Yanis Varoufakis's Blog, page 114

November 26, 2017

Adults in the Room – reviewed by C. Collier for Brave New Europe

“Researchers have an obligation to society to take positions on questions on which they have acquired professional competence,” says French economist Jean Tirole. But how does an academic do this when media are not, in Tirole’s words, his ‘natural habitat’?

Yanis Varoufakis, in his recent incarnation as visiting professor at the University of Texas, Austin’s School of Public Affairs, took more than a position. He became a politician. He doesn’t share Tirole’s constraints: “…my resignation of 6 June 2015 [as Greek finance minister] was due precisely to my peculiar commitment not to sign any agreement I could not defend as an economist, politician, an intellectual and as a Greek.”

The step into politics was a big one. But Greece, after 2008, was, and remains, in crisis. No country has a more acute sense of its own sovereignty and identity, as the troika of the Eurogroup (of finance ministers), the European Central Bank and the IMF were reminded in January 2015, when Syriza, the radical left party, took power, and the Greek public once again took to demonstrating in Syntagma Square.

“Adults in the Room” (a phrase coined by Christine Lagarde, managing director of the IMF) is Varoufakis’s highly personal account of his brief tenure as Greek finance minister: six months of negotiations between January and June 2015, during which time he initially had the backing of his prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, for a radical stance which held out the threat of leaving the euro, and a full Grexit, if the EU and the IMF didn’t agree to renegotiate the debt.

Friends who discussed the book in a reading group were divided: some were exasperated by the repetition as negotiations inched forward. Others saw it as an epic tale. Varoufakis is a skilled storyteller who allows the events to speak for themselves.

Meeting Jeroen Dijsselbloem, president of the Eurogroup and finance minister of the Netherlands, on 30th January, Varoufakis told him that there were only three options available (he recorded meetings on his phone):

“One was a third bailout to cover up the failure of the second [in March 2012], whose purpose was to cover up the failure of the first [(May 2010]. Another was the new deal for Greece I was proposing: a new type of agreement between the EU, the IMF and Greece, based on debt restructuring, that diminished our reliance on new debt and replaced an ineffective reform agenda with one that the people of Greece could own. The third option was mutually disadvantageous impasse.

You do not understand, Jeroen told me, his voice dripping with condescension. ‘The current programme must be completed or there is nothing else.’”

There is also Thomas Wieser, Dijsselbloem’s deputy, to take into account. As president of the working group of officials behind the Eurogroup meetings he was, in Varoufakis’s words, ‘the most powerful man in Brussels’. Wieser circulated an unsigned ‘non-paper’ (a nice Orwellian touch) which made it clear that Greece should expect to receive no money owed to it by the European Central Bank, nor any loans agreed under the previous government… but it was still expected to meet its debt obligations in full. There might be an extension of the existing bailout agreement, a temporary appeasement, “but this would be conditional upon Greece taking a ‘cooperative approach’”.

The hidden agenda, the obstacle that ultimately overpowered all Varoufakis’s proposals, however clever, was that the French and German banks, which had invested so heavily in Greece, would always be given priority. Their governments had invested too much political capital to allow otherwise.

No bailouts, no haircuts, no debt renegotiation.

We’re down to the roots of the ‘deep establishment’, beyond prime ministers or presidents, finance ministers, EU commissioners, the Eurogroup of ministers (Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker doesn’t even have a walk-on part), down to the level of a working group which, taking its lead from the two most powerful EU governments, sets the mood and calls the tune.

Varoufakis in his account of the 30th January meeting with Dijsselbloem uses the phrase, ‘an agenda which the Greek people must own’. Sovereignty is not an issue he addresses directly in ‘Adults in the Room’, but in his 2016 book, ‘And the Weak Suffer What They Must’ he argues that the dismantling of sovereignty could ultimately lead to the dismantling of Europe. Varoufakis is a passionate European: his Democracy in Europe Movement, launched in autumn 2015, focuses on a much more open exercise of power within the EU.

But even the closed structures of the EU can be overridden. When Prime Minister Tsipras loses faith in the Brussels negotiating process he begins direct discussions with Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, and is quickly impressed ‘by her diligence and mastery of the Greek programme’. They should, she suggests, sideline their finance ministers Wolfgang Schäuble (a supporter of Grexit) and Varoufakis. Their discussions led in July 2015 to a third bailout agreement.

As for other participants in the skirmishes, Christine Lagarde is let off lightly on a personal level, with her integrity and goodwill just about intact. But not the IMF itself, which backed the third bailout against its own better judgment. Emmanuel Macron as French economy minister is peripheral to the negotiations, but always supportive of Varoufakis.

There are many who argue that Varoufakis’s confrontational approach made the ultimate settlement between the Syriza government and the EU worse. And, had debt renegotiation been taken seriously by the EU, another issue would have come to the fore: how far Varoufakis and the Syriza government would have voluntarily accepted privatisations, cuts in pensions, labour reforms etc.

Varoufakis not only had to contend with practised stone-wallers and the deep establishment, he also had to deal with a press that portrayed him as a dilettante. To quote The Economist (25 March 2015):

‘Mr Varoufakis’ lifestyle … is embarrassingly close to that of the rich Greeks he castigates for avoiding taxes by stashing cash abroad …he lectures his euro-zone colleagues and shows little interest in the detail of reforms demanded by Greece’s creditors…. as a fellow professor puts it: “Unlike his predecessors Yanis isn’t interested in managing the economy. What he really enjoys is brinkmanship.”’

Varoufakis had a conversation in 2012 with Larry Summers (former US Treasury Secretary), who argued that there were “two kinds of politicians, insiders and outsiders. The outsiders prioritise their freedom to speak their version of the truth. The price of their freedom is that they are ignored by the insiders, who make the important decisions.” And the insiders? – they “never turn against other insiders and never talk to outsiders about what the insiders say and do.” Varoufakis replied to Summers that he would behave “like a natural insider for as long as it takes to get a viable agreement on the table.”

In the end Varoufakis never stood a chance. To be a fully accredited insider he would have had to accede to the insiders’ working methods and conclusions. The Syriza party were self-designated outsiders until their leader and prime minister brought them in. Tsipras to the surprise of many ultimately had the insider mentality. Varoufakis did not.

Economics for the Common Good, Princeton UP, 2017

For the original site click here. Christopher Collier, a former book publisher, writes on his blog www.zenpolitics.me about history, politics, and life in general, also penning the occasional poem.

Adults in the Room: My Battle with Europe’s Deep Establishment by Yanis Varoufakis, Bodley Head, 2017, ISBN: 978-1847924469

A Tale of Two Faltering Unions (UK and EU); and what DiEM25 proposes in response – Address at the Oxford Guild, Mansfield College, Oxford University, 28/11/2017 at 7.30pm

Yanis Varoufakis, co-founder of DiEM25 (Democracy in Europe Movement), former Minister of Finance for Greece and high profile economist, academic and writer, is speaking to The Oxford Guild from 7.30pm on Tuesday 28th November (8th wk) in Mansfield College’s Sir Joseph Hotung Auditorium in the newly opened Hands Building. He will be discussing the state of the European Union, of the United Kingdom, the political landscape globally and the political/economic/social agenda of DiEM25 across the EU and the UK. The event is in association with the Economics Society and is free and open to all.

A Tale of Two Faltering Unions (UK and EU) – Address at the Oxford Guild, Mansfield College, Oxford University, 28/11/2017 at 7.30pm

Yanis Varoufakis, co-founder of DiEM25 (Democracy in Europe Movement), former Minister of Finance for Greece and high profile economist, academic and writer, is speaking to The Oxford Guild from 7.30pm on Tuesday 28th November (8th wk) in Mansfield College’s Sir Joseph Hotung Auditorium in the newly opened Hands Building. He will be discussing fascinating topical issues including the state of the European Union, the political landscape globally moving forward, negotiating at the brink and threats to democracy. The event is in association with the Economics Society and is free and open to all.

November 25, 2017

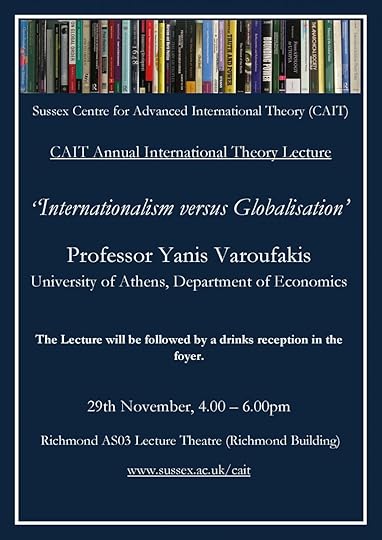

Internationalism vs Globalisation: Talk at Sussex University, 29th November 2017, 4pm

My ‘Talking to My Daughter About the Economy: A brief history of capitalism” reviewed by Ireland’s finance minister

On 4th November Ireland’s finance minister Paschal Donohoe took the trouble to review my ‘Talking to My Daughter About the Economy: A brief history of capitalism” for The Irish Times. To my utter surprise, he had some exceptionally complimentary things to say about my little book, for which I am – naturally – grateful.

“…a stimulating and elegant perspective on market economies

“…accessible but not simplistic”

In particular he refers to my chapter on banking as “superb” and describes my explanation of how debt works as “somewhat poetic”. Of course, serving as he does in a government that did its best to waterboard, block, even overthrow the government I represented in the Eurogroup (as Greece’s finance minister), Mr Donohoe had to qualify his praise of my book with damnation of my tenure as finance minister. By his account I was “out of my depth” in the Eurogroup and “fled for the Greek islands” when the going got tough – which must mean that, in the eyes of this tottering Irish government, a responsible, “in his depth”, Eurozone finance minister is one who does as the ECB dictates, signs on the dotted line of any loan agreement Berlin deems to be in its interests, and does not ever return home after resigning (Nb. My home, to which I “fled”, happens to be on a… Greek island).

The full book review follows below:

Seating plans are tricky matters. Family tensions, past loves and potential awkward silences complicate decisions.

However, if this is difficult for family weddings it has the potential to be utterly fraught when governments gather together. Family tiffs pale in comparison to the tension between adjacent prime ministers.

The European Union depends on such gatherings. Leaders of governments, ministers and diplomats gather regularly to thrash out issues. These occasions reach a crescendo after hours of talks, frequently late at night or early in the morning.

With so much going on, the seating plan is simple. Your location in the alphabet and whether your country hosts, or is about to host, the presidency of the European Union determine where you are physically located. Ireland is frequently located between Croatia and Greece.

This meant that Michael Noonan sat close to his Greek counterpart, Yanis Varoufakis, during some extraordinarily difficult meetings. Relations were difficult.

I therefore approached Talking to My Daughter About the Economy, Varoufakis’s new book, with some reservations.

Varoufakis may dazzle in the auditorium or in the many Irish festivals and debates in which he participates. However, he was hopelessly out of his depth as a finance minister. When the going got tough, he fled for the Greek islands. Despite this, or maybe because of this, he has continued to prosper as a writer and critic. The same cannot be said of those he was elected to serve.

My reservations grew with the author’s admission that he wrote this book in nine days “without a plan or provisional table of contents or blueprint to guide me”. This was, I thought, consistent with his time in government.

However, such misgivings were unfounded. True, the book is uneven, let down by threadbare conclusions. But the balance of this slim volume, penned to his teenaged daughter, is a stimulating and elegant perspective on market economies. It is accessible but not simplistic.

Nascent economies

Varoufakis begins his analysis by arguing that the ability to communicate, in addition to agricultural surpluses, spurred the development of the nation state and nascent economies. Gradually, societies that contained markets became market economies due to the increased role of capital (such as tools and factories) and the role of labour in producing goods.

This approach is used to understand the development of the Industrial Revolution in 18th-century Britain. Debt is central: “the rise of profit as a major incentive for people to do things came hand in hand with a new role for debt”.

Credit allows workers to be paid and raw materials and tools to be purchased before the entrepreneur is rewarded. It is the “primary factor and the essential lubricant of the production process”.

However, this primacy has darker consequences. The unmanageable growth of debt can also disrupt economies and ruin societies. The author argues that: “the instability that bankers create in market societies can be reduced but it can never be entirely eradicated for the simple reason that the economy is fuelled by the thing they provide: debt”.

A superb chapter on banking uses the metaphor of time travel to explain the role and dangers of banking in supporting entrepreneurship and economic growth. Other passages in the book draw on Star Trek, Frankenstein and Oedipus.

It feels forced at times, with the author working a bit too hard to wow the reader with the breadth of his cultural tastes. However, it works. Familiar concepts are examined through a fresh perspective.

A particular example of this is the analysis of the role of public debt. It is the “ghost in the machine” that allows market societies to function.

Rhythm of bond yields

As Minister for Finance, I review the performance of our government bonds every morning. The rhythm of bond yields, their rise and fall, provides the background music to many of the decisions that I make on behalf of our country and our people.

Maybe this is the reason I found the section on public debt somewhat poetic. Even if this dimension is not evident to other readers, the lucidity of the explanation will be.

During his tenure as minister for finance, Varoufakis demanded debt writedowns for Greece and Europe. This alleged solution makes a surprisingly brief appearance before he tackles the consequences of automation for labour and work.

The conclusions of this work are the most disappointing. A call to democratise the supply of money is baffling in its brevity. An exhortation for the creation of an “authentic democracy” and the collective ownership of technology and the means of production sits very poorly alongside his appreciation of entrepreneurship and individual initiative.

My utter disagreement here is to be expected. What might be less expected is my recommendation of this book. It is provocative and stylish. His abdication of responsibility might prove to be fruitful after all.

Paschal Donohoe is Ireland’s Minister for Finance and Public Expenditure and Reform. The above review appeared in The Irish Times – click here.

Discussing ‘Adults in the Room’, Europe & Trump on SALON TALKS

November 24, 2017

Europe, Greece, Trump & the need for American and European progressives to unite – in conversation with Nomi Konst on TYT

November 23, 2017

New York Times review of ‘Adults in the Rooom’, by Justin Fox

“Varoufakis wasn’t always trying to make waves. And he seems to have approached his chief task with great seriousness.”

Why the Greek Bailout Went So Wrong

by Justin Fox, New York Times, 17th November 2017 (Click here for the NYT site)

Short of leaving the euro, a move with no precedent or procedure and a high risk of cascading chaos, this was not an option for Greece. So in May 2010, the European Commission, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund stepped in with what was characterized as a 110 billion euro ($146 billion at the time) bailout.

[image error]It wasn’t so much a bailout of Greece, though, as of its lenders, notably the struggling big banks of France and Germany. Greece still owed an impossible amount of money, only now its main creditors were the “troika” of E.C., E.C.B. and I.M.F., which went on to impose harsh austerity measures. That austerity accelerated Greece’s economic decline, making repayment of its debts even less likely. More bailouts that weren’t exactly bailouts followed.

[image error]It wasn’t so much a bailout of Greece, though, as of its lenders, notably the struggling big banks of France and Germany. Greece still owed an impossible amount of money, only now its main creditors were the “troika” of E.C., E.C.B. and I.M.F., which went on to impose harsh austerity measures. That austerity accelerated Greece’s economic decline, making repayment of its debts even less likely. More bailouts that weren’t exactly bailouts followed.

“Fiscal waterboarding” is the name that the University of Athens economist Yanis Varoufakis gave to this process, after the torture method that simulates near-drowning again and again. And just as intelligence experts generally don’t think waterboarding is an effective way to extract information, it is hard to find an outside economic or financial expert who thinks the troika’s Greece policy has been effective or sensible.

So why has it continued? This is the most important question Varoufakis sets out to answer in this account of the six months he spent as Greece’s finance minister in 2015. “Adults in the Room” is several things: a gripping tale of an outspoken intellectual’s sudden immersion in high-stakes politics, an at times overwrought riposte to the many people in and outside Greece who derided his efforts and a solid work of explanatory economics. Most of all, though, it is an attempt to divine why smart, seemingly decent politicians and bureaucrats would continue pushing a pointlessly cruel approach long after its pointlessness had become clear. The book’s subtitle (“My Battle With the European and American Deep Establishment”) might lead a reader to expect all manner of sinister machinations. But while there are a few internal Greek political plots that can be fairly described as conspiracies, at the international level it’s mainly what Varoufakis calls “an authentic drama … reminiscent of a play by Aeschylus or Shakespeare in which powerful schemers end up caught in a trap of their own making.”

At the outset of the narrative, the former United States Treasury secretary Lawrence Summers asks Varoufakis in a dimly lit hotel bar in Washington, D.C., whether he is an “insider” or “outsider,” warning that outsiders (those who “prioritize their freedom to speak their version of the truth”) tend to have a hard time getting anything accomplished in government.

Varoufakis was and is obviously an outsider. He had made his name with colorful critiques of Greek and European economic policies. Even as he allied himself with Alexis Sipras and his leftist Syriza Party to run for office in January 2015, he didn’t actually join the party. And once in office he continued to behave in ways that finance ministers aren’t supposed to, tooling around Athens on his Yamaha XJR motorcycle and famously showing up for a meeting on Downing Street in a too-tight, too-bright blue shirt and a leather overcoat described by one British fashion writer as a “drug dealer’s coat.”

That bold fashion statement, Varoufakis recounts, was unintentional — the result of leaving his suitcase in a cab in Athens two days before. Arriving in Paris on a Saturday evening after most stores had closed, he had to make do with a couple of shirts from Zara and a coat borrowed from the Greek ambassador to France.

So Varoufakis wasn’t always trying to make waves. And he seems to have approached his chief task with great seriousness. He got Summers on his side, with the Harvard economist frequently emailing and calling with advice and information. Playing an even bigger role was Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia, who helped Varoufakis craft his debt restructuring proposals and accompanied him to meetings with European and I.M.F. officials. James Galbraith of the University of Texas, who had brought Varoufakis to Austin as a visiting professor, holed up at the finance ministry in Athens to develop contingency plans for a Greek exit from the euro. Other members of Varoufakis’s kitchen cabinet included the former chancellor of the Exchequer Norman Lamont (a Tory), the former Deutsche Bank chief economist Thomas Mayer and even, on occasion, the French economy minister (now president) Emmanuel Macron. This was no amateur hour. That the effort nonetheless ended in failure seems to have been only partly about that insider-outsider thing. A bigger obstacle was political deadlock in the country that now calls almost all the shots in Europe.

Varoufakis had hoped to engineer an orderly bankruptcy for Greece within the euro, with the country’s debts significantly reduced and austerity scaled back. Failing that, though, he was willing to pull Greece out of the euro and go the sovereign-debt-crisis route.

The German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble, the dominant figure in European financial affairs, openly favored the latter course. His harsh but not entirely unreasonable view was that it had been a mistake to let Greece into the eurozone, and that the only way forward was for Greece to leave. Chancellor Angela Merkel, on the other hand, was unwilling to contemplate a “Grexit” that might lead to an unraveling of the common currency. But she was also unwilling or unable to force Schäuble to offer a better deal to Greece. The result, as Varoufakis writes: “Stalemate!” Reinforcing the stalemate was what Varoufakis calls the “eurozone runaround,” the repeated protestations from officials at the E.C., E.C.B. and I.M.F. that, while they sympathized with Greece’s plight and agreed with many of Varoufakis’s recommendations, they alone couldn’t change the troika’s course. Jack Lew, then the United States Treasury secretary, similarly offered sympathetic words but made clear that he had no interest in crossing the Germans. The end finally came in July 2015, when — right after 61 percent of Greek voters decided to reject the latest “bailout” from the troika — a fearful Sipras chose nonetheless to submit. Varoufakis resigned after that.

Varoufakis does a magnificent job of evoking the absurdities and frustrations of his tenure. This is what it’s like to go from meeting to interminable meeting for six months, trying and failing to negotiate your country’s way out of a terrible impasse.

At least, this is what Varoufakis says it was like. I did wonder on occasion how much I could trust his play-by-play. I’m reviewing this book, not fact-checking it, but I couldn’t resist asking Summers for his assessment of the opening scene in the hotel bar. “Somewhat embellished,” was the verdict. Leaving aside whether Varoufakis’s recollections might be more accurate than those of a man who has met with so many embattled finance ministers over the past quarter century that he has probably lost count, I’m good with that. A truth somewhat embellished is still pretty much the truth.

Justin Fox is a columnist for Bloomberg View and the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

ADULTS IN THE ROOM

My Battle With the European and American Deep Establishment

By Yanis Varoufakis

550 pp. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. $28.

November 22, 2017

Yanis Varoufakis & James K. Galbraith on Democracy & DiEM25 (the Democracy in Europe Movement), in conversation with KUT’s Rebecca McInroy,

Listen to this insightful one hour-long discussion on democracy’s discontents in Europe and the United States between two economists who, in 2015, worked together to restore democracy in a small European country while helping its people escape debt-bondage. Here they discuss those events as well as the Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25) that is now taking the fight for democracy to every corner of Europe. [Click here for the podcast.]

Listen to this insightful one hour-long discussion on democracy’s discontents in Europe and the United States between two economists who, in 2015, worked together to restore democracy in a small European country while helping its people escape debt-bondage. Here they discuss those events as well as the Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25) that is now taking the fight for democracy to every corner of Europe. [Click here for the podcast.]

“Our enemy is apathy.” Yanis Varoufakis

In 2015 today’s guests were propelled onto the global stage by their efforts to take on the European banking establishment and restructure the Greek government’s financial system. For 5 months they worked to negotiate alternatives to further austerity measures; trying to extend loans while moving Greece toward a more solvent state.

Their efforts to confront the Eurozone and proceed democratically to carry out the wishes of the Greek people were ultimately defeated, but it was this battle lost that was the impetus of their current endeavor—to reform Europe and institute a transnational, pan-European democracy called DiEM25 –Democracy in Europe Movement.

Yanis Varoufakis is the former finance minister of Greece, author of Adults in the Room: My Battle With the European and American Deep Establishment, and co-founder of the DiEM25 –Democracy in Europe Movement.

James K. Galbraith is an eminent economist, an assistant to Mr. Varoufakis while he was the Greek finance minister, and he chronicled his time in Greece with the book Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice: The Destruction of Greece and the Future of Europe.

They were in Austin for a conference on Democratic Reform in Europe at the LBJ School for Public Affairs.

Yanis Varoufakis's Blog

- Yanis Varoufakis's profile

- 2452 followers