Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 79

August 1, 2017

Stop Thinking Like a Tourist: Macaulay Edition, by Bryan Caplan

Mr. Southey has found out a way, he tells us, in which the effects of

manufactures and agriculture may be compared. And what is this way? To

stand on a hill, to look at a cottage and a factory, and to see which is

the prettier.

(2 COMMENTS)

July 24, 2017

Caplan in Paris, by Bryan Caplan

I'm speaking in Paris this Thursday for Students for Liberty. Details here.

I'm speaking in Paris this Thursday for Students for Liberty. Details here.P.S. Here's what I thought the last time I was in Paris nine years ago.

(0 COMMENTS)

July 20, 2017

How Conscious Is Your Robot?, by Bryan Caplan

The Experience factor explains 88% of the variance; Agency comes in a remote second, with 8% of the variance. And on the Experience factor, the robot is virtually at 0. Apparently most people (correctly, in my view) don't think he's conscious at all.

The Experience factor explains 88% of the variance; Agency comes in a remote second, with 8% of the variance. And on the Experience factor, the robot is virtually at 0. Apparently most people (correctly, in my view) don't think he's conscious at all.Yet here's how Robin reads the results. He's in blockquotes; my commentary isn't.

I'm also pretty sure that while the "robot" in the study was rated lowHe wasn't just rated "low." He was rated near-zero.

on experience, that was because it was rated low on capacities like for

pain, pleasure, rage, desire, and personality.

Ems, being moreHow badly would the robot's mentality scores have to be to make Robin say the opposite?

articulate and expressive than most humans, could quickly convince most

biological humans that they act very much like creatures with such

capacities.

You might claim that humans will all insist on ratingActually, every living character made out of biochemicals scored at the mid-point or higher on Experience. Respondents rated a dead body higher in Experience than a functioning robot. A dead body! The only creature in the robot's league was God himself, who is also generally not supposed to be made out of biochemicals.

anything not made of biochemicals as all very low on all such

capacities, but that is not what we see in the above survey...

P.S. At this point, I would be willing to bet that if the same study were re-done with an "em" character added, the em would score less than .6 on the Experience factor on a 0-1 scale. Note: .5 is roughly the score of a fetus or someone in a permanent vegetative state. Per my original reservations, however, I would not bet more than $500 at even odds. Robin doesn't care for this bet, but so far we haven't been able to work out anything mutually acceptable.

(1 COMMENTS)

July 18, 2017

Murder: A Socratic Dialogue, by Bryan Caplan

Socrates: A ghastly crime. But why are you telling me?

Glaucon: Because it just happened!

Socrates: So I gathered.

Glaucon: In Corinth! That's only fifty miles away.

Socrates: Should we get inside and bar the door?

Glaucon: [squinting] No. The Persian was killed moments after the attack.

Socrates: Then I repeat: Why are you telling me?

Glaucon: [upset] Because I assumed you would care about the victims!

Socrates: Well, I care a little bit. But I didn't personally know them.

Glaucon: [outraged] You're barely human, Socrates. Everyone else is outraged by this Persian crime. You should be too!

Socrates: Perhaps you're right. But one thing puzzles me.

Glaucon: [calming down] Namely?

Socrates: My friend Pythagoras has calculated the number of innocent people murdered on an average day. Do you know how many that is?

Glaucon: No.

Socrates: Fifty. And the minimum number of recorded daily victims is five.

Glaucon: What a hellish world we live in!

Socrates: Perhaps. Now that you know this, I have to ask: Do you plan to be outraged every day for the rest of your life?

Glaucon: [taken aback] Well, those numbers are pretty bad, but...

Socrates: But what?

Glaucon: Well, life is for the living. I'm not going to be angry and miserable every day just because vile crimes are happening somewhere on Earth. It's a big place, you know.

Socrates: Very wise. But then why did you say I was "barely human" for having the same reaction when you told me about the tragedy in Corinth?

Glaucon: [renewed outrage] That's completely different.

Socrates: Really? Please help me understand how.

Glaucon: Well, we're talking about innocent... [fumbling] What I mean is, it just hap... [dumb-founded]

Socrates: You were going to remind me that the crime is fresh, and the victims were innocent. But you stopped short, because you realized that this is true every day.

Glaucon: [irritated] Yes.

Socrates: Did you think I should be upset simply because our community is temporarily fixated on this specific crime?

Glaucon: No, that would be pretty stupid.

Socrates: And shallow and disingenuous. So I ask you again: Why am I supposed to be distraught about the tragedy in Corinth?

Glaucon: [long pause] Because they victims were fellow Greeks!

Socrates: According to Pythagoras, three Greeks are murdered on an average day. The tragedy of Corinth therefore brings us to our daily average. Do you plan to be angry and miserable every day the number of Greeks murdered equals or exceeds the long-run average?

Glaucon: You're missing the point. The Corinthians were murdered by a treacherous Persian!

Socrates: Ah, I overlooked that critical distinction. So what should outrage us is not murder in general, or murder of Greeks by fellow Greeks, but only murder of Greeks by Persians?

Glaucon: [touchy] Do you think it's funny when a Persian maniac butchers a child with his scimitar?

Socrates: Not in the slightest. But how is that worse than when a Greek maniac murders a child?

Glaucon: Well, maybe it's not worse. But we can do something about the Persian maniacs.

Socrates: We can "do something" about murderers of any nationality, can we not?

Glaucon: [exasperated] Sure. But we can do a lot more about the Persians.

Socrates: Are would-be Persian murderers more easily deterred by punishment?

Glaucon: Probably less, actually.

Socrates: Then what do you mean when you say we can "do a lot more about them"?

Glaucon: Well, if there weren't any Persians here, they wouldn't be able to murder any of us.

Socrates: True enough. So to end Persian murder, we should murder every Persian in Greece?

Glaucon: That's barbarous! No, we should just keep Persians out of Greece.

Socrates: We should exile a vast group for the crimes of a few?

Glaucon: I don't know why you call it "exile." The Persians can stay in Persia.

Socrates: What about Spartans? They're only 10% of the population of Greece, but they commit half the murders.

Glaucon: So?

Socrates: If the Persians should stay in Persia, should the Spartans stay in Sparta?

Glaucon: What a horrible thing to say! Spartans are fellow Greeks!

Socrates: So we shouldn't exile all Spartans for the crimes of a few Spartans?

Glaucon: Absolutely not.

Socrates: But are not the Persians fellow human beings?

Glaucon: I suppose.

Socrates: Why then isn't it just as horrible to advocate collective punishment against Persians as against Spartans?

Glaucon: What part of "Spartans are fellow Greeks" don't you understand?

Socrates: These Spartans seem rather troublesome. Could we just declare they're not Greek anymore, then exile them?

Glaucon: That would be a monstrous injustice.

Socrates: Indeed it would be. But the reason is not that they're fellow Greeks. Who counts as "Greek" is a matter of convention, not justice.

Glaucon: Then why would it be a monstrous injustice?

Socrates: Because Spartans, like Persians, are fellow human beings deserving of just treatment. And that, my dear Glaucon, is no convention.

(13 COMMENTS)

July 17, 2017

Em Bet?, by Bryan Caplan

I'm also pretty sure that while the "robot" in the study was rated lowSince Robin repeatedly mentioned my criticism of his work in this post, I sense this bet is aimed at me. While I commend him on his willingness to bet such a large sum, I decline. Why?

on experience, that was because it was rated low on capacities like for

pain, pleasure, rage, desire, and personality. Ems, being more

articulate and expressive than most humans, could quickly convince most

biological humans that they act very much like creatures with such

capacities. You might claim that humans will all insist on rating

anything not made of biochemicals as all very low on all such

capacities, but that is not what we see in the above survey, nor what we

see in how people react to fictional robot characters, such as from

Westworld or Battlestar Galactica. When such characters act very much

like creatures with these key capacities, they are seen as creatures

that we should avoid hurting. I offer to bet $10,000 at even odds that

this is what we will see in an extended survey like the one above that

includes such characters. (emphasis mine)

1. First and foremost, I don't put much stock in any one academic paper, especially on a weird topic. Indeed, if the topic is weird enough, I expect the self-selection of the researchers will be severe, so I'd put little stock in the totality of their results.

2. Robin's interpretation of the paper he discusses is unconvincing to me, so I don't see much connection between the bet he proposes and his views on how humans would treat ems. How so? Unfortunately, we have so little common ground here I'd have to go through the post line-by-line just to get started.

3. Even if you could get people to say that "Ems are as human as you or me" on a survey, that's probably a "far" answer that wouldn't predict much about concrete behavior. Most people who verbally endorse vegetarianism don't actually practice it. The same would hold for ems to an even stronger degree.

What would I bet on? I bet that no country on Earth with a current population over 10M grants will grant any AI the right to unilaterally quit its job. I also bet that the United States will not extend the 13th Amendment to AIs. (I'd make similar bets for other countries with analogous legal rules). Over what time frame? In principle, I'd be happy betting over a century, but as a practical matter, there's no convenient way to implement that. So I suggest a bet where Robin pays me now, and I owe him if any of this comes to pass while we're both still alive. I'm happy to raise the odds to compensate for the relatively short time frame.

(5 COMMENTS)

July 13, 2017

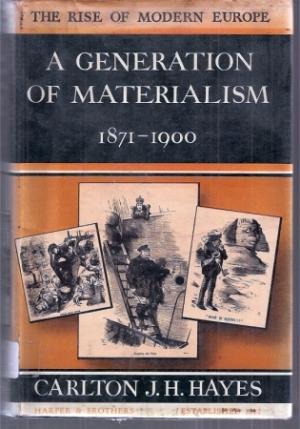

Imperialism in A Generation of Materialism, by Bryan Caplan

I highly recommended Carlton Hayes'

A Generation of Materialism, 1871-1900

. It chronicles a great tragedy. During this period, the economic, technological, and scientific fruits of the Enlightenment reached historic highs. But intellectual appreciation of the Enlightenment rapidly drowned beneath the twin waves of nationalism and socialism - paving the way for World War I, Communism, Nazism, World War II, and the Cold War. This would have been pathetic enough if wise intellectuals were overpowered by the benighted masses. But with few exceptions, contemporary intellectuals led the attack on the Enlightenment - or, more precisely, pretended it never happened. Though Hayes is basically a Wilsonian progressive, his story has an intensely Randian feel.

I highly recommended Carlton Hayes'

A Generation of Materialism, 1871-1900

. It chronicles a great tragedy. During this period, the economic, technological, and scientific fruits of the Enlightenment reached historic highs. But intellectual appreciation of the Enlightenment rapidly drowned beneath the twin waves of nationalism and socialism - paving the way for World War I, Communism, Nazism, World War II, and the Cold War. This would have been pathetic enough if wise intellectuals were overpowered by the benighted masses. But with few exceptions, contemporary intellectuals led the attack on the Enlightenment - or, more precisely, pretended it never happened. Though Hayes is basically a Wilsonian progressive, his story has an intensely Randian feel.A Generation of Materialism is sweeping in scope, but the chapter on imperialism was one of my favorites. Here's one eye-opening passage on the history of imperialism:

[T]he immediately preceding era of Liberal ascendancy, say from the 1840's into the 1870's, had witnessed a marked decline of European imperialism. There had been, to be sure, some spasmodic additions to British India, some scattered efforts of Napoleon III to resuscitate a colonial empire for France, some continuing Russian expansion in central and northeastern Asia. Although China and Japan had been forcefully opened to European (and American) trade, the opening had been for practically everybody on free and equal terms and had been unattended by any considerable expropriation of territory. The surviving farflung British Empire had ceased to be an exclusive preserve for British merchants since the 1840's, and in 1861 France had freely admitted to her colonies the commerce of all nations. In 1870-1871 European colonialism appeared to be approaching its nadir. Gladstone was prime minister of Great Britain, and he was notoriously a "Little Englander." The provisional French government so slightly esteemed the colonies it had inherited that it offered them all to Bismarck at the end of the Franco-Prussian War if only he would spare Alsace-Lorraine.How different the 20th century might have been if Bismarck had accepted that offer!

I first read Hayes in high school, learning European history from his delightful Political and Social History of Modern Europe. In hindsight, he's a precocious proponent of behavioral political economy. Behold:

The actual course of empire - the order in which distant areas were appropriated by European powers - was determined less by design than by chance. Murder of a missionary or trader and consequent forceful intervention might occur anywhere. In some instances, curiously frequent in Moslem countries, native rulers practically invited intervention by living far beyond their means and contracting debts which they were unable to repay... For example, the Khedive Ismail of Egypt, a squat red-bearded gentleman with a passion for ostentation and the externals of European culture, spent half a billion dollars in the twelve years after his accession in 1863, running up the Egyptian public debt from 16 million to 342 million and continuing to borrow money from European bankers at ever more onerous rates... In 1876 he sold his shares of the Suez Canal Company stock to England, and consented to joint supervision of his finances by representatives of England, France, Italy, and Austria... No doubt bankers and investors egged on both the khedive to spend and the English government to collect, but a less prodigal khedive, and one more intelligently concerned with the welfare of his subjects, might have staved off foreign rule. The contemporary Mikado of Japan did.If you want to know what an erudite, opinionated historian thought in 1941 about the period from 1871-1900, this is the book for you!

(0 COMMENTS)

July 12, 2017

Statutory Rape and Availability Bias in Virginia, by Bryan Caplan

Legally, the answer seems to be yes. But what's scary about bad laws is not that they exist, but how they're enforced. There's no point losing sleep over dead letters. So how often does Virginia actually punish youths for statutory rape? This official 2014 report report on crime in Virginia is most illuminating. Key facts:

1. For all of 2014, the total number of minors arrested for statutory rape in Virginia was: 6. Two were 16 years old; the rest were 17 years old.

2. For all of 2014, the total number of non-minors arrested for statutory rape in Virginia was: 104. Of these, 11 were 18 years old, 16 were 19 years old, and 26 were 20 years old. Arrests then sharply fall off.

3. 108 out of the 110 people arrested for statutory rape were male.

Is this number high or low? Well, Virginia has roughly 150,000 males aged 15-20. If you think that just 1% of them committed statutory rape under Virginia law, that's only a 4% probability of even being arrested. I couldn't find any statistics on prosecutions or convictions, but I'd be surprised if more than a quarter of arrests led to conviction. And if you think the prevalence of statutory rape is higher - say a violation rate of 5% for males aged 15-20 - that means a conviction risk of 0.2%.

Should Virginia have a Romeo and Juliet law? Sure. Are young men unjustly arrested and jailed? A few. But is the nightmare scenario a good reason to keep parents of young men awake at night? Not really. As the literature on availability bias teaches us, the human mind seriously overestimates the frequency of vivid events. While parents of teens face many challenges, they should never forget their most powerful ally in the fight against paranoia: numeracy.

(9 COMMENTS)

July 11, 2017

Stop Thinking Like a Tourist, by Bryan Caplan

Twenty years later, you return. The lovely rural town is now a regional fracking center. Population: 100,000. The charm has vanished beneath a tidal wave of new construction - residential, commercial, and industrial. You take one picture with your smart phone where you shed a tear of sorrow with New Frack City in the background. Your caption: "Progress?"

From a tourist's point of view, you're clearly right. Lovely rural towns are much nicer to visit than regional fracking centers. Almost anyone who saw Before-and-After pictures would agree with you: the town's gotten far worse.

But what's so great about the tourist's point of view anyway? Tourism is just one tiny industry in a vast economy. If a billion-dollar fracking industry replaces a ten-million-dollar sight-seeing industry, that's a $990M gain for mankind, not a "tragedy." The transformation is clearly good for the 97,000 new residents of the town. It's good for everyone who consumes the new petroleum products. And while the original inhabitants will probably gripe about all they've lost, they're free to sell at inflated prices and move to one of the many remaining lovely rural towns.

Why then is the tourist's perspective so compelling? Let me count the ways.

First: As Bastiat would say, touristic charm is "seen," while industrial output is "unseen." You pass through a lovely location; you immediately sigh, "Aah." You pass by a fracking field; you immediately grimace, "Yuck." To appreciate the wonder of fracking, you have to set aside your gut reaction and visualize the massive and manifold global benefits of cheaper energy.

Second: Tourists hastily impute their initial disgust to locals: "If looking at fracking once makes me feel bad, it must be hell to actually live here." But this impulsive reaction ignores everything we know about hedonic adaptation. Once I got a flat tire outside of Sigmaringen, Germany. When I complimented the guy at the repair shop on his idyllic town, he furrowed his brow and reflected, "Oh, I guess. We don't really think about it." The broader lesson: If you live with beauty every day, you largely take it for granted - and the same goes for ugliness. That's why most people happily live in places most people wouldn't like to visit.

Third: Tourism has high status in our society. Elites travel widely, and look down on provincial folk who don't. As a result, many of us tacitly treat touristic beauty as a merit good - and many more pretend to concur in order to bolster our own status. Could elites be right? My default is to say, "Yes," but as merit goods go, tourism seems like a pretty arbitrary selection.

This summer, I'm spending a month in France. It's a lovely country; I'd happily spend a year there, just nosing around. But that doesn't mean that France is an especially wonderful country overall. If France had ten times the population with half of France's current per-capita income and none of its famous attractions, I probably wouldn't want to visit it. But all things considered, why wouldn't that be a huge improvement?

(8 COMMENTS)

July 5, 2017

Minimally Convincing, by Bryan Caplan

This paper evaluates the wage, employment, and hours effects of the first and second phase-in of the Seattle Minimum Wage Ordinance, which raised the minimum wage from $9.47 to $11 per hour in 2015 and to $13 per hour in 2016. Using a variety of methods to analyze employment in all sectors paying below a specified real hourly rate, we conclude that the second wage increase to $13 reduced hours worked in low-wage jobs by around 9 percent, while hourly wages in such jobs increased by around 3 percent. Consequently, total payroll fell for such jobs, implying that the minimum wage ordinance lowered low-wage employees' earnings by an average of $125 per month in 2016.The second looks at Denmark. Punchline:

On average, the hourly wage rate jumps up by 40 percent when individuals turn eighteen years old. Employment (extensive margin) falls by 33 percent and total labor input (extensive and intensive margin) decreases by around 45 percent, leaving the aggregate wage payment nearly unchanged. Data on flows into and out of employment show that the drop in employment is driven almost entirely by job loss when individuals turn 18 years old.These look like careful studies to me. But if I were a pro-minimum wage activist, neither would deter me. As I confessed before the empirics were in:

If I were sympathetic to the minimum wage, I'd insist, "The worst theIn other words, I'd channel Ayn Rand villain Ivy Starnes:

experiments will show is that high minimum wages hurt employment in individual cities.

That wouldn't be too surprising, because it's easy for firms and

workers to move in and out of cities. The experiments will shed little

light on state-level minimum wages, and essentially no light on federal

minimum wages."

She made a short, nasty, snippy little speech in which she said that theThe same goes, of course, for a group-specific minimum wage. If I favored the minimum wage, I'd look at the Danish results and say:

plan had failed because the rest of the country had not accepted it,

that a single community could not succeed in the midst of a selfish,

greedy world - and that the plan was a noble ideal, but human nature was

not good enough for it.

"Fine, high minimum wages hurt employment for workers in the critical age category.What if the studies had come out the other way? Opponents also have a plausible objection: The studies measure short-run disemployment effects, which we should expect to be mild. In the long-run, however, employers have far more flexibility. They can replace labor with capital. They can replace low-skilled workers with higher-skilled workers. And they can shed workers the guilt-free way - by attrition.

So what? It only shows that when some workers are poorly protected, firms prefer to hire them. The experiments shed little

light on comprehensive minimum wages that protect everyone. Plus, Denmark is a small country of 6M people. If Denmark's minimum wage hurts low-skill Danes, we need a pan-European minimum wage, not deregulation."

I'm not an Austrian economist; our profession's shift from pure theory to empirics has been a huge step forward. But we also need common sense and a broad view of what empirical evidence counts as "relevant." As I've said before:

In the absence of any specific empirical evidence, I am 99%+And:

sure that a randomly selected demand curve will have a negative slope. I

hew to this prior even in cases - like demand for illegal drugs or

illegal immigration - where a downward-sloping demand curve is

ideologically inconvenient for me. What makes me so sure? Every

purchase I've ever made or considered - and every conversation I've had

with other people about every purchase they've ever made or considered.

Research doesn't have to officially be about the minimum wage to be

highly relevant to the debate. All of the following empirical

literatures support the orthodox view that the minimum wage has

pronounced disemployment effects:1. The literature on the effect of low-skilled immigration on native wages. A strong consensus finds that large increases in low-skilled immigration have little effect on low-skilled native wages. David Card himself is a major contributor here, most famously for his study of the Mariel boatlift. These results imply a highly elastic demand curve for low-skilled labor, which in turn implies a large disemployment effect of the minimum wage.

This consensus among immigration researchers is so strong that George Borjas titled his dissenting paper "The Labor Demand Curve Is Downward Sloping."

If this were a paper on the minimum wage, readers would assume Borjas

was arguing that the labor demand curve is downward-sloping rather than vertical. Since he's writing about immigration, however, he's actually claiming the labor demand curve is downward-sloping rather than horizontal!

2. The literature on the effect of European labor market regulation. Most economists who study European labor markets admit that strict labor market regulations are an important cause of high long-term unemployment.

When I ask random European economists, they tell me, "The economics is

clear; the problem is politics," meaning that European governments are

afraid to embrace the deregulation they know they need to restore full

employment. To be fair, high minimum wages are only one facet of

European labor market regulation. But if you find that one kind of

regulation that raises labor costs reduces employment, the reasonable

inference to draw is that any regulation that raises labor costs has similar effects - including, of course, the minimum wage.

3. The literature on the effects of price controls in general.

There are vast empirical literatures studying the effects of price

controls of housing (rent control), agriculture (price supports), energy

(oil and gas price controls), banking (Regulation Q) etc. Each of

these literatures bolsters the textbook story about the effect of price

controls - and therefore ipso facto bolsters the textbook story about

the effect of price controls in the labor market.

If you object, "Evidence on rent control is only relevant for housing

markets, not labor markets," I'll retort, "In that case, evidence on

the minimum wage in New Jersey and Pennsylvania in the 1990s is only

relevant for those two states during that decade." My point: If you

can't generalize empirical results from one market to another, you can't

generalize empirical results from one state to another, or one era to

another. And if that's what you think, empirical work is a waste of

time.

4. The literature on Keynesian macroeconomics. If you're even mildly Keynesian,

you know that downward nominal wage rigidity occasionally leads to lots

of involuntary unemployment. If, like most Keynesians, you think that

your view is backed by overwhelming empirical evidence, I have a challenge for you: Explain why market-driven downward nominal wage rigidity leads to unemployment without implying

that a government-imposed minimum wage leads to unemployment. The

challenge is tough because the whole point of the minimum wage is

to intensify what Keynesians correctly see as the fundamental cause of unemployment: The failure of nominal wages to fall until the market clears.

And don't forget the vast literature on labor demand elasticity...

July 4, 2017

They Were Terrible, by Bryan Caplan

1. To keep your identity and share the blame: "We were terrible."

2. To renounce your identity and avoid the blame: "They were terrible."

3. To redefine the perpetrators' identity and avoid the blame: "We weren't involved."

4. To keep your identity and deny the facts: "Never happened - and they had it coming."

If you value your identity, the first two options are bitter. The third option's only slightly more palatable, because it makes group membership contingent on good behavior rather than a birthright. No wonder, then, that humans around the world gravitate toward the fourth option.

Intellectually, of course, denial's unconvincing. When outgroups evade ugly truths, we readily detect their dishonesty. But when you deny, fellow group members will back you up. If you're sufficiently clannish - or if your group is very common - you'll rarely be called to account for your childishness.

What alternative is there? As I've argued before, you simply shouldn't identify with large, unselective groups. Truth matters more than any tribe. And if you've followed this advice, you can interpret history honestly, without bruising your ego. Americans, Catholics, Irish, or Democrats committed grave wrongs? Then they were terrible. It's got nothing to do with me.

(5 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers