Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 57

October 6, 2018

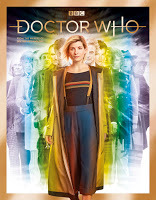

The Story of Doctor Who

The nice people at Doctor Who Magazine have published The Story of Doctor Who, a shiny, comprehensive guide to the 55-year history of the series. It's perfect for those joining or returning to Doctor Who with Jodie Whittaker's Doctor - and has plenty to delight those of us who think they know it all backwards.

The nice people at Doctor Who Magazine have published The Story of Doctor Who, a shiny, comprehensive guide to the 55-year history of the series. It's perfect for those joining or returning to Doctor Who with Jodie Whittaker's Doctor - and has plenty to delight those of us who think they know it all backwards.I've written the pieces on the Second, Fourth, Sixth and Twelfth Doctors, and dug out all sorts of stuff that was new to me. In fact, quite a lot of my work right now is looking for new things to say about Doctor Who, with a lot of dogged detective work to make sense of conflicting accounts of how particular bits of the series were made.

My knowing-it-backwards has also informed my watching of Jonathan Creek, which I never really saw when it was on in the 1990s but we're enjoying now on Netflix. The major revelation is how much it owes to Sherlock Holmes, which I'll write something about another time. But the Sixth Doctor is the first person killed in the series; in the first episode of the second series (produced by Verity Lambert), the Fifth Doctor walks under a broken-off piece off the TARDIS. Then, in episode 2.5, when the police arrest Alistair Petrie they also confiscate his VHS of

Doctor Who and the Two Doctors

.

My knowing-it-backwards has also informed my watching of Jonathan Creek, which I never really saw when it was on in the 1990s but we're enjoying now on Netflix. The major revelation is how much it owes to Sherlock Holmes, which I'll write something about another time. But the Sixth Doctor is the first person killed in the series; in the first episode of the second series (produced by Verity Lambert), the Fifth Doctor walks under a broken-off piece off the TARDIS. Then, in episode 2.5, when the police arrest Alistair Petrie they also confiscate his VHS of

Doctor Who and the Two Doctors

.

(That Doctor Who story saw Patrick Troughton return as the Second Doctor, accompanied by Frazer Hines as his companion Jamie McCrimmon. A couple of years ago, I wrote an audio Doctor Who story, The Outliers in which Frazer played Jamie and also recreated Troughton's Doctor, both of them battling a smooth management consultant in space, played by Alistair Petrie.)

Anyway. I am giddy with excitement about new Doctor Who tomorrow. Amid all the flurry of promotion going on, I recommend catching up with this morning's Saturday Live, in which Richard Cole quizzed m'colleague Christel Dee. She talks candidly about growing up in care, how Doctor Who helped her to come out as gay, and her obsession with Ace. I'm a big fan of Saturday Live and a bit thrilled to have got a mention.

Have I mentioned that we wrote a book?

Published on October 06, 2018 02:18

October 4, 2018

We Have Always Lived in the Castle, by Shirley Jackson

Straight on from her

Dark Tales

, I've ploughed through Shirley Jackson's final (and greatest, says the back cover) novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962).

Straight on from her

Dark Tales

, I've ploughed through Shirley Jackson's final (and greatest, says the back cover) novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962).It's told by 18 year-old Mary Kate Blackwood, known to everyone as "Merricat", a strange, scared girl with much to be afraid of. To begin, we follow her on an essential, regular trip into town to shop for food, where she must endure the mostly passive tyranny of ordinary people. It's incredibly effective, a threat that feels horribly real. Only once we've experienced and felt it does Jackson reveal why: almost all of Merricat's family died six years ago, poisoned by arsenic intentionally put in the sugar bowl.

Merricat now lives in the old family house with her agarophobic elder sister Constance - acquitted of the murder but still generally thought guilty - and her uncle Julian, who survived the poisoning at some cost. Wheelchair-bound and mentally disturbed, he's determined to uncover what really happened that night... Merricat is the only one to ever leave the family home, and her head is full of strange thoughts about magic ways to protect the house and also journeys to the Moon.

Into this unsettling space comes cousin Charles, who soon casts a spell over Constance and threatens the whole household. But he's just one of many tensions: the townspeople are never far away, and Merricat is herself bound by all kinds of rules - things she seems innately to know she is not allowed to do. The immaculate, ordered domestic space is a place beset with danger.

As in the Dark Tales, Jackson makes this strange situation so credible. In her afterword to the Penguin Classics edition, Joyce Carol Oates speaks of Jackson's own agoraphobia and says:

"Jackson's difficulties with her fellow citizens in North Bennington, Vermont are well documented in Judy Oppenheimer's harrowing biography, Private Demons (1988): the suggestion is that Jackson and her husband, the flamboyant 'Jewish-intellectual' cultural critic Stanley Edgar Hyman aroused resentment, if not outright anti-Semitism, in their more convention neighbours."

Joyce Carol Oates, afterword to We Have Always Lived in the Castle, p. 152.I think Jackson drawns on more than her own experience of real horror, too. There's repeated mention of a figurine, an object that survives a fire in the house. It's surely significant that it's always described as the "Dresden figurine", conjuring images of another conflagration.

The fire involves the most chilling moment of the whole novel. We know the townspeople are antagonistic to the Blackwoods, but in a moment of crisis the local men rush to help put out the fire. Only then, emerging from the house to the expectant crowd, the head of the men picks up a stone and throws it back at the building to smash a window. It gives licence to the mob, who stampede on the house...

Whatever the strange and murderous qualities of the household, it's the ordinary people outside who are most to be feared.

Published on October 04, 2018 07:58

September 28, 2018

Dark Tales, by Shirley Jackson

I've read loads since completing Space Odyssey - chapters of various mates' works in progress and all sorts of material for work, including a sizeable chunk of Amelia Edwards' 1878 travelogue, A Thousand Miles Up The Nile. Then there's Shirley Jackson.

Dark Tales is a collection of seventeen short stories by a writer who really ought to be a household name. One is a ghost story, one involves psychic abilities, one involves a painting that's like something out of MR James. But the rest are unsettling stories of very human monsters, the tyranny of ordinary snobbery, pettiness and meaness, of social conventions and small communities. They all take place in the modern day, in settings busy with people getting on with everyday life. The best of them are at their most disturbing because they're psychologically real. Women are usually central.

Dark Tales is a collection of seventeen short stories by a writer who really ought to be a household name. One is a ghost story, one involves psychic abilities, one involves a painting that's like something out of MR James. But the rest are unsettling stories of very human monsters, the tyranny of ordinary snobbery, pettiness and meaness, of social conventions and small communities. They all take place in the modern day, in settings busy with people getting on with everyday life. The best of them are at their most disturbing because they're psychologically real. Women are usually central.

"The Good Wife" is about a jealous husband who incarcerates his wife. The twist ending reveals that the husband is more monstrous than first supposed, but what lingers is the awful detail of the wife's gradual acquiesence - having clearly tried to resist him to no effect, she now presents nothing but sweetness in the vain hope he will relent. In "The Honeymoon of Mrs Smith", a young bride accepts her imminent murder rather than make a fuss. In "Home", a woman learns better than to speak of the ghostly experience that almost killed her. The horror is not only of passivity, but of the ways these women are rendered passive.

In the brilliant "The Possibility of Evil", a respectable old lady notes the strains affecting her neighbours, before we discover that she's been sending them all anonymous, poisonous letters. Yet there's real tension when this malicious creature unwittingly risks being exposed. Jackson has deftly make us sympathise with the monster.

I'm keen to know more about Jackson and what shaped her extraordinary vision. It's surely no coincidence that her first story, "The Lottery" (not included in this anthology) was first published in 1948, in a post-war world lacking moral certainties - though some readers felt strongly otherwise, and she received death threats in response. I feel something noirish, something Hitchcock, in her stories, something haunted by the Holocaust and the Bomb, something deeply ill at ease with "ordinary" life.

It all feels so very contemporary, but not overtly political. In the final story in the collection, "The Summer People", there's mention of degeneration and inbreeding (p. 183), but the story is about the growing anxiety of an old couple when the local shops are out of groceries and oil. It's so relatable, the horror is horribly real.

I'm keen to see the new film version of We Have Always Lived in the Castle once I've reread Jackson's novel and adore the 1963 film The Haunting (based on The Haunting of Hill House), which first got me reading her stuff in my teens. I've also got a biography of Jackson - so more of this to come.

Dark Tales is a collection of seventeen short stories by a writer who really ought to be a household name. One is a ghost story, one involves psychic abilities, one involves a painting that's like something out of MR James. But the rest are unsettling stories of very human monsters, the tyranny of ordinary snobbery, pettiness and meaness, of social conventions and small communities. They all take place in the modern day, in settings busy with people getting on with everyday life. The best of them are at their most disturbing because they're psychologically real. Women are usually central.

Dark Tales is a collection of seventeen short stories by a writer who really ought to be a household name. One is a ghost story, one involves psychic abilities, one involves a painting that's like something out of MR James. But the rest are unsettling stories of very human monsters, the tyranny of ordinary snobbery, pettiness and meaness, of social conventions and small communities. They all take place in the modern day, in settings busy with people getting on with everyday life. The best of them are at their most disturbing because they're psychologically real. Women are usually central."The Good Wife" is about a jealous husband who incarcerates his wife. The twist ending reveals that the husband is more monstrous than first supposed, but what lingers is the awful detail of the wife's gradual acquiesence - having clearly tried to resist him to no effect, she now presents nothing but sweetness in the vain hope he will relent. In "The Honeymoon of Mrs Smith", a young bride accepts her imminent murder rather than make a fuss. In "Home", a woman learns better than to speak of the ghostly experience that almost killed her. The horror is not only of passivity, but of the ways these women are rendered passive.

In the brilliant "The Possibility of Evil", a respectable old lady notes the strains affecting her neighbours, before we discover that she's been sending them all anonymous, poisonous letters. Yet there's real tension when this malicious creature unwittingly risks being exposed. Jackson has deftly make us sympathise with the monster.

I'm keen to know more about Jackson and what shaped her extraordinary vision. It's surely no coincidence that her first story, "The Lottery" (not included in this anthology) was first published in 1948, in a post-war world lacking moral certainties - though some readers felt strongly otherwise, and she received death threats in response. I feel something noirish, something Hitchcock, in her stories, something haunted by the Holocaust and the Bomb, something deeply ill at ease with "ordinary" life.

It all feels so very contemporary, but not overtly political. In the final story in the collection, "The Summer People", there's mention of degeneration and inbreeding (p. 183), but the story is about the growing anxiety of an old couple when the local shops are out of groceries and oil. It's so relatable, the horror is horribly real.

I'm keen to see the new film version of We Have Always Lived in the Castle once I've reread Jackson's novel and adore the 1963 film The Haunting (based on The Haunting of Hill House), which first got me reading her stuff in my teens. I've also got a biography of Jackson - so more of this to come.

Published on September 28, 2018 07:14

September 24, 2018

Big Issue #1326

Out today, issue 1326 of the Big Issue features an exclusive interview with Jodie Whittaker about being the new Doctor Who. Lurking alongside that is a small piece by me and Christel Dee about our new book, Doctor Who - The Women Who Lived.

Out today, issue 1326 of the Big Issue features an exclusive interview with Jodie Whittaker about being the new Doctor Who. Lurking alongside that is a small piece by me and Christel Dee about our new book, Doctor Who - The Women Who Lived.

Published on September 24, 2018 11:37

September 23, 2018

Doctor Who Magazine #530

Doctor Who Magazine #530 is now available in shops and online. It includes my interview with musician Christian Erickson about how 1984 Doctor Who story The Caves of Androzani inspired his new album, The Caves - which I've been listening to a lot over the past few months.

Doctor Who Magazine #530 is now available in shops and online. It includes my interview with musician Christian Erickson about how 1984 Doctor Who story The Caves of Androzani inspired his new album, The Caves - which I've been listening to a lot over the past few months.The issue also includes a preview of The Women Who Lived , my new Doctor Who book which is out this week, and a nice review of The Eleventh Doctor Chronicles , which includes my latest Doctor Who audio play.

This issue of Doctor Who Magazine is also available as a deluxe edition exclusive to WHSmith, the goodies including a Doctor Who audio adventure from Big Finish (I'm afraid there's a risk you'll end up with one of mine) and a postcard of Lee Binding's cover art for The Women Who Lived.

I'll be signing the book later this week - at Forbidden Planet in London on Friday evening from 6 pm and at Forbidden Planet in Bristol on Saturday afternoon from 1 pm - along with my co-author Christel Dee and some of the artists involved.

And you can win a copy of the book by paying careful attention to this interview with me and Christel conducted by Phil Hawkins:

Published on September 23, 2018 12:16

September 6, 2018

John Ruskin's Eurythmic Girls, reprise

At 9.15 pm tonight, Radio 3 are repeating a documentary presented by Samira Ahmed and which I produced,

John Ruskin's Eurythmic Girls

, which will then be iPlayer thereafter.

At 9.15 pm tonight, Radio 3 are repeating a documentary presented by Samira Ahmed and which I produced,

John Ruskin's Eurythmic Girls

, which will then be iPlayer thereafter.Listen out for the scene-stealing role played by my then baby daughter. As we set up to record that, the conversation round the table led to an idea that's become our next documentary, which ought to be broadcast in February. More on that anon.

The blurb for tonight's one goes like this:

Perhaps you did music and movement at school. There was a time girls across the country learnt to dance as if they were flowers. At the start of the 20th century, Jacques-Dalcroze developed Eurhythmics to teach the rhythm and structure of music through physical activity. But the idea had earlier roots, including an unlikely champion of women's liberation.

John Ruskin - now derided by feminist critics as a woman-fearing medievalist - was at the centre of a 19th-century education movement that challenged the conventional female role in society. Amid concerns about the health of the British Empire he looked back to the muscular figures in medieval painting and the sculpture of the ancient Greeks, in their loose-fitting clothes. Perhaps the Victorians needed to shed their corsets and free their minds for learning. In Of Queens' Gardens he set out a radical, influential model for girls' education.

Samira Ahmed argues that Ruskin was an accidental feminist. To understand where his ideas came from, how they were enacted and what survives in the way girls are taught today, she ventures into one of the schools set up on Ruskinian principles, tries on the corsetry that restricted Victorian women's lives, and gets the insight of Victorian scholars.

Contributors: Matthew Sweet (author of Inventing the Victorians); Dr Debbie Challis (Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL); Louise Scholz-Conway (Angels Costumes); Dr Fern Riddell (author of A Victorian Guide to Sex); Dr Amara Thornton (Institute of Archaeology, UCL) and Isobel Beynon, Dr Wendy Bird, Annette Haynes, Dr Jean Horton, Diane Maclean, Aoife Morgan Jones and Natasha Rajan at Queenswood School. Readings by Toby Hadoke.

Presenter Samira Ahmed

Producers Simon and Thomas Guerrier

A Whistledown Production for BBC Radio 3.

Published on September 06, 2018 11:23

August 29, 2018

Two Eleventh Doctor things

Michael PickwoadI was very sad to hear of the death of Michael Pickwoad, Doctor Who's brilliant production designer between 2010 and 2017. I've posted my interview with Pickwoad for Doctor Who Magazine in 2014, and hope it conveys his intelligence, warmth and eagerness to help.

Michael PickwoadI was very sad to hear of the death of Michael Pickwoad, Doctor Who's brilliant production designer between 2010 and 2017. I've posted my interview with Pickwoad for Doctor Who Magazine in 2014, and hope it conveys his intelligence, warmth and eagerness to help.I'd been a fan of his for years, and pestered then editor Tom Spilsbury to run a feature on him, whether or not I got to do it. Pickwoad readily accepted, and invited me to the studio at Roath Lock in Cardiff where the series was busy being made - insisting I close my eyes as he led me through a room full of designs for the forthcoming Series 8.

Also, Hero Collector have published a timeline of companion Amy Pond, which I wrote to accompany my feature on her costumes for the first of the Companion Sets from Doctor Who Figurines Collection.

Published on August 29, 2018 12:07

August 21, 2018

Space Odyssey, by Michael Benson

A couple of years ago, I praised a jaw-dropping exhibition of images of the Solar System which were on temporary display at the Natural History Museum. I said Otherworlds was, “brilliantly curated by Michael Benson,” so I eagerly anticipated his new book on the making of the film 2001 to mark its 50th anniversary.

A couple of years ago, I praised a jaw-dropping exhibition of images of the Solar System which were on temporary display at the Natural History Museum. I said Otherworlds was, “brilliantly curated by Michael Benson,” so I eagerly anticipated his new book on the making of the film 2001 to mark its 50th anniversary.Space Odyssey is excellent, detailing the minutiae of each stage in the creative process, from director Stanley Kubrick first making contact with writer Arthur C Clarke to the film’s premiere four years later, its immediate aftermath and the fates of these two men. It is fascinating, insightful and profound – just like the film.

It’s a thrill to follow, step by step, the development of iconic moments – who suggested what and when, and how Kubrick marshalled, encouraged and ran ragged the team around him. Most surprising is how late some of the decisions were made – even deep into cutting, the film almost had a narration and a specially composed score (rather than using pre-existing tracks). On p. 394, we’re told Kubrick even considered getting the Beatles to provide the music. Indeed, the film we know now and I have on Blu-ray is a cut-down, improved version of the one that premiered in New York in April 1968 to such a negative response – effectively, Kubrick was still revising the film after it was finished.

Several of the many, many people Benson interviewed refer to Kubrick as a genius, but the overall impression is of a brilliant, difficult and rather cowardly man. When a real leopard was filmed for the Dawn of Man sequence, Kubrick was the only member of the cast and crew to be inside a protective cage. Worse, we watch in horror as Kubrick insists that stunt performer Bill Weston do longer and longer takes in a spacesuit that Kubrick has also insisted have no holes to prevent the build up of CO2. Weston is rendered unconscious, as has been only too inevitable, and though he recovers Kubrick then avoids him.

There are other things: that Clarke was treated unfairly in contract negotiations, which led to him not getting royalties on the film, and suffered delays in getting the book version approved that didn’t help the delicate state of his finances; the special effects team done out of an Academy Award by Kubrick taking credit for their work. And yet it’s difficult not to admire this difficult, selfish man for his dedication. His approach, his care, his achievement are remarkable.

I found a lot of it funny, such as when (p.91) Kubrick, unsure how to realise the apes in the Dawn of Man sequence, wrote to noted actor Robert Shaw about playing play the lead, unspeaking ape – because he felt Shaw already had simian features. No response is recorded.

Likewise, in the papers drawn up to greenlight the movie, there’s a list of contingency directors. David Lean seems an obvious choice (he hadn’t directed science-fiction before, but then neither had Kubrick), but others are more surprising:

“Try to imagine 2001 – A Space Odyssey directed by [Billy] Wilder, the man who made Some Like it Hot.”The same page also picks out a detail in the contract referring to jurisdictions – the rights to the movie covering not just different countries but extending into space.

Michael Benson, Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C Clarke and the Making of a Masterpiece (2018), p. 90.

“The boilerplate had coincided with the destination.”Benson is an expert guide, though I kept wanting to add prepositions to his wry, dry US journalese. He also feels the need to explain the abbreviation “NB” (p. 66) and that “George the second” was “the eighteenth-century monarch” (p. 224). But then that’s me assuming these things are readily understood, and Benson’s perspective as an outsider gives him a telling insight into the British film industry of the time:

Ibid.

“The British class system was as quietly rigid and unquestioningly enforced at Borehamwood as elsewhere. Offspring of the lower classes were expected to aspire to union cards from the trades; they might become sparks (electricians), chippies (carpenters), plasterers, grips, drivers, and the like. Upper-class kids, on the other hand, could jostle for positions in management and leading creative positions: assistant directors, camera assistants, producers in training.”This is exemplified in the role of posh boy Andrew Birkin – brother of Jane – who starts out as the production’s tea boy and is soon in charge second-unit shooting in Scotland for the Star Gate sequence, taking command of the camera from operator Jack Atcheler, who found the low-flying aerial photography too perilous. (And not without reason; Birkin tells Benson that their helicopter pilot was killed on his next movie (p. 245).)

Ibid., p. 225.

There are odd omissions, too: for all Benson details the relationship between Kubrick and young effects pioneer Douglas Trumbull, there’s no mention of Silent Running (1972), mentioned recently by critic Mark Kermode in his series Secrets of Cinema:

“Trumbull said that he made the unashamedly sentimental Silent Running as a response to the inhuman sterility of 2001 – a film in which the most sympathetic character is a homicidal computer. In Silent Running, Trumbull set his hero [Freeman] alone in space with only three worker drones for company. The drones are robots who, during the course of the movie, come to exhibit strangely human characteristics, or perhaps to reflect the human characteristics which Freeman projects on to them.”And although Benson talks about the influence of 2001 on subsequent science-fiction films, there’s little on the wider cultural impact. I was struck by a small comment when referring to the success of Clarke’s novel of the film.

Mark Kermode’s Secrets of Cinema (BBC Four, 2018) 1.4: Science Fiction

“His other work benefitted as well, with three new printings of Childhood’s End in 1969 alone.”

Benson, p. 435.It’s in this context that Childhood’s End influenced David Bowie’s 1971 song “Oh! You Pretty Things”, which in turn part-inspired the TV series The Tomorrow People. There’s no mention, either, of the conspiracy theory spun out of the technical excellence of 2001’s visual effects: that Kubrick then helped to fake the Moon landings.

One thing Benson does mention is of great interest to something I’m writing at the moment. Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975) won an Academy Award for its cinematography, which included interior scenes,

“illuminated almost entirely by candlelight. The result was the first accurate representation of what eighteenth century interiors looked like before the advent of electricity, giving the film the remarkable aspect of a period oil painting come to life.”This, says Benson, was achieved through the use of fast Leiss lenses with extremely wide apertures, developed for the Apollo programme to photograph the far side of the Moon.

Ibid., p. 438.

It’s this sort of connection that makes the book such an absorbing, astonishing read. But I think the detail that most lingers is a quotation from Clarke’s 1960 essay, “Rocket to the Renaissance”, in which he draws a parallel between space travel and something from history – not the Wild West or even Homer’s Odyssey, but life emerging out of the oceans.

“We seldom stop to think we’re still creatures of the sea, able to leave it only because from birth to death we wear the water-filled space suits of our skins.”• See also: Me on the death and legacy of Arthur C Clarke

Ibid, p. 51.

Doctor Who post script

I’m intrigued by the one reference in the book to Doctor Who. Benson tells us that in the autumn of 1965, in the weeks leading up to the start of filming on 30 December, the spacesuit backpacks, front manoeuvring controllers, button panels for the arms and the space helmets were produced either inhouse at the studios in Borehamwood,

“or by AGM, the London company also busy manufacturing ‘Daleks’: the cylindrical alien cyborgs seen in Doctor Who, the cult BBC-TV series.”Pre-production and the start of filming on 2001 overlapped with the recording of the 12-part The Daleks’ Master Plan on television. We know the team on 2001 contacted director Douglas Camfield a few days after the broadcast of episode 5, Counter Plot, on 11 December 1965 to find out how he’d achieved the space-travelling and molecular dissemination effects.

Ibid., p. 123.

Yet I’d never heard of AGM, so checked with Dalek expert Gav Rymill. “Autumn of ‘65 would have been just before the enormous batch of props made for Daleks Invasion Earth 2150 AD,” says Gav. The Dalek props – for the TV series and the two films – were supplied by Shawcraft, but it’s possible AGM supplied some of the sets or other props used in both TV and films. We shall do more digging...

Published on August 21, 2018 03:08

August 15, 2018

Dickens and the dinosaurs

The online new issue of medical journal The Lancet Psychiatry (vol 5, iss 8, August 2018) features "Dickens and the dinosaurs", a review of the exhibition Charles Dickens: Man of Science, running at the Dickens Museum in London until 11 November.

The online new issue of medical journal The Lancet Psychiatry (vol 5, iss 8, August 2018) features "Dickens and the dinosaurs", a review of the exhibition Charles Dickens: Man of Science, running at the Dickens Museum in London until 11 November.Articles by me for the Lancet

Published on August 15, 2018 01:00

August 14, 2018

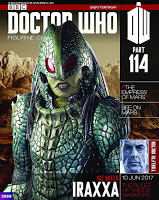

Doctor Who Figurine Collection

I've been working for a while on the partwork

Doctor Who Figurine Collection

, my job to write 1,200 words on the costumes of particular characters from the whole history of Doctor Who, as assigned to me by editor Neil Corry.

I've been working for a while on the partwork

Doctor Who Figurine Collection

, my job to write 1,200 words on the costumes of particular characters from the whole history of Doctor Who, as assigned to me by editor Neil Corry.It's fun and fiddly, involving lots of research and the tracking down of people to interview, as always in the hope of unearthing new detail or insight. For my own record, here are the issues I've done. (I'll try and keep this list updated as we go...)

100 - The Master

Specifically, the significance of the Nehru suit worn by actor Roger Delgado for the Master's first appearance in the opening scenes of Terror of the Autons (1971).

113 - Robot SantasThe modified design from The Runaway Bride (2006), rather than the originals from The Christmas Invasion (2005).

114 - Ice Queen IraxxaFrom The Empress of Mars (2017), including interview with writer Mark Gatiss. I also spoke to Gary Russell and Lee Sullivan about the design of the female Ice Warrior, Shssur Luass, seen in the Doctor Who comic strip published in Radio Times in 1996.

114 - Ice Queen IraxxaFrom The Empress of Mars (2017), including interview with writer Mark Gatiss. I also spoke to Gary Russell and Lee Sullivan about the design of the female Ice Warrior, Shssur Luass, seen in the Doctor Who comic strip published in Radio Times in 1996.115 - Auton

In blue overalls, from Spearhead in Space (1970).

117 - Omega

From Arc of Infinity (1983); I try to uncover why he looks nothing like he did in his previous story, The Three Doctors (1972-3).

118 - Spacesuit Zombie

From Oxygen (2017), including interview with actor Tim Dane Reid.

119 - Emojibot

From Smile (2017), including interview with writer Frank Cottrell-Boyce and SFX producer Kate Walshe.

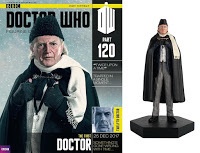

120 - The First Doctor

120 - The First DoctorFrom The Doctor Falls and Twice Upon a Time (2017), including interview with costume designer Hayley Nebauer.

121 - Truth MonkFrom Extremis, The Pyramid at the End of the World and The Lie of the Land (2017), including interviews with actor Tim Dane Reid, SFX producer Kate Walshe and costume designer Hayley Nebauer.

122 - Eliza

From Knock Knock (2017), including interview with sculptor Gary Pollard and SFX producer Kate Walshe.

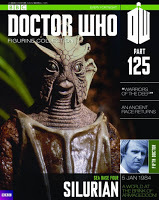

125 - Silurian

125 - SilurianFrom Warriors of the Deep (1984), including excerpts from correspondence from writer Johnny Byrne to fan Sarah Groenewegen in 1983.

126 - The Second Doctor

Specifically, the costume from his first story, The Power of the Daleks (1966).

127 - Winder

From The Beast Below (2010), examining an earlier version of the script.

132 - The Fourth Doctor

Specifically, June Hudson's redesign of the costume for The Leisure Hive (1980). I spoke to Hudson, and also to Ron Davies from Angel's Costumiers, who cut the coat.

Companion set 1 - Amy Pond and The Eleventh Doctor

Covering their costumes between The Eleventh Hour (2010) and The Angels Take Manhattan (2012).

Published on August 14, 2018 02:18

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers

Simon Guerrier isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.