Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 56

December 14, 2018

The Story of Susan Foreman

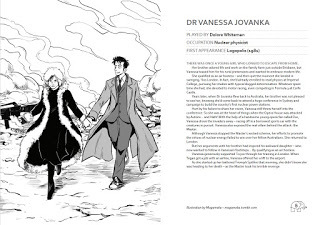

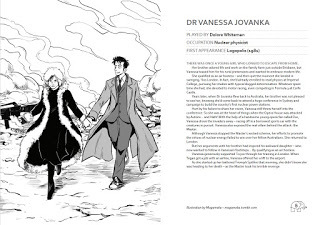

That splendid lot at BBC Studios have produced this lovely video telling the story of Doctor Who's granddaughter, Susan Foreman.

The text is by me and Christel Dee, from our book The Women Who Lived, but there are all new illustrations by Lara Pickle, Dani Jones, Caz Zhu, Mogamoka, Rachael Smith, Kate Holden, Sonia Leong and Gwen Burns. Hooray!

The text is by me and Christel Dee, from our book The Women Who Lived, but there are all new illustrations by Lara Pickle, Dani Jones, Caz Zhu, Mogamoka, Rachael Smith, Kate Holden, Sonia Leong and Gwen Burns. Hooray!

Published on December 14, 2018 04:27

December 10, 2018

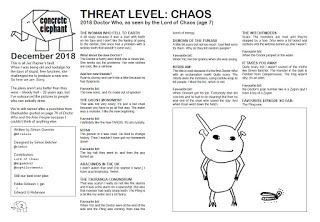

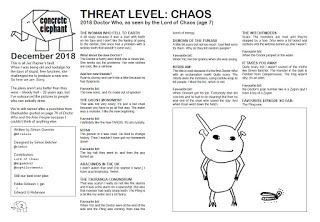

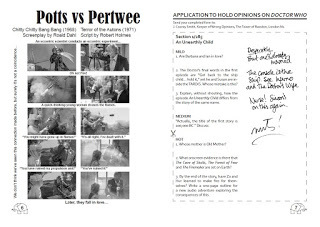

Concrete Elephant

A few weeks ago, I was being old and nostalgic about the days of Doctor Who fanzines, especially the ones handed round in the pub I used to frequent. In May 1999, I produced my own - the first issue of a stupid thing called Concrete Elephant. Last week, it raised once again its pachydermatous head...

Written by me

Cover and design by @nimbos

Contributors: Lord of Chaos, @Mogamoka2 and @SophIlesTweets

Written by me

Cover and design by @nimbos

Contributors: Lord of Chaos, @Mogamoka2 and @SophIlesTweets

Published on December 10, 2018 06:11

December 1, 2018

Transcription, by Kate Atkinson

This is brilliant. In 1950, Juliet Armstrong is a BBC radio producer working in Schools (the department always has a capital S). But ten years before, she worked for the government, transcribing recordings of a group of Nazi sympathisers - as well as doing some more active spy work. We cut back and forth between the two roles as a dark secret from her past threatens to return and engulf her...

This is brilliant. In 1950, Juliet Armstrong is a BBC radio producer working in Schools (the department always has a capital S). But ten years before, she worked for the government, transcribing recordings of a group of Nazi sympathisers - as well as doing some more active spy work. We cut back and forth between the two roles as a dark secret from her past threatens to return and engulf her...As a radio producer who still does a lot of transcribing myself, it all felt brilliantly authentic - for all Atkinson says in her afterword that she made so much of it up. In all the best ways, it has the feel of le Carre - with the language of moles and dead-letter drops. Juliet is just one of many in the book to move from MI5 to the BBC without quite leaving the former.

"There was a subtle - and perhaps not so subtle - emphasis in Schools on citizenship. Juliet wondered if it was to counter the instinct towards Communism." (p. 178)But the spy plot and moral uncertainties are just part of the appeal. The detail of ordinary life is all perfectly conveyed and compelling. When one of Juliet's broadcast programmes includes an actor clearly saying "fuck", it has just as much drama - and awful consequence - as any of the war stuff.

It's a wrily funny read, one constant theme Juliet's frustrated sex life. Her perspective full of pithy observations as she moves through the large cast of vividly drawn characters, many burdened with tragedy but doing their best to get on.

"How little it takes to make some people happy, Juliet thought. And how much it takes for others." (p. 231)Amid all this activity, this life, are some deftly placed clues to what's really going on - such as one character's caual thieving - which I didn't think to put together spot until very late. It's especially clever because often we're ahead of Juliet, spotting one character's sexuality before she has to have it explained. Only in the last section do we realise what the book is actually about. In fact, the one jarring moment is when Atkinson acknowledges that with a wink at the reader:

"Come now, quite enough exposition and explanation. We're not approaching the end of a novel, Miss Armstrong." (p. 315 - 14 pages from the end)The final revelation only makes me want to read the whole thing again straight away. It's so deceptively simple, such a pleasure to knock through, so rewarding at the end. A joy.

Published on December 01, 2018 23:49

November 20, 2018

Foundation, by Isaac Asimov

A chum tweeted about Foundation this summer, prompting me finally to read it.

A chum tweeted about Foundation this summer, prompting me finally to read it.It's a short, breezy book covering events over a hundred years. In the first section, 'psychohistorian' Hari Seldon is arrested for predicting the future - and the inevitable ruin of the Empire of which he's a subject. We gloss over the exact process by which he comes by this prediction, or how it's shown to be chillingly accurate. But the authorities are convinced he's right - so place him under house arrest.

Obviously, there are parallels here to the fate of Galileo, but it also made me think of the Drake equation - a clever attempt to quantify the unquanitifiable, marshalling the known unknowns involved to best estimate the number of live, chatty alien civilisations in our galaxy. I wondered if the equation had influenced Asimov, but it turns out the equation was conjured a decade after the book.

In fact, Asimov is ahead of the game quite a lot. On page 8, there's an ingenious device that sounds almost contemporary: a ticket that glows when you're heading in the right direction. Then, as a result of Seldon's predictions, a project is established to gather the Empire's knowledge in the hope it will survive. Sections are book-ended by excerpts from the book this results in, the Encyclopedia Galactica - mocked in The Hitch-Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy in the 1970s, and a precursor of the internet.

It's influence on science-fiction is also evident. Back in my academic days last millennia, I wrote for the journal Foundation. I assume Han Solo being Corellian is a nod to the Korellians here, and Hardin in Doctor Who story The Leisure Hive a nod to the character in the book. Maybe the Doctor Who story Terminus owes a debt to this as well.

Then there are things that seem so much of an ancient past: the smoking of cigars (I initially read "a long cigar of Vegan tobacco" (p. 47) as meaning it was free of animal producrs), the news printed on paper, the merchant who offers tech-fashions to women but tech-weapons to men. A key element in the story is different groups' access and understanding of nuclear energy - "atomic power can be conquered only by more atomic power" (p. 164) - which feels very 1951, when such energy was a pretty neat idea.

If we're not told how psychohistory actually works, Asimov at least places limits on the super-science to keep things dramatically interesting. Seldon predicts a series of crises, and those that follow him are left to guess how to meet such challenges without making the impending Dark Ages worse.

"I quite understand that psychohistory is a statistical science and cannot predict the future of a single man with any accuracy." (p. 21)

"Because even Seldon's advanced psychology was limited. It could not handle too many independent variables. He couldn't work with individuals over any length of time; any more than you could apply the kinetic theory of gases to single molecule. He worked with mobs, populations of whole planets, and only blind mobs who do not possess foreknowledge of the results of their own actions." (p. 97)It's also all told in short, punchy chapters and sections - one chapter is barely three paragraphs long. We often jump forward years, and having to catch up on the monumental events we just skipped. There's an awesome scale and a sense of playing an active part in making sense of the bigger picture behind all these fragments.

Asimov occasionally makes sly comment on the politics presented:

"Korrell is that frequent phenomenon in history: the republic whose ruler has every attribute of the absolute monarch but the name. It therefore enjoyed the usual despotism unrestrained even by those two moderating influences in the legitimate monarchies: regal 'honour' and court etiquette." (p. 172)But in large part the pleasure comes from smart, compassionate men (they're all men) who use that intelligence and compassion to avoid conflict and stick to Seldon's plan. It's an alluring idea, but I can't help feeling that it would be a more rewarding read if it didn't all go as predicted. It's a book that couldn't have been written after the Bay of Pigs or Watergate.

In fact, in 2002 David Langford spelled out a rather fine conjecture about Foundation influencing a real movement that has shaped so much of the 21st century.

I'm now keen to read Alex Nevala-Lee's new book Astounding: John W Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A Heinlein, L Ron Hubbard and the Golden Age of Science-Fiction (Dey Street Books, 2018).

Published on November 20, 2018 13:06

November 14, 2018

Doctor Who Magazine #532

The super new issue of Doctor Who Magazine is out tomorrow - but reaching subscribers already. Among the treats inside, I've interviewed costume designer Ray Holman about the current "TARDIS team", with tips for cosplaying the Doctor, Ryan, Yaz and Graham.

The super new issue of Doctor Who Magazine is out tomorrow - but reaching subscribers already. Among the treats inside, I've interviewed costume designer Ray Holman about the current "TARDIS team", with tips for cosplaying the Doctor, Ryan, Yaz and Graham.As Ray and I were talking on the phone about the practicalties of the Doctor's new costume, Lady Vader (or "Pting" as her brother now calls her) took it all to heart. Soon she was insisting I zip up her favourite princess outfit which she wore with owl backpack and wellington boots. The interview over, I then had to take her out for adventures, splashing in puddles while looking 100%.

Time for an adventure...

Time for an adventure...

Published on November 14, 2018 06:10

November 13, 2018

The Sky at Night Book of the Moon, by Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock

BBC Books (who, I should declare, publish stuff by me) sent me this fun new volume from TV's Dr Maggie, which she herself describes as, "a voyage that has explored the physical, mental and emotional impact of the Moon on all of us."

BBC Books (who, I should declare, publish stuff by me) sent me this fun new volume from TV's Dr Maggie, which she herself describes as, "a voyage that has explored the physical, mental and emotional impact of the Moon on all of us."Much of the collected material is familiar from her BBC Two documentary, Do We Really Need the Moon?, detailing the history of our relationship with the Moon and how it benefits us. For example, its relatively large size stabilises Earth's orbit; it has slowed the spin of the Earth to the 24-hour cycle we're used to; the tides it creates may have played an essential role in the development of the very first life.

There's a lot more science, too - including updates on the latest efforts to return humans to the Moon - but also a selection of favourite Moon-related poetry, art and stories, and an exploration of the oldest Moon-related artefacts. I was captivated by the entry on "En-hedu-ana: Astronomer Princess of the Moon Goodess (c. 2354), who is,

"the first female name recorded in history and the first poet known by name too." (p. 65)On the next page, we're told that at least one of the numerous depictions labelled as En-hedu-ana shows her with a "substantial beard."

I read the book as research for a potential project, and now I have another one...

Me on Apollo by Fitch, Baker and CollinsMe on Ad Astra, An Illustrated Guide to Leaving the Planet by Dallas CampbellMe on Moonglow by Michael ChabonMe on #Cosmonauts and #OtherWorldsMe on Moondust by Andrew Smith

Published on November 13, 2018 08:15

November 7, 2018

Worthing Wormhole and Gallifrey

I will be a guest at Worthing Wormhole this Saturday, signing copies of Doctor Who: The Women Who Lived with co-author Christel Dee.

I will be a guest at Worthing Wormhole this Saturday, signing copies of Doctor Who: The Women Who Lived with co-author Christel Dee.Christel and I have also been announced as guests at Gallifrey One in Los Angeles in February. (By exciting coincidence, I first met Christel the last time I was at Gallifrey, in 2016.)

And here's a picture of my tired old head this morning at the BBC...

Published on November 07, 2018 07:25

November 6, 2018

Searching for the Lost Tombs of Egypt, by Chris Naunton

I first met Egyptologist Chris Naunton around the time he was working on his BBC Four documentary, The Man Who Discovered Egypt, which included the Dr as a shrewd talking head. Chris then advised me on the Egypt bits in the first chapter of The Science of Doctor Who and a timeline in Whographica - he wrote his own account of working out when exactly the Daleks invaded Egypt.

I first met Egyptologist Chris Naunton around the time he was working on his BBC Four documentary, The Man Who Discovered Egypt, which included the Dr as a shrewd talking head. Chris then advised me on the Egypt bits in the first chapter of The Science of Doctor Who and a timeline in Whographica - he wrote his own account of working out when exactly the Daleks invaded Egypt.When the esteemed published Thames & Hudson approached Chris about writing a book on Tutankhamun, he argued instead for a book answering the question he and fellow egyptologists get asked all the time - what is there still to find?

The result is a fascinating, comprehensive and carefully weighed assessment of the chances of tracking down some of the most coveted tombs in history, those of: the great architect Imhotep (the one whose name was co-opted by the horror movies); Amenhotep I; Nefertiti and the other Amarna royals related to Tutankhamun; Herihor whose tomb, it has been claimed, would make "Tutankhamun look like Woolworths"; the pharaohs of the much disputed Third Intermediate Period; Alexander the Great; and Cleopatra.

It's a little like Richard Molesworth's book, Wiped!, which details the loss and recovery of episodes of Doctor Who - at times tantalising, fascinating and utterly frustrating. Along the way, Chris supplies plenty of fascinating history - of ancient Egypt and of modern archaeologists, not all of whom come out of it very well. He is good at putting the claims of some enthusiasts and attempting to weight them against evidence fairly.

There's plenty that I didn't know - Alexander the Great had a sister called Cleopatra - and I particularly like a quotation from Howard Carter's 1917 report, "A tomb prepared for Queen Hatshepsut and other recent discoveries in Thebes", in which he feels the need to accent and italicise the exotic, foreign word "débris".

Published on November 06, 2018 08:48

November 5, 2018

Antimatter in buckets

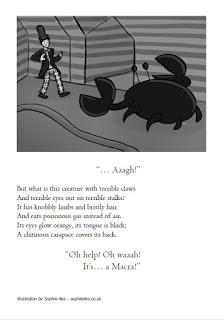

Radio Times spoke to me and science writer Giles Sparrow about antimatter and its potential use in powering spaceships as seen in last night's episode of Doctor Who, The Tsuranga Conundrum.

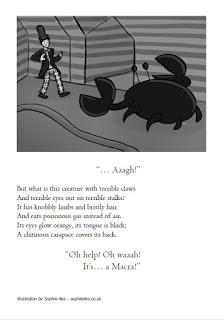

Radio Times spoke to me and science writer Giles Sparrow about antimatter and its potential use in powering spaceships as seen in last night's episode of Doctor Who, The Tsuranga Conundrum.I really enjoyed the episode, not least because the monster causing all the havoc could well have been based on my two year-old Lady Vader causing havoc. She's not watching the series, but the Lord of Chaos is. He found last night's one very frightening, but not nearly as terrifying as the spiders last week - which he's attempted to watch twice and given up on both times.

Published on November 05, 2018 04:25

October 20, 2018

The Bird's Nest, by Shirley Jackson

Shirley Jackson's 1954 novel The Bird's Nest is extraordinary. Elizabeth Richmond works in a museum, the wall beside her desk removed during renovation, so that she sits beside an open chasm. If that were not sufficiently unsettling, she's getting anonymous hate mail. And then there are her Aunt Morgen's accusations of her wanderings in the night...

Shirley Jackson's 1954 novel The Bird's Nest is extraordinary. Elizabeth Richmond works in a museum, the wall beside her desk removed during renovation, so that she sits beside an open chasm. If that were not sufficiently unsettling, she's getting anonymous hate mail. And then there are her Aunt Morgen's accusations of her wanderings in the night...The basis for the malady suffered by Elizabeth - Lizzie, Beth, Betsy and Bess - is spelt out on pp. 57-8, when Jackson quotes directly from Morton Prince's The Dissociation of a Personality (1905):

"Cases of this kind are commonly known as 'double' or 'multiple personality', according to the number of persons represented, but a more correct term is disintegrated personality, for each secondary personality is a part of a normal whole self. No one secondary personality preserves the whole physical life of the individual. The synthesis of the original consciousness known as as the personal ego is broken up, so to speak, and shorn of some of its memories, perceptions, acquisitions, or modes of reaction to the environment. The conscious states that still persist, synthesized among themselves, form a new personality capable of independent activity. This second personality may alternate with the original undisintegrated personality from time to time. By a breaking up of the original undisintegrated personality at different moments along different lines of cleavage, there may be formed several different secondary personalities, which may take turns with one another."I'm writing an article about the book, and Jackson, and the psychoanalyses of her time. More to follow...

Me on Shirley Jackson's We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962)Me on Jackson's Dark Tales

Published on October 20, 2018 13:17

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers

Simon Guerrier isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.