Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 84

April 4, 2017

What's Wrong With the Rationality Community, by Bryan Caplan

Ezra KleinThe rationality community.

Tyler CowenWell, tell me a little more what you mean. You mean Eliezer Yudkowsky?

Ezra KleinYeah, I mean Less Wrong, Slate Star Codex. Julia Galef,

Robin Hanson. Sometimes Bryan Caplan is grouped in here. The community

of people who are frontloading ideas like signaling, cognitive biases,

etc.

Tyler CowenWell, I enjoy all those sources, and I read them. That's

obviously a kind of endorsement. But I would approve of them much more

if they called themselves the irrationality community. Because it is

just another kind of religion. A different set of ethoses. And there's

nothing wrong with that, but the notion that this is, like, the true,

objective vantage point I find highly objectionable. And that pops up in

some of those people more than others. But I think it needs to be

realized it's an extremely culturally specific way of viewing the world,

and that's one of the main things travel can teach you.

Here's how I would have responded:

The rationality community is one of the brightest lights in the modern intellectual firmament. Its fundamentals - applied Bayesianism and hyper-awareness of psychological bias - provide the one true, objective vantage point. It's not "just another kind of religion"; it's a self-conscious effort to root out the epistemic corruption that religion exemplifies (though hardly monopolizes). On average, these methods pay off: The rationality community's views are more likely to be true than any other community I know of.

Unfortunately, the community has two big blind spots.

The first is consequentialist (or more specifically utilitarian) ethics. This view is vulnerable to many well-known, devastating counter-examples. But most people in the rationality community hastily and dogmatically reject them. Why? I say it's aesthetic: One-sentence, algorithmic theories have great appeal to logical minds, even when they fit reality very poorly.

The second blind spot is credulous openness to what I call "sci-fi" scenarios. Claims about brain emulations, singularities, living in a simulation, hostile AI, and so on are all classic "extraordinary claims requiring extraordinary evidence." Yes, weird, unprecedented things occasionally happen. But we should assign microscopic prior probabilities to the idea that any of these specific weird, unprecedented things will happen. Strangely, though, many people in the rationality community treat them as serious possibilities, or even likely outcomes. Why? Again, I say it's aesthetic. Carefully constructed sci-fi scenarios have great appeal to logical minds, even when there's no sign they're more than science-flavored fantasy.

P.S. Ezra's list omits the rationality community's greatest and most epistemically scrupulous mind: Philip Tetlock. If you want to see all the strengths of the rationality community with none of its weaknesses, read Superforecasting and be enlightened.

P.S. By "extraordinary" I just mean "far beyond ordinary experience." People who take sci-fi scenarios seriously may find this category hopelessly vague, but it's clear enough to me.

(15 COMMENTS)April 3, 2017

Education, Politics, and Peers, by Bryan Caplan

Abundant research confirms education raises support for civil

liberties and tolerance, and reduces racism and sexism. These effects are only partly

artifactual. Correcting for intelligence

cuts education's impact by about a third. Correcting for intelligence, income,

occupation, and family background slices education's impact in half. All corrections made, education fosters a

package of socially liberal views.

At the same time, abundant research also confirms education raises support for capitalism, free

markets, and globalization. These effects, too, are partly

artifactual. Correcting for intelligence

cuts education's impact by about 40%.

Correcting for intelligence, income, demographics, party, and ideology

halves it. But when all corrections are done, education

fosters a package of economically conservative views.

If educators are as left-wing as they seem, why would education

have such contradictory effects on students' stances? The charitable story is that educators keep

their politics out of the classroom. The

more plausible story, though, is that educators are unpersuasive. The Jesuits say, "Give me the child until he

is seven and I'll give you the man." Society gives liberal educators the child

until he's fifteen, eighteen, twenty two, or thirty. But issue-by-issue, teachers are about as

likely to repel their students as attract them.

Educators could protest, "The problem isn't that we're unpersuasive, but

that students are stubborn," but students revise their opinions all the time. The longer they stay in school, the more they

revise. They just don't revise in a

reliably liberal direction.

Critics who highlight educators' leftist leanings usually have an

ideological ax to grind (or swing): "Leaving education of the young in the

hands of 'politically correct' ideologues endangers our democracy. School should be a vibrant marketplace of

ideas, not a center for indoctrination."

Though they're right about the imbalance, it's a paper tiger. Even extreme left-wing dominance leaves

little lasting impression. Contrary to

the indoctrination story, education doesn't progressively dye students ever

brighter shades of red.

Since education raises social liberalism and economic conservativism, neither liberals nor conservatives

should cheer or jeer education's

effect on our political culture. What

about people who are both socially liberal and economically conservative? Should they admit that education really is

"good for the soul" after all? It's

complicated. If teachers aren't molding

their students, the logical inference is that students are molding each

other. But peer effects, to repeat, are

double-edged. When schools cluster

socially liberal, economically conservative youths inside the Ivory Tower, they

inadvertently but automatically cluster socially conservative, economically liberal

youths outside the Ivory Tower. If education is good for the souls of the

former, it's bad for the souls of the latter.

Net effect on the polity? Ambiguous.

See e.g. Coenders et al. 2003, Weakliem

2002, Nie et al. 1996, Golebiowska 1995, and Case and Greeley 1990.

Nie et al. 1996, and Bobo and Licari 1989.

Kingston

et al 2003.

Caplan 2007, 2001; Weakliem 2002.

Althaus 2003, pp.97-144 similarly finds better-informed people are more

economically conservative, all else equal.

Caplan and Miller 2010, pp.636-47, plus supplementary calculations from the authors.

Measuring effects issue-by-issue neatly explains education's puzzlingly small

impact on ideology and party. Since

education simultaneously increases social liberalism and economic conservatism, its effect on "liberalism" is

ambiguous. And while their social

liberalism makes the well-educated more Democratic, their economic conservatism

makes them more Republican, leaving partisanship nearly untouched.

AzQuotes 2016.

Lott 1990 argues dictatorships spend more on education in order to indoctrinate

their citizens; Pritchett 2002 argues that this indoctrination motive explains

why all governments produce

schooling. Plausible claims, but they

hardly show the indoctrination is very persuasive.

(3 COMMENTS)

March 30, 2017

The Case Against Education News, by Bryan Caplan

2. Pre-orders? You'll know when I know.

3. This fall, I'll be teaching a GMU seminar on the book, with enrollment open to both undergraduates and graduate students. By the end, you should understand not only my contrarian views, but mainstream economics of education.

4. As usual, anyone on Earth who would like to unofficially attend my class is welcome to do so.

5. If someone volunteers to do all the legwork, I'm happy to stream the class.

6. Thanks to everyone who's patiently cheered this project along!

(5 COMMENTS)

March 29, 2017

Complacent Trust, by Bryan Caplan

In economics, the word on the street is that trust is good for growth. And from what I've seen, the leading papers confirm this result. What's striking, though, is that lower-profile papers occasionally reach rather different conclusions. This wouldn't be noteworthy if the lower-profile papers were clearly lower-quality papers. But since the econometrics are simple, the main difference seems to be that the lower-profile papers were published later using more extensive data. In academia, the early bird gets the worm, even if the later bird is closer to the truth.

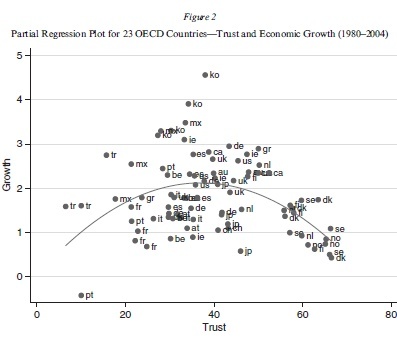

In coming months, I'll be blogging some contrarian papers on trust. Today, let's start with Felix Roth's "Does Too Much Trust Hamper Economic Growth?" (Kyklos, 2009). Big result: Estimating growth as a function of trust and trust squared yields a strong quadratic relationship:

Regression 4, taking a country sample without transition countries, modulates trust as a curvilinear relationship to economic growth by including the squared term of interpersonal trust into the regression. Astonishingly, the curvilinear relationship is highly significant. All variables in the regression have the expected signs and are highly significant (99% level of significance). The linear and squared term of interpersonal trust are each statistically significant: 0.16 (4.42) and -0.0015 (-3.24). These estimates imply that starting from a low-trust country (where the interpersonal trust value is for instance 2.8, as in Brazil), increases in interpersonal trust tend to stimulate economic growth. However, the positive influence attenuates as the level of trust rises and reaches zero when the indicator takes on a mid-range of 53.3. Therefore, an increase in the level of trust appears to enhance economic growth in countries that have initial low levels of trust but to retard economic growth for countries that have already achieved a substantial level of trust.Within the OECD sub-sample, "The positive influence attenuates as the level of trust rises and reaches zero when the indicator takes on a mid-range of 42.5." Here's the cool graph:

With fixed effects, moreover, the linear effect of trust on growth looks negative:

With fixed effects, moreover, the linear effect of trust on growth looks negative:[T]aking panel data and using a fixed-effects estimation for a 41-country sample over the time period from 1980 to 2004 and with a total of 129 observations, the paper points out that economic growth is negatively related to an increase in trust. This negative finding is in contrast to most empirical findings using a cross-sectional design. The negative relationship seems to be mainly driven by developed countries from the OECD (here specifically Poland, Greece, and the United States), and the EU-15 (here particularly theBut how on Earth could trust ever be bad? The most obvious story is Cowenian. Excessive trust leads to (or is perhaps identical with) complacency. If everything is awesome, who needs innovation and dynamism?

