Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 80

July 3, 2017

Hanson Underrates Democracy, by Bryan Caplan

3. When people think about changes they'd like in the world one of

their first thoughts, and one they return to often, is wanting more democracy.

It's their first knee-jerk agenda for China, North Korea, ISIS, and so on.

Surely with more democracy all the other problems would sort themselves out.

This is a baffling statement if you know the basic history of these three countries. While the effects of more democracy for contemporary China are at least debatable, dictatorship was clearly essential for a quarter-century of Maoist horrors, including the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. North Korea's dictatorship has an unbroken history of pursuing almost-certainly unpopular policies, beginning with the invasion of South Korea and culminating in mass starvation in the 90s to maintain the Kims' Communist dictatorship after the loss of Soviet subsidies. And ISIS is hated throughout the Muslim world; while free elections in Syria could easily elect authoritarian Islamists (indeed, fairly free elections already elected authoritarian Islamists in Iraq), they wouldn't sustain a totalitarian bloodbath.

But

in fact scholars can find few consistent difference in the outcomes of nations

that depend much on their degree of democracy. Democracy doesn't seem to cause

differences in wealth, or even in most specific policies. Democracies today war

a bit less, but in the past democracies warred more

than others. Democracies have less political repression, and our moral

spotlight finds that fact to be of endless fascination. But it is in fact a

relatively small effect on nations overall.

Robin strangely fails to mention domestic mass murder, which dictatorships essentially monopolize. And this outcome, more than any other, marks the hellish histories of Communist China, North Korea, and ISIS.

I'll happily agree that democracy has little systematic effect on economic growth - and that economic growth is the closest thing humanity has to a panacea. But if North Korea or ISIS were democracies, their true horrors would quickly cease. And if China had been a democracy since 1945, its true horrors never would have happened.

Nations

today have huge differences in outcomes, and we are starting to understand some

of them. But most of them have little to do with democracy. Plausibly larger

issues include urbanization, immigration, foreign trade, regulation, culture,

rule of law, corruption, suppression or encouragement of family clans or

religion, etc. If you want to help nations, you'll have to look outside the

moral spotlight on democracy.

Update: After I tweeted this post, Robin replied with refreshing forthrightness: "I accept your point; I had in mind less extreme variations, so North Korea was a poor choice on my part." In conversation, I learned that Robin and I were thinking of two different ISIS hypotheticals. I was picturing, "How would ISIS govern if it were a democracy?," and Robin was picturing, "If neighboring countries were democracies, how would they deal with ISIS?"

(5 COMMENTS)

June 29, 2017

What Is Resentment?, by Bryan Caplan

1. "Most leftists don't hate markets." I agree, but I never said that. You can be anti-X without hating X; indeed, this is normally true. When I say "The left is anti-market," I'm claiming that when left-leaning people think about markets, their primary emotion is the much milder one of resentment.

2. "Most leftists don't resent markets at all; we just have the following list of complaints about markets." This would be a fine response if the list of complaints were mild. It would be pretty convincing if the typical leftist accepted half of the popular complaints about markets, but eagerly denied the other half. And it would be a great criticism if the standard leftist view were, "Markets are awesome, but regulation and a safety net make them even more awesome." But attitudes in these ballparks are rare. One of my left-leaning friends approvingly quoted Bernie Sanders to show that even the Bern vocally appreciates markets:

A market economy is beneficial for productivity and economic freedom.But to my ears, Sanders words are resentment incarnate (and if there's video of the speech, I strongly suspect his facial expression is non-happy during this entire passage). These are all big complaints - and he clearly thinks the U.S. and other modern market economies instantiate them. His complaints look even bigger if you remember that modern market economies already have well-developed programs and regulations intended to address these concerns, but Bernie's still deeply dissatisfied. There's no sign that he rejects any popular complaint about markets; instead, he eagerly adopts whatever complaints he can get his hands on. And he certainly isn't saying his policies make markets "even more awesome"; instead, he's saying that markets without the added checks he favors are simply bad.

But if we let the quest for profits dominate society; if workers become

disposable cogs of the financial system; if vast inequalities of power

and wealth lead to marginalization of the poor and the powerless; then

the common good is squandered and the market economy fails us.

Not convinced? Picture anything you consider basically good, but less than perfect. Say, moms. What emotional state would you ascribe to a person who said...

Mothers are beneficial for gestation and care-taking. But if we let the quest for maternal pride dominate the family; if children become disposable cogs of the after-school activities system; if vast inequalities of power and desserts lead to marginalization of the young and powerless; then the common good is squandered and motherhood fails us.Frankly, this sounds like someone with dire Mommy Issues. Even if they insist they're not "anti-mom," neutral observers will understandably label them as such.

3. "Leftists aren't anti-market, because our complaints are justified." My Simplistic Theory isn't intended to judge whether any ideology is true or reasonable. When it says, "The right is anti-left," it doesn't mean, "The right is more anti-left than appropriate." Similarly, when it says, "The left is anti-market," it doesn't mean "The left is more anti-market than appropriate." In both cases, I'm simply stating that each side feels resentment for something. Describing the enduring commonalities of left and right is hard enough without trying to simultaneously evaluate the ideologies.

(15 COMMENTS)

June 28, 2017

Reply to Yudkowsky, by Bryan Caplan

Bryan Caplan's Simplistic Theory of Left and Right says "The Left is anti-market andI suspect there is some difference along these lines. But just as people on the Left will tend to object, "We're not anti-market, we're pro-X, Y, and Z," people on the Right will tend to object, "We're not anti-Left, we're pro-X, Y, and Z." In any case, my theory isn't intended to predict self-description, but to find enduring commonalities between these two global tribes - commonalities enduring enough to fit both tribes since they emerged about two centuries ago.

the Right is anti-Left". This theory is half wrong, and will for this

reason confuse the Left in particular. It ought to be a clue that if

you ask the Left whether they're anti-market, most of the Left will

answer, "Of course not," whereas if you ask the Right whether they're

anti-Left, they'll answer "Hell yes we are."

People may understandI never said "hate." "Resentment" is far more apt, though of course prominent subsets of these tribes let their resentment blossom into hate.

themselves poorly a lot of the time, but they often know what they hate.

My "Human Theory of the Left" is as follows: The Left holds markets to the same standards as human beings.

[...]

And that's what the

Left sees when they look at somebody being paid $8/hour... They see a judgment about how hard an employee works,

and how much they need and deserve.So of course they hate whatever looks at a poor starving mother and says "$8/hour". Who wouldn't?

Ask them and they'll *tell you*: They don't *hate* markets. They just

think that the prices and outcomes aren't fair, and that tribal action

is required for everyone to get together and decide that the prices and

outcomes should be fairer.

Again, I never said "hate." But this sounds like a clear case of resentment. So Eliezer's story ends up being a special case of mine.

Is it the correct special case of mine? I'm not convinced. Some leftists' primary complaint is that "prices and outcomes aren't fair." But few non-economists of any ideology talk about prices much (except, of course, to live their daily lives). If you revise Eliezer's statement to, "Leftists just think that market outcomes are unfair, and that tribal action

is required for everyone to get together and decide that the outcomes should be fairer," I'd still say you're oversimplifying. While leftists do routinely object to the market's unfairness, their complaints about the market are legion. Historically - and even today - plenty of leftists argue their policies are better for economic growth. Others decry materialism, the effects on the environment, or national solidarity. Left-leaning economists add in a laundry list of market inefficiencies: monopoly, externalities, asymmetric information, and so on.

If this post gets shared outside my

own feed, some people will be reading this and wondering why I

*wouldn't* want prices to be fair.And they'll suspect that I

must worship the Holy Market and believe *its* prices to be wise and

fair; and that if I object to any regulation it's because I want the

holy, wise and fair Market Price to be undisturbed.

While this is a complete misrepresentation of Eliezer's views, it's a pretty fair description of mine. I don't think market prices are "holy." But they are wise in the sense that they're signals wrapped up in incentives. And they're fair because they're based on mutual consent, and consent is one of most important determinants of fairness.

[...]

People like Bryan Caplan see people in 6000BC wearing animal skins as

the native state of affairs without the Market. People like Bryan keep

trying to explain how the Market got us away from that, hoping to foster

some good feelings about the Market that will lead people to maybe have

some respect for its $8/hour figure.If my Human Theory of the

Left is true, then this is exactly the wrong thing to say, and eternally

doomed to failure.

"Eternally doomed to failure"? Hailing the market's long-run effect on people's standard of living is probably the most successful economic argument of the last fifty years. It's clearly the main argument for pro-market reforms in China, and probably India as well. And it's also likely the most successful argument for privatization in the Soviet Bloc and deregulation in the West.

Personally, it's not my favorite argument. Like Mike Huemer , I'd rather argue from the moral presumption that individuals shouldn't threaten to attack other people for offering deals they don't like, and the moral truism that calling an organization a "government" doesn't lighten its moral obligations. If Eliezer called this argument "eternally doomed to failure," I'd still demur, but I freely admit that it hasn't been influential in the world of economic policy.

But don't try to tell them that the Market is good, or wise, or kind. They can see with their own eyes that's false.

Believing is seeing. There are solid reasons to think the Market is better, wiser, and kinder than alternatives. (What's "kind" about calling the cops because someone offers you a deal you don't like?) But if you have strong initial anti-market feelings, it's hard to give credit where credit is due.

Bottom line: Even if Eliezer's story is the whole truth, he accepts my Simplistic Theory of Left and Right. He's just filling in the details. But his story explains no more than a small sub-set of leftists. And they don't have a good point.

June 27, 2017

Yudkowsky on My Simplistic Theory of Left and Right, by Bryan Caplan

Bryan Caplan's Simplistic Theory of Left and Right says "The Left is anti-market and

the Right is anti-Left". This theory is half wrong, and will for this

reason confuse the Left in particular. It ought to be a clue that if

you ask the Left whether they're anti-market, most of the Left will

answer, "Of course not," whereas if you ask the Right whether they're

anti-Left, they'll answer "Hell yes we are." People may understand

themselves poorly a lot of the time, but they often know what they hate.

My "Human Theory of the Left" is as follows: The Left holds markets to the same standards as human beings.

Consider a small group of 50 people disconnected from the outside

world, as in the world where humans evolved. When you offer somebody

fifty carrots for an antelope haunch, that price carries with it a great

array of judgments and considerations, like whether that person has

done you any favors in the past, and how much effort it took them to

hunt the antelope, and how much effort it took you to gather the

carrots. If you offer them an unusually generous price, you'd expect

them to give good prices in return in the future. A low price is either

a status-lowering insult, or carries with it a judgment that the other

person already has lower status than you.

And that's what the

Left sees when they look at somebody being paid $8/hour. They don't see

a supply curve, or a demand curve; or a tautology that for every loaf

of bread bought there must be a loaf of bread sold, and therefore supply

is always and everywhere equal to demand; they don't see a price as the

input to the supply function and demand function which makes their

output be equal. They see a judgment about how hard an employee works,

and how much they need and deserve.

So of course they hate whatever looks at a poor starving mother and says "$8/hour". Who wouldn't?

Ask them and they'll *tell you*: They don't *hate* markets. They just

think that the prices and outcomes aren't fair, and that tribal action

is required for everyone to get together and decide that the prices and

outcomes should be fairer.

If this post gets shared outside my

own feed, some people will be reading this and wondering why I

*wouldn't* want prices to be fair.

And they'll suspect that I

must worship the Holy Market and believe *its* prices to be wise and

fair; and that if I object to any regulation it's because I want the

holy, wise and fair Market Price to be undisturbed.

This

incidentally is what your non-economist friends hear you saying whenever

you use the phrase "efficient markets". They think you are talking

about market prices being, maybe not fair, but the most efficient thing

for society; and they're wondering what you mean by "efficiency", and

who benefits from that, and whether it's worth it, and whether the goods

being produced by all this efficiency are actually flowing to the

people making $8/hour.

You reply, "What the hell that is not even

remotely anything the efficient markets hypothesis is talking about at

all, you're not even in the right genre of thoughts, the weak form of

the EMH says that the supply/demand-intersecting price for a

highly-liquid well-traded financial asset is a rational subjective

estimate of the expectation of its supply/demand-intersecting price two

years later taking into account all public information, because

otherwise it would be possible to pump money out of the predictable

price changes. The EMH is a descriptive statement about price changes

over time, not a normative statement about the relation of asset prices

to anything else in the outside world."

This is not a short paragraph in the standard human ontology.

"So you think that $8/hour wages are efficient?" they say.

"No," you reply, "that's just not remotely what the word efficient

*means at all*. The EMH is about price changes, not prices, and it has

nothing to do with this. But I do think that $8/hour is balancing the

supply function and the demand function for that kind of labor."

"And you think it's good for society for these functions to be balanced?" they inquire.

The one is willing to consider the force of the argument they think

they're hearing--that the market is a weird and foreign god which will

nonetheless bring us the right benefits if we make it the right

sacrifices. But, they respond, *is* the market god really bringing us

these benefits? Aren't some people getting shafted? Aren't some people

being sacrificed to save others, maybe a lot of people being sacrificed

to save a few others, and isn't that worth the tribe getting together

and deciding to change things?

And you clutch your hair and say,

"No, you don't get it, you know the market is doing something important

but you don't understand what that thing *is*, you think the markets are

like arteries carrying goods around and they can get blocked and starve

some tissues, and you want to perform surgery on the arteries to

unblock them, but actually THE MARKETS ARE RIBOSOMES AND YOU'RE TRYING

TO EDIT THE DNA CODE AND EVERYTHING WILL BREAK SIMULTANEOUSLY LIKE IT

DID IN VENEZUELA."

And what they hear you saying is "The markets

are wise, and their prices carry wisdom you knoweth not; do you have an

arm like the Lord, and can your voice thunder like His?"

Because,

they know in their bones, when a corporation pays an employee $8/hour,

it means something. It means something about the employer and it says

something about what the employer believes about the employee. And if

you say "WAIT DON'T MESS WITH THAT" there's a lot of things you might

mean that have short sentences in their ontology: you could mean that

you believe $8/hour is the fair price; you could mean you believe the

price is unfair but that it's worth throwing the employees under the bus

so that society keeps functioning; you could believe that maybe the

market knows something you don't.

And all of those things, one

way or another, are saying that you believe there's some virtue in that

$8/hour price, some virtue transmitted to it by the virtue you think is

present within the market that assigns it. And that's a cruel thing to

say to someone getting $8/hour, isn't it?

Just look at what the market does. How can you believe that it's wise, or right, or fair?

And they can't believe that you *don't* think that--even though you'll

very loudly tell them you don't think that--when you are being like "IF

YOU WANT THEM TO HAVE MORE MONEY THEN JUST GIVE THEM MONEY BUT FOR GOD'S

SAKE DON'T MESS WITH THE NUMBER THAT SAYS 8."

This by the way

is another example of why it's an important meta-conversational

principle to pay a lot of attention to what people say they believe and

want, and what they tell you they *don't* believe and want. And that if

nothing else should give you pause in saying that the Left is

anti-market when so many moderate leftists would immediately say "But

that's not what I believe!"

Maybe we'd have an easier time

explaining economics if we deleted every appearance of the words "price"

and "wage" and substituted "supply-demand equilibrator". A national

$15/hour minimum supply-demand equilibrator sounds a bit more dangerous,

doesn't it? Increase the Earned Income Tax Credit, or better yet use

hourly wage subsidies. Establish a land value tax and give the money to

poor people, while being careful not to establish new paperwork

requirements that exclude busy or struggling people and being careful

about phaseout thresholds. Or if you really insist on looking at things

in the simplest possible way, then take money away from rich people and

give it to poor people. It'll do less damage than messing with the

supply-demand equilibrators.

I feel like I'm at a banquet

watching people trying to eat the plates and they're like "No, no, I

understand what food does, you're just not familiar with the studies

showing that eating small amounts of ceramic doesn't hurt much" and I'm

like "If you knew what food does and what the plates do then you would

not be TRYING to eat the plates."

I honestly wonder if we'd have

better luck explaining economics if we used the metaphor of a terrifying

and incomprehensible alien deity that is kept barely contained by a

complicated and humanly meaningless ritual, and that if somebody upsets

the ritual prices then It will break loose and all the electrical plants

will simultaneously catch fire. Because that probably *is* the closest

translation of the math we believe into a native human ontology.

Want to help the bottom 30%? Don't scribble over the mad inscriptions

that are closest to them, trying to prettify the blood-drawn curves.

Mess with any other numbers than those, move money around in any other

way than that, because It is standing very near to them already.

People like Bryan Caplan see people in 6000BC wearing animal skins as

the native state of affairs without the Market. People like Bryan keep

trying to explain how the Market got us away from that, hoping to foster

some good feelings about the Market that will lead people to maybe have

some respect for its $8/hour figure.

If my Human Theory of the

Left is true, then this is exactly the wrong thing to say, and eternally

doomed to failure. To praise that which would offer $8/hour to a

struggling family, is directly an insult to that family, by the humanly

standard codes of honor. If you want people to leave the $8/hour price

alone, and you want to make the point about 6000BC, you could maybe try

saying, "And that's what Tekram does if you have no price rituals at

all."

But don't try to tell them that the Market is good, or wise, or kind. They can see with their own eyes that's false.

June 26, 2017

Boudreaux on the Progressive Mentality, by Bryan Caplan

As he so frequently does, Bryan here hits on its head an important nail solidly, cleanly, and with impressive force.I suspect that the single biggest factor that distinguishes

"Progressives" from libertarians and free-market conservatives is the

simple fact that "Progressives" do not begin to grasp the reality of

spontaneous order. "Progressives" seem unable to appreciate the reality

that productive and complex economic and social orders not only can,

but do, emerge unplanned from the countless local decisions of

individuals each pursuing his or her own individual plans. Therefore,

"Progressives" naturally adopt a creationist view of society and of the

economy: without a conscious and visible (and well-intentioned) guiding

hand, society and the economy cannot possibly work very well. Indeed,

it seems that for many (most?) "Progressives," the idea that a

spontaneously ordered economy can work better than one directed

consciously from above - or, indeed, that a spontaneously ordered

economy can work at all - is so absurd that when "Progressives"

encounter people who oppose "Progressive" schemes for regulating the

economy, "Progressives" instantly and with great confidence conclude

that their opponents are either stupid or, more often, evil cronies for

the rich and the powerful.

Don tells an interesting story, and he's probably true in some cases. But ultimately, I think resentment of markets has little to do with incomprehension of "spontaneous order." Key point: As Hayek emphasizes, markets are only one form of spontaneous order. Others include language, science, fashion, manners, and even informal hiking paths. In each case, individuals pursue their own plans with no central direction, yet a tolerably well-functioning social order emerges. And leftists rarely express resentment - or even worries - about the social value of any of these. So how can spontaneous order be the crux of the issue?

My preferred story is much simpler: Leftists look at the world of business and see greedy people leading and prospering. This upsets people of almost every ideology if they dwell on it. On an emotional level, human beings want people with noble intentions in charge. Who then are leftists? They're the sub-set of humans who feel these emotions with exceptional intensity and durability - and accept a group identity that reinforces such emotions. Why is a power-hungry politician who bullies strangers with big plans and pompous speeches more "nobly intentioned" than a greedy businessman who woos strangers with fine wares and low prices? I don't know, but clearly I'm in the minority here.

Well, at least I'm in good company.

To sell war, you've got to convince people that its non-obvious,

distant consequences are positively fantastic. Contra Bastiat, though,

it's ridiculously easy to convince them of this. If you tell people

that the skies will fall if their country doesn't fight, they believe it

- even though the worst case scenario is usually the loss of some

territory most people can't even find on a map.

My best explanation is that Bastiat's seen/unseen fallacy is not a general psychological tendency. Instead, it's an expression of anti-market bias:

Since people dislike markets, they're quick to dismiss claims about

their hidden benefits. When people are favorably predisposed to an

institution, however, they're quite open to the possibility that it's

better than it looks to the naked eye. Government's a good example, but

so are religion, medicine, and education.

(12 COMMENTS)

June 22, 2017

Progressive/Libertarian: The Alliance That Isn't, by Bryan Caplan

Reforming local land use controls is one of those rare areas in whichActually, there are four other big areas where the two ideologies converge.

the libertarian and the progressive agree. The current system restricts

the freedom of the property owner, and also makes life harder for poorer

Americans. The politics of zoning reform may be hard, but our land use

regulations are badly in need of rethinking.

1. Immigration. Immigration restrictions deprive billions of basic liberties, impoverish the world, and do so on the backs of the global poor, most of whom are non-white.

2. Occupational licensing. Licensing laws bar tens of millions of people from switching to more lucrative and socially valuable occupations, all to benefit richer insiders at the expense of poorer outsiders.

3. War, especially the War on Terror. Since 2002, the U.S. has literally spent trillions fighting the quantitatively tiny problem of terrorism by waging non-stop wars in the Middle East. We don't know what the Middle East would have looked like if the U.S. had stayed out, but it's hard to believe it would be worse. And there's no end in sight.

4. The criminal justice system, especially the War on Drugs. Hundreds of thousands of non-violent people, disproportionately poor and non-white, are in prison. Why? To stop willing consumers from doing what they want with their own bodies.

These four issues are so massive, you'd expect a staunch progressive/libertarian alliance would have been forged long ago. But of course it hasn't. Why not? Some progressives flatly disagree with one or more of these policies; see Bernie contra open borders. But the bigger stumbling block is that progressives place far lower priority on these issues than libertarians. That includes war, unless the Republicans hold the White House.

Why not? I regretfully invoke my Simplistic Theory of Left and Right. The heart of the left isn't helping the poor, or reducing inequality, or even minority rights. The heart of the left is being anti-market. With some honorable exceptions, very few leftists are capable of being excited about deregulation of any kind. And even the leftists who do get excited about well-targeted deregulation get far more excited about stamping out the hydra-headed evils of market.

Can we make parallel accusations against libertarians? Sure. The second half of my Simplistic Theory says: The heart of the right is being anti-left. Since most libertarians loosely identify with the right, stubbornly focusing on housing, immigration, licensing, peace, and criminal justice is dry. Though these five areas are plausibly the biggest and most harmful abridgements of human freedom on Earth, it's more exciting for libertarians to dwell on symbolic issues that drive the left to apoplexy.

Prove me wrong, kids. Prove me wrong.

(23 COMMENTS)

June 21, 2017

Build, Baby, Build, by Bryan Caplan

Housing advocates often discuss affordability, which is defined by

linking the cost of living to incomes. But the regulatory approach on

housing should compare housing prices to the Minimum Profitable

Construction Cost, or MPPC. An unfettered construction market won't

magically reduce the price of purchasing lumber or plumbing. The best

price outcome possible, without subsidies, is that prices hew more

closely to the physical cost of building.In a recent paper with Joseph Gyourko, we characterize the

distribution of prices relative to Minimum Profitable Construction

Costs across the U.S... We base our estimates on an "economy" quality home, and assume

that builders in an unregulated market should expect to earn 17 percent

over this purely physical cost of construction, which would have to

cover other soft costs of construction including land assembly.

We then compare these construction costs with the distribution of

self-assessed housing values in the American Housing Survey. The

distribution of price to MPPC ratios shows a nation of extremes. Fully,

40 percent of the American Housing Survey homes are valued at 75

percent or less of their Minimum Profitable Production Cost... Another 33 percent of

homes are valued at between 75 percent and 125 percent of construction

costs.[...]

But most productive parts of America are unaffordable. The National

Association of Realtors data shows median sales prices over $1,000,000

in the San Jose metropolitan area and over $500,000 in Los Angeles. One

tenth of American homes in 2013 were valued at more than double Minimum

Profitable Production Costs, and assuredly the share is much higher

today. In 2005, at the height of the boom, almost 30 percent of American

homes were valued at more than twice production costs.

We should blame the government, especially local government:

How do we know that high housing costs have anything to do with

artificial restrictions on supply? Perhaps the most compelling argument

uses the tools of Economics 101. If demand alone drove prices, then we

should expect to see places that have high costs also have high levels

of construction.The reverse is true. Places that are expensive don't build a lot and

places that build a lot aren't expensive. San Francisco and urban

Honolulu have the highest ratios of prices to construction costs in our

data, and these areas permitted little housing between 2000 and 2013. In

our sample, Las Vegas was the biggest builder and it emerged from the

crisis with home values far below construction costs.

The top alternate theory is wrong:

The primary alternative to the view that regulation is responsible

for limiting supply and boosting prices is that some areas have a

natural shortage of land.

Albert Saiz's (2011) work on geography and housing supply shows that

where geography, like water and hills, constrains building, prices are

higher. He also finds that measures of housing regulation predict less

building and higher prices.

But lack of land can't be the whole story. Many expensive parts of

America, like Middlesex County Massachusetts, have modest density levels

and low levels of construction. Other areas, like Harris County, Texas,

have higher density levels, higher construction rates and lower prices...If land scarcity was the whole story, then we should expect houses on

large lots to be extremely expensive in America's high priced

metropolitan areas. Yet typically, the willingness to pay for an extra

acre of land is low, even in high cost areas. We should also expect

apartments to cost roughly the cost of adding an extra story to a

high-rise building, since growing up doesn't require more land.

Typically, Manhattan apartments are sold for far more than the

engineering cost of growing up, which implies the power of regulatory

constraints (Glaeser, Gyourko and Saks, 2005).

Which regulations are doing the damage? It's complicated:

Naturally, there are also a host of papers, including Glaeser and

Ward (2009), showing the correlation between different types of rules

and either reductions in new construction or increases in prices or

both. The problem with empirical work any particular land use control is

that there are so many ways to say no to new construction. Since the

rules usually go together, it is almost impossible to identify the

impact of any particular land use control. Moreover, eliminating one

rule is unlikely to make much difference, since anti-growth communities

would easily find ways to block construction in other ways.

Functionalists are wrong, as usual:

Empirically, there is also little evidence that these land use controls

correct for real externalities. For example, if people really value the

lower density levels that land use controls create, then we should

expect to see much higher prices in communities with lower density

levels, holding distance to the city center fixed. We do not (Glaeser

and War, 2010). Our attempt to assess the total externalities generated

by building in Manhattan found that they were tiny relative to the

implicit tax on building created by land use controls (Glaeser, Gyourko

and Saks, 2005).

What's to be done? State governments are our least-desperate hope:

The right strategy is to start in the middle. States do have the ability

to rewrite local land use powers, and state leaders are more likely to

perceive the downsides of over regulating new construction. Some state

policies, like Masschusetts Chapter 40B, 40R and 40S, explicitly attempt

to check local land use controls. In New Jersey, the state Supreme

Court fought against restrictive local zoning rules in the Mount Laurel

decision. If states do want to reform local land use controls, they might start

with a serious cost benefit analysis and then require localities to

refrain from any new regulations without first performing cost-benefit

analyses of their own.

It will be a great day when constructing new housing regulations is as big a bureaucratic nightmare as constructing new housing is now!

(1 COMMENTS)June 20, 2017

Positive-Sum Diversity, by Bryan Caplan

If, as in Putnam's original story, diversity per se were really bad for growth, segregation would sharply raise average trust. Indeed, segregating two communities could conceivably raise trust in bothIs there any way diversity could end up being a social positive, rather than merely zero-sum? Sure. The top mechanism to consider:

communities. This is what makes diversity a special social variable.

If diversity in and of itself has bad effects, so does integration -

regardless of the characteristics of the mingling populations. If the

effects of diversity are demographic effects in disguise, however,

integration has distributional effects, but is zero-sum overall.

Standard economic theory says that good things have decreasing marginal utility and bad things have increasing marginal disutility. Doubling the quantity of food less than doubles the social value of food. Doubling the quantity of pollution more than doubles the social harm of pollution. Now suppose you can either have a segregated society, where half the population has 25% trust and half has 75%, or an integrated society, where the whole population has 50%. While average trust is the same in both scenarios, the social effects of trust should be, on net, better in the integrated society. Why? Because the net benefits of moving from 50% to 75% trust will, by standard economic logic, be smaller than the net benefits of moving from 25% to 50% trust.

One variant on this story: Innovation itself might vary non-linearly with trust. Very low trust might choke off innovation entirely, while moderate trust provides a solid foundation for dynamism. Returning to the 25%/75% scenario, homogeneity allows growth only in the high-trust enclave, while diversity allows growth in both.

Are such effects genuine? Unfortunately, I've seen few papers that test for non-linear benefits of trust, except for this paper finding negative marginal effects of high trust on GDP per capita.* Anything I've missed?

* Nor should we forget the historic crimes that homogeneous societies like Germany and Japan have inflicted on out-groups and dissidents.

(1 COMMENTS)

June 19, 2017

Special Diversity, by Bryan Caplan

Now a diversity skeptic could look at Putnam's results and say: "Fine, diversity per se is no big deal. But Putnam does show that blacks and Hispanics have low trust. And that's controlling for household income, the area's poverty rate, and Spanish prevalence, all of which further depress trust. The presence of blacks and Hispanics is truly terrible."

Now a diversity skeptic could look at Putnam's results and say: "Fine, diversity per se is no big deal. But Putnam does show that blacks and Hispanics have low trust. And that's controlling for household income, the area's poverty rate, and Spanish prevalence, all of which further depress trust. The presence of blacks and Hispanics is truly terrible." The easiest reply is: "You're right qualitatively, but not quantitatively." The whole point of a regression is to measure the size of effects, not just their directions - and the size of demographic effects is modest. Suppose the black share rises from 5% to 55%, the poverty rate rises from 10% to 40%, and average household income falls from $75k to $25k. This drastic demographic shift reduces Putnam's predicted trust by .31*.50 + .66*.5 + .5*.14 = .56. Is that massive? No, because Putnam measures trust on a 4-point scale. .56 is less than 20% of size of the trust spectrum - noticeable, but hardly the end of the world.

But there's a subtler reply. Namely: The effect of demographics on trust is zero-sum. If low-trust people move into a high-trust area, the change is bad for the incumbents but good for the entrants. Calling black migration "bad for trust" is just NIMBYism: keeping low trust away from you doesn't make society's trust higher.

Isn't this always true? No. If, as in Putnam's original story, diversity per se were really bad for growth, segregation would sharply raise average trust. Indeed, segregating two communities could conceivably raise trust in both communities. This is what makes diversity a special social variable. If diversity in and of itself has bad effects, so does integration - regardless of the characteristics of the mingling populations. If the effects of diversity are demographic effects in disguise, however, integration has distributional effects, but is zero-sum overall.

In a sense, then, Putnam was right to focus on diversity, because diversity is conceptually special. In the real world, arguments about diversity usually boil down to identity politics: Diversity is bad if it hurts my group, good if it helps my group. In theory, however, you could have an anti-diversity universalist - someone who thinks that society as a whole will be better off if people stick to their own kind. Putnam's empirics suggest that anti-diversity universalists are rare for a reason: The numbers just don't add up.

(7 COMMENTS)

June 15, 2017

Trust and Diversity: Not a Bang But a Whimper, by Bryan Caplan

Diversity does not produce 'bad race relations' or ethnically-defined group hostility, our findings suggest. Rather, inhabitants of diverse communities tend to withdraw from collective life, to distrust their neighbours, regardless of the colour of their skin, to withdraw even from close friends, to expect the worst from their community and its leaders, to volunteer less, give less to charity and work on community projects less often, to register to vote less, to agitate for social reform more , but have less faith that they can actually make a difference, and to huddle unhappily in front of the television. Note that this pattern encompasses attitudes and behavior, bridging and bonding social capital, public and private connections. Diversity, at least in the short run, seems to bring out the turtle in all of us.What's impressive about Putnam's piece, however, is that he takes the danger of spurious correlation so seriously:

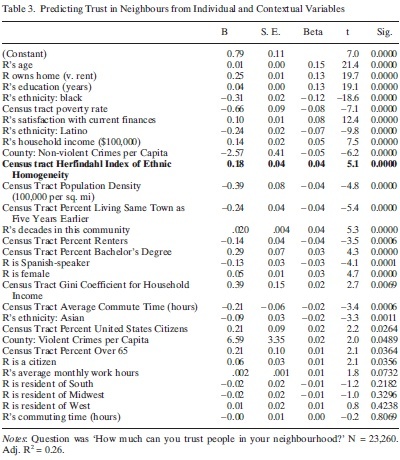

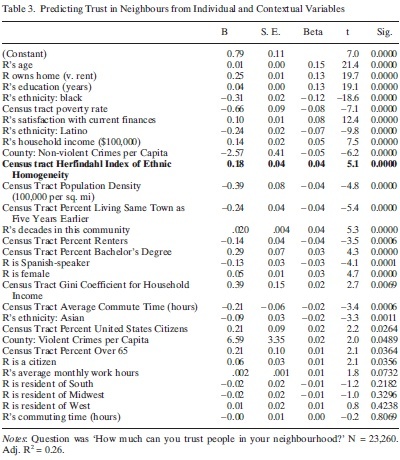

[T]he diverse communities in our study are clearly distinctive in many other ways apart from their ethnic composition. Diverse communities tend to be larger, more mobile, less egalitarian, more crime-ridden and so on. Moreover, individuals who live in ethnically diverse places are different in many ways from people who live in homogeneous areas. They tend to be poorer, less educated, less likely to own their home, less likely to speak English and so on. In order to exclude the possibility that the seeming 'effect' of diversity is spurious, we must control, statistically speaking, for many other factors.Indeed. And here is what Putnam finds when he uses multiple regression to predict individuals' trust on a 4-point scale.

Putnam's measure of diversity - the Census tract Herfindahl Index of Ethnic Homogeneity - is in bold. It's the sum of the squares of each group's population shares, so it theoretically ranges - note the reverse coding! - from 0 (infinite diversity) to 1 (zero diversity). But since Putnam only sub-divides the population into four groups - Hispanic, non-Hispanic white,

Putnam's measure of diversity - the Census tract Herfindahl Index of Ethnic Homogeneity - is in bold. It's the sum of the squares of each group's population shares, so it theoretically ranges - note the reverse coding! - from 0 (infinite diversity) to 1 (zero diversity). But since Putnam only sub-divides the population into four groups - Hispanic, non-Hispanic white,non-Hispanic black, and Asian - his diversity measure can't fall below 4*.25^2=.25.

Now imagine we move from a world with zero diversity to the maximum diversity. According to Putnam's results, how much will this reduce trust? .18*.75=.14. Is that a lot? No way. Remember, he's using a 4-point scale. And since the current national Herfindahl Index of Ethnic Homogeneity is about .46, moving from the diversity of today to maximum diversity reduces predicted trust by a microscopic .18*.21=.04. "Diverse" communities have low trust, but the reason isn't that diversity hurts trust; it's that non-whites - especially blacks and Hispanics - have low trust.

What's especially striking, though, is that Putnam finds several variables that strongly predict trust that almost no one discusses. Look at the effect of home-ownership. Not only do home-owners average .25 higher trust; there's also a -.14 coefficient on "Census Tract Percent Renters." Net effect of moving from 0% to 100% home ownership: .39. Holding all else constant, citizenship is good for trust: a mere .06 for the individual, but a solid .21 for the community. Net effect of moving from 0% to 100% citizenship: .27. There are also big effects of crime, population density, and commuting time. Geographic mobility, strangely, seems to reduce individual trust but raise social trust.

The latter variables don't just matter more than trust; they're also much more policy-relevant. Reducing diversity is very hard; indeed, without massive human rights violations, it's almost impossible. Home ownership, in contrast, can be fostered with not only tax incentives (the standard way), but housing deregulation (the wise way). Population density, similarly, can be reduced by deregulating development of surburban and rural land. Commuting time can be slashed with better public transit (the standard way) or congestion pricing (the wise way). Better policing and law enforcement - not to mention thoughtful decriminalization - all reduce crime rates. And if we take the estimated benefits of citizenship at face value, it can be raised to 100% with the stroke of an amnesty pen.

Putnam's numerous alt-right fans seem to relish his anti-diversity claims because he lends an air of respectability to their misanthropy. But if you read Putnam's whole article, it's hard to detect any ill will. Why then would he so grossly overstate the dangers of diversity? My best story is just confirmation bias. Early on in his research, Putnam found strong univariate links between diversity and trust. When better methods show that this relationship matters slightly, Putnam - like most human beings - treats this as a vindication of his initial claims. But if all you knew were Putnam's final results from Table 3, you'd never reach Putnam's anti-diversity conclusion. Diversity's so unimportant for trust, you might not mention it at all.

(5 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers