Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 85

March 6, 2017

Soonish by Kelly and Zach Weinersmith, by Bryan Caplan

My co-author, Zach Weinersmith, and his wife, Kelly Weinersmith, have a new book out on future technology and its economic and social implications. News flash: Soonish is currently at #3 on Amazon. As Neo said, "Woh."

My co-author, Zach Weinersmith, and his wife, Kelly Weinersmith, have a new book out on future technology and its economic and social implications. News flash: Soonish is currently at #3 on Amazon. As Neo said, "Woh."(0 COMMENTS)

San Diego Immigration Debate, by Bryan Caplan

P.S. I may be able to run an RPG in San Diego while I'm in town. If you're interested, email me.

(5 COMMENTS)

March 2, 2017

Power-Hunger, by Bryan Caplan

your accomplice in the wood chipper. And those three people in Brainerd.

And for what? For a little bit of money. There's more to life than a

little money, you know. Don't you know that?"

What economics teaches is not that greed is good, but that good incentives transform this questionable motive into awesome results. Greed plus property rights plus competition plus rationality plus reputation is good. Greed alone is film noir.

In Public Choice, also known as "economics of politics," we usually assume that politicians are motivated not by greed, but by power-hunger. Of course, we rarely utter the word "power-hunger." Instead, we call it "vote maximization," just as we call greed "profit maximization." But when Public Choice pictures politicians, it pictures humans filled with lust for power.

Is this a reasonable picture of politicians' psyches? Absolutely. That politicians crave power is as undeniable as that businesspeople crave profits. If you look at political history before the rise of democracy, we see virtually nothing other than dictators struggling to cement their power internally and expand their power externally. When these dictators lost wars, they lost territory and subjects, because virtually every dictators wanted to rule over as much land and as many people as possible.

Under democracy, politicians are less candid about their motives; they need us to like them, and power-hunger is not likeable. But given its ubiquity throughout most of political history, can we really believe that the motive of power-hunger is no longer paramount? One of my favorite political insiders privately calls politicians of both parties "psychopaths" - and he's on to something. Rising high on the pyramid of power is hard unless love of power fuels your ascent.

In a randomly-selected social environment, power-hunger - like greed - is brutal. Just look at the history of warfare in all its hideousness - the endless bloodbaths over slivers of territory. Remember how leaders terrorized their rivals, their potential rivals, their imagined rivals. It's sickening. If Fargo were a war story, and Marge Gunderson hunted war criminals, she might have sadly mused, "So that was Sarajevo on the floor in there. And I guess those were

your accomplices in the mass grave. And those three hundred thousand people in Bosnia.

And for what? For a little bit of power. There's more to life than a

little power, you know. Don't you know that?"

In dictatorships, the causal chain from power-hunger to bad results is obvious. The fundamental question of Public Choice is: Does democracy motivate power-hungry politicians to do good despite their bad intentions? My admirable nemesis, Donald Wittman, tirelessly argues Yes, but to no avail. Democracy out-performs dictatorship, but that's damning with faint praise.

Once you thank the stars you aren't ruled by Louis XIV or Lenin, a grim truth remains: democracy gives power-hungry politicians far worse incentives than the market gives greedy businesspeople. Above all, voters - unlike consumers - have no incentive to be rational, spurring power-hungry politicians to preach and practice endless demagoguery. It's gotten worse lately, but it's always been terrible. Democracy hasn't turned politicians into decent human beings; it's only gilded their age-old power lust with altruistic hypocrisy.

So what can we do about our predicament? There are no easy answers, but I know where to start. Like alcoholics, we must admit we have a problem. Throughout history and around the world, the wicked rule. We should stop admiring them - especially the politicians on "our side" - and see them for the reprobates they are.

(8 COMMENTS)

March 1, 2017

Read Meer, by Bryan Caplan

Today's speaker at the Public Choice Seminar is Jonathan Meer of Texas A&M, one of my favorite young empirical economists in the world. He's doing the most innovative work on the minimum wage, wisely building on the ubiquity of firing aversion. He's also doing creative and multi-pronged work on education, charity, labor, and health economics. All his research is conveniently accessible right here. Enjoy!

Today's speaker at the Public Choice Seminar is Jonathan Meer of Texas A&M, one of my favorite young empirical economists in the world. He's doing the most innovative work on the minimum wage, wisely building on the ubiquity of firing aversion. He's also doing creative and multi-pronged work on education, charity, labor, and health economics. All his research is conveniently accessible right here. Enjoy!(1 COMMENTS)

February 28, 2017

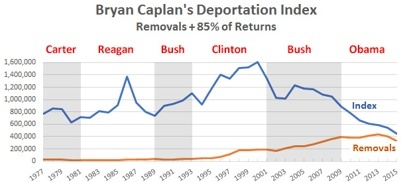

My Deportation Index: The Drum Critique, by Bryan Caplan

His critique begins with some some data I didn't know about.

The next step is to calculate this as a percentage of the number of illegal immigrants in the country each year. Here it is:

His punchline:

His punchline:This is approximate, since the total population of illegal immigrants isIt's a thought-provoking point. For the typical immigrant, justified fear of deportation peaked under Reagan, then almost continuously declined. But when we're playing Lord Acton ("Suffer no man and no cause to escape the undying penalty which history

a little fuzzy before 2000. But it's close enough. Obama still has a

higher removal rate and a lower index rate than any other president, but

the winner for the title of Deporter-in-Chief is...Ronald Reagan. Every

president since then has been successively more tolerant of a large

undocumented population.

has the power to inflict on wrong"), does it make sense to adjust for the population of potential victims? Or should we just count the victims? I honestly don't know.

(7 COMMENTS)

February 27, 2017

Trump Bet Clarification, by Bryan Caplan

If DonaldWhen re-reading the bet, however, I realized that I omitted a key understanding of the bet. After consulting with my partner, we've amended the terms to reflect our original intent. It now reads:

Trump resigns, is removed by the Senate after impeachment, or otherwise

is permanently removed as per the the 25th Amendment, or if it never happens

that he takes the Oath of office as POTUS on Jan 20, 2017, the BC owes [redacted] $350.

Otherwise, [redacted] owes BC $100".

If DonaldNote that this revision is entirely adverse to my interests. In fact, as I said before, I think Trump's death is my most probable losing scenario.

Trump dies in office, resigns, is removed by the Senate after impeachment, or otherwise

is permanently removed as per the the 25th Amendment, or if it never happens

that he takes the Oath of office as POTUS on Jan 20, 2017, the BC owes [redacted] $350.

Otherwise, [redacted] owes BC $100".

(1 COMMENTS)

February 23, 2017

Who's the Real "Deporter in Chief"?, by Bryan Caplan

The distinction is not entirely cosmetic. If you re-enter after Removal, you face a serious risk of federal jail time if you're caught. If you re-enter after a mere Return, you generally don't. But Return is still almost as bad as Removal, since both exile you from the country where you prefer to reside. Since I've previously suggested that we should count each Return as 85% of a Removal, I've constructed a "Deportation Index" equal to Removals + .85*Returns to capture the substance of U.S. immigration policy. Check out the numbers:

Year

Removals

Returns

Deportation Index

1977

31,263

867,015

768,226

1978

29,277

975,515

858,465

1979

26,825

966,137

848,041

1980

18,013

719,211

629,342

1981

17,379

823,875

717,673

1982

15,216

812,572

705,902

1983

19,211

931,600

811,071

1984

18,696

909,833

792,054

1985

23,105

1,041,296

908,207

1986

24,592

1,586,320

1,372,964

1987

24,336

1,091,203

951,859

1988

25,829

911,790

800,851

1989

34,427

830,890

740,684

1990

30,039

1,022,533

899,192

1991

33,189

1,061,105

935,128

1992

43,671

1,105,829

983,626

1993

42,542

1,243,410

1,099,441

1994

45,674

1,029,107

920,415

1995

50,924

1,313,764

1,167,623

1996

69,680

1,573,428

1,407,094

1997

114,432

1,440,684

1,339,013

1998

174,813

1,570,127

1,509,421

1999

183,114

1,574,863

1,521,748

2000

188,467

1,675,876

1,612,962

2001

189,026

1,349,371

1,335,991

2002

165,168

1,012,116

1,025,467

2003

211,098

945,294

1,014,598

2004

240,665

1,166,576

1,232,255

2005

246,431

1,096,920

1,178,813

2006

280,974

1,043,381

1,167,848

2007

319,382

891,390

1,077,064

2008

359,795

811,263

1,049,369

2009

391,341

582,596

886,548

2010

381,738

474,195

784,804

2011

386,020

322,098

659,803

2012

416,324

230,360

612,130

2013

434,015

178,691

585,902

2014

407,075

163,245

545,833

2015

333,341

129,122

443,095

Notice: Despite the rise in Removals under Obama, Returns crashed. Obama's Deportation Index therefore falls as soon as he takes office - and then declines further every single year! By 2015, Obama's D.I. is half its 2009 value, and about one-third of its previous peak under Bush II.

Does this mean Democrats are the genuine friend of the immigrant? Not exactly. Here are the average D.I.s for every president from Carter to Obama. The last column adjusts for population in millions, which, as you can see, makes the pattern even more extreme.

President

Average D.I.

Average D.I./Pop/10^6

Carter

776,019

3,471

Reagan

882,572

3,718

Bush I

889,657

3,534

Clinton

1,322,215

4,861

Bush II

1,135,175

3,861

Obama

645,445

2,068

Yes, while Obama has the lowest D.I. of any president over the last four decades, the real Deporter in Chief was none other than fellow Democrat Bill Clinton. Adjusting for population, no one else even comes close. Indeed, while I'm very confident that Trump's D.I. will exceed Obama's, it's far from clear that Trump will manage to displace Clinton from the top spot. (Betting odds: I'll give 4:1 that Trump's average D.I. when he leaves office will exceed Obama's, but only even money than he'll exceed Clinton's).

The lesson, as usual, is that we should look past surface rhetoric to the bedrock of numbers. While both Democrats and Republicans casually equate Clinton and Obama, their immigration policies were as different as day and night.

(4 COMMENTS)

February 22, 2017

Do Middle-Class College Kids Already Have a UBI?, by Bryan Caplan

My reply: While middle-class parents do commonly provide ample financial support for their children, it's nothing like a UBI. Instead, it's heavily means-tested: We'll keep supporting you as long as you pursue a responsible path. "Either stay in school and get passing grades, or get a job and pay rent" is perhaps the typical deal. Many parents add further micromanagement: To receive support, you need high grades, a realistic major, sobriety, and a suitable boyfriend. Only a minority agree to let their children live as they please at their parents' expense. When they do, the results seem pretty bleak. I know of no systematic data on never-employed single 30-year-olds living in their parents' basements, but the anecdotal evidence is chilling. Even parents who provide "unconditional" support ultimately tend to lose patience and angrily switch to old-school "sink-or-swim." And who could blame them?

Will might decry this as "paternalism," but a subtler analysis is in order. For starters, the heart of paternalism is treating adults like children. But parents' obvious reply is, "We're treating our kids like children because they're acting like children." Until you are self-supporting, demanding full autonomy is just chutzpah. In any case, pure self-interest also urges us to impose conditions on our dependents' behavior. "If you want to sleep on my couch, you'd better get to your job interview on time" need not be motivated by my desire to give you a "happy life full of hard work." Maybe I just want my couch back.

To circle back to my broader theme, if people who love you have good reason to impose conditions on their voluntary assistance, people who've never even met you have overwhelming reason to impose conditions on their involuntary assistance. And involuntary assistance is the heart of the welfare state.

(8 COMMENTS)

February 21, 2017

UBI Debate Video, by Bryan Caplan

(0 COMMENTS)

February 20, 2017

Why Libertarians Should Oppose the Universal Basic Income, by Bryan Caplan

Libertarians

have a standard set of fundamental criticisms of the welfare state.

1. Forced

charity is unjust. Individuals have a

moral right to decide if and when they want to help others.

2. Forced

charity is unnecessary. In a free

market, voluntary donations are enough to provide for the truly poor.

3. Forced

charity gives recipients bad incentives.

If the government takes care of you, you're less likely to take care of

yourself by work and saving.

4. The cost

of forced charity is high and growing rapidly, leading to a future of exhorbitant

taxes or financial crisis.

Taken

together, I think these criticisms justify the radical libertarian view that

the welfare state should be abolished. But this is an extremely unpopular view, so it's

natural for libertarians to consider more moderate reforms like the Universal

Basic Income. And when you're

considering moderate reforms, the right question to ask isn't: "Is it ideal?"

but "Is it better than the status quo?"

My claim:

the Universal Basic Income is indeed worse than the status quo. In fact, all the fundamental criticisms of

the welfare state apply with even greater force.

1. Some

forced charity is more unjust than other forced charity. Forcing people to help others who can't help themselves - like kids from

poor families or the severely disabled - is at least defensible. Forcing people to help everyone is not. And for all

its faults, at least the status quo makes some

effort to target people who can't help themselves. The whole idea of the Universal Basic Income,

in contrast, is of course to give money to everyone whether they need it or

not. Of course, the UBI formula normally

reduces the net payment as income rises; but if a perfectly able-bodied person

chooses never to work, the UBI gravy train never stops.

2. The UBI is

an extremely wasteful form of forced charity.

Helping the small minority of people who can't help themselves doesn't

cost much. Giving an unconditional grant

to every citizen wastes an enormous amount of money. If you were running a private charity, it

would never even occur to you to "help everyone," because it's such a frivolous

use of scarce charitable resources.

Instead, you'd target spending to do the most good. And unlike the UBI, the status quo makes some effort to so target its resources.

3. Overall,

the UBI probably gives even worse

incentives than the status quo. Defenders

of the UBI correctly point out that it might improve incentives for people who

are already on welfare. Under the status quo, earning another $1 of

legal income can easily reduce your welfare by a $1, implying a marginal tax

rate of 100%. But under the status quo,

vast populations are ineligible for most programs. Such as?

You guys! If you're an

able-bodied adult, aged 18-64, who doesn't have custody of any minor children, the

current system doesn't give you much.

Switching to a UBI would expand the familiar perverse effects of the

welfare state to the entire population - including you. And if taxes rise to pay for the UBI, the population-wide

disincentives are even worse.

4. A

politically acceptable UBI would be insanely expensive. Libertarian economist and UBI advocate Ed

Dolan has a detailed, fiscally viable plan to provide a UBI of $4452 per person

per year. But every non-libertarian I've

queried thinks it should be at least $10,000 per person per year. Even with a one-third flat tax, that implies

that a family of four would have to make $120,000 a year before it paid $1 of

taxes. This is pie in the sky.

But doesn't

the UBI give people their freedom? In

some socialist sense, sure. But

libertarianism isn't about the freedom to be coercively supported by strangers. It's about the freedom to be left alone by

strangers.

If abolition

of the welfare state is extremely unlikely and the UBI is worse than the status

quo, does this mean libertarians should accept the welfare state as it is? Not at all.

There's a straightforward moderate path to a freer world: AUSTERITY. Cut benefits.

Restrict eligibility. Remind the

world of the great Forgotten Man: the taxpayer.

We probably can't convince the majority to end the welfare state. But "Welfare should be limited to genuinely

poor people who can't help themselves" has broad appeal - and unlike the UBI, it's

a clear step in the libertarian direction.

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers