Rodrigo Constantino's Blog, page 408

October 24, 2011

So Much for the Volcker Rule

Editorial do WSJ

Even in 298 pages, regulators can't decide what to regulate

If you tried to write a parody of the uncertainty and confusion triggered by federal rule-making, it would be hard to top the latest proposal from Washington's financial regulators. So here's an ironic hat tip to the bureaucrats who wrote the draft Volcker Rule, which will allegedly limit risk-taking at financial firms backed by taxpayers.

In 298 pages, rather than sketching out simple, clear rules for banks to follow, regulators essentially wonder out loud how they can possibly write this rule. Officially there are 383 questions posed in the document, but many of these questions have multiple parts. Our colleagues at the Deal Journal blog counted 1,347 queries, covering everything from how "trading accounts" should be defined to what a "loan" is.

The regulators admit that "the delineation of what constitutes a prohibited or permitted activity . . . involves subtle distinctions that are difficult both to describe comprehensively within regulation and to evaluate in practice." Think of this as a cry for help from bureaucrats seeking an understanding of the markets they are nonetheless going to restructure come what may.

***

Bank lobbyists are certainly eager to provide some hand-holding. We wouldn't be surprised to see thousands of pages of suggestions roll in between now and January 13, when the public comment period ends. Many of these comments will no doubt offer compelling reasons why a particular type of transaction should be exempt from the principle that nobody should be gambling with a taxpayer backstop. The regulators will then have about six months to consider all of these suggestions, ponder the thousands of answers to their 1,347 questions, and then write a final rule. At least that's what the 2010 fiasco known as Dodd-Frank demands.

Dodd-Frank demands all this from regulators because for the life of them former Senator Chris Dodd and Representative Barney Frank couldn't figure out how to write a Volcker Rule themselves. Like nearly every other tough call in financial regulation, Messrs. Dodd and Frank punted this one to the executive branch, invested federal agencies with new authority, and expected the same regulators who failed to prevent the last crisis to somehow avert the next one.

We supported former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker's concept of a ban on proprietary trading as a good-faith effort to protect taxpayers from having to rescue too-big-to-fail banks again. Democrats in Congress weren't going to prevent future bailouts, so whenever an institution is playing with taxpayer money (via insured deposits or access to the Fed's discount window) it should be allowed to serve clients but should not be permitted to make trades for its own proprietary account. But drafting such a law isn't easy and the details are crucial.

When America's esteemed legislators couldn't figure out how to write a Volcker Rule, they forwarded it to the bureaucracy as a kind of Volcker Suggestion. But before the lawmakers enacted this remarkable delegation of authority, they gutted even the Volcker Suggestion by exempting certain instruments from consideration.

Lawmakers made clear that whatever the shape of the final rule, it would not interfere with the liquidity of the U.S. Treasury market or debt issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. So even if bureaucrats spend most of the next year crafting the perfect rule, it will still allow Wall Street giants to make enormous bets on the direction of U.S. government bonds and debt issued by government-sponsored enterprises. There are also built-in exemptions in the commodities market. There will likely be limits on trading derivatives of commodities, but if traders are buying actual physical assets they can still swing for the fences.

Even outside of these exempted zones of politically favored speculation, the recent proposal suggests that we're not going to get anything close to perfection. And some of the regulators may already have figured this out. Readers will recall that Dodd-Frank created the Financial Stability Oversight Council so that the chiefs of the various regulatory agencies could coordinate their actions to identify and attack risks to the financial system. But one of the knights of this regulatory round table was missing when they decided to saddle up on this quest to tilt at Goldman's risk book.

The draft rule carries the names of various Beltway departments but not the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Since the CFTC now oversees much of the derivatives market, which in Beltway lore is the principal cause of systemic risk, it's an odd omission. A cynic might even wonder if CFTC Chairman Gary Gensler is checking the political winds before endorsing this turkey. A source at the commission says that the agency is backed up fulfilling other Dodd-Frank mandates but will get to Volcker eventually.

***

They shouldn't bother. Reasonable people have seen enough to say that Washington is incapable of drawing bright lines and applying clear rules fairly across all securities markets. The result is all but certain to be a final rule that different people will interpret different ways, leading to loopholes for traders and arbitrary enforcement. Under this Beltway rendering of Volcker, trading will continue but with a much higher bureaucratic cost and with the illusion of safety that only regulation can create.

Until the government is willing to create a durable financial system that allows failure, the best policy response is to make the rules so simple that even Washington can enforce them. That means higher, even very high, bank capital standards and margin requirements on risky trades between banks. Those aren't panaceas, but they offer more hope for taxpayers than the bureaucratic and bank-lobbyist jump ball that is now the Volcker Rule.

Even in 298 pages, regulators can't decide what to regulate

If you tried to write a parody of the uncertainty and confusion triggered by federal rule-making, it would be hard to top the latest proposal from Washington's financial regulators. So here's an ironic hat tip to the bureaucrats who wrote the draft Volcker Rule, which will allegedly limit risk-taking at financial firms backed by taxpayers.

In 298 pages, rather than sketching out simple, clear rules for banks to follow, regulators essentially wonder out loud how they can possibly write this rule. Officially there are 383 questions posed in the document, but many of these questions have multiple parts. Our colleagues at the Deal Journal blog counted 1,347 queries, covering everything from how "trading accounts" should be defined to what a "loan" is.

The regulators admit that "the delineation of what constitutes a prohibited or permitted activity . . . involves subtle distinctions that are difficult both to describe comprehensively within regulation and to evaluate in practice." Think of this as a cry for help from bureaucrats seeking an understanding of the markets they are nonetheless going to restructure come what may.

***

Bank lobbyists are certainly eager to provide some hand-holding. We wouldn't be surprised to see thousands of pages of suggestions roll in between now and January 13, when the public comment period ends. Many of these comments will no doubt offer compelling reasons why a particular type of transaction should be exempt from the principle that nobody should be gambling with a taxpayer backstop. The regulators will then have about six months to consider all of these suggestions, ponder the thousands of answers to their 1,347 questions, and then write a final rule. At least that's what the 2010 fiasco known as Dodd-Frank demands.

Dodd-Frank demands all this from regulators because for the life of them former Senator Chris Dodd and Representative Barney Frank couldn't figure out how to write a Volcker Rule themselves. Like nearly every other tough call in financial regulation, Messrs. Dodd and Frank punted this one to the executive branch, invested federal agencies with new authority, and expected the same regulators who failed to prevent the last crisis to somehow avert the next one.

We supported former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker's concept of a ban on proprietary trading as a good-faith effort to protect taxpayers from having to rescue too-big-to-fail banks again. Democrats in Congress weren't going to prevent future bailouts, so whenever an institution is playing with taxpayer money (via insured deposits or access to the Fed's discount window) it should be allowed to serve clients but should not be permitted to make trades for its own proprietary account. But drafting such a law isn't easy and the details are crucial.

When America's esteemed legislators couldn't figure out how to write a Volcker Rule, they forwarded it to the bureaucracy as a kind of Volcker Suggestion. But before the lawmakers enacted this remarkable delegation of authority, they gutted even the Volcker Suggestion by exempting certain instruments from consideration.

Lawmakers made clear that whatever the shape of the final rule, it would not interfere with the liquidity of the U.S. Treasury market or debt issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. So even if bureaucrats spend most of the next year crafting the perfect rule, it will still allow Wall Street giants to make enormous bets on the direction of U.S. government bonds and debt issued by government-sponsored enterprises. There are also built-in exemptions in the commodities market. There will likely be limits on trading derivatives of commodities, but if traders are buying actual physical assets they can still swing for the fences.

Even outside of these exempted zones of politically favored speculation, the recent proposal suggests that we're not going to get anything close to perfection. And some of the regulators may already have figured this out. Readers will recall that Dodd-Frank created the Financial Stability Oversight Council so that the chiefs of the various regulatory agencies could coordinate their actions to identify and attack risks to the financial system. But one of the knights of this regulatory round table was missing when they decided to saddle up on this quest to tilt at Goldman's risk book.

The draft rule carries the names of various Beltway departments but not the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Since the CFTC now oversees much of the derivatives market, which in Beltway lore is the principal cause of systemic risk, it's an odd omission. A cynic might even wonder if CFTC Chairman Gary Gensler is checking the political winds before endorsing this turkey. A source at the commission says that the agency is backed up fulfilling other Dodd-Frank mandates but will get to Volcker eventually.

***

They shouldn't bother. Reasonable people have seen enough to say that Washington is incapable of drawing bright lines and applying clear rules fairly across all securities markets. The result is all but certain to be a final rule that different people will interpret different ways, leading to loopholes for traders and arbitrary enforcement. Under this Beltway rendering of Volcker, trading will continue but with a much higher bureaucratic cost and with the illusion of safety that only regulation can create.

Until the government is willing to create a durable financial system that allows failure, the best policy response is to make the rules so simple that even Washington can enforce them. That means higher, even very high, bank capital standards and margin requirements on risky trades between banks. Those aren't panaceas, but they offer more hope for taxpayers than the bureaucratic and bank-lobbyist jump ball that is now the Volcker Rule.

Published on October 24, 2011 04:35

October 22, 2011

Debate Hayek vs Keynes

Published on October 22, 2011 07:25

Why Europe Dithers

By HOLMAN W. JENKINS, JR., WSJ

German voters don't want to bail out French banks and the French government can't afford to.

'All political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure." That morbid thought, voiced by a British politician named Enoch Powell in the 1970s, is now playing out in the careers of Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy. Neither leader has an incentive to sacrifice what have become vital and divergent interests to produce a credible bailout plan for Europe. To simplify, German voters don't want to bail out French banks, and the French government can't afford to bail out French banks, when and if the long-awaited Greek default is allowed to happen.

Thus Mr. Sarkozy's re-election hopes are going down the drain, but not as quickly as they would if he acceded to the Merkel plan to let each government rescue its own banks.

Ms. Merkel's hopes for a third term are being eroded in regional election after regional election, though not as quickly as they would if she agreed to put German taxpayers on the hook for France's troubled banking sector.

There is another savior in the wings, of course, the European Central Bank. But the ECB has no incentive to betray in advance its willingness to get France and Germany off the hook by printing money to keep Europe's heavily indebted governments afloat. Yet all know this is the outcome politicians are stalling for. This is the outcome markets are relying on, and why they haven't crashed.

All are waiting for some market ruction hairy enough that the central bank will cast aside every political and legal restraint in order to save the euro.

In doing so, of course, the bank will be acting far above its pay grade, and far outside the law, to make momentous decisions for all of Europe. Which countries will be saved via the bank's willingness to print unlimited euros and buy unlimited assets to keep them out of default?

Which countries will be allowed to default and (if they so choose) drop out of the euro altogether?

These choices the bank understands perfectly well it would be making in lieu of politicians who are unwilling to make such decisions, though not unwilling that such decisions be made. In their non-rescue of Greece last July, Europe's leaders proposed a 21% "voluntary" haircut to Greek debt held by banks, and now scuttlebutt has raised the politically acceptable haircut to 60%.

Though the central bank has been adamantly against a Greek default (because it owns a lot of Greek debt), this means it will surely read its mandate as permission to let Greece default.

The central bank has already stepped up, to wide applause, to keep Spain and Italy afloat when demand for their debt began to evaporate. Italy and Spain are "core" countries that the bank understands the politicians view as too big to fail. And France will likely get a temporary pass from the markets to run up its national debt in order to recapitalize its banks because, obviously, if the ECB won't let Italy and Spain sink, it won't let France sink.

That leaves Portugal and Ireland. Let's just guess that the ECB, aware of how far beyond the pale it has wandered, will act conservatively and prop them up too.

And then the crisis will be over? Not by a long shot.

All these "solvent" countries and their banks will be dependent on the ECB to keep them "solvent," a reality that can only lead to entrenched inflation across the European economy. That is, unless these governments undertake heroic reforms quickly to restore themselves to the good graces of the global bond market so they can stand up again without the ECB's visible help.

It's just conceivable that this might happen—that countries on the ECB life-support might put their nose to the grindstone to make good on their debts, held by ECB and others. Or they might just resume the game of chicken with German taxpayers, albeit in a new form, implicitly demanding that Germany bail out the ECB before the bank is forced thoroughly to debauch the continent's common currency, the euro.

At most the endgame might be extended for a couple of years, but the native pessimists among us will have a hard time believing the single currency can survive. Those countries that consider themselves solvent and disciplined will face a relentlessly growing temptation to get out, led by Germany.

As you will recall, one argument for the euro was that, lacking their own currencies to debauch, countries would have to get a handle on welfare bloat and the disincentives they pile up on workers and entrepreneurs. But a funny thing happened on the way to a "United States of Europe." Only one major country made an effort to reform itself, Germany—the one country whose political culture would never have allowed it to opt for D-mark debauchery in the first place.

We noted as much in a column in 2003, and wondered: "If Germany overhauls itself, will other European states follow suit? Or will their commitment to the euro and a single market wilt in the face of domestic opponents who paint reform as a surrender to the Germans?"

No, this is not a paean to the "unchangeability" of national culture. But some things change slowly and national culture is one of them. It was never likely the rest of Europe would choose to become more like Germany, or Germany choose to become more like rest of Europe, on a schedule that would allow the euro to work. And that's what we're finding out.

German voters don't want to bail out French banks and the French government can't afford to.

'All political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure." That morbid thought, voiced by a British politician named Enoch Powell in the 1970s, is now playing out in the careers of Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy. Neither leader has an incentive to sacrifice what have become vital and divergent interests to produce a credible bailout plan for Europe. To simplify, German voters don't want to bail out French banks, and the French government can't afford to bail out French banks, when and if the long-awaited Greek default is allowed to happen.

Thus Mr. Sarkozy's re-election hopes are going down the drain, but not as quickly as they would if he acceded to the Merkel plan to let each government rescue its own banks.

Ms. Merkel's hopes for a third term are being eroded in regional election after regional election, though not as quickly as they would if she agreed to put German taxpayers on the hook for France's troubled banking sector.

There is another savior in the wings, of course, the European Central Bank. But the ECB has no incentive to betray in advance its willingness to get France and Germany off the hook by printing money to keep Europe's heavily indebted governments afloat. Yet all know this is the outcome politicians are stalling for. This is the outcome markets are relying on, and why they haven't crashed.

All are waiting for some market ruction hairy enough that the central bank will cast aside every political and legal restraint in order to save the euro.

In doing so, of course, the bank will be acting far above its pay grade, and far outside the law, to make momentous decisions for all of Europe. Which countries will be saved via the bank's willingness to print unlimited euros and buy unlimited assets to keep them out of default?

Which countries will be allowed to default and (if they so choose) drop out of the euro altogether?

These choices the bank understands perfectly well it would be making in lieu of politicians who are unwilling to make such decisions, though not unwilling that such decisions be made. In their non-rescue of Greece last July, Europe's leaders proposed a 21% "voluntary" haircut to Greek debt held by banks, and now scuttlebutt has raised the politically acceptable haircut to 60%.

Though the central bank has been adamantly against a Greek default (because it owns a lot of Greek debt), this means it will surely read its mandate as permission to let Greece default.

The central bank has already stepped up, to wide applause, to keep Spain and Italy afloat when demand for their debt began to evaporate. Italy and Spain are "core" countries that the bank understands the politicians view as too big to fail. And France will likely get a temporary pass from the markets to run up its national debt in order to recapitalize its banks because, obviously, if the ECB won't let Italy and Spain sink, it won't let France sink.

That leaves Portugal and Ireland. Let's just guess that the ECB, aware of how far beyond the pale it has wandered, will act conservatively and prop them up too.

And then the crisis will be over? Not by a long shot.

All these "solvent" countries and their banks will be dependent on the ECB to keep them "solvent," a reality that can only lead to entrenched inflation across the European economy. That is, unless these governments undertake heroic reforms quickly to restore themselves to the good graces of the global bond market so they can stand up again without the ECB's visible help.

It's just conceivable that this might happen—that countries on the ECB life-support might put their nose to the grindstone to make good on their debts, held by ECB and others. Or they might just resume the game of chicken with German taxpayers, albeit in a new form, implicitly demanding that Germany bail out the ECB before the bank is forced thoroughly to debauch the continent's common currency, the euro.

At most the endgame might be extended for a couple of years, but the native pessimists among us will have a hard time believing the single currency can survive. Those countries that consider themselves solvent and disciplined will face a relentlessly growing temptation to get out, led by Germany.

As you will recall, one argument for the euro was that, lacking their own currencies to debauch, countries would have to get a handle on welfare bloat and the disincentives they pile up on workers and entrepreneurs. But a funny thing happened on the way to a "United States of Europe." Only one major country made an effort to reform itself, Germany—the one country whose political culture would never have allowed it to opt for D-mark debauchery in the first place.

We noted as much in a column in 2003, and wondered: "If Germany overhauls itself, will other European states follow suit? Or will their commitment to the euro and a single market wilt in the face of domestic opponents who paint reform as a surrender to the Germans?"

No, this is not a paean to the "unchangeability" of national culture. But some things change slowly and national culture is one of them. It was never likely the rest of Europe would choose to become more like Germany, or Germany choose to become more like rest of Europe, on a schedule that would allow the euro to work. And that's what we're finding out.

Published on October 22, 2011 06:28

October 21, 2011

Outro golpe de Dawkins nas religiões

Por Neville Hawcock | Do Financial Times

"Mostre-me a criança e lhe darei o homem", diz a máxima jesuíta. Isso se Richard Dawkins não chegar lá primeiro. O novo livro do ateu-mor, "The Magic of Reality", é elaborado para imunizar de uma vez por todas mentes tenras contra o sobrenatural e seus apologistas.

Na verdade, não só mentes tenras. Embora destinado a crianças de 10 anos para cima, o texto é persuasivo em qualquer idade. Afinal, Dawkins é um popularizador e um proselitista; seu argumento, magnificamente complementado aqui pelas ilustrações ricas de Dave McKean, possui uma clareza maravilhosa.

Ele começa definindo seus termos. "Realidade" é tudo o que pode ser compreendido diretamente por nossos cinco sentidos ou indiretamente por instrumentos e modelos científicos. (As emoções, que podem parecer excluídas por essa definição, também são parte da realidade, dependendo para sua existência de "cérebros... ou algo equivalente a cérebros".) A "mágica" cai em três categorias: mágica sobrenatural, as bobagens dos contos de fadas e mitos (muito ruim, manuseie com cuidado); a mágica de palco, à la "Penn and Teller" (que na maioria das vezes tem uma certa graça); e a mágica poética, quando a natureza nos toca (muito bom, mergulhe nessa).

O propósito de Richard Dawkins é demonstrar que o mundo real, entendido cientificamente, está embebido do tipo de mágica mencionada neste último tópico. "Comparados com a beleza e mágica do mundo real, a magia sobrenatural e os truques de palco parecem baratos e de mau gosto", escreve.

Cada capítulo subsequente consiste de duas partes. Uma abertura curta pergunta, por exemplo, "O que é o sol?", e Dawkins percorre rapidamente vários mitos antigos, sobre Huitzilopochtli [que pode ser traduzido como "Beija-Flor Azul" ou "Beija-Flor Canhoto", que era o deus asteca do Estado e da guerra], Hélio e o "deus tribal de YHWH" [Jeová]

Esses deuses de palha, invocados para ser destruídos por Dawkins, não estão à altura da tarefa de explicar a realidade, mas pelo menos proporcionam ao ilustrador McKean um grande tema. (A divindade tem as melhores ilustrações?) Em seguida, a maior parte do capítulo lida com a questão "O que é o sol de fato?" e Dawkins faz suas exposições.

E ele é muito bom nisso. O capítulo sobre arco-íris apresenta a explicação mais clara, entre todas as que já vi, sobre como eles aparecem, enquanto em "Quem foi, de fato, a primeira pessoa?" faz um enorme uso de uma vasta linha de instantâneos sobre cada um de nossos ancestrais: tudo parece bem com seus bisavós de 4 mil anos; mas com seus bisavós de 50 mil anos, não; e com seus bisavós de 185 milhões de anos - bem, vamos dizer que há algo estranho com ele.

Os dois últimos capítulos tratam mais diretamente das preocupações com as religiões organizadas. "Por que coisas ruins acontecem?" conclui que elas simplesmente acontecem, especialmente quando você é parte de uma cadeia alimentar. Os milagres também não merecem muita consideração. Dawkins elabora o argumento de Hume de que você deve apenas acreditar em relatos de milagres quando a probabilidade de eles realmente terem acontecido é maior que a probabilidade de alguma informação estar sendo transmitida de maneira errada - uma condição que nunca se alcança.

"A verdade", conclui Dawkins na última página, "é mais mágica - no melhor e mais instigante sentido da palavra - do que qualquer mito ou mistério ou milagre fabricados". Ou, conforme Cristo (também conhecido como "um pregador judeu errante chamado Jesus") disse: "A verdade o libertará". (Tradução de Mario Zamarian)

Published on October 21, 2011 08:35

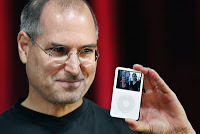

How Steve Jobs Saved the Music Industry

By ED NASH, WSJ

Before iTunes, the stealing of MP3 files was rampant and seemingly unstoppable

As I write this, I am aware that I will undoubtedly take a lot of criticism from fellow music-industry professionals. But it's important to tell the truth and examine the facts dispassionately. And the truth is that Steve Jobs saved the music industry.

In the late 1990s, computer and Internet technology had reached a point that made the transfer of reasonably sized, high-quality MP3 files extremely easy and inexpensive for millions of people. Once that point was reached, the music industry was set on a collision course with modern technology.

In 1999, on the heels of the initial success of peer-to-peer file sharing sites like Napster, lawsuits were filed. But lawsuits would not solve the overwhelming issue: Music had become broadly available online, and access was easy—not to mention free. Sure, it was technically illegal, but the new technology was breaking unprecedented legal ground, and a population that was largely uneducated on intellectual-property law ultimately took advantage of this access. You could say that the downloaders were ignorant opportunists.

The legal brawls would multiply—record labels, publishers, the Recording Industry Association of America, everyone got in on the fight, suing the file-sharing services, suing the college kids in dorm rooms who were utilizing them, even suing the Internet service providers. At various points, injunctions were granted, settlements were offered and accepted, but the sharing continued. The stealing of music was rampant and seemingly unstoppable.

As technological advances continued, the innovations that made this "sharing" possible grew in sophistication. The genie would not go back into the bottle. The lawsuits were costly and cumbersome, and they weren't solving the problem. The music industry wasn't coming up with a viable solution either.

That shouldn't be surprising. After all, the music industry was not equipped for—or even conscious of—the idea of selling directly to the public. The industry was built on the model of creators under contract to labels who push distribution to retailers who ultimately sold product to consumers. The downloading was bypassing the retailers (and in some cases the labels) and going straight into the hands of the consumers, cutting out the traditional distribution chain that existed with physical product like CDs and cassettes.

The problem was clear, but a solution would require nothing short of a paradigm shift in the industry. There would need to be changes in licensing from the major labels, technological implementation, a strong marketing plan and—perhaps most importantly—all delivered at a price that would entice illegal downloaders to pay for music that was already free for the taking.

Steve Jobs presented the answer. Jobs and Apple introduced the iPod and iTunes software in 2001 to marginal success. But the real shift came in 2003 with the launch of the iTunes Store. Jobs not only had a vision, he had a plan—a plan that the music industry was initially reluctant to take part in.

Jobs was intent on a singles-based sales structure with optional pricing for full albums. He determined that 99 cents per single song would be the standard price point—a suggestion that rankled many industry traditionalists. Nonetheless, Jobs eventually negotiated licensing agreements with all of the major labels. Of course in hindsight we see that there were few other options, but to his credit Jobs could already see what was ahead.

In a 2003 interview with Rolling Stone magazine, Jobs spoke openly about the problems that faced the major labels: "When the Internet came along, and Napster came along, they didn't know what to make of it. A lot of these folks didn't use computers—weren't on e-mail; didn't really know what Napster was for a few years. They were pretty doggone slow to react. Matter of fact, they still haven't really reacted, in many ways." Jobs recognized the path that technology was taking and the effect it would continue to have on the music industry and, more importantly, on music itself.

He also understood intellectual property, and this may have been the most important piece of the strategy that saved the music industry. In that same Rolling Stone interview, Jobs said, "If copyright dies, if patents die, if the protection of intellectual property is eroded, then people will stop investing. That hurts everyone. People need to have the incentive that if they invest and succeed, they can make a fair profit. Otherwise, they'll stop investing. But on another level entirely, it's just wrong to steal. Or, let's put it another way: it is corrosive to one's character to steal. We want to provide a legal alternative."

With iTunes, Jobs not only provided a legal alternative but a more convenient alternative. He understood that people would pay 99 cents a song if it were easier than stealing, and of equal importance he understood that the vehicle—the iTunes application itself—would need to be free. And so iTunes didn't just carry Jobs's vision to fulfillment, it created a commercial superhighway that connected the artist to the consumer and rescued the industry.

A true innovator gives the market what it wants before the market knows what it wants. Steve Jobs was a true innovator. The music industry is still refining its models for business and is taking a hell of a long time to let the old models go. But music is being consumed more than ever, songs are delivered faster, and there is more variety at our fingertips than ever before. It is a special time—uncertain, exciting, scary and quite exhilarating in its potential.

I am so thankful that Steve Jobs was a music fan, because he believed that its value was intrinsic when delivered effectively. He showed the music industry how to capture the value that was quickly being eroded by old-world ideals. He developed the technology and then built the marketplace that would allow music creators to communicate value and reap the benefit of their work. It's not the world I imagined when I first entered this business, but in many ways it's better.

Thank you, Steve Jobs, for saving our industry. We owe you one.

Mr. Nash is president of Altius Management in Nashville, Tenn.

Published on October 21, 2011 05:45

Morre o 'irmão' de Lula

[image error]

Rodrigo Constantino, para o Instituto Liberal

As rebeliões árabes contra regimes despóticos avançam um passo com a captura e morte do líder da Líbia, Muamar Kadafi. Ditador cruel, que por mais de 40 anos governou o país sob mão de ferro, Kadafi era um terrorista e mereceu o fim que teve (o que não significa que a democracia virá em seu lugar). Sua morte gerou, entretanto, reações bem diversas mundo afora.

O primeiro-ministro britânico, o conservador David Cameron, celebrou sem meias palavras: "Hoje é um dia para recordar todas as vítimas do coronel Kadafi e as inúmeras pessoas que morreram nas mãos deste brutal ditador e de seu regime". O presidente francês, Nicolas Sarkozy, também comemorou: "O desaparecimento de Muamar Kadafi é um grande passo na luta conduzida há mais de oito meses pelo povo líbio para livrar-se do regime ditatorial e violento imposto durante mais de 40 anos".

Mas nem todos se regozijaram. O fanfarrão "presidente" da Venezuela, Hugo Chávez, disse: "Lembraremos de Kadafi durante toda a vida como um grande lutador, um revolucionário e um mártir". A presidente Dilma foi mais contida. Alegou que não devemos comemorar a morte de nenhum líder (nem mesmo a de Hitler, presidente?). Depois constatou que a Líbia está passando "por um processo de transformação democrática". Confesso que ao ver aqueles guerrilheiros empunhando fuzis, nada me remete ao modelo democrático que defendo.

Mas minha curiosidade é saber a reação do ex-presidente Lula. O que ele está sentindo? O sofrimento deve ser grande, pois certa vez ele se dirigiu ao ditador líbio o chamando de "meu amigo, meu irmão e líder". São estas figuras nefastas os ícones da nossa esquerda "democrática"...

Rodrigo Constantino, para o Instituto Liberal

As rebeliões árabes contra regimes despóticos avançam um passo com a captura e morte do líder da Líbia, Muamar Kadafi. Ditador cruel, que por mais de 40 anos governou o país sob mão de ferro, Kadafi era um terrorista e mereceu o fim que teve (o que não significa que a democracia virá em seu lugar). Sua morte gerou, entretanto, reações bem diversas mundo afora.

O primeiro-ministro britânico, o conservador David Cameron, celebrou sem meias palavras: "Hoje é um dia para recordar todas as vítimas do coronel Kadafi e as inúmeras pessoas que morreram nas mãos deste brutal ditador e de seu regime". O presidente francês, Nicolas Sarkozy, também comemorou: "O desaparecimento de Muamar Kadafi é um grande passo na luta conduzida há mais de oito meses pelo povo líbio para livrar-se do regime ditatorial e violento imposto durante mais de 40 anos".

Mas nem todos se regozijaram. O fanfarrão "presidente" da Venezuela, Hugo Chávez, disse: "Lembraremos de Kadafi durante toda a vida como um grande lutador, um revolucionário e um mártir". A presidente Dilma foi mais contida. Alegou que não devemos comemorar a morte de nenhum líder (nem mesmo a de Hitler, presidente?). Depois constatou que a Líbia está passando "por um processo de transformação democrática". Confesso que ao ver aqueles guerrilheiros empunhando fuzis, nada me remete ao modelo democrático que defendo.

Mas minha curiosidade é saber a reação do ex-presidente Lula. O que ele está sentindo? O sofrimento deve ser grande, pois certa vez ele se dirigiu ao ditador líbio o chamando de "meu amigo, meu irmão e líder". São estas figuras nefastas os ícones da nossa esquerda "democrática"...

Published on October 21, 2011 04:59

October 20, 2011

Jovens e indignados

Rodrigo Constantino, para a revista VOTO

"Um dos tristes sinais de nosso tempo é que nós temos demonizado quem produz, subsidiado aqueles que se recusam a produzir, e canonizado aqueles que se queixam." (Thomas Sowell)

Movimentos de protesto têm se espalhado por vários países. Nos Estados Unidos, o "Tea Party" cresceu de forma impressionante, e agora surgiu o "Ocupar Wall Street", com viés de esquerda. Na Europa, várias passeatas têm ocorrido nos países em crise, sendo as mais violentas na Espanha e agora na Grécia. As inspirações são diferentes em cada caso, mas, em comum, há uma enorme raiva canalizada contra o "sistema". Eles falam em nome dos "excluídos", contra os privilegiados. E pregam o radicalismo.

Muitas demandas e queixas dessa "massa de ressentidos" são legítimas, ainda que seja difícil separar o joio do trigo. Há uma mistura muito grande, e nem sempre coerente, em tais protestos. Sobra ataque ao capitalismo, à globalização, ao setor financeiro, aos governos, enfim, atira-se para muitos lados distintos, mas o diagnóstico não costuma ser preciso. Palavras de ordem e slogans substituem reflexões mais aprofundadas.

Uma crise desta magnitude atual sempre tem inúmeras causas. Devemos evitar a tentação do reducionismo, em busca de bodes expiatórios simples. Sem dúvida há a impressão digital dos governos em todas as cenas de crime. Mas até onde o governo não é um reflexo do povo? Wall Street e os grandes bancos também abusaram, e merecem duras críticas. Mas o abuso não deve tolher o uso, e atacar o sistema financeiro como um todo é estupidez ideológica. Os bancos centrais também erraram feio, e seu papel deve ser revisado. Mas não há panacéia aqui também.

Eis o que eu queria dizer: apesar de conter demandas legítimas e a raiva ser justificável, este clima crescente carrega sementes perigosas para a democracia. A revista britânica "The Economist", que fez uma reportagem de capa sobre o fenômeno, trouxe importante alerta: As pessoas estão certas de estarem com raiva, mas também é certo estar preocupado com onde o populismo pode levar a política. Como dizia Nelson Rodrigues, "a multidão é inumana porque não tem cara".

Literalmente. Basta ver a quantidade de gente mascarada nos protestos. A máscara do conspirador Guy Fawkes, que pretendia explodir o Parlamento inglês no começo do século 17, ganhou o mundo, popularizada pelo filme "V de Vingança". Uma turba revoltada é sempre uma ameaça às liberdades. O ambiente fica fértil para "soluções mágicas". Os oportunistas de plantão vestem o manto de salvador da pátria e oferecem milagres. Este é o maior risco que vejo nesses protestos.

Há um agravante: a quantidade de jovens nas passeatas. O jovem apresenta naturalmente uma tendência maior ao radicalismo e às crenças utópicas. Ele é contra a autoridade por natureza; precisa confrontar o "pai" para estabelecer sua identidade. E, convenhamos, o mundo moderno anda mal das pernas quando se trata de impor limites aos jovens. Pais culpados, que não sabem dizer "não" e tentam ser "coleguinhas" dos filhos, delegando a educação ao estado, este não é um quadro animador.

Mas há um fator mais prosaico que explica parte desta revolta atual: o imenso desemprego entre os jovens. Nos Estados Unidos são mais de 17% de desempregados abaixo de 25 anos. Na União Européia essa taxa fica na média de 20%, sendo que na Espanha chega a impressionantes 46%. Quando quase metade dos jovens procura, mas não encontra emprego, pode ter certeza de que o clima vai esquentar. E os pais destes jovens têm boa parcela de culpa nisso.

As gerações anteriores foram plantando as sementes deste caos atual. Como crianças mimadas, passaram a crer que o estado de abundância é o natural, e que basta exigir do governo seus "direitos" que tudo fica bem. O "welfare state" é a maior evidência de que Bastiat estava certo quando, já em 1850, afirmou que "o estado é a grande ficção pela qual todos tentam viver à custa de todos".

Para os jovens, este modelo é especialmente cruel, pois cria inúmeras barreiras ao mercado de trabalho, visando à "proteção" dos trabalhadores (aqueles já empregados). Um salário mínimo, por exemplo, vai prejudicar justamente os jovens menos produtivos, que aceitariam ganhar salário menor nesta fase da vida, mas são impedidos pelo governo. O elevado desemprego dos jovens é apenas mais uma conseqüência não-intencional das bandeiras altruístas de esquerda.

Ninguém sabe como esta revolta toda vai acabar, nem tenho bola de cristal para tentar prever. Pode ser que em alguns casos ela leve a reformas decentes; pode ser que em outros casos leve ao despotismo, após uma fase mais anárquica. Ainda é cedo para dizer. Mas, o que podemos adiantar é que épocas que combinam elevada deterioração de valores morais com ampla crise econômica costumam ser explosivas.

Quando vejo milhões de jovens indignados tomando as ruas do mundo todo, confesso que tenho calafrios. Fecho com Nelson Rodrigues, uma vez mais: "Esse misterioso 'jovem', vago, difuso, impessoal, sem cara, sem caráter, só me convence como um monstro".

Published on October 20, 2011 15:43

Rage against the machine

The Economist

People are right to be angry. But it is also right to be worried about where populism could take politics

FROM Seattle to Sydney, protesters have taken to the streets. Whether they are inspired by the Occupy Wall Street movement in New York or by the indignados in Madrid, they burn with dissatisfaction about the state of the economy, about the unfair way that the poor are paying for the sins of rich bankers, and in some cases about capitalism itself.

In the past it was easy for Western politicians and economic liberals to dismiss such outpourings of fury as a misguided fringe. In Seattle, for instance, the last big protests (against the World Trade Organisation, in 1999) looked mindless. If they had a goal, it was selfish—an attempt to impoverish the emerging world through protectionism. This time too, some things are familiar: the odd bit of violence, a lot of incoherent ranting and plenty of inconsistency (see article). The protesters have different aims in different countries. Higher taxes for the rich and a loathing of financiers is the closest thing to a common denominator, though in America polls show that popular rage against government eclipses that against Wall Street.

Yet even if the protests are small and muddled, it is dangerous to dismiss the broader rage that exists across the West. There are legitimate deep-seated grievances. Young people—and not just those on the streets—are likely to face higher taxes, less generous benefits and longer working lives than their parents. More immediately, houses are expensive, credit hard to get and jobs scarce—not just in old manufacturing industries but in the ritzier services that attract increasingly debt-laden graduates. In America 17.1% of those below 25 are out of work. Across the European Union, youth unemployment averages 20.9%. In Spain it is a staggering 46.2%. Only in Germany, the Netherlands and Austria is the rate in single digits.

It is not just the young who feel squeezed. The middle-aged face falling real wages and diminished pension rights. And the elderly are seeing inflation eat away the value of their savings; in Britain prices are rising by 5.2% but bank deposits yield less than 1%. In the meantime, bankers are back to huge bonuses.

History, misery and protest

To the man-in-the-street, all this smacks of a system that has failed. Neither of the main Western models has much political credit at the moment. European social democracy promised voters benefits that societies can no longer afford. The Anglo-Saxon model claimed that free markets would create prosperity; many voters feel instead that they got a series of debt-fuelled asset bubbles and an economy that was rigged in favour of a financial elite, who took all the proceeds in the good times and then left everybody else with no alternative other than to bail them out. To use one of the protesters' better slogans, the 1% have gained at the expense of the 99%.

If the grievances are more legitimate and broader than previous rages against the machine, then the dangers are also greater. Populist anger, especially if it has no coherent agenda, can go anywhere in times of want. The 1930s provided the most terrifying example. A more recent (and less frightening) case study is the tea party. The justified fury of America's striving middle classes against a cumbersome state has in practice translated into a form of obstructive nihilism: nothing to do with taxes can get through Washington, including tax reform.

Worryingly, politicians are already in something of a funk. The Republicans first denounced the occupiers of Wall Street, then cuddled up to them. Across Europe social democratic parties have tended to lose elections if they move too far from the centre ground, but leaders, like Ed Miliband in Britain and François Hollande in France (see article), still find the anti-banker rhetoric enticing. Why not opt for a gesture—tariffs, a supertax on the rich—that may only make matters worse? A struggling Barack Obama, who has already flirted with class warfare and business-bashing, might well consider dragging China and its currency into the fray. And it will get worse: austerity and protest have always gone together (see article).

Tackle the causes, not the symptoms

Braver politicians would focus on two things. The first is tackling the causes of the rage speedily. Above all that means doing more to get their economies moving again. A credible solution to the euro crisis would be a huge start. More generally, focus on policies that boost economic growth: trade less austerity in the short term for medium-term adjustments, such as a higher retirement age. Make sure the rich pay their share, but in a way that makes economic sense: you can boost the tax take from the wealthy by eliminating loopholes while simultaneously lowering marginal rates. Reform finance vigorously. "Move to Basel 3 and higher capital requirements" is not a catchy slogan, but it would do far more to shrink bonuses on Wall Street than most of the ideas echoing across from Zuccotti Park.

The second is telling the truth—especially about what went wrong. The biggest danger is that legitimate criticisms of the excesses of finance risk turning into an unwarranted assault on the whole of globalisation. It is worth remembering that the epicentre of the 2008 disaster was American property, hardly a free market undistorted by government. For all the financiers' faults ("too big to fail", the excessive use of derivatives and the rest of it), the huge hole in most governments' finances stems less from bank bail-outs than from politicians spending too much in the boom and making promises to do with pensions and health care they never could keep. Look behind much of the current misery—from high food prices to the lack of jobs for young Spaniards—and it has less to do with the rise of the emerging world than with state interference.

Global integration has its costs. It will put ever more pressure on Westerners, skilled as well as unskilled. But by any measure the benefits enormously outweigh those costs, and virtually all the ways to create jobs come from opening up economies, not following the protesters' instincts. Western governments have failed their citizens once; building more barriers to stop goods, ideas, capital and people crossing borders would be a far greater mistake. To the extent that the protests are the first blast in a much longer, broader battle, this newspaper is firmly on the side of openness and freedom.

Published on October 20, 2011 11:47

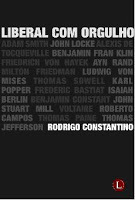

Save the date: lançamento do meu novo livro

Dia 29/11/2011, no Rio.

Do site da editora: Coletânea de artigos sobre economia e política, o livro do Rodrigo Constantino, colunista do Globo, tem apresentação de economistas e empresários, como: Gustavo Franco, Jorge Gerdau, Indio da Costa, Paulo Guedes e Antenor Barros Leal. Além de alguns artigos inéditos, a edição contém textos publicados em: O GLOBO, Revista VOTO, Revista Banco de Ideias (Instituto Liberal), OrdemLivre.org, Revista Amanhã, Instituto Mises Brasil, Instituto Millenium, Ratio Pro Libertas. Os principais temas são: a morte da oposição, Israel, Che Guevara, a volta da inflação, o sistema de cotas.

Published on October 20, 2011 10:37

A ineficiência econômica do racismo

Rodrigo Constantino, para a revista Banco de Idéias - IL

O racismo é ineficiente do ponto de vista econômico. O livre mercado, ao contrário da alocação de recursos pela via política, é do interesse das minorias normalmente discriminadas. Essa é a tese que Walter Williams defende em "Race & Economics" (Hoover Institution Press, 2011). Para sustentar seu ponto, o autor utiliza argumentos teóricos, assim como vários casos empíricos.

A teoria econômica não pode responder questões éticas; mas pode mostrar as conseqüências de medidas tomadas em seu nome. Williams alega que as políticas econômicas necessitam de análises desapaixonadas. Afinal, os efeitos muitas vezes não guardam relação alguma com as intenções iniciais. Esse é justamente um caso comum quando se trata de políticas para combater o racismo ou ajudar minorias.

O que o autor mostra no livro é que diversos problemas que os negros americanos enfrentam não têm ligação com a discriminação racial. Ele não nega que tal discriminação existe; apenas demonstra que as principais causas dos problemas estão em outro lugar. E quais seriam estas causas então? O que fica evidente ao longo do livro é que as regulamentações do governo representam o grande vilão dos negros, especialmente os mais pobres.

Williams volta aos tempos da escravidão, para mostrar que muitos negros já praticavam trocas comerciais, a despeito de proibições legais. Alguns desses "quase livres" chegaram a prosperar. Após a abolição, a competição por empregos aumentou ainda mais, e vários negros estavam conseguindo trabalho no lugar de brancos. Como reação, vários trabalhadores se juntaram em sindicatos na tentativa de criar restrições aos negros. Os principais líderes negros da época entenderam isso e foram contra esses sindicatos.

Após a Grande Depressão, as restrições se intensificaram com o New Deal. Várias medidas foram adotadas pelo governo, impondo barreiras ao mercado de trabalho: salário mínimo; licenças; uma qualificação mínima, muitas vezes sem nenhum nexo com o trabalho efetuado (um eletricista deve saber sobre astecas?). Estas medidas prejudicaram principalmente os trabalhadores com menor produtividade ou conhecimento, que eram, na maioria dos casos, os negros recém-libertos.

Uma das formas básicas de alguém com menor produtividade competir no mercado de trabalho é justamente aceitar um salário menor. A demanda por salários equivalentes para trabalhos equivalentes veio de quem já estava empregado e desejava reduzir a concorrência. O autor mostra inclusive que esta lógica não escapou aos principais proponentes das leis trabalhistas. Os sindicatos se uniram para impedir a entrada maciça dos negros no mercado de trabalho.

Estas leis tornam o custo da discriminação racial nulo. No livre mercado, se o empregador se recusar a contratar alguém por causa da "raça", ele pagará um preço por isso, seja por limitar a quantidade de candidatos às vagas, seja por deixar de empregar gente mais produtiva pelo mesmo salário. Neste caso, basta o concorrente ignorar o racismo para ser mais eficiente. Com o tempo, a tendência é o empregador racista ir à bancarrota.

Outra arma utilizada pelos sindicatos eram as greves, para pressionar as empresas por maiores salários. Os negros ficaram conhecidos como "fura greves", pois muitos, afastados dos sindicatos, estavam dispostos a trabalhar nas condições anteriores. Tiveram várias ocorrências de atos violentos de brancos contra negros, incluindo vítimas fatais. Era mais um caso de intervenção no livre funcionamento dos mercados com o objetivo de prejudicar os negros.

Em suma, Williams defende o fim das restrições legais ao mercado de trabalho como melhor medida para ajudar as minorias, incluindo os negros. O livre mercado é impessoal e foca nos resultados. Esta é a mais poderosa arma contra o racismo.

O racismo é ineficiente do ponto de vista econômico. O livre mercado, ao contrário da alocação de recursos pela via política, é do interesse das minorias normalmente discriminadas. Essa é a tese que Walter Williams defende em "Race & Economics" (Hoover Institution Press, 2011). Para sustentar seu ponto, o autor utiliza argumentos teóricos, assim como vários casos empíricos.

A teoria econômica não pode responder questões éticas; mas pode mostrar as conseqüências de medidas tomadas em seu nome. Williams alega que as políticas econômicas necessitam de análises desapaixonadas. Afinal, os efeitos muitas vezes não guardam relação alguma com as intenções iniciais. Esse é justamente um caso comum quando se trata de políticas para combater o racismo ou ajudar minorias.

O que o autor mostra no livro é que diversos problemas que os negros americanos enfrentam não têm ligação com a discriminação racial. Ele não nega que tal discriminação existe; apenas demonstra que as principais causas dos problemas estão em outro lugar. E quais seriam estas causas então? O que fica evidente ao longo do livro é que as regulamentações do governo representam o grande vilão dos negros, especialmente os mais pobres.

Williams volta aos tempos da escravidão, para mostrar que muitos negros já praticavam trocas comerciais, a despeito de proibições legais. Alguns desses "quase livres" chegaram a prosperar. Após a abolição, a competição por empregos aumentou ainda mais, e vários negros estavam conseguindo trabalho no lugar de brancos. Como reação, vários trabalhadores se juntaram em sindicatos na tentativa de criar restrições aos negros. Os principais líderes negros da época entenderam isso e foram contra esses sindicatos.

Após a Grande Depressão, as restrições se intensificaram com o New Deal. Várias medidas foram adotadas pelo governo, impondo barreiras ao mercado de trabalho: salário mínimo; licenças; uma qualificação mínima, muitas vezes sem nenhum nexo com o trabalho efetuado (um eletricista deve saber sobre astecas?). Estas medidas prejudicaram principalmente os trabalhadores com menor produtividade ou conhecimento, que eram, na maioria dos casos, os negros recém-libertos.

Uma das formas básicas de alguém com menor produtividade competir no mercado de trabalho é justamente aceitar um salário menor. A demanda por salários equivalentes para trabalhos equivalentes veio de quem já estava empregado e desejava reduzir a concorrência. O autor mostra inclusive que esta lógica não escapou aos principais proponentes das leis trabalhistas. Os sindicatos se uniram para impedir a entrada maciça dos negros no mercado de trabalho.

Estas leis tornam o custo da discriminação racial nulo. No livre mercado, se o empregador se recusar a contratar alguém por causa da "raça", ele pagará um preço por isso, seja por limitar a quantidade de candidatos às vagas, seja por deixar de empregar gente mais produtiva pelo mesmo salário. Neste caso, basta o concorrente ignorar o racismo para ser mais eficiente. Com o tempo, a tendência é o empregador racista ir à bancarrota.

Outra arma utilizada pelos sindicatos eram as greves, para pressionar as empresas por maiores salários. Os negros ficaram conhecidos como "fura greves", pois muitos, afastados dos sindicatos, estavam dispostos a trabalhar nas condições anteriores. Tiveram várias ocorrências de atos violentos de brancos contra negros, incluindo vítimas fatais. Era mais um caso de intervenção no livre funcionamento dos mercados com o objetivo de prejudicar os negros.

Em suma, Williams defende o fim das restrições legais ao mercado de trabalho como melhor medida para ajudar as minorias, incluindo os negros. O livre mercado é impessoal e foca nos resultados. Esta é a mais poderosa arma contra o racismo.

Published on October 20, 2011 04:13

Rodrigo Constantino's Blog

- Rodrigo Constantino's profile

- 32 followers

Rodrigo Constantino isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.