Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 76

October 18, 2017

Anti-Market Bias in One Sentence, by Bryan Caplan

The

potential demise of the trade deal prompted supportive messages from

labor unions, including the A.F.L.-C.I.O. and the United Steelworkers,

as well as some Democrats."Any

trade proposal that makes multinational corporations nervous is a good

sign that it's moving in the right direction for workers," said Senator

Sherrod Brown, Democrat of Ohio.

According to the National Journal, Brown shares a nine-way tie for most liberal Senator.

For more on anti-market bias, see The Myth of the Rational Voter, now reluctantly enjoying its ten-year anniversary...

October 17, 2017

Thoughts on the UMich Immigration Debate, by Bryan Caplan

1. Hans von Spakovsky was the most lawyerly opponent I've ever debated. His first (and second) approach to almost any issue was simply to describe the law. In most cases, he didn't even defend its wisdom or justice. Instead, he simply exhorted people to obey the law or convince Congress to change it.

2. Still, after a great deal of legal description, von Spakovsky finally shared his actual view: low-skilled immigration should be sharply reduced in favor of high-skilled immigration. When asked about refugees, he refrained from calling for outright cuts in the quota; instead, he maintained that existing numbers are roughly the most we are capable of handling.

3. The debate was explicitly about Trump's views on immigration, and von Spakovsky has pretty close ties to the administration. But von Spakovsky said almost nothing about Trump or his policies - and studiously failed to defend the president I repeatedly called "intellectually lazy and irrational." Perhaps he respects Trump so deeply that he considered my claims unworthy of a response. Or perhaps - like many elite Republicans - he avoided the topic because he is well-aware of Trump's glaring epistemic shortcomings.

4. The most engaging part of the debate, at least for me, began when my opponent spontaneously described his traffic tickets. This seems to show that - contrary to his grandiose claims about its sanctity - he's often not ashamed to break the law. In other words, he's an normal American driver. You could argue that traffic laws are uniquely bad, but that's silly. They plausibly protect other human beings from dangerous driving - and compliance is usually only a minor inconvenience. Why, then, would it be wrong to break immigration laws - which immensely harm would-be immigrants at great economic cost to natives? If anything, we should enforce traffic laws far more strictly than immigration laws.

5. During Q&A, Reason's Shikha Dalmia amplified my point by referencing the slogan that Americans commit three felonies a day. Von Spakovsky did not dispute her claim, but drew a strong distinction between natives' accidental law-breaking and illegal immigrants' deliberate law-breaking - an odd retreat for such a lawyerly thinker. When I pointed out that natives often knowingly break the law, my opponent declined to call for a strict crack-down on said scofflaws.

6. I repeatedly pointed out that governments selectively enforce laws all the time. Indeed, they have no choice; there aren't enough resources in the world to enforce all the laws we have. Furthermore, governments often officially announce their enforcement policies, so people know what to expect. Given this, I don't even see what the legal objection to DACA or DAPA is supposed to be.

7. I argued that Trump's travel ban bears little connection to the problems he claims to be worried about. Saudi Arabia isn't on the list, even though 15 of the 19 9/11 attackers were Saudi. Von Spakovsky dismissed my claim by by providing details about how the administration formulated its new policy. He even urged listeners to go to the White House webpage. This morning, I took his advice. A typical passage:

The Secretary of Homeland Security assesses that the following countriesI am perfectly happy to admit that there is a bureaucratic process at work. There always is. But if an intellectually lazy, irrational president wants X, are his functionaries going to tell him he's wrong or unfair? Of course not. Instead, they'll go through a flurry of procedure to get the "right" answer. That's how committees work: Busywork + Legalese = Foregone Conclusion.

continue to have "inadequate" identity-management protocols,

information-sharing practices, and risk factors, with respect to the

baseline described in subsection (c) of this section, such that entry

restrictions and limitations are recommended: Chad, Iran, Libya, North

Korea, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. The Secretary of Homeland Security

also assesses that Iraq did not meet the baseline, but that entry

restrictions and limitations under a Presidential proclamation are not

warranted.

8. My opponent strongly rejected any keyhole solutions for alleged downsides of low-skilled immigration. But other than appealing to the value of equality, I detected no concrete objection.

9. I am a weird human being, but I am self-aware. This routinely leads me to wonder how other people perceive me. Von Spakovsky was very polite to me both publicly and privately, but he must think there's something very wrong with me. What exactly would that be? Partly, I'm an Ivory Tower professor who doesn't understand - or just can't accept - how the "real world" works. Partly, I'm out of touch with America. He didn't seem to mistake me for a bog-standard leftist, which was nice. On reflection, I'm probably far worse in his eyes than he ever realized. But seeing yourself through the eyes of another is no mean feat.

10. Did either of us change anyone's mind? I suspect I persuaded a few people to rethink the sanctity of the law. Von Spakovsky, for his part, might have spurred a few people to read some laws for themselves instead of accepting media summaries of them. But overall, I'm afraid even the short-run effect on people's thinking was minimal. Changing minds on this issue is going to require a lot more than a debate.

11. Still, as far as intellectual experiences go, the debate was a far better than a protest.

(7 COMMENTS)

October 16, 2017

Does Trump's Immigration Agenda Harm Democracy? My Opening Statement, by Bryan Caplan

1. I usually try to stick to timeless issues. For this debate, I had to discuss and analyze current events in detail.

2. We were originally going to discuss Trump's immigration policies, but it's not clear that he'll manage to dramatically change immigration policy. That's why we switched to his immigration agenda - i.e., the policies Trump would like to impose.

3. Since I put no intrinsic value on democracy, I'd rather argue that immigration policies are harmful, rather than "harmful for democracy." But I think I learned a good deal from sticking to the agreed topic. Hopefully you'll agree!

Does Trump's Immigration Agenda Harm Democracy?

Let's start with the big

question: What does it mean to "harm democracy"? It's tempting to cynically say: "harms democracy" equals "clashes with my

favorite policies" or even "fails to give power to my party." But if you get some distance, there are plenty

of plausible standards against which to judge democratic performance. Above all:

1. In a healthy democracy,

leaders calmly assess the evidence before forming a plan to solve social

problems. They consider costs as well as

benefits.

2. In a healthy democracy,

leaders seek objective estimates of policies' actual effects, even if they

don't like the answers. For example, if

they're setting the minimum wage, they'll want sober estimates of the effect of

a $1/hour increase on the number of workers hired.

3. In a healthy democracy,

leaders defuse popular prejudices instead of pandering to them. If the majority wrongly believes leeches cure

cancer, leaders don't advocate a $100B National Leech Fund. Instead, they politely but firmly refuse to

waste of taxpayer money.

These standards aren't

Democratic or Republican, liberal or conservative. They're common sense and common decency.

Now, you might say, "Common

sense and common decency aren't so common."

Or even: "I don't know any

leaders of either party who live up to these standards. Successful politicians are experts at winning

and retaining power, not carefully crafting wise policy. And the way to win and retain power is to

tell voters what they want to hear, whether it's true or not."

If that's your reaction, I

completely agree. I have a whole book - called

The Myth of the Rational Voter: Why

Democracies Choose Bad Policies - on the shortcomings of democracy. But the fact that politicians routinely harm

democracy hardly implies they're all equally

harmful. And of course, politicians

could be better on some issues than others.

So how does Donald Trump's approach to immigration policy measure up?

1. In the real world,

politicians rarely calmly assess evidence before offering solutions. If you know a politicians' ideology, you can

generally predict what he's going to say about even the most complex

issues. And immigration is an especially

emotional issue. Even so, Trump's statements

about immigration are unusually

intellectually lazy and irrational. Consider

some of his main public reflections on the topic.

a. He's claimed there are

30-34 million illegal immigrants in the U.S. - roughly triple the number

virtually any quant accepts. When asked

for a source, he said, "I am hearing it from other people, and I have seen it

written in various newspapers. The truth is the government has no idea how many

illegals are here."

b. "The Mexican Government is

forcing their most unwanted people into the United States." Evidence for this strange conspiracy

theory? None. And: "Likewise, tremendous infectious disease

is pouring across the border."

c. "I will build a great

wall -- and nobody builds walls better than me, believe me - and I'll build them very inexpensively. I

will build a great, great wall on our southern border, and I will make Mexico

pay for that wall. Mark my words."

d. On deportations: "We're

rounding 'em up in a very humane way, in a very nice way. And they're going to

be happy because they want to be legalized. And, by the way, I know it doesn't

sound nice. But not everything is nice."

Hasn't Trump also made

numerous seemingly incompatible statements about immigration? Sure.

Which proves my point: he's so intellectually lazy and irrational he

can't keep his own story straight.

2. Trump's low-quality

thinking might be forgivable if his conclusion about immigration were, by

coincidence, roughly accurate. But

they're not. Careful scholars have been

studying immigration for decades. Here

are their top discoveries.

a. Contrary to Trump's many

claims about the economic damage of immigration, the overall economic benefits

of immigration are enormous. The idea is

simple: Immigrants normally move from countries where wages are low to countries

where wages are high. Why do employers them

pay so much more in rich countries than in poor countries? Because foreign workers are much more productive in rich countries than they

are in their home countries. A Mexican

farmers can grow a lot more here than he can in Mexico. When he does so, the immigrant isn't merely

enriching himself. He enriches everyone

who eats. Immigration's gains are so

vast that researchers estimate that - in a world where anyone could work

anywhere - global production would roughly DOUBLE.

b. Trump has blamed

immigration for seriously harming native workers. Scholarly estimates, however, generally say

that Americans workers are, on balance, richer

because of immigration. Basic point:

Immigrants who sell what you sell hurt you, but immigrants who sell what you buy help you. Since immigration raises total production,

gains naturally tend to outweigh losses.

There is debate about immigration's effects on wages and employment of

native high school dropouts. But even

estimates of these losses are low.

c. Trump has also argued that

immigrants are a clear fiscal burden on native taxpayers. This goes against the latest National Academy

of Sciences report, which finds a long-run average net gain of $58,000 per

immigrant. There does seem to be a net

fiscal burden of high school dropout immigrants, especially older high school

dropouts. But even they're a much better

fiscal deal than native-born dropouts, because their home countries pay for

their education.

d. Trump's claims about

immigrant crime have been widely-quoted.

But specialists in immigrant crime almost universally find immigrants

have lower crime rates than natives - about one-third lower in recent

data.

3. Is Trump's immigration

agenda at least sincere? Let's look at

the problems he says he want to solve and the solutions he proposes to solve

them - and see how well they fit together. If Trump really thought "[T]remendous

infectious disease is pouring across the border" with Mexico, you'd expect him

to instruct the Centers for Disease Control to prioritize this problem, or

impose new health restrictions at the Mexican borders. He hasn't; in fact, it seems like he's

forgotten he ever mentioned Mexican epidemics.

Similarly, if Trump were really worried about Muslim terrorists, he

would presumably want to extend his high-profile executive order to Saudi

Arabia. After all, 15 of the 19 9/11

attackers were Saudi. But, no. The heart of Trump's immigration strategy is

to pander to popular prejudices against foreigners, then loudly call for some

kind of action. It's the Activist's

Fallacy: "Something must be done. This

is something. Therefore, this must be

done."

But you don't have to believe

me. You can also see what Trump says

when he thinks voters aren't watching. The

transcript of Trump's conversation with Mexican President Nieto was leaked a

few months ago. Trump speaking: "Because

you and I are both at a point now where we are both saying we are not to pay

for the wall. From a political standpoint, that is what we will say. We cannot say that anymore because if you are going to say that

Mexico is not going to pay for the wall, then I do not want to meet with you

guys anymore because I cannot live with that. I am willing to say that

we will work it out, but that means it will come out in the wash and that is

okay. But you cannot say anymore that the United States is going to pay for the

wall. I am just going to say that we are working it out. Believe

it or not, this is the least important thing that we are talking about, but

politically this might be the most important talk about."

In short,

Trump doesn't really care if Mexico will pay for the wall, but he really cares

if Americans believe Mexico will pay

for the wall.

Which

brings me to the one good thing I have to say about Trump's immigration agenda:

He's unlikely to actually accomplish much of it. While he presents himself as a great

negotiator, he's primarily an entertainer.

When he endorsed the RAISE Act - which really would greatly reduce immigration

- even fellow Republican politicians showed little interest. So Trump got bored and moved on to the next

exciting scene on his Presidential Reality Show.

But

aren't other politicians bad, too? Of

course. Demagoguery is a key ingredient

of any politicians' path to power - and scapegoating foreigners is classic

demagoguery. But Trump has taken

anti-foreign demagoguery to a new level - or at least a local maximum. If he had his way, we'd lose most of the

tremendous social gains of immigration we've enjoyed over the last fifty

years. And his problem is not that he's

made subtle errors. Trump's problem is

that he emoting, not thinking - like a kid who tries to solve algebra problems

by asking, "How do x and y make me feel?" Our problem is that instead of giving him an

F, we've made him president.

(6 COMMENTS)

October 10, 2017

Me in Michigan, by Bryan Caplan

1. I'm lecturing on "Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk" at Michigan State on Thursday, October 12, at 7 PM.

2. I'm debating Hans von Spakovsky of the Heritage Foundation on "America First: Does Trump's Immigration Agenda Harm America?" at the University of Michigan on Friday, October 13, at 7 PM.

If you're there, please introduce yourself after the talk. :-)

(1 COMMENTS)

October 9, 2017

Hume on Pessimistic Bias, by Bryan Caplan

Every session of parliament, during this reign, we meet with grievousHT: Dan Klein

lamentations concerning the decay of trade and the growth of popery:

Such violent propensity have men to complain of the present times, and

to entertain discontent against their fortune and condition. The king

himself was deceived by these popular complaints, and was at a loss to

account for the total want of money, which he heard so much exaggerated. It may, however, be affirmed, that, during no preceding period of

English history, was there a more sensible encrease, than during the

reign of this monarch, of all the advantages which distinguish a

flourishing people. Not only the peace which he maintained, was

favourable to industry and commerce: His turn of mind inclined him to

promote the peaceful arts: And trade being as yet in its infancy, all

additions to it must have been the more evident to every eye, which was

not blinded by melancholy prejudices.

(2 COMMENTS)

October 5, 2017

What's Killing Us? A Huemer Guest Post, by Bryan Caplan

What's

killing us? I made the following graph. I include the top ten causes of

death in the U.S., plus homicide and illegal drug overdoses, because

the latter two are actually discussed in political discourse.

Observations:

1. The top causes of death almost never appear in political discourse

or discussions of social problems. They're almost all diseases, and

there is almost no debate about what should be done about them. This is

despite that they are killing vastly more people than even the most

destructive of the social problems that we do talk about. (Illegal drugs

account for 0.7% of the death rate; murder, about 0.6%.)

2. This

is not because there is nothing to be done about the leading causes of

death. Changes in diet, exercise, and other lifestyle changes can make

very large differences to your risk of heart disease, cancer, and other

major diseases, and this is well-known.

3. It's also not because

it's uncontroversial what we should do about them, or because everybody

already knows. The government could, for example, try to discourage

tobacco smoking, alcohol use, and overeating, and encourage exercise.

There are many ways this could be attempted. Perhaps the government

could spend more money on trying to cure the leading diseases. There

obviously are policies that could attempt to address these problems, and

it would certainly not be uncontroversial which ones, if any, should be

adopted. Those who support social engineering by the government might

be expected to be campaigning for the government to address the things

that are killing most of us.

4. Most of these leading killers are

themselves mainly caused by old age. If "Old Age" were a category, it

would be causing by far the majority of deaths. Again, it's not the case

that nothing could be done about this. We could be doing much more

medical research on aging.

5. It's also not that we just don't

care about diseases. *Some* diseases are treated as political issues,

such that there are activists campaigning for more attention and more

money to cure them. There are AIDS activists, but there aren't any

nephritis activists. There are breast cancer walks, but there aren't any

colon cancer walks.

6. Hypothesis: We don't much care about the

good of society. Refinement: Love of the social good is not the main

motivation for (i) political action, and (ii) political discourse. We

don't talk about what's good for society because we want to help our

fellow humans. We talk about society because we want to align ourselves

with a chosen group, to signal that alignment to others, and to tell a

story about who we are. There are AIDS activists because there are

people who want to express sympathy for gays, to align themselves

against conservatives, and thereby to express "who they are". There are

no nephritis activists, because there's no salient group you align

yourself with (kidney disease sufferers?) by advocating for nephritis

research, there's no group you thereby align yourself *against*, and you

don't tell any story about what kind of person you are.

In

conclusion, this sucks. Because we actually have real problems that

require attention. If we won't pay attention to a problem just because

it kills a million people, but we need it also to invoke some

ideological feeling of righteousness, then the biggest problems will

continue to kill us. And by the way, the smaller problems that we

actually pay attention to probably won't be solved either, because all

our 'solutions' will be designed to flatter us and express our

ideologies, rather than to actually solve the problems.

(15 COMMENTS)

October 4, 2017

The Pathos of Doing the Best I Can, by Bryan Caplan

...Ritchie Weber knows what it is like to hit rock bottom. Just two years ago he was spending nights huddled in a slide in Tacony Park on Torresdale Avenue... Heroin and child support consumed nearly all of his earnings - he had to scrounge dumpsters for food... but no matter how bad it got, he never missed a day of work. And he didn't let a week go by without seeing his nine-year-old boy.How Ritchie turned his life around, at least for the time being:

"It was a time in my life when drugs were so important to me that that is all I concerned myself about..." But even then Ritchie kept stopping by to see his son. "I had long hair and was unbathed for days at a time, and I remember crying to my son, telling him how I was sorry. And I remember my son hugging me, saying it was OK, as long as I just came to see him. That Christmas I didn't have anything for him. He said me just being there was all the present he needed."Of course, if I heard the same story from the point of view of Ritchie's son - or the boy's mom - I'd probably be feeling outrage rather than sorrow...

The turning point finally came when a friend tried to convince Ritchie that to conquer his addiction he needed a change of scenery; the friend had a contact in Florida who had agreed to set Ritchie up with a job and an apartment. Initially, Ritchie thought he should grasp at this lifeline, but the thought of leaving his young son instilled a strong conviction he couldn't simply flee from his problems. "It was the thought of never seeing him again that ripped through me... I knew I had to break down and face everything that I caused in order to keep my son in my life." Accordingly, Ritchie started attending AA and NA meetings, determined to claim his sobriety. Being homeless and sober was the hardest thing he had done.

(1 COMMENTS)

October 3, 2017

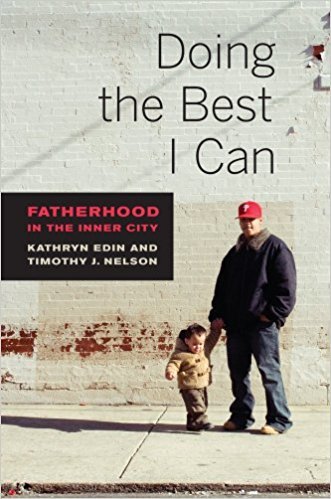

Doing the Best I Can: Social Science at Its Best, by Bryan Caplan

I'm a long-time fan of Kathryn Edin and Maria Kefalas'

Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage

(University of California Press, 2005). Only recently, however, did I discover that Edin had partnered with Timothy Nelson to write a sequel:

Doing the Best I Can: Fatherhood in the Inner City

(University of California Press, 2013). I'm delighted to report that the companion volume is even better than the original. Indeed, it's the finest work of social science I've read in years.

I'm a long-time fan of Kathryn Edin and Maria Kefalas'

Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage

(University of California Press, 2005). Only recently, however, did I discover that Edin had partnered with Timothy Nelson to write a sequel:

Doing the Best I Can: Fatherhood in the Inner City

(University of California Press, 2013). I'm delighted to report that the companion volume is even better than the original. Indeed, it's the finest work of social science I've read in years.The set-up: Edin and Nelson moved to an inner-city neighborhood in East Camden, then started meeting single fathers in poor neighborhoods in the greater Philadelphia area. Once their subjects were comfortable, they interviewed them in great detail about their lives and families. In the end, they got to know 110 fathers - often in a very personal way.

Over the seven years we spent on street corners and front stoops, in front rooms and kitchens, at fast food restaurants, rec centers, and bars in each of these neighborhoods, we persuaded 110 low-income unwed fathers to share their stories with us, sometimes over the course of several months, or even years. We recruited roughly equal numbers of African Americans and whites... Fathers ranged in age from seventeen to sixty-four, yet we made sure that roughly half of the fathers were over thirty when we spoke with them so we could tell the story of inner-city unwed fatherhood across the life course...Doing the Best I Can is immersive. As I read, I felt like I was there. Even better, though, Edin and Nelson never take their subjects' words at face value. They peer through the fog of self-justification, painting a gripping portrait of a dysfunctional subculture. Like Promises I Can Keep, the new book leaves little doubt that poverty is a state of mind - and that state of mind is low conscientiousness.

Because the men we were interested in talking with were often not stably attached to households, and some were involved in illicit activities they were eager to hide from outsiders, we did not attempt a random sample; instead, we tried for as much heterogeneity as we could.

The men in these pages seldom deliberately choose whom to have a child with; instead, "one thing leads to another" and a baby is born. Yet men often greet the news that they're going to become a dad with enthusiasm and a burst of optimism that despite past failures they can turn things around... In these early days, men often work hard to "get it together" for the sake of the baby - they try to stop doing the "stupid sh*t" (a term for the risky behavior that has led to past troubles) and to become the man their baby's mother thinks family life requires. But in the end, the bond - which is all about the baby - is usually too weak to bring about the transformation required.The book later elaborates on the "stupid sh*t":

What goes wrong between the euphoria of a baby's arrival and that child's fifth birthday, when surveys reveal that only one in three men will still be in a relationship with their child's mother? This chapter, an autopsy of relationship failure, doesn't focus on the proximal causes that feature again and again in the narratives throughout this volume - substance abuse, serious conflict, infidelity, incarceration, and so on... The corrosive effects of these factors have been well-documented. Instead, we attend here to the often-tawdry finales that blow their relationships apart.After the baby comes, single moms expect their children's fathers to change. But as many dads freely admit, they don't want to change - at least not much.

Dayton, a day laborer, says that he broke it off with his youngest child's mother "because she is the type of female that don't want to listen. She think she know everything. But I am not the type of guy that tolerates things like that." Donald and the mother of his fourteen-year-old child tried living together for a short time when his child was young, but "it ain't work," he states bluntly. "It lasted about three or four weeks. I couldn't take it." What went wrong? "I couldn't deal with her 'I'm the boss' attitude. She is a very controlling person, always trying to run my life and everybody else's life."Edin and Nelson radiate compassion for their subjects - far more than I could ever muster. But without their positivity and patience, they probably wouldn't have written nearly as good a book. And when they move from data collection to data analysis, they're hard-headed realists.

Thus, as soon as a woman has the baby, she can easily be perceived as just one more authority figure - the kind they've been rebelling against all their lives - who insists that he shape up and toe the line.

Even the title is far bleaker than it sounds. For the typical man they interviewed, "Doing the best I can" means "Doing the best I can... with what is left over." "Left over" after what? After the man takes care of himself - including the ongoing costs of alcohol, drugs, gambling, fighting, womanizing, and related vices. Next, if he's living with a new girlfriend, he helps her and her kids. Finally, if there's anything left, he doles it out to his biological children if and when the timing feels right to him. It's not quite "the least they can do," but Edin and Nelson readily see why the children's mothers deeply resent their exes' corrupt priorities.

Ten years ago, Scott Beaulier and I published a piece on "Behavioral Economics and Perverse Effects of the Welfare State." Our central claim: If behavioral economics helps explain anything in the real world, it helps explain poverty. Everyone deviates from the rational actor model from time to time, but the poor deviate far more. Few economists have shown much interest in our approach, but Edin and Nelson, using a radically different framework, reach essentially the same conclusion.

(5 COMMENTS)

September 28, 2017

The Forgotten Man/Woman, by Bryan Caplan

Men and women still don't seem to have figured out how to work or socialize together. For many, according to a new Morning Consult poll conducted for The New York Times, it is better simply to avoid each other.

Many

men and women are wary of a range of one-on-one situations, the poll

found. Around a quarter think private work meetings with colleagues of

the opposite sex are inappropriate. Nearly two-thirds say people should

take extra caution around members of the opposite sex at work. A

majority of women, and nearly half of men, say it's unacceptable to have

dinner or drinks alone with someone of the opposite sex other than

their spouse.

What are the underlying motives?

[P]eople described a cultural divide. Some said their social lives and

careers depended on such solo meetings. Others described caution around

people of the opposite sex, and some depicted the workplace as a fraught

atmosphere in which they feared harassment, or being accused of it.

This is all supposed to be terrible:

One reason women stall professionally, research shows, is that people have a tendency to hire, promote and mentor people like themselves.

When men avoid solo interactions with women -- a catch-up lunch or late

night finishing a project -- it puts women at a disadvantage.[...]

"Organizations are so concerned with their legal liabilities, but

nobody's really focused on how to reduce harassment and at the same time

teach men and women to have working relationships with the opposite

sex," said Kim Elsesser, author of "Sex and the Office: Women, Men and

the Sex Partition That's Dividing the Workplace."

The article is almost over, however, before it discusses the most obvious rationale for these norms:

People who follow the practice in their social lives described separate

spheres after couplehood. They said they wanted to safeguard against

impropriety -- or the appearance of it -- and to respect marriage and, in

some cases, Christian values. That often meant limiting opposite-sex

adult friendships to their friends' spouses.

And the piece never mentions who benefits most from these norms: husbands, wives, boyfriends, and girlfriends of the people who follow them! It's hard to imagine that these rules don't reduce the prevalence of adultery and cheating. And even if they didn't, the rules still provide reassurance and a sense of security for these Forgotten Men and Forgotten Women. Any considerate partner will take such feelings into account.

The world is full of trade-offs. If you make cross-gender relationships more comfortable at work, you also make them less comfortable at home. And as my Rotten Spouse Theorem emphasizes, you should expect anything that brings disharmony to your relationship to ultimately harm your entire family:

If you're abnormally high in self-discipline and your partner is abnormally low in jealousy, the NYT critique of current workplace norms is understandable. But not every couple is like that. In fact, they're a rare breed indeed.Of course, it's conceivable that you can hurt your spouse without

hurting your children. But probabilistically, you have to expect your

family members' pain to move in unison. Think general equilibrium:

The way you treat your spouse ripples out to your children. The way

you treat your spouse affects the way your spouse treats you, which

ripples out to your children. The direct effects are more visible, but

that doesn't make them more real. A good parent must, as Bastiat says, foresee the indirect effects of his behavior with the "inner eye of the mind."

(6 COMMENTS)

September 26, 2017

The Bias of Modern Art, by Bryan Caplan

I know that most art aficionados will attribute my philistine position to ignorance. But what's my theory about where they go wrong? I can hardly call them ignorant; they plainly know vastly more about the art they prize than I do. Instead, I blame their aesthetic errors on some well-known psychological biases. Leading the list:

1. Confirmation bias. Human beings have a serious case of "believing is seeing." If they expect some artworks to be good - say, because they're in a museum - they'll look around for the faintest sign of aesthetic merit. They'll rationalize. And before long, many viewers will convince themselves that almost anything they expected to be good is good.

2. Hindsight bias. Once people know what actually happened, they find it hard to believe that anything else was ever possible. Even when "luck" and "coincidence" clearly drive the results, we prefer stories about "deep causes" and "inevitability." Thus, when an artist achieves world-wide fame, our natural inclination is to attribute his success to aesthetic skill - and dismiss the possibility that he merely won a lottery.

3. Conformity. Psychologist Solomon Asch famously designed an experiment with one subject and seven confederates. He gave them a simple task - comparing the lengths of lines - then repeatedly ordered all the confederates to give the false answer. Result: When everyone else says something wrong, people do more than say the wrong thing. When debriefed, many subjects seem to sincerely believe the wrong thing. So if you're in a museum where everyone around you claims soup cans are great art, mere consensus can plausibly change your mind for no good reason.

4. Social Desirability Bias. People prefer to say and believe whatever sounds good. "The stuff in the museum is great" sounds a lot better than "My child could do that."

While these biases elegantly explain how modern art continues, they admittedly do little to explain how modern art arose. For that, you need a richer story, probably starting with artists' yearning for originality combined with the immense (and ever-rising) difficulty of actually coming up with anything that's both original and good.

You could respond, "If people enjoy modern art, who cares about its aesthetic merit?" I'm tempted to protest, "And people call me a philistine!" But the better answer is: because (a) in the short-run, bad art crowds out better art, and (b) in the long-run, the prevalence of bad art discourages people who justifiably dislike it from training to do something better.

Last point: the "ignorance" and "bias" stories can both be true! "People underrate modern art because they're ignorant" and "People overrate modern art because they're biased" are two independent mechanisms. So even if art aficionados correctly diagnose the philistines that surround them, they're missing half the picture.

(0 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers