Doug Lemov's Blog, page 10

March 8, 2023

“Are We in Class?” A Glimpse Into Implementation of The Dean of Students Curriculum

Virtues & character also deserve a curriculum

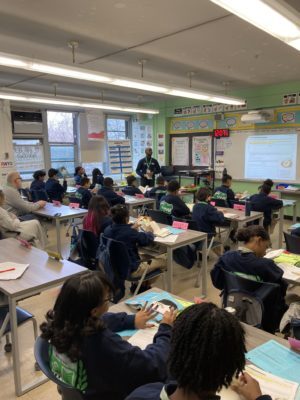

We are excited to share a recent video featuring Tyler Moomaw, math teacher and grade team leader at Breakthrough Schools in Cleveland, Ohio, a pilot partner for our Dean of Students Curriculum. In this video, Tyler is supporting a group of students who have not completed their homework assignments for the week. While there are a number of ways schools can respond when students fall short of meeting expectations or fail to follow through on actions that help them succeed, Breakthrough Schools choose to respond with teaching. Tyler’s goal is to help his students recognize the benefits of routinely completing homework, so this important task becomes habit. His lesson, “The Benefits of Doing Homework,” provides a window into how we might use reading, writing, discussion, and student reflection to teach replacement behaviors for unproductive actions.

It is evident that Tyler has put a lot of effort into preparing for this lesson. He has reviewed the material beforehand and planned for how students will engage during each section of the lesson. It feels like a class–that is a sequence of time dedicated to making students more knowledgeable and successful. In fact, the after school lesson is so well-structured that a student even asks “are we in class?” Students are familiar with consequences in such settings but not with the idea of being taught–really taught, as in caused to think about and understand knowledge that can help them–in such settings.

Tyler demonstrates a range of effective teaching techniques to enhance his students’ learning experience. For example, he uses active observation to gather information and assess students’ understanding. He uses cold call to engage students in sharing their thinking after they have had time to think in writing. Finally, Tyler offers opportunities for his students to revise their initial thinking after they discuss their answers as a group. These strategies help Tyler to keep students engaged and to ensure that they are walking away with a better understanding about the benefits of doing homework.

At TLAC, we believe that teaching virtues and values to support student character development is essential and our Dean of Students Curriculum is designed to do just that. It’s built on the idea that when students struggle to do what helps them succeed, teaching is our first tool. Our curriculum includes carefully curated lessons and activities organized by virtue. Their purpose is to develop students’ understanding of virtue and character through critical thinking, reflection and writing. The curriculum helps students understand the consequences of their actions and learn replacement behaviors for counterproductive actions.

The Dean of Students Curriculum is available for purchase or for piloting. For more information, visit our website: https://teachlikeachampion.org/dean-of-students-curriculum/. We are also excited to announce that a high school version of our curriculum will be coming soon, so stay tuned for that announcement!

–Brittany Hargrove

The post “Are We in Class?” A Glimpse Into Implementation of The Dean of Students Curriculum appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

February 17, 2023

What Is Positive Framing: An Excerpt from TLAC 3.0

Ditch the Sandwich

My friend Ravi Gupta recently interviewed me on the Sweat the Technique podcast and one of the techniques he asked about most was Positive Framing–Technique 59 in TLAC 3.0. His questions made me realize how critical this technique was- how frequently it is at the center of efforts to build vibrant and successful culture, in the classroom and just about everywhere else. So with thanks to Ravi for reminding me, here are some highlights from the discussions of Positive Framing as discussed in the book.

Positivity inspires and motivates and that should influence the way we teach. But positivity, particularly in learning settings, is often misunderstood.

One flaw is the assumption that praise is the same thing as positivity. Praise is telling someone they have done something well. Positivity (in this case) is the delivery of information students need in a manner that motivates, inspires, and communicates our belief in their capacity. This is important because teachers are often told to use a “praise sandwich” or to praise five times as often as they criticize. But telling someone they’re doing great several times so that you can then say And you have to line up your decimals consistently is problematic.

Believing that you must wrap criticism with praise assumes that students are fragile and can’t take constructive feedback—that criticism is something a teacher has to trick them into hearing. Most students want to understand how to get better and come to trust adults who tell them the truth when they also know that those adults believe in them.

Inaccurate or unwarranted praise “is unlikely to stand for long in the face of contrary experience,” writes Peps Mccrea. “Promises of success that don’t eventually materialize will only serve to undermine motivation and erode trust.”

We all know the teacher who’s inclined to describe every idea, every answer, every action as “awesome.” Soon enough that word and his praise more generally become less meaningful. When everything is awesome, nothing is.

Which isn’t to say praise isn’t profoundly important and motivating. It is. But that’s all the more reason to preserve its value.

So the key is often not to praise more. Rather, aspire to give a range of useful and honest feedback and guidance that includes both praise and critical or corrective feedback, but do so positively, in a manner that motivates, inspires, and communicates our belief in our students’ capacity.

Using Positive Framing allows you to give all kinds of feedback, as required by the situation, while keeping culture strong and students motivated. Doubly so for redirections—moments when we say to a student, “Do that differently.” If those moments remind the person you’re talking to that you want them to be successful and that you believe in and trust their intentions, students will trust you more and be motivated to follow your guidance.

Here are six rules of thumb to follow.

Assume the Best

One of the most pervasive tendencies in human psychology is the Fundamental Attribution Error—the idea that, when in doubt, we tend to attribute another person’s actions to their character or personality rather than to the situation. We often assume intentionality behind a mistake.

You can hear this in classrooms where a teacher’s words imply that a student did something wrong deliberately when in fact there is little ground to assume that.

“Why won’t you use the feedback I gave you on your first draft?” or “Just a minute, class; some people seem to think they don’t have to push in their chairs when we line up.” Such statements attribute ill intention to what could be the result of distraction, lack of practice, or genuine misunderstanding. What if the student had tried to incorporate your feedback, or just plain forgot about the chair? How might hearing statements like these make a confused or flustered student feel? Unless you have clear evidence that a behavior was intentional, it’s better to assume that your students have tried (and will try) to do as you’ve asked.

One of the most useful words for assuming the best is forgot, as in, “Just a minute; a couple of us seem to have forgotten to push in their chairs. Let’s try that again.” Given the benefit of the doubt, your scholars can focus their energy on doing the task right instead of feeling defensive.

Further, this approach shows your students that you assume they want to do well and believe they can—it’s just a matter of nailing down some details.

Confused is another good assume-the-best word, as in, “Just a minute; some people appear to be confused about the directions, so let me give them again.” Another approach is to assume that the error is your own: “Just a minute, class; I must not have been clear: I want you to find every verb in the paragraph working silently on your own. Do that now.” This last one is especially useful. It draws students’ attention more directly to your belief that only your own lack of clarity would mean lack of instant follow-through by your focused and diligent charges. And, of course, it also forces you to contemplate that, in fact, you may not have been all that clear.

Assuming the best might give credit for a good idea and then offer the correction: “I like that you’re looking to reduce. But we can’t do that here.” Or “I love to see you trying to use those transition words but there are so many they’ve gotten a bit confusing.” Looking for the good intention behind the mistake, looking to assume the best, has the additional benefit of causing you to think about all the good reasons why students might have done something that at first looks egregious. Assuming well-intentioned errors can help you to see more of the positivity that already exists.

It’s important to remember that you, too, participate in setting the norms of your classroom by describing what you expect. Assuming the best reinforces positive norms (and expresses a quiet confidence). It suggests that you struggle to imagine a universe in which students would not be productive, considerate, and scholarly because of your faith both in them and in the culture of your own classroom. You implicitly describe the norm you believe to be there—everyone making a good faith effort. If by contrast you were to assume the worst, you would be suggesting that sloppiness, inconsiderateness, and whatever else were what you yourself expected in your classroom.

Of course, you’ll want to be careful not to overuse the assume-the-best approach. If a student is clearly struggling—refusing to follow a clearly delivered instruction and is signaling to you that they are in an agitated, emotional state—don’t pretend. In such cases, addressing the behavior directly with something more substantive, such as a private individual correction, also helps to get the student back into a productive mode without the attention of the rest of the class.

Even in the most challenging cases, however—say a student has done something really negative like stealing or belittling a classmate—be careful to let your words judge a specific behavior (“That was dishonest”) rather than a person (“You are dishonest”). Perhaps even say, “That was dishonest, but I know that’s not who you are.” A person is always more and better than the moments in which he or she errs, and our language choices give us the opportunity to show in those moments that we still see the best in the people around us.

Live in the Now

In most cases—during class and while your lesson is underway, for example—avoid talking about what went wrong and what students can no longer fix. Talk about what should happen next. Describing what’s no longer within your control is negative and demotivating. There’s a time and place for processing what went wrong, but the right time is not when your lesson hangs in the balance or when action is required.

When you have to give constructive feedback, start by giving instructions that describe as specifically as possible the next move on the path to success (see technique 52, What to Do).

If David is whispering to his neighbor instead of taking notes, say, “I need to see you taking notes, David,” or, better, because it is more specific, “I should see your pencil moving,” rather than, “Stop talking, David,” or “I’ve told you before to take notes, David.”

Again, the clearer you can be about the next step, the better. As Chip and Dan Heath point out in Switch, “what looks like resistance is often a lack of clarity.” So provide clarity without judgment. If you deliver the directions in a neutral tone, with no frustration evident in your voice, you may be surprised by how helpful it is. Most students want to succeed; by providing them with a clear next step you are helping both of you to get closer to your shared goal.

One challenge here is that we often are too vague in our instructions. When in doubt, shrink the change—a phrase that also comes from the Heath brothers. “One way to motivate action, then, is to make people feel as though they’re already closer to the finish line than they might have thought.” Name a small first step that feels doable. So, “Please start taking notes, David,” becomes “Pencil in hand, please.” It’s much easier for a potentially reluctant or confused student to engage in a task that is bite-size than one that might feel more overwhelming.

For what it’s worth, this is part of the coaching philosophy of the famously positive and successful football coach Pete Carroll, one of the game’s best motivators. “We’re really disciplined as coaches to always talk about what we want to see,” he says of his entire coaching staff’s approach. They always strive to focus on “the desired outcome, not about what went wrong or what the mistake was. We have to be disciplined and always use our language to talk about the next thing you can do right. It’s always about what we want to happen, not about the other stuff.”2

Allow Plausible Anonymity

You can often allow students the opportunity to strive to reach your expectations in plausible anonymity as long as they are making a good-faith effort. This would mean, as I discuss in Chapter Eleven, beginning by correcting them without using their names when possible. If a few students are not yet completely ready to move on with the activities of the class, consider making your first correction something like “Check yourself to make sure you’ve followed the directions.” In most cases, this will yield results faster than calling out individual students by name. It doesn’t feel good to hear your teacher say, “Evan, put down the pencil,” if you knew you were about to do just that. Saying to your class, “Wait a minute, Morehouse (or “Tigers” or “fifth grade” or just “guys”), I hear a few voices still talking. I need to see you quiet and ready to go!” is better than lecturing the talkers in front of the class. This plausible anonymity is another way of communicating to students that you believe the best about their intentions and are certain they are just seconds away from being fully ready to move forward with the tasks necessary to learn.

Narrate the Positive

Compare the statements two teachers recently made in their respective classrooms:

Teacher 1: (pausing after giving a direction) Monique and Emily are there. I see rows three and four are fully prepared. Just need three people. Thank you for fixing that, David. Ah, now we’re there, so let’s get started.

Teacher 2: (same setting) I need two people paying attention at this table. Some people don’t appear to be listening. This table also has some students who are not paying attention to my directions. I’ll wait, gentlemen, and if I have to give consequences, I will.

In the first teacher’s classroom, things appear to be moving in the right direction because the teacher narrates the evidence of student follow-through, of students doing as they’re asked, of things getting done. He calls his students’ attention to this fact, thereby normalizing it. He doesn’t praise when students do what he asks, but merely acknowledges or describes. He wants them to know he sees it, but he also doesn’t want to confuse doing what’s expected with doing “great.” If I am sitting in this classroom and seek, as most students do, to be normal, I now sense the normality of positive, on-task behavior and will likely choose to do the same.

The second teacher is telling a different story. Things are going poorly and getting worse. He’s doing his best to call our attention to the normality of his being ignored and the fact that this generally occurs without consequence. The second teacher is helping students to see negative norms as they develop and, in broadcasting his anxieties, making them even more visible and prominent as well. In a sense he’s creating a self-fulfilling prophecy: he narrates negative behavior into being.

“To modify motivation,” writes Peps Mccrea, “change what … pupils see.” If teachers make “desirable norms”(people doing positive things) more visible to students they will be more likely to join with them. Mccrea calls this “elevating visibility.” To elevate visibility of a norm you want more people to follow, increase their “profusion”—the proportion of students who appear to follow them—and their “prominence”—how much you notice when people do it.

The first teacher is helping students to see more readily how profuse positive and constructive behavior is, and he is making it more prominent to students by letting them know that he sees and that it matters.

Narrating the positive, though useful, is also extremely vulnerable to misapplication, so here are a couple of key rules:

Use Narrate the Positive as a tool to motivate group behavior as students are deciding whether to work to meet expectations, not as a way to correct individual students after they clearly have not met expectations.

If you narrate positive on-task behavior during a countdown you are describing behavior that has exceeded expectations. You gave students ten seconds to get their binders out and be ready to take notes, but Jabari is ready at five seconds. It’s fine to call that out. It’s very different to call out Jabari for having his binder out after your countdown has ended. At that point it might seem as though you are using Jabari’s readiness to plead with others who have not followed through in the time you allotted.

Another common misapplication would be this: You’re ready to discuss Tuck Everlasting, but Susan is off task, giggling and trying to get Martina’s attention. You would not be using positive framing or narrating the positive effectively if you circum-narrated a “praise circle” around Susan: “I see Danni is ready to go. And Elisa. Alexis has her book out.” In this case, I recommend that you address Susan directly but positively: “Susan, show me your best, with your notebook out. We’ve got lots to do.” If you use the praise circle, students will be pretty aware of what you’re doing and are likely to see your positive reinforcement as contrived and disingenuous. And they’re likely to think you’re afraid to just address Susan. In fact, Susan may think that as well. By directly reminding Susan what is expected—and why—you have helped her get ready to engage with the learning and maintained the norm of readiness that is shared by the class.

Challenge!

Students love to be challenged, to prove they can do things, to compete, to win. So challenge them: exhort them to prove what they can do by building competition into the day. Students can be challenged as individuals or, usually better, as groups.

Here are some examples to get you started. I’m sure you’ll find it fun to think of more:

“You guys have been doing a great job this week. Let’s see if you can take it up a notch.”“I love the work I’m seeing. I wonder what happens when we add in another factor.”“Let’s see if we can write for ten minutes straight without stopping. Ready?!”“Ms. Austin said she didn’t think you guys could knock out your math tables faster than her class. Let’s show ’em what we’ve got.”Talk Expectations and Aspirations

When you ask students to do something differently or better, you are helping them become the people they wish to be or to achieve enough to have their choice of dreams. You can use the moments where you ask for better work to remind them of this. When you ask your students to revise their thesis paragraphs, tell them you want them to write as though “you’re in college already” or that “with one more draft, you’ll be on your way to college.” If your students are fourth graders, ask them to try to look as sharp as the fifth graders. Or tell them you want to do one more draft of their work and have them “really use the words of a scientist [or historian, and so on] this time around.” Tell them you want them to listen to each other like Supreme Court Justices. Although it’s nice that you’re proud of them (and it’s certainly wonderful to tell them that), the goal in the end is not for them to please you but for them to leave you behind on a long journey toward a more distant and more important goal. It’s useful if your framing connects them to that goal.

The post What Is Positive Framing: An Excerpt from TLAC 3.0 appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

February 15, 2023

“Polling” As a Prelude to Cold Call

How Many Of You Think This Might Make Your Cold Calling More Natural??

Been thinking a lot lately about how much what a teacher does before a Cold Call shapes its success.

Watch for example how in this clip BreOnna Tindall has her students write a response to a key question, then Turn and Talk to discuss their thoughts. When she Cold Calls the first student to share–he’s a bit of a reluctant sharer usually–he’s prepared and ready. If you want students to be successful with Cold Call, especially when you are first using it, let them write first or discuss first via a Turn and Talk. Or both.

Or watch, here, how Denarius Frazier gives his students about 7 seconds of Wait Time to prepare and study the diagram before he begins asking them about it.

Lately though, I’ve been thinking about another step teachers can take before a Cold Call. Let’s say give your students 30 seconds to think about this question–“What are some reasons why Jonas is feeling anxious? Try to think of more than one.” Then you give students time to think, or write or Turn and Talk.

You next step might be to say: “Ok, how many of you were able to come up with more than one reason? Just show me with your hands.” Maybe three quarters of your students make some sort of gesture to indicate they have thought about the question and came up with an answer. Their signal to you affirms that they have thoughts they can share, that they are prepared. A simple nod and “Great, Kevin tell us one reason you came up with…” starts the conversation. It’s a Cold Call but it feels natural and easy.

You can see Brittany Moore do a version of that here. After one student responds to her question she asks the class, “What do you think?” They make a gesture to show they agree, disagree or want to build on their classmate’s idea and this signal, which again affirms they they are prepared and have something to say, facilitates an easy, positive, natural Cold Call.

This idea–of asking students or participants to make a gesture affirming that they have thought about a question and have an answer, could be used in a variety of ways and settings…

For example:

“Take ten seconds to try to think of at least two times when there is a phase change in the water cycle.” [Pause for Turn and Talk or just wait time] “Ok Great. How many people thought of at least one? Ok. Good Work. Larissa, let’s hear yours…”

Or:

“How many agree that Sarah is being brave in this scene? Oh, interesting, Cherise, tell us why.”

Let’s call this idea “polling”–asking participants to signal back to you whether they agree or have answers or have noticed something. As a prelude to Cold Calling, polling can make the process more natural and the environment much more interactive.

Another place this could be useful is in settings where participants tend not to raise their hands and therefore it’s either Cold Call all session long or answer the questions yourself. This is often the case of settings with adult learners. Film sessions among professional athletes are this way for example. The athletes studying film rarely raise their hands and the awkwardness of Cold Calling without hands often wears on coaches. Asking for a signal–“How many people saw something we could improve in in our defensive shape?” more or less makes a proxy for hand raising and makes it easy for me to call on a wide range of participants naturally and easily even when they don’t offer to share.

The post “Polling” As a Prelude to Cold Call appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

February 1, 2023

Little Things We Loved About Spencer Davis’ Retrieval Practice

Erica Woolway and I had a great visit to University Prep Middle School in the Bronx yesterday. What a warm and positive school with real rigor and a focus on knowledge. Kids focused, worked hard, took pride in their learning and seemed genuinely happy.

One of the classes we especially loved was Spencer Davis’ sixth grade English class, where they were reading Wonder–and by the way using the unit on the book from the Reading Reconsidered curriculum.

Erica managed to shoot some video of Spencer’s retrieval practice at the start of class and there was so much we loved about it–it was typical of things we loved about his teaching and about the school more broadly.

First, here’s the video

Big picture: Spencer’s Retrieval Practice starts with writing and then uses Cold Call and discussion to elaborate on initial answers. What you see here is students sharing and discussing and refining answers after they’ve written responses to each question. He uses a lot of Cold Call to make sure everyone is attentive and listening and thinking, and a lot of Right is Right to refine and improve answers. Students are constantly “building off” of one another- being asked to discuss one another’s thinking as they build long term memory of core concepts in and knowledge from the book. But so much of what makes the retrieval practice sing is in the details. Here are some of the little things we loved:

We loved the way Spencer used little phrases to make the tone light and playful. Notice how when he asks what an anomaly is his pacing is playful, almost musical, and he Cold Calls a student by saying, “Take it away…”We loved his easy relaxed body language and use of gestures to make his Cold Calling seem especially warm and positive. Watch him when he smiles and says, “Define empathy…” or the curlicue gesture he makes when asking about the book’s nonlinear narrative.

He uses a similar easy, playful style when a student freezes for a moment: “Read what you wrote on your pa-per…” he sings.

It’s hints of playfullness and warmth that he relies on a lesson that is still rigorous and serious about learning. The constant grace notes, the little belonging cues he uses, work because he is so focused on learning. They never distract him from the task–he writes out the definition of anomaly carefully because understanding it, as he might say, “precisely” and not just vaguely is really important–and in fact those belonging cues would be less effective if the vibe wasn’t scholarly and focused–if the goal wasn’t top-quality answers. Warmth and camaraderie are not antidotes to hard work. They’re how they get work done in Spencer’s class. “Who is the narrator in part 6. How do you respond to this change in narrator? Turn to your bestie beside you. You have 60 seconds,” he says. It’s just a pinch of levity (and reminder that you are cared about in his classroom) sprinkled in briefly. He doesn’t have to overdo it!

We love the moments where we connects the retrieval to the class’ previous experiences. For example: “Number six. Describe Justin’s voice as a narrator. This one was a fun question. We had a lot of fun discussing it the other day…” The fact that they have already discussed the idea, that they are now reviewing it to make sure the takeaways from the discussion are encoded in their long-term memory, is a good thing. Reviewing it shows how important what they talked about was and that the retrieval practice is connected to the rest of their study of the novel. But it also causes students to recall their shared experience of the previous discussion- they liked talking about the book; they were connected. It’s a reminder of some of the good–and scholarly–times they’ve had together.

We could keep going. It’s delightful teaching- real scholarly work lit by the glow of connection and belonging cued by tiny details that Spencer deftly sprinkles in as he works. And frankly you can hear the effect in their answers. How rich and thoughtful they are–it’s their second time through the material–their ideas are getting good–and how they seem to take pride in being able to describe complex ideas with clarity and precision.

More classrooms like this, we say! Thank you to Spencer and everyone at University Prep for opening their school to us!

The post Little Things We Loved About Spencer Davis’ Retrieval Practice appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

January 31, 2023

Little Tiny Belonging Phrases: A Highlight From My Visit to University Prep

Great visit to University Prep Middle School in the Bronx today where I had the pleasure of watched several English lessons. It was my first visit to University Prep and my notes describe the culture over and over in words like positive, warm and upbeat. At the same time instruction was rigorous and efficient.

(This for example is always a very good sign in a school):

On net, University Prep students worked hard, were attentive, learned a lot, took pride in their work and seemed very, very happy.

Kudos to ED Andrea D’Amato, Principal David Patterson and all of the staff.

That said it was Spencer Davis’s class that took the cake for me.

In addition to Spencer’s commitment to knowledge and precision–he was always pushing students to develop their peers’ thinking–I was struck by the tiny belonging phrases he used at moments when he set expectations or established accountability in particular.

For example:

Giving a direction. Not just “Pencils down,” but “Pencils down, guys,” with warmth and a smile–but clear scanning for follow-through when he said guys.

Or Cold Calling: “What is an anomaly? Take it away, Issa!” That little playful phrase “take it away” made it seem fun and playful. And like an honor to be Cold Called.

When a student was stuck and couldn’t answer: Singing: you can read it from your pay-ay-ay-per

Another cold call: “I’m Gonna pick someone with my eyes closed because I know you can all do this.”

Or this Turn & Talk: Turn to the bestie beside you and discuss for thirty seconds. [Beeping of the stop watch] Go!

He didn’t use little phrases like this every time… just sometimes…and he wasn’t over-the-top and sing-song-y and too sweet. He kept his voice pretty modulated. He just constantly used little phrases to make his students feel connected and cared about even as he used every tick in the book to make them think about every question.

Then there was the constant use Cold Calls to socialize listening and to cause students to show they values their peers’ comments: “Please build off of X’s comment” or “Who can develop Y’s definition of ‘nonlinear narrative’ even more?”

These tiny little reminders: I care about you. You are important here. At exactly the time he was enuring an efficient and productive learning environment jumped out at me. Both are acts of caring and they worked better in synergy… each was more effective because he was doing both at the same time. The little belonging phrases were better because he so clearly took students learning and achievement seriously. When he pushed students to go further with an answer it felt supportive because of the warm upbeat tone.

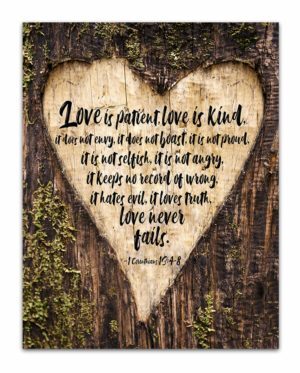

Here’s Spencer with his students reading (and loving) the book Wonder.

The post Little Tiny Belonging Phrases: A Highlight From My Visit to University Prep appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

January 22, 2023

A Slightly Annotated Willingham on Science of Reading

UVA cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham and Barbara Davidson of Knowledge Matters were on the Melissa and Lori Love Literacy podcast a few days ago. Over about ten minutes into the discussion, Willingham gave a fantastic explanation of the role of background knowledge in reading comprehension. I transcribed the key sections below with a few notes of my own [in italics] added in for amplification or emphasis.

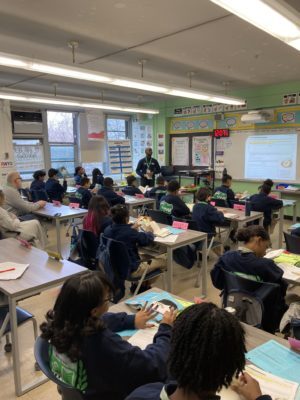

Willingham: The key feature of not just written but oral language is that language is sometimes [you might even say ‘always’ or ‘inherently’ I’d argue] ambiguous. And frequently a good deal of information that the speaker or writer intends their audience to understand is actually omitted. And it is in resolving his ambiguity and replacing that missing information that reader knowledge is so important. [The term for resolving this inherent ambiguity is: disambiguation. And (epiphany here): we are always disambiguating the language we read and hear]

Willingham provides an example sentence made up on the spur of the moment: “Lori tore up Melissa’s art work. She ran to tell the teacher.” He goes on:

The second sentence is ambiguous. “She” could refer to Lori or Melissa. But clearly if you’re an experienced reader [or listener] you’re not going to see that as ambiguous. You’re going to understand that you run and tell the teacher not when you are the perpetrator of a crime but when you are the victim of a crime. So that’s how “she” gets disambiguated. That obviously depends on some knowledge of the world. But pretty much everyone listening has that knowledge so it [the disambiguation] is simple.

This is an example of grammatical ambiguity at the level of the individual sentence. Once you get to making inferences across sentences … knowledge is even more important.

Willingham provides an example sentence from his book: “Tricia spilled her coffee. Dan jumped up to get a rag.”

If all you understood was the literal meaning of the two sentences you probably would not have understood everything the author intended. The author intended for you to draw a causal connection between the sentences: Dan jumped up because Tricia spilled her coffee.

But…you need to have the right knowledge to build that causal bridge. You have to know that when you spill coffee it makes a mess. You have to know that rags can clean up a mess. And so forth.

All of this is just stuff that the writer left out. The reason authors write this way [and speakers speak this way] is that if you actually gave all that information, the text would be impossibly long and boring. [Epiphany: the gaps the author leaves and that cause challenge for readers with knowledge gaps are a feature not a bug of language]. “Tricia spilled coffee. Some of it went on the rug. She did not want coffee on her rug. the rug was expensive.”

Willingham notes this would be absurd.

Knowing your audience means tuning what you say and write to provide as much information as your audience needs, but not more. [Every author is making assumptions about optimal knowledge of readers required to a) disambiguate and then b) understand at a substantive level what he/she is saying.]

Willingham next discusses the Recht and Leslie “baseball study” and then goes on to describe a second study by Ann Cunningham and Keith Stanovich:

“Who is it that does well on reading comprehension tests? Cunningham and Stanovich asked that questions in a series of studies. [The hypothesis was that “the kids who know at least a little something about lots and lots of topics would test well].

Most things you read that are for a general reader, the author is not going to assume you know a whole lot. They’re not going to assume you know that Picasso was a cubist, but the are going to assume you know that he was an artist and a painter. So you need to be a million miles wide but only a couple of inches deep to be a good reader [that is, to succeed on reading comprehension tests; though to be fair that only applies if you are a fluent reader with flawless decoding and if you also have knowledge of vocabulary]. So they tested that–a test of broad knowledge –who was Picasso etc?–this was with college students–and then they administered a general reading comprehension test. And they expected a strong correlation and that’s exactly what they observed.”

I thought that was a really elegant and clear description of the role knowledge plays in comprehension of text. We (or I) often think focus more on the role of background knowledge in bigger inferences in the text–the ones an author might deliberately place allow to exist in a text. But really its critical role is in the constant and perpetual process of disambiguation.

The post A Slightly Annotated Willingham on Science of Reading appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

January 19, 2023

Daniel Buck on Embedding Nonfiction in Writing Tasks

Useful for marriage; useful for essay writing

I’m reading Daniel Buck’s excellent “What is Wrong with Our Schools” and want to share an idea that’s really useful. In chapter 3, Buck discusses the power of supplemental texts in reading.

This is something my colleagues and I refer to as ’embedded nonfiction.” Erica Woolway, Colleen Driggs and I have a chapter on it in Reading Reconsidered and we use it extensively in designing our curriculum by that name. The idea is that adding short nonfiction texts throughout a primary text can infuse it with just the right background knowledge at just the right time so that students learn more and find the book more interesting–more accessible and with far more rich and interesting connections.

Buck gives the example of reading an article on surveillance of citizens in current day China, say, while reading The Giver or an article on narcissistic personalities while reading The Magician’s Nephew. Or you might read an article on how subjective and manipulable memory is while reading Animal Farm as Emily DiMatteo does in this great video example.

Buck’s discussion of the topic–and how satisfying the “need for knowledge” brings the book to life for readers–is excellent. But then he goes on to a new topic–embedding supplemental texts in extended writing prompts.

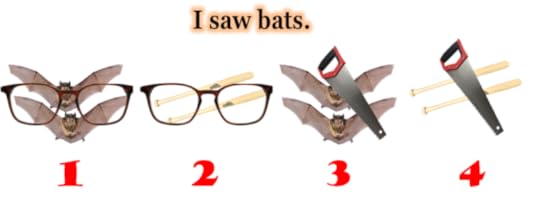

“The same need for knowledge applies to writing… With Romeo and Juliet, my final essay tasks them with answering the simple question: is this a love story? Before asking them to do that, however, we read various passages and theories of love so they needn’t rely on whatever philosophy of love they happen to have picked up from popular media. I read with them the famous wedding passage from Corinthians (“Love is patient; love is kind…”); excerpts from Lewis describing how love cannot simply be an emotion but requires action; a scientific explanation of the chemicals that pass through our brain as we fall in love; and a short reading about the different words the ancient Greeks used for love… [phila, eros, storge and so on]. Only having read these pieces do I feel comfortable asking my students to answer [the question] in long form.”

Reading that passage was a bit of an epiphany for me, honestly. First it invoked a brief memory of my least favorite class in college: Philosophy. We were continually asked to write on broad and seemingly intractable questions about which I had a few general notions and a lot of uncertainty. What I didn’t have was the vocabulary to lock down the vague beginnings of ideas I had in specific concepts I could come back to or other people’s previous reflections that narrowed the issues to manageable points. It was broad, sweeping, and every question felt like a party trick. I hated it and never took another course or read another book in philosophy for the rest of my life.

What do you think? What is the nature of freedom? Answer from your soul. Nothing you say is wrong.

You could call this intellectual “freedom” I guess–that’s what we often call it with students, the freedom to write about whatever you want–but actually it’s much less freeing than being asked to discuss something you have the technical terms and foundational ideas to make sense of.

Saying: here are some words that will be useful to you. Here are some key ideas from history you can draw on as you write is a bit like memorizing math facts. And I mean that in a good way-in an, it’s central to critical thinking but many educators overlook it and misunderstand this kind of way.

If you are automatic with your math facts it enhances your critical thinking and the depth of your analysis. Factual fluency and deep understanding go together. If (and only if) you are automatic with your math facts, you can think about easier ways to solve a problem or understand the similarities of two problems. But if you are just trying to work it through on the most basic algorithmic level your working memory is stuck on the more mundane tasks.

So too in writing. If you have to frame and name of a core idea you seek to discuss it’s exhausting, not that enjoyable, and you spend your time on mundane tasks not richer deeper analysis. If you can quickly draw on Lewis’s conception of action or the Greeks’ parsing of different names, you get beyond the surface much more quickly.

Anyway, in our Reading Reconsidered curriculum we often ask–what else do students need to know to get the most out of reading this book? And now, thanks to Daniel Buck, we will being asking–what else do students need to know to get the most our of the experience of writing this essay?

The post Daniel Buck on Embedding Nonfiction in Writing Tasks appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

January 13, 2023

4 Ways of Looking at a Turn and Talk: How Kris Shukla Uses and Adapts the Technique In His Teaching

Our colleague Ben Rogers at Paradigm Trust, which runs seven school in London and Ipswich, England sent us some video recently of a really well design lesson by Kris Shukla. In the course of a lesson on scientific writing, Kris used four Turn & Talks. Each one was a little different and each one was carefully crafted to meet the demands of a given moment in his class. Comparing and contrasting what Kris did with all four is a great way to study both the key ideas of the technique and some of the important ways it can be adapted. In this blog post you’ll be able to watch each of Kris’ Turn and Talks and read what different members of the TLAC team noticed about them.

Turn and Talk #1 (Colleen Driggs and Sadie McCleary):

The objective of Kris’s lesson is for students to understand features of a scientific text so they can use them in their own writing. So Kris starts by giving students an opportunity to discuss the features of scientific writing they observed in a text they’d read the previous day. “You’re going to have a 40 second talk with your partner about what scientific writing should be. Use this sentence starter: ‘Scientific writing is…’” he says, and off they go.

It’s a well executed Turn and Talk–the room bursts to life–and clearly a system that’s been taught and practiced in Kris’s class. But activity is not enough. What matters, Héctor Ruiz Martín, Director at the International Science Teaching Foundation, recently told our team is that students learn what they think actively about. From a cognitive psychology stand active thinking is what should define “Active Learning” and Ruiz Martín advises that teachers should design tasks carefully to cause students to think about what we want them to remember or learn.

In this case, the sentence starter Kris provides focuses his students so they get right to work thinking in the most productive ways. And since he’s written in on a piece of chart paper he can then track and emphasize the key ideas in their responses so students think about them even more.

Useful takeaways: Start Turn and Talks with a sentence starter or intro phrase to focus discussions; chart student responses after.

Turn and Talk #2 (Darryl Williams):

In this second Turn and Talk sequence, I was struck by the subtle, but important ways students are experiencing signals of connection and belonging in Kris’s classroom. When Kris calls on Isabella after the Turn and Talk notice how her peers all turn, lean in, and lend her their eyes. The use of “we” language here, “We’re going to come to you…” is a reminder that learning in this classroom is a shared endeavor. It’s a learning community. It’s also a cue to Isabella’s peers that they have a responsibility to help her feel part of the community by show interest and respect. In this moment, students want Isabella to know her ideas are important, that she should feel safe to share them, and that she’s a valued member of the community.

Kris further amplifies these signals when he leans in to listen more intently as Isabella shares, subtly nodding and lifting his brow to acknowledge her response. “Good…Thank you, Isabella!” He wants Isabella to feel seen and valued. He’s affirming and encouraging, making it likely that Isabella and her peers will continue to feel comfortable sharing ideas and insights with their peers. This is how belonging is built, by students frequently experiencing small, and often subtle, gestures that help them feel seen and important members of a larger community.

Notice two small similarities to the first Turn and Talk. 1) Kris uses a nonverbal gesture to students to cue the Turn and Talk. It’s a fast and efficient way to start the activity and it ensures that the last thing students hear before they start talking is the question they are intended to discuss (rather than directions). 2) Kris again uses a sentence starter here to focus student thinking. This one is verbal instead of written, a useful variation, but Kris begins: “An introduction should include…”

Useful takeaways: Make sure to use your own body language & facial expressions to show students you value their ideas; ask students to look at each other when they share their ideas so those ideas feel important; consider a nonverbal cue to start Turn and Talk.

Turn and Talk #3 (Dillon Fisher):

Kris is so thoughtful in how he thinks about his pacing throughout the Turn & Talk. Kris takes his time in launching the Turn and Talk. He slows down his pacing to ensure students hear the directions and understand the task: where to focus, what specific question to talk about. His classroom culture feels both calm and clear. He balances that intentional launch with much faster pacing during the Turn and Talk. In this case it’s a simple question and he gives students just 5 seconds to discuss (vs 40 seconds and 30 seconds respectively for the previous Turn and Talks). The variation in length keeps things interesting and the energy high. Kris ensures the partner conversation is buzzing– and that he brings students back with enough thinking left over to share full-group.

It also seems quite likely that this is an unplanned Turn and Talk–that Kris uses it to build engagement among students. When he initially asks the question about parentheses he notices that only three hands go up. Kris instinctively sends students into a short and tidy Turn & Talk – and in just a few seconds he is able to boost Ratio and confirm that all students understand the purpose of parenthesis in scientific writing.

Finally, Kris is an active listener while his students Turn & Talk – and he uses what he hears to make informed decisions that support both understanding and pacing. In this case, Kris hears almost 100% of his students share the correct purpose of the parenthesis. He doesn’t need to take extra time with an additional Cold Call here, so he stamps the learning efficiently and clearly. “I heard it collectively from everybody, they help us to add more information.” The data here tells him that further discussion isn’t necessary.

Useful takeaways: Be attentive pacing and variations in pacing, especially how long you allocate to the Turn and Talk and to the subsequent discussion. Listen carefully to students during Turn and Talk.

Turn and Talk #4 (Beth Verrilli):

We LOVE the idea of using a Turn and Talk to reinforce fluency and prosody (reading with appropriate rhythm, stress, and tone) in reading via a partner read! There’s an immense amount of data on the importance of reading fluency and 1) it’s often overlooked 2) it can be especially challenging with scientific writing.To practice fluency & prosody, students need multiple at-bats reading aloud, and Kris’s Turn and Talk ensures the two rounds of participation each. This is also where Kris’s attention to belonging pays off—in a classroom where Turn and Talk is the norm, students will trust each other and feel comfortable practicing with each other. Kris has created an environment of psychological safety for his students.Because this Turn and Talk is more complex—each student will read two different times—Kris stream lines the directions and identifies which partner should go first. To help support prosody development Kris highlights “two pieces of punctuation to really think about where you’re pausing.” He also projects the passages on the whiteboard and hands them out in hard copy. His directions on the whiteboard also will help keep keep students on track during a complex task, even if Kris is listening to another group.

Useful takeaways: Use Turn and Talks for partner reading to build fluency and prosody. For complex tasks provide more structure (i.e question on the board; identify the student who will go first).

The post 4 Ways of Looking at a Turn and Talk: How Kris Shukla Uses and Adapts the Technique In His Teaching appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

January 10, 2023

On Happiness…and Happy Students

Gratitude, Social Connection, Altruism

Happiness is one of the most misunderstood of human emotions. My colleagues Denarius Frazier, Hilary Lewis & Darryl Williams and I write about this in Reconnect: Building School Culture for Meaning Purpose and Belonging.

Many people define happiness as meaning roughly the same thing as “pleasure.” They assume students will be happy if they are “having fun.” But research (especially that of Martin Seligman) suggests that happiness actually consists of three things for most people: pleasure, true, but also engagement and meaning. When we are engaged in activities that make us feel a sense of purpose and connection we are happy. In fact, Seligman found, engagement and meaning correlate more strongly to happiness than mere pleasure.

This is a theme that Shawn Achor strikes in his book The Happiness Advantage and in this interview with Zack Friedman.

I define happiness as the joy you feel growing toward your potential. This definition is actually crucial; otherwise, we pursue happiness the wrong way. If happiness is pleasure, it is short-lived and increasingly hard to get. But joy is something you can experience even when life is not pleasurable… This is the joy you use to fuel yourself to see your true potential.

I think that’s really useful for schools to think about. Young people are made happy by meaning and engagement more than pleasure. By feeling connected to and part of the group and also by pursuing and accomplishing real goals. Want to make your class happy? Challenge them. Cause them to work hard. Make them feel like a team. Socialize them to them make small sacrifices for each other and the community–and thus become more connected to the community (we are connected this is to say, by what we give as much as by what we get).

There’s more. Friedman asks Achor what the three best ways to create happiness are.

Achor’s response might surprise you.

Gratitude, social connection, and altruism. You can transform any event or environment by being grateful for it. The greatest predictor of long term happiness is social connection. And altruism creates the greatest return on your investment in terms of positive actions. All three require effort, habit and discipline, but they pay off by making happiness easier.

Gratitude, he writes in The Happiness Advantage–and we discuss in Reconnect–creates a “cognitive after image.” If you make a habit of looking for things to be grateful for, that are good in your life, you start to see more of them. You feel better about the world. You notice that you live in a place that loves you. And this causes you to be far more likely to thrive.

This is interesting because schools often do the opposite. They ask young people to look for the ways they have been hard-done by the world. They are often blind to the beneficial aspects of altruism. They ask students to think about what they can take or what they deserve, not what they can give and what they owe. Regardless of what you think about their actual place in society–true that they might be hard done by; true that they might be owed–it is better for them psychologically to focus them on gratitude, social connection and altruism.

Much of Reconnect is about wiring those things into the fabric of schools with the specific purpose of making the places that are psychologically beneficial for young people.

The post On Happiness…and Happy Students appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

December 14, 2022

The Double Gap: How Luke Gromer Uses Video to Develop Young Athletes

A few weeks ago Luke Gromer of Cutting Edge Coaching and I ran an online workshop for coaches on the topic of using video to develop athletes.

The rationale for the session was that video is a powerful tool for building tactical and technical understanding and–through shared discussion–mutual understanding of principles across a group of athletes.

The proliferation of video and improvements in its quality and functionality recently represents a significant change in the landscape of elite athlete development. Video has become exponentially cheaper and simpler to use and therefore exponentially more common.

Result: the contemporary athlete spends an immense amount of time studying video, and the ability to learn from that video is a key driver of success for both team and individual.

However, the degree to which athletes succeed in learning from video has not necessarily increased at pace with technological advances. In fact, the rate of learning has little to do with the sophistication of the video on offer, and one could argue that the more sophisticated the technology, the more teams are likely to be distracted from the core interactions that cause people to learn: what happens to the mind of the viewer in the room where he or she is watching.

The process of shaping what happens in the minds of athletes when they watch–teaching, this is to say–is likely to determine athletes’ rate of development more than the attributes and quality of the video itself. So our focus was on how teach using video.

Here’s a great video of Luke in action with one of his teams that exemplifies several key idea we think are important.

First notice that Luke shows the video three times to his players! Video is information-dense and easily overloads working memory. Especially when you are first watching it and just trying to orient yourself to the basics of what’s happening. Luke realizes he’s seen the video five or six times and knows it frontwards and backwards but his athletes are brand new to it. He has the patience to let them watch it through one before he teaches from it.

He’s also chosen his “pause points” really carefully. He doesn’t ask them to make sense of the whole video all at once but breaks it up into small pieces. What they are looking at when they answer questions is critical because it is developing their perceptive abilities. Luke’s planned that in advance. What will I ask? When? What will my athletes look at while they try to answer?

Notice also who’s doing the cognitive work. So often the study of video for athletes involves a coach at the front of the room doing play-by-play… “Ok, guys. See this? See this? See this and this and this? The answer is, No, coach, they don’t. And if they see it they will soon forget it unless they do some thinking about it. So Luke designs his session to make players work hard cognitively!

And notice how strong his culture of error is: The content is new he reminds them. They’re not expected to get it all right away. If they struggle, ok, no problem. We’ll just work hard and build our understanding step by step.

Maybe a final thought: Notice how attentive to vocabulary Luke is. The terms he uses to describe how they play–gaps, the kinds of cuts, the names for the positions–those things are critical as they will allow them to talk about those concepts as a team during practice and games. His consistency in using precise terms (and asking his players to also) accelerates the degree to which they can transfer what they learn from the video to future on-the-court settings.

Fantastic stuff from Luke!

The post The Double Gap: How Luke Gromer Uses Video to Develop Young Athletes appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Doug Lemov's Blog

- Doug Lemov's profile

- 112 followers