Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 119

October 5, 2017

October 4, 2017

ΑΝΙΚΗΤΟΙ ΗΤΤΗΜΕΝΟΙ, Δευτέρα 9 Οκτωβρίου, 7μμ – βιβλιοπαρουσίαση στην Τεχνόπολη (Γκάζι) με τους: Νάντια Βαλαβάνη, Βασίλη Βασιλικό & Νίκο Θεοχαράκη

Η ελληνική έκδοση του βιβλίου του Γιάνη Βαρουφάκη για την Ελληνική Άνοιξη 2015, που έγινε best seller στην Βρετανία υπό τον τίτλο ADULTS IN THE ROOM, παρουσιάζεται την Δευτέρα 9/10 στις 7μμ στην Τεχνόπολη Δήμου Αθηναίων (Αεροφυλάκιο 1 – Αμφιθέατρο) υπό τον τίτλο ΑΝΙΚΗΤΟΙ ΗΤΤΗΜΕΝΟΙ: Για μια ελληνική άνοιξη μετά από ατελειώτους μνημονιακούς χειμώνες.

Το βιβλίο παρουσιάζουν οι: Νάντια Βαλαβάνη, Βασίλης Βασιλικός και Νίκος Θεοχαράκης. Συντονίζει ο Κωνσταντίνος Πούλης (ThePressProject). Κείμενα θα διαβάσει η Μαρία Καρακίτσου

September 29, 2017

Article on DiEM25 in the Boston Globe – by Thanassis Cambanis, 29th September 2017

WHEN THE PUBLIC is disillusioned with an entire political culture, it’s not a problem that technocrats alone can fix. But an unlikely band of Greek reformers may have an answer for an unsettled Europe — and the entire Western world.

Over the last seven decades, Western Europe, with support from the United States, built a liberal order around lofty goals — peace; stable, elected governments; open economies; and shared solutions to regional and global needs. Today, though, Europe’s institutions inspire as much frustration as admiration, with many questioning the entire conceit of a united continent. In the European Union today, citizens heap disdain on the experts in Brussels who have produced reams of regulations on everything from mine safety to banking hours to what kind of labels cheesemakers can use. The sense of malaise ballooned after the 2008 financial crisis exposed the cracks in the union’s foundation, and still more after a wave of new migrants arrived from the south and east beginning in 2015.

While the Brexit vote and the emergence of Donald Trump have prompted some in Europe to rally to the EU’s defense, a homegrown extreme right has gained influence by opposing immigrants and the European Union alike.

Over the years, Europe’s solution to many woes has been to elevate technocrats to ever-greater positions of power, enabling them to go around populist politicians. Yet according to a newly energized wave of reformers, Europe’s penchant for experts has been its undoing, breeding a culture of contempt for democracy.

“We have a Europe that has lost its democracy and legitimacy and soul,” said Yanis Varoufakis, the former finance minister of Greece and founder of the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025, which is trying to invent a new kind of transnational politics that will revive Europe. “We want a European democratic union. Otherwise everything we care about will go to the dogs.”

His movement has attracted 100,000 members and is promoting what it calls a “European New Deal,” modeled after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

The activists in Varoufakis’s movement, also known as Diem 25, argue that if Europe is to survive and thrive, it needs to preserve its social-welfare values but also its capitalist dynamism. Their version of the New Deal would stop austerity policies, beef up anti-poverty programs, and invest in jobs for the unemployed.

Yet Varoufakis’s movement also thinks Europe needs an injection of American-style participatory democracy. Brussels operates by bureaucratic consensus. Diem 25 favors a pan-European government vested with more tangible, but also politically accountable, power.

Supporters of Diem 25 see their struggle as part and parcel of a global response to a crisis of inequality and illiberalism that connects them with Bernie Sanders in the United States and the Podemos party in Spain, and with more hardline constituencies like the Occupy movement and anarchist movements.

Varoufakis and his supporters aren’t revolutionaries. They want to channel a neglected group: the fed-up, left-behind 99-percenters who are angry at bankers, fat cats, and Davos grandees — but who also prefer to fix the system rather than blow it up. The Diem 25 movement wants to harness the energy and tactics of the radical left — but in service of a reform agenda that seeks to repair capitalism rather than replace it.

ALREADY, DIEM 25’S rhetoric is reflected in mainstream policy — in the grudging support for EU reform from German Chancellor Angela Merkel and in a more rousing call for reform this past week from France’s young new president, Emmanuel Macron. “The Europe we know is too weak, too slow, too inefficient, but only Europe gives us the capacity to act on the world stage in the face of the big, contemporary challenges,” Macron said in a speech that endorsed many of the Varoufakis bloc’s proposals

It’s striking that the vanguard of European reform has its roots in the tribulations of Greece. One of the EU’s smallest and weakest members, Greece knows how the union operates at its best and at its worst. Europe integrated Greece in 1981 to rekindle democracy there after a disastrous military dictatorship that fell in 1974. The ancient birthplace of democracy embodied the EU’s role of spreading not only wealth but freedom.

But when the financial crisis hit in 2008, it was every nation for itself. Rich countries in the euro zone, like Germany, had very different needs than poorer peers like Portugal, Spain, and Greece. A cabal of mostly unelected finance officials from rich Europe orchestrated a bailout for poor Europe, imposing draconian austerity and triggering a human calamity. Greece suffered the most, but other poor European countries also languished in depression. Meanwhile, immigrants flooded into a fractured Europe unable to coordinate its immigration policy or control its borders. Eventually a deal was reached that amounted to Europe paying Turkey to bottle up refugees there.

In tatters was any pretense of democratic international consensus. Extremist right-wing groups surged in popularity, while legacy national political parties and the bureaucrats in Brussels seemed out of ideas and popular appeal.

But just in the last year, a surprisingly vital third-way reform effort has surged. Varoufakis, an iconoclastic Greek economist, embodies this new fusion of radical and center. The 56-year-old career academic grew up as a self-identified radical and leftist. As a teenager he sided with socialists against the remnants of Greece’s right-wing junta. In the 1980s, he joined workers on the picket lines in England protesting against Margaret Thatcher’s austerity. By the 2000s, however, Varoufakis had adopted a strikingly centrist ideology.

Even before the 2008 financial crisis, he had begun writing extensively about the problems of runaway finance capital and of central banks more powerful than elected politicians. Yes, communism had failed spectacularly, as the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991 made clear. But triumphalist capitalism suffered its own catastrophe in 2008, Varoufakis believes, opening the path for a renewed social democracy and a heavily regulated version of capitalism.

Fresh off the publication of two books about the perils of global finance and his vision for a policy that preserved capitalism but shattered the hegemony of the elitist 1 percent, Varoufakis found himself suddenly swept from academia into politics in January 2015.

Greece’s new socialist party, Syriza, won power after the country’s established parties all imploded, and drafted Varoufakis to join the government and run its do-or-die negotiations with the euro zone in 2015. For six months, Varoufakis confronted the most powerful finance ministers and central bankers in the world, and made his case to everyone who would listen. Austerity punishes the poor for the incompetence of financial elites, Varoufakis proclaimed.

Europe’s bankers crushed Greece’s attempt to rebel against austerity. Varoufakis left government perversely energized by his failure. He published a tell-all about the secret negotiations to bring Greece to its knees called “Adults in the Room,” with zingers from conversations he had secretly taped on his phone during meetings he’d had with masters of the global finance universe.

The 500-page memoir about the inner workings of currency union and bailouts made an unlikely best-seller. But like Thomas Piketty’s plodding volume “Capital,” it struck a chord with its explanations of the roots of inequality, and alienation — and with its concrete suggestions to improve matters with a hefty dose of electoral democracy and redistribution of wealth and power.

THE DEMOCRACY in Europe Movement 2025 launched in February 2016, with chapters all across the EU. Its acronym is meant to evoke “carpe diem,” the Latin exhortation to seize the day. The year 2025 is the group’s deadline to bring about a new European constitution.

Whenever possible, the movement’s organizers want to persuade existing political parties to adopt the Diem 25 platform, like Poland’s Razem and Denmark’s The Alternative. But Diem 25 will also run for office at the European level; it already is planning a campaign for the 2019 European parliamentary elections.

The New Deal adopted by Diem 25 aims to revive and democratize Europe’s utopian ideals first through quick fixes that don’t require complex international treaties. These include investment in jobs for the unemployed, economic coordination with countries outside the euro zone, and a new digital payments system.

The next steps proposed by Diem 25 are more ambitious. A tax on finance would fund a European budget. The European Commission, which wields enormous executive power, would become directly elected. And the European Parliament, which today lacks even the power to initiate legislation, would become a real legislative body. Existing political parties and new movements like Diem 25 would have to organize and form alliances across national boundaries, creating European-wide electoral politics to complement political life at the national level.

Under current conditions, few European voters would agree to surrender an iota of sovereignty to Brussels; the track record of the technocrats is too tainted. That’s why the first step is to stabilize Europe and deliver big economic improvements using existing institutions and power. Once that happens, Europe can convene a constitutional assembly to draft a new charter for the continent.

In today’s West, Varoufakis said, “authoritarianism and incompetence feed off each other.” With existing approaches discredited, he believes Europeans will be receptive to a federal, democratic blueprint to fix the continent — but it only can work if it wins legitimacy at the ballot box.

“We leftists and liberals whose illusions were incinerated — can get together to stop creeping neo-fascism,” Varoufakis said. “Even though we are radicals, we don’t want to see a disintegration of the EU because of all the great things it has brought — peace being the greatest of them.”

Although anti-Americanism has long been in vogue for much of the European left, there is a strong American flavor to the whole European project. Varoufakis unapologetically praises and borrows from what he thinks is most valuable in the American democratic tradition. It was American pressure, vision, defense, and money that created modern Europe in the first place.

THERE ARE countless hurdles to a reform agenda for Europe. Since the 1950s, efforts to democratize decision-making, or implement real shared sovereignty across national borders, have foundered because member governments, and sometimes their citizens, are loath to shift power to international bodies.

“This idea of the disconnect between elites and the population is widespread,” said Susi Dennison, a senior fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations who studies efforts to reform the EU.

Some proposals have gained mainstream momentum, she said, including the plan to create some new European parliament seats that are elected by continent-wide votes, and to make the European Commission and presidency more directly tied to elections.

But nationalist sentiment remains strong, as does resistance to the fundamental idea of the EU, she said. As Brexit showed, not that many voters care about the idea that the EU is an effective insurance policy against continental war — even if it’s true. Over time, Dennison said, she fears that even well-meaning reform efforts will appear to the public as nothing more than added layers of bureaucracy, and the European project will lose what little value it retains in the eyes of the public.

“I don’t think it will collapse tomorrow, but there’s a very real risk,” she said.

The slow-boil crises of the last decade have altered the landscape throughout the United States and Europe, with anti-immigrant right-wing groups an established part of the political power structure. For the latter half of the 20th century, Western electorates might have come to see war as a risk only for faraway, far less fortunate countries. But the tensions that have erupted since 2008 serve as a reminder that the West’s democratic peace isn’t a given. It arose from the aftershocks of apocalyptic world war, and took sustained effort to build. Without strong public commitment, it could crumble.

Thanassis Cambanis, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, is the author of “Once Upon a Revolution: An Egyptian Story.” He is an Ideas columnist and blogs at thanassiscambanis.com.

September 28, 2017

Schäuble leaves but Schäuble-ism lives on

Wolfgang Schäuble may heave left the finance ministry but his policy for turning the eurozone into an iron cage of austerity, that is the very antithesis of a democratic federation, lives on.

What is remarkable about Dr Schäuble’s tenure was how he invested heavily in maintaining the fragility of the monetary union, rather than eradicating it in order to render the eurozone macro-economically sustainable and resilient. Why did Dr Schäuble aim at maintaining the eurozone’s fragility? Why was he, in this context, ever so keen to maintain the threat of Grexit? The simple answer is: Because a state of permanent fragility was instrumental to his strategy for using the threat of expulsion from the euro (or even of Germany’s withdrawal from it) to discipline the deficit countries – chiefly France.

Deep in Dr Schäuble’ thinking there was the belief that, as a federation is infeasible, the euro is a glorified fixed exchange rate regime. And the only way of maintaining discipline within such a regime was to keep alive the threat of expulsion or exit. But to keep that threat alive, the eurozone could not be allowed to develop the instruments and institutions that would stop it from being fragile. Thus, the eurozone’s permanent fragility was, from Dr Schäuble’s perspective an end-in-itself, rather than a failure.

The Free Democratic Party’s ascension will see to it that Wolfgang Schäuble’s departure will not alter the policy of doing whatever it takes to prevent the eurozone ‘s evolution into a sustainable macroeconomy. The FDP’s sole promise to its voters was to prevent any of Emmanuel Macron’s plans, for some federation-lite, from being agreed to, and for pursuing Grexit. Even worse, whereas Wolfgang Schäuble understood that austerity plus new loans were catastrophic for countries like Greece (but insisted on them as part of his campaign to discipline France and Italy), his FDP successors at the finance ministry will probably be less ‘enlightened’ believing that the ‘tough medicine’ is fit for purpose.

And so the never ending crisis of Europe’s social economy, that feeds the xenophobic political monsters, continues.

Ο Σόιμπλε φεύγει ο Σοϊμπλισμός ενισχύεται

Ο Βόλφγκαγκ Σόιμπλε μπορεί να αποχώρησε από το Ομοσπονδιακό Υπουργείο Οικονομικών αλλά η καμπάνια του να χρησιμοποιήσει την κρίση του ευρώ ώστε να μετατρέψει την ευρωζώνη σε Σιδερένιο Κλουβί Λιτότητας (το ακριβώς αντίθετο μιας δημοκρατικής ομοσπονδίας) ζει και βασιλεύει.

Η άνοδος του FDP, του Κόμματος των Φιλελεύθερων Δημοκρατών, εξασφαλίζει πως η αποχώρηση του Δρ Σόιμπλε δεν θα ανατρέψει τις πολιτικές με τις οποίες εκείνος έκανε ό,τι ήταν δυνατόν ώστε η ευρωζώνη να μην μετεξελιχθεί σε βιώσιμη μακροοικονομία.

Ένας ήταν ο Μέγας Ηττημένος των πρόσφατων γερμανικών εκλογών: Ο Εμμανουέλ Μακρόν και, μαζί του, όσοι πίστεψαν πως το κατεστημένο (μέσω του Μακρόν) έχει την δυνατότητα να γεννήσει λύσεις που παραπέμπουν μεσοπροόθεσμα σε μια δημοκρατική ευρωπαϊκή ομοσπονδία. Οι αυταπάτες αυτές διαλύθηκαν τώρα που ο Βόλφγκαγκ Σόιμπλε παραδίδει την σκυτάλη του Ομοσπονδιακού Υπουργείου Οικονομικών σε ένα κόμμα Σοϊμπλικότερο από τον ίδιο και αποφασισμένο να προωθήσει το Grexit την ώρα που αρνείται στο Παρίσι την παραμικρή πρόταση προς ομοσπονδοποίηση η οποία υπερβαίνει κάποιες διακοσμητικές αλλαγές (π.χ. την μετονομασία του Προέδρου του Eurogroup σε υπουργό οικονομικών της ευρωζώνης ή στην μετατροπή του Ευρωπαϊκού Μηχανισμού Σταθερότητας σε Ευρωπαϊκό Νομισματικό Ταμείο).

Περιληπτικά, ο Βόλφγκαγκ Σόιμπλε πάσχισε όλα αυτά τα χρόνια για να παραμείνει η ευρωζώνη εύθραυστη, με την κρίση να σιγοβράζει χωρίς να επιλύεται. Ο λόγος που ήθελε διακαώς την μη λύση της κρίσης, και μια ευρωζώνη μονίμως εύθραυστη, ήταν ο εξής: Όσο η ευρωζώνη παραμένει εύθραυστη, και η κρίση σιγοβράζει, η απειλή της έξωσης από το ευρώ (όχι μόνο της Ελλάδας!) παραμένει ισχυρή και λειτουργεί ως μέθοδος πειθάρχισης των ελλειμματικών χωρών – ιδίως της Γαλλίας. Το FDP, το οποίο παίρνει την σκυτάλη από τον Δρ Σόιμπλε, διακρίνεται για την προσήλωσή του στην καμπάνια του απερχόμενου υπουργού οικονομικών της εύθραυστης, σε μόνιμη (ελεγχόμενη), κρίση ευρωζώνη. Έτσι, η μόνη ορθολογική προσδοκία για την νέα κυβέρνηση της κας Μέρκελ είναι η συνέχιση της κρίσης της ευρωζώνης, ως επιλογή του Βερολίνου (κι όχι αποτυχία) και, συνεπώς, η ενίσχυση των ξενοφοβικών πολιτικών τεράτων που αυτή γεννοβολά.

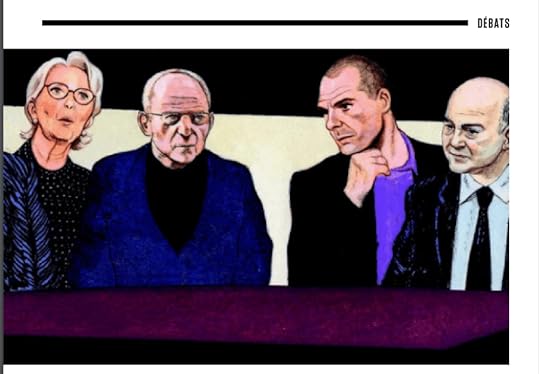

On negotiating with the EU & fiscal money – with Anatole Kaletsky & journalists from El Pais, Handelsblatt – Project Syndicate video

Yanis Varoufakis discusses how to negotiate with the EU and his proposal to introduce fiscal money with Anatole Kaletsky, Co-Chairman of Gavekal Draganomics, David Alandete, Managing Editor of El Pais, and Torsten Riecke, Handelsblatt’s international correspondent.

September 25, 2017

“Προαπαιτούμενα ελπίδας” – Ομιλία Γ. Βαρουφάκη στην Πάτρα 25 Σεπτεμβρίου 2017

DiEM25 Greece

Το DiEM25 και ο Γιάνης Βαρουφάκης βρέθηκαν στο θέατρο Royal στην Πάτρα που γέμισε με ανθρώπους κάθε ηλικίας που θέλησαν να ακούσουν από κοντά την πρόταση του κινήματος για την αντιμετώπιση της κρίσης στην Ελλάδα και την Ευρώπη.

Για περισσότερα διαβάστε εδώ: http://bit.ly/2hvSXSl

September 14, 2017

Adults in the Room: The Sordid Tale of Greece’s Battle Against Austerity and the Troika – by Dean Baker, Huffington Post

Yanis Varoufakis begins his account of his half year as Greece’s finance minister in the left populist Syriza government (Adults in the Room, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) with a description of a meeting with Larry Summers. According to Varoufakis, Summers explains that there are two types of politicians. There are those who are on the inside and play by the rules. They can just occasionally accomplish things by persuading others in the room to take their advice.

Then there is the other type of politician, those who don’t agree to the rules and will never get anywhere. Summers asks Varoufakis which type of politician he is.

As Varoufakis tells us he explained to Summers, he is the second type. He is committed to accomplishing something for his people, most immediately the people of Greece in the struggle to end mindless austerity, but ultimately the people of Europe and arguably the world, in an effort to fight against needlessly cruel economic policies. If this means breaking with the decorum of the elites, so be it.

There is no reason to question Varoufakis’ commitment. He left a comfortable life as an academic in Austin, Texas to take up what he certainly knew to be an incredibly difficult job as Greece’s finance minister in the middle of a financial crisis. The newly elected populist government was despised by most of the business and political establishment in Greece and across Europe. Only a person with a genuine commitment to the stated goals of the new government would take on this role. But reading his account, it is questionable whether the path he took was necessarily the best one for Greece and for Europe.

The Long Six Months

To give the basic story, at the start of 2015 Greece was being confronted by the joint power of the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB), and the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F), collectively known as the “Troika”, who were insisting that Greece impose further spending cuts and tax increases even though the country had already endured seven years of depression.

I am using “depression” in the interest of accuracy, not exaggeration. By 2015 Greece’s economy had contracted by more than 25 percent compared with its 2007 level. Employment was down by almost 22 percent from where it had been at its pre-crisis peak. By comparison, in the Great Depression the U.S. economy shrank by 28 percent from 1929 to 1933, but had exceeded its pre-crisis peak by 1936. Greece will be lucky if its economy gets back to its 2007 level of output by 2027.

The Troika had gotten the previous conservative government to agree to a wide range of tax increases and spending cuts that had both devastated the economy and left many of the country’s poorest people in desperate straits. They had agreed to large cutbacks in already meager pensions, as well as cuts to a variety of programs designed to serve the poor.

The ostensible purpose of these cuts was to have Greece build up a large budget surplus, which would allow it to repay prior loans from the Troika. The budget target demanded by the Troika was an annual surplus on the primary budget, which excludes interest payments, equal to 3.5 percent of GDP (a bit less than $700 billion in the U.S. economy in 2017). The Troika’s program also included a wide variety of other demands, including privatization of many public assets and measures designed to weaken the power of Greece’s workers.

While there was much for any progressive to object to in the Troika’s program for Greece, Varoufakis’ key point throughout the book is that the program clearly would not work if the point was to get the money back for Greece’s creditors. He argues that there was no way for Greece to run the large surpluses demanded by the Troika. This meant that the debt was likely to grow through time rather than shrink. He argued that the only honest route forward was a write-down of large amounts of the debt, admitting that this money was lost. After a write-down, which would free Greece of onerous interest payments, the country could get back on a course of stable growth.

The book is a tale of bureaucratic dysfunction and outright treachery. In the latter category we find the Socialist finance minister of France as well as the Social Democratic economy minister of Germany. Both are warm and supportive of Varoufakis in private meetings, but then turn around and condemn Greek profligacy when they speak in public. Any number of other figures accept the logic of Varoufakis’ argument in private, including top officials at the I.M.F., but then melt into submission in the presence of German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, Veroufakis’ main nemesis.

The account would be comical if the lives of real people were not at stake. We also get an inside look at the absurd bureaucratic structures that have been created by the European Union. Varoufakis repeatedly finds himself at meetings where no one has the power to do anything to help Greece in its efforts to seek debt relief. While much of this was obviously a deliberate effort at obstruction, the structures of the EU do make it difficult to get anything done and hold anyone accountable for what ultimately happens.

Varoufakis explains to us his negotiating strategy, and ostensibly the strategy of Syriza government to which he belonged. The goal was to accomplish debt relief while staying in the euro zone. He knew that the Troika would never grant debt relief without some threat. (Why would they give to a populist government that had harshly criticized them a deal that they would not give to a subservient right-wing government?) Varoufakis’ threat was to leave the euro zone and establish a new currency.

Throughout the book, he is very clear that the goal was always staying in the euro. For an outsider following the negotiations closely at the time, this certainly seemed to be the case. However, he argued that the exit option was essential in order to force concessions from the Troika. His ranking of outcomes was always first, stay in the euro with debt relief, second leave the euro and unilaterally default, third stay in the euro and endure further austerity.

To jump to the finish, Greece ended up staying in the euro and enduring further austerity. In other words, it ended up with the worst option. In Varoufakis’ account this was due to the unwillingness of his government to be prepared to carry through on the threat to leave the euro. Without this threat, the country had no bargaining power and therefore no option other than further austerity.

The Exit Option: Was It a Real Threat?

To evaluate Varoufakis’ assessment it is worth asking about the motives of the Troika. One that he repeats several times is that debt relief would imply that the first two bailouts Greece had received had been a hoax. In effect these bailouts were about rescuing banks (mostly German and French) from their bad loans, not about helping Greece get back on a stable growth path.

Varoufakis is undoubtedly correct about the purpose of the bailouts, but governments have gotten very good at hiding the reasons for their actions from the public. Part of the Obama administration’s stimulus package was a first-time homebuyer’s tax credit. The credit almost immediately stopped the plunge in house prices as people rushed to get the $8,000 the government put on the table (myself included). However since the bubble had not yet fully deflated, house prices began plunging again in the summer of 2010 after the credit ended.

The tax credit had the effect of allowing the payoff of hundreds of billions in mortgages that likely would have gone bad if the house price decline continued. Many of these mortgages were in the hands of banks or privately issued mortgage backed securities. When the homes were sold the new mortgages were almost exclusively government backed, since the private securitization market was destroyed by the financial crisis. This little trick was especially pernicious since the temporary reversal in pricing was most pronounced at the bottom end of the market. In effect, the credit was a great way to get hundreds of thousands of moderate income households to buy into the bubble market before it fully deflated.

Virtually no one paid attention to this massive transfer of high risk debt from the private sector to the government through the tax credit and to this day even most careful followers of the crisis haven’t noticed this effect. It not plausible the reason for refusing a write-down of Greek debt was just to hide bailout loans. When it comes to public deception, Varoufakis was dealing masters of the art. These people certainly could have found some clever way of giving a backdoor debt write-down which would not require any acknowledgement of the purpose of the previous bailouts.

A second possible motive was to force labor market reforms on Greece and other countries in the euro zone. This was clearly a goal of the bailout packages, but it is not clear that it precluded debt forgiveness. Varoufakis even says that he offered to work out an acceptable package of labor market reforms with Schäuble, but he didn’t express any interest in pursuing the issue.

Perhaps Schäuble didn’t think he could come to any agreement with Varoufakis on the issue, but if labor market reform really topped his agenda, it’s hard to believe that Schäuble would not at least pursue a preliminary discussion on the topic. In this respect, it is worth noting that Emmanuel Macron, Varoufakis’s great French ally on the write-down issue, is putting labor reform front and center in his agenda as president of France.

The third reason, which Varoufakis hints at several times, is that if Germany agreed to a write-down for Greece, it would be pressed to do the same for Italy, Spain, and other heavily indebted countries. While Greece is small change in the context of the EU budget, Italy and Spain certainly are not, especially if both are seeking write-downs at the same time. Certainly Schäuble understood that he had to give the respectable politicians running other heavily indebted countries at least as good a deal as he gave to the scruffy radicals running Greece.

This one seems the most compelling. If we assume the governments of other euro zone countries are run by competent people, then there is no way that Schäuble could give any substantial debt reduction to Greece and keep it secret from them. If he allowed Greece to write down a substantial portion of its debt he would have to do the same with other countries. This would be real money. For this reason it is completely understandable that Schäuble would not want to give Greece a debt write-down; he would have to soon do the same with other troubled debtors.

Of course we have to take a step back and ask what would be the problem if the EU did make the money available to allow large-scale debt write-downs for all the heavily indebted countries. The ECB did have the money for even a major dose of debt forgiveness since after all it prints the stuff.

Whatever the economic reality might be, we shouldn’t rule out the possibility that these people really don’t understand the basic economics. They may really believe that the euro zone was genuinely constrained in its ability to finance debt forgiveness. If this is the case, Schäuble’s refusal to seriously discuss terms with Varoufakis makes perfect sense.

There is another aspect to the issue that is worth considering. Varoufakis’s trump card was the threat to leave the euro. He is undermined in this threat by his prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, who backs away from the threat when push comes to shove.

But suppose that Germany, and in particular Schäuble, didn’t care if Greece left the euro. Back in 2011, at the height of the crisis, Greece’s exit could well have led to the collapse of the euro. But by 2015 the markets had stabilized. ECB bank president Mario Draghi’s commitment to “do whatever it takes” to support the bonds of the countries in the euro zone had done its job. The interest rates on the non-Greece crisis countries had come down to very manageable levels. They likely felt that the euro could withstand a Grexit at that point, even if they might have preferred a compliant Greek government to accept their package.

If this is the case, then the threat to leave the euro was of little value. The real choice was accepting the bailout conditions and staying within the euro or taking the leap and leaving. Tsipras was elected on the agenda of ending the austerity and staying within the euro. If this was impossible, then the question was which of his commitments to the public he should break. He may have chosen the wrong one, but he really had no good choices from day one.

In this respect it is worth noting an issue that Veroufakis mentions in passing but doesn’t fully pursue in the book. As his meeting with various ministers and officials were proving fruitless, Veroufakis had an opportunity for a face to face meeting with Schäuble. At this meeting Schäuble explained that Greece really didn’t belong in the euro. He proposed an orderly departure, which he said could be a temporary time-out. This departure would come with a grace period on debt obligations and assistance in re-establishing its own currency.

It’s not clear if Schäuble was fully serious in putting this proposal on the table or that he had the backing of Angela Merkel to pursue it. However if debt forgiveness within the euro was not a possibility, this sort of orderly exit certainly would have been the best possible option. If there was any way Greece could have pushed forward along the lines Schäuble suggested to Varoufakis, this should have been his top priority. However his book suggests that he treated the proposal as a passing curiosity, not something that should distract him from his quest for a debt write-down within the euro.

There is one point that should jump out at any reader of this book. The title, “adults in the room” is a quote from I.M.F. managing director Christine Lagarde. It refers to the people with whom Varoufakis spent his six months negotiating. By contrast, he and his scruffy populist colleagues had questionable status in this world.

On this topic it is worth checking the scorecard. These are the people who controlled economic and financial policy as the world saw the growth of asset bubbles of unprecedented size. The collapse of these bubbles, coupled with the weak response of fiscal policy, and to a lesser extent monetary policy, cost the world tens of trillions of dollars of lost output. This translated into tens of millions of people needlessly going unemployed, millions losing their homes, and others going without access to health care or being denied the opportunity to get an education. (FWIW, the I.M.F. now projects that Greece’s primary budget surplus in the years ahead will be almost exactly the 1.5 percent of GDP offered by Varoufakis.)

The events of the last decade were a true disaster from which we have still not fully recovered. In a just world, the people who were responsible for this momentous failure would have been pushed out of their jobs. Instead, with few exceptions, the same group of people who led us into disaster are still the ones determining economic policy. These people may have considerable power, but that doesn’t make them adults.

Note: The description of the exchange with Summers has been corrected from an earlier version, which said we don’t know what he said to Summers.

For the Huffington Post site where this review was published, click here.

September 12, 2017

Germany needs a frank debate, not this tepid election campaign – Op-ed in Deutsche Welle

The Greek people are paying dearly for having been lulled into a false sense of security, writes former Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis. Germans, he says, are laboring under the same illusion today.

Complacency is a country’s worst enemy. My compatriots were, once upon a time, lulled into a false sense of having “made it.” I very much fear that a majority of Germans feel their land is “doing fine.”

That the federal election campaign is proving such a tepid affair is a reflection of the false sense of security generated by Germany’s three surpluses: Companies save, households save, the Frankfurt banks are awash with monies sent to them from other European countries, even the federal government budget is in surplus. But these surpluses are the sign of weakness, not strength. They are the harbingers of significant current and future hardship for most Germans now and in the future.

Think about it for a minute: A current account surplus of almost 10% of national income means that the nation must take its savings and send it abroad to be invested in deficit countries. Is this a prudent thing to do, especially when German capital abroad is creating bubbles bound to burst (like they did in Greece and Spain)?

Also, how smart is it to rely on the money influx into the Frankfurt banks to cover up their insolvencies, especially when this tsunami of foreign monies is flooding Germany because their Italian or French owners are losing hope in their own countries’ economy? Finally, how rational is it for the federal Finance Ministry to celebrate a budget surplus that is due to the negative interest rates which (a) are crushing German pension funds and (b) causing the famed Swabian housewife to lose faith in the German political establishment?

Germany needs a frank debate among its citizens on how to deal with the threat that its surpluses are posing to German society, just as much as Greece needed a similar debate, some time ago, on the threat posed by our deficits. After all, for every surplus there must a deficit somewhere else within a monetary union. To have the political establishment celebrate imbalances as signs of economic health, just because Germany is blessed with their surplus side, is to misrepresent to the German public a source of troubles as evidence of success.

Taking a look at history, Germany rose to envy-of-the-world status as a result of a social contract that offered its working-class strong protection (and seats on the boards of directors of large companies) in exchange for a flexible, rule-bound, liberal environment in which business could get on with it. But this was only possible while the United States were managing the macroeconomic environment on behalf of Europe, and of course Germany. Alas, since the 2008 crisis, America can no longer perform this role and the German working-class experiences, year by year, day by day, the fragmentation of this protective shield. It is now up to Germany and the rest of us Europeans to construct a rational mechanism for recycling within Europe our deficits and surpluses. If we fail, Europe will fail, Germany will fail and civilisation will be imperilled.

Judging by the current pre-election debate, none of the parties of government are even interested in having this debate. Thankfully, there are many smart members of existing parties that recognise the importance of this re-orientation of German politics. The German members of DiEM25, our Democracy in Europe Movement, are working feverishly to bring about a coalescence of these political actors into a new political movement that puts on the agenda this central issue. It is what Germany needs. It is what Europe needs.

Yanis Varoufakis is a professor of economics at the University of Athens and co-founder of the DiEM25 group. He served as Greek finance minister in the first Syriza government from January to July 2015, leading his country’s negotiations with the EU over the Greek debt crisis.

Click here for the original DW site.

September 10, 2017

For Europe’s sake, Britain must not be defeated – op-ed in The Sunday Times 10/9/2017

Yanis Varoufakis

September 10 2017, 12:01am, The Sunday Times

Varoufakis arrives at a meeting in Athens while he was the Greek finance ministerGETTY

Share

Brussels’s cheerleading journalists are at it again. Their mission? To aid and abet the EU negotiators in winning the blame game over the failure of Brexit negotiations that Brussels is doing all it can to guarantee.

That Michel Barnier and his team have a mandate to wreck any mutually advantageous deal there is little doubt. The key term is “sequencing”. The message to London is clear: you give us everything we are asking for, unconditionally. Then and only then will we hear what you want.

This is what one demands if one seeks to ruin a negotiation in advance.

Ever since Theresa May embarked on her ill-conceived journey towards an ill-defined hard Brexit, I have been warning my friends in Britain of what lies ahead. The EU would not negotiate with London, I told them. Under the guise of negotiations it would force May and her team to expend all their energies negotiating for the right to . . . negotiate.

Meanwhile, its media cheerleaders would work feverishly towards demeaning London’s proposals, denigrating its negotiators and reversing the truth in ways that Joseph Goebbels would have been proud of.

Right on cue came the leaks that followed the dinner that the prime minister hosted for Jean-Claude Juncker in 10 Downing Street on April 26 — their explicit purpose being to belittle their host. Then came the editorials by the usual suspects — the journalists that Brussels uses to leak its propaganda — deploring the “lack of preparation” by the British — using Berlin’s and Brussels’s favourite put-down that “they have not done their homework”.

As I promised on the day I resigned from Greece’s finance ministry, after my prime minister’s capitulation to that same Brussels-Berlin cabal, I wear their loathing with pride.

But I worry that Brussels and Berlin may succeed in damaging Britain, as they previously succeeded in damaging my people.

Reading between the lines, the message to London from the EU propaganda machine is fourfold:

The EU will not budge. Brussels’s worst nightmare is a mutually advantageous economic agreement that other Europeans may interpret as a sign that a mutiny against Europe’s establishment may be worthwhile. To ensure that there will be no such deal, Barnier and the European Commission have not been given a mandate to negotiate any concessions to Britain regarding future arrangements such as a free trade agreement.

Angela Merkel will not step in to save the day. The only national leader who is capable of intervening therapeutically did not do this for Greece and she will not do it for Britain.

London must not try to bypass the rule of EU law. Every time London makes a proposal, Brussels will reject it as either naive or in conflict with “the rule of EU law”; a legal framework for exiting so threadbare that it offers no guidance at all regarding the withdrawal of a member state from the union. In this light, when they speak of the “rule of law” what they really mean is the logic of brute force backed by their indifference to large costs inflicted on both sides of the English Channel.

Prepare your people for total capitulation — that is your only option.

None of this is new. It springs out of the EU playbook that was thrown at me during our 2015 negotiations. I had bent over backwards to compromise on a deal that was viable for Greece and beneficial to the rest of the eurozone. It was rejected because being seen to work with us risked giving ideas to the Spaniards, the Italians, indeed the French, that there was utility to be had from challenging the EU establishment.

To kill off any prospect of a mutually beneficial agreement, we were forced to negotiate with Barnier-like wooden bureaucrats lacking the mandate to negotiate, while Merkel turned a blind eye to the impending impasse. As for the “rule of law”, or the “rules” that German officials always appealed to, it was nothing but an empty shell that they filled with whatever directives suited them.

What can be done to prevent a capitulation that, in the end, would be bad for Britain and bad for Europe? Earlier this year I suggested that May accepts the impossibility of sensible negotiations with the EU. Once she accepts this, two options are available.

One option is to make the EU an offer it cannot afford, politically, to refuse. For example, request an off-the-shelf Norway-like (European Economic Area) agreement for an interim period of no less than seven years. Tactically, this would render redundant Barnier and his team; offer certainty for business, EU residents in Britain and Brits living in Europe; as well as allow Merkel to relax in the belief that the problem has been passed into the lap of her successor.

It would also serve the purpose of respecting Brexit, in the sense that Britain would leave the EU forthwith while restoring sovereignty to the House of Commons by giving MPs the space and the time fully to debate what future arrangements Britain wants to establish long-term with the EU.

The second option is the only one available if the immediate end of free movement and of the role of Europe’s courts in the UK is deemed paramount: unilaterally withdraw from all negotiations, leaving it to Brussels to come to London with a realistic offer regarding free trade and other matters.

If Brussels does not, it does not. While the EU is struggling to respond, the British government should grant British citizenship to all EU residents unconditionally, followed by a statement that secures the moral high ground: “We have no quarrel with Europeans. Indeed, we have just done what is right by EU citizens in the UK. Let us now see how our friends across the Channel behave.”

Of the two options, the first is immensely preferable. The second option will pile up great costs on British business, probably stir up renewed xenophobia and reinforce Europe’s reliance on authoritarian incompetence.

In contrast, the first option of a Norway-style interim arrangement gives parliament a genuine opportunity to debate Britain’s future without the eerie sound of a ticking clock in the background.

Maybe, by the time the interim transitional period that I propose has lapsed, the EU will be a democratic union that the people of Britain might want to rejoin. While the chances are slim, leaving that possibility open is a great source of desperately needed hope.

One of the reasons I opposed Brexit was that the UK would expend an inordinate amount of economic and political capital in pursuing withdrawal, ending up more intertwined with Brussels after Brexit than it was before.

In my view it was better to struggle against the EU’s anti-democratic establishment from within than from without. Alas, Britons were not persuaded by such arguments and voted to leave. As a democrat I respect their verdict, but fear that May will fall into the EU trap.

Meanwhile, Brussels’s cheerleaders are advising London to learn the wrong lessons from Greece.

The right lesson is to deny the EU the opportunity to wear Britain’s negotiators down until they capitulate. A Norway-style interim agreement or the immediate cessation of negotiations are the only two options.

As an Anglophile and a radical Europeanist I strongly support the former.

Yanis Varoufakis is co-founder of DiEM25, the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025, and the author of Adults in the Room: My Battle with Europe’s Deep Establishment published by Bodley Head, £20

[Click here for the site to The Sunday Times]

Yanis Varoufakis's Blog

- Yanis Varoufakis's profile

- 2451 followers