Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 53

June 10, 2019

A Wizard of Earthsea, by Ursula K Le Guin

To the horror of many wise friends, I've started this famous book several times but never finished it until now. It charts the early life of Ged - or Sparrowhawk, or Duny - who, while training as a wizard, unleashes a sinister shadow-thing that then pursues him. As Ged hops from island to island round Earthsea to escape his creation, the monster comes ever on.

To the horror of many wise friends, I've started this famous book several times but never finished it until now. It charts the early life of Ged - or Sparrowhawk, or Duny - who, while training as a wizard, unleashes a sinister shadow-thing that then pursues him. As Ged hops from island to island round Earthsea to escape his creation, the monster comes ever on.The first chapter, in which young dorky Duny first learns some magic and then saves his village from invaders, is brilliant but his subsequent mentoring by stoic old wizard Ogion and squabbles with other pupils at wizard school never quite connected with me before. Having read the whole book, that's all cast in different light. Sneering fellow student Jasper isn't really Ged's worst enemy - it's his own impatience and pride. He must learn subtler arts than spells: using historical research to best a dragon, and not using magic to turn the tables on the shadow.

As with the Le Guin I already know (The Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness) there's lots on the way words shape our reality and have their own innate power. Knowing a person or thing's secret, true name gives you power over that person or thing, a simple basis on which to build a complex framework of magic and a richly realised society. Ged's best friendship is defined by them condfiding real names, and when he learns the true name of a young woman it immediately suggests a strong link between them. That distinction between public persona and private, true self seems all the more pertinent today with the lives we live online and IRL.

I didn't realise the "werelights" conjured by Peter Grant in the Rivers of London books came from here, and assume Le Guin also inspired the name of my friend's band:

“As a boy, Ogion like all boys had thought it would be a very pleasant game to take by art-magic whatever shape one liked, man or beast, tree or cloud, and so to play at a thousand beings. But as a wizard he had learned the price of the game, which is the peril of losing one's self, playing away the truth. The longer a man stays in a form not his own, the greater this peril. Every prentice-sorcerer learns the tale of the wizard Bordger of Way, who delighted in taking bear's shape, and did so more and more often until the bear grew in him and the man died away, and he became a bear, and killed his own little son in the forests, and was hunted down and slain. And no one knows how many of the dolphins that leap in the waters of the Inmost Sea were men once, wise men, who forgot their wisdom and their name in the joy of the restless sea.” (pp. 117-8)I've ploughed straight on into the second book, The Tombs of Atuan, which opens with a scene I think more haunting than anything in the first: a man chiding his wife for doting on the young daughter they know will shortly be taken from them, the man already grieving.

Published on June 10, 2019 04:23

June 3, 2019

TV Years: Classic Children's Television

The new issue of TV Years magazine, from the makers of TV Choice, is devoted to classic children's television. I've written a feature on Play School (1964-88) and interviewed creator and first producer Joy Whitby and presenters Carol Chell and Carol Leader.

The new issue of TV Years magazine, from the makers of TV Choice, is devoted to classic children's television. I've written a feature on Play School (1964-88) and interviewed creator and first producer Joy Whitby and presenters Carol Chell and Carol Leader.

Published on June 03, 2019 01:43

June 2, 2019

La Belle Sauvage, by Philip Pullman

Last week, a long car journey through half-term traffic was made infinitely less taxing by Michael Sheen's reading of the first volume of The Book of Dust.

Last week, a long car journey through half-term traffic was made infinitely less taxing by Michael Sheen's reading of the first volume of The Book of Dust.Set within the same fantastic universe as the His Dark Materials trilogy, the heroine of that story - Lyra - is here a new-born baby. She's being looked after by some nice nuns in a priory, and across the bridge from them is a pub run by the parents of 11 year-old Malcolm Polstead. Mal is a hard-working, concientious nerd, with a love for new words and bits of gadget such as screws that only turn one way. Chatting to pub customers, eavesdropping and watching, he starts to spy a conspiracy building round the baby...

Just as with His Dark Materials, Pullman conjures a vivid, rich world so near and yet so far from our own. Malcolm's borrowed books include A Brief History of Time but he's also accompanied by his shape-changing demon, Asta. The etiquette of demons - that it's rude to touch someone else's demon; that demons can change shape until their human reaches adulthood, when they settle in one form - is all subtely conveyed: a world of strange wonders that yet feels real.

This world is populated with memorable characters, and Pullman is good at making us warm to the nice ones and bristle at the villains. For all the villains are hissable, there are plenty of characters we're not quite sure of, or good people we can't quite trust. Kudos to Michael Sheen for expertly voicing such an enormous cast.

The book is in two parts, and the first is easily the strongest as Malcolm uncovers the plot against the baby and encounters various sinister organisations linked to the Church. I found the chapter where one group addresses his school utterly terrifying, children encouraged to turn on their teachers and parents and friends.

"Malcolm's headmaster Mr Willis was still away on Monday, and on Tuesday Mr Hawkins the deputy head announced that Mr Willis wouldn't be coming back, and that he would be in charge himself from then on. There was an intake of breath from the pupils. They all knew the reason: Mr Willis had defied the League of St Alexander, and now he was being punished. It gave the badge-wearers a giddy sense of power. By themselves they had unseated the authority of a headmaster. No teacher was safe now. Malcolm watched the faces of the staff members as Mr Hawkins made the announcement: Mr Savery put his head in his hands, Miss Davis bit her lip, Mr Croker the woodwork teacher looked angry. Some of the others gave little triumphant smiles; most were expressionless." (p. `147)If the Church are the baddies, there are plenty of good and kind Christians, such as the nuns in charge of Lyra. Yes, the politics are a little laid on with a trowel - but then that's true of our own world at the moment.

When we stopped for lunch, I asked Lord Chaos how much he understood what was going on in this sequence - and he did, and told me he wouldn't have worn a badge. But it also didn't resonate with him as much as it did with me. But he was on the edge of his seat for the end of part one, and the thrilling things happening in the midst of a huge flood.

Part two is fine and full of strange, arresting events but lacks the thrill of the first half. It details the journey made by Mal's boat - the Belle Sauvage of the title - and stop-offs along the way. After all the conspiracy and intrigue of the first part, I didn't really feel it advanced the plot. There's plenty of excitement, especially in the villainous Bonneville, and the prolonged chase affects the relationship between the protagonists, but I got to the end feeling it hadn't changed much else. That's a shame given the strength of the opening.

The second book, The Secret Commonwealth, is published later this year and set 20 years after the events here - and after those of His Dark Materials. I'm very much looking forward to it, and to the BBC's adaptation of His Dark Materials. You might also like this recent chat between Samira Ahmed and Philip Pullman on how he found his voice.

Published on June 02, 2019 11:50

May 31, 2019

Doctor Who Magazine 539

The new issue of Doctor Who Magazine marks my debut as compiler of the "Time Team" - the regular feature in which a group of 20-something fans watch old episodes of the series with a connecting them.

The new issue of Doctor Who Magazine marks my debut as compiler of the "Time Team" - the regular feature in which a group of 20-something fans watch old episodes of the series with a connecting them. This time, the theme is "Is Doctor Who a kids' show?" - something I've been thinking about a lot over the last year as I've watched my son and his school friends get caught up in the adventures of Jodie Whittaker's Doctor. So, I set Beth, Christel and Luke watching The Web Planet (1965), Full Circle part one (1980) and The Caretaker (2014). We were also joined by Ariana - who has never seen an episode of Doctor Who before.

Here's my interview with Andrew Smith, writer of Full Circle.

Published on May 31, 2019 06:02

May 25, 2019

Seurat and the Science of Painting, by William Innes Homer

Seurat and the

Seurat and the Science of Painting

by William Innes Homer

(1964)At the turn of the 20th century, work by Max Planck on the odd properties of light led to a revolution in physics called quantum mechanics. But a generation before him, artists showed an understanding of light no less revolutionary.

I've been interested in the overlap of science and art for a long time, as I posted here after a visit to the National Gallery's 2007 exhibition, "Manet to Picasso". Some of that thinking was rekindled by reading The Pinball Effect last month, which cited the influence on Seurat of the chemist Michel Chevreul. An endnote directed me to Seurat and the Science of Painting, published in 1964.

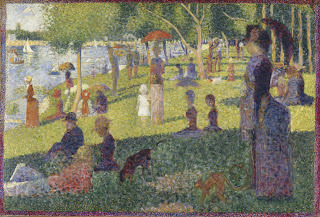

Sifting through Seurat's surviving papers, accounts of his contemporaries and other sources, Homer pieces together the influences on two particularly famous paintings: "Une Baignade, Asnières" (usually translated in the plural as "Bathers at Asnières") from 1884, and "Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte" ("A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jette"), painted 1884-86.

"Une Baignade, Asnières" by Seurat (1884)

"Une Baignade, Asnières" by Seurat (1884) "Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte"

"Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte" by Seurat (1884-86)The key idea is that Seurat followed the colour theories of Chevreul and Rood, among others. Those theories weren't exactly new. Chevreul had experimented with colour while director of the Gobelins tapestry works in Paris, publishing his conclusions in 1839 - 20 years before Seurat was born. Nor were he and the Impressionists the first to use these theories in painting. Homer shows that Delacroix was well ahead of them; he died in 1863, when Seurat was not yet four.

The theories are fairly simple to grasp. In trying to make dyes brighter and more arresting, Chevreul found that it was less effective to mix colours physically than to place threads or fabrics dyed in contrasting colours next to one another. From a distance, our eyes do the mixing optically but to more dramatic effect. The contrasts shimmer and fizz.

Homer provides a range of different diagrams explaining colour contrasts and harmonies, as understood by different theorists. Take the three primary colours: yellow, red and blue (or, in some cases, blue-violet). The direct contrast to yellow is the mix of the other two, i.e. purple. Red then contrasts with green, and blue (or blue-violet) with orange. But that's just the start. Homer then details how the theories incorporate gradations of tone and hue. There are a lot of diagrams.

On one spread, radiating spokes are presented three times to show how the same basic idea passed from person to person - the last of them Seurat. There are also circles, grids, stars and triangles to demonstrate connections of colour, the spokes labelled variously in English or French. It's extraordinary that these diagrams explaining colour in such meticulous detail are all in black and white. We must imagine the connections. The colour plates offer just four small images, each a detail of one of the paintings under discussion. The paintings themselves are also shown in black and white.

Diagrams in Seurat and the Science of Painting (1)

Diagrams in Seurat and the Science of Painting (1)

Diagram in Seurat and the Science of Painting (2)

Diagram in Seurat and the Science of Painting (2)The result is that this academic study was all the more hard-going for this reader of limited brain. Homer goes into great detail but (I felt) repeats himself, giving ever more examples of the same basic idea. There's also little on what other science influenced these painters: the invention of photography, the development of new kinds of paint. And I think purists might question how "scientific" some of these theories really are - surely some of the conclusions are more a matter of taste.

But for the most part this is dizzyingly absorbing. The irony is that Seurat's work isn't realistic, yet that stylisation is based on direct observation, recording the strange, real effects of light - such as the colouring of shadows. The brushwork is surely also on to something ahead of its time. Previous generations of painters used delicate strokes to hide their artistry but Seurat favoured spots and strokes, discernable dabs of individual colour.

It is light conveyed in discrete units, packets - quanta.

Published on May 25, 2019 09:11

May 21, 2019

Living with a black hole

The June 2019 issue of medical journal the Lancet Psychiatry includes my review of the film Out of Blue.

The June 2019 issue of medical journal the Lancet Psychiatry includes my review of the film Out of Blue."Detective Mike Hoolihan (Patricia Clarkson) has always felt safe working in homicide. However, the shocking death of astronomer Jennifer Rockwell (Mamie Gummer) poses difficult questions. While Hoolihan pursues three murder suspects, she also finds herself increasingly affected by the dead woman's work on black holes and unsettling conversations about quantum mechanics and Schrödinger's put-upon cat. She comes to doubt herself, as do we..."

Published on May 21, 2019 01:08

May 16, 2019

Lies Sleeping, by Ben Aaronovitch

A lot of water has flowed under the bridge since my holiday in Salonica in January 2011 where I read my friend Ben Aaronovitch's Rivers of London, but I recently listened to the audio version of that first instalment and it all came flooding back. Peter Grant is a cop who can do magic, investigating weird shit in London...

A lot of water has flowed under the bridge since my holiday in Salonica in January 2011 where I read my friend Ben Aaronovitch's Rivers of London, but I recently listened to the audio version of that first instalment and it all came flooding back. Peter Grant is a cop who can do magic, investigating weird shit in London...Lies Sleeping is the seventh novel in the series - there's also a novella and a spin-off comic series. Here, there's the usual mix of streetwise wit and procedural detail, grounding the investigation in real life and science and history. Ben's gift is to make it feel authentic.

"... me and Guleed ended up in a corridor at UCH guarding [a suspect]'s hospital room, along with a reassuringly solid member of Protection Command in full ballistic armour and armed with an H&K MP5 machine gun. Her name was Lucy and she had three children under the age of five.There a big, diverse cast of characters, and many now feel like friends. Then there's eye-popping action stuff, some of it read with your heart in your mouth.

'Compared to them,' she told us, 'I don't find this job stressful at all.'

You use Protection Command people for this kind of job because unlike SCO19 they're trained to do guard duty. You want a certain kind of personality who can stand around in the rain for eight hours and still be awake enough to shoot someone in the central body mass at a moment's notice." (pp. 14-15).

It's obviously difficult to write about this book without spoiling earlier instalments, but it's been a real pleasure to bathe in this world again. I especially like how it's a satisfying, standalone story in its own right, but full of stuff pushing forward so that nothing can be the same.

The Waterstones edition includes a bonus story, "Favourite Uncle", told from the perspective of Peter's 15 year-old trainee, Abigail and is a nice bit of Christmas whimsy, never quite going where you'd expect.

Published on May 16, 2019 05:11

May 9, 2019

The Science of Storytelling, by Will Storr

I'm reviewing this new book elsewhere so can't go into too much detail here, but this has been a fascinating read. Storr uses lots of recent psychological and neuroscientific studies to explain how our brains respond to stories and what we can do to make those stories more effective. There's everything from devising character and plotting to the construction of sentences.

I'm reviewing this new book elsewhere so can't go into too much detail here, but this has been a fascinating read. Storr uses lots of recent psychological and neuroscientific studies to explain how our brains respond to stories and what we can do to make those stories more effective. There's everything from devising character and plotting to the construction of sentences.My own criticism is the sometimes glib, even crass, tone. He illustrates a point about how people justify their own bad behaviour with a real-life example of a Nazi who killed children. But the actual example is so visceral and vivid that it's haunted me for days.

Published on May 09, 2019 09:11

May 3, 2019

Doctor Who Magazine 538

Robert Allsopp's first work on Doctor Who was to make the question mark handle for Sylvester McCoy's umbrella in 1987. He's worked on the series on-and-off ever since - his workshop supplied the mechanical version of the Dalek creature hugging poor Charlotte Ritchie in this year's episode, Resolution.

Robert Allsopp's first work on Doctor Who was to make the question mark handle for Sylvester McCoy's umbrella in 1987. He's worked on the series on-and-off ever since - his workshop supplied the mechanical version of the Dalek creature hugging poor Charlotte Ritchie in this year's episode, Resolution.I've interviewed Rob about his career for the new issue of Doctor Who Magazine - out now.

Published on May 03, 2019 10:06

May 2, 2019

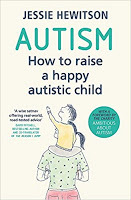

Autism, by Jessie Hewitson

I learned about this book in December when the author was a guest on the (brilliant) 1800 Seconds on Autism podcast, and was particularly struck by the subheading: "How to raise a happy autistic child."

I learned about this book in December when the author was a guest on the (brilliant) 1800 Seconds on Autism podcast, and was particularly struck by the subheading: "How to raise a happy autistic child."It's full of useful advice, explaining the myriad ways autism can manifest and the torturous process of fighting for support. Hewitson has talked to a lot of experts, lots of similarly struggling parents and - most importantly - lots of autistic people themselves. As well as the practical tips and details of where to turn to for help, the book underlines that this can be very difficult but not impossible. You are not alone.

If there's one message here it's to be proactive and to fight on. Hewitson says she hopes the chapter on support in education will "empower parents to know some of their rights and help people with less money and privilege to navigate this complex system."

"Some local authorities are good, but many of you who have already embarked on the quest to get your council to stump up will know it is those who fight hardest and play the LA at their own game who get most support. The poorer kids, or the kids who don't have the capacity for the fight, are gettinng less support or, increasingly none. Meanwhile, the children of the middle-classes are getting provision because their parents can understand and can play or afford to play the system." (pp. 208-9)It's not just knowing how to play the system, it's also having the means. Many of the therapies suggested here cost money and also take time. You need time to battle the system and go to all the appointments. You need time to chase the things promised that haven't been done. Then, after all that battling, you're offered a course - or more than one - at short notice, an hour a week for however many weeks that effectively writes off half a day when you're already struggling to stay on top of things. Being freelance has helped me be flexible but all that time eaten up has its effect, from the constant missing of deadlines to never earning enough.

So I read Hewitson's accounts of various private therapy sessions with envy. But we battle ever on.

Published on May 02, 2019 01:11

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers

Simon Guerrier isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.