United Kingdomand Finland), and very strongly by LMEs [liberal market economies] and Scandinavian countries.

Is this paper the final word? Of course not. Maybe the pro-trust consensus is right and Roth is wrong. But given the prevalence of academic groupthink, the opposite wouldn't surprise me. At all.

(10 COMMENTS)

March 28, 2017

UBI and Health Care: What's Wrong With Murray's Approach, by Bryan Caplan

On the surface, it's ingenious. Most UBI advocates exclude health care because health insurance premiums vary tremendously from person to person. But if health insurers have to charge a uniform premium, this problem seems to go away. Averaging over everyone, premiums would be well below Murray's proposed UBI of $10,000 per year. Everyone could therefore afford to comply with the mandate. Maybe you shouldn't even call it a "mandate"; it's just a rule you have to follow to collect your UBI.

Regulation #1. UBI recipients must purchase health insurance.

Regulation #2. "Legally obligate medical insurers to treat the population, of all ages, as a single pool." Health insurance is still private and competitive. But if an insurer wants to cut its price, it must cut it for everyone.

The problem: As long as health insurance remains private and competitive, health insurers compete on quality as well as price.* Since their elderly and sick customers are losing ventures, there's an obvious incentive to selectively cut their quality so they take their business elsewhere. In Murray's world, no insurer wants to be known as a geriatric specialist. Instead, prudence urges them to lavish services on the young and healthy. Physical fitness programs. Free contraception, delivered by drone for no extra charge. That kind of thing.

How severe would the problem be? Very. The cost of insuring a 91-year-old is far higher than the cost of insuring a 21-year-old. If the law forces firms to charge both the same rate, firms will desperately search for ways to repel the aged and attract the young. Blasting "today's hottest music" over the P.A. system is only the beginning.

Of course, the government could impose a comprehensive system of quality regulation to prevent this kind of thing. But given the immense cross-subsidies, enforcement would have to be both encyclopedic and draconian. The UBI aspires to simplify the welfare state, but ends up piling a whole new strata of regulation on top of the status quo. What's the point?

I'm a huge Charles Murray fan. In Our Hands is my favorite book on the UBI. But his elegant effort to fold health care into the UBI fails.

* This is a key part of Murray's vision: Like me, he advocates supply-side

health-care reforms like ending medical licensing and allowing

contractual limits on medical liability.

(8 COMMENTS)

March 27, 2017

Two Intuitionist Insights, by Bryan Caplan

Virtually all nonintuitionists are hypocritical: they adopt and retain ethical beliefs in precisely the way that intuitionists do - namely, they believe what seems right to them, until they have grounds for doubting it - with the sole difference being that they are less self-aware, that is, they don't say that this is what they are doing. Then they hold forth about how bad it is to do that.Consequentialists are, as usual, the most egregious offenders. They scoff at intuition in favor of "arguments," but what's the non-question-begging argument for their view? After thirty years of philosophy, I'm still waiting.

Huemer also elaborates on the asymmetry between moral and political intuitions:

Even among nonlibertarians, it is not so much that most people have the intuition that the government has authority or that most people believe that government has authority, as that they are habitually disposed to presuppose the government's authority. Most people, I suspect, have never actually thought about whether or why the government has legitimate authority. When explicitly confronted with the fact that the government performs many actions that would be considered wrongful for any other agent, very few people say, "Yeah, so what? It's the government, so it's obviously OK." Rather, most people can easily be brought to feel that there is a philosophical problem here.Or as Huemer explains elsewhere:

When I present the issue to students, for example, it is very easy to motivate the problem, and no one ever suggests that no reason is needed for why government is special. By contrast, for instance, when you point out that although it is wrong to destroy a human being, it is not considered similarly wrong to destroy a clod of dirt, no one gets puzzled.

At first glance, it may seem paradoxical that such radical politicalIf Huemer's approach is so strong, why is it so unpopular? I'm tempted to blame people's unphilosophical attitude, but Huemer's approach is also unpopular within philosophy. A mix of status quo bias and emotional attachment to mainstream political ideologies is the best explanation I can muster.

conclusions could stem from anything designated as "common sense." I do

not, of course, lay claim to common sense political views. I claim that

revisionary political views emerge out of common sense moral views.

P.S. Jason Brennan's chapter on moral pluralism is also excellent.

(8 COMMENTS)

March 23, 2017

Good Manners vs. Political Correctness, by Bryan Caplan

These days, however, I'm also often appalled by the opponents of political correctness. I'm appalled by their innumeracy. In a vast world, daily "newsworthy" outrages show next to nothing about the severity of a problem. I'm appalled by their self-pity. Political correctness is annoying, but the world is packed with far more serious ills. Most of all, though, I'm appalled by their antinomianism, better known as "trolling." Loudly saying disgusting things you probably don't even believe in order to enrage "Social Justice Warriors" further impedes the search for truth - and makes your targets look decent by comparison.

Against both political correctness and the trolling it inspires, I propose an old-fashioned remedy: good manners. Everyone should feel comfortable speaking their minds - as long as they're polite. In slogan form: It's not what you say; it's how you say it.

Every child knows the basics of politeness. Talk nicely. Don't yell. Don't call names. Listen and respond to what people literally say. Don't personally insult people. Don't take generalizations personally. If someone's meaning is unclear, don't put words his mouth; ask him to clarify. And of course, don't escalate. If someone's impolite, the polite response is to end the conversation, not respond in kind.

Isn't this just "tone policing"? Sure. People can and should comport themselves like ladies and gentlemen. You can fairly criticize Social Justice Warriors for one-sided tone policing - their failure to police their own tone. And you can fairly criticize them for acting as if there's no polite way to reject their views. But proper tone policing is what makes conversation productive and pleasant. (And of course, the more pleasant conversation is, the more we're likely to constructively converse).

Aren't some positions inherently impolite? Maybe, but they're so rare we needn't worry about them. If someone says, "Your whole family should be murdered," they almost always say so impolitely. To put it mildly. But there are clear exceptions. It's not impolite to simply be a utilitarian, and in the right kind of trolley problem, utilitarianism implies murderous answers. While I'm not a Peter Singer fan, he seems polite to me.

But isn't trolling fun? For some people, it obviously is. But trolling is still very bad. If someone trolls you, you should just politely end the conversation and find someone worth talking to.

(12 COMMENTS)

March 22, 2017

Is Immigration a Basic Human Right? Full Video, by Bryan Caplan

(1 COMMENTS)

March 21, 2017

Pacifism in Hell's Angels, by Bryan Caplan

Until recently, I only knew Howard Hughes' World War I saga

Hell's Angels

(1930) second-hand, from Martin Scorsese's Hughes biopic, The Aviator. I was amazed when I finally watched Hughes' classic. The special effects are stunning even by modern standards. And the Pre-Code script is too good to be true.

Until recently, I only knew Howard Hughes' World War I saga

Hell's Angels

(1930) second-hand, from Martin Scorsese's Hughes biopic, The Aviator. I was amazed when I finally watched Hughes' classic. The special effects are stunning even by modern standards. And the Pre-Code script is too good to be true. On the surface, the audience is supposed to detest the selfish, unscrupulous Monte Rutledge, the "bad brother" of protagonist Roy Rutledge. But as in Milton's Paradise Lost, the author plainly has great sympathy for the devil. The best scene must have shocked World War I veterans around the world. When Monte feigns illness to avoid combat, a fellow pilot angrily declares, "He's yellow and we all know it." Then Monte pulls off the mask:

That's a lie!Critics routinely dismiss pacifists as "cowards." But as I've said before:

I'm not yellow.

I can see things as they are, that's all.

I'm sick of this rotten business.

You fools. Why do you

let them kill you like this?

What are you fighting for?

Patriotism. Duty. Are you mad?

Can't you see they're just words?

Words coined by politicians and profiteers

to trick you into fighting for them.

What's a word compared with life...

the only life you've got.

I'll give 'em a word. Murder!

That's what this dirty rotten

politician's war is.

Murder! You know it as well as I do.

Yellow, am I? You're the ones that are yellow.

I've got guts to say what I think.

You're afraid to say it.

So afraid to be called yellow,

you'd rather be killed first.

Given the unpopularity of pacifism - and the extreme unlikelihood that(0 COMMENTS)

your pacifism tips the scales against war - this is plainly false. A

real coward would enthusiastically parrot whatever the people around him

want to hear.

March 20, 2017

Is Immigration a Basic Human Right? My Opening Statement, by Bryan Caplan

There are many complaints

about governments, but the harshest is, "This government grossly violates human

rights." The background assumption is

that human beings have rights that everyone - including governments - is morally obliged to respect. When looking

at the grossest violators - Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, Maoist China -

almost no one denies the validity of the idea of human rights. But then you have to wonder: Do the

governments we know, accept, and even love have clean hands? Or do they violate human rights, too?

To answer, we normally apply

a simple test: If an individual

treated other people the same way the government does, would he clearly be a

horrible criminal? If an individual

deliberately kills innocent people, he's murderer; if an individual imprisons

innocent people, he's a kidnapper. A

government that does the same violates basic human rights - and it can't

justify its actions by calling innocent people "criminals." If someone is peacefully living his life,

he's innocent - whatever the government says.

What does this have to do

with immigration? Lots. Since we're in San Diego, you've seen illegal

immigrants. What are the vast majority

of them doing? Working for willing

employers. Renting apartments from

willing landlords. Buying stuff from

willing merchants. Sending money home to

their families. Maybe even sitting next to you in class. They sure look innocent - even admirable. But the U.S. government can and does forcibly

arrest and exile them to the Third World.

Why can't they all just come legally?

Because exile is the default; they're all exiled unless the U.S. government makes a rare exception. This is far less bad than killing or

imprisoning them, but it sure looks like a severe human rights violation. If the U.S. government forbade you to live

and work here, wouldn't that be a severe violation of your human rights?

You could reasonably object

that human rights are not absolute.

While there's a strong moral presumption

against killing, imprisoning, or exiling innocent people, it's okay to do so if

the overall consequences of respecting human rights are clearly awful. The main problem with this objection is that

when social scientists measure the overall consequences of immigration, they're

not clearly awful. In fact, the overall consequences look

totally awesome. Most notably, standard

economic estimates say that letting all the world's talent flow to wherever

it's most productive would roughly DOUBLE global prosperity. That's an extra $75 TRILLION of extra wealth per

year. How is this possible? Because even the world's lowest-skill workers

produce far more in the First World than they do at home. Even if all other fears about immigration

were bulletproof - which they aren't - they're dwarfed by this gargantuan

economic gain. This isn't trickle-down

economics; it's Niagara Falls economics.

To effectively defend

immigration restrictions, then, saying "Human rights are not absolute" is

insufficient. You need to flatly deny

that immigration is a human right - to say that while the illegal immigrants

you meet on the street may look innocent, they're actually guilty as hell. The most popular argument analogizes illegal

immigrants to trespassers. No one has

any right to be here without government permission; it's our country, so we set

the rules.

The obvious problem with this

position is that it justifies a vast range of blatant human rights abuses. If it's our country and we set the rules, why

can't we exile citizens, too? Why can't

we imprison people for saying the wrong thing, practicing the wrong religion,

or having kids without government permission?

Saying, "That won't happen," dodges the question: If the U.S. government

did this to you, would it be violating your human rights or not?

Prof. Wellman offers a more

sophisticated version of this story. He

defends immigration restrictions for "legitimate states" only, on the grounds

that immigration restrictions are vital for "freedom of association." Unfortunately, we have two conflicting

freedoms of association. I want to be

free to associate with foreigners; lots of foreigners want to associate with

me. Immigration restrictions deny us

this freedom in the name of all the Americans who don't want my associates breathing

American air.

Who should prevail? In his work, Wellman concedes a crucial

premise, freely admitting that the popular notion that we all consent to

government is a "fiction," and that "the coercion states invariably employ is

nonconsensual and, as such, is extremely difficult to justify." We don't really face a choice between two

freedoms of association, but between freedom for real associations we choose to

join and freedom for fictional "associations" we're forced to join. Unless the overall consequences are clearly awful,

the fictional ones should lose. Freedom

of association is only for free associations.

My critics often tease me,

"Should everyone on Earth be free to immigrate into Bryan's house?" Their point: Treating immigration as a human

right is utopian nonsense. My reply:

There are three competing moral

positions on immigration.

Foreigners should be free to live in my house

even if I don't consent - a view held by almost no one.Foreigners should be free to live in my house if

I consent - my view.Foreigners shouldn't

be free to live in my house even if I do consent - the standard view I'm criticizing.

Far from being utopian,

saying "Immigration is a human right" is just the moderate, common-sense

position that when natives and foreigners voluntarily interact, strangers are morally

obliged to leave them alone unless the overall consequences are clearly awful. Even if the

stranger happens to be the government - and the government happens to be popular.

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers