Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 75

November 9, 2017

The Case Against Education Now Available for Preorder!, by Bryan Caplan

My next big book, The Case Against Education, is now available for preorder. Yes, I know, it's been a long time coming: I actually posted the first page on EconLog ten years ago, and have been working on the project in earnest since 2011.

My next big book, The Case Against Education, is now available for preorder. Yes, I know, it's been a long time coming: I actually posted the first page on EconLog ten years ago, and have been working on the project in earnest since 2011. Should regular blog readers buy it? Absolutely. While it's a book-length defense of the empirical importance of the signaling model of education, it's also an interdisciplinary odyssey through the subtleties of the economics, psychology, sociology, and philosophy of education. It's probably the longest and most research-intensive book I'll ever write. EconLog fans will know the gist of my story, but I've never blogged most of the topics in the book. Furthermore, in the process of writing, I've

changed my mind about several key issues - including the practical relevance of the so-called "ban" on IQ

testing for employment. And if you've ever found my writing entertaining, the sentences in The Case Against Education are as entertaining as I get.

Physical books should ship in January, but a homemade preorder certificate still makes a great holiday stocking stuffer. Isn't the book too depressing for the holidays? Not at all. The discovery that major policies could be vastly improved is always reason for joyous celebration...

(7 COMMENTS)

November 8, 2017

Lessons of the South Asian Swastika, by Bryan Caplan

When he was living in Burma, graphic novelist Guy Delisle noticed quite a few swastikas. Indeed, much of south Asia is full of swastikas. It's not because they're Nazi sympathizers. The swastika was a south Asian symbol until the Nazis ripped them off.

When he was living in Burma, graphic novelist Guy Delisle noticed quite a few swastikas. Indeed, much of south Asia is full of swastikas. It's not because they're Nazi sympathizers. The swastika was a south Asian symbol until the Nazis ripped them off.Now imagine you're visiting south Asia and see a group of natives strolling around in swastikas. How should you react - and what should you do? There are two main routes.

Route #1: After a swift negative visceral reaction, you remind yourself that they're not Nazis and mean no offense. So you calm down and keep your complaints to yourself. Eventually, you hedonically adapt: swastikas stop bothering you, and the swastika-wearers live in happy ignorance of your initial offense.

Route #2: You allow your swift negative visceral reaction to blossom into seething resentment. Even if they're not Nazis, they're negligently hurting your feelings. With anger as your muse, you shame the swastika-wearers: "Do you people have any idea how offensive that is?!" In all likelihood, they'll be taken aback. After all, you're just a stranger freaking out over a symbol they enjoy wearing. Maybe they'll go out of their way to defy you. But even if you successfully shame them into burning all their swastikas, you had to badly upset a bunch of people who meant you no harm in order to get your way.

Which is the better route? It's partly a numbers game. If there are a million Holocaust survivors and one oblivious swastika-wearing south Asian, expressing a little anger goes a long way. The complainer feels extra anger and the target feels extra shame, but 999,999 people have a more pleasant day.

If the numbers are more evenly matched, however, Route #1 is clearly superior. Why? Because it is a less circuitous, more reliable route to social harmony. In Route #1, people who take offense quietly calm themselves. In Route #2, people who take offense give into anger, which inspires conflict with the accused, who in turn feel some combination of sad and angry. If the sadness dominates, they probably stop; if the anger prevails, they probably escalate.

Couldn't you say the same about murder? Absolutely not. Murder is intrinsically bad. Swastika-wearing, in contrast, is only bad because it's currently a symbol of intrinsically bad things (like murder). We can easily imagine a world where the swastika is a symbol of maternal love. But we can't imagine a world where murder is good.

So what? Especially on social media, I often encounter people who decry novel offensive symbols and promote Route #2 as the appropriate response. I hereby urge them to reconsider. Yes, we have a few symbols closely identified with heinous evils: swastikas, klan outfits, blackface, the hammer-and-sickle. Since almost everyone in our culture who brandishes these symbols intends to insult innocent people, flipping out at those who so brandish has little collateral damage. But if a symbol is not yet closely identified with heinous evil, we should strive to not only leave well enough alone, but deescalate. Indeed, in the best of all possible symbolic worlds, fans of heinous evils would have no well-understood symbols to concisely express themselves. They'd have to spell it all out in longhand.

As usual, I'm not saying this to favor any prominent political faction. If you want to "raise awareness" about offensive Halloween costumes, you should stop. The same goes if you want to rally fellow patriots against football players who take the knee during the national anthem. If a symbol is ambiguous - as it almost always is - fomenting anger is just childish. But the other side won't extend you the same courtesy? Take comfort in the fact that anger is its own punishment - and be the change you want to see in the world.

(3 COMMENTS)

November 7, 2017

The Peculiar Political Economy of Reverse Grandfathering, by Bryan Caplan

The change to the mortgage interest deduction drew immediate attentionMinutes later, however, I breathed a sigh of relief. As is often the case in politics, I'm going to be grandfathered:

Thursday. Under current tax law, Americans can deduct interest payments

made on their first $1 million worth of home loans.

The bill would allowSo who's left to stand up for future home-buyers? Per Olsonian logic, future home-buyers themselves are all but silent, but the industries that plan to serve them are vocal indeed:

existing mortgages to keep the current rules, but for new mortgages,

home buyers would be able to deduct interest payments made only on their

first $500,000 worth of loans.

At least one major industry group, the National Association of HomeWhich raises an interesting question: Instead of lobbying to preserve the status quo, why doesn't the construction industry lobby for reverse grandfathering? Instead of limiting the full deduction to existing homeowners, why not do the opposite and limit it to new homeowners? To quote Winston Smith in 1984, "Do it to Julia! Not me!"

Builders, announced days before the bill was released that the group

would not support it, and others joined the attack within minutes of the

measure's unveiling.

If this sounds bizarre, note that rent control provisions often exempt new construction, at least for a time. Long-run credibility aside, there's a simple rationale: Exempting new units from regulation preserves (or even strengthens!) the incentive to keep building. The construction industry could easily push for parallel reverse grandfathering. So why not?

My preferred answer is that construction lobbyists have a Caplanian theory of lobbying. Nakedly pushing for big unpopular policies is hopeless. Instead, savvy lobbyists focus on boring but profitable details of crowd-pleasing policies. Only the construction industry wants a mortgage interest deduction limited to new construction, so pushing for this policy is futile. But wide swaths favor the mortgage interest deduction in general terms - and few have pondered whether it should be limited to current homeowners or apply to everyone. The smart play for the industry, then, is to forget grandfathering is even on the agenda, and defend their favorite tax loophole. Which is precisely what they're doing.

Not, contrary to Scott, that there's anything wrong with that...

(0 COMMENTS)

November 2, 2017

The Value of the Reformation: Reply to Somin, by Bryan Caplan

1. Even had Luther stayed loyal to the Pope or

been quickly crushed, it is likely that other serious challenges to the

Catholic Church would have arisen in the 16th century. Some already had

previously (e.g. - the Hussites), and many people were dissatisfied with

the religious status quo for a variety of reasons.

I agree. But the body count of the actual Reformation was so high, it's hard to believe the alternative would have been worse. And there's at least a modest chance that the alternative challenge would have been relatively tolerant, secular, and humanist, instead of another variant on violent fundamentalism.

Moreover,

technological, social, and economic developments (e.g. - the printing

press, changing military technology, the start of the Renaissance) made

organized resistance to the Church easier than in the past. And once

resistance spread, it was likely to lead to extensive warfare, because

neither the rebels nor the Church were likely to compromise easily.

Plausible, but so are many more optimistic scenarios. Precisely because the contemporary Catholic Church was "corrupt," I say it was open to moderate reforms and a slow growth of pluralism.

2. Bryan asks whether the Church would have done better to try to crush

Lutheranism in its cradle. But the Pope (supported by the Holy Roman

Emperor) did in fact try hard to do just that, at least after 1521 or

so. Their efforts led to the German Wars of Religion, which lasted 30

years and took many lives (i.e. - exactly the result Bryan decries).

Perhaps the Pope and the Emperor would have been more successful had

they moved against Luther still earlier. But it's far from clear.

I'm well-aware of the Church's violent response - and freely concede that Catholics might have been able to avert bloodshed with tolerance. That's definitely what I would have done in their shoes. But given Luther's subsequent writings, I can't give this upbeat scenario better than one-in-three odds. Simply double-crossing Luther at the Diet of Worms seems like a better gambit for peace, though of course that could have ended in disaster, too.

3. The Thirty Years War - the bloodiest of the conflicts Bryan

attributes to the Reformation - was far more than just a Protestant vs.

Catholic conflict. Many of the combatants had other agendas they cared

about more. To take the most obvious example, Catholic France backed the

"Protestant" side in the conflict in Germany because Louis XIII and

Cardinal Richelieu were more interested in curbing the power of the Holy

Roman Emperor than in promoting the true faith. Whether the Reformation

(or religion generally) can reasonably be blamed for this war is at the

very least highly debatable.

All true, except for the last sentence. The Reformation gave two rival movements compelling moral rationales for maximum savagery, and destabilized the entire continent. You'd expect power-hungry pragmatists to take advantage of the chaos. But without the Reformation, there would have been far less chaos to take advantage of.

4. Bryan ignores perhaps the

greatest benefit of the Reformation: the collapse of the Catholic

Church's near monopoly over intellectual life in Western and Central

Europe. Most early Protestants were far from advocates of toleration.

But their rise inevitably led to greater intellectual pluralism in

Europe, which in turn helped give rise to the Enlightenment, modern

liberalism, and so on. Would the same thing have happened as quickly if

the Church had retained its dominant position? I am skeptical.

Over what time frame? The Enlightenment started about two centuries after the Reformation. Two centuries when - as Ilya points out - printing presses proliferated, drastically cutting the cost of spreading novel and diverse ideas. The Catholic Church's near-monopoly could easily have been peacefully eroded during those two centuries. If this sounds like wishful thinking, look at what happened to European countries that remained solidly Catholic after the Reformation. The Catholic Church peacefully became virtually powerless in every case. Even Poland.

November 1, 2017

Touchy-Feely Bull in a China Shop, by Bryan Caplan

On the surface, admittedly, touchy-feely pedagogy seems unobjectionable. The teachers warmly express their affection for the students. They believe in treating students like human beings - and making learning fun. Most seem quite sincere: They're convinced that their methods are great for everyone. Alas, they're mistaken. Our chief objections:

1. Some subjects simply don't lend themselves to a touchy-feely approach. Math is the obvious example; you can't teach math by asking kids "How do the numbers make you feel?" But the same goes for writing. If you want to improve students' writing, you must make liberal use of your red pen.

2. The touchy-feely approach crowds out measurable learning. Teachers in virtually every one of my kids' classes (none of which had "Art" in the title) assigned art projects - posters, name tags, flags, and so on. The voluminous time the students spent on these projects could have been focused on techniques that actually yield knowledge: reading the textbook, solving problems, writing essays, and taking tests.

3. Some students clearly enjoy the touchy-feely approach. But plenty of others resent it. A few - like my kids - find it humiliating. So contrary to the party line, touchy-feely is not "Better for everyone."

4. The party line is especially galling because the practitioners of touchy-feely pedagogy don't settle for passive obedience. In a traditional academic program, students are expected to complete their work, but no one says they have to enjoy it. In a touchy-feely program, in contrast, teachers keep insisting, "This is fun!" and "Students love doing this!" And every student's supposed to play along.

5. I didn't bother sharing my concerns with my sons' teachers because I deemed it fruitless. But if I had vented, I bet they would have replied thusly: "But all the kids I talk to love my approach." Plausibly true, but deeply misleading, due to two powerful psychological forces: Social Desirability Bias and confirmation bias. Long story short: students keep negative opinions to themselves, and teachers misinterpret mixed evidence in their own favor. Just like humans generally.

I don't expect the world to revolve around me or my kids - and lashing out at touchy-feely people is hard because they're so nice. Still, as we economists emphasize, nice people often do bad things. Good intentions are not enough; if you really want to do good, you have to calmly weigh the actual consequences of your actions. You may find drawing posters more fun than reading textbooks, but that's a reflection of your personality type, not a universal law of human nature. Forget these truisms, and you risk being a touchy-feely bull in a china shop - loudly expressing philanthropic sentiments as you trample all over the feelings of hapless studious children.

(10 COMMENTS)

October 31, 2017

Hard Questions About the Protestant Reformation, by Bryan Caplan

For what did these millions die? The standard story, as far as I can tell, is that the Reformation helped free Christianity from the "corruption" of the Papacy. Priests stopped scalping tickets to heaven and supporting their mistresses with the proceeds. Is that supposed to be worth millions of lives? Even if you think that some specific version of Protestantism is the correct religion, earnest marginal thinking is in order. How much closer to salvation is mankind thanks to all the extra earthly suffering the Reformation wrought?

Faced with these sanguinary facts, libertarians can obviously point out that if all Christendom believed in freedom of speech and religion, each and every bloodbath would have been averted. Undeniable, but this dodges the hard question: What should the initially dominant Catholic Church have done differently? We can easily imagine that if Catholics had been less repressive, the cycle of violence would have been contained. Yet that's far from clear: If you read Luther or Calvin, they sure sound like unilaterally violent fundamentalists. And what if the Catholic Church had tried to swiftly and decisively crush the Reformation in the cradle, instead of mixing repression with negotiation and reform? Even if cradle-crushing had failed, it's hard to believe the ensuing violence have been worse than what happened.

The strongest case for the Reformation is simply that there was no other path to our modern, tolerant world. European civilization had two choices: Either stay mired in the grip of medieval superstition and tyranny forever; or endure a century-long bloodbath. But this story is grossly overconfident. Despite the Protestant challenge, the Catholic Church utterly prevailed in countries like France, Spain, and Italy. In the 20th-century, though, it was defeated not by rival religions, but by French, Spanish, and Italian apathy. And you can't help but notice: this defeat by apathy was almost perfectly bloodless. If you object, "None of that could have happened without the Reformation," I say you underestimate the power of apathy.

HT: My sons Aidan and Tristan for bringing some key historical facts to my attention.

(16 COMMENTS)

October 26, 2017

Soonish Success!, by Bryan Caplan

I'm delighted to report that my co-author - Zach Weinersmith - and his co-author - Kelly Weinersmith - have hit the New York Times Bestseller list with their

Soonish:

Ten Emerging Technologies That'll Improve and/or Ruin Everything

. It's a fascinating work, packed with scientific insight, humor, and spot-on comicking.

I'm delighted to report that my co-author - Zach Weinersmith - and his co-author - Kelly Weinersmith - have hit the New York Times Bestseller list with their

Soonish:

Ten Emerging Technologies That'll Improve and/or Ruin Everything

. It's a fascinating work, packed with scientific insight, humor, and spot-on comicking.Substantively, my main reaction is that most of the technologies they explore are still a long way off. Space travel in general, and asteroid mining in particular, won't improve or ruin anything for decades - or centuries. Robin Hanson might find some cause for hope in the chapter on brain-computer interfaces, but even that's not clear. Augmented reality is the only technology on the Weinersmiths' list that's making the world more exciting without delay.

Needless to say, the remoteness of radical technological change is not the authors' fault. They are only the messengers. But their analysis strongly reminded me of Zach's earlier (and also excellent) Science: Ruining Everything Since 1543 . Science dashes natural hope as readily as supernatural hope.

Personally, the one future technology I'm excited about is the driverless car. It didn't get its own chapter in Soonish, but probably should have. Saving tons of time, boredom, and frustration on Earth lacks the romance of soaring to the stars. But I firmly expect to see a world transformed by driverless cars in my lifetime - and for me, the stars are forever out of reach.

That said, my heart continues to skip a beat whenever I hear about a new exoplanet. Space opera is coming, though perhaps not for a few millennia...

(2 COMMENTS)

October 24, 2017

Econ as Anatomy, by Bryan Caplan

1. Formulate a hypothesis.

2. Run an experiment to test the hypothesis.

3. Tentatively accept your hypothesis if the experiment works; otherwise, go back to Step 1.

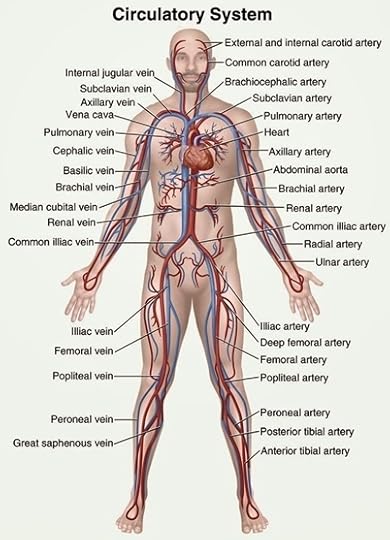

This story isn't entirely wrong; genetics really does begin with Mendel's plant hybridization experiments. If you thoroughly peruse a typical biology textbook, however, much of the content isn't based on experiments. Take anatomy. Do biology textbooks teach students about the circulatory system by describing experiments? No. Instead, they present and discuss a tidy diagram like this:

Are the textbooks glossing over a pile of experiments from which these diagrams derive? Again, as far as I can tell, no. These diagrams are based not on experiments, but on something totally different: painstaking observation. We don't know the heart pumps blood because we randomly assigned half the animals in a sample to have their hearts removed. We know the heart pumps blood because a bunch of smart people looked. The same goes for a vast body of anatomical truths. Where's the experiment testing the hypothesis that the stomach digests food? Or the experiment testing the hypothesis that biceps attach to the radius in the forearm?

Are the textbooks glossing over a pile of experiments from which these diagrams derive? Again, as far as I can tell, no. These diagrams are based not on experiments, but on something totally different: painstaking observation. We don't know the heart pumps blood because we randomly assigned half the animals in a sample to have their hearts removed. We know the heart pumps blood because a bunch of smart people looked. The same goes for a vast body of anatomical truths. Where's the experiment testing the hypothesis that the stomach digests food? Or the experiment testing the hypothesis that biceps attach to the radius in the forearm?My point, of course, is not to criticize biology but to understand it. Naive philosophers of science notwithstanding, biology is packed with useful non-experimental knowledge. In principle, you could experimentally remove animals' stomachs and show that digestion stops. But you could use the same method to confirm the hypothesis that the brain digests food, because removing the brain also leads to the cessation of digestion (not to mention death). And in any case, what's the point of these experiments? The prevailing descriptive approach already provides fine answers. Methodological purists who cry, "Science is experimentation" aren't just silly. If we took their dogmas seriously, we'd have to throw away a vast body of precious knowledge.

The contrast between rhetoric and reality is even stronger in my own field: economics. Economists are vocal proponents of the simplistic scientific method. If they can't present their work as experimental, they strive to label it "quasi-experimental." But if you read an introductory economics text, virtually none of the content is based on experiments. Instead, good economics texts are packed with truisms based on calm observation of humanity: incentives change behavior, trade is mutually beneficial, supply slopes up, demand slopes down, excess supply leads to surpluses, excess demand leads to shortages, externalities lead to inefficiency. These lessons are as undeniable as "the heart pumps blood" and "the stomach digests food." But they're nevertheless supremely insightful and useful. Designing social institutions without considering incentives is as absurd trying to stuff food down people's lungs.

But haven't economists learned quite a bit from experimentation? Of course; my own department is full of experimental economists. My point is that economics, like biology, is packed with precious non-experimental knowledge, too. It's still science; indeed, it's some of the best science ever done. We shouldn't let the genuine triumphs of the experimental method overshadow the rest of the field. And we should staunchly resist anyone who uses methodological dogmas to veto well-established truths - or selectively pretend they don't exist.

Whether you're in biology or economics, writing textbooks won't get you tenure. But the non-experimental knowledge contained within these textbooks could easily be worth more than all the experimental papers published in their respective field the last fifty years. What's the final verdict? For biology, I'm happy to defer to biologists. For economics, however, I've been around long enough to confidently rule in favor of the textbooks.

(6 COMMENTS)

October 23, 2017

Students for Liberty Open Borders Debate: My Opening Statement, by Bryan Caplan

RESOLVED: The United States should Pursue a Policy of Open

Borders.

1. Under open borders, all human beings, regardless of

citizenship, are free to work for willing employers, rent from willing

landlords, and buy from willing vendors.

It's a simple deduction from the basic libertarian principle that

government should not interfere with capitalist acts between consenting adults.

2. The only principled libertarian objection to this

is that the citizens of each country are its rightful owners, so they're

entitled to regulate migration as they see fit.

3. But if you

believe this, there is no principled libertarian objection to any act of government: You can't move

into my house without my consent, but you also can't open a store in my house

without my consent, practice your religion in my house without my consent, preach

libertarianism in my house without my consent, or live in my house without

paying me all the rent I demand. If

citizens are the rightful owners of the country, they have every right to

regulate and tax any aspect of life they like.

4. Fortunately, the

belief that citizens are countries' rightful owners is crazy. The social contract is an utter myth. Contracts require unanimous consent, and no

country has ever had unanimous consent.

5. Of course, most

libertarians - including me - grant that if the consequences of specific libertarian

policies are terrible, we should make an exception. It's a big tent; you don't have to be a strict

libertarian on everything to qualify

as a libertarian. But open borders is not a case where an exception is

justified.

6. Why not? For starters, we should remember that

preventing someone from moving to his preferred country is not a minor

inconvenience like a parking ticket.

It's a severe act of

government coercion. Imagine you could

either be stuck in Haiti for the rest of your life, or be literally enslaved

with probability x. What value of x

makes you indifferent? 10%? 20%? 30%? I'm not saying immigration restrictions are

as bad as slavery; but if for the billions born in places like Haiti, our

restrictions are at least 10% as bad as slavery.

7. What about the

broader effects of immigration? Standard

economic estimates say that open borders would have massive economic benefits - roughly DOUBLING global

production. How? By moving billions of workers from countries

where their labor produces little to countries where their labor produces a

lot. Just look at how much a Haitian's

wages rise the day he arrives in Miami.

8. What about

fiscal effects? Milton Friedman famously

warned that "You cannot simultaneously have free immigration and a welfare

state." But I've looked closely at

the numbers, and Friedman was just

wrong. If you're curious, check out the

latest National Academy of Science estimates.

9. What if

immigrants come and vote for statist policies?

I've looked at the numbers.

Immigrants are more economically liberal and socially conservative than

natives, but the differences are modest, and immigrants don't vote much

anyway. And immigrants are much more

libertarian than natives on one important dimension: support for free

immigration. Today's immigrants are much more Democratic than natives,

but if you ever thought that Democrats were dramatically worse for freedom than

Republicans, I hope the last year has changed your mind.

10. I generally

avoid poetry, but today I'll make an exception.

The government decrees that fellow human beings can't live or work here without

proper papers - papers that are almost impossible for most people on Earth to

ever obtain. It treats them as criminals

for terrible offenses like shining shoes on the streets of Miami or picking

fruit in the fields of California. If

libertarians won't stand up for the rights of these literally oppressed people,

we stand for nothing and we are nothing.

October 19, 2017

Resentment Not Hate, by Bryan Caplan

I say both sides are wrong. Full-blown "hate" is indeed a rare motive. But that hardly means that political actors are well-intentioned. The emotional spectrum is wide. And the emotion I routinely see in politics is not hatred, but its milder cousin: resentment. Normal people don't want to literally destroy their political opponents. But when they mentally picture them, they feel distaste. And when they mentally picture their opponents defeated - or just aggravated - their normal reaction is what the Germans call Schadenfreude. Literally, that's "shameful joy" - pleasure derived from the pain of others.

Doesn't well-meaning political disagreement exist? Sure, but it's a laborious motivation. First, you have to carefully listen to what your opponents say. Then you have to study both sides of the issue, weighing arguments and counter-arguments. And the whole time, you have to be careful not to make the disagreement personal.

Disagreement based on resentment, in contrast, comes naturally. Resentment requires no effort; it comes to you. And once it fills your soul, it swiftly (though inaccurately) answers all your questions. Who's wrong? Those I resent. Who's bad? Those I resent. Who stands in the way of all good things? Those I resent. Am I a bad person for hating them? Of course not, because I don't hate them. But I deeply resent them for slandering me as a hater!

Critics of my Simplistic Theory of Left and Right often assume I'm attributing hatred to both sides of the political spectrum. But as I've said before, I think true hatred is rare. My claim, rather, is that both sides are driven by contrasting resentments. What unifies the left is resentment for the market. What unifies the right is resentment for the left. Indeed, every successful political group begins with easy-to-resent enemies: foreigners, the rich, corporations, Muslims, Jews, blacks, whites, Catholics, or Protestants. It's not profound, but search your feelings - and the feelings of those you encounter.

Back in 1966, Lyndon Johnson said, "[W]ar is always the same. It is young men dying

in the fullness of their promise. It is trying to kill a man that you do

not even know well enough to hate." Beautiful poetry, but exactly wrong. Negative emotions do not require knowledge; negative emotions are the great substitute for knowledge. And in politics, that substitute is almost all most human beings ever bother to have.

(7 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers