Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 60

June 30, 2013

Typefaces: on not practising what you preach

Someone drew my attention to an interesting article on why it is important to choose the right typeface to communicate effectively.

Unfortunately the effect was spoilt, because the body of the article was written in an ugly and difficult-to-read font.

Here are the first couple of paragraphs:

I’ve no idea what font it is, but the main reason that it is difficult to read is that the space between the letters is too small, and the letter i, particularly, tends to get lost among the surrounding letters.

I’ve no idea what font it is, but the main reason that it is difficult to read is that the space between the letters is too small, and the letter i, particularly, tends to get lost among the surrounding letters.

Perhaps that was deliberate, and they wanted to show how difficult it is to read the wrong typeface. But if that was their intention, they should have said so. Given the subject of the article, the typeface chosen certainly gives the impression that the article is not to be taken seriously, because the publishers so obviously don’t take it seriously themselves.

What they also don’t say clearly enough is what different typefaces are good for.

They are down on Comic Sans MS, and, in the example they give, rightly so.

Comic Sans is a very bad font to choose for multi-line text in paragraphs.

But it works quite well when used for one-line text, as in a presentation slide, for example, where points are made in one line. It is then quite readable, more so than many other fonts. But no one would want to read a book set in it.

Microsoft did the world a disservice when they made Times New Roman the default font for their word processor, because it was never designed for the page size that most people use to write stuff. It was designed for newspaper columns.

If you are writing on an A4 page split into three columns, by all means use Times New Roman. That’s where it works best. But if you are writing across the whole width of an A4 page, Bookman Old Style 12 point is much more readable.

Check any published book, and you will never find any that is set in Times New Roman. A book is usually somewhere between a newspaper column and a full-width A4 page, and the publishers usually choose a typeface that is easy to read at that page width.

What the article says is quite interesting — it’s just a pity the publishers did not see fit to take their own advice.

June 24, 2013

The Madiba factor

Today is the 18th anniversary of South Africa’s 1995 victory in the Rugby World Cup, and though we only watched it on TV, we went out afterwards to join the flag-waving hooting crowds driving up and down the streets of Pretoria celebrating. The image of President Nelson Mandela handing over the trophy to South African captain Francois Pienaar made such an impression that a full-length film was later made of it.

President Nelson Mandela handing over the Webb Ellis trophy when South Africa won the Rugby World Cup in 1995

Now former President Nelson Mandela lies critically ill in hospital, and for a long time his poor health has not permitted him to attend sporting functions.

On the day he was sworn in as president, 10 May 1994, Nelson Mandela attended the opening match of the Nelson Mandela Inauguration Challenge Cup, where South Africa beat Zambia 2-1, and that seemed to start a tradition — whenever he was present, South African sporting teams, apparently inspired by his presence, seemed to do well, and this came to be referred to as “the Madiba factor”.

While we watched those two matches at home on TV, we were present at the FNB Stadium in 1996 when South Africa beat Tunisia in the final of the Africa Cup of Nations.

So while he is ill in hospital, it is good to remember happier times, and how he inspired many South Africans, and not just the members of sports teams, to do their best.

It is sad, however, to see how his stay in hospital has turned into a media circus, with journalists encamped outside the hospital like vultures for a week or more. For what? All that they can produce is bathos, like the lines sometimes attributed to the British poet laureate,

Across the wires the electric message came

He is no better, he is much the same.

When he takes a turn for the better or for the worse, no doubt those who know will inform the world.

Perhaps it is because the journalists are so bored that they come up with stories like this: Helter Skelter In South Africa? Alarmists Spread Fear That Whites Will Be Massacred After Nelson Mandela Dies.

Some of us remember when those same alarmists said that whites would be massacred if Nelson Mandela were to be released from prison. Or whites would be massacred if South Africa were to hold free and fair elections (the vultures of the media flocked from all over the world to cover that one, but took off for Rwanda before the voting was over).

Some of us remember when those same alarmists said that whites would be massacred if Nelson Mandela were to be released from prison. Or whites would be massacred if South Africa were to hold free and fair elections (the vultures of the media flocked from all over the world to cover that one, but took off for Rwanda before the voting was over).

My wife was working at a school when one of these alarmist rumours was doing the rounds and it got some parents so edgy that they pressured the school authorities to hire security guards to patrol the school grounds on the day of the scheduled massacre. On the day one of the Grade I pupils, on seeing the patrolling security guards, rushed to the office and breathlessly blurted out, “The rumours are coming! The rumours are coming! I’ve seen one in the school grounds.”

June 13, 2013

Winter in Madrid: a spy novel

While I have posted the core of this review on Good Reads, I’m expanding it a bit here, because it gave me a lot to think about. It is a spy novel, but not the usual spy novel. There was a glut of spy novels during the Cold War, from about 1960-1990, so that one almost came to think of the genre as belonging specifically to that period. But this one is set 20 years earlier, in 1940, just after the end of the Spanish Civil War, so it also belongs to the genre of historical novels.

It has been also described in the blurb as a thriller and a love story, and I suppose that it is those too, though I didn’t find it a page turner. I took quite a long time reading it, one or two chapters at a time, because each chapter gave me something to think about.

I first learnt of the Spanish Civil War as a child, from reading Biggles in Spain. Biggles and his friends were charter pilots, and found themselves in Spain orking for and suspected by both Republicans and Nationalists. They find the political issues too complex, and when asked which side the hope will win, they say “The side that represents all true Spaniards”, or something to that effect.

I read and enjoyed other spy novels when I was at school — John Buchan’s books Greenmantle and The thirty-nine steps, though when I tried to re-read them when I was older I found them rather dull and pedestrian.

In 1960, just before the great spy novel boom began, Mad Magazine had a cartiin strip caled “Spy vs Spy”, which I enjoyed reading, and I always pictured it as being set in Spain, around the time of the civil war. But, like Biggles, and like Harry Brett in Winter in Madrid my inclination was like many outsiders, and not only fictional characters, to remain neutral.

