly amoral protagonist of this film. But this also implies that the film can quickly turn into a Rorschach inkblot where anyone can see any source text.)

All this, of course, brings us back to the old questions of what an adaptation is, and where the "essence" of Shakespeare lies – questions that have been raised even in discussions of films that follow the plot of a particular play much more closely than Joji does. Most of us can agree that the essence doesn’t lie in the plots, which were heavily borrowed from older sources. So is it in the actual language/poetry used in the plays (in which case a question mark hangs over even the canonised non-English adaptations by Kurosawa or Vishal Bhardwaj or Grigori Kozintsev), or in how character arcs and inner conflicts are brought alive through that poetry? Or in the juxtaposing of different tones, with scatalogical/slaptick comedy sharing a throne with deep tragedy?

Also: do we sometimes err by using "Shakespearean" in the most over-generalised sense to describe just about any story that is about a character grappling with strong negative emotions and moral conflicts? I’m not sure what the point of that would be.

All that said, Joji is a fine film with much to recommend it (though I’m not sure I liked it as much as Maheshinte Prathikaaram) – and if it encourages you to enter the particular world of Dileesh Pothan, or the broader world of Malayalam cinema, all the better. It is on Prime Video.

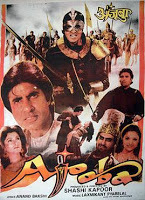

Thirty years ago – awaiting Ajooba

(Part 1 in a series of despatches from the eventful summer of 1991)

I have been working, on and off, on a nostalgia/memory project: some personal writing centred mostly on the late 80s and early 90s, when many intersecting events helped shape my life as a viewer, reader and writer. (Two of those: the birth of an obsession with old Hollywood in the summer of 1991, when I watched films like Psycho for the first time and bought my Leonard Maltin film guide; and the arrival in early 1992 of our first “satellite TV” connection, which opened doors to many new sorts of nourishing experiences, from music videos to daytime soaps. Have written about some of this before, for columns and features – but am trying to do it in a more free-flowing way, and as part of a series.)

Excavating the past has involved rereading my 1990s diaries, a process that can get very morbid if one does it for hours on end (it feels like one is in danger of being lost forever in another time) but also provides some strange epiphanies. When very old diaries are available for reference, you often find big gaps between the narratives you’ve constructed about specific incidents over time and how you actually seemed to experience those incidents when they happened. Here are fragments from a diary entry from 30 years ago today. Friday, April 12, 1991, when Shashi Kapoor’s Ajooba was released:

Here are fragments from a diary entry from 30 years ago today. Friday, April 12, 1991, when Shashi Kapoor’s Ajooba was released:

“I forced myself to survive school because I knew I’d see Ajooba as soon as I came back” […]

“We finally managed to put it on at 3.45. At around 5, nani left the room, muttering to herself what a terrible ‘picture’ it was. I enjoyed it though I’m feeling bad that it will be a super-flop. (We’ll know for sure in about 15 days.) Shashi Kapoor really worked hard on it, and it’s sad that it won’t be appreciated.”

We had been waiting for the film for months, possibly even years, ever since reading in magazines about how this “expensive” “international” fantasy-adventure would be a game-changer for Hindi cinema; more technically polished than anything we had experienced before.

As was always the case in those days, I had bought the audio-cassette when it came out a few weeks before the film’s release – there was nothing too special about the Laxmikant-Pyarelal soundtrack but I spent hours listening to the songs and imagining how they would play out on screen: what would be picturised on whom, the order in which the songs would appear, the specific situations involved. The energetic “Chakdum Chakdum” was my favourite, and for the longest time I was sure it would be sung onscreen by Rishi Kapoor (Mohammed Aziz’s voice seemed a good fit for RK) – later, of course, I watched the film to find that the song was built around Saeed Jaffrey swaying about on a flying carpet with poor back-projection.

In those years I almost never watched films in a movie hall: this was partly out of laziness but also because a family unit made up of my single mother, her widowed mother, and an adolescent me wouldn’t have felt comfortable or safe going to a hall like the nearby Anupam as it was then, decrepit and somewhat shady, years before it became a PVR multiplex. So it was always a video-cassette, rented (usually on Friday evenings) from an uncle who ran a tiny video parlour in his scooter garage just a few feet from our building. As soon as he had got the VHS print (original, pirated, whatever) of whichever film was released that day, he set about making copies so he could rent them widely. On a day when there was something really in demand, like a new Bachchan film, he had a lot of work to do.  In the build-up to April 12, my friend Amit and I had told this uncle that we wanted the film as soon as we returned from school; on the afternoon itself, we must have been so pesky that eventually he invited us up into his own flat to watch some of the film while he was recording a copy for us (and also so we could ensure that nobody else got this copy before we did). Thus it was that before watching Ajooba in its entirety in my own house, I got to see parts of its final half-hour – and felt the first stirrings of disappointment when the giant metallic monster in the climax turned out to be a walking scrap heap with a doleful expression, looking more reluctant than scary when it picked up Shammi Kapoor in its huge claws.

In the build-up to April 12, my friend Amit and I had told this uncle that we wanted the film as soon as we returned from school; on the afternoon itself, we must have been so pesky that eventually he invited us up into his own flat to watch some of the film while he was recording a copy for us (and also so we could ensure that nobody else got this copy before we did). Thus it was that before watching Ajooba in its entirety in my own house, I got to see parts of its final half-hour – and felt the first stirrings of disappointment when the giant metallic monster in the climax turned out to be a walking scrap heap with a doleful expression, looking more reluctant than scary when it picked up Shammi Kapoor in its huge claws.

Though the grand action setpieces that we had been anticipating were a let-down, once expectations had been dialled down I remember liking the overall pace of the film and some of its more regular narrative sections. At the same time, that diary entry about “enjoying it” may have been a defensive reaction to the bad press it was getting from everyone else (even from my mother, the most egalitarian of viewers and a big Shashi Kapoor-Bachchan fan). In any case there was almost no way that the actual film would have matched the version I had had playing in my head for days, having waited so long to see Bachchan in another masked-superhero avatar after his appearances in the Supremo comics.  Today when I think of Ajooba (which I have never watched again in full), three images come to mind: that tragic-looking mechanical giant; a miniaturised Bachchan and Rishi Kapoor cavorting inside the blouses of their girlfriends; Bachchan referring to a dolphin as his mother (and more problematically, calling it a “machli”). These are all moments that have contributed to the current impression that many people have of Ajooba as a film that was always intended to be high camp; whereas those of us who were around then and tracking news about the film knew that it was meant to be an A-list epic on the grandest canvas, the Sholay of its time, or a proto-Bahubali. It didn't quite work out that way, and I remember feeling bad again a few weeks later when I read a self-berating interview of Shashi Kapoor – being more decent and candid than most others would have been in these circumstances – where he said he had "let down" the many people who had worked with him on the film.

Today when I think of Ajooba (which I have never watched again in full), three images come to mind: that tragic-looking mechanical giant; a miniaturised Bachchan and Rishi Kapoor cavorting inside the blouses of their girlfriends; Bachchan referring to a dolphin as his mother (and more problematically, calling it a “machli”). These are all moments that have contributed to the current impression that many people have of Ajooba as a film that was always intended to be high camp; whereas those of us who were around then and tracking news about the film knew that it was meant to be an A-list epic on the grandest canvas, the Sholay of its time, or a proto-Bahubali. It didn't quite work out that way, and I remember feeling bad again a few weeks later when I read a self-berating interview of Shashi Kapoor – being more decent and candid than most others would have been in these circumstances – where he said he had "let down" the many people who had worked with him on the film.

The next few months, starting with May and June 1991, would be some of the most important in my life as a movie nerd – but more on that later in this series. For now, enough to say that the disappointment of Ajooba not being everything one had wanted it to be was a contributing factor to my leaving the world of Hindi cinema (for more than a decade, as it happened) and moving in other directions. So long, dolphin ma, I might have said while I was checking out, and thanks for all the fish.

(To be continued. Also, some trivia that can only be found in old diaries: in the week that I watched Ajooba I also finished George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss, and read my first PG Wodehouse, which was Doctor Sally. And on one of those mornings, in school, a boy was sent out of the classroom for replying "Gandhi-ji" to the question "Who ordered the Jallianwala Bagh firing?")

April 10, 2021

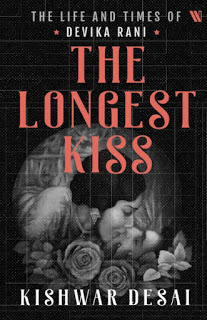

Heroine's journey: a book about Devika Rani

(Did this short review of The Longest Kiss: The Life and Times of Devika Rani, for India Today. Grateful for the book's existence, and for the amount of research done in putting it together, but mixed feelings about the actual writing.)

------------

Anyone who has researched Indian film history knows well the frustration of discovering that much of what they have to work with is hearsay, and that countless important documents are forever gone. Given this, one’s first response to Kishwar Desai's The Longest Kiss – a detailed account of two decades in the life of Devika Rani, pioneering actress and studio head – is to be glad for its existence.  Though Devika lived till 1994, the period covered here is mainly from the late 1920s – when she met and fell in love with the actor-producer Himanshu Rai, with whom she would establish Bombay Talkies – to the mid-1940s, a few years after Rai’s death, when she married the Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich and quit the industry. This period, a pivotal one for Hindi cinema, included her stint as one of the first well-educated Indian women to become a film star; the deterioration of her relationship with Rai; and her later running of the studio in the face of many obstacles. Along the way, Desai offers a counter-narrative to the contemporary ones provided by Saadat Hasan Manto and others, who saw Devika as cold and calculating rather than as someone who had dealt with emotional and physical abuse in her personal relationship (along with the professional pressures of being a woman in charge in a male-dominated world).

Though Devika lived till 1994, the period covered here is mainly from the late 1920s – when she met and fell in love with the actor-producer Himanshu Rai, with whom she would establish Bombay Talkies – to the mid-1940s, a few years after Rai’s death, when she married the Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich and quit the industry. This period, a pivotal one for Hindi cinema, included her stint as one of the first well-educated Indian women to become a film star; the deterioration of her relationship with Rai; and her later running of the studio in the face of many obstacles. Along the way, Desai offers a counter-narrative to the contemporary ones provided by Saadat Hasan Manto and others, who saw Devika as cold and calculating rather than as someone who had dealt with emotional and physical abuse in her personal relationship (along with the professional pressures of being a woman in charge in a male-dominated world).

“I had struck gold,” the author says in her opening note, referring to her discovery of the old papers that had carefully been preserved by Devika. But it couldn’t have been easy to make sense of thousands of documents and shape them into a coherent narrative. Some of that effort comes across in the finished book, which is occasionally swamped by much-too-detailed information about the Bombay Talkies board meetings, resolutions and legal skirmishes, with Desai’s accompanying commentary on the letters and documents.

Perhaps because she realised how dry some of this material inherently is, Desai makes a stylistic decision that might be troubling to some readers of historical writing: she includes novelistic flourishes in her descriptions of meetings and conversations. A businessman speaks with Rai while “slowly twirling the heavy silver paperweight, crafted in Sheffield, on his desk”; when Devika and Himanshu consummate their relationship, her saree, tightly wound at first, “lay unspooled on the floor”. One intriguing example of the book’s constant shifts between imaginative prose and fact-recounting is in a description of Devika reading a letter from Prithviraj Kapoor, introducing his son Raj. This fascinating 1943 document is reproduced on the opposite page, but the author also adds this: “She noticed that his handwriting was very reminiscent of Svetoslav’s. Did all handsome men write the same way, in this strong style with a sharp slant, she wondered idly.”

Of course, Desai’s reasons for doing it this way are understandable – it makes the book a more fluid read, the characters more immediate. And there are places where the conjecture works well: for instance, when Devika suppresses her feelings and supports Rai who has run into legal trouble with an ex-lover, Desai cleverly uses the line “she absorbed the story and got into character” to create the sense of a woman who must follow a script even in real life.

A reader’s response to the extrapolations is a matter of individual taste, but few film buffs will argue with the value of The Longest Kiss as documentation. Or how poignant it is to be drawn back into an era when a silent Indian film like Prem Sanyas/The Light of Asia had a special screening at Windsor Castle – and when a woman in a managerial position helped shape the careers of future legends like Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor.

March 21, 2021

Wagle ki (nayi) Duniya: the 'common man' returns

(Of course, I then got sucked into a time warp and ended up watching a few episodes of Jaspal Bhatti’s Flop Show as well. But that’s for another time.)

------------

“Before the time of mobiles, internet and social media, everything moved at its own sweet pace,” goes the opening voiceover of the acclaimed web series Scam 1992. In its first scene, a man enters a newspaper office with an important scoop. Seeing an elderly gent who looks like a senior editor, he offers to give him the breaking news. “No, no,” says the old man, who turns out to be the legendary cartoonist RK Laxman, determinedly modest even though the whole office is in awe of him, “I am just a common man, you see.” It is a witty beginning to a show about the rise and fall of stockbroker Harshad Mehta, who started off as a “common man” too, but finished his career and life in very uncommon circumstances.

A few years before the Mehta scam unravelled, an RK Laxman-scripted TV show featuring another – much less ambitious – common man was staple viewing on Doordarshan: Wagle ki Duniya was about the sweet little middle-class world of Srinivas Wagle (played by Anjan Srivastava) and his sometimes-exasperated wife Radhika (Bharati Achrekar). Director Kundan Shah, who helmed many of the early episodes, told me once about the experience of working with Laxman on the show. “He was one tough nut – like a snake, always ready to strike with hard-hitting humour, and cantankerous if the right idea for his daily comic didn’t come to him.”

A few years before the Mehta scam unravelled, an RK Laxman-scripted TV show featuring another – much less ambitious – common man was staple viewing on Doordarshan: Wagle ki Duniya was about the sweet little middle-class world of Srinivas Wagle (played by Anjan Srivastava) and his sometimes-exasperated wife Radhika (Bharati Achrekar). Director Kundan Shah, who helmed many of the early episodes, told me once about the experience of working with Laxman on the show. “He was one tough nut – like a snake, always ready to strike with hard-hitting humour, and cantankerous if the right idea for his daily comic didn’t come to him.”It's easy to romanticise the past, to go on about the “golden age” of television in the 1980s, when the whole family watched TV together. (Strictly speaking, with just one channel, there was no choice; if you didn’t like your family you had to sit around waiting for the internet to be invented – or at least for satellite TV to arrive – so everyone could crawl into their separate bubbles.) Revisiting Wagle ki Duniya today, you won’t find much of the sharp-edged comedy that Kundan alluded to (or the caustic satire of his own film Jaane bhi do Yaaro). What you have instead is a quietly absorbing show, gentle but firm in its humour (like the Laxman daily strip), deriving most of its pleasures from the chemistry between the two very likable leads.

It was about everyday things that worried middle-class Indians. The stress that comes with buying a second-hand car or a TV set. Dealing tactfully with a new maid who has her own problems at home. Giving a bribe for the first time, and doing it nonchalantly. Running an office without an assistant. (Wagle works for a company called Ambica Suppliers, and he and his colleague Mr Bhalla help each other out with little chores apart from exchanging advice about daily matters.) Averting a crisis when a date is printed wrong on invitation cards for a residential-society music performance. (Today it would be a matter of seconds to get it corrected on the WhatsApp group.)

In this setting, high drama could reside in the quotidian: thus, rousing superhero music played in a scene where Wagle brought home a large plastic drum for water-storing (packed atop a taxi). When his neighbours learnt that his was the only house getting regular water supply, the soundtrack turned menacing and there were murmurs of “This is corruption.” There was Wagle’s own catchphrase “See the fun!” which could be used in any context, to express annoyance or amusement. And once in a while, there were traces of the zaniness you’d associate with Kundan Shah, as in a scene where a TV salesman recites a list of improbable Japanese brands (“Fujiyama! Kabuki! Haiku 11! Karate 13! Kobe 122!”) to the perplexity of the Wagle family.

We sometimes over-stress the differences between the soft-socialist “then” and the consumerist “now”, but shows like Wagle ki Duniya are reminders that there were fewer things competing for one’s attention back then. How strange it is, with our experience of smart-phone multi-tasking, to see an office-goer feeling harried when the phone on his desk rings as he is heading out to post a letter. Or to hear Wagle worry about his children’s posture when they watch TV. Or to see Mr Bhalla, brows furrowed, tapping away at a small rectangular object in his hand – and to realise, after a few disoriented seconds, that he is holding nothing more lethal than a pocket calculator.

In the scattered moments where Wagle ki Duniya departed from its trademark laidback tone, it was only to reaffirm the “slow and steady” rule. Take the police-station episode in which Shah Rukh Khan, years before movie stardom, plays a youngster who scrapes against Wagle with his car. The YouTube video has comments about SRK’s “over-acting”, but his nervous energy, the swagger and the whines of “Come on, old man!” provide an enjoyable contrast to the show’s overall zeitgeist. Something similar occurs during another episode with Salim Ghouse as a smooth-talking job applicant whose behaviour is seen as rude and inappropriate. The scene builds up to one of Wagle’s funnier lines, delivered by Srivastava in his trademark preoccupied, deadpan style. “Waise woh bura nahin tha,” he tells Radhika (“He wasn’t bad”), and then quickly corrects himself: “Bura tha. But he was qualified.” It is “bura” to be anything more than quietly diligent and self-effacing. But with economic liberalisation just around the corner, one might say these impatient youngsters are trying to drag Wagle into a faster-paced world.

In the scattered moments where Wagle ki Duniya departed from its trademark laidback tone, it was only to reaffirm the “slow and steady” rule. Take the police-station episode in which Shah Rukh Khan, years before movie stardom, plays a youngster who scrapes against Wagle with his car. The YouTube video has comments about SRK’s “over-acting”, but his nervous energy, the swagger and the whines of “Come on, old man!” provide an enjoyable contrast to the show’s overall zeitgeist. Something similar occurs during another episode with Salim Ghouse as a smooth-talking job applicant whose behaviour is seen as rude and inappropriate. The scene builds up to one of Wagle’s funnier lines, delivered by Srivastava in his trademark preoccupied, deadpan style. “Waise woh bura nahin tha,” he tells Radhika (“He wasn’t bad”), and then quickly corrects himself: “Bura tha. But he was qualified.” It is “bura” to be anything more than quietly diligent and self-effacing. But with economic liberalisation just around the corner, one might say these impatient youngsters are trying to drag Wagle into a faster-paced world.****

Which brings us to Wagle ki Duniya: Nayi Peedhi Naye Kisse, in which Srivastava and Achrekar reprise their roles, this time as supporting characters, while the focus shifts to their son Rajesh, his wife Vandana and their children. One might initially be cynical about this sequel-cum-rebooting: its bright saturated colours are worlds removed from the reassuringly dull palettes of 1980s Doordarshan, and the devotional opening scene – with a well-scrubbed family praying and looking gooey-eyed – set off alarm bells for this viewer, suggesting the onset of a standard-issue soap opera that promotes sanskaari “values”.

Which brings us to Wagle ki Duniya: Nayi Peedhi Naye Kisse, in which Srivastava and Achrekar reprise their roles, this time as supporting characters, while the focus shifts to their son Rajesh, his wife Vandana and their children. One might initially be cynical about this sequel-cum-rebooting: its bright saturated colours are worlds removed from the reassuringly dull palettes of 1980s Doordarshan, and the devotional opening scene – with a well-scrubbed family praying and looking gooey-eyed – set off alarm bells for this viewer, suggesting the onset of a standard-issue soap opera that promotes sanskaari “values”.And yet, if you settle in and watch enough episodes (I watched five), you may find that despite the patches of sentimentality – of the sort that one didn’t associate with the first Wagle ki Duniya, Laxman or Kundan Shah – and at least one grating character, a doggerel-spouting society secretary, the new show replicates something of the good-natured charm of the original.

This is partly because the interactions between the next-generation couple (pleasantly played by Sumeet Raghvan and Pariva Pranati) feel natural and lived-in. But also because there are enough reminders that some middle-class problems, challenges and sensibilities don’t go away – notwithstanding the cosmetic changes in Indian society over the past two decades, or the manicured glossiness of the show’s set design. In one episode where Rajesh and family make a very rare outing to a “posh” restaurant and end up with a bill no one anticipated – leading to imagined panic about having to wash plates (“veg and non-veg dishes!”) – both their embarrassment and the small waves of humour around it feel authentic and relatable.

The original Wagle couple, in their first scene, appear on a video call, which immediately sets up a contrast from the old days. But it is also made clear that there isn’t such a big difference between ancient voice recordings on a dusty audio cassette and a family video being recorded on a modern phone; the technology has changed, the texture of the nostalgia is the same. When Rajesh speaks about the sacrifices his parents made for him, it harks back directly to scenes from the 1980s show, such as Wagle going out of his way to entertain his kids with a picnic outing.

“Dadar ki aapki saari purani cheezon ko use kar ke yeh naya mahaul banaaya hai humne (We have used all the things from your old flat to create a new environment),” Rajesh tells his parents after moving them to his building – for instance, he has turned their ancient box TV into a retro-table for the new flat-screen TV. It’s a goofy but oddly moving scene about taking the old and the outdated and situating it in a new context. This is also what the new Wagle ki Duniya is trying to do with our memories of the older show, and with Srivastava and Achrekar around, it may well work. So what if Senior Wagle has turned into a version of the uncle who fumblingly sends motivational messages on WhatsApp at 5 AM? The essence of the man remains, and in his hesitant efforts to make sense of a new duniya you can still “see the fun”.

-------------------------------

P.S. Watching a couple of episodes for this piece, I wondered about the actor playing Wagle’s colleague Mr Bhalla. There was something about his voice and gestures that seemed familiar, but I couldn’t place him until I looked him up: his name is Harish Magon, and a decade before Wagle ki Duniya he appeared in small but very memorable roles in two of Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s best-loved films. In one of Chupke Chupke’s funniest scenes, he is the thief who disturbs Dharmendra and Sharmila Tagore; and in Gol Maal, he is the cocky job applicant who unwisely tries to impress Utpal Dutt by giving his uncle’s reference and talking about his fondness for sports (Black Pearl!).

P.S. Watching a couple of episodes for this piece, I wondered about the actor playing Wagle’s colleague Mr Bhalla. There was something about his voice and gestures that seemed familiar, but I couldn’t place him until I looked him up: his name is Harish Magon, and a decade before Wagle ki Duniya he appeared in small but very memorable roles in two of Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s best-loved films. In one of Chupke Chupke’s funniest scenes, he is the thief who disturbs Dharmendra and Sharmila Tagore; and in Gol Maal, he is the cocky job applicant who unwisely tries to impress Utpal Dutt by giving his uncle’s reference and talking about his fondness for sports (Black Pearl!).

One Wagle ki Duniya episode, in which Wagle and Bhalla try to hire an office assistant, has Harish Magon in a nice inversion of his Gol Maal role – as an interviewer who isn’t impressed by the posturing of an over-smart youngster. Wonder if it might partly have been an inside joke (though I can’t picture RK Laxman referencing Gol Maal in a Wagle script).

One Wagle ki Duniya episode, in which Wagle and Bhalla try to hire an office assistant, has Harish Magon in a nice inversion of his Gol Maal role – as an interviewer who isn’t impressed by the posturing of an over-smart youngster. Wonder if it might partly have been an inside joke (though I can’t picture RK Laxman referencing Gol Maal in a Wagle script).

Jai Arjun Singh's Blog

- Jai Arjun Singh's profile

- 11 followers