Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 64

November 22, 2012

Becoming Orthodox: the actual theological problem

I couple of weeks ago I wrote about the 25th anniversary of our family being received into the Orthodox Church, and mentioned some of the problems I had seen in Western theology which seemed not to exist in Orthodox theology.

One commenter asked: do you articulate what the actual theological problem was?

And my reply was that the problem was the tendency to argue about the gospel rather than proclaiming it… in Western Christianity I felt caught between those who wanted to update the gospel on the one hand, and those who wanted to defend it on the other.

I said that perhaps that deserved a blog post of its own, and this is that post. Actually it probably needs a whole series of posts, but this will have to do for now.

As I said in the previous post, there were two things that sparked my initial interest in Orthodox theology: attending Holy Week and Easter services at St Sergius Institute in Paris, and reading and re-reading the catechetical address of St John Chrysostom, which was read there, in terms of which I interpreted the whole experience. And secondly, reading a book by Father Alexander Schmemann, The world as sacrament, which articulated very clearly the dissatisfaction I felt with Western theology, and presented the Orthodox alternative.

To understand this, however, one needs to go back to the 1960s, when there was a theological ferment in the Western world. To explain it, I will quote some contemporary documents that influenced me, and try to show how they linked together, in my mind at least. That will make this post rather long, and it may need to spill over into some other posts.

There was liturgical reform, in which various liturgical reformers (mostly Anglican and Roman Catholic) were trying to show that that worship was something done by a living Christian community, and not something done to a group of religious consumers.

There were dangers in this. Some of the dangers, from a Roman Catholic viewpoint, have been pointed out here On liturgy, ritual and false choices | A vow of conversation. An Anglican slant on it comes from John Davies, in a paper read to an Anglican student conference at Modderpoort in the Free State in 1961:

…the Communion is our best example of the nature of God, if it is taught and done evangelically. God is “I will be present as which I will be present” – not by man’s conjurings (which is what the doctrine of transubstantiation seems to lead to) nor just because man’s feelings cause him to be there (receptionism) but by his own initiative and covenant. The Communion, like Baptism, is not really a religious rite at all, it is God’s activity, not man’s. But does it look like it? Does the way we usually do the Eucharist look like anything more than a rather optimistic attempt by man to do something to God and to himself? And the same with Baptism — a private affair, when everyone else has gone home, or an inconvenient afterthought slipped into the “ordinary service”. The Mass a jumble of prayers said and things waved by a queerly-dressed Sundays-only character at a God who lives in the East wall — is this God in action? Yet these are the evangelical sacraments. The sort of thing suggested by contemporary liturgical reformers can easily become just another religious trick to gratify our cleverness, but at least it is trying to let the Mass speak.[1]

In the event, some of the things done by contemporary liturgical reformers did tend to become religious tricks. In some ways they threw out the baby with the bathwater. If the old rites did not show clearly enough that the church was a Christian community meeting God, in the new rites often both God and community were absent, and only religion remained.

An important point here is religion. The statement that “Christianity is not a religion” has been turned into something of an ideological cliche by some Western Evangelical Christians, who tend to use it as a slogan without explanation, but back in the 1960s there was, among Western Christians, serious discussion about Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s call for “religionless Christianity” and what it meant.

I soon discovered, when I went to the UK for postgraduate study in theology, that Bonhoeffer’s call was interpreted very differently in England from the way in which we had interpreted it in South Africa. John Davies had said that the title of his paper should rather have been God versus religion: it is all about God’s initiative, not man’s:

In Christ we have the culmination of the purpose of God, the most complete example of God’s initiative, pictured in the parable of the lost sheep – the shepherd takes positive action and searches for and claims the lost one. Religion is man’s search for God — Christ is God’s search for man, and man doesn’t care overmuch about being searched for. Being asked to perform a religious act is one thing, following the Son of God is another, and the encounter between the Son of God and Peter gives a good example right at the start of the gospel — Peter’s reaction is “Get away from me” (Luke 5:8). Religion attracts — Christ offends, and goes on offending; on the cross, in loneliness, Christ bore the penalty of the offensiveness of God, when God took the offensive. Gesthemane, and the cry of dereliction (Mark 14:32 ff; 15:34), are the most completely self-authenticating points in the gospel, for no one who wanted to invent a new religion could possibly have devised them, and they show the cost of religion to God, for it was religion that put Christ on the cross, religious authorities who couldn’t face the fact that the dream had come true, that the future had become present, who couldn’t face the judgement of God on a religion that divided man from man, righteous from sinner. Christ drew the line at no one, and paid the cost of doing so. If you draw the line at anyone, Christ will be on the far side, and not on yours. “Christ wants no honour for himself as long as our brother is dishonoured”.

In Britain, however, theologians were debating the nature of God. “Our image of God must go”, trumpeted one newpaper headline, describing the latest controversial book by an Anglican bishop. They didn’t want a religionless Christianity, they seemed to be more interested in a godless religion.

After two years of this, I was preparing for my final exam in Christian doctrine. It was conventional wisdom that the way to guarantee a pass was to read the magic book. In this case the magic book was Doctrines of the creed by Oliver Quicke, who happened to be the immediate predecessor of our professor of dogmatic theology at Durham University.

In the end I opted to read another book, a scathing indictment of Western academic theology and its exponents, Include me out: confessions of an ecclesiastical coward, by Colin Morris. Colin Morris had been a Methodist missionary in Zambia, and was moved to write his book when a Zambian dropped dead outside his front door. He had died of starvation. Among other things Morris wrote:

That phrase Revolutionary Christianity is fashionable. But what it describes is more often a way of talking than a way of walking. It is revolution at the level of argument rather than action. We take daring liberties with the Christianity of the Creeds and the traditional ideas about God. We go into the fray armed to rend an Altizer or Woolwich apart or defend them to the death. We sup the heady wine of controversy and nail our colours to the mast — mixing our metaphors in the excitement! The Church, we cry, is in ferment. She has bestirred herself out of her defensive positions and is on the march! And so she is — on the march to the nearest bookshop or theological lecture room or avant garde church to expose herself to the latest hail of verbal or paper missiles. This is not revolution. It has more in common with the frenzied scratching of a dog to rid itself of fleas than an epic march on the Bastille or the Winter Palace. Revolutionary Christianity is so uncomplicated in comparison that it is almost embarassing to have to put it into words. It is simply doing costly things for Jesus’ sake.

And in another place Morris wrote:

My grandstand view of the martyrdom of the Church in the Congo Counter-revolution taught me to distrust those conventional labels we pin on our fellow Christians. Over three hundred missionaries, mostly Roman Catholics and extreme fundamentalists, were killed. They not only bled the same way but whether they died clutching crucifixes or Scofield Reference Bibles they died for the same reason and the same Lord. When the chips were down in that tragic mess, men and women stood revealed for what they were, their theological labels abandoned with the rest of their possessions. Some theological radicals, fond of booming about relevance and involvement were not to be found. Their presence was urgently needed elsewhere. It was often Bible-punching conservatives who believed literally in Adam and Eve and damned drinkers and smokers and swearers to hell who stood up to be counted. Your theology, fancy or plain, is what you are when the talking stops and the action starts.

The first theological essay I had to write in England was on “Jesus and the demons”, and when I had finished reading it, the principal, who was a fan of the demythologising German theologian Rudolf Bultmann, said, “But you haven’t told me whether you think that demons exist or not.”

I didn’t know what to say. Having just come from South Africa where Liberals and the Security Police were engaged in a conflict whose roots reached down to depths where angels and demons were locked in mortal conflict, how could you explain this to the principal of an English college, comfortably seated in the armchair of his study, on a pleasant autumn day with the cathedral bells tinkling outisde? “And is there honey still for tea?” The term “armchair theologian” took on a whole new meaning. Don’t get me wrong; the principal was a nice bloke and I liked him, but when it came to theology, we came from different galaxies.

I didn’t know what to say, when he said I hadn’t told him whether or not I thought that demons existed, but Father Alexander Schmemann, the Orthodox theologian, articulated what I wanted to say, when describing the exorcisms and the blessing of the water that precede baptism in the Orthodox Church:

According to some modern interpreters of Christianity, ‘demonology’ belongs to an antiquated world view and cannot be taken seriously by the man who “uses electricity.” We cannot argue with them here. What we must affirm, what the Church has always affirmed, is that the use of electricity may be “demonic,” as in fact may be the use of anything and of life itself. That is, in other words, the experience of evil which we call demonic is not that of a mere absence of good, or, for that matter, of all sorts of existential alienations and anxieties. It is indeed the presence of a dark and irrational power. Hatred is not merely absence of love. It is certainly more than that, and we recognize its presence as an almost physical burden that we feel in ourselves when we hate. In our world in which normal and civilized men “used electricity” to exterminate six million human beings, in this world in which right now some ten million people are in concentration camps because they failed to understand the “only way to universal happiness,” in this world the demonic reality is not a myth (Schmemann 1973:69f).

I saw two opposed tendencies. On the one hand there were those who wanted to change the gospel to make it “relevant” to the world, and on the other those who wanted to defend the gospel against tendencies in the world (and in the church) that they thought threatened it. Schmemann describes the two tendencies as “spiritualist” and “activist”.

What life is both motivation, and the beginning and goal of Christian mission?

The existing answers follow two general patterns. There are those among us for whom life, when discussed in religious terms, means religious life. And this religious life is a world in itself, existing apart from the secular world and its life. It is the world of “spirituality,” and in our days it seems to gain more and more popularity. Even the airport bookstands are filled with anthologies of mystical writings. Basic Mysticism is the title we saw on one of them. Lost and confused in the noise, the rush and the frustrations of “life,” man easily accepts the invitation to enter into the inner sanctuary of his soul and to discover there another life, to enjoy a “spiritual banquet” amply supplied with spiritual food. This spiritual food will help him. It will help him to restore his peace of mind, to endure the other — the “secular” — life, to accept its tribulations, to lead a wholesome and more dedicated life, to “keep smiling” in a deep religious way. And thus mission consists here in converting people to this “spiritual” life, in making them religious.

There exists a great variety of emphases and even theologies within this general pattern, from the popular revival to the sophisticated interest in esoteric mystical doctrines. But the result is the same: “religious” life makes the secular one — the life of eating and drinking — irrelevant, deprives it of any real meaning save that of being an exercise in piety and patience. And the more spiritual life is the “religious banquet,” the more secular and material become the neon lighted signs EAT, DRINK that we see along our highways.

But there are those also, to whom the affirmation “for the life of the world” seems to mean naturally “for the better life of the world”. The “spiritualists” are counterbalanced by the activists. To be sure we are far today from the simple optimism and euphoria of the “Social Gospel.” All the implications of existentialism with its anxieties, of neo-Orthodoxy with its pessimistic and realistic view of history have been assimilated and given proper consideration. But the fundamental belief of Christianity as being first of all action has remained intact, and in fact has acquired a new strength. From this point of view Christianity has simply lost the world. And the world must be recovered. The Christian mission, therefore, is to catch up with the life that has gone astray. The “eating” and “drinking” man is taken quite seriously, almost too seriously. He constitutes virtually the exclusive object of Christian action, and we are constantly called to repent for having spent too much time in contemplation and adoration, in silence and liturgy, for not having dealt sufficiently with the social, political economic, racial and all other issues of real life. To books on mysticism and spirituality correspond books on “Religion and Life” (or Society, or Urbanism or Sex…). And yet the basic question remains unanswered: what is this life that we must regain for Christ, make Christian? What is, in other words, the ultimate end of all this doing and action? …

… Whether we “spiritualize” our life or “secularize” our religion, whether we invite men to a spiritual banquet or simply join them at the secular one, the real life of the world, for which we are told God gave his only-begotten Son, remains hopelessly beyond our religious grasp.

These two tendencies have been given different names. Some called them “conservatives” and “liberals”. Others called them “pietists” and “activists”. Some called them “evangelicals” and “ecumenicals”, and various other things as well.

I found myself caught between these two. Someone, I forget who, once said that both sides were “right in what they affirmed, but wrong in what they denied”. I could agree with that to a certain extent. I could agree with evangelicals on the importance of a verbal proclamation of the gospel; I could agree with the social activists on the need to change the unjust structures of society. What I could not agree with was the assumption by many on both sides that these goals were mutually exclusive.

Some people who had held that they were mutually exclusive did sometimes change their minds. John Stott, a well-known Anglican evangelical, came to acknowledge the importance of social action, and came up with a formula: Mission = Evangelism + Social Action.

But that was a bit like putting a bottle of wine and a bottle of furniture polish in the same packet at the supermarket, and carrying them out together. They were two separate things, in the same packet, but entirely unrelated to each other. Again, John Davies said it twenty years before John Stott came up with his formula:

I am seriously afraid that if the Church does not quickly act to shatter this impression of being a company for the organizing of religious activities, an association for the propagation of a localized mystique which attracts people who like dressing up but has no real impact on society, if it does not more effectively become what it is and possess its possessions, if it doesn’t more effectively reveal what happens in the Eucharist and live that action out in the broken world that Christ came and died to save, if it does not show that the `political’ utterances of its leaders are no personal crankiness, but arise directly out of the new birth in water and the Spirit and the four-fold action that takes place on every altar, then the people to whom we are sent will say more and more, `What have these people got that we can’t do ourselves?’, they will more and more count Christianity as merely a religion among religions, a superstition among superstitions, the Zionists will take all hearts and lives, and our so-called mission work will die of inanition – and that will be part of God’s judgement.

In saying this, I am not saying that Orthodox Christians have somehow managed to solve all these problems, and by their theological acumen have honed the church into an instrument to transform the world into a perfect image of the Kingdom of God. As St Paul put it, we have this treasure in earthen vessels — fragile, sometimes cracked and dirty, and utterly unworthy of the treasure we have been entrusted with.

The problem I found with much Western theology was that many wanted to throw away the treasure, and modernise the earthen vessels by exchanging them for polystyrene cups.[2]

_____

Notes and References

[1] Religion versus God, a paper read at the conference of the Anglican Students Federation of South Africa (ASF), July 1961.

[2] Many of the words and phrases I have used, even in the bits that are not directly quoted from others, are not original to me. I’ve tried to create an impression of a time, a Zeitgeist, and to show what drew me to Orthodoxy in the 1960s. Some of the tendencies I have described have persisted to the present, though with some changes too.

November 18, 2012

Bishops say “OXI” to neofascist Golden Dawn movement

In 1940 the Fascist dictator of Italy, Benito Mussolini, sent an ultimatum to Greece, demanding that they allow Italian troops to occupy Greece. The Greek response was a single word, OXI (“NO”).

This event as been commemorated since then by a public holiday, called OXI Day, and is observed by people of Greek origin around the world as well as by those in Greece itself.

This event as been commemorated since then by a public holiday, called OXI Day, and is observed by people of Greek origin around the world as well as by those in Greece itself.

The Greek resistance to Mussolini was the first Allied victory of the Second World War, and though Greece was eventually occupied by the Axis powers, the Italians required the assistance of German troops to do it, and it may be argued that this resistance delayed the German invasion of Russia, and meant that their invasion got bogged down in the autumn rains, and was halted by the Russian winter, and thus the Greek OXI changed the course of the war.

This post is not intended to be a lesson in military history , however. I am more concerned about the present, when Greeks are again needing to say NO to fascism. As one newspaper headline puts it: A Fascist party in full cry. Black-shirts smashing migrants’ homes. Swastikas on the streets. No, not Germany in the Thirties: Greece 2012.

This post is not intended to be a lesson in military history , however. I am more concerned about the present, when Greeks are again needing to say NO to fascism. As one newspaper headline puts it: A Fascist party in full cry. Black-shirts smashing migrants’ homes. Swastikas on the streets. No, not Germany in the Thirties: Greece 2012.

Or, as another newspaper reports, “Fascist gangs are turning Athens into a city of shifting front lines, seizing on crimes and local protests to promote their own movement, by claiming to be the defenders of recession ravaged Greece.”

The “recession-ravaged” epithet also recalls parallels with the rise of Nazism in Germany, which was struggling against austerity measures imposed by the victors in the First World War through the Treaty of Versailles. And other commentators have also pointed this out:

When German Chancellor Angela Merkel visited Athens last month, a few Greek Army reservists in fatigues greeted her with chants of “Get out, Nazis!” Like other Greeks, they are furious over the drastic budget cuts Germany and other eurozone countries are demanding in exchange for billions in bailout loans. The protesters compared the situation to Nazi Germany’s brutal occupation of Greece during World War II, when more than 400,000 Greeks died. But investigative journalist Dimitris Psarras hears other echoes of the past. “The economic crisis that Greece is facing today is similar to the one faced by Weimar Germany,” he says. “Just as Germany struggled to pay reparations imposed by the victors of World War I, Greece is now struggling to pay off giant debt racked up by its own corrupt political system.” Even Prime Minister Antonis Samaras has used the reference. In Weimar Germany, paramilitaries from the far right and far left fought in the streets. Germans struggled through head-spinning economic and political crises. Then, in 1933, after parliamentary elections that gave the Nazi Party the biggest share of the vote, Adolf Hitler came to power. Now Greece may have its own version of the Nazis, Psarras says, the Golden Dawn Party. He has researched the movement for more than two decades and just released a book, The Black Bible of Golden Dawn.

And what is the Church doing about all this?

Some might say that this is “politics” and that the Church should stay aloof from politics, but I can see distinct parallels with apartheid in South Africa, where after a lot of vaccilating and arguments about “religion and politics don’t mix” a number of Christian leaders did say publicly (in 1968, 20 years after the National Party came to power to promote apartheid) that the apartheid ideology was worse than a heresy; it was a false gospel, a pseudogospel of salvation by race rather than grace. Extreme nationalism, and the exaltation of race or ethnicity against all other values, is a form of idolatry.

There have been disturbing reports that some priests are supporting Golden Dawn, and thus leading their flock astray, but many bishops have been true to the faith. That is why we pray at every Divine Liturgy that God will “grant them for Thy Holy Churches in peace, safety, honour, health and length of days, rightly to define the Word of Thy Truth.”

The fullest and most comprehensive statement that I have seen so far is from The Holy Eparchial Synod of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, which issued a communiqué which included the following resounding OXI:

Statement of the Holy Eparchial Synod

of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

The Holy Eparchial Synod of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America in its Fall 2012 session expresses once again its deep concern over extremist language used in all spheres of public and private life. We exhort all the people with the admonition of the Holy Apostle Paul: Let your speech always be with grace, seasoned with salt, that you may know how you ought to answer each one (Colossians 4:6). We deplore the use of any racist, xenophobic, fascistic, hateful speech, imagery and behavior. Noting that the one of the great gifts of living in a democracy is the right to free speech, we nevertheless commend responsibility, civility, and indeed love in choosing our words and modes of expression. The people of Greece said “NO” to fascism in World War II and consequently suffered tremendously under the Nazi occupation. We call upon all people to say “NO” to the hatefulness of all forms of totalitarianism and embrace the true philanthropy and philoxenia (love of the stranger) that is the message of the Gospel. As a leader in Interfaith and Inter-Cultural Dialogue, the Greek Orthodox Church, by the grace of God, prays and works for peace, respect, and reconciliation among all people.

It’s time for Orthodox Greeks to remember OXI Day and say

November 9, 2012

Augustine of Hippo and “legitimate” rape

A few weeks ago an American politician sparked a furore by speaking about “legitimate rape”.

“First of all, from what I understand from doctors [pregnancy from rape] is really rare. If it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down… I think there should be some punishment, but the punishment ought to be on the rapist and not attacking the child.” – Rep. Todd Akin (R-MO), on KTVI-TV, August 19, 2012

I don’t know whether he has explained what he meant. I find it difficult to imagine any circumstances in which rape could be regarded as “legitimate”. But it also sparked off a theological discussion on the interpretation of some things said by Augustine of Hippo ‘Let It Be Unto Me’: Akin, Rape, and the Early Church | (A)theologies | Religion Dispatches:

Virginia Burrus: As soon as I began hearing the news reports of Akin’s remarks, I was haunted by similarities with the thought of the late Roman theologian Augustine…

Augustine’s discussion at the very beginning of his famous work City of God of the rape of Lucretia, a traditional Roman tale that he revisits in the context of real or anticipated wartime rapes of women of the Christian community.

Lucretia was a Roman woman renowned for her extreme virtue, known to have killed herself after she was raped in an effort to restore her honor by making it clear that she in no way colluded with her rapist. That itself is sufficiently telling testimony to the burden that rape places on its victims! But Augustine—in one of his lowest moments—makes it worse. For what he does is essentially to blame the victim nonetheless, much as Akin seems to do. He suggests (while acknowledging that only Lucretia herself could have known this) that Lucretia must have been “so enticed by her own desire that she consented to the act” (City of God 1:19). And in this she is, in Augustine’s eyes, condemned.

The theological point here is whether this is fair to Augustine.

Some have pointed out that it isn’t, and that the last thing that Augustine does, or wants to do, is “blame the victim”.

What Augustine Really Said about Rape – Lincoln A. Mullen:

So why then does Augustine bring up Lucretia? Lucretia is an example of a classical Roman woman who both was raped and committed suicide, and thus she is a locus classicus for both Christians and pagans. Professor Burrus writes that Augustine ‘suggests (while acknowledging that only Lucretia herself could have known this) that Lucretia must have been “so enticed by her own desire that she consented to the act’. But Professor Burrus has inexplicably left off the question mark from Augustine’s rhetorical question. What Augustine really says is this: ‘What shall we call her? An adulteress, or chaste? There is no question which she was. Not more happily than truly did a declaimer say of this sad occurrence: “Here was a marvel: there were two, and only one committed adultery.” Most forcibly and truly spoken’ (1.19). Indeed, Augustine is unequivocal in his claim that Lucretia bore no blame whatsoever for the rape.

But Augustine still has to deal with the question of suicide. So Augustine finds fault with Lucretia for committing suicide, not for being raped. In the passage that Professor Burrus discusses, Augustine is a rhetor arguing through every hypothetical situation. If Lucretia did not consent to the rape, Augustine says, then she should not have committed suicide and killed an innocent person. Even if (for the sake of argument) Lucretia did consent to the rape, to kill a person guilty of adultery is not justified. The language of chapter 19 makes it obvious that Augustine is discussing suicide, not rape. But to make it even more obvious, Augustine continues for the next eight chapters on the topic of suicide before he returns to the topic of rape (1.20–27).

Augustine elaborates on Lucretia’s motivations. He makes it plain that Lucretia did not commit suicide because she was secretly guilty of consenting to her rape but because of ‘the overwhelming burden of her shame’ (1.19). The pagans argued that Christian women who were raped should also feel ashamed and commit suicide. But Augustine praises Christian women for not feeling ashamed: ‘Not such was the decision of the Christian women who suffered as she did, and yet survive. They declined to avenge upon themselves the guilt of others, and so add crimes of their own to those crimes in which they had no share. … Within their own souls, in the witness of their own conscience, they enjoy the glory of chastity.

There are wheels within wheels here.

Mullen points out that Burrus, in attempting to refute Akin, has misrepresented Augustine.

And it’s the last point that interests me. I don’t think Akin needs much refutation and the arguments used in the article quoted are unlikely to convince Akin’s supporters.

This illustrates a tendency among western theologians to misrepresent early Christian writers, and to portray them as saying things about modern problems thaat they did not actually say. Similar things have been said about St John Chrysostom and antisemitism, for example.

I can understand why the enemies of Christianity might want to do this. I find it more difficult to understand why Christian theologians would want to do so.

November 8, 2012

Twenty-five years ago we were received into the Orthodox Church

Twenty-five years ago today we were received into the Orthodox Church on the day of the Synaxis of the Archangel Michael and the Other Bodiless Powers.

After being received into the Orthodox Church by Fr Chrysostom Frank, 8 November 1987: (Back) Methodius (Stephen) Hayes, Fr Chrysostom Frank, Katherine (Val) Hayes. (Front) Julia (Bridget) Hayes, Nicholas (Simon) Hayes, Raphael (Jethro) Hayes

We were received into the Orthodox Church in Johannesburg on 8 November 1987 (Michaelmas) by Fr Chrysostom Frank who had recently returned from the USA to be chaplain of the Society of St Nicholas of Japan, a newly-established Orthodox mission society.

Synaxis of the Holy Archangel Michael and the other Bodiless Powers

At that time the Society was meeting at St Matthew’s Anglican Church Hall in Fairmount, Johannesburg, for Saturday Vespers and the Divine Liturgy on Sundays, and the Church of St Nicholas, which had its beginnings then, recently celebrated its own 25th anniversary.

Our road to Orthodoxy had been quite difficult, however.

I had first become interested in Orthodoxy when I was studying theology at St Chad’s College, Durham, England, and had the opportunity to attend a Seminar on Orthodox Theology for non-Orthodox theology students. It was held at the Chateau de Bossey in Switzerland, where we had a week of lectures, and then went by bus to Paris where we attended the Holy Week and Pascha Services at the St Sergius Institute in April 1968.

I was then Anglican, and the thing that got me hooked was the Easter Kiss. That was before the “kiss of peace” became fashionable in Anglican churches. At St Sergius the priest stood in front of the congregation and one of the other ministers kissed him with the greeting “Christ is risen” and the response “Indeed he is risen”, and the minister then stood on the priest’s right, and the next person greeted both of them, and so it went on until everyone had greeted everyone else. It took 45 minutes. And it was followed by the reading of the Paschal Homily of St John Chrysostom, which encapsulates the essence of the Gospel in less than one page of text.

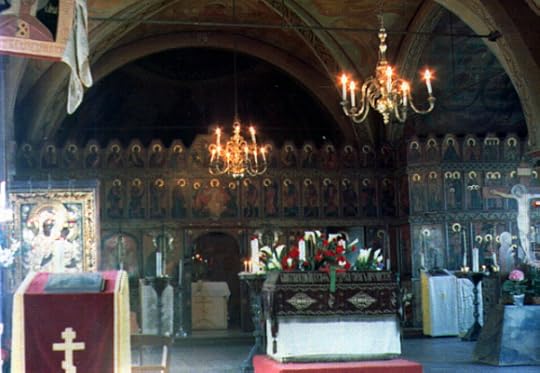

Holy Week at St Sergius in Paris, April 1968. The priest is Fr Alexander Kniazeff.

That whetted my interest in Orthodox theology, and I began to read books of Orthodox theology. One of the first was The world as sacrament by Fr Alexander Schmemann, later published in an expanded version as For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy by Alexander Schmemann

For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy by Alexander Schmemann

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

If there is one book that would reecommend to anyone wanting to know about the place of the Christian faith in the world we live in, this is it.

Back in the 1960s Western theologians were divided into those searching for the secular meaning of the gospel, and those who were seeking to respiritualise it. I found both equally rebarbative, and Schmemann articulated what I had been trying to say.

I returned to South Africa and remained an Anglican for another 15 years. I got involved in theological education, training self-supporting priests and deacons in the Anglican diocese of Zululand. Then I became Director of Mission and Evangelism in the Anglican Diocese of Pretoria, but that only made the theological problem more acute. An evangelist is one who proclaims the gospel, the good news of Jesus Christ. But in Western theology the tendency to argue about the gospel rather than proclaiming it seemed to be growing stronger. As St Paul said, in a somewhat different context, if the trumpet gives an uncertain sound, who will be prepared for the battle? (I Cor 14:8). It was becoming more and more apparent to me that the only place to find the orthodox theology that I believed in was in the Orthodox Church.

St Sergius Church in Paris, Holy Week 1968

I wrote a letter to Fr Alexander Schmemann, since he had written the books that had convinced me, to ask his advice, but he had died a year or two before, and so my letter was passed on to a South African student at St Vladimir’s Seminary, Jonathan Proctor (now a priest in St Paul, Minnesota). He told me there was an English-speaking parish in Melrose, Johannesburg, with an English-speaking priest, Fr Chrysostom Frank.

St Sergius, Paris. Procession at the cemetery, Good Friday 1986

We drove the 60 kilometres to the Sunday services, but could not afford to do so every Sunday, so on alternate Sundays we went to the Catholic Church in Queenswood, which was just 3 kilometres away, and was reputed to be one of the liveliest Catholic parishes in Pretoria, with lots of house churches and things like that. But though it was closer to home geographically, it felt less like home spiritually.

After a few weeks of this, we asked Fr Chrysostom what we should do to join the Orthodox Church. He said we should write a letter to the local bishop. So we did.

We waited for a reply from His Eminence Metropolitan Paul Lyngris, Archbishop of Johannesburg and Pretoria, but none came. Eventually Fr Chrysostom asked the bishop. Yes, he had received our letter, but there was a problem. A couple of months before we had arrived, another former Anglican priest had been received into the Orthodox Church in the same parish. He was Athanasius (David) Hamilton. The Archbishop was worried that the Anglicans might complain that the Orthodox was proselytising if we were received into the Orthodox Church, and so he had sent our letter to the Patriarch in Alexandria and asked for his advice. The Patriarch decided to refer it to the Holy Synod. This seemed a bit much. A synod of bishops from all over the continent discussing whether one family of five could join the Orthodox Church!

In the mean time, Fr Chrysostom went to study overseas, at the same St Vladimir’s Seminary, and the priest who replaced him could only speak Greek, and Pantanassa reverted to being a primarily Greek-speaking parish. Before the Holy Synod could meet to discuss our letter to ask if we could join the Orthodox Church, the Patriarch died, and so the Holy Synod was more concerned about arranging for the election of a new patriarch. What happened to our letter, we’ll probably never know. Perhaps in a century or three someone will find it mouldering in the archives in Alexandria.

In the mean time, Fr Chrysostom went to study overseas, at the same St Vladimir’s Seminary, and the priest who replaced him could only speak Greek, and Pantanassa reverted to being a primarily Greek-speaking parish. Before the Holy Synod could meet to discuss our letter to ask if we could join the Orthodox Church, the Patriarch died, and so the Holy Synod was more concerned about arranging for the election of a new patriarch. What happened to our letter, we’ll probably never know. Perhaps in a century or three someone will find it mouldering in the archives in Alexandria.

So for the next couple of years we were in a kind of ecclesiastical limbo, belonging nowhere. Many years latter Val and I confessed to each other that there had been times during those two years when we had contemplated going to the railway line over the road from our house and thowing ourselves under a passing train. Perhaps it was the holy guardian angels who protected us from that.

We still sometimes visited the local Roman Catholic Church of Christ the King in Queenswood. Once we asked the priest if we could talk to him, and he said “Phone me to make an appointment.”

The Holy Archangel Gabriel (Ikon by the hand of Julia Bridget Hayes)

One Sunday in Advent 1986 we went to Mass and they talked about “Shelter seeking” that evening, to which the congregation were invited, so Val went to ask the priest if we could go to it, even though we were not members, but we weren’t able to ask anything more about it because someone else started talking to him. We decided to go to it anyway. They had said that it would start at 7:30, but nothing seemed to happen, and there were just people hanging around outside the church talking. Then someone came and asked us if we were waiting for the Shelter Seeking, and when we said we were, they said the others had probably already left, and they would lead us, so we followed them to Sunnyside, and they were lost too, so we separated, and then found the house where they were doing the shelter seeking, but it was finished by the time we got there, and we were only in time for tea, so we never found out what shelter seeking actually was. At tea we got into conversation with someone, and thought perhaps that would be an “in” to this rather closed church community, but it turned out that it was his first time there too, and he had never found out what shelter seeking was either.

When the new Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and All Africa (Parthenios III) was elected a group of us in Johannesburg and Pretoria approached him for his blessing to start a mission society, with Fr Chrysostom as chaplain, and he gave his blessing. Fr John Meyendorff, the Dean of St Vladimir’s Seminary, impressed on Fr Chrysostom that one of the first things he should do, on returning to South Africa, was to receive us into the Orthodox Church, since we had been waiting so long. We had expected some kind of catechumenate and teaching, but Fr Chrysostom said that could wait till afterwards, and so after all the waiting, in the end it was quite a rush.

Fr Chrysostom said we could have new saints names, and gave us a book of saints so that could choose some. The book seemed rather odd. I was surprised to discover that Lord Byron, the English poet and libertine, was an Orthodox “saint”.

The Holy Archangel Michael [Ikon by the hand of Julia Bridget Hayes]

I picked Methodius, because I was still interested in mission and was studying missiology, and he was a missionary saint. Val chose Katherine, because she was close to her birthday. Bridget chose Julia of Carthage, because she was far away from her birthday — with her birthday in January being so close to Christmas, she wanted an excuse to celebrate some other time of the year. Simon chose St Nicholas of Myra (not of Japan), and Jethro chose St Raphael, whose day it happened to be when we were chrismated.When I was ordained as a deacon, however, the bishop gave me the name Stephen again, and that seemed appropriate, since he was one of the first deacons, and it seemed to be a sign that I should remain a deacon. When Bridget went to Greece to study, she found the name Julia very useful, since “Bridget” is a difficult name for Greeks (in Greek it looks something like “Mpridzet”). And a few years later, when Jethro was at school, his name Raphael was considered cool, since it belonged to one of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

But our Slava is St Michael and all the bodiless powers of heaven. The Slava is the feast of the patron saint of the family, when the first members of the family were baptised. Some years we have been able to celebrate it fully, with guests, and with a priest coming to the house. Other years, just by a few prayers. It seems to be a custom worth preserving and encouraging in Africa, where for many people ancestors are important.

Troparion – Tone 4

Commanders of the heavenly hosts,

we who are unworthy beseech you,

by your prayers encompass us beneath the wings of your immaterial glory,

and faithfully preserve us who fall down and cry to you:

“Deliver us from all harm, for you are the commanders of the powers on high!”

Kontakion – Tone 2

Commanders of God’s armies and ministers of the divine glory,

princes of the bodiless angels and guides of mankind,

ask for what is good for us, and for great mercy,

supreme commanders of the Bodiless Hosts.

November 6, 2012

A discursive journey into the highways and byways of English

By Hook Or By Crook: A Journey In Search Of English by David Crystal

By Hook Or By Crook: A Journey In Search Of English by David Crystal

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

A discursive linguistic and geographical ramble through Wales, and bits of England bordering on Wales, with occasional excursions to other parts of the world.

I really enjoyed it as a bit of bed-time reading on nights when I wasn’t too tired, which is why it took me a long time to get through it. But then I have worked as a proofreader and editor, and so there is a sense in which words are my business. Others might not have the same interest in such things.

I found some bits more interesting than others. One that was most fascinating to me was the story of John Bradburne, who was probably the most prolific poet in the English language. Shakespeare wrote about 84000 lines, Wordsworth about 54000, and Bradburne at least 170 000.

I had never heard of John Bradburne before, and pictured him as some kind of recluse, sitting in rural England, doing nothing else but writing poetry. Surely one would have no time for anything else?

But I was wrong.

He lived a varied and interesting life. He joined the Roman Catholic Church in 1947, spent some time with various religious orders, travelled to various countries, and eventually decided he wanted to be a hermit, and pray. He had three wishes: to to serve leprosy patients, to die a martyr, and to be buried in a Franciscan habit. He achieved all three, and on the twentieth anniversary of his death in 1999 some 15000 pilgrims visited the scene of his death at Mutemwa in Zimbabwe.

If you want more details, perhaps you should read the book, though you could probably Google for them.

That forms part of Crystal’s chapter on Southern African varieties of English, headed “the robot’s not working”. A nice pun, because “robot” is derived from the Slavic word for work, or worker.

I was a bit disappointed that Crystal did not even speculate on its origin, and to make up for his deficiency, I’ll put forward my own theory. For those who don’t know, “robot” is the South African term for what, in most other English-speaking countries, are called traffic lights. How did it get to be called that? My theory is that since, in the early days, the flow of traffic at intersections (British English = “junctions”) was controlled by policemen, when the policemen were replaced by a pole surmounted by coloured lights, some wag may have referred to it as a “robot policeman”, and the name stuck. After all, in Britain traffic-calming humps are sometimes called “sleeping policemen”. And when the robot’s not working, sometimes flesh-and-blood traffic cops step in to take over.

Crystal started off investigating Welsh accents when Welsh people were speaking English, but he covers a lot more than that. Some may find his discursiveness distracting, but I enjoyed it. He discusses Indian English, and American English, and European English, all of which affect spoken and written English.

If you find words, meanings, accents, names and their history, interesting, then you’ll probably enjoy this book.

October 31, 2012

Communication without community: American religion and the world

Fifty years ago Marshall McLuhan was saying that electronic media were turning the world into a global village. Television brought events like the Vietnam War and the Six-Day War into the homes of millions of people around the world. And that still happens, as the world learnt of the devastation caused hurricane Sandy in the north-eastern USA. But Marshall McLughans vision of globalisation didn’t quite come true as he envisaged it, and much of that commmunication is one way. When the USA catches cold, the whole world sneezes. I saw all sorts of expressions of sympathy for people in the USA from Facebook friends and others in other online forums, but while they had all heard of hurricane Sandy, most of them had never heard of typhoon Son Tinh, which killed almost as many people.

And so when blogger Macrina Walker wrote Bad Religion | A vow of conversation:

I recently read Ross Douthat’s Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics and thought that it might be an idea to say something about it. I hadn’t intended reading it as the nation referred to in the subtitle is the U.S.A. and I tend to get irritated at the way American concerns dominate so many conversations.

she immediately qualified it by adding this:

However, when a (South African) friend started posting quotes from it on Facebook, my interest was piqued and I realised that America has, after all, been exporting its bad religion around the world for a long time now. Or, perhaps more responsibly said, that the societal forces that give rise to developments in American religion are also present elsewhere, although the details, and even some of the trends, may vary. One of the key questions in my mind as I read the book was how what Douthat describes both does and does not relate to South Africa.

Another South African friend, Allan Anderson, who has spent the last couple of months in months in North America, writes on a similar topic on Facebook, from a somewhat closer vantage point:

TO ALL MY AMERICAN “CHRISTIAN” FRIENDS:

You don’t like Romney the Mormon pastor but you will vote for him coz you hate Obama the African American Christian. Please unfriend me first if you want to share anti-Obama posters on Facebook. This is supposed to be a social network and I sure don’t want to socialise with the venom I see here.

The phenomenon he describes is surely an instance of the “Bad religion” that Douthat writes about, and it is something that I too have noticed. There is very little to choose between most US presidential candidates. Obama showed that his “change you can believe in” was quite unbelievable. Under Obama’s administration the US government is still killing people in the Middle East and elsewhere, just it did under George Bush and Bill Clinton before him. Guantanamo Bay is still open. Where the candidates differ is in the nastiness of their supporters. Romney supporters are, on the whole, far, far nastier than Obama’s, at least to judge by their pronouncements in internet forums. And many of them claim to be Christian.

As viewed in online forums, American political campaigning seems to be all about vilifying the people you don’t like, rather than saying what you do like or want. Well, in that respect, South Africa is no different. Read any Sunday newspaper and it’s all about personalitires and nothing about policies. They’ll tell you who’s in and who’s out, but will tell you nothing about what they stand for and what their policies are. The difference is that I don’t see lots of people saying online that all true Christians should support Zuma or Malema or Zille or whoever.

I nevertheless think that Macrina’s key question is an important one — how does the bad religion that Douthat describes relate or not relate to South Africa, and other countries as well.

Back in the 1980s American bad religion swept into South Africa from the USA like a storm surge. If it wasn’t visitng speakers from the USA, it was audio and video tapes of their teachings, distributed by local churches in South Africa, and listened to by thousands on their car tape players in traffic jams, in study groups and the like. And, thougyh on a smaller scale than in the USA, a lot of this material was broadcast on radio and TV as well. It helped to shape a kind of generic Protestantism that is widespread today, not only in South Africa, but throughout the continent.

Yet the American “bad religion” that was imported was also modified. It was intrerpreted in terms of local culture and local theology. I noticed some of these differences at the recent Anglicans Ablaze conference in Johannesburg Anglicans Ablaze | Khanya:

…the biggest difference was perhaps that expressed by Bishop Graham Cray, from England, speaking on Transformed by the Holy Spirit, when he said that Christians are being called out of “consumer Christianity which exists to bless me, to a missional Christianity which is called to bless others”.

Anglicans Ablaze Conference, Johannesburg, October 2012

October 29, 2012

The elegance of the hedgehog

The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery

The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This ia a book about life seen through the eyes of the 54-year-old concierge (caretaker) of a block of flats in Paris, inhabited by rich people.

Renée grew up in a rural area, in a peasant family. She left school at 12, and her husband Lucien died some years previously, so she lives in her lodge with her television and her cat Leo (named after her favourite author, Tolstoy), and she fills her spare time reading. As a result she is probably more well-read and better informed than most of the residents of the flats, who, however, barely notice her.

One of the residents, however, has something in common with Renée. This is 12-year-old Paloma Josse, who feels oppressed by her parents and elder sister, and has a similar love of reading, and so is better informed in some ways than the rest of her family. She hates the idea of growing up to be like them, and so plans to commit suicide on her 13th birthday. In the mean time, she records her profound thoughts, and movements in the physical world that she observes.

In some ways, the book reminded me of Sophie’s world by Jostein Gaarder, which I read a few years ago, at least in the sense that the viewpoint characters, Renée and Paloma, express their philosophy of life.

I really enjoyed this book a lot, and I think it has a great deal to say about life and human relationships in South Africa, where the gap between rich and poor his as great, if not greater, than in France, and is probably still growing.

There is a sense in which it catches the essence of ubuntu, and it reminded me of an old man, Africa, who has been painting our fence for the last few weeks. He wanders around, asking to do odd jobs, and begging for a crust of bread if there is no work available. I imagine many people in the middle-class suburbs where he wanders regard him in much the same way as the residents of the posh Paris flats looked on Renée the caretaker, hardly seeing him at all.

Siliki Africa Mokgotlo

I thought I should write him a reference. He has done quite a good job of painting our 90 metres of fence. A while back he repaired and painted our roof. I looked it up and discovered that it was 12 years ago, and was quite shocked to see how long ago it was. Perhaps we’ll have another handyman job for him in 12 years’ time, but by then we’ll probably both be dead. So in the meantime, if anyone living in Tshwane has some painting or handyman-type jobs they need doing, perhaps you could think of Siliki Africa Mokgotlo, and give him a ring at 073-618-2288. No, he’s not as well-read as Renée the concierge, and won’t keep you entertained with philosophy and insights into literature, but Renée’s observations of the people who observe her probably apply equally to the rich people that Africa meets. Because of his age, he works slowly, but he is thorough.

October 27, 2012

Canadian bishop visits South Africa

Last week Bishop Georgije of Canada visited Johannesburg for the patronal festival of St Thomas’s Orthodox Church in Sunninghill, in the north of Johannesburg. He was accompanied by a priest, Fr Zlatibor Djurasevic, and a layman, Dr Goran Popovic.

It has become a regular custom for a bishop from the Holy Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church to visit St Thomas’s Church at the time of its patronal festival, and a different bishop comes each year. On arriving, Bishop Georgije was met by the parish priest, Fr Pantelejmon Jovanovic, other clergy of the Archdiocese of Johannesburg and Pretoria, and the local parishioners.

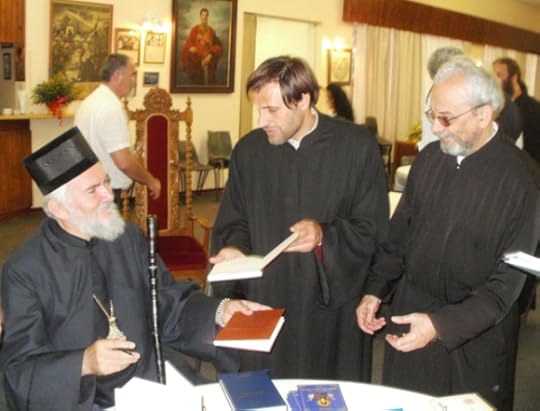

Bishop Georgije of Canada, Fr Pantelejmon Jovanovic (Rector of St Thomas’s Church), Fr Zlatibor Djurasevic of Canada, and Fr Athanasius Akunda (Rector of St Nicholas of Japan Church, Brixton) at Vespers

On Saturday evening, 20th October, Bishop Georgije served Vespers and Litiya, again with other clergy of the local Archdiocese who were able to attend, and then spoke in the hall about the publishing activities of the Serbian Diocese of Canada.

Bishop Georgije serving Litiya at St Thomas the Apostle Orthodox Church, with clergy from the Johannesburg Archdiocese, 20 Oct 2012

Among the other books on display was a quadrilingual book of the Divine Liturgy, in Greek, Slavonic, Serbian and English. Bishop Georgike presented signed copies of this to all the clergy who had served with him at Vespers. Fr Pantelejmon also had copies of the newly-printed Readers Service, in English and Zulu, which had been printed in Serbia. Five hundred copies of the Readers Service had been printed as a gift by the Eastern Orthodox Missionary Society of Father Daniel Sysoev. The Society was inspired by and formed in memory of Father Daniel, a missionary priest in Russia, who was murdered three years ago.

Bishop Georgije giving signed copies of the quadrilingual Liturgy book to Fr George Cocotas and Fr George Coconos of the Archdiocese of Johannesburg and Pretoria — three Georges.

On Sunday morning 21st October Bishop Georgije concelebrated the Divine Liturgy with the local bishop, Metropolitan Damaskinos, Archbishop of Johannesburg and Pretoria.

October 20, 2012

St Nicholas Church 25th anniversary celebrations

Last week we had a weekend of festivities to celebrate the 25th anniversary of St Nicholas Orthodox Church in Brixton, Johannesburg. I’ve already written something about the history of the church here.

The celebrations started with Vespers at 6:00 pm on Saturday 13 October, where there were also some visiting clergy from other parishes.

Clergy who served St Nicholas anniversary Vespers: Deacon Stephen Hayes, Fr Athanasius Akunda (the parish priest), Fr Pantelejmon Jovanovic and Fr Elias Palmos (photo by Jethro Hayes)

After Vespers we went to the Founders Grill in Florida for a celebratory dinner, and our choir member Harry Tambourlas and his jazz trio entertained us with music, as did some members of the parish who sang various songs.

Anniversary Dinner at the Founders Grill in Florida: good food, good music and good company

On Sunday morning His Eminence Metropolitan Damaskinos, Archbishop of Johannesburg and Pretoria, served a hierarchical Divine Liturgy, and tonsured several readers, and blessed the altar servers.

Archbishop Damaskinos distributing Antidoron at the end of the Divine Liturgy

October 9, 2012

St Nicholas Orthodox Church, Brixton: 25th anniversary

This week the Orthodox Church of St Nicholas of Japan in Brixton, Johannesburg, will be celebrating its 25th anniversary.

It held its first public service on 24th October 1987, though it was not then in Brixton, nor was it, at that stage, a parish. The service was Vespers, held in St Matthew’s Anglican Church Hall in Fairmount, Johannesburg, and it was arranged by the Society of St Nicholas of Japan, a mission society, which hoped to start several new parishes.

In March 1988 the Society moved to holding services in a chapel at St Martin’s-in-the-Veld Anglican Church in Dunkeld, and in 1990 we moved to the chapel at the Russian House in Yeoville, Johannesburg.

The chapel at the Russian House in Hunter Street, Yeoville, Johannesburg, 1990

The Russian House Chapel at least meant that we did not have to schlepp everything for the service out of a store room and back again afterwards, as we had had to do at St Martin’s, but it was too small for the growing congregation, which by this time had decided to form itself into a parish, also with St Nicholas of Japan as patron, and elected a parish council separate from the committee of the mission society.

The parish council set out to look for a more permanent meeting place, and eventually found one at 156 Fulham Road, Brixton. It was the Brixton Tabernacle, which had formerly belonged to the Full Gospel Church. After some alterations to make it suitable for Orthodox worship, we began holding services there in November 1990.

St Nicholas of Japan Orthodox Church, Brixton, in the early 1990s

At the time that the Society of St Nicholas started most Orthodox Churches in South Africa were “community” churches, that is to say they were established and run by ethnic communities (kinotites) and they functioned more or less as ethnic chaplaincies, using the language of the particular ethnic community, such as Greek, Serbian etc.

St Nicholas was intended to be a mission church, and multi-ethnic, with services mainly in English. St Nicholas of Japan was chosen as the patron saint because he was a Russian missionary who went to Japan, but started a Japanese Church, not a Russian one. So the aim of the society and the parish of St Nicholas was to be a South African Orthodox Church, which people of any ethnic background could join. And there was a steady stream of people joining the Orthodox Church at St Nicholas. Among those who joined in the early days were Sean Noel-Barham and Zwelinzima Nyathela, who were chrismated on 25 April 1992.

Chrismation of Sean Noel-Barham and Zwelinzima Nyathela by Fr Chrysostom, Holy Saturday, 1992

After being chrismated, they went in procession around the font and, since it was Holy Saturday, the Epitaphios.

The newly-illumined servants of God led by Fr Chrysostom in procession around the font and Epitaphios (funeral shroud of Christ)

The Church of St Nicholas has had four parish priests in the 25 years of its history:

Fr Chrysostom (Gary) Frank from the USA (1987-1996)

Fr Bertrand (Iakovos) Olechnowicz from the USA (1998-2001)

Fr Mircea (Mihai) Corpodean from Romania (2002-2008)

Fr Athanasius (Amos) Akunda from Kenya (2008-present)

In 1996 Fr Chrysostom left to join the Roman Catholic Church, and for the next year St Nicholas was without a permanent priest, and on many Sundays we had the Reader’s Service (Obednitsa, Typika), though priests from neighbouring parishes came to help with such services as the Presanctified Liturgy in Lent, and served the Divine Liturgy on some other days, though on Sundays they were busy in their own parishes. In many ways St Nicholas became stronger as a community in the year without a priest.

We celebrated Holy Week with the next-door parish of SS Cosmas & Damien in Sophiatown but Gustav Prinsloo was nevertheless baptised on Holy Saturday by Fr Alexandros Gianniris, who said he found St Nicholas’s music “addictive, like cigarettes”. We gave him a tape of the parish music disguised as a cigarette packet (complete with addiction warnings) as a farewell present when he left to become Bishop (now Archbishop) of Nigeria.

At the beginning of 1998 we got a new priest, Fr Bertrand Olechnowicz (later known as Fr Iakovos) from Pennyslvania in the USA. Sadly one of his first duties was to conduct the funeral of Gustav Prinsloo, who had been baptised nine months previously. He was killed in a car accident while going home from church one Sunday. After the funeral service in church at Brixton the congregation travelled 250km to Petrus Steyn in the Free State for the interment, and many people were so impressed by the funeral that that there were 11 baptisms the following Pascha.

Fr Iakovos Olechnowicz at the funeral of Gustav Prinsloo in Petrus Steyn, January 1998

Father Iakovos returned to the USA at the end of 2001 and the then Archbishop of Johannesburg and Pretoria (Metropolitan Seraphim), asked Fr Mihai Corpodean, who had come to serve the Romanian community in South Africa, to look after St Nicholas as well. That meant that many Romanians from Johannesburg joined in regularly, and for big occasions, like Christmas and Easter, some came from as far afield as Cape Town.

Fr Mihai also introduced some Romanian liturgical customs — I was ordained as deacon while he was in the parish, and learned the Romanian pattern of censing from him, or at least the Romanian modification of the Russian-American pattern established by Fr Chrysostom. Also, the Romanian version of the prayers at the Poskomide (Preparation Service) listed just about every possible way in which a person could die. I think nearly everyone was moved when he prayed, at the Great Entrance, “for those for whom no one is praying any more”.

Fr Mihai serving the Divine Liturgy at the Epitaphios on Holy Saturday

As a multi-ethnic parish St Nicholas has been rather eclectic in such things, drawing on customs from different parts of the Orthodox world. On Holy Thursday and Good Friday we have had the Greek custom of the bringing out of the cross, and the taking down from the cross, which doesn’t seem to be part of Russian practice. And at Pascha we have the Russian style Easter kiss, which many of the Greek parishes seem to neglect. We have adopted the Serbian custom of the Slava, which seems to fit in very well with the understanding of the importance of ancestors in many parts of Africa. And perhaps from these different strands, a truly African Orthodoxy can be woven.

Fr Mihai and his family left in 2008 to go to New Zealand. Fr Athanasius Akunda, who was then Deputy Dean of the Catechetical School in Yeoville, was asked to look after St Nicholas as well. Some of the students from the Catechetical School also attended the services, and after the School closed, some of the former students still join us occasionally.

Holy Saturday 2011, with Deacon Irenaeus, Fr Athanasius and Deacon Stephen

Father Athanasius was originally from Kenya, and introduced some customs from Kenya too, such as praying for students at the beginning of school and university terms. He also encouraged the parish youth to meet more regularly and be more active, and there are now people meeting in houses for Compline, and visiting and praying for the sick and bereaved.

Holy Saturday 2011. Fr Athanasius scatters bay leaves as the people sing “Arise O God, judge the earth, for to Thee belong all nations” (Photo by Jethro Hayes)

Father Athanasius has also taken teams of people from St Nicholas to mission congregations to help in teaching the Orthodox Christian faith.

Receive the light of Christ: Fr Athanasius passes on the light from the Paschal candle at Pascha (Photo: Jethro Hayes)

The light of Christ is not simply to be shared within the Church of St Nicholas, but is to be taken out into the world.

Receive the Light of Christ: the light is shared at Pascha (photo: Jethro Hayes)

In spite of being a small parish, St Nicholas has not only received ministry from four different parish priests who have come from elsewhere in the world, it has also raised up people from within its own ranks who have ministries within the church community and beyond it.

Deacon Irenaeus (Brian) MacDonald and his wife Cathy (photo: Jethro Hayes)

Deacon Irenaeus now serves in the Church of the Virgin Mary (Pantanassa), which was the “mother” church of St Nicholas. Cathy MacDonald works for Twilight Children, which tries to help street children. Father Kobus van der Riet serves in Eldorado Park and in other parishes in the diocese. Father Andrei Kashinsky is a parish priest in a small village in Russia. Olga d’Amico is now Sister Paisia, in a monastery at Serres in Northern Greece.

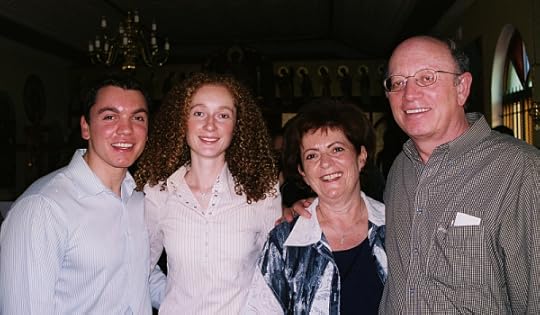

Fr Costa and Eleni Couvas, Maro and Costa Neocleous

Costa Couvas was ordained and is now studying in Greece; he and his wife Eleni live in Athens. Eleni’s parents, Maro and Costa Neocleous were active members of St Nicholas for many years, and now live in the USA.

Azar and Georgia Jammine

Azar Jammine has served as chairman of the parish council for many years, and also sings in the choir. His wife Georgia is the choir director, and keeps us all singing. Azar is also one of South Africa’s top economists, and that too is a ministry, though outside the walls of the temple.

Our parish priest, Father Athanasius Akunda

These are just a few of the people and events that have contributed to and made up the life of the Church of St Nicholas over the last 25 years.There is room for comments below if you think that anyone else deserves special mention.

We have experienced joy and sorrow; the joy of welcoming new people in Holy Baptism, and the sadness of bidding them farewell at funerals. But whether in joy or or in sorrow, we have received the light of Christ, and as our Lord Jesus Christ said, “Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your Father who is in heaven.” Or, as we sing at every Divine Liturgy: One is holy, one is Lord, Jesus Christ, to the glory of God the Father. Amen.

We will be celebrating with Vespers on Saturday 13 October at 6:00 pm, followed by a dinner party (at a cost of R280.00 per person).

On Sunday 14th October Archbishop Damaskinos will be joining us for the Divine Liturgy, and new Readers will be tonsured, and altar servers blessed. All welcome at both services, and if you can’t come, at least pray for us.