Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 61

March 9, 2018

Bath, Bristol, York

It's British Science Week and tomorrow I'll be talking at the Bath Taps into Science festival on the scientific secrets of Doctor Who - and it's free to come along. I'm on at 2 pm at The Edge, University of Bath.

It's British Science Week and tomorrow I'll be talking at the Bath Taps into Science festival on the scientific secrets of Doctor Who - and it's free to come along. I'm on at 2 pm at The Edge, University of Bath.On Wednesday 14 March, Dr Marek Kukula and I will be speaking at the Basingstoke Discovery Centre, again on the science of Doctor Who. The event starts at 7.30 pm and tickets are £5.

We're also due to speak at the York Festival of Ideas in June - more details of which nearer the time.

Published on March 09, 2018 01:25

March 2, 2018

Dusty Answer, by Rosamond Lehmann

This is a novel of yearning. Judith Earle is an only child, a teenager living a lonely life in a nice house in the Thames Valley. She recalls with a thrill the times in her childhood when the next-door house was home to five cousins, who would sometimes involve her in their games. Looking back to those days with a pang, she longs for them to have noticed her, to have thought well of her, to come back to her again.

This is a novel of yearning. Judith Earle is an only child, a teenager living a lonely life in a nice house in the Thames Valley. She recalls with a thrill the times in her childhood when the next-door house was home to five cousins, who would sometimes involve her in their games. Looking back to those days with a pang, she longs for them to have noticed her, to have thought well of her, to come back to her again.Then there is news: cousins Charlie and Mariella have married, young, and Charlie has gone off to the trenches. There, that beautiful boy is killed, leaving his young wife with a baby she can't quite deal with. The cousins return to the next-door house, and Judith still yearns for their attention. But they're older, sadder, broken - and beset by thoughts of sex. They speak of mistresses rathet than wives. Judith is observed swimming naked in the river, and each of the cousins seems to fall for her in turn over the next few years.

Judith has strong feelings, and is quick to fantasise events to come - at the mention of a cousin's name, she will be consumed by thoughts of how she'll teach or nurse or marry them. There's a sense this longing comes from being so lonely at home - her parents spend most of the book abroad. But there's also a great well of emotion inside her that yearns to be fully expressed.

Then Judith starts at Cambridge, and immediately falls for a fellow student, Jennifer. Their relationship is passionate and loving, and scandalised readers when the book was first published in 1927. But it's surprising, now, how little this three-year affair actually involves. Later, when Judith is carried away by one of the (male) cousins to a secluded spot on an island, we're left with little doubt as to the physical act that occurs - without it ever being spelled out. But between Jennifer and Judith, there's lots of mutual admiration, entertaining friends and gettiing a little tipsy... And that's all. Their kisses might be the kisses of affectionate, platonic friends.

Judith also makes time for a strange, sad girl called Mabel, who everyone else is rude about. On her first day at college, Judith worries that by just making polite conversation with Mabel, the girl will be a burden to her ever after. And though there's an element that Judith is too embarrassed, too cowardly, to break off from Mabel entirely, we also see her kindness and care when Mabel gets into a fix over her exams. Seeing Judith's kindness and compassion make it all the more galling when others are cruel or uncaring to her.

In the last year at university, Jennifer abruptly dumps Judith for another woman, and Lehmann keenly makes us feel the loss. Judith's beloved (if absent) father also dies, and Judith is left in fug of confused, desperate emotions. It's here she encounters the cousins again, swimming naked with Mariella and facing advances of different kinds from the men. One of the cousins treats her particularly badly - using her, then casting her off. We keenly feel the affect this has on Judith, and the risk to her reputation and future should her actions ever be spoken of. And yet she can't stop yearning for those people who have treated her so badly.

For all her misery, Judith is a smart and witty young woman, an accomplished ice-skater, swimmer and student. It is fun to be in her company. But there's a constant feeling, whatever her best efforts, that she's trapped by her class and gender and time. Required to join her widowed mother in Paris after completing her studies, it seems Judith's academic accompishments can only be a hindrance.

"'If you were a little more stupid,' said Mamma, 'you might make a success of a London season even at this late date. You've got the looks. You are stupid - stupid enough, I should think, to ruin all your own chances - but you're not stupid all through. You're like your father: he was a brilliant imbecile. I never intended to put you into the marriage-market - but I'll do so if you like. If you haven't decided to marry one of those young Fyfes... They're quite a good family, I suppose.'"There is more loss to come, and the novel ends with Judith never more alone, and unsure of her future - but also at some kind of epiphany about these people who have so consumed her thoughts and desires for so long. She is still yearning, but not for them. There's just a chance she is free.

Rosamond Lehmann, Dusty Answer (1927), p. 259.

Published on March 02, 2018 04:57

February 27, 2018

The Court Jester

Out now, The Court Jester is the latest volume of The Wife in Space series by Neil & Sue Perryman, in which they watch all of Doctor Who. This one covers the adventures of the Sixth Doctor (1984-1986).

Out now, The Court Jester is the latest volume of The Wife in Space series by Neil & Sue Perryman, in which they watch all of Doctor Who. This one covers the adventures of the Sixth Doctor (1984-1986).I've written the foreword for this volume, which has given me a chance to revisit what it was like to watch these episodes first go out, and to confess my love for Timelash.

Buy The Court Jester (Kindle edition)Adventures with the Wife in SpaceMe on being terrified of Doctor Who in 1985

Published on February 27, 2018 01:19

February 20, 2018

A Legacy of Spies, by John le Carre

"I, who was taught from the cradle to deny, deny and deny again - taught by the very Service that is seeking to drag a confession out me?"

John le Carre, A Legacy of Spies (2017), p. 161.

This is an extraordinary lap of honour, almost a pastiche of le Carre by le Carre himself, the sort of thing in anyone else's hands we would call fan fiction.

This is an extraordinary lap of honour, almost a pastiche of le Carre by le Carre himself, the sort of thing in anyone else's hands we would call fan fiction.It returns us to the world of the Circus and George Smiley, not seen since The Secret Pilgrim (1990), but it's really revisiting the events that led to The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1963) - le Carre's third novel, and the one that made his name. Along the way, we catch up with characters and events from his two other most successful Circus novels - Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974) and Smiley's People (1979). In fact, since this new book is recounted by Smiley's loyal underling, Peter Guillam, I had Michael Jayston's voice in my head (he played Guillam in the BBC adaptations of those latter two novels; Benedict Cumberbatch played Guillam in the more recent Tinker Tailor film.)

A friend had read and enjoyed this new book without knowing any of this history. I'm now eager to reread those other books to see how well it all fits together. It feels seamless, the only glaring thing being Smiley himself - recruited as a spy to the Circus in 1928 or 1937, depending which book you refer to, but still alive and in good health whenever this new, modern-feeling book is set. It is very contemporary, and though the word "Brexit" isn't used, George tells us he is and always was a European, and is horrified by the idea of England on its own as a "citizen of nowhere".

Yet given the age Smiley must surely be, the only concession to the passing of time is that he no longer wears a suit. The one character to have died since we last visited this world is Smiley's nemesis Karla. Jim Prideaux is still working at the same school as he was in Tinker Tailor, more than 40 years ago.

The story sees Guillam called back to London because there's likely to be a parliamentary inquiry into the events of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. He is reticent, but slowly we unpick what happened - a little ahead of the investigators he is speaking to. There's a real sense of menace in the jovial lawyers who seem ready to hang Guillam out to dry, and in the character of Christoph - a man out of revenge. It's an absorbing read, full of well drawn characters and telling detail. Indulgent, but perfectly done.

Published on February 20, 2018 04:59

February 8, 2018

Women & Power - A Manifesto, by Mary Beard

This is a timely publication of two lectures by Mary Beard, one on "The Public Voice of Women" and the efforts to silence them, and the other on "Women in Power." I've long been impressed by the eminent professor's extraordinary patience in dealing with online abuse, from the obscene to the vexatious. Here, she's characteristically considered and considerate in laying out her case that,

This is a timely publication of two lectures by Mary Beard, one on "The Public Voice of Women" and the efforts to silence them, and the other on "Women in Power." I've long been impressed by the eminent professor's extraordinary patience in dealing with online abuse, from the obscene to the vexatious. Here, she's characteristically considered and considerate in laying out her case that,"When it comes to silencing women, Western culture has had thousands of years of practice."Concisely and engagingly, she covers a lot of ground, with references from Penelope in The Odyssey to Professor Holly in Pokemon Farm. Images inform the text, in part because these were originally delivered as lectures but also because Beard has always used non-textual sources to add depth and detail to her examination of history.

Mary Beard, Women and Power - A Manifesto (2017), p. xi.

Some of her more academic books I've found hard to keep up with, but this book is very accessible. That's not to say it's all put very simply - she embraces the complexities and nuances involved. Elizabeth I's speech at Tilbury and Sojourner Truth's "Ain't I a Woman?" would both advance her case, but Beard doubts either woman really spoke the words attributed. She won't take the easy path.

There's much to mull over, whether in relation to politics and public discourse, or applied to my own attitudes and behaviour. Following this example, being more considered and considerate, is not a bad place to start.

But if this is a manifesto, what is the call to action? In her second lecture, she identifies the problem as one of elites holding power over the powerless. Now, various people in the news have been calling out elites for some time, but the danger - especially when wealthy, well-connected politicians claim to be anti-elitist - is that it's about replacing one group in power with another. The system isn't changed and the inequities continue.

Beard concludes her second lecture with the wish to rethink power not as a possession to be fought over, but as a verb, "to power".

"What I have in mind is the ability to be effective, to make a difference in the world, and the right to be taken seriously, together as much as individually. It is power in that sense that many women feel they don't have - and that they want. Why the popular resonance of 'mansplaining' (despite the intense dislike of the term felt by many men?) It hits home for us because it points straight to what it feels like not to be taken seriously: a bit like when I get lectured on Roman history on Twitter."

Ibid., p. 87.

Published on February 08, 2018 08:52

February 2, 2018

Ad Astra: An Illustrated Guide to Leaving the Planet, by Dallas Campbell

This book is a delight, a breezy yet wide-ranging history of humanity's efforts to leave Earth, plus what the near future might hold.

This book is a delight, a breezy yet wide-ranging history of humanity's efforts to leave Earth, plus what the near future might hold.I've read a lot about the exploration of space, and watched a lot of documentaries, too (and written about them here, you poor souls), so am amazed by how much of this book came as new. For one thing, it's wide-ranging, exploring things like who made the flags put up on the Moon by the Apollo astronauts, and how they were constructed given the various physical limitations of the lunar surface and the astronauts' spacesuits.

But there's also plenty where well-documented, well-known material is cast in a new light. For example, the book details the various non-human animals that have been sent into space (a subject I looked into for Horrible Histories Magazine a few years ago). This section concludes with the Russian Zond 5 mission of September 1968, where a probe got to 1950 km of the Moon before returning to Earth. This wasn't new to me, but then the book contrasts the pair of tortoises on board (alongside other creatures) to the "nimble hare" of the human-crewed Apollo 8, launched two months later.

It's packed with detail, a lot of it strange and surprising. As a presenter of science programmes on TV, the author has had direct access to some extraordinary people and places. And the book is all told in short, pithy chunks so what's a complex, technical subject is never too heavy or dry. The text is presented beautifully, with lots of well-chosen photographs, documents and curios.

I especially loved how seamlessly the hotch-potch collection is brought together. My favourite, I think, is where we're told that since, obviously, there is no facility to develop camera film in space, in 1964, Robert Leighton's team at JPL conceived and built the first ever digital camera. The cost, given it could take 22 images (of 200 x 200 pixels each), averaged out at $3.8 million per picture.

We then follow this invention being put on Mariner 3 (where something went wrong and the probe was lost to space) and its twin Mariner 4, which launched on 28 November 1964 and reached Mars the following July. Then we get the awful wait for the pictures it took - the first pictures of Mars taken in space - to transmit back to Earth.

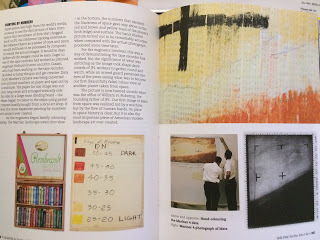

We're told how Richard Grumm, an engineer, John Casani, who'd worked on the recording system, got ahead of the process by printing out the raw data from Mariner's camera as it arrived, arranging it in row after row of three-digit numbers, and colouring in these numbers, by hand, with crayons from a local art shop: 050-045 in brown, 045-040 in red, 040-35 in orange, etc.

Accompanying the concise text, there are photographs of the box of crayons, of the chart assigning colours to numbers, of a close-up of the work, and of the actual photograph that was slowly downloaded.

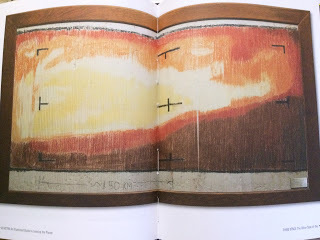

Ad Astra by Dallas Campbell, pp. 206-7.And then you turn the page and there's a double page spread of the hand-coloured version - a breath-taking juxtaposition in one object, one artwork, of cutting-edge science and childlike simplicity.

Ad Astra by Dallas Campbell, pp. 206-7.And then you turn the page and there's a double page spread of the hand-coloured version - a breath-taking juxtaposition in one object, one artwork, of cutting-edge science and childlike simplicity. Ad Astra by Dallas Campbell, pp. 208-9.In all, this is a perfectly curated and comprehensive handbook. It inspires awe, and makes clear how very difficult and dangerous it will be to return people to the Moon and then go further - and how close and inevitable it is that we do.

Ad Astra by Dallas Campbell, pp. 208-9.In all, this is a perfectly curated and comprehensive handbook. It inspires awe, and makes clear how very difficult and dangerous it will be to return people to the Moon and then go further - and how close and inevitable it is that we do.

Published on February 02, 2018 12:53

January 31, 2018

St Mary's, Ickworth - inspiration for the Weeping Angels

Last summer, then big chief of Doctor Who, Steven Moffat, explained to me his inspiration for the most successful of his monsters, the Weeping Angels:

John Porter, director of the Ickworth Church Conservation Trust, invited me to come see for myself. It was a 180-mile round trip, and I chose to visit the same day as a Wood Fair in the surrounding National Trust grounds, which made it a little crowded and busy. But the church was easy to find and John kindly gave me a tour. These are some of the pictures I took:

As I wrote in my piece:

As I wrote in my piece:

The angels had the phone box (in Kensal Green)Me on Blink

"We were at a hotel in Dorset and there was a graveyard next to the hotel. The church was closed down and the graveyard gates were all chained up with a big sign saying, 'Unsafe structure.' That seemed really frightening. I went over and looked inside, and saw all these leaning gravestones and one lamenting, weeping angel. I thought that was really creepy and strange, and wondered if that was the unsafe structure. So a few years later I wrote it up as [2007 episode] Blink, including the chained-up gate which we had at the very beginning." [From my interview with Steven Moffat]In September, Marcus Hearn at Doctor Who Magazine asked me to write something about Blink for a new special issue, The Essential Doctor Who - Time Travel, published in November. I asked Steven to confirm the hotel he'd stayed in all those years ago, so I could track down that church. It turned out not be to be in Dorset after all. He directed me to the Ickworth Hotel in Suffolk, and said the abandoned church was right next to it.

John Porter, director of the Ickworth Church Conservation Trust, invited me to come see for myself. It was a 180-mile round trip, and I chose to visit the same day as a Wood Fair in the surrounding National Trust grounds, which made it a little crowded and busy. But the church was easy to find and John kindly gave me a tour. These are some of the pictures I took:

As I wrote in my piece:

As I wrote in my piece:"Sadly, there’s no lamenting angel statue in the churchyard today. Gargoyles stretch out from the top of the church tower, and some of the graves are carved with cherubs – like those seen in Steven’s 2012 episode The Angels Take Manhattan – or skulls. Stacked neatly against one wall, a broken-off stone crucifix and other pieces suggest that some monuments did not survive the period of neglect.Steven had also been back to the church since creating the Weeping Angels. As he told me,

Though John hadn’t heard of there being an angel statue in the churchyard, he admits that doesn’t mean there wasn’t one. He shows me the church’s impressive eighteenth-century chancel boards and explains they were saved at the last moment from a skip. “Who knows what was thrown away?” he says. Perhaps the original weeping angel wasn’t thought worthy of salvation."

"It was gone – oh no! Now, there are two possible explanations. One is that Weeping Angels are real and we're all doomed – unless a moth sees them. Or, I misremembered and in my fake memory created the Weeping Angel in that graveyard."See also:

The angels had the phone box (in Kensal Green)Me on Blink

Published on January 31, 2018 11:38

January 24, 2018

Geis - A Game Without Rules by Alexis Deacon

A Game Without Rules (2017) continues the beguiling story begun in Geis - A Matter of Life and Death (2016), the extraordinary, beautiful graphic novel by Alexis Deacon.

A Game Without Rules (2017) continues the beguiling story begun in Geis - A Matter of Life and Death (2016), the extraordinary, beautiful graphic novel by Alexis Deacon.When the chief matriarch dies without an heir, a contest is held to find a new ruler for the island state. Fifty contestants - some of them the least likely competitors - then begin some peculiar and deadly games...

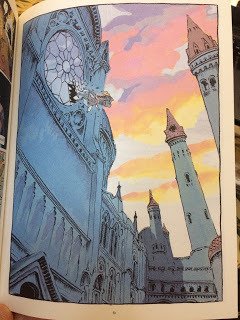

Page 81 of Geis - A Game Without Rules

Page 81 of Geis - A Game Without Rulesby Alexis DeaconI've followed Alexis' career for some time as we have a mutual friend (who introduced us, very briefly, late last year because I asked). His books for younger children - Slow Loris , I Am Henry Finch - have been favourites of the Lord of Chaos.

Geis is aimed at older readers and presents an absorbing, rich fantasy world full of strangeness and horror and magic. I meant to post here in praise of the first volume but only got so far as a tweet:

"Geis by Alexis Deacon is great: eerie, epic

"Geis by Alexis Deacon is great: eerie, epicfantasy like a fairy tale twisting wrong. Plus

people wear amusingly shaped hats."

The second volume is just as enthralling, full of the same dream-like disquiet and sudden shocking turns - and those excellent hats. The characters from the first book are caught up in games and plots they barely understand, and which not all of them survive. The violence is implied rather than shown, but the beautiful artwork and lightness of touch in the storytelling are underpinned by constant, real threat. A book that compels you to read on.

I eagerly anticipate the third volume, The Will That Shapes The World. You can see more artwork from Geis on Alexis Deacon's website.

Published on January 24, 2018 01:44

January 21, 2018

The Spy Who Loved by Clare Mulley

This life of SOE agent "Christine Granville" - born Maria Krystyna Janina Skarbek in Poland in 1908 - took a while to get in to, not least because it's so dense with meticulous research. There is lots on the frustrations and false starts of a life running messages under Nazi noses, on the bureaucracy and "office politics" of rival intelligence factions, and on her tangled love life.

This life of SOE agent "Christine Granville" - born Maria Krystyna Janina Skarbek in Poland in 1908 - took a while to get in to, not least because it's so dense with meticulous research. There is lots on the frustrations and false starts of a life running messages under Nazi noses, on the bureaucracy and "office politics" of rival intelligence factions, and on her tangled love life.Peppered with good moments, it then really picks up once the firm (as SOE was known to its employees) finally gives Christine something to do, dropping her blind (without help) into France. She's brave, resourceful and charismatic, and it's thrilling to be at her side in the thick of the action. The odds against her and her comrades make these chapters utterly compelling - particularly the Nazi attack on Vercors, and Christine's attempts to rescue comrades when they're arrested and sentenced to death. Later, the Warsaw Uprising is just as deftly conveyed - Christine wasn't there, but we're haunted by the dreadful events just as she was.

We feel Christine's righteous anger when artillery is not dropped to the desperate resistance fighters in Vercors and Warsaw, despite repeated and urgent requests. There's also her justifiable fury at being constantly overlooked - a mix of sexism, xenophobia, Antisemitism and office politics. After the war, despite distinguished service and the support of such figures as Lord Selbourne - who appealed directly to the Home Secretary on her behalf - Christine was still denied British citizenship. In fact, says Mulley,

"it now turned out that Christine's service to Britain was irrelevant, because she was not a man. 'A married woman is disbarred, under the present law, from obtaining naturalisation independently from her husband...' a rubber-stamping official explained. Without evidence of [her husband] Jerzy Gizycki's death or a valid dissolution of his and Christine's marriage, the Home Office simply saw 'no point in considering whether she could be regarded as eligible in other respects'. Over six million Poles had died during the war, there were few official records, and Christine was in any case disbarred from returning to Poland because of her service for the Allies, but her marital status was more important than her war record. It was a low moment for Home Office policymakers."She felt the firm had also let her down, failing to find her suitable work after the war. She's a restless woman of action who doesn't fit easily in peacetime, and SOE was itself closed down at the end of the war. Christine didn't exactly help herself - she was spiky and rude, and refused to take on administrative or secretarial duties - but it's hard not to share her anger.

Clare Mulley, The Spy Who Loved (2013), p. 289.

"'I am rather tired, after six years of more or less active service with the firm,' she wrote bitterly, 'of being treated as a helpless little girl.'We follow her efforts to find a place for herself post-war: a spell farming in Kenya; visiting a friend in Germany but too disquieted about being in enemy territory; working on passenger liners. And then too quickly it's over - shockingly, awfully, in July 1952 Christine was murdered by a jilted admirer.

Ibid., p. 294.

Mulley is also good at picking through the accounts of Christine's life, weighing up their claims. She spells out the case for Christine having inspired Vesper Lynd in Casino Royale - written a few months before Christine's death. It seems quite convincing an idea until Mulley then unpicks it: there's no strong evidence Christine actually ever met Ian Fleming.

An epilogue detailing how Christine's friends tried to protect her reputation after her death is concise and moving. Mulley then offers a note on how she went about collating this story - from an extraordinary range of sources.

But the book then ends on a sour note, with one appendix speculating on why Christine never had or seemed to want children, and then another other giving more detail about her murderer. They're surely appendices because they don't fit with what's gone before, and there's a feeling of prurience, even disrespect to the difficult, brilliant agent who deserved something more.

See also: Nevil Shute's Requiem for a Wren

Published on January 21, 2018 13:18

January 10, 2018

Shaggy

This morning, the Dr and I took our poorly, frail cat Shaggy to the vet one last time, where he was quietly put to sleep. It was quick. It has all been horribly, mercifully quick.

This morning, the Dr and I took our poorly, frail cat Shaggy to the vet one last time, where he was quietly put to sleep. It was quick. It has all been horribly, mercifully quick.For months now, he’s been losing weight and confidence, no longer daring to go outside in the cold and wet, let alone to brave the domains of Other Cats that he once kept in line. Then, in the last few weeks, he’s taken a sudden turn for the worse and been miserable, too. This morning, there was no fight to get him into his carrier, no resistance at all.

Thirteen and a half years ago, Shaggy was my wedding present to the Dr. Growing up, she’d not had any pets but could never pass a cat in the street without stopping to say hello (she still can’t). The day after we got back from honeymoon, on 14 July 2004, we headed to what’s now Battersea Dogs & Cats Home.

Thirteen and a half years ago, Shaggy was my wedding present to the Dr. Growing up, she’d not had any pets but could never pass a cat in the street without stopping to say hello (she still can’t). The day after we got back from honeymoon, on 14 July 2004, we headed to what’s now Battersea Dogs & Cats Home.The Dr was jumpy with excitement, so my role was to be the cool, collected one. I reminded her on our way in that we’d been warned not to expect to take a cat home that first day. No, this was just the start of the process. We were interviewed about our past experience with pets (I grew up with cats, dogs and chickens), about the kind of home we could provide and whether there were dangers such as nearby busy roads. They concluded we needed a nice “entry-level” pet. There was a colour-coded system: we were told to look for green cats.

Then we were led upstairs to where the cats were waiting. They were all in individual hutches, inset into the wall floor to ceiling, each with a card giving details of their temperament and background. Older, crosser cats had red stickers. One particularly furious red beast glared at us from its cell. The yellow cats did a better job of imploring us to love them. The green cats hardly seemed to notice us at all.

As instructed, we looked at the green cats. They were… cats. All very nice but nothing exactly suggestive of how we were meant to choose.

Then they let some green cats out, one at a time, so we could get a better idea. One dark-haired cat with both green and yellow stickers was set down on the floor and wandered nonchalantly off, barely glancing our way. The Dr had his card and asked why he’d been called “Shaggy”. The person showing us round grinned and clapped her hands. It made us jump – and Shaggy, too. His thick, long hair all stood up on end, an endearing scruffy mess.

Then they let some green cats out, one at a time, so we could get a better idea. One dark-haired cat with both green and yellow stickers was set down on the floor and wandered nonchalantly off, barely glancing our way. The Dr had his card and asked why he’d been called “Shaggy”. The person showing us round grinned and clapped her hands. It made us jump – and Shaggy, too. His thick, long hair all stood up on end, an endearing scruffy mess.Sensing our interest in this ridiculous creature, it was suggested we pick him up. The Dr was nervous, so I went first. Shaggy immediately collapsed into my arms, snuggling up like a baby. That did it for my cool composure.

Now it seemed that we might get to take this purring fur-bag home with us that same day. That was, if we could sign all the paperwork and buy up all the equipment we needed before Battersea closed for the evening. There was a bit of a scramble and some crossed wires, but finally we were in our cab home – cradling our new cat.

Now it seemed that we might get to take this purring fur-bag home with us that same day. That was, if we could sign all the paperwork and buy up all the equipment we needed before Battersea closed for the evening. There was a bit of a scramble and some crossed wires, but finally we were in our cab home – cradling our new cat. Back home, we did as instructed and shut ourselves in one room before letting Shaggy out of his carrier. The idea was not to scare him with too much at once: he could get used to one room at a time. (Years later, our surviving cat, Stevens, was so terrified on her first evening with us that she spent the night clinging to the top of a door, and only came down to pee all over the floor.)

Back home, we did as instructed and shut ourselves in one room before letting Shaggy out of his carrier. The idea was not to scare him with too much at once: he could get used to one room at a time. (Years later, our surviving cat, Stevens, was so terrified on her first evening with us that she spent the night clinging to the top of a door, and only came down to pee all over the floor.)Shaggy was never shy. He immediately took charge of the room – our bedroom – and was then scratching at the door. Within an hour or so he’d taken charge of our flat. And that night, we were woken by his happy howls on discovering the mouse problem we’d inherited from our previous tenants. Shaggy, for all he was a beautiful, soft fluffball, was a very practical mouser.

He was always a character. When one friend came round to meet him, Shaggy playfully climbed on to a potted plant in the front room and – brazenly staring all of us out – proceeded to crap in it. He was fascinated by frogs, scooping them up from the old pond at the end of the garden and bringing them into show us them leaping around. When the Dr was bedridden with sickness, he helpfully dropped a frog on her head.

He was always a character. When one friend came round to meet him, Shaggy playfully climbed on to a potted plant in the front room and – brazenly staring all of us out – proceeded to crap in it. He was fascinated by frogs, scooping them up from the old pond at the end of the garden and bringing them into show us them leaping around. When the Dr was bedridden with sickness, he helpfully dropped a frog on her head. In short, we’d hoped for a good entry-level cat and Shaggy was magnificent. Affectionate, cheeky and rarely ill until these last few weeks, he’s given us a very easy ride. He’s been quick to warm to friends and neighbours (I discovered he’d been getting second breakfasts across the road each morning). More than that, he’s seen us – the Dr especially – through plenty of tough times over the years, always knowing when to pad softly over for a cuddle and that deep bass purr.

In short, we’d hoped for a good entry-level cat and Shaggy was magnificent. Affectionate, cheeky and rarely ill until these last few weeks, he’s given us a very easy ride. He’s been quick to warm to friends and neighbours (I discovered he’d been getting second breakfasts across the road each morning). More than that, he’s seen us – the Dr especially – through plenty of tough times over the years, always knowing when to pad softly over for a cuddle and that deep bass purr. He had such a close bond with the Dr that we worried how he might respond to children, and so got a second cat in part to prepare him. But Shaggy was just as affectionate with the interloper cats and then with the children, snuggling up to them and suffering their clumsy but well-meant attention. One friend used to guarantee good behaviour from his daughter with the promise of visiting Shaggy.

He had such a close bond with the Dr that we worried how he might respond to children, and so got a second cat in part to prepare him. But Shaggy was just as affectionate with the interloper cats and then with the children, snuggling up to them and suffering their clumsy but well-meant attention. One friend used to guarantee good behaviour from his daughter with the promise of visiting Shaggy. For our own Lord of Chaos, Shaggy has always been part of the family, and they had one last cuddle this morning before school. His name is one of Lady Vader’s few but well-practised words. It’s hard to tell how much they take in what’s been happening or how it will affect them. I suspect the main issue they’ll have to deal with is their tender parents.

For our own Lord of Chaos, Shaggy has always been part of the family, and they had one last cuddle this morning before school. His name is one of Lady Vader’s few but well-practised words. It’s hard to tell how much they take in what’s been happening or how it will affect them. I suspect the main issue they’ll have to deal with is their tender parents. We knew Shaggy was getting on in years. He was a kittenish 15 months-old when we acquired him so would have been coming up to 15 years now, somewhere between 75 and 90 depending how you calculate cat years. That’s not a bad age, and it’s not been a bad life – doted on by the Dr and spoilt rotten when I wasn’t looking. You could tell when he wasn’t happy, and that’s been mostly rare: when we didn’t share prawns or tuna; when we were ever packing a bag he couldn’t climb into; in his long war of passive aggression against my mother-in-law; in these last few weeks.

We knew Shaggy was getting on in years. He was a kittenish 15 months-old when we acquired him so would have been coming up to 15 years now, somewhere between 75 and 90 depending how you calculate cat years. That’s not a bad age, and it’s not been a bad life – doted on by the Dr and spoilt rotten when I wasn’t looking. You could tell when he wasn’t happy, and that’s been mostly rare: when we didn’t share prawns or tuna; when we were ever packing a bag he couldn’t climb into; in his long war of passive aggression against my mother-in-law; in these last few weeks.This morning the Dr and I went with him to the vet, and soon it was all over. We buried him with his favourite pink mouse toy in the garden, in the corner he’d always made his own because it caught the sun.

Published on January 10, 2018 03:47

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers

Simon Guerrier isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.