Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 9

January 27, 2025

Power of 3 podcast #351: The Time Travellers

The latest episode of Kenny Smith's Power of 3 podcast is about my Doctor Who novel The Time Travellers, first published in 2005 and so 20 years old. (Of no interest to anyone, but I delivered the first draft on 29 April 2005, the day before Dalek was broadcast.)

The latest episode of Kenny Smith's Power of 3 podcast is about my Doctor Who novel The Time Travellers, first published in 2005 and so 20 years old. (Of no interest to anyone, but I delivered the first draft on 29 April 2005, the day before Dalek was broadcast.)The episode includes an interview with me, struggling to remember whatever it was I was thinking at the time - other than "Eeeeeeeee I'm writing a book!"

Last year, I spoke to the same podcast about my 2007 Doctor Who novel The Pirate Loop and, separately, my new book Doctor Who - The Time Travelling Alamanac. And the year before, I spoke to them about David Whitaker in an Exciting Adventure with Television.

January 18, 2025

A Doctor Who pitch: Perfect Worlds

Yesterday, while searching for something else I came across five one-paragraph ideas for Doctor Who audiobooks that I submitted on Sunday, 15 November 2009, a few hours before settling down to watch The Waters of Mars.

One of the five ideas is striking. I had no idea at the time that Amy’s Choice had been commissioned for the 2010 TV series and this was all a long time before the Dream Crabs featured in Last Christmas (2014). But, by total coincidence, I came up with something a bit similar:

Perfect Worlds

A sort of ghost story. Amy and the Doctor rescue each other from their dreams. After finally leaving the Doctor behind, Amy is back home with her friends – human ones and those she’s met on her adventures with the Doctor. It’s a nice day and there’s a big party. But some of the friends she knows are really dead. And then the Doctor comes to see her. He explains she’s asleep, she’s been bitten by something that’s feeding off her dreams – and is slowly killing her. He’s using a machine to speak to her: and by willing to wake up she can. The Doctor shows her the small, scaly creature feeding on their desires. And it bites him. Amy now has to go rescue him… He dreams of his own home and the thousands of people who he couldn’t save, all living happily together. Amy talks him out of staying.

This happens quite a lot: more than once I’ve been told I can’t do X or Y in a Doctor Who story because someone else is already doing it or something like it in another story I didn’t know about. As an editor and producer, I’ve sometimes had to tell people the same thing. There is a lot of Doctor Who being dreamt up all the time, so it’s not really surprising.

But on this particular occasion I don’t think I was made aware that I’d chanced upon the wheeze of a forthcoming TV episode. And by the time Amy’s Choice was broadcast on 15 May 2010, I’d forgotten having a similar idea.

That’s probably because I was a bit caught up in other things at the time. But it’s also how pitching works: if the people you’re pitching aren’t enthused by what you send in, you send in something else. Ideas are the easy bit. If there’s interest in an idea you then move on to the trickier thing of developing it into a storyline.

I sent in some more ideas and one of those eventually became

The Empty House

, released in September 2012.

I sent in some more ideas and one of those eventually became

The Empty House

, released in September 2012. But I realise (having had it pointed out) that I then worked some of this Perfect Worlds idea into The Anachronauts, released in January 2012. In fact, another of the pitches sent in with Perfect Worlds was called The Deluge and reworked an outline for a Doctor Who novel I’d submitted in the early 2000s. That idea eventually ended up as The Flood, an episode of my science-fiction series Graceless, released in December 2011.

The three other ideas — Snip! Snip!, 77 Aliens and The Brain Drain — might still find homes somewhere… Never throw anything away, Harry.

This morning, out for a walk, I puzzled over where the wheeze for Perfect Worlds came from in the first place. At the time, one trick I used for sparking ideas was to scan over my shelves of books and DVDs. It wasn’t always to come up with, “A Doctor Who version of X…” Often just being reminded of a scene, a character, a line of dialogue would ignite something.

With that in mind, I think Perfect Worlds was probably inspired by the 1986 movie Labyrinth, especially the “As The World Falls Down” sequence at the ball — hence Amy being at a party — and the bit when Sarah thinks she is back in her room but it’s yet another trick. She has to puzzle out, for herself, the difference between the comforting and the real…

Maybe I’d been told, or picked up somewhere, that the 2010 series of Doctor Who would have something of a fairy-tale feel. If so, I was trying to get myself in the right kind of head space to match that — and that’s why this idea came so close to what they were already doing.

January 10, 2025

Someone from the Past, by Margot Bennett

Nancy Graham, 26 year-old magazine writer and the narrator of this novel, is out for dinner with her fiancee Donald when they bump into Susan Lampson. Nancy used to share a flat and work with Susan but they’ve not seen each other in a while. To complicate matters, Donald used to go out with Susan and when she left him tried to shoot himself.

Nancy Graham, 26 year-old magazine writer and the narrator of this novel, is out for dinner with her fiancee Donald when they bump into Susan Lampson. Nancy used to share a flat and work with Susan but they’ve not seen each other in a while. To complicate matters, Donald used to go out with Susan and when she left him tried to shoot himself.Now Susan is marrying someone else — but, she tells Nancy, she’s received a threatening note from an ex. Susan wants Nancy, who kept notes in shorthand on Susan’s love-life when they lived together, to seek out her exes and find out who is making trouble. It might be the convicted thief Peter or the poet Laurence or the vain actor Mike… Nancy is sure it can’t be Donald.

When Susan is murdered, Nancy’s first thought is to ensure that the police don’t suspect her fiancee. But in tidying up the crime scene to protect Donald, she incriminates herself…

This is a fantastic return to form by Margot Bennett after the disappointment of Farewell Crown and Good-bye King. It’s at least as good as The Widow of Bath and probably better, my favourite of her books that I have read so far. I can see why it won the Crime Writers’ Association ‘Crossed Red Herrings’ award — since renamed the Gold Dagger (and presented to Bennett by JB Priestley) — and why Bennett was, in 1959, elected to the Detection Club. Fast-moving, twisty and suspenseful, this keeps us guessing to the end. Even the very last paragraph takes an unexpected turn.

In his introduction, Martin Edwards quotes Bennett herself on what made this and The Man Who Didn’t Fly “my best books”. The latter,

“had an unusual plot and a set of people I believed in. In the same way, Someone from the Past had five characters I might have met anywhere. The best of all my people was the girl Nancy. She was kind and cruel, and loyal and bitchy. She was a ready liar, with a sharp tongue, but she was brave and real. All through my books, the best I have done is to make the people real.” (pp. 9-10, citing John M Reilly (ed.), Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers)

Nancy is a compelling protagonist. We never know what she might do next. She is observant and reckless, intelligent and yet capable of extraordinary folly. Sometimes she tries to fix things in ways we can see (and want to shout) will only make things worse. But we are with her all the way as she faces multiple dangers.

As so often with Margot Bennett, characters attracted to one another bicker and fight, but here the stakes are raised because any one of these men Nancy is winding up could be the murderer. Whether or not they did for Susan, they can be violent with Nancy, or treat her appallingly in other ways. In fact, she is not the only woman here who puts up with variously crap men.

This British Library Crime Classic edition, first published in 2023, is subtitled “a London mystery” and it boasts a few good descriptions of places such as Soho. More than that, it offers an extraordinary snapshot of the mores of 1958, the year the novel was originally published. As well as a lot of smoking and drinking, there’s a surprising nonchalance about drugs. Tired and wound-up after a row with Donald, Nancy tells us:

“I knew I should take a couple of strong sleeping-pills. They would give me four hours’ sleep, and a heavily-doped morning that would make work impossible, unless I took a stimulant. After that, a couple of tranquilizing tablets would level me up for the day.” (p. 37)

She has all of these to hand as, a few pages later, she offers them and “a confidence drug” to her fiancee, who tells her he’s already taken “knockout pills” (p. 45). These, we learn, are “blue things, sodium amytal” (p. 47). Elsewhere, Nancy seems familiar with benzedrine. The drug-taking is part of the plot (one suspect was apparently doped and unconscious at the time of the murder) but also part of everyday life.

I’m intrigued by elements of the novel that Bennett may have drawn from her own (fascinating) life, such as her years as a writer for the magazine Lilliput (while her husband Richard Bennett was editor).

“From the moment that I got the job on the Diagonal Press and scrawled out my first paid illiteracies I saw myself as a great writer, one who kept notebooks and would soon be guest of honour at literary luncheons.” (p. 27)

Again, the notebooks are part of the plot but I wonder how much this attitude — to her earlier work and to her career — matched Bennett’s own. When the murder case bears down on Nancy, the publisher she works for offers her a chance to get away with a job in Spain (p. 248). Is that a nod to Bennett’s own history, as she served as a nurse (and publicist) in Spain during the civil war?

Then there is what the novel says about Television, which in those days still had a capital T. Bennett had already made her debut as a TV writer: her one-off drama The Sun Divorce (dir. Philip Savile) was shown as part of London Playhouse on the ITV network Associated-Redifussion on Thursday 26 January 1956, just four months after the launch of ITV. Writing of Someone from the Past must have overlapped with the agreement of rights for a TV adaptation one of her earlier novels: The Man Who Didn’t Fly, starring William Shatner and Jonathan Harris, was adapted by Jerome Coopersmith and broadcast by NBC in Canada on 16 July 1958.

Since it was made and broadcast in Canada, Bennett probably had little involvement in this and she may never have seen it. But, excitingly, we can watch that production of The Man Who Didn’t Fly on YouTube. It even enjoys a bit of a following because it stars both William Shatner and Jonathan Harris, later stars of Star Trek and Lost in Space respectively.

Margot Bennett was soon writing for TV herself, with work on ATV soap opera Emergency-Ward 10, perhaps making use of her own nursing experience. IMDB credits her on 15 episodes of the soap, broadcast between Tuesday 23 September 1958 and Friday 22 May 1959. The implication is that she moved into soap opera soon after completing work on this novel.

By the time she finished on Emergency-ward 10, Bennett had made the switch to BBC — and more prestigious drama — with her six-part adaption of her novel The Widow of Bath, which began transmission on 1 June 1959. But Someone from the Past suggests she was already familiar with the mechanics of BBC television more than a year before that.

In the novel, actor Mike Fenby, presumably used to late nights on stage followed by late mornings (as described in Exit Through the Fireplace), complains of the “brutal creatures” of “Terrivision” who have him up at “ten o’clock” in the morning for rehearsals in Shepherds Bush — which is where the BBC was based.

“And you should see, I really wish you could see, the producer. Temperament! He thinks out the sets with a kind of telescope, and when he wants to concentrate, he blows bubbles. … He has a tin. He shakes the bubbles off with a bit of wire. They help him to relax. When they burst, they cover the floor with slime, like invisible banana skins. There’s practically no one in the cast who hasn’t a sprained ankle or a broken neck. You ought to see us, skidding about the place.” (pp. 39-40).

That “telescope” was a director’s viewfinder, enabling the director to see how much of the actors and set would be visible through different diameter lenses, and to plan and block their shots ahead of studio recording. Viewfinders had been in use since at least 1938: the Tech Ops site boasts a clipping from Radio Times that year, a photo of one in use and some other details. But this is not the sort of thing people outside the world of TV were likely to know about,.

Actor Mike can escape from rehearsals for lunch with Nancy at one o’clock, suggesting “a pub called the Blue Unicorn”, which is surely a play on the real-life White Horse at 31 Uxbridge Road, where I’ve also sometimes met up with actors. (For those with an interest in the drinking habits of old TV people, the late Alvin Rakoff says in his memoir of working for the BBC in the 1950s that after recording at Lime Grove he’d take the crew for a pint at the end of the road, in the British Prince at 77 Goldhawk Road.)

Later, Mike can’t believe Nancy didn’t see his TV performance go out.

“‘I thought you might have been interested enough to watch me on the new medium.’

‘It’s a fairly old medium by now, isn’t it?’

‘But Nancy, this was terrific. I’m a brain surgeon, you see, who takes to drink, and just when I’m having a terrible fit of the stagers, my former loved one is wheeled in with her brains dashed out. I’m supposed to shake so much, the forceps clash together like a steel band as I approach the operating table. The trouble was that I really was shaking so much I dropped the whole kit of instruments on her face. It was Sylvia, you know, she’s got a shocking temper, I cracked the porcelain jacket on one of her front teeth, she’s going to sue me. If I hadn’t got between her and the cameras and ad-libbed, the viewers would have heard every word she said. You certainly missed something. It will be in all the papers tomorrow.” (p. 95)

There’s a lot of interest here (to me): Television no longer a novelty, favouring melodramatic productions in which the viewer might enjoy the emotional crisis of characters in close-up, all within the lively, stressy chaos of live broadcast. The depiction is a bit pointed, even satirical — as is Mike buying up all the papers to bask in the contradictory reviews — but the details are all right, and so surely based on direct observation.

Did Margot Bennett have first-hand experience of BBC drama production when she wrote Someone from the Past, more than a year before her first writing credits at the BBC? Her husband had worked in BBC radio since the war and also sometimes wrote for listings magazine Radio Times, such as his interview with Jimmy Wheeler ahead of a TV comedy show in May 1956. Yet it seems unlikely that Margot tours of TV rehearsals through that connection.

More probable, I think, is this came through her own efforts. Was she meeting with BBC people about writing for TV, and getting tours of production, long before her first screen credit there? Or perhaps, like Nancy, Margot Bennett simply met an actor friend for lunch while they were in rehearsals…

Whatever the case, and for all Bennett might have mocked TV drama, something extraordinary happened after the publication of Someone from the Past. Despite the accolades it won, she never published another crime novel. According to her family (and detailed in the introduction to the British Library edition of The Man Who Didn’t Fly), she didn’t earn enough from novels to continue; crime didn’t pay. Instead, she spent the next decade writing prolifically for TV.

More investigation to follow...

Novels by Margot Bennett:

Time to Change Hats (1945); Away Went the Little Fish (1946); The Golden Pebble (1948); The Widow of Bath (1952); Farewell Crown and Good-bye King (1953); The Long Way Back (1954); The Man Who Didn’t Fly (1955); Someone from the Past (1958); That Summer’s Earthquake (1964); The Furious Masters (1968)Non-fiction by Margot Bennett:

The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Atomic Radiation (1964)January 3, 2025

Orbital, by Samantha Harvey

“Six of them in a great H of metal hanging above the earth. They turn head on heel, four astronauts (American, Japanese, British, Italian) and two cosmonauts (Russian, Russian); two women, four men, one space station made up of seventeen connecting modules, seventeen and a half thousand miles an hour. They are the latest six of many, nothing unusual about this any more, routine astronauts in earth’s backyard. Earth’s fabulous and improbable backyard.” (p. 2)

When this short, 136-page novel won the Booker Prize on 12 November 2024, I saw some commentary that it was clearly a work of science-fiction just not marketed as such — the implication being out of shame. Sci-fi, after all, is genre and lowbrow while this book aspires to art.

Having read it, I don’t think that’s true. Yes, it is set in the future — just — given that it includes the launch of the first crewed mission to the Moon in more than 50 years. In real life, Artemis III is currently scheduled to land the first woman and next man on the Moon in mid 2027 (I suspect it may be delayed). The typhoon that here devastates Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines is also a thing still-to-come — but given recent news of extreme weather in the UK and abroad doesn’t seem very distant.

More than that, I’d argue that the technology here, the apparatus of the world depicted, is as it currently exists. There is no “novum” or new wossname to differentiate this world from our own, a novelty whose consequence we then explore. Instead, the launch of the Moon mission, the typhoon and other things — such as the death of one astronaut’s mother down on Earth — help to clarify the sense of scale, distance, remoteness and connection of these six people aboard the small, creaky H. It shapes how we observe them and what they, in turn, observe.

The unnamed H space station here is not, explicitly, the International Space Station — which, in real life, has been permanently occupied by humans since 2 November 2000. But the tech and practicalities are the same. The novel details 24 hours on board, in which the H makes 16 orbits of Earth. We cover the crew’s schedule: scientific experiments, exercise regime, sleeping and toilet arrangements, a shared movie. We dig into their thoughts and fears and dreams. There’s a thing about exactly who and what is being observed in Las Meninas, the painting by Velázquez, as seen in a postcard on board the H. We skip occasionally back to Earth to get a contrasting viewpoint: the dying mother thinking of her daughter in space, the people sheltering from the devastating typhoon that, from orbit, looks serene.

In all this, I’m struck more than anything by a profound sense of fragility: the six people in their slowly eroding H; the people on Earth under threat from the elements; our relationships and loved ones and inevitable loss. So much meaning, all gained by taking a vantage point that provides perspective.

My copy of the book, published (very quickly!) after it won the Booker Prize, includes an afterword from the author which is just as insightful as the novel itself. It’s largely on the subject of what words can do and add and illuminate, as the poorer relation of music, but she also addresses the issues of sci-fi:

“Perversely, perhaps, though Orbital is a book about space, its blueprint wasn’t 2001 or Dune, but A Month in the Country. I thought to myself: I want to write A Month in the Country in space.” (p. 143)

This seems to have been inspired by online videos of the Earth seen from the ISS:

“There’s never a bad view. You never think: oh, this is the boring bit, more ocean, more desert, blah blah; never, no — every view begs for your fresh attention.” (p. 141).

How brilliant and how true, putting in words what I realise I’ve long felt but never consciously articulated. In fact, how extraordinary to look from an orbiting space station — at an altitude of between 413 and 422 km above mean Earth sea level — yet gaze right into my head and explain to me what it is I can see.

Some other books I've read recently:

Truth & Dare, by So MayerLast Chance to See..., by Douglas Adams and Mark CarwardineChildren of Time, by Adrian TchaikovskyHackenfeller’s Ape, by Brigid BrophyFarewell Crown and Good-bye King, by Margot BennettJanuary 2, 2025

Doctor Who Magazine #612

The new issue of the official Doctor Who Magazine is officially out today (though, via SIDRAT capsule, some subscriber copies arrived last week / last year).

The new issue of the official Doctor Who Magazine is officially out today (though, via SIDRAT capsule, some subscriber copies arrived last week / last year). The cover shows the Second Doctor playing his recorder which also doubled in several stories as a telescope. I mentioned this recently to a mate who thought I must have gone mad but you can see a good example at 13:57 into The War Games in Colour - watch carefully, and you see the Doctor replace the top after use.

This has also prompted me to post my 2019 interview with Frazer Hines about the costumes he wore as Jamie McCrimmon, companion to the Second Doctor.

On pages 36-39 of the new DWM, there's my latest "Script to Screen" feature, this time on Babystation Beta - the space station seen in 2024 episode Space Babies. It's a companion piece to the coverage of that episode I wrote for issue #604 in May. In this case, I spoke to art director Jon Horsham and VFX supervisor Jim Parsons, as well as director Julie Anne Robinson.

