Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 28

December 19, 2019

Short review – F-Rated: Being a Woman Filmmaker in India

[For various reasons – fatigue and poor health among them – I have had to cut down on regular writing and am rethinking my areas of focus as well as my work schedule. I will still try to put up the smallish pieces I do for various publications, such as this very basic, 400-word review for India Today. Such pieces don’t give me as much satisfaction as the longer, more in-depth ones do, but there is space for everything, I guess]

--------------------------

To say that women’s contributions to cinema have long been neglected – starting with early filmmakers like Dorothy Arzner and major editors such as Elizaveta Svilova (whose genius is visible in every frame of the astonishing silent film Man With a Movie Camera) – would be to greatly understate things. Nandita Dutta’s F-Rated, comprising interviews with and profiles of important Indian filmmakers, from veterans Aparna Sen and Mira Nair to Alankrita Srivastava and Nandita Das, is an attempt to redress the balance. This book is about the preferred themes and working styles of these artists, about the challenges they face as they balance profession with home life or the demands of parenthood – or cope with extra scrutiny, condescension and even sexual harassment.

To say that women’s contributions to cinema have long been neglected – starting with early filmmakers like Dorothy Arzner and major editors such as Elizaveta Svilova (whose genius is visible in every frame of the astonishing silent film Man With a Movie Camera) – would be to greatly understate things. Nandita Dutta’s F-Rated, comprising interviews with and profiles of important Indian filmmakers, from veterans Aparna Sen and Mira Nair to Alankrita Srivastava and Nandita Das, is an attempt to redress the balance. This book is about the preferred themes and working styles of these artists, about the challenges they face as they balance profession with home life or the demands of parenthood – or cope with extra scrutiny, condescension and even sexual harassment.

The result is a wide-ranging publication that tells individual stories while also probing cinematic tropes, trends and viewer demographics: for example, Dutta discusses the much-maligned “item number” and the difference between the sequence that focuses on the performer as a sentient person (as in “Kajra Re”) versus the one that treats the woman purely as object. Some anecdotes reminded me of the depiction of 1950s Hollywood in the recent TV series Feud, about the Joan Crawford-Bette Davis rivalry set in (and cynically encouraged by) a very male world; as this book points out, so much of film history – and film criticism and scholarship for that matter – comes filtered through a male lens, a perspective that often became the accepted norm.

The author’s own biases towards “understated” (as opposed to popular or commercial) cinema does lead to some simplistic analysis, as in a description of Tanuja Chandra’s clash with a New York producer who demanded she tone down a scene involving a bereaved mother. But it also makes the book more intriguing in parts, as in the Farah Khan chapter – here is someone who makes flashy, big-budget films and doesn’t fit easy notions about the sensitive, personal filmmaking one might expect from a woman director. Dutta’s ambivalence about this comes across – it's fairly clear that she doesn't much care for the sorts of films Khan specialises in – though she acknowledges the hurdles that even someone of this stature and popularity had to cross.

One does miss a few obvious names, like Zoya Akhtar, who is briefly touched on in the Reema Kagti chapter, but then this wasn’t intended to be a comprehensive study. Also, some filmmakers refrained from participating because they didn’t care to be restricted by the label “woman director” – even though they have faced discrimination because of their gender. Among other things, then, this book is a reminder of the limitations and the unavoidability of categorisation when it comes to assessing the work of women in a male-dominated space.

---------------

[A little more about that Tanuja Chandra profile in this earlier post]

--------------------------

To say that women’s contributions to cinema have long been neglected – starting with early filmmakers like Dorothy Arzner and major editors such as Elizaveta Svilova (whose genius is visible in every frame of the astonishing silent film Man With a Movie Camera) – would be to greatly understate things. Nandita Dutta’s F-Rated, comprising interviews with and profiles of important Indian filmmakers, from veterans Aparna Sen and Mira Nair to Alankrita Srivastava and Nandita Das, is an attempt to redress the balance. This book is about the preferred themes and working styles of these artists, about the challenges they face as they balance profession with home life or the demands of parenthood – or cope with extra scrutiny, condescension and even sexual harassment.

To say that women’s contributions to cinema have long been neglected – starting with early filmmakers like Dorothy Arzner and major editors such as Elizaveta Svilova (whose genius is visible in every frame of the astonishing silent film Man With a Movie Camera) – would be to greatly understate things. Nandita Dutta’s F-Rated, comprising interviews with and profiles of important Indian filmmakers, from veterans Aparna Sen and Mira Nair to Alankrita Srivastava and Nandita Das, is an attempt to redress the balance. This book is about the preferred themes and working styles of these artists, about the challenges they face as they balance profession with home life or the demands of parenthood – or cope with extra scrutiny, condescension and even sexual harassment. The result is a wide-ranging publication that tells individual stories while also probing cinematic tropes, trends and viewer demographics: for example, Dutta discusses the much-maligned “item number” and the difference between the sequence that focuses on the performer as a sentient person (as in “Kajra Re”) versus the one that treats the woman purely as object. Some anecdotes reminded me of the depiction of 1950s Hollywood in the recent TV series Feud, about the Joan Crawford-Bette Davis rivalry set in (and cynically encouraged by) a very male world; as this book points out, so much of film history – and film criticism and scholarship for that matter – comes filtered through a male lens, a perspective that often became the accepted norm.

The author’s own biases towards “understated” (as opposed to popular or commercial) cinema does lead to some simplistic analysis, as in a description of Tanuja Chandra’s clash with a New York producer who demanded she tone down a scene involving a bereaved mother. But it also makes the book more intriguing in parts, as in the Farah Khan chapter – here is someone who makes flashy, big-budget films and doesn’t fit easy notions about the sensitive, personal filmmaking one might expect from a woman director. Dutta’s ambivalence about this comes across – it's fairly clear that she doesn't much care for the sorts of films Khan specialises in – though she acknowledges the hurdles that even someone of this stature and popularity had to cross.

One does miss a few obvious names, like Zoya Akhtar, who is briefly touched on in the Reema Kagti chapter, but then this wasn’t intended to be a comprehensive study. Also, some filmmakers refrained from participating because they didn’t care to be restricted by the label “woman director” – even though they have faced discrimination because of their gender. Among other things, then, this book is a reminder of the limitations and the unavoidability of categorisation when it comes to assessing the work of women in a male-dominated space.

---------------

[A little more about that Tanuja Chandra profile in this earlier post]

Published on December 19, 2019 22:36

December 15, 2019

Agni Sreedhar and The Gangster’s Gita: the hitman as philosopher

(My latest Bookshelves column for First Post -- about a book by a "writer, editor and former gangster")

---------------------------

During a 2006 interview about his mammoth Bombay-underworld novel Sacred Games, Vikram Chandra told me that many of the real-world hitmen and gangsters he met during his research were deeply religious or philosophical, trying to structure their lives around core values. When Chandra wondered aloud how it was possible for such a person to put a bullet through the head of someone they didn’t even know, one gangster replied: "Upar wale ne uski maut likhi hai aur mera role hai usko maut dena. Main toh naatak mein apna role ada kar raha hoon." ("God has decided he has to die and my role is to bring him Death. So I'm just playing my part in a grand drama.")

That conversation, and Sacred Games’s depiction of the stoicism and banality of underworld lives (Ganesh Gaitonde casually mentions hacking an informer to pieces, returning home, eating “a little sabudane ki khichdi” and going to bed), came back to me while reading Agni Sreedhar’s The Gangster’s Gita. This slim book was first published in Kannada as Edegarike in 2004, made into an acclaimed film a few years later, and now we have a new English translation by Pratibha Nandakumar, who provides some context in her introduction.

That conversation, and Sacred Games’s depiction of the stoicism and banality of underworld lives (Ganesh Gaitonde casually mentions hacking an informer to pieces, returning home, eating “a little sabudane ki khichdi” and going to bed), came back to me while reading Agni Sreedhar’s The Gangster’s Gita. This slim book was first published in Kannada as Edegarike in 2004, made into an acclaimed film a few years later, and now we have a new English translation by Pratibha Nandakumar, who provides some context in her introduction.

