Doug Lemov's Blog, page 11

December 8, 2022

Gabby Woolf’s Dr. Jekyll Lesson and the Power of Reading Fluency

My colleagues Erica Woolway, Sadie McCleary, Hannah Solomon and I have been working on the TLAC 3.0 Field Guide to support the new 3.0 Teach Like a Champion this fall. It’ll be out in a few months, but it’s a bit different from previous Field Guides in that it focuses on “keystone” videos–longer clips of 8 or 10 minutes that show the broader arc of a teacher’s methods in his or her classroom.

One such clip is from Gabby Woolf’s Year Ten classroom as London’s King Solomon Academy a few years back. Having recently read Christopher Such’s The Art and Science of Teaching Primary Reading and other books on the importance of fluent reading at all grade levels, we saw this clip anew.

The clip starts with Gabby reading The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde aloud to students. We love that Gabby is developing students’ ability and persistence with challenging text and reading with them is a critical part of how she makes it work.

“In the spirit of being sensationalist,” Gabby says, “we want to read it as we would imagine Stevenson would want his readers to imagine it.” Right from the outset she is helping them to think about the connection between reading and meaning. How one expresses a book is part of understanding it. An author might have had a particular voice in mind.

She uses several statements that signal to students that she is looking for expressive reading: “We’re going to focus on the gory details of this murder… I’d like few of you to volunteer with your highly expressive reading.”

Notice that as she reads she is 1) emphasizing expression–she’s modeling how the text should sound so they can copy and adapt 2) more interested in precision than speed. As Christopher Such advises, she reads slightly slower than she might on her own. She wants students to hear the words and how they are expressed clearly. “Startled,” “singular,” “ferocity”… all of these words stand out clearly in their expression and enunciation. They are imbued with meaning via her expression. She is tacitly socializing precision as one reads.

At 1:24 having modeled reading Stevenson’s prose herself, she begins to ask students to read, using the technique FASE reading from TLAC 3.0. Imran “takes over” and though the volume is low, if you listen carefully you can hear him reading with expression and prosody, just like Gabby, in fact, attending carefully to words and syntax and taking a bit of pleasure in bringing the book to life.He has internalized her model.

Joan is next and her reading is similarly expressive and imbued with something like if not pleasure at least appreciation.

These are both “cold calls”… that is the message is that students will be chosen to read at random. So everyone should be ready. and everyone should be reading actively on their own. The “leverage” (rate of students reading along when its not their turn is likely to be high). And the message among peers is clear. We like reading. We take pleasure in it.

The culture is set: The class knows how Stevenson’s text should sound. They’ve heard several models. They know their peers think expressive reading is valuable. And so Gabby sends them, at 3:22, into pairs, to give everyone a bit more practice at fluent reading of challenging text. While the leverage–portion of students actively reading at their desks–is probably high while she’s FASE reading, this move allows her to provide even more fluent reading practice to even more students.

But please recognize that the FASE reading is critical to the partner reading. There’s more synergy than choice. ase reading sets the norms and culture and habits they will rely on in reading in pairs.

She caps this exercise off with praise for individual students whose reading was especially effective and then a quick set of questions for students to answer to make sure they understood what they read. Tips for making independent reading more accountable can be found in TLAC 3.0 (Technique 23: Accountable Independent Reading)

Some notes on the importance of developing fluency:

Fluency consists of accuracy, automaticity & prosody. Developing these requires both hearing and practicing reading aloud.

Older students should continue to get lots of fluency practice. In 2017 Bigozzi et al found that “Reading fluency predicted all school marks in all literacy-based subjects, with reading rapidity being the most important predictor. School level did not moderate the relationship between reading fluency and school outcomes, confirming the importance of effortless and automatized reading even in higher school levels.”

“This might seem obvious,” Christopher Such writes, “but many schools seem to pay little attention to this quantitative aspect of reading instruction in their classrooms.” He also notes that “While children’s reading is still dysfluent, classroom time dedicated to silent reading is time that could be better spent.”

It’s also worth noting how the culture of shared reading brings the pleasure of reading to life. As you are probably aware, reading as a student past time has all but ceased. The numbers of students who read outside of school is dropping steeply as the book loses its death struggle against the phone. If we want students to still read, connecting them to the social pleasure of it in the classroom–as Gabby has done here–is a critical step.

The post Gabby Woolf’s Dr. Jekyll Lesson and the Power of Reading Fluency appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

December 1, 2022

An Excerpt from Reconnect: Building School Culture for Meaning Purpose and Belonging

As many of you know I’ve got a new book out, co-written with Denarius Frazier, Hilary Lewis, and Darryl Williams. It’s called Reconnect: Building School Culture for Meaning Purpose and Belonging and it’s a book about where we are now as schools and what to do about it.

The t heme, you could argue, is belonging: what it is, why it’s so powerful, how we can harness it to ensure greater academic achievement and to instill in students a sense that school is a place that cares for them-and where they should care about others.

Over the next few weeks I’m going to try to post some excerpts. Like this one, which talks a bit more about the details of how people are connected:

Small Moments and the Gestures of Belonging

Belonging is among the most powerful human emotions, and Daniel Coyle discusses its role in modern group formation in his book The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups. Belonging, he notes, is often built via small moments and seemingly insignificant gestures. In fact, it is mostly built that way. Cohesion and trust occur when group members send and receive small, frequently occurring signals of belonging. The accrual of these signals is almost assuredly more influential than grand statements of togetherness or dramatic gestures. “Our social brains light up when we receive a steady accumulation of almost invisible cues: we are close, we are safe, we share a future,” Coyle writes. But it’s not a one-time thing. Belonging is “a flame that needs to be continually fed by signals of connection.”

A colleague of ours described a simple example of this when we visited her school in the days after the mask mandate was lifted in her area. “I’m trying to make sure I focus on eye contact and smiling,” she said. “That we focus on rebuilding that habit as a staff, so kids

see someone smiling at them when they walk down the hall and they know: this is my place.”

Smiling and making eye contact are two of the most important belonging cues. They are also indicative of the nature of belonging cues more broadly; they tend to be subtle and even fleeting in nature so they are easily overlooked. Saying “thank you” and engaging in ritual forms of civility—holding a door, letting someone else go first, shaking hands—are other examples. Holding the door or letting someone go first as you enter provides little if any practical benefit; like most acts of courtesy, it’s really a signal: “I am looking out for you.” It reaffirms connectedness. And it affects more than just the individual to whom you show courtesy. Coyle notes that in one study, “a small thank you caused people to behave far more generously to a completely different person. This is because thank yous are not only expressions of gratitude. They’re crucial belonging cues that generate a contagious sense of safety, connection and motivation.”

When we respond to a belonging signal not just by signaling back to the person who sent it but by sending additional signals to other people, it is an example of what the political scholar Robert Keohane calls “diffuse reciprocity.” “Specific reciprocity” is the idea that if I help you, you will help me to a roughly equal degree. It is often the first step in commercial or political exchange, but it tends to engender only limited levels of trust and connection. Diffuse (or generalized) reciprocity, however, is the idea that if I help you, someone else in the group will likely help me at some future point. “Diffuse reciprocity refers to situations in which equivalence is less strictly defined and one’s partners in exchanges may be viewed as a group,” Keohane writes.Norms are important. When participating in or initiating diffuse reciprocity, I go out of my way to show I am not keeping score and don’t require equal value in every transaction. I am trying to show that I think we are part of a group, that what goes around will come around.

This is why in many cultures and settings, nothing is more insulting than insisting on paying for what was freely given. It is responding to an offer of welcome or help—diffuse reciprocity—with a signal of specific reciprocity. It suggests “transaction” rather than “connection”

and downgrades the other person’s gesture.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about signals of gratitude and belonging, however, is that the true beneficiary is the sender. It makes us happy to be generous and welcoming in part because it makes us feel like good members of the community and, perhaps, like more secure members of the community as a result. As the French philosopher la Rochefoucauld observed, “We are better pleased to see those on whom we confer benefits than those from whom we receive them.” Summarizing his research, von Hippel writes, “Life satisfaction is achieved by being embedded in your community and by supporting community members who are in need.” Note the centrality of mutuality; there’s equal emphasis on the psychological benefits of giving to the group as well as receiving from it.

Gratitude too is one of the most powerful human emotions. As Shawn Achor explains in his book The Happiness Advantage, expressing gratitude regularly has the effect of calling your (or your students’) attention to its root causes. Done regularly this results in a “cognitive afterimage”: you are more likely to see the thing you look for. If you expect to be thinking about and sharing examples of things you are grateful for, you start looking for them, scanning the world for examples of good things to appreciate. And so you notice more of them.

The psychologist Martin Seligman asked participants in a study to write down three things they were grateful for each day. They were less likely to experience depression and loneliness one, three, and six months later. “The better they got at scanning the world for good things to write down, the more good things they saw, without even trying, wherever they looked,” Achor writes of the study. The world became a better place for them, one that valued them and stood ready to embrace them because they made a habit of noticing the signals it was sending. “Few things in life are as integral to our well-being [as gratitude],” Achor writes. “Consistently grateful people are more energetic, emotionally intelligent, forgiving, and less likely to be depressed, anxious, or lonely.”

The fact that what we look for so profoundly alters our sense of the world is just one way that the eyes are, perhaps, the most critical tool for establishing belonging. Even their physiological structure shows how critical they are. Humans are the only primate with white sclera—the part of our eyes that surrounds our pupils. This is the case, William von Hippel writes in The Social Leap, because advertising our gaze allows for cooperation and coordination, and because it communicates our status within the group—all of which are far more important to a human than to a primate that is less absolutely reliant on cooperation and mutualism for survival (as all other primates are, even those that live in groups). “If I’m competing with other members of my group, I don’t want them to know what I’m thinking, which means I don’t want them to know where I am looking,” von Hippel says. “Whether I’m eyeing a potential mate or a tasty fig, I’ll keep it a secret so others don’t get there first. But if I’m cooperating with other members of my group then I will want them to know where I am directing my attention. If a tasty prey animal comes along and I spot it first I want others to notice it too so we can work together to capture it.”

Humans also compete within their groups, we’ve noted, and eye gaze, advertised to others via the whites of our eyes, also communicates stature and status within the group. Anyone who has ever given or received a flirtatious glance or participated in a locked-eye challenge can attest to this. “Our scleras . . . allow us to monitor the gazes of others with considerable precision,” Bill Bryson notes in The Body: A Guide for Occupants. “You only have to move your eyeballs slightly to get a companion to look at, let’s say, someone at a neighboring table in a restaurant.” More potently, glances between and among fellow group members tell us whether we are respected and safe or resented, marginalized, or scorned. “Affirming eye contact is one of the most profound signals of belonging a human can send. Conversely, the lack of it could suggest that our inclusion is at risk.”

How valuable is the information carried within our gazes? A “genetic sweep” is the name for a physical change that confers such immense benefit on recipients that over time only people having the change prevail. Having white sclera—in other words, being able to communicate more with a look—is an example. There is no human group in any corner of the planet where the benefits of enhanced gaze information were not evolutionarily decisive.

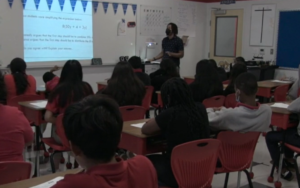

Consider, in light of that, this photograph, which comes from a video of one of Denarius’s lessons when he was a math teacher.

The student Vanessa has just been speaking authoritatively about what she thinks is the explanation of a given solution to a math problem, but suddenly, midway through, she realizes that her explanation is not correct. She has confused reciprocal and inverse. She’s been speaking confidently in front of 25 or 30 classmates—advising them “if you check your notes”—and now, with all eyes on her, she realizes she is dead wrong. She pauses and glances at her notes. “Um, I’d like to change my answer,” she says playfully, without a trace of self-consciousness. She laughs. Her classmates laugh. Laughter too communicates belonging (or exclusion) by the way, and here it clearly communicates: “We are with you.” The moment is almost beautiful—it’s lit by the warm glow of belonging. Students feel safe and supported in one another’s company. The level of trust is profound.

Now look at the girls in the front row. Their affirming gazes—eyes turned to Vanessa encouragingly—communicate support, safety, and belonging. In fact, it’s hard to put it into words just how much their glances are communicating—each one is a little different—but they are as critical to shaping the moment as Vanessa’s own character and persona. They foster and protect a space in which her bravery, humor, and humility can emerge.

Moments that are the converse of this one send equally potent signals, and almost assuredly occur more often in classrooms. The lack of eye contact (or the wrong kind of it) is a signal that something is amiss even if you are told you are a member of a group, and even if someone’s words tell you that you belong. When something feels amiss in the information we receive from the gaze of our peers, we become self-conscious and anxious.

Let’s say you’re at dinner with a handful of colleagues, all sitting around a table. An eye-roll after you speak is a devastating signal. Or if, after you’ve said something, no one looks at you, you start to wonder: Was what I said awkward? Tactless? Clueless? Not-so-funny or even so-not-funny?

Without a confirming glance you are suddenly on edge. Even if you have not been speaking, an ambiguous eye-roll you notice out of the corner of your eye is a source of anxiety. Was that about you? Have you done something to put your belonging at risk? Or suppose you arrive late and saunter over to the table to find that no one looks up; your mind suddenly scrolls through an anxious calculus of what that might mean. Your peers might merely be absorbed in their phones and thus not look up to greet you but your subconscious mind may not distinguish much among potential explanations. No matter the reason for the behavior, it sends a worrying signal of non-belonging. In too many classrooms, students often speak and no one among their peers shows they heard or cared; they struggle and no one shows support. They seek to connect and there is no one signaling a similar willingness. Think here of the loneliest and most disconnected students most of all. How many of them look up to see only disinterest or blank expressions from their classmates? This is the nonverbal environment in which we ask young people to pursue their dreams.

Imagine Vanessa in a room full of averted, disinterested gazes. If she was smart—and if she was like most young people—she’d have known better than to have raised her hand in the first place.

The post An Excerpt from Reconnect: Building School Culture for Meaning Purpose and Belonging appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

November 17, 2022

A Group of Cognitive Scientists and Teachers Go To A Wine Tasting And….

A classroom for some, perhaps

It sounds like the first line of a joke:

“A group of cognitive scientists go to a wine tasting…” but it actually happened.

The punch line “and then they end up having a discussion about the role of knowledge in perception and learning” isn’t ideal from a humor POV but from a teaching POV it was pretty amazing.

The wine tasting took place in Chile at an event for presenters at Research Ed Chile- They included Hector Ruiz-Martin, Juan Fernandez, Harry Fletcher-Wood, Pooja Agarwal, myself and a few other teachers and educators.

The setting was Santa Rita vineyards where after a tour (beautiful!) a wine-maker poured us glasses and encouraged us to describe what we were tasting and smelling.

“What aromas are you getting?” she asked as we sampled a red… it was a red made up of a bunch of different grapes. I can’t remember much more about the wine because I am distinctly not a wine guy.

Ok, now I’ve looked it up… it was a combination of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Carménère… I couldn’t remember that because while I know Cabernet Sauvignon and have heard of Cabernet Franc I’d never heard of Carménère. Which is interesting. If you’d asked some of the others in the group they’d probably remember that right away. It’s easy to remember details of things you know about—you know the word Carménère already- you are just remembering that that it was present. What was the name of that grape I’d never heard of is much harder to remember. Its always harder to remember things you’d never heard of.

In fact when she has asked us to guess what grapes were in the wine several of my colleagues guessed carménère. I couldn’t of course because I lacked background knowledge. How could I infer the presence of something I didn’t know existed?

But back to the story… “Don’t say, ‘grapes,’” our winemaker was saying, as she asked us for our insights about the aroma. She was kidding, but that’s actually what I was going to say. Or all I was capable of saying. I am a novice and so when I stuck my nose in the glass, I was unable to discern or name what I was smelling. It smelled like wine. I’m not sure you can discern what you can’t name. Language causes us to conceive of something. On then can we begin to perceive it and organize our experience of it.

This of course is Cog Sci 101. You perceive based on your knowledge and experience. Experts perceive principles and details—they pick up cassis and blackberries and chocolate. Novices don’t know what they are smelling for really or how to describe it. They say: I smell wine. You understand much less of what you are perceiving when you don’t have experience and background knowledge.

But the wine was tasty and I didn’t mind.

That said I did notice that it wasn’t especially motivating to me to be asked to discern insights about what I couldn’t perceive. It was much more interesting when the winemaker said: “I am smelling blackberries. Some people get cassis. It’s sweet and rich.” That at least let me start to identify and name what I was smelling. With a lot of guidance from an expert I might eventually be able to discern the pattern… but for the most part I was guessing. And my guessing wasn’t critical thinking. Nor was it especially fun for me. Being told things that were useful was more interesting not less. I started to make the first glimmers of connection- to begin to organize the experiences of “smelling blackberry in wine” that in the long run, after a lot more experience, might allow me to quickly perceive its presence. But for now no amount of questions or encouragement about the skill of smelling: “Breathe in deeply; place your nose in the glass; twirl it to release the aroma!” would help particularly. You couldn’t motivate me to perceive what i did not know. Technique wasn’t much help either.

“There are no right answers,” our wine-maker reminded us. And then she said something fascinating. “Let’s say I talked about peaches in this wine,” she said, placing her hand on a white. [What kind of white? I can’t really remember]. “There are people in our group from Chile and from Spain. From the US and from England. To say “the smell of a peach” I am invoking different smells from each of you. A peach quite literally smells different in each of those places. And perhaps some of you have smelled many more peaches than others.”

She was reminding us that we can perceive what we already know. That each of us had a different experience of “peach”… or none at all.

It struck me as she said that that I wasn’t entirely sure what cassis was. And therefore what it smelled like. “Is a cassis like a black currant?” I asked.

One of my colleagues explained that it is a flavoring distilled from currants. If I’d smelled it I didn’t really remember it. And we don’t do a lot with currants in the US. So I would really struggle to smell cassis even if it crawled out of the glass and bit me. Even if it was painfully obvious to most wine drinkers.

To make a long story short, as we discussed on the ride home, it was a case study in perception and analysis. We were given a challenging task: what are the smells? What are the tastes? And even though it was an experience that embraces subjectivity—everyone’s perceptions are their own—it was still profoundly knowledge driven. To the experts it was an exercise in critical thinking, nuance, insight. To the novices it was an exercise in randomness. We learned very little from the ‘experiential” part of the tasting because we could not connect what we perceive to other information in our brains, information we already knew. We learned when someone explained and named things for us. The experts were able to get more out of experiential learning, exactly as the guidance fading effect would have predicted. But there was more tasting than teaching and the gap between novices and experts only widened.

The post A Group of Cognitive Scientists and Teachers Go To A Wine Tasting And…. appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

November 4, 2022

The “Radical” Coaching Approach of Christian Lavers

Recently I attended a coaching symposium (thanks to Tim Bradbury and ENYYSA) where Christian Lavers delivered a “radical” session for players on the principles of defending.

I use the word radical because it was, IMHO, radically good–probably the best coaching session that I can remember seeing for youth athletes from a teaching point of view—but also, quietly and without fanfare, radical in that it questions some tenets of coaching that have become near orthodoxy.

You can see a video of the session below. Please note that it lasted about 75 minutes and I’ve edited down to about 30 minutes here so a lot will be missing and aspects of the session will inevitably be distorted by the shortening- the biggest is you won’t get a sense for how much the girls played. They played a lot. And because I cut a lot of that—to focus on the times when Christian is explicitly teaching–you also can’t see how dramatically they improved in their understanding and confidence quite as dramatically as those of us watching live could.

A colleague said: “You almost never watch a session where you can see such dramatic behavior change across a group like that.” By the end of the session the girls understood principles of defending and were using them successfully to solve problems as a group in a game setting.

Maybe I’ll just write that sentence again in case thunder didn’t clap as you read it:

By the end of the session the girls understood principles of defending and were using them successfully to solve problems as a group in a game setting.

[Boom.]

The video opens with Christian providing a focus for players’ attention: They’re going to be talking about defending, he clarifies. “I want you thinking about three things…” he says, “I’m either forcing wide, organizing centrally or retreating.” Then he reinforces the terms he will use—consistently and reliably—as he will do throughout the session. He makes the girls repeat them so they recognize them and use them themselves. He even quizzed them briefly –what were the three terms? [I cut that for time]

Next, he installs: He starts by setting up a game with small-sided goals. This set up is new to the girls and getting their bearings is demanding from a Working Memory stand point. It’s going to take a few reps to “get” the game enough to be able to think about the tactics. And if they’re they’re thinking about how the game works they can’t think fully about defending. So Christian phases things in. First he installs the game and lets them focus on developing familiarity with rhythms , perceptions, rules, even the details of getting off fast when your turn is done.

Then, when they’re starting to get it, he starts teaching. [We are still very early in the session. That’s one of the key points. The knowledge is delivered first. The problem solving comes when they are asked to use and apply it. When you try to problem solve without knowledge you are guessing. Guessing is not critical thinking.]

He starts with a single concept: understanding how and why to deny space centrally to force opposition to play wide. “Your body is a tool that is going to occupy space and make it harder for the other team to play [there],” he says, “So whenever we lose the ball try to organize a way that its really clear where you want to push them.” Then he lets the girls try it. They played for several minutes which I cut out. His live feedback focused constantly reinforcing their positioning the girls were playing. I’m sure there were a thousand other things he wanted to mention but almost everything he said was to help them see whether they were effective at occupying space centrally as he had just described.

This is another major takeaway. His self-discipline in teaching one thing and then watching for it and giving feedback on that thing (almost exclusively) afterwards. The fact that he concentrates on how and whether they are using the concepts he’s teaching means they are concentrating on how and whether they are using the concepts he’s teaching.

You may not notice it, but things are already pretty radical. Christian is not asking his players to discover how to defend. He’s not putting them in a game and hoping they’ll figure it out it for themselves. There is a lot to know about defending properly and that knowledge has been accrued by coaches over decades. Asking them to infer them would be inefficient—they would be highly unlikely to infer a full set of connected principles correctly- times a thousand when you consider that for defending to work everyone on the team has to understand a shared set of principles in exactly the same way. These things are doubly true because they are green at defending—like many American soccer players they have been explicitly taught very little about defending. They are mostly guessing and valiantlydoing their best without much knowledge. But as one cognitive scientist puts it: what you know determines what you see and what you learn. Novices, in other words, perceive less than experts. They tend to notice superficial details rather than underlying principles. So they are unlikely to infer effectively or efficiently.

So Christian starts by laying out very explicitly in precise vocabulary exactly how a group defends and what they look for to make their decisions. Some people think this somehow means players won’t be asked to think or make decisions but the opposite is true. Christian will say over and over in the session some version of this: “Exactly where you go and you go and you go is going to be different every where on the field in every situation depending on who you play against.”

This is because people confuse critical thinking with discovery. In fact, most of the critical thinking you do in your life comes after you understand a concept. Once you know a set of principles, there is still LOTS of thinking and decision making and discussion to do. In fact the premier league is all about teams with clear game models wrestling to figure out how to apply those models when the other team is deliberately creating challenges to their doing so.

Most of the problem solving in the game of soccer lies in the application of known principles, not in the discovery of new principles. There can be some value in an aha moment- a bit of discovery when a player realizes: oh- I get it now I see why this principle exists but the amount of time that should be spent on such experiences compared to experiences that focus on: now that you know the principle here is how to apply it when the weather is bad or the opposition is doing X and Y and Z to prevent us is preciously small.

As for Christian’s players, they will be doing figuring out their defensive positioning with shared knowledge and shared language. And they will be looking at the same perceptive cues.

Here are some things you might notice:

At 2:43 of the video (9:39 on the onscreen clock) Christian pauses the girls for another dose of background knowledge. He starts to layer in on top of positioning central the idea of denying space and attending to space. They play again.

At 4:20 of the video (12:28 on the onscreen clock) they’re back after a few minutes of lay for a bit more detail: how to close. Here Christian deftly connects tactical knowledge (our goal is to force them wide by occupying space centrally) with technical knowledge: here is how to angle your run optimally. Notice how carefully he models alternative versions of the amount of curl in a closing run so the girls understand the range of possible actions and the why behind the answer he gives them. Now they know what to do, how to do it and why.

Again, they play.

A few minutes later (about 6:40 of the video; 15:44 on the screen) he pauses them again. Now he begins teaching the players how to react to their teammates’ decisions. When they close off one option how do you react as a covering defender. They are learning visual cues to read one another’s behavior and make coordinated decisions.

Next Christian observes carefully for misunderstandings. He does a live stoppage in the case of a player who was too eager to tackle.

After that stoppage I’ve kept a bit of the girls’ live play after this to show how disciplined Christian was about what he reinforced verbally. He talks almost exclusively about things he’s previously explained so girls know whether they are using those ideas successfully.

Close; keep it here; be patient you don’t need to tackleOrganizeWhat angle do you want to press her to?Now a mistake (9:20 of the video; 19:00 on screen). Notice how Christian’s correction simple asks the player to supply the ideas he’s taught her when she makes a mistake and how he asks her what to do and why. His questioning is fast and efficient because they are all focused on a core set of concepts. He’s not asking her questions about things she doesn’t know about so she is able to answer and engage in discussion.

I’ve kept a few snippets of his live feedback here. Notice the self-discipline. Everything he says tells the girls how they are doing at using the concepts he has taught them:

Good reaction. Calm now. Good. She turned it over that’s fine.Think about the angle there. You got over eager.How do we press?That’s a good adjustment.What’s the space you want to take away.Can you turn it?Patient!Good! [notice that because he is so consistent in what he is giving feedback on that it is pretty clear to the girls what he is referring to in w the word “good”

At the next stoppage Christian starts to layer in the third concept (after force wide and organize central) which is “retreat”… notice how he brings in the concepts piece by piece so he doesn’t over load players working memory. The model is: Learn one idea. Try it. Get feedback. Try it again. As you get mastery add a second idea. Try it. Get feedback. As you get mastery add a third. He’s constantly attending to loads on working memory and seeking not to over load players.

Notice by the way how the players are reacting to Christian. They are gradually becoming far more engage intellectually. At first they were hesitant to answer but now that they are beginning to understand they are far more eager to participate and answer questions. Isn’t that interesting. When someone is asking you questions about things you know something about, you are more interested in the discussion than when someone is asking you to guess at things you don’t know about (and they do!).

At 12:20 of the video (27:58 on the screen clock) Christian transitions to a new setting. They start playing in a more applied setting- on a larger more game realistic field … but the concepts are exactly the same and he begins by reviewing them and focusing players’ attention: what are the three things we are working on?

More great stoppages full of rich information about how to play the game follow. The stoppages are conversational—the girls are engaged in discussion and problem solving—but he is not asking them to discover principles. He knows the principles he is teaching. Their thinking is all about how to apply the principles here and now in this slightly new setting.

This is what’s so revolutionary about his session. It’s so intensely knowledge based. He teaches the girls more about how to defend than most would learn in 2 years with a typical club where they have to infer information from settings they don’t really understand. But just because he tells them things—here is how to shape your run when you close—doesn’t mean there isn’t lots and lots of thinking to do. The thinking has just begun, as he reminds them throughout.

That’s the key idea. Christian’s session is a lot like this vocabulary session in which students are also hugely engaged.

One of my favorite teaching moments comes at about 16:10; 33:53 on screen) when he connects tactical and technical with the outside defender. He begins by giving her credit for defending well in a previous seting and then points out that this setting was more challenging. But here Christian is teaching body position in anticipation and in closing. That’s a concept that is often taught in isolation. Here it is connected to a tactical setting and goal. The technical skill helps to achieve the tactical principle; the two are connected.

At 20:00 there’s a quick review before they play full field. Here Christian in a way summarizes the radical idea he’s using for the girls. “Force wide, organize central and retreat: that is the what” he says. That is the shared knowledge we are mastering, as individuals and as a team. “The how,” he notes, “you have to figure out in a billion different situations,” that is, the problem-solving and decision-making start now that you know what you want to do. And it depends on your ability to communicate and read visual cues. If there is a better summary of the role of knowledge in teaching I have not heard it.

I’ll leave the rest of Christian’s session for you to watch and enjoy. For me I keep thinking that if this was what teaching looked like on the soccer field: if we were serious about sharing knowledge about how the game should be played at the highest levels and then worked on HOW–how do we understand deeply what we are trying to do and then how we accomplish it in a thousand different settings when a thousand variables change—we’d be much closer to developing thinking players than if we persisted with the “discovery myth”. The discovery myth is the idea that somehow if we never tell players anything but simply ask magical questions we will unlock the knowledge hidden within players and they will infer the solutions on their own. This is simply not how human cognition works. And the beauty of Christian’s session is that it shows us a way to engage players in lots of thinking and decision making in a more productive and knowledge based model.

The post The “Radical” Coaching Approach of Christian Lavers appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

November 3, 2022

Make editing and revision of student writing visible, precise, and an ‘every day thing.’ (Video)

Teaching writing well is one of the most important things we can do in the classroom as teachers. The ability to capture and idea with precision and nuance is deeply connected to the ability to generate ideas of precision and nuance. And as Judith Hochman wisely points out in The Writing Revolution, there’s a big difference between assigning a lot of writing and teaching writing.

One of the keys to teaching writing well is ensuring that students get and use precise feedback frequently. I tried to write about this is Technique 42 of TLAC 3.0: Regular Revision– ‘the simple idea that we can make student writing better by making revision an everyday act, often done in short simple doses.” That is, we often give and ask students to apply feedback (only) as part of the essay writing process. Using and applying small pieces feedback in shorter pieces of student work daily would be much better.

This video of Fran Goodship and her students at London’s Solebay Academy is a great example of how to do Regular Revision well.

goodship.fran.ratio.mov (Original).mov from TLAC Blog on Vimeo.

As you can see she is projecting Jannatun’s work to the class and she’s asked them to suggest changes. Notice how specific and powerful the feedback is. When Sara suggests that Jannatun should add a conjunction to link ideas, they look at a specific example: the run-on sentence, “I like to play in the park, I like to play tag.” They talk about an exact solution. They see Jannatun apply it correctly.

It’s so simple but one of the keys to making feedback specific and useful is making writing visible via Show Call.

One of the principles of cognitive science that’s relevant here is the “transient information effect.” The idea is that if something is not visible to me, I have to hold my recollection of it in working memory. This gives me less of my very finite WM to apply to analysis or memory building. But so often when we talk about student writing are students are trying to remember it while they talk about it. Someone reads their work and then we discuss it. The result is vague discussion and poor memory of solutions. Here students can see every step of the process: what the mistake looks like; how Jannatun fixes it.

The first step in having a productive and useful shared discussion about writing is to for all of us to see the writing we are talking about, and ideally to see the whole time and especially it as it changes with revision.

Fran does a really beautiful job of that here. She gives Jannatun real ownership through the live editing. And of course Jannatun’s fellow students are doing the analytical work by providing the feedback.

We especially like the way she divides Sara’s feedback into two distinct parts and takes them on one at a time. And the way she solicits suggestions from Jannatun’s peers to eliminate repetition.

Notice also Jannatun’s reaction. She’s totally comfortable with the proceedings. Proud even. Of course she is. The process makes her writing seem very important and meaningful to be studied and discussed like that. It helps that Fran let’s her suggest some of her own improvements and gives her credit for that in front of the class, but she clearly feels the respect implicit in having her work become the focus of the class’ thinking. (Notice also that, as the video fades out, Fran is Show Calling another students’ work…)

The post Make editing and revision of student writing visible, precise, and an ‘every day thing.’ (Video) appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 27, 2022

“Regular Revision”: Write Less; Write Better; Rewrite Daily; Make Writing Visible

Had the pleasure of visiting a couple of really good schools in the midst of “bringing students back” over the past couple of weeks. By “bringing kids back” I mean rebuilding intellectual habits and striving to maximize quality of learning given how much kids have lost in the disrupted previous year(s).

One of the clear themes is writing. The quality of the ideas students get down on paper is always a challenge in school but it’s double challenging now as students mostly didn’t write much during disrupted remote instruction, certainly not pen to paper, and their attentional skills are fragmented. And writing demands attention.

One of the key ideas the TLAC team has discussed with schools is making sure that writing during class promotes rigorous thinking. Writing is powerful as a learning tool in part because it requires a higher level of thought than speaking. You have to attend more intentionally to exact phrases and words. If we can get students to concentrate on getting ideas down well it will help shape thinking. But if they write poorly and with unfocused attention… if they write an idea hastily, capture only part of it and leave things that way, then they won’t benefit as much.

So a lot of our conversations with schools have been about writing less in terms of quantity, but with greater attention and more revision. The techniques Regular Revision and Show Call are critical to this. So below I’ve excerpted some sections from TLAC 3.0 that are especially relevant in addressing the challenge of maximizing the benefits of writing.

Excerpts from Technique 42: Regular Revision (w Technique 13: Show Call embedded)

Most of us submit our own writing to the revision process frequently and, for some of us, constantly. We revise even an informal email to a colleague perhaps, or scratch out and use a different word three times when texting an explanation to a friend about running late. Revision is an everyday thing in the real world but too often a special event in the classroom—a formal activity applied mostly with compositions and longer pieces. It’s often encoded in what some teachers call the writing process, which can take a week to complete, with each step (drafting, revising, editing) getting its own day. Over the course of the year there are perhaps three or four “revision days.”

I’d argue that to make students’ writing powerful and also to allow writing to cause writers to think most deeply—to boost the Think Ratio, that is—revision should always be a part of writing. In some ways the less distinguishable as a “separate step,” the better.

The technique Regular Revision pursues the simple idea that we can make student writing better by making revision an everyday act, often done in short simple doses, and by making it a habit to regularly revise all manner of writing, not only formal pieces.

I find this observation of Bruce Saddler’s profound: “Sentences represent vehicles of communication that are literally miniature compositions,” he writes. We could apply the drafting and revision process reserved for longer compositions more frequently, and probably more successfully, to smaller writing exercises just by thinking of them as compositions, too. Sentence-length developmental writing exercises, for example, are perfect vehicles for revising. Small and focused, they are perfect for successful, deliberate practice.12

Skills are mastered when practiced regularly, even if practiced in smaller chunks. You might call that the Yo-Yo Ma Effect. As a child, the great cellist’s father taught him to play in short, frequent, and intense doses. He played better, and with more attention, because he played shorter. The frequency of practice and the level of focus and attention involved are often more important than the duration in shaping outcomes.13 Five minutes of practice a day for ten days, done with focus and attention, will probably get you farther than an hour of practice on one occasion, even though the number of minutes applied is greater in the second instance. Doubly so if your level of attention starts to tail off at the end of the hour.

Revising smaller pieces of writing more frequently allows for focus and energy. It also allows us to have a single very specific goal for every round of practice—something the cognitive psychologist Anders Ericsson points out as being critical to accelerating learning in practice. If there’s one thing to focus on and improve, it’s easy to see—and then to support people as they apply that particular idea. Let’s add an active verb here. Let’s figure out why this syntax doesn’t work. See the difference between those focused prompts and a more general “revise your paragraph?” There’s a clear task to start with, so students know what to look for and to change; the task then ends with visible progress, giving students the sense of success that we discussed earlier. This will make them want to continue in the endeavor.

…

If you are going to take class time to practice revision, then you need to make sure that both the original student author and the rest of the class (now in the role of “assistant-revisers”) are able to derive meaning from the exercise. Therefore, we need to keep the writing we are talking about in students’ working memory—it must remain visible to them. Show Call does that, enabling a teacher to ask for precise, actionable analysis. If I project Martina’s writing, I can say, “I like Martina’s thesis sentence, especially her use of a strong verb like ‘devour,’” and then use the projected image to point it out for everyone. Or “I like Martina’s thesis sentence, but it would be even better if she put it in the active voice. Who can show us how to do that?” This way, when we talk about what’s good about a particular piece of writing, or how it can be improved, people are not just following along, but are able to actively think about the revision task. Since most of the information we take into our brains comes to us visually, students will now understand and remember the revision you are talking about far better.

Making a problem visible also allows you to ask perception-based questions. Asking a student, “Do you see any verbs we could improve on?” is far better than saying, “Amari has used a so-so verb here, let’s see if we can improve it.” The former question causes students not simply to exercise the skill of improving verbs but to recognize—and practice recognizing—places where it needs doing, where writing could benefit from improvement. Without the critical step of perceiving opportunities for revision on their own, they won’t learn to write independently.

Finally, after leveraging the minds of all the students in the class and eliciting thoughts from several of them on the revision at hand, you can then create an opportunity for all students to apply the learning they’ve just done. “Great, now let’s all go through our sentences, check the ones that are in the active voice, and revise any that are in the passive voice.” Through the use of Show Call, the Think Ratio and Participation Ratio on the revision task has just increased exponentially.

The post “Regular Revision”: Write Less; Write Better; Rewrite Daily; Make Writing Visible appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 21, 2022

New Video: The Art of ‘Means of Participation’

How you ask students to answer a question is often as important as the question you ask. If you don’t get everyone to answer, if you don’t cause everyone to think deeply about the answer, even the best question will only be so useful.

So great teaching relies on clarity about Means of Participation–that’s what we call it when a teacher builds routines so students understand how to participate in a few core ways and then signals to students which to use when.

You can see Teacher McCain of Memphis Rise Academy doing that in this video.

He starts with a bit of Wait Time. He wants students to think deeply about what the first step is in the problem he’s presenting. You can see that they all know how to do this. No one calls out an answer. It’s silent in the room as students reflect. Everyone has the time and space to think.

Then McCain sends his students off to a Turn and Talk. You can see that they know the drill for this Means of Participation too. They have a shoulder partner. They know who it is. They know what it means to chat. You can see also that it is a familiar routine because students Turn and Talk with energy and without hesitation. They know and trust that their partner will be all in. There’s also synergy here. The Turn and Talk goes really well because students have had time to think and so have something useful to say. Of course they’re enthusiastic.

Coming out of the Turn and Talk McCain Cold Calls Tonyia. He does a great job of validating his hand-raisers even while he Cold Calls… and makes it clear that he’s choosing Tonyia because he thinks her answer is valuable. He also uses the phrase “Start us off…” in calling on her. This is one of my favorite pro-tips for effective Cold Call… it implies that Tonyia doesn’t have to be perfect. She doesn’t have to know everything. She just has to provide a useful starting point. And when he calls on a classmate to “build on” to her answer–using that phrase for a follow-on is another favorite pro-tip–it doesn’t seem like a judgment on Tonyia. It seems like learning is a team sport.

It’s really important that students get the content of the discussion down on paper so McCain then reminds students to make sure they are taking notes.

You could imagine a lesson where a teacher asked the same questions as McCain but didn’t get the same levels of participation thinking and collaboration from students. McCain accomplishes those things because he’s so intentional about his HOW students will participate… Wait Time into Turn and Talk into Cold Call into a bit of note-taking…and because he’s made those forms of participation routine. (And also because he’s thought about the sequences he’ll use in advance.)

Hope you liked this video as much as we did!

The post New Video: The Art of ‘Means of Participation’ appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 20, 2022

Combining Cold Call and Wait Time- A Video to Go with the Great illustration

My colleague Bradley Busch and his colleagues at Inner Drive recently posted this outstanding illustration of the way combining Cold Call with Wait Time and “timing the name”–that is, not identifying whom you are calling on until after the question is asked and students have had time to think–can boost the amount of student thinking. (Bradley’s illustration is based on another great visualization, originally by Luke Tayler).

This is important in several areas of questioning but it is–Bradley points out–especially effective when using retrieval practice.

Here’s that thoroughly excellent illustration:

The only way the illustration could be any better would be if there was a video to go with it. And well, that’s where I can help. So here’s a great video of the always outstanding Denarius Frazier using Cold call + Wait Time to make student retrieval practice especially effective.

Some things you’ll probably notice:

1) The warm inviting tone (and smile) Denarius uses to start the retrieval practice.

2) The Wait Time that ensures everyone things through the answer.

3) The Cold Call (Question. Pause. Name)

4) The Turn and Talk he uses when one student answers wrong to ensure that everyone practices that question–and to divert any negative attention from that student.

The post Combining Cold Call and Wait Time- A Video to Go with the Great illustration appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 7, 2022

How Brittany Carson Starts the Year with Show Call

Up here at TLAC Towers, Show Call is one of our very favorite techniques.

Think of it as a visual Cold Call with a whole lot of additional benefits.

In a Show Call you present a piece of student work, chosen at your discretion and regardless of who volunteers, to look at and study as a class.

It’s a great way to study common mistakes and make students feel like they are both normal and valuable.

And it’s a great way to revise and improve written work.

You can see Brittany Carson, a 6th grade science teacher at Memphis Rise Academy doing that–and crushing it!–here:

Not only is Brittany’s Show Call really good but it’s a really effective model of how you might use Show Call early in the school year when you are building students’ familiarity and comfort with the technique.

For example, while you don’t have to make Show Calls anonymous–most of the time we don’t actually–it’s nice to do the first few times you try it just to diffuse any potential anxiety.

Here Brittany does that nicely. Her “take” is super subtle (you can’t tell whose work it is) and she says: “We’re going to look at someone’s work and talk about it a little bit” as if that’s the most natural thing in the world. (We kind of think it should be). But also keeping the author anonymous. It helps that her tone is easy-going and upbeat.

Meanwhile there’s now a system of accountability in place for written work. Message: “What you write might get shared. That’s a good thing. But always do your best work on writing tasks just in case.”

That’s powerful, simple and important.

Showing work you want to edit or have students study is very important! In fact we’d say anytime you want to study student work it should ALWAYS be visible.

That’s because the transient information effect tells us that if we are talking about student work that we are not also looking at, students’ Working Memory will be overloaded and they will not get as much as they could out of the exercise as they could.

For example if Brittany had merely read the student’s answer and asked classmates to suggest improvements, students would have to both remember the original sentence and analyze it and try to remember why and how they’d improved it, all at the same time. This would put an immense load on working memory. (Trying to hold the original sentence in WM would essentially use most of it). They would struggle to do any of those tasks well and would forget most of it. But with the work visible, students don’t have to use WM remembering. They can just study it.

Showing the student’s work, Brittany complements it. It’s good work and she calls out some of its strengths. And then she adds: “What could we add on to this sentence to make it even better?”

What a great phrase: “even better”.. it captures the idea that we are always trying to improve even when we’ve done good work. It reminds students that good work is just the beginning.

Notice though that in addition to studying their classmates’ work and learning form it, Brittany is constantly directing students’ attention back to their own papers, causing them to build a habit of comparing what they see to their own work. For example she says: “If you wrote something like higher or height go ahead and underline that on your paper. Give yourself a check mark.” “If you wrote the word ‘store’ give yourself a check mark.”

Also, as Brittany asks for suggestions she always models how to include them on the sample on the board. They are always applying the feedback. And notice that the students understand that the changes she makes should be mirrored by edits they make to their own paper. But Brittany also reinforces this nicely: “Circle where you wrote the word more. If you didn’t, add it in like i just did to this sentence.”

Notice also how she makes it clear she’s watching to see if they do that: “Thank you, Vanessa. Thank you, Christopher,” is a lovely and appreciative way of saying: “When I ask you to complete a task I will watch to see whether you do it.” This builds a culture of follow-through.

Now students have a model answer in their notes to refer to!

And Brittany’s class is off and running!

The post How Brittany Carson Starts the Year with Show Call appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

August 31, 2022

Exciting New Changes to The TLAC Leadership Team

From left: Williams, Woolway, Driggs, Richard, Lewis

We’re happy to share some exciting news about changes to the Teach Like a Champion leadership team. As many of you know we’ve transitioned to be independent of Uncommon Schools. This is a move that’s designed to give us more operating flexibility so we can emphasize our external facing work and make the greatest possible positive change in schools.

As part of this move, Darryl Williams, who has been co-Managing Director alongside Doug Lemov, will now step into the role of CEO. As those of you who’ve worked with Darryl know, his wisdom and insight about both teaching and the complex work of running great schools is second to none. We’re excited and honored that he will take up the senior executive leadership role in the organization.

Erica Woolway, who has been Chief Academic officer and who has played a key role in building and executing on every significant TLAC initiative, from workshops to our curriculum design, will also receive a significant promotion, now adding President to her title. As you know if you’ve worked with Erica, her gift for ensuring that our work is the highest possible quality will maximize the impact of our work at a critical time for schools and educators.

With the promotions for Darryl and Erica, Doug Lemov will shift his role, taking title of Founder and Chief Knowledge Officer. This change will allow him to focus more directly on the writing and content development work that he loves. He’ll continue to work side-by-side with Darryl, Erica and the rest of the team to bring the highest quality professional development and curriculum tools to teachers.

And speaking of the team, we are also excited to announce that Hilary Lewis and Colleen Driggs will be joining our senior leadership team. As leaders of our Consulting and Partnership and Reading Reconsidered Teams respectively, their perspective, leadership, and input will continue to be invaluable as we grow our work and deepen our impact. We’re excited to welcome Hilary and Colleen to work alongside Darryl, Erica, Doug, and our Chief Video Officer, Rob Richard as we continue on our exciting path forward.

The Teach Like a Champion team takes pride in offering the best training and materials available for teachers and schools, and we think this redesign, which will give our senior executives clearer roles and more distinctive areas of focus, will allow us to continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

The post Exciting New Changes to The TLAC Leadership Team appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Doug Lemov's Blog

- Doug Lemov's profile

- 112 followers