In 1960, just before the great spy novel boom began, Mad Magazine had a cartiin strip caled “Spy vs Spy”, which I enjoyed reading, and I always pictured it as being set in Spain, around the time of the civil war. But, like Biggles, and like Harry Brett in Winter in Madrid my inclination was like many outsiders, and not only fictional characters, to remain neutral.

I was also interested in the book because the place and the period are the setting of one of my favourite recent films, Pan’s Labyrinth. This novel helps one to get the flavour and feel of that setting, and having read it, I would like to see the film again.

It also has something of the flavour and feel of South Africa during the apartheid era, though with some notable differences. I think the main difference is that in Spain the Nationalists, who were victorious in a civil war, were able to impose their system suddenly and forcibly, by military means. In South Africa the Nationalists won an election by a slender majority, and it took them twelve years and three more elections to really get up to speed.

But what is the book actually about?

Winter in Madrid by C.J. Sansom

Winter in Madrid by C.J. Sansom

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Harry Brett is a British soldier who was invalided out of the army after the retreat from Dunkirk, but he still wants to do his bit for the war effort, and is recruited by the intelligence services as a spy. He is a rather reluctant spy, however, especially when he discovers that he was recruited mainly to spy on a former schoolfellow, Sandy Forsyth, who is now a businessman in Spain.

He goes to the British embassy in Spain, ostensibly as a translator, but actually to find out what his old schoolmaate is up to. Harry had been in Spain before, where another school friend, Bernie Piper, was missing, believed killed, serving in the International Brigade on the Republican side in the civil war. Just before he went missing, Bernie Piper had had a love affair with a British Red Cross nurse, Barbara Clare, who had asked Harry’s help to look for him. But when Harry returns, Barbara was living with Sandy Forsyth, astensibly as his wife, though they were not legally married.

As a historical novel it is very well researched, and I think it does give an authentic flavour of post-war (civil war, that is) Spain, and the early years of the Franco regime. The British are anxious to keep Spain neutral, and are concerned that Sandy Forsyth’s business deals, rumoured to involve a gold mine, might make Spain’s economic survival less dependent on British goodwill. But the German and Italian ambassadors are obviously more favoured by Franco’s government, especially since they had helped the Nationalists to win the civil war.

In the heyday of the Cold War spy novels, most of them had no moral ambiguities. Those witten in the West either assumed, or set out to show that the Soviet Union and its allies were indubitably the bad guys. Only a few questioned this paradigm. This book, however, makes it clear that atrocities were committed on both sides, and that in such situations there are no “good guys”. And in that it chimes with my own vicarious experience.

When I was a student there was an Anglican monk, Brother Roger of the Community of the Resurrection, who was a kind of spiritual father to me, a guru, if you like. He gave me books to read, and discussed various kinds of philosophies. At one point I told him that I was attracted to anarchism as a political ideal, and he said he could never be an anarchist because he had seen what anarchist bombs had done during the Spanish Civil War. That rather shocked me, because I saw myself as an anarcho-pacifist, and the thought of promoting a political ideal by throwing bombs was very far from my thoughts. He did not say much about it, but I think he was there, like Barbara Clare in the novel, as an ambulance worker rather than as a combatant.

So the book shows something of the horror of civil wars, and how people from other countries who intervene (like the Germans, Italians and Russians in the Spanish civil war) only make things worse. And even those that don’t intervene, like the Bristish, also just make things worse.

Though the Spanish civil war was over before I was born, the wars of the Yugoslav succession were much more recent, and were also a kind of civil war. There were no good guys, but Western fiction written in that setting, like the Cold War spy novels, assumed that the Serbs were the bad guys, or tried to persuade readers that they were.

But in Winter in Madrid there are no good guys, and the bad guys are everywhere. Everyone betrays everyone else, and perhaps the biggest traitor of all is the Spanish Church, which betrays the Gospel, and calls to mind Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor.

I recently read a book by an old friend, John Davies, who was at one time Anglican chaplain at Wits University. The book is The faith abroad and is a treatise on Christian mission for English Christians. He notes that W.E. Gladstone (British Liberal prime minister in the late 19th century) was influenced by the Tractarians, and was Prime Minister when the Privy Council declared that the Anglican Church in South Africa was a voluntary society having no legal identity with the Church of England.

For him, one of the great lessons of the case of the Church in South Africa was the “dispelling of the dangerous and mischievous idea which undoubtedly weighs upon the minds of many of this country… that when you take away the legal sanction from spiritual things, then spiritual things lose all their force and vitality.”.

The force of Mr Gladstone’s warning applies in any establishment context. If religion does depend on legal sanction, then what is important in religion must what is felt to be important by those who have acquired the power to make the law, the secular power-bearers. So religion can become a kind of spiritual police, operating in the interest of the authorities. In that case, it will probably fail to be good news to the poor — which is the decisive question for the followers of Jesus. It is no use having Good News unless we ask, Good News for whom? A church which is overtly a device for congratulating the powerful on being powerful will have its work cut out to persuade the powerless that it can be on their side also.

This is a predicament for the white-based churches in South Africa. Even if, as in the case of the Anglican Church, a majority are black, and even if the church is well-known as a critic of government, when white leaders protest against bad laws they are inevitably contributing to the greatest of all South African fallacies, namely that politics is a matter of white people arguing with white people about black people.

.

And, as Winter in Madrid clearly shows, during and after the civil war the Spanish church had become “a kind of spiritual police, operating in the interest of the authorities”. But that is not a temptation that was peculiar to the Spanish church in 1940. It is true anywhen and everywhere.

June 5, 2013

Who isn’t missional?

Fifty years ago people were saying things like “The church is missionary by its very nature”. Now they are saying things like “The church is missional by its very nature”, as if they are saying something new.

Is this anything more than playing word games?

I hadn’t thought about this for a while, but it was sparked off by reading a blog post here, which said, among other things:

Tony Jones has a great reflection on his blog today about labels such as “neo-Reformed,” “Emergent,” and “missional.” It comes in response to the intriguing “Why This Book?” video put out by David Fitch and Geoff Holsclaw to promote their new book Prodigal Christianity: 10 Signposts into the Missional Frontier.

Tony writes,

“[Missional]‘s a term that basically anyone can use for what ever purpose they want — from a stalwart Southern Baptist neocon like Ed Stetzer to an Anabaptist pacifist like David Fitch. And then you’ve got the neo-Barthian camp like Darrell Guder and John Franke. They’re all ‘missional,’ and so are a dozen church planting networks like TransFORM, Forge, and the Parish Collective.

“So here’s a test. Imagine a Christian leader saying this: ‘I’m not missional.’

“No one’s going to say that. Not a PC(USA) pastor, and not a PCA pastor. Not a just-war Augustinian, and not an Anabaptist pacifist. Scot McKnight will say he’s missional, and so will Brian McLaren. So will the pope. So will I. …

So who isn’t missional?

Well, all the people who used to need to be told that “the church is missionary by its very nature” for a start.

This was sparked off by a discussion on Facebook on the relation of the pastoral and missionary (or missional) aspects of the Church. In the course of the discussion Fr Andrew Stephen Damick said:

When I said by implication that pastoral care was about making disciples of Christ, I didn’t also say that *only* pastoral care does this. My comment was in response to your remark that “Mission, is simply making disciples, and it isn’t necessarily tied to ‘Pastoral Care’.” That is, I was asking why you seem to think that pastoral care might be something *other* than making disciples of Christ.

Anyway, I think I may be getting a better idea of what you meant by “missional,” but it seems that your use is mainly “fulfilling the Great Commission,” which would then mean that you’re saying “A Church that isn’t fulfilling the Great Commission isn’t fulfilling the Great Commission.” But that still leaves me wondering what the actual content of that is.

Perhaps your quibble with NewSpring and crew isn’t so much that they aren’t “missional” but that you disagree on what the Great Commission is about. (I imagine they might claim to be “missional.”)

So I’m still wondering what the need for the new term “missional” is. Is it a specific interpretation of the Great Commission? The text is “Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you.” What does that mean in “missional” terms that’s *different* from how it’s been interpreted up until now? (By whom?) And do “missional” types place a big emphasis on baptism? It certainly seems prominent in Christ’s words.

I’m kind of an English language geek, and of course I have a professional interest in these things, so whenever I see a new word being put forward, especially being given theological weight, I want to know exactly why this new word is needed and nothing else sufficed before, and I also want to know exactly why there is a theological warrant for something that is supposedly new. (As an Orthodox Christian, I am self-consciously suspicious of everything new.)

And then he added a link to the article I quoted from above. And as another English language geek, and a missiologist of sorts, I too have an interest in these things.

Again, going back fifty years or so, someone defined mission as “What the church is doing when it isn’t sitting in its pews” (and yes, many Orthodox churches in the West also have pews nowadays).

And, as Fr Andrew Stephen points out, “making disciples” is part of the pastoral task of the Church, as well as part of its missionary/missional task.

June 4, 2013

Civil Rights leader, preacher Will Campbell dead at 88

I was rather saddened to see this news item, posted by a distant cousin on Twitter, Civil Rights leader, preacher Will Campbell dead at 88.

Who was Will Campbell, and why should anyone in South Africa have heard of him?

I first learnt of Will Campbell when I got sick in Cape Town, and was taken in and nursed by a Methodist minister, Theo Kotze, and his wife Helen. That was over 40 years ago, in 1972, when the police were rioting in the Anglican cathedral in Cape Town, and there were student protests all over. We were talking about all that, and the response of Christians to the growing repression. And Theo handed me a book and said “Read this. It’s far more radical than anything I’ve ever come across.”

Up to Our Steeples in Politics by Will D. Campbell

Up to Our Steeples in Politics by Will D. Campbell

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

So I read it on my sick bed, and got about halfway through.

But there was something that jumped out at me on the first page, which struck me as very radical, and very orthodox, not to mention Orthodox.

Back in those days everyone was talking about Christians being activist, and saying that we should not be concerned about status but about function. Being a Christian was not enough, you needed to do something. You had to do theology.

I wasn’t Orthodox in those days, but I had been exposed to Orthodoxy (at St Sergius Institute in Paris, for Holy Week) and it had got me reading some Orthodox books, and finding that they were saying things that I had been looking for for a long time.

And here’s this book by this Protestant preacher from the Deep South in the USA, and he was saying the same kind of thing.

And the thing that jumped out at me on the first page was this:

We agree with those who have reminded us in recent years that the Christian faith is indicative (the fact that God reconciles the world in Christ), not imperative (Go to church! Do not drink bourbon! Feed the hungry! Search and destroy!

There was, and is, a great deal of talk about “reconciliation”. But Will D. Campbell and his collaborator James Y. Holloway said that one thing that looked like an imperative in the New Testament, “be reconciled” (katallagete) was a different kind of imperative. It “calls attention to a special kind of behavior by the Christian toward the world, behaviour which ‘does’ by being, ‘acts’ by living, that is, being and living as God made us in Christ.”

For more on this, see this post from a couple of years ago Reconciliation | Khanya, where I quote more extensively from Campbell & Holloway.

And if anyone lived his faith, and acted by being, it was Will D. Campbell. The Tennessean had this to say about him:

A white man from Mississippi walked with black children through a frothing mob at Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957, helping to integrate Arkansas public schools.

Later, he was the only pale face at the founding of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He also played a crucial – though subtle – role in integrating Nashville’s shops and restaurants.

That same man, Will Campbell, was the personal pastor to people – terrorists, we’d call them today – whose violent mission was to make sure the South would never integrate.

The civil rights movement, in which Will Campbell played a significant part, did not put an end to racism, though it did help to eliminate many of the instiutionalised expressions of it. Other social issues came to the fore, and Will Campbell was there. As the first article cited above notes,

“If you’re gonna love one, you’ve got to love ‘em all,” he repeated thousands of times.

For the past 40 years, at least until a May 2011 stroke left him in a West Nashville medical care facility, Campbell broadened his ministry. He wrote books that drew praise from former President Jimmy Carter, Robert Penn Warren and others. He campaigned mightily against abortion and the death penalty.

Though I never met him, he had a huge influence on my life. May his memory be eternal!

May 26, 2013

Ovamboland, Namibia 17-20 May 2013, with flashbacks to the 1970s

After leaving the Etosha National Park though the King Nehano Gate, and having driving licences and car papers checked by the police, the flat grassland continued beyond the park, but the herds of grazing animals on the other side were cattle, of which there were many, but there was no sign of human habitation.

After about 20 km travelling on a good gravel road we came to the main tarred road from Tsumeb to Ondangwa, and the vegetation changed again to thirstveld bush, but it was altogether different from the last time I had travelled along this road over 40 years ago. Then it was uninhabited bush, now it was thoroughly urbanised, or at least like a peri-urban area, with village succeeding village. There were a few stretches of road with a 120 km/h speed limit, but it did not feel right to travel at more than 90 along them, and then there would be an 80 sign, followed by two 60 ones. All along the road were bars and shebeens with fanciful names, mostly built with concrete blooks plastered and corrugated iron roofs. Every second shop advertised MTC, the main Namibian cellphone provider.

There was no sign of traditional Ovambo homesteads with their labyrinths at all. It was all square houses of the type regarded as so desirable by 19th-century Western missionaries, though I’m not sure that they would have been pleased to see their dreams fulfilled in bars and shebeens. That continued until we reached signs of the typical Ovamboland vegetation, the tall palm trees, but instead of the open parkland, it was filled with vistas of ugly concrete buildings. There were stagnant polluted pools with rubbish in them.

Forty years ago Ovamboland barely had a cash economy, and the economy was based almost entirely on subsistence agriculture. Now it was clearly cash and service industries. I wondered how much of the change had been due to the South African military occupation of the 1970s and 1980s, and how much to the 20 years of independence since then.

We reached Ondangwa at about 2:00 pm, 256 km after leaving Halali, and went shopping for groceries at a Shoprite Usave store, which was Friday afternoon busy. Val went in and shopped, while I stayed with the car, as Nancy Robson had warned us about petty crime. We left again about 2:30, and drove towards Oshikango, and almost the whole way seemed to have a 60 km/h speed limit, again with shops and bars in a continuous urban development.

One of the many bars and shebeens alongside the main roads in Ovambioland, Namibia

We stopped to take a photo of a couple of the shops with fanciful names, the Fanny Resting Bar and the Water Melon is Life across the road. A couple of guys came and asked for R50.00. There was none of the traditional Ovambo greeting with polite enquiries about health or anything of that sort. Just “Give me fifty Rand” — not even Namibian dollars. They were wearing fairly new clothes, tshirts and so on, so did not look all that poor, so we just drove off, having seen more evidence of the cash economy. We followed Nancy Robson’s directions to Odibo, which were useful, as we would never have found it otherwise, and that too had changed so as to be almost unrecognisable, and seemed to be almost in the middle of town. The trees had grown too.

Shops in Ovamboland have quite fanciful names

We stayed in the guest house, which had self-catering accommodation for visitors, and met old friends, among them retired bishop Nehemiah Shihala Hamupembe, and his wife Ndalipo.

Shihala Hamupembe with daughter Ndahafa on Durban beach in 1975, when he and his family spent a vac with us when he was a student at the Federal Theological Seminary in Pietermaritzburg

When I first met him in 1970 he was the youth organiser for the Anglican Church in Ovamboland, and was on his way to Zambia for a year-long youth leadership course at the Mindolo Ecumenical Centre there. He stayed with us in Windhoek for a couple of days before leaving, and as a result of a chance message over heard on a police radio, we thought that the police had been given orders to prevent his departure, so hastily brought it forward a couple of days. Timothy Shimbode, the son of a priest in Ovamboland, who worked as a baggage handler at the airport, told me afterwards that Shihala had been questioned quite a bit by the police before he left. On his return at the end of the year he spent Christmas with us in the house we were staying in in Klein Windhoek, and the police questioned him about not having a pass. When we pointed out that he had just arrived back in the country, and the pass office was closed as it was a public holiday, they left. They weren’t looking specifically for Shihala, though; they had been called by a nosy neighbour who didn’t like the idea of blacks and whites staying together at the house.

A year later, in December 1971, the Diocesan Standing Committee had met and considered a manifesto on theological education, in which I had proposed the use of theologicval education by extension and the ordination of self-supporting priests and deacons in local congregations in Ovamboland and elsewhere. The standing committee accepted the manifesto and appointed me as convener of an education subcommittee to implement it, with Sihala Hamupembe, the Revd Willy van der Sijde and Toni Halberstadt as the other members. Within a couple of months Toni and I were deported from Namibia, so not much came of it at the time.

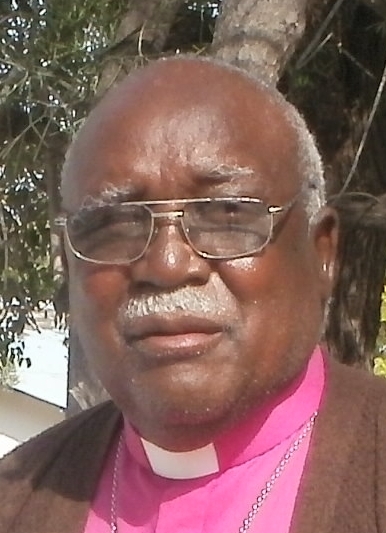

Bishop Emeritus Shihala Hamupembe in 2013

But now, more than 42 years later, we attended a graduation ceremony in St Mary’s Church in Odibo, presided over by Bishop Emeritus Shihala Hamupembe, where the things we had proposed at that earlier meeting had been fulfilled.

At the graduation ceremony 13 students received certificates in counselling, two received the award in theology, and 16 received the Certificate of Competency in Theology, four with distinction. The choir of the Diocesan School of Theology and Ministry sang several items.

It was rather strange to see first beginning of something, and the way it had developed after forty years, without having seen anything in between. But that was the same with Shihala Hamupembe. I had known him as a student in the 1970s, and was meeting him again as a retired bishop, but had seen nothing of what happened in between.

In 1975 he was a student at the Federal Theological Seminary in Pietermaritzburg, and as it was too far to travel back to Namibia for the July vacation, he and his family came to stay with us in Durban North. I was banned at the time, and when our church youth group wanted to go to Zululand for a camp, I could not leave Durban, so Sihala went with them as adult chaperon, putting his training as a youth leader from Zambia to good use. It was probably unusual for South Africa in those days for a bunch of middle class white kids to go on a camping trip with a black youth leader, but if the parents had any objections, they never voiced them, or at least not in my hearing.

Graduation of TEE Students at St Mary’s, Odibo, on 18 May 2013, Bishop Shihala Hamupembe presiding

At the graduation Bishop Sihala spoke of those days, that when South Africa was under Namibia, it was easy for Namibians to go to South Africa for theological education — all they needed was identity documents. Now, however, they demand a large deposit for students, in case they have to deport them, and also medical aid, and, as he pointed out, in Namibia even the bishops don’t have medical aid.

After the graduation at St Mary’s Church, Odibo

That is rather sad for education in South Africa. At one time we were talking of having an Orthodox Seminary in southern Africa, to serve the whole subcontinent, as the one in Nairobi serves East Africa, but if there ever is such a thing, South Africa will not be the place for it, because of the bureaucratic hurdles that are placed in the way of educational institutions, and especially foreign students. A pity, because by becoming an educational centre for Southern Africa, South Africa could also improve its own education system which still bears the marks of the apartheid period and the legacy of Bantu and Christian National Education. Zimbabweans still tend to be much better educated than South Africans. Justin Ellis said that that is probably a result of the work of Garfield Todd and his disciples, who had a vision for education in Zimbabwe long before it became independent, and laid a strong foundation that persists to the present. In South Africa Bantu Education weakened whatever foundation there was, and very little has been done in the last 20 years to trasnsform it, despite all the talk about “transformation.” The few visionary educationists that we have had, like John Samuel, have been sidelined.

TEE graduates at St Mary’s, Odibo

There was another similar encounter that afternoon, when Sister Gertrude took Val and me to see Joseph Kakehongo, a venerable old man, at Onekwaya, about 30 km from Odibo. We we were treated to a sumptuous feast at the Kakehongo household, and, as with Shihala Hamupembe, I had not seen Joseph Kakehongo for about 40 years.

Kakehongo family with Val Hayes and Sr Gertrude, CHN at Onekwaya, Namibia

I had met Joseph when I first went to Namibia in 1969 and he was a schoolboy at the Döbra Catholic High School just outside Windhoek. On Sunday mornings after church services in Windhoek Dave de Beer and I went out to hold services at isolated camps for road and railway workers out in the bush. Most of the workers were contract workers from Ovamboland, and we often used to pick up Joseph on the way, and he would come and help with the services, and translate things into Kwanyama.

In 1973 Joseph and Steve Singleton from the UK attended a Methodist youth leadership training course in Durban when I was living there, and I saw quite a bit of them, So again, I had the rather strange experience of meeting someone I had known as a student, and now seeing him in retirement, without having seen anything that had happened in between. Joseph had had a serious heart attack earlier, and had spent several months in hospital. We met his second wife (without having ever known the first), who is a nurse and so able to look after him.

Joseph Kakehongo at home in Onekwaya, 2013

Sister Gertrude, who took us to see Joseph, was something of a surprise too. She was wearing the habit of the Community of the Holy Name, which we knew well from Zululand, where there had been four CHN convents when we lived there from 1977-1982. Sister Gertrude said she was from Lesotho, and had been in Ovamboland for 8 years, and had learned to speak Kwanyama. It was a big contrast from mountainous Lesotho, since Ovamboland is entirely flat, and children who have grown up there only see mountains in pictures in books. After visiting Joseph Kakehongo, she took us to see where she and another CHN sister were helping three local women to establish a monastery, the Community of the Good Samaritan.

Two sisters from the Community of the Holy Name in Lesotho have been helping to establish an Anglican sisterhood in Ovamboland

One person I had hoped to see was Fr Lazarus Haukongo, who also lives at Onekwaya, but unfortunately he was away at his farm. He and I had been involved in an interesting mission project in the Kaokoveld, and one of the things I had hoped to discuss with him was how it had turned out later. Abraham Hangula, an evangelist in Windhoek, had told me that there were Anglicans in the Kaokoveld, and said we should follow them up. I looking in old files in the diocesan office, and found correspondence with one Thomas Ruhozu, so I wrote to him, and when there was no reply I thought my letter must have gone astray. Then one day he suddenly appeared on my doorstep in Windhoek, having travelled 400 miles from the Kaokoveld.

The diocesan synod happened to be meeting at the time, so I was able to intoduce him to Fr Lazarus Haukongo, who knew a little Herero, and promised to visit him. I gave him some books to read, and we conversed in my limited Herero and his limited English. At the end of his stay I took him to see the Herero chief, Clemens Kapuuo, who interpreted for us, and so Thomas was able to give his version of the mission plan we had discussed, which was that he would go home and evangelise. Three months later Fr Lazarus visited him, and admitted 18 catechumens. A few weeks later he returned and baptised the 18, and admitted another 25 catechumens. Then I was deported from Namibia, and I don’t know what happened after that, but hoped to ask Fr Lazarus.

St Mary’s Church, Odibo, Namibia

Back in the present, on Sunday morning, 19 May 2013, with the permission of Fr Johannes Kandume, the Rector of St Mary’s Church at Odibo (whose father, Fr Jonah Kandume, I had known as a priest), Val and I sang the Hours of Pascha in the chapel, and I wondered if that was the first time there had been an Orthodox service in Ovamboland. Later we attended the Anglican service, and then went to lunch with Nancy Robson, who had been born at Odibo, when her parents were working there in the early days of the Anglican mission, and had later returned to work in the hospital as a nurse. On this trip Nancy helped us a great deal by contacting some of our old friends and putting us in touch with them again.

Nancy Robson and Val Hayes at Odibo May 2013

One of the people we met over lunch was Loth-Chappel Haukongo, who remembered an epic journey we had made after the Anglican synod in Windhoek in 1971. He had an interesting scrapbook, with press cuttings of various events, one of which was a report in Die Suidwester, the National Party newspaper. It had a report of the 1970 synod, expressing shock, horror and moral outrage at the “mixed” (bont) nature of the gathering, which it compared to a hippie love fest.

Loth-Chappel Haukongo: he remembered a tragic homecoming over 40 years earlier

But the 1971 synod was marred by tragedy, as a bakkie taking some of the synod representatives back to Ovamboland crashed on the way, and two were killed, while several others were in hospital. The bakkie was a write-off, and the ones who were less severely injured were stranded in Windhoek. So I volunteered to take some of them when I took Thomas Ruhozu back to the Kaokoveld. I didn’t have a permit to enter Ovamboland, but we decided to cross that bridge when we came to it and trust the Lord to deal with it. Among those who came with me were Loth-Chappel and Toni Halbestadt, who was then teaching at St Mary’s, Odibo.

We set out early in the morning, and dropped Thomas Ruhozu at Kamanjab (none of the rest of us had permits to enter the Kaokoveld, so that was as far as we could take him) in the late afternoon, and we drove throught the gathering dusk on the gravel roads to Outjo and Otavi, where we reached the tarred road to Tsumeb and Ondangwa.

Just before we reached Oshivelo, the gate to Ovamboland, I climbed into the back of the bakkie and hid under a mattress, while Toni drove through the gate. As we drove beyond the gate I felt one of the rear tyres going flat, but we did not want to stop within sight of the gate. When we did have to stop, we changed the wheel about midnight. On the left was the Etosha National Park, with its game-proof fence, but while we were changing the wheel we could hear a lion roaring off to the right, in the unfenced bush. Now, as I have written above, the road is all over bars and shebeens, but back then it was uninhabited bush.

We arrived at Odibo about three in the morning, and I slept on the floor of Toni’s room, and spent the next day trying to see what I could see of Ovamboland while still there, and Fr Lazarus Haukongo took me to see a couple of the parishes along the Angola border, including his own parish of Holy Cross, Onamunama. A couple of years later that ended, as the South African military occupation began, and vegetation, churches and people were systematically and forciblhy removed from the border area.

On the old road from Odibo to Oshikango, some parts of the countryside look much as they did 40 years ago

While we were reminiscing about these things Nancy remarked that people no longer liked to speak of Ovamboland, but only referred to Owambo, becauser “Ovamboland” sounded too colonial. Such are the vagaries of political correctness, because in 1970 the politically correct term, from the point of view of the National Party, was Owambo, which was the official name of the “homeland”. Since we disagreed with the homelands policy, we deliberately referred to Ovamboland, and in any case, Owambo, as we, and many Ovambo themselves, understood it, extended north of the border to include as sizeable chunk of Angola, then a Portuguese colonial territory, so we tried to avoid using the word “Owambo” to refer to the Nationalist Party’s Bantustan.

St Mary’s Anglican Mission, Odibo, Namibia

Those were also the days when Anglicans messed up demographic statistics, because the figures showed that there were more Christians than people in Ovamboland. That was because most of the Anglican parishes were within a couple of hundred metres of the border, and half the church members lived in Angola — that is, before the South African military occupation from about 1975 onwards put an end to it.

Shirley Handura

In the guest house where we were staying was another link with the past. Shirley Handura, from the diocesan office in Windhoek, was staying in Odibo for a few days to try to sort out some of the problems with the financial records of the hospital at Odibo. When I lived in Windhoek 40 years ago, in a community, Shirley’s mother-in-law, Dinah Handura, did our laundry.

Her presence showed that some things do not change.

In 1969 David de Beer, after completing his B.Com degree at Wits University, came to Odibo to be accountant at St Mary’s Hospital. A few years before Dr Anthony Barker, the medical superintendent of the Charles Johnson Memorial Hospital in Zululand, had spoken at a conference of the Anglican Students Federation (ASF) and challenged students to “give a year of your life” and work for the church for a year after graduation, as thanksgiving to God for the educational opportunities they had enjoyed. Dave de Beer was one who did so, but his permit to stay in Ovamboland was withdrawn shortly after his arrival, and on his way back to Johannesburg he called at Windhoek to say goodbye to Bishop Colin Winter. The bishop asked him to stay on in Windhoek as diocesan secretary and treasurer, which he did, until being deported from Namibia three years later, along with the bishop, Toni Halberstadt and me.

Now here was Shirley, doing the same job that Dave de Beer had come to do, and facing very similar problems.

Fr Lukas Katenda, diocesan secretary of the Anglican Diocese of Namibia

We also met Fr Luka Katenda, the diocesan secretary, who was in Odibo for the graduation, and was doing the other half of Dave de Beer’s old job, and no doubt also facing similar problems. Some of the problems may have changed, however, with the growth of the cash economy. Dave de Beer had to face questions from the auditors about journal entries balancing the sale of books against hostel feeding. Back in 1969 people paid for books with baskets of corn, calculated at the rate of 25c per basket. The corn was then used for feeding the boarders at the school hostel. Perhaps now the problem is to persuade all those bar and shebeen owners to tithe their profits!

Oshikango, the nearest town, has grown enormously, with many signs of economic activity. Actually the last time I saw it I was not paying it much attention, but was concerned only to pass through as quickly and unobrustively as possible without being spotted by the police, lest they ask for the permit that I didn’t have.

But there’s more about that in the next post here.

You can see an index to all these posts of our travelogue of Namibia and Botswana here.

May 12, 2013

Sunday in Windhoek: Quaker meeting and walking the dogs

Sunday 12 May 2013 – Thomas Sunday

At 6:30 we went for a walk round the Avis Dam with Enid and Justin Ellis; they take their dogs for a walk there every Sunday morning with their friend Helen Vale, a retired English lecturer from the University of Namibia.

Walking the dogs at the Avis Dam, Windhoek: Justin Ellis, Val Hayes, Enid Ellis, Helen Vale

After breeakfast we went to Helen’s house with Enid and Justin for their Quaker meeting. Enid had thought there was an Orthodox Church in Windhoek, but it turned out that it was a Coptic one, so we went with them to their Quaker meeting instead.

Coptic Church in Windhoek

I was reminded of something Fr Alexander Schmemann once wrote, about attending Western Ecumenical meetings, and the organisers regarded the Orthodox Church as belonging in the “liturgical” category of their categorisation of “liturgical” and “non-liturgical” denominations. But Fr Alexander felt uncomfortable with the categorisation, and said that he would have been more at home among the Quakers. The Orthodox tradition of hesychasm has a lot of similarity to the Quaker understanding of worship, and so we sat for an hour in silence, and I silently recited the Jesus Prayer: Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, have mercy on me a sinner.

Helen Vale – the Quaker meeting was held at her house

Later Enid took us on a drive around Windhoek, to see how the town had grown, and how things had changed. There were new suburbs, new industrial areas, and many new buildings.

The Christus Kirche in central Windhoe used to stand alone at the top of a hill overlooking central Windhoke. Now it is surrounded by taller buildings

In the late afternoon we went to see my old friend Hiskia Uanivi, whom I had known forty years ago as a seminary student at the Paulinum in Otjimbingue. Now both he and the Paulinum are in Windhoek, and he is leader of a church called the Archbishopric of the Divine Word. When he registered it with the government they told him that the name should not look anything like that of the Assemblies of God, and it sohuld not have God in the title, so as a result he became a kind of archbishop by default. He told us something of his life since I had last seen him, and also some of his early life, and it was really good to see him again.

Steve Hayes and Hiskia Uanivi

After completing his course at seminary Hiskia went on a communication course in Kenya, and then acted as a liaison between those engaged in the liberation struggle both inside and outside Namibia. He later moved to Angola, and there was a confused period when Swapo was looked upon with suspicion by the MPLA government in Angola, because they had fought alongside Unita gainst colonialism, and suddenly Swapo fighters against South African rule in Namibia found themselves allies of a sort with the South African government, which supported Unita. Eventually Hiskia thought he was in danger from different factions in Swapo, and sought and obtained political asylum from the Angolan government.

May 9, 2013

Windhoek: family and old friends

After taking two days to travel to Windhoek, Namibia along the Trans-Kalahari Highway (which you can read about here and here), we spent our first couple of days (8 & 9 May) looking up old family in the archives, and seeing old friends.

We are staying with Val’s cousin Enid Ellis and her husband Justin in Klein Windhoek, not far from the house where I lived over 40 years ago.

Val Hayes & Enid Ellis, Klein Windhoek, 8 May 2013

We spent much of Wednesday 8 May in the archives, now housed in a new building a little out of the centre of town, looking for information on the Green, Stewardson and related families. We took a lunch break with Enid and Justin, and tried to unravel the mysteries of the Namibian cell phone system.We had bought SIM cards for our cell hpones at the border, but were having difficulty in getting them to work.

Windhoek has grown a lot — I suppose that is only to be expected after 40 years. A lot of the old familiar land marks are there (the city council seems to have good policy of preserving historic buildings, or at least their facades), but there were a lot of new tall buildings in the background in some places. Some scenes remained familiar though, like these:

View from the front of the new National Archives and Library building in Windhoek, 8 /may 2013

Thursday was Western Ascension day, and a public holiday in Windhoek, so the archives were closed. It was also nice to have a public holiday where, unlike South Africa, many of the shops and places like the Archives are closed, and there is much less traffic on ther streets. In South Africa public holidays tend to turn into a shopping frenzy.

We spent the early part of the morning with the Ellisd family, where Justin was making bread, chatting and having a leisurely breakfast of pancakes.

Hugh, Justin & Enid Ellis, Tursday 9 May 2013. Justin kneading bread.

Then we met two old friends, Assaria Kamburona and Kaire Mbuende, whom I hadn’t seen for forty years, and Val had never met them. Assaria Kamburon as now bishop of the Oruuano Church. Kaire Mbuende’s father Gabriel Mbuende had been secretary of the Oruuano Church when I lived in Windhoek, we sometimes travelled together to Goibabis, where Assaria Kamburona then lived.

Bishop Assaria Kamburona, Val Hayes & Kaire Mbuende, 9 May 2013

Assaria told us something of his life story, which i won’t reproduce in full here, but he was born at Mosita near Mafeking in South Africa in 1932, and attended a school there run by the London missionary Society. In 1942, when he was ten, his family returned to Namibias, and the lived inj Epukiro, north of Gobabis. He had difficulty at first, as he spoke only Tswana, Sotho and English, and in the school at Epukiro thjey used only Afrikasans and Otjiherero. He arranged with some of the teachers to teach them English, and in return they would teach himk Otjiherero. One of his teachers was Gabriel Mbuende.

He left school after Standard 6 (Grade 8) and worked as a cleaner and mail sorter at the Gobabis post office, and three years later, when the Standard Bank opened a branch in Gobabis in 1954, he went to work there. As a young man he became involved in politics, and after the massacre of people protesting against the forced removal of the Windhoek old location in 1959, he was sacked as a potential trouble maker, and made his living selling bread, sweerts and liquor. The main politically active organisation in those days was the Herero chiefs council, but this was regarded by the Unioted Nations as too tribal, and they would prefer to deal with wider political organisations. So the South West Africa National Union) SWANU and the Ovamboland Peoples Organisation (which later became Swapo) were foremed, but they all worked together. In those dayus Assarias was quite active in smuggling political activists (including Sam Nujoma, who later became president of Namibia) across the border to Botswana. He himself wanted to go with them, but the Herero chief, Hosea Kutako, said that his work should be spiritual, and he should stay and be a minister in the Oruuano Church.

`When we arrived at Kaire Mbuende’s house on the outskirts of Windhoek, Assaria had what Val called a “Simeon moment” — “lord now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace”, because a black man like Kaire Mbuende could live in a nice house with a nice garden.

Kaire Mbuende also has a very biblical garden. He loves gardeningm and there are rows of vines and olive trees, and also clementines (which are related to naartjies).

Kaire Mbuende’s garden, with the Auas mountains in the background. 9 May 2013

When I met Kaire Mbuende 40 years ago he was a young student. Since then he has been active in academic and public life, and is also a historian. His life story is easily accessible on the web.

The story of our Namibian holiday continues here.

April 28, 2013

Palm Sunday 2013

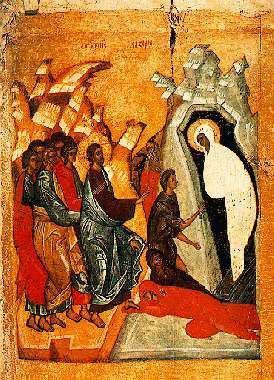

We, and our Mamelodi congregation, were invited to St Thomas’s Orthodox Church in Sunninghill for Vespers of Lazarus Saturday/Palm Sunday. Fr Pantelejmon arranged with one of his parishioners, who runs a taxi business, to send a 16-seater Toyota Quantum to fetch people from Mamelodi, and some brought members of their families who had never been to an Orthodox Church before.

Let our prayer arise in Thy sight as incense

At the end of Vespers the children were given bells to hang around their neck, a reminder that it was children who welcomed our Lord in Jerusalem.

Chyildren receiving bells and willwo branches

At the end of Vespers there was a procession around the church. In Serbia palms are rare, so people carry willow branches instead of palms, even though in Johannesburg there is a palm tree in the church garden.

As we go in procession around the church, we sing the Troparion for Palm Sunday

By raising Lazarus from the dead before Thy passion

By raising Lazarus from the dead before Thy passion

Thou didst confirm the universal resurrection, O Christ God

Like the children with the palms of victory

We cry out to Thee, O Vanquisher of death

Hosanna in the highest!

Blessed is He who comes in the Name of the Lord!

And

When we were buried with Thee in baptism, O Christ God

we were made worthy of eternal life by Thy resurrection!

Now we praise Thee and sing:

Hosanna in the highest!

Blessed is He who comes in the Name of the Lord!

And one of the other hymns explains the meaning of the feast:

O gracious Lord, who ridest upon the cherubim,

who are praised by the seraphim,

now Thou dost ride like David on the foal of an ass.

The children sing hy7mns worthy of God,

while the priests and scribes blaspheme against Thee

By riding an untamed cols, Thou has prefigured the salvation of the Gentiles

those wild beasts, who will be brought from unbelief to fraith!

Glory to Tee, O merciful Christ

Our King and the lover of man.

Afterwards we went to bless a new small meeting room that had been added to the hall. The hall is far to big for small meetings.

Even the teddy got a bell, though some might doubt whether he was a logical sheep

The branches are supposed to be taken home and put above the door of one’s house.

This year Palm Sunday fell on 27 April, which is Freedom Day, and we celebrated the 19th anniversary of our first democratic elections in South Africa. Nineteen years ago South Africa came forth from the tomb like Lazarus. Let’s hope and pray that we don’t creep back there.

April 18, 2013

Click “Like” if you know someone who has cancer

An increasing number of my Facebook friends seem to be falling for “Like” scams, and I’ve probably done so myself. The trouble is, it’s increasingly different to tell the genuine from the false on Facebook, because much of the false stuff is propagated by friends.

Some of the scams are easy to tell, as this article points out:

Pro tip: If you do see a post about sick kids with rare cancer who lost all their family to a horrible house fire and if you don’t like it then 100 more children will get cancer from terrorists – it’s not real. Don’t click on it.

via All About Those Facebook ‘Like’ Scam Posts | Daylan Does.

– yes, go ahead and read the article, it’s worth reading, even if the author does make a killing out of all the “likes” it gets.

At least one of my Facebook friends has evidently fallen for the “This is my sister Mallory” scam, but, as the site referred to above points out

At least one of my Facebook friends has evidently fallen for the “This is my sister Mallory” scam, but, as the site referred to above points out

This post stated that someones ‘sister’ Mallory has down syndrome & doesn’t think she’s beautiful. It then asked for ‘likes’ it to show her she is.

The REAL story about this little girl is something much different: Read about it here

Or did you perhaps fall for this one?

Or did you fall for this one, perhaps?

Why on earth should anyone click “like” if they had one of those?

Why on earth should anyone click “like” if they had one of those?

Has anyone who ever clicked “Like” on any of those stupid scams ever stopped to think about that?

Yes, we did have one, and I didn’t like it because my mother falsely accused me of breaking it when I was a kid and threw a temper tantrum the like of which I had never seen before, and nearly made me run away from home. But hey, 265,594 sheep can’t be wrong, can they?

And I remember greengrocer’s and their apostrophe’s too.

And then there’s this one:

I commented on that one in Facebook, pointing out that it was a scam, but of course the scammers don’t mind that — it’s all grist to their mill. As someone once said somewhere, there is no such thing as bad publicity. It doesn’t matter what comment you type, good or bad, each one adds to the value of the page when they sell it. That’s why they ask you to type meaningless words in comments to see what happens, and of course nothing happens, except that their comments counter clicks up another sucker. Perhaps people expect something to happen, like when you type “Do a” in a Google search box (go on, try it), but Facebook isn’t Google, and the scammers don’t seem to be as active on Google +… yet.

There are also the ones that say things like “95% of people get this wrong”, and the ones that have a bunch of letters in a square and ask you to type the first word you can see (yes, I fell for that one too).

Here are some more articles on the topic:

Budge: Facing up to Facebook scams.

You ‘like’, but are you being scammed?.

So how do you avoid the scams?

By being sparing in what you like, and in what you share.

Sometimes it is hard to tell, but if the sentiment is general and obvious, like “Click like if you have a nice daughter” or “Click like if you loved your mother”, then it is not only a scam, but a waste of space.

If the sentiment is specific and personal, then it’s probably OK. If a photo is their own work, and you like it, then by all means say so, but if it is a stock photo from somewhere else, with a trite sentiment superimposed, then it’s better to ignore it. If it points to a newspaper article, or a blog post, especially one that your friends themselves have written, then it is not likely that they are tallying up their “likes” or “shares” in order to sell a page. I don’t even mind the shameless self-promotion of my friends who are touting their books or short stories. If I’ve read them and like them, I’ll click like (yes, Fr Michael Lapsley, that means you, and I’ve even touted your book on my blog!)

So remember…