Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 67

August 19, 2012

Pussy Riot, freedom of expression and Western hypocrisy

The verdict in the Pussy Riot trial in Moscow is significant in what it reveals about Christianity and culture. Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Yekaterina Samutsevich, and Maria Alekhina were sentenced to 2 years in jail for their part in an uninvited performance of an obscene and blasphemous song in the Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Moscow.

Many Orthodox Christians, in Russia and elsewhere, have said that

The Pussy Riot group were wrong to perform in the cathedral as they did

The prosecution and trial did more harm to Orthodoxy than the group themselves did

For more on that see Pussy Riot — the verdict.

But the reaction of the Western media and politicians and others is also very revealing, though it reveals far more about Western society and culture and values than it does about Russia. Consider this, for example: iafrica.com | world news | ‘Pussy Riot’ verdict slammed

“The United States is concerned about both the verdict and the disproportionate sentences… and the negative impact on freedom of expression in Russia,” said State Department spokesperson Victoria Nuland.

“We urge Russian authorities to review this case and ensure that the right to freedom of expression is upheld.”

Amnesty International, a formerly-respected human rights organisation, really went over the top when it urged its members to send protest letters to Russia with the following wording:

Amnesty International has declared these women to be prisoners of conscience, for they are detained solely for the peaceful expression of their beliefs. Therefore I respectfully urge you to immediately and unconditionally release Maria Alekhina, Ekaterina Samutsevich and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova. Furthermore, I call on you to immediately and impartially investigate threats received by the family members and lawyers of the three women and, if necessary, ensure their protection. Whether or not the women were involved in the performance in the cathedral, freedom of expression is a human right under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and no one should be jailed for the peaceful exercise of this right.

You just have to Google for “Pussy Riot” and “freedom of expression” or “freedom of speech” to see how widespread this was. The Western consensus, among politicians, the media, and celebrities, at least, is that Pussy Riot did nothing wrong, they were simply exercising their right to “freedom of expression”.

And it’s all sanctimonious, hypocritical twaddle.

The Western media would be better advised to be concerned with their own freedom of speech, because many of them were too chicken to even mention the name of the band. How’s that for freedom of expression?

P*ssy cat, P*ssy cat, where have you been?

I’ve been to London to visit the Queen

P*ssy cat, P*ssy cat, what saw you there?

I saw a little mouse under a chair.

We see what we want to see, and in this case the little mouse seen by the Western media and celebrities is called “freedom of expression.”

Let’s imagine that the boot was on the other foot, and that a punk collective like Pussy Riot stormed into the studio of a broadcasting group like the BBC or CNN or Sky News, and took over, replacing the scheduled broadcast with such a song.

Let’s imagine that the boot was on the other foot, and that a punk collective like Pussy Riot stormed into the studio of a broadcasting group like the BBC or CNN or Sky News, and took over, replacing the scheduled broadcast with such a song.

They would, of course, not be arrested, or even asked to leave, because they would simply be exercising their right to freedom of expression.

And if they marched into a newspaper printing works, stopped the presses, took off the plate for the front plage of the next edition, and substituted one of their own, they would simply be exercising their freedom of expression in terms of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. And the same would apply, of course, if they hacked the web site of an online edition of any news organisation. Go ahead and do that, if you like, because the Universal Declaration of Human Rights says that you have the right to freedom of expression.

Or what if a group like Pussy Riot stormed into the B ritish Houses of Parliament, ot the US Capitol in Washington, and performed such a song there? Of course we know that the United States would be so concerned to uphold their right to freedom of expression that they would never be arrested, much less charged with an offence. The Western politicians who have spoken so sanctimoniously about the right to freedom of expression would never do anything so wicked as to restrict the freedom of expression of anyone who entered the hallowed debating chambers and expressed themselves as freely as the members of Pussy Riot did in the Moscow Cathedral, would they? Of course they wouldn’t. They are not like the wicked wicked Russians. They uphold freedom of speech.

And as far as Wikileaks is concerned…

… Pretoria is best, of course, at jacaranda time.

August 17, 2012

Pussy Riot — the verdict

It is now public knowledge that the three members of the Pussy Riot punk group who performed uninvited in a Moscow cathedral have been sentenced to two years in prison for what has been variously described as “disorderly conduct” or “hooliganism” Anger as Pussy Riot Jailed for Two Years | Russia | RIA Novosti:

Anti-Putin punks Pussy Riot were sentenced to two years each in a penal colony on Friday over a protest in Moscow’s largest cathedral, the decision sparking a demonstration outside the court and warnings of a growing divide in Russian society from opposition figures.

Judge Marina Syrova ruled the three women’s February performance of a “punk prayer” urging the Virgin Mary to “drive Putin out” was “hooliganism aimed at inciting religious hated.” Only a jail sentence, she said, could “correct” them.

In other posts I have commented on their actions, and different Christian responses, but I have not commented on the trial itself. But now that the trial is over, it is possible to do so. I have refrained from doing this before because the matter was sub judice, and it was better to await the outcome of the trial before commenting on it.

In other posts I have commented on their actions, and different Christian responses, but I have not commented on the trial itself. But now that the trial is over, it is possible to do so. I have refrained from doing this before because the matter was sub judice, and it was better to await the outcome of the trial before commenting on it.

Apart from the sentence of two years’ imprisonment, which seems excessive by any standard, the prosecution has actually damaged the church and brought it into disrepute far more than Pussy Riot ever did.

Sergei Chapnin, the editor of the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate makes this point on Facebook, when he says:

Today I listened for an hour and a half as Judge Syrova read out the verdict. I’m ashamed of how she talks about our church. It is a lie, this is some monstrous provocation. No, our church is not like that. And churches are not (from Google translate, edited).

It was bad enough that the prosecution should try to do this in the name of the Church. That the judge should endorse this is far worse.

The name of the prosecution is Uzzah (II Samuel [Kings] 6:6-7):

And when they came to Nachon’s threshingfloor, Uzzah put forth his hand to the ark of God, and took hold of it; for the oxen shook it. And the anger of the LORD was kindled against Uzzah; and God smote him there for his error; and there he died by the ark of God.

Uzzah behaved as if our poor little God needed us to prop him up, as did the prosecution in the Pussy Riot trial. And thus the prosecution and the judge insulted God, just as Uzzah did. The trial itself, and its verdict, was, as Sergei Chapnin says, a “monstrous provocation” — just like Uzzah’s.

It reminded me of something that happened fifty years ago, in Johannesburg.

A Jewish artist, Harold Rubin, put on an exhibition of his pictures at the Studio 101 gallery in Johannesburg. He asked an Anglican monk, Brother Roger of the Community of the Resurrection, to open the exhibition, which he did, on 23 July 1962. Brother Roger, when he opened it, said that this was not “facile puerility” as some people had suggested. Nor was it obscene, as others have suggested. “If the human body is obscene, then this is obscene; if protest is obscene, then this is obscene.” He said that the pictures of Christ were truly Christian because they showed the meaning of the crucifixion. Also he said that only three pictures in the exhibition were suitable if you wanted something to hang in your lavender bedroom, but if you want a picture worth keeping, “for goodness sake, buy something.”

I went along to the opening with some friends, and we distributed tracts on Christian art, actually a paper read by the Revd John Davies at a conference of Anglican students.

Two of the pictures showed the crucifixion of Christ, with the title “My Jesus” and there was a series called “The beast and the burden”. One crucifixion showed God’s fool, with a clown hat, and it showed the real horror of crucifixion, the agony of it. Brother Roger likened it to the Isenheim altarpiece of Gruenewald (referred to by John Davies in his paper on Christian art) where the Christ is obviously a human in extreme agony, and the whole being of St John is concentrated in one extended finger, held rigid in a reverse curve, pointing at the crucified, as if to say, “That is the Son of God — believe it if you dare!”

A few days after the opening, the police came along and confiscated the pictures of the crucifixion, and charged Harold Rubin with blasphemy. The case came to trial the following January. Brother Roger, who had opened the exhibition, was called to give evidence at the trial, and the police stopped the train to Durban and hauled him off it to bring him back. A Dutch Reformed Dominee from Malvern gave evidence, saying the picture filled him with a sense of revulsion and shock. He said he did not like the “cap” on Christ’s head, and the defence attorney read the account of the crucifixion from the gospels to show that Christ was wearing a crown of thorns. The magistrate ruled that the dominee

was not an expert witness, as the prosecution claimed, and ruled his evidence inadmissable. A policeman who gave evidence had not heard of many famous artists, and the defence attorney, cross-examining him, said, “So as far as you are concerned Da Vinci could have been an illegal immigrant?”

Eventually Brother Roger got on the train again and went to Durban, from which he was to get on a ship to go back to England, to the Community of the Resurrection’s mother house in Mirfield, Yorkshire. We were on holiday there, and met him for a farewell lunch. On the way into town he told us about Harold Rubin’s trial, and how he gave evidence. He said that the prosecutor kept making a fool of himself, and asked stupid questions. He had asked Brother Roger if Harold Rubin was a friend of his, and he said “Yes.” “Is he a good friend?” “Yes.” “How long have you known him?” “About a year.” “How can you be a friend of an enemy of God?” “I don’t think I know the mind of God so will not be able to say who is his enemy and who is his friend. How is he an enemy of God?” “He’s a Jew.” And that, says Roger, is what it is all about – anti-Semitic.

Then the prosecutor also asked him how he could claim to be an art critic, and who he had painted with, so he named Pierneef, Preller and a couple of other well-known South Africans, and the prosecutor sat down with a bump. During the cross-examination Dr Lowen (for the defence) asked if in his opinion our Lord was clothed for the crucifixion, and the prosecutor objected to the question, saying that Roger wasn’t an expert witness, so Roger asked, “Well who is then? Nobody living has seen a Roman crucifixion.”

Unlike Pussy Riot, Harold Rubin was acquitted on the blasphemy charge, but the parallels between the two trials are interesting. It was John Davies (who wrote the paper on Christian art) who remarked, of the Harold Rubin trial, that the name of the prosecution is Uzzah. In both cases the State was ostensibly acting to protect the good name of God and the church, and in both cases the State did far more to damage the good name of God and the church than those they were prosecuting had ever done.

And, as Sergei Chapnin points out, in the Liturgy of St Basil we pray, “Remember, O God, those who are in courts, in mines, in exile and in harsh labour, and those in any kind of affliction, necessity or distress.”

_________

See also:

Orthodoxy and culture

Pussy Riot: acultural revolution?

Pussy Riot – crossed wires

August 16, 2012

Orthodoxy and culture

“Orthodoxy and culture” is a huge topic, and it is impossible to do justice to it in a single blog post. That’s why it is a good topic for a synchroblog, in which it can be examined from different viewpoints. But even of fifty or a hundred people blog on it simultaneously, I doubt that we will have exhausted the topic.

“Culture” is usually defined by sociologists as ways of behaving and thinking that are learnt from other people, rather than being passed on by genetic inheritance. In that sense it is closely related to tradition, which is the transmission of values and patterns of behavious from one generation to the next. Though it is interesting how blurred that distinction can get in modern culture. People speake about organisations having DNA, when what they actually mean is corporate culture.

And like other human organisations, the Orthodox Church has a corporate culture that some may have have described (inaccurately) as DNA. Or, to be more accurate, the Orthodox Church has several different cultures, as it has inculturated itself into different human societies, and some traditions vary from place to place, but there is also a core culture, which we call Holy Tradition (with a capital T). But even Holy Tradition is not DNA, though the analogy comes a bit closer, because Holy Tradition is that part of Orthodox culture without which the Church would not be the Church. But unlike DNA, it is not passed on automatically and biologically. It is passed on by teaching, as St Paul notes (2 Tim 2:2), which is the essence of tradition. If Orthodoxy were in the DNA of the Church, then there would be no need to baptise the children of Orthodox parents, because they would have inherited it in the same way as they inherit hair and eye and skin colour. But as it is, the children of Orthodox parents are baptised (with four exorcisms beforehand) in the same way as those whose parents were not Orthodox, and are the first in their family to become Orthodox Christians.

But the Church lives in the world, and the world has its own culture, and when we speak of “Orthodoxy and culture” we are usually thinking of how Orthodox culture relates to the world’s cultures. This is a topic that has interested missionaries and missiologists a great deal. How does Christian culture relate to secular culture?

Lots of books have been written about that topic, and it would be impossible even to try to summarise then here. What I will try to do is to give a few exanples that may illustrate a few aspects of the theme of Orthodoxy and culture.

In the book Orthodox Alaska: A Theology of Mission by Michael Oleksa we can see something of the encounter of the Orthodox Church with people of a different culture. Orthodox mission in Alaska came at a time when Western Christian mission tended to be culturally pushy, and western missionaries often engaged in social engineering, setting out to make other cultures conform to Western norms. In Alaska this is particularly noticable, as Western missionaries followed Orthodox ones, and the contrast in their methods was easily seen. In his book Fr Michael Oleksa explores some of the theological and missiological reasons for the difference, but it is interesting that even secular social scientists — sociologists and anthropologists — have observed the difference and remarked on it.

In the book Orthodox Alaska: A Theology of Mission by Michael Oleksa we can see something of the encounter of the Orthodox Church with people of a different culture. Orthodox mission in Alaska came at a time when Western Christian mission tended to be culturally pushy, and western missionaries often engaged in social engineering, setting out to make other cultures conform to Western norms. In Alaska this is particularly noticable, as Western missionaries followed Orthodox ones, and the contrast in their methods was easily seen. In his book Fr Michael Oleksa explores some of the theological and missiological reasons for the difference, but it is interesting that even secular social scientists — sociologists and anthropologists — have observed the difference and remarked on it.

The missiological point here is that Alaskan culture became Orthodox, and though in some ways Orthodoxy transformed Alaskan culture, it did not conquer it.

Something similar happeend in Russia, though it took many years, centuries even, from the first missionaries to the appearance of a culture that could be said to be Orthodox. The transformation was not complete, yet there was a sense in which people could speak of Holy Russia. The Emperor Peter the Great did not much like this, and sought to replace Russian Orthodox culture with Western modernity, a process that the Bolsheviks tried diligently and energetically to complete, often with the use of force. For much of the 20th century there were culture wars in Russia between Orthodox culture and Bolshevik culture. But Orthodoxy had become so embedded in Russian culture that the Bolsheviks could not eradicate it without destroying Russian culture.

In 1995 I visited Russia to do research from my doctoral thesis on Orthodox mission methods, and spoke to a Russian missiologist, Andrei Borisovich Efimov. He said that the task of re-evangelising post-Bolshevik Russia would best be accomplished by the main thing that had overthrown Bolshevism, namely Russian Orthodox culture.

I was not so sure.

In the Boshevik period there had seemed to be a binary choice: Bolshevism or Orthodoxy. In the late Bolshevik period many people, despairing of the spiritual bankruptcy of Bolshevism, came to Orthodoxy. But I wasn’t sure if it would work in the post-Bolshevik era. I had passsed bookstalls outside the Metro stations in Moscow, and most of them were selling Russian translations of the works of authors like the American novelist Stephen King. The post-Bolshevik Russia was rapidly becoming multicultural, and reevangelising Russia was going to require a multicultural approach.

One of the cultures that needs to be approached is the punk-rock youth culture I mentioned in an earlier post — Pussy Riot: a cultural revolution? A Punk group, calling themselves Pussy Riot, put on an univited performance in the main cathedral in Moscow, after whicvh they were arrested and charged with disorderly conduct, or hooliganism, depending on which media reports you read. I have a certain fellow-feeling for the members of Pussy Riot, who were also accused of blasphemy.

Back on 9 June 1969 the Natal Mercury carried a banner headline on the front page: ‘Church profaned,’ says Bishop. The bishop was the Anglican bishop of Natal, the Right Reverend Thomas George Vernon Inman, and the one responsible for the profaning of the church, according to him, was me. If you’re interested in knowing what provoked the bishop’s remark, you can read more about it here: Notes from underground: Psychedelic Christian Worship — thecages.

In the Pussy Riot case the dialogue, if it was a dialogue, was initiated by the punk rockers. They had performed in at least one other church before, so they obviously had something they wanted to say to the church. I would be interested to know what the response of the church was, though such things are not usually reported in the media. The Patriarch of Moscow has promised to make an official statement after the court case is over, but that is not the kind of dialogue I am thinking of. Have any priests, or other Orthodox Christians, visited them in prison? Has anyone from the church talked to them, rather than talking to the media about them? Maybe they won’t want to listen. Maybe they do not want a dialogue at all, but rather a monologue, in which they do all the talking and the church does all the listening. But one doesn’t know that until one tries.

The members of Pussy Riot have been facing the court, but there is also a sense in which the Church itself is on trial, and the followers of the punk rock culture will be giving their verdict. And it’s not as if it has never been done before — see here, for example: Punks to Monks: Eastern Orthodoxy’ s Curious Allure — Mind and Body — Utne Reader

My parish priest and colleague, Fr Athanasius Akunda, recently wrote his doctoral thesis on “Orthodox dialogue with Bunyore culture”. The Banyore are the people of his home district in western Kenya, and their encounter with Orthodoxy has taken the form of a dialogue, as it did in Alaska.

We live in increasingly multicultural world, in which different cultures, which might never have encountered each other in the past, meet each other.

Orthodox culture is a kind of dual culture. Since the church is made up of human beings, the Orthodox Church has a human culture, but it also has a culture that emanates from God. In this the Church reflects the incarnation of its Lord, who had a divine and human nature. The human culture comes from the people among whom the church finds itself, and human cultures, like human nature, are fallen cultures, and have fallen away from God. But they do not need to be destroyed and replaced by some heavenly culture. Rather they need to be restored and transformed. It is the mandate for this that Father Michael Oleksa finds in the theology of St Maximus the Confessor.

Because the world’s cultures are fallen, there is always a sense in which Orthodoxy is countercultural. But there is also the hope of restoration and transformation. Sometimes it is difficult to see how this can be done, as in the example of the Izikhothane, which I wrote about in another of the lead-up posts for this synchroblog: Izikhothane — a new word for an old fashion. The behaviour of the Izikhothane is like a religious ritual, a ritual of sacrifice to Mammon. In rural areas people might offer a bull or a sheep or a goat from their herds as a holocaust, a whole burnt offering. Trampling on a bucket of Kentucky fried chicken is an urban version of the same ritual. Love of riches is far from Orthodoxy, and yet the sacrifices of the Izikhothane show that they despise and are somehow above the riches of this world. Is it all that big a step from that to rejecting the riches of this world to show that they have treasure in heaven?

____________

This blog post is part of a synchroblog (synchronised blog) on “Orthodoxy and culture”. A synchroblog is when different people blog on the same general topic on the same day, and then post a list of links to each other’s posts, so you can surf from one to the other, and see the topic from several different points of view.

Here are links to other posts on the topic, and more will be added as other synchrobloggers post their contributions:

Dn Stephen Hayes (Orthodox Christian) of Khanya on Orthodoxy and culture

Jonathan Kotinek (Orthodox Christian) of Fixing a Hole on Orthodox Synchroblog – Orthodoxy and Culture

August 13, 2012

Izikhothane: a new word for an old fashion?

The youth of today are going to the dogs. If they aren’t murdering people for their cell phones, they’re committing suicide over a pair of shoes. Izikothane – fashion suicide | The New Age Online:

A school boy who could not get his dad to pay for a pair of fashionable Carvela shoes killed himself in protest.

Fourteen-year-old Kamohelo Tsimane, a Grade 9 pupil at Tlhatlhogang Primary School in Soweto, took his life after a failed shopping spree with his dad.

The boy had desparately wanted the brand-name shoes, which cost at least R1200, so that he could fit in with his township mates.

Things weren’t like that when we were young, old fogeys like me are expected to say. So we can’t be expected to understand the youth culture of today. And I know I’ve written about this before – here Popular culture, celebs and values, and here The youth of today, and yesterday, so I’ll try not to be too boring and repetitive.

Perhaps Kamohelo Tsimane was driven to suicide by the behaviour of other young people like these – Izikhothane | Burn Swag Burn | Mahala:

They bill themselves as street performers, but their art consists of little more than branded clothing and face-offs with rival crews who compete over who has more money. The trend called “ukukhothana”, loosely translated as dissing, is a money-conscious South African version of the USA’s diss battles, but where the American jokes would begin with: “Yo mama is so…” these kids start theirs with: “I’m so rich I can…” And then proceed to demonstrate how much money they have by engaging in wasteful behavior. Starting in the smaller black communities of Gauteng’s East Rand, the phenomenon quickly filtered into Soweto. In a recent incident, a boy from Pimville bought a bucket of KFC chicken, threw it on the floor and then stomped on the chicken pieces, using his R2000 pair of loafers to grind the white meat into the ground before setting the food alight – and then the shoes.

There seems to be some disagreement about whether those who indulge in this kind of behaviour are called “izikothane” or “izikhothane” – the latter spelling seems to be slightly more popular, but, as the writer of that article goes on to point out, while the name may be new, the phenomenon is not.

In the 1950s, a similar trend arose amongst migrant workers and mine labourers who were subject to the cramped and confined conditions of hostel living. Men, separated from their families and forced into a perfunctory sense of congeniality, would hold contests in which they would trade their grimy overalls for the finest suits and flashy two-toned brogues. Called oSwenka, the winner would receive a goat or blankets and maybe some extra money to send home to their families in the Bantustans. For the izikhothane, there is no tangible prize; but the admiring glances from girls in the crowd seems to be sufficient reward.

Phenomena like the izikhothane are sometimes mistaken for youth culture, but they are not. It’s the youth apeing the culture of the bankers and others who plunged the world into recession in 2007-2008.

In my youth earnest middle-aged women sometimes used to ask me what was the difference between ducktails and beatniks. Ducktails were (white) youths who wore fashionable clothes and went around gate-crashing respectable suburban teenage parties in the white middle-class suburbs of Johannesburg. The middle-class teenagers feared and sometimes secretly envied them. There was a similar phenomenon in Britain, where they were called teddy boys, who later divided into mods and rockers. They battled each other at seaside resorts and terrorised the respectable inhabitants.

Beatniks were somewhat different. Actually the beatniks weren’t the real thing, they were the sputniks, the fellow travellers, the groupies and hangers on, in orbit around the beats. But the middle-aged ladies who asked the questions didn’t know that either. But let’s use their terminology for now.

The main difference between ducktails and beatniks was that the ducktails accepted the values of mainstream society, and though they were regarded as antisocial, their main gripe against society was that they weren’t getting the rewards and good things that society and its advertising industry held out to them. Their attitude was “we want it all, and we want it now.”

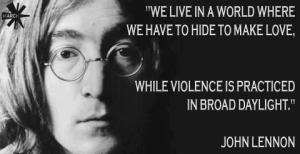

The attitude of the beats was somewhat different. It was “we don’t want any of it. You can keep it.” The successors to the beats were the hippies, who popularised the slogan “Make love, not war”.

The attitude of the beats was somewhat different. It was “we don’t want any of it. You can keep it.” The successors to the beats were the hippies, who popularised the slogan “Make love, not war”.

Go back about 800 years to Francis of Assissi, whose father had made his fortune in the fashion industry. There is a memorable scene in the film based on his life, Brother Sun, Sister Moon, in which he tosses all the bales of cloth out of his father’s warehouse, and dresses poorly, and goes out to rebuild an abandoned church, and build a community of beggars for Christ. His parents think he has gone mad, and want him to consult a psychotherapist of those days.

The beats, and beatniks, somehow never spawned a fashion industry of their own. The hippies did, however, at least for a while. You could buy a hippie outfit, for a price, and become a weekend hippie, a plastic hippie.

Beats and hippies were called countercultural, because they rejected the values of mainstream culture, which Christians call “the world”. And Christians like Francis of Assisi rejected the world’s values, and was perhaps mindful of St Paul’s advice, “Do not be conformed to this world” (Romans 12:2), and so they became countercultural non-conformists. (Reminder to Orthodox Christian bloggers: on Friday 17 August we are having a synchroblog on “Orthodoxy and culture” – to what extent is Christianity countercultueral, and to what extent is it tied to mainstream culture?)

The izikhothane are not really countercultural. They are part of the 99%, but they have adopted the values of the 1%. “We want it all, and we want it now.” And those are the values of many of the movers and shakers of our society. What price the Freedom Charter now?

There was this song from my youth, oh, about 45 years ago, that says it all…

kinks

They seek him here, they seek him there,

His clothes are loud, but never square.

It will make or break him so he’s got to buy the best,

‘Cause he’s a dedicated follower of fashion.

And when he does his little rounds,

‘Round the boutiques of London Town,

Eagerly pursuing all the latest fads and trends,

‘Cause he’s a dedicated follower of fashion.

Oh yes he is (oh yes he is), oh yes he is (oh yes he is).

He thinks he is a flower to be looked at,

And when he pulls his frilly nylon panties right up tight,

He feels a dedicated follower of fashion.

Oh yes he is (oh yes he is), oh yes he is (oh yes he is).

There’s one thing that he loves and that is flattery.

One week he’s in polka-dots, the next week he is in stripes.

‘Cause he’s a dedicated follower of fashion.

They seek him here, they seek him there,

In Regent Street and Leicester Square.

Everywhere the Carnabetian army marches on,

Each one an dedicated follower of fashion.

Oh yes he is (oh yes he is), oh yes he is (oh yes he is).

His world is built ’round discoteques and parties.

This pleasure-seeking individual always looks his best

‘Cause he’s a dedicated follower of fashion.

Oh yes he is (oh yes he is), oh yes he is (oh yes he is).

He flits from shop to shop just like a butterfly.

In matters of the cloth he is as fickle as can be,

‘Cause he’s a dedicated follower of fashion.

He’s a dedicated follower of fashion.

He’s a dedicated follower of fashion.

August 9, 2012

Pussy Riot: a cultural revolution?

On February 21, five girls wearing brightly colored balaclavas stormed into Moscow’s Christ the Saviour Cathedral to perform an anti-Putin protest song entitled, “Holy Sh*t.”

Group members Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Maria Alyokhina, and Yekaterina Samutsevich were arrested and remained in pretrial detention until their trial for an incident that some have lauded as a valid exercise of free speech, and that others have lambasted as blasphemous. If convicted they could face up to seven years in prison.

Group members Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, Maria Alyokhina, and Yekaterina Samutsevich were arrested and remained in pretrial detention until their trial for an incident that some have lauded as a valid exercise of free speech, and that others have lambasted as blasphemous. If convicted they could face up to seven years in prison.

The media reports of the actual charges are unclear, and they have been variously described as “hooliganism”, “public disorder” and “blasphemy”. The media reports of the actual event are unclear too. Some say that they burst into the “altar”, but video footage of the event shows them performing in front of the ikonostasis. None of the reports I have seen make it clear whether or not they interrupted a church service with their performance.

But one thing is is clear from the media reports: that people are looking at this event through very different cultural spectacles, and they are seeing very different things. For example, there is this Pussy Riot are a reminder that revolution always begins in culture | Suzanne Moore | Comment is free | The Guardian:

Some people have their eyes on the prize. A prize beyond medals. That prize is freedom, freedom of expression, freedom to protest. I am talking about Pussy Riot, who are drawing the eyes of the world to what is happening in Russia. Pussy Riot – crazy punks, yeah? No, they are not crazy, daft or naive. They are being tried for blasphemy in what is still, nominally, a secular state. They are highlighting what happens to any opposition to president Vladimir Putin and, indeed, they do look fabulous. If you want to see protest as art or the art of protest, look at these women and their supporters.

Described as punk inheritors of the Riot Grrrl mantle, they are so much more. They are now on trial in Moscow for a crime that took 51 seconds to commit. Please watch it on YouTube. They mimed an anti-Putin song in the main Orthodox cathedral wearing their trademark balaclavas and clashing colours. For this “hooliganism ” and “religious hatred”, the three women have already served five months in jail. They now face a possible seven-year sentence, in a country where fewer than 1% of cases that go to trial end in a not guilty verdict.

That article is worth reading, whether you agree with it or not.

It represents one strand of Western culture that is fairly vocal.

Another strand of Western culture, which is also fairly vocal, puts it like this: Western media concealing facts about female rock band’s desecration of Russian cathedral | LifeSiteNews.com:

Western media accounts typically quote only one phrase from the song sung by the trio, “St. Mary, virgin, drive away Putin,” giving the impression that the song was nothing more than an outcry against the Russian leader. However, an English translation of the full lyrics obtained by LifeSiteNews.com indicate that the girls had more than just electoral politics in mind.

In addition to their mockery of Orthodox worship, the girls derided the “Black robe, golden epaulettes,” of Orthodox clergy, and mocked the “crawling and bowing” of the parishioners. They then added a barb against the Orthodox Church’s defense of public morality, stating, “The ghost of freedom is in heaven, Gay pride sent to Siberia in chains.”

“The head of the KGB is their chief saint,” continue the girls, in reference to Putin’s former position under the Soviet regime.

They then sing a stanza associating the sacred with feces, followed by another stanza objecting to perceived support of the Putin administration by leaders of Orthodoxy, then another stating “Patriarch Gundyaev believes in Putin,” adding “B**ch, you better believe in God.”

But Russian cultural spectacles are also very different, and confusing. Some Russian commedntators do seem to think that freedom of speech is a bad thing. This one, for example: Интерфакс-Религия: Вопрос не в жесткости наказания участниц “Pussy Riot”, а в его неотвратимости. He seems to be saying that their act wasn’t bad because it was in a church, but because the church was a public place. This implies that he would think it equally bad if it were in a theatre, a street or a park, and not in a church.

But Russian cultural spectacles are also very different, and confusing. Some Russian commedntators do seem to think that freedom of speech is a bad thing. This one, for example: Интерфакс-Религия: Вопрос не в жесткости наказания участниц “Pussy Riot”, а в его неотвратимости. He seems to be saying that their act wasn’t bad because it was in a church, but because the church was a public place. This implies that he would think it equally bad if it were in a theatre, a street or a park, and not in a church.

We are told elsewhere that “Prosecutors have maintained that the Pussy Riot members “inflicted substantial damage to the sacred values of the Christian ministry…infringed upon the sacramental mystery of the Church… [and] humiliated in a blasphemous way the age-old foundations of the Russian Orthodox Church.” And that implies that it would have beemn OK if it were performed in a public place other than a church.

The Western pop star Madonna came out in support of the jailed Pussy Riot members at a concert in Russia Pussy Riot case: Madonna labelled moralising ‘slut’ | Music | guardian.co.uk:

Madonna is the highest-profile star to come out in support of the group. Artist Yoko Ono issued a statement calling for their freedom earlier this week.

The tens of thousands of fans inside Olimpisky Stadium greeted Madonna’s gesture with wild applause.

So in Russia itself there are wildly divergent cultural perceptions.

Some Western groups, however, are also propagating outright lies and disinformation about the event. One of these is Amnesty International, a formerly-respected organisation that stood up for the rights of prisoners of conscience. I’ve pointed out some of their falsehoods in another blog post here, which also gives the English translation of what Pussy Riot sang in the cathedral.

But the cultural and political implications of what is on the Amnesty International site are even worse.

An Amnesty International petition site (Take Action Now – Amnesty International USA) urges people to send an e-mail with the following text to the Russian prosecuting authorities:

I respectfully urge you to drop the charges of hooliganism and immediately and unconditionally release Maria Alekhina, Ekaterina Samutsevich and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova. Furthermore, I call on you to immediately and impartially investigate threats received by the family members and lawyers of the three women and, if necessary, ensure their protection. Whether or not the women were involved in the performance in the cathedral, freedom of expression is a human right under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and no one should be jailed for the peaceful exercise of this right. Thank you for your attention to this serious matter.

Now imagine, for a moment, that the boot was on the other foot.

Imagine that it was a Western European country, and that the act of “hooliganism” concerned was daubing swastikas on a synagogue. If that were the case, would Amnesty International be urging its members and the general public to send messages saying

Whether or not the women were involved in writing the graffiti on the synagogue, freedom of expression is a human right under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and no one should be jailed for the peaceful exercise of this right. Thank you for your attention to this serious matter.

I think that in Western Europe such a petition would be widely regarded as “hate speech”, and “anti-Semitic”, as would the graffiti. So why does Amnesty International think that it is OK to encourage people to send such things to Russia?

And then, of course, one can put the boot back on the first foot again. If these same three young women had daubed graffiti on a synagogue in Moscow, would they have been prosecuted for the same offence and in the same way as they have been in this case?

So there are differences between Russian culture and Western culture, and differences within Russian and Western culture. There seems to be a huge gap in understanding these differences. But these differing views also have something in common: they share in the failure to understand cultural differences, and they share in the readiness to condemn those whose culture they do not understand.

But what about Orthodoxy?

Is there an Orthodox culture, and does it have anything to say about this?

Yes, I believe there is an Orthodox culture, and it is well expressed in one of the hymns we sing repeatedly in the Paschal season.

Let God arise, let his enemies be scattered

Let those who hate him flee from before his face.

Does that apply to Pussy Riot?

Yes, I believe it does.

But you have to come to the end of the hymn to see how it applies.

This is the day of resurrection.

Let us be illumined by the feast.

Let us embrace each other.

Let us call “Brothers” even those that hate us, and forgive all by the resurrection, and so let us cry:

Christ is risen from the dead

Trampling down death by death

And upon those in the tombs bestowing life.

So what do we call the members of Pussy Riot?

Sisters.

And what do we do with them?

Embrace them, forgive them by the resurrection

and tell them that God loves them and we love them too.

That’s Orthodox culture.

_________________

Postcript:

The events described in this post highlight some of the different cultural views and perceptions there are in the world, and how little they are willing to even try to understand one another. One of the important questions it raises for Orthodox Christians is how Orthodoxy relates to culture. In the blog post above I’ve barely scratched rthe surface, and rather just pointed out a few examples.

To help us go deeper into the question, some of us have agreed to take part in a synchroblog on the theme of Orthodoxy and culture. That means that we will try to blog on the same topic on the same day — Friday 17 August 2012.

If you are an Orthodox blogger, and are reading this, we invite you to join in by writing a post in your blog on that day, and posting links to the other blogs that are participating. For more information on how to do this, see the Orthobloggers page on Facebook, or the Orthodox Synchrobloggers Mailing list.

August 7, 2012

Remember the Butovo massacres, 75 years ago

Seventy-five years ago, on 8 August 1937, ninety-one people were shot at Butovo, just outside Moscow, a firing range belonging to the NKVD, the Russian Security police.

But that was only the start.

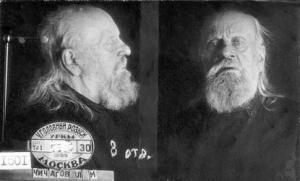

Metropolitan Seraphim (Chichagov) who died at Butovo – from the secret police files

The shooting continued day after day,, with increasing numbers killed daily. On 8 December 1937, four months after the killing began, 474 people were shot. And it went on until altogether something like 20000 people were killed on Stalin’s orders.

Who were these people?

They were “anti-Soviet elements”, which included political opponents of Stalin’s regime, former officials of the Tsarist regime, and also what were described as “sectarian activists, churchmen”, which included clergy, monastics and lay leaders of the church.

According to this site Synaxis of the New Martyrs of Butovo : A Russian Orthodox Church Website:

By now it is known that the former special zone of the NKVD-KGB in Butovo is the largest mass grave of victims of political repression in the Moscow area. Among those executed were a great many clergy, including six bishops, as well as monastics and simple believers, laypeople who assisted in churches. Over several years, by decrees of the Council and Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church, 230 of them were glorified among the saints.

The peak of executions came during the “Yezhov era.” [5] In one year, from July 1937 to August 1938, there were 20,765 executions on the firing range. Of them, approximately 1,000 (based on investigative materials) suffered specifically for their fidelity to the Church and to faith.

Chapel at the Butovo killing fields

I first learned about Butovo when I visited Russia in 1995 to do research for my doctoral thesis, and at St Tikhon’s Institute a couple of researchers were compiling a computer database of the new martyrs, and at that stage they had about 800 recorded. They scanned in photos from the KGB archives, and also asked relatives to let them have photos to scan.

Synaxis of the New Martyrs of Butovo : A Russian Orthodox Church Website:

The church itself is a symbol, small and wooden, erected right here on the shooting range, on the site of the forge where it is believed the first executions took place. It is remarkably light and warm inside. It is prayed in, especially on the day commemorating the saints of Butovo. It feels as though they are all here, next to us, with the small church holding everyone.

On the iconostas is a row of icons depicting the martyrs of Butovo. Among them are Archbishop Dmitri (Dobroserdov) of Mozhaisk, Archbishop Nicholas (Dobronravov) of Vladimir and Suzdal, Bishop Arkady (Ostalsky) of Bezhetsky, Bishop Jonah (Lazarev) of Velizh, and Bishop Nikita (Delektorsky) of Nizhniy Tagil. Here they all are: archimandrites, abbots, archpriests, priests, and parishioners.

I sometimes think of how casual some people are when they ask for baptism foir themselves or for their children. Do we realise that we are signing ourselves up for this?

And I recall the words of a Western hymn that we used to sing so unthinkingly on the Western All Saints’ day and Hallowe’en.

They have come from tribulation

And have washed their robes in blood

Washed them in the blood of Jesus

Tried they were and firm they stood

Mocked, imprisoned, stoned, tormented

Torn asunder, slain with sword

They have conquered death and Satan

Through the might of Christ the Lord.

So take a pause in your busy day to remember the martyrs of Butovo, and other martyrs of the 20th century.

You can read more about them here:

Synaxis of the New Martyrs of Butovo : A Russian Orthodox Church Website

Former Killing Ground Becomes Shrine to Stalin’s Victims – New York Times

New Martyrs of Butovo – OrthodoxWiki

Butovo massacres – a tragedy to remember: Voice of Russia

This is my 1000th post in this blog.

August 5, 2012

American priorities: Chick-Fil-A and Faith vs Works

Blogger Clarissa cited a post of mine, in a question about the US Evangelical “Faith versus Works” thing:

“If you hang around evangelicals long enough, you’ll hear over and over again that we’re NOT saved by our works, but rather by our FAITH – and that if you even start to think your works might matter in gaining salvation, well, then you’re not saved.” I always thought that this was what Catholics believed. Now it turns out that Protestant Evangelicals have the same approach. Is there Christian denomination where works matter more? Or, at least, matter somewhat? I might consider joining up. Maybe the Orthodox Christians can clear this up for us?

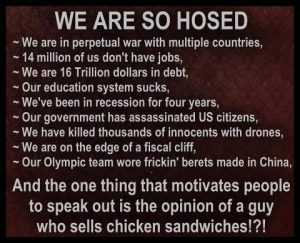

American Priorities

Well, I went to the link she gave, and found that it was all about Evangelicals and Chick-Fil-A. I had never heard of Chick-Fil-A until last week, but then, if you read blogs, or Twitter or Facebook or other online forums you wouldn’t have been able to escape it. I Googled for Chick-Fil-A, and after reading a couple of things decided that it would be a waste of time trying to find more. As I wrote in a comment on Clarissa’s blog:

While I’ve heard of the Chick-Fil-A brouhaha, I really haven’t a clue what it is all about, and I don’t think it is worth taking the trouble to find out. As one of those little poster thingies on Facebook pointed out, the USA goes around invading lots of countries, killing people with drones, and all sorts of other stuff, but none of those things get them as worked up and willing to comment as the opinion of a guy who sells chicken sandwiches. And trying to sort out the opinions of the opinions of the guy who sells chicken sandwiches seems to be a daunting task and a huge waste of time, unless you are an American, and then, no doubt, it is Really Important. But the guy who sells chicken sandwiches doesn’t sell them in this neck of the woods, so the whole thing is hugely irrelevant.

So wading through the linked post about that to find out where the faith vs works thing comes into it seemed a bit too much. I think that the general Orthodox view is that that controversy is two sides of the same Western coin, and, unless you are really keen on theological nit-picking suffice it to say that the Orthodox believe in synergy between faith and works.

I read the first couple of paragraphs of the linked blog post, and decided it would take several hours, if not days, of research to try to understand it, and that it probably wasn’t worth the effort.

So if I can’t be bothered to try to understand it, why on earth am I writing a blog post about it?

Well, it just goes to show, doesn’t it, than in spite of social media making the global village even smaller in a way that Marshall McLuhan never dreamt about, we are still divided by culture, just as much as we were when it would have taken three months to send a letter from Durban to Boston by sailing ship.

And, as I commented about that poster thingy on Facebook:

For those who may be wondering what this is about, “we” in the poster below refers to the USA, so by sharing this I am asserting my anti-American credentials — we hate them because of their freedom, doncha know, their freedom to do all those things, including their freedom to give priority to the opinions of a guy who sells chicken sandwiches. I’m not sure what his opinions are, but so many people were expressing opinions for and against his opinions that I felt compelled to Google for Chick-Fil-A. But don’t worry, Americans, we get equally obsessed with trivialities, like some guy who threw a sushi party, who filled the front pages of the Sunday newspapers, and kept the commentariat going for months.

So that’s something that’s common to most cultures. We all like to major on minors, as the Americans say.

August 4, 2012

Fault line: book review

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

A good story well told.

I suppose one could say much the same about most of Robert Goddard‘s books. He has written more than twenty novels in the same genre, and with very few exceptions each one is as good as the last. And the exceptions are generally those where Goddard breaks from the formula, which he seems to have perfected – a mystery in the past which affects characters in the present.

The story is about a family firm, Walter Wren & Co., that mines china clay in St Austell, Cornwall. It is merged with a bigger firm, and after several more mergers has become part of a large international conclomerate. The former CEO of the company, Greville Lashley, who is still the majority shareholder, commissions a historian to write the history of the company, but she finds that several crucial files are missing, and Jonathan Kellaway, who had worked at Wren’s as a student, before it was absorbed, is asked to help locate the missing files.

Back in the 1960s, when Jonathan was a student doing a vac job, he had become friendly with two of the children of the Wren family, Oliver and Vivien Foster, and Oliver is convinced that there was a mystery hidden in the company records, a mystery that had led to his father’s death. Oliver got Jonathan to help him with some of his investigations, but never revealed exactly what he was looking for, and now, more than forty years later, Jonathan is asked to find the missing files, which may solve Oliver’s mystery, and others that have plagued the Wren family ever since.

I found the story particularly interesting because I had just finished reading another book of the same genre, The Absolutist by John Boyne which was almost painfully badly written, with glaring anachonisms on every other page (see my review here). As a result, I think I read Fault Line rather more critically than usual, and enjoyed the contrast: it was as well written as the other was badly written. I was on the lookout for anachronisms, more than usual, and spotted only possible one — that there was no Metro Station at the Spanish Steps in Rome in 1969. According to Wikipedia, that station only opened in 1980. Perhaps if I were a publisher’s fiction editor, I might have spotted more errors, but if there were others, I didn’t notice them. The anachronisms in The Absolutist didn’t just stick out like sore thumbs, they stuck out like undressed amputated limb stumps.

When Robart Goddard describes the 1960s, it feels authentic. OK, he no doubt lived through the period, as did I, so he would have a better feeling for it than John Boyne would have for the period of the First World War, but still… Reading some of the scenes in Fault Line brought snatches of songs from the sixties to mind:

… making love in the afternoon

with Cecelia up in my bedroom[1]

and

We passed that summer lost in love beneath the lemon tree

the music of her laughter hid my father’s words from me

Lemon tree very pretty

and the lemon flower is sweet

but the fruit of the poor lemon

is impossible to eat[2]

Another thing that made the book interesting to me is that I am interested in family history, and this is something of a family saga, a telling of the story of the family by someone outside, who knew nevertheless knew some members of the family well. Also, one branch of my own family came from Cornwall, and some of them were china clay labourers in and around St Austell in the 1870s and 1880s, so the descriptions of the china clar mining industry and its place in the town are quite interesting too.

___

Notes

[1] “Cecelia”, sung by Simon & Garfunkel

[2] “Lemon tree”, sung by Peter, Paul & Mary

August 2, 2012

The long road home: book review

The Long Road Home: The Aftermath of the Second World War by Ben Shephard

The Long Road Home: The Aftermath of the Second World War by Ben Shephard

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Occasionally one comes across a book that explains some things that one has always wondered about, and this is one of them. I’ve read several histories overing the period of the Second World War, and even did a History Honours paper on modern Germany, which covered that period. but there were some things that I never understood, and this book has helped to explain some of them.

The things that I find most interesting in history are transitions: from peace to war, or from war to peace; transitions such as revolutions, and other things that make big changes in people’s lives. And I want to know how these changes affected people. This book deals with one such period: the end of the Second World War in Europe.

I knew, from reading other history books, that one of the problems facing the victorious Allies after the surrender of Nazi Germany was that of Displaced Persons, or DPs as they were known. But it was never really clear who these people were, or what were the problems they posed. Why couldn’t they just go home once the fighting was over?

It was not until I read this book that I realised that there was a difference between DPs and refugees, and just what constituted the problem. I thought that Displaced Persons included anyone who was left far from home when the fighting ended, including refugees, prisoners of war, and people who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time when the war started, like “enemy aliens”.

But it appears that in the minds of the Allied administrators DPs were a particular class of persons, people who were brought to Germany during the war, voluntarily or forcibly, as labourers.

As the war expanded, with the successive German invasions of Poland, Norway, the Low Countries, France, the Balkans and the USSR, so more and more Germans were conscripted for miliary service, leaving labour shortages in the farms and factories in Germany. To alleviate this shortage, the Nazi government recruited or conscripted labourers from the occupied territories to keep production going. Apart from a few volunteers from places like France, most were in fact slave labourers.

In an ideal world, once the war ended the demobilised soldiers would go back to their old jobs and the labourers would go home. But the old jobs were sometimes no longer there, because the factories had been bombed, and the transport infrastructure likewise. Also, once the war ended the last thing most of the forced labourers wanted to do was to continue working for the Germans.

The Allies had foreseen some of this, and had set up the United Nations Rehabilitation and Relief Administration (UNRRA) to deal with it once the war ended, but bureaucratic bungling and ineffective leadership meant that took a long time to work effectively. UNRRA was also dependent on the miliary authorities in the four different occupation zones for such things as transport, and the miliary authorities had other priorities, so urgently needed food and medical supplies often took a long time to arrive.

Camps were set up for DPs, to provide food and shelter until they could be sent home, but they were of many different nationalities, and some of the more nationalistically-minded of them demanded to be housed in separate camps, and nationalities were disputed. For example, at the end of the war, Poland had moved westwards, and DPs who had been born in Poland before the war found that their homes were now part of the USSR, and the USSR claimed them as its citizens, and they did not want to return home.

Jews and Ukrainians demanded to be treated as separate nationalities, and to live in separate camps, though at that time there were no separate states for those nationalities. Zionists from Palestine visited the Jewish DP camps, and persuaded most of the inmates to demand that they be “repatriated” to Palestine, something which the British, in their zone, were reluctant to encourage, because since the First World War they had governed Palestine under a League of Nations mandate, and the Arab population there were opposed to more Jewish immigration.

Many of the DPs from Eastern Europe, which was now under Soviet control, had no desire to go back home, and many wanted to go to America, which had seen hardly any fighting in its own territory during the war. Because of the westward movement of Poland, many Germans were expelled from western Poland (which before the war had been eastern Germany), and this aggravated the problems. Immediately after the end of the war there were outbreaks of diseases like typhus in the DP camps, though newly-invented drugs and insecticides, like penicillin and DDT, helped to control them.

One of the biggest problems was feeding the population of the camps, and indeed the population generally, was the problem of feeding them. One of the things that had puzzled me in the past was why in Britain, there was no bread rationing during the war, such rationing was introduced in 1946, and food rationing in Britain was more severe immediately after the war than it was during the war. This book provides an explanation of that too.

The influx of yet more refugees placed an intolerable burden on the British Zone. Only 17 per cent of those who had entered the zone by 15 June 1946 were adult males, and only 60 per cent of those were fit for work. The arrival of 750,000 economically unproductive expellees aggravated the food, housing and public health situation. In late 1948 there would be 243 people per square kilometre in the zone, compared with 167 in the American and 131 in the French; it was estimated that, if you reckoned on one person per room, the British Zone was short of 6.5 million rooms. The situation was at its worst in Schleswig-Holstein, where 120,000 people were still living in camps.

To feed the extra mouths, the British authorities made desperate efforts to raise food production and make the zone more self-supporting. They had some 650,000 acres of grassland ploughed up — top produce, it was hoped, a 10 per cent increase in the grain harvest and and a 75 per cent increase in potatoes. They tried to persuade farmers to slaughter their livestock hers, so as to provide meat and reduce the demand on arable pasture and on feedstuffs. They forbade the growing of luxury crops; cut the amount of grain allowed for brewing; encouraged the cultivation of vegetables in town gardens and allotments; did what they could to compel farmers to bring their produce to market.

But this policy was only partially successful. The farmers of northern Germany, who were by long tradition animal husbandmen and not cereal growers, resisted attempt to change their ways; there wasn’t the staff to enforce the changes. Food production was further handicapped by shortages of seed, fertilisers and equipment. British policy fell between two stools, providing neither effective coercion nor effective incentives.

It was clear that clear that considerable imports would continue to be necessary for several years. The British would have to juggle the needs of the Germans against those of their own population — whose bread was rationed in 1946 — and other regions of the world, such as India (Shephard 2011:246)

Another interesting facet of the food problem lay far from Europe, in America:

On the face of it there should not have been a food problem at all after the war. More than enough was produced in the western hemisphere — and in particular, in the United States — to feed the starving Europeans, and probably the starving Asians as well. The war years had seen a second agricultural revolution in the United States, as a severe labour shortage led to the systematic application of mechanisation and fertilisers which transformed the productivity of the land. By 1946 American agriculture was producing a third more food and fibre than before the war, and with much less labour.

However, Americans now wanted to eat more meat, and it paid their farmers to feed their cereals to the livestock needed to produce that meat, rather than to human beings. For the first time in history, high meat consumption in one major country would distort agricultural output all over the world.

However, the roots of the problem went back further than that. The people who ran US agriculture were mindful of the huge surpluses in the 1930s, when overproduction had destroyed farm prices: their main objective was to avoid any repetition of that nightmare. At the end of 1944 the United States War Food Administration had decoded from a few shreds of doubtful evidence that Europe was not going to starve when the war ended. Accordingly — and against the advice of Herbert Lehman — it took steps to avoid overproduction, by reining in farm output, relaxing rationing controls so that American civilians could eat up existing food stocks and stopping all stockpiling for relief. The object of this “bare shelves” policy, says historian Allen J. Matusow, “was to come as close as possible to see that the last GI potato, the last GI pat of butter and last GI slice of bread was eaten just as the last shot was fired”. Its potentially disastrous effects of European relief were soon apparent and by the spring of 1945 public figures such as Herbert Hoover were warning of the perils ahead. Yet it was almost a year before decisive action was taken, partly thanks to Lehman’s ineffectiveness in Washington, and partly due to the different priorities of the Truman administration, and its Secretary of Agriculture, Clinton P. Anderson, who was determined to put the interests of the American consumer before those of relief.

Which is where meat comes in. If there is a villain in this story, it is the sheer hoggery of the American military, which insisted on annually requisitioning 430 pounds of meat per soldier, thus taking up a fair amount of the available livestock and diverting grain production away from human consumption. However, in wartime meat had been rationed for the American domestic consumer; with the coming of peace, and Americans now eating considerably better than in the 1930s, there was huge pressure on Washington to remove the rationing, while the incentive to American farmers to sell their cereals for animal rather than human consumption remained strong. In November 1945, the Truman administration removed all rationing from meat, oil and fats (Shephard 2011:251).

Reading about the problems faced by UNRRA, and especially the bureaucratic bunglings described in the first few chapters of the book, also helps me to understand some of the failures of transformation in South Africa. In both cases, the planners underestimated the hugeness of the task. And as in South Africa, where so much of the money earmarked for development is siphoned off into the bottomless pit of corruption, so in post-War Europe, much disappeared in a similar fashion, and also into the black market.

What I liked about this book was that it did not just describe things in terms of bald statistics and policies and minutes of meetings, but also tells the human story of the people in the camps, and what life was like for them, and it uses not only official sources, but diaries, letters and personal accounts written by military officers, UNRRA officials, and DPs themselves. This gives a fuller and more human picture.

August 1, 2012

Anglo-Catholics and Orthodoxy

A couple of years ago I wrote a blog post called The end of an era -— Anglo-Catholicism rides off into the sunset, which has proved surprisingly popular, as it remains on the list of top-rated posts on this blog. In it, among other things, I explained why we left the Anglican Church and became Orthodox more than 25 years ago.

A fellow-blogger recently drew my attention to some research being done on Anglo-Catholics who have become Orthodox, or have even thought about doing so: The road less travelled: Anglo-Catholics who consider converting to Orthodoxy. Deacon John Saturus writes:

I am Deacon John Saturus, a deacon of the Orthodox Church, and am working on a Master’s degree in Theology. My thesis topic is “The Conversion of Anglo-Catholics to Orthodoxy”. If you have ever been an Anglo-Catholic who considered converting to the Orthodox Church(whether you became Orthodox, remained Anglican, or joined some other Church), I would very much appreciate your sharing some of your thoughts and experiences with me.

I have prepared a sort of questionnaire, which you can either fill out online, or have emailed to you. You don’t have to answer every question; if you do answer a question, you should feel free to answer as much or as little as you like. And if there’s anything I’ve forgotten to ask, where you think your thoughts or experiences might be interesting to me or helpful to my research, I’d be very glad to read and think about whatever you’d like to share.

It seems to be an interesting topic, and one that would be worth having more information on, so if you consider yourself Anglo-Catholic, and have ever thought about possibly becoming Orthodox, please take part in the survey. If you achieve nothing else, you’ll be helping Deacon John to get his degree! This is the kind of research topic where the more information is available, the more accurate the research becomes, so the more the merrier.

I’ll also, without, I hope, prejudicing the research, make a couple of observations of my own.

One of these observations is that, of all the Western Christians who might be interested in Orthodoxy, and try to learn something about it, Anglo-Catholics are among those least likely to become Orthodox.

Fr Martin SSF Fr R D E Jones SSC Fr. J Caster SSC processing the relics of SS Peter & Paul. An Anglo-Catholic procession

This might come as a surprise to some. The Orthodox are, after all, “liturgical” like the Anglo-Catholics. There is lots of incense in the services, and colourful vestments, and to a casual observer there might seem to be a very close match.

The late Fr Alexander Schmemann once wrote that at some ecuenical gathering he attended he was seated with the groups perceived as “high church” and “liturgical”, because that was the dominant Western perception of the Orthodox Church. Yet he said that he might have felt just as much at home, or more at home, among the Quakers, with whom he, as an Orthodox Christian, felt he shared an affinity.

I have had similar experiences. I have sometimes been at ecumenical gatherings, among groups of Western Christians whom I don’t know very well, and the ones I have felt most at home with, as an Orthodox Christians, have been Mennonites and Zionists.

I was once involved with a quango called SAQA (the South African Qualifications Authority), working to develop standards for theological education, and the one I felt most at home with, and whom I worked with late into the night, was a Zionist bishop. I invited him to visit our church, and one Sunday he came, with his wife, white robes and all. He felt right at home. He later told me that a couple of weeks after his visit there was a thunderstorm in the middle of the night and he was awakened by a very loud clap of thunder, and he jumped out of bed and made the sign of the cross. His wife joked that he was becoming Orthodox.

Anglo-Catholics, on the other hand, often seem to be rather uncomfortable when they come to Orthodox services. It is the awkwardness of the almost-familiar. When Zionists or Pentecostals come, they come expecting everything to be strange, and are then surprised by things that are unexpectedly familiar. The scriptural imagery in the hymns grabs them, and they find the whole thing biblical, but in unexpected ways.

An Orthodox procession: At St Thomas’s Church, Sunninghill, Johannesburg, for the feast of St Thomas, October 2010

Anglo-Catholics, on the other hand, have the reverse experience. They come expecting things to be familiar, and suddenly unexpected things happen. At a point in the service where they might expect to genuflect, the Orthodox either do nothing, or might bow down rather than bending the knee. They tend to find this unsettling, and depending on the rigidity of their Anglo-Catholicism, might find it totally off-putting. Orthodox services are not run according to Ritual Notes.

Orthodox services tend to look untidy to Anglo-Catholic eyes, especially white South African Anglo-Catholics (if there are any left). Black Anglo-Catholics might find it more familiar.

An Orthodox Christian who lived a long time in England (he was an exile from Bolshevik Russia), Dr Nicolas Zernov, once remarked, “The Anglican Churches look like fortresses, and inside also it is very military.”

In England there are many Anglican Churches with battlements around the tops of square towers, and sometimes all along the sides of the nave as well. Inside, there are sometimes miliary paraphernalia like flags, regimental standards and so on, but even more, the congregation tends to sit, stand or kneel in unison. Altar servers move in straight lines, with military precision, and the server who carries the thurible handles it like a drum major’s baton. Orthodox services, to an Anglo-Catholic eye, tend to look messy, and in need of a good sergeant-major to get them to shape up.

But that is all based on my own subjective impressions. Perhaps it’s all quite wrong. To get a true picture, lots of people need to complete the survey, so, if you are or have been an Anglo-Catholic, and have ever thought about becoming Orthodox, click here to do it now.