Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 77

September 25, 2017

Milgram's "Obedience to Authority" Replicates, by Bryan Caplan

First, he supposedly showed that most Americans would shock a total stranger to death because an authority told them to do so.

Second, his experiment was widely perceived as emotionally abusive - so widely, in fact, that Milgram inspired the strict rules that now govern human experimentation. These rules are allegedly so onerous that Milgram's experiment can never be replicated.

It's an odd situation: one of the most famous psychological experiments - an experiment that changed the way people think about human nature - effectively prevented itself from ever being doubly-checked.

Recently, though, I was surprised to discover that Milgram's famous experiment was re-done in 2009! How is this even possible given modern regulations? Experimenter Jerry Berger explains his approach in American Psychologist:

The author conducted a partial replication of Stanley Milgram's (1963, 1965, 1974) obedience studies that allowed for useful comparisons with the original investigations while protecting the well-being of participants. Seventy adults participated in a replication of Milgram's Experiment 5 up to the point at which they first heard the learner's verbal protest (150 volts). Because 79% of Milgram's participants who went past this point continued to the end of the shock generator's range, reasonable estimates could be made about what the present participants would have done if allowed to continue.In other words, since the vast majority of people willing to shock a protesting confederate are also willing to shock an unconscious confederate to death, there's no need to actually continue to the final, gruesome level. You can run almost all of Milgram's original experiment without ever bringing the subjects face-to-face with their own extreme moral turpitude.* Berger continues:

I took several additional steps to ensure the welfare of participants. First, I used a two-step screening process for potential participants to exclude any individual who might have a negative reaction to the experience. Second, participants were told at least three times (twice in writing) that they could withdraw from the study at any time and still receive their $50 for participation. Third, like Milgram, I had the experimenter administer a sample shock to the participants (with their consent) so they could see that the generator was real and could obtain some idea of what the shock felt like. However, a very mild 15-volt shock was administered rather than the 45-volt shock Milgram gave his participants. Fourth, I allowed virtually no time to elapse between ending the session and informing participants that the learner had received no shocks. Within a few seconds of the study's end, the learner entered the room to reassure the participant that he was fine. Fifth, the experimenter who ran the study also was a clinical psychologist who was instructed to end the study immediately if he saw any signs of excessive stress. In short, I wanted to take every reasonable measure to ensure that the participants were treated in a humane and ethical manner.This meticulous design won Berger a green light from human subjects review. So what did he discover? Milgram replicates nicely:

The percentage of participants who continued the procedure after pressing the 150-volt switch was examined. As shown in Table 2, 70% of the base condition participants continued with the next item on the test and had to be stopped by the experimenter. This rate is slightly lower than the percentage who continued beyond this point in Milgram's comparable condition (82.5%), although the difference fell short of statistical significance...How Berger and Milgram's results compare:

Can we properly rely on the truncated version of the experiment? Yes.

Can we properly rely on the truncated version of the experiment? Yes.I cannot say with absolute certainty that the present participants would have continued to the end of the shock generator's range at a rate similar to Milgram's participants. Only a full replication of Milgram's procedure can provide such an unequivocal conclusion. However, numerous studies have demonstrated the effect of incrementally larger requests. That research supports the assumption that most of the participants who continued past the 150-volt point would likely have continued to the 450-volt switch. Consistency needs and self-perception processes make it unlikely that many participants would have suddenly changed their behavior when progressing through each small step.Intriguing extension:

seeing another person refuse to continue. In novel situations such as Milgram's obedience procedure, individuals most likely search for information about how they are supposed to act. In the base condition, the participants could rely only on the experimenter's behavior to determine whether continuing the procedure was appropriate. However, in the modeled refusal condition, participants saw not only that discontinuing was the option selected by the one person they witnessed but that refusing to go on did not appear to result in negative consequences. Although a sample of one provides limited norm information, it is not uncommon for people to rely on single examples when drawing inferences. Nonetheless, seeing another person model refusal had no apparent effect on obedience levels in the present study.I'm glad to see prominent psych experiments face the harsh test of replication. But the same biases that lead to the over-publication of shaky results (positive findings are more exciting than negative findings) also lead to one-sided publicity for failed replication attempts (debunking is more exciting than confirmation). When we first hear about Milgram's original findings, most of us are incredulous. But in the end, it looks like Milgram was correct. With a little high-status prodding, the typical person is ready and willing - though not eager - to do great evil.

* Berger also approvingly cites Milgram's defense of his original design: "In his defense, Milgram (1974) pointed to follow-up questionnaire data indicating that the vast majority of participants not only were glad they had participated in the study but said they had learned something important from their participation and believed that psychologists should conduct more studies of this type in the future."

(6 COMMENTS)

September 21, 2017

Left and Right: A Socratic Dialogue, by Bryan Caplan

Socrates: Quite an intellectual journey, my friends.

Pericles: Indeed, I can't believe how much I've learned in so short a time.

Leonidas: Well, I've learned a lot. Pericles seems dumber than ever.

Socrates: Gentlemen, please - let's be civil. As you know, I'm baffled by your sympathy for either of these strange schools of thought. In fact, I struggle to figure out what even defines them.

Pericles: It's not so hard. Leftists like me care about everyone. Rightists like Leonidas only care about people like themselves.

Leonidas: [harumphs] You don't "care about everyone." You only care about people on your side - and you expect the rest of us to foot the bill.

Socrates: And who exactly is on your side?

Pericles: I don't know what Leonidas is talking about. Everyone counts in my book.

Leonidas: Really! How about people who cherish the traditional family? Traditional religious believers? Rural whites? Cops? Front-line soldiers?

Pericles: This identity politics game you're playing is only an attempt to distract people from the real issues: inequality, corporate power, structural oppression.

Leonidas: Yeah, yeah. Your virtual signaling is only an attempt to distract people from the real issue: liberals like you run government half the time and culture all the time. No wonder the world gets more leftist with every generation.

Socrates: [sigh] Since you two seem to have lost the ability to converse with each other, perhaps you'll let me direct the conversation?

Pericles: Fine.

Leonidas: Whatever.

Socrates: Very well. One common view is that leftists favor a larger role for government, while rightists favor a smaller role for government.

Pericles: Sure, because only government - rightly guided - can address the real issues of inequality, corporate power, and structural oppression.

Leonidas: I guess some rightists favor smaller government, but most of us are just pragmatists. The military is definitely "big government," and if the whole government worked as well as the military, I'd be thrilled. When I actually looked over government budgets, I discovered lots of big programs that are well worth the cost: Social Security, Medicare, education, police, and much more.

Socrates: I see. Another common view is that the left cares more about the poor, and the right cares more about the rich.

Pericles: More or less. I don't intrinsically care less about the rich; I just think they already get a lot more than they need or deserve.

Leonidas: I don't know any rightist who says, "We've got to stand up for the rich." I care about middle and working class people who play by the rules. If we can help them by taxing the rich more, great. But I don't trust leftists to do that. When they say, "Let's tax the rich to help the poor," they mean, "Let's tax everyone who plays by the rules to help everyone who doesn't."

Socrates: How about the theory that the left is heavily guided by smart, well-educated, reality-based thinkers, while the right follows the lead of flamboyant demagogues?

Pericles: There's little doubt that leftists dominate academia, the media, and science, especially the highest levels. Leading leftists disproportionately come from these well-educated fields. Are they especially "smart" and "reality-based"? I don't know how to prove this to outsiders' satisfaction, but it seems a reasonable inference.

Leonidas: Scientists are great within their specialties, but when they talk politics, I don't see that they know any more than anybody else. The media and the rest of academia seems even worse. They may have lots of book smarts, but they're lacking in common sense.

Socrates: According to a very smart fellow named Scott Alexander, "Rightism is what happens when you're optimizing

for surviving an unsafe environment, leftism is what happens when you're

optimized for thriving in a safe environment." Is he correct?

Pericles: I don't think we're in a "safe environment"! The world is a lot richer than it was in ancient Greece, but there's still pervasive insecurity due to inequality, corporate power, and structural oppression.

Leonidas: And I think the modern environment is pretty safe - as long as you follow the rules. Or at least that's how it used to be. People like Pericles feel like they can make up the rules as they go along.

Socrates: So what's the gravest danger facing society?

Pericles: Climate change. Global capitalism is slowly cooking the planet.

Leonidas: I say: Islamofascism. Though I'm tempted to respond "leftists," because they're the ones who won't let us decisively address this looming danger.

Socrates: Another really smart guy named Robin Hanson argues that left/right strife reflects a primordial forager/farmer conflict. A summary, if you'll bear with me:

Pericles: I'm a big fan of dialogue, but not because I feel "safe." As I said, I think the world faces serious - and maybe even existential - problems. We need dialogue because it's the only viable way to wrest control of our society and our world back from moneyed interests.And here is the key idea: individuals vary in the thresholds they use

to switch between focusing on dealing with issues via an

all-encompassing norm-enforcing talky collective, and or via general

Machiavellian social skills, mediated by personal resources and allies.

Everyone tends to switch together to a collective focus as the

environment becomes richer and safer...People who feel less safe are more afraid of changing whatever has

worked in the past, and so hold on more tightly to typical past

behaviors and practices. They are more worried about the group damaging

the talky collective, via tolerating free riders, allowing more distinct

subgroups, and by demanding too much from members who might just up and

leave. Also, those who feel less able to influence communal discussions

prefer groups norms to be enforced more simply and mechanically,

without as many exceptions that will be more influenced by those who are

good at talking.

I argue that this key "left vs. right" inclination to focus more vs less on a talky collective is the main parameter that consistently determines who people tend to ally with in large scale political coalitions.

Leonidas: Leftists' idea of a "dialogue" is them talking down to the rest of us, and shaming anyone who fails to loudly applaud. I'd love to have a series of frank discussions - discussions where the answer is genuinely up for grabs, and pragmatism prevails. And we really need such them, because Pericles is right about level of danger we're all in. He just can't see that people like himself are a big part of the problem.

Socrates: Hmm. Before we move on, let me share one last theory by a noticeably less brilliant thinker named Bryan Caplan. His story: the left is anti-market; the right is anti-left. He elaborates:

1. Leftists are anti-market. On an emotional level, they're critical ofPericles: Rather simplistic.

market outcomes. No matter how good market outcomes are, they can't

bear to say, "Markets have done a great job, who could ask for more?"

2.

Rightists are anti-leftist. On an emotional level, they're critical of

leftists. No matter how much they agree with leftists on an issue,

they can't bear to say, "The left is totally right, it would be churlish

to criticize them."

Socrates: I know. Caplan even calls it the "Simplistic Theory of Left and Right." So is he correct?

Pericles: Of course not. Leftists are rarely "anti-market." We're just highly dissatisfied with the way unregulated markets work.

Socrates: Is the poor performance of unregulated markets an ephemeral coincidence?

Pericles: No, it's a timeless problem. Heard of market failure?

Socrates: Isn't that precisely what an anti-market person would say?

Pericles: I don't want to abolish markets; I just want vigorous government corrections and vigilant government oversight.

Socrates: Caplan never accuses the left of favoring the abolition of the market. He merely claims you feel a lot of resentment toward it.

Pericles: Well, there's lots to resent!

Leonidas: Yea - and I resent the implication that I'm an anti-intellectual rube.

Socrates: Does Caplan so accuse you?

Leonidas: Implicitly. I hate the left, but only because they keep pushing society in the wrong direction.

Socrates: But you seem to embrace many ideas once seen as leftist, like Social Security and Medicare. Why make the sweeping claim that the left "keeps pushing society in the wrong direction" when you embrace so many of their brainchildren?

Leonidas: We're pragmatists on the right. We're happy to adopt left-wing ideas that actually work.

Socrates: What about those small-government rightists we mentioned earlier?

Leonidas: The right is a big tent. I don't agree with them, but they've got some interesting ideas, too.

Socrates: So what unites you and the rightists you disagree with?

Leonidas: [speechless]

Pericles: Perhaps Caplan's half-right. It is hard to name anything Leonidas and Milton Friedman share - except resentment of the left.

Leonidas: Right back at you, Pericles. What do you and Hugo Chavez share - except resentment of the right?

Socrates: Caplan would say they share a resentment of markets. How is he wrong?

Pericles: Chavez may be on the left, but he goes too far.

Socrates: Likely. But Caplan's theory really doesn't speak to who's correct. He's merely proposing a political taxonomy.

Pericles: On the surface, perhaps. But there's a hidden agenda. Caplan's Simplistic Theory insinuates that both left and right are shallow and confused. But only one of our sides has these defects.

Leonidas: For once, I agree. The left is shallow and confused.

Pericles: No, the right is shallow and confused.

Socrates: Friends, you're both tremendously convincing. What you lack in logos, you make up in ethos.

Pericles: [unamused] Very funny, Socrates.

Leonidas: In other words, you agree with Caplan.

Socrates: Agree? Not exactly. As he openly admits, Caplan theory is simplistic. That means "simple to a fault." The Simplistic Theory leaves many big questions unanswered. But... unlike the competition, at least it satisfactorily answers some of my main questions about modern political thought. [shudders]

(5 COMMENTS)

September 20, 2017

The Wonder of International Adoption: High School Grades in Sweden, by Bryan Caplan

To start, imagine growing up in Sweden had zero effect on high school performance. How would the non-Korean adoptees do? As discussed earlier, if the non-Koreans had average IQ for their home countries, their mean IQ would be 84. On the international PISA tests of science, reading, and math, countries with IQs around 84 score about one standard deviation below Sweden.*

When you look at adoptees' actual grades, however, the performance gap is much smaller. Combining males and females, non-Koreans have an average GPA of 2.95, versus 3.24 for regular Swedes. It's not in the paper, but Vinnerljung emailed me the standard deviation: .78. That's a performance gap of only .37 SDs - over 60% less than you would expect from the PISA scores. The gap is even smaller for non-Koreans who were adopted as infants. And as I emphasized in my previous post, we should expect the international adoptees to be below average for their home countries, so the grade gain of growing up Swedish is probably even greater than it looks.

What about the Korean adoptees? They once again do better than regular Swedes, with an average GPA of 3.42.** That's an edge of .23 SDs - almost exactly the PISA gap between Sweden and Korea.

For grades, like IQ, there are two stories to weave. The pessimist can say, "Even in Sweden, non-Koreans' performance in school is well below average." The optimist can say, "Non-Koreans in Sweden do much better than they would have done back home." While both stories are correct, the latter is far more insightful. The fact that non-Koreans underperform in Swedish schools is obvious at a glance. The fact that non-Koreans excel compared to the relevant counter-factual, in contrast, is easy to miss. Wherever you're from, Sweden is a good place to learn.

* The PISA gap is roughly 100 points, and scores are normed to have a standard deviation of 100.

** This slightly overstates Korean performance, because the Korean

adoptees are over two-thirds female, and girls in all groups have higher

GPAs than boys. If you separately compare genders, Korean boys are .18 SDs and Korean girls are .17 SDs above Swedish norms.

(5 COMMENTS)

September 19, 2017

Does Prosperity Make Us Utilitarian?, by Bryan Caplan

Liberalism is what happens when you are optimizing for a safe

environment, and illiberalism is what happens when you optimize for

thriving in an unsafe environment.

Now of course this raises a whole new set of issues. What do I mean

by 'liberalism' and 'illiberalism'? When I say liberalism, I am

including classical liberalism, social democratic liberalism and

neoliberalism. I'm basically referring to utilitarianism. When I say

illiberal, I am referring to a wide variety of non-utilitarian views,

including class warfare (Mao), fascism (Hitler), white nationalism

(Bannon), racism (KKK), reverse racism (SJWs), tribalism (Afghanistan),

religious fanaticism, militarism, etc.

This is deeply puzzling.

First, if "Liberalism is what happens when you are optimizing for a safe

environment, and illiberalism is what happens when you optimize for

thriving in an unsafe environment," are we talking about selfish optimization or social optimization? If the former, then how does being rich make caring about outsiders "selfishly optimal"? If the latter, then it sounds like utilitarianism requires illiberalism in unsafe environments.

Second, classical liberalism, social democratic liberalism, and neoliberalism have all been widely accused of ignoring the interests of wide swaths of the population. Classical liberals and neoliberals allegedly ignore the interests of the poor; social democrats allegedly ignore the interests of taxpayers and entrepreneurs.

Third, most - perhaps all - of what Scott calls "illiberal" views have been defended on utilitarian grounds. See e.g. James Fitzjames Stephen, noted 19th-century conservative utilitarian. You could say, "I'm classifying views based on whether they really maximize total happiness," but then why include three disparate flavors of "liberalism"? They can't all be right.

For utilitarianism to thrive, people need to be comfortable enough to

think of the welfare of others. I believe that 1966 was the period when

whites had the greatest sympathy for the (economic) well-being of

American blacks.

Concern for the welfare of others is part of the utilitarian ethos. But so is sober cost-benefit analysis and, as a corollary, hostility to Social Desirability Bias. 1966 may have been a period of relatively high sympathy for blacks (though probably little for Indochinese), but it was also an era of rampant wishful thinking.

And America's middle class was doing very well in the

mid-1960s. As America became more violent in the late 1960s, and more

troubled by unemployment in the 1970s, some of this sympathy dissipated.

Unless I greatly misunderstand Scott, I think he agrees with me that the middle class is doing much better today than in the mid-60s. So how does this example illustrate the positive effect of prosperity on concern for others?

So I think Bryan's right that the left/right distinction is not as

meaningful as Scott Alexander assumes, but I also think Scott's

intuition led him to something important. I don't know if society is

moving to the left, but I do think it is gradually becoming more

liberal. Is my suggested version an improvement, or not?

I agree that societies that value the utilitarian package - hard-headed pursuit of general happiness - tend to prosper. But I don't see much sign that the reverse mechanism works well. As I originally said, there is plenty of evidence that prosperity makes societies moderate. That blocks radical changes that harm the general welfare (e.g. mass murder), but also blocks radical changes that help the general welfare (e.g. open borders).

PS. Immigration reform was enacted in 1965.

Yes. But the liberalization was accidental!

(4 COMMENTS)

September 18, 2017

The Wonder of International Adoption: Adult IQ in Sweden, by Bryan Caplan

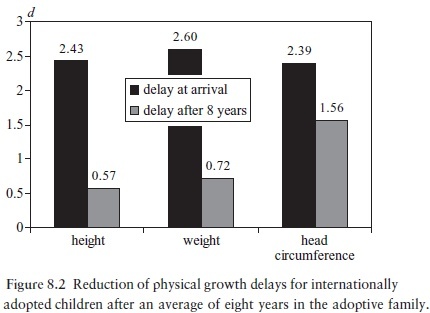

The most important weakness of behavioral genetics, though, is simply that research focuses on middle-class families in First World countries. The results might not generalize. Twin and adoption studies almost never look at people in Third World countries. So you shouldn't conclude that Haitian orphans would turn out the same way if raised in Sweden.During the last month, I've delved much more deeply into this subject. As you might expect, there is a sizable literature on the effects of international adoption. The evidence on physical benefits is strong and clear-cut. Toddlers adopted from the Third World are tragically below normal on height, weight, and head circumference on arrival. (d is effect size in standard deviations). Within eight years, however, these adoptees close about 75% of height and weight deficits and about 35% of the head circumference deficit.

[...]

Twin and adoption research only show that families have little long-run effect inside the First World. Bringing kids to the First World often saves their lives. Over 13 percent of the children in Malawi--the African nation than initially denied Madonna's petition to adopt a four-year-old orphan--don't survive their first five years. And survival is only the beginning. Life in the First World spares children from hunger, disease, and harsh labor, and opens vast opportunities that most of us take for granted. Merely moving an adult Nigerian to the United States multiplies his wage about fifteen times. Imagine the benefit of giving a Nigerian child an American childhood and an American education.

But what about intellectual benefits? Average IQs in Third World countries are quite low - mid-to-high 80s for Latin America, mid-80s for the Middle East, low-80s for South Asia, 70s or even lower for sub-Saharan Africa.

But what about intellectual benefits? Average IQs in Third World countries are quite low - mid-to-high 80s for Latin America, mid-80s for the Middle East, low-80s for South Asia, 70s or even lower for sub-Saharan Africa.Before we turn to the evidence, however, there's a major complication. In the First World, children adopted by smarter parents get somewhat higher IQ scores. Unfortunately, these benefits fade-out by adulthood. Me again:

Twin and adoption research on young children's intelligence always finds nurture effects. The younger the child, the more parents matter. A team of prominent behavioral geneticists looked at major adoption studies of IQ. They found moderate nurture effects for children, versus none for adults. Suppose an adoptee grows up in a family with a biological child at the 80th percentile of IQ. During his childhood, we should expect the adoptee to have a higher IQ than 58 percent of his peers. Nurture effects were largest for the youngest kids under observation, four-to six-year-olds. An average child of this age raised in a high-IQ home will typically test higher than 63 percent of his peers. Not bad--but it doesn't last.The upshot is that measuring the IQs of Third World adoptees when they're children isn't very informative. Even if they show large gains, the gains could easily be fleeting. Instead, we should wait and measure those kids' IQs when they're adults.

I had to read a pile of papers, but in the end, I found what I was looking for. Dalen et al.'s "Educational Attainment and Cognitive Competence in Adopted Men" (Children and Youth Services Review, 2008) looks at Swedish conscripts' cognitive test results for (a) 342,526 non-adopted Swedes, 780 adoptees from South Korea, and 1558 adoptees from other non-Western countries. Subjects were roughly 18 years old when they took the test. At my request, Bo Vinnerljung, one of the authors, shared the nationality breakdown for the "other non-Western" countries: India (21%), Thailand (19%), Chile (13%), Sri Lanka (9%), Colombia (9%), Ethiopia (8%), Ecuador (7%), with the remainder from "a wide mix of small groups, e.g., Poland, Peru, Bolivia, a few from other sub-Saharan Africa countries, and a small group from Mid-East countries including Iran."

Suppose you plug in the most commonly-used estimates of IQ by country, assign each of Vinnerjung's "small groups" equal shares of the remainder, and assume international adoptees are average for their home country. Then if they'd stayed in their birth countries, the non-Western adoptees would have a mean IQ of only 84.

So how smart were these non-Western adoptees at maturity (approximately 18 years old)? Let's normalize the scores so overall Swedish IQ is 99 (a typical estimate), with a standard deviation of 15.* Then non-Western adoptees' average score was 88. Four IQs points may sound modest, but it's one of the biggest environmental effects on adult IQ in the literature.

The real magic happens, though, when we look at the breakdown by age of adoption, provided in this companion paper by Odenstad et al.'s

Other Non-Western IQ by Age of Adoption

Age at Adoption

IQ

0-6 months

90

7-12 months

88

13-18 months

89

19-24 months

89

2-3 years

87

4-5 years

85

7-9 years

76

Since adoptees' biological families are generally underachievers even by Third World standards, the true IQ benefit of adoption at birth is probably even greater than it looks. Adoptees raised by their biological families could easily have had an average IQ of only 80, implying that early adoption eliminated over half their cognitive deficit.*

At this point, you may be asking, "Wait, what about the Korean adoptees?" They did slightly better than regular Swedes, but markedly worse than regular South Koreans (average national IQ: 106). Their results by age of adoption show no clear pattern:

Other Non-Western IQ by Age of Adoption

Age at Adoption

IQ

0-6 months

100

7-12 months

98

13-18 months

106

19-24 months

100

2-3 years

103

4-5 years

97

7-9 years

99

If you're using international adoption data to test the view that international IQ differences are 100% environmental, the contrasting performance of Korean and non-Korean adoptees is bound to be disturbing. Sure, you can blame all remaining gaps on pre-natal environment. But if equalizing a vast array of post-natal experiences leaves a big gap, what makes you so sure that equalizing pre-natal experiences would make the gap vanish?

If you're using international adoption data to test the view that international IQ differences are 100% genetic, however, the performance of the non-Korean adoptees is powerful testimony to the wonder of First World upbringing. Suppose the earliest adoptees are average for their home country. Then growing up in Sweden raises their adult IQs by .4 SDs - 40% of the huge IQ gap between Sweden and adoptees' countries of origin. And since even the earliest adoptees are likely below-average for their home country, the true gain is probably larger still. International adoption doesn't make international IQ gaps vanish, but it plausibly cuts them in half. And remember - unlike classic childhood interventions like Head Start, the gains last into adulthood instead of fading away. What other viable, lasting treatment for low IQ is even remotely as effective?

* It is somewhat tempting to assume that if all of these kids had stayed

with their biological families, the whole sample would look like the 7-9

year-olds - or worse. But we should resist this temptation. Many of

the 7-9 year-old non-Koreans probably grew up in hellish orphanages, which seem noticeably worse for IQ

than the typical Third World home. Furthermore, late adoptees

plausibly had extra developmental problems that partially caused their delayed

adoption.

(4 COMMENTS)

September 14, 2017

A Taste of Bastiat, by Bryan Caplan

Sometimes you hear Texas described as a "low-wage" economy, perhapsTyler's last line is, of course, a Bastiat reference. Read his words, and dwell upon his profundity (and occasional error).

contrasted with the high wages of California. But there are some subtle

wage effects from the Texas approach that often go unnoticed. By

drawing people out of high-rent areas, Texas keeps the lid on land rents

elsewhere, thereby boosting real wages in say San Francisco.

Furthermore, San Francisco employers must pay their workers more, the

more attractive is the "move to Texas" option. So the full positive

effect of the Texas model on wages is considerably higher than you can

see by looking at Texas wages alone. Once again, the distinction

between the seen and the unseen turns out to be relevant.

(0 COMMENTS)

September 13, 2017

Human Smuggling: What If Philanthropists Were in Charge?, by Bryan Caplan

The upshot: While I'm personally strongly in favor of human smuggling to evade unjust immigration laws, I'm ambivalent about human smugglers themselves. What's the ratio of honest outlaws to ruthless predators? This article gives lots of suggestive details, but few usable numbers:

But what's really going on? Well, the UN estimates a bit over a million crossers in 2015, with 3,771 recorded deaths. Even if you think actual deaths are triple the recorded rate, that's roughly a 1% fatality rate. Tragic, but given the level of smuggling and the risks required to avoid detection, it's surprisingly low. I'd definitely take a 1% chance of death to escape Syria, and probably make the same deal to escape 90% of the countries in Africa.People smugglers who offer to

illegally transport people into Europe are advertising their services

openly on Facebook, researchers have found.

Picture and video testimonials from successful

migrants are posted on social media as smuggling operations compete to

be seen as the safest way to enter Europe.Researchers are using this information to analyse the networks behind people smuggling operations in the Mediterranean.

Syrian

communities displaced by the civil war are especially close users of

Facebook. The country had a functional education system before the war

and Syrian migrants have on average a higher level of education and

digital literacy.[...]

The importance of networks and reputations in the free market of

smugglers can been seen in the evidence that Dr Campana had collected.One

recording of a wiretapped telephone call revealed how one people

smuggler asked another how many of the 366 asylum seekers who had died... were his.The wiretap records one of the smugglers berating the other for his lapse safety.

The

other smuggler later began to personally notify the families of the

dead and pay out $5,000 (��3,778) in compensation to salvage his

reputation.

In fact, suppose smugglers were pure philanthropists who only wanted to help people reach Europe alive. There's a clear trade-off between the two goals - the safest routes will also be the most patrolled. So you have to wonder: If philanthropists ran the human smuggling industry, how much lower could fatality rates even fall?

(1 COMMENTS)

September 12, 2017

What's Wrong with the Thrive/Survive Theory of Left and Right, by Bryan Caplan

My hypothesis is that rightism is what happens when you're optimizingScott defends the theory vigorously, but seems most impressed by its ability to explain why "society does seem to be

for surviving an unsafe environment, leftism is what happens when you're

optimized for thriving in a safe environment.

drifting gradually leftward." The more the world thrives, the more the leftist approach genuinely makes sense.

Many people in my circles now seem to take Thrive/Survive Theory as the default position; if it's not true, it's still the story to beat. But to be blunt, I find essentially no value in it. It's not always wrong, but it's about as right as you'd expect from chance. My top criticisms:

1. Unless you cherry-pick the time and place, it is simply not true that society is drifting leftward. On the global level, leftism was mighty from roughly 1917 to 1975 - when the Soviet bloc was still strong and heartily attacked by even more radical leftists like Mao. The triumph of Deng Xiaoping in China started a gradual but massive decline of leftism. The fall of the Soviet bloc was an even sharper and far more rapid crash. These changes echoed throughout the developing world. And while pro-Communist parties never dominated any Western country, the collapse of Communism was a major blow to the ambition and morale of left-wing Western parties and intellectuals.

2. A standard leftist view is that free-market "neoliberal" policies now rule the world. I say they're grossly exaggerating, but there's a lot more evidence for a long-run neoliberal trend than a long-run leftist trend.

3. Radical left parties almost invariably ruled countries near the "survive" pole, not the "thrive" pole. And they generally had little or no sympathy for social liberalism, with brief exceptions (like the first year or so of the Soviet Union). In fact, they punished deviance and dissent far more brutally than the typical traditional monarchy. In the broad history of leftism, Bay Area-type identity politics is simply not very important.

4. You could deny that Communist regimes were "genuinely leftist," but that's pretty desperate. When Communism was a viable political movement, almost everyone - including moderate leftists - saw it as part of the left. An extreme, fanatical part of the left, yes. But very much a part of it.

5 Many big social issues that divide left and right in rich countries like the U.S. directly contradict Thrive/Survive. To take the most obvious case: unwanted pregnancies are much more burdensome - and legal abortion much more valuable - when life itself is insecure. The same goes for the traditional Christian teachings of unconditional love and unconditional forgiveness. If Scott were correct, rightists wouldn't just be pro-choice; they'd literally be pro-abortion for any fetus likely to burden society.

6. Major war provides an excellent natural experiment for Thrive/Survive. Material conditions suddenly get a lot worse; life itself is on the line. What really happens? Almost all countries lurch toward what General Ludendorff termed "War Socialism" - replacing private property and material rewards with state ownership and forced egalitarianism. When war ends, countries tend to back away from these policies - exactly the opposite of what Thrive/Survive Theory predicts. Furthermore, political support for the continuation of egalitarian policies after wars tends to rest on "compensatory" arguments for the masses' wartime sacrifices.

If Thrive/Survive Theory is wrong, what's right? I stand by my Simplistic Theory of Left and Right:

1. Leftists are anti-market. On an emotional level, they're critical ofNote the asymmetry: While leftists are emotionally anti-market, rightists are not generally pro-market. Plenty are mercantilists, nationalists, populists, religious fundamentalists, and folks who find economics boring beyond belief. What these diverse right-wing flavors have in common is not love of laissez-faire, but antipathy for leftists.

market outcomes. No matter how good market outcomes are, they can't

bear to say, "Markets have done a great job, who could ask for more?"

2.

Rightists are anti-leftist. On an emotional level, they're critical of

leftists. No matter how much they agree with leftists on an issue,

they can't bear to say, "The left is totally right, it would be churlish

to criticize them."

My Simplistic Theory intentionally fails to predict lots of details. Why? Because many of the features that Scott sees as quintessentially leftist - such as "freedom of religion, democratic-republican governments, weak gender

norms, minimal family values, and a high emphasis on education and

abstract ideas" - have been neglected or rejected by history's most influential, dyed-in-the-wool leftists. The leftists Scott personally knows may cherish the items on his list. To be frank, though, the leftists Scott personally knows are just a trendy subset of a diverse and enduring movement.

But doesn't prosperity push society in a predictable political direction? Yes, but the direction isn't leftism. It's moderation. In rich societies, left and right make milder demands, and impose milder punishments. Instead of expropriation, they push for taxation. Instead of threatening death, they threaten jail, deportation, fines, or strongly-worded letters. When society is on the brink of starvation, leftists and rightists slaughter each other. When society faces an obesity epidemic, leftists and rightists troll each other on Facebook.

(7 COMMENTS)

September 11, 2017

Case Against Education Updates, by Bryan Caplan

2. This semester, I am designing and teaching a brand-new seminar course on the book. The website in progress for this mixed undergraduate/graduate course is here.

(1 COMMENTS)

September 6, 2017

More Reasons to Read About Religion, by Bryan Caplan

So many religious facts have a very long half-life for their

relevance. Say you learn about how the four Gospels differ -- that's

still relevant for understanding Christian divisions or Christian

theology today. Reading about the Reformation? The chance of that

still being relevant is much higher than if you were reading about

purely secular divisions in internal German or Swiss politics in those

same centuries.

Jews, Buddhists, Hindus, Sikhs, or Muslims? Facts from many

centuries ago still might matter. And the odds are that people a few

centuries from now still ought to read about the origins of Mormonism.

In few other areas do past facts stand such a high chance of remaining relevant for so long.

As an empirical matter, "rationalists" tend not to read so much about

religion, but that is precisely the unreasonable thing to do.

I heartily agree, and have several points to add.

1. Studying religion teaches us a tremendous amount about human psychology: our eagerness to embrace doctrines that outsiders consider nonsense, our pretentious overconfidence and hyperbole, our willingness to oppress and even murder over objectively trivial issues.2. Studying religion also teaches us a tremendous amount about human sociology: our propensity to split into doctrinally-obsessed clergy and angry-sloganizing laymen, our desire to socialize and especially intermarry with co-religionists, our eagerness to dehumanize outgroups.

3. Once you learn these lessons, most secular ideologies start to seem like thinly-veiled religions as well. And I'm not just talking about Marxism. Mainstream liberalism and conservatism fit the same psychological and sociological bill. And yes, so does libertarianism, despite its overrepresentation of bona fide rationalists and individualists. It may be a cliche, but politics is the religion of modernity.

4. While you're at it, read (or re-read) Eric Hoffer's The True Believer . Great stuff, especially for those of us who believe in something.

(5 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers