Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 61

April 11, 2013

Racism and Volkskerk: debate in the NGK

There’s an interesting debate going on in and about the Nederduits Gereformeerde Kerk (NGK), the largest of the three white Dutch Reformed Churches in South Africa. It won’t make much sense to you if you don’t read Afrikaans, but if you do you can follow it more closely by clicking on the links.

It started off when Professor Jonathan Jansen, of the University of the Free State, wrote a column headed “Break down this unrepentant…” in which he pointed out that the NGK is still largely a white institution, which clings to its whiteness.

To this, Neels Jackson responded that the NGK is not a white volkskerk, it only looks like one. In synodical decisions it has rejected apartheid and most of its dominees (clergy) and members also reject apartheid. It’s just that, with a few exceptions, most of those who come to the services are white, and to imply, as Jansen does, that that is the result of a deliberate policy, is at best a sign of ignorance, and at worst a sign of stubbornness or stupidity. That’s quite something to say about the man who has probably done more to transform education in South Africa than any other single person.

And blogger Cobus van Wyngaard (himself a dominee), questions whether one can make such a distinction between what something looks like and what it is. I’m paraphrasing here, but he is basically saying that if it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it is a duck.

Why should this discussion interest me, when I’m not a member of the NG Kerk? Why should I take such an interest in the internal debates of a Christian body whose theology and ecclesiology are so far removed from mine?

There are two main reasons.

The first reason is historical.

Until 1994 most members of the ruling party in South Africa were members of the NG Kerk, and so its theology profoundly influenced, and in turn was influenced by, the ideology of the government. What the NGK was thinking was not the concern of that denomination alone, but affected all Christians (and those of other religions or no religion) in South Africa as a whole.

One of the concepts that was central to the way that influence was felt was the concept of the Volkskerk.

The nineteenth-century German missiologist Gustav Warneck saw Christian mission primarily as “Christianisation of peoples”, so that they would have their own ethnic church, a Volkskerk. This model was adopted by the NGK in its own mission, so that it set up “daughter” churches to be the Volkskerk of the converts. This fitted in well with the apartheid policy of the National Party, which tried to impose the same model on other denominations, even when it clashed with their ecclesiology.

English-speaking Christians have a language problem here too, since the notion of a Volkskerk is difficult to translate into English. Literally it means “people’s church”, but the meaning of “people” was split in two in the twentieth century by the warring ideologies of Nazism and Communism. Hitler spent several pages of his book Mein Kampf discussing the meaning of Volk.

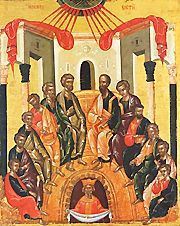

Dividing the nations (ethni) at Babel

In South Africa there was a bank, the Volkskas, the “people’s bank”. But the connotations of “people’s” in Volkskas were vastly different from those of the contemporary Moscow Narodny Bank — the Moscow People’s Bank. “Narod” is the Russian word that corresponds to “Volk” in Afrikaans and German. The distinction perhaps becomes clearer if one goes to Greece or Cyprus, where you can kind two kinds of “people’s banks” — a Laiki Trapeza and an Ethniki Trapeza. I think the missiological concept propagated by Gustav Warneck, and adopted by the NGK, was of a Volkskerk as an Ethniki Ekklesia rather than a Laiki Ekklesia.

And when people have been indoctrinated with this concept for a couple of generations or longer, it is going to take more than a couple of synodical decisions to get it out of their minds and thinking and conceptual universe. What is the theology and ecclesiology that you are going to replace it with? But that is not my problem, and it is not for me, as an outsider, to tell the NGK how to solve it.

And that leads to my second reason for being interested in the debate going on in the NGK, because the same debate is taking place, or needs to take place, in the Orthodox Church, which is also often seen, both by many of its members and by outsiders, as a Volkskerk.

People sometimes ask me what church I belong to, and when I say “the Orthodox Church”, they at first think I must be Jewish. Then when I try to explain, the light dawns, and they say, “Oh, you mean the Greek Orthodox Church“. And I try to explain further, and say no I mean the South African Orthodox Church, or rather the African Orthodox Church because the Church was planted in Africa by St Mark in the first century, in AD 42 or AD 62, depending on who you talk to.

Orthodoxy was indeed brought to South Africa by Greek immigrants, but we have Greek, Russian, Serbian, Romanian and Bulgarian parishes. And if I get that far in explaining it people then say “Oh, you mean you’re Russian Orthodox“. No, that’s not it either. I’m non-ethnic Orthodox. But when I go to a Greek parish, sometimes someone who is an immigrant from Greece will refer to me, born in South Africa, as a xenos, a foreigner.

Once a Tswana-speaking seminarian, who had been studying at the Orthodox Seminary in Nairobi, was being interviewed on the Greek radio station in Johannesburg, and the announcer asked him, “And what made you interested in our Greek culture?” He was gobsmacked, and didn’t know what to say. He knew nothing about Greek culture, he’d been studying Orthodox theology in Africa, among fellow-Africans from all over the continent. Greek culture didn’t enter into it.

Though Orthodox missiology has probably never been influenced by Gustav Warneck, there is, however, something in it that resembles the Volkskerk — not in the manner that I have just described, but Orthodox missionaries did try to plant local churches. St Nicholas of Japan, a Russian missionary, went to Japan in 1861, and he aimed to plant a Japanese Church, not a Russian one. Thus there are various “ethnic” in the sense of “national” Orthodox churches – Greek, Russian, Bulgarian etc. But there is also an essential ecclesiological difference. Though the Bulgarian Church, for example, was in a sense a “daughter” church of the Church of Constantinople, and eventually became autocephalous, meanintg choosing its own head, it was not a daughter church in the same sense as in the Dutch Reformed Churches, where the “daughter” churches were for black people and the “mother” church was for white people. But when Bulgarians went to Constantinople they didn’t always understand this. Some of them wanted to establish a Bulgarian ethnic church there, and a synod was called that denounced that as a heresy, which they called “phyletism” — that’s the Greek word for racism, in case anyone was wondering.

But Gustav Warneck was influenced in his thinking by German romanticism, which also gave rise to central European romantic nationalism. This was a largely secular movement, but it had a huge influence in central and eastern Europe and the Balkans. It contributed to the rise of Balkan nationalism, which in turn led to the struggles for independence of countries like Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Romania. The links with German romanticism were strengthened when most of the newly independent countries got German monarchs.

Thus in the predominantly Orthodox countries there was a mixture of Orth0dox theology with a secular romantic nationalism and some people confused the two. So you sometimes hear Greek people saying things like “Hellenism is Orthodoxy and Orthodoxy is Hellenism”. St Basil must be turning in his grave!

It was the same romantic nationalism that gave rise to Zionism, which exists in much the same relation to Judaism as Hellenism does to Greek Orthodoxy. I have dealt with this in more detail in an article on Nationalism, violence and reconciliation — so I’m just giving a very brief summary here.

It was the same romantic nationalism that contributed to the rise of Afrikaner nationalism in South Africa, and led to an analogous relationship between the Dutch Reformed Churches and the secular ideology. And that is why the discussion in the NGK interests me, because among us Orthodox too, though we may not be a Volkskerk sometimes it certainly looks like it.

And yet in a sense we are a Volkskerk too, both ethniki ekklesia and laiki ekklesia, for, as St Peter says (I Peter 2:9):

You are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation (ethnos agion), God’s own people (laos is peripisin), that you may declare the wonderful deeds of him who called you out of darkness into his marvellous light. Once you were no people (laos) but now you are God’s people (laos Theou); once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy.

But in this Volkskerk there is neither Jew nor Greek, neither Boer nor Brit, neither Bantu nor Bulgarian, neither Serb nor Sotho, and the only xenos is the devil himself.

So when we come to Pentecost, let us sing what we mean and mean what we sing when we sing:

So when we come to Pentecost, let us sing what we mean and mean what we sing when we sing:

When the most High came down and confused the tongues,

He divided the nations;

But when he distributed the tongues of fire

He called all to unity.

Therefore, with one voice, we glorify the All-holy Spirit!

April 9, 2013

Speaking ill of the dead: Margaret Thatcher and Hugo Chavez

Here is a very good article, which notes that many of those those saying we should not speak ill of Margaret Thatcher because she is dead did not show such restraint themselves on the death of Hugo Chavez. It also notes the fatuousness of US President Barack Obama’s calling her a great champion of freedom and liberty when she supported the apartheid regime in South Africa and the Pinochet regime in Chile and a few other dictators as well. Margaret Thatcher and misapplied death etiquette | Glenn Greenwald:

Whatever else may be true of her, Thatcher engaged in incredibly consequential acts that affected millions of people around the world. She played a key role not only in bringing about the first Gulf War but also using her influence to publicly advocate for the 2003 attack on Iraq. She denounced Nelson Mandela and his ANC as “terrorists”, something even David Cameron ultimately admitted was wrong. She was a steadfast friend to brutal tyrants such as Augusto Pinochet, Saddam Hussein and Indonesian dictator General Suharto (“One of our very best and most valuable friends”). And as my Guardian colleague Seumas Milne detailed last year, “across Britain Thatcher is still hated for the damage she inflicted – and for her political legacy of rampant inequality and greed, privatisation and social breakdown.”

and goes on to say

To demand that all of that be ignored in the face of one-sided requiems to her nobility and greatness is a bit bullying and tyrannical, not to mention warped. As David Wearing put it this morning in satirizing these speak-no-ill-of-the-deceased moralists: “People praising Thatcher’s legacy should show some respect for her victims. Tasteless.” Tellingly, few people have trouble understanding the need for balanced commentary when the political leaders disliked by the west pass away. Here, for instance, was what the Guardian reported upon the death last month of Hugo Chavez: “To the millions who detested him as a thug and charlatan, it will be occasion to bid, vocally or discreetly, good riddance.”

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher and Hugo Chavez actually had quite a lot in common, and perhaps that too needs to be recognised. Both were, in their own way, exponents of Realpolitik, and put their country’s national self-interest first. Above all else, they did not want their country to be pushed around by foreigners, whether those foreigners were offshore oil companies (in the case of Venezuela), or a jumped-up military junta in Argentina (in the case of Britain).

There were also significant differences, however. For Maggie Thatcher, the Britain she represented was the Britain of the rich, whose interests must take precedence over the rights of the poor. For Hugo Chavez, at least in his rhetoric, and sometimes in reality, the rights of the poor must take precedence.

Hugo Chavz

And I agree with the sentiment expressed by Mehdi Hasan, who tweeted (@mehdirhasan) “Like many lefties I loathed her policies but I can’t help but admire her conviction politics, her willingness to lead not follow.” And I would say exactly the same of Hugo Chavez too.

Both tended to support unpleasant dictators too uncritically — in Margaret Thatcher’s case Pinochet of Chile, and in Hugo Chavez’s case Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe.

Margaret Thatcher also supported the apartheid regime in South Africa, and the right-wing of her Conservative Party were fond of saying things like “Hang Mandela”. Nelson Mandela and Margaret Thatcher: the meeting that never was | World news | The Guardian:

The Conservative prime minister had dismissed the ANC as “a typical terrorist organisation” and refused to back sanctions against the apartheid government, pursuing instead a policy of “constructive engagement”. South Africa was then seen as a vital ally in stemming communist expansion.

Margaret Thatcher and Nelson Mandela meet in 1990

Though Margaret Thatcher didn’t have much time for the ANC, when the ANC came to power it wasted no time in applying her policies of privatisation, which was probably the greatest compliment it could have paid her.

I suggest that when the Gauteng freeways are turned into toll roads, as has been threatened for several years now, they should be officially renamed the Margaret Thatcher Highway, as that would be the most fitting monument to her policies, and the most outstanding example of how they have been applied by the ANC government in South Africa.

It’s ironic that, when the freeway between Johannesburg and Pretoria was first opened in the 1960s, it was named the Ben Schoeman Highway, after the the National Party Minister of Transport. That was before Maggie Thatcher, before the privatisation mania of the Reagan/Thatcher years, and the roads and railways were still state owned and state run. With the change in policy, it would really be most fitting to rename it “The Margaret Thatcher Highway” the day e-tolling begins.

April 3, 2013

Individualism, collectivism and communitarianism

When I was a teenager I read books that turned me into a convinced individualist.

Aldous Huxley’s Brave new world made a deep impression on me, and perhaps revived memories of a book I had read when I was about 7 or 8. It was about a society in which there were three kinds of people: square, round and triangular. One day the squares took over the government, and decreed that the proper shape of people was square, so they built a machine that would turn the round and triangular people into squares, and forced the round and triangular people into it to turn them into the proper shape.

The round and triangular people resented this, and had a revolution, where they seized control of the state and put the machine into reverse, to turn people into their proper shapes again.

Now, with a bit more historical understanding, I can recognise that the book was a bit of liberal indoctrination, a reaction to the totalitarianisms of left and right, communism and fascism, which so dominated the world of the 1940s.

But even though I recognise it as indoctrination, I remain indoctrinated. It set me on the path of liberalism, and I’ve been a liberal ever since. Reading Brave new world nine or ten years later simply confirmed it. Society likes to force people to conform to its dictates, and when society does that, individuals should resist.

This was perhaps a good preparation for university, where in Sociology I we learnt, from the then-fashionable American functionalist sociologists, that society was all, and that the purpose of all social institutions, including churches and schools, was to help individuals to “adjust” to society. It was a view I rejected, quite strongly. I was attracted to writers like Søren Kierkegaard, who wanted his tombstone to have the inscription “That Individual”. The English Department at Wits university also helped to undermine the Sociology Department by prescribing books like George Orwell’s 1984.

I read the Enlightenment philosophers, or at least the bits of them that supported my individualistic viewpoint.

My favourite Bible verse was Romans 12:2: Do not be conformed to this world but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that you may prove what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.

Attempts by society to make individuals conform to its norms and mores and folkways (those were terms used by sociologists in those days) were, in my view, to be resisted and rejected.

Then I read a few other books that made me have doubts about my rigid individualsm.

One was The roots of heaven by Romain Gary.

It was set in a French colony somewhere in Central or West Africa, and in that period African colonies were struggling for independence. The French were probably more influenced by Enlightenment rationalist values than the other colonial powers, and the Africans struggling for independence generally accepted those values. They just thought that they could embody them in society better without French paternalism. And the book concerns a few white eccentrics who question these values. One is embarked on a crusade to save the elephants from extinction, another thinks that African values (such as ubuntu) will be lost in the Gadarene rush to modernity, and hopes, when he dies, to be reincarnated as a tree.

It wasn’t a very good book, and when I tried to read it again a few years ago, I didn’t manage to finish it, but it did make me question the value of pure individualism, and see that there was some value in community.

Then someone sent me a copy of The Catholic Worker, which introduced me to Dorothy Day’s communitarianism, which somehow seemed more Christian than either collectivism or individualism. This was reinforced by reading a book called The primal vision, on Christian presence amid African religion, and described Christianity, as brought to much of Africa by Western missionaries, as a “classroom religion”, cerebral and intellectual, and out of touch with the real life of most African people.

So I passed through the most of the 1960s with an unresolved conflict between individual and community. Which took priority? Was there a happy medium? But if so, what could it be?

For me the conflict was resolved when I discovered Orthodox Christianity. Orthodox anthropology makes a distinction between the individual and the person, and a person is always a person in community. In that it is similar to the kind of African anthropology espoused by The roots of heaven and The primal vision, summed up in the Zulu proverb Umuntu ungumuntu ngabantu — a person is a person because of people. Feral children, raised by wolves, never actually become human persons.

All that I have written above is by way of introduction to the following article. The way in which Orthodox theology, and in particular Orthodox theological anthropology, solves the problem I had in the 1960s has been very well expressed in this article by Fr Gregory Jensen:

American Individualism and Orthodox Asceticism

By Rev. Gregory Jensen | April 1, 2013

He has written for an American context, but much of what he says can be applied, mutatis mutandis, to other settings as well.

March 29, 2013

Death of a blogger

I recently learned of the death of a blogging friend, Shaun P. Downey, alias Jams O’Donnell (hat-tip to Cherry Pie).

His blog The Poor Mouth has been in one of my blogrolls for many years, and of it he said ‘The title of this blog comes from a Gaelic expression -”putting on the poor mouth”-which means to exaggerate the direness of one’s situation in order to gain time or favour from creditors.’

He described himself as:

Born Bonaparte O’Coonassa in Corkadoragha where the the torrential rains are more torrential, the squalor more squalid, the hopelessness more utterly hopeless than they are anywhere else. Actually I’m Shaun Downey and I live in Romford which is probably worse (Romford, that is, not my name!)

He was keen on photography, and used his cats and his nephew as models, and some of his work is to be seen in his blog. He also commented on news stories, some of which may easily have been missed, like this one, which I reproduce here as a memorial of sorts, in case his blog is taken down (which I hope it isn’t).

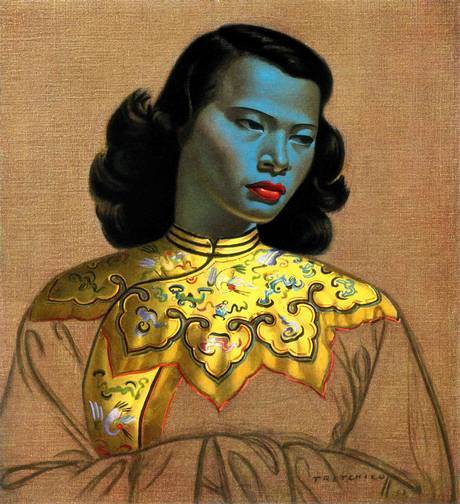

Tasteless painting fetches nearly £1m

The original painting of the Chinese Girl, thought to be the most reproduced print in the world, was sold for nearly £1 million yesterday. The work by Russian-born artist Vladimir Tretchikoff raised £982,050 – nearly double its expected price – as part of a sale of South African art at Bonhams auction house.

Millions of reproductions of the picture, also known as the Green Lady because of the unusual blue-green skin tone of the subject, have been sold since it was painted in the 1950s.

A Bonhams spokesman said: “It’s very exciting. Suddenly the market has decided they like what they can see with Tretchikoff.”

The Bonhams spokesman added: “It’s almost triple the £380,000 we sold his painting Lenka for last year. It shows he’s beginning to close in on the other major figures on the South African art landscape, Irma Stern – whose picture Arab Priest we previously sold for £3 million – and Pierneef.”

The identity of the Chinese Girl buyer was not known, but the painting will remain within Europe, the spokesman said.

No accounting for taste I suppose

The fact that his blog is still available serves as a memorial, and that is one reason that I disagree with the advice often given to bloggers to have a self-hosted blog. I’m reluctant to link to posts in self-hosted blogs, because the moment the blogger loses interest, or dies, or goes bankrupt, or stops paying the hosting fee for some other reason, the blog disappears and the link is broken. Of course free hosting sites can also disappear — Geocities and Bravenet are notorious examples, which broke thousands of links — but at least in the case of Geocities there were some generally successful rescue attempts.

The Poor Mouth was hosted by Blogger, and should remain visible as long as Blogger lasts, unless someone decides to take it down. So enjoy it while it lasts, and while it lasts, Shaun Downey’s poor mouth can still speak!

March 20, 2013

Who was the greatest missionary, Livingstone or Sechele?

When a blogging friend sent me a link to this article, I thought it was worth blogging about, but wasn’t sure whether to do so here, or in our family history blog. It is interesting both for missiological and family historical reasons, and perhaps for general historical reasons too. BBC News – The African chief converted to Christianity by Dr Livingstone:

According to the title of one biography, David Livingstone was “Africa’s Greatest Missionary”.

This is an interesting claim about the Lanarkshire-born man, considering that estimates of the number of people he converted in the course of his 30-year career vary between one and none.

The variation is because Livingstone himself wrote off his one convert as a backslider within months of his baptism.

The irony is that this one backslider has a much better claim than Livingstone to be Africa’s greatest missionary.

This man on whom Livingstone gave up became a preacher, a leader and a pioneer of adapting Christianity to African life – to the great annoyance of European missionaries.

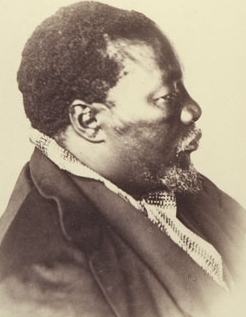

His name was Sechele, and he was the kgosi or chief of the Bakwena tribe, part of the Tswana people, in what is now Botswana.

Why family history?

Sechele (Sethele), Chief of the Bakwena

Well, though neither Livingstone nor Sechele were “family”, Sechele was, in a sense, a family friend. Though I do have Livingstone ancestors, I know of no connection between them and this David Livingstone. But my wife Val’s great great grandfather, Fred Green, and his older brother Charles were friends of Sechele, and perhaps acquaintances of Livingstone, and the story is quite an interesting one.

On their 1852 trip to Lake Ngami, Charles and Fred Green visited the Bakwena chief Setshele at Kolobeng, and left 50 cattle with him for their return journey, as they were planning to travel in country infested by tsetse fly. At some point on their journey they fell in with Samuel Edwards (son of a missionary), J.H Wilson (Setshele’s son-in-law) and Donald Campbell, with whom they explored the north shore of Lake Ngami, and travelled some way up the Taokhe River (Tabler 1973:18). They had travelled about 120 miles west of the Lake, where they reached elephant country. But it was also fly country, and the tsetse fly killed 34 horses and 50 head of cattle. They only shot six or eight elephants. On their return, however, they found that Boer raiders had made off with the cattle they had left with Setshele, and taken some two hundred women and nearly 1000 children into slavery (Schoeman 1988b:45). Livingstone likewise returned to find that his house had been plundered by the Boer raiders (Walker 1965:280).

Charles and Fred Green returned to Bloemfontein early in January 1853, accompanied by Setshele, and Edwards, who acted as Setchele’s interpreter, to lay a complaint with the British authorities there, in the person of their brother Henry Green, the British Resident. After deciding that a trip to the Cape Colony was unlikely to achieve very much, Charles Green held a collection for Setshele, and apparently took him home again (Schoeman 1988b:46), though some sources say that Setshele actually got as far as Cape Town before returning. The Greens were probably put off taking the matter further by a letter from Sir George Cathcart, Governor of the Cape Colony, to Henry Green, dated Grahamstown 23 January 1853:

Take great care what you are about with Sichely [sic] – remember that all alliances have been disclaimed with native tribes across the Vaal – do not give cause by your conduct to suppose that you in your capacity as H.M. Resident – are taking upon you to espouse his cause.

Your brothers I fear have done you an ill service by bringing their ill used friends to seek your support.

By the Sand River Convention of 1852 Britain had recognised the sovereign independence of the South African Republic (Transvaal), and in this letter Cathcart was saying, in effect, that what is now Botswana was outside the British “sphere of influence”, and within that of the Transvaal.

In early 1853 four of the Green brothers were in Bloemfontein. Henry the eldest, was 34, and was British Resident of the Orange River Sovereignty. Charles (28) and Fred (23) were birds of passage, using Bloemfontein as a base for their hunting trips to Lake Ngami. Arthur was 21, working as a clerk in Henry’s office. At this time Bloemfontein was still a small town of some seventy houses and thirteen shops. The civil and military establishment formed a closed social circle, and had little to do with the shopkeepers and other townspeople (Schoeman 1988b:11). The Green brothers (all of them unmarried) associated mainly with the army officers (their father, William Green, who was in the commissariat department of the British army, had been transferred to the Cape from Canada about 1846), and a few farmers who had retired from military service.

The British abandoned the Orange River Sovereignty in 1854, and it became the Orange Free State. One result of this was that hunters and traders like Fred and Charles Green no longer used Bloemfontein as a base, and the Transvaal government tried to stop traders going to Lake Ngami through their territory. From 1854, therefore, the Green brothers and others preferred to use the western route, through Walvis Bay, and moved their base to Damaraland (now part of Namibia), and so saw much less of Sechele.

So much for the family history and general history aspects of the article on Sechele.

There remain the missiological (or missional, or missionary) aspects of the story, which actually illustrates something much more general. When people in Southern Africa speak about “the missionaries”, and especially those of the 19th century, the picture that they usually have in their minds is of people like David Livingstone, and not people like Sechele.

This is true whether the people with the picture in their heads are secular historians who believe that the primary purpose of “the missionaries” was to introduce capitalism, or clergy of various denominations, who love to make unthinking dogmatic assertions about what “the missionaries” did. “The missionaries”, though plural in form, has actually become a kind of singular folkloric ogre.

Though the stereotyped “the missionaries” is a (usually male) foreigner from overseas (usually Europe or North America), in fact most Christian missionaries in southern Africa, in the 19th century and at other times, were far more like Sechele. It was through such missionaries, rather than through foreigners, that Christianity was spread in Africa.

The reason for the false impression is that the foreign missionaries got their financial support from their churches “back home”, and the people who gave money for their work wanted reports so that they could know that their money was being well spent. So there is a great deal of documentation of the work of the foreign missionaries, usually about what they themswelves were doing, in order to persuade their supporters to send them more money. The local missionaries (like Sechele) were far too busy preaching the gospel and were generally self-supporting. In fact their missionary methods bore a much closer resemblance to those of St Paul describe in the Acts of the Apostles than were those of the foreigners.

So in this respect, Sechele was not exceptional. He represents one of many thousands of people who promoted the spread of Christianity in Africa.

And it is these considerations that prompted me to try to set up a database of African Independent Churches and African church leaders, both local and foreign, male and female, ordained and lay, who played a part in the spread of Christianity in Africa. In part this has also been taken up by the Dictionary of African Christian Biography (DACB), though that consists mainly of completed publishable research, whereas the database collects little snippets of information, and fragments that are the building blocks of biography.

Bibliography

Schoeman, Karel. 1988. The Bloemfontein diary of Lieut W.J. St John. Cape Town: Human & Rosseau.

Tabler, Edward C. 1973. Pioneers of South West Africa and Ngamiland 1738-1880. Cape Town: Balkema.

March 16, 2013

The Apocalypse is coming!

The Apocalpyse is coming! The Apocalypse is coming!

Web sites like this one have been proclaiming it, with “Apocalypse” spelt with a capital letter, of course.

The 2012 Apocalypse is predicted by an intersection of Religions, Science, and Prophesies. Many Great Prophets, Religious Scriptures, and Scientific evidence point to a possible apocalyptic event happening in the year 2012.

We will explore the 2012 Apocalypse theories and predictions of who or what group may behind the inner workings of The war to end all wars? What acts of nature may cause the apocalypse 2012? What are the warning signs?

What do they think “apocalypse” means?

In English, The Apocalypse with a capital A is the title of the last book of the Christian Bible, also sometimes translated as “The Revelation”. That is, it is something that is revealed, uncovered, discovered.

In English, The Apocalypse with a capital A is the title of the last book of the Christian Bible, also sometimes translated as “The Revelation”. That is, it is something that is revealed, uncovered, discovered.

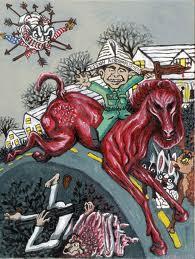

The ikon on the right refers to one particular passage from the Apocalypse, and there is a blog, Red Horse Down, that quotes that passage thus:

“He opened the second seal…another horse, fiery red, went out… it was granted to the one who sat on it to take peace from the earth, and that people should kill one another….” (Rev. 6:3) The “next big thing” in the news may well be war with Iran. Few want it, many warn against it and many more will suffer if it comes to pass. How can we forestall it? … “War is the unfolding of miscalculations.” (Barbara Tuchman)

“Unfolding” is another synonym for “apocalypse”, because when you unfold something you reveal what has been hidden.

What the Great Mayan Apocalypse of 2012 revealed, discovered, unfolded or made known was the endless gullibility of the human race.

Sometimes the idea lends itself to satire, as in this image. I’m not sure who the figure riding the horse is meant to represent, or even if it is anyone specific, but probably any of the warmongers of the last couple of decades would fit the bill, and there have been plenty of them.

Sometimes the idea lends itself to satire, as in this image. I’m not sure who the figure riding the horse is meant to represent, or even if it is anyone specific, but probably any of the warmongers of the last couple of decades would fit the bill, and there have been plenty of them.

Sometimes what has been revealed is a series of miscalculations. But sometimes it is stupidity or just plain malice.

It seems that the word “apocalypse” has a fascination for movie makers, and there have been dozens of films with the word “apocalypse” in their titles, from Apocalypse Now to Zombie Apocalypse. If that isn’t enough, there are also Cannibal Apocalypse, Meteor Apocalypse and, just when you thought it was safe to recharge your cell phone, Android Apocalypse. You are about to receive a very revealing phone call.

So when people speak of “apocalypse” nowadays, one can never be sure what they have in mind, but their conceptions have probably been shaped by film makers. I haven’t seen any of those films; perhaps I ought to, to discover what “apocalypse” means.

In the mean time, The Apocalypse is lurking there at the back of the Bible, waiting, waiting, waiting…

March 13, 2013

A Papal hat trick?

There seems to be intense speculation on who the next Pope of Rome will be, with bookies taking bets, and comments on Facebook and other social media sites.

But whoever he turns out to be, I suggest that there is only one possible choice for his name — Theodore II.

His Beatitude Theodoros II, Greek Orthodox Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa

That would make a papal hat trick, since we already have two popes with that name:

His Beatitude Theodoros II of Alexandria, is the current Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and All Africa. He was elected following the untimely death of Patriarch Petros VII in September 2004.

In the wake of the death of Patriarch Petros and other senior bishops in a helicopter crash in the Aegean Sea, Theodore was unanimously elected on October 9, 2004 by the Synod of the Alexandrian Throne as Patriarch. The enthronement ceremony took place at the Cathedral of Annunciation in Alexandria, on Sunday, October 24, 2004, in the presence of distinguished religious and civilian representatives and a great number of faithful (Wikipedia).

Pope Theodoros II (in Arabic: البابا تواضروس الثاني) is the 118th Coptic Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the See of St. Mark since he took office on November 18, 2012, a fortnight after being selected. in succession to his predecessor Shenouda III.

Pope Theodoros II (in Arabic: البابا تواضروس الثاني) is the 118th Coptic Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the See of St. Mark since he took office on November 18, 2012, a fortnight after being selected. in succession to his predecessor Shenouda III.

Pope Theodoros II was born Waǧīh Ṣubḥī Bāqī Sulaymān (وجيه صبحى باقى سليمان) on 4 November 1952 in the city of Mansoura in Egypt.[2] He studied at the University of Alexandria, where he received a degree in pharmacy in 1975.[5] After a few years of managing a state-owned pharmaceutical factory, he joined the Monastery of Saint Pishoy in Wadi Natrun to study theology for two years. He was ordained priest in 1989 (Wikipedia).

There, I think I’ve even beaten The Onion Dome in making this suggestion for ecumenical rapprochement.

March 8, 2013

Chalk and cheese: two novels by Barbara Vine

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I’ve just finished reading Asta’s Book for the second time. What prompted me to re-read it was my disappointment with The child’s child, which I read last week.

On the surface, they are the same kind of book, which prompted the comparison. It is a genre that has been made popular by Robert Goddard — a mystery in the past that has repercussions for people in the present. I found The child’s child unsatisfactory and unsatisfying. I had started if with the hope of finding something as good as Asta’s Book, but it wasn’t. And then I wondered whether Asta’s Book was as good as I remembered it? So I decided to re-read it and see.

I found it was even better than I remembered it, so I upped its rating from four stars to five. It had none of the faults that so disappointed me in The child’s child. There, the past and present stories were not integrated at all, and had only the most tenuous connection between them. The characters were cardboard cut-outs, and they seemed to change every chapter for no discernable reason.

In Asta’s book the characters were consistent. Yes, they changed over a lifetime, and of course they were not the same at age 75 as they were at 25, but despite the changes, there was a person there. The story in the past was well integrated with the one in the present, and the plot twists made sense.

The child’s child looked even worse, by contrast. It reads like the early drafts of the first chapters in a thesis submitted by one of my students, where I would point out some of the things that needed improvement, and would say, “It reads like notes for a thesis, not like a thesis. Each paragraph has a separate piece of information, culled from a source, but you have not shown how it links to what goes before and what follows after. There is no argumentation, no thread that leads to a conclusion.” And that is how The child’s child reads — like notes for a novel, rather than an actual novel. With the thesis the student would rewrite the chapter, and it would be an improvement, until eventually it was polished enough to submit for evaluation. But surely Ruth Rendell (writing as Barbara Vine) has an editor who can perform a similar function the the promoter of a thesis, and point out some of the weak links and plot holes.

I enjoyed Asta’s Book even more the second time around. In part its appeal is that it is not only a whodunit, dealing with a cold (very cold!) case of murder and a missing child, but it is also a mystery of family history, which is one of my own hobbies. I enjoy reading about family history mysteries in fiction because I enjoy trying to solve them in real life, well, perhaps not quite real life, because most of the people involved are dead.

Perhaps this is a continuation of my review of The child’s child, and perhaps a response of sorts to blogger Clarissa, whose response to it was similar to mine. She ascribes the weakness to the fact that Ruth Rendell/Barbara Vine to too old to write about young people any more. I wonder if it might be simply that she is too old. Asta in Asta’s book reaches the age where she no longer cares to write in her diary any more. It is only after her death that publishers become interested in the diary, and iot wasn’t written for publication. In real life, of course, Ruth Rendell is probably under pressure from publishers to produce “just one more” novel, but perhaps, in her 80s, like Asta she just doesn’t care any more, and a slapdash production like The child’s child is the result.

March 7, 2013

St Nicholas Church Patronal Festival

The Orthodox Church of St Nicholas of Japan in Brixton, Johannesburg, celebrated its patronal festival (Panigiri) on Sunday 3 March. It was a month late, but it was the first Sunday that our bishop, His Eminence Metropolitan Damaskinos, Archbishop of Johannesburg and Pretoria, could be with us.

Archbishop Damaskinos blessing the Slava Kolach (photo by Zinon Marinakos)

Since we are a multiethnic parish, we tend to incorporate cusoms from different branches of Orthodoxy, and one of them is the Serbian custom of the Slava. This is a kind of patronal feast for the whole family, held at home on the feast day of the patron saint of the family, usually the feast day of the saint on whose day the first members of that family were baptised. It works for a parish family too, and there is the blessing of the Slava Kolach a special loaf of bread (seen at the bottom left of the picture).

The turning of the Slava Kolach (photo by Zinon Marinakos)

After the bread is blessed it is turned around by members of the family (or in this case, the parish council), while the Song of Isaiah is sung.

O holy martyrs who fought the good fight and have received your crowns:

Entreat ye the Lord, that he will have mercy upon our souls.

Glory to Thee O Christ God,

the apostles’ boast, the martyrs’ joy,

whose preaching was the consubstantial Trinity.

Rejoice, O Isaiah!

A virgin is with child, and shall bear a son Emmanuel.

He is both God and man, and Orient is His name.

Magnifying him, we call the Virgin blessed.

O holy martyrs who fought the good fight and have received your crowns:

Entreat ye the Lord, that he will have mercy upon our souls.

Glory to Thee O Christ God,

the apostles’ boast, the martyrs’ joy,

whose preaching was the consubstantial Trinity.

The Church of St Nicholas of Japan, Brixton, Johannesburg, with Archbishop- Damaskinos (photo by Zinon Marinakos)

February 28, 2013

The child’s child — book review

The Child’s Child by Barbara Vine

The Child’s Child by Barbara Vine

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

At first I thought this was going to be one of the better books by Ruth Rendell writing as Barbara Vine, when a doctoral student writing a thesis on unmarried mothers in Victorian literature is given an unpublished novel on the same topic, but set in the 1920s and 1930s to read. At the beginning it showed promise of being something like Possession by A.S. Byatt, or, if not quite at that level, like a Robert Goddard novel, with a mystery in the past coming back to haunt people in the present. I kept reading, hoping for some sort of dénouement, which never came.

The past action is all in the unpublished novel, which, dealing with unmarried mothers and homosexuality, could not be published when it was written, as those were taboo topics in those days. The thesis about how the theme of unmarried mothers was dealt with in Victorial literature piqued my interest, as I had just read Oliver Twist, where that is one of the central themes.

But The child’s child is rather disappointing, as it comes in the form of a novella wrapped in a novelette, with very little connection between them. The novella is supposed to be based on the life of a great uncle of one of the characters in the wrapping story, but the connection is not made clear or explained, though one is led to expect that at some point it will be.

Barbara Vine has written better books in this genre in the past — one of them is Asta’s book, which I must perhaps re-read to see why I remember it as so much better than this one.