Simon Guerrier's Blog, page 60

April 13, 2018

Doctor Who and the Day of the Doctor, by Steven Moffat

A long time ago when I was not so broken and old, I made a point of finishing every book begun, enjoyable, insightful or not. These days, amid the noise of work and childcare, I'll try and give a book 100 pages and then dump it if it's not delivering.

A long time ago when I was not so broken and old, I made a point of finishing every book begun, enjoyable, insightful or not. These days, amid the noise of work and childcare, I'll try and give a book 100 pages and then dump it if it's not delivering.Oh dear, did Simon not get on with the new novelisation of 2013 Doctor Who episode The Day of the Doctor, written by his friend Steven Moffat? And to the extent of then writing an angry post about it, to be read by whole single figures of people? Or is this merely an attention-grabbing prelude?

I got to page 136 of Ann Radcliffe's 1794 gothic novel The Mysteries of Udulpho -

Hah, thought so.

- and things were just starting to occur. After pages and pages of picturesque travel through Gascony, our heroine Emily is orphaned and forced to live with a ghastly aunt, surrounded by her aunt's ghastly friends. They engineer malicious gossip about a nice young man Emily has taken a shine to, and her prospects do not look good...

But the plot and I were making such slow progress, the prospect of another 596 pages was hardly a thrill. And then the five new novelisations of TV Doctor Who stories arrived. I selected Steven Moffat's one at random to read on a trip into town.

And blimey. It's frenetic. I tore through it in very few sittings - which feels all the more remarkable because the book is packed.

Steven retells the events of the TV episode from the point of view of the Doctor, which is immediately tricky because it all happens out of chronological order, and to several incarnations of the Doctor at once. So we start with chapter 8, then chapter 11 and then chapter 1. Between each chapter, a narrator comments on the reliability of the sources - apparently in real time as we're reading.

"(By the way, these pages should be appearing in italics . If not, just give three light taps on any verb, and the page will reboot. And if you don't like any aspects of my prose style, give the book a good shake. That should help you work of your irritation.)"It's all very clever, or infuriating or fun, depending on your tastes. Steven packs his book with metatextual jokes - references to Doctor Who books that haven't been written yet, teasing us to look for a chapter that's gone missing, and the idea that the narrator can see us as we're reading. One page is apprently written in our own handwriting.

Steven Moffat, Doctor Who - The Day of the Doctor (2018), p. 3.

While the narrative largely follows the events - and dialogue - of the TV episode, Steven has added all sorts of stuff. Each incarnation of the Doctor gets a heroic moment and to go for tea. There are appearances by River Song (in the bath with the Tenth Doctor), the Brigadier and Sarah Jane Smith, and even the Dr Who movies starring Peter Cushing - including what the Doctor thinks of them.

"He loves them. He loaned Peter Cushing a waistcoat for the second one, they were great friends. Though, we only realised that when Cushing started showing up in movies made long after his death."Again, your delight or dismay at this sort of thing may vary, but I found the Brigadier and Sarah bits quite moving - not least because the much-loved actors who played them died in 2011 and so couldn't be part of the TV version. The TV version did achieve a coup of a cameo, and the appearance by an engimatic curator of the National Gallery still provides goosebumps in print (though sadly doesn't confirm my own evidence-based theory that the National Gallery is, in fact, a TARDIS).

Ibid., p. 144.

But really that's all distraction from the crux of the story, in which the Doctor faces, again and again, the worst moment in his long life - when he must destroy his own people to save the universe as a whole. This, its effect on him, and the intervention by his friend Clara, is what makes this particular adventure so sad and yet joyous, so effective and even profound.

Steven goes beyond the TV version, which rests on the Doctor restating the promise implicit in his name, that he endeavours never to be cruel or cowardly. The book turns out to be a more fundamental exploration of that promise, and of exactly who the Doctor thinks they are.

It ends on a battlefield in the future, with the Doctor in conversation with two women from her past, quoting words from a TV episode that, long ago, promised the adventures would never end. So this novelisation of old Doctor Who - in more ways than one - is ultimately a witty / optimistic / clever-clever look to the future.

Published on April 13, 2018 02:13

April 12, 2018

Isle of Dogs

In January, I took the Lord of Chaos to see the Pixar film Coco at the cinema. It held him transfixed, but I'd already given my heart to a trailer before it started. As always, there had been the cloyingly awful previews of films aimed at children and their poor parents - and then an astonished gasp from those sitting round me in the darkness. And from me as well.

In January, I took the Lord of Chaos to see the Pixar film Coco at the cinema. It held him transfixed, but I'd already given my heart to a trailer before it started. As always, there had been the cloyingly awful previews of films aimed at children and their poor parents - and then an astonished gasp from those sitting round me in the darkness. And from me as well.'What the bloody hell was that'? people asked. 'Can we go see that?' I pleaded to my son.

Finally, this morning, we got to see Isle of Dogs, and I sat in stupefied wonder. It looks and sounds and feels amazing - a tale of a small and wounded boy doggedly searching for his lost dog, in a desolate and often cruel landscape. It had just the right mix of tension and jokes to keep his Lordship entertained, too - he enthused to his mum about it later.

I was getting a strong Kurosawa vibe already when the brilliant soundtrack (mostly by Alexandre Desplat) then included Hayasaka's "Kanbei & Katsushiro - Kikuchiyo's Mambo" from The Seven Samurai.

It could do with better, more prominent roles for female characters, and I'd have cut at least one of the couples pairing up at the end - it's all a bit male and straight and, looking at the cast, white. But it's an astounding film, even more so to see it on the big screen with that sound. It's been a long time since I've left a cinema so elated.

Published on April 12, 2018 14:26

April 6, 2018

Bernice Summerfield - in Time

The Time Ladies and Big Finish have announced a thrillingly thrilling short story competition for the Bernice Summerfield range.

The Time Ladies and Big Finish have announced a thrillingly thrilling short story competition for the Bernice Summerfield range.The winning story will be published in Bernice Summerfield: in Time , a new anthology edited by Xanna Eve Chown and to be published in December - part of the glut of fun stuff to mark 20 years of Big Finish producing Benny's adventures. The anthology will include a short story by me (which I haven't started writing yet), related to my forthcoming audio play, Braxiatel in Love.

A long time ago, I was in charge of judging Benny short story competitions, and a Doctor Who one, too. Here's some general feedback from the 2006-7 Doctor Who short story competition that might be of use to anyone entering this new contest. Good luck!

Published on April 06, 2018 11:26

April 4, 2018

Seven films watched on two planes

Bladerunner 2049

This is not a film designed to be watched on a small, square screen on a plane, the naked bits pixellated and the swearing dubbed. But it still looks amazing, a credible, bleak future of light and texture and history. There's considerable effort to continue on from the original film without matching it slavishly, but sadly this new instalment lacks the quirky humour.

It's treatment of women is also a problem. True, the "pleasure model" Replicants in the first film were all women, and I think this one's trying to make a point about the way women are packaged and sold - while also showing us lots of bare boobs (if I read my pixellated screen right). Given we know that Ryan Reynolds' K is a Replicant, perhaps it would have worked better for him, in his darkest hour, to see a sexy advert not for a Replicant that reminds him of someone else, but for one that looks just like him.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

This film about rape and murder and suicide and domestic violence and racism and torture was, helpfully, edited for content, so what seems to have been an almost constant barrage of swearing was dubbed out. For the first ten minutes or so, I thought I was going to have to turn the thing off it was so ridiculous, and then it became hypnotic.

It's a gripping film, that starts with a really tough premise and then keeps coming at you from left field. Part of the thrill of it is in having two lead characters who seem completely unchained, liable to do just about anything.

A final scene seems a bit tacked on - we watch a car drive away past the titular billboards and the film could have ended there, but we then cut to the interior of the car for some last exposition. I'm also really uncomfortable about the sort-of redemption of the racist cop who admits to having tortured a black suspect - an act that is almost a joke among the white people of the community. Yes, he suffers in the course of events, and endeavours to be a better cop, but there's no sense that either he or the community really face up to what he's done.

Baby Driver

This typically stylish caper from Edgar Wright is great fun, though obviously overshadowed by Kevin Spacey's later fall from grace. I really liked the final sequence where Baby must face the consequences of his actions, but also felt love interest Debora was too accepting of all he had done. Grosse Point Blank had Debbie recoil in horror from her prospective boyfriend's criminal life. Not enough of a price is paid here, I thought.

Arthur: Legend of the Sword

Guy Ritchie's daft take on the Arthurian legend has baby Arthur brought up in a brothel in London, where he grows into a right geezer with a common touch before learning he's the king. The title would be more accurately Arthur: Ledge. The film's one redeeming feature is that the London shown is clearly the one built and then abandoned by the Romans, the cheeky cockneys having taken charge of the former temples and circus. Just that panning shot made it worth it.

Goodbye, Christopher Robin

Since I'd read Christoper Robin's own memoir, The Enchanted Place, I knew that the opening premise of this film wasn't right - the boy who played with Winnie the Pooh didn't grow up to die in the Second World War. Yes, the film reveals later on that he survived, but that opening meant I watched this wondering what else had been moulded for dramatic effect. Would Olive, the nanny, really have spoken her mind to the boy's parents? Have the writers been fair to Daphne, the boy's mum?

Even so, that didn't distract too much from the moving story, of a shell-shocked AA Milne and EH Shephard struggling to return to their light-comic lives from before the war. A son and a move to the country both fail to quiet Milne's demons, at least at first. Then a bond builds between father and son that Milne works into his Winnie the Pooh stories - which were hugely successful by any measure, except the one that really mattered. Christopher Robin's enchanted childhood became a nightmare adolescence.

It's a compelling, horrifying story, that the books we so adored caused such misery for the boy in them. I find myself reviewing how much I put my own children in the limelight, on social media or in anything related to my work.

The Dark Tower

This is a humourless action movie about a troubled teenager who is really the special psychic who can either save or destroy the whole universe. The gunslinger he teams up with is played by Idris Elba, who adds a touch of class and is the best thing about the film - but it's a shame he couldn't be smarter or funnier. As the two journey through different realms together, they fight various bad guys and monsters, while the main villain does horrible things to anyone close to them. It's downright nasty: the bad guy killing the boy's mum is oddly unaffecting beyond the immediate shock. I kept hoping it would do something more interesting.

Spider-Man: Homecoming

I'd seen this fun adventure before, and again was struck by its wit, its heart, the villain we can totally sympathise with and the brilliant moment where Spider-Man inadvertently turns up at his front door. A lot of superhero films are about exceedingly strong and well-equipped people beating up villains who often seem less well-off in powers and technology. This new version of Spider-Man works precisely because he's a little guy - young and green and apparently out on his own.

This is not a film designed to be watched on a small, square screen on a plane, the naked bits pixellated and the swearing dubbed. But it still looks amazing, a credible, bleak future of light and texture and history. There's considerable effort to continue on from the original film without matching it slavishly, but sadly this new instalment lacks the quirky humour.

It's treatment of women is also a problem. True, the "pleasure model" Replicants in the first film were all women, and I think this one's trying to make a point about the way women are packaged and sold - while also showing us lots of bare boobs (if I read my pixellated screen right). Given we know that Ryan Reynolds' K is a Replicant, perhaps it would have worked better for him, in his darkest hour, to see a sexy advert not for a Replicant that reminds him of someone else, but for one that looks just like him.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

This film about rape and murder and suicide and domestic violence and racism and torture was, helpfully, edited for content, so what seems to have been an almost constant barrage of swearing was dubbed out. For the first ten minutes or so, I thought I was going to have to turn the thing off it was so ridiculous, and then it became hypnotic.

It's a gripping film, that starts with a really tough premise and then keeps coming at you from left field. Part of the thrill of it is in having two lead characters who seem completely unchained, liable to do just about anything.

A final scene seems a bit tacked on - we watch a car drive away past the titular billboards and the film could have ended there, but we then cut to the interior of the car for some last exposition. I'm also really uncomfortable about the sort-of redemption of the racist cop who admits to having tortured a black suspect - an act that is almost a joke among the white people of the community. Yes, he suffers in the course of events, and endeavours to be a better cop, but there's no sense that either he or the community really face up to what he's done.

Baby Driver

This typically stylish caper from Edgar Wright is great fun, though obviously overshadowed by Kevin Spacey's later fall from grace. I really liked the final sequence where Baby must face the consequences of his actions, but also felt love interest Debora was too accepting of all he had done. Grosse Point Blank had Debbie recoil in horror from her prospective boyfriend's criminal life. Not enough of a price is paid here, I thought.

Arthur: Legend of the Sword

Guy Ritchie's daft take on the Arthurian legend has baby Arthur brought up in a brothel in London, where he grows into a right geezer with a common touch before learning he's the king. The title would be more accurately Arthur: Ledge. The film's one redeeming feature is that the London shown is clearly the one built and then abandoned by the Romans, the cheeky cockneys having taken charge of the former temples and circus. Just that panning shot made it worth it.

Goodbye, Christopher Robin

Since I'd read Christoper Robin's own memoir, The Enchanted Place, I knew that the opening premise of this film wasn't right - the boy who played with Winnie the Pooh didn't grow up to die in the Second World War. Yes, the film reveals later on that he survived, but that opening meant I watched this wondering what else had been moulded for dramatic effect. Would Olive, the nanny, really have spoken her mind to the boy's parents? Have the writers been fair to Daphne, the boy's mum?

Even so, that didn't distract too much from the moving story, of a shell-shocked AA Milne and EH Shephard struggling to return to their light-comic lives from before the war. A son and a move to the country both fail to quiet Milne's demons, at least at first. Then a bond builds between father and son that Milne works into his Winnie the Pooh stories - which were hugely successful by any measure, except the one that really mattered. Christopher Robin's enchanted childhood became a nightmare adolescence.

It's a compelling, horrifying story, that the books we so adored caused such misery for the boy in them. I find myself reviewing how much I put my own children in the limelight, on social media or in anything related to my work.

The Dark Tower

This is a humourless action movie about a troubled teenager who is really the special psychic who can either save or destroy the whole universe. The gunslinger he teams up with is played by Idris Elba, who adds a touch of class and is the best thing about the film - but it's a shame he couldn't be smarter or funnier. As the two journey through different realms together, they fight various bad guys and monsters, while the main villain does horrible things to anyone close to them. It's downright nasty: the bad guy killing the boy's mum is oddly unaffecting beyond the immediate shock. I kept hoping it would do something more interesting.

Spider-Man: Homecoming

I'd seen this fun adventure before, and again was struck by its wit, its heart, the villain we can totally sympathise with and the brilliant moment where Spider-Man inadvertently turns up at his front door. A lot of superhero films are about exceedingly strong and well-equipped people beating up villains who often seem less well-off in powers and technology. This new version of Spider-Man works precisely because he's a little guy - young and green and apparently out on his own.

Published on April 04, 2018 11:49

April 3, 2018

Artemis, by Andy Weir

I really enjoyed this rollicking thriller by the author of The Martian. Like that, it's full of practical problem-solving in space, this time on the lunar colony Artemis sometime after the year 2072 (ie more than a hundred years after the last Apollo landing).

I really enjoyed this rollicking thriller by the author of The Martian. Like that, it's full of practical problem-solving in space, this time on the lunar colony Artemis sometime after the year 2072 (ie more than a hundred years after the last Apollo landing).It takes 10 pages before we learn that our gutsy narrator is female. Jasmine "Jazz" Bashira is a porter (ie courier) with a line in illegal smuggling, to the despair of her respectable father - a welder and practising Muslim. She's lived on the Moon since she was six, and since her teens lived a rough existence just about surviving on her own wits. She's canny, adept, brave and wise-cracking, and an engaging character.

Other characters are also well drawn, and towards the end Jazz has to get a bunch of them to work together who we know are going to clash. That works really well. I also liked the minor character inspired by the real-life gruff Londoner who played the first Doctor Who:

"That evening, I hit my favorite watering hole: Hartnell's Pub [...] I loved the place. Partically because Billy was a pleasant bartender, but mainly because it was the closest bar to my coffin."The proof copy I read says film rights to Artmeis have been sold to 20th Century Fox, so I wonder who will play Billy - perhaps he might be CGI.

Andy Weir, Artmeis, p. 32.

Initially it looks like the book will involve a simple heist, but things soon become much more complex - and that lets us explore the lunar colony from inside and out, examining the infrastructure and politics and various power blocs involved. Just as in The Martian, existing in space is fraught with difficulty and danger. But whereas that was effectively Robinson Crusoe on Mars, with one smart astronaut battling the elements - and odds - to stay alive, this is a busier story with villains up to no good.

I have two criticisms. First, although Jazz is an engaging lead, she's also a very blokey one. This is a male-dominated environment and her life is defined by men: the dad she's estranged from; the rich guy she works for; the sort-of cop trying to deport her; the bloke on Earth she gets to send contraband; the various men she has or might have sex with. There are only a small number of women characters - the woman in charge of Artemis, the teenage daughter of her employer, and a scientist working for the bad guys - and it's a shame Jazz doesn't have any female friends of her own age.

I can see that isolates her, makes her situation harder. But it doesn't help that at one point she disguises herself as a prostitute, or that a supposedly symapthetic male character keeps referring to Jazz's breasts. That cuts against what's otherwise a compelling female lead, in a book that deals in issues other writers might have ignored, such as the practicalities of religion or disability while living on the Moon.

I also thought the ending was a bit easy - especially when so much of the book is about things being more tricky than they first appear, and simple jobs having unexpected and dire consequences. Given the scale of the crisis, affecting the whole of the colony, it seems a little unlikely that no one is killed or permanently injured. That comes down to some extraordinary luck on Jazz's part, and perhaps the ending might have been stronger if the cost of saving the colony and ensuring its future was that - as frequently threatened - she got sent back to Earth.

Published on April 03, 2018 05:43

March 27, 2018

Lincoln in the Bardo, by George Saunders

I'm afraid that this odd but acclaimed novel about a grieving father (namely, Abraham Lincoln) left me a bit cold.

I'm afraid that this odd but acclaimed novel about a grieving father (namely, Abraham Lincoln) left me a bit cold.All sorts of things appealed: the lively cast of miscreant ghosts; the mixing up of different historical sources to convey particular moments, the contradictions of the witnesses included; the general weird and morbid tone.

The ghosts are great fun, from all classes and backgrounds, each with their own story to tell (which is what sustains them, and keeps them from moving on). They're a lively dead, and it's a pleasure to be in their company - but is that enough?

Cynically, I can see why this won awards, such as the covetted Man Booker. It's made up of snippets from different sources - apparently real first-hand sources describing Lincoln and fictional ghosts who meet his son (the first-hand sources now long dead, so also ghosts). Often, the snippets are no more than a sentence, so there are few words to a page. The effect is that one races through the book. Imagine the delight of the burdened judge of an award, faced with mountains of volumes to get through! That, and the strange conceit of Lincoln's dead son being in a throng of strange ghosts, and the insights afforded into Lincoln himself, and other novels would seem hard work and boring.

Even more cynically, this might be a novel to appeal to people who don't really like reading novels. Clever, strange, apparently about something important - and quick to get through. It doesn't leave us with torturous questions to mull over long after, as other serious and acclaimed books often do.

For all I raced through it, I didn't think the plot sustained 341 pages and 108 chapters. It's a novella, really - perhaps even a short story. What actually happens? Well, spoilers, but...

The boy dies; Lincoln grieves and goes at night to the cemetery to look upon the body; he lingers and then leaves, determined to fight on in the Civil War. Meanwhile, the cemetery's ghosts, in trying to aid the boy, come to their own kinds of peace. But as you read it, there's a lot of, "Lincoln entered the tomb... The ghosts tell amusing, rude anecdotes about their lives... Lincoln had just entered the tomb..." Get on with it, I thought.

I think my disappointment might stem from having just read The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead, set in roughly the same period and roughly the same geographical area. That rattles along at speed, with something profound to say about America and history, and without saying it directly. Instead, this is too much of what Patricia Highsmith referred to, in Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction , as a gimmick novel.

There's also my own status as a grieving father, which I'm sure shadows my response. But this novel takes us to Lincoln at a key moment in his life: the awful death of his favourite son, and the publication of the casuality lists showing the brutal cost of the Civil War. The fundamental problem is that to make the encounter with the ghosts shape or influence what Lincoln then does next would be utterly crass, but not to do so makes the whole thing a bit pointless.

I liked the idea, I liked the characters in it, but couldn't shake a sense of disappointment.

Published on March 27, 2018 07:28

March 25, 2018

The Underground Railroad, by Colson Whitehead

I’ve had this extraordinary book on the stack of books by my bed for a while. It won the Clarke Award last year, and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award. The cover tells us that Barack Obama thought it “terrific.”

I’ve had this extraordinary book on the stack of books by my bed for a while. It won the Clarke Award last year, and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award. The cover tells us that Barack Obama thought it “terrific.”It’s the tale of a slave girl, Cora, who runs away from an abysmally brutal life on a plantation, despite the threat of even more brutal reprisals should she be caught. Cora soon meets up with the “underground railroad” that helps get escaped slaves to the freedom of the north, but the conceit here is that the railroad is not just the name of a loose organisation of helpers. There really are trains, riding tracks hidden deep into American soil.

The judges of the Clarke Award seem to have considered this enough to make the book count as science-fiction, or at least an alternative history that could still be included in its remit. I’m grateful for that because that award first brought the book to my attention. But having read it, I’m not so sure. Whatever the case, it is a brilliant book, one that will linger long in my thoughts.

One particularly impressive achievement is the sheer number of characters, many of them met only fleetingly, who are nevertheless vivid and alive. Characters are often introduced with a telling insight, such as the vicious Ridgeway, the man employed to hunt Cora and the other escapees, whose whole worldview is conveyed in his judgment on other professions.

“If you weren’t a little dirty at the end of the day, you weren’t much of a man.”Between the main sections of the book detailing Cora’s adventures, some supporting characters also have their lives and outlooks explored in single chapters – in some cases after we already know the terrible ways they met their deaths.

Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad, p. 88.

It’s established early that anyone can be suddenly beaten or killed, but often Cora must move on without knowing the fate of those close to her. Then, towards the end, we hear what befell some of those she had to abandon. We’ve covered so much ground and met so many other people yet this news hits us hard because the characters are so well drawn.

The scale and horror of the oppression, delivered in different forms in different states, is appalling. When she first escapes, the railroad gets Cora to South Carolina, which seems heavenly compared to all she’s known before. She considers settling there. But if she hasn’t noticed disquieting aspects, we have. There’s the strict segregation. There’s the icky nature of the job she’s required to do, as part of a living display in a museum. There’s the visit to the doctor, softly smiling as he mentions a method of permanent birth control.

“‘The choice is yours, of course,’ the doctor said. ‘As of this week, it is mandatory for some in the state. Coloured women who have already birthed more than two children, in the name of population control. Imbeciles and the otherwise mentally unfit, for obvious reasons. Habitual criminals. But that doesn’t apply to you, Bessie. Those are women who already have enough burdens. This is just a chance for you to take control over your own destiny.”They then ask her, whatever she decides for herself, to explain the process to the less intelligent girls in her dormitory.

Ibid, p. 135.

That’s another thing the book does very well: exploring how this awful regime is maintained and enforced, the wider systems of oppression as well as individual brutal acts. As it moves from state to state, it becomes a book about America itself, the violence on which it was founded and what might be done.

There’s a debate towards the end among the liberated black people about how to take things further, to end the cycle of horrific abuse when faced with such vested interests. Catching up with the news as I finished the book, I could see a parallel with the recent March for Life against gun violence. And maybe that’s why The Underground Railroad is science-fiction: it’s set in history, but it’s about the future.

Published on March 25, 2018 19:50

March 20, 2018

Bernice Summerfield - Braxiatel in Love

Later this year there will be a thrilling range of releases to mark two decades of Bernice Summerfield's audio adventures - including something by me. It's a delight to be back.

Later this year there will be a thrilling range of releases to mark two decades of Bernice Summerfield's audio adventures - including something by me. It's a delight to be back.For those who might not know...

Benny, a passionate, waspish, brilliant space archaeologist, was created by Paul Cornell and made her debut in Doctor Who Magazine in September 1992, in a preview of Paul's original Doctor Who novel Love and War, published the following month. She accompanied the Doctor through most of the New Adventures books, largely overseen by editor Rebecca Levene. In 1997, the publishers' licence for Doctor Who was not renewed but the New Adventures, and Benny, continued without him, starting with Cornell's Oh No It Isn't!

On 25 and 26 June 1998, in the basement of Intergalactic Arts Studios, 31 Morecombe Street SE17, recording took place on an audio adaptation of Oh No It Isn't - not just the first Benny audio play but the first Big Finish production. Adapted by Jacqueline Rayner, directed by Nicholas Briggs and starring Lisa Bowerman as Benny, the cast included Nicholas Courtney (the Brigadier from Doctor Who), Jo Castleton and Mark Gatiss.

A second adaptation, Beyond the Sun , was recorded in August - written by Matt Jones from his own novel and directed by Gary Russell, this time at Crosstown Studios in Fulham. Both Benny plays went on sale in September 1998, and more followed. The quality of them convinced the BBC to give Big Finish a licence to produce original Doctor Who plays, which began in 1999.

That same year, the New Adventures range of novels ended, and that might have been the end of Benny. But Big Finish stuck by her, and in 2000 began to produce original Benny plays - not adapations - and also their own range of Benny books.

You can skip the next bit because it's all about me...

I first wrote for Benny in Life During Wartime , a prose anthology edited by Cornell and published in 2003. In 2004, I edited the anthology A Life Worth Living and was commissioned for my first Benny play - The Lost Museum , released in 2005. In October 2005, Gary Russell appointed me script editor on the series, and in the summer of 2006, when he left Big Finish to be a script editor on TV Doctor Who, I became producer of Benny, overseeing the 12 plays and six books released between then and January 2008.

I also wrote Bernice Summerfield: The Inside Story - a history of Benny, and of Big Finish and the period that Doctor Who wasn't on TV - published in 2009. I wrote a story for 2010 anthology Present Danger , a single scene for the audio play Many Happy Returns from 2012, and continue to work with Lisa Bowerman regularly when she directs my other work for Big Finish. But it's been more than 10 years since I wrote a Benny play - until now.

Braxiatel in Love is directed by Scott Handcock and released in September as part of Bernice Summerfield: The Story So Far volume 1, alongside a new play about Bernice in her youth by range producer James Goss, and The Grel Invasion of Earth by Jacqueline Rayner. The blurb for my one goes like this:

"Irving Braxiatel likes to collect things, and when he gains a fiancee, Bernice Summerfield can't help but be suspicious. What are her mysterious employer's motives? It can't just be love, can it? Nothing on the Braxiatel Collection is ever that simple. Not even love."

Published on March 20, 2018 06:51

March 19, 2018

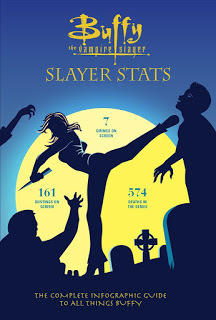

Buffy the Vampire Slayer: Slayer Stats

My new infographics book, Slayer Stats, marks 21 years of the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer with all the graphics-based data a slavering demon can eat.

#BTVS - Slayer Stats“Hilarious,” says Popsugar’s preview of Slayer Stats, blithely overlooking the many dogged months of diligent, cool-headed research. *wipes glasses on handkerchief*

#BTVS - Slayer Stats“Hilarious,” says Popsugar’s preview of Slayer Stats, blithely overlooking the many dogged months of diligent, cool-headed research. *wipes glasses on handkerchief*

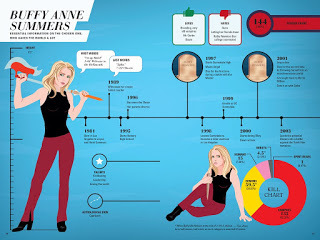

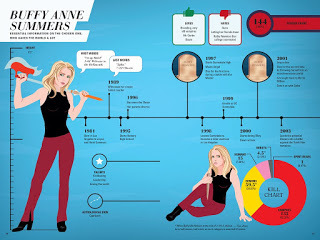

Slayer Stats preview: Buffy Profile

Slayer Stats preview: Buffy Profile

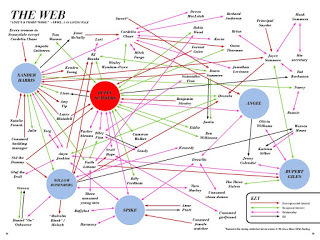

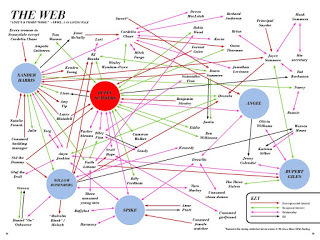

Slayer Stats preview: The Web

Slayer Stats preview: The Web

Slayer Stats – The Complete Infographics Guide to All Things Buffy is written by me and Steve O’Brien, illustrated by Ilaria Vescovo and designed by Stuart Smith. It’s published by Insight Editions on 24 April. I’m not saying the fate of the world depends on you buying a copy, but probably best to get one just in case.

Oh, and Steve and I previously wrote the Doctor Who infographics book Whographica.

#BTVS - Slayer Stats“Hilarious,” says Popsugar’s preview of Slayer Stats, blithely overlooking the many dogged months of diligent, cool-headed research. *wipes glasses on handkerchief*

#BTVS - Slayer Stats“Hilarious,” says Popsugar’s preview of Slayer Stats, blithely overlooking the many dogged months of diligent, cool-headed research. *wipes glasses on handkerchief* Slayer Stats preview: Buffy Profile

Slayer Stats preview: Buffy Profile Slayer Stats preview: The Web

Slayer Stats preview: The WebSlayer Stats – The Complete Infographics Guide to All Things Buffy is written by me and Steve O’Brien, illustrated by Ilaria Vescovo and designed by Stuart Smith. It’s published by Insight Editions on 24 April. I’m not saying the fate of the world depends on you buying a copy, but probably best to get one just in case.

Oh, and Steve and I previously wrote the Doctor Who infographics book Whographica.

Published on March 19, 2018 01:00

March 12, 2018

Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, by Patricia Highsmith

Last week, I ran a workshop for the Hastings Writers' Group on writing science fiction, my brief that this was a bunch of enthusiastic, hard-working writers - many of them professionally published - who had mostly never dabbled in sf. No pressure.

Last week, I ran a workshop for the Hastings Writers' Group on writing science fiction, my brief that this was a bunch of enthusiastic, hard-working writers - many of them professionally published - who had mostly never dabbled in sf. No pressure.Seeking inspiration, I nosed through guides to writing in a bookshop and fell upon Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction by best-selling author Patricia Highsmith, originally published in 1983. It's a great, breezy, enthusiastic and honest account of her process, from where she gets her ideas to dealing with publishers' notes on the manuscript. She's often specific, giving insights into her most famous novels, so it's a book for fans of thrilling fiction as well as for would-be writers.

Among the gems imparted is to base the events of your story on real "emotional experience", felt or observed first hand. Even small events that affect us should be recorded in notebooks to be exploited later. The reason for this is that suspense stories - and the kind of sci-fi nonsense I write - often involve events far outside the author's direct experience. But emotional responses are transferable. Highsmith's example is some teenagers larking about outside her window who made her feel uncomfortable - a feeling she then applied to more tangible, thrilling events for a novel.

While much of the advice is very useful, it's clear it comes from another age. For one thing, even though the book entirely consists of Highsmith's own perspective, she refers to the author - and reader - in the third person as "he" thoughout. The feeling is that she's a rare exception in an otherwise male domain.

For another, there's a lot on the mechanics of writing in the age before word processing computers. She counsels us not to make carbon copies when typing up our first and second drafts, and advises us to retype whole pages or sections only if the earlier draft is too covered in notes. Even though she says she reworks and revises as she retypes her work, the sense is that - because of the technology involved - there were many fewer revisions made in the old days. That's not to say it was better then, or now; just notably different.

Given the slow plod of manually typing a new draft, I found it particularly bruising when Highsmith talks about her novel, The Two Faces of January, being turned down by the publisher Harper & Row, with whom she'd enjoyed years of success. They were not turning down a first draft, but the revised second or third version - a proper, professional submission. Ouch. So how did Highsmith respond?

"I let time go by and wrote another book, which was accepted, and then returned to January and rewrote it, but without referring to the first manuscript, because I completely changed the plot, the age and character of the wife and the character of the young hero - everything except the layout of the Palace of Knossos; three-quarters of a page was all I used of the first manuscript. The charm of that musty old hotel in Athens [her real experience] and the fascination of the young man on meeting a stranger who resembled his father (and a stranger who was a crook) [her seed idea the novel had grown from], these still held me fascinated, and inspired me to write another two hundred and fifty or three hundred pages in order to use these characters. The second and present version of The Two Faces of January was also rejected out of hand by Harper & Row, and this time I thought they were wrong, though I shelved the book, mentally at least, and did not know what to do except write another book. These little setbacks, amounting sometimes to thousands of dollars' worth of time wasted, writers must learn to take like Spartans. A brief curse, perhaps, then tighten the belt a notch and on to something new - of course with enthusiasm, courage and optimism, because without these three elements, you cannot produce anything good."The cost of it, in time and money, is something that resonates all too strongly. By coincidence, last week a spec novel I've written was turned down by yet another publisher, but with notes that have helped me clarify my own thoughts about how it should be reworked - drastically, from the ground up, but retaining the basic plot and the seed ideas that first excited me when I thought of them. It's a gruelling prospect to have to start again, and I'd already decided to write something else first. Highsmith has quite inspired me to push on.

Patricia Highsmith, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, p. 113.

(It's some solace that Highsmith tells us The Two Faces of January was taken up by another publisher, Heinemann, and went on to win a prestigious award from the Crime Writers Association.)

In her final pages, Highsmith makes some general comments - on her discomfort with genre labels, on raising the quality of novels, on her works being adapted as films. But a few grumbles aside, she concludes with some words on the joy, and freedom, of being a writer. It's a book full of practical tips, but Highsmith's most important lesson is her attitude.

Published on March 12, 2018 04:49

Simon Guerrier's Blog

- Simon Guerrier's profile

- 60 followers

Simon Guerrier isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.