Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 24

June 10, 2020

Chekhov in the Kerala backwaters: Ottaal

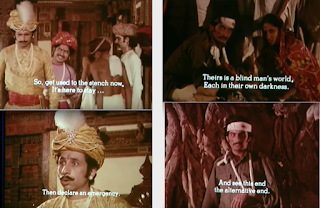

See below for a few images from Ottaal (2015), one of the most haunting films I have watched in a while. (It is playing on Mubi India now. Give it a try.) Directed by Jayaraj, this is an adaptation of the Chekhov short story “Vanka”, about a sad little boy writing a letter. You can read the English translation of that story online, but really, in my view the source text is incidental. Because this film’s beating heart is the very particular terrain in which it unfolds: the Kuttanad backwaters where the child spends much of his time minding ducks with his grandfather.

The many beautiful images – of the place, the people in it, a boat rowing across a breath-taking network of canals, a friendly “nameless dog” running alongside the shore – are markers of a childhood that is about to come to an end. They help you see how much this boy is part of his setting, and what he is going to be separated from; they are pictures he desperately needs to preserve in his mind, and fittingly the film does everything it can to make these images unforgettable.

(The setting also reminded me of S Hareesh’s sprawling novel Moustache, which I reviewed earlier this year. Ottaal is a much sparer work, though, and might be my favourite of the many splendid Malayalam films I have watched in the past year – certainly up there with Ee. Ma. Yau and Kumbalangi Nights. Here is an earlier piece about current Malayalam cinema.)

The many beautiful images – of the place, the people in it, a boat rowing across a breath-taking network of canals, a friendly “nameless dog” running alongside the shore – are markers of a childhood that is about to come to an end. They help you see how much this boy is part of his setting, and what he is going to be separated from; they are pictures he desperately needs to preserve in his mind, and fittingly the film does everything it can to make these images unforgettable.

(The setting also reminded me of S Hareesh’s sprawling novel Moustache, which I reviewed earlier this year. Ottaal is a much sparer work, though, and might be my favourite of the many splendid Malayalam films I have watched in the past year – certainly up there with Ee. Ma. Yau and Kumbalangi Nights. Here is an earlier piece about current Malayalam cinema.)

Published on June 10, 2020 08:40

Short review – Sridevi: The Eternal Screen Goddess

[Wrote this short piece about Satyarth Nayak’s Sridevi book for India Today; it was done many months ago, but since their feature pages were constantly being shortened or dropped in favour of Covid-related coverage, the piece only appeared in print last week]

-----------------------

There is good reason to approach an authorised biography with wariness, especially when the subject is a beloved movie star and the book is published not long after her untimely, much-lamented death. Such were my initial feelings about Sridevi: The Eternal Screen Goddess, which was written with the cooperation of the actress’s husband Boney Kapoor, described by the author as “the invisible force behind this book”.

There is good reason to approach an authorised biography with wariness, especially when the subject is a beloved movie star and the book is published not long after her untimely, much-lamented death. Such were my initial feelings about Sridevi: The Eternal Screen Goddess, which was written with the cooperation of the actress’s husband Boney Kapoor, described by the author as “the invisible force behind this book”.

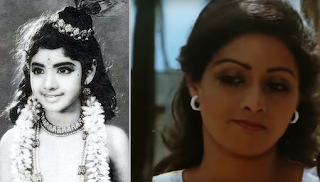

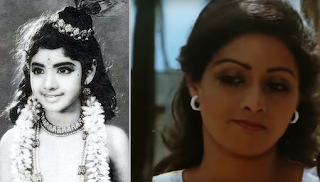

But what makes this book feel personal (and discourages the notion that it was a hurried ego project) is that Nayak makes his own Sridevi obsession immediate and persuasive. While much of the journalistic information here comes from magazines, or first-hand interviews, there is also enough evidence that the author has closely watched and engaged with her large filmography. For those of us who know Sridevi mainly through her work in Hindi cinema, some of the most interesting sections are the ones about her work in Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam cinema, starting with her child roles playing mythological characters like Lord Murugan.

Growing up in the mid-1980s, I must have been among a tiny minority of Hindi-film-loving boys who wasn’t utterly besotted by Sridevi – even though she was central to some of my favourite films such as Mr India and Chandni (and a little less central to other favourites such as Karma, Aakhree Raasta and Watan ke Rakhwale). One reason for this may have been that Sridevi was that rarity among beautiful actresses, someone who was willing to look silly, even buffoonish, on screen, and could pull off slapstick comedy very well – these qualities can be discomfiting if, at a certain age, you want your screen crushes to be aloof and goddess-like (which is something she could also be when required).

Nayak discusses the many Sridevis, including the child-woman who never had a proper transition from childhood to adulthood. (“It was almost as if she was playing out a double role in real life as well – a kid who had grown too much, an adult who had grown too little.”) He covers her intuitive approach to acting, her extraordinary comedic talent, and her deployment of the many rasas in classical Indian expression. The successful pairings with Kamal Haasan, the epochal performances in films like Mondram Pirai (remade in Hindi as Sadma), the rivalry with Jaya Prada, the rise to a stature where she could play an eye-catching double role in even an Amitabh Bachchan film (Khuda Gawah). The ways in which she maintained a measure of control over the male gaze (even while working in a male-dominated industry where heroines were often treated as eye candy) and how her persona in films like Nagina resonated with closet homosexuals, or with other marginalised people.

Nayak discusses the many Sridevis, including the child-woman who never had a proper transition from childhood to adulthood. (“It was almost as if she was playing out a double role in real life as well – a kid who had grown too much, an adult who had grown too little.”) He covers her intuitive approach to acting, her extraordinary comedic talent, and her deployment of the many rasas in classical Indian expression. The successful pairings with Kamal Haasan, the epochal performances in films like Mondram Pirai (remade in Hindi as Sadma), the rivalry with Jaya Prada, the rise to a stature where she could play an eye-catching double role in even an Amitabh Bachchan film (Khuda Gawah). The ways in which she maintained a measure of control over the male gaze (even while working in a male-dominated industry where heroines were often treated as eye candy) and how her persona in films like Nagina resonated with closet homosexuals, or with other marginalised people.

He often begins his analysis of a Sridevi performance in a scene with the words “Watch how…” This can get repetitive and sometimes ornate (“So harrowing is this act that one wonders if it gutted the very insides of the actress” […] “Her face created its own grammar, her charisma overrode every technical rule, creating a physicality that was simply impossible to replicate”) – and it’s possible to wonder how, discussing dozens of films across decades and languages, he doesn’t find anything seriously negative to say about a performance. (Dissing some of her choices is another matter; that’s easily done with any prolific Indian movie star.) But there is also something direct and pleasing about this nerdy attention to detail, this willingness to focus on the little moments, and that’s what raises this book above the assembly-line biography. Even if this is a hagiography, it feels rooted in an honest love for its subject.

-----------------------

There is good reason to approach an authorised biography with wariness, especially when the subject is a beloved movie star and the book is published not long after her untimely, much-lamented death. Such were my initial feelings about Sridevi: The Eternal Screen Goddess, which was written with the cooperation of the actress’s husband Boney Kapoor, described by the author as “the invisible force behind this book”.

There is good reason to approach an authorised biography with wariness, especially when the subject is a beloved movie star and the book is published not long after her untimely, much-lamented death. Such were my initial feelings about Sridevi: The Eternal Screen Goddess, which was written with the cooperation of the actress’s husband Boney Kapoor, described by the author as “the invisible force behind this book”. But what makes this book feel personal (and discourages the notion that it was a hurried ego project) is that Nayak makes his own Sridevi obsession immediate and persuasive. While much of the journalistic information here comes from magazines, or first-hand interviews, there is also enough evidence that the author has closely watched and engaged with her large filmography. For those of us who know Sridevi mainly through her work in Hindi cinema, some of the most interesting sections are the ones about her work in Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam cinema, starting with her child roles playing mythological characters like Lord Murugan.

Growing up in the mid-1980s, I must have been among a tiny minority of Hindi-film-loving boys who wasn’t utterly besotted by Sridevi – even though she was central to some of my favourite films such as Mr India and Chandni (and a little less central to other favourites such as Karma, Aakhree Raasta and Watan ke Rakhwale). One reason for this may have been that Sridevi was that rarity among beautiful actresses, someone who was willing to look silly, even buffoonish, on screen, and could pull off slapstick comedy very well – these qualities can be discomfiting if, at a certain age, you want your screen crushes to be aloof and goddess-like (which is something she could also be when required).

Nayak discusses the many Sridevis, including the child-woman who never had a proper transition from childhood to adulthood. (“It was almost as if she was playing out a double role in real life as well – a kid who had grown too much, an adult who had grown too little.”) He covers her intuitive approach to acting, her extraordinary comedic talent, and her deployment of the many rasas in classical Indian expression. The successful pairings with Kamal Haasan, the epochal performances in films like Mondram Pirai (remade in Hindi as Sadma), the rivalry with Jaya Prada, the rise to a stature where she could play an eye-catching double role in even an Amitabh Bachchan film (Khuda Gawah). The ways in which she maintained a measure of control over the male gaze (even while working in a male-dominated industry where heroines were often treated as eye candy) and how her persona in films like Nagina resonated with closet homosexuals, or with other marginalised people.

Nayak discusses the many Sridevis, including the child-woman who never had a proper transition from childhood to adulthood. (“It was almost as if she was playing out a double role in real life as well – a kid who had grown too much, an adult who had grown too little.”) He covers her intuitive approach to acting, her extraordinary comedic talent, and her deployment of the many rasas in classical Indian expression. The successful pairings with Kamal Haasan, the epochal performances in films like Mondram Pirai (remade in Hindi as Sadma), the rivalry with Jaya Prada, the rise to a stature where she could play an eye-catching double role in even an Amitabh Bachchan film (Khuda Gawah). The ways in which she maintained a measure of control over the male gaze (even while working in a male-dominated industry where heroines were often treated as eye candy) and how her persona in films like Nagina resonated with closet homosexuals, or with other marginalised people.He often begins his analysis of a Sridevi performance in a scene with the words “Watch how…” This can get repetitive and sometimes ornate (“So harrowing is this act that one wonders if it gutted the very insides of the actress” […] “Her face created its own grammar, her charisma overrode every technical rule, creating a physicality that was simply impossible to replicate”) – and it’s possible to wonder how, discussing dozens of films across decades and languages, he doesn’t find anything seriously negative to say about a performance. (Dissing some of her choices is another matter; that’s easily done with any prolific Indian movie star.) But there is also something direct and pleasing about this nerdy attention to detail, this willingness to focus on the little moments, and that’s what raises this book above the assembly-line biography. Even if this is a hagiography, it feels rooted in an honest love for its subject.

Published on June 10, 2020 00:15

June 8, 2020

Animal chronicles contd: rescuing Coffee

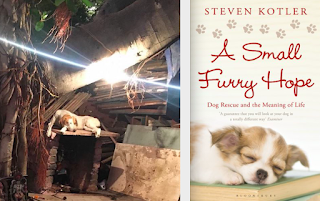

This is a dog named Coffee, and if you think he is not looking in good health here, you do NOT want to see photos of him from two weeks ago (I won’t post any of those because I’d rather not use this space for grisly images, I see enough of those every day on WhatsApp animal groups).

This is a dog named Coffee, and if you think he is not looking in good health here, you do NOT want to see photos of him from two weeks ago (I won’t post any of those because I’d rather not use this space for grisly images, I see enough of those every day on WhatsApp animal groups). It’s hard to describe what bad shape Coffee was in back then, you had to see for yourself: he had large purple boils all over his back, some of which had burst and were fetid and oozing pus; he was unable to see properly, and kept bumping into parked cars and walls each time he tried to stagger about. Vasundhara, his regular feeder in D-block, Saket had been trying to catch or medicate him, with little success, and things were reaching a point of no return — so I asked our paravet heroes Ravi and Manoj to come across and give it a try. What began as a disorganised catching attempt by four or five of us quickly turned into an extended nighttime adventure.

Confronted by a couple of confused-looking humans who were holding out a large sheet between them and idly hoping he would run into it, Coffee found a sudden burst of energy, darted past us and crawled under the (locked) gate of one of the largest parks in the vicinity. It was late, we were tempted to give up for the night (and Manoj had to go to the hospital because his sister-in-law was very unwell), but somehow we extracted the park key from a senior resident, and there followed a chase scene as stirring as anything out of The French Connection or Black Friday. In a huge, dark, jungle-like space where all of us had to keep our phone torches on and get into pairs to cut the terrified dog’s escape routes off. Finally we cornered him, Ravi managed to get a chain around his neck (very difficult to do without causing him harm), and then one of our kindliest residents, Chhavi, drove him to a vet + boarding facility in Chhatarpur. He has been there for the past two weeks, and will probably stay another few days.

The good news: the biopsy report has indicated nothing very threatening so far. The not-so-good news: the skin ruptures will need to be monitored closely after he is back in his lane, and that’s always tricky with a street dog, with rainy weather ahead. Still, at this point it looks like we should be able to call this a success story — if so, it’s a rare one for a dog who was in the condition that Coffee was in two weeks ago. Given how things were then, it’s good just to see him calm, eating biscuits and looking at the camera. This might seem an unattractive photo at first glance, but for me it's a very satisfying one.

[Earlier posts about Ravi and Manoj: 1, 2]

Published on June 08, 2020 19:51

June 1, 2020

'Cinema and Migrant Crises', an online conversation

For this fundraising event, writer-filmmaker Devashish Makhija and I will discuss Cinema and Migrant Crises, as well as related subjects, on June 6. The starting point for the talk will be Devashish’s stunning film Bhonsle — with Manoj Bajpayee as an elderly Bombay cop who gets caught up in a conflict between locals and migrants in his chawl — but we will also talk more generally about Devashish’s work and its concerns (in addition to

For this fundraising event, writer-filmmaker Devashish Makhija and I will discuss Cinema and Migrant Crises, as well as related subjects, on June 6. The starting point for the talk will be Devashish’s stunning film Bhonsle — with Manoj Bajpayee as an elderly Bombay cop who gets caught up in a conflict between locals and migrants in his chawl — but we will also talk more generally about Devashish’s work and its concerns (in addition to

making feature-length and short films, he has authored short stories, tiny tales and children’s books).

making feature-length and short films, he has authored short stories, tiny tales and children’s books).The link for registration is here. Please spread the word to anyone who might be interested.

P.S. here is a piece I wrote about Makhija's short film Taandav, which also featured Manoj Bajpayee as a policeman.

Published on June 01, 2020 20:27

May 31, 2020

Dog day afternoons, a sentimental misanthrope, and two books about animal rescue

[My latest First Post piece touches on two dog books -- though this is only tangentially a books column]

---------------------

On the spookily quiet afternoon of Sunday, March 22 this year – during the “Janta curfew”, two days before the first lockdown was announced – I was walking to the chemist’s shop in my colony. Almost no other humans were visible, apart from a few in their balconies, frowning down at this curfew-violator; it was so still I thought I could hear leaves fall from trees some distance away.

Worried as I already was about the pandemic and what was likely to come (you didn’t need to be an epidemiologist to know that extended lockdowns lay in our future), the full implications didn’t hit me until I passed a well-known vegetable vendor’s tent – always bustling with activity, now closed for the day – and saw the man’s dog sitting all alone, looking lost.

Here was this familiar white creature, his open and affable face seemingly lined with stress. This was the first time he was spending hours on end with not even one of his people around, and with no human sounds within earshot. He must have been very disoriented.

Subsequently, when the lockdown began, my thoughts turned to the many street animals in our neighbourhood who had been adopted or befriended by shopkeepers or roadside retailers or dhaba-wallahs: people who would no longer be around to put out food and water and, just as importantly, to pat and pamper the animals. The dogs in the nearby multiplex complex. The dogs left in parks that had been summarily locked up (this being before animal-welfare teams got into action). The wilder dogs on the periphery of the residential areas, much less accustomed to human kindness, who used to scavenge in the rapidly emptying garbage dumps. I had a few sleepless nights listening to urgent cries in the distance as terrified dogs strayed into other territories and fights broke out (and as my house dogs became watchful and tense in response). It wasn’t until I had got myself on animal-feeder WhatsApp groups, got in touch with other concerned people in the neighbourhood, made a couple of trips with bags of food for stranded animals in the areas I knew well, and got a movement pass through Maneka Gandhi’s organisation, that I felt more at ease. Anything I could do would be a tiny drop in a deep and dark ocean, but at least there was a sense of purpose.

Subsequently, when the lockdown began, my thoughts turned to the many street animals in our neighbourhood who had been adopted or befriended by shopkeepers or roadside retailers or dhaba-wallahs: people who would no longer be around to put out food and water and, just as importantly, to pat and pamper the animals. The dogs in the nearby multiplex complex. The dogs left in parks that had been summarily locked up (this being before animal-welfare teams got into action). The wilder dogs on the periphery of the residential areas, much less accustomed to human kindness, who used to scavenge in the rapidly emptying garbage dumps. I had a few sleepless nights listening to urgent cries in the distance as terrified dogs strayed into other territories and fights broke out (and as my house dogs became watchful and tense in response). It wasn’t until I had got myself on animal-feeder WhatsApp groups, got in touch with other concerned people in the neighbourhood, made a couple of trips with bags of food for stranded animals in the areas I knew well, and got a movement pass through Maneka Gandhi’s organisation, that I felt more at ease. Anything I could do would be a tiny drop in a deep and dark ocean, but at least there was a sense of purpose.

What was more surprising – speaking as someone who has often casually described himself as a misanthrope – was that during this process I also found myself feeling sentimental about my own species, and becoming very annoyed by the online memes that went “Humans are the virus, Covid is the vaccine” or “We are the most destructive species – nature thrives without us”. Partly, this is because I have never had a rose-tinted view of the natural world anyway; I think Tennyson’s “red in tooth and claw” is, if anything, an understated description of the countless random cruelties inherent in nature. But my growing concern about humans was also a result of my relationship with street dogs over the years. Since these are very social animals – who not just depend on people for food but also genuinely like being around us – I had access to this vantage point: how sad and empty a human-free world might look through the eyes of a creature that has evolved socially alongside us over tens of thousands of years, become one of our most steadfast companions, emotionally enriching many of us along the way.

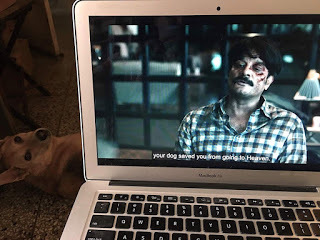

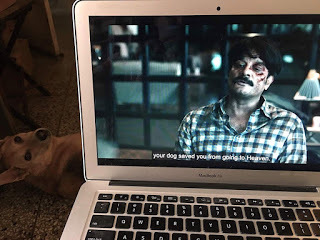

As a lovely, unexpected plot development in the new web series Paatal Lok has it, dogs can be our guiding lights, bringing out the best in us – people can find personal salvation in caring for dogs, it can even help them stay out of harm’s way. One of our most steadfast helpers, Ravi, who has been spending 10 to 12 hours on the road every day feeding and medicating injured animals during the pandemic, believes that this work has helped keep him safe – not so much for mystical reasons but because it gives him a sense of fulfilment and duty, prevents him from falling into despair or homebound ennui, keeps his spirits and immunity levels higher than if he had been cooped indoors for two months. It sounds pseudoscientific, but I hope there is something to it.

As a lovely, unexpected plot development in the new web series Paatal Lok has it, dogs can be our guiding lights, bringing out the best in us – people can find personal salvation in caring for dogs, it can even help them stay out of harm’s way. One of our most steadfast helpers, Ravi, who has been spending 10 to 12 hours on the road every day feeding and medicating injured animals during the pandemic, believes that this work has helped keep him safe – not so much for mystical reasons but because it gives him a sense of fulfilment and duty, prevents him from falling into despair or homebound ennui, keeps his spirits and immunity levels higher than if he had been cooped indoors for two months. It sounds pseudoscientific, but I hope there is something to it.

****

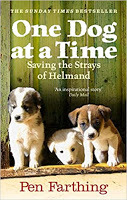

The many experiences of the past two months also had me revisiting a couple of books by and about people who discovered a new dimension in themselves and found their senses sharpened through animal rescue. Pen Farthing's One Dog at a Time: Rescuing the Strays of Helmand is about a British soldier who became involved with dogs while he was posted in Afghanistan, battling the Taliban (and therefore supposed to be concerned with more “important” things than stray animals). And Steven Kotler's A Small Furry Hope: Dog Rescue and the Meaning of Life is about the experiences of the author and his wife Joy as they started a sanctuary in New Mexico for dogs with special needs.

The scale and scope of the two works is different. Kotler's is more wide-ranging, touching on the philosophical and scientific aspects of the human-animal relationship. He does of course tell a specific story, looking at the minutiae of dog care and the many daily challenges: e.g., is it better to go for high-quality but expensive dog food, or to compromise just a little on quality but take the risk that this will lead to medical conditions requiring costly care? However, he expands the canvas too, delving into such questions as the nature of altruism, where our urge to help other species comes from, and why grief caused by pet loss can be so complicated and intense.

The scale and scope of the two works is different. Kotler's is more wide-ranging, touching on the philosophical and scientific aspects of the human-animal relationship. He does of course tell a specific story, looking at the minutiae of dog care and the many daily challenges: e.g., is it better to go for high-quality but expensive dog food, or to compromise just a little on quality but take the risk that this will lead to medical conditions requiring costly care? However, he expands the canvas too, delving into such questions as the nature of altruism, where our urge to help other species comes from, and why grief caused by pet loss can be so complicated and intense.

Farthing’s book, on the other hand, is more functional and soldier-like in the writing, and is determinedly about the here and now. His concern for one dog – being used in a savage dog-fight by the locals – gradually snowballed into something bigger, until he found himself stretching military rules to provide shelter to a group of animals, and eventually making attempts to have them transported to a makeshift animal shelter in north Afghanistan. This situation – finding the time even during a war to do something for helpless creatures – isn’t unlike the situation some animal-lovers find themselves in during the current pandemic, where they are told that they have their priorities mixed up.

The experiences of Kotler and Farthing are different from my own in the specifics, yet many times while rereading these books I found something that struck a chord. “Joy once told me of an exhilaration unlike any other she’s ever known that comes from seeing a dog reborn,” writes Kotler, “In the psychology of altruism, that rush is known as helper’s high.”

Meanwhile, Farthing writes: “I couldn’t just walk away. My problem now was that the dog with no friends and I were becoming mates […] As I gave him what was probably the first bit of compassion he had ever been shown, I wondered whether I had done the right thing for him and the other dogs. I’d given them a totally unfounded trust in humans. When I was gone that might not be the best thing for them.” This is something that many people who expanded their animal-feeding operations specifically for the lockdown period are thinking about: how long is this sustainable, and what happens to these animals when things return to relative “normalcy”? What about all the irresponsible speeding drivers, endangering the animals who had begun drifting towards the middle of the roads when human movement ceased?

In the end, both these books are about people transformed. They are versions of the parable about a boy throwing starfish back into the sea, one by one; each rescue might seem insignificant in the larger picture, but makes a world of difference to that one creature. Much in these pages should be very familiar to anyone who works with stray animals, constantly balancing the need to make a meaningful difference with the knowledge that there will always be many failures and hopeless cases. And the possibility that everything might go south at any time, leading to a potent sense of loss. Yet we keep at it, doing what we can – there is no real choice.

[Earlier First Post columns are here]

---------------------

On the spookily quiet afternoon of Sunday, March 22 this year – during the “Janta curfew”, two days before the first lockdown was announced – I was walking to the chemist’s shop in my colony. Almost no other humans were visible, apart from a few in their balconies, frowning down at this curfew-violator; it was so still I thought I could hear leaves fall from trees some distance away.

Worried as I already was about the pandemic and what was likely to come (you didn’t need to be an epidemiologist to know that extended lockdowns lay in our future), the full implications didn’t hit me until I passed a well-known vegetable vendor’s tent – always bustling with activity, now closed for the day – and saw the man’s dog sitting all alone, looking lost.

Here was this familiar white creature, his open and affable face seemingly lined with stress. This was the first time he was spending hours on end with not even one of his people around, and with no human sounds within earshot. He must have been very disoriented.

Subsequently, when the lockdown began, my thoughts turned to the many street animals in our neighbourhood who had been adopted or befriended by shopkeepers or roadside retailers or dhaba-wallahs: people who would no longer be around to put out food and water and, just as importantly, to pat and pamper the animals. The dogs in the nearby multiplex complex. The dogs left in parks that had been summarily locked up (this being before animal-welfare teams got into action). The wilder dogs on the periphery of the residential areas, much less accustomed to human kindness, who used to scavenge in the rapidly emptying garbage dumps. I had a few sleepless nights listening to urgent cries in the distance as terrified dogs strayed into other territories and fights broke out (and as my house dogs became watchful and tense in response). It wasn’t until I had got myself on animal-feeder WhatsApp groups, got in touch with other concerned people in the neighbourhood, made a couple of trips with bags of food for stranded animals in the areas I knew well, and got a movement pass through Maneka Gandhi’s organisation, that I felt more at ease. Anything I could do would be a tiny drop in a deep and dark ocean, but at least there was a sense of purpose.

Subsequently, when the lockdown began, my thoughts turned to the many street animals in our neighbourhood who had been adopted or befriended by shopkeepers or roadside retailers or dhaba-wallahs: people who would no longer be around to put out food and water and, just as importantly, to pat and pamper the animals. The dogs in the nearby multiplex complex. The dogs left in parks that had been summarily locked up (this being before animal-welfare teams got into action). The wilder dogs on the periphery of the residential areas, much less accustomed to human kindness, who used to scavenge in the rapidly emptying garbage dumps. I had a few sleepless nights listening to urgent cries in the distance as terrified dogs strayed into other territories and fights broke out (and as my house dogs became watchful and tense in response). It wasn’t until I had got myself on animal-feeder WhatsApp groups, got in touch with other concerned people in the neighbourhood, made a couple of trips with bags of food for stranded animals in the areas I knew well, and got a movement pass through Maneka Gandhi’s organisation, that I felt more at ease. Anything I could do would be a tiny drop in a deep and dark ocean, but at least there was a sense of purpose.What was more surprising – speaking as someone who has often casually described himself as a misanthrope – was that during this process I also found myself feeling sentimental about my own species, and becoming very annoyed by the online memes that went “Humans are the virus, Covid is the vaccine” or “We are the most destructive species – nature thrives without us”. Partly, this is because I have never had a rose-tinted view of the natural world anyway; I think Tennyson’s “red in tooth and claw” is, if anything, an understated description of the countless random cruelties inherent in nature. But my growing concern about humans was also a result of my relationship with street dogs over the years. Since these are very social animals – who not just depend on people for food but also genuinely like being around us – I had access to this vantage point: how sad and empty a human-free world might look through the eyes of a creature that has evolved socially alongside us over tens of thousands of years, become one of our most steadfast companions, emotionally enriching many of us along the way.

As a lovely, unexpected plot development in the new web series Paatal Lok has it, dogs can be our guiding lights, bringing out the best in us – people can find personal salvation in caring for dogs, it can even help them stay out of harm’s way. One of our most steadfast helpers, Ravi, who has been spending 10 to 12 hours on the road every day feeding and medicating injured animals during the pandemic, believes that this work has helped keep him safe – not so much for mystical reasons but because it gives him a sense of fulfilment and duty, prevents him from falling into despair or homebound ennui, keeps his spirits and immunity levels higher than if he had been cooped indoors for two months. It sounds pseudoscientific, but I hope there is something to it.

As a lovely, unexpected plot development in the new web series Paatal Lok has it, dogs can be our guiding lights, bringing out the best in us – people can find personal salvation in caring for dogs, it can even help them stay out of harm’s way. One of our most steadfast helpers, Ravi, who has been spending 10 to 12 hours on the road every day feeding and medicating injured animals during the pandemic, believes that this work has helped keep him safe – not so much for mystical reasons but because it gives him a sense of fulfilment and duty, prevents him from falling into despair or homebound ennui, keeps his spirits and immunity levels higher than if he had been cooped indoors for two months. It sounds pseudoscientific, but I hope there is something to it.****

The many experiences of the past two months also had me revisiting a couple of books by and about people who discovered a new dimension in themselves and found their senses sharpened through animal rescue. Pen Farthing's One Dog at a Time: Rescuing the Strays of Helmand is about a British soldier who became involved with dogs while he was posted in Afghanistan, battling the Taliban (and therefore supposed to be concerned with more “important” things than stray animals). And Steven Kotler's A Small Furry Hope: Dog Rescue and the Meaning of Life is about the experiences of the author and his wife Joy as they started a sanctuary in New Mexico for dogs with special needs.

The scale and scope of the two works is different. Kotler's is more wide-ranging, touching on the philosophical and scientific aspects of the human-animal relationship. He does of course tell a specific story, looking at the minutiae of dog care and the many daily challenges: e.g., is it better to go for high-quality but expensive dog food, or to compromise just a little on quality but take the risk that this will lead to medical conditions requiring costly care? However, he expands the canvas too, delving into such questions as the nature of altruism, where our urge to help other species comes from, and why grief caused by pet loss can be so complicated and intense.

The scale and scope of the two works is different. Kotler's is more wide-ranging, touching on the philosophical and scientific aspects of the human-animal relationship. He does of course tell a specific story, looking at the minutiae of dog care and the many daily challenges: e.g., is it better to go for high-quality but expensive dog food, or to compromise just a little on quality but take the risk that this will lead to medical conditions requiring costly care? However, he expands the canvas too, delving into such questions as the nature of altruism, where our urge to help other species comes from, and why grief caused by pet loss can be so complicated and intense.Farthing’s book, on the other hand, is more functional and soldier-like in the writing, and is determinedly about the here and now. His concern for one dog – being used in a savage dog-fight by the locals – gradually snowballed into something bigger, until he found himself stretching military rules to provide shelter to a group of animals, and eventually making attempts to have them transported to a makeshift animal shelter in north Afghanistan. This situation – finding the time even during a war to do something for helpless creatures – isn’t unlike the situation some animal-lovers find themselves in during the current pandemic, where they are told that they have their priorities mixed up.

The experiences of Kotler and Farthing are different from my own in the specifics, yet many times while rereading these books I found something that struck a chord. “Joy once told me of an exhilaration unlike any other she’s ever known that comes from seeing a dog reborn,” writes Kotler, “In the psychology of altruism, that rush is known as helper’s high.”

Meanwhile, Farthing writes: “I couldn’t just walk away. My problem now was that the dog with no friends and I were becoming mates […] As I gave him what was probably the first bit of compassion he had ever been shown, I wondered whether I had done the right thing for him and the other dogs. I’d given them a totally unfounded trust in humans. When I was gone that might not be the best thing for them.” This is something that many people who expanded their animal-feeding operations specifically for the lockdown period are thinking about: how long is this sustainable, and what happens to these animals when things return to relative “normalcy”? What about all the irresponsible speeding drivers, endangering the animals who had begun drifting towards the middle of the roads when human movement ceased?

In the end, both these books are about people transformed. They are versions of the parable about a boy throwing starfish back into the sea, one by one; each rescue might seem insignificant in the larger picture, but makes a world of difference to that one creature. Much in these pages should be very familiar to anyone who works with stray animals, constantly balancing the need to make a meaningful difference with the knowledge that there will always be many failures and hopeless cases. And the possibility that everything might go south at any time, leading to a potent sense of loss. Yet we keep at it, doing what we can – there is no real choice.

[Earlier First Post columns are here]

Published on May 31, 2020 09:49

May 30, 2020

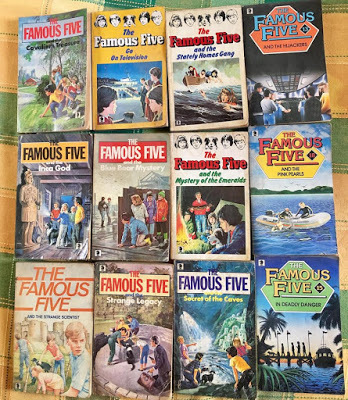

Bookshelves past: The Famous Five, not by Enid Blyton

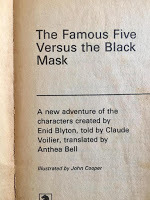

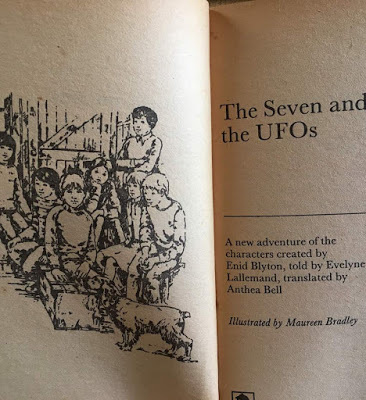

From the Land of Long Ago. This series of Famous Five adventures was written in the 1970s, a few years after Enid Blyton’s death, by the French author Claude Voilier. I remember devouring a bunch of them at a go and realising that they were very different in tone from the original Blyton books — less cosy and provincial, more cosmopolitan and action-packed — though it was nice to encounter the familiar characters again. My favourite in the series was Five Versus the Black Mask, which I read out to my mother and was disappointed when she wasn’t astonished by the identity of the masked criminal. (These days, of course, anyone who wanders around mask-less is instantly identifiable as the bad guy.)

From the Land of Long Ago. This series of Famous Five adventures was written in the 1970s, a few years after Enid Blyton’s death, by the French author Claude Voilier. I remember devouring a bunch of them at a go and realising that they were very different in tone from the original Blyton books — less cosy and provincial, more cosmopolitan and action-packed — though it was nice to encounter the familiar characters again. My favourite in the series was Five Versus the Black Mask, which I read out to my mother and was disappointed when she wasn’t astonished by the identity of the masked criminal. (These days, of course, anyone who wanders around mask-less is instantly identifiable as the bad guy.) Anyway, my big revelation on pulling these books out after decades: the English translations were by Anthea Bell. Anthea Bell! The legend who, in addition to her celebrated work on Asterix (which I never read as a child), also translated many "serious", grown-up books I read later in life, like Sebald’s Austerlitz and Szpilman’s The Pianist. Quite pleased, with hindsight, that I experienced her work so early without even knowing it at the time.

Anyway, my big revelation on pulling these books out after decades: the English translations were by Anthea Bell. Anthea Bell! The legend who, in addition to her celebrated work on Asterix (which I never read as a child), also translated many "serious", grown-up books I read later in life, like Sebald’s Austerlitz and Szpilman’s The Pianist. Quite pleased, with hindsight, that I experienced her work so early without even knowing it at the time. P.S. These were bought at between Rs 17 and Rs 19 — from Teksons, South Extension, I think; this would have been in around 1983-84. Anthea Bell also translated another Blyton spin-off, a series of new adventures for The Secret Seven. I have a few of those too, though I don’t remember reading them.

Published on May 30, 2020 03:44

May 29, 2020

Lockdown chronicles contd: Pratima Devi

An update about Pratima Devi a.k.a. the “kutton waali Amma” of PVR Saket: I went to see her this morning and was glad that she was looking relatively well. A few extra tarpaulins are in use to keep the worst of the Delhi sun away. Some of the dogs have mange and other related skin problems, and aren’t getting as much medical attention as they need these days, but nothing terribly urgent. For now.

An update about Pratima Devi a.k.a. the “kutton waali Amma” of PVR Saket: I went to see her this morning and was glad that she was looking relatively well. A few extra tarpaulins are in use to keep the worst of the Delhi sun away. Some of the dogs have mange and other related skin problems, and aren’t getting as much medical attention as they need these days, but nothing terribly urgent. For now.  I had posted a few weeks ago about a white Spitz/Pomeranian who had been abandoned near Pratima Devi’s shack (Facebook link here). This dog had seemed very unsettled and scared then – didn’t look like he would survive for long in this environment – but in typical style she has made him one of her own, and he is very attached to her now. (Don’t miss the other fellow sunbathing on the chair in the background in the photo.)

I had posted a few weeks ago about a white Spitz/Pomeranian who had been abandoned near Pratima Devi’s shack (Facebook link here). This dog had seemed very unsettled and scared then – didn’t look like he would survive for long in this environment – but in typical style she has made him one of her own, and he is very attached to her now. (Don’t miss the other fellow sunbathing on the chair in the background in the photo.)That might sound like a sweet story, but just to reiterate something I have said many times before: it is ghastly how many people use this old woman as a dumping ground for dogs; she makes sure to sterilise every dog precisely because she wants to keep the population under control, and at her age it is too much of a

responsibility to start looking after new litters of pups. It was particularly sad to see a St Bernard – of all dogs – who had recently been abandoned. In this heat. (Naturally, he has been given a haircut. A picture of him here with Pawan, who is helping Pratima Devi with the feeding and medicating.)

responsibility to start looking after new litters of pups. It was particularly sad to see a St Bernard – of all dogs – who had recently been abandoned. In this heat. (Naturally, he has been given a haircut. A picture of him here with Pawan, who is helping Pratima Devi with the feeding and medicating.)P.S. Pratima Devi’s son Sapan is going back to his village in Bengal next month – it has been chaotic there after the cyclone, but there’s also another problem, one that I have heard expressed many times in recent conversations: the fear that many villagers have of those who are returning from cities, potentially carrying this terrible new disease that can’t be meaningfully treated in rural areas if it spreads there. Reena, who manages my mother’s flat and has family near Nischintapur in Bengal, tells me she has been on the phone nonstop with worried relatives who are asking her (because she is the city-dwelling oracle who MUST have the answers) what is to be done about all these migrants who are returning home from metropolises as far-flung as Chennai and Bangalore. Do they “isolate” them, for how long… and where? P.P.S. here is a very short video of Pawan -- not in very good health himself at the time -- rescuing a dog from a deep drain. This was a few weeks ago.

Published on May 29, 2020 08:37

May 24, 2020

An online class about Aakrosh and Bhavni Bhavai

There’s a thing called "Zoom", on which you can see many small talking human faces if you’re thus inclined, including your own. Thanks to Basav Biradar, who invited me to participate in one of his Indian New Wave cinema classes, I used this for the first time a couple of days ago. It was a fun session that covered a range of subjects and reminded me how much I miss teaching film criticism/analysis (or really, just discussing films with a group of engaged students).

There’s a thing called "Zoom", on which you can see many small talking human faces if you’re thus inclined, including your own. Thanks to Basav Biradar, who invited me to participate in one of his Indian New Wave cinema classes, I used this for the first time a couple of days ago. It was a fun session that covered a range of subjects and reminded me how much I miss teaching film criticism/analysis (or really, just discussing films with a group of engaged students). Basav and I figured it might be interesting to discuss two 1980 films — both debut features by important directors — that dealt with caste oppression in very different ways: Ketan Mehta’s Bhavni Bhavai and Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh. This gave me a chance to rewatch the two films

close to each other, making it easier to appreciate the similarities as well as the differences (and the similarities within the differences). Was struck again by Nihalani’s use of Om Puri (something I wrote about earlier in the context of Ardh Satya, Aghaat and Party), and how he employs Puri’s remarkable face as a canvas in Aakrosh. (In that sense, this director-actor relationship was almost as intense as the ones between Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich, or Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski, or Orson Welles and Orson Welles.)

close to each other, making it easier to appreciate the similarities as well as the differences (and the similarities within the differences). Was struck again by Nihalani’s use of Om Puri (something I wrote about earlier in the context of Ardh Satya, Aghaat and Party), and how he employs Puri’s remarkable face as a canvas in Aakrosh. (In that sense, this director-actor relationship was almost as intense as the ones between Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich, or Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski, or Orson Welles and Orson Welles.)Some of the talking points during the Zoom class included:

- the use of the folk-theatre idiom in Bhavni Bhavai

- how “serious” actors respond to absurdist or slapstick comedy (obligatory Jaane bhi do Yaaro reference here)

- the breaking of the Fourth Wall — and the denunciation of the movie viewer as smug and apathetic — in films like Bhavni Bhavai, and the endings of Nagraj Manjule’s Fandry and Saeed Mirza’s Arvind Desai

- Nihalani’s use of extreme close-ups to create a sense of claustrophobia or entrapment

- the meaning and function of the famous dual ending of Bhavni Bhavai, with gentle idealism making way for savage, no-punches-pulled activism (as the angry Mohan Gokhale character tells the singing sutradhaar, “too gentle is your river / too slow is its flow / we won’t live forever/ it’s now or never”)

- the meaning and function of the famous dual ending of Bhavni Bhavai, with gentle idealism making way for savage, no-punches-pulled activism (as the angry Mohan Gokhale character tells the singing sutradhaar, “too gentle is your river / too slow is its flow / we won’t live forever/ it’s now or never”)- how a person from an underprivileged group might turn on — or become contemptuous of — his own origins after reaching a position of relative privilege (e.g. the Amrish Puri character in Aakrosh)

- what makes the structure of Aakrosh like an investigative thriller in places? My answer: the Naseer character Bhaskar is for long stretches the only “active” figure in the film, the only one constantly pushing ahead, trying to learn and uncover new things, immersing himself in his case much as he plunges joyfully into the sea in the film’s opening sequence. (Not very unlike the Ayushmaan Khurana character in Article 15. And of course, if Aakrosh were made today, Bhaskar too would be dismissed as a “Brahmannical saviour” in many quarters)

- The use of Hindi in Benegal's and Nihalani's films, the shift away from Urdu dialogues that were associated with a grander, less "realistic" film aesthetic, and how the studied naturalism of the New Wave films was linked to their use of language

- the politics of representation in both films, and how even the “parallel filmmakers” could become formulaic or create their own star system.

And probably a few other things I have forgotten. Anyway, the discussion went well, I think, and I’m toying with the idea of starting informal online classes myself. Anyone who is interested or has suggestions about what to discuss, get in touch. Otherwise I’ll go rogue and do something like best Norwegian horror films made before World War 1 or something such…

[Related posts: Nihalani's Aghaat and Ardh Satya; Party; Bhavni Bhavai]

Published on May 24, 2020 08:20

May 23, 2020

Animal-feeding at the Indian Garden Park, contd

[Earlier post about the Indian Garden Park here]

The feedback I often get on my animal-feeding/animal-rescue posts is that it’s heartening and inspiring to read about people like Ravi and Manoj and Pratima Devi and the many others who are doing so much good work. This is true, of course, but it’s important also to remember that all this is a drop in an ocean. For every heartwarming story about an animal being saved, there are dozens of other depressing cases where no meaningful help could be provided: with RWAs and other residents impeding rescue efforts, or the practical difficulties of getting hold of a frightened/timid animal that needed medical aid, or weak pups dying of Parvo.

The feedback I often get on my animal-feeding/animal-rescue posts is that it’s heartening and inspiring to read about people like Ravi and Manoj and Pratima Devi and the many others who are doing so much good work. This is true, of course, but it’s important also to remember that all this is a drop in an ocean. For every heartwarming story about an animal being saved, there are dozens of other depressing cases where no meaningful help could be provided: with RWAs and other residents impeding rescue efforts, or the practical difficulties of getting hold of a frightened/timid animal that needed medical aid, or weak pups dying of Parvo.

(Too many grisly stories to list, but it was particularly sad to hear yesterday about a resident Mother Dairy cat — who had delivered kittens just 3-4 weeks ago — being run over late at night by one of the many irresponsible drivers who are letting out all their pent-up lockdown energy by zipping wildly down the roads. The kittens had only recently opened their eyes and were very dependent on the mother; a local cat-lover has temporarily taken them in to feed them, but I don’t think she will be able to keep them for long.)

Which is all a roundabout way of saying that at times like this, one has to still keep sharing the good stuff when possible. Here are some images from the latest feeding expedition to the Indian Garden Park. My Dogs in Saket project collaborator Moutushi Sarkar and I went along with some food, but organiser-in-chief Rohit Chakrabarti had gathered a number of others together this time. Youngsters from an NGO, as well as volunteers who work for the German Embassy. A couple of them had come from as far as West Delhi, and it was great to see the reserves of compassion and empathy they have at their age. When I was in my twenties, despite my mother being such an animal-lover, street animals were on the periphery of my consciousness — I would never have taken this much time out for them.

Which is all a roundabout way of saying that at times like this, one has to still keep sharing the good stuff when possible. Here are some images from the latest feeding expedition to the Indian Garden Park. My Dogs in Saket project collaborator Moutushi Sarkar and I went along with some food, but organiser-in-chief Rohit Chakrabarti had gathered a number of others together this time. Youngsters from an NGO, as well as volunteers who work for the German Embassy. A couple of them had come from as far as West Delhi, and it was great to see the reserves of compassion and empathy they have at their age. When I was in my twenties, despite my mother being such an animal-lover, street animals were on the periphery of my consciousness — I would never have taken this much time out for them.

There is a video below of a few dogs swimming, hippo-like, in their private jungle pool. And another one of a dog eating directly from a young feeder’s hand, while another dog observes and learns (these forest animals take some time to get used to the feeders). And the photo, a nice composition by Rohit, has the alleged co-authors of the Dogs of Saket book that is in cold storage for now (unless one ends up self-publishing.)

There is a video below of a few dogs swimming, hippo-like, in their private jungle pool. And another one of a dog eating directly from a young feeder’s hand, while another dog observes and learns (these forest animals take some time to get used to the feeders). And the photo, a nice composition by Rohit, has the alleged co-authors of the Dogs of Saket book that is in cold storage for now (unless one ends up self-publishing.)

P.S. As always, anyone who is interested in coming along to the Indian Garden Park, most welcome. Rohit tells me there tends to be a feeder shortage on Wednesdays.

The feedback I often get on my animal-feeding/animal-rescue posts is that it’s heartening and inspiring to read about people like Ravi and Manoj and Pratima Devi and the many others who are doing so much good work. This is true, of course, but it’s important also to remember that all this is a drop in an ocean. For every heartwarming story about an animal being saved, there are dozens of other depressing cases where no meaningful help could be provided: with RWAs and other residents impeding rescue efforts, or the practical difficulties of getting hold of a frightened/timid animal that needed medical aid, or weak pups dying of Parvo.

The feedback I often get on my animal-feeding/animal-rescue posts is that it’s heartening and inspiring to read about people like Ravi and Manoj and Pratima Devi and the many others who are doing so much good work. This is true, of course, but it’s important also to remember that all this is a drop in an ocean. For every heartwarming story about an animal being saved, there are dozens of other depressing cases where no meaningful help could be provided: with RWAs and other residents impeding rescue efforts, or the practical difficulties of getting hold of a frightened/timid animal that needed medical aid, or weak pups dying of Parvo. (Too many grisly stories to list, but it was particularly sad to hear yesterday about a resident Mother Dairy cat — who had delivered kittens just 3-4 weeks ago — being run over late at night by one of the many irresponsible drivers who are letting out all their pent-up lockdown energy by zipping wildly down the roads. The kittens had only recently opened their eyes and were very dependent on the mother; a local cat-lover has temporarily taken them in to feed them, but I don’t think she will be able to keep them for long.)

Which is all a roundabout way of saying that at times like this, one has to still keep sharing the good stuff when possible. Here are some images from the latest feeding expedition to the Indian Garden Park. My Dogs in Saket project collaborator Moutushi Sarkar and I went along with some food, but organiser-in-chief Rohit Chakrabarti had gathered a number of others together this time. Youngsters from an NGO, as well as volunteers who work for the German Embassy. A couple of them had come from as far as West Delhi, and it was great to see the reserves of compassion and empathy they have at their age. When I was in my twenties, despite my mother being such an animal-lover, street animals were on the periphery of my consciousness — I would never have taken this much time out for them.

Which is all a roundabout way of saying that at times like this, one has to still keep sharing the good stuff when possible. Here are some images from the latest feeding expedition to the Indian Garden Park. My Dogs in Saket project collaborator Moutushi Sarkar and I went along with some food, but organiser-in-chief Rohit Chakrabarti had gathered a number of others together this time. Youngsters from an NGO, as well as volunteers who work for the German Embassy. A couple of them had come from as far as West Delhi, and it was great to see the reserves of compassion and empathy they have at their age. When I was in my twenties, despite my mother being such an animal-lover, street animals were on the periphery of my consciousness — I would never have taken this much time out for them. There is a video below of a few dogs swimming, hippo-like, in their private jungle pool. And another one of a dog eating directly from a young feeder’s hand, while another dog observes and learns (these forest animals take some time to get used to the feeders). And the photo, a nice composition by Rohit, has the alleged co-authors of the Dogs of Saket book that is in cold storage for now (unless one ends up self-publishing.)

There is a video below of a few dogs swimming, hippo-like, in their private jungle pool. And another one of a dog eating directly from a young feeder’s hand, while another dog observes and learns (these forest animals take some time to get used to the feeders). And the photo, a nice composition by Rohit, has the alleged co-authors of the Dogs of Saket book that is in cold storage for now (unless one ends up self-publishing.)

P.S. As always, anyone who is interested in coming along to the Indian Garden Park, most welcome. Rohit tells me there tends to be a feeder shortage on Wednesdays.

Published on May 23, 2020 07:54

May 16, 2020

A beginner's guide to the best of contemporary Malayalam cinema

[A couple of weeks before the first lockdown was announced, I was to begin a video series for the recently launched Cinemaazi project. That is obviously up in the air now, but I’m doing some writing for the website. Here’s the first piece, a shout-out for some excellent films from what is arguably the country's most vibrant cinematic culture today. Most of these films are streaming on Prime Video or Netflix]

------------------------------------------------

“You don’t know my story, manager,” a young African footballer named Samuel haltingly tells his club manager Majeed, “Our life… not like your life. You don’t understand.” Samuel goes on to describe the crippling poverty back home, and his efforts to build a better life for his family by coming to India where athletic foreign players are in high demand. But now he is stuck in a small Kerala town, unable to return because his passport is lost and there are ongoing investigations against refugees.

The 2018 Malayalam comedy-drama Sudani from Nigeria centres on the cultural disconnect, slowly yielding to friendship, between manager and player – and in fact this disconnect is written into the film’s very title: Samuel is Nigerian, but some locals reflexively think of Africans as “Sudani”, not realising that Sudan and Nigeria are different countries. Eventually he stops trying to explain the difference.

The 2018 Malayalam comedy-drama Sudani from Nigeria centres on the cultural disconnect, slowly yielding to friendship, between manager and player – and in fact this disconnect is written into the film’s very title: Samuel is Nigerian, but some locals reflexively think of Africans as “Sudani”, not realising that Sudan and Nigeria are different countries. Eventually he stops trying to explain the difference.

If that generalisation makes you chuckle, remember that there are many educated north Indians who think of south India, and south Indian films, in similarly amorphous or broad-stroke terms. Even someone who is sensitive enough, or politically correct enough, to avoid terms like “Madrasi” (which so many of us Hindi-film viewers used in the 1980s) might remain uncertain about which state speaks Telugu and which speaks Malayalam; and even someone who identifies as a movie buff might think of Tamil and Malayalam cinema as interchangeable. (A friend, a critic from Tamil Nadu, once told me about how a Mumbai-based employer assumed that he would understand Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam without the aid of subtitles.)

None of this is said smugly – I speak as one who has been implicated himself. Though I began exploring many sorts of international cinemas in my early teens, “south Indian films” remained a big gap on my viewing resume. Consequently, my recent encounters with contemporary Malayalam cinema have been both daunting and exciting, and a reminder of those teen years spent with subtitled films: navigating one’s way through cultures one knew little about, learning about the oeuvres of this or that director, cinematographer or music director, gradually identifying and warming to actors as one saw them across a number of roles.

Going on such a voyage of discovery in one’s forties is more unsettling, very different from scampering to film festivals and Embassy libraries as an adolescent; even the most enthusiastic and open-minded film buffs tend to stay in comfort zones beyond a certain age. But some of the processes, the connecting of dots, stay the same. For instance, my reason for choosing to watch Sudani from Nigeria wasn’t just that it was available on Netflix (many fine Malayalam films are now): it was that I had lately become familiar with the work of the wonderful actor Soubin Shahir, who plays Majeed here. Watching him in the film’s trailer, and then in the first scene, was reassuring and provided an entry point.

Through watching many fine films from the state recently, I have been learning about both the cinematic idioms and aspects of local culture and daily life depicted in them: from the forms that religious practice takes in Keralite Christian and Muslim households to how men drape the mundu – folded up or worn full – depending on occasion and whom they are speaking to. But of course, this is very much a work in progress, with many discoveries yet to be made. With that caveat, here are some films to get you started:

Kumbalangi Nights

Kumbalangi Nights

Even those who don’t follow “regional cinema” may well have heard of Madhu C Narayanan’s much-acclaimed Kumbalangi Nights. This is a good starting point for the untrained viewer, because it is a warm, accessible, narrative-driven film with lilting music, a terrific mix of comedy and drama, and super performances by some key actors. The story centres on the rough-hewn Saji (Soubin Shahir again) and his three brothers, living and squabbling together in a Kochi village. Theirs is a caveman existence in some ways, which has a lot to do with the fact that there is no moderating female presence in their lives – but as this slowly changes, their emotional lives undergo a shift too. What really sets the cat among the pigeons, though, is the nearby presence of a more seemingly balanced sort of family headed by the fastidious Shammi (Fahadh Faasil), who thinks of himself as a “complete man”.

The contrast between Saji and Shammi – two very different sorts of patriarchs in very different situations – lies at the heart of this story about masculinity, family ties, the class divide, and what it means to be civilised or savage. Kumbalangi Nights is one of those deceptive films that achieve narrative complexity without seeming to make much of an effort. When you think about it afterwards, you might think mainly of the funny scenes, many of which centre on Faasil’s performance as the control freak who starts short-circuiting like a defective robot when his authority is challenged; but when you’re watching it, it is impossible not to feel the emotional resonance of scenes like the one where Saji realises he needs to go to a psychiatrist and cry his heart out. Or the delicacy of the romance between the mute Bonny and a visiting American. Or an unforgettable little image of a Bluetooth speaker playing gentle music in a messy house late at night, glimpsed from the lake far outside.

Ee. Ma. Yau and Jallikattu

Ee. Ma. Yau and Jallikattu

Lijo Jose Pellissery is one of the bona-fide auteurs of contemporary Indian cinema, a director who leaves a distinct visual and aural stamp on most of his work, and the last few years have seen a spate of acclaimed work from him, notably Angamaly Diaries, Ee. Ma. Yau. and Jallikattu. Here’s something I find fascinating about Pellissery: on the one hand, he clearly puts a lot of thought and craft into his shot compositions and gives the impression of maintaining rigid control over his mise-en-scene – in this, he belongs to the tradition of directors like a Victor Erice or a Stanley Kubrick. And yet, there also seems plenty of space for the loose, serendipitous moment; for the way in which the interplay between two or more actors might change the dynamics of a scene.

The first Pellissery film I watched was Jallikattu, an extraordinarily ambitious account of a village hunt for a runaway buffalo, co-written by the acclaimed novelist S Hareesh. Here is a film full of hypnotic images and sound design, starting with a striking montage of people in various stages of sleep or wakefulness, and insects going about the day’s work at dawn – and ending with a sequence that makes explicit the link between this story and primitive humans hunting for food. But my favourite Pellissery film so far is Ee.Ma. Yau, a lovely portrayal of death as both comedy and tragedy.

Pellissery is known for the fluidity of his long takes – the camera weaving in and out of spaces, encompassing the actions of a number of different characters – but what’s equally seamless here is how the narrative moves between hysteria, farce and deep sadness. I haven’t seen many other films that manage to be so funny, dignified and mournful at the same time, often achieving all these things within the same scene (depending on which part of the crowded frame you are looking at). There is genuine loss and grief, but there are also marvellous depictions of the more performative versions of grief – most notably in the lamenting of the dead man’s wife Mariam, whose her histrionics become like a tragi-comic chorus running through the film.

Pellissery is known for the fluidity of his long takes – the camera weaving in and out of spaces, encompassing the actions of a number of different characters – but what’s equally seamless here is how the narrative moves between hysteria, farce and deep sadness. I haven’t seen many other films that manage to be so funny, dignified and mournful at the same time, often achieving all these things within the same scene (depending on which part of the crowded frame you are looking at). There is genuine loss and grief, but there are also marvellous depictions of the more performative versions of grief – most notably in the lamenting of the dead man’s wife Mariam, whose her histrionics become like a tragi-comic chorus running through the film.

Virus

Aashiq Abu is another of the most respected Malayali directors and producers, and his 2019 film Virus – a taut dramatization of the challenges facing medical professionals during the Nipah outbreak – is one reason why. Virus is, obviously, a very topical film in the current moment – perhaps even more so given the widespread admiration for Kerala’s efficiency in handling the Covid pandemic. But thematic relevance apart, this is first and foremost a superbly structured film, bringing the quality of a well-paced investigative thriller to a real-life tragedy. It moves from the small picture to the big one, incorporating the personal stories of many individuals infected (or affected) by the virus, as well as what the nature of the spread tells us about the society in which it occurs. It is chillingly familiar in its depiction of the panic caused – even within the medical fraternity – by a disease about which not much is known; and yet it offers hope too.

Aashiq Abu is another of the most respected Malayali directors and producers, and his 2019 film Virus – a taut dramatization of the challenges facing medical professionals during the Nipah outbreak – is one reason why. Virus is, obviously, a very topical film in the current moment – perhaps even more so given the widespread admiration for Kerala’s efficiency in handling the Covid pandemic. But thematic relevance apart, this is first and foremost a superbly structured film, bringing the quality of a well-paced investigative thriller to a real-life tragedy. It moves from the small picture to the big one, incorporating the personal stories of many individuals infected (or affected) by the virus, as well as what the nature of the spread tells us about the society in which it occurs. It is chillingly familiar in its depiction of the panic caused – even within the medical fraternity – by a disease about which not much is known; and yet it offers hope too.

Most movingly for me at a personal level, Virus is also about the connectedness of life beyond the human world – a theme that runs through many major films and novels from Kerala, where the many components of the natural world are a constant, humming presence in the background, sometimes making it to the foreground as well. This film may have my favourite ending of any Indian film I have seen in the last few years – a mystical scene involving a baby fruit-bat that has fallen off its tree. Without underlining anything, the scene offers a small reminder of how both human strengths and vulnerabilities are inextricably linked with the planet’s other living creatures, our place in a larger ecosystem, and the many ways in which we can harm and help each other. It also reminded me of a beautiful, graceful moment in Ee.Ma.Yau., an image of the souls of two men, a dog and a duck all preparing for a final journey.

Uyare

Among the films that are relatively conventional in their telling but derive their effect from a powerful performance, a good example is Uyare, about an aviation student named Pallavi (played by Parvathy Thiruvothu) whose life and career threaten to fall apart after an acid-attack by her boyfriend. The metaphor of a woman “taking off”, refusing to be tethered by a patriarchal world, is perhaps a little too obvious: that’s inevitable in a story about a pilot struggling to be accepted in her profession while also caught in a nasty relationship that culminates in an insecure man disfiguring her face. But along with its big-message moments, Uyare also has some sharp little observations about the world that its protagonist has to negotiate. Such as the scene where one of Pallavi’s male colleagues is bemused by the signs outside a toilet, and she explains that the single “Blah” is supposed to represent men while a nonstop “Blah blah blah blah blah” indicates the ladies’ room. (“Because men talk only when necessary – at least, that’s what men say.”) Which genius thought this up, the colleague asks, and she replies, “I don’t know, but it must have been a man.”

Scenes like this are lightly played, but they add up like jigsaw pieces that go into the making of a more sinister picture, one where women are first gently patronised and then oppressed or bullied with force. And Parvathy’s intelligent, sensitive performance – unafraid to move between strength and vulnerability – is a big part of the film’s effect (her performance as an unobtrusive but efficient contamination-tracker was also central to Virus).

Scenes like this are lightly played, but they add up like jigsaw pieces that go into the making of a more sinister picture, one where women are first gently patronised and then oppressed or bullied with force. And Parvathy’s intelligent, sensitive performance – unafraid to move between strength and vulnerability – is a big part of the film’s effect (her performance as an unobtrusive but efficient contamination-tracker was also central to Virus).

Vikruthi and Maheshinte Prathikaaram

There is also a subgenre of slice-of-life stories built around a seemingly everyday incident that spirals into something big, and eventually reveals things about the characters and the society they belong to. Two good instances are the 2019 Vikruthi (Mischief) and the 2016 Maheshinte Prathikaaram (Mahesh’s Revenge). The former is based on a real-life story about a speech-impaired man, Eldho (wonderfully played by National Award-winner Suraj Venjaramoodu), who becomes the butt of scorn after he falls asleep on a train in exhaustion and a fellow passenger takes a photo of him. While Eldho is obviously the object of the film’s sympathy, what Vikruthi does expertly is to intercut his story with that of the man who is the agent of his humiliation, and who also gets to experience what it is like to be persecuted – this narrative structure eschews a straightforward victim-oppressor tale in favour of a nuanced examination of how two paths can collide with unfortunate results, and how an instant-gratification, technology-driven society is quick to judge people on very little evidence.

Maheshinte Prathikaaram is another many-complexioned film that seems unobtrusive to begin with, but slowly grows into the story of a man who must move towards a moment of private reckoning. Fahadh Faasil plays a photographer who gets humiliated in a street brawl and vows not to wear slippers again until he has had his revenge. You’d think a premise like that could make for a straightforward action drama or a straightforward slapstick comedy, but the storytelling is unconventional and detour-laden, and (much like Kumbalangi Nights, Ee. Ma. Yau. and many other films) the film milks whimsical humour from sombre situations. (Funerals, for example, can be both romantic and funny.)

There is a climactic fight sequence and it’s superbly done – it is messy, realistic, comical, but also conveys what is at stake for Mahesh, how his whole sense of self is at stake. And yet, after all that is over and the task has been accomplished, the film ends on an almost sheepishly charming, down-to-earth note. Want a story about a seemingly ordinary man caught in a slightly-unusual situation, told with heart and depth? Here you go.

Unda

One of the by-products of a cinematic culture that is moving from personality cults towards more grounded and realistic representations is that there are slyly affectionate inside jokes about older films and actors. For instance, Maheshinte Prathikaaram has a scene where a character, watching a film on TV, holds forth on the relative merits of superstars Mammootty and Mohanlal: the former will play any role, he says — a tree-climber, a tea shop owner, whatever – but the latter is great because he will only do “top-class” parts. (The reference won’t be immediately clear to an outsider, but this is a dig at Mohanlal’s tendency to play upper-caste characters.)

One of the by-products of a cinematic culture that is moving from personality cults towards more grounded and realistic representations is that there are slyly affectionate inside jokes about older films and actors. For instance, Maheshinte Prathikaaram has a scene where a character, watching a film on TV, holds forth on the relative merits of superstars Mammootty and Mohanlal: the former will play any role, he says — a tree-climber, a tea shop owner, whatever – but the latter is great because he will only do “top-class” parts. (The reference won’t be immediately clear to an outsider, but this is a dig at Mohanlal’s tendency to play upper-caste characters.)

In this light, it’s intriguing to observe the friction within a film when a superstar of yore gets cast in a relatively non-showy part. In the 2019 Unda, Mammootty plays Mani sir, the leader of a police unit that is sent to Naxalite territory in Chhatisgarh for election duty. These cops are clearly out of their depth here, as lost as the “Sudani from Nigeria” was in a Keralite town – they struggle with lack of resources and information, language barriers, the hostility and suspicion that comes their way from the locals, and the note of terror that is struck with every uttering of the word “Maoist”.

It’s amusing to see Mammootty billed as “Megastar” in the opening credits of this film, where his role is so subdued, and where his character even becomes paralysed in a moment of crisis, unable to issue a command. He does briefly get to be the super-cop action figure in the climax, but the dominant image for much of the film is that of an avuncular man in a check-shirt, buying Parle G biscuits to distribute among his unit; or his eyebrows furrowing with concern and incomprehension when people speak urgently in Hindi in his presence.