Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 2

September 7, 2025

Who and Me, by Barry Letts

“Terrance once laughed at me when I told him that a fly was his cousin.” p. 74

I said in my post on Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons that I could see, in the sometimes sparky but close friendship between the Third Doctor and Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart, something of Doctor Who producer Barry Letts and script editor Terrance Dicks. Reading Letts’s memoir of his first two years in that role has only bolstered that view.

It’s an engaging, insightful book, which ends with Letts about to tell us about the origins of Day of the Daleks (1972), promising a story involving him and Terrance drinking champagne at Pinewood Studios with Terry Nation. This is just after Letts has also told us that Terrance’s own memories of what happened are very different from his own. How intriguing!

Sadly, the promised second volume of memoir never materialised and the first volume was published after Letts’ death in 2009. This expanded edition published in 2021 includes a good overview of Letts’ career by Michael Seely and a long interview with Letts conducted in 2008, which help to fill in some of the gaps. Also, Letts skips about a bit in his recollections, so the main body of the book includes some insights into his work on the BBC Classic Serials years after his time on Doctor Who. Even so, there’s a feeling of a story only partially told.

Really, I wish this were an autobiography — covering Letts’ whole life — rather than a memoir of one particular job. I’d have loved much more in this evocative vein:

“I was born less than seven years after the end of the First World War. I can remember, as a small boy, the lamplighter with his long pole, coming up the road in the evening to turn on the gas in the street lamps; I can remember feeding lumps of sugar to Jones, the horse who pulled the baker’s delivery van; I can remember Mr Glover, the milkman, pushing his little cart with its giant wheels at the back, dipping his ladle into the great milk churn suspended between them to fill the can which he brought to our back door, to ladle a pint or two into our jug…” (p. 152)

That golden age when tuberculosis was delivered to your front door!

Yes, this stuff isn’t directly related to Doctor Who but often it can inform what a person brought to the programme. For example, in an interview for the BBC’s Doctor Who website in 2004, Letts shared some other details of his early life, such as his childhood favourites:

“Books? Wind in the Willows; Professor Branestawm; the Just William books; the Arthur Ransome books; every sci-fi book I could lay my hands on. Films? All the Fred Astaires; Snow White and Pinocchio; The Wizard of Oz; Things to Come.”

The Wizard of Oz was a sizeable influence on the plot of The Three Doctors (1972-3), and Letts later adapted Pinocchio for the BBC. We can also see in these different books and films a mix of fantasy and adventure with a strong moral core, the bedrock of his Doctor Who.

There are lots of Who-related tidbits in the memoir I didn’t know. In the interview from 2008, Letts says that,

“The Mutants, for example, was basically my idea. That wasn’t all that clever actually, because I had pinched it from a book by Olaf Stapledon.” (p. 197)

My guess is that he was referring to First and Last Men (1930) or its sequel Star Maker (1937), which chart the history of humanity over billions of years, including evolution into other forms.

Letts tells us twice about acting with Roger Delgado on Queen’s Champion (1958), which included Delgado killing him in a sword fight. I wonder if that inspired the Doctor and Master’s sword fight in The Sea Devils.

He tells us about “kenshō”, a Buddhist term meaning “seeing” or “perceiving”, saying that he worked this concept into his 1974 novelisation Doctor Who and the Daemons, where he has the Doctor — facing monsters, the end of the world etc — taking a moment to enjoy a bright blue sky. (p. 167 of the memoir, p. 96 of the novelisation).

This is, of course, very similar to the “daisiest daisy” speech made by the Doctor in TV story The Time Monster, co-written by Letts. There’s a common perception among fans that such “moments of charm” were put in at the request of Jon Pertwee* but the one in The Time Monster is, given what he says here about kenshō, clearly Letts putting his own philosophy into the series.

(On the documentary Genesis of a Classic, about the making of 1975 TV story Genesis of the Daleks, Terrance recalls something he was told by his successor as script editor, Robert Holmes, about being approached by Pertwee: “Now, listen, Bob, you know what I like … just want a few moments of charm, you know.” I wonder when that conversation took place; the obvious moment is when Holmes started working as script editor, shadowing Terrance on Death to the Daleks in 1973.)

There’s some good detail on Snowy Black, the 13-part serial Letts devised as a potential replacement for Doctor Who if it were cancelled in 1970. The original plan, he says on p. 82, was to finish recording Inferno, the last of that year’s Doctor Who, on 29 May and “plunge straight into rehearsals for the OB shoot” on the new serial.

He says Snowy Black was itself cancelled “in April, because of the great success of the new Who” (p. 83). Indeed, on 11 April, Episode 4 of The Ambassadors of Death was seen by an extraordinary 9.3 million viewers. This, says Letts, was a relief, because he’d not started on the first script of his new serial beyond a sample scene used in casting lead actor Mark Edwards.

“I had no time to write during the day. I was far too busy with the current productions; planning the next season with Terrance; setting up the team that would be working on Snowy Black with me and so on” (p. 83)

Then something happened that surely clinched the decision. On 27 April, director Douglas Camfield collapsed due to a hitherto unknown heart condition and Letts had to take over as director of Inferno. And that surely meant he had no time to complete his script and couldn’t be expected to go straight into production on this ambitious new project anyway.

There are some details Letts seems to have muddled up. For example, he tells us on p. 41 that in 1965 he had lunch with Hugh David to seek his advice about becoming a director. David was, says Letts,“in the midst of editing” Doctor Who story The Highlanders, but the first episode was actually recorded in studio on 3 December 1966. That was after Letts — finally, after some persistence over a year — started the BBC directors’ course on 29 November 1966 (p. 46).

So there are some things I need to fact check and follow up on for my forthcoming biography of Terrance Dicks. I’d especially like to know more about Jon Pertwee and Patrick Troughton,

“appearing together at an American convention — in a playlet written by Terrance overnight in his hotel bedroom — which capitalised on their supposed antagonism, enjoying it so much that they insisted on two repeat performances” (pp. 18-19)

The Broadwcast list of Doctor Who conventions in the United States offers only one occasion where Terrance, Troughton and Pertwee were all at the same event: the TARDIS 21 (Spirit of Light) convention in Chicago, 23-25 November 1984. Were any of my readers there?

September 4, 2025

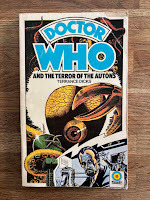

Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons by Terrance Dicks

An unexpected delight of blogging my notes on these early Target novelisations is that people have been in touch to say that a particular book was a favourite, to share a vivid memory of where they first acquired it, or to tell me how much these books meant to them generally. I’ve been toiling to make sense of what these books are as things but have been getting a sense, from other people, of what they mean.

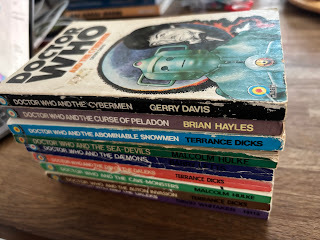

An unexpected delight of blogging my notes on these early Target novelisations is that people have been in touch to say that a particular book was a favourite, to share a vivid memory of where they first acquired it, or to tell me how much these books meant to them generally. I’ve been toiling to make sense of what these books are as things but have been getting a sense, from other people, of what they mean.I’m also grateful to those who’ve suggested further connections, with ideas feeding from the books into the TV series and vice versa. Nicholas Pegg points out that the term “Cyber Leader” is first used in the novelisation Doctor Who and the Cybermen and the TV story Revenge of the Cybermen, both written by Gerry Davis and probably commissioned around the same time. Michael Seely, meanwhile, prompted me to look for the use of “chameleon circuit” in Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons years before it was said on TV.

I think this term originated in Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon by Malcolm Hulke, first published on 18 March 1974. By chance, I bought a first edition on Saturday at the Whooverville convention — near mint for £8, bargain!

That book begins with two Time Lords, one the venerable Keeper of the Time Lords’ Files who is over 2,000 years-old, and the other his successor, “a mere 573 years of age”. They discuss the limitations of the first ever TARDIS which could carry three people, four at a squeeze (suggesting it was not bigger on the inside), and the two serious defects of the Doctor’s TARDIS. One issue is that the Doctor can’t direct where it takes him.

“‘The other defect,’ said the old Keeper, was that that particular TARDIS had lost its chameleon-like quality. It was in for repairs, you see—that’s how the Doctor got his hands on it.’” (Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon by Malcolm Hulke, p. 8.)

“Chameleon-like” means nothing to the extraterrestrial young Time Lord, so the old Keeper explains to him (and younger readers) on p. 9 that a chameleon is a creature on Earth that can change the colour of it skin; a working TARDIS can change its “colour, shape, everything”.

There is, as far as I can tell, no precedent for this. The Making of Doctor Who (1972) by Hulke and Dicks does not mention chameleon-like abilities, beyond mentioning Chameleons — the shape-changing villains of Hulke’s first TV Doctor Who story. Did his choice of analogy in the novelisation come from them?

Whatever the case, this innocuous moment in Hulke’s novelisation— perhaps not the most exciting opening ever — has gone on to become Doctor Who lore. This, I think, is where the idea is first introduced that the Doctor stole the TARDIS from his own people while it was in for repair. (Do please write in if I’m wrong!)

Here, it is in for repair because of the fault in the chameleonic function. But when Doctor Who began on TV, that system worked, with the TARDIS disguised as a police box to blend in with London of the early 1960s. It was only in the second episode, when the TARDIS materialises somewhere else, that the Doctor and Susan express concern that it has not changed to blend in with its new surroundings. The implication is that the system breaks as a result of the unusual take-off at the end of the first episode.

In The Name of the Doctor (2013), we see a cylindrical TARDIS in the repair shop on the Time Lords’ home planet Gallifrey as the Doctor steals it, the implication here that it’s in for repair for some other technical fault, prior to it taking the guise of a police box. But Fugitive of the Judoon (2020) introduces the idea that the TARDIS has been a police box before this. So maybe the old Keeper in Hulke’s novelisation is right after all — and the cylindrical TARDIS is only a temporary fix of the chameleonic system, like the ones seen in Attack of the Cybermen (1985).

Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons is, as I explained at Target Books Club, the fourth of 236 books written by Terrance Dicks, but the fifth to be published. He started writing it on 2 May 1974, less than two months after publication of Hulke’s Doomsday Weapon. And Terrance seems to have read that book:

“The Doctor knew that the Master’s TARDIS, unlike his own, still had its chameleon mechanism in working order. … This gave it the ability to change appearance, so that wherever it landed it could blend into the landscape. The Doctor’s TARDIS had once had this power but, unfortunately, on one of his visits to twentieth century London, the chameleon circuits had worn out, and he had been unable to replace them.” (Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons by Terrance Dicks, p. 61.)

That is taking its cue from Hulke, isn’t it?

Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon was the first novelisation to feature companion Jo Grant, and Hulke made it her debut story — in the book, she’s been at UNIT for a week and has never heard of the Master. But on TV she’d already had several adventures by this point, all of them battling the Master. Terror of the Autons was her first TV story and in novelising it Terrance makes no attempt to rationalise the account in Hulke’s novelisation; he simply introduces Jo again, as it happened on screen (but, I think, makes the Doctor more charming).

If, as I suspect, Terrance had read Doomsday Weapon and borrowed the chameleon-like analogy, then this is a conscious choice: to make his book(s) a faithful record of the TV episodes and not concern himself about what other authors might have done in their own books.

Note that Terrance refers to “chameleon circuits” plural and not a proper noun. It’s only later that it becomes “chameleon circuit” singular: the proper name for a specific bit of technology. On TV, that’s first used in Part One of Logopolis (it’s the first thing the Doctor says in that episode).

Note also that Terrance corrects the record from what’s said in Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon: he says, as per the first two TV episodes of Doctor Who ever, that this chameleonic function broke down on a visit to late 20th century London, i.e. after the Doctor stole the TARDIS from his own people. (Terrance makes no mention of it having been in for repair.)

How familiar was Terrance with the first episodes of Doctor Who? In the TV version of Terror of the Autons, written by Robert Holmes, the Doctor is apprehended at the door of the Master’s TARDIS listening for “certain vibrations”. Perhaps extrapolated from that, in the novelisation Terrance describes, twice, a characteristic quality of the Master’s chameleon-like disguised ship.

“The horse-box tingled” (p. 8)

“He placed his hand flat against the glossy side [of the horse-box] and felt the tingling vibration” (p. 62).

But this is very like a moment in the first TV episode, where school teacher Ian Chesterton is astonished when he touches what looks like an ordinary police box. There’s a faint vibration. “It’s alive!” he says.

That doesn’t happen in the novelisation Doctor Who and the Daleks, which also introduced Ian and Barbara to the TARDIS. If this and the correction about the faulty chameleon circuits are drawn from the first two TV episodes, when had Terrance seem them? The first episode was broadcast on 23 November 1963 and then repeated the following week but was not shown again on TV until well after Terrance wrote this book. It must have made quite the impression for him to recall such specific details more than a decade later.

Another option is that he watched the first story again while at the BBC, at some specially arranged screening. Maybe, conceivably, he did so in preparation for The Three Doctors (1972-3). But my sense from interviews with him is that he did not know the first story very well, and rather dismissed it, until tasked with novelising it in 1981.

The other option is that a fan responded to Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon with an, “I think you’ll find...” I’ve seen later examples of that in Terrance’s surviving correspondence.

Until The Three Doctors, the Doctor's laboratory at UNIT looked very different in each story in which it appeared. The version seen in The Three Doctors appears again in Planet of the Spiders (1974) and Robot (1974-75). I think the descriptions of the Doctor’s lab in the novelisations Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks and Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons match that version. Indeed, UNIT HQ in the TV Terror of the Autons is in central London, apparently right by the Thames into which the Doctor hurls the Master’s bomb. In the novelisation, to make the disparate locations all one place, Terrance invents a “little canal”, presumably running through the grounds of the estate seen in The Three Doctors.

There are other fun bits of retroactive continuity. On p. 67, the Master has a “Sontaran fragmentation grenade”, suggesting he’s met the war-like species introduced two stories after the Master’s final on-screen appearance at the time Terrance wrote this. The Doctor also uses the phrase “reverse the polarity” here, four stories earlier than its first on-screen use in The Daemons.

There are some neat fixes to elements of the TV story, such as setting up why the Master would switch sides at the end (here, before the switch, he bickers a few times with an Auton). On p. 15 we hear how a Nestene sphere survived when the Autons were otherwise all destroyed at the end of Spearhead from Space. On p. 114, there’s a chance for Jo to demonstrate her army training when she knows how to fall safely, rolling, bending her legs and protecting her face with her arms. There’s something similar, I think, in Doctor Who and the Giant Robot, when Sarah Jane Smith handles a gun.

We can even deduce that Terrance made these fixes as he went along. For example, on p. 96 he has the Master heading back to his own TARDIS meaning to confound the Doctor. However, when the Master then shows up in the Doctor’s laboratory, we’re told he entered by foot — hypnotising UNIT sentries to think they’ve seen and ushered in the Prime Minister (p. 105). Terrance had clearly realised that the Master couldn’t use his TARDIS to sneak into UNIT HQ because the Doctor had already stolen his dematerialisation circuit (singular, proper noun). Terrance seems to have spotted that error between writing pages 96 and 105. According to his diary, that was on Wednesday 15 May 1974.

There’s some fun word play, too, adding to the dry humour of the TV version. The Master makes a joke, describing the deadly plastic chair as made from “polynestene” (p. 46). The Master’s real name, we are told, is “a string of mellifluous syllables” (p. 25) — a lovely word, meaning to flow like honey. There’s another deftly employed word later, meaning circus workers: “roustabouts” (p. 70).

This may seem a simple, prosaic version of the TV scripts — like Terrance's last one, Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen. In fact, it’s full of deft structural work and detail. It is, I think, a very good novelisation of a very good set of scripts, though I may well be biased because this novelisation was such a favourite of my childhood.

Reading it again, in the context of other novelisations and all I’ve learned about Terrance in recent months, I think my favourite moment is a bit from the Brigadier’s perspective.

“The Doctor and the Brigadier were engaged in one of their not infrequent arguments. Good friends though they were, their temperaments were so utterly different that the occasional clash was inevitable. This time the subject of dispute was the missing Nestene energy unit. The Brigadier, aware that he should never have allowed it to go to the museum, knew that he was really in the wrong. As a result he was naturally insisting that he was completely in the right” (pp. 20-21).

The Third Doctor and Brigadier were like Holmes and Watson, Terrance told me, explaining why he and Barry Letts then created a Moriarty for them in the form of the Master. But this moment in the novelisation isn’t Holmes and Watson at all. I suspect it might be more Barry and Terrance.

August 29, 2025

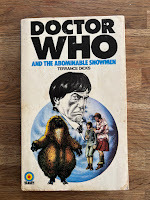

Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen, by Terrance Dicks

What follows is dedicated to the memory of my friend John J Johnston who died yesterday morning. The EES has an obituary. You can also see John in typically erudite form giving a talk on Sutekh’s sex life. A man with such an enormous heart that Anubis will need bigger scales. RIP.

The third of the 236 books written by Terrance Dicks was published on 21 November 1974. It was the first of Target’s Doctor Who novelisations to star the Second Doctor, though he’d appeared briefly in both Terrance’s previous novels (in the prologue of

Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion

and in the Mind Analysis Machine sequence in

Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks

).

The third of the 236 books written by Terrance Dicks was published on 21 November 1974. It was the first of Target’s Doctor Who novelisations to star the Second Doctor, though he’d appeared briefly in both Terrance’s previous novels (in the prologue of

Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion

and in the Mind Analysis Machine sequence in

Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks

).This wasn’t planned to be the Second Doctor’s debut in the range. My first edition of Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks, published on 18 March 1974, lists the books “in preparation” in this order:

Doctor Who and the DæmonsDoctor Who and the Sea-MonstersDoctor Who and the CybermenDoctor Who and the YetiThe first two of those (each starring the Third Doctor) were published on 17 October that year, though by then the second of them had been retitled Doctor Who and the Sea-Devils. According to this list, the Second Doctor was then due to make his debut pitted against the Cybermen, to be written by Gerry Davis and presumably published in time for Christmas. However, things got delayed; it’s probably no coincide that, on 9 May 1974, Davis was also commissioned to write a new Cyberman story for the TV series, which he may have given priority.

Terrance’s Yeti book must have been delivered in good time and required little editorial work if it could be brought forward in the schedule. By the time of publication, the title had changed to Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen to match the original broadcast.

Earlier this year, I looked through two separate appointments diaries Terrance had for 1974. One he used (sporadically) to list appointments. On Tuesday, 30 April 1974 he had a 10.30 meeting at 93 Piccadilly — a branch of Natwest bank, presumably to discuss his new status as a freelancer. He was then due to meet, presumably for lunch, Mike Glover, the new editor at Target.

The following day, Terrance attended the final studio recording on Planet of the Spiders, his last Doctor Who story as script editor. The day after, 2 May, according to his other diary, he started writing his fourth novelisation, Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons (which, as I’ve explained previously, was his fifth to be published).

So his first three novelisations were all written while he was on-staff at the BBC, QED.

The decision to novelise the first Yeti story is interesting, given that the Yeti had not appeared on screen since a brief cameo at the end of The War Games in the summer of 1969 and there were no plans to bring them back to the series. They’d certainly made a lasting impact: during production of the Doctor Who TV movie in 1996, Paul McGann was asked his memories of the series and recounted, vividly, details of the Yeti control-spheres.

As I’ve argued before, editor Richard Henwood was also very monster-focused. Books about Daleks, Cybermen and Silurians/Sea Devils had all been commissioned by Target, and the Ice Warriors would soon feature in Doctor Who and the Curse of Peladon, published on 16 January 1975. The Yeti were the only other monster to star in more than one TV story up to this point.

Another possibility is that this particular Yeti story resonated with Terrance, who must have been working on the novelisation at the same time as script editing TV story Planet of the Spiders which is also about Tibetan monks and nefarious psychic powers. An element of that TV story ends up in this book, with the Doctor teaching companion Victoria to resist hypnosis by reciting the “jewel in the lotus prayer”: “Om, mane, padme, hum” (pp. 127-128).

That TV story was, of course, inspired by and an expression of the Buddhist faith of co-writer, director and producer Barry Letts. He was surely the source of the details about life in a Tibetan monastery in Terrance’s novelisation of The Abominable Snowmen which don’t feature in the TV version.

The monks, for example, wear “saffron-coloured robes” (p. 26) a detail that could not be conveyed in the black-and-white TV episodes. We also learn that these monks drink “unsweetened tea with Yak butter floating in it” (p. 49). When the villains are defeated and life returns to normal, the monks’ rituals include “banging an enormous gong” (p. 138). None of that is from the TV scripts; it must have come from Terrance’s friend and colleague.

I don’t think Terrance can have seen the sole surviving episode of the TV story before he wrote the book. Had he done so, he would surely have tried to convey something of the scale and ambition of the location filming, with Snowdonia doubling for Tibet. His descriptions are serviceable but curt. He also describes the Yeti control-spheres as the size of a “large pebble” (p. 70), fitting easily into a pocket. On screen, they had to be football-sized to accommodate motors.

We get our first description in a Target book by Terrance of the interior of the TARDIS, which has a “centre console” rather than “central” (p. 10). On the same page, the Second Doctor has a “shock of untidy black hair”, the “shock” borrowed from the description of the Third Doctor in Terrance’s previous book. He describes companions Jamie and Zoe pithily, and provides potted histories - I assume working from either the in-universe history of the whole series in The Making of Doctor Who (1972) or the story-by-story summaries in the Doctor Who 10th anniversary special published in 1973 by Radio Times.

Though Terrance is credited as co-author of The Making of Doctor Who, my suspicion is that he was more of a consultant on the first edition than a writer. The recent biography of Malcolm Hulke also reveals that the in-universe history of the series given in that book was compiled by Hulke’s assistant and sometime girlfriend Lauraine Palmeri (Herbert, p. 46). So Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen is the first example of Terrance acting as not just the script editor of the current TV show but a historian of the whole series.

There’s one further historic first here. Terrance generally writes in an engaging plain style, the descriptions concise and straightforward. This novelisation is, I think, even more straightforward than Terrance’s previous ones. In those, he reworked some events and structure of the TV stories they were based on; here each episode is relayed breezily in two chapters each. There’s a sense of bosh, job done.

But on p. 106, the Doctor produces a piece of chalk from his “capacious” pockets. It’s a word Terrance will often use again in these novelisations, along with other occasional archaic, vivid gems: “roustabout”, “mountebank” and “jollop” feature in his next two novelisations. Each time, they make perfect sense in context so readers learn this new vocabulary. They are little bombs of knowledge.

Capacious is particularly effective. It’s a Dickensian word: for example, Old Fezziwig in A Christmas Carol (1843) wears a “capacious waistcoat”. The Second Doctor’s frock coat doesn’t just have big pockets; that perfectly chosen adjective makes them, vividly, something a bit magical and from another time.

August 25, 2025

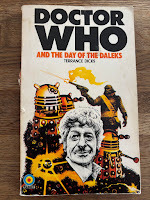

Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks by Terrance Dicks

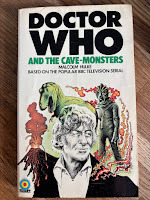

Just sixty days after the publication of novelisations of the Third Doctor’s first two screen adventures — Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion by Terrance Dicks and Doctor Who and the Cave-Monsters by Malcolm Hulke — there was more. On 18 March 1974, Target Books presented two further Third Doctor books by the same pair of authors, skipping ahead to adventures that each star a major baddie.

Just sixty days after the publication of novelisations of the Third Doctor’s first two screen adventures — Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion by Terrance Dicks and Doctor Who and the Cave-Monsters by Malcolm Hulke — there was more. On 18 March 1974, Target Books presented two further Third Doctor books by the same pair of authors, skipping ahead to adventures that each star a major baddie.Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon, by Hulke, features the villainous Master and also introduces us to companion Jo Grant (even though this was not her debut story on TV). Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks, by Dicks, pits Jo and the Doctor against — well, guess.

I think you can see that these follow-up novelisations were written pretty quickly. The phrase, “You’re right, of course,” is used two-thirds of the way down page 11 of Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks and then again at the top of page 12, which is just the sort of thing a copy editor ought to catch if missed by the author.

Later, we’re told three times within about a page of text (pp. 101-102) that the futuristic trikes are specially designed to race across a landscape strewn with rubble — for all that this is a neat explanation of why there happens to be a trike conveniently parked out in the wilderness. When the Doctor sees this vehicle,

“He jumped into the driver’s seat” (p. 102).

On to, surely, when it’s a trike. Or there’s the awkward alliteration and repeated “recent” here:

“I have been studying the recent reports of resistance activity. It has reached a peak in recent weeks.” (p. 14)

That’s a shame because Terrance, who spent five years in advertising before his time on Doctor Who, had a particular gift for the pithy, vivid phrase. There are plenty of those here, too. The Controller of Earth Sector One sums up the Third Doctor as the,

“tall lean man with the shock of white hair” (p. 99).

Or there’s the poetic moment in describing,

“the Time Vortex, that mysterious void where Time and Space are one” (p. 39).

Generally, this is a cracking prose version of a cracking TV story in which gorillas (p. 9) battle guerrillas (p. 17) at the behest of the Doctor’s arch-enemies. While the Daleks, on screen, don’t appear until the closing seconds of Episode One — that is, a quarter of the way into the story — Terrance brings them in after just seven pages, and there’s a big illustration, too. The book promises and delivers.

It also includes the ending excised from the TV version, in which the Doctor and Jo appear to their earlier selves, the first half of which otherwise doesn’t make much sense. The trike sequence is a great deal more thrilling than on screen, with Ogrons pursuing on their own trikes and the Doctor driving up the side of a house and doing cool skids and jumps, in the way you imagine a chase when you’re a child.

I’m amused by 22nd-century guerrilla Anat not having seen a telephone before but knowing how it works (p. 63) — I’m not sure my own children would — and Boaz having read “history books” (p. 73) so that he knows all about servants. The mechanics of future, Dalek-conquered Earth also include gruel for most humans but “real wine in a real china cup” for the Controller (p. 12). Who grows the grapes and presses wine in the Dalek Empire? Who makes fancy cups? (I have wanged on before about the economics of the Daleks.)

Other added details include the mechanics of changing future history. At the end of the novelisation, the Doctor explains that,

“I was able to intervene and put history back on its proper tracks.”

And Jo responds:

“I know … because you’re a Time Lord.” (p.138)

That, I think, is tying this up with what happens at the end of the TV story Invasion of the Dinosaurs, which had just finished broadcast when this book came out.

Then there’s the way this novelisation ties in with one of Terrance’s later TV stories. We’re told that the Daleks’ Mind Analysis Machine — with capitals — has previously left its human subjects,

“shambling idiots with all their intelligence drained from them” (p. 100).

The Doctor is badly hurt by his experience, though recovers after,

“a little food and wine, and a chance to rest” (p. 109).

Terrance’s next book, Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen, also has stuff about the dangers of tampering with people’s minds, all almost a decade before his TV story The Five Doctors features the dreaded Mind Probe. The implication is that Terrance — who helped created the evil, hypnotic Master — found mind control rather disturbing.

I think this novelisation also helps reveal something that Terrance really liked about the Master’s debut TV story. In Episode Three of Terror of the Autons (up on iPlayer), Captain Yates bravely commandeers’ the Brigadier’s Austin Maxi and drives it straight into an Auton. The creature goes flying, somersaulting down a hill — and then, all in the same shot, gets back up and starts climbing.

It’s a brilliant stunt and Terrance has something like it happen in three of his first four books: on p. 139 of Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion, again on p. 77 of Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks (in this case, the Brigadier driving into an Ogron) and then on p. 75 of the fourth book he wrote, Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons.

In each case, the vehicle being driven is referred to as a “jeep”. The word “jeep” is used a lot in TV Doctor Who overseen by Terrance as script editor, from Episode 7 of The Invasion (1968) — the first story on which he received a screen credit — to Part Four of Invasion of the Dinosaurs (1974); Terrance’s successor, Robert Holmes, began shadowing him from the next story.

(“Jeep” is also used in Part Four of The Curse of Fenric (1989) and in Doomsday (2006); I wonder if there’s a correlation between script editors / show runners who don’t drive, just as Terrance didn’t.)

Of course, what’s seen on screen in these stories and what would be used by the British Army or its UNIT spin-off is not the distinctive US Army general purpose vehicle but instead the British Land-Rover, inspired by the American jeep but a notably different car. Someone must have pointed this out to Terrance or the Target editorial team at some point between the manuscript of Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons being delivered around the end of May 1974 and then typeset, and the publication of the next book Terrance wrote, Doctor Who and the Giant Robot, published the following March.

In the latter, the “Brigadier’s Land-Rover” first appears on p. 24 and then throughout. But it is “jeep” throughout the novelisation of Terror of the Autons. Terrance surely didn’t correct the error in one book and then return to the wrong name in his next, so this misidentification of the Brigadier’s make of car is further evidence to support my wheeze that Terrance wrote the novelisation of Terror first and then wrote Giant Robot, though they were published the other way round.

More of this stuff to come as I write up my forthcoming biography of Terrance Dicks, due for publication some time next year. In the meantime, you might like my biography of David Whitaker, the author of the very first Doctor Who novelisation.

August 24, 2025

Bookish, by Matthew Sweet

This is a novelisation of the first series of the TV drama of the same name, created by Mark Gatiss and co-written by Matthew Sweet (both of whom I know). The titular Gabriel Book runs a bookshop, Book's, at 158 Archangel Lane, WC2, his wife Trottie running a wallpaper shop next door. Book has an encyclopaedic memory of the thing he's read and a great interest in the strange and macabre, consulting for the police when they have unusual cases. He also seems to have done some kind of intelligence work in the war and has his own secrets...

This is a novelisation of the first series of the TV drama of the same name, created by Mark Gatiss and co-written by Matthew Sweet (both of whom I know). The titular Gabriel Book runs a bookshop, Book's, at 158 Archangel Lane, WC2, his wife Trottie running a wallpaper shop next door. Book has an encyclopaedic memory of the thing he's read and a great interest in the strange and macabre, consulting for the police when they have unusual cases. He also seems to have done some kind of intelligence work in the war and has his own secrets...Sometime around February 1946, a young man called Jack Blunt is released from prison and finds himself offered a job assisting Book. Jack's an orphan, left with only a photograph of his father and not even his name. Soon he's caught up in the Books' lives and their investigations of murder.

The novelisation largely follows the events of the three two-part TV stories but its peppered with additional details. For example, it is bookended by letters from 1962, 14 years after the events seen on screen and giving some hints about what is still to come. We also glimpse a bit more of Trottie in the war and Book takes a haunting journey on a train.

When books are mentioned, we often learn their publisher and bindings - and so gain something of the way Book classifies his world. We're told the second adventure takes place in August 1946 six months after the first (p. 129), and that the third story occurs "weeks" later, so in September.

It's also peppered with bits of real history, such as the other roles taken by film extras Linda and Barbara:

"The David Lean Great Expectations condemns them to the cutting-room floor." (p. 160)

As with the TV series, it's all good fun but the cosy crimes are given an edge by the real social history. In that sense, it's got something, I think, of the feel of Call the Midwife: just the thing for a Sunday evening in front of the box. A second series is now in production and I hope it can be seen more widely than on the relatively limited channel U&Alibi because it is a delight.

See also:

Me on The New Forest Murders, by Matthew SweetAugust 23, 2025

Writers' Guild guide to working with factual material

The Writers' Guild of Great Britain has produced a new, free guide to working with factual material.

The Writers' Guild of Great Britain has produced a new, free guide to working with factual material. I've been involved in helping put it together, in my role as chair of the guild's Books Committee. Earlier this week, I was quoted by trade paper the Bookseller in its coverage of the free guide. Later this week, on 27 August, I'll be hosting a free online event about it later this week (see below for details).

It's likely to be my last job as chair, as my three-year stint comes to an end next month at the guild's AGM.

Full blurb for the guide and event details as follows:

The lives of real people and true stories have always provided inspiration for writers. But the practicalities of working with factual material – and the potential to upset an existing person (or their lawyer) – can leave writers feeling anxious.

Which is why WGGB has today (19 August 2025) launched a new free, online guide on working with factual material.

The guidelines cover how copyright law treats factual material and how writers can build relationships with their subjects. They also provide advice on how to avoid being accused of libel or defamation.

The guidelines have been produced by the WGGB Books Committee, but the advice and principles contained in them will also be useful for writers working in other craft areas such as film, TV, theatre or audio.

The guide includes answers to questions that the WGGB is regularly asked. For example:

Do I need ‘life rights’ to write about a real, living person?What if I want to write about a real, deceased person?Do I need permission to include a reference to a brand or trademark in my work?Do I need a licence to quote an academic or journalistic article in my work?Do I need a licence to parody or pastiche something factual in my work?What if my sources are in the public domain?How do I protect my copyright when doing research/conducting interviews?Should my interview subjects sign an NDA?How do I work with historical consultants?What if my subject wants a cut of the profits from my project?I want to base a fictional character on a real person – can I do that?When it comes to undertaking research and interviews, for example of subjects or specialists in the author’s chosen area, we have published an accompanying template ‘Right to release’ form (as a free download) which the writer can ask the interview subject to sign to confirm that they understand the purpose of the interview and which grants the writer the right to use their material.

Working with factual material guides writers through understanding the differences between libel and defamation, best practice to protect themselves against a legal case, and the implications of writer warranties and indemnities.

WGGB Books Chair Simon Guerrier said: “When it comes to working with factual material, there are clearly many areas in which writers want help and clarification — as WGGB has received numerous enquiries in the past few years.

“This clear, concise publication guides writers through what they need to know and includes some practical tips.

“I’m very grateful to everyone on the WGGB Books Committee and at the union for their hard work in putting these guidelines together.”

Working with factual material – come to our free event on 27 August

WGGB Books Chair Simon Guerrier will be offering some practical advice on this subject and discussing with guests (to be announced) the pitfalls of writing about real-life characters, events and issues, whether contemporary or historical.

Live captions will be available throughout. Please let us know when you register if you have any additional access needs.

5-6pm, 27 August

Online, via Zoom

Price: free

August 17, 2025

Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion by Terrance Dicks

“In this, the first adventure of his third ‘incarnation’, DOCTOR WHO, Liz Shaw, and the Brigadier grapple with the nightmarish invasion of the AUTONS — living, giant-sized plastic-modelled ‘humans’ with no hair and sightless eyes; waxwork replicas and tailors’ dummies whose murderous behaviour is directed by the NESTENE CONSCIOUSNESS — a malignant, squid-like monster of cosmic proportions and indescribably hideous appearance.”

John Grindrod’s excellent talk at the Target Book Club event last month made me revisit the blurb on the back of this novelisation, the first of more than 200 books by Terrance Dicks, originally published simultaneously in hardback and paperback on 17 January 1974. That blurb, a single, thrilling sentence chock full of adjectives, was probably written by commissioning editor Richard Henwood.

Heywood’s brilliant instincts for what would appeal directly to his readership of 11-14 year-olds also included changing the titles of stories to focus on the monsters. The TV story Spearhead from Space thus became Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion.

Published on the same day was Malcolm Hulke’s novelisation of his own TV story, Doctor Who and the Silurians. This already had a monster-focused title but “Silurian” is a technical word referring to a specific period of geological time. Henwood went for something simpler and more vivid, a title to immediately conjure a mental image: Doctor Who and the Cave-Monsters (with hyphen). The cover, by Chris Achilleos, promises monsters plural: a T-rex and a Silurian.

Published on the same day was Malcolm Hulke’s novelisation of his own TV story, Doctor Who and the Silurians. This already had a monster-focused title but “Silurian” is a technical word referring to a specific period of geological time. Henwood went for something simpler and more vivid, a title to immediately conjure a mental image: Doctor Who and the Cave-Monsters (with hyphen). The cover, by Chris Achilleos, promises monsters plural: a T-rex and a Silurian.Of course, these new titles also fitted with those of the first three Target novelisations, published on 2 May 1973 and all reissued versions of books originally published in the 1960s. Two were originally published with snappy, simple titles focused on the antagonists: Doctor Who and the Zarbi and Doctor Who and the Crusaders. Henwood changed Doctor Who in an Exciting Adventure with the Daleks to Doctor Who and the Daleks to fit (though only on the front cover; it retains its original title inside).

As John Grindrod pointed out in his talk, these three Target reissues were published as part of the wider “Target Adventure Series”. The inside cover of each lists the other two Doctor Who books and also a non-Doctor Who adventure story called The Nightmare Rally. Written by Pierre Castex, this was again a reissue of a book originally published in the 1960s, which the new cover proclaimed was “Now an exciting Walt Disney film, Diamonds on Wheels”, and was published ahead of the film being released in cinemas later that year.

Also listed as part of the Target Adventure Series in these first Doctor Who books was a non-fiction title, Wings of Glory — written by Graeme Cook and about the history of war in the air. Another non-fiction title, None but the Valiant, about war at sea, was,

“to be published in Target Books, September 1973”.

Note that there was no mention here of further Doctor Who books as “in preparation” — a feature of later Doctor Who novelisations. Henwood had written to the BBC on 3 November 1972 expressing a wish to novelise further Doctor Who stories beyond these three reissues but it seems he and the team at Target waited to see how those sold before formally committing to more.

They sold extremely well: The Target Book by David J Howe with Tim Neal, which is essential reading on this stuff, estimates an initial print run of 20,000 copies per title, reprint within six months (October/November 1973), and again three months later (January/February 1974). One of the books, Doctor Who and the Daleks, was no. 6 in the WH Smith top 10 on 20 July 1973.

By this point, with the books clearly a success, six new Doctor Who titles had been commissioned. As well as Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion and Doctor Who and the Cave-Monsters, there were to be novelisations of the following TV stories:

Day of the Daleks (published as Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks by Terrance Dicks on 18 March 1974)Colony in Space (published as Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon by Malcolm Hulke the same day)The Daemons (published as Doctor Who and the Daemons by Barry Letts on 17 October 1974)The Sea Devils (published as Doctor Who and the Sea-Devils, with hyphen, by Malcolm Hulke the same day)At this stage, Mac Hulke was the backbone of the Target range, writing half of the new books — all based on his own TV serials. To begin with, all his books were to be retitled with punchier titles: Doctor Who and the Sea-Devils was originally going to be put out as Doctor Who and the Sea-Monsters (as per the “in preparation” list in the first editions of Doctor Who and the Day of the Daleks and Doctor Who and the Doomsday Weapon). The changed title and hyphen were surely to help indicate that this was a direct sequel to Doctor Who and the Cave-Monsters.

My guess is that the title was changed back to Doctor Who and the Sea-Devils following the last-minute decision to repeat the omnibus version of The Sea Devils on TV on 27 May 1974, a few months ahead of publication. Perhaps it was also to ensure the title matched the list of all Doctor Who TV serials given in the Radio Times special marking 10 years of Doctor Who, published in November 1973. Another title listed as “in preparation” in March 1974, Doctor Who and the Yeti, was also changed back to its TV title and published as Doctor Who and the Abominable Snowmen.

However, before Target abandoned this policy of changing titles to make them more simple, vivid and monster-focused, this approach seems to have had a profound effect on Hulke and others working on the TV show. On 2 July 1973 — around the same time that these first six new novelisations were confirmed — Hulke was also commissioned to write the scripts for a new six-part Doctor Who story on TV called Timescoop. By early August, that name had been changed to Invasion of the Dinosaurs. TV story Death to the Daleks, commissioned the same day, already had this kind of title but Return to Peladon, commissioned on 12 July from writer Brian Hayles, became The Monster of Peladon (Hayles was also soon commissioned by Target to novelise his first Peladon story).

Terrance Dicks and Barry Letts had originally planned to end the 1974 TV series of Doctor Who by killing off the Master, as played by Roger Delgado, in a story to be called The Final Game. When Delgado died and then star Jon Pertwee decided to leave Doctor Who, the finale became a story to kill-off the Third Doctor, now with a monster-focused title: Planet of the Spiders. In the following season of TV adventures, the titles of all but one story — The Ark in Space — included the name of the monster.

The books introduced other stuff that found its way into the TV show, too. The Making of Doctor Who (1972) by Hulke and Dicks revealed that Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart’s first name is “Alastair”. This fact is given again in Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion, published months before studio recording of the name’s first use on screen in Part One of Planet of the Spiders.

Then there’s this, from the climax of the Auton invasion book, as one of the monstrous shop-window dummies is caught in the blast of a grenade.

“An Auton arm blown clear from the body continued to lash wildly around the room, spitting energy bolts like a demented snake.” (p. 146)

It’s surely the inspiration for what happens in the TV episode Rose (2005).

I’ve much more to say about what Terrance does and doesn’t do in his first novelisation, but I’ll save it for my forthcoming biography of him...

August 14, 2025

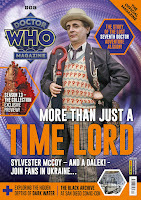

Doctor Who Magazine #620

The new issue of the official Doctor Who Magazine is out today and includes After Image by me, in which I look again at recent TV episodes Lucky Day, The Story & the Engine, The Interstellar Song Contest, Wish World and The Reality War.

The new issue of the official Doctor Who Magazine is out today and includes After Image by me, in which I look again at recent TV episodes Lucky Day, The Story & the Engine, The Interstellar Song Contest, Wish World and The Reality War.I, in turn, get reviewed, with Jamie Lenman casting his critical eye over Smith and Sullivan: Reunited, of which I wrote one episode. He says Blood Type is "complex and nuanced", which is nice.

There are lots of other goodies this issue, not least Gary Gillatt's lovely piece about the war service of the actors who played the first three Doctors Who.

Anyway. I'm on deadlines so must dash. Will write up notes on some recent books read and post them here asap.

August 3, 2025

Daumier, by Sarah Symmons

In the summer of 1993, me and my friend O. trekked up to London to work our way round various galleries, ticking off a longish list of paintings we’d been given as part of our A-level art course. It was mostly 19th century stuff, Turner and Constable through to the post-Impressionists.

In the summer of 1993, me and my friend O. trekked up to London to work our way round various galleries, ticking off a longish list of paintings we’d been given as part of our A-level art course. It was mostly 19th century stuff, Turner and Constable through to the post-Impressionists. I scribbled basic pencil sketches of the ones I thought most interesting and bought postcards of anything on the list. Later, compiling this in an A4 folder to hand it in to our teacher, I realised that while the postcards reproduced the paintings much more accurately than my sketches, they didn’t always convey their effect. On my sketch of Monet’s Water Lilies, I added little stick figures of people in the National Gallery, to get across that it took up a whole, enormous wall. I got extra marks for that.

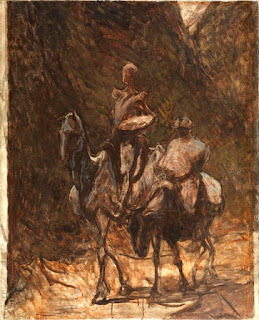

It was also interesting to see which paintings I’d thought worth sketching had or hadn’t been selected for reproduction as postcards. Portraits of single individuals and landscapes or real places tended to get reproduced. Odder, more interesting stuff tended not to. In the Courtauld Institute, I bought two postcards of a painting that particularly spoke to me — one for my homework project and one for my bedroom wall. I couldn’t say at the time what it was about Don Quixote and Sancho Pancha (c. 1870-72) by Honoré Daumier that so held by attention. I’ve thought about it a lot since.

Honoré Victorin Daumier, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, c. 1868-72, The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust). Image courtesy of the Courtauld.

Honoré Victorin Daumier, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, c. 1868-72, The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust). Image courtesy of the Courtauld.For one thing, it’s an unfinished painting, the work of an old artist in the process of going blind. That may account for the murky, dream-like quality and the half-formed figures — an impressionistically gaunt Quixote and his horse. Yet this crude, skeletal figure sits tall and proud, shoulders back, form in total contrast to the execution. If you know the story (I think I learned it after first seeing this painting), you’ll know Quixote is a fantasist, convinced he’s on an epic, noble quest. The posture here is his delusion.

Beside him, Sancho Panzo is a heftier silhouette, a little slumped upon the silhouette of a donkey. We get a sense of these two contrasting characters from this barest outline. They are dwarfed by the high, steep, dark terrain behind them, for all they are so prominent in the composition. But on they stride — Quixote proudly, Sancho with reservation — into the light.

I must have bought Sarah Symmons’ 2004 book on Daumier around the time it was published. Reading it again, I’m amazed by how prolific he was, producing some 4,000 lithographs, 1,000 woodcuts, 800 drawings and watercolours, 300 paintings and 50 pieces of sculpture. From this, Symmons calculates an extraordinary pace of work:

“Daumier completed a new work every two or three days of his adult life, except for the last three or four years when he was blind” (p. 22)

Even so, we might query that word “completed”; he was notorious for not finishing work. Also extraordinary is Symmons tracing what Daumier was probably paid, not least for his lithograph work for Parisian magazines. He was, at least at times, on good money — and yet frequently poor and more than once bankrupt (p. 10). Sadly, there seems to be little surviving in the way of contemporary sources to explain this discrepancy.

Again, when Symmons says,

“His subject matter was limited to human activity,” (p. 16)

I think it would be better to say “focused on”. As she says, the vast majority of his work has striking figures in the foreground, no middle-ground and then a background at some distance. The effect is like a tableau, or portrait mode on a phone camera.

Daumier was influenced by a range of other artists — his contemporaries, classical sculpture, Goya and Rembrandt. Symmons says Rembrandt had a particular effect on him from the late 1850s,

“after several new masterpieces by the Dutch artist were acquired by Napoleon III” (p. 99).

Presumably, these pieces were exhibited and Daumier went to see them. But I wonder how he — and other artists — accessed such works. How much were they influenced by reproductions in print rather than the real thing? Basically, to what extend did Daumier learn and develop his craft through the equivalent of postcards?

August 2, 2025

Stone & Sky, by Ben Aaronovitch

This is the tenth full-length novel in the Rivers of London series about a London copper who is also a wizard, and it is a delight. I bought it for the Dr when she was feeling a bit low and it worked its magic.

This is the tenth full-length novel in the Rivers of London series about a London copper who is also a wizard, and it is a delight. I bought it for the Dr when she was feeling a bit low and it worked its magic.Peter Grant and his extended family are in Scotland on holiday and to look into alleged sightings of a huge panther - or, melanistic leopard to be precise. As well as liaising with the local police to investigate this “weird bollocks”, Peter must also wrangle his parents, his toddler twins, his river goddess partner, and apprentice Abigail — who tells half of this story herself.

It’s smart and funny, and kept be guessing to the end. As always, I’m in awe of Ben’s ability to create such a vast range of rich characters, and how he grounds the fantastic elements in the mundane. The details — from the stone which built Aberdeen to the differences in police procedure and legislation once you cross the Border, are exemplary. I’ve been learning lots about scuba diving over the last year (as the Lord of Chaos is doing a course in it) and so found the threat at the end particularly tense.

There are loads of nerdy references, the Doctor Who ones including Daleks (p. 26), Peter’s explanation of his job,

“I deal with the odd, the unexplained, anything on earth…” (p. 108).

and what might be a reference to one of Ben’s own Doctor Who stories, in using the word “obstreperous” (p. 153). I wonder, too, if there’s an echo of Doctor Who and the Sea Devils by Malcolm Hulke in some of what goes on here.

It’s fun to pick up on this stuff and the other nerdery (such as Abigail working out the physics of mermaids). And it’s fun following character’s personal lives — the impact on Peter of being a dad, the love lives of Abigail and of Indigo the fox, the hints we get about Dr Abdul Walid’s early, wild years.

So many detectives have terrible personal lives and rub people up the wrong way. Peter is a charmer (literally!) and peacemaker, and it makes him and his world very engaging company.

Rivers of London novels I've also blogged about:

Lies SleepingFalse ValueAmongst Our WeaponsRivers of London novellas:

What Abigail Did That SummerThe October ManThe Masquerades of SpringSimon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers