Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 74

November 29, 2017

Why It Matters Whodunit, by Bryan Caplan

First, the number murdered.

Second, the group identity of the murderer.

And not necessarily in that order. Whenever a mass murder pops up in the news, many viewers hasten to find out whodunit - where "whodunit" isn't a person, but an affiliation. Is the murderer a Muslim? A non-Muslim who used a gun? A Democrat? Republican? Or just a lone nut who wasn't a "gun nut"?

On the surface, this seems like a depraved reaction to human suffering. After the October 1 Last Vegas shooting, Historian Peter Shulman remarked:

If you're nervously waiting to learn the shooter's religion and voting record before deciding how to react, you don't understand the problem

-- Peter A. Shulman ���� (@pashulman) October 2, 2017

And the great Phil Tetlock responded:

Or "if you're nervously waiting to learn the shooter's religion and voting record before deciding how to react," you are part of the problem https://t.co/SgdIEBwF2o

-- Philip E. Tetlock (@PTetlock) October 2, 2017

On reflection, though, whodunit is tremendously important. Why? Because in our society, the routine reaction to mass murder is to try to punish millions of innocent people. If the murderer is a Muslim, the public want to punish millions of peaceful Muslims by depriving them of the right to visit or live in the U.S. If the murderer is a non-Muslim who used a gun, the public want to punish millions of innocent gun-owners by making it harder for them to buy and sell firearms. If the murderer is a Democrat, Republicans try to paint millions of innocent Democrats as sympathizers. If the murderer is a Republican, Democrats try to paint millions of innocent Republicans as sympathizers. Even if the murderer is apolitical and didn't use a gun, many want to punish innocent disturbed people by easing standards for involuntary psychiatric commitment.

As I wrote the last paragraph, I could already hear the voices in your head saying, "Innocent members of group X? Don't make me laugh!" and "Innocent members of group X? Well, too bad for them." Maybe, but let's think it through. If you accept the slogan, "Guns don't kill; people do," what's wrong with the slogan, "Islam doesn't kill; people do"? If you respond, "Guns don't kill; people with guns do," what's wrong with, "Islam doesn't kill; people inspired by Islam do"? The parallels are clear, no?

You could respond, "Collective punishment isn't fair, but it works." But I almost never hear anyone say such things. Why not? Because dehumanizing the enemy is important for political victory, and activists want victory. And in any case, the moral objections to collective punishment are so compelling most people would rather dodge them than confront them.

In a just society, mass murderers' group identity wouldn't matter. Suicidal murderers would escape punishment, as they always do. The rest would be tried and punished like any other criminal. But sadly, our society refuses to hew to the path of justice. If a mass murderer cheats the hangman, we're still out for blood. Who's blood? Well, whodunit? Let's get them.

As usual, I greatly sympathize with Tetlock's perspective. What kind of a person hears about a mass murder and says, "Whew! At least the perp is on the other side"? (Or even "Heh heh. This could be our big chance!") But the fundamental vice isn't basing your reaction on the identity of the murderer. After all, some collective punishments are likely to be worse than others. The fundamental vice is support for collective punishment itself.

(7 COMMENTS)

November 28, 2017

Ideological Turing Test: Case Against Education Edition, by Bryan Caplan

First, roll a d20 (20-sided die) to determine the topic:

1. What was school like for you personally?

2. Why does so much education seem to irrelevant in the real

world?

3. "Locked-in Syndrome"

4. Transfer of Learning

5. Ability Bias

6. IQ testing, U.S. law, and the labor market

7. The sheepskin effect

8. Malemployment

9. Employer learning

10. Human capital, signaling, and ability bias: What's the

correct breakdown?

11. What's the selfish return to education?

12. What's the social return to education?

13. What's the best reason to go to college?

14. What's the best reason not to go to college?

15. How much should government support education?

16. What kind of education should government support?

17. Social Desirability Bias

18. Child labor

19. Education as a merit good

20. Is education good for the soul?

Then, roll a d10 (ten-sided die) to determine the Perspective.

1. Bryan Caplan

2. David Card

3. Tyler Cowen

4. Fabian Lange

5. Eric Hanushek

6. James Heckman

7. Paul Krugman

8. Greg Mankiw

9. Barack Obama

10. Random GMU undergrad

The goal, as usual, is to accurately mimic the Perspective on the Topic. Getting students to participate is normally like pulling teeth, but 15% of my class grade is based on participation. So perhaps we'll see fireworks...

(1 COMMENTS)

November 27, 2017

Consciousness is All-Important: The Case of Signaling, by Bryan Caplan

The Hansonian heart of the matter:Many people (including me) claim that we eat food and drink water

because without nutrition and fluids we would starve and dehydrate.

Imagine this response:No, people eat food because they are

hungry, and drink water because they are thirsty. We don't need abstract

concepts like nutrition and dehydration to explain something so

elemental as following our authentic feelings and desires.Yes hunger and thirst are direct proximate causes of eating and

drinking. But we are often interested in finding more distal

explanations of such proximate causes. So almost no one objects to the

nutrition and dehydration explanations of eating and drinking.

However, one of the most common criticisms I get about signaling

explanations of human behavior is that we are instead just following

authentic feelings and desires.

I'm an economics professor, and the vast majority of economic papers

and books that offer explanations for human behaviors don't bother to

distinguish if their explanations are mediated by conscious intentions

or not. (In fact, most papers on any topic don't take a stance on most

possible distinctions related to their topic.) Economics are in fact

famously wary (too wary I'd say) of survey data, as they fear conscious

thoughts can mislead about economic behaviors.

Yet I've had even economics colleagues tell me that I should take

more care, when I point out possible signaling explanations, to say if I

am claiming that such signaling effects are consciously intended. But

why would it be more important to distinguish conscious intentions in

this context, compared to the rest of economics and social science?

I say the challenge in Robin's final sentence is easily answered: Conscious intentions are all-important for the welfare analysis of signaling. Standard signaling models assume that people dislike sending the signal. It is this assumption that implies that signaling equilibria are highly inefficient - or even full-blown Prisoners' Dilemmas. If people enjoyed signaling, in contrast, signaling equilbria could easily be ideal. What superficially appears to be a vast zero-sum game turns out to be fine because the players like playing the game.

So why don't economists clearly acknowledge the centrality of conscious desire when they apply signaling models to the real world? Because we usually focus on cases where most people plainly don't enjoy sending the signal. When I wrote The Case Against Education, I definitely double-checked this fact; but I probably wouldn't have even launched the project if I'd spent a lifetime inside classrooms packed with jubilant learners.

Deeper point: I say that hunger and thirst - not nutrition and hydration - often are the real reason why people eat and drink. How can we know? Give people a choice between, say, flavor and nutrition - and see which they choose. Many will plainly stuff themselves with tasty food they know to be unhealthy. The same goes, of course, for sex and reproduction. While people occasionally have sex for reproduction, most take considerable effort to have sex without reproduction. Desire for sex isn't just the proximate cause of sex; it is often the ultimate cause as well.

On some level, I'm confident that Robin agrees with me. As he correctly pointed out over today's lunch, his new Elephant in the Brain points out numerous conflicts between what we say we like and what we actually choose to do. What Robin still misses, though, is that (lack of) conscious desire is the magic ingredient that makes signaling worthy of our attention. True, if people thoroughly enjoyed signaling, there could still be inefficiencies at the margin; just because you love a game doesn't mean you love the last hour of play. But it's the mountain of inframarginal suffering that makes signaling a massive blight on our economy and society.

(2 COMMENTS)November 22, 2017

International Adoption: The Personal Side, by Bryan Caplan

When the moment of truth came, my name was called, I entered theDespite this, international adoption has become less common. And governments around the world are to blame:

room, and a Chinese official plopped a baby into my arms. I braced

myself, and -- nothing happened. She didn't cry. She didn't scream. She

just held onto my shirt with her tiny fists and stared up at my face. To

me it was as if we had been together since the moment of her birth.

[...]

Today, my daughter is a freshman in high school. She spends too much

time on Instagram but is killing it in her classes. And what about our

giving experiment? In truth, I don't know or care what my daughter has

done for my income or health. But my happiness? It spikes every time she

looks at me and I remember the magic day we met.

Back in the United States with our new daughter, Ester and I felt we

were part of a foreign adoption movement. We were sure that enlightened

public policy would continue to loosen regulations, which would make for

more and more miracles like ours. Blended international families of

choice were the wave of the future, we thought, and a reflection of an

increasingly shared belief in a radical solidarity that transcended

borders and biology.We were wrong. The year we adopted turned out to be the high-water

mark in foreign adoptions and the number has dropped ever since. By 2016

it had fallen 77 percent from its peak, to 5,372. This is the lowest

total in three and half decades.What happened? The answer is not a lack of need. Indeed, according to

the Christian Alliance for Orphans, there are more than 15 million

children around the world who have lost both of their parents.Part of the reason is the policies of foreign governments, which have

made foreign adoption harder, for both nationalistic reasons and

because of worries about corruption and human trafficking. Our own

government has contributed as well: Foreign adoption plunged all through

the Obama administration as the State Department imposed new hurdles in

the name of curbing abuses, which are a significant worry for parents

adopting from some countries (although not China, where virtually all

the children, like my daughter, were abandoned at birth).Motivated by good intentions or not, these changes have left

thousands of orphans unadopted. This is too high a price to pay for

bureaucratic screw-tightening.

In my family, we have a catchphrase: "I don't think about what could go wrong. I think about what could go right!" It's poetry, of course; I'm full of precaution. But I stand by the spirit of our poem. To take the case of international adoption: We're paranoid about the microscopic risk of accidentally snatching a poor family's wanted baby - and barely cognizant of the fantastic opportunity regulation snatches from the hands of orphans around the world. Social Desirability Bias - and the demagoguery it fosters - is not only mindless, but heartless.

P.S. Happy Thanksgiving to the Brooks family and to all of you!

(4 COMMENTS)

November 21, 2017

Answer These Questions About the Reformation, by Bryan Caplan

If you've got your own answers to some or all of the questions, please share in the comments.

The Protestant Reformation

1. Why did the Protestant Reformation happen? Standard story or more to it?

2. Largest positive effects of the Reformation?

3. Largest negative effects of the Reformation?

4. Does the corruption of the Catholic church justify the actions of Protestant militants?

5. Calvin (double predestination) vs Luther (single predestination), which has the superior interpretation of the Augustinian tradition? Is either right according to the Bible?

6. Although Martin Luther was early on against violence towards Catholics, he later reversed his position. Why?

7. Does the brutality of John Calvin's theocratic regime in Geneva render his teachings immoral? To what extent can the murders committed by the founder of a religion and his early followers be used to discredit the idea that said religion is one of peace?

8. Of the wars caused by the Protestant Reformation, to what extent can they be blamed on political motivations rather than religious ones?

9. When John Knox wrote his The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, did he essentially argue that no form of government ruled by a woman is legitimate?

Other

1. How powerful is hindsight bias (the tendency to believe that certain events which happened were inevitable) among historians? Should people stay away from calling historical events inevitable?

2. "Historical relativism." Do you agree with it?

3. Baron d'Holbach wrote: "All religions are ancient monuments to superstition, ignorance, and ferocity; and modern religions are only ancient follies rejuvenated." To what extent was he right?

4. On the (earthly) net, would it have been better (measured by the quality/quantity of human lives) if no organized religion had ever existed?

(10 COMMENTS)

November 20, 2017

The Ideological Turing Test in 3 Minutes, by Bryan Caplan

(2 COMMENTS)

November 16, 2017

A Vast But Dwindling Reservoir of Nativism, by Bryan Caplan

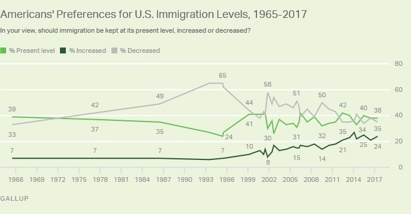

Though preventing illegal immigration was one of the president's keyIf you look at the numbers, however, they've been quite steady for the last five years. We're not living in a period of rising hostility to immigration. We're not living in a period of rising support for immigration. We're living in a period of stable but relatively high support for immigration. The numbers speak:

campaign promises, the general desire to decrease immigration is near

its historic low in Gallup's trend over more than half a century.

If public support for immigration is so high, why has political opposition become so vocal? Because public support for immigration, though relatively high, remains absolutely low. And that's all it takes for anti-immigration demagoguery to work. The real puzzle isn't, "Why did Trump take a strong anti-immigration stand in 2016?" but "Why doesn't every presidential candidate take a strong anti-immigration stand in every election?" And the obvious solution to this puzzle is elite-on-elite pressure: elites are more cosmopolitan than the masses - and shame fellow elites who dissent. Trump won by being the sort of elite who treats elite shame as a badge of honor.

If public support for immigration is so high, why has political opposition become so vocal? Because public support for immigration, though relatively high, remains absolutely low. And that's all it takes for anti-immigration demagoguery to work. The real puzzle isn't, "Why did Trump take a strong anti-immigration stand in 2016?" but "Why doesn't every presidential candidate take a strong anti-immigration stand in every election?" And the obvious solution to this puzzle is elite-on-elite pressure: elites are more cosmopolitan than the masses - and shame fellow elites who dissent. Trump won by being the sort of elite who treats elite shame as a badge of honor.Of course, you could flatly declare that polls are meaningless, and insist that "real" public opinion has indeed turned against immigration. But this is mere circular reasoning. There are endless ways to explain Trump's victory. And the best theory is that Trump was a maverick who defied elite norms to tap into a vast but dwindling reservoir of nativism.

P.S. When I first became interested in the immigration issue in the mid-90s, support for "more immigration" had been stable at 7% for decades. Since then, my eccentric view has more than tripled in popularity. I still doubt immigration is the next marijuana, but I'm mildly hopeful. Who knows, maybe we're just one fine graphic novel away from freedom!

(5 COMMENTS)

November 15, 2017

All Roads Lead to Open Borders: Slides, by Bryan Caplan

P.S. Comments welcome.

(3 COMMENTS)

November 14, 2017

Why Question the Protestant Reformation?, by Bryan Caplan

A

reader asked me, "Would you mind clarifying exactly what your takeaway

message was in your Reformation post?" I'm happy to oblige.

Popular views about the Protestant Reformation are absurdly sugarcoated. It's tempting for libertarians to jump on this sugarcoating bandwagon and praise the Reformation as a triumph of religious freedom. But given the staggering body count - not to mention the violent fundamentalism of the leading Protestant reformers - it's actually a telling counter-example to libertarian optimism. Despite all its oppression, "corrupt" pre-Luther Catholic Europe was far freer than the multilateral bloodbath that succeeded it.

So how's a thoughtful libertarian to respond? Leading possibilities:

1. Libertarian absolutism. The Protestant Reformation was a disaster, but there's still an absolute duty to leave religious dissenters alone until they actually start violating the rights of innocent people.

2. It could have been worse. Many millions were killed, but even more would have been killed under continuing Catholic hegemony.

3. In the long-run, it was worth it. Despite a century of horrors, Luther and Calvin unwittingly built the foundations of modern freedom.

4. An exception to religious toleration was warranted. The consequences of the Reformation were so godawful that the Catholic Church (or anyone else) would have been justified in preemptively coercively suppressing it before it endangered the peace of Europe.

5. Libertarian presumptivism. While the Reformation turned out to be a disaster, people at the time could not have foreseen the horrors with sufficient certainty to overturn the libertarian presumption in favor of religious freedom.

Ultimately, I believe #5, but #4 is my second choice.

P.S. Ilya Somin seems to hold a mix of #2 and #3.

(2 COMMENTS)

November 13, 2017

All Roads Lead to Open Borders: An Advance Look, by Bryan Caplan

At Wednesday's Public Choice Seminar, I'm giving a sneak peak at my next next book,

All Roads Lead to Open Borders: The Ethics and Social Science of Immigration

(co-authored with Zach Weinersmith, creator of Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal).

At Wednesday's Public Choice Seminar, I'm giving a sneak peak at my next next book,

All Roads Lead to Open Borders: The Ethics and Social Science of Immigration

(co-authored with Zach Weinersmith, creator of Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal). This work in progress is a non-fiction graphic novel. If you have no idea what that is, never fear. My talk opens with an introduction to the genre, then presents the substance of the book. I'll also share some of my favorite drawn pages at every stage of development: from previsualizations to pencils, inks, and colors.

The seminar is open to the public, as always.

(3 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers