Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 63

December 31, 2012

What’s hot in spirituality and religion in South Africa

Those who read this blog over the last couple of weeks might have noticed the South African Annual Blog Awards vote logo in the sidebar on the right. It was an invitation to readers who liked this blog to vote for it.

Well, I don’t know how many do like this blog, and how many of those did did like it actually voted for it, but all the votes have now been tallied, and the winners and runners-up have been announced. And here are the winners and runners up in the “Religion and spirituality” category:

Well, I don’t know how many do like this blog, and how many of those did did like it actually voted for it, but all the votes have now been tallied, and the winners and runners-up have been announced. And here are the winners and runners up in the “Religion and spirituality” category:

Penton: Independent Pagan Media – Winner

Sue Levy – First Runner Up

Ask Nanima? – Second Runner Up

I think that gives a pretty good idea of the vital role played by re,ligion and spirituality in South Africa today.

In fact, one could say that it confirms the message of my recent post on Reality TV — that one can truly say of South Afrca, Your heart is full of unwashed socks, your soul is full of gunk.

Is this really where the soul of South Africa is?

Or perhaps it is just the soul of the South African blog-reading public, and the South African blog-reading public is way out of touch with South Africa as a whole.

But the South African blog-reading public has voted, and this is what turns them on spiritually. Read especially the two runners-up, and weep. Or perhaps I’m missing something. So if I am, read them again, and tell me what I’m missing.

But my son works in a Tshwane bookshop, and his observations of the taste of the South African book-buying public seems to fit pretty well with these results.

This is the soul of South Africa!

This is the best that South African religion and spirituality have to offer.

Your heart is full of unwashed socks, your soul is full of gunk.

December 30, 2012

2012 in review

The WordPress.com stats helper monkeys prepared a 2012 annual report for this blog.

Here’s an excerpt:

19,000 people fit into the new Barclays Center to see Jay-Z perform. This blog was viewed about 73,000 times in 2012. If it were a concert at the Barclays Center, it would take about 4 sold-out performances for that many people to see it.

Click here to see the complete report.

December 29, 2012

Your heart is full of unwashed socks, your soul is full of gunk

Encase your legs with nylons

Bestride your hills with pylons

O age without a soul.

So wrote John Betjeman nearly 60 years ago, and things have gone downhill ever since.

I don’t know of anyone who wears nylons any more, though there are pylons round two sides of our house (why doesn’t the lightning hit them rather than taking aim at our ADSL router?)

But to understand the soul of our age, we have to look at reality TV.

Here Comes Honey Boo Boo — reality TV?

I haven’t seen Here Comes Honey Boo Boo but that is the one that the New York Times chose to illustrate a recent article on the topic. Reality Shows Reached for Extremes in 2012 – NYTimes.com.

The first “Reality TV” show that I was aware of was Big Brother, which aired in South Africa about 11-12 years ago. It was attended by a great deal of prepublicity, and I found the whole concept rebarbative. It seemed to be based entirely on exploitation and manipulation. It was also utterly unreal — putting a bunch of people in a very artificial environment. It aired every day on TV, and was on the Web for 24 hours a day. We watched it about once a fortnight, when they voted people out of the house. The general public also got to vote, and in the end they voted for the most inpleasant character on the show, which said a great deal about the South African public and its taste. Your heart is full of unwashed socks, your soul is full of gunk.

The New York times article, Critic’s Notebook: TV — Where Too Far Is Never Far Enough, mentions a book that satirises the whole “Reality” TV trend:

“Our big dilemma going into the end of the season is whether we may actually be pushing the envelope too far,” says the protagonist of “The King of Pain,” one of 2012’s most enjoyable novels for anyone who is a fan of reality television or simply likes monitoring the continuing train wreck that its more tawdry regions have become.

The character, Rick Salter, is talking about a wildly successful reality competition show he created in which contestants undergo various kinds of torture: they’re deprived of food one week, branded the next week, and so on. The show becomes a national phenomenon, finding the perverse side of the public taste, until things spin out of control.

The article doesn’t mention that other satire on Reality TV, The Hunger Games, which extrapolates the current taste for Reality TV into the future, where too far is still not far enough. Your heart is full of unwashed socks, your soul is full of gunk.

There is another variety of Reality TV that I watch occasionally, which is (or seems to be) filmed on location, rather than having a special location set up, like the Big Brother house. Examples are Ice Road Truckers and Death Road Truckers. I watched a few of episodes of the latter, which seemed to be full of stock shots, incompetently juxtaposed. One was a shot taken from the top of the truck, looking down, showing the wheels on the edge of a sheer precipice, and then there was an establishing shot, taken from across a valley, with such a precipice nowhere in sight, and then a cab’s-eye-view, also with the precipice nowhere in sight. These were repeated in several different episodes, and after the second repetition, all sense of “reality” dissipated.

There was another one — I forget the title now — where the protagonist was parachuted alone into a wilderness and survived by eating insects and things like that. I watched a few snatches of that, but became more and more conscious of its unreality rather than reality, because I was always aware of the presence of the camera crew. The survival tips were sometimes interesting, and could have come out of a book I have somewhere called Don’t die in the bundu. The pretence that it was real somehow didn’t work.

I did once see real Reality TV, as opposed to the fake reality that I have been describing. That was the rescue of some miners in Chile who had been trapped underground a couple of years ago. Or perhaps that too was faked for TV — how would one know? Well one way of knowing is that if it was real (ie fake) Reality TV, the audience would have voted for which miners got to be rescued, and which would be left to die of starvation underground.

Am I the only one bothered by this trend?

Am I just a crusty old curmudgeon complaining about the youth of today being so much worse than our generation?

Our generation believed in things like “flower power” and had slogans like “make love not war”.

We saw things like manipulation and exploitation and the Schadenfreude that seem to motivate Reality TV audiences as somehow undesirable. But some of the “flower power” generation grew up. One of them was Bill Clinton, the bomber of Belgrade.

The same is true of every generation. Your heart is full of unwashed socks, your soul is full of gunk.

My heart is full of unwashed socks, my soul is full of gunk.

December 25, 2012

Splendour and catastrophe in the Mediterranean: book review

Levant: Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean by Philip Mansel

Levant: Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean by Philip Mansel

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This book is tale of three cities — Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut. But it is a great deal more than that, as it is also the history of the region of the world in which the three cities are located, the region known to the French as the Levant, which is equivalent of the Latin “Orient”, and means the land of the rising sun. More specifically, it refers to the lands bordering the Eastern Mediterranean which, from the 16th century to the 20th, were part of the Ottoman Empire.

The three cities that feature in the story (to which can be added a fourth, Salonica), were trading ports in this period, and were subject to a great deal of foreign influence, and in some periods the consuls of the trading nations, mainly West European, had more influence than the Ottoman government, or even its local representatives.

One result of this was that these cities became cosmopolitan, with a great variety of races, religions, languages and cultures represented in them.

Western Europeans were known as Franks, and the ones who were most active at the beginning of the period were Venetians and Genoans, and a kind of piggin Italian, known as Lingua Franca (the language of the Franks) became the de facto language of business in the Levant. In later times French and British influence overshadowed the Italian, but the concept of a Lingua Franca as a language of trade remained.

Much of the trade was in the hands of dynasties of foreign merchants, families who lived in the Levant for generations, yet never became assimilated into the local culture. In the 19th century, however, there were forces of change and modernisation. In Egypt Muhammed Ali, the Albanian-born Ottoman governor, aided by the foreign consuls in Alexandria, made Egypt virtually independent. The foreign communities had their own schools, and even universities, using their own languages rather than Arabic or Turkish.

In the 19th century there was also growing nationalism, both in the local regions becoming aware of themselves as distinct nationalitities as opposed to the Ottoman Empire, and also the powers behind the foreign communities, such as Britain and France, and later Greece.

Mansel presents the history of the Levant as a struggle between cosmopolitanism (good) and nationalism (bad). Nationalism could not tolerate cosmopolitan cities, except where nationalists perceived trade as advantageous to their cause, and in the 20th century the cosmopolitan cities were nationalised, and made homogeneous, some more violently than others. Cosmopolitan Salonica became Greek Thessaloniki. Cosmopolitan Smyrna became Turkish Izmir. Alexandria expelled the foreign communities in the 1960s (even those whose members were Egyptian-born), and Beirut was torn apart by civil war in the 1970s.

I was aware of some of these events, from reading about them in other histories, or, in the case of more recent ones, in newspapers, but Mansel manages to weave the different threads into a tapestry to create a coherent picture.

Mansel’s sympathies lie strongly with the cosmopolitan side, and at times I think he paints too rosy a picture of it. For one thing, the “cosmopolitan” side of these cities was the preserve of a wealthy elite, and did not affect most of the local people at all, or at least not in any advantageous way. And though I am sure that Mansel is correct in his assessment of the harm done by nationalism (much of the present tension in the region is the result of competing Arab and Jewish nationalism), the cosmopolitan paradise is, I suspect, overrated. In Lebanon before the civil war of 1975, for example, Mansel points out that deals were more important than ideals, and seems to regard this as a desirable state of affairs. But I wonder who prospered, and though those who prospered as a result of the war were an even smaller minority, I suspect that it was the very obsession with money that increased the dissatisfaction that led to the civil war in the first place.

In spite of this, however, the book is useful in helping to untangle some of the threads of mechantilism, captialism, nationalism and imperialism that affected and continue to affect the region once known as the Levant.

December 14, 2012

New Orthodox service book in Zulu and English

At a gathering of the clergy of the Archdiocese of Johannesburg and Pretoria we presented Archbishop Damaskinos with a copy of a new service book in English and Zulu, and copies were offered to all the clergy present.

Father Gerasimos and Archbishop Damaskinos at the clergy synaxis on 13 December 2012

The book has the Third and the Sixth Hours and the Reader’s Service, based on the Typika used in monasteries on days when the Divine Liturgy is not celebrated. In its present form it is designed for use in mission congregations for Sunday services when there is no priest, and it may be led by a deacon or reader. Some parishes use it if, for any reason, there is no priest available.

The Readers Service (Obednitsa, Typika) consists mainly of the parts of the Divine Liturgy that are not reserved to the priest or deacon.

It took ratrher a long time to get printed in its present form.

The new Readers Book in English and Zulu

In 1997 the African Orthodox Episcopal Church wrote to His Eminence Metropolitan Paul Lyngris, the then Archbishop, asking to be received into the Orthodox Church. The Archbishop asked me to teach them to prepare them for their reception into the Church, and gave his blessing for their clergy to be taught to use the Readers Service, which we then had partly translated into North Sotho. Later His Eminence Metropolitan Seraphim gave his blessing for it to be translated into Zulu, and we printed a few copies for use at courses and conferences, but we did not have money to print a large number.

Three years ago Father Daniel Sysoev, a priest who was doing missionary work among Muslims in Moscow, was shot dead, and a group of Serbian Orthodox Christians, inspired by his example, formed a missionary society in his memory. They wrote to Father Pantelejmon, a Serbian priest in Johannesburg, asking if they could help us to print liturgical books in local languages. Father Pantelejmon asked me if we had anything ready for publication, and I remembered the Zulu translation of the Reader’s Book. With the blessing of His Eminence Metropolitan Damaskinos 500 copies were printed by the missionary society in Belgrade, in memory of Fr Daniel Sysoev.

Remembering Fr. Daniel Sysoev : A Russian Orthodox Church Website: Today marks the third anniversary of the martyric death of Fr. Daniel Sysoev, who was fatally shot in the Church of the Apostle Thomas in Moscow on November 19, 2009. His work continues: books he wrote are being published, a missionary school named after him is functioning, and a benevolent fund in his name is helping the families of priests who have perished.

You can also read more about Father Daniel Sysoev on this blog.

December 8, 2012

Twenty years after the end of apartheid: the need to move on

One sometimes hears white people in South Africa saying things like “Apartheid was twenty years in the past, it’s time to move on and forget the past and stop talking about it.”

Blogger Cobus van Wyngaard discussed this in a recent post here … want dis nou eers 18 jaar later | die ander kant. He probably hears such things more often than I do, as we move in different circles, and in some ways the separation between those circles seems to be growing, perhaps as in the days of apartheid.

There seem to be three broad views on this:

Yes, we have a tragic past, but that was 20 years ago and we should move on

All our present problems stem from our tragic past, and our failure to solve them is because of the burden of the past

We need to learn from the errors of the past in order to solve the problems we face now and will face in future

The first is found most often in white people who supported apartheid in the past (and who sometimes like to ascribe all present problems to the incompetence or malice of the ANC government), and such comments often have a racist subtext (black people aren’t really competent to govern).

The second is found most often in black people who support the ANC in the present, and like to ascribe the failure to solve present-day problems (like the availability of school textbooks) to the legacy of the apartheid past, and such comments often have a racist subtext (all our problems were caused by wicked white people, and we poor blacks aren’t competent to sort them out).

I, and I think Cobus (if I have read his article correctly) , adopt the third view.

Saying that there are just three views is, of course, an over-simplification; there are many variations and overlappings. But it is a broad description, and I believe the first two are dangerous delusions.

Saying that apartheid ended twenty years ago and that it lies in the past and does not affect the present is delusional. Apartheid changed the landscape of the country, and twenty years later there is little sign that it has been changed back. Attempts to squeeze the toothpaste back into the tube are usually wasted effort. The massive ethnic cleansing that took place under apartheid has not been reversed. Twenty years ago most of the people in the suburb where I live were white. And twenty years after the end of apartheid most of them are still white. Twenty years ago the residents of Mamelodi, 15 km away, were mostly black. And now, twenty years after the end of apartheid, they are still mostly black. Let’s not kid ourselves: apartheid may have ended twenty years ago, but its effects are still very much with us.

Fifty years ago there were flourishing peri-urban settlements of mostly black people in places like Charlestown (near Volksrust) and Roosboom (near Ladysmith). These were places where black people lived and they kept chickens and a few cows and owned their own land. Some worked in nearby towns, but many were also productive small-scale farmers. They were forced off the land because these settlements were “blackspots” in areas that the apartheid map had marked as white. They were forced to move further from the towns, but in places where they lived in “closer settlements” where they could not keep cows or poultry, but had to commute to town in search of employment. Thus we solved the energy crisis, by making people travel ever-longer distances to work. Twenty years after the end of apartheid, the residents of Lady Selborne are still living in Ga-Rankuwa.

Now the land restitution process has restored the land in many such places to the original owners, or rather to their heirs, because the original owners are long dead. But the heirs have lost touch with farming. They grew up without cows and chickens, and lack the skills of their parents and grandparents. Handing them the land does not restore the status quo ante. The heirs often resort to “people farming” – sub-dividing the land and letting it out to commuters. They are sometimes absentee landlords, and sometimes crooks move in an “sell” the land to people desperate for a place to live. And so twenty years after the end of apartheid, the effects are still with us.

Apartheid not only changed the physical landscape, it changed the mental landscape as well. Forty-five years of Christian National Education and Bantu Education left their mark. People sometimes remark how much better-educated recent immigrants from other countries in Africa are. Some of the xenophobia we see is because Zimbabweans and Congolese sometimes find it easier to get jobs than South Africans, because they are better-educated, harder-working, and don’t have a sense of entitlement. But in spite of the traumas those countries have suffered in the last fifty years, they did not have Bantu Education. Christian National Education, and its Bantu Education variant, warped the minds of at least two generations, and the mantra “Apartheid was twenty years ago, we need to move on” is a product of those warped minds.

The ANC government has had nearly twenty years to change this, but though there has been much talk of “transformation”, it has not acted decisively to do so. The police force was demilitarised to some extent, then remilitarised, but there was no transformation, as the massacre at Marikana last August clearly shows. There was an attempt to reform education using “Outcomes-based Education” (OBE), but in order to work properly, OBE would require a radical retraining of teachers, and that did not take place. Teachers trained under the apartheid system carried on teaching the kids in the new South Africa using the same methodology and ideology in which they themselves had been trained. Very little was transformed. The ANC had some competent and creative people with a vision for the transformation of education, like John Samuel, but they were sidelined.

The ANC came up with a plan for a Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), and when it was elected said it was not negotiable, but within a year they had negotiated it away, and all that is left of it now is a nickname for jerry-built houses. So the ANC likes to blame apartheid for present problems, but it has also had twenty years to try to solve some of the problems caused by apartheid, and has largely failed to do so. The ANC can’t be blamed for failing to solve insoluble problems. It can be blamed for not trying harder to solve the soluble ones.

But, like Cobus, I approach this from a point of view of hope.

In spite of all the problems, much has been achieved. And that is another reason for not drawing a veil of amnesia over the apartheid past. It is too easy to forget the darkness from which we have come. If we are conscious of our shortcomings and failures, and the shortcomings and failures of the ANC government, we can thank the freedom that our democracy has given us to report those things. If we are conscious of corruption in high places, we can be thankful that we have a free press to make us aware of it. In spite of all the problems, someone, somewhere, must be doing something right.

Cobus writes of his rejoicing at the self-confidence of black high school kids asking questions about how often white people wash their hair. And I had a similar experience with black primary school kids in Melmoth, which would have been unthinkable thirty years ago when we lived there.

Apartheid can be blamed for some of our present-day problems, but cannot be blamed for the failure of people to tackle those problems. Our task should not be to blame or exonerate apartheid, but to recognise the problems that it caused, and try to solve them. Some of our problems are a legacy of apartheid, and pretending that they are not is a delusion. But recognising that is not an excuse for failing to analyse the problems and trying to think of ways to solve them now. We should not forget the darkness from which we have come, which is one of the reasons I have written a series of Tales from Dystopia on this blog. And we have indeed come a long way since then.

Cobus

December 6, 2012

Hipster Christianity redux

Is this you? Is this me? Someone tweeted (and I retweeted) a link to this article on Hipster Christianity: The Ex-Convert: On Hipster Christianity, and Their Defenses Against Atheism:

Here is a short list of cultural elements found in what I will call “College Hipster Christianity,” or CHC, gathered from the aforementioned article, various comments, and my own experience in this sub-culture:

Music such as Muford and Sons, Iron and Wine, Sufjan Stevens, U2, and when feeling especially spiritual, old hymns set to acoustic guitars or Gregorian chant. These musical choices as opposed to more mainstream top-40 hits or Contemporary Christian Music.

Authors such as Dostoyevsky, Flannery O’Conner, Tolkein, C.S. Lewis,Wendell Berry, and G.K Chesterton. Reading material should be simultaneously hip and relevant, while maintaining certain intellectual standards. The classics are always excellent choices, especially those with some sort of spiritual bent, like Augustine’s Confessions. It absolutely doesn’t include popular Christian literature such as The Purpose Driven Life or the Left Behind Series.

I’ve read several blog posts about “Hipster Christianity” in the last couple of years, and most of them seemed to me to be very wide of the mark, as I noted here a couple of years ago Hipster Christianity | Khanya. But the article quoted above comes a lot closer to the mark, at least for me. Though I haven’t read Flannery O’Conner or Wendell Berry, or heard any of that music, Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and G.K. Chesterton are among my favourite authors. Though, like the Artsyhonker, I disagree with some of the conclusions, at least there seems to be enough common ground to possibly have a conversation.

The linked article reminds me of some conversations I had with Emerging Church people about 3-4 years ago (we seem to have moved away from that now): Stuff Christian College Kids Don’t Like:

Just a few months after graduating from a Christian college, I found an article that encapsulated the curiousness of the community I was leaving. Called “One Island Under God,” it was based on a Facebook conversation by authors Anna Scott and Brian Buell that listed a very specific category: stuff Christian college graduates like. The inventory of interests unearthed by Buell and Scott is jarringly familiar—and perplexing. It includes The Princess Bride, Sufjan Stevens, Franny and Zooey by J.D. Salinger, “Social and/or sophisticated or exotic forms of smoking” (pipes, hookah, cloves, cigars), certain fantasy series (Harry Potter, Narnia, Lord of the Rings), and Settlers of Catan. Does anyone else feel like a pinned butterfly?

Though it doesn’t make me feel like a pinned butterfly, the pin is at least visible in the middle distance, moving around, and perhap-s threatening to come a bit closer. An perhaps if it gets any closer it may stick itself into this: Blessed are the foolish — foolish are the blessed : Notes from underground. Does the cap fit?

December 4, 2012

Something to gladden the atheist heart

This post was inspired by another blogger, James Highham, who said nourishing obscurity | Something to gladden the atheist heart: “Never let it be said that we neglect you guys. Here’s a little treat for you to convince you you’ve finally killed off that superstition”

I thought I would post something along the same lines, and here it is.

Voskopoje is a town in Albania, which is rather derelict today. In the 17th and 18th centuries, however, it was on some of the major trade routes across the Balkans, and it was a flourishing centre of trade and culture. Someone told me that it had twelve main disticts, each with a population of 1000 or more, and each district had two churches. Now the population of the whole town is probably less than 1000, and most of the churches are in ruins.

Voskopoje in 2000

In the 18th century it had the first printing press in the Balkans, and a famous school of ikonography.

The Turks, however, disliked it, and largely destroyed it.

One of the Voskopoje churches in 2000

Albania gained its independence after the Balkan Wars in 1912-1913, and then in the 1930s was invaded by the Italian Fascists. The Resistance was led by the communist Enver Hoxha, and after the Second World War they ruled Albania.

In 1967 Enver Hoxha decided to eradicate all religion, and so Albania became the first, and only, atheist state in the world. From 1967 not a single church or jammi (mosque) was open for worship. Most of the clergy were killed, and the few who remained alive were mostly either in hiding or in concentration camps.

The atheist paradise lasted from 1967 to 1991, when religious freedom was restored.

Monastery in the hills above Voskopoje

In the hills above Voskopoje there was a small monastery. In the Hoxha era no new monastics were allowed to join it, and when it was secularised after 1967 it was used for a while as an army barracks (Enver Hoxha had a war psychosis and a fear of total onslaught that made Magnus Malan look like a wimp). Then it was abandoned.

Between the monastery and the town there was also a luxury lodge/hotel for the use of high Communist Party officials. Of that, there is now hardly a trace. Not even ruins remain; it has gone as though it had never been.

During the atheist period, groups of communist youth used to come for weekend camps in the area, and they, no doubt with the encouragement of their elders and mentors, did their bit to contribute to the eradication of obscurantist superstition, as the following pictures show.

Frescos in a Voskopoje church, May 2000

The period of atheist civilisation was all too short, however, and traces of the previous barbarous superstition are still visible under the enlightened atheist graffiti.

Voskopoje frescoes, May 2000

The frescoes that were low down and within easy reach suffered the most damage.

Those that were higher up and closer to the roof suffered relatively less damage.

But superstition is superstition, and must be obliterated as far as possible.

And then came 1991, and the end of the atheist paradise. Such a thing had never been seen on earth before, and now, after a brief shining in the secular firmament, it was gone.

Religious freedom was restored, and a different kind of youth camp was held at Voskopoje.

This one was for the Muslim youth, whose minds had been twisted by the atheist propaganda of the years before, and so a couple of imams came from Iran to straighten them out.

They discovered that the iconoclasm of the atheists had not gone far enough, and that some ikons had survived the atheist paradise.

So in a new upsurge of iconoclastic zeal, they made up for the deficiency thus:

The new Albanian government, which did not look with fond nostalgia on the Enver Hoxha era, deported the imams, and said they did not want them inciting Albanian youth to destroy the monuments of Albanian culture, of which so little remained after the Turks and the atheists had done thier bit.

And in general, Christians and Muslims in Albania live in peace with each other, and in some places Muslims have helped with the rebuilding of Christian churches.

But some from outside Albania deprecate this lack of hostility, and would like to come and stir things up.

And iconoclasts, whether they are militant Muslims or militant atheists, remain iconoclasts.

December 1, 2012

Encountering spirituality

Spirituality is a word I dislike, and my aversion to it has grown over the years, though its popularity with other people seems to have grown in proportion.

I was moved to check this out after reading a post in Macrina Walker’s blog, On silence and silence:

A few years ago, while I was still in the Netherlands, I became aware of a certain media interest in monasticism. Despite their declining numbers and the secularization of society, monasteries continued to fascinate people and had even become rather fashionable destinations for those in search of some sort of inner peace.

What struck me then about this phenomenon was that it was fundamentally redefining monasticism. I read an article that managed to explain the meaning of monasticism for a broad public without once mentioning God or Christ. Instead, it told us that monastics withdraw from society in order to search for silence, for the heart of their life is concerned with what happens in this silence.

I did a search for “spirituality” in my diary, and the first occurence was this, which I wrote when I had just arrived at St Chad’s College, Durham, to study for a postgraduate diploma in theology.

Friday 14 October 1966

Then went to the Junior Common Room, where there was a meeting of the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius — an introduction to the Eastern Church by Benedikz and Father Bates. Father Bates, it appears, spends his holidays in Greek monasteries. The thing lasted three hours, and was incredibly dull. However, their theme this year was “God and Caesar”, and they are having a conference on that theme in about six months time — so perhaps things might improve, or at least something fruitful may be learned at the cost of boredom. Father Bates, and the English generally, seem to find the Eastern Orthodox Church quaint, foreign, and rather amusing. They roared with laughter at the description of the way a priest baptised a child in St Oswald’s, and washed the olive oil off his hands in the font afterwards, and then got all deadly earnest and serious over obscure points of spirituality.

My interest in the theme of “God and Caesar” was particularly strong at the time because I had just received a pile of South African newspapers from my cousin in Pietermaritzburg, detailing the first publishing of the “Improper Interference Bill”, which prohibited the discussion of politics between people of different race groups, and, when it became law, led to the demise of the Liberal Party.

I had also read about the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius, which was for Anglicans and Orthodox to meet and get to know each other better. I had looked forward to be able to attend a meeting, and found the first one I attended very disappointing. But that was the first time I mentioned “spirituality” in my diary.

The next mention came almost a year later, in a sermon preparation class:

Tuesday 5 September 1967

After breakfast, meditation and more sermon reading. This time it is Stu Prax, a very competent and well-constructed sermon on Sunday observance, and Hugh’s one on Jeremiah telling lies to save his own skin. It was also very good, and he threw out a vast number of ideas to be grabbed by the congregation. Piglet, in criticising, said something was a “false herring”, which caused much snorting from Brang, who himself said the sermon was more eastern than western, and that it reflected Eastern Orthodox thinking and

theology and spirituality.

Piglet was the Revd Eric Franklin, one of the college tutos, and Brang was the Vice-Principal, the Revd Herbert Langford, who had come to the UK as a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany in the 1930s, and converted to Anglicanism. They later had classes in “spirituality”, a concept that I found quite difficult to grasp, but it seemed to be the quality that English people found most interesting about the Orthodox Church. And it later appeared to me that some Orthodox people in England, aware of this interest on the part of the English, played up to it, and focused on it when speaking to English audiences, to string them along, as it were. The English seemed to find their idea of Orthodoxy more interesting than Orthodoxy itself.

When, however, I went to a seminar on Orthodox theology for non-Orthodox theological students in Switzerland and France in April 1968, led by Orthodox teachers, there was little or no mention of “spirituality”. It seemed that “spirituality” was something that Westerners expected to find in Orthodoxy, and not something that Orthodox Christians themselves were particularly interested in.

When I returned to South Africa some Anglican dioceses appointed “directors of spirituality”. One of them went to see an Orthodox priest I knew, and since I had been an Anglican, he asked me about it, because he was not sure what she was getting at. He said she seemed to regard the Orthodox Church as something from the “mystical east”, and “spirituality” as something rather spooky. And all I could say was that that had been my experience in England, where Anglicans who were interested Orthodoxy seemed to be obsessed with “spirituality”, and seemed to read their ideas of spirituality into Orthodoxy.

I read somewhere (though I now can’t recall where, and wish I could find it again) that “spirituality” in this sense is quite recent, dating from the 17th or 18th century, where it began to be used in the Roman Catholic Church. It had earlier referred to the spirtual authority of Western bishops, who were, on being appointed, invested with the “temporalities” and “spiritualitis” of their office — back in the days of prince bishops who were secular as well a spiritual rulers. Since I had been at university in Durham, that may serve as an example. The Bishop of Durham was a Lord Bishop of the County Palatine of Durham, and when the 1832 Reform Act threatened to strip him of most of his temporalities, he anticipated it by giving his residence, Durham Castle, for the establishment of a new university, the University of Durham, of which Castle is the oldest college. The bishop then went to live in Bishop Auckland. The “spiritualities” of his office would include his responsibilites as a pastor in the church.

In the Orthodox Church the Russian term “dushevnost” is sometimes translated into English as “spirituality”, but though the denotation coincides, the connotations are different. It might be better to translate it as “life in the Spirit”, a term sometimes used by Western Pentecostals and charismatics, and, as I have mentioned in another post, it is sometimes easier to discuss this with Pentecostals than with Western Christians who are interested in “spirituality”, because dushevnost refers to the life that Christians live under the guidance of the Holy Spirit rather than the spookiness of the “mystical East”.

November 25, 2012

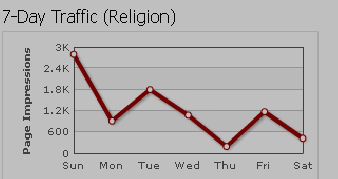

Drop in religious blogging?

If Amatomu is to be believed, there has been a sharp drop in bloggin on religion over the last week ot so.

Does this mean that blogging is a thing of the past, or does it just reflect the fact that Amatomu itself wasn’t working for the last week?

Does this mean that blogging is a thing of the past, or does it just reflect the fact that Amatomu itself wasn’t working for the last week?

It would be a pity if the blogosphere were really in such serious decline, and I hope that it is just a problem with Amatomu itself. But even that is rather sad, because Amatomu is one of the few places where one can get an overall picture of what South African bloggers are saying.