Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 25

May 14, 2020

Feeding diaries, contd: dogs and nilgai in the Indian Garden Park

I have lived in Saket for 33 years, but it took a lockdown-driven crisis for me to visit the Indian Garden Park (just 300-400 metres from my house) for the first time. Eleven acres of forest land, not too well maintained (which is of course the case for many such spaces in Delhi) but good for long walks, and some interesting terrain: sloping paths, little ruins, sudden inclines and gullies (this area was originally part of a fort).

I have lived in Saket for 33 years, but it took a lockdown-driven crisis for me to visit the Indian Garden Park (just 300-400 metres from my house) for the first time. Eleven acres of forest land, not too well maintained (which is of course the case for many such spaces in Delhi) but good for long walks, and some interesting terrain: sloping paths, little ruins, sudden inclines and gullies (this area was originally part of a fort).  For the first month of the lockdown, a resident named Rohit Chakrabarti began going to the park every day with heaps of food for the 30-odd dogs trapped inside. In the past few weeks, a few others have been helping out; and with the help of Maneka Gandhi’s team, the main gate has now been opened for designated feeders coming at specified times.

For the first month of the lockdown, a resident named Rohit Chakrabarti began going to the park every day with heaps of food for the 30-odd dogs trapped inside. In the past few weeks, a few others have been helping out; and with the help of Maneka Gandhi’s team, the main gate has now been opened for designated feeders coming at specified times. I am not looking to develop regular bonds with new groups of dogs outside the many I already know and feed outside two flats in Saket (and on the route between those flats), but it was nice to get some feeding done yesterday. Not so nice to see that some idiotic youngsters have made a habit of breaking the clay bowls in which water is left for the animals. And not so good to hear about the dozens of pups who have died of starvation/dehydration/parvo here in recent times, despite the feeders’ efforts. (But that is one of the inevitable sideshows of these times; on my walk this morning, I saw a large monkey lying dead near a parked car.)

There are nilgai in the Indian Garden Park too; in the video here, you can see Rohit feeding one. Shy animals, as you might know, but extreme hunger overcomes that after a few days.

There are nilgai in the Indian Garden Park too; in the video here, you can see Rohit feeding one. Shy animals, as you might know, but extreme hunger overcomes that after a few days. Anyone here who lives in the vicinity of Saket/Sainik Farms/Saidulajab and feels like coming across one day with food for the dogs, let me know. It takes around an hour, and

it provides some good exercise. (During the last two months, I have averaged around 12-13K steps per day, but I crossed 20K steps yesterday thanks to the park visit – and wore out my last decent pair of shoes.)

it provides some good exercise. (During the last two months, I have averaged around 12-13K steps per day, but I crossed 20K steps yesterday thanks to the park visit – and wore out my last decent pair of shoes.)

Published on May 14, 2020 01:58

May 10, 2020

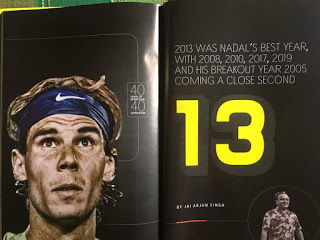

Rafael Nadal in 2013: an essay for a Sportstar book

[Earlier this year, during that strange and unfathomable time when sports tournaments were being played around the world in crowded arenas, a new book celebrating 40 years of Sportstar magazine was published. The format had 40 writers doing essays about a key year in the career of 40 sportspersons. My piece is about what I consider Rafa Nadal’s best year, 2013, and I was very excited when Sportstar asked me to write it. Having been an avid reader/hoarder of the magazine during my cricket-watching years more than two decades ago (especially when someone like Nirmal Shekar or R Mohan wrote a piece about one of my favourites), it feels warm and fuzzy to be IN a Sportstar for the first time. Not to mention that Sachin Tendulkar and I are, ahem, co-writers here — and rival co-writers to boot, since his contribution is about Roger Federer! Back in 1996, I could never have guessed that such a thing would come to pass.

[Earlier this year, during that strange and unfathomable time when sports tournaments were being played around the world in crowded arenas, a new book celebrating 40 years of Sportstar magazine was published. The format had 40 writers doing essays about a key year in the career of 40 sportspersons. My piece is about what I consider Rafa Nadal’s best year, 2013, and I was very excited when Sportstar asked me to write it. Having been an avid reader/hoarder of the magazine during my cricket-watching years more than two decades ago (especially when someone like Nirmal Shekar or R Mohan wrote a piece about one of my favourites), it feels warm and fuzzy to be IN a Sportstar for the first time. Not to mention that Sachin Tendulkar and I are, ahem, co-writers here — and rival co-writers to boot, since his contribution is about Roger Federer! Back in 1996, I could never have guessed that such a thing would come to pass.At the same time, without getting into sordid details, problems cropped up with the book – among other things, the production was delayed and delayed again and then again, and the essay had to be reworked more than a year after I submitted it. Won’t focus on that here, though. Here is the piece]

---------------------------------------------------

If you’re a sports lover who has pledged his troth to a player or team, you get used to moments of euphoria coexisting with moments of soul-crushing disappointment. Especially in a tense, oscillating match such as a Grand Slam final, where each hard-fought point, each rally ended with a decisive statement of intent, can make a big difference – not just in terms of who wins the current game, but for the psychological stakes involved.

If you’re a sports lover who has pledged his troth to a player or team, you get used to moments of euphoria coexisting with moments of soul-crushing disappointment. Especially in a tense, oscillating match such as a Grand Slam final, where each hard-fought point, each rally ended with a decisive statement of intent, can make a big difference – not just in terms of who wins the current game, but for the psychological stakes involved.In my most unforgettable sports memory, elation was preceded (for just a split second) by dismay, and the dismay was caused by a misunderstanding – the sort of misunderstanding that any long-time fan of Rafael Nadal might be prone to.

It’s that game, and that point at the end of the third set of the 2013 US Open final between Nadal and his most dangerous opponent ever, Novak Djokovic. Rafa has a break point that is also a set point. The rally stretches on, both men first playing cautiously, then speeding up the pace, turning defence to offence while sustaining a level of intensity that only their matches can produce. Djokovic’s forehand targets Rafa’s backhand, seems about to wrest control, but then Rafa gets the ball on his stronger side and lets one rip, smashing a forehand deep in the deuce court – so deep that, watching on a non-HD TV, I think the ball has gone just long; and meanwhile, out of the corner of my eye, I see Rafa looking like he has awkwardly fallen to his knee.

It’s all over, I tell myself in the time it takes these perceptions to coalesce: Djokovic will go on to win the game and then the set; and now it looks like Rafa’s famously fragile knee is in trouble, too; yet another injury in a career obstructed by them?

In another microsecond, I knew what had really happened. Rafa had caught the line with that blazing forehand; Djokovic, flailing, hadn’t been able to handle it; and Rafa, who had stumbled a little after hitting the shot, allowed himself to get down on that dodgy limb and celebrate with a mighty fist pump. Cut to his family and team in the stands, his girlfriend and dad exchanging goofy, disbelieving grins, the latter holding his head as if to stop a vein from bursting, like he had at the end of the 2008 Wimbledon final, like so many Nadal fans have done so, so often.

(Here is the point in question. The video embedded below has the full match.)

It’s hard to explain how much was at stake in that point, and what an incredible set this had been – a seesaw and a roller-coaster thrown into one. With the match tied, Rafa had fallen 0-2 behind in the third, and he came perilously close to going down two breaks; Djokovic was in one of his terrifying runs of form, reminiscent of 2011, when the brilliant Serb won six straight finals against Rafa. But Nadal held, broke back to make it three-all – and then went down 0-40 again before holding to reach 5-4. Then came that final game, with Rafa winning four straight points to steal the set. And Djokovic wilted, going down tamely in the fourth.

That game, that point, that moment, summarises what I think of as Rafa’s greatest season – which may be an unpopular view, because others will point to 2010, the only year in which he won three Slams, and still others to 2008 when he played that extraordinary Wimbledon final to dethrone Roger Federer and became world No. 1 for the first time after three straight years of tailing his older rival.

But 2013 is extra special for many reasons. In terms of the quality of competition he stared down, it was certainly superior to 2010 – there were far more triumphs against top-10 players, including three very satisfying wins against Djokovic. Two of those came at Slam level – the classic five-setter in the Roland Garros semifinals and the US Open final – but just as pleasing was the hard-fought win in the Montreal Masters semifinals, one of Rafa’s many high points during the most impressive non-clay run of his career: sweeping the three big autumn tournaments in North America – the Canada and Cincinnati Masters followed by the US Open. This is something that even hard-court masters like Federer and Djokovic haven’t done, and I rate it among the highest of Rafa’s achievements.

Then there is the fact that the 2013 season began with Rafa slowly, very slowly making his way back from one of his many demoralising injury layoffs. He didn’t play the Australian Open, opting to find form in small South American clay tournaments in February – losing the Vina del Mar final to world No. 73 Horacio Zeballos, then working his way up until he was confident enough, and ready enough, to win the Indian Wells Masters, beating Federer along the way and Juan Martín del Potro in the final. These were still baby steps, of course, on the road to the form that saw him beat the dominant Djokovic in vital matches later in the season.

So, 2013 for the win? I think so. With 2010, 2008, 2019, 2017 and his breakout year 2005 (first Slam, four Masters 1000 wins) coming a close second (in more or less that order).

****

There are some obvious things to be said about the experience of being an obsessive Nadal fan, and some of them were on view if you saw the expressions on his team’s faces at the end of that third set. They were probably thinking exactly what I, and millions of other Nadal fans, have thought thousands of times over the years: How did he pull that off?

Having followed him match by match, tournament by tournament, since early 2006 – pacing up and down in front of the TV, pausing between points to refresh the chat page on whichever tennis website I’m logged into at the time – I know all the mood swings. You feel exhausted, almost like you have played the match yourself. You wish, at moments, that he were a more efficient, balletic player like Federer – so that, win or lose, at least the match would be over quickly and you could get back to what remains of your life. But you also appreciate what he means when he says, in interviews, that “suffering” through a match is often more important than the final result. And that he can take nothing for granted, not even against the lowest-ranked opponent.

Having followed him match by match, tournament by tournament, since early 2006 – pacing up and down in front of the TV, pausing between points to refresh the chat page on whichever tennis website I’m logged into at the time – I know all the mood swings. You feel exhausted, almost like you have played the match yourself. You wish, at moments, that he were a more efficient, balletic player like Federer – so that, win or lose, at least the match would be over quickly and you could get back to what remains of your life. But you also appreciate what he means when he says, in interviews, that “suffering” through a match is often more important than the final result. And that he can take nothing for granted, not even against the lowest-ranked opponent.And there are the deflating blows that come with realising that his body has let him down yet again, just when you felt he was on the cusp of a big achievement or was rounding into peak form – as happened when he had to withdraw after two rounds of the 2016 French Open.

But for a diffident fan like me, following Rafa has also been a matter of constantly being surprised in good ways: the goalposts for what is possible have shifted and shifted and shifted again. Back in 2006, I was surprised when he beat Federer in the French Open final (after barely squeaking through in the marathon Rome Masters final they played a few weeks earlier, and struggling through early rounds at the French) because I thought it was pre-destined that Federer would complete the Roger Slam. Then I was surprised when Rafa won his first non-clay major in 2008. (One persuasive narrative back then was that Djokovic, who had just won the Australian Open, was set to be the true all-court successor to Federer.) I was surprised when he won a hard-court major at the 2009 Australian Open (after playing a five-hour semifinal), surprised when he made a brilliant comeback in 2010 after a disappointing few injury-afflicted months, surprised when he overcame his 2011-2012 setbacks against Djokovic.

I was astonished when he returned to No. 1 in 2017 after two strife-filled seasons where it had seemed clear that he was in a sportsman’s final twilight. And most recently, when he took back the number one spot from Djokovic near the end of the 2019 season (a season that had begun with the Serb conclusively overpowering Rafa in the Australian Open final) – and then rounded his year off by helping Spain win the Davis Cup in its new format, all the while celebrating and encouraging his countrymen like a teenager in the arena for the first time.

I was astonished when he returned to No. 1 in 2017 after two strife-filled seasons where it had seemed clear that he was in a sportsman’s final twilight. And most recently, when he took back the number one spot from Djokovic near the end of the 2019 season (a season that had begun with the Serb conclusively overpowering Rafa in the Australian Open final) – and then rounded his year off by helping Spain win the Davis Cup in its new format, all the while celebrating and encouraging his countrymen like a teenager in the arena for the first time.To describe sports fandom as a roller-coaster ride would be to imply that the object of that fandom is mercurial or inconsistent, burning bright but briefly. But with Rafa, the greatest and most improbable of his legacies – one that most observers would never have predicted a decade ago – involves longevity. In 2014, he became the first male player to have won at least one major in 10 consecutive years – an achievement largely determined by his mastery of the clay at Roland Garros, but no less impressive for that. As of December 2019, he has been in the top 10 for over 760 consecutive weeks, never falling out of that hallowed space since he first entered it in early 2005 – and is almost guaranteed to break Jimmy Connors’s record of 787 weeks.

This wasn’t supposed to happen! These are achievements one expects from the more “efficient” great players, like Federer or Djokovic or Pete Sampras.

Given how accustomed Rafa’s fans are to “suffering” with him, it feels almost poetically appropriate that when I first began putting together notes for this piece, Nadal was in the midst of another injury-related setback. With Djokovic having made his own comeback, and generally appearing less prone to recurring injuries, who would bet on Rafa continuing to be dominant in his mid-thirties?

But after everything that has happened from 2005 on, who could bet against it? For many of us, watching Rafa make repeated comebacks and play tireless defence-to-offence against a sportsman’s biggest nemesis, Father Time, has been more fulfilling than watching all those close matches against his biggest flesh-and-blood rivals. His playing style won’t let him continue for more than another three or four seasons, some commenters (including some of us gloomy fans) were saying when he was still a teen. Look how that turned out.

Published on May 10, 2020 08:31

May 7, 2020

Lockdown chronicles – a reunion of old foes: a man in a mask and a dog in a muzzle

More about animal-care. I wrote five years ago about the wonderful incident of the black dog in our colony who made it all the way back to Saket after running away from Friendicoes, where we had sent her to be spayed (the post is here, for anyone interested). This dog, who still doesn't have a name apart from a generic Kaali, is the mother of my Lara, and as a result I feel a strong connection with her – even though she only sometimes came to our lane and I didn’t see her for days or weeks on end. In the past year or so, now that she is very old, she has settled down a bit and is being looked after by a nearby resident; I give her some paneer and biscuits whenever I see her.

Kaali developed a nasty, festering ear injury a few days ago, and once I realised how serious it was, I called Ravi and Manoj, who do so much animal-feeding and rescuing for us during these locked-down days. With the help of a guard, we managed to get her leashed and into an enclosed space (which can be the hardest part of these missions), and for the past three days extensive treatment has been underway. Anyone who has seen a deep ear injury in a street dog will know what I mean when I say this was a touch-and-go case. The initial cleaning resulted in the evacuation of literally dozens of big dead maggots – a day’s delay and they would probably have burrowed into her brain. But Ravi, as usual, with limited resources, carrying his own very basic medical kit everywhere, did a great job. Chances are she will recover fully in a few days.

Kaali developed a nasty, festering ear injury a few days ago, and once I realised how serious it was, I called Ravi and Manoj, who do so much animal-feeding and rescuing for us during these locked-down days. With the help of a guard, we managed to get her leashed and into an enclosed space (which can be the hardest part of these missions), and for the past three days extensive treatment has been underway. Anyone who has seen a deep ear injury in a street dog will know what I mean when I say this was a touch-and-go case. The initial cleaning resulted in the evacuation of literally dozens of big dead maggots – a day’s delay and they would probably have burrowed into her brain. But Ravi, as usual, with limited resources, carrying his own very basic medical kit everywhere, did a great job. Chances are she will recover fully in a few days.

Two things about this: 1) When I was a child, probably right up to age 11 or 12, my stock answer to the question “What will you be when you grow up?” was “A veterinarian.” (Then, of course, I got older and wiser and the answer became “a chartered accountant”, which seemed the practical thing, and which is what I still tell anyone who asks me the question today.)

Very often in recent times I have felt like that childhood dream has been belatedly realised – that I have become, if not anything like a full-blown vet, at least an acceptable apprentice. (My most damaged and troublesome dog Chameli has usually been the conduit for this.) And never has this feeling been more pronounced than in the past few days: no surprise when one is administering various sorts of medicines at regular intervals, cleaning deep and ugly wounds, and assisting in the removal of clusters of maggots from delicate places. My mother, who smiled proudly whenever I said “a vet” as a child, would have liked hearing about these adventures.

2) As I mentioned in that old post, Ravi was Kaali’s nemesis in 2015 – he was the one who took her to Friendicoes for her operation, she escaped from him and would bolt, snarling, every time she heard the sound of his car when he tried to find her. Now, five years later, their paths have crossed again in unexpected circumstances, and it feels like things have come full circle – it’s a tale that has redemption, grace, forgiveness, all those grand and inflated human themes. She has been terrified during the treatment, but there’s a more resigned, senior-citizen look in her eyes when she sees him, as if she’s saying, “Well, I can’t run away from you all my life, and there isn’t much life left now anyway, so let’s get on with this.” (Meanwhile, Ravi tells her elaborate stories in a steadily comforting voice even as he does the treatment: things like “Haan haan, Friendicoes mein woh Chhotu abhi bhi aapke baare mein poochte rahta hai – woh kahin phirse toh nahin bhaag gayi?”)

2) As I mentioned in that old post, Ravi was Kaali’s nemesis in 2015 – he was the one who took her to Friendicoes for her operation, she escaped from him and would bolt, snarling, every time she heard the sound of his car when he tried to find her. Now, five years later, their paths have crossed again in unexpected circumstances, and it feels like things have come full circle – it’s a tale that has redemption, grace, forgiveness, all those grand and inflated human themes. She has been terrified during the treatment, but there’s a more resigned, senior-citizen look in her eyes when she sees him, as if she’s saying, “Well, I can’t run away from you all my life, and there isn’t much life left now anyway, so let’s get on with this.” (Meanwhile, Ravi tells her elaborate stories in a steadily comforting voice even as he does the treatment: things like “Haan haan, Friendicoes mein woh Chhotu abhi bhi aapke baare mein poochte rahta hai – woh kahin phirse toh nahin bhaag gayi?”)

Today, after we removed her muzzle and leash and set her free, I was surprised to see her walking back towards him and wagging her tail a bit, even though she had been shrieking in pain when her ears were being cleaned. Displays of trust like this make many of these situations seem worth the effort. [More about Ravi and Manoj and their efforts here]

Kaali developed a nasty, festering ear injury a few days ago, and once I realised how serious it was, I called Ravi and Manoj, who do so much animal-feeding and rescuing for us during these locked-down days. With the help of a guard, we managed to get her leashed and into an enclosed space (which can be the hardest part of these missions), and for the past three days extensive treatment has been underway. Anyone who has seen a deep ear injury in a street dog will know what I mean when I say this was a touch-and-go case. The initial cleaning resulted in the evacuation of literally dozens of big dead maggots – a day’s delay and they would probably have burrowed into her brain. But Ravi, as usual, with limited resources, carrying his own very basic medical kit everywhere, did a great job. Chances are she will recover fully in a few days.

Kaali developed a nasty, festering ear injury a few days ago, and once I realised how serious it was, I called Ravi and Manoj, who do so much animal-feeding and rescuing for us during these locked-down days. With the help of a guard, we managed to get her leashed and into an enclosed space (which can be the hardest part of these missions), and for the past three days extensive treatment has been underway. Anyone who has seen a deep ear injury in a street dog will know what I mean when I say this was a touch-and-go case. The initial cleaning resulted in the evacuation of literally dozens of big dead maggots – a day’s delay and they would probably have burrowed into her brain. But Ravi, as usual, with limited resources, carrying his own very basic medical kit everywhere, did a great job. Chances are she will recover fully in a few days. Two things about this: 1) When I was a child, probably right up to age 11 or 12, my stock answer to the question “What will you be when you grow up?” was “A veterinarian.” (Then, of course, I got older and wiser and the answer became “a chartered accountant”, which seemed the practical thing, and which is what I still tell anyone who asks me the question today.)

Very often in recent times I have felt like that childhood dream has been belatedly realised – that I have become, if not anything like a full-blown vet, at least an acceptable apprentice. (My most damaged and troublesome dog Chameli has usually been the conduit for this.) And never has this feeling been more pronounced than in the past few days: no surprise when one is administering various sorts of medicines at regular intervals, cleaning deep and ugly wounds, and assisting in the removal of clusters of maggots from delicate places. My mother, who smiled proudly whenever I said “a vet” as a child, would have liked hearing about these adventures.

2) As I mentioned in that old post, Ravi was Kaali’s nemesis in 2015 – he was the one who took her to Friendicoes for her operation, she escaped from him and would bolt, snarling, every time she heard the sound of his car when he tried to find her. Now, five years later, their paths have crossed again in unexpected circumstances, and it feels like things have come full circle – it’s a tale that has redemption, grace, forgiveness, all those grand and inflated human themes. She has been terrified during the treatment, but there’s a more resigned, senior-citizen look in her eyes when she sees him, as if she’s saying, “Well, I can’t run away from you all my life, and there isn’t much life left now anyway, so let’s get on with this.” (Meanwhile, Ravi tells her elaborate stories in a steadily comforting voice even as he does the treatment: things like “Haan haan, Friendicoes mein woh Chhotu abhi bhi aapke baare mein poochte rahta hai – woh kahin phirse toh nahin bhaag gayi?”)

2) As I mentioned in that old post, Ravi was Kaali’s nemesis in 2015 – he was the one who took her to Friendicoes for her operation, she escaped from him and would bolt, snarling, every time she heard the sound of his car when he tried to find her. Now, five years later, their paths have crossed again in unexpected circumstances, and it feels like things have come full circle – it’s a tale that has redemption, grace, forgiveness, all those grand and inflated human themes. She has been terrified during the treatment, but there’s a more resigned, senior-citizen look in her eyes when she sees him, as if she’s saying, “Well, I can’t run away from you all my life, and there isn’t much life left now anyway, so let’s get on with this.” (Meanwhile, Ravi tells her elaborate stories in a steadily comforting voice even as he does the treatment: things like “Haan haan, Friendicoes mein woh Chhotu abhi bhi aapke baare mein poochte rahta hai – woh kahin phirse toh nahin bhaag gayi?”) Today, after we removed her muzzle and leash and set her free, I was surprised to see her walking back towards him and wagging her tail a bit, even though she had been shrieking in pain when her ears were being cleaned. Displays of trust like this make many of these situations seem worth the effort. [More about Ravi and Manoj and their efforts here]

Published on May 07, 2020 00:42

May 3, 2020

For Vimla Srivastava, in admiration

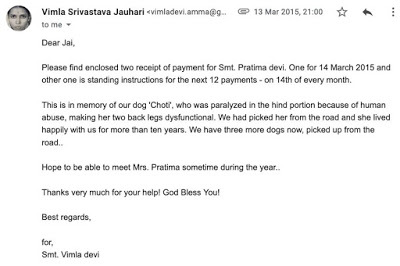

Had put this on Facebook around a month and a half ago, but wanted to share it here too. Shortly before the first of the lockdowns was imposed across India, I got news about the passing of someone whom I had never met and had only interacted with on email (a few brief exchanges over five years), but who I’m certain must have been a positive inspiration to thousands of people over her long lifetime. Vimla Srivastava Jauhari — teacher, humanitarian, animal-lover.

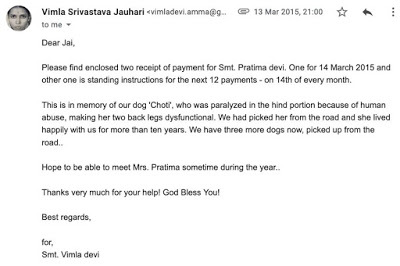

In March 2015 I received an email from Vimla ji: 83 years old, from Hardoi district, UP. She had read about Pratima Devi/Amma — the “dog mother” of PVR Anupam — on my blog, and wanted to know how she could contribute a small monthly amount for her. “I know that Delhi is a rich place and there must be financial help for Pratima Devi,” she wrote, “But I am a pensioner and can part with a fraction of it every month for her cause.”

In March 2015 I received an email from Vimla ji: 83 years old, from Hardoi district, UP. She had read about Pratima Devi/Amma — the “dog mother” of PVR Anupam — on my blog, and wanted to know how she could contribute a small monthly amount for her. “I know that Delhi is a rich place and there must be financial help for Pratima Devi,” she wrote, “But I am a pensioner and can part with a fraction of it every month for her cause.”

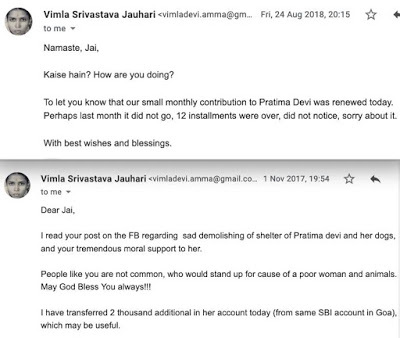

I sent Vimla ji the account details for Pratima Devi (remarkably, she thanked me for doing this!) — and starting that month, she arranged for a fixed amount to be transferred every month to the account. Most of our subsequent interactions were limited to her sending me yearly notifications that the transfers were continuing; I gave her updates about Pratima Devi and the dogs, sent photos. Once in a while, she would also send a general note, share a video link about environmental damage and so on. She followed my blog and Facebook posts occasionally, and asked how my mother was doing during the cancer treatment.

During one exchange, when I intended to write “Thank you for your continuing assistance”, I accidentally wrote “…for your continuing existence” instead. When I mailed to correct this, she replied:

“Your mail made me laugh...each healthy day (existence) granted by GOD after 80 is a blessing, no worries.”

Around a month and a half ago, I received a Facebook notification saying that Vimla Srivastava had passed away after a heart attack. I’m sure she will be missed and remembered by many people who knew her at much closer quarters, but I’m glad to have crossed paths with her, even if only in this distant way; though we never even spoke on the phone, it feels like a personal loss.

In March 2015 I received an email from Vimla ji: 83 years old, from Hardoi district, UP. She had read about Pratima Devi/Amma — the “dog mother” of PVR Anupam — on my blog, and wanted to know how she could contribute a small monthly amount for her. “I know that Delhi is a rich place and there must be financial help for Pratima Devi,” she wrote, “But I am a pensioner and can part with a fraction of it every month for her cause.”

In March 2015 I received an email from Vimla ji: 83 years old, from Hardoi district, UP. She had read about Pratima Devi/Amma — the “dog mother” of PVR Anupam — on my blog, and wanted to know how she could contribute a small monthly amount for her. “I know that Delhi is a rich place and there must be financial help for Pratima Devi,” she wrote, “But I am a pensioner and can part with a fraction of it every month for her cause.”I sent Vimla ji the account details for Pratima Devi (remarkably, she thanked me for doing this!) — and starting that month, she arranged for a fixed amount to be transferred every month to the account. Most of our subsequent interactions were limited to her sending me yearly notifications that the transfers were continuing; I gave her updates about Pratima Devi and the dogs, sent photos. Once in a while, she would also send a general note, share a video link about environmental damage and so on. She followed my blog and Facebook posts occasionally, and asked how my mother was doing during the cancer treatment.

During one exchange, when I intended to write “Thank you for your continuing assistance”, I accidentally wrote “…for your continuing existence” instead. When I mailed to correct this, she replied:

“Your mail made me laugh...each healthy day (existence) granted by GOD after 80 is a blessing, no worries.”

Around a month and a half ago, I received a Facebook notification saying that Vimla Srivastava had passed away after a heart attack. I’m sure she will be missed and remembered by many people who knew her at much closer quarters, but I’m glad to have crossed paths with her, even if only in this distant way; though we never even spoke on the phone, it feels like a personal loss.

Published on May 03, 2020 10:53

May 1, 2020

Lockdown film recommendation: Portrait of a Lady on Fire

[Continuing with film recos -- this one is on Mubi.com for only another week or so]

A familiar sinking feeling for an independent writer without a regular income source. You have deadlines for long essays that you’re carefully procrastinating on (note: these are not necessarily things you will get paid for, which makes the point about income irrelevant), you know you must get back to writing those pieces, or at least thinking about them, structuring them in your head etc… but then, at the end of a tiring day you take a break by watching a film, and you realise that you absolutely HAVE to write about this film (which no one will pay you to write about), and that this will take up a lot of time and mental energy.

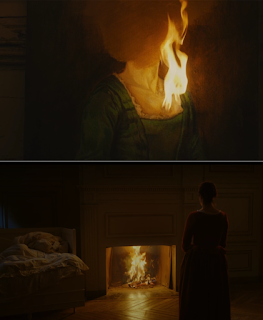

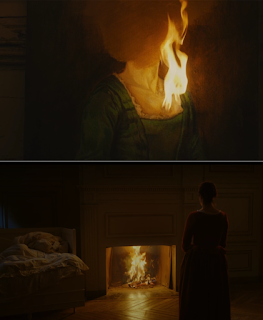

The latest of those films, and one of the best things I have watched in ages: Céline Sciamma’s stunningly shot and performed Portrait of a Lady on Fire, about a growing closeness between two women, an artist named Marianne and her subject Héloïse, in 18th century France. Loath as I am to make “recommendations”, I would unhesitatingly toss this film at anyone who doesn’t mind languid narratives where nothing very major seems to “happen” for stretches, where the emphasis is on the quiet gesture and the unarticulated emotion.

The latest of those films, and one of the best things I have watched in ages: Céline Sciamma’s stunningly shot and performed Portrait of a Lady on Fire, about a growing closeness between two women, an artist named Marianne and her subject Héloïse, in 18th century France. Loath as I am to make “recommendations”, I would unhesitatingly toss this film at anyone who doesn’t mind languid narratives where nothing very major seems to “happen” for stretches, where the emphasis is on the quiet gesture and the unarticulated emotion.

That said, this film didn’t feel slow at all while I was watching it. And it worked at many levels, many of which I haven’t fully processed. It is a beautifully developed romance set in a very particular place at a particular time. It is an examination of idealised vs practical versions of love, and of the misleading idea that it is the artist who is both in control and feels most deeply while the subject is a blank slate. And it makes intriguing use of the Orpheus-Eurydice story as a parable for women’s agency. (What if it were Eurydice who asked Orpheus to turn around and look at her on their way out of Hades, thus sealing her fate but also ensuring that she got to choose her destiny, to win a form of immortality rather than live a mundane, subservient life?)

But as much as anything else, I saw this as a sort of meta-film that contrasts two different forms, painting and cinema, and their treatment of the artist-subject relationship. This is made most obvious in the extraordinary final sequence (no spoiler here, I don’t think anything could spoil the effect of that scene), a nearly three-minute take where the face of the actress Adèle Haenel becomes as much of a muse for director Sciamma’s canvas as the character Héloïse was for Marianne in the story. (By the way, it was only after watching the film that I learnt that Sciamma and Haenel had been in a real-life relationship. No surprise. There is something very urgent and personal about that final sequence.)

But as much as anything else, I saw this as a sort of meta-film that contrasts two different forms, painting and cinema, and their treatment of the artist-subject relationship. This is made most obvious in the extraordinary final sequence (no spoiler here, I don’t think anything could spoil the effect of that scene), a nearly three-minute take where the face of the actress Adèle Haenel becomes as much of a muse for director Sciamma’s canvas as the character Héloïse was for Marianne in the story. (By the way, it was only after watching the film that I learnt that Sciamma and Haenel had been in a real-life relationship. No surprise. There is something very urgent and personal about that final sequence.)

I'll save a longer piece for later, maybe after a second viewing. This film is on Mubi, and will only be there for another week – so don’t waste time.

P.S. I don’t usually like making direct comparisons between two films, or sweeping proclamations about one being “better” than the other – especially when the films in question are both of high calibre and very different in texture, genre or style. Few exercises are so pointless or reductive. But I’m tempted for once to get into comparison territory, given that a film this good was a potential contender at the Oscars last year. And especially given some of the talk I heard about how Parasite was a masterwork that had, purely on merit, succeeded in doing something that decades of foreign-language films had not.

This is not intended as a putdown of Parasite (and I clarified some of my thoughts about the Oscars in this piece earlier) but as a comment on narratives about why this or that film “deserves” an award. One of the themes of Portrait of a Lady on Fire is how art created by women – or the women’s gaze more generally – has historically been neglected, patronised or treated as less important or less “universal” than male art. The fact that France didn’t choose this film as its official submission to the Oscars was not, I’d like to think, because it was perceived as “just a women’s picture” – as a period love story that didn’t deal with Big Subjects. But history suggests that could be the case. If Parasite broke (or appeared to break) one glass ceiling, others are comfortably intact.

This is not intended as a putdown of Parasite (and I clarified some of my thoughts about the Oscars in this piece earlier) but as a comment on narratives about why this or that film “deserves” an award. One of the themes of Portrait of a Lady on Fire is how art created by women – or the women’s gaze more generally – has historically been neglected, patronised or treated as less important or less “universal” than male art. The fact that France didn’t choose this film as its official submission to the Oscars was not, I’d like to think, because it was perceived as “just a women’s picture” – as a period love story that didn’t deal with Big Subjects. But history suggests that could be the case. If Parasite broke (or appeared to break) one glass ceiling, others are comfortably intact.

A familiar sinking feeling for an independent writer without a regular income source. You have deadlines for long essays that you’re carefully procrastinating on (note: these are not necessarily things you will get paid for, which makes the point about income irrelevant), you know you must get back to writing those pieces, or at least thinking about them, structuring them in your head etc… but then, at the end of a tiring day you take a break by watching a film, and you realise that you absolutely HAVE to write about this film (which no one will pay you to write about), and that this will take up a lot of time and mental energy.

The latest of those films, and one of the best things I have watched in ages: Céline Sciamma’s stunningly shot and performed Portrait of a Lady on Fire, about a growing closeness between two women, an artist named Marianne and her subject Héloïse, in 18th century France. Loath as I am to make “recommendations”, I would unhesitatingly toss this film at anyone who doesn’t mind languid narratives where nothing very major seems to “happen” for stretches, where the emphasis is on the quiet gesture and the unarticulated emotion.

The latest of those films, and one of the best things I have watched in ages: Céline Sciamma’s stunningly shot and performed Portrait of a Lady on Fire, about a growing closeness between two women, an artist named Marianne and her subject Héloïse, in 18th century France. Loath as I am to make “recommendations”, I would unhesitatingly toss this film at anyone who doesn’t mind languid narratives where nothing very major seems to “happen” for stretches, where the emphasis is on the quiet gesture and the unarticulated emotion.That said, this film didn’t feel slow at all while I was watching it. And it worked at many levels, many of which I haven’t fully processed. It is a beautifully developed romance set in a very particular place at a particular time. It is an examination of idealised vs practical versions of love, and of the misleading idea that it is the artist who is both in control and feels most deeply while the subject is a blank slate. And it makes intriguing use of the Orpheus-Eurydice story as a parable for women’s agency. (What if it were Eurydice who asked Orpheus to turn around and look at her on their way out of Hades, thus sealing her fate but also ensuring that she got to choose her destiny, to win a form of immortality rather than live a mundane, subservient life?)

But as much as anything else, I saw this as a sort of meta-film that contrasts two different forms, painting and cinema, and their treatment of the artist-subject relationship. This is made most obvious in the extraordinary final sequence (no spoiler here, I don’t think anything could spoil the effect of that scene), a nearly three-minute take where the face of the actress Adèle Haenel becomes as much of a muse for director Sciamma’s canvas as the character Héloïse was for Marianne in the story. (By the way, it was only after watching the film that I learnt that Sciamma and Haenel had been in a real-life relationship. No surprise. There is something very urgent and personal about that final sequence.)

But as much as anything else, I saw this as a sort of meta-film that contrasts two different forms, painting and cinema, and their treatment of the artist-subject relationship. This is made most obvious in the extraordinary final sequence (no spoiler here, I don’t think anything could spoil the effect of that scene), a nearly three-minute take where the face of the actress Adèle Haenel becomes as much of a muse for director Sciamma’s canvas as the character Héloïse was for Marianne in the story. (By the way, it was only after watching the film that I learnt that Sciamma and Haenel had been in a real-life relationship. No surprise. There is something very urgent and personal about that final sequence.)I'll save a longer piece for later, maybe after a second viewing. This film is on Mubi, and will only be there for another week – so don’t waste time.

P.S. I don’t usually like making direct comparisons between two films, or sweeping proclamations about one being “better” than the other – especially when the films in question are both of high calibre and very different in texture, genre or style. Few exercises are so pointless or reductive. But I’m tempted for once to get into comparison territory, given that a film this good was a potential contender at the Oscars last year. And especially given some of the talk I heard about how Parasite was a masterwork that had, purely on merit, succeeded in doing something that decades of foreign-language films had not.

This is not intended as a putdown of Parasite (and I clarified some of my thoughts about the Oscars in this piece earlier) but as a comment on narratives about why this or that film “deserves” an award. One of the themes of Portrait of a Lady on Fire is how art created by women – or the women’s gaze more generally – has historically been neglected, patronised or treated as less important or less “universal” than male art. The fact that France didn’t choose this film as its official submission to the Oscars was not, I’d like to think, because it was perceived as “just a women’s picture” – as a period love story that didn’t deal with Big Subjects. But history suggests that could be the case. If Parasite broke (or appeared to break) one glass ceiling, others are comfortably intact.

This is not intended as a putdown of Parasite (and I clarified some of my thoughts about the Oscars in this piece earlier) but as a comment on narratives about why this or that film “deserves” an award. One of the themes of Portrait of a Lady on Fire is how art created by women – or the women’s gaze more generally – has historically been neglected, patronised or treated as less important or less “universal” than male art. The fact that France didn’t choose this film as its official submission to the Oscars was not, I’d like to think, because it was perceived as “just a women’s picture” – as a period love story that didn’t deal with Big Subjects. But history suggests that could be the case. If Parasite broke (or appeared to break) one glass ceiling, others are comfortably intact.

Published on May 01, 2020 19:02

April 30, 2020

Rishi Kapoor, in memoriam

[I’m not overly fond of writing obituaries, and not just for the obvious reason. These things always have to be done on a tight deadline, which invariably means that within 15 minutes of sending the piece you recall eight other things you should definitely have mentioned. But Mint Lounge asked me to write something about Rishi Kapoor yesterday, so here it is]

-------------------

If you’re growing up in the 1980s, a boy in love with Hindi cinema’s macho heroes, you can be forgiven for being less than enamoured of Rishi Kapoor. Here he is, as the diminutive Akbar in one of your favourite films, singing qawwalis and being romantic and chirpy, while your “heroes” Anthony and Amar (in that order) do the manly things, swaggering and getting into fisticuffs and being funny-drunk. Years later, you will be better placed to appreciate the centrality of Akbar – bard, commenter, dispeller of veils – to this film, and the quiet, tempering charm of the actor playing him. But back then, you see him as a third wheel, much like the kid brother who will try to placate Bachchan with “Chal mere bhai” in Naseeb a few years later.

If you’re growing up in the 1980s, a boy in love with Hindi cinema’s macho heroes, you can be forgiven for being less than enamoured of Rishi Kapoor. Here he is, as the diminutive Akbar in one of your favourite films, singing qawwalis and being romantic and chirpy, while your “heroes” Anthony and Amar (in that order) do the manly things, swaggering and getting into fisticuffs and being funny-drunk. Years later, you will be better placed to appreciate the centrality of Akbar – bard, commenter, dispeller of veils – to this film, and the quiet, tempering charm of the actor playing him. But back then, you see him as a third wheel, much like the kid brother who will try to placate Bachchan with “Chal mere bhai” in Naseeb a few years later.

Near the end of the decade, the same actor again plays a music-loving pacifist in another of your favourite multi-starrers, JP Dutta’s Hathyar. In the climax, as Sanjay Dutt and Dharmendra go down blazing in a haze of bullets, it is Rishi Kapoor’s Sami Bhai who tries to pry guns away, to negotiate peace between gangsters and cops. This sort of thing can be unappealing if you want some good old dhishkiyaon-dhishkiyaon, but even in that mood there was a moment that stuck with me for decades.

Sami Bhai has just been beaten up and is offering no resistance. Clutching a pole, out of breath, seeing that his assailant is about to walk away, he makes a trio of wordless gestures (ranging from “come, take out more of your anger on me” to “what, you’re done already?”) – the whole thing takes up maybe three or four seconds, but it is as good an acting vignette as you’ll see.

Of course, Rishi Kapoor did so much in the 1970s and 1980s, across genres, that it was impossible not to sit up and take notice, even if he wasn’t your preferred hero type. Glancing through his filmography is to be reminded that he was an essential presence in many different types of films: from his effortlessly lithe musical performances in Karz and Hum Kisise Kam Nahin to one of his few truly offbeat films of that period, Rajinder Singh Bedi’s Ek Chaadar Maili Si, to the thriller Khoj, where he more than held his own against Naseeruddin Shah in an exciting verbal joust that builds to the climactic denouement.

Of course, Rishi Kapoor did so much in the 1970s and 1980s, across genres, that it was impossible not to sit up and take notice, even if he wasn’t your preferred hero type. Glancing through his filmography is to be reminded that he was an essential presence in many different types of films: from his effortlessly lithe musical performances in Karz and Hum Kisise Kam Nahin to one of his few truly offbeat films of that period, Rajinder Singh Bedi’s Ek Chaadar Maili Si, to the thriller Khoj, where he more than held his own against Naseeruddin Shah in an exciting verbal joust that builds to the climactic denouement.

Looking back on his work during that time, it’s interesting to consider how often he seems to be a silent or passive presence, or how often we see the character he plays in relation to someone else – from the boy watching his teacher, Simi Garewal, undressing by the lake in Mera Naam Joker, to the adult looking at Dimple Kapadia by the sea in Saagar. In both cases, and in so many others, watching or romancing dozens of heroines over the years, he came to represent a relatively unthreatening variant on the male gaze – shy, longing, even courtly. And he frequently played secondary parts in woman-centric films like Prem Rog and Tawaif, unafraid to be the not-always-likable man who must grow inwardly before he can take on responsibility. (In this, he is a clear precursor to the Ayushmann Khurana persona of the current age, even though today’s films are more politically correct and overtly progressive than most of the social dramas Rishi Kapoor did in the 80s.)

Self-effacement was one of the keys to this persona. If he seemed to melt into the background in multi-starrers where he worked with action heroes, this was equally often the case in the “social dramas” where the focus was on the women. (In Damini, he did both: playing second fiddle to Meenakshi Seshadri – as the film’s protagonist, a tireless upholder of truth and justice – and the red-eyed Sunny Deol as a lawyer who fights a woman’s cause with macho zest.) And yes, in later years, there were times when the self-effacement yielded to a form of showiness or peevishness: there are some boastful passages in his autobiography Khullam Khulla, such as the ones where he seems to take credit for “introducing” a number of female stars, or says that Bachchan always had the advantage of writers and directors kowtowing to him. But perhaps that sort of thing is a natural by-product of feeling neglected or hard done by in one’s prime.

Self-effacement was one of the keys to this persona. If he seemed to melt into the background in multi-starrers where he worked with action heroes, this was equally often the case in the “social dramas” where the focus was on the women. (In Damini, he did both: playing second fiddle to Meenakshi Seshadri – as the film’s protagonist, a tireless upholder of truth and justice – and the red-eyed Sunny Deol as a lawyer who fights a woman’s cause with macho zest.) And yes, in later years, there were times when the self-effacement yielded to a form of showiness or peevishness: there are some boastful passages in his autobiography Khullam Khulla, such as the ones where he seems to take credit for “introducing” a number of female stars, or says that Bachchan always had the advantage of writers and directors kowtowing to him. But perhaps that sort of thing is a natural by-product of feeling neglected or hard done by in one’s prime.

After a long gap in the 1990s and early 2000s, where he did little of note, Kapoor famously found a second innings, playing roles that his fan base of two decades earlier would have found it hard to imagine him in – from the pedantic movie producer in Luck by Chance to the sleazy Rauf Lala in the Agneepath remake, the middle-class Lajpat Nagar teacher in Do Dooni Chaar, or the Dawood Ibrahim-like gangster in D-Day, launching into a colourful monologue at the film’s end, and using an explosive profanity that one would never have expected from the Chintu baba of old. He also played a version of himself in the affectionate, under-watched Chintu-ji, which was a part-tribute to his father’s brand of filmmaking. And most recently, he was the beleaguered Muslim lawyer in Mulk, trying to clear his family of terrorism charges.

Dawood Ibrahim-like gangster in D-Day, launching into a colourful monologue at the film’s end, and using an explosive profanity that one would never have expected from the Chintu baba of old. He also played a version of himself in the affectionate, under-watched Chintu-ji, which was a part-tribute to his father’s brand of filmmaking. And most recently, he was the beleaguered Muslim lawyer in Mulk, trying to clear his family of terrorism charges.

These are all roles that permitted greater displays of versatility than the old Hindi cinema did, and in interviews and in his book Kapoor spoke about how he had waited for decades to be able to do such films. But while respecting the range he showed in his later years, I think any real appreciation of Rishi Kapoor the star-actor requires being able to marvel at the many quiet moments of magic he found within long-established templates. For a real tribute, you couldn’t do much better than to watch his many fine performances in song sequences like “Jeevan ke Har Mod Pe” or “Hoga Tum se Pyaara Kaun” or “Parda Hai Parda”, to see how an actor with integrity and a work ethic can enhance even formulaic-seeming situations.

[Some related earlier pieces: Hathyar, Chintu-ji, and one of RK’s most “unforgettable” 1980s films, Naseeb Apna Apna]

-------------------

If you’re growing up in the 1980s, a boy in love with Hindi cinema’s macho heroes, you can be forgiven for being less than enamoured of Rishi Kapoor. Here he is, as the diminutive Akbar in one of your favourite films, singing qawwalis and being romantic and chirpy, while your “heroes” Anthony and Amar (in that order) do the manly things, swaggering and getting into fisticuffs and being funny-drunk. Years later, you will be better placed to appreciate the centrality of Akbar – bard, commenter, dispeller of veils – to this film, and the quiet, tempering charm of the actor playing him. But back then, you see him as a third wheel, much like the kid brother who will try to placate Bachchan with “Chal mere bhai” in Naseeb a few years later.

If you’re growing up in the 1980s, a boy in love with Hindi cinema’s macho heroes, you can be forgiven for being less than enamoured of Rishi Kapoor. Here he is, as the diminutive Akbar in one of your favourite films, singing qawwalis and being romantic and chirpy, while your “heroes” Anthony and Amar (in that order) do the manly things, swaggering and getting into fisticuffs and being funny-drunk. Years later, you will be better placed to appreciate the centrality of Akbar – bard, commenter, dispeller of veils – to this film, and the quiet, tempering charm of the actor playing him. But back then, you see him as a third wheel, much like the kid brother who will try to placate Bachchan with “Chal mere bhai” in Naseeb a few years later. Near the end of the decade, the same actor again plays a music-loving pacifist in another of your favourite multi-starrers, JP Dutta’s Hathyar. In the climax, as Sanjay Dutt and Dharmendra go down blazing in a haze of bullets, it is Rishi Kapoor’s Sami Bhai who tries to pry guns away, to negotiate peace between gangsters and cops. This sort of thing can be unappealing if you want some good old dhishkiyaon-dhishkiyaon, but even in that mood there was a moment that stuck with me for decades.

Sami Bhai has just been beaten up and is offering no resistance. Clutching a pole, out of breath, seeing that his assailant is about to walk away, he makes a trio of wordless gestures (ranging from “come, take out more of your anger on me” to “what, you’re done already?”) – the whole thing takes up maybe three or four seconds, but it is as good an acting vignette as you’ll see.

Of course, Rishi Kapoor did so much in the 1970s and 1980s, across genres, that it was impossible not to sit up and take notice, even if he wasn’t your preferred hero type. Glancing through his filmography is to be reminded that he was an essential presence in many different types of films: from his effortlessly lithe musical performances in Karz and Hum Kisise Kam Nahin to one of his few truly offbeat films of that period, Rajinder Singh Bedi’s Ek Chaadar Maili Si, to the thriller Khoj, where he more than held his own against Naseeruddin Shah in an exciting verbal joust that builds to the climactic denouement.

Of course, Rishi Kapoor did so much in the 1970s and 1980s, across genres, that it was impossible not to sit up and take notice, even if he wasn’t your preferred hero type. Glancing through his filmography is to be reminded that he was an essential presence in many different types of films: from his effortlessly lithe musical performances in Karz and Hum Kisise Kam Nahin to one of his few truly offbeat films of that period, Rajinder Singh Bedi’s Ek Chaadar Maili Si, to the thriller Khoj, where he more than held his own against Naseeruddin Shah in an exciting verbal joust that builds to the climactic denouement. Looking back on his work during that time, it’s interesting to consider how often he seems to be a silent or passive presence, or how often we see the character he plays in relation to someone else – from the boy watching his teacher, Simi Garewal, undressing by the lake in Mera Naam Joker, to the adult looking at Dimple Kapadia by the sea in Saagar. In both cases, and in so many others, watching or romancing dozens of heroines over the years, he came to represent a relatively unthreatening variant on the male gaze – shy, longing, even courtly. And he frequently played secondary parts in woman-centric films like Prem Rog and Tawaif, unafraid to be the not-always-likable man who must grow inwardly before he can take on responsibility. (In this, he is a clear precursor to the Ayushmann Khurana persona of the current age, even though today’s films are more politically correct and overtly progressive than most of the social dramas Rishi Kapoor did in the 80s.)

Self-effacement was one of the keys to this persona. If he seemed to melt into the background in multi-starrers where he worked with action heroes, this was equally often the case in the “social dramas” where the focus was on the women. (In Damini, he did both: playing second fiddle to Meenakshi Seshadri – as the film’s protagonist, a tireless upholder of truth and justice – and the red-eyed Sunny Deol as a lawyer who fights a woman’s cause with macho zest.) And yes, in later years, there were times when the self-effacement yielded to a form of showiness or peevishness: there are some boastful passages in his autobiography Khullam Khulla, such as the ones where he seems to take credit for “introducing” a number of female stars, or says that Bachchan always had the advantage of writers and directors kowtowing to him. But perhaps that sort of thing is a natural by-product of feeling neglected or hard done by in one’s prime.

Self-effacement was one of the keys to this persona. If he seemed to melt into the background in multi-starrers where he worked with action heroes, this was equally often the case in the “social dramas” where the focus was on the women. (In Damini, he did both: playing second fiddle to Meenakshi Seshadri – as the film’s protagonist, a tireless upholder of truth and justice – and the red-eyed Sunny Deol as a lawyer who fights a woman’s cause with macho zest.) And yes, in later years, there were times when the self-effacement yielded to a form of showiness or peevishness: there are some boastful passages in his autobiography Khullam Khulla, such as the ones where he seems to take credit for “introducing” a number of female stars, or says that Bachchan always had the advantage of writers and directors kowtowing to him. But perhaps that sort of thing is a natural by-product of feeling neglected or hard done by in one’s prime. After a long gap in the 1990s and early 2000s, where he did little of note, Kapoor famously found a second innings, playing roles that his fan base of two decades earlier would have found it hard to imagine him in – from the pedantic movie producer in Luck by Chance to the sleazy Rauf Lala in the Agneepath remake, the middle-class Lajpat Nagar teacher in Do Dooni Chaar, or the

Dawood Ibrahim-like gangster in D-Day, launching into a colourful monologue at the film’s end, and using an explosive profanity that one would never have expected from the Chintu baba of old. He also played a version of himself in the affectionate, under-watched Chintu-ji, which was a part-tribute to his father’s brand of filmmaking. And most recently, he was the beleaguered Muslim lawyer in Mulk, trying to clear his family of terrorism charges.

Dawood Ibrahim-like gangster in D-Day, launching into a colourful monologue at the film’s end, and using an explosive profanity that one would never have expected from the Chintu baba of old. He also played a version of himself in the affectionate, under-watched Chintu-ji, which was a part-tribute to his father’s brand of filmmaking. And most recently, he was the beleaguered Muslim lawyer in Mulk, trying to clear his family of terrorism charges. These are all roles that permitted greater displays of versatility than the old Hindi cinema did, and in interviews and in his book Kapoor spoke about how he had waited for decades to be able to do such films. But while respecting the range he showed in his later years, I think any real appreciation of Rishi Kapoor the star-actor requires being able to marvel at the many quiet moments of magic he found within long-established templates. For a real tribute, you couldn’t do much better than to watch his many fine performances in song sequences like “Jeevan ke Har Mod Pe” or “Hoga Tum se Pyaara Kaun” or “Parda Hai Parda”, to see how an actor with integrity and a work ethic can enhance even formulaic-seeming situations.

[Some related earlier pieces: Hathyar, Chintu-ji, and one of RK’s most “unforgettable” 1980s films, Naseeb Apna Apna]

Published on April 30, 2020 19:04

April 29, 2020

Despatches from a room: The Daughter of Time and other ‘isolation novels’

[my First Post Bookshelves column – about stories set in confined spaces, where people rely on imagination to make sense of an inaccessible world]

-----------------

In these strange times, as some of us struggle to remember what the world outside looked like until a couple of months ago (or if it even existed the way we recall it), and as parents try to find new ways to keep their children active – while also trying to keep their own thoughts from falling into the abyss – I have been thinking of Emma Donoghue’s Booker-shortlisted novel Room.

Told in the voice of Jack, five years old as the book opens, this is a story about a boy living alone with his mother in a small room, which neither of them ever seems to leave. Naturally they keep themselves busy: play games, clean and cook, watch TV together (he believes the things he sees on the screen have nothing to do with their world). Since we readers are privy only to Jack’s very limited perspective, it takes a while for us to conjecture what is really going on here – why he thinks the room is a planet unto itself, and why it’s such a struggle for his mother to explain what Outside is like.

When I first read Room, I saw it as a very dark allegory for certain aspects of “normal” childhood, including a close relationship with a parent. As a fable about growing up, and the agoraphobic terror-excitement of preparing to meet a new world, it reminded me a bit of Michael Ondaatje’s wonderful The Cat’s Table, in which an 11-year-old boy makes a long ship journey from Sri Lanka to England in the 1950s. Needless to say, this ship is much larger than the Room that Jack and his mother occupy, and there are colourful characters, friends, little adventures on board; but it is still a circumscribed space where the protagonist learns about himself, what lies beyond the world he has so far known, and what might happen when he gets there.

There is no dearth of other stories set in confined spaces, involving people who are isolated in one way or another. (Obligatory pedantic reminder: one doesn’t need to be physically isolated or quarantined to feel “alone” – people can be achingly lonely or cut off in crowds too.) There are books where a character, adrift, must use fantasy to nourish or save himself – as do the titular characters in Yann Martel’s Life of Pi or Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. There are more forthright meetings between fantasy and madness, as in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s brilliant short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper”, about a woman growing obsessed with the wallpaper in a room where she may or may not have been imprisoned: here is a seemingly bleak tale that also offers a form of hope and validation – a sense that a screen (or paper covering) has been ripped apart, and new possibilities revealed for women who are being bullied or oppressed by men.

There is no dearth of other stories set in confined spaces, involving people who are isolated in one way or another. (Obligatory pedantic reminder: one doesn’t need to be physically isolated or quarantined to feel “alone” – people can be achingly lonely or cut off in crowds too.) There are books where a character, adrift, must use fantasy to nourish or save himself – as do the titular characters in Yann Martel’s Life of Pi or Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. There are more forthright meetings between fantasy and madness, as in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s brilliant short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper”, about a woman growing obsessed with the wallpaper in a room where she may or may not have been imprisoned: here is a seemingly bleak tale that also offers a form of hope and validation – a sense that a screen (or paper covering) has been ripped apart, and new possibilities revealed for women who are being bullied or oppressed by men.

And there are doomsday books about things comparable to our current real-world situation: such as the passages in Max Brooks’s massively entertaining zombie apocalypse novel World War Z where privileged people discover that however carefully they build their fortresses and stock their provisions, they can’t stay forever untouched by a raging plague – something that was also the central theme of Edgar Allan Poe’s iconic “The Masque of the Red Death”.

On a lighter note, a very enjoyable “isolation novel” I recently read was Josephine Tey's 1951 mystery The Daughter of Time, in which Tey’s series detective, Inspector Alan Grant, finds himself bedridden in hospital, restless, with little to occupy his mind. This changes when a glimpse of a portrait of King Richard III leads Grant into a cerebral investigation of the man regarded as one of history’s major villains, famously caricatured by Shakespeare (Laurence Olivier’s celebrated stage performance as a very malevolent Richard was fresh in the public memory when this book was written) and denounced by generations of historians. What was the truth, Grant wonders, behind the disappearance of Richard’s two little nephews, and was there an injustice done to his reputation?

On a lighter note, a very enjoyable “isolation novel” I recently read was Josephine Tey's 1951 mystery The Daughter of Time, in which Tey’s series detective, Inspector Alan Grant, finds himself bedridden in hospital, restless, with little to occupy his mind. This changes when a glimpse of a portrait of King Richard III leads Grant into a cerebral investigation of the man regarded as one of history’s major villains, famously caricatured by Shakespeare (Laurence Olivier’s celebrated stage performance as a very malevolent Richard was fresh in the public memory when this book was written) and denounced by generations of historians. What was the truth, Grant wonders, behind the disappearance of Richard’s two little nephews, and was there an injustice done to his reputation?

What makes this such a compelling and unusual murder mystery is that we never leave Grant’s hospital room. He isn’t exactly alone – nurses fuss over him, occasional visitors bring him books and indulge his theories, a young scholar plays apprentice and researcher – but this is in essence a very interior book, as far as one can get from a detective story involving action and legwork.

To fully enjoy this dissection of very distant history, you probably need basic interest in the period (it’s useful to have Wikipedia at hand to read up on the litany of royals with similar names). But I think there is much of general interest here as well — not least in the way Tey takes a scalpel to how history tends to be written and set in stone; how a single chronicler’s bias or ulterior motive, or even carelessness, can create a domino effect that echoes through the centuries, creating unshakable narratives and impressions for future generations. And, of course, how a great playwright and the actors who bring his work alive can contribute to solidifying those impressions.

So, was Richard III (to misquote Shakespeare) cheated of feature by dissembling historians? This has apparently been a widely debated question, but Josephine Tey helped bring the debate to a large public through this accessible, fast-paced genre work.

On the face of it, there is little in common between a Room and a Daughter of Time. One is an often morbid narrative about two people who are victims of a horrible crime (with one of them not even aware of it), while the other is a breezy historical mystery that investigates diabolical events but still manages to be a droll, comforting read (even the most dastardly villains here have been dead for centuries and pose no threat to Inspector Grant). But both books, and some of the others mentioned here, are about immobilised people in an unnatural situation, using what resources they have to stay productive and to find a form of escape: whether it involves traveling into the past, moving towards physical freedom, or re-evaluating the mechanics of an outside world that is temporarily out of reach.

P.S. more on Shakespeare's Richard III. From Donald Spoto’s Olivier biography:

P.S. more on Shakespeare's Richard III. From Donald Spoto’s Olivier biography:

[More about Emma Donoghue's Room in this personal essay about my mother. Here is a post about World War Z. And a longer post about Ondaatje's The Cat's Table is here]

-----------------

In these strange times, as some of us struggle to remember what the world outside looked like until a couple of months ago (or if it even existed the way we recall it), and as parents try to find new ways to keep their children active – while also trying to keep their own thoughts from falling into the abyss – I have been thinking of Emma Donoghue’s Booker-shortlisted novel Room.

Told in the voice of Jack, five years old as the book opens, this is a story about a boy living alone with his mother in a small room, which neither of them ever seems to leave. Naturally they keep themselves busy: play games, clean and cook, watch TV together (he believes the things he sees on the screen have nothing to do with their world). Since we readers are privy only to Jack’s very limited perspective, it takes a while for us to conjecture what is really going on here – why he thinks the room is a planet unto itself, and why it’s such a struggle for his mother to explain what Outside is like.

When I first read Room, I saw it as a very dark allegory for certain aspects of “normal” childhood, including a close relationship with a parent. As a fable about growing up, and the agoraphobic terror-excitement of preparing to meet a new world, it reminded me a bit of Michael Ondaatje’s wonderful The Cat’s Table, in which an 11-year-old boy makes a long ship journey from Sri Lanka to England in the 1950s. Needless to say, this ship is much larger than the Room that Jack and his mother occupy, and there are colourful characters, friends, little adventures on board; but it is still a circumscribed space where the protagonist learns about himself, what lies beyond the world he has so far known, and what might happen when he gets there.

There is no dearth of other stories set in confined spaces, involving people who are isolated in one way or another. (Obligatory pedantic reminder: one doesn’t need to be physically isolated or quarantined to feel “alone” – people can be achingly lonely or cut off in crowds too.) There are books where a character, adrift, must use fantasy to nourish or save himself – as do the titular characters in Yann Martel’s Life of Pi or Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. There are more forthright meetings between fantasy and madness, as in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s brilliant short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper”, about a woman growing obsessed with the wallpaper in a room where she may or may not have been imprisoned: here is a seemingly bleak tale that also offers a form of hope and validation – a sense that a screen (or paper covering) has been ripped apart, and new possibilities revealed for women who are being bullied or oppressed by men.

There is no dearth of other stories set in confined spaces, involving people who are isolated in one way or another. (Obligatory pedantic reminder: one doesn’t need to be physically isolated or quarantined to feel “alone” – people can be achingly lonely or cut off in crowds too.) There are books where a character, adrift, must use fantasy to nourish or save himself – as do the titular characters in Yann Martel’s Life of Pi or Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. There are more forthright meetings between fantasy and madness, as in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s brilliant short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper”, about a woman growing obsessed with the wallpaper in a room where she may or may not have been imprisoned: here is a seemingly bleak tale that also offers a form of hope and validation – a sense that a screen (or paper covering) has been ripped apart, and new possibilities revealed for women who are being bullied or oppressed by men.And there are doomsday books about things comparable to our current real-world situation: such as the passages in Max Brooks’s massively entertaining zombie apocalypse novel World War Z where privileged people discover that however carefully they build their fortresses and stock their provisions, they can’t stay forever untouched by a raging plague – something that was also the central theme of Edgar Allan Poe’s iconic “The Masque of the Red Death”.

On a lighter note, a very enjoyable “isolation novel” I recently read was Josephine Tey's 1951 mystery The Daughter of Time, in which Tey’s series detective, Inspector Alan Grant, finds himself bedridden in hospital, restless, with little to occupy his mind. This changes when a glimpse of a portrait of King Richard III leads Grant into a cerebral investigation of the man regarded as one of history’s major villains, famously caricatured by Shakespeare (Laurence Olivier’s celebrated stage performance as a very malevolent Richard was fresh in the public memory when this book was written) and denounced by generations of historians. What was the truth, Grant wonders, behind the disappearance of Richard’s two little nephews, and was there an injustice done to his reputation?

On a lighter note, a very enjoyable “isolation novel” I recently read was Josephine Tey's 1951 mystery The Daughter of Time, in which Tey’s series detective, Inspector Alan Grant, finds himself bedridden in hospital, restless, with little to occupy his mind. This changes when a glimpse of a portrait of King Richard III leads Grant into a cerebral investigation of the man regarded as one of history’s major villains, famously caricatured by Shakespeare (Laurence Olivier’s celebrated stage performance as a very malevolent Richard was fresh in the public memory when this book was written) and denounced by generations of historians. What was the truth, Grant wonders, behind the disappearance of Richard’s two little nephews, and was there an injustice done to his reputation?What makes this such a compelling and unusual murder mystery is that we never leave Grant’s hospital room. He isn’t exactly alone – nurses fuss over him, occasional visitors bring him books and indulge his theories, a young scholar plays apprentice and researcher – but this is in essence a very interior book, as far as one can get from a detective story involving action and legwork.

To fully enjoy this dissection of very distant history, you probably need basic interest in the period (it’s useful to have Wikipedia at hand to read up on the litany of royals with similar names). But I think there is much of general interest here as well — not least in the way Tey takes a scalpel to how history tends to be written and set in stone; how a single chronicler’s bias or ulterior motive, or even carelessness, can create a domino effect that echoes through the centuries, creating unshakable narratives and impressions for future generations. And, of course, how a great playwright and the actors who bring his work alive can contribute to solidifying those impressions.

So, was Richard III (to misquote Shakespeare) cheated of feature by dissembling historians? This has apparently been a widely debated question, but Josephine Tey helped bring the debate to a large public through this accessible, fast-paced genre work.