Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 4

June 22, 2025

Prisoners of War, by Terrance Dicks

This is an unusual book by Terrance Dicks. Alongside his wealth of Doctor Who novelisations and novels — more of which in due course — he tended to write books in series: there are multiple volumes about T.R. Bear (a bear), Sally Ann (a rag doll) or Goliath (a dog); for slightly older readers, the Baker Street Irregulars and The Unexplained ran to more than 10 books each. Even his non-fiction books tended to be in runs.

This is an unusual book by Terrance Dicks. Alongside his wealth of Doctor Who novelisations and novels — more of which in due course — he tended to write books in series: there are multiple volumes about T.R. Bear (a bear), Sally Ann (a rag doll) or Goliath (a dog); for slightly older readers, the Baker Street Irregulars and The Unexplained ran to more than 10 books each. Even his non-fiction books tended to be in runs.Prisoners of War, first published by Methuen in 1990, is not only a standalone novel, I think it’s also more autobiographical than any of Terrance’s other books. It’s set in the spring of 1944, with young Tony Dent — ie Terry Dicks — starting a new school at “Grendon Moor” in the north of England, where his dad, a sergeant, has been posted to the local prisoner-of-war camp.

Tony’s mum and dad, Bill and Nell, have the names of Terrance's parents, and also their temperaments and backgrounds. The following, for example, matches a description Terrance gave elsewhere about the real-life William Henry Dicks:

“Dad … was what you might call unpolitical. Back in London, he belonged to the Liberal Club, the Labour Club and the Conservative Club, all at the same time. He said the company was better at the Labour Club, the beer was better at the Liberal Club, and the Conservative Club had the best billiard table. Dad could get on with anyone, anywhere, any time.” (p. 56)

Bill is a bit of a wheeler-dealer, able — in the midst of rationing — to acquire champagne for a party, or bacon and eggs for his wife. When posh Lady Carrington screams at him because his army truck has upset the gravel on her drive, Bill easily charms her, and lies to her too, so as not to land her husband in trouble for not passing on “her orders” about where they should park (p. 24). He’s a loveable rogue, good in a crisis and, when needed, in a fight.

While there’s lots on the “happily incompatible” relationship of Bill and Nell, and Tony’s issues fitting in at a new school, the main story involves his burgeoning friendship with a German prisoner, about which both feel conflicted, and the machinations of a Nazi officer in the same camp. There’s also a romantic subplot for Tony — we’re told in the closing chapter that he goes on to marry Lucy Carrington.

Tony shares traits with young Terrance:

“What with being an only child, and our being shunted about so much, I was a keen picturegoer and what my family called a big reader.” (p. 48)

But Terrance turned 9 in April 1944 and though we’re not told Tony’s age, he’s surely older than this given what happens here and that he is taller than his dad (p. 100). There's some other fudging of real-life, in that the imposing headmaster Dr White is surely based on the real-life Dr Whiteley, headmaster of East Ham Grammar School for Boys, where Terrance was a pupil after the war. This is a fictional adventure story grounded in various odd bits of real life — and that’s what makes it so effective. The suspense and moral complexity feel real.

In fact, it’s not quite a standalone novel as it surely follows Terrance’s short story “London’s Burning”, first published in the anthology Streets Ahead — Tales of City Life, also published by Methuen and a year before this novel came out. (Around this time, Methuen published new editions of Terrance’s Baker Street Irregulars books, too).

Streets Ahead was edited by Valerie Bierman, who Terrance had known since 1980 when she invited him to be a guest at the Edinburgh Book Fair and later Edinburgh Book Festival. She says in the introduction that she approached 10 well-known novelists and asked them to write “a story on any theme that interested them — provided it had a city as a background” (p. 7); the results were almost all based on personal experience and connections to the cities they describe. So, the brief inspired something more personal than usual from Terrance. In fact, I think we get some of his best and most vivid writing:

“Most mornings we’d make ourselves late for school by hunting for shrapnel, chunks of ragged metal fragments, all that was left of the exploded bombs. Stamp collecting was nowhere that year.

I thought it was all wonderful. But my mum and dad didn’t and now I can see why.

One morning I woke up to find a gaping, smoking hole where the end house in the street used to be. A nice family called the Strettons, cheerful dad, pleasant mum and two little girls. They’d just moved into the house and done it up and they were pleased as anything with it. Now there was no more house and no more Strettons.” (“London’s Burning”, Streets Ahead, pp. 77-78)

Given the danger, the unnamed narrator is taken by his mother — Nelly (p. 78) — to stay with her cousin on a farm some 50 miles outside London. Homesick, he runs away and arrives back in London as the bombs are falling. It’s a thrilling, concisely told story, running just 11 and a half pages. At the end we're told that the narrator’s dad “finished up Quartermaster-Sergeant in an army camp in the North, and after a time Mum and I moved up to join him” (p. 85).

That matches Tony Dent’s experience in the novel:

“Mum had tried a sort of private-enterprise evacuation on me when the bombing first started, packing me off to relations in the country. I’d hated it so much I’d run away after a couple of weeks.” (Prisoners of War, p. 22.)

They’re surely the same character, but how much of this was based on Terrance's own real experience?

Sadly, Prisoners of War doesn’t seem to have made much of an impact. I’ve found little in the way of press coverage about it, and Terrance didn’t write another book for Methuen after this, though he did contribute a short story to another Bierman anthology, No More School? (1992).

But I think this novel may have influenced something else. It was published in June 1990, and that same month Terrance received a letter from Peter Darvill-Evans, editor at Virgin Publishing, to confirm a new range of original Doctor Who novels. Terrance was invited to come up with a story involving a villain created for the range, the Timewyrm, but was otherwise free as to plot and setting. His synopsis, delivered in August, began with a compelling image:

“The Doctor in erratic pursuit of the Timewyrm finds himself attending the 1950 [sic] Festival of Britain. He realises when and where he is when they emerge from the TARDIS to the South Bank and see the Skylon, the tapering tower that is the symbol of the Festival. It’s there all right — but there’s a swastika on top!” (“Doctor Who: The New Adventures — Exodus of Evil by Terrance Dicks”, storyline received by Virgin Publishing, 23 August 1990).

Just as with Prisoners of War, this was an adventure story based on his own experience, grounding things in the real:

“I actually remembered going to the Festival of Britain with a school party in 1951, so it was fun to bring that in. I remember it rained all the time.” (Andrew Martin, “Terrance Dicks — Writing the Past, Present and Future”, TV Zone Special #5, p. 23.

That’s exactly what we see in what he wrote:

“Beside a broad and sluggish river, a group of concrete pavilions huddled under a fine drizzling rain. A tall slender tower soared gracefully into the mists towards a grey and cloudy sky.” (Terrance Dicks, Timewyrm: Exodus, 1991).

As in the synopsis, this London has fallen to the Nazis and the Doctor and Ace are soon arrested. The Doctor not only escapes but convinces the Nazis that he's a senior officer, commandeering a car and swanning about like he owns the place. It’s deftly both great fun and also tense and suspenseful.

When I first read Timewrym: Exodus in the summer of 1991, I knew this was also riffing on what the Second Doctor does in pretending to be a German office in TV story The War Games (1969) — co-written by Terrance and his friend Malcolm Hulke.

But now, reading Prisoners of War, I can see he was drawing on an older source. In this wheeler-dealer Doctor, there's something of Terrance’s dad.

I’ll be giving a short talk on Terrance Dicks at the Target Book Club event on 19 JulySee alsoDoctor Who and the Wheel in Space by Terrance DicksDoctor Who and the Time Warrior by Terrance DicksJune 20, 2025

Ocean: Earth's Last Wilderness, by David Attenborough and Colin Butfield

This was a bigger hit with my teenage son than Other Minds by Peter Godfrey-Smith, which I think he found a bit too abstract too often. But I found bits of this harder to grapple with because so much of it is about wondrous things we cannot see - a series of visually arresting examples to explain the state of the ocean and what we're doing it, good and bad. We've not yet watched the accompanying film and I suspect, as with other books-of-TV-shows, that this one works best as an aide-memoire to what the reader has already seen.

This was a bigger hit with my teenage son than Other Minds by Peter Godfrey-Smith, which I think he found a bit too abstract too often. But I found bits of this harder to grapple with because so much of it is about wondrous things we cannot see - a series of visually arresting examples to explain the state of the ocean and what we're doing it, good and bad. We've not yet watched the accompanying film and I suspect, as with other books-of-TV-shows, that this one works best as an aide-memoire to what the reader has already seen.It's largely directed at the huge harm done by industrialised fishing, especially bottom trawling, which is so destructive and wasteful - the damage visible from space. I suspect some of the visuals will be harrowing.

Attenborough makes good use of his years of experience, stepping forward as a witness of human-inflicted harm to the planet: he has seen the changes and effects he describes, and can compare the images he captured decades ago so shed light on where things are now. That then continues in the case studies, talking to people with long experience of particular places, who can tell us what it was like to scuba dive there or what local industry used to be like. That's important; at one point the book talks about the problem of people accepting the state of things now as normal rather than wrong.

What really sticks in my head is the evidence, from several different cases around the world, that the ocean can recover - at some speed - if given the chance. There are some extraordinary examples recounted. I was especially wowed by the success of the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project, off the coast of Selsey and Shoreham where I spent holidays in my childhood. It's so vividly described, I could see myself barefoot on those beaches littered with kelp from a storm, and then diving in the depths to see the replenished riches of the underwater world.

Whereas Earthrise was pessimistic, this compelling story is full of hope.

June 18, 2025

Earthrise, by Robert Poole

I read an earlier version of this book more than a decade ago as prep for The Scientific Secrets of Doctor Who, and it's never really left my imagination. Poole, who is emeritus professor of history at the University of Central Lancashire (where I was an undergraduate, though I don't think we've ever met) recounts how the space programme affected our sense of ourselves by focusing on the famous "Earthrise" photograph, snapped by William Anders on Christmas Eve, 1968 while on Apollo 8 - the first crewed mission to the Moon.

I read an earlier version of this book more than a decade ago as prep for The Scientific Secrets of Doctor Who, and it's never really left my imagination. Poole, who is emeritus professor of history at the University of Central Lancashire (where I was an undergraduate, though I don't think we've ever met) recounts how the space programme affected our sense of ourselves by focusing on the famous "Earthrise" photograph, snapped by William Anders on Christmas Eve, 1968 while on Apollo 8 - the first crewed mission to the Moon.To place this in context, we begin with the history of conceptions of what the Earth would look like seen from space from before we could take pictures from orbit. The same characteristics recur in old pictures and descriptions: the prominence of landmasses, the lack of cloud, the theory that there would be blinding glare from reflected sunlight in the sea. As I said in Scientific Secrets, we're familiar with this kind of vision of the Earth in the logo of Universal Pictures, with rich green and brown land forms dominant over oceans of deep blue. A fixed shape and structures with no sign of change other than the globe slowly turns.

Instead, with Earthrise and subsequent images, we now know a bright, white-blue world with swirling, active clouds. No two pictures of the Earth from space are ever the same because those clouds are constantly moving, and - as Poole delineates - because the planet is in flux. More of that in a moment.

Before getting to Earthrise, Poole details the efforts to get the first cameras into space, and the perhaps greater challenge of doing something counter-intuitive and pointing them back towards the Earth. The politics or scientific merit of that is just one issue. Poole also explains the complex physical and chemical processes involved in ensuring a camera can survive spaceflight, and a picture can be taken and developed - in the days before digital - and then communicated back to Earth's surface. Thanks to him, a blurry, streaked image of cloud becomes an object of wonder when we understand how miraculous it was to capture any image at all.

How fascinating to learn that there is no consensus on the first photograph to show the curvature of the Earth. As Poole says, the round Earth was known to the ancients. It's an observable phenomenon by watching boats on the sea: masts appear first over the horizon, then the hulls, rather than the whole boat appearing at once in the distance as it would if the sea were flat. I remember standing at Logan's Rock in Cornwall as a kid, looking down on the seaward horizon, and holding up a ruler to better see the curve of that line of sea. Are there really no early photographs of such vistas?

According to Poole, though, "the first photograph clearly to show the curvature of the Earth" (p. 34) was taken by the aeronauts on board Explorer II on 11 November 1935, which launched from the "Stratobowl" in the Black Hills of South Dakota and reached an altitude of 13.6 miles (22 km). The photograph they took was published in National Geographic the following year.

Another notable early effort was took place on 24 October 1946, when a V-2 rocket launched from the army's White Sands proving ground in New Mexico was fitted with a 35mm movie camera. The resulting images, from some 65 miles up, made the papers and newsreels.

I thought this might be the footage used in the opening moments of The Quatermass Experiment (1953), but checking Toby Hadoke's book reveals this was from a later V-2 launched at the same site on 17 February 1950 (see Hadoke, p. 133).

A set of photographs taken by a V-2 camera on 26 July 1948 were stitched together to create two panoramas of the curving Earth, released to the press on 19 October. Poole says that this, "was accepted in the press and the archives as 'man's first view of the curvature of the Earth', an official position it has held ever since" (p. 37). But, as he continues, the fact that there's any doubt at all is evidence that these different images, for all they were published to some acclaim, didn't quite catch on as later images did.

Various factors explain why the Earthrise image had the impact it did. It's a good quality, high resolution image, for one thing, which reproduces well. While there's no "up" or "down" in space, it's usually presented with the lunar landscape in the lower part of the frame, creation a boggling inversion of our usual view of the Moon in the sky above our own horizon. There's also the juxtaposition of the bright, coloured Earth with its whirling, active cloud and the grey, desolate Moon.

But Apollo 8 as a whole made people sit up and take notice. As James Burke recalled in Our Man on the Moon, suddenly people realised, "Hey, they're really going to land on the Moon!" Burke was swiftly told to swot up on rocket science so that he could present the BBC coverage. So I think Earthrise was also emblematic of the Moon landings becoming, well, real.

Poole then charts the impact that Earthrise had on Earth, galvanising the environmental and ecological movements and having a direct influence on the first Earth Day, held in 1970, and conceptions of Earth as either spaceship or mother-Gaia. This is the stuff I really remember from reading this last time and - as I argued in Scientific Secrets - is all over the Doctor Who of this period. In fact, the first Doctor Who story shown after the Moon landing, and ushering in a new era of the series, begins with a view of the whole Earth from space, the first to appear in the series, and in colour, too. That's made me think about the mechanics of replication: how much the impact of Earthrise owes to good quality colour print in newspaper supplements and magazines, and the spread of colour TV.

All in all, this book presents a fascinating, wide-reaching history, full of tenacious characters, not all of them heroes. I didn't know, for example, that Fred Hoyle was an anti-environmentalist who even accused Friends of the Earth of operating on behalf of "their Russian paymasters" to deprive the west of energy (p. 4); he had to withdraw the allegation.

It's a self-published book, and there are typos and artefacts littered through the text. Perhaps a judicious editor might also have questioned the description of those suggesting that the Moon landings might have been faked as "fuckwit denialism" (p. 76) - though I can imagine other science writers putting it in similar terms. Really, all I mean is that this compelling book deserves another, more polished edition, perhaps including colour plates of the images under discussion.

Last time, what hit me about this book was the way leaving Earth - and looking back at what we left - transformed our sense of and relationship to our planet. That's still here, updated to include William Shatner's response to his own real-life trek into orbit in 2021. He was profoundly moved, and saddened, by the fragility of Earth in a universe of cold, dark nothing. What hits me reading this edition is the same profound sense of loss. The images of Earth from space taken since Earthrise show the damage we have inflicted in the intervening years: the melting ice caps, the loss of vegetation on vast scales, the ferocity of the weather we once never even thought of in our conceptualisations of Earth.

"Humankind now appears to be both the product and the custodian of the only island of intelligent life in the universe that we will ever encounter. Whether that vision has been timely enough, and powerful enough, for homo sapiens, the most successful of all invasive species, to reverse its own devouring impact on the Earth, will be known soon. Perhaps we know already." (p. 177)

More space stuff by me:

Carrying the Fire, the autobiography of astronaut Michael Collins On 2007 documentary In the Shadow of the MoonMoondust, by Andrew SmithApollo, by Fitch, Baker and CollinsOrbital, by Samantha HarveyAd Astra, by Dallas CampbellMy trip to Kennedy Space CenterOn Yuri Gagarin's autograph in CroydonJune 17, 2025

Ace Jacket - The Inside Story

Published today to raise money for autism charities, Ace Jacket - The Inside Story is an A4 softback boasting more than 250 pages of original stories, pieces, artwork and photographs relating to Doctor Who companion Ace and her iconic badge-bedecked jacket.Buy Ace Jacket - The Inside StoryThe book features a foreword by the Tenth and Fourteenth Doctors, David Tennant, and an afterword by former Doctor Who executive producer Chris Chibnall. There are contributions from Peter Davison, Colin Baker, Sylvester McCoy, Peter Capaldi and Jodie Whittaker, as well as - it says here - "companions, past showrunners, writers, producers, villains and monster makers".

Published today to raise money for autism charities, Ace Jacket - The Inside Story is an A4 softback boasting more than 250 pages of original stories, pieces, artwork and photographs relating to Doctor Who companion Ace and her iconic badge-bedecked jacket.Buy Ace Jacket - The Inside StoryThe book features a foreword by the Tenth and Fourteenth Doctors, David Tennant, and an afterword by former Doctor Who executive producer Chris Chibnall. There are contributions from Peter Davison, Colin Baker, Sylvester McCoy, Peter Capaldi and Jodie Whittaker, as well as - it says here - "companions, past showrunners, writers, producers, villains and monster makers". I wonder which one of those I count as. My contribution is on Flowerchild's time-travelling earring.

Fittingly, the book will soon have a companion volume, Ace Jacket - The Outside Story , which details the onscreen appearance of Ace's jacket (or jackets plural) in ferocious detail. It is published on 25 November but you can pre-order it now.

The New Forest Murders, by Matthew Sweet

The wife and children were generous with my annual appraised (or "Father's Day"). I got a lie in, a badge of a smiley fried egg, a copy of my friend Matthew Sweet's new novel and - best of all - the chance to sit and read it. What joy.

The wife and children were generous with my annual appraised (or "Father's Day"). I got a lie in, a badge of a smiley fried egg, a copy of my friend Matthew Sweet's new novel and - best of all - the chance to sit and read it. What joy."There is a village in England that all us know, even if we have never set foot there. The village that comes to our minds when we think of cricket on the green on a Sunday in July; when we see a honeysuckled cottage painted on the lid of a tin of biscuits; when we put our hands together and say, 'Here's the church and here's the steeple.'"It really exists." (p. 125)

This village is in the New Forest, near where I grew up. Characters speak of the bright lights and bustle of Southampton, where I went to school. But this particular village is familiar from a whole load of other sources, too - Larkwhistle here in 1944 owes something to Bramley End in Went the Day Well (a film released in 1942 but set after the end of the Second World War, so told to us from the future). Meanwhile, local pub the Fleur-de-Lys is straight out of Doctor Who and the Android Invasion (1975), in which the real-life East Hagbourne doubled for fictional Devesham.

It's a mix of spy story, murder mystery and romance, neatly acknowledging its sources from the dog called Wimsey after Dorothy L Sayers's detective to more than one Sherlock Holmes reference.

"That's a bit dog-that-didn't bark, isn't it?" (p. 154)

The blurb of the book says it is "perfect for fans of Agatha Christie's Partners in Crime". The church of St Cedd surely owes something to Dirk Gentley's Holistic Detective Agency by Douglas Adams, and at one point there's a joke from Doctor Who and the State of Decay; I think the author of that story, Terrance Dicks, would have loved this.

As for the plot: it's 1944 and Normandy has been invaded, the last act of the war under way. But Jill Metcalfe and her father then receive bad news from a rather good-looking American officer, Jack Strafford. While they're reeling from the shock, word comes of a dead body under a tree. It's not just any body, or just any tree - and soon Jack and Jill are working together to solve a murder and to catch a spy, which may or may not be related...

The book rattles along - I finished it in a day - by turns funny and real and harrowing. You feel the loss, and the great depths of emotion in this apparently quiet, conventional setting. Oh, and the back-flap tells us what is surely another influence on this: Matthew's forthcoming book The Great Dictator (haha!) is a biography of Barbara Cartland.

June 13, 2025

Target Book Club, 19 July 2025

James Goss, the master brain behind Target Book Club, a celebration of the Doctor Who novelisations, has announced that I'm one of this year's speakers.

James Goss, the master brain behind Target Book Club, a celebration of the Doctor Who novelisations, has announced that I'm one of this year's speakers.Target Book Club takes place from 10 am on Saturday 19 July 2025 at the Abbey Centre, 34 Great Smith Street, London.

Buy tickets for Target Book Club 2025My 15-minute talk, "The Unseen Terrance Dicks", will include some newly discovered facts about the most prolific of the Target authors. "Secrets from his files," says James. Yes, indeed.

I'm reading a lot of Terrance's work at the moment and blogged on his novelisation of The Wheel in Space just last week. You may also enjoy this 2015 interview I conducted with Terrance, in which he told me - very amiably - that I was talking nonsense.

June 12, 2025

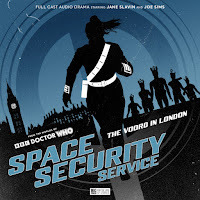

Space Security Service title sequence

The first volume of Space Security Service is out today from Big Finish. This new audio series, which I produced, comprises three adventures of space cops Anya Kingdom (Jane Slavin) and Mark Seven (Joe Sim), who used to travel with Doctors Who and are now on missions of their own.

The first volume of Space Security Service is out today from Big Finish. This new audio series, which I produced, comprises three adventures of space cops Anya Kingdom (Jane Slavin) and Mark Seven (Joe Sim), who used to travel with Doctors Who and are now on missions of their own.To accompany the release, Rob Ritchie has produced a title sequence to match Jon Ewen's amazing theme tune for the series:

Full blurb as follows:

They’re the guardians of the Solar System and Earth’s first line of defence. But now the agents of the Space Security Service face their greatest ever threat…

Anya Kingdom (Jane Slavin) and the android Mark Seven (Joe Sims) are the top agents of the Space Security Service, fighting alien threats and sinister villains across the galaxy.

Last encountered in the Dalek Universe story arc, in which they teamed up with the Tenth Doctor, these popular characters now star in their own spin-off series of full-cast audio dramas, inspired by the 1960s Doctor Who serials of Terry Nation.

The thrilling retro-styled adventures of the Space Security Service begin today with a box set of three brand-new stories, which take Anya and Mark to London in the 1980s, a Thal planet where a scientist conducts dangerous experiments, and a world on the brink of war.

The Worlds of Doctor Who – Space Security Service: The Voord in London is now available to purchase for just £19.99 (as a digital download to own), exclusively from Big Finish.

The SSS’s three latest missions are:

The Voord in London by LR Hay

1980s London. WDC Ann Kelso is assigned to CID, helping to clean up the streets. But “Ann” is really SSS Agent Anya Kingdom from the 41st century, on a top-secret mission to track down aliens hiding in the past. But then she finds a different group of aliens hiding in the Thames – with very deadly intentions…

The Thal from G.R.A.C.E. by Felicia Barker

As their investigations continue, SSS agents Anya Kingdom and Mark Seven journey to a planet colonised by Thals. They’re in pursuit of a Thal scientist who has perfected an experimental new weapon… But soon they are the targets…

Allegiance by Angus Dunican

The lush planet Othrys is on the cusp of civil war. SSS agents Anya Kingdom and Mark Seven are meant to keep a low profile while on a diplomatic mission there… But when a pregnant surrogate for the Othryn royal family desperately asks for their help, they’re unable to refuse…

Joining Jane Slavin and Joe Sims in Space Security Service: The Voord in London are Sean Gilder (Slow Horses), Madeline Appiah (Jungle), and Lara Lemon (Insomnia). The guest cast also includes Rodney Gooden, David Holt, Nicholas Briggs, Camille Burnett, Peter Bankolé, Jez Fielder, and Barnaby Kay.

Cover art by Grant Kempster. Script editor John Dorney, director Barnaby Kay and executive producers Jason Haigh-Ellery and Nicholas Briggs.

June 9, 2025

The Legend of Nigel Kneale 2. Enemy From Space

The super deluxe collectors' edition of Quatermass 2 is now available to pre-order from Hammer Films. It's released next month.

The super deluxe collectors' edition of Quatermass 2 is now available to pre-order from Hammer Films. It's released next month.Among the many goodies included in the set is the second part of the documentary me and Brother Tom have produced with Eklectics about Quatermass creator and writer, The Legend of Nigel Kneale.

As with the first part, included on the collectors' edition of The Quatermass Xperiment, the documentary is presented by Toby Hadoke and includes interviews with Kneale's biographer Andy Murray, Dr Tom Attah, Joel Morris, Brontë Schiltz and Jane Asher. This second part also includes two other on-screen contributors... but wait and see.

June 5, 2025

Smith & Sullivan cover reveal

Big Finish have shared the cover artwork for Smith & Sullivan: Reunited, the Doctor Who spin-off audio set out next month which includes my story, Blood Type, as well as stories by Tim Foley and Roland Moore. The art is by Ryan Aplin.

June 3, 2025

The Wheel in Space, by Terrance Dicks

The latest issue of Doctor Who Magazine comes with this exclusive edition of The Wheel in Space by Terrance Dicks, which I’d never read before. I flicked through the opening pages, found myself ensnared and raced on to the end. Breezy, is the word. Six episodes of TV adventure in just 136 pages. Deceptively straight-forward.

The latest issue of Doctor Who Magazine comes with this exclusive edition of The Wheel in Space by Terrance Dicks, which I’d never read before. I flicked through the opening pages, found myself ensnared and raced on to the end. Breezy, is the word. Six episodes of TV adventure in just 136 pages. Deceptively straight-forward.In fact, there’s a lot going on here.

For one thing, there’s why you’d republish this particular novelisation. First published in hardback on 17 March 1988, in paperback on 18 August the same year, it wasn’t reprinted until 2021. Second-hand copies of the first edition were notoriously tricky to find. Over the years, I’ve cooed at rare specimens in specialist shops, well beyond my price range. It’s why, during lockdown, fans voted this one of 10, out of his 64 Doctor Who novelisations, to be republished as part of The Essential Terrance Dicks collection.

Except now I gather that the first edition wasn’t especially rare: print runs weren’t any different from other novelisations, and stocks of this book in particular weren’t decimated by a fire at the warehouse. Was it hyped? Was there a conspiracy? It would have to be quite a convoluted plot.

The Wheel in Space was the 61st of Terrance’s novelisations. In the Essential collection, ordered by broadcast dates of the TV stories they’re based on, it is followed by his very first (Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion (1974), based on Spearhead from Space). But the TV story The Wheel in Space was also Terrance’s first Doctor Who story — he seems to have joined the production team as assistant script editor just before the start of production on 18 March 1968.

The TV story was written by David Whitaker, the original story editor of Doctor Who — in effect, Terrance’s ancestor in the role. The closing episode led into a repeat of The Evil of the Daleks, also by Whitaker (the novelisation given away free by DWM last year). Wheel begins with our last sight of companion Victoria Waterfield and then introduces her successor Zoe Heriot, before segueing into the repeat — Victoria’s first story.

Round and round we go. Terrance seems to have been conscious of this muddling of chronology: on the last page of the novelisation, as Zoe is welcomed into the TARDIS, Jamie feels a pang.

“Jamie realised that the Doctor was telling Zoe the story of one of their recent adventures, the one in which they’d first met poor Victoria. … Jamie wondered if Victoria was happy in her new life. He hoped so. Curiously, he was finding it hard to remember her face — especially with Zoe’s vivid little face gazing enthralled at the screen.” (p. 136)

The novelisation of The Wheel in Space was also the first novelisation to feature the Second Doctor written after the death of actor Patrick Troughton. He died on 28 March 1987 while a guest at the Magnum Opus II science-fiction convention in Georgia, USA; he’d been due to return to the UK for a costume fitting for his role as grotesque old letch Lord Steyne in the BBC’s epic 16-part TV serialisation of Vanity Fair — produced by Terrance.

Given what we know about Troughton’s, ahem, complicated love life, was there something pointed in assigning him that role?

When he died, John Shrapnel took the lecherous role. In the cliffhanger ending to episode 13 of Vanity Fair (tx 29 November 1987), Captain Rawdon Crawley (Jack Klaff) catches his wife Becky Sharp (Eve Matheson) in the arms of Lord Steyne and all hell breaks loose. The morning after broadcast of these shock events, Terrance and Eve Matheson appeared on the BBC’s live phone-in show, Open Air, to discuss the scandal — and attempt to boost flagging ratings.

Terrance had already made two appearances on the same programme that year. He sits there, bemused, fielding awkward questions from viewers — and the hosts. It’s just as uncomfortable and clunky as footage from around the same time of him at Doctor Who conventions. By this point, Terrance had worked out how to play these kind of events. He seems quite at ease answering questions about the TV scene that should have starred his dead friend, the star of the first Doctor Who story he worked on, the novelisation of which Terrance must have delivered around this time.

So much about this book is, well, odd.

From what I can gather, Terrance seems to have aimed for 100 pages of typescript per Doctor Who novelisation. He’d source videotapes of the surviving episodes and work from the scripts of the rest — largely supplied by the BBC but sometimes by acquaintances in fandom. There are 18 chapters in this novelisation and he clearly divided each of the six TV episodes into three.

Split evenly over 136 pages, that should mean 22.7 pages per episode. In fact, Episode 1 comprises 25 pages, Episode 2 is 22 plus a blank page, Episode 3 is 24 — so it’s slightly more dense in set-up and then accelerates in the second half.

Even the set-up is concisely done. He captures us from the first simple, vivid sentence — “Victoria was waving goodbye.” Then we rattle into the episode, now missing from the archive, as per the camera script. The Doctor and Jamie, at the console of the TARDIS, watch Victoria fade from the screen. On TV, there was then a fade out before the next scene, also set in the TARDIS control room, with Jamie now asleep on a chair to emphasise the passage of time.

Terrance follows that structure but feels the need to explain what’s happening, succinctly.

“Like the good fighting man he was, Jamie took every opportunity for a nap.” (p. 3)

It’s a quick, nimble fix for this particular transition — but is it really true of the character? By “took every opportunity for”, read “never takes”.

There’s then some attempt to explain sci-fi things from Jamie’s 18th-century perspective, such as their arrival on the spacecraft Silver Carrier:

“He was in a kind of metal cave, surrounded by massive metallic shapes.” (p. 7)

But Jamie doesn’t think of the TARDIS control room as a cave; he’s well used to travel in that particular space (and time) craft. He has also learned about other spacecraft — though he doesn’t go aboard — in The Moonbase and The Tomb of the Cybermen (both 1967), the two Cybermen stories that precede The Wheel in Space. It’s not how he was written on TV at the time, where they recognised that he developed while travelling with the Doctor. But writing him in retrospect, Jamie is defined by his origins. (I think something similar happens in the way he is written in 1985 TV story The Two Doctors.)

“A kind of metal cave,” is not especially specific or vivid, and we see similar vague, handwaving descriptions from Terrance later — “Somehow it was clear…” (p. 15), “Some kind of alien eggs…” (p. 18) etc. On page 20, he makes an ordinary item a bit more futuristic by referring to a “space blanket”. He also explains why Jamie picks up this item when he hears the injured Doctor cry out, so as to have it conveniently in his hand when confronted by a robot.

“Snatching up the blanket — he had a confused idea that the Doctor ought to be kept warm — Jamie shot out of the cabin and into the corridor…” (p. 20)

The same page includes a sudden shift in perspective: we follow events as seen by the Doctor and then, in a cliffhanger moment, shift to the robot’s perspective. I think it works rather nicely here but also know that it could throw readers. Not too long after this, the editorial team of Doctor Who books made a ruling that each section needed a single point-of-view.

Having glimpsed Zoe Heriot on a video screen on p. 37, we meet the Doctor’s new companion properly on the next page, from Jamie’s perspective — where he self-corrects his own first impression.

“Behind the desk sat a very small girl, or rather a young woman. She wore the same black and white coverall outfit as everyone else on the Wheel” (p. 38)

I think this is Terrance consciously making Zoe older than she was meant to be on screen — a woman, not a teen. He puts her in black-and-white, like the other, adult characters, not the more childish pink version actress Wendy Padbury actually wore (as seen in Dan Liles’s cover artwork for this new edition). I’ll come back to why I think Terrance did that…

On screen, there’s a moment in this first meeting where 18th century Jamie threatens to “larrup” Zoe, and she simply laughs. It’s a sign of her strength that she isn’t threatened in the slightest — we learn in later stories that she can defend herself with martial arts. I wonder how much this light-hearted threat inspired writer Dick Sharples, whose nearly-made Prison in Space ends with Jamie delivering on his promise. (No, being a call-back to this episode doesn’t excuse it.)

Twenty years after broadcast, Terrance didn’t think better of Jamie’s threat to larrup Zoe; it’s in the novelisation. I think the argument could be made that, again, it’s true to Jamie’s 18th-century character. It’s still odd to read in a book ostensibly written for children.

The colour — or lack of it — of Zoe’s outfit can be explained by the fact that the story was made in black and white. Terrance may have based the description on the two surviving episodes that he rewatched on video rather than what he remembered from production 20 years before. Where episodes weren’t available, he worked from surviving camera scripts, in this case working round some odd “ghosts” from earlier drafts.

Several characters were renamed in rehearsals to make the Wheel more multi-ethnic, but the original names still often appear frequently on the page. Gemma Corwyn was originally Nell (the name of writer David Whitaker’s mother-in-law); Tanya Lernov was originally Tanya Lerner; Enrico Casali was Harry Carby; Chang was Ken; Captain Leo Ryan was Tom Stone — perhaps a relation to the Stone family from The Dalek Book (1964), also written by Whitaker.

In writing the TV episodes, Whitaker worked from a storyline provided by Cyberman creator Kit Pedler, but there’s lots here I think is directly him. For example, the Venusian flowers are like the alien flora of his The Daleks comic strip. Then there’s something we’re sold as space-age psychology but I think is really the mentality of someone who grew up during the Second World War and wouldn’t dare waste food. Perhaps it’s an echo of something David heard from Nell:

“GEMMA: [Jamie] asked me for a drink of water and then he left it. He might have been on Earth. That boy's has no space travel training, Jarvis.” (Episode 2)

So I read this trying to sift what was Terrance, what Whitaker, what the ur-text of Kit Pedler. Pedler’s storyline must have had the Doctor and Jamie suspected of sabotage and kept confined; Whitaker also needed them out on the Wheel to uncover clues. That means, a bit awkwardly, Jamie is sometimes escorted to other parts of the Wheel, and then he and the Doctor are simply no longer kept under guard — “apparently restored to favour” as Terrance says in an aside (p. 90), with what I think might be a roll of the eyes.

He doesn’t comment on another aspect of the TV story, but my sense is that he didn’t approve of stuff about brainwashing children. This is the dialogue as broadcast in Episode 4:

ZOE: Leo said I was like a robot, a machine. I think he's right. My head’s been pumped full of facts and figures which I reel out automatically when needed. But, well, I want to feel things as well.

GEMMA: Good. Unfortunately the parapsychology unit at the city tends to ignore this aspect in its pupils. Some of them never fully develop their human emotions.

ZOE: You don't think I'll be like that, do you?

GEMMA: No, no: you seemed to have survived their brainwashing techniques remarkably well.

Though Zoe’s age wasn’t given on screen in Doctor Who, publicity material of the time said she was 15. She’s a schoolgirl, conditioned by her futuristic school to behave like a machine. Over the course of this story, we learn that such logical conditioning means she’s incapable of dealing with unexpected phenomena — such as the baroque plotting of Cybermen. As the Doctor says, logic “merely enables one to be wrong with authority.”

Jarvis Bennett, the Controller of the Wheel, is similarly afflicted, unable to believe what’s really happening. I wonder if Kit Pedler meant him to be have been schooled by the same system, as part of some broader point about the importance of critical thinking, of education needing to be more than the recitation of facts.

Terrance cuts the dialogue back so we learn that Zoe is brainwashed but are not told where. As I said before, Jamie corrects himself about Zoe: she is a “young woman”, not a girl, so there’s no suggestion that she was brainwashed at school. Perhaps Terrance thought the idea too unsettling for young readers; perhaps he thought it too pointed a comment about education policy. Whatever the case, there’s a tension here between the different authors of this story.

The latest issue of Doctor Who Magazine, which furnishes this new edition of the novelisation, reveals another author. Editor Steve Cole says:

“It felt to me as if the original manuscript was barely edited at all. Paragraphs and separate sections run into each other. At one point a Cyberman descends some steps although it is standing at the top of them, then descends them again. The phrase ‘his body went rigid’ appears twice in five lines. And poor Tanya Lernov! An astrogator on screen, in prose she is demoted to ‘Astrologer, second class’.”

He says Terrance once told him that he wished he’d been more robustly edited, which Steve has borne in mind in preparing this new edition. He indicates some differences from the version in The Essential Terrance Dicks, where the scan of the original copy produced a few small errors. I don’t have the first edition to check whether any of the things I note here are new inventions.

I’ve been chatting about some of this stuff with the very patient Steve — my editor, too — as part of something else I’m working on. That is, I’m in dialogue with my editor about him editing our late friend Terrance Dicks, who was in turn editing a story by his own predecessor, Doctor Who’s first story editor David Whitaker. This breezy novelisation is a direct conduit to the past: relive a lost TV story, commune with the people who made it.

That’s the electrifying sense I got as I flicked through the opening pages and then couldn’t stop.

Contact.

See also:

My biography of David WhitakerOn Doctor Who - The Time Warrior (1978) by Terrance DicksOn Doctor Who - The Five Doctors (1983) by Terrance DicksOn the making of the BBC's Vanity Fair (1987), produced by Terrance DicksOn Shakedown - Return of the Sontarans (1994) by Terrance DicksOn Doctor Who - Made of Steel (2007) by Terrance DicksThe Life and Times of a Doctor Who Dummy, by Robin Squire, one-time assistant to TerranceCybermen - The Ultimate Guide (includes me on the design of Cybermen in The Wheel in Space)Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers