Simon Guerrier's Blog

October 2, 2025

Barry Cryer Same Time Tomorrow, by Bob Cryer

This is a lovely, funny and often moving biography of the comedian Barry Cryer (1935-2022) written by his youngest son. Each chapter is preceded by one of Cryer’s well-worn jokes, which I could easily hear in his distinctive, warm gravel tones. There are more great jokes peppered through the text, as well of bits of showbiz history and gossip.

This is a lovely, funny and often moving biography of the comedian Barry Cryer (1935-2022) written by his youngest son. Each chapter is preceded by one of Cryer’s well-worn jokes, which I could easily hear in his distinctive, warm gravel tones. There are more great jokes peppered through the text, as well of bits of showbiz history and gossip. There are, too, some shocking moments such as the time Cryer tried to end his own life and was saved by his neighbour Douglas Camfield — then assistant floor manager on TV shows such as Garry Halliday and later a celebrated director on Doctor Who and other drama. But really this is a history of a hardworking, professional writer and performer plugging away at his trade as the entertainment world changed around him.

In early 1961, while still relatively green, Cryer and his friend Ted Dicks (no relation to Terrance, though their credits sometimes get muddled up) began writing for revue show This is Your Night Life. The show was headed by Danny La Rue, who we’re told described himself as a “female impersonator” rather than “drag artist”, and it was performed at Winston’s nightclub in London where La Rue had been in residence for some years.

“Shows usually started at 12.45 am, meaning they often finished around 3 am. Almost all the performers, including Danny, had jobs in other West End shows and came to Winston’s afterwards” (p. 108)

The cast of This is Your Night Life included Terry Donovan, who Cryer married in 1962. Their son describes them cycling from their home in Maida Vale to rehearsals for Danny La Rue during the day. Terry would then cycle to her evening show in the West End and her husband would be off to a stand-up gig at the Players’ Theatre. They’d then head to Winston’s for 11 pm for their next performance, get home in the not-so-small hours and then do it all again, night after night after night. It’s exhausting and thrilling and mad. You can smell the cigarette smoke and tiredness.

Cryer Jnr says his dad was an almost perfect match for revue shows of this kind, given the OED’s definition of revue as “a light theatrical entertainment consisting of a series of short sketches, songs, and dances, typically dealing satirically with topical issues.” The fit was almost perfect because, “to my knowledge Strictly Come Dancing never called” (p. 78).

To Cryer Jnr, that’s because revue matched his father’s love of “professional amateurism”, that mix of spontaneity and chaos where it seems as if the wheels might come off at any moment. I know exactly what he means, having grown up on Cryer Snr’s work with Kenny Everett on TV and hearing him on I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue on the radio. In fact, Cryer Jnr is good on why the late-night revue show on stage morphed into the panel show on radio and TV.

“The Theatres Act of 1968 meant that the Lord Chamberlain no longer had the power to censor the West End and a new kind of liberated and more confrontational voice was now being heard. Innuendo, that great staple of cabaret and Danny’s nightclub shows, not to mention one of Dad’s great weapons (if you pardon the, ahem, innuendo), was now seen as quite quaint.” (p. 174)

The panel show, and Kenny Everett, allowed the informal, wheels-coming-off to continue in new guise.

Given Cryer Snr’s prolific career, of the many shows in different media mentioned in the book there’s a single, brief reference on page 182 to Better Late…, a revue show broadcast over nine weeks on BBC Radio 4 in the summer of 1970, filling the gap while Any Answers? was on holiday.

By Cryer Jnr’s reckoning of revue shows as given above, that mean it was a bit quaint, though BBC’s audience research reports from the time suggests that listeners were still uncomfortable — even outraged — to hear politicians being very lightly mocked.

Cryer didn’t write for the series; he was one of the performers led by Peter Reeves. Reeves also co-wrote the scripts with his friend Terrance Dicks — NB not, this time, Ted.

So, here’s some of what I can add about this long-forgotten revue show:

Better Late… was a kind of summer holiday for Terrance, who’d just completed work as script editor on Jon Pertwee’s first series as Doctor Who — the final episode of closing story Inferno, directed by Douglas Camfield (and, uncredited, by Barry Letts) was recorded on 29 May and went out on 20 June. Terrance duly commissioned scripts for the next series of Doctor Who and must have co-written this revue show while waiting for those scripts to come in.

On Tuesday 7 July, Robert Holmes delivered his scripts for what was then called The Spray of Death, the debut story of Doctor Who’s 1971 series. The following day, Reeves, Cryer, Elizabeth Morgan and Bill Wallis, with producer John Dyas and I assume co-writer Terrance, rehearsed the first episode of Better Late… ahead of recording in the Paris studio at BBC Broadcasting House that evening, accompanied by the Max Harris Group and announcer David Dunhill. The show went out at 7.30 pm the following evening.

The pattern was basically the same for the next eight weeks.

Sadly, Better Late… no longer survives in audio form but the scripts are (mostly) held by the BBC’s Written Archives Centres. Since the revue show was topical, a lot of the material must have been written the week of recording and transmission, and skips in page numbering on surviving script pages suggests that a lot more material was written than used. The scripts also include many handwritten rewrites — refinements and rephrasings, whole jokes added or cut, the swapping of roles between performers. The sense is of a lot of work, right up to the last possible moment.

Terrance formally accepted draft scripts from Don Houghton for what was then called The Pandora Machine — the second story of the 1971 run of Doctor Who — on 2 September, the same day he was in rehearsals on the ninth and final episode of Better Late… The following week, finished on Better Late..., he completed edits on the scripts for The Spray of Death so it could go into production, received a storyline from Malcolm Hulke for the third story in the run, and commissioned Bob Baker and Dave Martin to write scripts for the fourth story.

So, he finished work on the 1970 series of Doctor Who, which had been something of an ordeal, plunged into this demanding radio series and then went straight back to Doctor Who. Exhausting, thrilling, mad!

October 1, 2025

Social Care Today report: People First With AI and Tech-Enabled Care

I did some work on the new Social Care Today special report, People First With AI and Tech-Enabled Care, now available to download for free.

I did some work on the new Social Care Today special report, People First With AI and Tech-Enabled Care, now available to download for free.The report includes my interview with Luke Geoghegan, Head of Policy and Research at the British Association of Social Workers (BASW) about the way AI is already changing the provision of social work and care. A longer version of the interview is available on the SCT website.

There is also an interview with William Flint, Director of Bluebird Care NEW Devon, who oversaw a trial of the Access Assure system of discreet sensors in the home that monitors a person’s activity and is able to recognise anything out of the routine.

Other case studies in the report include the rollout of Cassius by Suffolk County Council, the Dorothy app designed to support people living with dementia and the Earzz acoustic monitoring system.

September 30, 2025

Penda’s Fen Scene by Scene, by Ian Greaves

This is an impressively detailed, close analysis of compellingly nuts and unsettling TV film Penda’s Fen, originally broadcast on BBC-1 on the evening of 21 March 1974.

This is an impressively detailed, close analysis of compellingly nuts and unsettling TV film Penda’s Fen, originally broadcast on BBC-1 on the evening of 21 March 1974. Ian Greaves — a friend for decades and now a stablemate at Ten Acre Books — devotes a chapter to each of the 27 scenes in the play, in order. He carefully compares different drafts of script and other sources, with new testimony from cast and crew. Many of these chapters are followed by ‘Interludes’ that explore a topic in further depth — for example, the role of Sir Edward Elgar and his music, the history of one of Rudkin’s other plays (for radio), or biographies of leading figures in the cast and crew.

Of the latter, I was blown away by the extraordinary life and output of producer David Rose. I’ve often seen his name attached to compelling works of drama but Ian lays out how brilliant he was at facilitating good work from others.

“In every anecdote about him, the wording and circumstances may vary, but they each tell the same story — of his light touch, his willingness to delegate, to enable good work, and above all to trust and empower those around him” (p. 123)

What an epitaph!

The scene-by-scene analysis so brilliantly done, full of top facts and smart insight. Then the last chapter, on the context of transmission, is a revelation.

How extraordinary to see this weird film in the context of the otherwise mundane TV that day or broadcast, in the context of the oil crisis, in the context of everything else. We understand what Penda’s Fen is and its impacts, the mixed reactions to it at the time and after, by knowing what it sat amidst in the schedule and in people’s lives.

Ian then continue this, to cover repeat screenings and the sharing of the play on video among jitter-fingered fans. So often, analysis of a particular TV programme or film sees its subject as a discreet unit, cut off from context. A film of this sort gets labelled as “folk horror” and bracketed with other stuff of what is seen as a similar type. But that excises what made this so strange and jarring: it wasn’t like anything around it. By wading into that context, Ian makes Penda's Fen even more odd and interesting.

I read the book a little guiltily, as it’s unrelated to the huge heap of work I need to get done on my forthcoming biography of Terrance Dicks (who was at the time that Penda’s Fen was first broadcast just coming to the end of his full-time job with the BBC as script editor of Doctor Who). And yet there are overlaps here.

For example, on p. 151 Ian identifies two special effects shots in the play as the work of Bernard Lodge, who got the job in September 1973 and applied made use of his own version of the ‘slit scan’ technique from the end of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Of course, this was at just the same time that Lodge was also using the same technique to create the new opening title sequence for Doctor Who.

That prompted me to look at the transmission of Penda’s Fen in the context of Doctor Who. Of no interest to anyone but me, it went out in the week between Part Four of Death to the Daleks and Part One of The Monster of Peladon. That was also the week in which the novelisations Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon and Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks were meant to be published; the archive of the Official Doctor Who Fan Club of the time suggests that both books were delayed until July.

One of the things Ian discusses in the book is that Penda’s Fen was never expected to be repeated; viewers would have to make up their minds about its strange, opaque meanings from a single viewing. That’s true of those working on Doctor Who in the same period. These things are, quite by accident beyond the cast and crew, ephemera that has endured for half a century now, while so much of the stuff around it has long faded.

September 29, 2025

The Heartless Sea

Big Finish have announced another new Doctor Who audio play I've written, to be released in February 2026.

Big Finish have announced another new Doctor Who audio play I've written, to be released in February 2026.

The Heartless Sea by Simon Guerrier

As Harry Sullivan and Naomi Cross investigate the apparently haunted “Warehouse 9”, they come across someone who they didn’t expect to meet – the Doctor! But one who hasn’t met them yet… and soon after they find themselves dealing with the wrath of the most furious sea there has ever been.

The story is part of Companion Chronicles: The Legacy of Time, paired up with a story called The Kraken of Hagwell by Barbara Hambly. What a thrill to be teamed up with Barbara, who I've sat on panels with at conventions.

The Heartless Sea stars Michael Troughton as Doctor Who, Eleanor Crooks as Naomi and Christopher Naylor as Harry. It is directed by Nicholas Briggs and produced by Dominic G Martin.

September 26, 2025

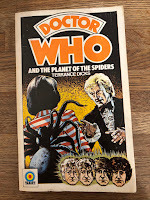

Doctor Who and the Planet of the Spiders, by Terrance Dicks

Peter Brookes’s cover artwork for this Doctor Who novelisation has haunted me since I first saw it, aged four. It was one of 16 covers featured, in colour, on the back of the Doctor Who Monster Book (1975) — which I’ll blog about in due course.* Of all of those books, this was the one I most pined for, because of the extraordinary cover. A book where you see the Doctor change…

Peter Brookes’s cover artwork for this Doctor Who novelisation has haunted me since I first saw it, aged four. It was one of 16 covers featured, in colour, on the back of the Doctor Who Monster Book (1975) — which I’ll blog about in due course.* Of all of those books, this was the one I most pined for, because of the extraordinary cover. A book where you see the Doctor change…Following the pattern of his covers for Doctor Who and the Giant Robot and Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons, Brookes focused the main part of the full-frame image on the story’s titular monster. Again as before, he shows a moment from very late in the story — in this case, the giant spider being revealed on Sarah’s back occurs on p. 106, just 15 pages from the end.

The inset image at the bottom of the frame happens even later. In fact, it happens beyond the pages of this book. Here’s how Terrance Dicks concludes his novelisation:

“‘Brigadier, look!’ said Sarah. ‘It’s starting.’

A golden glow was spreading round the Doctor’s body. Even as they watched, the features began to blur and change. ‘Well bless my soul,’ said the Brigadier. ‘Here we go again!’ (p. 120)

Note that we witness here only the beginning of the regenerative process. Unlike on TV, there is no glimpse of the new Doctor and, unusually for Terrance, no pithy, one-line description to distinguish this incarnation (“all teeth and curls”, as Terrance later put it).

I think that’s because there was simply no need. The new Doctor’s face is featured on the cover, in the regeneration montage. Besides, when this book came out the new Doctor needed no introduction.

This book was published on Thursday, 16 October 1975, two days before the final part of Planet of Evil went out on TV, the 27th of 35 new episodes of Doctor Who broadcast that calendar year, all starring this new Doctor. He’d also appeared, in character, on Disney Time and Jim’ll Fix It, and switched on the Blackpool Illuminations. Everyone knew what he looked like.

The back-cover blurb of the novelisation also focuses on the climactic moment of change, but provides a subtly different version:

“‘It’s happening, Brigadier! It’s happening!’ Sarah cried out. The Brigadier watched, fascinated, as the lifeless body of his old friend and companion, Dr Who, suddenly began to glow with an eerie golden light… The features were blurring, changing… ‘Well, bless my soul,’ said the Brigadier. ‘WHO will be next?’

Read the last exciting adventure of DR WHO’s 3rd Incarnation!”

Note that the text inside the book itself doesn’t answer the Brigadier’s question. The blurb also makes the Brigadier’s response fascinated rather than eyebrow-arching wry, and says the Doctor is his companion rather than the other way round. I don’t think Terrance wrote this.

But the golden light, and the “features” that blur and then change, are consistent in both versions. The implication, surely, is that Terrance delivered his manuscript and then Target editor Mike Glover or his assistant Liz Godfray reworked the last paragraph to make it function as a blurb. Their version may not match the text of the novelisation, and departs even further from what was seen on TV, but it’s also more active: “happening” rather than “starting”, and all at once fascinating, sudden and eerie.

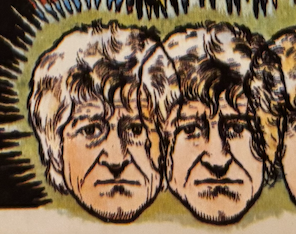

The four-step regeneration shown on the cover surely owes something to an image from almost a year before: the four-step photo montage featured in Radio Times in December 1974 to promote the new Doctor’s debut in Part One of Robot.

But that montage, in turn, surely derives from Peter Brookes’s own artwork for the Radio Times special marking the 10th anniversary of Doctor Who, published a year previously in December 1973. This shows seven ages of the Doctor: a four-step regeneration from the First to Second Doctor, and a four-step regeneration from the Second to Third.

In revisiting this idea for Doctor Who and the Planet of the Spiders, Brookes used the same composition, with each new face overlapping the last. The spacing between iterations is the same. Look, for example, at the final two faces in the Radio Times illustration:

The right-hand edge of the left-hand Doctor — i.e. his hairline — just meets the left-hand side of the next Doctor’s left eye. It’s the same with the first two faces on the book cover:

The book cover is smaller than the Radio Times illustration and correspondingly less detailed. It’s also less atmospherically lit and the Doctor’s gaze less piercing. Though the main and inset images of Jon Pertwee’s Third Doctor are good, the likeness of Tom Baker is not.

Unfortunately, what we see here is an improved version of the Fourth Doctor. Brookes’ preparatory sketch was worse, prompting Doctor Who producer Philip Hinchcliffe to complain to Target on 1 May 1975 — five and a half months ahead of publication, giving us a sense of of lead times on these books. The production team provided Brookes with more photographs of Baker, from which the artists produced the cover as seen on the book. (Source for this: The Target Book, p. 29, the sketch reproduced on p. 34).

Brookes did not work for the Target range again. From the next novelisation, Chris Achilleos was pressed back into service — more on that next time.* I raise this not to criticise Brookes (I really love this cover!) but it strikes me that he wasn’t the only one to depart the Target range following complaints about the artwork.

Barry Letts — Hinchcliffe’s predecessor as producer — recalled that he “always disliked the internal illustrations” in the books and, presented with the artwork for his own novelisation Doctor Who and the Daemons (1974), insisted that one image be redrawn. He did this, “at a meeting with [editor] Richard Henwood and the artist” (The Target Book, p. 21). Letts says they complied with his request but I wonder if we can read anything into the fact that the artist in question, Alan Willow, was commissioned to provide artwork for a further six Target Doctor Who titles but Letts did not write for the range again for 20 years.

Maybe there wasn’t any great falling out. There could be other reasons why Letts didn’t write another book sooner. He says in his memoir Who and Me that he often struggled with writing deadlines. He would also have had other commitments as a freelance TV director. Whatever the reason, it makes Letts very unusual: for the first decade of the Target range of Doctor Who novelisations, he was the only author to write just one book.

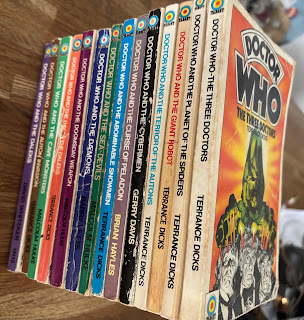

(Caveats a gogo: By “first decade”, I’m counting from Richard Henwood first working on the range, in late 1972. Bill Strutton is also a one-off Target novelist but Doctor Who and the Zarbi (1973) was a reprint of a book originally published in 1965. Following Letts, the next one-off author for the Target range was Andrew Smith, with Full Circle published in September 1982. By that time, Terrance had published 43 of his 64 Doctor Who novelisations, Malcolm Hulke 7, Ian Marter 4 (+5 to come), Gerry Davis 3 (+2), Philip Hinchcliffe 3, Brian Hayles 2 and John Lydecker 1 (+1).)

Letts’s sole novelisation is adapted from his own TV serial, co-written with Robert Sloman, and Target had scheduled two more novelisations of Letts/Sloman stories. Doctor Who and the Green Death and Doctor Who and the Planet of the Spiders are listed as “in preparation” in the first edition of Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen, published 21 November 1974 — just a month after Letts’s Doctor Who and the Daemons.

My suspicion, then, is that Letts was initially signed up to novelise three of his own four TV serials. (Of the fourth, “I would agree that The Time Monster is flawed in a number of ways,” he says in his memoir, p. 153.) But, having delivered the first book, I think something changed and the other two stories were reassigned. Malcolm Hulke novelised The Green Death (published 21 August 1975, the only Hulke novelisation not from a Hulke script), and Terrance took Planet of the Spiders.

Doctor Who and the Planet of the Spiders is a breezy, exciting story, the six half-hour TV episodes conveyed in just 115 pages of text. Even with ads for other books etc, it’s a slim volume — thinner than other Target novelisations that are also 128 pages, not least the next one. My memory is that, as a child, I found this less daunting than other Doctor Who books.

Even so, Terrance takes the opportunity to add to events seen on screen with a short prologue, bringing us up to speed with what emeritus companion Jo Jones (nee Grant) has been up to since last seen on screen / the end of the last-published book. To get the story started with a bang, she is facing death.

This prologue is, I think, steeped in the kind of adventure fiction Terrance had grown up with and still loved. The indigenous people of South America are “Indians” here, “used to be head hunters not too long ago” (p. 9) and Jo speaks of them being “on the warpath” (p. 7). Professor Clifford Jones, on screen a kind-hearted hippie, is now more like Indiana Jones (a character who debuted in 1981 but was drawn from similar archetypes). Jones is an “explorer” (p. 7), “fluent in all the Indian dialects” — because, Jo thinks, having learnt Welsh anything else “must seem simple” (p. 8) — and ready to defend himself with “the heavy revolver packed somewhere at the bottom of his luggage” (p. 7).

It will be interesting to see how this kind of thing compares to the Mounties trilogy, the non Doctor Who books Terrance wrote for Target around the same time. (If you can’t wait, there’s a compelling review of the first Mounties book, The Great March West, by the great Matthew Kilburn.)

We’re quickly back to the story as seen on screen, the Doctor and the Brigadier spending an evening out at a cabaret show. It’s mostly told from the Brigadier’s perspective: he groans at the comedian’s jokes while the Doctor chuckles along. We then switch to the Doctor’s POV, when he’s left “open-mouthed” after the Brigadier “makes one of his rare jokes” (p. 13). As in previous books, Terrance is really good on the enduring friendship of these two very different characters.

Then, wallop, he drops a bomb: for all the Doctor might enjoy his night out, we’re told it’s “the prelude to the most dangerous adventure of his life” (p. 14).

Things largely follow the TV story, though Terrance adds some fun details. Sarah Jane Smith, for example, is “researching a story on grass-roots resistance to property speculation [in London] for that [unspecified] magazine” (p. 14). It’s akin to the stuff about her day-job in Doctor Who and the Giant Robot.

When we glean something of the Brigadier’s love-life, we’re told that Doris gave him his wrist watch when he was still “gay young subaltern” (p. 22), i.e. long before his first screen appearance in The Web of Fear. At the end of the story, the Brigadier offers some comfort to Sarah, who is losing hope of seeing the Doctor again given that he’s been missing for three weeks.

“Oh, that’s nothing. One time I didn’t see him for months — and what's more when he did turn up, he had a new face.”

The implication is that the events of The Invasion take place just months before Spearhead from Space, perhaps even in the same year. In The Invasion, the Brigadier says it “must be four years” since his first meeting with the Doctor in The Web of Fear. The novelisation of Planet of the Spiders muddles these two things:

“‘That’s nothing,’ said the Brigadier stoutly. ‘After the first time I met him, we didn’t meet again for some years. And then he turned up with a completely different face.’” (p. 119)

But otherwise the novelisation is peppered with neat little fixes. Here, the villainous Lupton and his cronies acquire their nefarious powers by stealing “forbidden books” (p. 30) from the monastery — making me wonder if K’anpo Rinpoche has brought volumes to Earth from his home planet. The Doctor feels guilt for the death of Professor Clegg, even though the man is revealed to have had a heart condition (pp. 32-3), whereas the death is rather glossed over on screen. Another neat fix is to describe UNIT as a “semi-secret organisation” (p. 40), what with its poor record on security.

The planet Metebelis 3 is more impressive than on TV. As well as the sheep mentioned but not seen on screen, there are also fields tended by the humans. Perhaps the biggest change, though, is the death of Lupton — his battered corpse held in the air by the murderous spiders, who then close in to feast on his body (p. 113). Even Earth is more impressive: in the aerial chase, Terrance tells us about tactics, and how the Red Baron made use of the position of the Sun to hide himself from his enemies (p. 47); that implies a sunnier day than the drizzle seen on TV.

I’ve noted before Terrance’s delight in dropping a precise, unusual word into his straight-forward novelisations. That doesn’t really happen here, though I suppose “regenerate” (p. 109) is a big, mind-blowing concept, even if taken from the scripts. But this is also the first book in which he refers to the Doctor’s car, Bessie, as a “roadster” (p. 39).

Technically, it’s not the right word: a roadster is a two-seater without a fixed roof whereas Bessie is a four-seater tourer. But I think “roadster” works better to convey a mental image of the a cheerful, characterful motor, the kind of car seen in Genevieve or filched by Mr Toad. Oh, and speaking of Terrance’s delight in specific words, what joy that K’Anpo, dying, refers to himself as “had it”.

“He produced the newly-learned colloquialism with evident pride” (p. 114)

Several additions to what we see or hear on screen explore the philosophy underlying the story. The Doctor and K’Anpo discuss, in “sonorous Tibetan”, obscure and ancient texts. But their conversation about fitting an ocean into a goldfish bowl (p. 58) has a wider bearing; it’s an analogy for the TARDIS and so for Doctor Who as a whole.

On TV, K’Anpo speaks of the coming of, “The moment I have been waiting for,” which is “the moment of truth” for both himself and the Doctor in facing what is to come. In the book, K’Anpo is more pointed about the nature of this threat:

“‘The moment of death,’ said the old man placidly. ‘The moment I have been waiting for.’” (p. 109)

There’s an echo of this in the Fourth Doctor’s final words at the end of Logopolis, where the moment is prepared for. Coincidence — or did Christopher H Bidmead read this novelisation before he wrote the next story to kill off a Doctor?

With Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen, the last novelisation Terrance wrote while in his day-job as script editor on TV Doctor Who, I suggested that Barry Letts advised him on the details of life in a Buddhist monastery. I don’t think that happened in this case, perhaps because they no longer shared an office. For one thing, the novelisation lacks the same kind of specific detail. For another, there’s evidence that Terrance worked from draft scripts, for example when he calls UNIT’s medical officer “Sweetman” not “Sullivan” (p. 35) — a detail Barry Letts would have picked up on, having cast Ian Marter as Harry Sullivan.

Had Letts been consulted, he may have had different ideas about what happens to the newly enlightened Tommy after the events of this story. Terrance has Tommy go to University — with a capital U (p. 120) — I think following in Terrance’s own footsteps as a working-class grammar-school student caught in what he called an “educational updraft” that transformed his life.

There’s a hint in this novelisation of Terrance’s life transforming once again, no longer in partnership with his producer and now a freelance out on on his own. This was Barry’s TV story but it is Terrance’s book.

Next time: Doctor Who — The Three Doctors. Only first read below...

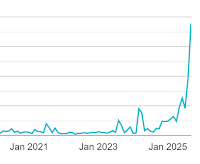

* These long, detailed posts about old Doctor Who novelisations written by Terrance Dicks have proven to be a lot more popular than I expected. In recent weeks, the site stats for this ‘ere old blog have gone off the scale. So, first of all, thank you for reading.

* These long, detailed posts about old Doctor Who novelisations written by Terrance Dicks have proven to be a lot more popular than I expected. In recent weeks, the site stats for this ‘ere old blog have gone off the scale. So, first of all, thank you for reading.But also, posts like this take time and effort when I should be working. If I’m going to do more, I’ll also need to buy some of the rarer of Terrance’s books which are expensive. Basically, I can’t keep doing these posts for free.

A few people have been in touch to suggest I should set this up as a paid newsletter. Looking into the details, that all seems a bit involved and requiring of commitments. Instead, I’ve set up a simple Kofi account.

I’ve busked for your entertainment, now I’m rattling the tin. Throw in a coin or two and I’ll busk some more. If not, I will shuffle off into the shadows.

September 23, 2025

Bret Vyon Lives!

Big Finish have announced the details of Bret Vyons Lives!, the second volume of adventures for the Space Security Service. This time, as well as being producer, I've written one of the three stories.

Big Finish have announced the details of Bret Vyons Lives!, the second volume of adventures for the Space Security Service. This time, as well as being producer, I've written one of the three stories. The set is out in January. Blurb and puff as follows:

Bret Vyon Lives!

Jane Slavin and Joe Sims encounter some familiar faces in the second volume of full-cast Space Security Service audio adventures, due for release January 2026.

The guardians of the Solar System – agents Anya Kingdom (Jane Slavin), Mark Seven (Joe Sims), and Sola Akinyemi (Madeline Appiah) – return for three thrilling original adventures.

Their most dangerous enemies, the Daleks (Nicholas Briggs), are back, in greater numbers than ever, exterminating their way across the cosmos. And when she becomes their prisoner, Anya encounters a man she used to know and love – her uncle Bret Vyon.

This Space Security Service agent was originally played by Nicholas Courtney in 1965-66 Doctor Who TV serial The Daleks’ Master Plan, and here is voiced by Jon Culshaw. Anya knows her uncle is dead, so who is this living, breathing Bret Vyon?

The Worlds of Doctor Who – Space Security Service: Bret Vyon Lives! is now available to pre-order for just £19.99 (as a digital download to own).

The three exciting interplanetary adventures are:

The Man Inside by Simon Guerrier

Anya Kingdom is a prisoner of the Daleks on a very peculiar space station orbiting a very peculiar star. The Daleks don’t want to kill Anya; they want to break her down psychologically.

One way to do that is to lock her in a cell with someone Anya knows is a fake. Whoever, whatever, this man really is, he cannot be her beloved uncle. Bret Vyon is dead, end of story.

But if Anya is to survive, she will need his help…

The Wages of Death by David Llewellyn

Furiosa 237 is a remote world in the hinterlands of the galaxy. Anya and Mark teleport in and quickly take jobs on a cargo shop. They’re undercover – on an urgent, secret mission.

Their task is to locate a device called a Progenitor, then drop it into the nearest black hole — and quickly, before it can hatch.

But at least one person on board is determined to save the Progenitor and unleash its deadly contents: a whole army of Daleks.

The Sky is for Sale by James Kettle

A huge satellite mines the atmosphere of Saturn. Following a number of threats, agent Sola Akinyemi of the Space Security Service is on board, tasked with keeping the workers and their families safe.

Meanwhile, Anya Kingdom is at Triple-S headquarters, working to expose and eradicate corruption in the service. But just as she’s making progress, HQ is attacked. And then the mining satellite is invaded – by a different hostile force!

In the desperate battle that follows, Anya and Sola will have to make impossible choices. Who can they really trust? And what horrors are they willing to sanction if it means defeating the Daleks?

The guest cast of Space Security Service: Bret Vyon Lives! includes Shobu Kapoor (We Are Lady Parts), Forbes Masson (The High Life), and Louiza Patikas (The Archers), plus further names yet to be announced.

Producer and writer Simon Guerrier said: “Anya Kingdom faces her greatest challenge yet as a prisoner of the Daleks. But help is at hand from the least expected person – Bret Vyon, traitor of the SSS and Anya's long-dead uncle! With this second batch of adventures, we really wanted to raise the stakes. With the Daleks on the warpath, Earth's future depends on alliances – but who can Anya really trust?

“What a delight it’s been working on this set of three thrilling adventures steeped in the rich lore that Terry Nation created all those years ago. I’ve loved every stage of collaboration with John Dorney and Barnaby Kay on this compelling, fast-paced series.

“The one I've written is a particular treat. An age ago, I worked on stories featuring SSS agent Sara Kingdom as played by the brilliant Jean Marsh. So it's been a particular pleasure to revisit Sara’s brother Bret and tell something of his side of their fateful story. And then there's what David and James have written to follow... Oh, just you wait!”

Big Finish listeners can save money by pre-ordering Bret Vyon Lives! in a multibuy bundle with the previous volume of Space Security Service (June 2025’s The Voord in London) for just £38 (download to own).

All the above prices (including pre-order and multibuy bundle discounts) are fixed for a limited time only and guaranteed no later than 28 February 2026.

September 21, 2025

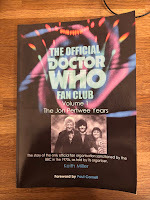

The Official Doctor Who Fan Club vol 1, by Keith Miller

In late 1971, 13 year-old Keith Miller from Edinburgh wrote to the BBC to ask about the status of the official Doctor Who fan club, run for the two previous years by Graham Tattersall. Within months, Miller had taken over as secretary and thrown himself into things with great zeal. He soon produced Official Doctor Who Fan Club (ODWFC) pens and badges, a newsletter — the first ever Doctor Who fanzine — and got the popular comic TV Action + Countdown to print his name and address, so that fans across the country could send off for these goodies.

In late 1971, 13 year-old Keith Miller from Edinburgh wrote to the BBC to ask about the status of the official Doctor Who fan club, run for the two previous years by Graham Tattersall. Within months, Miller had taken over as secretary and thrown himself into things with great zeal. He soon produced Official Doctor Who Fan Club (ODWFC) pens and badges, a newsletter — the first ever Doctor Who fanzine — and got the popular comic TV Action + Countdown to print his name and address, so that fans across the country could send off for these goodies.Oh blimey. Then he had to deliver.

It’s an extraordinary story, which I’ve read before, told through contemporary paperwork: the original newsletters and a wealth of correspondence. Miller didn’t keep copies of the letters he himself wrote; what’s here are the replies, mostly from Sarah Newman, secretary to Doctor Who producer Barry Letts.

Newman was encouraging, warm-hearted and patient, helping where she could by providing addresses of Doctor Who cast and crew he could interview, as well as stencils for Keith to produce the newsletters so that she can then have them duplicated, and reminding him to not let the club get in the way of school work. She’s kind and practical when Keith’s father suddenly dies, having lost her own father when she was around the same age. Newman is also stern when she needs to be, and doesn’t mask her thoughts about some other young, keen fans — famously, including one P. Capaldi. It’s all rather raw and unguarded and sometimes excruciating, but also very moving.

Keith and his newly widowed mum journeyed down to London to visit the studio recording of Carnival of Monsters, Keith telling us in his notes which celeb he stood next to in the urinals of TV Centre. A year later, he was trusted to make the journey on his own to see recording of The Three Doctors; he made the nine-hour journey, visited the studio and then raced for the bus home, all in one very long day.

There are some very interesting details for my own selfish needs. For example, the first original Target novelisations, Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion and Doctor Who and the Cave-Monsters were scheduled to be published on 17 January 1974 but according to Target editor Richard Henwood here, the widespread shortage of newsprint meant they were delayed for several weeks. The next pair of books, Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon and Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks were then due for publication in March but, according to Keith’s newsletter, delayed until July — which explains the big gap between their scheduled release date and the next books published by Target, that September.

This and other such minutiae help to illuminate the timeline I’ve already built up from other sources, and provides leads for further enquiry. I have much more to say (about the changing running order of stories in production and the actors expected to be in them, about a particular party…), but I’ll save it for my book.

The last letter in here, dated 2 September 1974, is from Ann Burnett, secretary to incoming Doctor Who producer Philip Hinchcliffe. As Keith says in his closing words, there was no goodbye from those he’d been in constant touch for years. How abrupt. How haunting. My sense from the notes is that it still feels raw.

September 19, 2025

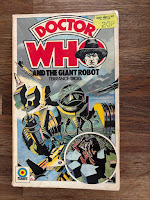

Doctor Who and the Giant Robot by Terrance Dicks

First published on 13 March 1975, this book must have come as a surprise to the now well-established readership of these Doctor Who novelisations. For one thing, it had not been listed among titles “in preparation” in previous books — not even in Doctor Who and the Cybermen, published just 22 days before.

First published on 13 March 1975, this book must have come as a surprise to the now well-established readership of these Doctor Who novelisations. For one thing, it had not been listed among titles “in preparation” in previous books — not even in Doctor Who and the Cybermen, published just 22 days before. From this and other evidence we can deduce that Doctor Who and the Giant Robot was commissioned relatively late, fast-tracked through production (with no internal illustrations, saving time) and then slipped into the existing schedule as swiftly as possible, the first of a relaunched range.

That’s another thing that would have surprised readers: this book looked and felt very different.

First editions of the initial 12 Doctor Who novelisations, published between 2 May 1973 and 19 February 1975, are easily distinguished. The covers are all in a similar style and by one artist, Chris Achilleos. He later recalled that he was asked to emulate the work,

“that Frank Bellamy had done for the [listings magazine] Radio Times; in fact it turned out that they had already asked Frank if he would do them but he had turned them down, so they asked if I would do them in that style” (The Target Book, by David J Howe with Tim Neal, p. 22).

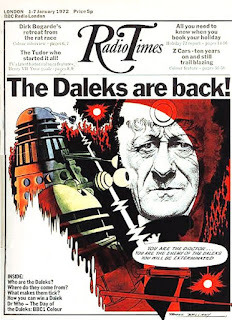

Bellamy produced a great deal of Doctor Who artwork for Radio Times — enough to fill a book. The Target team seem to have a favoured a particular piece: the striking cover art Bellamy produced to promote the 1972 series of Doctor Who and the return of the Daleks.

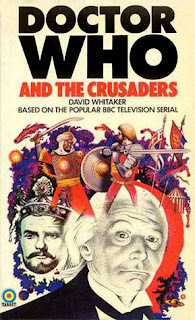

Frank Bellamy’s cover for

Frank Bellamy’s cover for Radio Times, 1-7 January 1972

Compare that to the first of the cover art Achilleos completed for Target:

Chris Achilleos’s cover for

Doctor Who and the Crusaders, 1973

In both, there’s a prominent, stippled black-and-white portrait of the Doctor, surrounded by smaller illustrations of the antagonists in the given story, largely in bright colours, along with stars and cosmic phenomena. This dynamic montage is on a white background and takes up the lower part of the frame, so as not to obscure the title logo in black and other wording — which are all the more striking against white.

That is also true of the next 11 books. On these early novelisations, the Doctor Who logo dominates in big, thick, black letters, establishing the range. The rest of the title is in smaller lettering but still bold capitals, in a striking colour that compliments the artwork.

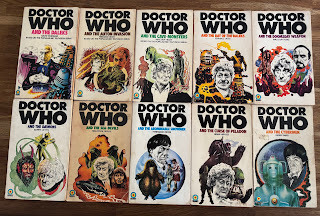

The spine of each book is in the same colour as its title. That makes the books, together, distinctive even lined up on a shelf — iconic, in the true sense of the word.

Ten of the first 12 Target books, and four

Ten of the first 12 Target books, and four of the relaunched titles with white spines

Picking up a first edition of one of these initial 12, they also have some heft. They all — with one exception — comprise 160 pages, or five sections of 32 pages, on relatively thick paper. (Doctor Who and the Sea-Devils is 144 pages but still feels substantial.)

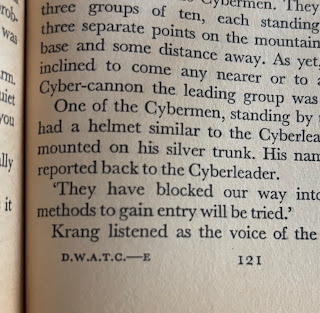

The start of each new section is easy to spot: they are marked at the foot of the page with the initials of the title and then a letter indicating the sequence in which they should be bound. For example, Doctor Who and the Cybermen by Gerry Davis has “D.W.A.T.C.—B” at the foot of page 33, “D.W.A.T.C.—C” at the foot of page 65, “D.W.A.T.C.—D” on p. 97 and ‘D.W.A.T.C.—E” on p. 121.

(John Easson at the British Printing Society tells me that that the spines of sections were also often marked, usually in descending “steps”, to make the correct sequence obvious in binding — but I’m not unpicking the covers of my precious books to check! I’ve consulted John about the mechanics of producing subsequent editions of these books, more on which anon. Maybe. If you are good.)

Doctor Who and the Giant Robot begins a lengthy run of shorter novels, reduced by 20% to 128 pages and four sections — with some longer books on occasion. That this was as part of an overall relaunch of the range is evident from the cover, which boasts a bold new look.

First, there’s the distinctive new logo to better match the one used on TV and now in vibrant cover. The artwork by Peter Brookes is in a very different style to that by Chris Achilleos. While it still has a comic-strip flavour (Brookes says in The Target Book that he, too, was asked to emulate Frank Bellamy), this is full frame instead of a montage of selected items on white. The logo and wording are placed on top of the artwork — partially obscuring one of the planes as it blasts away at the Robot.

The comic-strip feel is further conveyed by there being two different-sized panels on the cover, and two more on the back. On the cover, prominence is given to the titular monster, emphasising its giant size by showing it attacked by small planes and clutching a human. On the back, we see its huge foot kicking a truck, scattering tiny soldiers. This is perhaps overselling the contents of the book, in which the Robot is giant-sized for a mere four pages (pp. 116-120).

That emphasis on the Robot is striking. The new incarnation of the Doctor and new companion Sarah Jane Smith, both making their debuts in the range of novelisations, appear only as small insets. Neither is a particularly good likeness. Compare that to the cover of Doctor Who and the Sea-Devils, published some six months before this, where immediately recognisable portraits of the Doctor and Jo Grant are bigger and more prominent than the monsters.

That emphasis on the Robot is striking. The new incarnation of the Doctor and new companion Sarah Jane Smith, both making their debuts in the range of novelisations, appear only as small insets. Neither is a particularly good likeness. Compare that to the cover of Doctor Who and the Sea-Devils, published some six months before this, where immediately recognisable portraits of the Doctor and Jo Grant are bigger and more prominent than the monsters.In fact, the relaunch doesn’t even feature the Doctor in the main cover artwork. Instead, his head is part of the new logo, in the “o” of “Who”. The plan was for the next books in the series to follow the same format, as we can see from Brookes’s original sketches for Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons and Doctor Who and the Green Death, as published in The Target Book (pp. 32-33). These both use the same illustration of the Third Doctor’s head.

My guess is that this was to streamline the process of producing cover art, whether because each stipple-portrait took time or because every new likeness required approval from the BBC. I wonder, too, if this new format meant Brookes could produce covers more quickly and therefore at lower cost than whatever Achilleos was paid.

Brookes and Achilleos say in The Target Book that the changeover was to give the latter a break from the relentless schedule. But I think other factors were also in play. Businesses often look for ways to reduce internal costs and maximise profits. The Target Book also explains that while the Doctor Who books sold very well, Target’s parent company in the US was in trouble and draining money from the London office.

Then there was the global shortage of newsprint — the paper on which newspapers and books are printed — which had delayed publication of Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion and Doctor Who and the Cave-Monsters, according to Target editor Richard Henwood in a letter to fan Keith Miller on 1 February 1974 (see Miller’s The Official Doctor Who Fan Club vol 1, p. 194). The shortage continued over subsequent months; in July 1974, Michael Meacher MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary for Industry, provided a Written Answer on newsprint manufacture in the UK, providing statistics that production had fallen from 789,400 tonnes in 1969 to 441,900 four years later.

These factors, between them, may explain why the relaunched range of Target books had a significantly reduced word count while selling for the same price. In fact, my second-edition reprint of Doctor Who and the Giant Robot, published in Autumn 1975, retailed at 40p, double the RRP of each of the first three Target novelisations when published just two years previously. Less book, twice the price, and selling so fast they went to reprint in months — the bosses must have been delighted.

I wondered if the reduced word count was part of the brief that incoming Target editor Mike Glover gave Terrance Dicks when they met for lunch on 30 April 1974, two days before Terrance began work writing Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons. Did he initially write that as a 160-page book, then get commissioned to write Doctor Who and the Giant Robot quickly at 128 pages and, once he’d completed that, go back to Terror of the Autons and cut it down to matching size?

The archive of Terrance’s papers includes several original typescripts for his Doctor Who novelisations, though sadly not for Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons. But the archive also includes the 1974 diary in which he recorded progress on writing the book, which says that chapter 1, written between 2 and 3 May 1974, comprised 10 pages. The published version runs from pages 7 to 16, so it’s roughly the same.

That record of progress on writing ends with him reaching Chapter 10 at a total of 84 pages; it’s 96 pages in the book (up to page 103, with the story starting on page 7), but the book includes several internal illustrations by Alan Willow which take up space. The implication is that the full typescript, comprising 12 chapters, was about 100 pages. With Willow’s illustrations, front matter (title page, indicia, lists of other books in the range), that gives 128 pages of book. It’s certainly nowhere near enough to fill 160 pages. So Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons was always meant to be this length.

But I also don’t think this was a new direction for Terrance. Here is where things go a bit hardcore. There are even graphs.

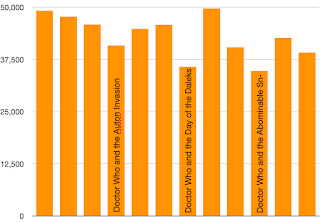

The excellent, exhaustive Based on the Popular BBC Television Serial by Paul MC Smith provides word counts for the main text of each Target novelisation. Here is the data for the first 12 in order, with the titles of those written by Terrance:

The first six of these books are roughly between 45,000 and 50,000 words, except for Terrance’s one contribution which is more like 40,000. The second six books are roughly between 40,000 and 45,000 words, excerpt for Terrance’s two which are more like 35,000.

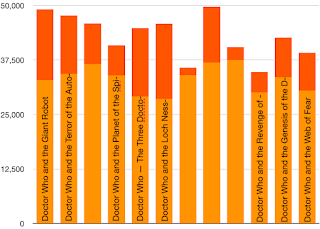

The relaunch saw a drastic reduction in word count by all authors compared to the first 12 books (in darker orange below) — but Terrance, now writing a greater proportion of the Doctor Who novelisations, still delivered fewer words in each one than his peers.

This isn’t always obvious from the physical books themselves. The wordiest of the first 12 novelisations, Doctor Who and the Daemons (49,699 words) contains the same number of pages as the least wordy title, Terrance’s Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen (34,723). That uniformity required some skill from the typesetter. Differences in leading and font size mean a full page of text in Doctor Who and the Dæmons contains 38 lines but in Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen there are 34.

Some books were also padded out with adverts for other titles; the first advert at the back of Doctor Who and the Giant Robot is for, er, Doctor Who and the Giant Robot. (Paul MC Smith tells me he discounted this extra material from his word counts.)

But I don’t think Terrance was skimping on work by producing shorter books. His editors could always have asked him for additional material if they felt a book needed padding out. In fact, the work he delivered seems to have been cut. The surviving typescript of Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion includes a whole section in the prologue not included in the published book: following the Second Doctor’s trial, Time Lord Scanners cooly observe Earth and then, on the planet’s surface, UNIT’s Lance Corporal Walmsley detects the incoming meteor shower. (There’s no female UNIT Officer in charge, as played on screen by Tessa Shaw.)

As a result, I think the shorter books are evidence of Terrance’s dictum, as cited by his friend Barry Letts:

“Anything can be cut, and cutting will always improve it.” (Letts, Who and Me, p. 154)

He wrote short, pithy novels because they were better. Incoming editor Mike Glover could see the sense of this, editorially and to save paper / reduce internal costs, and asked other authors to follow Terrance’s lead.

So what about the book itself?

Doctor Who and the Giant Robot was published just 54 days after the conclusion of the TV serial on which it was based. It’s a relatively faithful prose version of what we see on screen but with some notable differences. The TV serial begins where the previous story ends, continuing the scene in which the Doctor regenerates. (This was all the more seamless on TV because Planet of the Spiders was repeated, in omnibus form, the day before Part One of Robot went out.)

In the book, Terrance switches the first two scenes so that we now begin with the Robot — as with the cover, focused on the monster. When we return to the Doctor’s laboratory at UNIT, it’s been a several days since he regenerated.

We can deduce that Terrance wrote the novelisation from his own scripts, not the versions amended in rehearsal by the cast and director. Hence the Doctor doesn’t skip with Harry Sullivan, he doesn’t say “There’s no such word as can’t” or the Brigadier’s middle name, and he uses a pencil and paper rather than typing at super-speed. At the end, the Doctor vanquishes the Giant Robot from a UNIT Land Rover driven by Harry Sullivan not Benton. The Doctor's car Bessie does not feature in the book at all.

Terrance seems to have muddled up what he must have been told about the new Doctor’s costume, which he describes as,

“wide corduroy trousers, a sort of tweed hacking-jacket with a vaguely Edwardian look, and a loose flannel shirt” (p. 24)

It’s the other way round: in Robot, the new Doctor wears tweed trousers and a corduroy hacking jacket.

The book adds several lovely details. The Robot kills an unnamed sentry, then lays out the man’s body “almost tenderly” (p. 8). Terrance repeats the word “tenderly” when the Robot kills two further victims, on p. 22 and p. 55, making this a telling bit of character detail. Three times we’re told that the robot is a bit like a giant cat (p. 37, p. 67 and p. 117), again I think helping to build the reader’s sympathy for the machine.

Another repeated word is the unfortunate sentry’s “ruddy” (used by other characters on p. 17, p. 18, p. 89 (twice) and p. 106). I wonder if Terrance was told that word was okay for child readers, and so used it wherever he could.

There’s more threat in the book than on TV. While the Doctor is recuperating at the start, the Brigadier refers to his friend’s comatose state as a “living death” (p.11), a disturbing idea that works here because more time has passed since the regeneration. When the Doctor recovers, he rifles through the pockets of his former self’s clothes — mirroring a scene in Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion (and in the script of Spearhead from Space but which never made it to the screen). When the Doctor battles the Robot, it throws him across the room (p. 83). It’s also nice that we get to share Harry’s first sight of the interior of the TARDIS; on TV that would have required an additional set.

Some additions are less about threat or scale but about better establishing character, such as why journalist Sarah Jane Smith wants access to Thinktank (one word):

“You see [a very Terrance phrase!], I’m very keen to get away from all this woman’s angle stuff, and if I could come up with a really good scientific story…” (p. 13)

Later, she’s worried about heading off in the TARDIS because she has “deadlines to meet” (p. 122), again helping to make her real (and riffing off Terrance’s own new freelance status). It’s from Sarah’s perspective that we first see Harry, who she likens to Biggles, Bulldog Drummond and the heroes of the Boy’s Own Paper (p. 15). We later learn that her journalistic instincts are dead right:

“Suddenly Harry spoke up. ‘What you need, sir, is an inside man.’ He produced the phrase with obvious pride. ‘Someone planted to keep tabs on them.’ Harry spent a good deal of his off-duty time reading lurid thrillers” (p. 49)

Of course, the italicised phrases are examples of Terrance’s love of specific vocabulary, despite his reputation for simple, straightforward prose. On p. 80, the Doctor is described as a “mountebank”, while on p. 119 he refers to the metal-eating virus as a “bucket of jollop”. (On the same page, he refers to Harry as “my boy”, perhaps a ghost of an early draft, before Tom Baker had been cast.)

I think the book reveals some of the influences on the original story. On p. 114, the Doctor muses that the Robot is suffering from an Oedipal complex, which is surely a reference to the robopsycology of Isaac Asimov’s famous sci-fi stories. (And also makes me wonder what plans the Robot had in mind for Sarah once the rest of humanity had been destroyed...)

The Giant Robot being attacked by planes, as seen on the cover, is obviously drawn from King Kong. But it’s notable that Terrance says the Robot grows to “fifty feet” tall — the specific figure surely suggesting he had in mind Attack of the 50 Ft Woman (1958).

But the reference that stopped me in my tracks was the one about the,

“peculiar business at the meditation centre.* ...

* Told in DOCTOR WHO AND THE PLANET OF THE SPIDERS” (p. 9)

This was the previous TV adventure — but the book that Terrance would write next, published seven months after this one. It is whetting the appetite of readers. But also, up to this point, his books had made reference to other, already published Target titles. This, just at the moment he greatly increased his output, is the first sign of him thinking in series, of books still to come.

It is a footnote from the future.

See my list of 236 books by Terrance Dicks My biography, Written by Terrance Dicks, will be published by Ten Acre Books next yearSeptember 14, 2025

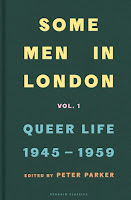

Some Men in London vol 1, Queer Life 1945-1959, ed. Peter Parker

Reading Bookish and its brief, telling reference to a man who walks into the sea because someone has his letters prompted me to try this, the first of two volumes collecting primary sources on what the blurb calls "the rich reality of life for queer men in London, from the end of the Second World War to decriminalization in 1967."

Reading Bookish and its brief, telling reference to a man who walks into the sea because someone has his letters prompted me to try this, the first of two volumes collecting primary sources on what the blurb calls "the rich reality of life for queer men in London, from the end of the Second World War to decriminalization in 1967."It's a fascinating, insightful and often disturbing read, presenting contemporary accounts by gay men alongside the things said about them such as in the press and Parliament. Editor Peter Parker largely lets these things speak for themselves, providing context rather than judgement, though one or two contributors get short thrift and you feel his anger in the Introduction when citing archives that would not allow publication of relevant material.

Some of what is presented here I knew, such as Noel Coward's outward support for and inward impatience with Sir John Gielgud following his arrest. I also knew some of the history of the Fitzroy Tavern. But it's very different to see all this stuff in context. There is a lot of buttoned-up, barely contained emotion, as much from those apoplectic about gayness as the gay men themselves.

A number of pieces here are particularly haunting. There's an extraordinary account by Brian Epstein, describing his arrest on 24 April 1957.

Having been to see a play that evening in London, Epstein stopped to use the public lavatory at Swiss Cottage tube station and, on leaving, made eye contact with a man staring at him, who then followed Epstein down the street. When Epstein looked back, the man, "nodded again and raised his eyebrows". Epstein walked on but then decided to go back to this man, who asked if Epstein knew anywhere they could go. Epstein suggested a nearby field, but as they headed off together another man joined them - both men were policemen and arrested Epstein for "persistently importuning".

At the police station, the arresting officers told the sergeant that they'd caught Epstein importuning four men. The next day, at Marylebone Magistrates' Court, he was advised to plead guilty as it would, said the detective, result in a simple fine rather than his history being looked into. The same detective then proceeded to give evidence that Epstein had been caught importuning seven men.

"I am not sorry for myself. My worst times and punishments are over. Now, through the wreckage of my life by society, my being will stain and bring the deepest distress to all my devoted family and few friends. The damage, the lying criminal methods of all the police in importuning me and consequently capturing me leaves me cold, stunned and finished" (pp. 277-78)

It's one of a number of examples here of similar methods and false claims by police. I've looked up the details and Epstein was sentenced to two years' probation. Given his experience, it's extraordinary to learn that in 1958, while still on probation, he went back to the police to report being assaulted and extorted by a man he'd had sex with, which ended up in him having to testify in court and to come out to his family. The press were not allowed to name him; if they had, I suspect Epstein would never have gone on to be manager of the Beatles.

Among the examples of disgust and fury from the press, Parker quotes in their entirety three notorious pieces by Douglas Warth, published over consecutive weeks in the Sunday Pictorial in the summer of 1952. The first, from 25 May, is headlined "Evil Men" and feels the need to explain slang terms "slap", "dragging up", "send up", "camp" and "rough" (p. 134). That suggests readers had little knowledge of the subject, but the piece goes on to counter misconceptions and address claims made in defence of gay men.

It quotes London psychiatrist Dr Carl Lambert, who admits that gay men can include those in what he calls the "virile professions" such as,

"generals, admirals [and] fighter pilots ... The brilliant war records of many homosexuals is explained by the fact that, as the Spartans, they fought in the company of those whose opinions they valued most highly" (p. 133).

The implication is that heterosexuals who display courage under fire do so for reasons other than peer pressure and being easily led.

The following week, 1 June, Warth was trying to unpick the causes of gayness and cited an unnamed "celebrated psychiatrist":

"We all have some homosexual tendencies. Sex is a delicate balance and there is something womanly about the toughest man. So we must all alert ourselves to the danger" (p. 139)

There was more of this attempt to explain causes the following week. The extraordinary subheading "Why not a Broadmoor for such people" refers to the infamous high-security psychiatric hospital, but the piece that follows then suggests a physical cause:

"There is a great deal to be learned about the delicately balanced endocrine glands which determine whether or not a man could take to these unpleasant activities" (p. 141).

Having suggested a hormonal cause, effectively something a person is born with, the article then switches back to psychiatry, quoting Harley Street psychiatrist Dr Clifford Allen:

"Homosexuality is caused by identification with (or moulding oneself on) the mother ... In such cases, the mother, by being alternately cold and affectionate, has made the child seek an affection it has never enjoyed."

Allen goes on to say it's not all the fault of mothers.

"With a son often the father is too busy, or too interested in golf" (p. 143).

Parker, usually impartial about sources, describes Allen as "unhelpful" (p. 381). But the muddle here is all Warth. The cause of gayness is glands, it's Mum, it's Dad, it's golf. It's something in some of us and it's something in us all. It's secret, nefarious and evil; even when gay mean are "brilliant" and heroic, it must be for wrong reasons.

There are other dubious explanations given by those horrified by gayness. For example, Sir John Nott-Bowes, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, gave evidence to the Wolfenden Committee on 22 November 1954 that the recent rise in arrests for importuning was due to, of all things, the Festival of Britain:

"This is borne out by the fact that the increase took place during the exact months when the South Bank Exhibition was open" (p. 204).

Forget glands or golf; it's the Skylon.

Speaking of Wolfenden, Some Men in London, ends with biographies of the leading figures cited, presented in alphabetical order. That means we finish with Sir John Wolfenden and his son. We're told that on being appointed as chair of the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution, Sir John wrote to Jeremy:

"I have only two requests to make of you at the moment: 1) That we stay out of each other's way for the time being. 2) That you wear rather less make-up" (p. 431)

That we're also told that this is something Jeremy Wolfenden "claimed" suggests editor Peter Parker is not convinced it is true. How fascinating, even so. Jeremy was born in 1934 and,

"did a Russian interpreter's course during his National Service" (p. 430).

That means he was probably at the Joint Services School for Linguistics at RNAS Crail in Scotland, one of the 5,000-7,000 students there between 1956 and 1960. Given his age, Wolfenden could well have been there alongside Alan Bennett (also born 1934), Terrance Dicks and Dennis Potter (both born 1935), Jack Rosenthal (1931) and Michael Frayn (1933) - all but Terrance mentioned here.

Terrance's widow Elsa tells me that Terrance didn't exactly apply himself to the Russian course and spent most of his time in Scotland playing golf. Jeremy Woldenden seems to have stuck at his lessons, given that he was recruited by the Secret Service and later become Moscow correspondent for the Daily Telegraph. While in Moscow, he,

"befriended Guy Burgess, whose habits of drunkenness and promiscuity he shared. Caught in flagrante, he was asked by the KGB to report on his press colleagues, while the British wanted him to to report back to them" (pp. 430-31).

He died in mysterious circumstances in 1965. In looking into this, I find that the Wolfendens, father and son, were the subject of a film shown on BBC Four, Consenting Adults (2007). The role of Police Constable Butcher was played by Mark Gatiss - years before he conceived Bookish.

September 13, 2025

David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens

It's been fun to revisit this novel as part of my research into the BBC-1 Classic Serials of the 1980s worked on by Terrance Dicks. He was the producer of a TV dramatisation this broadcast in late 1986 which was nominated for a BAFTA.

It's been fun to revisit this novel as part of my research into the BBC-1 Classic Serials of the 1980s worked on by Terrance Dicks. He was the producer of a TV dramatisation this broadcast in late 1986 which was nominated for a BAFTA. (Tedious nerd bit because this is how my brain works: the director was Barry Letts, Terrance's former boss on both Doctor Who and the Classic Serial, and the cast included Stephen Thorne (who I interviewed), Terence Lodge and Christopher Burgess from their time on Doctor Who. Then there was Sarah Crowden, whose father met with Letts in 1974 to discuss taking the role of the Fourth Doctor.

I'm conscious, too, of Terrance and Barry Letts working on this stuff from their office in 509 Union House at the BBC, upstairs from the crises affecting Doctor Who (producer John Nathan Turner in room 304, his script editor in 312), with David Copperfield broadcast over the same weekends as The Trial of a Time Lord. Did they trade ideas for casting? Here we have Owen Teale, fresh from Doctor Who and the Vengeance on Varos. And there's a nod to future Doctor Who, too, with Simon Callow fresh from A Room With A View, the film that made his name, here as one of Dickens's best known characters, Wilkins Micawber, 20 years before taking the role of Dickens in Doctor Who...)

Anyhow. The novel is the autobiography of a fictional character who has a number of resemblances to the real-life Dickens. We follow David Copperfield - also known as "Master Davy", "Daisy" and "Trot" in different phases of his life - from birth through school and different jobs and two marriages, to established and successful writer. I'd have liked more on what he saw and felt in his time as a parliamentary reporter, not just how long it took to learn shorthand, because I've done the same job. But an impression can be gleaned from what David says when he moves on:

"One joyful night, therefore, I noted down the music of the parliamentary bagpipes for the last time, and I have never heard it since; though I still recognize the old drone in the newspapers, without any substantial variation (except, perhaps, that there is more of it), all the livelong session." (Chapter 48, Domestic)As well as David, we follow the lives of a huge cast of characters around him, not least his school friend Thomas Traddles and early crush Emily, his nursemaid Clara Pegotty, aunt Betsey Trotwood and the feckless but well-meaning Micawber, always determined that something will turn up. In this version, engagingly narrated by Richard Armitage, Micawber is a broad Brummie, which produced some odd mental images as I listened to this in the wake of the death of Ozzy Osborne.

(More of how my brain works: early on, Clara takes young Master Davy to visit her brother, Daniel Peggoty, who lives in a converted old boat on the beach at Yarmouth. There's a long description of this cosy if eccentric home:

"Over the little mantelshelf, was a picture of the ‘Sarah Jane’ lugger, built at Sunderland, with a real little wooden stern stuck on to it; a work of art, combining composition with carpentry, which I considered to be one of the most enviable possessions that the world could afford." (Chapter 3, I Have a Change)I said before that I think Terrance Dicks might have got the word "capacious" from Charles Dickens; could he also have swiped "Sarah Jane"? (Sarah Jane Smith was, of course, played on screen by Elisabeth Sladen. When she died in 2011, the new companion being devised for Doctor Who was renamed in her honour; Clara was Sladen's middle name.))

Anyhow again. The novel boasts some memorable villains. First, there's David's cruel, violent and manipulative stepfather Edward Murdstone and his sister Jane. Then there's schoolmate James Steerforth, who - brilliantly - Davy is taken in by but we and other characters see through. (In the TV version Terrance oversaw, Steerforth's mother is played by Nyrie Dawn Porter, surely as a kind of a clue to the viewer of moral corruption in the family, given Porter's association with The Forsyte Saga (1967)).

Then there's the ever 'umble Uriah Heep, in whom David spots wickedness long before Micawber lays out, at length, exactly what Heep has done. I don't think David gets better at recognising wrong 'uns - he is still drawn to Steerforth even after knowing the truth about him. I think in part Steerforth's posh, wealthy charm makes him more agreeable to David, so there's some snobbery in his distrust of Heep. But I also think, as others have observed, that Heep is in some ways a dark reflection of David himself: a young man of humble background trying to establishing himself and with an eye on his boss's daughter that might not be wholly appropriate...

If there's a failing here, it's how good and noble David is throughout; loving, patient, tolerant, hard-working, forgiving, blah blah blah. He speaks of his hatred for Heep, but I think that is intended as another signifier of virtue. It makes David rather insipid as a character but also, given how close much of this is to the real life of the author, it kept feeling like self-justification.

The TV version swaps some stuff around, I think to tackle some of this beige. In the book, David and his former schoolmate Traddles are reunited with Micawber and, in chapter 28, they all have dinner at David's, the meal "mutton off the gridiron" plus "a bowl of punch, to be compounded by Mr Micawber". On screen, the bowl of punch is brought forward; it is David's first meal with Micawber, and they drink it instead of a solid meal. In both, the point is to show David and his friends making the best of things, and enjoying themselves, with only limited means. But I think the TV version has added tension because it's not right to be serving such a "meal" to children. That focus on "tension points" is, I think, very Terrance Dicks...

See also:Me on Our Mutual Friend, by Charles DickensMe on Dickens, by Claire Tomalin

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers