Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 111

January 27, 2018

Bloody Sunday, Brexit & The Democratic Process – Audio of speech, Derry, 26th January 2018

In what was a tremendous honour, the Bloody Sunday March organising committee invited me to Derry’s Guildhall to deliver the annual memorial lecture highlighting the legacy of Bloody Sunday and linking it with Brexit and DiEM25’s pan-European campaign for democracy and shared prosperity. An audio of my talk is now available here. Afterwards, I was treated to the even greater honour of a public discussion with the legendary civil rights campaigner Bernadette Devlin – DiEM25’s latest member!

Why ‘Bloody Sunday, Brexit & the democratic process?” – the rationale for this event, as published at the organisers’ website (click here)

Much like many other parts of the world at that time, the North of Ireland was undergoing a process of profound political change in the early 1970’s. By the time January 1972 came around the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) had already been holding peaceful protests and marches for close on 4 years.

From the outset the Northern state had chosen to respond violently to NICRA’s modest demands and this eventually led to the British government introducing armed troops onto the streets in August 1969. This militarised situation was further heightened with the commencement of the IRA’s bombing offensive in 1970.

Then in August 71 the state introduced internment without trial and on Sunday, January 30th 1972 NICRA responded by holding an anti-interment march in Derry city, which tragically ended with 28 civilian marchers being shot by the British army, 13 of whom died that day.

Today all across the world we see people continuing to express that desire for democratic change, whether that’s through the ‘Arab Spring’ protests, which erupted in many middle eastern countries several years ago or with Scotland’s Independence referendum of 2014 or last year with the UK’s ‘Brexit’ referendum and again more recently with the Catalonian government’s declaration of independence from the Spanish state.

Equally and despite the election last year of a racist, sexist, Islamophobe president the American people, by electing Donald Trump, have clearly demonstrated their desire for real and urgent democratic change.

What then does this all mean for global society and more specifically how might these seismic changes effect Ireland and its relationship with our nearest neighbour.

Britain’s Brexit decision has introduced an air of anxiety and instability into European politics, which in turn has provoked heated debate and soul searching around the question of the border here and for many this instability has brought the imperative of a united Ireland much closer.

However, in response to justified demands for change and accountability, many governments and institutions have chosen different forms of repression or censure, be that with the Spanish government’s recent violent response to democratic Catalonian nationalism, the EU’s punishing fiscal water-boarding of the Greek economy or through EU Troika diktats delivered to the Southern Irish state.

Allied to this we also worryingly see a growing sense of misanthropy from authority across the world, where people fleeing war, poverty and famine are being vilified and portrayed as the problem rather than the political systems or governments they are fleeing from.

It is in this context that the Bloody Sunday March Committee decided to invite acclaimed economist and former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis to address the question of why now are so many people across the world demanding change and democratic accountability and what in his view will these changes mean for the people of these islands.

Furthermore, given the hardening of positions and the general move to the right in European politics we have asked him to also offer his thoughts on what could happen if governments and institutions choose to resist and in some cases violently suppress those same democratic demands.

“Their Epitaph is in the Continuing Struggle for Democracy”

(Inscription on Bloody Sunday Monument, Rossville St. Derry)

January 22, 2018

How failing institutions boost inequality – Audio of presentation at Sciences Po, Paris, 22 JAN 2018

January 15, 2018

Bloody Sunday, Brexit & The Democratic Process: Public lecture, followed by ‘In conversation with Bernadette McAliskey’ – Derry, 26th January 2018, 7.30pm

Much like many other parts of the world at that time, the North of Ireland was undergoing a process of profound political change in the early 1970’s. By the time January 1972 came around the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) had already been holding peaceful protests and marches for close on 4 years.

From the outset the Northern state had chosen to respond violently to NICRA’s modest demands and this eventually led to the British government introducing armed troops onto the streets in August 1969. This militarised situation was further heightened with the commencement of the IRA’s bombing offensive in 1970.

Then in August 71 the state introduced internment without trial and on Sunday, January 30th 1972 NICRA responded by holding an anti-interment march in Derry city, which tragically ended with 28 civilian marchers being shot by the British army, 13 of whom died that day.

Today all across the world we see people continuing to express that desire for democratic change, whether that’s through the ‘Arab Spring’ protests, which erupted in many middle eastern countries several years ago or with Scotland’s Independence referendum of 2014 or last year with the UK’s ‘Brexit’ referendum and again more recently with the Catalonian government’s declaration of independence from the Spanish state.

Equally and despite the election last year of a racist, sexist, Islamophobe president the American people, by electing Donald Trump, have clearly demonstrated their desire for real and urgent democratic change.

What then does this all mean for global society and more specifically how might these seismic changes effect Ireland and its relationship with our nearest neighbour.

Britain’s Brexit decision has introduced an air of anxiety and instability into European politics, which in turn has provoked heated debate and soul searching around the question of the border here and for many this instability has brought the imperative of a united Ireland much closer.

However, in response to justified demands for change and accountability, many governments and institutions have chosen different forms of repression or censure, be that with the Spanish government’s recent violent response to democratic Catalonian nationalism, the EU’s punishing fiscal water-boarding of the Greek economy or through EU Troika diktats delivered to the Southern Irish state.

Allied to this we also worryingly see a growing sense of misanthropy from authority across the world, where people fleeing war, poverty and famine are being vilified and portrayed as the problem rather than the political systems or governments they are fleeing from.

It is in this context that the Bloody Sunday March Committee decided to invite acclaimed economist and former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis to address the question of why now are so many people across the world demanding change and democratic accountability and what in his view will these changes mean for the people of these islands.

Furthermore, given the hardening of positions and the general move to the right in European politics we have asked him to also offer his thoughts on what could happen if governments and institutions choose to resist and in some cases violently supress those same democratic demands.

“Their Epitaph is in the Continuing Struggle for Democracy”

(Inscription on Bloody Sunday Monument, Rossville St. Derry)

Event Details

Date:January 26, 2018 7:30 pm – 9:00 pm

Venue:The Guildhall

Categories:2018 Event, Discussion and Q&A

We are delighted to confirm that acclaimed economist and former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis will deliver this public lecture. It will be followed by ‘In Conversation’ with Bernadette McAliskey before moving to a Q & A with the assembled audience.

Admission by Donation Come early not to be disappointed! (Bloody Sunday March Committee is an non-funded organisation and relies on public donations to fund its work)

Context 2018

Bloody Sunday was a local event. All of the 28 dead and wounded came from the general Bogside/Creggan quarter of Derry, population around 35,000. There was no one in the area who didn’t know the family of at least one of the victims. The massacre was experienced as a communal wound, the pain of which still throbs and won’t ease until all of the families can feel that truth has been told and justice done.

It is this which, 46 years later, drives the annual commemoration.

Bloody Sunday differs from the other massacres in the North which stand like grave-stones marking the passing of the years of conflict. The killing took place in bright daylight, watched at close quarters by hundreds of local people who had earlier marched for civil rights, stunned by horror, outrage and grief inflicted by men uniformed to represent the British State.

Bloody Sunday cannot be put down to ancient Irish hatreds. It was rooted in imperial history, in the scorn of Empire for the lives of plain people and the ferocious rage of the ruling class at any uprising of the lower orders. Hence the Tory Government’s sigh of relief in 2010 when the Inquiry under Lord Saville pointed the finger of blame at a bunch of squaddies and one undisciplined officer.

Parties jostling for political advantage and wishing the issue over and done with embraced Saville’s conclusions as full and final. Families of victims of State violence around the world will recognise the pattern.

We want the shooters charged and tried – and the politicians and top brass who gave the go-ahead brought to book.

As always we use the commemoration to give focus to other local, national and international events that resonate with the cause of justice.

With this year also being the 50th anniversary of the Northern state’s attack on civil rights marchers in Derry’s Duke street we remember those who marched that day and all of those other people around the world who continue to march and protest for democratic change and accountability.

We stand in solidarity with all who face lies and intimidation from the State and its propagandists as they continue the trek towards truth. Ballymurphy, Kingsmills, Loughinisland. Birmingham. Black Lives Matter, Grenfell Tower. Syria, Yemen, Kenya. And, always, Palestine.

We owe it to all who yearn for justice not to weaken now, and we won’t.

One world, one struggle. We shall Overcome.

“La crisis se está haciendo más profunda, más tóxica, más permanente” (“The crisis is getting deeper, more toxic, more permanent”) – El Diario interview, 13/1/2018 (including the original English text of the interview)

“El Gobierno español actuó firmemente en Bruselas contra los intereses de la inmensa mayoría de los españoles”

“El bitcoin es una espléndida burbuja y nunca podrá operar provechosamente como moneda”

El ex ministro griego de Finanzas Yanis Varoufakis NEAL MCQUEEN

El ex ministro griego de Finanzas Yanis Varoufakis NEAL MCQUEENMÁS INFO

‘Adultos en la habitación’ Las bambalinas de la alta política contadas por un forastero prodigioso: Yanis Varoufakis

“Los procesos de autodeterminación siempre tienen un coste económico”

ETIQUETAS: Yanis Varoufakis,crisis económica

Yanis Varufakis (Atenas, 1961) fue ministro de Finanzas griego durante sólo siete meses, de enero a julio de 2015, pero su peculiar estilo, cercano al de una estrella del rock, marcó una época en el adusto ambiente del Eurogrupo y de la política económica europea.

Más allá de la anécdota de su negativa a usar corbata, de sus solapas levantadas y de sus cazadoras de cuero –que aceptó cambiar por una bufanda de Burberry en alguna ocasión– Varoufakis ocupó titulares por sus batallas con la troika. Luchó contra la austeridad impuesta a su castigado país a cambio del “ rescate“. Acabó perdiendo la batalla.

Según su antiguo aliado y hoy adversario, el primer ministro heleno Alexis Tsipras, el exministro se excedió en el pulso y sus retrasos e indecisiones provocaron que Grecia perdiera miles de millones de euros.

Varoufakis, cofundador del movimiento paneuropeo DIEM25, que se presentará a las próximas elecciones europeas, da su versión de los hechos en su último libro, “Comportarse como adultos” (Deusto, 2017), recién publicado en España. Responde a las preguntas de eldiario.es por correo electrónico.

En su libro describe usted una conversación con el ex secretario del Tesoro estadounidense Larry Summers en la que él le conmina a decidir si estar “dentro”, con los que realmente toman las decisiones o “fuera”, con los que pueden decir la verdad. ¿Por qué decidió quedarse fuera? ¿no es mejor estar dentro para intentar cambiar las cosas, siquiera ligeramente?

Mi intención en todo momento era permanecer “dentro” tanto tiempo como fuera posible para ayudar a Grecia a escapar de la prisión de sus acreedores. Quedarme “dentro” para conseguir diferencias mínimas, a costa de legitimar un encarcelamiento injusto, no es para lo que fui elegido.

¿Esperaba usted un comportamiento diferente de los líderes europeos antes de empezar a negociar con ellos, y si es así por qué?

No, realmente no. Solo acepté ser ministro de Finanzas porque había predicho que los poderosos iban a intentar asfixiarnos, y trabajé duramente para elaborar un plan de disuasión. Lo que no esperaba era que nuestro propio bando pasaría por el aro y renunciaría a nuestro plan disuasorio antes de ponerlo en práctica. La única sorpresa que me deparó la facción de los acreedores es que ¡no esperaba que los representantes de la UE, el BCE y el FMI tuvieran tan bajo nivel!

¿Es Europa democrática? ¿No se suponía que la UE era más democrática y justa desde un punto de vista económico que zonas del mundo como los Estados Unidos?

No, Europa es exactamente lo opuesto a democracia. Aunque es verdad que nuestros estados miembros son democracias en su funcionamiento, “Europa” (es decir, la Unión Europea) es una “zona libre de democracia”. Y aquí está el enigma: Estados perfectamente democráticos han transferido todas las decisiones cruciales a un centro que carece totalmente de carácter democrático. En comparación, los defectuosos y muy problemáticos Estados Unidos son un parangón de democracia. ¡Este es el triste estado de nuestra Europa hoy!

¿Cuál fue, en su opinión, el papel específico del ministro de Economía español, Luis de Guindos, y de España durante la crisis griega? España también atravesaba una situación crítica en ese momento…

Por favor, no utilice “España” y “gobierno español” (o sus ministros) indistintamente. El Gobierno español actuó firmemente en Bruselas contra los intereses de la inmensa mayoría de los españoles. Su imposición de austeridad para las masas y de socialismo para los banqueros y la oligarquía hizo que la administración Rajoy tuviera miedo del pueblo español . Así, De Guindos tenía estrictas órdenes (en el Eurogrupo) de hacer todo lo posible para que nuestro gobierno fuera aplastado y nuestras moderadas propuestas rechazadas. ¿Por qué? Por el miedo del Gobierno de Rajoy de que Syriza obtuviera un acuerdo decente en el Eurogrupo, ya que entonces los españoles se revolverían contra él por haber vendido a España.

Alexis Tsipras ha dicho que su plan económico era “débil e ineficaz” y que su comportamiento le pudo costar a Grecia miles de millones de euros. ¿Por qué cree que está haciendo estas declaraciones? ¿le parece justo?

Entiendo bien por qué aquellos que se rindieron se ven obligados a buscar su absolución denigrando a aquellos que se negaron a rendirse. Es, desgraciadamente, parte de la naturaleza humana, aunque sea profundamente triste al mismo tiempo.

En la actualidad, líderes europeos, incluyendo al Gobierno español, afirman que la crisis ha terminado gracias a las medidas de austeridad implementadas los últimos cinco años. Aunque las cifras de paro hayan mejorado, las condiciones laborales han empeorado y hay más desigualdad que antes en la UE. ¿Cuál es su visión de la situación económica presente, particularmente en los países mediterráneos?

Se sabe que un régimen ha excedido su capacidad de mantenerse cuando empieza a celebrar el fin de una crisis en el momento en el que la crisis empeora. Esta es la situación actual en Europa. Se parece, de forma importante, a lo que ocurría en 2002, aproximadamente un año después del estallido de la burbuja tecnológica: Aquel régimen estaba celebrando el final de la crisis en el preciso momento en el que el capitalismo financiero iba rumbo al abismo de 2007/2008.

Sí, el desempleo está cayendo. Pero cae porque los jóvenes están emigrando de nuestros países (como España y Grecia) y además, sustantivamente, porque muchos trabajos precarios y mal pagados se crearon para reemplazar trabajos mejor pagados y a tiempo completo. Lo que es, en otras palabras, una catástrofe para el trabajo asalariado ha sido celebrada como… recuperación. En realidad, la crisis se está haciendo más profunda, más tóxica, más permanente.

Mientras la deuda pública y privada es cada vez más alta, la burbuja inmobiliaria parece estar reapareciendo en España, con precios en escalada otra vez en determinadas zonas. ¿Qué podemos esperar del futuro si seguimos por el mismo camino? ¿debería el BCE elevar los tipos de interés el año próximo, como anticipan muchos analistas y qué efecto tendrá en las economías periféricas?

Debemos esperar que se prolongue el estancamiento. Los tipos de interés seguirán bajos mientras la inversión siga en niveles tan bajos como los actuales: Cuando la demanda de los fondos de inversión tira a la baja la oferta (como por ejemplo, los ahorros) el precio del dinero, los tipos de interés, deben manterse a la baja. El BCE no puede hacer nada para resolver esta cuestión. No tiene capacidad. Solo la UE puede poner en marcha un “new deal” europeo -como DiEM25 explica y defiende- basado en la colaboración entre el Banco Europeo de Inversión (que debería emitir 500.000 millones de euros de bonos BEI con los que obtener inversiones para proyectos ecológicos) y el Banco Central Europeo (que debe anunciar que está dispuesto a comprar esos bonos si es necesario). Sin un programa de inversión europeo dirigido como este, una subida de tipos de interés simplemente aplastaría a los sectores privados y públicos de los países periféricos europeos.

¿Cuáles cree que pueden ser las consecuencias de la salida del Reino Unido, elbrexit, de la Unión Europea?

La aceleración de la insidiosa y lenta quema de Europa, su efectiva desintegración.

DiEM25, el movimiento del que es co-fundador, ha anunciado su participación en las elecciones europeas. ¿Qué distingue a DIEM25 de otras formaciones políticas progresistas en Europa, y por qué cree que va a tener mejor comportamiento electoral que el que recientemente han tenido otras fuerzas progresistas en países como Francia, Alemania o Austria?

DiEM25 está haciendo algo que nunca se había intentado: la participación de candidatos locales (como parte de una única lista transnacional) en distintos países europeos en las elecciones de mayo de 2019 al Parlamento Europeo, sobre la base de una única agenda económica, social y política progresista para Europa. Por primera vez, los votantes europeos tendrán la oportunidad de votar en estas elecciones al Parlamento Europeo sobre lo que Europa debe hacer para la mayoría, no para una minoría, en lugar de desperdiciar sus votos en otras elecciones europeas que los partidos nacionales utilizarán cínicamente como una encuesta de opinión magnífica para uso político doméstico. Apoyando en distintos países europeos una misma agenda progresista para toda Europa, DiEM25 demostrará que otra Europa no solo es posible, ¡sino está aquí!

Para terminar. ¿Qué opina de los bitcoins? ¿Qué efectos podría tener en la economía una explosión de esta presunta burbuja?

Es una espléndida burbuja y nunca podrá operar provechosamente como moneda. En todo caso, la tecnología en la que se basa está teniendo muchas aplicaciones útiles -y tendrá, sin duda, muchas más. De que la burbuja del bitcoin explotará no tengo duda. Afortunadamente, el efecto de su explosión en la economía será insignificante, salvo, por supuesto, que hasta que eso ocurra los financieros logren indexar el precio del bitcoin con otras burbujas de complejas formas de deuda. Hace poco me fijé con cierto temor en gente pidiendo préstamos de moneda fiduciaria en los mercados para comprar bitcoins. Si esta tendencia crece, los riesgos de una explosión de la burbuja del bitcoin se multiplicarán.

ORIGINAL ENGLISH LANGUAGE RESPONSES TO THE INTERVIEWER’S QUESTIONS

In your book, you describe a conversation with Larry Summers in which he asked you: “do you want to be on the inside or the outside?” Why did you ultimately decide to stay in the “outside”? Isn’t it better to be in the “inside” and try to change things, even a little bit?

I had every intention of staying ‘inside’ as long as it was possible to help Greece escape debtors’ prison. Staying in to make marginal differences, at the cost of legitimising an illegitimate incarceration was not what I had been elected to do

Did you expect a different behaviour from European leaders before you started to negotiate with them – and if so why?

No, not really. I only accepted the finance ministry because I had predicted that the powers-that-be would try to asphyxiate us, and I had worked hard to come up with a deterrence plan. What I had not expected was that our own side would buckle under and surrender our deterrent before it was used. The only surprise that the creditors’ side had in store for me was that I had not expected the representatives of the EU, the ECB and the IMF to be of such low quality!

Is Europe democratic? Isn’t the EU more democratic and economically more just than other areas like the US?

No, Europe is the exact opposite of democratic. While it is true that our member-states are functioning democracies, ‘Europe’ (i.e. the EU) is a democracy-free zone. And here is the conundrum: Perfectly democratic states have passed on all the crucial decisions to a centre lacking totally of democracy. By comparison, the flawed and highly problematic USA is a paragon of democracy. Such is the sad state of our Europe today!

What do you think was the specific role of Luis de Guindos and Spain during the Greek crisis? Spain was also going through a critical situation at the time…

Please do not use Spain and the Spanish government (or its ministers) interchangeably. The Spanish government has steadfastly operated in Brussels against the interests of the vast majority of Spaniards. Their imposition of austerity for the masses and socialism for the bankers and the oligarchy rendered the Rajoy administration fearful of the Spanish people. Thus, de Guindos was under strict orders (in the Eurogroup) to do his damnest to ensure that our government was crushed and our moderate proposals rejected. Why? Because of Rajoy’s fear that if Syriza got a decent deal at Eurogroup level, then the Spanish people would turn against him and his ministers for having sold Spain out.

Alexis Tsipras has said that your economic plan was “weak and ineffective” and that your behaviour may have cost Greece billions. Why do you think he is making these statements? Do you find this fair and what is your response to his allegations?

I understand well why those who surrender must seek absolution in denigrating those refused to surrender. It is unfortunately part of human nature, while being ultra sad at the same time.

At the present time, European leaders including the current Spanish government claim that the crisis is over due to the austerity measures that were implemented over the past 5 years. Although unemployment figures have improved, labour conditions have worsened and there is more inequality than before across the Union. What is your assessment of the current economic situation, particularly for the Mediterranean countries?

You know that a regime has exceeded its capacity to maintain itself when it begins to celebrate the end of a crisis at the moment the crisis worsens. This is the state of play today in Europe. It resembles, in important ways, what was going on in 2002 – a year or so after the bursting of the dot.com NASDAQ and Wall Street bubbles: That regime was celebrating the end of the crisis just as financialised capitalism was heading for the rocks of 2007/8.

Yes, unemployment is falling. But it fell because youngsters migrated from our countries (e.g. Spain and Greece) plus, importantly, because many new precarious, badly paying jobs were created to replace better paying full time jobs. What was, in other words, a catastrophe for waged labour is being celebrated as… recovery. In truth, the crisis is growing deeper, more toxic, more permanent.

While public and private debt remain high, the housing bubble seems to be reappearing in Spain as prices are on the rise again. What should we expect in the future should we stay on the current path? Should the ECB in fact raise interest rates over the next year, as many analysts anticipate, what effect would higher rates have in the economy of the periphery?

What we should expect is further stagnation. Interest rates will remain low as long as investment is as low as it is: when the demand for investment funds is lagging the supply (i.e. savings), the price of money (interest rates) must remain low. The ECB can do nothing to resolve this issue. It is powerless. Only the EU can effect a European New Deal – as DiEM25 explains and advocates – based on a collaboration between the European Investment Bank (that should issue 500 billion euros of EIB bonds by which to raise funding for green investments) and the European Central Bank (that must announce its readiness to buy these bonds if need be). Without such a European New Deal investment-led recovery program, an interest rate rise will simply crush the private and public sectors of Europe’s periphery.

What do you think will be the consequences of “brexit” for the Union?

The acceleration of Europe’s insidious, slow burning, effective disintegration.

DiEM25, the movement you co-founded, has announced its participation in elections. What distinguishes DiEM25 from other progressive political formations in Europe, and why do you believe it will have a better chance to succeed given the recent electoral performance of progressive forces in France, Germany, Austria…?

DiEM25 is doing something that has never been tried before: Field candidates (as part of a SINGLE transnational party list) across many different European countries in the May 2019 European Parliament election on the basis of a SINGLE economic, social and political progressive agenda for Europe. For the first time European voters will have the opportunity of voting in the European Parliament elections about what Europe must do for the many, not for the few – instead of wasting their votes in another European election that national parties cynically use as a glorified opinion poll for domestic political use. By standing across different countries with ONE progressive agenda for the whole of Europe DiEM25 will demonstrate that another Europe is not just possible: It is here!

And to finish: what do you think about bitcoins? What effects could a burst in the Bitcoin burst have in the economy?

It is a glorious bubble and can never operate usefully as a currency. However, the technology on which it is based is already having many useful applications – and will, undoubtedly, have a lot more. That the bitcoin bubble will burst there is no doubt. Thankfully, the effect of its bursting on the economy will be negligible, unless of course financiers manage, in the meantime, to link the price of bitcoin up to other bubbles involving convoluted forms of debt. Recently, I observed with some trepidation people borrowing fiat currencies in the markets to buy bitcoin. If this trend grows, the dangers from bitocoin’s burstingwill multiply.

Πατριωτικό καθήκον η υπέρβαση του «Μακεδονικού» – ΕφΣυν 13 ΙΑΝ 2018

Αρχές του 2018 δεν δικαιούμαστε να επιτρέψουμε στον απόηχο του εικοσιπενταετούς σίριαλ του «Μακεδονικού» να στοιχειώσει τη νέα χρονιά. Ενα τέταρτο αιώνα έχει περάσει από 1991. Ενα τέταρτο αιώνα κατά τη διάρκεια του οποίου η Ελλάδα πέρασε από το ψεύδος της ευημερίας στο όνειδος της αυτοτροφοδοτούμενης λιτότητας, το οποίο έφερε την ουσιαστική απώλεια εθνικής κυριαρχίας.

Η χώρα μας σήμερα βρίσκεται γονατισμένη, σε κατάσταση μόνιμης κρίσης, υπό τα δεσμά μιας χρεοδουλοπαροικίας που μονιμοποιείται την ώρα που τρόικα και κυβέρνηση προσποιούνται ότι ήγγικεν το τέλος της.

Τη στιγμή αυτή, τώρα που η πατρίδα ερημοποιείται –με τους νέους να μεταναστεύουν καθημερινά και τις επιχειρήσεις είτε να κλείνουν είτε να αποχωρούν–, οι υπερπατριωτικές κορόνες για την ονομασία της γειτονικής χώρας αποτελούν το άκρον άωτον της υποκρισίας.

Το 2018 ο αυθεντικός πατριωτισμός απαιτεί από εμάς να μην αποπροσανατολιστούμε από το μέγα ζητούμενο της εποχής μας: την απελευθέρωση της χώρας από τους δανειστές και την ιδιόμορφη αποικία χρέους στην όποια έχουν καταδικάσει (σε αγαστή συνεργασία με την εγχώρια ολιγαρχία) τη συντριπτική πλειονότητα των Ελλήνων.

Για να αποτραπεί αυτός ο αποπροσανατολισμός και να επανακτήσουμε την εθνική και λαϊκή κυριαρχία, που έχουμε τόσο τραγικά απολέσει, απαιτείται λογική, αρετή αλλά και τόλμη.

Πρώτα απ’ όλα απαιτείται ψύχραιμη αποτίμηση δύο ξεκάθαρων δεδομένων:

1. Η αρχαία Μακεδονία, προφανώς, ήταν απολύτως και αποκλειστικά ελληνική – όσο ελληνικές ήταν κι η Σπάρτη, η Θήβα, η Αθήνα, η Εφεσος.

2. Η γεωγραφική περιοχή της αρχαίας Μακεδονίας δεν είναι σήμερα ελληνική, αλλά μοιράζεται μεταξύ τουλάχιστον τριών κρατών (ένα εκ των οποίων η Ελλάδα).

Συνεπώς, ενώ το σύνθημα «Η αρχαία Μακεδονία ήταν ελληνική» είναι απολύτως ορθόν, το σύνθημα του 1991 «Η Μακεδονία ήταν και θα είναι ελληνική» είναι ανακριβές, εκτός κι αν εννοούμε ότι εθνικός μας στόχος είναι η βίαιη προσάρτηση περιοχών της Βαλκανικής που σήμερα ανήκουν σε άλλες χώρες – ένας παρανοϊκός και επικίνδυνος στόχος που κανείς σώφρων πατριώτης δεν ενστερνίζεται.

Περνάμε τώρα στο δεύτερο ζήτημα: Ποιος δικαιούται να παρουσιάζεται ως Μακεδόνας και ποιος όχι; Εδώ υπάρχουν δύο απόψεις.

Μία άποψη είναι ότι μόνον οι Ελληνες έχουμε το δικαίωμα να αυτοπροσδιοριζόμαστε ως Μακεδόνες, εφόσον βέβαια μεγαλώσαμε ή ζούμε στην περιοχή της αρχαίας Μακεδονίας – καθώς ένας Κρητικός που ζει στην Κρήτη ούτε θέλει, φαντάζομαι, ούτε έχει νόημα να αποκαλείται Μακεδόνας. Από την άλλη, γνωρίζω Κρητικούς που μετά μερικά χρόνια στη Μακεδονία θεωρούν τους εαυτούς τους, εύλογα, (και) Μακεδόνες.

Το ερώτημα όμως τίθεται: Ενας μη Ελληνας που ζει χρόνια πολλά στην περιοχή της Αρχαίας Μακεδονίας δεν μπορεί να αισθάνεται, να αυτοπροσδιορίζεται Μακεδόνας;

Γνωρίζω, π.χ., ζευγάρι Αγγλων που ζουν στη Βόρεια Ελλάδα από το 1975, όπου μεγάλωσαν τρία παιδιά τα οποία (εύλογα) νιώθουν Ελληνες, Αγγλοι και Μακεδόνες. Θα αρνηθεί κανείς το δικαίωμα σε αυτά τα παιδιά να αυτοπροσδιορίζονται Μακεδόνες; Σε ποια βάση; Οτι μόνον οι Ελληνες έχουν το δικαίωμα να απονέμουν τον τίτλο του (επίτιμου;) Μακεδόνα σε όποιον ζει ή μεγάλωσε στην περιοχή της Αρχαίας Μακεδονίας;

Ετσι προκύπτει η δεύτερη άποψη: Το δικαίωμα (όχι βέβαια την υποχρέωση) στον αυτοπροσδιορισμό «Μακεδόνας» το έχουν όσοι ζουν ή μεγάλωσαν στην περιοχή της αρχαίας Μακεδονίας. Οπερ μεθερμηνευόμενον, και οι κάτοικοι των Σκοπίων, του Τετόβου, χωριών και πόλεων της Βουλγαρίας που εμπίπτουν στην περιοχή της αρχαίας Μακεδονίας.

Ερχόμαστε έτσι στο τρίτο ζήτημα: Ποια περιοχή, νομός ή κράτος έχει το δικαίωμα στη λέξη (ή παράγωγα της λέξης) «Μακεδονία»; Αν οι κάτοικοι μιας τοπικής κοινωνίας αισθάνονται Μακεδόνες, το να τους στερήσει κανείς το δικαίωμα της χρήσης παράγωγου της λέξης «Μακεδονία» ή «Μακεδονικού» στο τοπωνύμιό τους έχει βάση μόνον αν είτε

(α) κανένας νομός, πόλη, περιφέρεια ή κράτος δεν έχει το δικαίωμα στη λέξη αυτή είτε

(β) το μονοπώλιο της εν λόγω λέξης ανήκει σε άτομα ή κρατικούς θεσμούς με ελληνική ιθαγένεια.

Το να μην μπορεί κανένας νομός, πόλη ή κράτος στην ευρύτερη γεωγραφική περιοχή της αρχαίας Μακεδονίας να χρησιμοποιεί τη λέξη Μακεδονία ή παράγωγά της είναι αστείο και απορριπτέο (κατ’ αρχάς από τους Ελληνες Μακεδόνες).

Το να απαιτείται ελληνική άδεια για τη χρήση του όρου Μακεδονία σε πόλεις και κρατικές οντότητες στη γεωγραφική περιοχή της αρχαίας Μακεδονίας όπου ζουν μη Ελληνες που όμως νιώθουν Μακεδόνες συγκρούεται με τη λογική και υπερβαίνει τα όρια του ρατσισμού.

Κάπως έτσι φτάνουμε στο τέταρτο και φλέγον ζήτημα: Δικαιούται κράτος επί της γεωγραφικής περιοχής της αρχαίας Μακεδονίας να αποκαλείται «Δημοκρατία της Μακεδονίας»;

Η ένσταση σε μια τέτοια ονομασία όσων συμφωνούν με τα πιο πάνω επικεντρώνεται στο εξής σημείο: Αλλο το να δικαιούσαι να νιώθεις Μακεδόνας (ανεξαρτήτως εθνότητας, γλώσσας κ.λπ.) λόγω της σχέσης σου με τη γεωγραφική περιοχή της αρχαίας Μακεδονίας ή να ταυτίζεις τον τόπο σου με τη Μακεδονία, και άλλο να προσπαθείς να μονοπωλήσεις τον όρο Μακεδονία, αφήνοντας υπονοούμενα αλυτρωτισμού και καλλιεργώντας τον επεκτατισμό τής εν λόγω Δημοκρατίας εναντίον, π.χ., της ελληνικής Μακεδονίας.

Το συμπέρασμα είναι απλό: Ονομασία που κάνει χρήση της λέξης «Μακεδονία» ή παραγώγων της, είναι θεμιτή εφόσον δεν τη μονοπωλεί ο χρήστης της παραπέμποντας σε αλυτρωτισμό-επεκτατισμό.

Τρόποι για να δηλωθεί ευθαρσώς (και με ισχύ στο Διεθνές Δίκαιο) η μη μονοπώληση και να εξορκιστεί ο αλυτρωτισμός-επεκτατισμός υπάρχουν πολλοί – εφόσον υπάρχει η πολιτική βούληση Σκοπίων και Αθηνών.

Επί προσωπικού

Γνωρίζοντας ότι θα στενοχωρήσω φίλους και θα χαροποιήσω αντιπάλους, νιώθω την ανάγκη να προχωρήσω πέραν της πιο πάνω ανάλυσης, αναφερόμενος στην προσωπική μου αντιμετώπιση του νεότερου «Μακεδονικού» ζητήματος.

Από το 1991 θεωρούσα ότι μπαίναμε σε περιπέτεια άνευ ουσιαστικού λόγου, εμφανίζοντας παγκοσμίως μια εικόνα που δεν μας τιμά. Τα καμώματα των «Σκοπιανών» (με τους Μεγάλους Αλεξάνδρους και τον χυδαίο αλυτρωτισμό τους) τα έβλεπα –και τα βλέπω– όπως έβλεπα, μικρό παιδί, τα άρματα και τους κίονες των συνταγματαρχών στο Καλλιμάρμαρο: με αποστροφή και ειρωνεία. Το ίδιο ακριβώς όμως ένιωθα βλέποντας τα δικά μας καμώματα και τις υστερίες.

Ευχόμουν να είμαστε, ως λαός, υπεράνω –να έχουμε το σθένος και την αρετή να αντιδράσουμε στους εθνικιστές της γείτονος με χιούμορ–, να λέμε: «Αν θέλετε να ονομάζεστε Κλίγκον (σ.σ.:οι εχθροί του Κάπτεν Κερκ στο… Σταρ Τρεκ), δεν έχουμε αντίρρηση. Αν θέλετε να δανειστείτε τον όρο “Δημοκρατία των Αθηνών ή της Σπάρτης” ή ό,τι άλλο, κοπιάστε».

Ευχόμουν ακόμα να μπορέσουμε να διακρίνουμε τη σημασία της αποφυγής ενός εμφύλιου πολέμου στα σύνορά μας μεταξύ Αλβανών και Σλάβων – ένας εμφύλιος που (αντίθετα με τη Βοσνία και το Κόσοβο) απεφεύχθη (τουλάχιστον έως σήμερα) σε μεγάλο βαθμό επειδή Σλάβοι και Αλβανοί βρήκαν μια δανεική ταυτότητα (τη «Μακεδονική») για να τους ενώνει.

Ευχόμουν να επικεντρωθούμε όχι στο όνομα αλλά στην αποφασιστικότητα με την οποία θα υπογραφούν συνθήκες και πρωτόκολλα που θα αποτρέπουν τον αλυτρωτισμό-επεκτατισμό.

Αυτές οι «ευχές» δεν ευοδώθηκαν. Ως αποτέλεσμα, χάσαμε ένα τέταρτο του αιώνα ενώ η «Δημοκρατία της Μακεδονίας» αναγνωριζόταν από την πλειονότητα των χωρών του πλανήτη και οι εθνικιστές (και από τις δύο πλευρές των συνόρων) ωφελούνταν από την αποξένωση/εχθρότητα μεταξύ ενός φτωχού σλαβο-αλβανικού λαού και του (υπό διαδικασία πτωχοποίησης) ελληνικού λαού.

Για τους Ινδιάνους…

Θα κλείσω με μήνυμα που έλαβα πρόσφατα από τον Τάκη Μίχα από τη Λατινική Αμερική – το οποίο συμπληρώνει πλήρως τα συναισθήματά μου:

Και, τώρα που ξαναρχίζει με αφορμή το Μακεδονικό η εθνικιστική υστερία, θυμάμαι με νοσταλγία τις εθνικές γιορτές στην Κουένκα των Ανδεων όπου ζούσα. Οι μαθητές, οι στρατιώτες και οι πολίτες παρήλαυναν χορεύοντας τοπικούς χορούς μπροστά από τους επίσημους, μεταξύ των οποίων την πιο περίοπτη θέση δεν είχε ούτε ο βουλευτής ούτε ο νομάρχης ούτε ο μητροπολίτης, αλλά η Βασίλισσα των Καλλιστείων της πόλης!

Ούτε άκουσα ιερωμένο της Καθολικής Εκκλησίας να προωθεί την αντίληψη μιας “εθνικής θρησκείας”. Και στις ομιλίες των επισήμων ποτέ δεν άκουσα κηρύγματα μίσους ή αλυτρωτισμού εναντίον “προαιώνιων” εχθρών, παρ’ όλο που φυσικά μπροστά στην Ισπανική κατοχή η Οθωμανική ήταν υπόδειγμα πολιτισμού. Και η ημέρα της εθνικής εορτής ήταν μια τεράστια φιέστα με κονσέρτα κλασικής και μοντέρνας μουσικής, εκθέσεις ζωγραφικής, επιδείξεις γαστρονομίας, χορούς στους δρόμους κ.λπ. με φυσικά έντονη την παρουσία των διάφορων φυλών Ινδιάνων τις οποίες η κυβέρνηση της χώρας αναγνωρίζει ως εθνότητες

January 14, 2018

Internationalism vs Globalisation – op-ed in The Globe & Mail, published as “Globalization is stuck in a trap. What will it be when it breaks free?” – 12 JAN 2018

Back in 1991, a left-wing friend expressed his frustration that “really existing socialism” was crumbling, with exaltations of how it had propelled the Soviet Union from the plough to Sputnik in a decade.

Back in 1991, a left-wing friend expressed his frustration that “really existing socialism” was crumbling, with exaltations of how it had propelled the Soviet Union from the plough to Sputnik in a decade.I remember replying, under his pained and disapproving gaze: “So, what? No unsustainable system can be, ultimately, sustained.” Now that globalization is also proving unsustainable, and is in retreat, its liberal cheerleaders resemble my friend when they proffer similarly correct, yet irrelevant, exaltations of how it lifted billions from poverty.

Progressives who had opposed globalization, like my left-wing friend in 1991, can take no solace from the manner in which globalization is retreating.

At the discursive level, neo-parochialism is now trumping globalization’s oeuvre in the United States, in Brexit Britain and elsewhere. Labour-saving technological change, meanwhile, underpins jobless deglobalization everywhere. None of these developments augur well for those who once believed in a borderless commonwealth of working people.

Humanity has been globalizing since our ancestors left Africa, the earliest economic migrants on record. Moreover, capitalism has been operating for two centuries like “heavy artillery,” in Marx and Engels’ words, using the “cheap prices of commodities” to batter “down all Chinese walls,” “constantly expanding market for its products” and replacing “the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency” with “intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations.”

It wasn’t until the 1990s, when we noticed the unleashing of momentous forces, that we required a new term to describe the emancipation of capital from all fetters, which led to a global economy whose growth and equilibrium relied on increasingly unbalanced trade and money movements. It is this relatively recent phenomenon – globalization, we called it – that is now in crisis and in retreat.

Only an ambitious new internationalism can help reinvigorate the spirit of humanism on a planetary scale. But before arguing in favour of that antidote, it is worthwhile recounting globalization’s origins and internal contradictions.

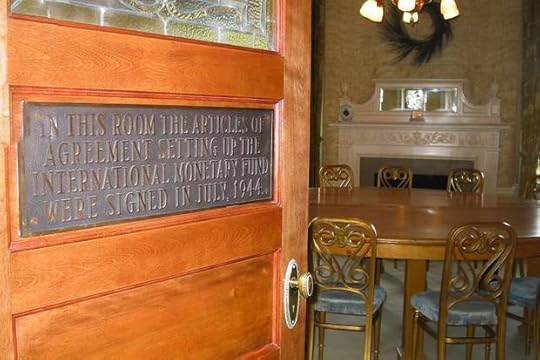

At the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, N.H., world leaders gathered in the Gold Room in July, 1944, to sign an agreement that created the World Bank and International Monetary Funds, pillars of what would come to be called the Bretton Woods monetary system.

In 1944, the New Deal administration in Washington understood that the only way to avoid the Great Depression’s return at war’s end was to transfer America’s surpluses to Europe (the Marshall Plan was but one example of this) and Japan, effectively recycling them to generate foreign demand for all the gleaming new products – washing machines, cars, television sets, passenger jets – that American industry would switch to from military hardware.

Thus began the project of dollarizing Europe, founding the European Union as a cartel of heavy industry, and building up Japan within the context of a global currency union based on the U.S. dollar. This would equilibrate a global system featuring fixed exchange rates, almost-constant interest rates and boring banks (operating under severe capital controls).

This dazzling design, also known as the Bretton Woods system, brought us a golden age of low unemployment and inflation, high growth and impressively diminished inequality.

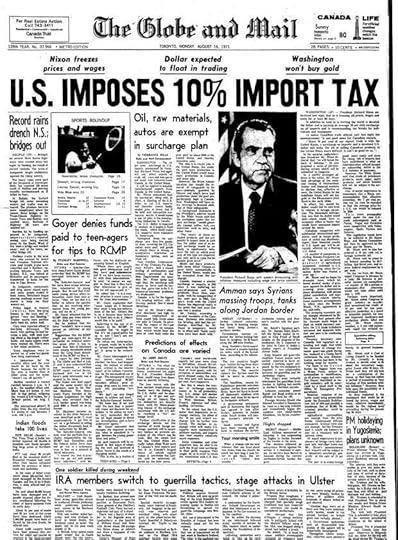

Alas, by the late 1960s, it was dead in the water. Why? Because the United States lost its surpluses and slipped into a burgeoning twin deficit (trade and federal budget), rendering it no longer able to stabilize the global system. Never too slow to confront reality, Washington killed off its finest creation: On Aug. 15, 1971, then-president Richard Nixon announced the ejection of Europe and Japan from the dollar zone. Unnoticed by almost everyone, globalization was born on that summer day.

Aug. 16, 1971: On its front page, The Globe and Mail documents the previous day’s surprising monetary shift from the Nixon administration, which would come to be called the Nixon Shock.THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Aug. 16, 1971: On its front page, The Globe and Mail documents the previous day’s surprising monetary shift from the Nixon administration, which would come to be called the Nixon Shock.THE GLOBE AND MAILMr. Nixon’s decision was founded on the refreshing lack of deficit phobia particular to American decision-makers. Unwilling to rein in deficits by imposing austerity (that would have done more to shrink the country’s capacity to project hegemonic power around the world than shrink its deficits), Washington stepped on the gas to boost them. Consequently, the United States functioned like a giant vacuum cleaner, sucking in massive net exports from Germany, Japan and, later, China. However, what gave that era (1980-2008) its energy and character was the manner in which the United States paid for its expanding deficits: by means of a tsunami of other people’s money (European, Japanese and Chinese net exporters’ profits) rushing into Wall Street in search of higher returns.

But for Wall Street to act as this magnet of other people’s capital, there were two prerequisites. One was Wall Street’s unshackling from New Deal-era regulations. Bank deregulation was central in this audacious reversal: From recycling Amercian surpluses, via transferring them to Europe and to Japan, the United States was now recycling the supluses of the rest of the world rushing into Wall Street, completing the loop necessary to pay for America’s deficits and keep globalization in rude health.

The second condition was the cheapening of American labour and the substitution of growing wages with escalating credit, provided via Wall Street. This cheapening of American labour was essential to helping push Wall Street’s capital returns above those of Frankfurt and Tokyo, where competitiveness was based instead on enhancements to productivity.

Through it all, neoliberalism emerged from the margins of political economics to dominate our discourse after the end of Bretton Woods. But it was nothing more than the sermon that steadied the hand of politicians repealing New Deal-era protections for workers and society at large from the motivated abuses of Wall Street bankers and predators such as Wal-Mart.

In summary, what we now call globalization was the result of a brave new financialized global recycling mechanism of immense energy and ever-increasing imbalances – with the rise of neoliberalism, wholesale bank deregulation and Wall Street’s “greed is good” culture as its mere symptoms. Before long, the Soviet Union and its satellites collapsed, with the new rulers keen for a piece of the action and the Chinese Communist Party determined to survive by staging a managed insertion of China’s workers into capitalism’s proletariat.

Financial capital’s inexorable march and two billion workers entering the global labour market ensured a stupendous redistribution of income and wealth. While billions of people were lifted from abject poverty in Asia, large swaths of Western workers were discarded, their voices drowned out by the cacophony of money-making in financialization’s epicentres.

Sept. 26, 2008: Pedestrians cross the intersection of Bay and King streets in Toronto’s financial district. In 2008, a financial crisis began to close globalization in a steel trap of its own making.

Globalization’s impasse, parochialism’s revenge

“Speculators may do no harm,” John Maynard Keynes once hypothesized, “as bubbles on a steady stream of enterprise. But the position is serious when enterprise becomes the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation.” Which is precisely what had happened by 2007: Atop the tsunami of European and Asian profits rushing into Wall Street, bankers built oversized bubbles of exotic forms of private debt that, at some point, acquired the properties of private money.

When these bubbles burst in 2008, the recycling loop sustaining globalization was broken – despite energetic money printing by central banks and the Chinese government’s breathtaking credit and investment spree. U.S. deficits, even after returning to their pre-2007 levels, could no longer stabilize globalization. The reason? Socialist largesse for the few – plus ruthless market forces for the many – damaged aggregate demand, repressed entrepreneurs’ sales expectations, restricted investment in productive jobs, diminished earnings for the many and, presto, confirmed the entrepreneurs’ pessimism. Adding more liquidity to such a mix makes not an iota of difference, as the problem is not a dearth of liquidity but a dearth of demand.

Wall Street, Wal-Mart and walled citizens – those were globalization’s symbolic foundations. Today, all three have become a drag on it. Banks are failing to maintain the capital movements that globalization used to reply upon, as total financial movements across the globe are less than a fourth of what they were in early 2007. Wal-Mart, whose ideology of cheapness symbolized the devaluation of labour and the gutting of traditional local businesses, is itself being squeezed by the Amazon model, whose ultimate effect is a further shrinking of overall spending. And the walls that were the nasty underbelly of the “global village” are now a source of political discontent, exposing the absurdity of a system that promotes the free movement of money and trucks while people remain fenced in.

Looking at the world from an Archimedean distance, globalization has been caught in a steel trap of its own making. Its crisis is due to too much money in the wrong hands. Humanity’s accumulated savings per capita are at the highest level in history. However, our investment levels (especially in the things humanity needs, such as green energy) are particularly low. In the United States, massive sums are accumulating in the accounts of companies and people with no use for them, while those without prospects or good jobs are immersed in mountains of debt. In China, savings approaching half of all income sit side by side with the largest credit bubble imaginable. Europe is even worse: There are countries with gigantic trade surpluses but nowhere to invest them domestically (Germany and the Netherlands), countries with deficits and no capacity to invest in badly needed labour and capital (Italy, Spain, Greece) and a euro zone unable to mediate between the two types of countries because it lacks the federal-like institutions that could do this.

And if these discontents were not enough, there is also the rise of the machines. By 2020, almost half the professions in Europe and North America will be susceptible to automation. Robots require a few highly paid designers and operators but may replace millions. This generates labour shortages and labour gluts in the same city at the same time. The middle class is in for another hollowing out, wage inequality is about to rise again in the richer countries, while developing countries will soon realize that having large young populations offers no respite from poverty: With robots getting smarter and cheaper, deglobalization takes over, and countries such as Nigeria, the Philippines and South Africa will bear the brunt of relocalization (especially with the evolution of 3-D printing).

Is it any wonder that parochialism, nativism and xenophobia are rearing their ugly heads everywhere? Rather than focusing on the role of Facebook, Russia or some unexplained, newfangled fear of the “foreigner,” the so-called liberal establishment (which is neither liberal nor particularly well-established, judging by recent electoral results in Europe and the United States) should look instead at globalization’s rotting foundations, which render it unsustainable.

But if globalization is no longer viable, what’s next? The answer offered by the so-called alt-right, the xenophobes and those who invest in militant parochialism is clear: Return to the bosom of the nation-state, surround yourselves with electrified fences and cut deals between the newly walled realms on the basis of national interest and relative brute strength. The fact that this nightmare is presented as a dream is yet another failure of globalization: Mr. Trump is a symptom of Barack Obama’s failure to live up to the expectations he had cultivated among the victims of globalization and its 2008 spasm.

Nov. 12, 2016: Days after Donald Trump’s election to the U.S. presidency, Nigel Farage – the British politician who helped champion the Brexit movement to withdraw from the European Union – posts this selfie to Twitter of his visit to Trump Tower in New York.@NIGEL_FARAGE/TWITTER

Nov. 12, 2016: Days after Donald Trump’s election to the U.S. presidency, Nigel Farage – the British politician who helped champion the Brexit movement to withdraw from the European Union – posts this selfie to Twitter of his visit to Trump Tower in New York.@NIGEL_FARAGE/TWITTERLest we forget, our problems are global. Like climate change, they demand local action but also a level of international co-operation not seen since Bretton Woods. Neither North America nor Europe nor China can solve them in isolation or even via trade deals. Nothing short of a new Bretton Woods system can deal with tax injustice, the dearth of good jobs, wage stagnation, public and personal debt, low investment in things we desperately need, too much spending on things that are bad for us, increasing depravity in a world awash with cash, robots that are marginalizing an increasing section of our work forces, prohibitively expensive education that the many need to compete with the robots, etc. National solutions, to be implemented under the deception of “getting our country back” and behind strengthened border fences, are bound to yield further discontent, as they enable our oligarchs-without-borders to strike trade agreements that condemn the many to a race to the bottom while securing their loot in offshore havens.

Our solutions, therefore, must be global, too. But to be so, they must undermine at once globalization and parochialism – both the right of capital to move about unimpeded and the fences that stop people and commodities from moving about the planet. In short, our solutions must be internationalist. And the goals of an International New Deal are pressing.

First, we need higher wages everywhere, supported by trade agreements and conditions that prevent the Uberization of waged labour domestically.

Tax havens are crying out for international harmonization, including a simple commitment to deny companies registered in offshore tax havens legal protection of their property rights.

We desperately need a green-energy union focusing on common environmental standards, with the active support of public investment and central banks.

We should create a New Bretton Woods system that recalibrates our financial infrastructure, with one umbrella digital currency in which all trade is denominated in a manner that curtails destabilizing trade surpluses and deficits.

And we need a universal basic dividend that would be administered by the New Bretton Woods institutions and funded by a percentage of big tech shares deposited in a world wealth fund.

The financial genie needs to be put back in its bottle, with capital controls domestically and globally to be imposed by co-ordinated action in the Americas, Europe and Asia. Money must be democratized and internationally managed in a manner that shrinks both trade deficits and surpluses. The robots must become humanity’s slaves, a feat that requires common ownership, at least partly.

All this sounds utopian. But no more so than the idea that the globalization of the 1990s can be maintained in the 21st century or replaced profitably for the majority by a revived nationalism.

Who should pursue this internationalist agenda? Progressives from Europe and North America have a duty to start the ball rolling, courtesy of our collective failure to civilize capitalism. I have no doubt that if we embark upon this path, others in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa will soon join us. At DiEM25, the Democracy in Europe Movement that I proudly co-founded, we take this duty seriously. We are determined to take this agenda, which we refer to as the European New Deal, to voters across the continent in the May, 2019, European Parliament elections. With globalization in retreat and militant parochialism on the rise, we have a moral and political duty to do so.

For the Globe & Mail site click here.

January 12, 2018

Αποχαιρετώντας τον κ. Ντάιζελμπλουμ – συνέντευξη στoν Νίκο Στραβελάκη REAL FM

January 5, 2018

Με την ματιά στο 2018: Ραδιοφωνικό μήνυμα από το DiEM25

Το 2017 άφησε την Ελλάδα φτωχότερη και πιο συμβιβασμένη με την κρίση και την ερημοποίηση, μέσα σε μια Ευρώπη ανίκανη να αντιδράσει στην αποδόμηση και απαξίωσή της.

Το 2018 προμηνύεται η χρονιά που τρόικα και ολιγαρχία θα προσπαθήσουν να μονιμοποιήσουν και νομιμοποιήσουν τη χρεοδουλοπαροικία, τη μνημονιακή Ελλάδα, προσποιούμενοι το τέλος των μνημονίων, την ώρα που αλυσοδένουν τη χώρα στη μνημονιακή πρακτική για τα επόμενα 60 χρόνια.

Το 2018 στην Ευρώπη θα είναι άλλη μια χρονιά παράλυσης, άλλη μια χαμένη χρονιά, στο όνομα των μεγάλων αλλαγών που απαιτούνται ώστε η Ευρώπη να γίνει πηγή λύσεων, αντί για πηγή κρίσεων, δε θα γίνει απολύτως τίποτα πάλι, πέρα από τις γνωστές, ανούσιες, διακοσμητικές εξαγγελίες.

Αν το 2018 μας βρει απαθείς, αν οι πολίτες, όλοι εμείς, δεν αντιδράσουμε, η Ελλάδα θα συνεχίσει να ερημοποιείται, να ασφυκτιά σε μια Ευρώπη που αποδομείται.

Γι αυτό, το Κίνημά μας για τη Δημοκρατία και την Κοινωνική Απελευθέρωση στην Ευρώπη και βέβαια στην Ελλάδα, βάζει μεγάλους στόχους για το 2018.

Δρομολογούμε τη ρήξη με την κρίση της Ευρώπης, δρομολογούμε τη ρήξη με την κρίση της Ελλάδας.

Πριν καλά καλά μπει η άνοιξη, στα τέλη Μαρτίου, θα γίνει η ιδρυτική συνδιάσκεψη του ελληνικού κόμματος του DiEM25, του οποίου το όνομα και μανιφέστο θα έχει ανακοινωθεί στα τέλη Φεβρουαρίου. Παράλληλα, το DiEM25 δημιουργεί κομματικούς μηχανισμούς στη Γαλλία, Ιταλία, Δανία,Γερμανία, Πολωνία, Σλοβακία, Ολλανδία, Κροατία, με νέες χώρες να προστίθενται.

Έτσι, στα τέλη Μαίου με αρχές Ιουνίου θα είμαστε έτοιμοι να παρουσιάσουμε στην Αθήνα, το Βερολίνο, το Παρίσι, σε πρωτεύουσες της Ανατολής και της Δύσης, του Βορρά και του Νότου, το Πανευρωπαϊκό Κίνημα Ανυπάκουων Ευρωπαϊστών, που θα καταθέσει, για πρώτη φορά στην ευρωπαϊκή ιστορία, μία ατζέντα κοινωνικής και οικονομικής πολιτικής για όλη την Ευρώπη, που βεβαίως θα αποτελέσει τη βάση της καμπάνιας μας για τις ευρω-εκλογές του Μαίου του 2019 για το Ευρωπαϊκό Κοινοβούλιο.

Μια Νέα Προοδευτική Συμφωνία για την Ευρώπη, θα δοθεί στους Ευρωπαίους πολίτες, σε όλους τους ψηφοφόρους, ως εναλλακτική του τοξικού δόγματος της ΤΙΝΑ (του δόγματος ότι δεν υπάρχει εναλλακτική).

Το κόμμα μας, που θα είναι αναπόσπαστο μέρος του πανευρωπαϊκού μας διεθνιστικού κινήματος, θα έχει το 2018 μόνο 2 αντιπάλους: τη χρεοδουλοπαροικία της Ελλάδας και την αναξιοπρέπεια που αυτή δημιουργεί, και τον καναπέ, που καθηλώνει δημοκράτες, πολιτικοποιημένους Έλληνες κι Ελληνίδες, που έχουν απηυδήσει με το πολιτικό μας σύστημα.

Το 2018 θα καταθέσουμε, θα δώσουμε την εναλλακτική που τρόικα εσωτερικού και εξωτερικού, μαζί με το κατεστημένο πολιτικό σύστημα, αρνουνται ότι υπάρχει, και θα αφήσουμε το λαό μας να αποφασίσει. Αυτή είναι η άγρια ομορφιά της δημοκρατίας και του πολιτικού πολιτισμού. Χωρίς πάθη, χωρίς θυμό αλλά με την έφεση για μια εθνική και πανευρωπαϊκή συμφιλίωση στη βάση του Ορθολογισμού και του Ανθρωπισμού.

Χρόνια πολλά σε όλους, φίλους, αντιπάλους και ιδίως στους κριτικά ιστάμενους!

Γιάνης Βαρουφάκης – DiEM25

January 4, 2018

A Good German Idea for 2018 – Project Syndicate op-ed, 4 JAN 2018

January 2, 2018

Varoufakis: “No se engañen, la crisis sigue ahí: el euro corre peligro” – El Pais, 2/1/2018

Yanis Varoufakis, exministro de Finanzas de Grecia. Barcelona, 9 de noviembre de 2017 ALBERT GARCIA

Yanis Varoufakis, exministro de Finanzas de Grecia. Barcelona, 9 de noviembre de 2017 ALBERT GARCIAPolémico. Atractivo. Brillante. Controvertido. Los seis meses de Yanis Varoufakis(Atenas, 1961) al frente del Ministerio de Finanzas de Grecia lo convirtieron en una celebridad global, en una suerte de estrella del rock de la política económica. Sus detractores lo caricaturizan como un extremista medio chiflado de izquierdas —según su propia definición—, enamorado de las motos potentes, de los restaurantes chic, de las chaquetas de cuero y del glamour de las islas griegas. La troika afirma que su gestión le costó a Grecia 100.000 millones de euros.

Lo más suave que dicen sus críticos es que se trata de un intelectual cuya inmersión en la política, más allá de la fama, puede calificarse como mediocre. Varoufakis acaba de responder a sus censores con un ejercicio de funambulismo literario: Comportarse como adultos, que en España acaba de publicar Deusto, ofrece una mirada única a las entretelas de Bruselas y es, sin duda, uno de los libros del año. A lo largo de 700 suculentas páginas se explica, asume algunos errores y, sobre todo, salda cuentas pendientes con una prosa de gran altura que incluye sonoros disparos a diestro y siniestro. El exministro conserva una lengua venenosa y es dueño de un análisis demoledor para Europa. “No se engañen, la crisis sigue ahí; el euro corre peligro”, embiste en una entrevista realizada con este periódico.

Europa crece a un ritmo superior al 2%. El paro ha bajado de la cota del 9%. Los déficits mejoran. Los populismos acechan, pero de momento siguen quedándose a las puertas de llegar al Gobierno en los grandes países. Las instituciones europeas presumen, en fin, de recuperación. Sin embargo, Varoufakis desdeña todo eso —“Una reactivación cíclica”, lo llama— y brinda un mal dato por cada dato bueno. Y, sobre todo, esboza un relato mucho menos complaciente que el de las élites de la UE.

“En la fase más aguda de la crisis del euro, hubo serios riesgos de fragmentación. El BCE supo contenerlos, pero las amenazas aún existen, aunque adopten otras formas: el Brexit, una Alemania que no logra formar Gobierno, la extrema derecha en Austria, Cataluña, el hundimiento del bipartidismo en Francia y los reflejos autoritarios en Europa del Este son claros síntomas de un malestar profundo. Las grandes crisis son momentos de revelación de las fallas del sistema: en Europa le hemos visto las costuras al euro y si nada cambia la amenaza es el hundimiento gradual de lo que solíamos llamar democracia liberal”.

Una situación como la de 2001

¿Lo peor ha pasado? No. Varoufakis, que ha fundado un nuevo partido (DiEM 25) para luchar contra ese malestar, se ríe cuando se le recuerda que el apocalipsis casi siempre defrauda a sus profetas: “Los análisis más pesimistas, entre ellos los míos, no han fallado en los últimos años; lo siento, pero es así”. ¿Lo peor ha pasado, al menos? “La situación actual me recuerda a la de 2001: veníamos de veinte años de encadenar burbujas, estalló la de las puntocom, y aun así nos las arreglamos para seguir igual y provocamos una crisis aún más grave con una burbuja aún mayor que estalló en 2008. Corremos el riesgo de volver a las andadas. En España, la deuda total va al alza. En Italia hay fuga de capitales, una crisis bancaria en ciernes, una situación política explosiva. Lo que tenemos en Grecia no puede llamarse recuperación, y la deuda es impagable. Los ejemplos son inagotables. En toda la periferia hemos cambiado empleos a tiempo completo por trabajos precarios, y con ello se ponen en peligro las pensiones futuras y las bases de la economía europea. Los desequilibrios financieros y macroeconómicos no solo no se han reducido, sino que son incluso mayores: me temo que no estamos para celebraciones. El euro, tal como está hoy, es insostenible”.

“Lo más preocupante”, acaba el griego, “es el bajo nivel de inversión y las divergencias crecientes en la zona euro. Sin inversión y sin convergencia es imposible hablar de fin de la crisis. Europa sigue metida en una: 10 años después de [la caída de] Lehman Brothers, somos incapaces de reforzar la arquitectura del euro y la moneda, contra lo que decían sus impulsores, es una fuente de incertidumbre. Europa es muy rica y puede mantener ese euro con pies de barro durante un tiempo, pero a la larga, créame, las costuras saltarán”.

Errores y maldiciones. Varoufakis se retrata a sí mismo como una suerte de héroe trágico en su libro. Alude a algunos de los errores que cometió como miembro del Gobierno de Alexis Tsipras, aunque su capacidad de autocrítica no está a la altura de su talento literario. Y aun así merece la pena prestar atención a su análisis. “Grecia no podía aceptar ningún acuerdo sin reestructurar su deuda, que era y es insostenible. Pero a los acreedores no les interesaba que pagáramos: simplemente querían dar una lección a Grecia como aviso a otros países. Al final, desgraciadamente, Tsipras capituló. En el póquer, si tienes malas cartas, solo tienes una posibilidad de ganar si tu farol es creíble y lo mantienes hasta el final, pero si crees que el oponente no va a retirarse no deberías jugar. Estoy orgulloso del auténtico susto, aunque breve, que se llevó la troika. Pero no supimos resistir”. “Nuestra derrota tuvo unos costes enormes”, admite en el libro. “Maldigo a mi Gobierno por no haber resistido”, añade durante la conversación.

Guindos: “Es uno de ellos”. Varoufakis critica con suma dureza a la Comisión Europea —“El Eurogrupo y hasta el grupo de trabajo del Eurogrupo mandan mucho más”—. Atiza sin miramientos a Tsipras, a Jean-Claude Juncker, a Pierre Moscovici, a Jeroen Dijsselbloem, a muchos otros. A lo largo de Comportarse como adultos apenas salva al ministro alemán Wolfgang Schäuble, que llegó a proponer la salida de Grecia del euro. Su análisis sobre Luis de Guindos está plagado de claroscuros: “Hablamos el mismo idioma porque Guindos, a diferencia de la gran mayoría del Eurogrupo, sabe de economía. Tuvimos interesantes discusiones, y a puerta cerrada estábamos más o menos de acuerdo. Pero en las reuniones Luis mantuvo posiciones indignantes: su primer objetivo era castigar a Grecia para penalizar a Podemos. Y siempre era el primero en darle la razón a Schäuble. Con él me pasó lo que con tantos otros: podía llegar a posiciones comunes en privado, pero a la hora de la verdad no servían de nada: eso es democráticamente deshonesto”. ¿Le ve con opciones al BCE? “Viene de la banca de inversión, como Mario Draghi. Tiene buenos fundamentos económicos. Y lo más importante: es uno de ellos”, remacha el exministro.

Egos revueltos. Varoufakis explica de forma pormenorizada en su nuevo libro qué significa ser uno de ellos a través de una conversación con el influyente Larry Summers, exasesor de Barack Obama y exsecretario del Tesoro con Bill Clinton. “Hay dos clases de políticos: los que ven las cosas desde dentro y los que prefieren quedarse fuera, los que prefieren ser libres para contar su versión de la verdad. El precio que pagan por su libertad es que los que están dentro, los que toman las decisiones importantes, no les prestan la menor atención. Los que viven las cosas desde dentro deben acatar una ley sacrosanta: no ponerse en contra de los que están dentro, no contar lo que sucede. ¿Cuál de los dos eres tú?”, le pregunta Summers. Varoufakis lo deja claro a lo largo de más de 700 páginas. Graba y transcribe reuniones, cuenta pormenores de decenas de entrevistas con líderes mundiales, pone sobre la mesa hasta el último y sonrojante detalle.

Yanis Varoufakis consigue reírse de sí mismo, aunque se las arregla para quedar bien casi siempre. Y mantiene el pulso literario de un volumen largo que tiene hechuras de novela negra y de drama shakespeariano. Pero sobre todo de tragedia griega. Porque a pesar de sus torrenciales explicaciones, el lector no alcanza a explicarse cómo Tsipras, Varoufakis y los suyos no consiguieron ni acercarse a lo único que importa: el mejor acuerdo posible para Grecia.

MARIO DRAGHI, EL “DÉSPOTA TRÁGICO”

Varoufakis nunca quiso salir del euro: su posición fue reclamar una reestructuración de la deuda pública griega (en torno al 180% del PIB: un nivel “insostenible”, según el FMI) y objetivos fiscales asumibles. Su estrategia era amenazar con un impago, y tener listo un sistema de liquidez alternativo si (como sucedió) los acreedores provocaban un cierre de los bancos.

En el momento clave, junio de 2015, el primer ministro, Alexis Tsipras, se echó atrás, y el BCE precipitó el final del drama. Varoufakis carga con suma dureza contra el Eurobanco (“el banco central más politizado del mundo”) en su libro. Califica a Draghi como “déspota trágico”. Le acusa de forzar la mano con “vergonzosas amenazas”. “Los abusones culpan a sus víctimas. Los abusones listos consiguen que la culpabilidad de sus víctimas parezca evidente. […] El BCE demostró una habilidad especial en esta última técnica”, dispara el exministro. Draghi, según esa versión, le obligó a cerrar la banca y le forzó a aceptar más austeridad, en un país que ha recortado las pensiones varias veces, prohibido la negociación colectiva y donde solo el 8% de parados recibe algún subsidio.

Yanis Varoufakis's Blog

- Yanis Varoufakis's profile

- 2451 followers