Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 58

August 9, 2018

Journey up the Nile, the Egyptian Diary of Marianne Brocklehurst

Last week, I visited the West Park Museum in Macclesfield as research for my forthcoming Radio 3 documentary, “Victorian Queens of Ancient Egypt”, to be broadcast early next year.

The museum was the idea of Marianne Brocklehurst (1832-98), the well-off daughter of silk manufacturer, banker and Liberal MP John Brocklehurst (1788-1870), and I’m investigating Marianne’s own politics and why she, and the industrial north more generally, might have felt an affinity for the Pharaohs.

Marianne apparently made five trips to Egypt, and the museum has many of the artefacts she acquired along with her drawings and paintings. In 2017, the museum published “Journey Up the Nile”, a transcript of Marianne’s diary from her first trip. It’s a nice, hardback edition on glossy paper, including many illustrations and photographs, and an introduction by honorary curator Alan Hayward that helps set the scene. (The only thing lacking is a map, so I referred to the one in Alan’s 2013 pamphlet, “The Story of the Collection – How West Park Museum Got Its Ancient Egyptian Objects.”)

Marianne apparently made five trips to Egypt, and the museum has many of the artefacts she acquired along with her drawings and paintings. In 2017, the museum published “Journey Up the Nile”, a transcript of Marianne’s diary from her first trip. It’s a nice, hardback edition on glossy paper, including many illustrations and photographs, and an introduction by honorary curator Alan Hayward that helps set the scene. (The only thing lacking is a map, so I referred to the one in Alan’s 2013 pamphlet, “The Story of the Collection – How West Park Museum Got Its Ancient Egyptian Objects.”)

The diary begins on 11 November 1873, as Marianne sets off from Macclesfield with her travelling companion Mary Booth (1830-1912), Marianne’s young nephew Alfred and manservant George Lewis. The entries are mostly short, single paragraphs, the detail in the accompanying sketches. But there’s a sense of fun and adventure, Marianne seeming to relish the small hardships.

They pass through France and Italy, losing some of Alfred’s luggage along the way, recovering it, then losing track of time – presumably because of so much travelling by night - to arrive at Brindisi a day early for their boat across the Mediterranean. There are comic sketches of people falling over themselves during the very rough crossing, which leads to their boat ending up a hundred miles off course.

Although they reach Alexandria on 28 November, it’s another day before they’re cleared to land – 18 days after setting off from home. Stuck on board for that last evening, Marianne and Mary – the MBs, as they were known – meet other tourists, including novelist Amelia Edwards (1831-92), who will follow much of their course down and up the Nile on another, grander boat.

Edwards would later establish the Egyptian Exploration Fund (now Society) and provide a legacy for the first professorship of Egyptian Archaeology – awarded to Flinders Petrie – so she’s a significant figure in the discipline. This is from before all that, but she’s hardly a young girl. She’s a well-established professional writer, and in her early 40s – as are the two MBs.

In 2016, Historic England Grade II listed the grave Edwards shares with her long-term companion Ellen Drew Brayshaw, noting its importance in LGBT history. The MBs were also long-term companions who would be buried together. What can we read into that?

“We should not take a modern attitude to two women living together,” says Alan Hayward in his 2013 pamphlet, “for in those days, when a woman’s role was to raise a family and run the home, it was the only way for independently minded wealthy women to ‘do their own thing’.”

I scoured the diary looking for anything that might hint at something more. At no point does she tell us what their relationship is – but then she also doesn’t spell out her relationship to Alfred (her nephew) or George (her servant). The assumption is that her readers will know, because this diary was likely passed between friends and not intended for publication.

She is candid about certain things, describing at some length and with much excitement how she and Mary smuggled a mummy case out of the country, bribing officials along the way, and noting the very serious punishments those involved risked by helping her. Yet she is coy about exactly how much she paid – something less than a £100 but a “good round number in sovereigns” (p. 91).

So we’re left to interpret what is left unsaid. Can we read anything into the moment that Mary “smokes a pipe over the oil can” (p. 36) with the sailors, which seems rather unladylike, or the delight the MBs take in “paying our baksheesh like a man” (p. 69)?

Other details are more sure. The four-month trek down and up the Nile is a well-established journey, the river busy with other tourists, some of them friendly and respectable, others – such as Cooks’ excursionists and some American Christians – behaving badly, carving their names in the monuments and leaving their rubbish behind them. Some things have not changed in a century and a half - just like the MBs, the Dr and I struggled to find the carving of Cleopatra on the wall of the temple at Dandara.

In other ways it's another world. There's the pith helmets and formal wear of the tourists in the pictures. There’s the risk of crocodiles, and thieves, and Marianne’s compassionate response when a trusted sailor turns out to have stolen from them.

The museum was the idea of Marianne Brocklehurst (1832-98), the well-off daughter of silk manufacturer, banker and Liberal MP John Brocklehurst (1788-1870), and I’m investigating Marianne’s own politics and why she, and the industrial north more generally, might have felt an affinity for the Pharaohs.

Marianne apparently made five trips to Egypt, and the museum has many of the artefacts she acquired along with her drawings and paintings. In 2017, the museum published “Journey Up the Nile”, a transcript of Marianne’s diary from her first trip. It’s a nice, hardback edition on glossy paper, including many illustrations and photographs, and an introduction by honorary curator Alan Hayward that helps set the scene. (The only thing lacking is a map, so I referred to the one in Alan’s 2013 pamphlet, “The Story of the Collection – How West Park Museum Got Its Ancient Egyptian Objects.”)

Marianne apparently made five trips to Egypt, and the museum has many of the artefacts she acquired along with her drawings and paintings. In 2017, the museum published “Journey Up the Nile”, a transcript of Marianne’s diary from her first trip. It’s a nice, hardback edition on glossy paper, including many illustrations and photographs, and an introduction by honorary curator Alan Hayward that helps set the scene. (The only thing lacking is a map, so I referred to the one in Alan’s 2013 pamphlet, “The Story of the Collection – How West Park Museum Got Its Ancient Egyptian Objects.”)The diary begins on 11 November 1873, as Marianne sets off from Macclesfield with her travelling companion Mary Booth (1830-1912), Marianne’s young nephew Alfred and manservant George Lewis. The entries are mostly short, single paragraphs, the detail in the accompanying sketches. But there’s a sense of fun and adventure, Marianne seeming to relish the small hardships.

They pass through France and Italy, losing some of Alfred’s luggage along the way, recovering it, then losing track of time – presumably because of so much travelling by night - to arrive at Brindisi a day early for their boat across the Mediterranean. There are comic sketches of people falling over themselves during the very rough crossing, which leads to their boat ending up a hundred miles off course.

Although they reach Alexandria on 28 November, it’s another day before they’re cleared to land – 18 days after setting off from home. Stuck on board for that last evening, Marianne and Mary – the MBs, as they were known – meet other tourists, including novelist Amelia Edwards (1831-92), who will follow much of their course down and up the Nile on another, grander boat.

Edwards would later establish the Egyptian Exploration Fund (now Society) and provide a legacy for the first professorship of Egyptian Archaeology – awarded to Flinders Petrie – so she’s a significant figure in the discipline. This is from before all that, but she’s hardly a young girl. She’s a well-established professional writer, and in her early 40s – as are the two MBs.

In 2016, Historic England Grade II listed the grave Edwards shares with her long-term companion Ellen Drew Brayshaw, noting its importance in LGBT history. The MBs were also long-term companions who would be buried together. What can we read into that?

“We should not take a modern attitude to two women living together,” says Alan Hayward in his 2013 pamphlet, “for in those days, when a woman’s role was to raise a family and run the home, it was the only way for independently minded wealthy women to ‘do their own thing’.”

I scoured the diary looking for anything that might hint at something more. At no point does she tell us what their relationship is – but then she also doesn’t spell out her relationship to Alfred (her nephew) or George (her servant). The assumption is that her readers will know, because this diary was likely passed between friends and not intended for publication.

She is candid about certain things, describing at some length and with much excitement how she and Mary smuggled a mummy case out of the country, bribing officials along the way, and noting the very serious punishments those involved risked by helping her. Yet she is coy about exactly how much she paid – something less than a £100 but a “good round number in sovereigns” (p. 91).

So we’re left to interpret what is left unsaid. Can we read anything into the moment that Mary “smokes a pipe over the oil can” (p. 36) with the sailors, which seems rather unladylike, or the delight the MBs take in “paying our baksheesh like a man” (p. 69)?

Other details are more sure. The four-month trek down and up the Nile is a well-established journey, the river busy with other tourists, some of them friendly and respectable, others – such as Cooks’ excursionists and some American Christians – behaving badly, carving their names in the monuments and leaving their rubbish behind them. Some things have not changed in a century and a half - just like the MBs, the Dr and I struggled to find the carving of Cleopatra on the wall of the temple at Dandara.

In other ways it's another world. There's the pith helmets and formal wear of the tourists in the pictures. There’s the risk of crocodiles, and thieves, and Marianne’s compassionate response when a trusted sailor turns out to have stolen from them.

“Let us not be hard on his memory considering that, like the rest of the sailors, his pay was only thirty shillings a month for three or four months at the most and then nothing to do or to get until the next season began.” (pp. 86-7)There is a great deal more, but I won’t share all my notes here as they’re for the documentary...

Published on August 09, 2018 07:38

August 8, 2018

The World of Doctor Who

In shops now, The World of Doctor Who is the latest - and 50th - special edition of Doctor Who Magazine, and examines the past, present and future of fandom.

In shops now, The World of Doctor Who is the latest - and 50th - special edition of Doctor Who Magazine, and examines the past, present and future of fandom.I've written three features:

SHOW YOUR APPRECIATION

'Calling all Doctor Who fans...' The Doctor Who Appreciation Society was launched in 1976. Paul Winter, the current Co-ordinator, explains how its role has changed over the years.

THE FAN SHOWS

From humble beginnings in the early 70s, fan productions have grown increasingly sophisticated, nurturing careers and featuring numerous stars from television Doctor Who.

(I spoke to animator Lucy Crewe from Creative Cat FX, director Kevin Jon Davies, Den Valdron who wrote The Great Unauthorized Doctor Stories , producer Keith Barnfather, puppeteer Alisa Stern and the team behind Devious - Ashley Nealfuller, David Clarke, Stephen Cranford and Mark Jones.)

CONVENTIONAL WISDOM

What began in a church in London in 1977 has now become a crucial part of many fans' social calendars. This is the essential guide to Doctor Who conventions.

(I spoke to Dexter O'Neill at Fantom, Oni Hartstein of (Re)Generation Who, and fans Prakash Bakrani, Jennifer and Ed Comstock, Yashoda Sampath, Jenny Shirt and Andrea @TARDISParrot.)

Published on August 08, 2018 08:21

August 4, 2018

The Princess Diarist, by Carrie Fisher

The friend I borrowed this from got it for Christmas in 2016, and was 33 pages in when news arrived that Carrie Fisher had died. My friend had not been able to read any further.

The friend I borrowed this from got it for Christmas in 2016, and was 33 pages in when news arrived that Carrie Fisher had died. My friend had not been able to read any further.Even while Fishe was alive, this would have been an uncomfortable read. It's based on diaries she kept in 1976 and subsequently forgot about, detailing her thoughts while filming the first Star Wars film in London, and having an affair with her married co-star, Harrison Ford. The "diaries" - they're more a series of thoughts and poems - make up the middle third of the book.

The first third sets the scene, detailing how she got to be in Star Wars, her background and expernece of show business, and her lack of self-esteem, and then how the affair began. She's withering, witty and honest, with a brilliant, sometimes filthy turn of phrase (describing Ford at one point as "the snake in my grass"). The effect is that she's addressing us, the reader directly, and challenging us to question her actions and motives.

"But though I do admittedly lay bear far more than the average bear, before disclosing anything that is possibly someone else's secret to tell, I make it a practice to first let that person know about my intention. (Aren't I ethical? I thought you'd think so.)"That would seem to mean she consulted Ford prior to publication, though it's never stated as such and he's not mentioned in her acknowledgements.

Carrie Fisher, The Princess Diariest, p. 51.

The account of how she and Ford got together is funny, revealing much about them both, and she picks out details in retrospect that better explain how things happened. I'd read some of this before in a newspaper, and it's heartfelt, sweet and desperately sad, grief for a life and love long since past.

The last third is more about the love affair that followed the release of Star Wars, the affect her character had on the public. In a long chapter, she details the experience of being a guest at Comic Con, the doubts she has about this kind of "lap-dancing" for cash.

"It's certainly a higher form of prostitution: the exchange of a signature for money, as opposed to a dance or a grind. Instead of stripping off clothes, the celebrity removes the distance created by film or stage. Both traffic in intimacy.""I need you to know I'm not cynical about fans ... I'm moved by them," she assures us (p. 223), "For the most part they're kind and courteous" (p. 224). She's shrewd, too, about the appeal of Princess Leia, and why Star Wars can mean so much to people, which they want to share with her. Even so, it's daunting, exhausting, just to read about having so much significance projected on to you - not you, someone who looks like you used to.

Ibid., p. 211.

"I wish I'd understood the kind of contract I signed by wearing something like that [metal bikini], insinuating I would and will always remain somewhere in the erotic ballpark appearance-wise, enabling fans to remain connected to their younger, yearning selves - longing to be with me without having to realize that we're both long past all of this in any urgent sense, and accepting it as a memory rather than an ongoing reality."That's really struck me: the desperate futility of holding on to past love. The sadness of the book, and of the loss of Carrie Fisher, is a grieving for ourselves.

Ibid., pp. 228.

See also: me on Garry Jenkins's Empire Building - The Remarkable Real Life Story of Star Wars

Published on August 04, 2018 05:49

July 30, 2018

Illuminae, by Amie Kaufmann & Jay Kristoff

This brilliant novel had me hooked from its first pages - in which a school is attacked by a huge spaceship. In the heart of the maelstrom are Katy and Ezra, a couple of teenagers who just broke up. We follow their desperate efforts to survive...

This brilliant novel had me hooked from its first pages - in which a school is attacked by a huge spaceship. In the heart of the maelstrom are Katy and Ezra, a couple of teenagers who just broke up. We follow their desperate efforts to survive...From its thrilling opening, Illuminae builds and builds, with twist after shocking twist. The teenagers are smart and funny and brave, so we're totally with them every step, and share every agony they go through. And there's a lot of that - more than once I muttered, "No!" as I was reading. It's hard not to say more without spoiling the delights.

As well as the exceptional plotting and characterisation, it's an epistolary novel, made up from a stash of emails, analysis of CCTV and other recordings. That's done really well and sustained throughout - no mean achievement in itself - which adds to the intimacy and realism as we look over Katy and Ezra's shoulders.

There are two further books in the same series - Gemina and Obsidio - and the authors are working on a new series, beginning with Aurora Rising next year. They are all added to the reading pile. Illuminae is hugely recommended.

Published on July 30, 2018 09:01

July 23, 2018

Doctor Who: The Women Who Lived

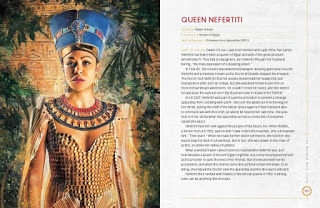

BBC Books have announced an exciting new volume, Doctor Who: The Women Who Lived, to be published in September.

BBC Books have announced an exciting new volume, Doctor Who: The Women Who Lived, to be published in September.Written by Christel Dee and me (as her plucky assistant), it features profiles of more than 75 women from the whole history of Doctor Who, including friends who've travelled in the TARDIS, recurring characters and some one-off people we particularly like... There's an extended entry on the new, Thirteenth Doctor, and details about her new friend, Yasmin.

The cover is by the amazing Lee Binding, and the illustrations inside are by a team of brilliant women: Jo Bee; Gwen Burns; Sophie Cowdrey; Lydia Futral; Kate Holden; Bev Johnson; Dani Jones; Sonia Leong; Cliodhna Lyons; Mogamoka; Valentina Mozzo; Naniiebim; Lara Pickle; Emma Price; Katy Shuttleworth; Natalie Smillie; Rachael Smith; Raine Szramski; Tammy Taylor; Emma Vieceli; Caz Zhu

The Women Who Lived, announced on DoctorWho.TV

Published on July 23, 2018 04:50

July 20, 2018

Comics bought from South London Comic & Zine Fair

As well as handing out copies of our new Bibbly-Bob comic, I bought a bunch of things from the stalls at last weekend's South London Comic & Zine Fair. There was a wealth of exciting stuff on offer, but herding a seven year-old meant I had to actively steer past anything that looked too adult. Things browsed and bought were dictated by what appealed - and wouldn't terrify - him.

Plastic by Nick Soucek is a small, square 48pp comic with one panel per page, telling the history of the oil that becomes the plastic that becomes a bottle of water, from the age of the dinosaurs on. It's a brilliantly simple, and quite caught his Lordship's imagination - and mine.

The Boy & the Owl is a rectangular comic the same height as Plastic, with art by Sabba Khan illustrating a poem by Paul Jacob Naylor. It's a sort of goth fairy-tale, and we bought it because when his Lordship picked up Sabba's Bob the Goldfish - which seemed so much just his thing - I was quickly, discreetly warned that he might not like the ending...

Lord Chaos ran to Gary Northfield's stall, having loved Gary's Garden which we bought from him last year. This time, his Lordship went for Teenytinysaurs , even if it ate up all his pre-agreed budget in one go. I've not had a chance to look through it much as his Lordship keeps it close.

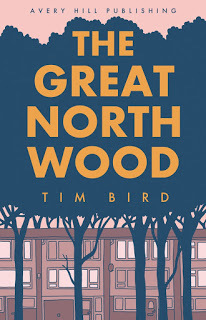

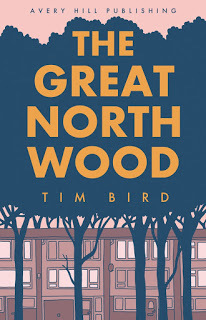

The Great North Wood by Tim Bird immediately caught my eye - a handsome graphic novel in blue and orange and pink telling the history of the part of south London in which I live. It covers a lot of ground, and includes some marvellous details - such as the story that Honor Oak Park owes its name from Elizabeth I getting drunk at a picnic - while showing the traces of woodland still evident in the streets I walk every day.

The Great North Wood by Tim Bird immediately caught my eye - a handsome graphic novel in blue and orange and pink telling the history of the part of south London in which I live. It covers a lot of ground, and includes some marvellous details - such as the story that Honor Oak Park owes its name from Elizabeth I getting drunk at a picnic - while showing the traces of woodland still evident in the streets I walk every day.

In exchange for a copy of Bibbly-Bob, Tim also gifted us his Rock & Pop , a simpler, more traditional zine, with each single page devoted to a particular song of significance to him. The result is an intimate autobiography, full of warmth and wit.

Lord Chaos, meanwhile, was chatting to Andy Poyiadgi, delighted by the simple silliness of A Cup of Tea Will Sort You Out (which we bought) and the various origami and other intriguingly folded creations (which we didn't).

I also picked up an anthology of work by Dalston Comic Collective - a group of adults who meet once a month to make comics - and was delighted to find it included work by my old mate Finally, there was Ocular Anecdotes number 3 by Peter Cline, a visually striking comic the size and heft of a newspaper, described on Cline's website at "pictographic literature". It looks amazing, and I've puzzled over it again and again - but am still not quite sure what it is or what it's about.

Plastic by Nick Soucek is a small, square 48pp comic with one panel per page, telling the history of the oil that becomes the plastic that becomes a bottle of water, from the age of the dinosaurs on. It's a brilliantly simple, and quite caught his Lordship's imagination - and mine.

The Boy & the Owl is a rectangular comic the same height as Plastic, with art by Sabba Khan illustrating a poem by Paul Jacob Naylor. It's a sort of goth fairy-tale, and we bought it because when his Lordship picked up Sabba's Bob the Goldfish - which seemed so much just his thing - I was quickly, discreetly warned that he might not like the ending...

Lord Chaos ran to Gary Northfield's stall, having loved Gary's Garden which we bought from him last year. This time, his Lordship went for Teenytinysaurs , even if it ate up all his pre-agreed budget in one go. I've not had a chance to look through it much as his Lordship keeps it close.

The Great North Wood by Tim Bird immediately caught my eye - a handsome graphic novel in blue and orange and pink telling the history of the part of south London in which I live. It covers a lot of ground, and includes some marvellous details - such as the story that Honor Oak Park owes its name from Elizabeth I getting drunk at a picnic - while showing the traces of woodland still evident in the streets I walk every day.

The Great North Wood by Tim Bird immediately caught my eye - a handsome graphic novel in blue and orange and pink telling the history of the part of south London in which I live. It covers a lot of ground, and includes some marvellous details - such as the story that Honor Oak Park owes its name from Elizabeth I getting drunk at a picnic - while showing the traces of woodland still evident in the streets I walk every day. In exchange for a copy of Bibbly-Bob, Tim also gifted us his Rock & Pop , a simpler, more traditional zine, with each single page devoted to a particular song of significance to him. The result is an intimate autobiography, full of warmth and wit.

Lord Chaos, meanwhile, was chatting to Andy Poyiadgi, delighted by the simple silliness of A Cup of Tea Will Sort You Out (which we bought) and the various origami and other intriguingly folded creations (which we didn't).

I also picked up an anthology of work by Dalston Comic Collective - a group of adults who meet once a month to make comics - and was delighted to find it included work by my old mate Finally, there was Ocular Anecdotes number 3 by Peter Cline, a visually striking comic the size and heft of a newspaper, described on Cline's website at "pictographic literature". It looks amazing, and I've puzzled over it again and again - but am still not quite sure what it is or what it's about.

Published on July 20, 2018 12:58

July 14, 2018

Bibbly-Bob returns

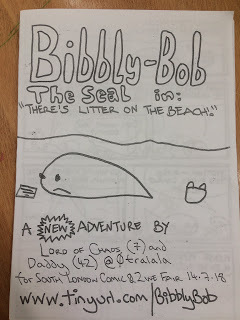

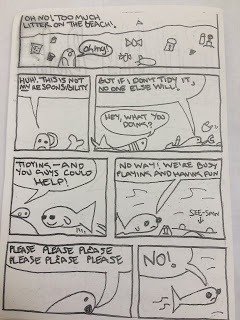

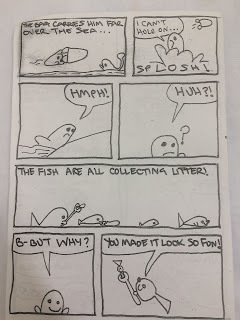

After its exclusive media launch at the South London Comic & Zine Fair this afternoon, here is the new Bibbly-Bob the Seal comic - in which (oh no!) there is litter on the beach. Story and art by Lord of Chaos, with inking and lettering by his humble servant.

After its exclusive media launch at the South London Comic & Zine Fair this afternoon, here is the new Bibbly-Bob the Seal comic - in which (oh no!) there is litter on the beach. Story and art by Lord of Chaos, with inking and lettering by his humble servant.(The original Bibbly-Bob comic, created for last year's event, can be found at www.tinyurl.com/BibblyBob.)

Published on July 14, 2018 14:15

July 12, 2018

Binti, by Nnedi Okorafor

I really enjoyed this 90-page science-fiction novella about a girl who runs away from home to go to space university, when her ship is attacked by murderous aliens...

I really enjoyed this 90-page science-fiction novella about a girl who runs away from home to go to space university, when her ship is attacked by murderous aliens...The novella won both Hugo and Nebula awards, and if the word of mouth wasn't already good, the cover boasts a too-die-for endorsement:

"There's more vivid imagination in a page of Nnedi Okoroafor's work than in whole volumes of ordinary fantasy epics." - Ursula K. Le GuinA lot of science-fiction is about encounters between white Earth people and "the other" out in space. Binti, the narrator of this story, is the first of the Himba people of northern Namibia to be offered a place at Oomza University, and other humans (even darker skinned ones) treat her as exotic and strange.

The otjize paste with which she daubs her hair and skin is made from the clay back home, a physical link to her culture and history that plays a key part in the story. The texture and smell of it are part of what makes the telling so sensuous and rich.

A lot of science-fiction is also about war and conquest, the future all jostling colonial powers. Binti feels like it's going to be some typical invasion, but is more about what it takes to bridge the gap between different groups, whether human or otherwise. In doing so, Binti becomes someone, something, else. That willingness to reach out, to leave home and migrate, to embrace the strange, is a defiant, heroic act.

Her story continues in Binti: Home (2017) and Binti: The Night Masquerade (2018), which I hope to get to shortly.

Published on July 12, 2018 08:11

July 5, 2018

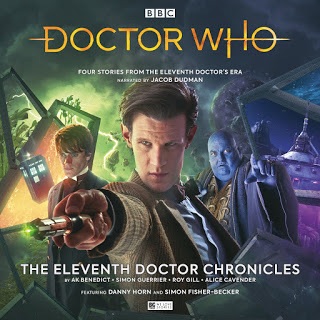

Eleventh Doctor Chronicles cover

Our next month is

Doctor Who - The Eleventh Doctor Chronicles

, with this tremendous cover by Tom Webster:

I've written one of the four stories: The Top of the Tree, starring Jacob Dudman and Danny Horn, and directed by Helen Goldwyn.

I've written one of the four stories: The Top of the Tree, starring Jacob Dudman and Danny Horn, and directed by Helen Goldwyn.

On one of their annual jaunts, young Kazran Sardick and the Doctor find themselves in trouble when the TARDIS is tangled in the branches of a very strange, very large tree.

They emerge into a habitat where myriad species fight for survival: an ecosystem of deadly flora and fauna, along with a tribe of primitive humans.

This is a mystery which can only be solved by climbing. But what will they find at the top of the tree?

Published on July 05, 2018 08:16

July 4, 2018

The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla

This book of 21 essays is, in the words of the editor's note, "a document of what it means to be a person of colour now."

This book of 21 essays is, in the words of the editor's note, "a document of what it means to be a person of colour now."While "the universal experence is white", we're presented with "21 universal experiences: feelings of anger, displacement, defensiveness, curiousity, absurdity - we look at death, class, microaggression, popular culture, free movement, stake in society, lingual fracas, masculinity and more." It's insightful, funny, surprising and harrowing, and has got me thinking about my own assumptions and behaviour, that of the industry in which I work and society around me.

It's an excellent, wide-ranging book and I recommend it to anyone.

Tediously, I read it on the recommendation that it included something about the 1977 Doctor Who story The Talons of Weng-Chiang. What follows is some thoughts about that, though I'm still mulling it all over. (And you might like to watch my 2011 documentary related to this subject: "Race Against Time", included on the DVD of the 1972 story, The Mutants.)

Daniel York Loh's essay, "Kendo Nagasaki and Me", is about his response as a child to a particular wrestler on ITV's World of Sport, and the rare sight on mainstream TV in the 1970s of a "fellow 'oriental'" - as he puts it on p. 46. It's a heartfelt account, and he admits at the end that he may have muddled some of the historical details, but the point is not about the accuracy of his memory so much as what the relationship meant and still means to him.

Doctor Who - "my favourite TV programme in the world" (p. 52) - gets four and a bit paragraphs, an extended aside. Compared to today's version, the Doctor Who he grew up with "was populated almost entirely by white people ... For a remit with the whole of time and space as a pallette this is a bit crap frankly." He describes The Talons of Weng-Chiang as a,

"handsomely mounted Victorian Sax Rohmer homage", but with "one of the very worst examples of yellowface as a gang of silent, sinister and inscrutable (it's amazing how easily and often those words flow together) goons (the only appropriate description) appeared, led by an English actor called John Bennett sporting ridiculous false eyelids that looked like you could sit on them, skin made up yellow than a lump of cheese and speaking in a hopelessly mishmashed Chinese/Japanese hybrid accent that would had had Henry Higgins completely stumped. Not nearly so much as the fact that the BBC still carries a website page somewhere that heaps lavish praise on Mr Bennett's staggeringly silly turn, opining that, unless they knew, the viewer might be hard-pressed to tell that the English thesp wasn't in fact Chinese. Not unless they were under the impression that Chinese people had eyelids made from recycled skateboards and talked like Yoda in Star Wars when he's been on the ketamine, I think." (p. 53)My immediate response to this is to want to defend the story - which I enjoy and admire in many respects - and Doctor Who more generally, and even the BBC. For one thing, that praise for Bennett, on an old part of the BBC website, is clearly labelled as a quotation from a book. And yet, on checking, it still says:

"John Bennett is faultless as the inscrutable Li H'sen Chang, and his performance and make-up are so convincing that it is difficult to believe that he is not actually Chinese."That it is quoted from a book is no excuse. The quotation is from Doctor Who - The Television Companion, first published in 1998 by BBC Books, the cover proclaiming in large letters that it was, "the official BBC guide to every TV story." That is pretty authoritative, and the website repeats the book's assessment of the story in full, without comment. The book was republished as recently as 2013, and though that wasn't by BBC Books and without the authority of being an "official" publication, it still shows that this isn't merely something from the distant past.

Doctor Who - The Talons of Weng-Chiang: in detail

I don't mean to criticise the authors of the book or the editors of the website; I might well have written or quoted something similar without thought. That's the point: The Good Immigrant challenges bias and prejudice we might not even be aware of in ourselves, whatever our intentions and however much we want to believe that racism is something other, bad people do. It chimes with my recent reading of The Blunders of Our Governments . How do we address a white blindness we're not even aware of?

Criticism of The Talons of Weng-Chiang is not new, nor the defensive response. It's been argued that Doctor Who was better than other programmes made at the same time - but surely not all of them. And that doesn't negate the issues there anyway.

Or it is said the story itself critiques racist attitudes. Yes, this isn't simply Doctor Who trotting out the stereotypes of Sax Rohmer. For all Bennett's performance owes something to the version of Fu Manchu played by (the also white) Christopher Lee in the five films made in the 1960s, Chang is, ultimately, a rather sympathetic character, his motivation clear - the opposite of the "inscrutable". At the same time, the Doctor counters some of the prejudice shown by the Victorian Londoners in the story. But it's still bound up in racial and class-based assumptions, and the Doctor is visiting London anyway to educate his "savage" companion - an adjective with racist associations.

Or there's the argument that the BBC were required to only use actors who were members of Equity, which limited the number of Chinese or Chinese-descended actors who might have taken this particular role. That didn't mean there weren't any; I find myself imagining the story with Burt Kwuok playing Chang. But the casting of Bennett is also surely part of a - no doubt unconcious - tendency to have Chinese and East Asian characters played by actors of Jewish origin. Think also of Martin Miller as Kublai Khan in the 1964 Doctor Who story Marco Polo, or, more notably, Joseph Wiseman as Dr. No. Then recall the criticism above of villains who are,

"silent, sinister and inscrutable (it's amazing how easily and often those words flow together)".There's also the cumulative effect when actors of particular ethnic backgrounds do not get the same opportunties as their white counterparts. They don't develop their skills, so they're seen as less able than their white counterparts, so they miss out on further work, so they don't develop their skills...

It remains an issue, as described by young actor Paul Courtney Hyu, interviewed by Wei Ming Kam for "Beyond 'Good' Immigrants", another of the essays in the book. Hyu says that with so few opportunities for "East Asians" in film and TV in the UK, another actor, Elain Tan, has gone to America where she is "working her arse off."

But then Hyu addes "in a satisfied tone" an example of a UK show doing better than the rest:

"And she is the main person in our episode of Doctor Who [2015's Sleep No More]. So there are two Chinese in it, and she's got a Geordie accent, and pretty good too, I have to say. And I do my Yorkshire accent." (p.93)As a Doctor Who fan, I take some pride in that - but also know it's a rare example.

Himesh Patel mentions, on p. 64, watching Doctor Who while a teenager - one of the things he followed closely with his (white) peers so as to fit in, while they showed no interest in Bollywood music or films.

Anyway, all this has got me thinking - informing my perspective on old episodes as I watch them on Twitch and research them for the various magazines I write for, and challenging some assumptions in the script I'm late on at the moment. An aspect of a character has just been revised because this book made me realise an aspect of my own blindess, and pointed the way to do better.

Published on July 04, 2018 09:13

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers

Simon Guerrier isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.