Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 122

July 23, 2017

Βοηθήστε να διαχωρίζεται η Αλήθεια από το Υποκινούμενο Ψεύδος – Ομιλία αποδοχής επίτιμου διδακτορικού από το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσσεξ

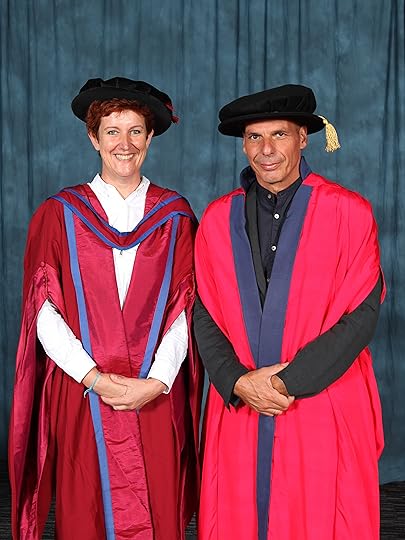

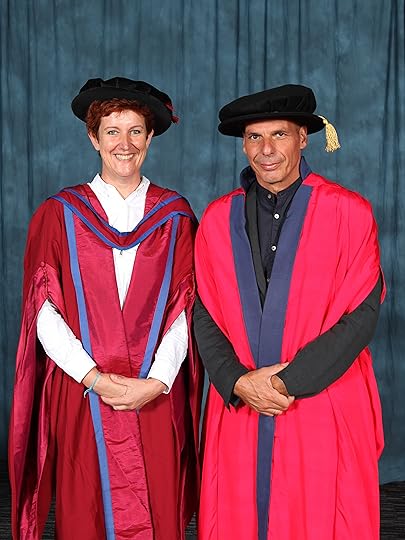

Την 20η Ιουλίου 2017, το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσεξ είχε την καλοσύνη να με ανακηρύξει Επίτιμο Διδάκτορα. Η Καθηγήτρια Άνρεα Κόρνγολ, Πρόεδρος της Σχολής Διεθνών Σπουδών του πανεπιστημίου, παρουσιάζοντάς με την Συνέλευση και στον Πρύτανη εξήγησε τους λόγους που αποφασίστηκε η απονομή του εν λόγω τιμητικού διδακτορικού ως εξής: “Για την προσφορά του στην κατανόηση της παγκόσμιας οικονομίας, τον γνήσιο διεθνισμό του, την ριζοσπαστική σκέψη του, και την παρρησία με την οποία υπερασπίζεται τις πολιτικές και του οικονομικές αντιλήψεις.” (Για ολόκληρη τη ομιλία της στα αγγλικά, πατήστε εδώ.]

Την 20η Ιουλίου 2017, το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσεξ είχε την καλοσύνη να με ανακηρύξει Επίτιμο Διδάκτορα. Η Καθηγήτρια Άνρεα Κόρνγολ, Πρόεδρος της Σχολής Διεθνών Σπουδών του πανεπιστημίου, παρουσιάζοντάς με την Συνέλευση και στον Πρύτανη εξήγησε τους λόγους που αποφασίστηκε η απονομή του εν λόγω τιμητικού διδακτορικού ως εξής: “Για την προσφορά του στην κατανόηση της παγκόσμιας οικονομίας, τον γνήσιο διεθνισμό του, την ριζοσπαστική σκέψη του, και την παρρησία με την οποία υπερασπίζεται τις πολιτικές και του οικονομικές αντιλήψεις.” (Για ολόκληρη τη ομιλία της στα αγγλικά, πατήστε εδώ.]

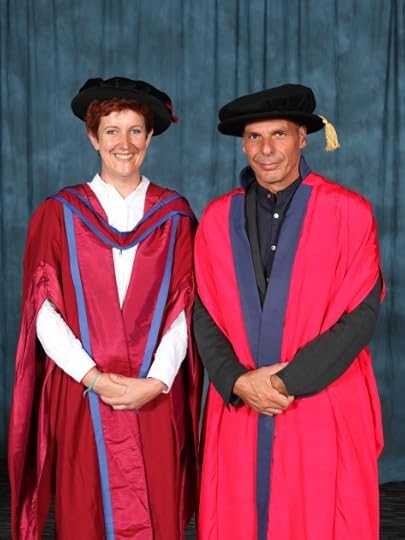

Με την Καθηγήτρια Άνδρεα Κόρνγολ, Πρόεδρο της Σχολής Διεθνών Σπουδών

Στην δική μου ομιλία αποδοχής του διδακτορικού τίτλου, είπα τα εξής (βλ. εδώ για το αγγλικό πρωτότυπο):

Το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσσεξ έχει τις ρίζες του σε μια, δυστυχώς, παρελθούσα εποχή. Σε μια εποχή όπου μια πιο φιλόδοξη από την σημερινή κοινωνία πίστευε, ορθώς, ότι κανένα λογιστικό σύστημα ή μέθοδος υπολογισμού κόστους-οφέλους δεν μπορεί να μετρήσει την αξία της μόρφωσης των πολλών. Μια κοινωνία που δεν θα διανοείτο ποτέ να χρεώνει, και υπερχρεώνει, τους νέους της πριν τους δώσει την ευκαιρία της μόρφωσης.

Τότε, στην δεκαετία του ’60, ιδρύθηκαν σε αυτή την χώρα πολλά νέα, σημαντικά, πανεπιστήμια με σκοπό όχι μόνον το άνοιγμα των θυρών της ανώτατης εκπαίδευσης στους έως τότε αποκλεισμένους νέους της εργατικής και μικρομεσαίας τάξης αλλά και στον επαναπροσδιορισμό του ρόλου της παιδείας.

Το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσσεξ ήταν από τα κορυφαία εκείνα νέα πανεπιστήμια και, από τότε, υπηρετεί την αρχική φιλοδοξία που το γέννησε με συνέπεια, ήθος και ανυπολόγιστη επιστημονική συνεισφορά.

Η φιλοσοφία που γέννησε το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσσεξ ήταν, και είναι, πραγματικά ενάρετη και ριζοσπαστική. Όμως, όπως λέγανε οι αρχαίοι μας, παν μέτρον άριστον. Ως νεαρός λέκτορας, θυμάμαι να με έχει συνεπάρει τόσο πολύ η φιλοσοφία που θεμελιώνει πανεπιστήμια όπως το Σάσσεξ που, σε μια ομιλία μου, μίλησα με υπερβολικό ενθουσιασμό για την δυνατότητα της μόρφωσης να εκπολιτίζει τις κοινωνίες. Όταν ολοκλήρωσα την ομιλία μου, με πλησίασε μια εκλεπτυσμένη, εύθραυστη, εντυπωσιακή ηλικιωμένη κυρία. Πριν ανοίξει το στόμα της, σήκωσε το ένα μανίκι της για να αποκαλυφθεί το τατουάζ στο χέρι της που αποδείκνυε ότι ήταν επιζήσασα του Άουσβιτς. Τότε μόνο μου είπε: «Οι δολοφόνοι μας ήταν μηχανικοί του Πολυτεχνείου που άκουγαν Μπετόβεν και διάβαζαν Γκέτε το βράδυ, στο σπίτι τους, αφού είχαν περάσει την μέρα τους στο κρεματόριο να μας αφανίζουν. Αγόρι μου, φοβάμαι ότι υπερ-εκτιμάς την αξία της παιδείας.» Κατόπιν απομακρύνθηκε αργά, αφήνοντάς με αποσβολωμένο, βουτηγμένο στην ντροπή που δημιούργησαν οι φράσεις της.

Η εκλεκτή εκείνη κυρία είχε απόλυτο δίκιο: Η μόρφωση δεν είναι ούτε αναγκαία ούτε ικανή συνθήκη για να γίνει ένας άνθρωπος καλός κ’αγαθός. Όμως, η μαζική παροχή μόρφωσης είναι αναγκαία συνθήκη για να εκπολιτιστεί μια κοινωνία. Και μπορεί να γίνει και ικανή συνθήκη εφόσον οι νέοι μάθουν, πάνω απ’ όλα, να προσεγγίζουν τη γνώση με κριτική διάθεση – να μην αποδέχονται μια διάλεξη, ένα εγχειρίδιο, μια θεωρία ως έχει και άνευ συστηματικής μελέτης και εμπεριστατωμένου σκεπτικισμού. Το κλειδί που ξεκλειδώνει τον πολιτισμό είναι η μόρφωση σε συνδυασμό πάντα με το επίγραμμα της Βασιλικής Εταιρείας του Λονδίνου: Nullius in verba! – με άλλα λόγια, δεν αποδέχομαι ποτέ κάτι επειδή κάποιος, ο οποιοσδήποτε, το πιστεύει.

Ίσως η πιο δυσάρεστη εμπειρία μου στην πολιτική ήταν οι στιγμές που λογικές, καλά επεξεργασμένες, προτάσεις προς ισχυρούς θεσμούς των οποίων οι αποφάσεις κρίνουν το μέλλον του κόσμου αγνοούνταν επειδή η συζήτησή τους απειλούσε τα συμφέροντα εκείνων που ήλεγχαν την ημερήσια διάταξη. Το ίδιο συμβαίνει και στις επιχειρήσεις. Όμως, καμία δημοκρατία, καμία επιχείρηση δεν μπορεί να ανθίσει μακροπρόθεσμα όταν νέες ιδέες απορρίπτονται ανεξάρτητα της αξίας τους λόγω της συντριπτικής δύναμης εκείνων που ωφελούνται από την καθεστηκυία κατάσταση ή τάξη.

Σήμερα, ίσως νομίσετε πως είστε στο κατώφλι που θα σας οδηγήσει από το πανεπιστήμιο στον «πραγματικό» κόσμο, στην «πραγματική» κοινωνία. Σας συνιστώ να μην αφεθείτε σε αυτή την φαντασίωση. Το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσσεξ δεν είναι, ως κοινωνικός χώρος, λιγότερο «πραγματικός» από τον χώρο των αγορών, των επιχειρήσεων ή του δημοσίου. Καθήκον σας είναι να μπολιάσετε τον «πραγματικό» κόσμο «εκεί έξω», εκεί που θα βρεθείτε από αύριο το πρωί, με την χωρίς φόβο ή πάθος κριτική στάση που διδαχθήκατε σε τούτο δω το πανεπιστήμιο. Καθήκον σας είναι να κάνετε τον κόσμο μας «πραγματικότερο», καλύτερο, πιο αποτελεσματικό και λιγότερο αυταρχικό μεταλαμπαδεύοντας σε αυτόν την ακαδημαϊκή μέθοδο διαχωρισμού της αδέκαστης αλήθειας από το σφάλμα που ωφελεί κάποιους ισχυρούς συμφεροντολόγους.

Για πολύ καιρό επιτρέψαμε τις πρακτικές της ποσοτικοποίησης ποιοτικών μεταβλητών, οι οποίες οδηγούν στην υποχώρηση της ποιότητας, να μεταναστεύουν από τις χρηματαγορές και τις πρακτικές της κρατικής γραφειοκρατίας στα πανεπιστήμιά μας. Η κουλτούρα της μανιώδους μέτρησης έχει καταφέρει πλήγμα στα πανεπιστήμιά μας και, κατ’ επέκταση, στις κοινωνίες μας – από το Εθνικό Σύστημα Υγείας έως και τον τρόπο που αποτιμούνται τα δομημένα ομόλογα ή σχεδιάζονται οι μακροοικονομικές πολιτικές. Από εσάς εξαρτάται να αναστρέψετε αυτή την πορεία.

Βέβαια, θα έρθετε αντιμέτωποι με βίαιες αντιδράσεις. Σημειώστε όμως τα σοφά λόγια του Όσκαρ Γουάιλντ: «… το να διαφωνεί κανείς με τα δύο-τρίτα των Βρετανών αποτελεί το βασικό προαπαιτούμενο της σωφροσύνης!»

Το μυστικό είναι να μην φοβάστε να είστε στην μειοψηφία. Να είστε, ταυτόχρονα, εποικοδομητικοί στις προτάσεις σας και ανυπότακτοι μπροστά στο φάσμα του αυταρχισμού και της ανοησίας – κριτικά ιστάμενοι απέναντι σε όλα αλλά και έτοιμοι να συνεργαστείτε με τους πάντες, με γνώμονα το κοινό καλό.

****

Στο πλαίσιο της βράβευσης, παραχώρησα την εξής συνέντευξη στο έντυπο του Πανεπιστημίου:

–Για πολλούς υπήρξατε ένας ήρωας, αν και καταδικασμένος, την περίοδο της υπουργίας σας το 2015. Είπατε ότι ήταν στιγμές που άλλαξαν την ιστορία. Τι ήταν αυτό που έκανε εκείνες τις στιγμές ιστορικές, για την Ευρώπη και για εσάς;

-Οι μόνοι ήρωες εκείνης της περιόδου ήταν οι Έλληνες που απέρριψαν με την ψήφο τους ένα ακόμα αρπακτικό δάνειο από την ΕΕ. Εγώ ήμουν απλά ο αγγελιαφόρος του μηνύματός τους.

Παρά τις απειλές ότι οι τράπεζες δε θα ξανανοίξουν και την εκστρατεία φόβου που εξαπέλυσαν τα μίντια , το 62% των ψηφοφόρων γύρισαν την πλάτη στα δάνεια και τις απειλές που τα συνόδευαν.

Ήταν μια ιστορική στιγμή επειδή για πρώτη φορά ένα χρεοκοπημένο έθνος βρήκε το κουράγιο να απορρίψει δάνεια που θα του επέτρεπαν να προσποιείται ότι όλα βαίνουν καλώς με αντάλλαγμα το κλείδωμα της πλειοψηφίας σε μια μόνιμη φυλακή χρέους. Ήταν μια ιστορική στιγμή και για έναν επιπλέον λόγο: έκανε δημόσια γνωστές τις αυταρχικές πεποιθήσεις ηγετικών στελεχών της Ευρώπης όπως του κ.Σόιμπλε που παραδέχτηκε ότι «οι εκλογές δεν επιτρέπεται να αλλάζουν την οικονομική πολιτική».

Τέλος, ήταν διπλά ιστορική στιγμή, γιατί η συντριβή της ελληνικής άνοιξης του 2015, επηρέασε την ψήφο υπέρ του Brexit, κάτι που με τη σειρά του έδωσε αέρα στα πανιά του Ντόναλντ Τραμπ στις ΗΠΑ.

-Τι μπορούν και τι πρέπει να φέρουν οι ακαδημαϊκοί στο χώρο της πολιτικής – μπορεί ένας ακαδημαϊκός να γίνει καλός πολιτικός;

-Οι ακαδημαϊκοί μπορούν να προσθέσουν συστατικά που λείπουν από την πολιτική: την προτεραιότητα στην ανόθευτη αλήθεια και τη φροντίδα ώστε οι προτάσεις και ιδέες που κατατίθενται στο δημόσιο διάλογο να περνούν από τη βάσανο της κριτικής. Οι επαγγελματίες πολιτικοί δυστυχώς εκπαιδεύονται να έχουν τις ακριβώς αντίθετες προτεραιότητες: είτε να υπερασπίζονται απόψεις που δεν πιστεύουν, είτε να απορρίπτουν καλές ιδέες μόνο και μόνο για να αποδομήσουν τον αντίπαλο που τις εκφράζει. Η πολιτική θα γινόταν πολύ πιο ωφέλιμη αν υιοθετούσε την ακαδημαϊκή λογική που κρίνει την ιδέα καθαυτή ανεξαρτήτως του ποιος την εκφράζει.. Αν μπορεί να γίνει ένας ακαδημαϊκός καλός πολιτικός; Αν καλός πολιτικός είναι ο μαιτρ της διαστρέβλωσης, ελπίζω πως όχι…

-Τα βασικά σας πτυχία ήταν στα μαθηματικά και τα οικονομικά. Τι σας οδήγησε σε αυτή την κατεύθυνση;

-Τα μαθηματικά είναι συναρπαστικά από αισθητικής άποψης. Ακόμα, για ένα πολιτικό ον, όπως εγώ, είναι καταπληκτικό το ότι μια θέση μπορεί να είναι σωστή ή λάθος μέσω της αποδεικτικής διαδικασίας και μόνο, ανεξαρτήτως της άποψης ή της οπτικής του καθενός. Όσο για τα οικονομικά, στις μέρες μας είναι τόσο απαραίτητα για κάποιον που ενδιαφέρεται να εκφράζει άποψη για την οργάνωση της κοινωνίας μας, όσο ήταν η Βίβλος το Μεσαίωνα.

-Τα οικονομικά για τη μεγάλη πλειοψηφία του κόσμου ήταν στεγνά και δυσνόητα. Τι έχει αλλάξει και σε τι βαθμό έχετε συνεισφέρει σε αυτή την αλλαγή;

-Ακόμα ο κόσμος πιστεύει ότι είναι στεγνά και δυσνόητα, και δικαίως, κατά τη γνώμη μου. Ο λόγος δεν είναι τα μαθηματικά που περιέχουν ή ότι είναι δύσκολο αντικείμενο καθαυτό. Ο λόγος είναι ότι για να λύσεις τα μαθηματικά που αφορούν τη ζωντανή καπιταλιστική οικονομία του σήμερα πρέπει να εισάγεις κρυφά αξιώματα τα οποία αφήνουν εκτός βασικές πλευρές του καπιταλισμού όπως η εργασία, το χρήμα, το χρέος. Λογικό είναι λοιπόν οι έξυπνοι φοιτητές να χάνουν το ενδιαφέρον τους να μάθουν θεωρητικά μοντέλα για τον καπιταλισμό που δεν έχουν σχέση με τη μελέτη του πραγματικού καπιταλισμού.

Στα έργα που έχω δημοσιεύσει σχετικά με την οικονομική θεωρία, τη θεωρία παιγνίων και την πολιτική οικονομία, προσπαθώ να διεγείρω τη φαντασία των φοιτητών, περιγραφοντας τη συναρπαστική πολιτική διάσταση που κρύβεται στα οικονομικά αξιώματα και καταδεικνύοντας τα αναλυτικά όρια των θεωριών αυτών.

-Ποιες πιστεύετε ότι είναι οι κυριότερες προκλήσεις για τους νέους που εισέρχονται στην αγορά εργασίας παγκοσμίως;

-Η κύρια πρόκληση είναι διαχρονική: Να βρει κανείς μια δουλειά που θα του άρεσε να την κάνει και δωρεάν και ταυτόχρονα να κερδίζει έναν αξιοπρεπή μισθό από αυτήν.

Η νέα πρόκληση, με βάση τις αλλαγές στην αγορά και την εργασία, είναι πως θα χρησιμοποιήσουμε έξυπνα την τεχνολογία, χωρίς να καταλήγουμε εμείς υπηρέτες της, και πως θα έχουμε την ελευθερία να διαλέγουμε τους συνεργάτες μας, στη δουλειά και στη ζωή γενικότερα.

-Πως βλέπετε το μέλλον της Ευρώπης και της Βρετανίας μετά το Brexit;

-Αρνούμαι να κάνω προβλέψεις, κυρίως επειδή καταλήγουν πολύ απαισιόδοξες. Αντίθετα, θεωρώ χρήσιμο να τονίσω τη σημασία που έχει να δουλέψουμε από κοινού, ώστε, ανεξάρτητα από το Brexit, η δημοκρατία, η αξιοπρέπεια, η οικονομική συνεργασία να γίνουν οι κινητήριες δυνάμεις για την Ευρώπη και τη Βρετανία και θα αντιμετωπίσουν τους δύο κινδύνους που μας απειλούν: τον τοξικό εθνικισμό και τον ζημιογόνο αυταρχισμό του κατεστημένου.

-Πρόσφατα γράψατε ότι η απάντηση στην παγκοσμιοποίηση και τον απομονωτισμό είναι ο αυθεντικός διεθνισμός – ένα διεθνές «New Deal» που θα συμπεριελάμβανε τη συγκέντρωση παγκόσμιων αποθεματικών. Πως μπορείτε να πείσετε τα έθνη για αυτή την πρόταση;

-Δεν είναι δύσκολο να πειστεί η πλειοψηφία στις περισσότερες χώρες του κόσμου για την ανάγκη ενός διεθνούς “New Deal”. H κοινή λογική είναι με το μέρος μας: Ζούμε σε ένα κόσμο που παράγει τα μεγαλύτερα αποθεματικά από το Β Παγκόσμιο και μετά, ενώ το επίπεδο των επενδύσεων αναλογικά είναι το χαμηλότερο για αυτό το χρονικό διάστημα. Οι δυνάμεις της αγοράς απέτυχαν θεαματικά να ενεργοποιήσουν αυτά τα λιμνάζοντα κεφάλαια και να τα μετατρέψουν σε πράσινες επενδύσεις που τόσο χρειάζεται η ανθρωπότητα. Αν το σκεφτεί κανείς καταλαβαίνει ότι χρειάζεται μια προσέγγιση τύπου New Deal σε διεθνή κλίμακα: ένας πολιτικός μηχανισμός που θα κατευθύνεται σε επίπεδο G20, που θα ανακυκλώνει τα πλεονάσματα χρηματοδοτώντας την καινοτομία και τις κοινωνικές υπηρεσίες.

Συνεπώς, η πραγματική δυσκολία δεν είναι να πειστούν οι άνθρωποι. Η πρόκληση είναι να καταφέρουμε να παραμερίσουμε τα εμπόδια που βάζει μια μικρή μειοψηφία της οποίας τα συμφέροντα εξυπηρετούνται από τη σημερινή, ασταθή καθεστηκυία τάξη.

Βοηθείστε να διαχωρίζεται η Αλήθεια από το Υποκινούμενο Ψεύδος – Ομιλία αποδοχής επίτιμου διδακτορικού από το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσσεξ

Την 20η Ιουλίου 2017, το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσεξ είχε την καλοσύνη να με ανακηρύξει Επίτιμο Διδάκτορα. Η Καθηγήτρια Άνρεα Κόρνγολ, Πρόεδρος της Σχολής Διεθνών Σπουδών του πανεπιστημίου, παρουσιάζοντάς με την Συνέλευση και στον Πρύτανη εξήγησε τους λόγους που αποφασίστηκε η απονομή του εν λόγω τιμητικού διδακτορικού ως εξής: “Για την προσφορά του στην κατανόηση της παγκόσμιας οικονομίας, τον γνήσιο διεθνισμό του, την ριζοσπαστική σκέψη του, και την παρρησία με την οποία υπερασπίζεται τις πολιτικές και του οικονομικές αντιλήψεις.” (Για ολόκληρη τη ομιλία της στα αγγλικά, πατήστε εδώ.]

Την 20η Ιουλίου 2017, το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσεξ είχε την καλοσύνη να με ανακηρύξει Επίτιμο Διδάκτορα. Η Καθηγήτρια Άνρεα Κόρνγολ, Πρόεδρος της Σχολής Διεθνών Σπουδών του πανεπιστημίου, παρουσιάζοντάς με την Συνέλευση και στον Πρύτανη εξήγησε τους λόγους που αποφασίστηκε η απονομή του εν λόγω τιμητικού διδακτορικού ως εξής: “Για την προσφορά του στην κατανόηση της παγκόσμιας οικονομίας, τον γνήσιο διεθνισμό του, την ριζοσπαστική σκέψη του, και την παρρησία με την οποία υπερασπίζεται τις πολιτικές και του οικονομικές αντιλήψεις.” (Για ολόκληρη τη ομιλία της στα αγγλικά, πατήστε εδώ.]

Με την Καθηγήτρια Άνδρεα Κόρνγολ, Πρόεδρο της Σχολής Διεθνών Σπουδών

Στην δική μου ομιλία αποδοχής του διδακτορικού τίτλου, είπα τα εξής (βλ. εδώ για το αγγλικό πρωτότυπο):

Το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσσεξ έχει τις ρίζες του σε μια, δυστυχώς, παρελθούσα εποχή. Σε μια εποχή όπου μια πιο φιλόδοξη από την σημερινή κοινωνία πίστευε, ορθώς, ότι κανένα λογιστικό σύστημα ή μέθοδος υπολογισμού κόστους-οφέλους δεν μπορεί να μετρήσει την αξία της μόρφωσης των πολλών. Μια κοινωνία που δεν θα διανοείτο ποτέ να χρεώνει, και υπερχρεώνει, τους νέους της πριν τους δώσει την ευκαιρία της μόρφωσης.

Τότε, στην δεκαετία του ’60, ιδρύθηκαν σε αυτή την χώρα πολλά νέα, σημαντικά, πανεπιστήμια με σκοπό όχι μόνον το άνοιγμα των θυρών της ανώτατης εκπαίδευσης στους έως τότε αποκλεισμένους νέους της εργατικής και μικρομεσαίας τάξης αλλά και στον επαναπροσδιορισμό του ρόλου της παιδείας.

Το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσσεξ ήταν από τα κορυφαία εκείνα νέα πανεπιστήμια και, από τότε, υπηρετεί την αρχική φιλοδοξία που το γέννησε με συνέπεια, ήθος και ανυπολόγιστη επιστημονική συνεισφορά.

Η φιλοσοφία που γέννησε το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσσεξ ήταν, και είναι, πραγματικά ενάρετη και ριζοσπαστική. Όμως, όπως λέγανε οι αρχαίοι μας, παν μέτρον άριστον. Ως νεαρός λέκτορας, θυμάμαι να με έχει συνεπάρει τόσο πολύ η φιλοσοφία που θεμελιώνει πανεπιστήμια όπως το Σάσσεξ που, σε μια ομιλία μου, μίλησα με υπερβολικό ενθουσιασμό για την δυνατότητα της μόρφωσης να εκπολιτίζει τις κοινωνίες. Όταν ολοκλήρωσα την ομιλία μου, με πλησίασε μια εκλεπτυσμένη, εύθραυστη, εντυπωσιακή ηλικιωμένη κυρία. Πριν ανοίξει το στόμα της, σήκωσε το ένα μανίκι της για να αποκαλυφθεί το τατουάζ στο χέρι της που αποδείκνυε ότι ήταν επιζήσασα του Άουσβιτς. Τότε μόνο μου είπε: «Οι δολοφόνοι μας ήταν μηχανικοί του Πολυτεχνείου που άκουγαν Μπετόβεν και διάβαζαν Γκέτε το βράδυ, στο σπίτι τους, αφού είχαν περάσει την μέρα τους στο κρεματόριο να μας αφανίζουν. Αγόρι μου, φοβάμαι ότι υπερ-εκτιμάς την αξία της παιδείας.» Κατόπιν απομακρύνθηκε αργά, αφήνοντάς με αποσβολωμένο, βουτηγμένο στην ντροπή που δημιούργησαν οι φράσεις της.

Η εκλεκτή εκείνη κυρία είχε απόλυτο δίκιο: Η μόρφωση δεν είναι ούτε αναγκαία ούτε ικανή συνθήκη για να γίνει ένας άνθρωπος καλός κ’αγαθός. Όμως, η μαζική παροχή μόρφωσης είναι αναγκαία συνθήκη για να εκπολιτιστεί μια κοινωνία. Και μπορεί να γίνει και ικανή συνθήκη εφόσον οι νέοι μάθουν, πάνω απ’ όλα, να προσεγγίζουν τη γνώση με κριτική διάθεση – να μην αποδέχονται μια διάλεξη, ένα εγχειρίδιο, μια θεωρία ως έχει και άνευ συστηματικής μελέτης και εμπεριστατωμένου σκεπτικισμού. Το κλειδί που ξεκλειδώνει τον πολιτισμό είναι η μόρφωση σε συνδυασμό πάντα με το επίγραμμα της Βασιλικής Εταιρείας του Λονδίνου: Nullius in verba! – με άλλα λόγια, δεν αποδέχομαι ποτέ κάτι επειδή κάποιος, ο οποιοσδήποτε, το πιστεύει.

Ίσως η πιο δυσάρεστη εμπειρία μου στην πολιτική ήταν οι στιγμές που λογικές, καλά επεξεργασμένες, προτάσεις προς ισχυρούς θεσμούς των οποίων οι αποφάσεις κρίνουν το μέλλον του κόσμου αγνοούνταν επειδή η συζήτησή τους απειλούσε τα συμφέροντα εκείνων που ήλεγχαν την ημερήσια διάταξη. Το ίδιο συμβαίνει και στις επιχειρήσεις. Όμως, καμία δημοκρατία, καμία επιχείρηση δεν μπορεί να ανθίσει μακροπρόθεσμα όταν νέες ιδέες απορρίπτονται ανεξάρτητα της αξίας τους λόγω της συντριπτικής δύναμης εκείνων που ωφελούνται από την καθεστηκυία κατάσταση ή τάξη.

Σήμερα, ίσως νομίσετε πως είστε στο κατώφλι που θα σας οδηγήσει από το πανεπιστήμιο στον «πραγματικό» κόσμο, στην «πραγματική» κοινωνία. Σας συνιστώ να μην αφεθείτε σε αυτή την φαντασίωση. Το Πανεπιστήμιο του Σάσσεξ δεν είναι, ως κοινωνικός χώρος, λιγότερο «πραγματικός» από τον χώρο των αγορών, των επιχειρήσεων ή του δημοσίου. Καθήκον σας είναι να μπολιάσετε τον «πραγματικό» κόσμο «εκεί έξω», εκεί που θα βρεθείτε από αύριο το πρωί, με την χωρίς φόβο ή πάθος κριτική στάση που διδαχθήκατε σε τούτο δω το πανεπιστήμιο. Καθήκον σας είναι να κάνετε τον κόσμο μας «πραγματικότερο», καλύτερο, πιο αποτελεσματικό και λιγότερο αυταρχικό μεταλαμπαδεύοντας σε αυτόν την ακαδημαϊκή μέθοδο διαχωρισμού της αδέκαστης αλήθειας από το σφάλμα που ωφελεί κάποιους ισχυρούς συμφεροντολόγους.

Για πολύ καιρό επιτρέψαμε τις πρακτικές της ποσοτικοποίησης ποιοτικών μεταβλητών, οι οποίες οδηγούν στην υποχώρηση της ποιότητας, να μεταναστεύουν από τις χρηματαγορές και τις πρακτικές της κρατικής γραφειοκρατίας στα πανεπιστήμιά μας. Η κουλτούρα της μανιώδους μέτρησης έχει καταφέρει πλήγμα στα πανεπιστήμιά μας και, κατ’ επέκταση, στις κοινωνίες μας – από το Εθνικό Σύστημα Υγείας έως και τον τρόπο που αποτιμούνται τα δομημένα ομόλογα ή σχεδιάζονται οι μακροοικονομικές πολιτικές. Από εσάς εξαρτάται να αναστρέψετε αυτή την πορεία.

Βέβαια, θα έρθετε αντιμέτωποι με βίαιες αντιδράσεις. Σημειώστε όμως τα σοφά λόγια του Όσκαρ Γουάιλντ: «… το να διαφωνεί κανείς με τα δύο-τρίτα των Βρετανών αποτελεί το βασικό προαπαιτούμενο της σωφροσύνης!»

Το μυστικό είναι να μην φοβάστε να είστε στην μειοψηφία. Να είστε, ταυτόχρονα, εποικοδομητικοί στις προτάσεις σας και ανυπότακτοι μπροστά στο φάσμα του αυταρχισμού και της ανοησίας – κριτικά ιστάμενοι απέναντι σε όλα αλλά και έτοιμοι να συνεργαστείτε με τους πάντες, με γνώμονα το κοινό καλό.

****

Στο πλαίσιο της βράβευσης, παραχώρησα την εξής συνέντευξη στο έντυπο του Πανεπιστημίου:

–Για πολλούς υπήρξατε ένας ήρωας, αν και καταδικασμένος, την περίοδο της υπουργίας σας το 2015. Είπατε ότι ήταν στιγμές που άλλαξαν την ιστορία. Τι ήταν αυτό που έκανε εκείνες τις στιγμές ιστορικές, για την Ευρώπη και για εσάς;

-Οι μόνοι ήρωες εκείνης της περιόδου ήταν οι Έλληνες που απέρριψαν με την ψήφο τους ένα ακόμα αρπακτικό δάνειο από την ΕΕ. Εγώ ήμουν απλά ο αγγελιαφόρος του μηνύματός τους.

Παρά τις απειλές ότι οι τράπεζες δε θα ξανανοίξουν και την εκστρατεία φόβου που εξαπέλυσαν τα μίντια , το 62% των ψηφοφόρων γύρισαν την πλάτη στα δάνεια και τις απειλές που τα συνόδευαν.

Ήταν μια ιστορική στιγμή επειδή για πρώτη φορά ένα χρεοκοπημένο έθνος βρήκε το κουράγιο να απορρίψει δάνεια που θα του επέτρεπαν να προσποιείται ότι όλα βαίνουν καλώς με αντάλλαγμα το κλείδωμα της πλειοψηφίας σε μια μόνιμη φυλακή χρέους. Ήταν μια ιστορική στιγμή και για έναν επιπλέον λόγο: έκανε δημόσια γνωστές τις αυταρχικές πεποιθήσεις ηγετικών στελεχών της Ευρώπης όπως του κ.Σόιμπλε που παραδέχτηκε ότι «οι εκλογές δεν επιτρέπεται να αλλάζουν την οικονομική πολιτική».

Τέλος, ήταν διπλά ιστορική στιγμή, γιατί η συντριβή της ελληνικής άνοιξης του 2015, επηρέασε την ψήφο υπέρ του Brexit, κάτι που με τη σειρά του έδωσε αέρα στα πανιά του Ντόναλντ Τραμπ στις ΗΠΑ.

-Τι μπορούν και τι πρέπει να φέρουν οι ακαδημαϊκοί στο χώρο της πολιτικής – μπορεί ένας ακαδημαϊκός να γίνει καλός πολιτικός;

-Οι ακαδημαϊκοί μπορούν να προσθέσουν συστατικά που λείπουν από την πολιτική: την προτεραιότητα στην ανόθευτη αλήθεια και τη φροντίδα ώστε οι προτάσεις και ιδέες που κατατίθενται στο δημόσιο διάλογο να περνούν από τη βάσανο της κριτικής. Οι επαγγελματίες πολιτικοί δυστυχώς εκπαιδεύονται να έχουν τις ακριβώς αντίθετες προτεραιότητες: είτε να υπερασπίζονται απόψεις που δεν πιστεύουν, είτε να απορρίπτουν καλές ιδέες μόνο και μόνο για να αποδομήσουν τον αντίπαλο που τις εκφράζει. Η πολιτική θα γινόταν πολύ πιο ωφέλιμη αν υιοθετούσε την ακαδημαϊκή λογική που κρίνει την ιδέα καθαυτή ανεξαρτήτως του ποιος την εκφράζει.. Αν μπορεί να γίνει ένας ακαδημαϊκός καλός πολιτικός; Αν καλός πολιτικός είναι ο μαιτρ της διαστρέβλωσης, ελπίζω πως όχι…

-Τα βασικά σας πτυχία ήταν στα μαθηματικά και τα οικονομικά. Τι σας οδήγησε σε αυτή την κατεύθυνση;

-Τα μαθηματικά είναι συναρπαστικά από αισθητικής άποψης. Ακόμα, για ένα πολιτικό ον, όπως εγώ, είναι καταπληκτικό το ότι μια θέση μπορεί να είναι σωστή ή λάθος μέσω της αποδεικτικής διαδικασίας και μόνο, ανεξαρτήτως της άποψης ή της οπτικής του καθενός. Όσο για τα οικονομικά, στις μέρες μας είναι τόσο απαραίτητα για κάποιον που ενδιαφέρεται να εκφράζει άποψη για την οργάνωση της κοινωνίας μας, όσο ήταν η Βίβλος το Μεσαίωνα.

-Τα οικονομικά για τη μεγάλη πλειοψηφία του κόσμου ήταν στεγνά και δυσνόητα. Τι έχει αλλάξει και σε τι βαθμό έχετε συνεισφέρει σε αυτή την αλλαγή;

-Ακόμα ο κόσμος πιστεύει ότι είναι στεγνά και δυσνόητα, και δικαίως, κατά τη γνώμη μου. Ο λόγος δεν είναι τα μαθηματικά που περιέχουν ή ότι είναι δύσκολο αντικείμενο καθαυτό. Ο λόγος είναι ότι για να λύσεις τα μαθηματικά που αφορούν τη ζωντανή καπιταλιστική οικονομία του σήμερα πρέπει να εισάγεις κρυφά αξιώματα τα οποία αφήνουν εκτός βασικές πλευρές του καπιταλισμού όπως η εργασία, το χρήμα, το χρέος. Λογικό είναι λοιπόν οι έξυπνοι φοιτητές να χάνουν το ενδιαφέρον τους να μάθουν θεωρητικά μοντέλα για τον καπιταλισμό που δεν έχουν σχέση με τη μελέτη του πραγματικού καπιταλισμού.

Στα έργα που έχω δημοσιεύσει σχετικά με την οικονομική θεωρία, τη θεωρία παιγνίων και την πολιτική οικονομία, προσπαθώ να διεγείρω τη φαντασία των φοιτητών, περιγραφοντας τη συναρπαστική πολιτική διάσταση που κρύβεται στα οικονομικά αξιώματα και καταδεικνύοντας τα αναλυτικά όρια των θεωριών αυτών.

-Ποιες πιστεύετε ότι είναι οι κυριότερες προκλήσεις για τους νέους που εισέρχονται στην αγορά εργασίας παγκοσμίως;

-Η κύρια πρόκληση είναι διαχρονική: Να βρει κανείς μια δουλειά που θα του άρεσε να την κάνει και δωρεάν και ταυτόχρονα να κερδίζει έναν αξιοπρεπή μισθό από αυτήν.

Η νέα πρόκληση, με βάση τις αλλαγές στην αγορά και την εργασία, είναι πως θα χρησιμοποιήσουμε έξυπνα την τεχνολογία, χωρίς να καταλήγουμε εμείς υπηρέτες της, και πως θα έχουμε την ελευθερία να διαλέγουμε τους συνεργάτες μας, στη δουλειά και στη ζωή γενικότερα.

-Πως βλέπετε το μέλλον της Ευρώπης και της Βρετανίας μετά το Brexit;

-Αρνούμαι να κάνω προβλέψεις, κυρίως επειδή καταλήγουν πολύ απαισιόδοξες. Αντίθετα, θεωρώ χρήσιμο να τονίσω τη σημασία που έχει να δουλέψουμε από κοινού, ώστε, ανεξάρτητα από το Brexit, η δημοκρατία, η αξιοπρέπεια, η οικονομική συνεργασία να γίνουν οι κινητήριες δυνάμεις για την Ευρώπη και τη Βρετανία και θα αντιμετωπίσουν τους δύο κινδύνους που μας απειλούν: τον τοξικό εθνικισμό και τον ζημιογόνο αυταρχισμό του κατεστημένου.

-Πρόσφατα γράψατε ότι η απάντηση στην παγκοσμιοποίηση και τον απομονωτισμό είναι ο αυθεντικός διεθνισμός – ένα διεθνές «New Deal» που θα συμπεριελάμβανε τη συγκέντρωση παγκόσμιων αποθεματικών. Πως μπορείτε να πείσετε τα έθνη για αυτή την πρόταση;

-Δεν είναι δύσκολο να πειστεί η πλειοψηφία στις περισσότερες χώρες του κόσμου για την ανάγκη ενός διεθνούς “New Deal”. H κοινή λογική είναι με το μέρος μας: Ζούμε σε ένα κόσμο που παράγει τα μεγαλύτερα αποθεματικά από το Β Παγκόσμιο και μετά, ενώ το επίπεδο των επενδύσεων αναλογικά είναι το χαμηλότερο για αυτό το χρονικό διάστημα. Οι δυνάμεις της αγοράς απέτυχαν θεαματικά να ενεργοποιήσουν αυτά τα λιμνάζοντα κεφάλαια και να τα μετατρέψουν σε πράσινες επενδύσεις που τόσο χρειάζεται η ανθρωπότητα. Αν το σκεφτεί κανείς καταλαβαίνει ότι χρειάζεται μια προσέγγιση τύπου New Deal σε διεθνή κλίμακα: ένας πολιτικός μηχανισμός που θα κατευθύνεται σε επίπεδο G20, που θα ανακυκλώνει τα πλεονάσματα χρηματοδοτώντας την καινοτομία και τις κοινωνικές υπηρεσίες.

Συνεπώς, η πραγματική δυσκολία δεν είναι να πειστούν οι άνθρωποι. Η πρόκληση είναι να καταφέρουμε να παραμερίσουμε τα εμπόδια που βάζει μια μικρή μειοψηφία της οποίας τα συμφέροντα εξυπηρετούνται από τη σημερινή, ασταθή καθεστηκυία τάξη.

Help separate truth from motivated error: My acceptance speech at Sussex University on the occasion of an honourary doctorate conferment

On 20th July 2017, the University of Sussex conferred upon me the degree of Doctor of the University Honoris Causa. Professor Andrea Cornwall, who kindly presented me to the Chancellor and the Congregation, explained the rationale of the award: “[F]or his contribution to our understanding of the global economy, for his advocacy of an authentic internationalism, for his intellectual bravery and his passion for making a difference.” (For Professor’s full speech, click here.] I wish to thank Professor Cornwall, Chancellor Sanjeev Bhaskar, and everyone at Sussex for that remarkable honour.

Pictured with Professor Andrea Cornwall

In my acceptance speech, I said the following:

Chancellor, ladies and gentlemen, I am deeply grateful for the honorary doctorate so kindly conferred upon me by such a fine university.

The University of Sussex harks back to a, sadly, bygone era when a more confident society, convinced that no price system, no cost-benefit analysis, could ever capture the value of educating the many, and unwilling to indebt its poorer children as a price for their education, built new universities with a mission to re-think the purpose of higher education.

As a young lecturer, I remember taking that mantra a little too far.

After delivering a talk on the civilising power of university education, an elegant, elderly woman approached me. Before uttering a single word, she lifted her sleeve to show me her Auschwitz tattoo. “Our killers were well educated”, she told me. “They were engineers who read Goethe and listened to Beethoven after a day spent exterminating us. You are over-valuing education’s civilising capacities my son”, she said before walking away, leaving me stranded, ashamed.

She was right: An education is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for a person to be good. But it is a necessary condition for a society to be civilised. And it can become sufficient as long as the young are encouraged to digest education critically; never to internalise a lecture, a textbook, a theory without intense scrutiny; always to be guided by the Royal Society’s motto: Take no one’s word for it. Nullius in verba!

Perhaps the most infuriating experience I had in politics was when proposals were ignored without serious criticism just because they inconvenienced those setting the agenda. The same happens in the corporate world. No democracy, indeed no company, can flourish when good ideas are crushed by the brute force of those served well by the status quo.

Today, you may be tempted to think that you are trading the ‘ivory towers’ for the ‘real world’. Resist that thought! Sussex University is no less real than the world you are about to enter. Indeed, your duty is to infect the ‘real world’ with the method of dispassionate criticism that you were taught here. Your responsibility is to make the world more real, and worthier, by bringing to bear upon it the academic method of separating truth from motivated error.

For too long we have allowed the quantification practices, that devalue everything, to migrate from markets and government to academia. The culture of incessant measurement damaged our universities and, by extension, our societies – from the NHS to the way financial products are priced and macroeconomic policy designed. It is up to you to reverse this.

You will, of course, encounter fierce opposition. But mark Oscar Wilde’s wise counsel: “…to disagree with three-fourths of the British public is one of the first requisites of sanity”.

The secret is never to fear being in a minority. It is to be simultaneously constructive in your proposals and disobedient in the face of inanity – critical of everything but ready to cooperate with everyone.

To succeed, a rational plan is key, as is a capacity never to forget Mike Tyson’s unforgettable line: “They all have a plan, until I punch them in the nose!”

Chancellor, I shall do all I can to maintain my relationship with the University and to promote to the best of my ability your necessary and worthy endeavours.

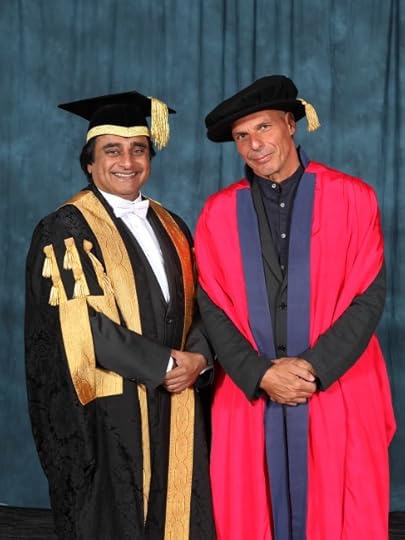

With the Chancellor, author and actor Sanjeev Bhaskar.

Following the Ceremony, I gave several interviews to the Sussex University media. Here is one with Jacqui Bealing, of SU News

Academics bring rational scrutiny to politics, says Yanis Varoufakis

Yanis Varoufakis , Professor of Political Economy and Economic Theory at the University of Athens University, is to be awarded the honorary doctorate, Doctor of the University, at the University of Sussex’s summer graduation ceremony on 20 July.

Professor Varoufakis served as Greek Finance Minister in 2015. He is the author of several books on political and economic topics, his most recent, Adults in the Room: My Battle with Europe’s Deep Establishment (2017), charts his experience of his country’s financial crisis.

You were hailed as a hero, albeit a doomed one, when you were Greek finance minister in 2015. You said this was a moment when history changed. What made it so momentous – both for Europe and for you?

The only heroes of 2015 where the Greek voters who voted to reject yet another predatory ‘bailout’ loan from the EU. I was merely their messenger.

Despite the threats that the banks would never open again, and under a barrage of media scaremongering that Greece would be thrown to the wolves if they dared insist on saying NO to more loans, 62% turned down the loans and their backs on the threats.

It was an historic moment because it was the first time that a bankrupt nation found the courage to turn down loans that would have allowed it to pretend we were solvent at the expense of pushing the majority of the people into permanent debt-bondage. It was also historic because it exposed the illiberality of Europe’s leading politicians – e.g. the German finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, who confessed to believing that “elections should not be allowed to change economic policy”.

It was doubly historic because the eventual crushing of that Greek Spring of 2015 gave a major impetus to Brexit which, in turn, blew fresh wind into Donald Trump’s sails.

What can and should academics bring to the world of politics – do they make good politicians?

Academics can bring one ingredient into politics that is sorely missing: a concern for the unalloyed truth and for subjecting proposals and new ideas to rational scrutiny. Professional politicians are, unfortunately, trained to do the opposite: to express professionally views they either disagree with or misunderstand in a bid to debase their opponent’s argument independently of its merits! Politics would be much improved if infused with a more scholarly attitude toward the merit of views, rather than on who has uttered them. Do academics make for good politicians? I hope not, if by “good politician” you mean an expert in obfuscation…

You studied mathematics and economics for your undergraduate degree. What led to that interest?

Mathematics is aesthetically fascinating. It is also greatly intriguing to a political animal, like myself, for one reason: It is the only realm in which truths can be proven right or wrong, independently of opinion or perspective. As for studying economics, in our days it is that which Bible studies was in the Middle Ages: essential vocabulary for anyone interested in participating in public debates about how society should be organised.

Economics had a reputation for being dry and incomprehensible to the vast majority. What changed that – and how much of it was down to you?

It still has this reputation, rightly I believe. The reason is not that it is too mathematical or too hard. The reason is that, in order to solve the mathematics seeking to capture the essence of really-existing capitalism, one needs to introduce axioms (some of them hidden) that rule out… capitalism’s most essential aspects (e.g. the labour process, money, debt). Understandably, the smarter students realise this and lose interest in models of capitalism engineered to be irrelevant to anyone with an interest in… capitalism.

In my work, especially in several textbooks on economic theory, game theory and political economy that I have published, I have tried to re-energise the students’ imagination by pinpointing the fascinating politics hiding behind the economists’ basic axioms and by illustrating the analytical limits of the theories at hand.

What do you consider to be the major challenges for young people entering the global workforce?

The main challenge remains a time-invariant one: To find a job that you would love to do for free, and still get paid a decent salary to do!

The new challenge, presented by changes in the labour process and market, is how to use technology smartly, without ending up its servant, and remain at liberty to choose one’s partners at work – and, of course, in life more broadly.

What do you see as the future for Britain in Europe after Brexit, and for the future of Europe?

I refuse to issue predictions, if only because they will in all likelihood turn out to be gloomy. Instead, I would like to emphasise the importance of working together at ensuring that, Brexit or not, democracy, decency, and economic cooperation become a pan-European force for good that counters in Europe and in Britain the toxic powers of nationalism, nativism as well as the establishment’s incompetent authoritarianism.

You recently wrote that the answer to globalism and isolationism is an authentic internationalism – an “International New Deal” that would involve a pooling of global savings. How would you convince nations that this is all in their best interest?

Convincing the majority of people in a majority of countries that an International New Deal is in their interests is not intrinsically hard. Logic and common sense are on our side. Think about it: We live in a world that generates the highest level of savings and the lowest level of investment since the 2nd World War (as a proportion of planetary income). Market forces have failed spectacularly to energise these idle savings and to turn them into investment into the green technologies that humanity craves. One only needs to state this fact to realise that we need a New Deal approach at a planetary level: a political mechanism, guided by an accord at the G20 level, that soaks up the excess savings and funds the planet’s innovators as well as our communities’ maintainers (e.g. the good women and men that look after the elderly, educate the young, service the sewers, etc.)

The true difficulty, therefore, is not to convince the people. The momentous task is to push aside the vicious obstructionism of the tiny minority whose petty interests are served by the current, unsustainable status quo.

(GO TO 1 hour 8 Min and 16 Seconds)

Στις αγορές, πτωχευμένοι 2.0 – ΕφΣυν, 22 Ιουλίου 2017

Κυβέρνηση, τρόικα και κατεστημένο προσδοκούν πώς και πώς την πολυπόθητη έξοδο στις αγορές, υποσχόμενοι στους χειμαζόμενους εν μέσω θέρους πολίτες ότι αυτή η «επιτυχία» θα φέρει την άνοιξη για όλους. Πρόκειται για επικίνδυνο ψέμα που κάθε σκεπτόμενος άνθρωπος έχει καθήκον να αποδομήσει.

Κυβέρνηση, τρόικα και κατεστημένο προσδοκούν πώς και πώς την πολυπόθητη έξοδο στις αγορές, υποσχόμενοι στους χειμαζόμενους εν μέσω θέρους πολίτες ότι αυτή η «επιτυχία» θα φέρει την άνοιξη για όλους. Πρόκειται για επικίνδυνο ψέμα που κάθε σκεπτόμενος άνθρωπος έχει καθήκον να αποδομήσει.

Για αυτό τον λόγο, έκατσα σήμερα να γράψω μια ανάλυση του τι σημαίνει έξοδος στις αγορές και γιατί δεν έχει καμία σημασία είτε βγούμε σ’ αυτές είτε όχι. Ομως, πριν αρχίσω να γράφω το άρθρο μου, με έπιασε μια στενοχώρια που με εμπόδιζε – μια στενοχώρια που οφειλόταν στο ότι αναγκαζόμουν να γράψω ακριβώς τα ίδια πράγματα με εκείνα που έγραφα το πρώτο εξάμηνο του… 2014.

Σκέφτηκα, λοιπόν, αντί να ξαναγράψω τα ίδια από την αρχή, να χρησιμοποιήσω αποσπάσματα εκείνων των άρθρων – καταδεικνύοντας ότι στα ίδια ψεύδη πρέπουν οι ίδιες απαντήσεις.

Πράγματι, την 20ή Φεβρουαρίου 2014, σε μια περίοδο που η τότε κυβέρνηση ύφαινε το αφήγημα του greek success story στον καμβά της φιλολογίας περί εξόδου στις αγορές, δημοσίευσα άρθρο στο protagon.gr με τίτλο «Στις αγορές, πτωχευμένοι!». Το άρθρο αναφερόταν στο σχέδιο του Βερολίνου για την Ελλάδα των επόμενων ετών. Ονομάζοντάς το «3ο, κρυφό, Μνημόνιο» αναφερόμουν στα τρία βασικά συστατικά του:

Πρώτον, ότι «δεν περιέχει το κούρεμα, το οποίο θα μπορούσε να βγάλει το ελληνικό κράτος από τη διαχρονική κατάσταση χρεοκοπίας (κοινώς, την αδυναμία να εξυπηρετεί τα χρέη του μακροπρόθεσμα, ακόμα και μετά από μια γενναία επιμήκυνση μετά μείωσης του επιτοκίου κατά μισή με μία μονάδα)».

Δεύτερον, «δεν περιέχει καμία πρόβλεψη για κοινό, ευρωζωνικό χρέος (π.χ. ευρωομόλογα)».

Και, τρίτον, «προσπαθεί να πείσει ότι δεν θα χρειαστούν νέα μνημονιακά δάνεια καθώς η έξοδος στις αγορές είναι ζήτημα χρόνου».

Σας θυμίζει κάτι εκείνο το σχέδιο; Δεν είναι πανομοιότυπο με αυτά που σήμερα παρουσιάζει η τρόικα, αλλά και η ελληνική κυβέρνηση, ως το νέο greek success story; Δεν εγείρει ακριβώς το ίδιο ερώτημα με εκείνο που έθετα στις 20 Φεβρουαρίου 2014, δηλαδή: «Γιατί βοηθά να δανειστούμε από ιδιώτες όσο παραμένουμε πτωχευμένοι, ακόμα κι αν εκείνοι –για δικούς τους λόγους– μας δανείσουν;»

«Περιληπτικά», εξηγούσα τον Φεβρουάριο του 2014, «ο άξονας του γερμανικού σχεδίου για την Ελλάδα είναι ένας: η συνέχιση της στρατηγικής των προηγούμενων τεσσάρων ετών, δηλαδή η καθυστέρηση της παραδοχής ότι η Ελλάδα αδυνατεί να επιβιώσει εντός των “κανόνων” που το Βερολίνο θεωρεί “απαράβατους”. Για να μη χρειαστεί να παραδεχτούν την αλήθεια, προετοιμάζουν ένα νέο “παράδοξο” Μνημόνιο, όπου το μεγάλο ποσοστό των νέων δανείων θα έρχεται από τις αγορές σε ένα πτωχευμένο Δημόσιο, ελέω της σιωπηλής παρέμβασης της ΕΚΤ.

Αυτό λοιπόν που προτείνεται στον ελληνικό λαό, αντί για ένα βιώσιμο σχέδιο για την επόμενη δεκαετία, είναι το να συναινέσει στην έξοδό του στις αγορές όσο το κράτος του είναι πτωχευμένο, και με προοπτική να βουλιάζει όλο και πιο πολύ στον βούρκο της μακροπρόθεσμης πτώχευσης αλλά, βέβαια, παραμένοντας στις αγορές. Θεωρώ εθνική ανοησία την συναίνεσή μας σε αυτό το πλάνο».

Εξι μέρες αργότερα, σε άλλο άρθρο, αναφέρθηκα σε ερώτημα φιλο-τροϊκανών σχολιαστών προς εμένα με το οποίο με ρωτούσαν: «Οταν η Ιταλία, η Αυστραλία και άλλες σοβαρότερες της δικής μας χώρες δανείζονται με επιτόκια μεταξύ 4% με 5%, εσύ Βαρουφάκη με τι επιτόκια θα ήθελες να δανειζόμαστε;». Σε νέο άρθρο της 26ης Φεβρουαρίου 2014 τους απάντησα ως εξής:

«Με κανένα επιτόκιο! Ούτε καν με αρνητικό επιτόκιο! Ο πτωχευμένος δεν δικαιούται να δανείζεται πριν το χρέος του γίνει βιώσιμο, με οποιονδήποτε τρόπο. Η άποψη πως το πτωχευμένο ελληνικό Δημόσιο θα πρέπει να συνεχίζει να δανείζεται κι έχει ο Θεός (ή η κ. Μέρκελ) για το πότε, το εάν και το πώς θα διαγραφεί ένα μεγάλο μέρος του χρέους αποτελεί ασέλγεια επί της λογικής. Ιδίως στο πλαίσιο μιας Ευρώπης που καθημερινά αποδεικνύεται πανέτοιμη να σπρώχνει το πρόβλημα στο μέλλον, μεγεθύνοντάς το».

Βέβαια, οι τρόικες εξωτερικού και εσωτερικού προσποιήθηκαν ότι δεν καταλάβαιναν. Ετσι, τον επόμενο Απρίλιο (του 2014) η κυβέρνηση Σαμαρά-Βενιζέλου-Στουρνάρα «βγήκε στις αγορές» εκδίδοντας δύο ομόλογα τα οποία μάλιστα βρήκαν ένθερμους αγοραστές – με αποτέλεσμα ολόκληρη η καθεστηκυία τάξη να πάλλεται από ενθουσιασμό για την έξοδο από την κρίση κ.λπ. κ.λπ.

Λίγο πριν από εκείνη την ηρωική, αλλά πύρρειο, έξοδο στις αγορές, σε άλλο άρθρο μου με τίτλο «Εξοδος στις αγορές: τι σημαίνει και γιατί γίνεται τώρα», αυτή τη φορά στο «Ηot Doc» της 5ης Απριλίου 2014, έγραφα:

«Κυβέρνηση και τρόικα πανηγυρίζουν την “έξοδο στις αγορές”. Την ίδια ώρα μάς λένε ότι το Δημόσιο έχει σημαντικό πρωτογενές πλεόνασμα, όπερ μεθερμηνευόμενον: δεν έχει λόγο να δανείζεται για μισθούς, συντάξεις ακόμα και για… προεκλογικό “κοινωνικό μέρισμα”. Τότε γιατί δανειζόμαστε από τις αγορές πριν καλά-καλά λάβουμε τις τελευταίες δόσεις του Μνημονίου 2;… [Γιατί] μας βγάζουν στις αγορές πτωχευμένους βυθίζοντας τη χώρα πιο βαθιά στην πτώχευση;

»Γιατί το κάνουν; Η απάντηση κρύβεται σε μια αντίφαση: Επειδή από τη μία η τρόικα πρέπει να εξασφαλίσει ένα νέο τεράστιο πακέτο δανεικών για την Ελλάδα (καθώς η πτώχευση του Δημοσίου μας αυξάνεται εκθετικά), ενώ από την άλλη το Βερολίνο δεν θέλει επ’ ουδενί να πει στον Γερμανό πολίτη ότι θα δώσουν κι άλλα δανεικά στο ελληνικό Δημόσιο. Πώς μπορεί και να μας επιβάλουν νέο δανεισμό και να πουν στους Γερμανούς πολίτες ότι τέρμα τα πακέτα “διάσωσης” της Ελλάδας; Είναι απλό: το Μνημόνιο 3 θα χρηματοδοτεί ως επί το πλείστον από τις… αγορές».

Υπήρχε κι άλλη μία διάσταση που εξηγούσε την πρεμούρα για έξοδο στις αγορές, την οποία ανέπτυξα ως εξής:

«Γιατί όμως βιάζονται τόσο να εκδώσουν ομόλογα τώρα, πριν καλά-καλά λάβουν τις τελευταίες δόσεις από το Μνημόνιο 2; [Για να]… βοηθήσουν κι άλλο τους αγαπητούς τους τραπεζίτες! Πώς βοηθά τους τραπεζίτες η έξοδος στις αγορές;

»Οι ελληνικές τράπεζες δεν διαθέτουν πλέον ομόλογα του Δημοσίου (μετά και την κατ’ ευφημισμόν “επαναγορά χρέους” του Δεκεμβρίου 2012). Αυτό τους κόβει τα πόδια καθώς οι τράπεζες χρησιμοποιούν κρατικά ομόλογα ως εχέγγυα για να δανείζονται από την ΕΚΤ. Τώρα, θα δανειστούν η μία από την άλλη, θα αγοράσουν ομόλογα και έτσι θα βγάλουν κέρδη εις βάρος του Ελληνα και Ευρωπαίου φορολογούμενου.

»Πώς; Με δύο τρόπους: (α) Δανείζονται με επιτόκιο λιγότερο του 1% η μία από την άλλη και δανείζουν στο Δημόσιο (αγοράζοντας τα νέα ομόλογα) με 5% και (β) καλύπτουν τα μεταξύ τους δάνεια καταθέτοντας τα ομόλογα αυτά στην ΕΚΤ για να λάβουν ρευστό χρήμα με επιτόκιο… 0,25%. Ετσι θα ενταθεί η αλληλεξάρτηση πτωχευμένων τραπεζών και του πτωχευμένου Δημόσιου την ώρα που τράπεζες, τρόικα και κυβέρνηση θα πανηγυρίζουν το greek success story!

Στον επίλογο μάλιστα εκείνου του άρθρου αναρωτιόμουν: «Τι ήταν αυτό που ανέκαθεν χαρακτήριζε την Ελληνική Κλεπτοκρατία;» Και απαντούσα:

«Υπερδανεισμός του κράτους (τον οποίο φορτωνόταν ο αδύναμος φορολογούμενος) και κάποια ψίχουλα παροχών (από τα δανεικά) προεκλογικά ώστε οι εκπρόσωποι της κλεπτοκρατίας να επανεκλέγονται. Τι χαρακτηρίζει τη Νέα, Μνημιώδη, Μνημονιακή Κλεπτοκρατία σήμερα; Νέος δανεισμός του βαθιά πτωχευμένου κράτους από τις αγορές, υπό την αιγίδα και με τη βοήθεια της τροϊκανής “τεχνογνωσίας”, και κάποια ψίχουλα παροχών (από τα δανεικά) προεκλογικά ώστε οι εκπρόσωποι της Νέας Κλεπτοκρατίας να μην καταποντιστούν στις ευρωεκλογές».

Και κατέληγα με τα εξής:

Υπό αυτή την έννοια, η επιστροφή στις αγορές δεν είναι παρά ολική επιστροφή στην παραδοσιακή πρακτική της εγχώριας κλεπτοκρατίας, με τη μεγάλη όμως διαφορά ότι, σήμερα, το κράτος είναι πιο βαθιά πτωχευμένο από ποτέ, η ελληνική κοινωνία ισχνότατη και στα όρια της εξαθλίωσης, και η άρχουσα κλεπτοκρατία δεσμευμένη από τον “ξένο παράγοντα” περισσότερο απ’ όσο οι μετεμφυλιακές κυβερνήσεις από τον κ. Πιούριφοϊ

Αφιερωμένο εξαιρετικά στους συντρόφους με τους οποίους πείσαμε τον ελληνικό λαό τον Γενάρη του 2015 να θέσουμε τέλος σε αυτήν τη μισανθρωπική κατάσταση.

Σημείωση: Απάνθισμα όλης εκείνης της προ του 2015 αρθρογραφίας μου εμπεριέχεται στο βιβλίο μου «Η Γένεση της Μνημονιακής Ελλάδας», Εκδόσεις Gutenberg, 2014

Για την ιστοσελίδα της ΕφΣυν, πατήστε εδώ

22.07.2017, 14:10 | Ετικέτες: Γιάνης Βαρουφάκης, κυβέρνηση, δάνεια, Μνημόνιο

July 20, 2017

“I was right about the debt, and you know it!” – My reply to Kathimerini’s latest tirade

In a recent article entitled “Varoufakis and the 2015 debt talks – behind closed doors”, published on the English language site of Kathimerini, Yannis Paleologos is putting forward an innovative new criticism of my 2015 negotiating stance regarding Greece’s public debt.

His criticism’s first leg is standard troika-speak, insisting that by pressing for a deep re-structuring of Greece’s public debt I brought “the country to the brink of absolute disaster”. As this is uninteresting and repetitive, I shall concentrate on the second, more novel, leg of his accusation: That I clashed with the troika even though my analysis of the Greek debt burden was not that dissimilar to the pro-troika Samaras-Venizelos government (or to Mr Klaus Regling’s, the ESM’s Managing Director).

To substantiate his claim (that I was unadventurously mainstrean in my analysis while belligerent in my stance), Mr Paleologos is quoting from a non-paper that I circulated prior to the Eurogroup meeting of 16th February, 2015. The reader is encouraged to read Mr Paleologos’ article in full with the following caveats in mind, before assessing his claims about my debt analysis:

The non-paper

When Mr Paleologos writes the following,

However, a document… that had been circulated by the Greek side at a Eurogroup meeting on February 16, 2015, which is at Kathimerini’s disposal, shows that Varoufakis, despite his public pronouncements, was much closer to the positions of the reviled Samaras and Venizelos.

… he is neglecting to mention that it was I who had made public the said non-paper on 18th February 2015 in the context of my transparency campaign for which I was vilified by the troika, and by Kathimerini, on the grounds that I broke with the tradition of Eurogroup ‘confidentiality’. Glad, and proud, that I released this and other important material pertaining to those crucial Eurogroup meetings, I am happy that Mr Paleologos has, at last, come around to reading and using it.

The motivated ‘misunderstanding’ fuelling crippling austerity

Mr Paleologos quotes my non-paper’s section entitled ‘A misunderstanding’ in which I explain that public opinion had the wrong impression of the effective level of Greece’s public debt in that, in present value terms, Greece’s public debt was closer to 135% of GDP (in contrast to the headline 175% figure that referred to its face-value). Noting that my estimate was similar to that of the Samaras-Venizelos-Regling estimate, Mr Paleologos asks:

So, the question inevitably arises: if Varoufakis believed all this, then why did he lead the country to the brink of absolute disaster…?

Setting aside the inflammatory character-assassination language so beloved by Kathimerini, the answer to his real question (Why did Varoufakis clash with the troika over debt restructuring if his debt analysis was similar to theirs?) is, of course, obvious and clearly stated in a paragraph that he only partially re-produces:

“Indeed, if Greece’s debt was calculated in Net Present Value (NPV) terms, say with a 5% discount factor, the Debt-to-GDP ratio would already be as low as 133% of GDP…, and reach 127% in 2020 (as expected by the IMF in nominal term) with a primary surplus maintained at 1.5% of GDP instead of 4.5%.” [Emphasis added]

In short, my argument was that, even by the troika’s own analysis, we did not need a primary surplus target of more than 1.5% in order to stabilise, and indeed, contain Greece’s public debt. The debt restructuring I was demanding was crucial in order (a) to reduce the short-term fiscal stress on the Greek state’s finances, and (b) to signal to the world of investors that our public debt is no longer going to be at levels that they need worry about. In other words, my emphasis was, correctly, on pointing out that the troika’s obsession with primary surplus levels between 3.5% and 4.5% was both absurd and damaging.

The need to end austerity is what my 2015 clash with the troika was about: An extract from a complementary non-paper

For the benefit of Mr Paleologos, and our readers, here is how I explained to my fellow finance ministers in he Eurogroup meetings of February 2015 why ending austerity was essential to restoring Greek debt sustainability (yes, the meetings when I was accused of speaking… macroeconomics!). The following is an extract from another, slightly more technical, non-paper I tabled during the same week of February 2015:

“Through massive sacrifices caused by a depression-level slump, Greece is now running a structural primary budget surplus of around 1.5 percent of GDP. Our new government is not calling for a return to primary deficits. We are merely proposing that the primary surplus be stabilised at the current structural level of 1.5%, rather than raising it to between 3.5 and 4.5 percent of GDP for the medium to long term, a fiscal stance that has few precedents in economic history.

Any primary surplus target above 1.5% will lead to new shortfalls in GDP – exactly as happened since 2010 due to the underestimation of the fiscal multipliers that the IMF now readily admits to. Looking at the experience of 2010-2014 it is clear that a reasonable estimate for our multiplier is well above 1. Let us consider what will happen if our government were to agree with the demands for a primary surplus of 3.5% to 4.5%.

Any given increase in primary surplus (call it X) must equal the reduction in government spending involved (-Y) times (1-mt), where m is the multiplier and t is the effect of a one-euro change in GDP on tax revenues and/or cyclically linked spending like unemployment benefits. [i.e. X = Y(1-mt)]

Most economists, including the IMF’s, these days agree that the Greek economy’s m is around 1.3 and its t around 0.4. So, to get to the high primary surplus targets that the previous agreement has set, i.e.to set X to between 2% and 3% (so that our primary surplus is boosted from 1.5% to 3.5% or 4.5%), we need to impose new austerity to the tune of 4% and 6.25%. But given a multiplier greater than one, this would lead to a loss between 8 and 11 billion euros. A most self-defeating strategy.

In conclusion, it would be an own goal for both Greece and its creditors to maintain a primary surplus of more than 1.5%. This should be our red line, not just Greece’s red line but the Eurogroup’s as a whole.

To paraphrase Bill Clinton, “it was the new austerity, stupid!” (which the troika was obsessively insisted upon) that led to the 2015 clash with the troika. And it was our defeat that led, via the implementation of the austerity I fought against, to the tragic continuation of the Greek social economy’s debt-deflationary cycle to this day and beyond.

To sum up, my argument and proposal in those Eurogroup meetings was simple:

First, less austerity (i.e. a primary surplus of no more than 1.5% of GDP) would help contain Greece’s debt, rather than the opposite.

Secondly, there was an urgent need to frontload reductions in the debt repayments of the Greek government (e.g. in 2015 I had to find €22 billion euros just for debt repayments, out of a state revenues of no more than €47 billion).

Thirdly, I was proposing debt swaps that would link Greece’s repayments to our nominal GDP level and growth rates, in a manner that creates incentive compatibility between the Greek government and its lenders (turning the latter into equity partners of Greece’s recovering economy)

Throwing in a baseless claim, for good measure

Of course, Mr Paelologos, not content to ‘misunderstand’ my point about the importance of lowering the primary surplus target to 1.5% and the ingenuity of the proposed debt swaps (see here and here), chose to refer extensively to the amusing musings of Paul Kazarian, of Japonica Partners – a gentleman that had the unfortunate epiphany of investing in Greek government bonds at a time when their devaluation was inevitable.

While I sympathise with any investor clinging on to wishful thinking regarding his portfolio, and thus respect Mr Kazarian’s protestations that Greece’s debt is sustainable, it is remarkable that Mr Paleologos chose to adopt Mr Kazarian’s extraordinary claim that my proposed debt swaps would have increased the costs of Greece’s public debt servicing. This results from no interpretation of the numbers consistent with even primary school arithmetic. The only reason Mr Kazarian’s views have been given another airing by Kathimerini is that they were deemed useful in putting together another instalment in their ‘Get Varoufakis!’ campaign.

Conclusion

At a time when the IMF is about, once again, to proclaim Greece’s debt unsustainable, and the Greek government is being pushed to issue new bonds despite its insolvency, the Greek oligarchy’s official organ, Kathimerini, is continuing its valiant efforts to distort the facts about my 2015 negotiation with the troika. My recommendation to readers is: Read their articles carefully and critically. For their quasi-skilled distortions are full of insight regarding the troika’s dead end in the face of a Greek ‘program’ that was imposed with as much brutality and the incompetence on which it was based.

Footnote

Whether it was I who caused the clash with the troika or the troika that used all ways and means to suffocate our government even before we were elected, determined to avoid a serious restructuring of Greece’s public debt, I shall leave to the reader to judge. My recent book Adults in the Room contains all I need to say on the matter.

July 17, 2017

Συνέντευξη ΣΚΑΙ, με τον Γιώργο Αυτιά, για το παράλληλο σύστημα πληρωμών

ΑΝΤΙ ΣΧΟΛΙΟΥ: Κάποτε o Άπτον Σινκλαίρ είχε πει: “Μου είναι δύσκολο να κάνω κάποιον να καταλάβει κάτι όταν ο μισθός του εξαρτάται από το να μην το καταλάβει.” [‘It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.’]

July 11, 2017

Αλλη μία επέτειος του «όχι» επιβεβαιώνει την ανάγκη παράλληλου συστήματος πληρωμών

08.07.2017, 14:00 |

Από το 2010 όλες οι ελληνικές κυβερνήσεις, όλοι οι υπουργοί Οικονομικών ήρθαν αντιμέτωποι με παράλογες απαιτήσεις από δανειστές που δεν δίστασαν να τους εκβιάσουν στη βάση τού: «Είτε περνάτε τα μέτρα που σας υπαγορεύουμε είτε σας κλείνουμε τις τράπεζες και σας πετάμε από το ευρώ».

Η οργανωμένη άμυνα της χώρας απέναντι στον ωμό αυτόν εκβιασμό ήταν, και είναι, καθήκον κάθε κυβέρνησης, κάθε υπουργού Οικονομικών.

Και η μόνη γραμμή άμυνας σε αυτόν τον εκβιασμό, για μια κυβέρνηση που δεν έχει στόχο να βγει από το ευρώ, είναι ένα παράλληλο σύστημα πληρωμών.

Χωρίς τέτοιο σύστημα, η Ελλάδα θα παραμένει στο έλεος δανειστών που, εν γνώσει τους, επιβάλλουν μέτρα που ερημοποιούν τη χώρα ανεξάρτητα από το ποιο κόμμα (υποτίθεται ότι) «κυβερνά».

Το παράλληλο σύστημα πληρωμών και οι υποσχετικές (IOU): μια ιδέα που η τρόικα θεωρεί εξαιρετική εφόσον ωφελεί μόνο τα δικά της τα παιδιά.

Από τότε που ξέσπασε η κρίση εφαρμόστηκε και στην Ελλάδα το σύστημα παράλληλων πληρωμών με υποσχετικές (IOU) για ποσά δεκάδων δισεκατομμυρίων ευρώ.

Η κυβέρνηση Παπανδρέου εξέδωσε υποσχετικές (IOU) για να πληρώνει προμηθευτές του Δημοσίου το 2010.

Πιο πριν, από το 2008, τότε που ξέσπαγε η τραπεζική κρίση, η ΕΚΤ επέτρεψε στις ελληνικές τράπεζες (και σε πολλές ευρωπαϊκές) να εκδώσουν δισεκατομμύρια υποσχετικών (IOU) που βέβαια θα ήταν άνευ αντικρίσματος (δεδομένου ότι οι τράπεζες είχαν ουσιαστικά πτωχεύσει) αν δεν επιβαλλόταν στο ελληνικό υπουργείο Οικονομικών να τις εγγυάται.

Εν ολίγοις, από το 2009 έως σήμερα η Εθνική, η Alpha, η Eurobank και η Πειραιώς επιβιώνουν στη βάση κρατικών υποσχετικών (IOU) των οποίων η ονομαστική αξία, έως και σήμερα, ξεπερνά τα 50 δισ. ευρώ!

Οταν λοιπόν η τρόικα εσωτερικού διακωμωδεί το παράλληλο σύστημα πληρωμών και τις υποσχετικές (IOU), τις πληρωμές με «κουπόνια» ή «χαρτάκια χωρίς αντίκρισμα», όπως λένε, είτε δηλώνουν άγνοια του τι συμβαίνει εδώ και χρόνια στην Ελλάδα είτε δηλώνουν ότι το να δίνονται δισεκατομμύρια υποσχετικών (IOU) σε τραπεζίτες και προμηθευτές είναι «μια χαρά ιδέα», αλλά το να χρησιμοποιούνται για τη στήριξη συνταξιούχων, μικρομεσαίων και φτωχών οικογενειών (σε περίοδο που η τρόικα πάει να τους πνίξει) είναι «φαιδρό», «ανόητο» και «εγκληματικό».

Το παράδειγμα της Καλιφόρνιας

Το 2009 η Πολιτεία της Καλιφόρνιας αδυνατούσε να καταβάλει τις οφειλές της σε δανειστές, προμηθευτές και πολίτες. Ετσι, εξέδωσε υποσχετικές (IOU) με τις οποίες κατέβαλε τις οφειλές εκείνες.

Με τη σειρά τους, οι πολίτες που έλαβαν τις υποσχετικές μπορούσαν να κάνουν τρία πράγματα με αυτές:

α) Να τις κρατήσουν, ώστε κάποια στιγμή να τις εξαργυρώσουν για μετρητά (όταν η Καλιφόρνια θα ξεπέρναγε την κρίση ρευστότητάς της).

β) Να τις μεταφέρουν σε άλλους πολίτες ή επιχειρήσεις ως πληρωμή.

γ) Να τις χρησιμοποιήσουν για να πληρώσουν μελλοντικούς τους φόρους προς την Πολιτεία της Καλιφόρνιας.

Το παράλληλο σύστημα πληρωμών της Καλιφόρνιας βοήθησε τα μέγιστα στη διαχείριση της κρίσης της Πολιτείας και κατάφερε να κρατήσει την Καλιφόρνια στη… ζώνη του δολαρίου όσο καιρό χρειαζόταν για να ορθοποδήσει δημοσιονομικά. (Αργότερα, οι υποσχετικές εκείνες εξαργυρώθηκαν με δολάρια.)

Τον ίδιο σκοπό είχε και το σύστημα παράλληλων πληρωμών που είχα σχεδιάσει για την Ελλάδα: να κρατήσει τη χώρα στην ευρωζώνη δίνοντας ανάσες ρευστότητας στον ιδιωτικό και δημόσιο τομέα, παρά την άρνηση ρευστότητας από την ΕΚΤ.

Οχι στο παράλληλο νόμισμα

Ποια η διαφορά παράλληλου συστήματος πληρωμών από παράλληλο νόμισμα; «Η μέρα με τη νύχτα», είναι η απάντηση.

Οποιος θέλει έξοδο από το κοινό νόμισμα εισάγει παράλληλο νόμισμα. Οποιος πασχίζει για μεγαλύτερους βαθμούς ελευθερίας εντός του κοινού νομίσματος, όπως η Καλιφόρνια το 2009 (κι εγώ το 2015), εισάγει παράλληλο σύστημα πληρωμών.¹

Δεν είναι τυχαίο ότι η τρόικα εσωτερικού, αποφασισμένη να με παρουσιάσει ως «συνωμότη της δραχμής», αναφέρεται στο σχέδιό μου συστηματικά ως παράλληλο νόμισμα και ποτέ ως εκείνο που ήταν, δηλαδή ως σχέδιο για παράλληλο σύστημα πληρωμών.

Αυτά όμως έχει η μαύρη προπαγάνδα υπό το βάρος της οποίας ζούμε από τότε που η Ελλάδα μετετράπη σε χρεοδουλοπαροικία.

Πώς θα λειτουργούσε

Εστω ληξιπρόθεσμη οφειλή του Δημοσίου προς την Εταιρεία Α΄ ύψους €200.000 η οποία χρωστά €50.000 στην Εταιρεία Β΄ και μισθό ύψους €2.000 στον Υπάλληλο Κώστα.

Παράλληλα, η Εταιρεία Β΄ χρωστά πάνω από €48.000 στην Εφορία και €2.000 στην Υπάλληλο Αννα η οποία, με τη σειρά της, χρωστά €800 στον φίλο της τον Γιώργο που, και αυτός, έχει να πληρώσει φόρους άνω των €800 στο κράτος.

Αν κάθε ΑΦΜ αποκτήσει κι έναν χρεωστικό λογαριασμό και αποδοθεί στον φορολογούμενο ένα PIN με το οποίο θα μπορεί να μεταφέρει όποιο ποσό θέλει σε όποιον άλλον ΑΦΜ θέλει, προκύπτει η εξής δυνατότητα:

Το Δημόσιο εγγράφει πίστωση €200.000 (απλά δακτυλογραφώντας το νούμερο αυτό) στον ΑΦΜ της Εταιρείας Α΄.

Η Α΄ τώρα μπορεί να χρησιμοποιήσει το PIN της για να μεταφέρει €50.000 στον ΑΦΜ της Εταιρείας Β΄ και €2.000 στον ΑΦΜ του Κώστα.

Περαιτέρω, η Εταιρεία Β΄ μεταφέρει €48.000 πίσω στην Εφορία και €2.000 στην Αννα, η οποία με τη σειρά της χρησιμοποιεί το PIN της για να μεταφέρει €800 στον φίλο της τον Γιώργο, ο οποίος με τη σειρά του κι αυτός αποπληρώνει κάποιους από τους φόρους που χρωστά!

Εστω, τώρα, ότι η ΕΚΤ και η τρόικα κλείνουν τις τράπεζες. Πολύ εύκολα, το σύστημα αυτό, ιδίως με τη δυνατότητα οι μεταφορές αυτές να γίνονται μέσω εφαρμογών κινητών τηλεφώνων ή και πλαστικών καρτών, βοηθά να διευκολύνει τις συναλλαγές και να κρατήσει την αγορά ζωντανή υπό συνθήκες έκτακτης ανάγκης.

Π.χ. συντάξεις και μισθοί θα μπορούσαν, μερικώς, να κατατίθενται στους λογαριασμούς του TAXISnet, από όπου οι ιδιώτες θα μπορούσαν να πληρώνουν αλλήλους.

Στον βαθμό που όλοι, και τα σουπερμάρκετ, έχουν να πληρώνουν φόρους, όλοι θα δέχονταν (ιδίως σε περίοδο χαμηλής ρευστότητας μετρητών) αυτές τις πληρωμές.

Ενα τέτοιο σύστημα θα ήταν καλό και πρέπον να το έχει κάθε χώρα της ευρωζώνης ανεξάρτητα από την κρίση και τις συγκρούσεις με την τρόικα.

Για την Ελλάδα θα ήταν, και είναι, μοναδικό εργαλείο άμυνας για να μείνουμε στην ευρωζώνη βιώσιμα.

Μεγάλη μου τιμή…

Η τρόικα εσωτερικού έχει ένα δίκιο: Ο μόνος τρόπος να τιμηθεί εκείνο το μεγαλειώδες ΟΧΙ της 5ης Ιουλίου 2017 ήταν το παράλληλο σύστημα πληρωμών που σχεδίαζα με σκοπό να εξαντληθούν οι ευκαιρίες η χώρα να παραμείνει βιώσιμα, χωρίς να ερημοποιείται, εντός του ευρώ.

Εχετε προσέξει, αγαπητοί αναγνώστες, ότι τόσο στην περσινή επέτειο του δημοψηφίσματος όσο και φέτος η τρόικα εσωτερικού και τα «μέσα» της επέλεξαν τη συγκεκριμένη μέρα για να μου επιτεθούν, χρησιμοποιώντας «αποκαλύψεις» σημαντικών συνεργατών και φίλων μου (του Τζέιμς Γκάλμπρεϊθ πέρσι και του Γκλεν Κιμ φέτος) που, δήθεν, φέρνουν στο φως τα «εγκληματικά» και «ανόητα» σχέδιά μου;

Ο λόγος είναι απλός, και ιδιαίτερα τιμητικός για το πρόσωπό μου, κάτι που φαίνεται να μην καταλαβαίνουν: Το πρωτοποριακό παράλληλο σύστημα πληρωμών (σύμφωνα και με διεθνείς αναλυτές, π.χ. ο Wolfgang Munchau των Financial Times) που σχεδιάσαμε και εξελίξαμε με την ομάδα μου τους εξαγριώνει επειδή αποκαλύπτει τη δική τους αλόγιστη συνθηκολόγηση στους εκβιασμούς της τρόικας.

Οπως συμβαίνει συχνά στη χώρα μας, εκείνοι που την παρέδωσαν στους βαρβάρους στρέφονται μανιωδώς σε όσους δεν παρέδωσαν τα όπλα.

Κλείνω με μια πρόταση προς ωρυόμενους μνημονιακούς: Σας έχω προκαλέσει να με σύρετε σε Ειδικό Δικαστήριο. Κρύβεστε πίσω από το γεγονός ότι αρνείται η κυβέρνηση.

Σας προτείνω λοιπόν κάτι άλλο: Καλέστε με στα κομματικά γραφεία σας να με «εξετάσετε» εκεί.

Οχι τίποτα άλλο, μπορεί να κατανοήσετε έτσι τη διαφορά παράλληλου νομίσματος και παράλληλου συστήματος πληρωμών. Κάτι θα είναι και αυτό!

¹ yanisvaroufakis.eu

ΔΙΑΒΑΣΤΕ ΕΠΙΣΗΣ:

«Ρίχνουν νερό στο μύλο του Σόιμπλε»

Το ανακοινωθέν του Eurogroup μεταφρασμένο σε απλά ελληνικά (β’ μέρος)

Το ανακοινωθέν του Eurogroup της 15ης Ιουνίου μεταφρασμένο σε απλά ελληνικά

July 8, 2017

Bifo: “I am no longer a European given Europe’s daily crimes” & “thus I resign from DiEM25”. And my response

A few days ago, I received a letter from Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi that works like a punch-in-the-stomach type of wake up call addressed to all Europeans. To crown its tough message, Bifo concludes that his conscience cannot fathom being a European any longer, given Europe’s daily crimes against logic and humanity. Thus, Bifo concludes, he is compelled also to resign from DiEM25’s Advisory Panel. You can read his letter below along with, immediately following it, my reply and my reasons why we, at DiEM25, refuse to accept his resignation.

LETTER FROM FRANCO ‘BIFO’ BERARDI TO YANIS VAROUFAKIS & DiEM25

Dear Yanis, dear friends and comrades of the Democracy in Europe Movement 25,

After the shameful decisions of the Paris meeting of Minniti Collomb de Maziere it’s time to understand that there is something flawed in our project of re-establishing democracy in Europe: this possibility does not exist.

Democratic Europe is an oxymoron, as Europe is the heart of financial dictatorship in the world. Peaceful Europe is an oxymoron, as Europe is the core of war, racism and aggressiveness. We have trusted that Europe could overcome its history of violence, but now it’s time to acknowledge the truth:

Europe is nothing but nationalism, colonialism, capitalism and fascism.

During the Second World War not many protested against deportation, segregation, torture and extermination of Jews, Roma, communist militants and homosexuals. People had no information about the extermination.

Now we are daily acquainted about what is happening all around the Mediterranean basin, we know how deadly is the effect of the European neglect and of the refusal to take responsibility for the migration wave that is a direct result of the wars provoked by two centuries of colonialism.

The Archipelago of Infamy is spreading all around the Mediterranean Sea.

Europeans are building concentration camps on their own territory, and they pay their Gauleiter of Turkey, Libya, Egypt and Israeli to do the dirty job on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, where salted water has replaced ZyklonB.

To stop the migratory Euro-Nazism is going to build enormous extermination camps. The non-governmental organisations guilty of rescuing people from the sea will be contained, downsized, criminalised, repressed.

The externalisation of the European borders means extermination.

Extermination is the word that defines the historical mission of Europe.

Nazism is the only political form that corresponds to the soul of the European people.

In the last twenty-five years (since when, in February 1991, a ship loaded with 26.000 Albanians entered the port of Brindisi) we have known that the great migration had began. Two paths were possible at that point.

Opening its borders, starting a global distribution of resources, investing its wealth in a long lasting process of reception and integration of young people coming massively from the sea. This was the first path.

The second was to reject, to dissuade, to make almost impossible the easy journey from Northern Africa to the coasts of Spain Italy and Greece.

Europeans have chosen the second way, and they are daily drowning uncountable children and women and men.

Auschwitz on the beach.

With the exception of a minority of doctors, voluntary workers, activists and fishers, who now are accused of being the abetters of illegal migrants, the majority of the European population are refusing to deal with their own historical responsibility.

Therefore, I declare that I’m not European anymore. And I declare that I have never been European.

We have naively expected that an alliance of British murderers, French killers, Italian stranglers, he German slaughterers and Spanish slayers could give birth to a democratic peaceful friendly union. This pretence is over, and I’m sick of it.

Five centuries of colonialism, capitalism and nationalism have turned Europeans into the enemy of the human kind. May they be cursed forever! May Europeans be swept away by the storm they have generated, by the weapons they are building, by the fire they have ignited, by the hatred they have cultivated!

Because of the aforementioned reasons I must renounce the honour of being part of the Advisory Panel of DIEM25.

YANIS VAROUFAKIS’ REPLY

Dear Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, dear friend, dear comrade,

Hannah Arendt once said that as long as one German died at Auschwitz because of her or his opposition to Nazism, the Germans are not responsible collectively for Nazism.

Your letter to us, renouncing the horrors perpetrated in Europe’s name and resigning from our Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25) in protest, offers Europeans the same kind of possibility of redemption that Arendt’s ‘single-German-dying-in-Auschwitz’ offered the people of Germany.

You wrote a splendid and timely “J’ accuse” letter to Europeans as a true, unreconstructed, fed-up, European. And in so doing you offered Europe a small, tiny but important chance to save its soul.

It is very likely, as you fear, that Europe will throw that chance away; that Europeans will fail to exploit the minuscule chance that you offered. But it does not matter.

What matters is, first, that you, an authentic European, are putting Europe on the dock while, at once, offering it a precious chance of redemption. Only a true European radical, democrat and humanist could do that.

Secondly, it matters that there are many others like you. And that DiEM25, on whose Advisory Panel you have served, and from which you are now resigning in a bid to shake up our collective and individual consciences, is full of Europeans like you.

Europeans who, like you, are mad as hell with our Europe, as it is and as it acts.

Europeans who, nevertheless, realise that to shed their ‘European’ label in disgust at what Europe is doing to its citizens and to the citizens of the rest of the world requires also declaring that they are no longer Italian, French, British, Greek, Italian… since it is the nation-states of Europe that perpetrate, in the first instance, the scandalous policies that you so powerfully, and rightly, denounce.

Europeans who, mad as we are at Europe’s crimes, understand that renouncing Europe but not Italy, France, Greece, Germany, Britain etc. only plays into the hands of those propagating the fantasy of returning to the bosom of our benevolent nation-states; a fantasy that I know you abhor and one that DiEM25 is railing against.

Europeans who, enraged by what is being perpetrated in their name, are determined to demonstrate that the only way of being good citizens of the world is to be IN and AGAINST this

This is the reason we, at DiEM25, are proud of you and your “J’ accuse” letter of resignation from our Advisory Panel.

And it is the reason we do not accept it!

July 7, 2017

A New Deal for the 21st Century – op-ed in the New York Times 6th July 2017

ATHENS — The recent elections in France and Britain have confirmed the political establishment’s simultaneous vulnerability and vigor in the face of a nationalist insurgency. This contradiction is the motif of the moment — personified by the new French president, Emmanuel Macron, whose résumé made him a darling of the elites but who rode a wave of anti-establishment enthusiasm to power.

ATHENS — The recent elections in France and Britain have confirmed the political establishment’s simultaneous vulnerability and vigor in the face of a nationalist insurgency. This contradiction is the motif of the moment — personified by the new French president, Emmanuel Macron, whose résumé made him a darling of the elites but who rode a wave of anti-establishment enthusiasm to power.

A similar paradox is visible in Britain in the surprising electoral success of the Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, in depriving Theresa May’s Conservatives of an outright governing majority — not least because the resulting hung Parliament seemingly gives the establishment some hope of a change in approach from Mrs. May’s initial recalcitrant stance toward the European Union on the Brexit negotiations that have just begun.

Outsiders are having a field day almost everywhere in the West — not necessarily in a manner that weakens the insiders, but neither also in a way that helps consolidate the insiders’ position. The result is a situation in which the political establishment’s once unassailable authority has died, but before any credible replacement has been born. The cloud of uncertainty and volatility that envelops us today is the product of this gap.

For too long, the political establishment in the West saw no threat on the horizon to its political monopoly. Just as with asset markets, in which price stability begets instability by encouraging excessive risk-taking, so, too, in Western politics the insiders took absurd risks, convinced that outsiders were never a real threat.

One example of the establishment’s recklessness was releasing the financial sector from the restrictions that the New Deal and the postwar Bretton Woods agreement had imposed upon financiers to prevent them from repeating the damage seen with the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression. Another was building a system of world trade and credit that depended on the booming United States trade deficit to stabilize global aggregate demand. It is a measure of the sheer hubris of the Western establishment that it portrayed these steps as “riskless.”

When the ensuing financialization of Western economies led to the great financial crisis of 2007-8, leaders on both sides of the Atlantic showed no compunction about practicing welfare socialism for bankers. Meanwhile, more vulnerable citizens were abandoned to the mercy of unfettered markets, which saw them as too expensive to hire at a decent wage and too indebted to court otherwise.

When the insiders’ rescue schemes — including quantitative easing, the buying up of toxic assets, the eurozone’s bailouts and temporary nationalizations of banks — succeeded in refloating banks and asset prices, they also left whole regions in the United States, and whole countries on Europe’s periphery, stagnant. It was not rising inequality that provoked undying anger among these discarded people. It was the loss of dignity, of the dream of social mobility, as well as the experience of living in communities that were leveled down, so that a majority of people were increasingly equal but equally miserable.

As more and more voters became mad as hell, governing parties lost elections between 2008 and 2012 in the United States, Britain, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Greece and elsewhere. The problem was that the incoming administrations were as much part of the establishment as the outgoing ones. And so they made bipartisan the very approach that had caused the wave of anger that carried them into office.

That approach was doomed, not least because economic forces were already working against the new governments. After the 2008 crash, the monetary easing by central bank institutions like the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England fended off a global repeat of the Great Depression. China’s unleashing of a huge credit-fueled construction boom, which saw investment rise to 48 percent of national income in 2010, from 42 percent in 2007, and total credit climb to 220 percent of national income by 2014, from 130 percent in 2007, also softened the financial market failures of the West.

Unsurprisingly, though, these central bank money-creation schemes and the Chinese credit bubble proved unable to prevent severe regional depressions, which struck from Detroit to Athens. Nor could they prevent sharp global deflation from 2012 to 2015.

By 2014, voters had begun to give up on the new administrations they had voted for after 2008 in the false hope that the establishment’s loyal opposition could provide new solutions. Thus, 2015 saw the first challenges to the insiders’ authority start to surface.

In Greece — a small country, yet one that has proved to be a bellwether thanks to its gargantuan and systemically significant debt — protests against the debt bondage imposed on the population evolved into a progressive, internationalist coalition led by the Syriza party that came from nowhere to win government. In Spain, a similar movement, Podemos, began to rise in the polls, threatening to do the same.

In Britain, a left-wing internationalist tendency that had been marginal in the Labour Party coalesced around the leadership campaign of Jeremy Corbyn — and surprised itself by winning. Soon after, the independent socialist senator from Vermont, Bernie Sanders, carried the same spirit into the Democratic Party primaries.

Everywhere, the political establishment treated these left-of-center, progressive internationalists with a mixture of contempt, ridicule, character assassination and brute force — the worst case, of course, being the treatment of the Greek government in which I served during the first half of 2015. Historians may mark that year as when the establishment turned truly illiberal.

By 2016, the establishment’s arrogance met its first, frightful nemesis: Brexit. The shock waves from the insiders’ unheralded defeat in that referendum rippled across the West. They brought new energy to Donald Trump’s outsider campaign in the American presidential election, and they invigorated Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France.

From the West to the East, a new Nationalist International — an allied front of right-wing chauvinist parties and movements — arose.

The clash between the Nationalist International and the establishment was both real and illusory. The venom between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump was genuine, as was the loathing in Britain between the Remain camp and the Leavers. But these combatants are accomplices, as much as foes, creating a feedback loop of mutual reinforcement that defines them and mobilizes their supporters.

The trick is to get outside the closed system of that loop. The progressive internationalism of Mr. Corbyn’s Labour Party, Mr. Sanders’s supporters and the Greek anti-austerity movement came to offer an alternative to the deceptive binaries of establishment insiders and nationalist outsiders. An interesting dynamic ensued: As the insiders defeated or sidelined the progressive internationalist outsiders, it was the nationalist outsiders who benefited. But once Mr. Trump, the Brexiteers and Ms. Le Pen were strengthened, a remarkable new alignment took place, with a series of unstable mergers between outsider forces and the establishment.

In Britain, we saw the Conservative Party, a standard-bearer of the establishment, adopt the pro-Brexit program of the tiny, extreme nationalist U.K. Independence Party. In the United States, the outsider in chief, Mr. Trump, formed an administration made up of Wall Street executives, oil company oligarchs and Washington lobbyists. As for France, the anti-establishment new president, Mr. Macron, is about to embark on an austerity agenda straight out of the insiders’ manual. This will, most probably, end by fueling the current of isolationist nationalism in France.

Where does this prey-predator game between the globalist establishment and the isolationist blood-and-soil nationalists leave us?

The recent elections in Britain and France confirm that both strands are alive and kicking, reinforcing each other, as they tussle, to the detriment of a vast majority of their populations. Both Mrs. May’s and the European Union’s negotiating teams in Brussels are investing their efforts in an inevitable impasse, which each believes will bolster their political authority, even though it will disadvantage the populations on both sides of the English Channel that must live with the consequences.