Sreedhar’s life story makes for fascinating reading: he is a writer, publisher and critic, but also a former gangster who has written about his experiences in the underworld – notably in his autobiography Dadagiriya Dinagalu, which won a Sahitya Akademi award. The Gangster’s Gita is officially a work of fiction, but the almost documentary-like quietness of its telling and the nature of its story and principal relationship (not to mention that the narrator is named Sreedhar) leaves little doubt that it’s rooted in real-life experience.

This strange, compelling work hinges on Sreedhar being tasked to execute another hitman named Sona. It has to be done discreetly, of course – Sreedhar, his boss and a few of their men have to escort Sona from Bangalore to an isolated spot in Sakleshpur, where it will be easy to dispose of the body without attracting attention. But if this premise sounds like it has the makings of an exciting spy-vs-spy tale, that isn’t how it plays out. This book centres on a series of conversations between the two main characters. It portrays the mundaneness of a situation that most of us, from the outside, would not think of as mundane at all.

There have been many gripping stories involving bad guys in a verbal joust, moving between banter and philosophy, playing cat and mouse with each other – but those mostly tend to fall in the suspense or thriller genres; one expects twists, some action, a double-bluff or two. A few weeks ago I reread Jeffery Deaver’s fine story “The Weekender”, in which two men talk about souls and consciences and religion before indulging in a seemingly foolhardy test of faith, with the possibility of betrayal always on the table. Who will have the last laugh, is the question that runs through that story – and how will it come about?

The Gangster’s Gita is a very different narrative, not constructed around suspense as conventionally defined. There are little moments that appear to promise something exciting to come: an attempt by Sreedhar and his boss to get away from a police patrol on the road, for instance. But for the most part there is very little action, and a lot of waiting patiently for the right time. At one point, news comes that Sreedhar’s boss has been injured, and everyone gets worked up – until it turns out that what happened wasn’t an attack but something much more commonplace.

However, there is a different, subtler sort of suspense at play here: in the little detours and delays before the killing of Sona, which make Sreedhar more uncertain, even reluctant, about the task ahead of him; and in the insights we get into changes that may occur in the hearts of men inured to a particular way of life.

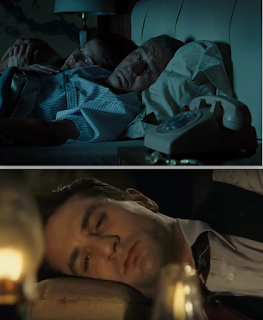

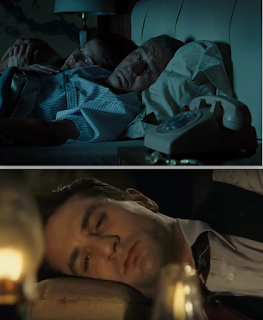

Around the same time that I read this book, I watched Martin Scorsese’s plaintive new film about the demythologising of the world of criminals and hitmen. The Irishman shows us underworld figures (played by Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, whose long acting careers have contributed so much to our ideas about what gangsters look and behave like) sitting around in their pajamas, looking weary; in its final scenes we see a former gangster, aged and creaky, missing teeth, unable to even bite into a piece of dry bread.

The Gangster’s Gita is a similarly deglamorised, pared-down story about a hitman who knows he is doomed, but is stoical about it – and more willing and able to confront the situation, to talk openly about it and to live in the moment, than his to-be assassins are. To the extent that Sreedhar is disoriented by Sona’s behaviour: “I began to get slightly irritated. I could not figure out if it was because he was talking like a philosopher or because I was helpless even as he was talking about us killing him in cold blood.”

Sona tells Sreedhar stories – fragments of stories – from his life, leaving some things unsaid or partly said. He philosophises, expresses regret about some of his actions, and in the end, makes a request. And Sreedhar himself, in turn, reflects (though mainly to himself) about encounters with destiny and how different types of people (or different types of cats!) deal with it: do you try to escape the inevitable, or calmly walk into its embrace?

Attempting to find some clarity about the situation, he recalls Albert Camus’s existential work The Outsider, as well as the automaton-like mindset of Nazi soldiers who had been given orders to carry out unthinkable crimes. His own feelings shift from shame to contempt to scepticism, sometimes all at the same time. And all of it leads up to an ending that has a quiet, lingering sense of mystery and wonder. While this is an unusual underworld story, it is also in an important sense an inner-world story about two people – assassin and victim, or student and master? – briefly orbiting each other.

[Earlier Bookshelves columns are here]

---------------------------

During a 2006 interview about his mammoth Bombay-underworld novel Sacred Games, Vikram Chandra told me that many of the real-world hitmen and gangsters he met during his research were deeply religious or philosophical, trying to structure their lives around core values. When Chandra wondered aloud how it was possible for such a person to put a bullet through the head of someone they didn’t even know, one gangster replied: "Upar wale ne uski maut likhi hai aur mera role hai usko maut dena. Main toh naatak mein apna role ada kar raha hoon." ("God has decided he has to die and my role is to bring him Death. So I'm just playing my part in a grand drama.")

That conversation, and Sacred Games’s depiction of the stoicism and banality of underworld lives (Ganesh Gaitonde casually mentions hacking an informer to pieces, returning home, eating “a little sabudane ki khichdi” and going to bed), came back to me while reading Agni Sreedhar’s The Gangster’s Gita. This slim book was first published in Kannada as Edegarike in 2004, made into an acclaimed film a few years later, and now we have a new English translation by Pratibha Nandakumar, who provides some context in her introduction.

That conversation, and Sacred Games’s depiction of the stoicism and banality of underworld lives (Ganesh Gaitonde casually mentions hacking an informer to pieces, returning home, eating “a little sabudane ki khichdi” and going to bed), came back to me while reading Agni Sreedhar’s The Gangster’s Gita. This slim book was first published in Kannada as Edegarike in 2004, made into an acclaimed film a few years later, and now we have a new English translation by Pratibha Nandakumar, who provides some context in her introduction. Sreedhar’s life story makes for fascinating reading: he is a writer, publisher and critic, but also a former gangster who has written about his experiences in the underworld – notably in his autobiography Dadagiriya Dinagalu, which won a Sahitya Akademi award. The Gangster’s Gita is officially a work of fiction, but the almost documentary-like quietness of its telling and the nature of its story and principal relationship (not to mention that the narrator is named Sreedhar) leaves little doubt that it’s rooted in real-life experience.

This strange, compelling work hinges on Sreedhar being tasked to execute another hitman named Sona. It has to be done discreetly, of course – Sreedhar, his boss and a few of their men have to escort Sona from Bangalore to an isolated spot in Sakleshpur, where it will be easy to dispose of the body without attracting attention. But if this premise sounds like it has the makings of an exciting spy-vs-spy tale, that isn’t how it plays out. This book centres on a series of conversations between the two main characters. It portrays the mundaneness of a situation that most of us, from the outside, would not think of as mundane at all.

There have been many gripping stories involving bad guys in a verbal joust, moving between banter and philosophy, playing cat and mouse with each other – but those mostly tend to fall in the suspense or thriller genres; one expects twists, some action, a double-bluff or two. A few weeks ago I reread Jeffery Deaver’s fine story “The Weekender”, in which two men talk about souls and consciences and religion before indulging in a seemingly foolhardy test of faith, with the possibility of betrayal always on the table. Who will have the last laugh, is the question that runs through that story – and how will it come about?

The Gangster’s Gita is a very different narrative, not constructed around suspense as conventionally defined. There are little moments that appear to promise something exciting to come: an attempt by Sreedhar and his boss to get away from a police patrol on the road, for instance. But for the most part there is very little action, and a lot of waiting patiently for the right time. At one point, news comes that Sreedhar’s boss has been injured, and everyone gets worked up – until it turns out that what happened wasn’t an attack but something much more commonplace.

However, there is a different, subtler sort of suspense at play here: in the little detours and delays before the killing of Sona, which make Sreedhar more uncertain, even reluctant, about the task ahead of him; and in the insights we get into changes that may occur in the hearts of men inured to a particular way of life.

Around the same time that I read this book, I watched Martin Scorsese’s plaintive new film about the demythologising of the world of criminals and hitmen. The Irishman shows us underworld figures (played by Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, whose long acting careers have contributed so much to our ideas about what gangsters look and behave like) sitting around in their pajamas, looking weary; in its final scenes we see a former gangster, aged and creaky, missing teeth, unable to even bite into a piece of dry bread.

The Gangster’s Gita is a similarly deglamorised, pared-down story about a hitman who knows he is doomed, but is stoical about it – and more willing and able to confront the situation, to talk openly about it and to live in the moment, than his to-be assassins are. To the extent that Sreedhar is disoriented by Sona’s behaviour: “I began to get slightly irritated. I could not figure out if it was because he was talking like a philosopher or because I was helpless even as he was talking about us killing him in cold blood.”

Sona tells Sreedhar stories – fragments of stories – from his life, leaving some things unsaid or partly said. He philosophises, expresses regret about some of his actions, and in the end, makes a request. And Sreedhar himself, in turn, reflects (though mainly to himself) about encounters with destiny and how different types of people (or different types of cats!) deal with it: do you try to escape the inevitable, or calmly walk into its embrace?

Attempting to find some clarity about the situation, he recalls Albert Camus’s existential work The Outsider, as well as the automaton-like mindset of Nazi soldiers who had been given orders to carry out unthinkable crimes. His own feelings shift from shame to contempt to scepticism, sometimes all at the same time. And all of it leads up to an ending that has a quiet, lingering sense of mystery and wonder. While this is an unusual underworld story, it is also in an important sense an inner-world story about two people – assassin and victim, or student and master? – briefly orbiting each other.

[Earlier Bookshelves columns are here]

Published on December 15, 2019 02:06

December 13, 2019

Lonely men, behind doors – in The Irishman and The Searchers

[My latest “moments” column for The Hindu]

---------------

In the final scene of Martin Scorsese’s epic The Irishman (onscreen title I Heard You Paint Houses), Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro) sits old and alone in a nursing home; it’s Christmas, but he has nothing to celebrate and no one to celebrate it with. Frank has asked that his room door be left ajar, and the film’s last shot has the camera outside, watching him through the half-open door.

In the final scene of Martin Scorsese’s epic The Irishman (onscreen title I Heard You Paint Houses), Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro) sits old and alone in a nursing home; it’s Christmas, but he has nothing to celebrate and no one to celebrate it with. Frank has asked that his room door be left ajar, and the film’s last shot has the camera outside, watching him through the half-open door.

The shot worked for me on multiple levels. For one, it’s as intimate and poignant as (though more static than) the closing shot of Scorsese’s previous feature Silence where we glimpse something of a man’s inner life after he has died – a Jesuit priest who renounced his religion but has a tiny cross in his hand as he is being cremated. Like Rodrigues in that film, Frank gave up something too, and we can’t say for certain how much he regrets it. And he is bearing a (different sort of) cross.

a man’s inner life after he has died – a Jesuit priest who renounced his religion but has a tiny cross in his hand as he is being cremated. Like Rodrigues in that film, Frank gave up something too, and we can’t say for certain how much he regrets it. And he is bearing a (different sort of) cross.

The Irishman scene also calls back to a mysterious moment earlier in the film where, shortly after Frank begins working for the powerful union leader Jimmy Hoffa, he spends a night in Hoffa’s suite – and sees that his boss has left the door to his own room partly open. This could be a personality tic, or a sign of trust, or a pointer to their future friendship. But for Frank, it also represents an entry point to another world. He goes from living a truck-driver’s itinerant life – spending time on the road, away from family for long stretches – to finding a sense of belonging and identity in a new community.

It’s a set-up in some ways, though, and will eventually lead to (moral and physical) desolation. At what should be the hour of Frank’s big triumph – a banquet in his honour, well-attended by people whom he looks up to – he also gets ominous signs that he may soon have to pick sides against a friend. And this leads to his ultimate fate as a lonely old man trying to maintain some connection with a world that has passed him by: entombed, cut off from everyone – most notably from his daughter Peggy who might have served as his conscience.

That closing scene also reminds me of other movie characters who have isolated themselves – from civilisation, from their families, or even from themselves. And other doors in which such people are framed so that only we can see them. The most prominent such scene is from a work that Scorsese (part of a generation of American directors who were first movie nerds) was deeply influenced by as a youngster – a film made, as it happens, by an Irishman: John Ford’s The Searchers.

The protagonist of that film, Ethan Edwards (played by John Wayne), is one of cinema’s loneliest men, someone who is a wanderer to begin with but who, at the beginning of the story, at least has a family of sorts. When this family is massacred in an Indian attack, Ethan embarks on revenge but starts to lose his moral compass along the way – even coming close to killing his niece who had been abducted as a child.

Eventually order is restored and there is an ostensibly “happy” ending – but not for Ethan, who is too far steeped in blood and madness, and knows it. If the film began with a door opening and Ethan riding towards his brother’s house from a distance – being welcomed into a home – it ends with him framed by another door, which then closes on him as he walks away. And in between these two scenes, there is another crucial shot of Ethan silhouetted in an entryway, bent in grief, neither inside nor outside.

Eventually order is restored and there is an ostensibly “happy” ending – but not for Ethan, who is too far steeped in blood and madness, and knows it. If the film began with a door opening and Ethan riding towards his brother’s house from a distance – being welcomed into a home – it ends with him framed by another door, which then closes on him as he walks away. And in between these two scenes, there is another crucial shot of Ethan silhouetted in an entryway, bent in grief, neither inside nor outside.

Scenes like these have a very particular effect for a movie-viewer. When two or more characters are on screen together, talking, occupied with each other, it’s easy to maintain the illusion that we are passively watching a story. But when we are alone with a lonely character, we feel more like participants – confidantes, sympathisers. Late in The Irishman, Frank speaks to a priest but is unable to say what he needs to say. The priest is not in a position to understand, but we viewers – omniscient, hopefully empathetic – have seen everything unfold over the preceding three hours. As we do with other lost people – like Ethan Edwards, like the dead Rodrigues, like Citizen Kane murmuring “Rosebud” on his deathbed, or Norman Bates at the end of Psycho, still possessed by his dead mother – we get to play the priest, listening, in a confessional.

[Earlier Hindu columns are here]

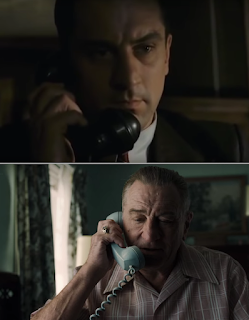

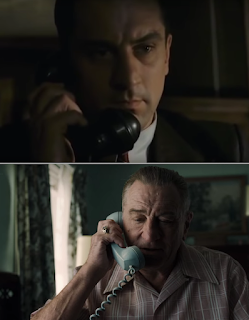

P.S. from my occasional Mix and Match series: Betrayal, uncertainty, remorse, Robert De Niro, and telephones. The sound of a persistently ringing phone (or the ring of a guilty conscience?) in an opium den in Once Upon a Time in America (1984) segues into a shot of the De Niro character Noodles making a crucial call.

Thirty-five years later, there are two notable telephone scenes involving De Niro’s Frank — another Judas figure— in The Irishman: one is a call he makes, the other is a call he contemplates making but doesn’t. The “What might have been?” theme is central to all three scenes.

---------------

In the final scene of Martin Scorsese’s epic The Irishman (onscreen title I Heard You Paint Houses), Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro) sits old and alone in a nursing home; it’s Christmas, but he has nothing to celebrate and no one to celebrate it with. Frank has asked that his room door be left ajar, and the film’s last shot has the camera outside, watching him through the half-open door.

In the final scene of Martin Scorsese’s epic The Irishman (onscreen title I Heard You Paint Houses), Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro) sits old and alone in a nursing home; it’s Christmas, but he has nothing to celebrate and no one to celebrate it with. Frank has asked that his room door be left ajar, and the film’s last shot has the camera outside, watching him through the half-open door.The shot worked for me on multiple levels. For one, it’s as intimate and poignant as (though more static than) the closing shot of Scorsese’s previous feature Silence where we glimpse something of

a man’s inner life after he has died – a Jesuit priest who renounced his religion but has a tiny cross in his hand as he is being cremated. Like Rodrigues in that film, Frank gave up something too, and we can’t say for certain how much he regrets it. And he is bearing a (different sort of) cross.

a man’s inner life after he has died – a Jesuit priest who renounced his religion but has a tiny cross in his hand as he is being cremated. Like Rodrigues in that film, Frank gave up something too, and we can’t say for certain how much he regrets it. And he is bearing a (different sort of) cross. The Irishman scene also calls back to a mysterious moment earlier in the film where, shortly after Frank begins working for the powerful union leader Jimmy Hoffa, he spends a night in Hoffa’s suite – and sees that his boss has left the door to his own room partly open. This could be a personality tic, or a sign of trust, or a pointer to their future friendship. But for Frank, it also represents an entry point to another world. He goes from living a truck-driver’s itinerant life – spending time on the road, away from family for long stretches – to finding a sense of belonging and identity in a new community.

It’s a set-up in some ways, though, and will eventually lead to (moral and physical) desolation. At what should be the hour of Frank’s big triumph – a banquet in his honour, well-attended by people whom he looks up to – he also gets ominous signs that he may soon have to pick sides against a friend. And this leads to his ultimate fate as a lonely old man trying to maintain some connection with a world that has passed him by: entombed, cut off from everyone – most notably from his daughter Peggy who might have served as his conscience.

That closing scene also reminds me of other movie characters who have isolated themselves – from civilisation, from their families, or even from themselves. And other doors in which such people are framed so that only we can see them. The most prominent such scene is from a work that Scorsese (part of a generation of American directors who were first movie nerds) was deeply influenced by as a youngster – a film made, as it happens, by an Irishman: John Ford’s The Searchers.

The protagonist of that film, Ethan Edwards (played by John Wayne), is one of cinema’s loneliest men, someone who is a wanderer to begin with but who, at the beginning of the story, at least has a family of sorts. When this family is massacred in an Indian attack, Ethan embarks on revenge but starts to lose his moral compass along the way – even coming close to killing his niece who had been abducted as a child.

Eventually order is restored and there is an ostensibly “happy” ending – but not for Ethan, who is too far steeped in blood and madness, and knows it. If the film began with a door opening and Ethan riding towards his brother’s house from a distance – being welcomed into a home – it ends with him framed by another door, which then closes on him as he walks away. And in between these two scenes, there is another crucial shot of Ethan silhouetted in an entryway, bent in grief, neither inside nor outside.

Eventually order is restored and there is an ostensibly “happy” ending – but not for Ethan, who is too far steeped in blood and madness, and knows it. If the film began with a door opening and Ethan riding towards his brother’s house from a distance – being welcomed into a home – it ends with him framed by another door, which then closes on him as he walks away. And in between these two scenes, there is another crucial shot of Ethan silhouetted in an entryway, bent in grief, neither inside nor outside.Scenes like these have a very particular effect for a movie-viewer. When two or more characters are on screen together, talking, occupied with each other, it’s easy to maintain the illusion that we are passively watching a story. But when we are alone with a lonely character, we feel more like participants – confidantes, sympathisers. Late in The Irishman, Frank speaks to a priest but is unable to say what he needs to say. The priest is not in a position to understand, but we viewers – omniscient, hopefully empathetic – have seen everything unfold over the preceding three hours. As we do with other lost people – like Ethan Edwards, like the dead Rodrigues, like Citizen Kane murmuring “Rosebud” on his deathbed, or Norman Bates at the end of Psycho, still possessed by his dead mother – we get to play the priest, listening, in a confessional.

[Earlier Hindu columns are here]

P.S. from my occasional Mix and Match series: Betrayal, uncertainty, remorse, Robert De Niro, and telephones. The sound of a persistently ringing phone (or the ring of a guilty conscience?) in an opium den in Once Upon a Time in America (1984) segues into a shot of the De Niro character Noodles making a crucial call.

Thirty-five years later, there are two notable telephone scenes involving De Niro’s Frank — another Judas figure— in The Irishman: one is a call he makes, the other is a call he contemplates making but doesn’t. The “What might have been?” theme is central to all three scenes.

Published on December 13, 2019 02:30

December 1, 2019

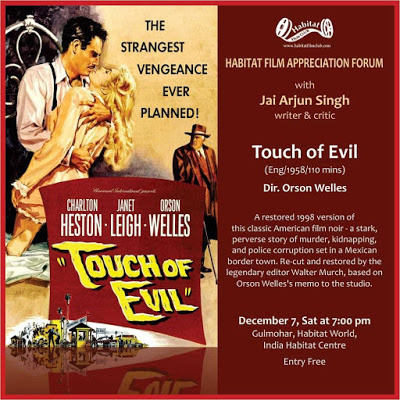

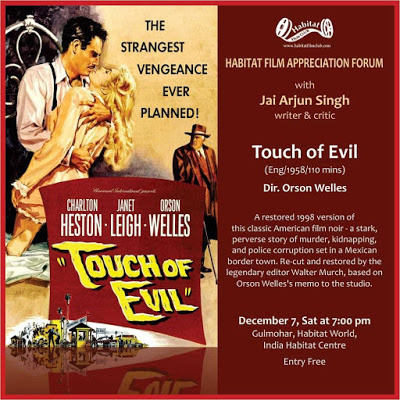

Introducing Touch of Evil at the Habitat Film Club

Hear ye, film buffs in Delhi. On December 7, I will be introducing Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil for the Habitat Film Club — please come across if you’re interested. The version I’m showing is the 1998 re-cut/restoration done by Walter Murch, guided by the long memo that an anguished Welles wrote to Universal Pictures after seeing their cut of the film in 1958. The introduction itself will probably only be five to seven minutes long, but we hope to have a more elaborate discussion after the screening.

(On another note, I hope to do more of these introductions/discussions in future. Among the many, many other personal favourites I considered screening this time: Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole, Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba, Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face, Brian De Palma’s Sisters and Hi Mom!, Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow, Powell-Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale, Ozu’s Early Summer, Val Lewton’s Curse of the Cat People, Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri, John Cassavetes’s A Woman Under the Influence. With any luck I’ll be able to screen some of these at some point.)

(On another note, I hope to do more of these introductions/discussions in future. Among the many, many other personal favourites I considered screening this time: Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole, Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba, Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face, Brian De Palma’s Sisters and Hi Mom!, Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow, Powell-Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale, Ozu’s Early Summer, Val Lewton’s Curse of the Cat People, Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri, John Cassavetes’s A Woman Under the Influence. With any luck I’ll be able to screen some of these at some point.)

Published on December 01, 2019 20:09

November 27, 2019

Meandering thoughts on the consumer-art relationship, glorification vs depiction, etc

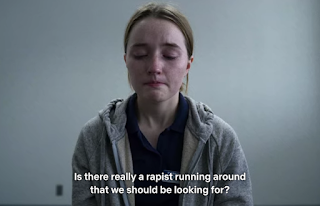

Parvathy Thiruvothu’s contribution to a recent Film Companion conversation has drawn a lot of attention. The link is here, and below (the relevant bits are around the 18.30-min and 26-min mark):

I have been a Parvathy fan for a while: based on the few films of hers I have seen recently ( Virus and Uyare among them), she is one of our finest performers and by all accounts she makes careful, conscientious choices about what sorts of films to be associated with. That is a valid personal choice, one that might go some way towards improving overall standards in the industry, and more power to her for it. And it’s easy to see why, in an industry notorious for bandying together, patting each other on the back and copping out of conversations about responsibility or ideology, her blunt statements – about the relationship between a society and the art it creates or celebrates – should come as a breath of fresh air.

But without denying the validity of anything Parvathy said in the interview, the broad topic is a more complex one than can be summarised by a well-articulated sound-byte during a conversation where a number of people sit down together and talk past each other. So here are a few complementary thoughts:

– In the increasingly heated, ideological conversations that take place around literature and cinema these days, questions like these get raised a lot: “Did the director/novelist/scriptwriter intend to glorify this problematic character or simply depict him without endorsing his actions?” “What is this writer’s/novel’s/film’s own position or ‘lens’?”

These are treated as urgent and essential questions, but here’s a proposal: they often don’t have straightforward answers – and sometimes they aren’t answerable at all. (We like to pretend they always are, so we can affirm our own value systems and maybe feel superior – and, if we are professional critics, so that we can get a piece written for a tight deadline without agonizing over it too much or arguing with ourselves.)

But many – maybe most – good creative works are the result of an artist (consciously or sub-consciously) engaging with human contradictions and the endless messiness of life, rather than setting out with a clear moralistic position and figuring out how to implement it through their work. And during such a process, if a writer or filmmaker lives – at least part of the time – in the head of a problematic character, there inevitably will be a certain degree of empathy or understanding involved; this in turn, when presented on screen, or on the page, might easily be read (by those who approach the work from a specific ideological perspective) as blanket “glorification”.

I had a conversation about related matters with the writer Devapriya Roy a few days ago, and one of the things she mentioned was that the creative process has a weirdly alchemical side to it: a serious novelist, in the process of world-making, often enters a space where one is not consciously thinking about morality or message-dispensing, where those things can even become irrelevant; one is simply in the head-space of the characters and their actions, working out what drives them to those actions, and the prose one will use to recreate that universe. “Endorsing” or “not endorsing” are beside the point when one is grappling with the difficult enough business of trying to be true to a particular world.

– Parvathy implies that a litmus test can determine what the filmmaker’s intentions were. Does an audience applaud and whistle at problematic behaviour (or leave ugly YouTube comments hero-worshipping the protagonist), or is the audience invited to introspect about what is going on?

This sounds good in theory, but in actual practice it isn’t a useful way of looking at the relationship between art and its consumers. With some works, yes, the gratuitousness or the catering to the “lowest common denominator” is relatively easy to see (an obvious example: a rape scene filmed for titillation); but in many other cases these things are much more muddled and subjective. (Parvathy herself says, with some confidence, that Joker didn’t have the “visual grammar of glorification” that Kabir Singh did. But many of the negative responses to Joker – many of them from thoughtful, sensitive viewers – have accused that film of glorification too. The history of cinema and literature is chockful of examples of passionate arguments being made from both ends of the spectrum, either defending or denouncing a controversial work.)

In any case, like it or not, even when a filmmaker or novelist sets out to depict a character as problematic or an episode as condemnable, there will STILL be viewers or readers who celebrate the character or the incident – or return home with a takeaway that the artist never reached for. There is no foolproof way in which audience/reader response can be used to determine the objective “intention” (again, assuming there is such a thing!) of a film or book.

– Bad people do routinely get away with doing bad things in the real world. So what does it mean to say that a creative work, to avoid charges of “endorsement”, must always depict the comeuppance of a problematic character? That it must clearly spell out to its audience, much like an anti-tobacco ad, that bad behaviour is punished in the end? (Interestingly, such demands are frequently made by the same “liberal” critics who celebrate realism in cinema and decry escapism. I propose that if you really want art to be “realistic”, you might need to allow some space for nihilistic art that says: there is no hope, evil always has been and always will be more powerful and more effective than good, bad people rarely get their just desserts; lump it.)

– Even the best of us have very complicated reptile brains, and the relationship between our realities and our fantasies can’t be neatly codified: it is possible for someone who leads a mostly “moral” life (whatever that might mean within a given context), someone who would rarely cause harm or hurt to another person, to be stimulated on some level by a creative depiction of such harm or hurt. (I know how much I relish certain forms of gore and violence in both literature and film – despite having experienced domestic violence firsthand as a child and having a visceral reaction to real-world violence. I also know – and strongly disagree with – many people who think that if you enjoy a “tasteless” joke about a topic That Must Not be Joked About, then it means that you are insensitive to the real-world implications of the thing in question. Nope. Doesn’t necessarily work that way.)

The third season of The Crown has just been released, and once again I am seeing responses from friends and acquaintances who are a little puzzled by their own interest in the show: they hate the idea of a monarchy in today’s world, are contemptuous of or just plain indifferent to the actual royals, and yet they have been stirred, moved by the show’s dramatised representation of these lives.

What does this mean? Could it be that our relationship with the creative works we consume, the relationship between our stated values and our inner lives, is more complex than we admit? Does any viewer who enjoys The Crown become a secret supporter of colonialism or feudalism? Is it possible to hate Winston Churchill for the role he played in the Bengal Famine of 1943 (and in the imperial project more generally) while also feeling a measure of sympathy for the old man in the Crown episode “Gloriana” who realises that his obsessive painting of a pond on his property was linked to his grief over the death of his three-year-old daughter? I know what my answers to these questions are, and I don’t want to impose them on anyone who might have different answers – for example, someone who has a more personal and immediate relationship with the 1943 tragedy – but it is worth raising the questions anyway.

(More on this soon, perhaps in a column. I also want to grumble a bit about this too-often-expressed idea that a swell of rousing music on the soundtrack associated with a particular character necessarily means that the film is celebrating everything that this character does.)

I have been a Parvathy fan for a while: based on the few films of hers I have seen recently ( Virus and Uyare among them), she is one of our finest performers and by all accounts she makes careful, conscientious choices about what sorts of films to be associated with. That is a valid personal choice, one that might go some way towards improving overall standards in the industry, and more power to her for it. And it’s easy to see why, in an industry notorious for bandying together, patting each other on the back and copping out of conversations about responsibility or ideology, her blunt statements – about the relationship between a society and the art it creates or celebrates – should come as a breath of fresh air.

But without denying the validity of anything Parvathy said in the interview, the broad topic is a more complex one than can be summarised by a well-articulated sound-byte during a conversation where a number of people sit down together and talk past each other. So here are a few complementary thoughts:

– In the increasingly heated, ideological conversations that take place around literature and cinema these days, questions like these get raised a lot: “Did the director/novelist/scriptwriter intend to glorify this problematic character or simply depict him without endorsing his actions?” “What is this writer’s/novel’s/film’s own position or ‘lens’?”

These are treated as urgent and essential questions, but here’s a proposal: they often don’t have straightforward answers – and sometimes they aren’t answerable at all. (We like to pretend they always are, so we can affirm our own value systems and maybe feel superior – and, if we are professional critics, so that we can get a piece written for a tight deadline without agonizing over it too much or arguing with ourselves.)

But many – maybe most – good creative works are the result of an artist (consciously or sub-consciously) engaging with human contradictions and the endless messiness of life, rather than setting out with a clear moralistic position and figuring out how to implement it through their work. And during such a process, if a writer or filmmaker lives – at least part of the time – in the head of a problematic character, there inevitably will be a certain degree of empathy or understanding involved; this in turn, when presented on screen, or on the page, might easily be read (by those who approach the work from a specific ideological perspective) as blanket “glorification”.

I had a conversation about related matters with the writer Devapriya Roy a few days ago, and one of the things she mentioned was that the creative process has a weirdly alchemical side to it: a serious novelist, in the process of world-making, often enters a space where one is not consciously thinking about morality or message-dispensing, where those things can even become irrelevant; one is simply in the head-space of the characters and their actions, working out what drives them to those actions, and the prose one will use to recreate that universe. “Endorsing” or “not endorsing” are beside the point when one is grappling with the difficult enough business of trying to be true to a particular world.

– Parvathy implies that a litmus test can determine what the filmmaker’s intentions were. Does an audience applaud and whistle at problematic behaviour (or leave ugly YouTube comments hero-worshipping the protagonist), or is the audience invited to introspect about what is going on?

This sounds good in theory, but in actual practice it isn’t a useful way of looking at the relationship between art and its consumers. With some works, yes, the gratuitousness or the catering to the “lowest common denominator” is relatively easy to see (an obvious example: a rape scene filmed for titillation); but in many other cases these things are much more muddled and subjective. (Parvathy herself says, with some confidence, that Joker didn’t have the “visual grammar of glorification” that Kabir Singh did. But many of the negative responses to Joker – many of them from thoughtful, sensitive viewers – have accused that film of glorification too. The history of cinema and literature is chockful of examples of passionate arguments being made from both ends of the spectrum, either defending or denouncing a controversial work.)

In any case, like it or not, even when a filmmaker or novelist sets out to depict a character as problematic or an episode as condemnable, there will STILL be viewers or readers who celebrate the character or the incident – or return home with a takeaway that the artist never reached for. There is no foolproof way in which audience/reader response can be used to determine the objective “intention” (again, assuming there is such a thing!) of a film or book.

– Bad people do routinely get away with doing bad things in the real world. So what does it mean to say that a creative work, to avoid charges of “endorsement”, must always depict the comeuppance of a problematic character? That it must clearly spell out to its audience, much like an anti-tobacco ad, that bad behaviour is punished in the end? (Interestingly, such demands are frequently made by the same “liberal” critics who celebrate realism in cinema and decry escapism. I propose that if you really want art to be “realistic”, you might need to allow some space for nihilistic art that says: there is no hope, evil always has been and always will be more powerful and more effective than good, bad people rarely get their just desserts; lump it.)

– Even the best of us have very complicated reptile brains, and the relationship between our realities and our fantasies can’t be neatly codified: it is possible for someone who leads a mostly “moral” life (whatever that might mean within a given context), someone who would rarely cause harm or hurt to another person, to be stimulated on some level by a creative depiction of such harm or hurt. (I know how much I relish certain forms of gore and violence in both literature and film – despite having experienced domestic violence firsthand as a child and having a visceral reaction to real-world violence. I also know – and strongly disagree with – many people who think that if you enjoy a “tasteless” joke about a topic That Must Not be Joked About, then it means that you are insensitive to the real-world implications of the thing in question. Nope. Doesn’t necessarily work that way.)

The third season of The Crown has just been released, and once again I am seeing responses from friends and acquaintances who are a little puzzled by their own interest in the show: they hate the idea of a monarchy in today’s world, are contemptuous of or just plain indifferent to the actual royals, and yet they have been stirred, moved by the show’s dramatised representation of these lives.

What does this mean? Could it be that our relationship with the creative works we consume, the relationship between our stated values and our inner lives, is more complex than we admit? Does any viewer who enjoys The Crown become a secret supporter of colonialism or feudalism? Is it possible to hate Winston Churchill for the role he played in the Bengal Famine of 1943 (and in the imperial project more generally) while also feeling a measure of sympathy for the old man in the Crown episode “Gloriana” who realises that his obsessive painting of a pond on his property was linked to his grief over the death of his three-year-old daughter? I know what my answers to these questions are, and I don’t want to impose them on anyone who might have different answers – for example, someone who has a more personal and immediate relationship with the 1943 tragedy – but it is worth raising the questions anyway.

(More on this soon, perhaps in a column. I also want to grumble a bit about this too-often-expressed idea that a swell of rousing music on the soundtrack associated with a particular character necessarily means that the film is celebrating everything that this character does.)

Published on November 27, 2019 18:59

November 15, 2019

How to love a hotchpotch meal (or a masala film)

[Now that the Wokes have decided that Friends was a regressive/trashy show, I am looking at the possibility of doing regular columns examining its many layers. In my latest “moments” piece for The Hindu, thoughts on Rachel’s hideous Thanksgiving trifle, Joey as an egalitarian food-buff, the Sanskrit term “sahriday”, and masala cinema]

------------------

In season six, episode nine of the hugely popular sitcom Friends, the once-mollycoddled Rachel (Jennifer Aniston), not known for her culinary prowess, decides to make an English Trifle for Thanksgiving dinner. But when two of the pages in the cookbook get glued together, she ends up mixing recipes and producing a satanic concoction of shepherd’s pie and dessert: the layers include jam, beef with peas and onions, bananas and ladyfingers. In short, many things that are perfectly good in their own right, but which no sane eater would think go well together.

In season six, episode nine of the hugely popular sitcom Friends, the once-mollycoddled Rachel (Jennifer Aniston), not known for her culinary prowess, decides to make an English Trifle for Thanksgiving dinner. But when two of the pages in the cookbook get glued together, she ends up mixing recipes and producing a satanic concoction of shepherd’s pie and dessert: the layers include jam, beef with peas and onions, bananas and ladyfingers. In short, many things that are perfectly good in their own right, but which no sane eater would think go well together.

But is “sanity” all that it’s made out to be?

The evening wears on, the dish is served, everyone in the room gasps and wheezes and finds ways of disposing their plate without hurting Rachel’s feelings. “It tastes like FEET!” says Ross. But there is one person – a true food lover, friend to any blundering chef – who genuinely enjoys the dish. “I like it,” Joey announces between mouthfuls, “What’s not to like? Jam – good. Custard – good. Meat – goooodd!”

If you know the old Boris Karloff-Frankenstein films, you might be reminded of the scene in the 1935 Bride of Frankenstein where the Monster, befriended by a blind hermit, grunts “Good! Good!” in childlike delight as he experiences a glass of wine, bread and a cigarette for the first time. Here is a barely sentient creature putting things in his mouth, responding with his senses, not with sophisticated preconceptions about taste.

If you know the old Boris Karloff-Frankenstein films, you might be reminded of the scene in the 1935 Bride of Frankenstein where the Monster, befriended by a blind hermit, grunts “Good! Good!” in childlike delight as he experiences a glass of wine, bread and a cigarette for the first time. Here is a barely sentient creature putting things in his mouth, responding with his senses, not with sophisticated preconceptions about taste.

There is something pure and enviable about this, and I feel similarly about what Joey does in that Friends episode. Within the given context, we are meant to see him as a gluttonous philistine, but I also view the scene as a display of egalitarianism, coming from a boundless love for a particular thing or activity (in this case, food or eating). It weirdly reminds me of the Sanskrit word “sahriday”, which has different layers of meaning but which has often been used to describe the ideal reader, “of one heart” with an author: someone fully responsive to a creative work and engaging with it at all the levels that the artist might wish for.

With apologies to my gourmet friends, there is an off-kilter logic in Joey’s caveman grunts of appreciation: he is treating each ingredient on its own terms, focusing on the component parts instead of worrying about how consistent or organic the whole dish is. This also puts me in mind of some of the conversations around the “masala” film, which constantly mixes and mashes tropes. This sort of movie – championed by Jonathan Gil Harris in his recent book Masala Shakespeare, and also defended by a small minority of film critics who still have an appetite for the form – is easily denigrated today. Understatement and psychological realism have become vital to Hindi cinema, writers and directors are telling personal stories rather than following old boilerplates. Which is a welcome development, but it also leads to an often thoughtless putting down of earlier modes of expression where many tones and genres could coexist.

With apologies to my gourmet friends, there is an off-kilter logic in Joey’s caveman grunts of appreciation: he is treating each ingredient on its own terms, focusing on the component parts instead of worrying about how consistent or organic the whole dish is. This also puts me in mind of some of the conversations around the “masala” film, which constantly mixes and mashes tropes. This sort of movie – championed by Jonathan Gil Harris in his recent book Masala Shakespeare, and also defended by a small minority of film critics who still have an appetite for the form – is easily denigrated today. Understatement and psychological realism have become vital to Hindi cinema, writers and directors are telling personal stories rather than following old boilerplates. Which is a welcome development, but it also leads to an often thoughtless putting down of earlier modes of expression where many tones and genres could coexist.

Perhaps appreciating masala cinema involve a certain brain type, one that can compartmentalize elements and assess each separately. This, by the way, is not the same thing as lack of discernment: a viewer of a masala film can still make thoughtful judgements about whether the comedy track, or the drama track, or the musical track, is well-done. Joey wouldn’t care for the trifle if the beef was overcooked or the bananas were raw!

There is always the question: do lines still need to be drawn – is it possible that some things simply aren’t compatible? Hard to say. There have been terrific films that combined genres you wouldn’t think could go together – horror and goofy comedy, for example, or noir and musical. It gets trickier when you combine more than two – for that, you probably have to look at something like the mainstream Hindi film as it once was, shifting from weepy drama to comic interlude to song-and-dance to dhishoom-dhishoom.

I love that sort of cinema, but I also understand why it can annoy or exhaust people. And though I experiment a lot with food, I did feel my gorge rising once when someone showed me a photo of banana pieces on a pizza. Most of us have breaking points; few of us can be as open-hearted as Joey.

[Earlier Hindu columns are here]

------------------

In season six, episode nine of the hugely popular sitcom Friends, the once-mollycoddled Rachel (Jennifer Aniston), not known for her culinary prowess, decides to make an English Trifle for Thanksgiving dinner. But when two of the pages in the cookbook get glued together, she ends up mixing recipes and producing a satanic concoction of shepherd’s pie and dessert: the layers include jam, beef with peas and onions, bananas and ladyfingers. In short, many things that are perfectly good in their own right, but which no sane eater would think go well together.

In season six, episode nine of the hugely popular sitcom Friends, the once-mollycoddled Rachel (Jennifer Aniston), not known for her culinary prowess, decides to make an English Trifle for Thanksgiving dinner. But when two of the pages in the cookbook get glued together, she ends up mixing recipes and producing a satanic concoction of shepherd’s pie and dessert: the layers include jam, beef with peas and onions, bananas and ladyfingers. In short, many things that are perfectly good in their own right, but which no sane eater would think go well together. But is “sanity” all that it’s made out to be?

The evening wears on, the dish is served, everyone in the room gasps and wheezes and finds ways of disposing their plate without hurting Rachel’s feelings. “It tastes like FEET!” says Ross. But there is one person – a true food lover, friend to any blundering chef – who genuinely enjoys the dish. “I like it,” Joey announces between mouthfuls, “What’s not to like? Jam – good. Custard – good. Meat – goooodd!”

If you know the old Boris Karloff-Frankenstein films, you might be reminded of the scene in the 1935 Bride of Frankenstein where the Monster, befriended by a blind hermit, grunts “Good! Good!” in childlike delight as he experiences a glass of wine, bread and a cigarette for the first time. Here is a barely sentient creature putting things in his mouth, responding with his senses, not with sophisticated preconceptions about taste.

If you know the old Boris Karloff-Frankenstein films, you might be reminded of the scene in the 1935 Bride of Frankenstein where the Monster, befriended by a blind hermit, grunts “Good! Good!” in childlike delight as he experiences a glass of wine, bread and a cigarette for the first time. Here is a barely sentient creature putting things in his mouth, responding with his senses, not with sophisticated preconceptions about taste.There is something pure and enviable about this, and I feel similarly about what Joey does in that Friends episode. Within the given context, we are meant to see him as a gluttonous philistine, but I also view the scene as a display of egalitarianism, coming from a boundless love for a particular thing or activity (in this case, food or eating). It weirdly reminds me of the Sanskrit word “sahriday”, which has different layers of meaning but which has often been used to describe the ideal reader, “of one heart” with an author: someone fully responsive to a creative work and engaging with it at all the levels that the artist might wish for.

With apologies to my gourmet friends, there is an off-kilter logic in Joey’s caveman grunts of appreciation: he is treating each ingredient on its own terms, focusing on the component parts instead of worrying about how consistent or organic the whole dish is. This also puts me in mind of some of the conversations around the “masala” film, which constantly mixes and mashes tropes. This sort of movie – championed by Jonathan Gil Harris in his recent book Masala Shakespeare, and also defended by a small minority of film critics who still have an appetite for the form – is easily denigrated today. Understatement and psychological realism have become vital to Hindi cinema, writers and directors are telling personal stories rather than following old boilerplates. Which is a welcome development, but it also leads to an often thoughtless putting down of earlier modes of expression where many tones and genres could coexist.

With apologies to my gourmet friends, there is an off-kilter logic in Joey’s caveman grunts of appreciation: he is treating each ingredient on its own terms, focusing on the component parts instead of worrying about how consistent or organic the whole dish is. This also puts me in mind of some of the conversations around the “masala” film, which constantly mixes and mashes tropes. This sort of movie – championed by Jonathan Gil Harris in his recent book Masala Shakespeare, and also defended by a small minority of film critics who still have an appetite for the form – is easily denigrated today. Understatement and psychological realism have become vital to Hindi cinema, writers and directors are telling personal stories rather than following old boilerplates. Which is a welcome development, but it also leads to an often thoughtless putting down of earlier modes of expression where many tones and genres could coexist. Perhaps appreciating masala cinema involve a certain brain type, one that can compartmentalize elements and assess each separately. This, by the way, is not the same thing as lack of discernment: a viewer of a masala film can still make thoughtful judgements about whether the comedy track, or the drama track, or the musical track, is well-done. Joey wouldn’t care for the trifle if the beef was overcooked or the bananas were raw!

There is always the question: do lines still need to be drawn – is it possible that some things simply aren’t compatible? Hard to say. There have been terrific films that combined genres you wouldn’t think could go together – horror and goofy comedy, for example, or noir and musical. It gets trickier when you combine more than two – for that, you probably have to look at something like the mainstream Hindi film as it once was, shifting from weepy drama to comic interlude to song-and-dance to dhishoom-dhishoom.

I love that sort of cinema, but I also understand why it can annoy or exhaust people. And though I experiment a lot with food, I did feel my gorge rising once when someone showed me a photo of banana pieces on a pizza. Most of us have breaking points; few of us can be as open-hearted as Joey.

[Earlier Hindu columns are here]

Published on November 15, 2019 11:19

October 30, 2019

A few good books about gunpowder, masala, and other forms of "impurity"

[my latest Bookshelves column for First Post]

--------------

A few weeks ago I was at the Gothenburg Book Fair, participating – with the writers Anjum Hasan and Girish Shahane, and the editor Ann Ighe – in a short conversation around the theme “Europe and India: how do these parts of the world look at each other today?” I was jetlagged and less than coherent (and not fully sure what I wanted to say anyway), but one obvious point to stress – for the mainly non-Indian audience – was that thinking of India as a culturally homogenous country would be a big mistake: that it is in many ways as diverse as Europe.

My own encounters with this cultural diversity have taken many forms over the decades – it has been intimidating, enriching and humbling in turn. Trying to understand what “Indianness” might be necessarily means learning new things all the time; you’re a student for life, constantly re-evaluating your assumptions. And for someone who has grown up in mainly Anglophone environments and led a circumscribed life in some ways, the learning process has many twists and turns. For instance: as a child you might love Hindi cinema (while reading almost exclusively in English, about enchanted woods and quaint European towns that bear little relation to the world you live in); later, you might be so sated by the excesses of Hindi movies that you shift to more restrained cinematic idioms; but later still, you return and relish the language of melodrama from a more open-minded and well-rounded perspective; meanwhile, as a reader, you start to discover literature from other parts of India.

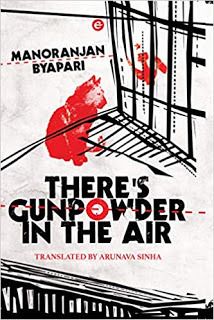

In recent months, when I began watching some of the outstanding work in current Malayalam cinema, I re-experienced something of what it was like as a teenager getting into “independent” cinema for the first time. But if films from across India are more easily available now (and have good subtitles), it has also been an exciting few years for anyone working on the books beat. We have higher-quality translations than we had, say, 20 years ago – for those of us who read mostly in English, there is greater access to what we call “regional” literature. A large proportion of my fiction reading in the past few years has been translated works by contemporary writers, ranging from the books of Perumal Murugan (One Part Woman, Pyre) and Benyamin (Goat Days), to KR Meera (Hangwoman) and, most recently, Manoranjan Byapari’s enthralling There’s Gunpowder in the Air (translated from Bengali to English by Arunava Sinha). And almost invariably, such reading has caused me to rethink my ideas about literary form and structure while also learning new things about other places.

In recent months, when I began watching some of the outstanding work in current Malayalam cinema, I re-experienced something of what it was like as a teenager getting into “independent” cinema for the first time. But if films from across India are more easily available now (and have good subtitles), it has also been an exciting few years for anyone working on the books beat. We have higher-quality translations than we had, say, 20 years ago – for those of us who read mostly in English, there is greater access to what we call “regional” literature. A large proportion of my fiction reading in the past few years has been translated works by contemporary writers, ranging from the books of Perumal Murugan (One Part Woman, Pyre) and Benyamin (Goat Days), to KR Meera (Hangwoman) and, most recently, Manoranjan Byapari’s enthralling There’s Gunpowder in the Air (translated from Bengali to English by Arunava Sinha). And almost invariably, such reading has caused me to rethink my ideas about literary form and structure while also learning new things about other places.

Which is a longwinded way of saying that cultural variedness is one of the most daunting as well as one of the most appealing things about this country. And this variedness has been under threat for a while now, thanks to a determined ongoing drive towards the notion of a pure Hindu past – glorious and uncontaminated, before all the “invaders” came in – as well as the idea that a single language can be imposed across the country.

I was thinking about these things again while preparing for another upcoming talk – a discussion around the theme of “purity in text” at the Chandigarh Literature Festival next week. To take just a short sample of recent books that deal with the purity-impurity theme in one way or the other (and starting with my fellow panellists in Chandigarh):

Jonathan Gil Harris’s Masala Shakespeare is a celebration of the tonal disunities – and the revitalising aspects of “masala” – in the plays of Shakespeare as well as in the best of popular Hindi cinema; by extension, it looks at the colourful multiplicity (or “more-than-oneness”, as Harris puts it) of India as a country. Meanwhile, Annie Zaidi’s allegorical Prelude to a Riot, told in multiple voices, deals with many ways of living in India. In one passage, a group calling itself the Self Respect Forum writes a letter to a newspaper editor objecting to the publication of certain “vulgar” poems about Goddesses and mothers; in her polite but firm reply, the editor alludes to the importance of "a river-like flow of culture and ideas" and the ability to recognise the fluidity of human beings.

Such fluidity has often been expressed in the many different interpretations of our mythology, including the great epics. Though the proponents of militant Hindutva would prefer to shut their eyes to this, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata shape-shift constantly as you move from one part of the country to another; heroes become villains and vice versa, a familiar episode becomes unfamiliar and unsettling when viewed through the eyes of a specific character. Among the recent books that stress this variability are Aditya Iyengar’s Bhumika, about Sita experiencing what her life would have been if she hadn't met and married Rama. In this alternate telling, she does meet him eventually, but it's on a battlefield, on opposite sides of an ideological divide; conventional ideas of Rama and Sita (or “Rama-ness” and “Sita-ness”, if you like) are challenged, and there is a neat twist on the Agni-pariksha (which, after all, is also about a very rigid view of purity).

Such fluidity has often been expressed in the many different interpretations of our mythology, including the great epics. Though the proponents of militant Hindutva would prefer to shut their eyes to this, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata shape-shift constantly as you move from one part of the country to another; heroes become villains and vice versa, a familiar episode becomes unfamiliar and unsettling when viewed through the eyes of a specific character. Among the recent books that stress this variability are Aditya Iyengar’s Bhumika, about Sita experiencing what her life would have been if she hadn't met and married Rama. In this alternate telling, she does meet him eventually, but it's on a battlefield, on opposite sides of an ideological divide; conventional ideas of Rama and Sita (or “Rama-ness” and “Sita-ness”, if you like) are challenged, and there is a neat twist on the Agni-pariksha (which, after all, is also about a very rigid view of purity).

Other books I have in mind include the anthology Which of Us are Aryans? (with essays by Romila Thapar and Kai Friese, among others) and Tony Joseph’s Early Indians, both of which in different ways question the very idea of national pride based on “purity” by looking at the much deeper history of our species – through the archaeological and genetic evidence that can be discomfiting for those who need to believe that Vedic culture grew “organically” out of Indian soil. As these books remind us, larger time-scales, including geological ones, can make utter nonsense of our parochial pride in belonging to this or that “group”.

But there is always a more poetic view of variedness too, rooted in the here and now – such as the one provided in a book I mentioned above, There’s Gunpowder in the Air. Though set in the most confined of places, a prison in 1970s Bengal, this enthralling narrative is also, in its own distinct way, about diversity: about how life’s rich pageant – and the many ways of thinking about oneself and others – may be discovered even within narrow walls, and how a jail can become a microcosm for the world. These are all books that make you thrill to the possibilities of being impure or unfixed.

[Earlier First Post columns are here]

--------------

A few weeks ago I was at the Gothenburg Book Fair, participating – with the writers Anjum Hasan and Girish Shahane, and the editor Ann Ighe – in a short conversation around the theme “Europe and India: how do these parts of the world look at each other today?” I was jetlagged and less than coherent (and not fully sure what I wanted to say anyway), but one obvious point to stress – for the mainly non-Indian audience – was that thinking of India as a culturally homogenous country would be a big mistake: that it is in many ways as diverse as Europe.

My own encounters with this cultural diversity have taken many forms over the decades – it has been intimidating, enriching and humbling in turn. Trying to understand what “Indianness” might be necessarily means learning new things all the time; you’re a student for life, constantly re-evaluating your assumptions. And for someone who has grown up in mainly Anglophone environments and led a circumscribed life in some ways, the learning process has many twists and turns. For instance: as a child you might love Hindi cinema (while reading almost exclusively in English, about enchanted woods and quaint European towns that bear little relation to the world you live in); later, you might be so sated by the excesses of Hindi movies that you shift to more restrained cinematic idioms; but later still, you return and relish the language of melodrama from a more open-minded and well-rounded perspective; meanwhile, as a reader, you start to discover literature from other parts of India.

In recent months, when I began watching some of the outstanding work in current Malayalam cinema, I re-experienced something of what it was like as a teenager getting into “independent” cinema for the first time. But if films from across India are more easily available now (and have good subtitles), it has also been an exciting few years for anyone working on the books beat. We have higher-quality translations than we had, say, 20 years ago – for those of us who read mostly in English, there is greater access to what we call “regional” literature. A large proportion of my fiction reading in the past few years has been translated works by contemporary writers, ranging from the books of Perumal Murugan (One Part Woman, Pyre) and Benyamin (Goat Days), to KR Meera (Hangwoman) and, most recently, Manoranjan Byapari’s enthralling There’s Gunpowder in the Air (translated from Bengali to English by Arunava Sinha). And almost invariably, such reading has caused me to rethink my ideas about literary form and structure while also learning new things about other places.

In recent months, when I began watching some of the outstanding work in current Malayalam cinema, I re-experienced something of what it was like as a teenager getting into “independent” cinema for the first time. But if films from across India are more easily available now (and have good subtitles), it has also been an exciting few years for anyone working on the books beat. We have higher-quality translations than we had, say, 20 years ago – for those of us who read mostly in English, there is greater access to what we call “regional” literature. A large proportion of my fiction reading in the past few years has been translated works by contemporary writers, ranging from the books of Perumal Murugan (One Part Woman, Pyre) and Benyamin (Goat Days), to KR Meera (Hangwoman) and, most recently, Manoranjan Byapari’s enthralling There’s Gunpowder in the Air (translated from Bengali to English by Arunava Sinha). And almost invariably, such reading has caused me to rethink my ideas about literary form and structure while also learning new things about other places. Which is a longwinded way of saying that cultural variedness is one of the most daunting as well as one of the most appealing things about this country. And this variedness has been under threat for a while now, thanks to a determined ongoing drive towards the notion of a pure Hindu past – glorious and uncontaminated, before all the “invaders” came in – as well as the idea that a single language can be imposed across the country.

I was thinking about these things again while preparing for another upcoming talk – a discussion around the theme of “purity in text” at the Chandigarh Literature Festival next week. To take just a short sample of recent books that deal with the purity-impurity theme in one way or the other (and starting with my fellow panellists in Chandigarh):

Jonathan Gil Harris’s Masala Shakespeare is a celebration of the tonal disunities – and the revitalising aspects of “masala” – in the plays of Shakespeare as well as in the best of popular Hindi cinema; by extension, it looks at the colourful multiplicity (or “more-than-oneness”, as Harris puts it) of India as a country. Meanwhile, Annie Zaidi’s allegorical Prelude to a Riot, told in multiple voices, deals with many ways of living in India. In one passage, a group calling itself the Self Respect Forum writes a letter to a newspaper editor objecting to the publication of certain “vulgar” poems about Goddesses and mothers; in her polite but firm reply, the editor alludes to the importance of "a river-like flow of culture and ideas" and the ability to recognise the fluidity of human beings.