Rodrigo Constantino's Blog, page 420

September 5, 2011

A África de Naipaul

LUIZ FELIPE PONDÉ, Folha de SP

QUER CONHECER um pouco sobre a África? Leia V. S. Naipaul. Recomendo. Aliás, o Nobel recomenda. Mas Nobel não basta. Saramago foi Nobel e sempre o achei um chato. Seu livro sobre Caim é um desfile de bobagens e desinformações sobre a Bíblia. Qualquer um que conheça um pouco desse clássico da literatura hebraica antiga perceberá que Saramago não entendia nada sobre o assunto.

Leia "A Máscara da África - Vislumbres das Crenças Africanas", publicado no Brasil pela Companhia das Letras. O livro traz a narrativa da recente visita de Naipaul a alguns países da África. O resultado é um jornalismo sofisticado em detalhes e reflexivo tanto na forma quanto no conteúdo.

O intrigante, hoje em dia, é que muito "inteligentinho" acha que combater o preconceito é inventar mitos de bondade e pureza sobre o "outro". Naipaul é um antídoto contra essa doença infantil.

Aliás, algo que surpreende Naipaul com relação à África é o fato de que muitos povos de lá não tinham alcançado a escrita antes de entrar em contato com muçulmanos e cristãos (ou seja, "ontem"), quase todo seu passado é mito e quase nada é história. É mais ou menos como viver em delírio constante quanto ao seu passado, sem saber o que de fato foi real e o que foi apenas devaneio.

É comum tratar Naipaul como "eurocêntrico", o que, por si só, já é uma boa recomendação, pois significa que a moçada politicamente correta, que exerce essa censura sem caráter, não gosta dele.

Não há nada no livro que nos remeta a "preconceitos", mas há, sim, muita coisa que revela a tristeza que ainda assola a África e que sempre existiu, mesmo antes dos absurdos que os brancos fizeram por lá. A grande mentira sobre a África é que os brancos tornaram-na violenta, pobre e infeliz. Não, ela é assim há muito tempo. Mas os europeus tampouco ajudaram.

Hoje em dia, é comum obrigar alunos a estudar a história da África. Pergunto-me como isso é feito. Temo que a África seja compreendida como um doce de coco que só não é melhor por culpa dos malvados brancos.

Não, todos os homens são maus, pouco importam cor, sexo, raça ou crença. Alguns poucos se destacam pelo bem. É verdade que esgotos, estradas e a recusa embutida nos sacrifícios humanos ajudem um pouco a você deixar de ser um bárbaro.

O livro de Naipaul dá atenção especial às crenças africanas. A catequese cristã e a islâmica destruíram o tecido das crenças ancestrais de muitos africanos, os deixando nem lá nem cá.

Por exemplo, queimar pessoas vivas foi um hábito dos povos africanos até "ontem". Ou melhor dizendo, até "hoje".

Matar, despedaçar, cortar órgãos e queimar pessoas por razões religiosas (e outras) sempre foi uma prática comum entre povos de Uganda, por exemplo. Em grandes quantidades.

Sim, eu sei que europeus também fizeram isso. Lembra o que eu disse acima sobre os homens serem maus? Mas a questão aqui não é essa, mas, sim, combater o "preconceito" de que a miséria material e moral africanas tenham sido criadas pelos europeus.

O encontro de culturas que não conheciam a roda até "ontem" (é isso aí...) com os colonizadores europeus (que nunca tiveram nada de bonzinhos) criou países à deriva.

Exemplos de tragédias cotidianas entre populações pobres numa mesma edição de um jornal ugandense:

1 - "Homem queima dez pessoas numa cabana". Um homem briga com sua mulher, joga gasolina e toca fogo. Entre as dez pessoas, sete eram crianças.

2 - "Meu marido foi cortado em pedaços com um machado na minha frente". Além de matar o marido, o assassino cortou uma mão da mulher; enquanto despedaçava a vítima, acusava-a de poligamia, daí a suspeita de que algo de cristianismo x "paganismo" estava em jogo na "disputa".

3 - "Acusada de queimar filho vivo". Esse parece ser um gosto da "cultura ugandense" mais "primitiva": queimar gente viva; o filho de 18 meses estava num saco com as pernas atadas.

Fora as manchetes, a bruxaria é comum até hoje. Diretores de escolas podem ser mortos por serem acusados de bruxaria e irmãos podem matar sua tia de 42 anos, além de arrancar sua mandíbula e sua língua com o intuito de fazer mágica. Até hoje, a bruxaria é "oficial" em muitos lugares da África.

Puro neolítico?

QUER CONHECER um pouco sobre a África? Leia V. S. Naipaul. Recomendo. Aliás, o Nobel recomenda. Mas Nobel não basta. Saramago foi Nobel e sempre o achei um chato. Seu livro sobre Caim é um desfile de bobagens e desinformações sobre a Bíblia. Qualquer um que conheça um pouco desse clássico da literatura hebraica antiga perceberá que Saramago não entendia nada sobre o assunto.

Leia "A Máscara da África - Vislumbres das Crenças Africanas", publicado no Brasil pela Companhia das Letras. O livro traz a narrativa da recente visita de Naipaul a alguns países da África. O resultado é um jornalismo sofisticado em detalhes e reflexivo tanto na forma quanto no conteúdo.

O intrigante, hoje em dia, é que muito "inteligentinho" acha que combater o preconceito é inventar mitos de bondade e pureza sobre o "outro". Naipaul é um antídoto contra essa doença infantil.

Aliás, algo que surpreende Naipaul com relação à África é o fato de que muitos povos de lá não tinham alcançado a escrita antes de entrar em contato com muçulmanos e cristãos (ou seja, "ontem"), quase todo seu passado é mito e quase nada é história. É mais ou menos como viver em delírio constante quanto ao seu passado, sem saber o que de fato foi real e o que foi apenas devaneio.

É comum tratar Naipaul como "eurocêntrico", o que, por si só, já é uma boa recomendação, pois significa que a moçada politicamente correta, que exerce essa censura sem caráter, não gosta dele.

Não há nada no livro que nos remeta a "preconceitos", mas há, sim, muita coisa que revela a tristeza que ainda assola a África e que sempre existiu, mesmo antes dos absurdos que os brancos fizeram por lá. A grande mentira sobre a África é que os brancos tornaram-na violenta, pobre e infeliz. Não, ela é assim há muito tempo. Mas os europeus tampouco ajudaram.

Hoje em dia, é comum obrigar alunos a estudar a história da África. Pergunto-me como isso é feito. Temo que a África seja compreendida como um doce de coco que só não é melhor por culpa dos malvados brancos.

Não, todos os homens são maus, pouco importam cor, sexo, raça ou crença. Alguns poucos se destacam pelo bem. É verdade que esgotos, estradas e a recusa embutida nos sacrifícios humanos ajudem um pouco a você deixar de ser um bárbaro.

O livro de Naipaul dá atenção especial às crenças africanas. A catequese cristã e a islâmica destruíram o tecido das crenças ancestrais de muitos africanos, os deixando nem lá nem cá.

Por exemplo, queimar pessoas vivas foi um hábito dos povos africanos até "ontem". Ou melhor dizendo, até "hoje".

Matar, despedaçar, cortar órgãos e queimar pessoas por razões religiosas (e outras) sempre foi uma prática comum entre povos de Uganda, por exemplo. Em grandes quantidades.

Sim, eu sei que europeus também fizeram isso. Lembra o que eu disse acima sobre os homens serem maus? Mas a questão aqui não é essa, mas, sim, combater o "preconceito" de que a miséria material e moral africanas tenham sido criadas pelos europeus.

O encontro de culturas que não conheciam a roda até "ontem" (é isso aí...) com os colonizadores europeus (que nunca tiveram nada de bonzinhos) criou países à deriva.

Exemplos de tragédias cotidianas entre populações pobres numa mesma edição de um jornal ugandense:

1 - "Homem queima dez pessoas numa cabana". Um homem briga com sua mulher, joga gasolina e toca fogo. Entre as dez pessoas, sete eram crianças.

2 - "Meu marido foi cortado em pedaços com um machado na minha frente". Além de matar o marido, o assassino cortou uma mão da mulher; enquanto despedaçava a vítima, acusava-a de poligamia, daí a suspeita de que algo de cristianismo x "paganismo" estava em jogo na "disputa".

3 - "Acusada de queimar filho vivo". Esse parece ser um gosto da "cultura ugandense" mais "primitiva": queimar gente viva; o filho de 18 meses estava num saco com as pernas atadas.

Fora as manchetes, a bruxaria é comum até hoje. Diretores de escolas podem ser mortos por serem acusados de bruxaria e irmãos podem matar sua tia de 42 anos, além de arrancar sua mandíbula e sua língua com o intuito de fazer mágica. Até hoje, a bruxaria é "oficial" em muitos lugares da África.

Puro neolítico?

Published on September 05, 2011 09:10

Why austerity is only cure for the eurozone

By Wolfgang Schäuble, Financial Times

In recent weeks, debt markets have undergone wild gyrations, leading some analysts and commentators to question the progress achieved in taming the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone. More recently, economic data and forward-looking indicators have emerged that many economists think point to a faltering of the global recovery, compounding the general anxiety.

Instead of focusing minds, however, these developments have prompted a cacophony of prescriptions about what western governments should do next. There have been calls on regulators to rein in speculators, on the central banks to loosen monetary policy further, on the US and Germany to use their supposed "fiscal space" to encourage demand and on EU leaders to take an immediate leap into a fiscal union and joint liability. Now more than ever is a time for clear messages and clear priorities.

Whatever role the markets may have played in catalysing the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone, it is an undisputable fact that excessive state spending has led to unsustainable levels of debt and deficits that now threaten our economic welfare. Piling on more debt now will stunt rather than stimulate growth in the long run. Governments in and beyond the eurozone need not just to commit to fiscal consolidation and improved competitiveness – they need to start delivering on these now.

The recipe is as simple as it is hard to implement in practice: western democracies and other countries faced with high levels of debt and deficits need to cut expenditures, increase revenues and remove the structural hindrances in their economies, however politically painful. Some progress has already been achieved in this respect, but more needs to be done. Only this course of action can lead to sustainable growth as opposed to short-term volatile bursts or long-term economic decline.

There is some concern that fiscal consolidation, a smaller public sector and more flexible labour markets could undermine demand in these countries in the short term. I am not convinced that this is a foregone conclusion, but even if it were, there is a trade-off between short-term pain and long-term gain. An increase in consumer and investor confidence and a shortening of unemployment lines will in the medium term cancel out any short-term dip in consumption.

These efforts will inevitably bear fruit, but it will not come overnight. This time, we will have to take the longer view. For too long we have forsaken long-term gains for short-term gratification with the result we all know.

The members of the eurozone have and will continue to collectively provide conditional financial assistance to those countries that find themselves cut off from capital markets, buying them time to put their public finances on a sustainable footing and to improve their competitiveness. There are risks to this strategy. Yet the alternative, by allowing the crisis to infect the eurozone as a whole and threaten the euro, would be riskier still.

When markets become the bearer of bad news, there is a natural tendency to take aim at the messenger. The truth is that governments need the disciplining forces of markets. But markets, like the human beings they are made of, do not always act rationally. In uncertain times and absent a robust regulatory framework, their volatility can exacerbate a crisis.

There is a broad consensus now that more robust, crisis-resistant markets need strong regulation. But the process is laborious and momentum in the G20 appears to be fading. In this context, it may become necessary for key countries to move ahead unilaterally in specific areas. Last year, Germany introduced a limited yet controversial ban on naked short-selling. Today, I would see the introduction of a financial transaction tax in Europe as another case for such a "pacemaker-approach" by a few, important pioneers.

One central lesson of the financial crisis was that markets could only function properly if risk-taking were not divorced from liability. The loosening of this bond was a central factor of the crisis. Likewise, the eurozone crisis unfolded after a decade during which economies with markedly different and, indeed, diverging fiscal profiles and competitiveness were all able to borrow at close to benchmark rates.

Hence my unease when some politicians and economists call on the eurozone to take a sudden leap into fiscal union and joint liability. Not only would such a step fail to durably solve the crisis by addressing only its most superficial symptoms, but it could make it worse in the medium term by removing a key incentive for the weaker members to forge ahead with much-needed reforms. It would also go against the very nature of European integration. Europe has always moved forward one step at a time and it should continue to do so. This does not mean that fiscal policy in the eurozone should not gradually become more centralised. It should, as long as this process is legitimised by a strong democratic mandate. But strengthening the architecture of the eurozone will need time. It may need profound treaty changes, which will not happen overnight. But the direction is not disputed, and the determination of all member states to defend the common European currency is granted.

The writer is Germany's federal minister of finance

In recent weeks, debt markets have undergone wild gyrations, leading some analysts and commentators to question the progress achieved in taming the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone. More recently, economic data and forward-looking indicators have emerged that many economists think point to a faltering of the global recovery, compounding the general anxiety.

Instead of focusing minds, however, these developments have prompted a cacophony of prescriptions about what western governments should do next. There have been calls on regulators to rein in speculators, on the central banks to loosen monetary policy further, on the US and Germany to use their supposed "fiscal space" to encourage demand and on EU leaders to take an immediate leap into a fiscal union and joint liability. Now more than ever is a time for clear messages and clear priorities.

Whatever role the markets may have played in catalysing the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone, it is an undisputable fact that excessive state spending has led to unsustainable levels of debt and deficits that now threaten our economic welfare. Piling on more debt now will stunt rather than stimulate growth in the long run. Governments in and beyond the eurozone need not just to commit to fiscal consolidation and improved competitiveness – they need to start delivering on these now.

The recipe is as simple as it is hard to implement in practice: western democracies and other countries faced with high levels of debt and deficits need to cut expenditures, increase revenues and remove the structural hindrances in their economies, however politically painful. Some progress has already been achieved in this respect, but more needs to be done. Only this course of action can lead to sustainable growth as opposed to short-term volatile bursts or long-term economic decline.

There is some concern that fiscal consolidation, a smaller public sector and more flexible labour markets could undermine demand in these countries in the short term. I am not convinced that this is a foregone conclusion, but even if it were, there is a trade-off between short-term pain and long-term gain. An increase in consumer and investor confidence and a shortening of unemployment lines will in the medium term cancel out any short-term dip in consumption.

These efforts will inevitably bear fruit, but it will not come overnight. This time, we will have to take the longer view. For too long we have forsaken long-term gains for short-term gratification with the result we all know.

The members of the eurozone have and will continue to collectively provide conditional financial assistance to those countries that find themselves cut off from capital markets, buying them time to put their public finances on a sustainable footing and to improve their competitiveness. There are risks to this strategy. Yet the alternative, by allowing the crisis to infect the eurozone as a whole and threaten the euro, would be riskier still.

When markets become the bearer of bad news, there is a natural tendency to take aim at the messenger. The truth is that governments need the disciplining forces of markets. But markets, like the human beings they are made of, do not always act rationally. In uncertain times and absent a robust regulatory framework, their volatility can exacerbate a crisis.

There is a broad consensus now that more robust, crisis-resistant markets need strong regulation. But the process is laborious and momentum in the G20 appears to be fading. In this context, it may become necessary for key countries to move ahead unilaterally in specific areas. Last year, Germany introduced a limited yet controversial ban on naked short-selling. Today, I would see the introduction of a financial transaction tax in Europe as another case for such a "pacemaker-approach" by a few, important pioneers.

One central lesson of the financial crisis was that markets could only function properly if risk-taking were not divorced from liability. The loosening of this bond was a central factor of the crisis. Likewise, the eurozone crisis unfolded after a decade during which economies with markedly different and, indeed, diverging fiscal profiles and competitiveness were all able to borrow at close to benchmark rates.

Hence my unease when some politicians and economists call on the eurozone to take a sudden leap into fiscal union and joint liability. Not only would such a step fail to durably solve the crisis by addressing only its most superficial symptoms, but it could make it worse in the medium term by removing a key incentive for the weaker members to forge ahead with much-needed reforms. It would also go against the very nature of European integration. Europe has always moved forward one step at a time and it should continue to do so. This does not mean that fiscal policy in the eurozone should not gradually become more centralised. It should, as long as this process is legitimised by a strong democratic mandate. But strengthening the architecture of the eurozone will need time. It may need profound treaty changes, which will not happen overnight. But the direction is not disputed, and the determination of all member states to defend the common European currency is granted.

The writer is Germany's federal minister of finance

Published on September 05, 2011 07:58

September 4, 2011

Milton Friedman's Euro Smackdown

By GENE EPSTEIN, Barron's

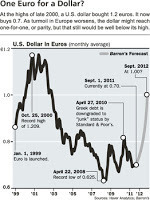

Speaking in 1998, just before the launch of the euro in January of the following year, monetary economist Milton Friedman said he was "not optimistic" about the new currency's prospects. "Suppose things go badly, and Italy is in trouble," he observed with eerie prescience.

An independently traded Italian lira, he pointed out, meant the problem could largely be addressed by a plunge in the lira's exchange rate. The downward adjustment in the exchange rate would, in effect, push the troubled economy's prices and wages much lower, in relation to those of neighboring economies, greatly enhancing relative competitiveness. But with a single currency shared by all neighbors, the surgical advantage of this single price-correction mechanism is no longer available. Prices and wages would actually have to fall instead, a much more difficult feat. The likelihood of such "asymmetric shocks hitting the different countries," said Friedman, meant that the euro had an uncertain future.

The economist, who died in 2006, didn't live to see some of his worst fears about the euro become reality, in the form of today's sovereign-debt crises. Plunges in separate currencies would have done much to prevent them, since the troubled debt would have had far more attractive values. But the asymmetric shocks now threatening this noble experiment have, to varying degrees, hit euro members Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain.

If currency adjustments within the euro zone aren't possible, however, then why not outside it? The dollar looks historically undervalued in relation to the euro (see chart). A good case can be made that the dollar is a buy at its current price of 70 European cents. The greenback might climb to parity with the euro over the next 12 months. Inversely, this means the euro, now worth about $1.43, would fall to $1, still well above its 82.7-cent low of October 2000.

BUT IF THE EURO HAS INDEED BEEN swooning from the asymmetric shocks Friedman warned about, why hasn't it fallen already, at least in relation to the dollar? Greek debt was downgraded to "junk" status by Standard & Poor's in April of last year. Since then, the dollar has actually weakened in relation the euro.

One answer is that the dollar hasn't been looking especially attractive either, since the U.S. economy has been suffering a few well-publicized shocks of its own, including S&P's downgrade of U.S. Treasury debt early last month. So far, then, both currencies have been engaged in a kind of race to the bottom, with the relatively stable exchange rate reflecting a standoff between the two.

The bulls' scenario for the dollar against the euro is based on the conviction that events will significantly alter the market's perception about the relative value of the two currencies, greatly to the euro's detriment. Currency-fund manager John Floyd of New York-based Floyd Capital, who recently went long the dollar, cites a number of storm clouds that could significantly darken the euro zone's prospects. These include difficulties arising from the rescue package assembled in late July, which Floyd avers will result in a "disorderly restructuring of Greek debt by the end of the year."

Adding further to the euro-gloom, in Floyd's view, is that even German Chancellor Angela Merkel's coalition is beginning to question the wisdom of current and future bailouts of weak euro-zone economies. Brown Brothers Harriman currency strategist Marc Chandler, a mild dollar bull, points out that the German high court could issue a ruling on the legality of bailouts as soon as this Wednesday, Sept. 7, with the risk of repercussions for the euro.

Then add the risk that Spain and Italy could come into the picture increasingly as bailout candidates, says Floyd, at a potential cost that would exceed that of Greece by many orders of magnitude.

Dollar bulls tend to emphasize the euro side of the equation. On the dollar side, it is likely that perceptions about the U.S. economy will take a turn for the better.

Recession fears in the U.S. probably abated last week, with the release of August's ISM manufacturing index, which showed continued expansion in domestic manufacturing. Economist Carsten Valgreen, who tracks Europe for Vail, Colo.-based Benderly Economics, believes the euro zone is probably at zero growth in the current quarter. That divergence should help narrow the interest-rate spread between the euro zone and the U.S., to the euro's detriment.

When asked, Valgreen says he, too, would be a dollar bull from these levels. Even though he publishes specific trading recommendations based on his macroeconomic forecasts, he avoids currency trades, in the belief that exchange rates often behave perversely.

He may be right. But broad dollar/euro movements have largely reflected macroeconomic differences. Euro weakness from 1999 through mid-2001 coincided with the tail end of the productivity and stock-market resurgence in the U.S. The gradual recovery of the euro to its 2008 highs reflected the growing credibility of the European Central Bank, while the Federal Reserve presided over a housing bubble.

So perhaps another major move, reflecting a very different sea change in perceptions, is just about to happen. Milton Friedman might approve. [image error]

Published on September 04, 2011 12:26

Controle da imprensa

Comentário sobre o IV Congresso Nacional do PT, que deixa claro novamente o velho projeto totalitário dos petralhas.[image error]

Published on September 04, 2011 07:53

September 2, 2011

Buttonwood: The lowdown

The Economist

BOND-MARKET vigilantes have a ferocious reputation but it turns out they can be very forgiving. Although Standard & Poor's has downgraded America's credit rating and the 2011 budget deficit is expected to be 9% of GDP, the Treasury can still borrow at a remarkably cheap rate. On August 31st all Treasury bonds maturing within five years were yielding less than 1%.

Short-term bond yields are driven by expectations about the outlook for official interest rates. The Federal Reserve has committed itself to keeping rates at their current ultra-low level (between zero and 0.25%) for the next two years. In turn, such low rates also drag down bond yields at longer maturities.

It all looks very Japanese. As the chart shows, since 1999 ten-year Treasury-bond yields have followed a remarkably similar path to that taken by Japanese bond yields after that country's economic bubble burst in 1990. The big question is whether they will now stabilise, as Japanese yields did, in the 1-2% range.

Much will depend on the outlook for inflation. Japan had a brief period of deflation in the mid-1990s, followed by a more consistent pattern of flattish prices over the past decade. Real yields have thus been positive for much of the period.

In contrast, the brief burst of American deflation in 2009 was followed by a strong rebound in prices. Headline inflation is running at 3.6%, making real yields markedly negative. (The same is true for real yields on inflation-linked bonds.) That makes bonds look a pretty unattractive option unless investors believe deflation is on its way.

According to the Barclays US bond index, the last time that nominal yields were around today's level was in 1949 and 1950. Investors who bought bonds back then saw the real value of their holdings halved by the late 1960s. But strategists at Société Générale estimate that the fair value for ten-year Treasury bonds (based on growth and inflation rates over the previous ten years) is just 2.75%, not a long way above current levels. Bonds looked far more overvalued, on this model, in 2002 and 2008.

The bond market is a rather better forecaster of recessions than the average economist. There has been a sharp fall in bond yields even though the Fed's programme of quantitative easing (creating money to buy bonds) stopped at the end of June, taking a large source of demand out of the market. That is a clear sign that investors are worried about economic growth.

It is true that one big recessionary signal has not appeared—the inversion of the yield curve (meaning that long-term yields fall below short-term rates). But it is impossible to generate such a signal at the moment thanks to the Fed's policy of near-zero short rates. And that policy is itself a sign that the central bank is extremely concerned about the economic outlook.

Once the debt crisis broke in 2007, it was clear there were four ways that the mess could develop. The best hope was for economies to grow their way out of the problem. But the recovery has been so anaemic that output in the world's largest developed economies is still below its 2008 levels.

The second route was to inflate the debt away. Headline inflation rates have risen thanks to commodity prices. But there has been no sign yet that the authorities are able to generate a 1970s-style wage-price spiral, even assuming that they want to. There may be some scope for "financial repression", whereby investors are channelled towards government bonds and real yields are held at negative rates for an extended period, but this is a very slow way of reducing debt.

The third path was outright default. That may be on the cards for Greece but, barring political miscalculation, the chances of it are remote for countries, like America and Britain, which can issue debt in their own currencies.

The fourth possibility was stagnation, which takes us back to the Japanese example. Plenty of investors and commentators have lost money (or face) during the past decade by predicting that Japanese bond yields would rise sharply. But even though Japan's debt-to-GDP ratio is far higher than those of America and much of Europe, there is no sign yet of imminent collapse.

Japanese investors have proved happy to hold bonds, given that the alternatives have been the country's moribund equity and property markets. Its example shows why low bond yields are not good news at all for equity and property markets in America and Europe. Instead they are a dreadful omen.[image error]

Published on September 02, 2011 15:09

The Great Recession and Government Failure

By GARY S. BECKER, WSJ

When comparing the performance of markets to government, markets look pretty darn good

The origins of the financial crisis and the Great Recession are widely attributed to "market failure." This refers primarily to the bad loans and excessive risks taken on by banks in the quest to expand their profits. The "Chicago School of Economics" came under sustained attacks from the media and the academy for its analysis of the efficacy of competitive markets. Capitalism itself as a way to organize an economy was widely criticized and said to be in need of radical alteration.

Although many banks did perform poorly, government behavior also contributed to and prolonged the crisis. The Federal Reserve kept interest rates artificially low in the years leading up to the crisis. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two quasi-government institutions, used strong backing from influential members of Congress to encourage irresponsible mortgages that required little down payment, as well as low interest rates for households with poor credit and low and erratic incomes. Regulators who could have reined in banks instead became cheerleaders for the banks.

This recession might well have been a deep one even with good government policies, but "government failure" added greatly to its length and severity, including its continuation to the present. In the U.S., these government actions include an almost $1 trillion in federal spending that was supposed to stimulate the economy. Leading government economists, backed up by essentially no evidence, argued that this spending would stimulate the economy by enough to reduce unemployment rates to under 8%.

Such predictions have been so far off the mark as to be embarrassing. Although definitive studies are not yet available about the stimulus package's overall effects on the American economy, most everyone agrees that it was badly designed and executed. What the stimulus did produce is a sizable expansion of the federal deficit and debt.

The misdiagnosis of widespread market failure led congressional leaders, after the 2008 election, to propose radical changes in financial institutions and, more generally, much wider regulation and government control of companies and consumer behavior. They proposed higher taxes on upper-income families and businesses, and extensive controls over executive pay, as they bashed "billionaire" businessmen with private planes and expensive lifestyles. These political leaders wanted to reformulate antitrust policies away from efficiency, slow the movement by the U.S. toward freer trade, add many additional regulations in the medical-care sector, levy big taxes on energy emissions, and cut opportunities to drill for oil and other fossil fuels.

Congress did manage to pass badly designed laws concerning financial markets, consumer protection and medical care. Although regulatory discretion failed leading up to the crisis, Congress nevertheless added to the number and diversity of federal regulations as well as to the discretion of regulators. These laws and the continuing calls for additional regulations and taxes have broadened the uncertainty about the economic environment facing businesses and consumers. This uncertainty decreased the incentives to invest in long-lived producer and consumer goods. Particularly discouraged was the creation of small businesses, which are a major source of new hires.

The expansion of government resulting from the stimulus and other government programs contributed to rising deficits and growing public debt just when the U.S. faced the prospect of big increases in future debt due to built-in commitments to raise government spending on entitlements. Social Security, Medicaid and Medicare already account for about 40% of total federal government spending, and this share will grow rapidly during the next couple of decades unless major reforms are adopted.

A reasonably well-functioning government would try to sharply curtail the expected growth in entitlements, but such reform is not part of the budget deal between Congress and President Obama that led to a higher debt ceiling. Nor, given the looming 2012 elections, is such reform likely to be addressed seriously by the congressional panel set up to produce further reductions in federal spending.

It is a commentary on the extent of government failure that despite the improvements during the past few decades in the mental and physical health of older men and women, no political agreement seems possible on delaying access to Medicare beyond age 65. No means testing (as in Rep. Paul Ryan's budget roadmap) will be introduced to determine eligibility for full Medicare benefits, and most Social Security benefits will continue to start for individuals at age 65 or younger.

In a nutshell, there is little political will to reduce spending on entitlements by limiting them mainly to persons in need.

State and local governments also greatly increased their spending as tax revenues rolled in during the good economic times that preceded the collapse in 2008. This spending included extensive commitments to deferred benefits that could not be easily reduced after the recession hit, especially pensions and health-care benefits to retired government workers.

Unless states like California and Illinois, and cities like Chicago, take drastic steps to reduce their deferred spending, their problems will multiply as this spending grows over time. A few newly elected governors, such as Scott Walker in Wisconsin, have pushed through reforms to curtail the power of unionized state employees. But most other governors have been afraid to take on the unions and their political supporters.

Numerous examples illustrate government failure in other countries as well. Highly publicized are the troubles facing Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Spain that are mainly due to the growth in spending and debt of their governments prior to the 2008 crisis. Perhaps the governments of these countries, and the banks that bought their debt, expected Germany and other rich members of the European Union to bail them out if they got into trouble. Whatever the explanation, the reckless behavior by these governments will greatly harm businesses and consumers in their countries along with taxpayers of countries coming to their rescue.

The traditional case for private competitive markets goes back to Adam Smith (and even earlier writers). It is mainly based on abundant evidence that most of the time competitive markets work quite well, usually much better than government alternatives. The main reason is not that individuals in the private sector are intrinsically better than government bureaucrats and politicians, but rather that competitive pressures discipline market behavior much more effectively than government actions.

The lesson is that it is crucial to consider whether government regulations and laws are likely to improve rather than worsen the performance of private markets. In an article "Competition and Democracy" published more than 50 years ago, I said "monopoly and other imperfections are at least as important, and perhaps substantially more so, in the political sector as in the marketplace. . . . Does the existence of market imperfections justify government intervention? The answer would be no, if the imperfections in government behavior were greater than those in the market."

The widespread demand after the financial crisis for radical modifications to capitalism typically paid little attention to whether in fact proposed government substitutes would do better, rather than worse, than markets.

Government regulations and laws are obviously essential to any well-functioning economy. Still, when the performance of markets is compared systematically to government alternatives, markets usually come out looking pretty darn good.

Mr. Becker, the 1992 Nobel economics laureate, is professor of economics at the University of Chicago and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. [image error]

Published on September 02, 2011 10:07

A volta dos que não foram

Rodrigo Constantino, para o Instituto Liberal

Hoje se inicia o IV Congresso Nacional do Partido dos Trabalhadores. Segundo noticiado pela imprensa, o PT rediscutirá o projeto defendido por Franklin Martins para a "democratização da imprensa". Apertando a tecla SAP, temos a seguinte tradução: controle dos meios de comunicação. Alas importantes e até mesmo majoritárias do partido nunca conseguiram abandonar este velho ranço stalinista.

A recente matéria de capa da revista VEJA, mostrando o "quartel" das articulações de José Dirceu num hotel em Brasília, foi o pretexto perfeito para o resgate do assunto. Este sombrio personagem da política nacional, acusado de "chefe de quadrilha" pelo procurador-geral da República, continua atuando com incrível desenvoltura e poder nos bastidores de Brasília. Fazer uma reportagem sobre isso é escandaloso demais. Onde já se viu a imprensa tentar realizar seu trabalho investigativo, levantando parte do manto que oculta as podridões da política?

O "bunker virtual" do PT entrou em ação ainda no final de semana em que saiu a matéria. Na segunda-feira seguinte, minha caixa postal já contava com uma dezena de artigos "isentos" indignados com a postura da VEJA. O "spam" destes personagens fictícios criados pelo PT para inundar os emails dos "formadores de opinião" mostra não apenas falta de educação, mas também o tipo de jogo sujo que esta turma está disposta a fazer. Isso sem falar dos blogueiros mais famosos e totalmente "chapa-branca", que não têm qualquer vergonha na cara. O PT embrulha o estômago de qualquer pessoa decente.

No "Blog da Dilma" (http://dilma13.blogspot.com), consta que o texto-base da resolução política que o PT aprovará no seu IV Congresso "defende a extinção do Senado Federal e a adoção do sistema unicameral no âmbito da reforma política". Não sei se a informação procede, mas não fico surpreso se for verdade. O fato é que estamos vendo a volta dos que não foram embora jamais, aqueles "petralhas" que ainda louvam a ditadura cubana e sonham com a "revolução bolivariana" no Brasil. Uma praga que infelizmente se espalhou pelo país todo...[image error]

Published on September 02, 2011 08:21

A decisão do Copom: medida ousada ou irresponsável?

Por Rodrigo Constantino, Valor Econômico

Em uma decisão que surpreendeu quase todos os agentes do mercado - à exceção de alguns bancos que montaram grandes apostas na véspera do evento -, o Copom cortou a taxa básica de juros em 0,5 ponto porcentual na quarta-feira.

Trata-se de medida inesperada, principalmente quando levamos em conta a comunicação com o mercado pelas atas anteriores e o fato de que a inflação, corrente e esperada, encontra-se acima da meta.

Foi uma virada repentina no rumo da Selic, celebrada ontem pelos investidores, que partiram para as compras de ações brasileiras, especialmente as mais sensíveis ao patamar de juros, como as construtoras. O Ibovespa subiu quase 3% no dia, descolando-se das bolsas internacionais. Mas se tal decisão se mostrará correta no longo prazo, ainda é muito cedo para dizer.

O mercado ainda terá de aguardar a nova ata para saber dos pormenores da decisão, que contou com duas dissidências. Mas a linha de argumentação parece ser a deterioração do quadro externo. Afinal, o arrefecimento da economia brasileira não foi forte o suficiente para justificar tal medida. Ou será que o Banco Central sabe de mais coisa que o mercado ignora? Essa leitura, comum quando ocorre dissonância entre o que se espera e o que é feito, produz novas incertezas no mercado. Por isso a transparência do BC é vista como um importante ativo em sua credibilidade.

Aceitando-se a versão de que o foco foi mesmo a piora do cenário internacional, trata-se de muita ousadia do BC. Alguns dados, de fato, mostraram aumento no risco de um duplo mergulho da economia americana, e os fundamentos da Europa também apresentaram piora. Mas ainda é cedo para afirmar que o desenrolar dos fatos será na direção catastrófica. O Copom, portanto, teria especulado ao apostar suas fichas nesse cenário, claramente se antecipando aos possíveis eventos. Será que o BC agora virou um "hedge fund" com Tombini à frente?

Há um fator que não pode ser ignorado de forma alguma nesta equação: a pressão política. Não passou despercebido por ninguém o fato de que a presidente Dilma, na véspera da decisão, afirmou que gostaria de ver uma redução na taxa de juros. A imagem que fica, verdadeira ou não, é a de um BC politizado, sem independência de ação. Institucionalmente, trata-se de algo preocupante, que poderá cobrar elevado preço no futuro. Poucas coisas são tão perigosas para a inflação quanto um BC capturado pelos interesses do governo. O guardião da moeda se transforma em cúmplice do populismo eleitoreiro, alimentando o dragão inflacionário.

Os recentes discursos da presidente apontam na direção correta de maior austeridade fiscal e reformas. Mas, por enquanto, tudo que se tem é pura retórica e intenção anunciada. Se o corte da Selic se deu por conta dessas promessas, então a medida deixa de ser ousada e passa a ser irresponsável. Primeiro, porque sabemos como há um abismo de distância entre desejar o corte de gastos e aprová-lo no Congresso. Ainda mais num Congresso cada vez mais hostil por causa da "faxina" na corrupção. Segundo, porque aquilo colocado na mesa está muito aquém do necessário.

Foi feito grande alarde por causa de R$ 10 bilhões de aumento no superávit primário esperado pelo governo. Isso se levando em conta que houve receita extra quase do mesmo montante, ou seja, é somente uma economia daquilo que entrou a mais. Sem falar que a magnitude da economia é pífia quando se observa o montante dos gastos públicos. Um governo que gasta mais de R$ 1 trilhão falar em economizar R$ 10 bilhões extras é como uma família que gasta R$ 10 mil tentar convencer o credor que será responsável por poupar R$ 100 a mais. É uma piada de mau gosto!

Quanto às reformas, parecem seguir na direção certa, especialmente no que diz respeito à aposentadoria dos funcionários públicos. Mas, novamente, ainda é muito pouco perto do necessário, sem mencionar os enormes obstáculos políticos para sua aprovação. A Previdência Social continua sendo uma bomba-relógio que não explodiu apenas por causa da demografia favorável. Mas a população está envelhecendo, e o governo precisa agir rápido.

O que o afrouxamento monetário prematuro fez foi colocar enorme pressão no Congresso e no Executivo por maior austeridade fiscal. Mas contar com isso é mais do que arriscado; é irresponsável. A decisão do Copom só terá se mostrado acertada se a economia mundial realmente mergulhar em recessão. Caso contrário, foi um grande passo na direção errada, elevando os riscos do descontrole inflacionário. Remediar o erro será bem mais doloroso depois.

Rodrigo Constantino é sócio da Graphus Capital[image error]

Em uma decisão que surpreendeu quase todos os agentes do mercado - à exceção de alguns bancos que montaram grandes apostas na véspera do evento -, o Copom cortou a taxa básica de juros em 0,5 ponto porcentual na quarta-feira.

Trata-se de medida inesperada, principalmente quando levamos em conta a comunicação com o mercado pelas atas anteriores e o fato de que a inflação, corrente e esperada, encontra-se acima da meta.

Foi uma virada repentina no rumo da Selic, celebrada ontem pelos investidores, que partiram para as compras de ações brasileiras, especialmente as mais sensíveis ao patamar de juros, como as construtoras. O Ibovespa subiu quase 3% no dia, descolando-se das bolsas internacionais. Mas se tal decisão se mostrará correta no longo prazo, ainda é muito cedo para dizer.

O mercado ainda terá de aguardar a nova ata para saber dos pormenores da decisão, que contou com duas dissidências. Mas a linha de argumentação parece ser a deterioração do quadro externo. Afinal, o arrefecimento da economia brasileira não foi forte o suficiente para justificar tal medida. Ou será que o Banco Central sabe de mais coisa que o mercado ignora? Essa leitura, comum quando ocorre dissonância entre o que se espera e o que é feito, produz novas incertezas no mercado. Por isso a transparência do BC é vista como um importante ativo em sua credibilidade.

Aceitando-se a versão de que o foco foi mesmo a piora do cenário internacional, trata-se de muita ousadia do BC. Alguns dados, de fato, mostraram aumento no risco de um duplo mergulho da economia americana, e os fundamentos da Europa também apresentaram piora. Mas ainda é cedo para afirmar que o desenrolar dos fatos será na direção catastrófica. O Copom, portanto, teria especulado ao apostar suas fichas nesse cenário, claramente se antecipando aos possíveis eventos. Será que o BC agora virou um "hedge fund" com Tombini à frente?

Há um fator que não pode ser ignorado de forma alguma nesta equação: a pressão política. Não passou despercebido por ninguém o fato de que a presidente Dilma, na véspera da decisão, afirmou que gostaria de ver uma redução na taxa de juros. A imagem que fica, verdadeira ou não, é a de um BC politizado, sem independência de ação. Institucionalmente, trata-se de algo preocupante, que poderá cobrar elevado preço no futuro. Poucas coisas são tão perigosas para a inflação quanto um BC capturado pelos interesses do governo. O guardião da moeda se transforma em cúmplice do populismo eleitoreiro, alimentando o dragão inflacionário.

Os recentes discursos da presidente apontam na direção correta de maior austeridade fiscal e reformas. Mas, por enquanto, tudo que se tem é pura retórica e intenção anunciada. Se o corte da Selic se deu por conta dessas promessas, então a medida deixa de ser ousada e passa a ser irresponsável. Primeiro, porque sabemos como há um abismo de distância entre desejar o corte de gastos e aprová-lo no Congresso. Ainda mais num Congresso cada vez mais hostil por causa da "faxina" na corrupção. Segundo, porque aquilo colocado na mesa está muito aquém do necessário.

Foi feito grande alarde por causa de R$ 10 bilhões de aumento no superávit primário esperado pelo governo. Isso se levando em conta que houve receita extra quase do mesmo montante, ou seja, é somente uma economia daquilo que entrou a mais. Sem falar que a magnitude da economia é pífia quando se observa o montante dos gastos públicos. Um governo que gasta mais de R$ 1 trilhão falar em economizar R$ 10 bilhões extras é como uma família que gasta R$ 10 mil tentar convencer o credor que será responsável por poupar R$ 100 a mais. É uma piada de mau gosto!

Quanto às reformas, parecem seguir na direção certa, especialmente no que diz respeito à aposentadoria dos funcionários públicos. Mas, novamente, ainda é muito pouco perto do necessário, sem mencionar os enormes obstáculos políticos para sua aprovação. A Previdência Social continua sendo uma bomba-relógio que não explodiu apenas por causa da demografia favorável. Mas a população está envelhecendo, e o governo precisa agir rápido.

O que o afrouxamento monetário prematuro fez foi colocar enorme pressão no Congresso e no Executivo por maior austeridade fiscal. Mas contar com isso é mais do que arriscado; é irresponsável. A decisão do Copom só terá se mostrado acertada se a economia mundial realmente mergulhar em recessão. Caso contrário, foi um grande passo na direção errada, elevando os riscos do descontrole inflacionário. Remediar o erro será bem mais doloroso depois.

Rodrigo Constantino é sócio da Graphus Capital[image error]

Published on September 02, 2011 04:26

September 1, 2011

Cartada racial

Alguns democratas americanos, tal como esquerdistas brasileiros, adoram usar a velha "cartada racial". A idéia é disseminar o ódio racial, segregar pessoas em "raças", colocar "brancos" contra "negros", para conquistar o poder. Vejam esta entrevista da Fox News (felizmente ainda há canais que desafiam a máquina esquerdista americana) com David Webb, um dos líderes do movimento Tea Party. Ele rebate a acusação pérfida que o democrata Andre Carson, membro do partido de Obama, fez sobre o movimento libertário, acusando-o de pretender "enforcar os negros nas árvores". O demagogo irresponsável foi convidado para o debate, mas se recusou. É realmente revoltante ver até onde essa turma é capaz de chegar em busca de poder e privilégios. [image error]

Published on September 01, 2011 08:07

O ato indecoroso da Câmara

Editorial do Estadão

Primeiro, a boa notícia: a banda limpa da Câmara dos Deputados congrega 1/3 dos seus 513 membros. São os 166 deputados que, embora protegidos pelo escrutínio secreto, tiveram a decência de votar pela cassação da colega - no sentido puramente formal do termo - Jaqueline Roriz, do PMN do Distrito Federal(DF), filha do notório capo político local Joaquim Roriz. A notícia é boa porque até experientes observadores dos modos e costumes do Legislativo brasileiro calculavam que a bancada da decência seria muito mais rarefeita. Nada, nada, é um consolo.

Agora, a constatação devastadora: Lula talvez tenha sido até generoso quando disse, em 1993, que havia no Congresso "uns 300 picaretas que defendem apenas seus próprios interesses". A julgar pelo desfecho da votação de anteontem, pode-se presumir que só na Câmara eles sejam ainda mais numerosos. São, antes de tudo, os 265 que absolveram a parlamentar filmada em 2006 recebendo dinheiro do pivô (e depois delator) do chamado mensalão do DEM, Durval Barbosa. A bolada se destinava ao caixa 2 da campanha de Jaqueline a um segundo mandato na Câmara Legislativa do DF. A cena foi divulgada em março último pelo portal do Estado.

Aos 265 que não perderam mais essa oportunidade de induzir a opinião pública a perder as migalhas de respeito que ainda pudesse ter por seus representantes, somem-se os 20 que se abstiveram e os 62 que nem sequer compareceram à sessão. Dá um total de 347 deputados. Mesmo que um punhado deles possa oferecer desculpas aceitáveis para a abstenção ou a omissão, o número é acachapante. Não custa lembrar que, em decisão aberta, o Conselho de Ética havia aprovado por 11 a 3 o pedido do PSOL de abertura de processo contra Jaqueline por quebra de decoro, para a sua subsequente expulsão da Casa.

A rigor, os que preservaram o mandato da deputada agiram como quem faz um seguro para proteger a própria carreira. Afinal, mais dia, menos dia, podem surgir contra qualquer deles provas irrefutáveis de bandalheiras que tenham praticado antes de se aboletar no Legislativo federal, pondo em xeque o bem-bom de que desfrutam. A cassação de Jaqueline abriria um intolerável precedente. Criaria uma legítima jurisprudência política, segundo a qual o procedimento indecoroso é incompatível com o processo eleitoral e a atividade parlamentar, seja quando e em que circunstâncias haja ocorrido. Não se trata de refazer a história, como alegam desavergonhadamente os defensores da impunidade.

A razão é simples: os 100.051 eleitores do DF que em outubro passado marcaram na urna eletrônica o nome de Jaqueline não sabiam que ela recebera dinheiro sujo ao menos uma vez, no vasto esquema rorista de corrupção mantido pelo então governador José Roberto Arruda, do DEM. (A propósito, também ele foi flagrado embolsando R$ 50 mil do mesmo operador Durval Barbosa que financiou Jaqueline.) Ainda que 100.050 daqueles eleitores não dessem a mínima para o delito posteriormente evidenciado, bastaria um único caso de lesa-eleitor para tornar ilegítimo o mandato da deputada.

Contesta-se a Lei da Ficha Limpa porque ela impede o registro da candidatura de políticos que tenham sido inculpados por fatos anteriores ao advento da medida saneadora. O argumento é que as leis só podem retroagir em benefício dos réus. Na realidade, porém, o passado de um candidato não pode conter transgressões ao princípio constitucional da moralidade na vida pública. Assim também na questão do decoro parlamentar. Trata-se de uma exigência que precede o momento em que o político põe os pés pela primeira vez numa Casa legislativa.

Já para os deputados que seguraram a cadeira de Jaqueline Roriz, para garantir as deles em circunstâncias similares, é como se a integridade não fosse parte inamovível do caráter de cada qual. Teria uma espécie de prazo de validade às avessas e poderia, ou não, se manifestar conforme a circunscrição territorial em que se movem. Isso, em meio à aberração do voto secreto no Parlamento. Nesse sistema de valores virado de ponta-cabeça, nada mais natural do que a queixa de Jaqueline, antes da votação, de que a imprensa, ao expô-la, havia destruído a sua "honra".[image error]

Primeiro, a boa notícia: a banda limpa da Câmara dos Deputados congrega 1/3 dos seus 513 membros. São os 166 deputados que, embora protegidos pelo escrutínio secreto, tiveram a decência de votar pela cassação da colega - no sentido puramente formal do termo - Jaqueline Roriz, do PMN do Distrito Federal(DF), filha do notório capo político local Joaquim Roriz. A notícia é boa porque até experientes observadores dos modos e costumes do Legislativo brasileiro calculavam que a bancada da decência seria muito mais rarefeita. Nada, nada, é um consolo.

Agora, a constatação devastadora: Lula talvez tenha sido até generoso quando disse, em 1993, que havia no Congresso "uns 300 picaretas que defendem apenas seus próprios interesses". A julgar pelo desfecho da votação de anteontem, pode-se presumir que só na Câmara eles sejam ainda mais numerosos. São, antes de tudo, os 265 que absolveram a parlamentar filmada em 2006 recebendo dinheiro do pivô (e depois delator) do chamado mensalão do DEM, Durval Barbosa. A bolada se destinava ao caixa 2 da campanha de Jaqueline a um segundo mandato na Câmara Legislativa do DF. A cena foi divulgada em março último pelo portal do Estado.

Aos 265 que não perderam mais essa oportunidade de induzir a opinião pública a perder as migalhas de respeito que ainda pudesse ter por seus representantes, somem-se os 20 que se abstiveram e os 62 que nem sequer compareceram à sessão. Dá um total de 347 deputados. Mesmo que um punhado deles possa oferecer desculpas aceitáveis para a abstenção ou a omissão, o número é acachapante. Não custa lembrar que, em decisão aberta, o Conselho de Ética havia aprovado por 11 a 3 o pedido do PSOL de abertura de processo contra Jaqueline por quebra de decoro, para a sua subsequente expulsão da Casa.

A rigor, os que preservaram o mandato da deputada agiram como quem faz um seguro para proteger a própria carreira. Afinal, mais dia, menos dia, podem surgir contra qualquer deles provas irrefutáveis de bandalheiras que tenham praticado antes de se aboletar no Legislativo federal, pondo em xeque o bem-bom de que desfrutam. A cassação de Jaqueline abriria um intolerável precedente. Criaria uma legítima jurisprudência política, segundo a qual o procedimento indecoroso é incompatível com o processo eleitoral e a atividade parlamentar, seja quando e em que circunstâncias haja ocorrido. Não se trata de refazer a história, como alegam desavergonhadamente os defensores da impunidade.

A razão é simples: os 100.051 eleitores do DF que em outubro passado marcaram na urna eletrônica o nome de Jaqueline não sabiam que ela recebera dinheiro sujo ao menos uma vez, no vasto esquema rorista de corrupção mantido pelo então governador José Roberto Arruda, do DEM. (A propósito, também ele foi flagrado embolsando R$ 50 mil do mesmo operador Durval Barbosa que financiou Jaqueline.) Ainda que 100.050 daqueles eleitores não dessem a mínima para o delito posteriormente evidenciado, bastaria um único caso de lesa-eleitor para tornar ilegítimo o mandato da deputada.

Contesta-se a Lei da Ficha Limpa porque ela impede o registro da candidatura de políticos que tenham sido inculpados por fatos anteriores ao advento da medida saneadora. O argumento é que as leis só podem retroagir em benefício dos réus. Na realidade, porém, o passado de um candidato não pode conter transgressões ao princípio constitucional da moralidade na vida pública. Assim também na questão do decoro parlamentar. Trata-se de uma exigência que precede o momento em que o político põe os pés pela primeira vez numa Casa legislativa.

Já para os deputados que seguraram a cadeira de Jaqueline Roriz, para garantir as deles em circunstâncias similares, é como se a integridade não fosse parte inamovível do caráter de cada qual. Teria uma espécie de prazo de validade às avessas e poderia, ou não, se manifestar conforme a circunscrição territorial em que se movem. Isso, em meio à aberração do voto secreto no Parlamento. Nesse sistema de valores virado de ponta-cabeça, nada mais natural do que a queixa de Jaqueline, antes da votação, de que a imprensa, ao expô-la, havia destruído a sua "honra".[image error]

Published on September 01, 2011 05:23

Rodrigo Constantino's Blog

- Rodrigo Constantino's profile

- 32 followers

Rodrigo Constantino isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.