Also this issue, my former script editor Jacqueline Rayner says some nice things about my 2011 audio Doctor Who story The Cold Equations. If that's of interest, in 2021, I was a guest on the Gallifrey's Most Wanted podcast talking about this story and the trilogy it was part of.

December 31, 2024

Truth & Dare, by So Mayer

“The funny thing is that getting the morning-after pill the first day of a zombie apocalypse is really no easier or harder than on a previously average day. No bigger a deal, the obstacles are just… different. More slow-moving, brain-eating hordes, sure, but fewer overtly religiose or obstructive pharmacists. The baseball bat I brought to use in case of the former was also effective on the triple-lock cabinets erected by the latter.” (p. 224)

This is a rich, intoxicating anthology of 19 short stories and musings. Several of the stories are set in the near future, such as the one in which the invention of new kinds of artificial dick leads, through one thing and another, to the collapse of capitalism. Other stories spiral backward — to the pogrom in York in 1190, to The Black Cap gay pub, to the narrator’s own history. There are ghost stories and ghostly stories, and a lot of it is strange and unsettling.

The last story, Dune Elegies, is one of several set in a bleak near-future, a world just beyond our current grasp. The narrator, “terfed off” their own radio show, takes up residence in a lighthouse near the stone mirrors at Denge and continues to transmit a podcast, but with a pervasive sense of lost connection. The narrator is unable to recall the names of Conrad Veidt and Derek Jarman while detailing their importance in queer history — we fill in the blanks as readers. Then there’s a response from listeners to the podcast, transmission of which triggers something in stones taken from the area, wherever they might be now. It’s such an odd, beguiling idea, the sort of story that sits with you long afterwards.

As well as what’s happening, there’s the way these stories are told, dense with allusion and word play, poetry and punning. There are references to films and TV shows, novels and academic texts — I’d have quite liked a bibliography and/or end notes for further reading. It’s not just that stuff is referenced; it is toyed with and spun. For example, one passage about the lives of particular pirates includes the phrase “our flag means life” (p. 229) reversing the title of the 2022-23 TV series while at the same time making a connection to its own exploration of sexuality and identity.

We frequently explore derivation and etymology, how meaning is constructed, generating history and identity. With that in mind, I think the cut-up technique of quotations and references may be a way of shaking things up to create new meanings and ideas. That took me back into my own past when, as a university student some three decades ago, I got hooked on linguistic relativity and the so-called “Sapir-Whorf hypothesis” that language shapes or even determines our thoughts and perceptions.

(In fact, it’s an axiom, not a hypothesis, and not one put forward by the linguists Sapir and Whorf as such, who never wrote together. But perhaps that makes it more fitting as a label, evidence that we need a name, any name, to be able to remonstrate with an idea.)

It’s not just about words in the stories here: in dreams of being Joan of Arc and her insistence on wearing trousers, or in detailing why Artemis wore a short skirt, we’re exploring the construction of gendered and non-gendered identities.

By chance, I was reading this as I saw the new documentary From Roger Moore With Love, which details how movie-star “Roger Moore” was an invented persona; Moore learned to play this persona and then, from The Spy Who Loved Me, applied that to his role as James Bond. At one point, Moore’s friend Christopher Walken says this shouldn’t be a surprise because we’re all self-invented people — there’s a point in our lives, perhaps more than one, where we choose who we are. How fascinating to see archive interviews with Moore uncomfortable with the violence and misogyny of Bond or — in an episode of Hardtalk which so yielded something new from its subjects — voicing concern about the “heroic” image of his Bond wielding a gun. I’m not sure I’d have picked up on that if I’d not been reading this book…

Like the world of James Bond, the stories in this book are frequently lusty, even graphic. But Bond is about gratified desire, sex just part of the mix with exotic locations, stylish clothes, fancy food and gadgets. In the book, desire is, I think, less external but bubbling up from within. There’s a lot here on the bloody, visceral heft of bodies — of ourselves not just as contracted identities but as physical things.

“What it means to be in a body, differently, is what the Crusades take aim against,” (p. 61).

So much of this book is exploring that haunting idea, the half of the sentence before “is” and the sentence as a whole.

You can buy Truth & Dare by So Mayer direct from Cipher Press.

December 28, 2024

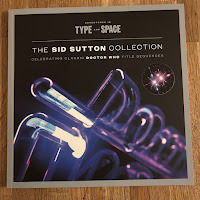

Adventures in Type and Space

My clever colleagues Graham and Jack Kibble-White and Stuart Manning have produced a lovely supplement to last year's Adventures in Type and Space. The new addition is The Sid Sutton Collection, devoted to the late graphic designer perhaps best known for the Doctor Who opening titles used between 1980 and 1986.

My clever colleagues Graham and Jack Kibble-White and Stuart Manning have produced a lovely supplement to last year's Adventures in Type and Space. The new addition is The Sid Sutton Collection, devoted to the late graphic designer perhaps best known for the Doctor Who opening titles used between 1980 and 1986.In February, I posted on Twitter/X some thoughts about Adventures in Type and Space, slightly revised here for clarity:

I’ve been utterly spellbound by this beautiful, brilliant book. It goes in big on a very small subject — the 30 seconds or so of opening titles at the start of each episode of old Doctor Who. But it’s just as thrilling and rich as those sequences, and so much more than simply a history of who made them and how. It’s funny and profound about the process of creating art and what’s going on in the artist’s head. Along the way, we learn the role of God and Fra Angelico in the whizzy opening titles for Sylvester McCoy’s Doctor, and what a CGI artist “sees” in their head as they tap out the code. There are connections to Alien, Bladerunner and Points of View, and everything you could want to know about the typeface Futura. Like the titles themselves, this is an extraordinary visual treat, all the more wondrous the closer you look.

My contribution to that original book was to supply a photograph of Sid Sutton from when I interviewed him at home on 2 May 2017 for Doctor Who Magazine's special The Essential Doctor Who: Adventures in Space. Another of my photographs and some previously unpublished bits of the interview feature in this new supplement.

There is also a long interview with Sid culled from multiple sources, plus an interview with his two sons - who both work in design - and with Sid's collaborator Terry Handley. Again, there's a wealth of detail here: how exactly things were done, using what bespoke equipment and in what premises, and what to look for in the familiar titles that reveal this painstaking process. (Clue: keep you eye on the question marks.)

There's also a revealing interview with Colin Baker as he's shown the myriad different elements Sid employed to create his Doctor Who opening titles. A video of this conversation is also available:

There's some revealing stuff here and not just about the way the titles were made. Baker compares his Doctor, and his plan for revealing this incarnation's true persona, to Mr Darcy in Pride and Prejudice.

"[We] don't want him anywhere near our heroine. But it turns out he's the only truly decent person in the story. Everything he's done, which others have found objectionable, has been for the benefit of third parties, not himself." (p. 37)

There's a sense that these opening titles are invested with great meaning by interviewer Graham Kibble-White, who was 11 when Colin Baker became the Doctor. The conversation is an attempt to explore what meaning they hold for Baker - very different as an actor on the other side of the screen and yet no less significant.

The separate versions of Aventures in Type and Space and The Sid Sutton Collection are now sold out but compendium edition Adventures in Type and Space: The Complete Collection is available to buy from the Ten Acre Films site.

December 23, 2024

Last Chance to See..., by Douglas Adams and Mark Carwardine

With a long old drive in the company of the young Lord of Chaos, I choose an audiobook to match the expected duration (and was only five minutes out) which I thought he'd like - and he did. Last Chance to See is one of my favourite books and it's been fun to pass it on. Mathew Baynton is also a very good choice of reader.

With a long old drive in the company of the young Lord of Chaos, I choose an audiobook to match the expected duration (and was only five minutes out) which I thought he'd like - and he did. Last Chance to See is one of my favourite books and it's been fun to pass it on. Mathew Baynton is also a very good choice of reader.For those who might not know, in 1985, the Observer magazine sent Douglas Adams, best-selling author of The Hitch-Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy, and zoologist Mark Carwardine to Madagascar to look for the endangered aye-aye lemur. Enthralled by this encounter, they followed it up in 1988 with a longer trip looking for a range on endangered species including the northern white rhinoceros and the kakapo. That trip led to a BBC Radio series first broadcast in 1989 and the book published a year later. In 2009, Stephen Fry and Mark Cardwardine made a TV series retracing the original trip.

Fry's introduction to the 2019 edition of the book included things I didn't know, not least that one inspiration for a lengthy trip around the world looking for different endangered species was Adams's tax situation. By spending a year out of the UK, he saved himself a six-figure sum. We learn, too, of Fry's own role in the original endeavour, as house-sitter for Adams and the emergency contact when things went awry.

The main body of the book is a masterpiece, at once killingly funny and shrewdly, beautifully observed. Much of it has long been lodged in my memory; many speak of Adams's ability to correctly predict the future but he's also skilled and sharing ideas and stories in ways that stick. One thing, I think, I'd not picked up on previous readings is how much this is about human foibles and bureaucracy. By detailing all the things that get in the way of Adams and Carwardine getting to see these creatures - of Things Getting Done - these frustrations illuminate the problems faced by conservationists.

Mark Carwardine's last word updates the one in my dog-eared paperback and makes depressing reading: one of the species he and Adams went to see is now officially extinct, another is near as dammit, and the rest all teeter on the verge of extinction, along with countless others. What a world we are passing on to our children.

See also:

Me on the radio version of Last Chance to See...Me on Douglas Adams at the BBC and my reaction to news of his deathDecember 15, 2024

Children of Time, by Adrian Tchaikovsky

“How can we trap them?” (p. 589)

Doctor Avrana Kern begins an ambitious scientific study. From her spaceship the Brin 2, she launches two vessels at a newly terraformed planet — “Kern’s World”, as she sees it. One vessel, the Barrel, contains a population of monkeys. The other, the Flask, contains a nanovirus that will affect the monkeys’ DNA, shaping succeeding generations of their descendants, encouraging the development of intelligence like humanity’s own. The hope is that one day the monkeys will be able to respond to, and converse with, Kern.

Doctor Avrana Kern begins an ambitious scientific study. From her spaceship the Brin 2, she launches two vessels at a newly terraformed planet — “Kern’s World”, as she sees it. One vessel, the Barrel, contains a population of monkeys. The other, the Flask, contains a nanovirus that will affect the monkeys’ DNA, shaping succeeding generations of their descendants, encouraging the development of intelligence like humanity’s own. The hope is that one day the monkeys will be able to respond to, and converse with, Kern. But something goes wrong with the experiment. Instead of monkeys, the nanovirus sets to work on another population on Kern’s World: the spiders. Over thousands of years, alternating been chapters set on the planet and chapters involving the last human survivors of Earth, we follow what happens nexts…

This is an absolutely brilliant book, epic and thrilling and rich. It’s the sort of novel you want to hare through to find out what happens next and yet never want to end. It’s big on ideas and emotion. For all the enormous scale — it sprawls across space as well as time — it is grounded in compelling characters, human and spider. Their respective civilisations are very different from our own, yet we’re drawn in by relatable fears and desires, tensions and challenges.

One clever way in which we are ensnared is that Tchaikovsky retains a number of characters through the enormous span of the novel. Humans are stored cryogenically or by other means (it would be a shame to spoil exactly how), so sleep for thousands of years and then awaken for the next chapter, catching up as we do on what’s changed in the meantime. With the spiders, Tchaikovsky repeats a number of names among different generations, so we follow the adventures of various Portias, Biancas and Fabians, some the descendants of others. In effect, we inherit a connection each time. That in turn matches something the spiders can do in inheriting memories and “understandings”, so it’s a structural device that also helps us understand the psychology of these creatures.

The alien perspective rendered as normal and humanity seen as other is an old trick from science-fiction, one I first encountered in the opening chapter of Malcolm Hulke’s novelisation Doctor Who and the Cave Monsters (1974), which involves a similar clash between human civilisation and a species of intelligent “monsters” with just as much claim to the world. But the span of the novel, that long view of developing society and culture seen through a few long-lived characters so that each challenge is deeply affecting, is reminiscent of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy. In some respects, this is the Mars trilogy with monsters, which I mean as the highest praise.

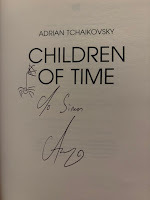

It all builds and builds to a thrilling climax and extremely satisfying conclusion. Really, I’m kicking myself for not getting to this sooner. I bought a copy on 24 August 2016 at the ceremony for the Arthur C Clarke Award for best science-fiction novel of the year, which it won; Adrian was kind enough to sign my copy. On the train home I found the opening chapter a bit dense (I think I was probably the dense one, and also a bit pickled), and the 600-page word count was daunting, deserving or proper attention and time. The result is that this book has sat patiently by my bedside, watching and waiting for me to be smart enough to respond.

It all builds and builds to a thrilling climax and extremely satisfying conclusion. Really, I’m kicking myself for not getting to this sooner. I bought a copy on 24 August 2016 at the ceremony for the Arthur C Clarke Award for best science-fiction novel of the year, which it won; Adrian was kind enough to sign my copy. On the train home I found the opening chapter a bit dense (I think I was probably the dense one, and also a bit pickled), and the 600-page word count was daunting, deserving or proper attention and time. The result is that this book has sat patiently by my bedside, watching and waiting for me to be smart enough to respond.The audio version is expertly narrated by Mel Hudson - who makes the various characters distinct and recognisable. I’m pleased to see she has also narrated the two subsequent novels in the series, Children of Ruin and Children of Memory. I will not leave those so long.

December 13, 2024

Hackenfeller’s Ape, by Brigid Brophy

Professor Clement Darrelhyde spends his days at London Zoo, singing opera by Mozart to one of the enclosures. Despite this encouragement, Percy and Edwina — two specimens of Hackenfeller’s Ape (Anthropopithecus Hirsutus Africanus) — continue not to mate, though she seems more in favour than he does. Then Darrelhyde learns than Percy has been sold to the space programme and will, in just a few days, be blasting off in a rocket on what’s likely to be a one-way trip.

Professor Clement Darrelhyde spends his days at London Zoo, singing opera by Mozart to one of the enclosures. Despite this encouragement, Percy and Edwina — two specimens of Hackenfeller’s Ape (Anthropopithecus Hirsutus Africanus) — continue not to mate, though she seems more in favour than he does. Then Darrelhyde learns than Percy has been sold to the space programme and will, in just a few days, be blasting off in a rocket on what’s likely to be a one-way trip.Darrelhyde attempts to fight the bureaucracy and rouse the interest of the press in his efforts to save Percy. When this fails, he teams up with a young pick-pocket called Gloria to free Percy from his cell…

This short (125 page), funny novel begins with a neat reversal, describing the behaviour of a particular species of ape which, we come to realise within a few sentences is us. I’ve seen this kind of anthropological inversion done elsewhere, such as in David Attenborough’s Life on Earth (1979), where the final, 13th episode looks at human beings from the same objective viewpoint it has applied to other creatures.

This sort of thing is quite common in science-fiction, too; our ordinary, unthinking behaviour suddenly strange. (I’m near the end of Adrian Tchaikovsky’s amazing Children of Time and will have more to say in due course…)

While the conceit only lasts for those first few pages, we frequently see events from Percy’s perspective. The effect of this inversion is, said a review in Time quoted in the front flap, “a pointed and amusing satire”, while the Herald Tribune thought it, “a brilliantly accomplished small book which widens out into large meanings.”

The lightness of touch surprised me given what I know about Brophy’s later campaigning on the issue of animal rights. Her name came up when I was looking into issues of personhood and reading around the documentary Project Nim, which I reviewed for the Lancet.

The novel was apparently inspired by Brophy’s time living close enough to London Zoo to hear the cries of captive animals. She later wrote a piece, “The Rights of Animals” (1965) for the Sunday Times, subsequently republished by the Animal Defence and Anti-Vivisection Society, and contributed to such publications as Animal, Men and Morals (1971) and Animal Rights: A Symposium (1979).

I’m also aware of Brophy’s effective campaigning in other areas. With Maureen Duffy she was instrumental in seeing the Public Lending Right enshrined in law, so that authors receive payment for their books being borrowed from public libraries. I’m a direct beneficiary, a fact I have to declare at each meeting of the British Library’s advisory committee to PLR. As I linger over the complimentary sandwiches, I think of Brophy and Duffy and all they achieved.

Yet this novel is not a polemic or even particularly campaigning; indeed, an anti-vivisectionist is one of the targets for satire here. Colonel Hunter of the League for the Prevention of Unkind Practices to Animals is more keen to collect and share photos of animals in distress than to stop such things actually happening. There are no goodies or baddies, just a lot of different frail and fallible people with their foibles.

Elsewhere, a newspaper won’t get involved because they’ve already decided to support the nascent space programme and run a “Space corner” each Saturday. This, we’re told is,

“For the kids. It does them less harm than sadistic comics.” (p. 43)

That’s a sign of the time in which this was written; the anxiety about American comics warping impressionable minds led to the creation of the far more wholesome, home-grown Eagle, launched in 1950. This novel is a counterpoint to the optimistic future lavishly displayed each week in the Eagle’s cover strip Dan Dare. The idea that the space programme could conscript an ape from the zoo is perhaps informed by the shadow of war. The professor’s boarding house and the niceties of dinner with his sister all seem from another age.

It’s been interesting to read this, by chance, after another novel from the same year. It is very different to Farewell Crown and Good-bye King, more in tune, I think, with something else from 1953: Nigel Kneale’s TV serial The Quatermass Experiment has a similar ambivalence to the space programme and the costs involved. But what really struck me about this novel was how modern it feels. I can see why it still felt relevant enough in 1979 to be republished in hardback — the edition I read.

One reason for that is the treatment of impulse and desire, whether ape or human, unworried by social convention. At one point, Gloria daydreams of an encounter with an imagined, handsome young man, who she tellingly gives the name of the aged professor. When, in reality, a young man then asks her out, the relationship lasts only briefly.

“I wasn’t flash enough for her,” (p. 124).

Percy being at liberty transforms his sex drive but his freedom is short-lived. Kendrick, the young man from the space programme, has to hastily improvise an alternative to using Percy that further blurs the distinction between primitive ape and sophisticated human. There’s something both comic and disturbing in all this. When Percy returns to his enclosure of his own volition, Gloria asks what he’s up to.

“Darrelhyde repressed the first word that came to mind. ‘Mating,’ he answered.

“Oh.” Perhaps with cold, Gloria shuddered, and then giggled slightly. “Aren’t animals awful?” (p. 92)

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers