Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 81

June 14, 2017

What a Bet Shows, by Bryan Caplan

By this reasonable measure, how probative are bets? Taken individually, most bets are only marginally so. Even if one side offers 1000:1 odds and loses, this might only show that the loser was a fool to offer such great odds, not that his position on the underlying issue is flat wrong.

When we move from solitary bets to betting records, however, bets are telling indeed. A guy who wins one bet could easily have gotten lucky. But someone who wins 10 out of 10 bets - or, in my case, 14 out of 14 bets - almost certainly has superior knowledge and judgment. This is especially true if someone lives the Bettors' Oath by credibly promising to bet on (or retract) any public statement. A bet is a lot like a tennis match: one victory slightly raises the probability that the winner is the superior player, but it's entirely possible that he just got lucky. A betting record, in contrast, is a lot like a tennis ranking; people who win consistently against any challenger do so by skill, not luck.

After losing our unemployment bet, Tyler Cowen objected that betting:

...produces a celebratory mindset in the victor. That lowers theTyler's gets very close to the truth, but misses the most important lesson. Namely: In a busy world, ranking people by accuracy is not only helpful in the search for truth, but vital. No one has time to listen to more than a fraction of the armies of talking heads, or the memory to recall more than a fraction of their arguments. If we want to know the future as well as we're able, we need to identify people with good judgment - and ignore people with bad judgment. The first step, of course, is to unfollow pundits who refuse to put their money their mouths are. We should take them as seriously as self-proclaimed tennis "champions" who've never publicly played a match.

quality of dialogue and also introspection, just as political campaigns

lower the quality of various ideas -- too much emphasis on the candidates

and the competition.

(15 COMMENTS)

June 12, 2017

Immigration Charity at Work, by Bryan Caplan

Bryan:

Based entirely on following your blog and watching videos of your

debates, I became an open borders supporter and keenly concerned with

the plight of third-worlders being forcibly prevented from moving to the

first world.

As a Chicago-based attorney and law firm owner, I realized that I

could help by taking an asylum case pro bono. I received training and

support from the NIJC,

and represented a woman from Eritrea that was detained since last

winter in a county detention center in Southern Illinois. She was

tortured and imprisoned for reporting her superior officer for groping

her and preventing her from seeing her family, and this was after being

forced to serve in the national service for 7 years (i.e. indefinite

forced labor). I'm so glad she was able to escape.

I'm overjoyed to report that I very recently convinced an

immigration judge to grant her asylum. She was released immediately and,

as we speak, is journeying to Austin, Texas with the help of a refugee

not-for-profit.

I seriously doubt I would have had the energy or inclination to

take on such a case, pro bono, without coming in contact with your

writings and philosophy. Thanks for unwittingly convincing me to do so!

Best,

Isaac

(2 COMMENTS)

June 8, 2017

Balan on the Immigration Bet, by Bryan Caplan

I do agree that Bryan has won our bet. But I will commit the

following violation of the Bettor's Oath.

In the blog post that led to the bet, Bryan wrote:

The upshot: When I hear that Obama plans to shield

many millions of illegal immigrants from the nation's draconian

immigration laws, I'm skeptical. Such an action requires the very

iconoclasm the democratic process ruthlessly screens out. Bold

announcements notwithstanding, I expect him to (a) slash the numbers, (b) cave

in to public pressure, and/or (c) fail to effectively deliver what illegal

immigrants most crave - permission to legally work.

In the comments, where I accepted the bet, I wrote:

If you're offering, I'll take Nathaniel's side of

the bet too. I have no deep insight here, just my sense that Obama would have

nothing to gain from saying he's going to do this and then not doing it. If he

wasn't committed to seeing it through, he would have just skipped the whole

thing.

Bryan's reason for taking his side of the bet was that Obama would

not go through with a meaningful shielding of immigrants. My response was

that I didn't see why he would say it if he didn't plan to do it. What

ended up happening was that Obama lost in court, and we will never know what he

would have done if he had won. I didn't offer this as a caveat at the

time of the bet simply because I didn't think of it.

Bryan won fair and square; clearly these bets are decided based on

whether the specified events happened or not, not on the reasons. And

this is certainly not a claim that I was "really right." But the issue

did end up getting resolved on grounds that were (to a first approximation)

unrelated to, and offered no opportunity for the resolution of, the stated

basis of our disagreement.

If I lose my other

open bet about the price of gasoline in 2018, which I appear to be on track to

do, there will be no such caviling.

My reaction: I actually agree with Balan that Obama "wouldn't say it if he didn't plan to do it." But this neglects the crucial question: How much did he want to do it? In the grand scheme of Obama's political ambitions, what was its priority? If Obama cared about immigration half as much as I do, he would have made amnesty and liberalization his top issue in his first term when his party controlled both Houses of Congress. Instead, of course, he assigned pride of place to Obamacare.

(2 COMMENTS)

June 7, 2017

Unfortunately, I Win My Obama Immigration Bet, by Bryan Caplan

If, by June 1, 2017, the New York Times, Wall St. Journal, or Washington Post assert that one million of more additional illegalDavid Balan joined with Bechhofer, to the tune of $100.

immigrants have actually received permission to legally work in the

United States as a result of Obama's executive action since November,

2014, I owe Nathaniel Bechhofer $20. Otherwise he owes me $20.

By Bechhofer and Balan's mutual consent, I have now won. As is often the case, I wish I lost. And I think I would have lost if Obama had made immigration his top priority from the day he gained office. But I doubt it was even in his top 5. If Obama really cared about immigrants, he would have ended his presidency by pardoning the 20,000+ people in federal prison for immigration offenses, not closing the border to the victims of Cuban Communism.

(1 COMMENTS)

June 6, 2017

Mean Reversion and the Permanent Income Hypothesis: Suggested Answer, by Bryan Caplan

To review:Suppose you - and

you alone - discover that the stock market is mean-reverting.

True, False, and Explain: If you are rational, you will NOT obey the

permanent income hypothesis.

If the stock market is mean-reverting, low returns now predict high returns in the future, and high returns now predict low returns in the future.

If you obey the permanent income hypothesis, your current consumption depends solely on your total wealth (including future labor income, of course), not current income.

My answer: TRUE. As long as there are no binding credit constraints, mean reversion implies that after periods of exceptionally low or high

returns, the market valuation of your wealth is temporarily misleading.

When returns have been low, you can expect your wealth to grow

unusually quickly in the future; when returns have been high, you can

expect your wealth to grow unusually slowly in the future. The researcher who

correlates the market valuation of your total wealth with your current

consumption will therefore find that you are less responsive to stock

market changes than the PIH implies.

Intuitively, imagine that the

stock market fell 50% today, but you (and you alone) knew for sure it

would return to its initial price tomorrow morning. You'd have

near-zero reason to revise your consumption this evening, because you're

only poorer "on paper" - and you can readily borrow to resolve today's cash

flow problems.

What if there are binding credit constraints? Then there's another effect in the opposite direction. Key idea: Mean reversion implies unusually good investment opportunities after stock market falls. If you can't borrow unlimited amounts at the market rate, you will have to partially "self-finance" to take advantage of these temporarily good opportunities. As a result, your current consumption tends to be more responsive to stock market crashes than the PIH implies. During bad times, you'll want to really "tighten your belt" to take advantage of the situation.

In the real world, the relative size of these two effects is unclear - at least to me. But it would be a miracle if they exactly cancelled, leaving the PIH unscathed.

(5 COMMENTS)

June 5, 2017

Mean Reversion and the Permanent Income Hypothesis, by Bryan Caplan

Here's a question from my last Ph.D. Microeconomics exam. Post your answers in the comments, and I'll share my suggested answer tomorrow.

Suppose you - and

you alone - discover that the stock market is mean-reverting.

True, False, and Explain: If you are rational, you will NOT obey the

permanent income hypothesis.

(16 COMMENTS)

May 29, 2017

Cruise Ships and Private Plots, by Bryan Caplan

Think about it: On a cruise ship, people of all nations - and all skill levels - work together. Top-notch pilots and mechanics from Scandinavia ply their craft alongside cabin stewards and janitors from the Third World. Via comparative advantage, their cooperation allows them to provide an affordable, high-quality vacation to eager consumers.

So where's the stunting? Simple: This cosmopolitan cooperation is illegal on dry land. Resources therefore pour into the unregulated sector, creating a beautiful tourist experience. But that's nothing compared to what laissez-faire could accomplish.

By analogy: Remember the famous private plots of Soviet agriculture? The socialist government owned all the land... except for a tiny fraction in private hands. Yet this tiny fraction of private land produced a quarter to a third of Soviet foodstuffs! All the pent-up potential of Soviet farmers poured into the one legal outlet. Cruise ships work the same way: Immigration restrictions funnel labor into the one place where humans of all nations can legally work side-by-side. Loopholes in destructive policies are a good thing, but there's no substitute for repeal.

P.S. Here are my earlier thoughts on the economics and philosophy of cruising.

(2 COMMENTS)

May 25, 2017

Nationalism Is Not News, by Bryan Caplan

In 1960, Hayes followed up with a whole book - Nationalism: A Religion - cataloguing the ideology's global ubiquity. The work's full of gems like:"My country, right or wrong, my country!" Thus responds the faithful nationalist

to the magisterial call of his religion, and thereby he intends nothing dubious

or immoral. He is merely making a subtle distinction between governmental

officials who may go wrong and a nation which, from the inherent nature of

things, must ever be right. It would sound pedantic for him to say, "my nation,

indicatively right or subjunctively wrong (contrary to fact), my nation!"

Indeed, to the national state are now popularly ascribed infallibility and

impeccability. We moderns are prepared to grant that all our fellow countrymen

may individually err in conduct and judgement, but we are loath to admit

that our nation as a whole can make mistakes. We are willing to assail the

policies and even the characters of some of our politicians, but we are stopped

by the faith that is in us from doubting the Providential guidance of our

national state. This is the final mark of the religious nature of modern

nationalism.

The most impressive fact about the present age is the universality of the

religious aspects of nationalism. Not only in the United States does the

religious sense of the whole people find expression in nationalism, but also,

in slightly different form but perhaps to an even greater degree, in France,

England, Italy, Germany, Belgium, Holland, Russia, the Scandinavian and Baltic

countries, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, the

Balkans, Greece, and the Latin-American republics. Nor does the religion

of nationalism thrive only on traditionally Christian soil; it now flourishes

in Japan, Turkey, Egypt, India, Korea, and is rearing its altars in China.

Nationalism has a large number of particularly quarrelsome sects, but as

a whole it is the latest and nearest approach to a world-religion.

We need not here rehearse the epic story of World War I. It lasted over four years and turned out to be a supremely nationalistic war... As soon as war was declared, both masses and classes rallied to the support of their respective governments. Earlier professions of pacifism or neutrality quickly evaporated, and failure marked the movements and organizations which, it had been imagined, might check, if not exorcise, the war spirit. Christianity failed: no heed was given to pacific pleas of anguished pope or other priests and ministers. Marxian socialism failed: its following made no attempt to stay or impede the war by "general strike" or any other means. "Intellectuals" failed: the large majority of them deserted reason for emotion, fair-mindedness for bellicose partnership. So, too, failed "big business" and "international finance," and other economic considerations, which publicists such as Norman Angell had prophesied would militate against, and prevent, the enormous cost and ultimately universal bankruptcy that large-scale warfare would entail.Can't we accept the dominance of nationalism, but also admit that it's currently growing much stronger? We could, but we shouldn't. There's definitely a lot more media coverage of nationalism, but making a big deal out of everything is what the media does. Do I protest too much? Well, I've been blogging for a dozen years. Can you recall a single time where I claimed that current events were somehow "on my side"? I can't. Multi-decade trends mean something to me. So do the World Wars and the collapse of Communism. The rest is noise.

If you disagree - if you think you can see the global nationalist revival in the tea leaves - I am happy to bet you. Otherwise, turn off the news and read some Carlton Hayes.

(3 COMMENTS)

May 24, 2017

Trust Assimilation in the United States, by Bryan Caplan

One of the most-cited papers on this topic, Uslaner's "Where You Stand Depends Upon Where Your Grandparents Sat" (Public Opinion Quarterly, 2008) dissatisfies me in four ways: (1) despite the title, most of the reported effects of ancestry on trust were quite small; (2) the author's main specification uses dummy variables for national/regional origin, rather than a direct measure of trust in country/region of origin; (3) eight out of the nine countries/regions of origin were in Europe; (4) Uslaner includes multiple control variables that plausibly proxy trust, including whether you're "satisfied with your friendships" and agree that "officials are not interested in the average person," and that it's "not fair to bring a child into the world."

Algan and Cahuc's "Inherited Trust and Growth" (AER, 2010, Section II.B) does a much better job. It uses the World Values Survey to measure trust in "home countries," instead of just national/regional dummies, allowing a direct (though coarse) measure of immigrant assimilation. And it doesn't control for variables that are close proxies for trust. Result: About 45% of trust is persistent - not overwhelming, but hefty. Ultimately, though, Algan and Cahuc still dissatisfies me. Shortcomings: (1) they control for several variables that plausibly capture assimilation, especially education and income; (2) they heavily restrict their sample, (3) other than Africa, India, and Mexico, all of the countries/regions of origin they use are European.

So while I was hoping to outsource trust assimilation to prior researchers, I ultimately decided I needed to crunch the numbers myself. My approach closely mirrors Algan and Cahuc's: I use the General Social Survey to measure individuals' trust within the United States, and the World Values Survey to measure average national trust everywhere else. When multiple years of WVS data were available, I averaged them. When the two data sets' categories didn't perfectly mesh, I did the best with what I had. Example: Since the WVS doesn't include Austria, I gave Austrians the trust rate for Germany. I ended up with this:

GSS Code

Ethnic Origin

WVS Trust

GSS Code

Ethnic Origin

WVS Trust

1

AFRICA

15.4

22

PUERTO

RICO

14.2

2

AUSTRIA

35.3

23

RUSSIA

27.7

3

FRENCH

CANADA

38.9

24

SCOTLAND

29.5

4

OTHER

CANADA

38.9

25

SPAIN

25.8

5

CHINA

45.6

26

SWEDEN

62.8

6

CZECHOSLOVAKIA

26.9

27

SWITZERLAND

36.7

7

DENMARK

60.2

28

WEST

INDIES

3.5

8

ENGLAND

& WALES

29.5

29

OTHER

49.5

9

FINLAND

54.4

30

AMERICAN

INDIAN

--

10

FRANCE

18.7

31

INDIA

31.8

11

GERMANY

35.3

32

PORTUGAL

27.2

12

GREECE

20.1

33

LITHUANIA

27.2

13

HUNGARY

28.1

34

YUGOSLAVIA

20.1

14

IRELAND

29.5

35

RUMANIA

16.9

15

ITALY

28.3

36

BELGIUM

23.1

16

JAPAN

38.5

37

ARABIC

25.5

17

MEXICO

21.1

38

OTHER

SPANISH

14.9

18

NETHERLANDS

54.6

39

NON-SPAN

WINDIES

3.5

19

NORWAY

69.3

40

OTHER

ASIAN

24.3

20

PHILIPPINES

5.6

41

OTHER

EUROPEAN

26.4

21

POLAND

23.1

97

AMERICAN

ONLY

34.5

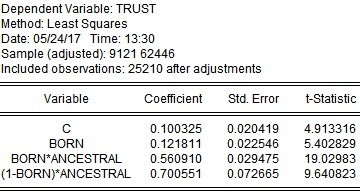

Since measuring assimilation is my goal, I include (a) a dummy variable for first-generation immigrants (BORN=0 if foreign-born, =1 if native-born), and (b) separate coefficients for assimilation for first-generation immigrants and their descendants. What do we get?

Using the entire sample:

Now remember: The formula for zero assimilation is TRUST = .00 + 1.00 * ANCESTRAL for foreign- and native-born alike. What the data yield, however, is TRUST = .10 + .70 * ANCESTRAL for foreign-born, and TRUST = .22 + .56 * ANCESTRAL for native-born. The upshot is that low-trust immigrants gain a lot of trust, especially after the first generation. Suppose your parents come from a country where only 10% of people trust others. Your parents' predicted trust in the U.S. is 17%, but yours is 28%, just 9 percentage-points below the U.S. average.

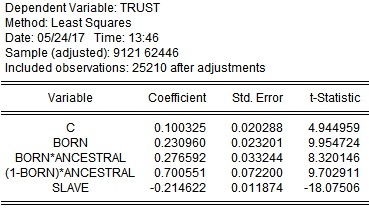

Now remember: The formula for zero assimilation is TRUST = .00 + 1.00 * ANCESTRAL for foreign- and native-born alike. What the data yield, however, is TRUST = .10 + .70 * ANCESTRAL for foreign-born, and TRUST = .22 + .56 * ANCESTRAL for native-born. The upshot is that low-trust immigrants gain a lot of trust, especially after the first generation. Suppose your parents come from a country where only 10% of people trust others. Your parents' predicted trust in the U.S. is 17%, but yours is 28%, just 9 percentage-points below the U.S. average. What happens if we distinguish voluntary immigrants from the descendants of slaves? Some prominent cliometricians argue that slavery durably damaged trust in Africa, and it's highly plausible that slavery in America did the same here. Given historic immigration patterns, virtually all native-born U.S. blacks descend from slaves, so I define the dummy variable SLAVE, where SLAVE=1 if (ETHNIC=1 and BORN=1). Then I re-estimate:

Now we see an extremely high rate of trust assimilation for descendants of voluntary immigrants, regardless of their origins: TRUST = .33 + .28 * ANCESTRAL. If your ancestral trust is 10%, your predicted trust in the U.S. is 36%, a mere 1 percentage-point below the U.S. average.

Now we see an extremely high rate of trust assimilation for descendants of voluntary immigrants, regardless of their origins: TRUST = .33 + .28 * ANCESTRAL. If your ancestral trust is 10%, your predicted trust in the U.S. is 36%, a mere 1 percentage-point below the U.S. average.I'm well-aware, of course, that these results aren't good enough for publication. I banged them out in a few hours. But I still think I learned a lot by getting my hands dirty in the data. The most important lesson: While scholarly claims about trust persistence aren't totally wrong, they're heavily exaggerated. Common sense says that descendants of voluntary immigrants readily assimilate to mainstream U.S. culture. And at least for trust, common sense is right.

(4 COMMENTS)

May 23, 2017

The Behavioral Econ of Paperwork, by Bryan Caplan

I'm not alone. Education researchers, for example, find that many students leave free money sitting on the table because they fail to fill out the proper forms. Furthermore, modest help with form completion markedly raises uptake. Some highlights:

Some students receiving college financial aid could be getting more. Others fail to qualify for aid entirely: each year, more than one million college students in the United States who are eligible for grant aid fail to complete the necessary forms to receive it. Bird and Castleman (2014) estimate that nearly 20 percent of annual Pell Grant recipients in good academic standing fail to refile a FAFSA after their freshman year, and subsequently miss out on financial aid for the following academic year.And:

Additionally, the complexity of the financial aid application confuses and deters students (ACSFA 2001, 2005). To determine eligibility, students and their families must fill out an eight-page, detailed application called the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which has over 100 questions. King (2004) estimates that 850,000 college students who were eligible for federal grant aid in 2000 did not complete the forms necessary to receive their benefitsSince I think education is extremely socially wasteful, I'm glad that so many students fail to game the system. But - as Robin Hanson pointed out at a seminar on this research - there's probably something much bigger at work. What researchers have learned about students and FAFSA is probably just a special case of the fact that humans hate filling out paperwork. As a result, objectively small paperwork costs plausibly have huge behavioral responses.*

Consider a few possible margins:

1. A small business-owner decides not to hire a worker because he doesn't want to fill out tax and other regulatory compliance forms.

2. A home-owner decides not to improve his home because he doesn't want to get the necessary permits and inspections.

3. A traveler decides not to visit a country because he doesn't feel like applying for a visa.

4. An unemployed worker (note the low opportunity cost!) doesn't apply for unemployment insurance because the process is aggravating.

5. A childless couple decides against adoption because the bureaucracy is hellish (or, in the case of international adoption, hellish squared).

Many people's knee-jerk reaction will be, "Let's cut red tape!" But the craftier response is, "Let's manipulate red tape." If X is good, we can noticeably encourage it by modestly simplifying the paperwork. So yes, cut red tape for employment, construction, travel, and adoption. If X is bad, though, we can noticeably discourage it by modestly complicating the paperwork. Indeed, complexity is a viable substitute for explicit means-testing: If you lack the patience to fill out ten forms, you probably don't really need the money.

* Of course, if someone fills out paperwork full-time, they might become

inured to the drudgery. But we'd still expect oversized behavioral effects

of paperwork for everyone who can't cheaply delegate such tasks to a trusted

professional.

(3 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers