Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 125

June 14, 2017

LIBERATION: Bruno Le Maire dans les pas de Yánis Varoufákis?

Le ministre de l’Economie va proposer une indexation du remboursement de la dette grecque en fonction de la croissance du pays.

Neuf thérapies en forme d’austérité budgétaire, trois plans d’aides, un changement de gouvernement et, au bout du compte, un énorme fiasco. Malgré l’obstination de la «troïka» (BCE, FMI et Commission européenne), qui n’a cessé d’imposer (le pistolet sur la tempe) à Athènes des politiques d’austérité aussi impopulaires qu’inefficaces, le constat est sans appel : la Grèce reste sur une trajectoire qui peut se résumer par deux courbes qui, après s’être croisées en 2008, n’en finissent plus de s’éloigner.

D’un côté celle du PIB, qui a chuté de près de 28 % depuis 2010. De l’autre, une courbe ascendante qui mesure un stock de dette publique toujours plus gros. Cette dernière représente aujourd’hui près de 180 % du PIB (326,5 milliards d’euros). Malgré les abandons de créances privées (100 milliards). Compliqué d’affirmer que «l’austérité c’est dur, mais [que] ça finit par payer».

Ironie.Le mantra : quand on doit de l’argent, on rembourse intégralement. Pas question d’annuler tout ou partie de la dette grecque. Ça passe ou ça casse ? «Ni l’un ni l’autre», assure-t-on dans l’entourage du ministre de l’Economie, Bruno Le Maire. Il a fait le tour des grandes capitales pour proposer ses bons offices. Et en premier lieu à Athènes qui n’est, à en croire Bercy, pas contre une idée que plaidera ce jeudi à Luxembourg Bruno Le Maire. Sa proposition : qu’Athènes puisse rembourser sa dette, mais en fonction de sa croissance. «Avec notre proposition, on pourrait avoir des années sans remboursement si la croissance est jugée trop faible. En revanche, nous dirons aux ministres de l’Eurogroupe que ces remboursements seront plus élevés lors de meilleures années», explique-t-on à Bercy.

Ironie du sort, Yánis Varoufákis avait fait la même proposition. C’était en 2015, il était alors ministre des Finances et se disait disposé à repousser des promesses électorales. «Nous voulons rembourser notre dette jusqu’au bout, assurait-il. Mais nous demandons à nos partenaires de nous aider pour relancer la croissance en Grèce. Plus rapide sera la stabilisation de notre économie, plus rapide sera le rythme de notre remboursement.» Varoufákis expliquait que son idée était de «convertir la dette en des obligations indexées sur le taux de croissance. Plus la Grèce se redresse, plus elle se trouve en condition de rembourser les prêts». Réponse : un non catégorique.

Remise au goût du jour par Bruno Le Maire, l’idée s’accompagne cette fois d’une proposition de rééchelonnement. «Tout le monde sait qu’on n’échappera pas à un rééchelonnement de la dette», confie-t-on à Bercy. Certains allant jusqu’à évoquer un calendrier de remboursement dont le terme se situerait aux alentours de 2060-2070. Une éternité pour les Grecs. Reste, si Paris parvient à convaincre ses partenaires, à aplanir un différend entre le FMI et les pays de la zone euro. Christine Lagarde estime que la dette grecque est insoutenable et plaide pour son allégement. Mais allégement ne veut pas dire annulation. Pour la patronne du FMI, la Commission européenne fait preuve d’un trop grand optimisme dès lors qu’il s’agit de réaliser des prévisions de croissance de la Grèce. Et c’est cette question des prévisions de taux de croissance de la Grèce qui risque de bloquer les discussions. Pas question de mettre la main au portefeuille pour le FMI si la dette d’un pays est jugée insoutenable, comme le prévoient ses règles.

Cassandre.Le Fonds avait mis de l’eau dans son vin orthodoxe en reconnaissant avoir sous-estimé les effets récessifs des coupes budgétaires sur la croissance grecque. Mais pas question de lâcher sur l’éventualité d’une annulation, partielle ou totale de la dette. Le FMI, comme l’UE, reformateront-ils leur logiciel à l’avenir ? Ce ne serait pourtant pas le drame annoncé par trop de Cassandre. Et cela tordrait le cou à des idées reçues. Comme celle martelée par le ministre de l’Economie Michel Sapin en février 2015 : «Pas question de transférer le poids de la dette grecque du contribuable grec au contribuable français»… Et d’assurer que l’ardoise serait de «735 euros par Français». Certes, la France est engagée à hauteur de 40 milliards par rapport à la Grèce. Mais c’est oublier qu’une petite partie lui a été prêtée dans le cadre de prêts bilatéraux. Le reste ? Une trentaine de milliards apportés par le biais du Fonds européen de stabilité financière qui a emprunté sur les marchés financiers avec la garantie de l’Etat français pour prêter, ensuite, à Athènes. Et dans les deux cas, les prêts sont déjà comptabilisés dans la dette publique française (environ 2 000 milliards). Leur annulation n’augmenterait donc en rien la dette française.

der Freitag: Eine neue Partei für Europa

Eine neue Partei für Europa

Eine neue Partei für EuropaDiEM 25 Ein radikales und zugleich seriöses Programm, gute Leute, ökonomische Expertise: Wird Yanis Varoufakis’ Bewegung zur Konkurrenz für die Linke in Deutschland?

„Ein anderes Europa ist möglich“: Dafür kämpfen viele, aber bisher noch keine transnationale Partei

Löscht eure Paypal-Konten und helft, das Monopol privater Finanzkonzerne über Europas Zahlungsverkehr zu brechen! Der Bewegung DiEM 25 mangelt es weder an Kreativität noch an Konkretion: ein öffentliches digitales Gratis-Bezahlsystem für ganz Europa, das ist einer von vielen, vielen Vorschlägen aus dem 100 Seiten zählenden Programm. Keine Sorge, es gibt Kurzfassungen. Die wird DiEM 25 brauchen auf dem Weg, den Mitgründer Yanis Varoufakis vergangene Woche in Berlin verkündete: hin zur ersten paneuropäischen Partei, rauf auf die Stimmzettel bei der Wahl zum Europaparlament 2019. Dieser Weg wird steinig.

Zuerst gilt es, die europaweit 60.000 Mitglieder starke Basis von der Transformation zu überzeugen. Dann soll aus der richtigen Euro-Fehleranalyse, den radikalen, aber keineswegs utopischen Reformvorschlägen sowie den so prominent wie progressiv besetzten Gremien eine Wahlalternative werden. Und schließlich muss Europas Demokratiedefizit überwunden werden, wofür das Parlament keines bleiben darf, dem eigene Gesetzesinitiativen verwehrt sind wie heute.

Wer all das als Träumereien abtut und sich lieber für eine Rückkehr zu starken Nationalstaaten in Stellung bringt, ist bei DiEM 25 falsch. Sich von mutmaßlichen EU-Aussteigern in der hiesigen Linkspartei abzusetzen und Konkurrenz an den Urnen zu erwägen, wie es Varoufakis tat, macht Sinn – zum Zwecke der Profilierung als transnationale Partei, die sich Marxisten, Liberalen wie Sozialdemokraten empfehlen will. Und wem Sahra Wagenknechts Rede vom verwirkten Gastrecht immer noch in den Ohren dröhnt, der bekommt hiermit eine interessante Alternative. Eine, die sich zudem von Initiativen wie Pulse of Europe differenziert, indem sie nicht im pro-europäischen Affekt verharrt, sondern sowohl ökonomische Expertise als auch seriöse Ideen zu bieten imstande ist.

Das beides wiederum kann mit Recht auch die Linke für sich proklamieren, aus deren Umfeld noch dazu die einzigen bekannten Köpfe von DiEM 25 hierzulande kommen, Parteichefin Katja Kipping in erster Linie. Am Ende wird mit DiEM 25 wohl kaum eine neue linke Kraft im parlamentarischen Spektrum Deutschlands erwachsen. Sondern im besten Falle ein kritischer Impulsgeber für die Linke – und ein Bündnispartner an den Wahlurnen.

June 13, 2017

June 12, 2017

ΤΟ ΔΙΣΤΟΜΟ ΚΑΙ ΤΟ ΚΑΘΗΚΟΝ ΤΗΣ ΑΡΙΣΤΕΡΑΣ: Γιατί το DiEM25 αντιτίθεται στον αντι-γερμανισμό

Η Χάνα Αρέντ, πολύ σωστά, είχε πει ότι ακόμα και ένας μόνο γερμανός να είχε δολοφονηθεί στο Άουσβιτς λόγω της αντίστασής του στους ναζί (και είχαν δολοφονηθεί πολλοί), οι γερμανοί δεν φέρουν, ως λαός, συλλογική ευθύνη για τον ναζισμό.

Από τότε που ξέσπαγε η παγκόσμια οικονομική κρίση, το 2008, κάποιοι ανησυχούσαμε μεγαλοφώνως ότι, δεδομένης της σαθρής δόμησης της ευρωζώνης, πολύ σύντομα η κρίση θα έστρεφε τον έναν περήφανο λαό εναντίον άλλων περήφανων λαών στην ήπειρό μας – μέγιστη νίκη της μισαλλοδοξίας, του ρατσισμού και, βέβαια, της ιδεολογίας του εθνικοσοσιαλισμού.

Όταν, τον Γενάρη του 2015, ο ελληνικός λαός εξέλεξε μια κυβέρνηση στην οποία έδωσε την εντολή να αποτινάξει τον ζυγό της χρεοδουλοπαροικίας, η εντολή εκείνη δεν ήταν αντι-γερμανική. Ήταν εντολή εναντίον των δυνάμεων εκείνων, ιδίως του τραπεζικού τομέα (της Πτωχοτραπεζοκρατίας, όπως ονομάζω το μετά το 2008 καπιταλιστικό καθεστώς), που αρχικά μεγιστοποίησαν την εκμετάλλευση των γερμανών εργαζόμενων πτωχών και έτσι δημιουργούσαν τις συνθήκες για την καταστροφή των ονείρων, της αξιοπρέπειας και της ελπίδας της πλειοψηφίας των ελλήνων, των ισπανών, των ιταλών. Αλίμονο αν οι ίδιες δυνάμεις κατάφερναν να στρέψουν τους έλληνες εργαζόμενους, τους έλληνες προοδευτικούς εναντίον των γερμανών συντρόφων τους.

Ένα χρόνο αργότερα, μετά τον στραγγαλισμό της Ελληνικής Άνοιξης από το Βαθύ Κατεστημένο της Ευρώπης και την ελληνική ολιγαρχία, ιδρύσαμε το DiEM25 στο Βερολίνο. Δεκάδες χιλιάδες τα μέλη μας στην Γερμανία, με τους οποίους από τότε βαδίζουμε μαζί, χέρι-χέρι, δίπλα-δίπλα, καθημερινά αγωνιζόμενοι εναντίον τόσο του Βαθέως Κατεστημένου όσο και εναντίον του εθνικισμού, δεξιού και «αριστερού».

Με αυτές τις σκέψεις κατά νου, δεν μπορούμε παρά να χαιρόμαστε βαθειά κι εμείς, παρά τις διαφωνίες μας με την κυβέρνηση που εκπροσωπεί στην χώρα μας, που ο γερμανός πρέσβυς πήγε στο Δίστομο να καταθέσει στεφάνι στο μνημείο των δολοφονημένων από τους ναζί. Δεν μπορούμε παρά να χαιρετίσουμε την στάση του Μανώλη Γλέζου στο Δίστομο και να στηλιτεύσουμε την προσπάθεια αναγωγής του νέου απελευθερωτικού αγώνα των ελλήνων, των πορτογάλλων, των ιταλών αλλά, ναι, και των γερμανών συντρόφων μας σε μέτωπο εναντίον της Γερμανίας και του γερμανικού λαού.

Όπως συνηθίζουμε να λέμε στο DiEM25, ο «αριστερός» εθνικισμός είναι η χειρότερη αντίδραση τόσο στον εθνικοσοσιαλισμό όσο και στην τρόικα.

What lies behind the euro crisis, Brexit & Trump: Keynote at the FundForum International, Berlin & a discussion with Megan Greene

Keynote at the FundForum International conference in Berlin, 12th June 2017. Followed by a discussion with Megan Greene.

On Documenta 14, Athens – in conversation with iLiana Fokianaki, Art Agenda

“We Come Bearing Gifts”—iLiana Fokianaki and Yanis Varoufakis on Documenta 14 Athens

Created in 1955 by artist and curator Arnold Bode, Documenta sought to advance the cultural reconstruction of Germany within the postwar European order. Reoccurring every five years, it has since unfolded into a periodic forum for contemporary art. When Adam Szymczyk was appointed artistic director of Documenta 14 in November 2013, he proposed calling the exhibition “Learning From Athens,” opening it first in the Greek capital and then in its traditional home in Kassel. Four years later, with the Greek exhibition now underway and the German edition about to open, iLiana Fokianaki and Yanis Varoufakis share their views on the show, its development, and its implications.

iLiana Fokianaki: In the beginning, when it was first announced that Documenta 14 would be held in Athens, I believed there was a purpose to the experiment. How would a rigid institution be transformed by its curatorial team living and operating in a city of crisis? I thought that the moment one performs such a “move” there must be a particular reasoning behind the relocation, as well as the selection of the location. Two years later, and with the exhibition now open, I am still unable to answer the question of “why Athens?” At the same time, I am starting to feel numb towards what has been presented as a mutually beneficial idea for both guests and hosts, maybe even more beneficial for the Athenian hosts.

Yanis Varoufakis: To begin with there is a sinister parallel with privatization. In 2015, fourteen regional airports, extremely lucrative ones as Santorini, Mykonos, and so on, were sold to one German majority state-owned company as part of the Troika’s privatization drive. Recall that privatization became all the rage in Europe with Margaret Thatcher. Yet Thatcher would have never approved this kind of privatization. Why? Because her argument for privatization was that it enhances competition. Well, you do not enhance competition when you give all the airports to one company; this is enhancing monopoly!

So from a neoliberal point of view this was not a neoliberal privatization. And let’s not forget that we’re talking about Fraport, a state-owned company. Effectively, the Greek regional airports were nationalized, but by a different nation! And let’s take a look at who paid for this privatization/nationalization: the announced price was 1.2 billion euros, which was presented as an influx of capital into cash-starved Greece. But Fraport purchased these airports with loans from Greek banks, which were either recapitalized by the Greek citizens or guaranteed by the Greek state. So it’s like me coming to buy your house, but having you pay for it. Or, rather, making you guarantee the loans I get from the banks, in order that I can pay you for your house. If I fail to repay them, you’ll act as my guarantor. You would laugh if I proposed this to you. It is nothing short of preposterous! But in Greece and in the EU this is presented as substantial privatization, as a gain for the country and proof that Greece is being normalized. Yes it is normalized, but as something worse than a colony.

I gave the example of Fraport because we have a similar phenomenon with Documenta. Documenta supposedly came to Greece to spend, but instead they sucked up every single resource available for the local art scene. The few resources that Greece’s private and public sectors make available to Greek artists, like the Aegean Airways sponsorship, went to Documenta. The Athens municipality gave Documenta a building for free. Many hotels donated rooms for free. Buildings at the Athens School of Fine Arts were made available for free, and now the graduating students have nowhere to host their degree show. The National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens (EMST) did charge Documenta, but the amount was ludicrously small—a token. And, as Greece’s private and public sectors were handing out all the resources normally available to Greek artists and art institutions to Documenta, its artistic director had the audacity to say out loud that he is not interested in the local art scene but is only interested in Athens. This mindset and practice transposes the Fraport mindset and practice from the world of airports to the art world.

Documenta did bring some resources from Germany but, overall, it has been an extractive process. Documenta took a great deal more from Athens—from both its private and public sector—than it gave. Adding the veneer of a left-wing narrative against neoliberalism to a purely extractive neocolonial project that’s framed as a gift to Greece is adding insult to injury.

iF: This is why the analysis of the institution, the power relations it embodies, and the theoretical proposition it offers interest me more than the exhibition itself. Primarily, a well-branded German cultural institution like Documenta represents the imperium, but also capital, since inclusion in such a show adds commodity value to the artwork. This creates a dynamic that is, a priori, not neutral. So to look at it through the current political spectrum of the EU: a politically, financially, and socially charged binary is created by deciding to bring this German institution to, not just any financial periphery, but to the very periphery that embodies the other half of this binary: Greece. Not to mention the Second World War, which makes it a historically charged binary as well.

So the institution carries an exhibition with a mandate. And the exhibition denies (or chooses to ignore) this binary. Through this exhibition, the institution claims that we are amidst a political and economic war, manifested in Greece’s referendum and the bodies that filled the streets, events that deeply influenced this edition of Documenta. It claims to offer a public service to its audiences. To quote Paul Preciado:

One of the difficulties (and beauties) of making this exhibition was the decision of its artistic director, Adam Szymczyk, to collaborate only with public institutions in Athens. In conditions of war, the institutional interlocutor of the exhibition can be neither the establishment, nor galleries, nor the art market. On the contrary, the exhibition is understood as a public service, as an antidote against economic, political, and moral austerity.(1)

However, anyone who lives in Greece today is aware that the notion of a public service is a joke—and by extension, the establishment itself. As is the notion that the state-funded institution, as a physical space or even as a metaphor, can be an antidote to economic, political, and moral austerity. Any mildly progressive Greek will tell you that the public services represent and promote these austerities, under the umbrella and the absolute fetish of a national identity. A national identity that has been built by fetishizing ancient Greece. I found references to this glorified past—“the origin of civilization”—in many of the opening speeches and curatorial texts, but also in some of the works. It reminded me vividly of the eighteenth-century Grand Tour, with all the Anglo-Saxons coming to Italy and Greece to find the roots of Western civilization, doe-eyed and in awe of the ancient ruins.

On the other hand, if you examine the idea of “a public service” as a gift, then we are talking about a blind spot—coming from, hopefully, good intentions. But, as we know, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Because in fact claiming that you are offering a service (as a gift), when operating from within a mega-institution, positions you immediately as a benefactor. Even more so when this institution represents all that we have described above. Adding into the mix the veneer of a left-wing narrative against neoliberalism makes it even more problematic. What valid political claims can we actually make as cultural practitioners when operating within, and being fed by, a capitalist structure with very well-defined power structures and power centers, in terms of enabling discourses and artworks? A performative element of a left-wing narrative was also quite apparent in the decision to situate the Documenta team in Exarcheia, which is known as an anarchist neighborhood.

YV: There is nothing new to that, and we know this well. Near the coast of Attica there is an awful island called Makronisos, an island of exile on which thousands were tortured and many died during the 1940s civil war. There are tourist trips now to Makronisos, which even offer an inmate’s menu. I have no doubt that there is a lot of demand for this type of tourism, where you get embedded into the context of others’ suffering. In Brazil they also have “favela tours,” as I think they call them, in which tourists experience “life in the favela.” This is not too different from how most Greeks see Documenta 14. They see how art tourists, including the Documenta curators, come to live in their disaster zone for a while, smell the Exarcheia smells and hear its sounds, before catching their free Aegean Airways flights to Kassel to do their proper business.

iF: Greece differs from all the countries of the European south, since it is the only one with no heavy industry, and this has also contributed to the crisis. It is also a country with a political history of constant upheaval, with the shortest history of modern democracy in the European Union (from 1974)—elements that very much explain its failure to achieve the financial stability and prosperity of other countries that entered the EU in the 1980s.

Since the reinstatement of the Greek state in 1821, Greece has been under the wing of the Franco-German axis, with a German king appointed, with the tragedy of Asia Minor in the 1920s where the French, the English, and the Russians meddled in the conflict with Turkey, then a dictatorship that ended during the Second World War, and then the civil war that lasted until 1949, induced by the British, who had a stronghold in the country and basically did not want the Communist wave to spread down to the south. After the Communists were expelled from the country, murdered, or sent to concentration camps, the conservatives—amongst them former collaborators of the Nazis—ruled with some help from far-right-wing paramilitary groups that murdered politicians such as Nikos Beloyiannis, who was immortalized in a Picasso sketch of the time, and Grigoris Lambrakis, whose story is portrayed in Costa-Gavras’s 1969 film Z. And then after such a turbulent political ride, we ended up with a second dictatorship in 1967, which gave birth to what today is the neofascist party Golden Dawn. Since the reinstatement of democracy in 1974, we have tried to generate a healthy economy through a corrupt political system, through a supposedly socialist government that undertook a failed project and built a maze of bureaucracy. Instead, we ended up with the 2004 Olympic Games, which brought to the surface a somewhat “hidden” financial crisis, which accelerated in 2009 and is still deepening. This is the backdrop against which the announcement of Documenta 14 in Athens was received with intense criticism but also praise. During the press conference, Documenta’s CEO Annette Kulenkampff called the exhibition a gift to Greece.

YV: No gift to Greece from Germany is possible. Full stop. Ever! Why? Any sentences that begin with “Germany does X” or “Germany gives X” or “Germany takes X” are wrong and the thin edge of the racist wedge. Because there is no such thing as an anthropomorphic Germany (or Greece for that matter, or France) that can act, give, or take away. There are many, many Germanies. There is Wolfgang Schäuble’s Germany, the Germany of German DiEM25 members,(2) the Germany of working-poor Germans, of German bankers, etc. So that statement by the CEO of Documenta should be further interrogated with questions such as: “Which Germany? The German state? German capital? Particular donors?” There are many interests that feed Documenta financially.(3) So I would need a clarification as to what type of gift. Otherwise, I find the statement offensive and inaccurate. If the gift came from Schäuble, for example, let’s remind Kulenkampff that Schäuble got a huge gift from Greece, because over the last five to six years Germany—the federal state of Germany—has been borrowing from the markets at zero percent interest, whereas it should be 3 percent. This amounts to hundreds of billions of euros, and this is due to the Greek crisis, which forced the European Central Bank to push the interest to negative or zero rates, and the savings to the German federal government from the Greek crisis are stupendous. So if we want to do a proper accounting as to who is gifting whom, let’s do it, but let’s not come up with insupportable generalized inaccuracies.

iF: There are of course the complaints by the locals, accusing Documenta’s artistic director of not involving the Greek art scene, not representing it, not consulting it.

YV: I disagree. I don’t believe they had any obligation to consult anyone. I am an internationalist. I don’t believe in borders. I don’t believe Athens belongs to the Athenians exclusively and that anyone from Kassel or Venice or New York needs to get permission from the Greek authorities or local art scene to be here. I do not even believe this is necessary even as a gesture of courtesy. I do not believe in these mechanisms by which one secures legitimacy to do things in any European country. If this were so, DiEM25 would not have come into existence. We inaugurated DiEM25 in Berlin without the permission of anyone in Germany, except of course our German comrades. I don’t think we had any obligation at all to get permission from the local authorities to be there and present our ideas.

My problem is not that Documenta did not contact Greek society through official or unofficial channels. I am quite happy when people, of their own volition, decide they want to come over to Athens and do things. My criticism is of how they did it. And the mind-set which they brought to this place. I fear that their mind-set here is inimical to internationalism.

iF: The binary between north and south Europe is a profitable one for a “classical” institution such as Documenta to exploit. Athens is just the place to experiment, after its seven very public years of financial chaos. Now there is the fetish of the crisis. This might even unintentionally reinforce the narratives of austerity. Referencing the Greek financial crisis so intensely appeals to all the precariats of the art world and to the middle- and upper-class museum directors and art lovers who are all very curious to see what a country that does not play ball with the EU can become. It is a voyeuristic desire to consume the crisis and the suffering of others, which is nothing new.

Of course, within the strict confines of the five still relatively prosperous neighborhoods where most of the venues and artworks are situated, this has not really been achieved. In fact, most visitors have asked me the same thing I have been hearing for the past seven years: Where is this supposed crisis? The precariat of the ecology of the art world seems to be part of the problem, as Sven Lütticken argues in his new book Cultural Revolution: Aesthetic Practice after Autonomy: the structural revolution of capitalism occurred through an economic but also cultural transformation. So to declare the Greek referendum and the events that followed it as the raison d’être for the exhibition in Athens,(4) when Documenta collaborated closely with those who supported the “Yes” campaign (including our current mayor, Giorgos Kaminis), is problematic.

YV: The point is not that they came but rather how they came to Athens, whom they went to bed with (metaphorically), and how they used a seemingly progressive left-wing critique of what is happening in Greece to willingly or unwillingly propagate the very process that is causing the country’s crisis. In the name of seeking solutions they became part of the problem.

iF: According to Documenta’s artistic director, Adam Szymczyk, Athens operates as a paradigm or a metaphor. Athens stands for the Global South, which I find intriguing but also problematic. I fear that the Global South—as it is recognized by cultural practices, political discourse, and social theory—can become a grouping of the Other, thus generating a continuation of “othering.” The curatorial statements use an anti-neoliberal rhetoric, which is very pro-internationalism, to underline unity and the expression of multiple voices. They question notions of origin and nationality; they talk about the global white patriarchal forces that wish to crush minorities, indigeneity, etc. So this institution presents an exhibition that claims to unite the precariats, the disenfranchised, the dispossessed, and the indigenous of the world: “We (all) are the people” read the words on the poster Hans Haacke produced for Documenta 14—against all these nationalistic neoliberal powers. So Athens is the metaphor for all that, and is in this case compared to Lagos or Guatemala City.

YV: This is why I like Schäuble! He put it very succinctly when in some press conference he suggested that Greece is to Europe what Puerto Rico is to the United States. When Jack Lew, the American treasury secretary under Obama, criticized Germany for its insistence on austerity in Greece, Schäuble suggested that the US (or “the dollar zone,” as he put it) and the EU trade Puerto Rico for Greece! Your depiction of this mind-set, according to which Greece represents the Global South, is accurate and is shared by Germany’s federal finance minister.

iF: The problematic aspect is that this discourse—“all the others are the same”—smells like First World didactics. This approach of “let’s unite or group the precariats” under an anti-neoliberal, or liberal, narrative—doesn’t matter which—becomes a priori dangerous. And this is a real problem, because we should be united in recognizing difference. Of course, on the other side of this you have the nationalists and the neofascists, and I wonder where to stand between these two positions—one position that hastily groups all the precariats, indigenous, and minorities together, and the other that claims “we are undeniably unique and incomparable.” However, I wonder if I’d like it if I were a citizen of Lagos or Guatemala City and someone compared my condition to that of an Athenian.

YV: On the one hand, Athens actually looks like Paris if you compare it to Lagos, though it is degenerating quickly. On the other, the trajectory of countries like Nigeria isn’t necessarily pushing them toward desertification. The great difference is the static versus the dynamic. Countries like Nigeria have a dynamic which may lead them either to disaster or to development, whereas the Greek dynamic is one that I call “Kosovization,” of turning Greece into a protectorate, just like Kosovo, where young people all leave and the place is a real estate opportunity, with pensioners starving and northern European pensioners enjoying cheap old folks’ homes by the seaside. So maybe Nigeria and Lagos have advantages compared to Greece and Athens. At the dynamic level, not at the static.

I also find it remarkable that Documenta’s narrative in Athens is anti-neoliberal. Speaking from my 2015 experience, I had the terrible task of negotiating with creditors whose objective was not to recoup their money. What I was proposing to them was consistent with neoliberal policies, because the crisis was at such an advanced, deep stage that it took a finance minister from the radical left to propose Reaganite and Thatcherite policies: cut your losses, reduce tax rates when both employers and employees are bankrupt, etc. Indeed, when you have low tax revenues and companies and households that are bankrupt, banks that are bankrupt, and actually a state that is bankrupt, and you have very high tax rates, it is not a left-wing economic policy to increase tax rates. It is just madness, from both a left-wing and a neoliberal perspective. So I was proposing to supposedly neoliberal creditors—the International Monetary Fund, Mario Draghi’s European Central Bank—substantial reductions in tax rates, which is what neoliberals supposedly advocate. Remarkably, they would not only turn these policies down, but try to portray me as recalcitrant. Why? Because they were not even interested in neoliberal policies, they were solely concerned with a nineteenth-century-style power play—a postmodern version of gunboat diplomacy. In this context, the critique of neoliberalism that Documenta is trying out in Athens is totally out of place. In 2017 Greece, neoliberalism’s failure is evident in the rejection by neoliberal institutions of neoliberal policies! A delicious paradox that Documenta is utterly blind to, because if they were to talk about the real tragedy unfolding in Greece today, an off-the-shelf critique of neoliberalism would not suffice. They would have to dig deeper, and thus run the risk of discovering the role of the German-led policies combining authoritarianism, large loans to bankrupt banks and governments, and savage burdens for the weakest of citizens in places like Greece but also Germany. Such a “discovery” would risk upsetting Documenta’s sponsors, who remain untouched by the (irrelevant) off-the-shelf critique of neoliberalism.

In short, coming to Athens to talk about “neoliberal powers that wish to destroy Europe” is to miss the point spectacularly. It is like the Greek Communist Party which, stuck in the 1960s and ’70s, blames all of Greece’s ills on American imperialism, while having nothing to say about the Troika, Berlin, Paris, Brussels, or Frankfurt. Like the Greek Communist Party, Documenta ignores the fact that Greece is the most brittle part of a European monetary union set up by the Franco-German axis. A union so terribly designed that it led to a massive, inevitable crisis and, moreover, to the denial of that crisis once it erupted—a denial that took the form of toxic new bailout loans for the bankers and austerity for the majority of the people. When Documenta comes here and talks about neoliberalism with no mention of Deutsche Bank, Société Générale, the awful Troika process, the Eurogroup, etc., it is choosing to be irrelevant. It is choosing to fight the last war against Europe’s Deep Establishment in order to avoid exposing the latter’s current war against decency and rationality. If I were the Troika, I would be very happy with the Athens Documenta. It would add legitimacy to my endeavors by sending art tourists to a disaster area of the Troika’s making. I would not be in the slightest upset by its critique of neoliberalism as long as there is no critique of … the Troika! As I intimated above, neoliberalism is not even being practiced by the Troika. What the Troika is practicing in Greece is punitive illiberalism.

iF: But this is presented as financial “aid,” as doing Greeks a favor by first tolerating us and then saving us. This is also the case with Documenta. I recently had a visit from a group of master’s art students from The Hague to the gallery where I work, and they were troubled by Rasheed Araeen’s work in Kotzia Square, Shamiyaana—Food for Thought: Thought for Change, 2016–17, which is basically a communal cooking and eating ritual that happens twice a day. While the artwork was taking place, an invigilator was trying to explain to a hungry Greek pensioner that he had to stand up and give his seat to the students, because this was not a food bank but an artwork. I am sure the artist had the best of intentions, but sadly it fed into this narrative of solidarity, and “helping the crisis situation” in a locality that cannot understand this artistic discourse, or the simulation of a communal kitchen and free food being distributed under the auspices of an artwork. This is a recurring problem of socially and politically engaged participatory art practices. This narrative of aid, of solidarity can become quite dangerous, when in fact there shouldn’t be aid but a mutually understood exchange. Of course there was a lot of money spent on this exhibition, but in Athens the expenses were mostly for its production, for the salaries of the staff who moved here, their transport, stipends, etc. The institution did give jobs and know-how to locals they hired as employees—and we can debate whether they were paid handsomely or not, or whether they received German-level salaries, etc., and indeed there was an incident with invigilators that, through the intervention of the artistic director, was solved. While I know of people who were not paid well, I also know of some people who received good salaries. And the decision to come here generated revenue, the staff did rent apartments, did spend money in this country: no doubt about that. I am assuming they spent more than anticipated, to be fair.

Nonetheless, to go back to the beginning, in 2015 at the Moscow Biennale you commented that Documenta 14’s arrival in Athens was “crisis tourism.” I must admit that I thought this was hasty. I wondered why you made that statement so early on, without “proof of presence” yet. I wonder whether we can call it crisis tourism, or even cultural imperialism, because I really do not think that we can call it cultural colonialism.

YV: I called it disaster tourism I think, but crisis tourism is the same thing. The distinction between the two is vague. When you have, in a peripheral country, the kind of disaster that we have, this is part and parcel of the neocolonial policy, which brought about the crisis.

iF: So, in fact you do consider it a neocolonial practice.

YV: Absolutely. There is no doubt about it. It is nineteenth-century power politics, or gunboat diplomacy, utilizing the financial sector. The people of Greece elected a government to challenge the terms of a loan agreement whose policy framework had already failed and the creditors arrived by private jet before unceremoniously telling the new finance minister that “if you insist on renegotiating our loan agreement we are going to close down your banks within weeks.” Think about it: in the nineteenth century, if a government had insisted on resisting their will, they would have sent gunboats or troops to Piraeus and started bombarding. Is today’s version significantly different? Our situation is not even neocolonialism. It is pure colonialism.

iF: However, in the case of British colonialism, it was done with much more violent means.

YV: I’m not sure if the means were more violent, just more inefficient. Violence is unnecessary, inefficient today. As Bertolt Brecht once said, “Why send out murderers when we can employ bailiffs?” Similarly we can ask: Why use Panzer tanks when you can use a button to close down all the ATM’s of a stricken nation? This is the undercurrent: the subjugation of a people and a government to the imperatives of creditors who wanted effectively to use the state’s unsustainable debt as a means by which to get their hands on particular assets. Like the airports, the ports, everything with value. Which is currently happening. When cultural organizations from the core come to the periphery, where the disaster is taking place, under the circumstances we are discussing, this is disaster tourism. And neocolonialism. It is exactly the same story.

iF: I generally question the sovereignty of the Greek state throughout the last fifty years. The way you have publicly portrayed the events from March 2015 onwards suggests that this sovereignty barely exists now, with the referendum offering more proof. The theme of Documenta 14 is “Learning from Athens,” and there was a decision to include historically charged spaces, such as the Museum of Anti-dictatorial and Democratic Resistance, as well as the Polytechnic School of Athens, where the uprising of November 17, 1973 took place.(5) But when it comes to why Greece is in this financial and political state today —this was blatantly omitted from Documenta. I think that the elephant in the room when we talk about the Greek financial crisis is the why and the who, and these were missing from the exhibition.

YV: You are spot on. There has been no attempt to understand the political and economic history of Greece. But I find it unproductive to try to push this line forward. My conclusion is that the best way to deal with it is this: any attempt to nuance the narrative on Greece feeds the trolls—those who want to say “ha, the Greeks want constantly to excuse themselves for their failures, they want to shun their own responsibilities and refuse to modernize; they demand their right to be premodern and to be fed by European money.” That is what you get the moment you bring forward the argument of how we fell into the net of the crisis: you lose the argument. The only thing you can say is, “Folks, imagine if we had not entered the Euro in 2000. Would Documenta be taking place in Greece today? No. Why? Because there would be no crisis.” The moment you say this they cannot continue to play the game of blaming the victim.

iF: It is the classic narrative that emerges, both in the cultural field and the political field, when one raises the kinds of issues we have discussed: the marginalization of opinion, the dismissive attitude towards the “complaints” or “rantings” of the Greeks. Funnily enough, it was Preciado who called this phenomenon the “pathologization of all forms of dissidence.”(5)

YV: Oh, the story of my life. I also felt that when discussing this crisis. How do you stop yourself from becoming the raving loony, the sole voice of dissent? We are in a situation that resembles the late Soviet era. In 1983, the USSR still had the capacity to enforce a unitary narrative through its media, a narrative of a “single party line everywhere.” But, at the same time, there was a major disconnect between that unitary dominant party line and what people actually thought. It is similar in Greece today: the state is happy with Documenta, they think it will bring tourism in, but when I talk to people on the streets about it, they reject it with venom. The only way of avoiding becoming the lone enraged dissident is to connect with public opinion.

iF: Public opinion has been vividly demonstrated by the myriad graffiti. Yet, I am not sure that the majority of the public rejects it with venom, the reason being another form of disconnect: the general public does not even know it’s here. The realization of the exhibition was such that unfortunately it will fail in what most of the small local art institutions were hoping for: to breed a new, larger audience for contemporary art. Documenta’s undelivered message will be ours to realize, in politics and in art.

(1) Paul B. Preciado, “The Apatride Exhibition,” e-flux conversations, April 10, 2017, https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/pa....

(2) DiEM25 describes itself as a “pan-European, cross-border movement of democrats” dedicated to the “repair” of the EU. See https://diem25.org/what-is-diem25/.

(3) Documenta has never published detailed financial accounts of expenses and incomes, just a general figure for total expenditures. But it surely receives more than just state funding. In fact, an official announcement from the office of Documenta states that “the business plan for documenta 14 covers a five-year period. During this timeframe, documenta and Museum Fridericianum gGmbH receive 14 million euros from the City of Kassel and the State of Hessen, both of which are shareholders, and 4.5 million euros from the German Federal Cultural Foundation (Kulturstiftung des Bundes). The remaining 18.5 million euros needed to finance documenta 14 must be raised by documenta and Museum Fridericianum gGmbH in the form of proceeds from the sale of admission tickets, catalogues, and merchandise and through sponsors, additional funding, and grants.” As Artforum reported on March 22, 2017, Ms. Kulenkampff has requested more state funding. See https://www.artforum.com/news/id=67355. It is unclear whether this funding will be put toward the current edition of Documenta.

(4) Preciado, “The Apatride Exhibition.”

(5) Ibid.

iLiana Fokianaki is a Greek curator, lecturer, and writer based in Athens and Rotterdam. She is the founder and director of State of Concept, Athens, co-founder, with Antonia Alampi, of the research platform Future Climates, and curator of Kunsthal Extra City, Antwerp.

Yanis Varoufakis is a Greek economist, academic, and politician who served as the Greek Minister of Finance from January to July 2015, when he resigned. Varoufakis was also a Syriza member of the Hellenic Parliament for Athens B from January to September 2015. In 2015 he co-founded, with Srećko Horvat, the pan-european political movement DiEM25.

1Logo of Documenta 14.

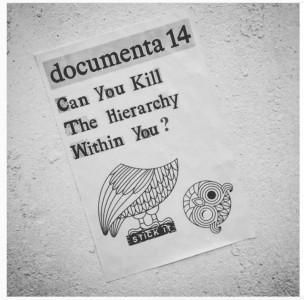

2Poster in Athens, Spring 2017.

3Graffiti in Athens close to the site of the presentation of Ross Birrell’s The Athens–Kassel Ride: The Transit of Hermes, 2017.

4Rasheed Araeen, Shamiyaana—Food for Thought: Thought for Change, 2016–17.

5Posters in Athens, Spring 2017.

6The Lgbtqi+ Refugees in Greece group with the replica of the oath stone of Roger Bernat’s The Place of the Thing,2017.

7Graffiti in Athens, Spring 2017.

8The Lgbtqi+ Refugees in Greece group with the replica of the oath stone of Roger Bernat’s The Place of the Thing, 2017.

9Graffiti in Athens, Spring 2017.

10Graffiti in Athens, Spring 2017.

11Graffiti in Athens, Spring 2017.

1Logo of Documenta 14. Design by Studio Laurenz Brunner, Berlin.

2Poster in Athens, Spring 2017.

3Graffiti in Athens close to the site of the presentation of Ross Birrell’s The Athens–Kassel Ride: The Transit of Hermes, 2017.

4Rasheed Araeen, Shamiyaana—Food for Thought: Thought for Change, 2016–17. Canopies with geometric patchwork, cooking, and eating, Kotzia Square, Athens, Documenta 14. Photo: Yiannis Hadjiaslanis.

5Posters in Athens, Spring 2017.

6The Lgbtqi+ Refugees in Greece group with the replica of the oath stone of Roger Bernat’s The Place of the Thing,2017. Photo courtesy Lgbtqi+ Refugees in Greece.

7Graffiti in Athens, Spring 2017.

8The Lgbtqi+ Refugees in Greece group with the replica of the oath stone of Roger Bernat’s The Place of the Thing, 2017. Photo courtesy Lgbtqi+ Refugees in Greece.

9Graffiti in Athens, Spring 2017.

10Graffiti in Athens, Spring 2017.

11Graffiti in Athens, Spring 2017.

Mel Bochner’s “Voices”

PETER FREEMAN INC., New York

Dara Birnbaum’s “Psalm 29(30)”

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY, New York

“Quiet”

BARBARA SEILER GALERIE, Zürich

June 9, 2017

Jeremy Corbyn’s night was one for the true believers. Onwards now!

In September 2015, soon after Jeremy Corbyn’s election, I was asked to offer advice to the freshly elected Labour leader. My response was, following our experiences in Greece of defeating a resurgent, oligarchic media twice during that year:

Do not get scared by the character assassination attempts of the systemic media. The systemic media will try to tear you apart. What is important is that you shower them with rational arguments, with compassion, with a degree of humour and self deprecation, and concentrate on cultivating very strong relations with the public out there who have had a gutful of spin and of the attempts of all parties to congregate in the middle ground where they hope to serve the prejudices of the median voter.

Faced down by an ironclad establishment hell bent on retrieving its control over the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn stood his ground on behalf of basic human decency and, moreover, of Progressive Principled Politics.

Last night the British people rewarded him, and his comrades, for this with an astounding vote of confidence. Against the grain of a British press that had never been so unified before, in ridiculing and distorting his sensible policies and his civilised demeanour (even The Guardian was pitted against him, until the last few days of the campaign), he did that which progressives must always do: He stayed glued to his message and ignored the distortions, provocations, attempts at character assassination of the media, succeeding in the end to bypass them and speak directly to the hopes and concerns of the electorate.

In such a political and media environment, stopping Theresa May’s bandwagon, scoring amongst the largest Labour shares of the vote since WW2, and forcing a hung Parliament upon a Tory leader that was considered a dead-cert victor, was a magnificent victory.

Of course, like all victories that progressives score against the establishment, it is a small stepping stone along a difficult path. Like all progressive victories its significance is not in what it achieved but in the potential that it now unleashes on behalf of the people of Britain and of progressives everywhere.

Onwards comrades!

June 7, 2017

DiEM25 supports Jeremy Corbyn & John McDonnell – except in our own special way!

After DiEM25 published its collective decision to back fifteen Parliamentary candidates in tomorrow’s UK General Election, we received some interesting missives – mostly critical that included non-Labour candidates, including (lo and behold) Nick Clegg. This is a welcome ‘backlash’, in the sense that it gives us an opportunity to put things straight.

DiEM25 was not created just to support existing political parties. Our task is tougher and more important than this: it is to forge the Progressive International that Europe needs, and to promote its values and principles politics in every country. Of course, when a political party is close to our principles and agenda we will do our utmost to support it.

Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell are two politicians who have steered Labour in a direction very close to DiEM25’s principles and aspirations. Naturally, we back them wholeheartedly. However, the Labour Party still leaves much to be desired – as Jeremy and John would readily admit. A certain sectarian attitude (e.g. fielding candidates against progressives, and DiEM25ers, like Caroline Lucas), a strong tribal tendency, support for first-past-the-post, powerful forces within that are keen to return to a Blairite deep establishment posture – these are examples of why we believe that DiEM25 had to do more than simply support Labour.

In endorsing candidates from different political parties, with a solid rationale for each one of them (see here), DiEM25 is demonstrating in practice the kind of new, progressive politics that would end the neoliberals’ near monopoly of power in the UK and usher in a progressive government. Notice that in constituencies where we supported non-Labour candidates we selected candidates that have a strong chance of toppling a sitting Tory. Notice further that, if our endorsements had also been adopted by the Labour Party, the probability of a Jeremy Corbyn 10 Downing Street would have been enhanced. In short, DiEM25 is genuinely behind Jeremy and John – except in our own special way!

Lastly, on the ‘small’ matter of endorsing Nick Clegg I must say that this was not a choice that I voted for. Nick may have had a change of heart recently, and has called for a progressive alliance government in the UK – all good, proper and in concert with DiEM25’s agenda. BUT, he stands condemned for his connivance in the class war against the weak; i.e. the austerity policies of George Osborne and David Cameron. He also stands condemned for having acceded to various anti-social, uncivilised Tory policies, e.g. trebling university tuition fees. NEVERTHELESS, DiEM25 is a boisterous, democratic movement that combines horizontal decision making with all-member votes. That very process, which we cherish at DiEM25, yielded this particular recommendation – one that I must, and I do, accept.

June 6, 2017

The 15 parliamentary candidates DiEM25 endorses for Thursday’s UK General Election

DiEM25 was formed to build a Progressive International across Europe. The UK, especially since Brexit prevailed in last year’s referendum, is a major battleground for European democracy. The way Brexit is handled will be crucial for the future of Britain but also for European peoples far and wide. DiEM25 could not be absent from this election campaign.

DiEM25’s own position on what should happen once Brexit won the June 2016 referendum is already on record. Following an internal two-stage vote that took place November 2016, DiEM25 members from across Europe opted for the following position:

We support negotiations between the UK and the EU leading to an interim EEA-EFTA UK-EU arrangement (i.e. Norway/Swiss-like) to come into force two years after Article 50’s activation and, subsequently, to a long-term agreement viz. the UK-EU relationship to be approved by the next Parliament (to be elected after Article 50’s activation).

More recently, once Prime Minister Theresa May called an election in search of a mandate for what we consider an ill-fated Brexit negotiation with the EU, DiEM25 UK members decided to demonstrate in practice DiEM25’s progressive, inclusive, transnational politics by identifying candidates across the UK that come close to DiEM25’s progressive agenda for Britain and Europe. Our members have been active in selecting candidates that DiEM25 ought to support in different constituencies with a view not only to improve their chances of being elected but also to give an example of what DiEM25’s commitment to PRINCIPLED VOTING means.

Once DiEM25 UK members put together their recommended list of candidates, the complete list was put to an internal vote. Every DiEM25 member, from across Europe, had a vote in this. This is DiEM25’s weapon against the logic of Brexit, of the UK’s isolation from the rest of Europe: Every DiEM25 member, English, Welsh, Scottish, Irish, French, Greek etc., gets to vote on our favourite UK parliamentary candidates. It is our way of illustrating the formation of a European demos that rejects both a one-size fits-all attitude for Europe and isolationism.

The results are now in! Below you will find the list of candidates that DiEM25 endorses for the 8th June 2017 UK general election. It includes candidates from the Labour Party (6); the Liberal Democrats (2); the Scottish National Party (2); Plaid Cymru (1); the Greens (1); the Scottish Greens (1); the National Health Action Party (1) and the Women’s Equality Party (1).

The fact that DiEM25 endorses even Liberal Democrats (like former Prime Minister Nick Clegg, whose connivance with David Cameron’s and George Osborne’s class war against poorer Brits was inexcusable and remains unforgiven) reflects Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system. A proportional system would have, naturally, yielded a different set of recommendations. But, when progressive politicians, even if flawed in a variety of ways; e.g. Nick Clegg), are pitted against hard, xenophobic Brexiteers, it is within the realm of our PRINCIPLED VOTING philosophy to support them. Of course, we need to draw the line somewhere. For example, the failure of a substantial body of dissent against toxic, nationalist Brexiteering to rise within the Conservative party makes it impossible for DiEM25 members to endorse Tory candidates. Our members have, nevertheless, singled out three Tories for their resistance to the Brexit juggernaut: Anna Soubry for her dissent to hard Brexit; Kenneth Clarke who, despite his uncritical support for the EU establishment, has been a courageous adversary to the isolationism of Brexiteers; and Baroness Warsi for upholding basic values of decency in the House of Lords debates.

The fifteen DiEM25 parliamentary endorsees

Mhairi Black (SNP, Paisley and Renfrewshire South)

Kelly-Marie Blundell (Liberal Democrat, Lewes)

Nick Clegg (Liberal Democrat, Sheffield Hallam)

Patrick Harvie (co-convenor of the Scottish Green Party)

Kelvin Hopkins (Labour, Luton North)

Louise Irvine (National Health Action Party, South West Surrey)

Clive Lewis (Labour, Norwich South)

Rebecca Long Bailey (Labour, Salford and Eccles)

Caroline Lucas (Green, Brighton Pavilion and an Advisory Panel member of DiEM25)

John McDonnell (Labour, Hayes and Harlington and an Advisory Panel member of DiEM25)

Lisa Nandy (Labour, Wigan)

Sophie Walker (Womens’ Equality Party, Shipley)

Hywel Williams (Plaid Cymru, Arfon)

Toni Giugliano (SNP, Edinburgh West)

Matt Kerr (Labour & Co-operative, Glasgow South West)

Our fifteen candidates in brief

Mhairi Black became SNP MP for Paisley and Renfrewshire South in the 2015 general election while still a final year undergraduate student at the University of Glasgow. One of the youngest MP’s ever, she is, however, a longstanding critic of the Westminster government, for its unreality, arrogance and sexism. She considered not standing for a second term due to the fact that “so little gets done”. She is on the Work and Pensions Committee, has campaigned tirelessly for Women Against State Pension Inequality (WASPI), and has highlighted the increasing dependence of people on food banks, On the EU, she said on one occasion “If I’m honest there was an element of holding my nose when I voted Remain”.

Kelly-Marie Blundell is the Liberal Democrat candidate for Lewes and became active in the party in order to engage more people in politics. Unashamedly pro-EU, Kelly-Marie organised marches following the referendum. She is well known for speaking up on the NHS and Sheltered Housing as well as leading debates on welfare and social security. Kelly-Marie has worked in the charity sector for the last 8 years as a fundraising and marketing professional, having previously worked as a Citizen’s Advice Bureau advisor and as a Union representative. Kelly-Marie is passionate about rural and town life, making sure communities have access to the services they need and that local business can thrive. She says: “Nationally the country is in crisis. Both the Conservatives and Labour are focused entirely on in-fighting while the economy worsens, threatening jobs, public services and our efforts to build the houses Britain so badly needs”.

Nick Clegg was Deputy Prime Minister in Britain’s coalition government from 2010 to 2015, Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 2007 to 2015, and has been Liberal Democrat MP for Sheffield Hallam since 2005. Previously an MEP, he is currently LD Shadow Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union and LD Shadow Secretary of State for International Trade. In an indirect admission that he was profoundly wrong to go into a coalition government with the Tories, and for helping administer an economic and social policy that disadvantaged and disenfranchised poorer and rural Britons, he now says that Britain is run by an unaccountable cabal coordinating Brexit on behalf of the financial sector. In his view, the only solution to a “rotten” British democracy is non-Conservative and anti-Brexit forces coming together after the election to create a viable opposition against a one-party state, for cleaner politics and for progress. Brexit, he suggests, brazenly ignores the interest of the younger generation and they must keep pointing out that the decision was not taken in their name.

Patrick Harvie, co-convenor of the Scottish Green Party, Member of Scottish Parliament for the Glasgow Region and candidate in the UK 2017 General Election for Glasgow North. Patrick is the first openly bisexual Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom and has actively campaigned for civil partnership legislation and more recently for the TIE (Time for Inclusive Education) campaign which focuses on LGBT visibility within the Scottish education system. Patrick, post-Brexit argued that European citizens must focus on changing Europe to serve the interest of the people, as opposed to the corporate interests at present, and for an independent Scotland to re-join a reformed European Union.

Kelvin Hopkins, Labour MP for Luton North, was first elected to the Commons in 1997. His professional career was spent as an economist and policy researcher for trade unions, especially UNISON, and he is deeply sceptical of Labour’s conversion to free market economics. In one debate he described the private finance initiative as “irrational nonsense”, and described it as ‘less popular than the poll tax’. He emerged well from the 2009 MPs expenses scandal, being deemed a “saint” by The Daily Telegraph for his minimal second home claims. He was one of 16 signatories of an open letter to the then Labour leader Ed Miliband in January 2015, which called on the party to commit to oppose further austerity, take rail franchises back into public ownership and strengthen collective bargaining arrangements. Hopkins was one of 36 Labour MPs to nominate Jeremy Corbyn as a candidate in the Labour leadership election of 2015. Before the 2016 referendum on British membership of the EU, Hopkins signed the People’s Pledge, a cross-party campaign for such a referendum, and became a member of its Advisory Council. In 2016 he was one of the leading Labour figures to support the Leave campaign in the UK Referendum on EU membership.

Louise Irvine, is the National Health Action Party candidate standing against Jeremy Hunt in South West Surrey. She is ‘more than ready’ to challenge Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt as many Labour, Liberal Democrat and Green Party members have agreed to back her. Irvine, who led a successful campaign against government plans to downgrade hospital services in Lewisham, where she works, teaches many junior doctors who feel abused and misrepresented by their contracts of employment. She sees widening inequality and opposes the privatisation of the health service, calling for the integration of health and social care, as opposed to the current move towards unaccountable care systems. She says: “the market has wasted billions and we want to make it a public service again. The staff need to be properly valued and properly paid. We have to increase funding by at least £5 billion a year.”

Clive Lewis, Labour MP for Norwich South was appointed Shadow Secretary of State for Defence in June 2016 and Shadow Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy in October 2016. He is calling for a second referendum on the terms of the Brexit deal to heal a divided country, and voted against the Brexit bill in order to be “Norwich’s voice in Westminster, not Westminster’s voice in Norwich.” He has said: “The Tories’ plan for Brexit is a plan for a race to the bottom which we will all lose, with weakened human rights, rampant deregulation, and a diminished Britain. It’s an extreme agenda which will not only isolate our country but fatally undermine its democracy, weakening parliament and giving the government unprecedented power to pursue its agenda. We have to wake up before it’s too late, and vote to stop Tory Brexit.”

Rebecca Long Bailey is Labour MP for Salford and Eccles. Previously Shadow Chief Secretary to the Treasury, she is currently Shadow Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. Rebecca Long Bailey has been an outspoken politician criticising the abysmal record of austerity policies by the conservative government. She stands for one of the most deprived inner city areas, Salford and Eccles, an area of historic significance, made famous by L.S.Lowry. She is highly qualified to speak on economic, energy and financial matters and policy and has therefore would have great authority in future talks with European partners in Brexit negotiations.

Caroline Lucas, is the Green MP for Brighton Pavilion and argues that Britain could lead the way on climate change, She will continue to “put her constituents first by campaigning for Britain to remain as close to the European Union as possible and immediately guaranteeing rights of EU nationals here”, campaigning on housing, the NHS and for school funding. She will be an independent Green voice, not constrained by the party whip but “looking to work across party lines on the issues that matter”. She has said: “There’s absolutely no doubt that Brexit is central to this election. The Tories’ extreme agenda would see the UK leaving the single market, ending free movement and endangering our social and environmental protections. This damaging plan must be resisted and we urge people across to use their vote to reject an extreme Brexit.”

John McDonnell, Labour MP for Hayes and Harlington in 1997, became Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer in September 2015. Major architect of Labour’s alternative economic strategy and the current manifesto, committed to scrapping Theresa May’s Brexit plan; committed to introducing a bill to ensure workers’ rights are protected, to guaranteeing that EU nationals can remain in the UK, to negotiating tariff-free access to the European market and to allowing MPs to vote on the final deal. Recently, he challenged a media not doing their job, to help the general public have a democratic election debate, by holding the Tories to account on their “completely uncosted Manifesto of Misery.”

Lisa Nandy, elected Labour MP for Wigan in 2010. A strong advocate for a more humane and sensible refugee policy, she has repeatedly challenged the Home Office for outsourcing refugee housing contracts to private companies such as G4S and Serco, with disastrous effects on both the prospects of integration of refugees into the UK, and the resilience of local communities in these areas. Nandy has focused on the growing divide between British towns and cities, rejecting the rhetoric of “leftbehind communities” by stressing the importance of community bonds in these areas, and people’s right to a dignified life from wherever they come. She understands and has campaigned on one of the central issues that DiEM25 is trying to address: the toxic combination of involuntary underemployment and involuntary migration.

Sophie Walker is the leader of the Women’s Equality Party and is standing in Shipley. Walker, a Remain supporter, wants an “equality impact assessment” of any final Brexit deal, and the chance for MPs to vote it down if necessary. She is standing against a Tory MP who tried to derail a bill to protect women against violence, and told a conference hosted by an anti-feminism party that “feminist zealots really do want women to have their cake and eat it”. As other opposition parties consider giving her a free run in her attempt to unseat the Shipley Conservative MP, the journalist who became the WEP’s inaugural leader in 2015 has been at the forefront of its campaigns for equal representation and pay in working life. She says her opponent‘s anti-equality agenda in Westminster and anti-democratic practices such as filibustering legistlation threatens the rights and freedoms not just of women but also people with disabilities, BAME (black, Asian, and minority ethnic) and LGBT+ communities.

Hywel Williams MP, Plaid Cymru, was elected in 2015 to the Arfon seat. Appointed Head of the Centre for Social Work Practice at the University of Wales, in 1993, having worked as a mental health social worker in Dwyfor, Williams then became a freelance lecturer, consultant and writer in the fields of social policy, social work, and social care, working primarily through the medium of Welsh. He has been a member of numerous professional bodies in relation to social work and training, and was also spokesman for the Child Poverty Action Group in Wales. His parliamentary responsibilities within Plaid Cymru are work and pensions, defence, international development and culture. Campaigning to remain in the European Union, in PM Question Time, he claimed Theresa May was planning to cut a special deal for Britain’s financial sector: “A soft Brexit for her friends in the city, a hard Brexit for everyone else. Will she cut a similar deal for Wales?”

Toni Giugliano, SNP Candidate for Edinburgh West. Born in Italy, he was President of the Young European Movement in the United Kingdom. He has worked for a number EU organisations in Brussels, including the European University Association, where he represented the interests of 850 universities across Europe and successfully led a campaign that halted cuts to research funding. He now works for one of Scotland’s leading mental health charities. He worked for Yes Scotland campaign during the Scottish Independence referendum and he is now fighting to keep Scotland in the single market and protect Edinburgh’s jobs which rely on single market membership.

Matt Kerr, is the Labour and Co-op candidate for Glasgow South West. A critic of the current benefits system, he is seeking cross-party support for a universal basic income as a way of providing security when people change jobs much more frequently than in the past. He lobbied for changes to UK Border Authority and government policies that denied support to asylum seekers.

Background to the internal DiEM25 vote

The list was discussed and then ratified by our movement based on policies advocated by each candidate measured against DiEM25’s political values and beliefs. Our goal is a politics that is fair, democratic and non-polarising; not limited by party tribes, political sect or faction, or the hopelessly constrained binary opposition of the referendum. As a cross-party movement the DiEM25 UK list supports candidates from a variety of parties which share a progressive agenda. (Regrettably, although Conservative candidates were considered, the current regressive programme of the Conservative Party and the lack of vocal dissent did not allow us to include any.)

DiEM25 wants a harmonious and strong relationship established between the UK and EU notwithstanding the result of the 2016 referendum. ‘Brexit’ and the latter are not mutually exclusive: exiting the EU must not wilfully destroy the irreversible social, political and economic ties we have with the union. This is an unprecedentedly complex and risky period for the UK.

In their recent presidential elections, DiEM25 France compiled an endorsed list of candidates, employing DiEM25’s European New Deal as their guiding philosophy. While drawing inspiration from this text, DiEM25 seeks to address the UK’s specific democratic and transparency deficits and their prospects outside the Eurozone, a wealthy country with a poorly representative electoral system and an overly influential, weakly regulated and opaque financial sector. See the full document entitled ‘Principled Not Tactical’.

When the list went out for voting to all DiEM25 members, our UK Provisional National Committee received several complaints about the potential endorsement of candidate Nick Clegg. DiEM25’s goals are to set in motion a progressive and collaborative politics. In this context of isolation and polarisation, we are convinced that collaboration is the key term. To trigger change on the international level we should be inclusive of all political factions from across the country. Our decision to include Nick Clegg in our selection of candidates was based on our belief that to pave the way for the European New Deal also requires collaboration between progressive political traditions; social and liberal democratic, Leavers and Remainers alike. Nick Clegg’s singular experience of European politics among other things, qualify him to make a contribution to the broad coalition of democrats and progressives that DiEM25 seeks. As a movement, we are here to pick and choose the policies and beliefs that unite us rather than divide us.

We welcome everyone to join our movement whose objective is to put the demos back into our democracy – something that we can only achieve at home if Europe is democratised as a whole.

Carpe DiEM!

Do you want to be informed of DiEM25’s actions? Sign up here.

May 30, 2017

Jane Goodall’s review of Adults in the Room – Insider Story

If you studied economics at Sydney University in the 1990s, you might have had the good fortune to be taught in first year by a charismatic young lecturer who earned the nickname of the Greek God. Yanis Varoufakis, who in his youth bore some resemblance to John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever, liked teaching first year because it gave him the opportunity to divest students of the cut-and-dried assumptions they had acquired from the HSC course in economics.

Varoufakis had research interests in game theory, which he later tested in a venture with an innovative technology company named Valve. There, he and his partners experimented with management on the principle of “spontaneous order,” prioritising flexibility and self-determination in order to optimise freedom of initiative for employees. His sceptical view of game theory made him critical of any system based on manipulation and control.

Two decades on from his time at Sydney University, after a brief and turbulent period in 2015 as finance minister of the newly formed Syriza government in Greece, Varoufakis has resumed his career as an economics professor and public speaker. In a recent dialogue with Noam Chomsky at the New York Public Library, he characterised economics in the academy as a “mathematised religion,” an orthodoxy whose belief systems are insulated from the realities of market activity and financial transaction. As co-founder of DIEM 25, a reformist movement committed to a “surge of democracy” in Europe, he remains an indefatigable crusader for pragmatic human intelligence against systemic determination.

Television cameras and tabloid headlines can strip a public figure of all dignity and credibility, as Varoufakis learned from experience.

Adults in the Room is Varoufakis’s third major book on contemporary political economy. The first, The Global Minotaur (2011), concerns the changing role of America in the international economy following the global financial crisis of 2008. And the Weak Suffer What They Must? (2016) provides a historical context for the austerity in which Greece has become engulfed, tracing the macroeconomics of national debt back to the postwar era and the Bretton Woods agreement of 1944.

The three books constitute a kind of trilogy. The first leads up to an account of the first Greek bailout by the European Union. The second two revolve around the catastrophic debacle in which he became engulfed during his attempts as finance minister to negotiate with the European Union over the management of the Greek debt. It is as if he is compelled to revisit this traumatic epicentre – a zone of intellectual quicksand – and find the paths that led into it and may indicate a way out.

On one level, Adults in the Room, subtitled “My Battle with Europe’s Deep Establishment,” can be read as an autobiographical drama in which Varoufakis plays a contemporary Achilles, gladiator supreme and agile strategist, entering the fortress of the European Union as a champion of his people. Judging by the portrait photograph on the back of the book, Achilles is a role Varoufakis was born for. He’d be a potent physical and vocal presence on stage, as he is on the platform in so many international forums. Any theatre director seeking to cast a production of the Aeschylus trilogy Achilleis need look no further.

When he was chosen by the leader of the left wing Syriza party, Alexis Tsipras, to play a key role in a prospective Syriza government, the charisma was a bonus. It was Varoufakis’s credentials as an economic analyst that were paramount, supplemented by his sophisticated interest in game theory. By his own account, Varoufakis played a tough hand in negotiating his own involvement. At their first meeting in 2011, as he recalls it, he was concerned to “shake Tsipras out of his lazy thinking.” He advised him to get an English tutor and provided a firm lecture on the underlying principles they should adhere to.

It all sounds a little high-handed, reflecting as it does the assurance of someone who was already doing the rounds of international forums pronouncing on the state of the European Union in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Tsipras, though, proved to be a more agile thinker than Varoufakis initially gave him credit for. In the strategy tent, he and his key adviser Nikos Pappas agreed with Varoufakis on a five-point plan.

First, they must fend off any move by the European Central Bank to close the Greek banks. Second, the debts of the Greek state must be uncoupled from those of the banks, so that the government couldn’t be held accountable for bailout for money routed directly back to the banks in any bailout agreement. Third, they must “shout from the rooftops” that the new Syriza government was prepared to enforce strict fiscal discipline so that the country could begin to live within its means. But the fourth point was that humanitarian crisis must be avoided by imposing limits on austerity and introducing measures to assist those “below the absolute poverty line.”

Lastly, there was what might be termed the “Varoufakis special,” a “modest proposal” on which he had been working for some years in collaboration with American economist Jamie Galbraith and former British Labour MP Stuart Holland. This proposed a series of measures for rendering the eurozone viable in the continuing fallout from the global financial crisis. By putting this plan forward, the Syriza government would emphasise that their determination to release the Greeks from “debtor’s prison” was part of a more broadly conceived agenda to strengthen the European Union.

Varoufakis wanted no rash threats of Grexit, but he and Tsipras were agreed on the need to retain it as an option of last resort. As such, it was a key element in the bargaining strategy, the failsafe measure to ensure that the Greek people would not be subjected to another phase of “Bailoutistan,” the regime of debt management that had left three out of four households without employment and some 90 per cent of the unemployed without any form of financial assistance.

As the chosen emissary, Varoufakis was primed to compromise, adapt and collaborate on any reasonable terms. At the bottom line, though, he was the representative of a left-wing government voted into office by an electorate desperate to shake off the misery of ever-harsher austerity measures. In the early chapters of the book, he describes walking through the crowds of protesters who took up almost permanent residence in Syntagma Square outside the Greek parliament in the later, crisis-ridden years of the Papandreou government. Now, duly elected as a member of the government and invested with the critical responsibilities of the finance ministry, he is seen as champion of their cause.

At this stage, with Syriza taking office on the back of a rapid ascent in the polls, there is every reason for those crowds to have confidence in their finance minister. Varoufakis has the natural authority of someone who knows what he is talking about and whose principles have been forged in the sternest metal. As a speaker he’s charming, quick-witted, and fiercely cogent. As an economist, he’s rational and pragmatic.

But whatever his own capacities, they were sorely mismatched against those of the European establishment. Confidence was Varoufakis’s Achilles heel. It inspired a quixotic attempt to pitch clarity against obfuscation, reasonable argument against arbitrary determination, logic against absurdism. This was not, to use one of his own favourite phrases, going to end well.

His account of what transpires as he penetrates to the inner circles of power play in Brussels is based largely on recordings he made of the meetings. Chunks of verbatim dialogue fill out the pages of the book, and as he proceeds from one exchange to another, relentlessly insisting on the contrariness and illogicality he is encountering, it is as if the dramaturgy of Aeschylus is giving way to the absurdist scenarios of Alice Through the Looking Glass.

Anyone with a sceptical view of game theory would surely find a kindred spirit in Lewis Carroll. Carroll’s Alice stories feature playing cards, chessboards, a game of croquet and the famous language game with the domineering Humpty Dumpty, who declares he can make words mean what he chooses them to mean. “The question is,” he says, “which is to be master – that’s all.” Varoufakis finds himself dealing with people who have mastered the principles of economy in similar terms.