Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 58

October 9, 2013

The 1970s: strange days indeed

Strange Days Indeed: The Golden Age Of Paranoia by Francis Wheen

Strange Days Indeed: The Golden Age Of Paranoia by Francis Wheen

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

This book is about the 1970s as you probably don’t remember them.

A quick glance at the cover and at the blurb gives the impression that it is a kind of cultural history of an era. For Francis Wheen the Seventies began existentially when he decided to drop out. As he describes it:

With my rucksack and guitar in hand, I came to London on 27 December 1973 brimming with the ambition and optimism of the Sixties — a dream of change, a sense of limitless possibility — only to find the Seventies enveloping the city like a pea-souper.

In another place he is more explcit:, when discussing when the Sixties ended and the seventies began:

So it goes for most of us as we try to reconcile our private histories with a public narrative. Philip Larkin, recording the start of free love in 1963, lamented that ‘this was rather late for me.’ For me, alas, it was rather too early. I came to the party a full decade later, on 27 December 1973, when I caught a train to London from suburban Kent, having left a note on the kitchen table advising my parents that I’d gone to join the alternative society and wouldn’t be back. An hour or so later, clutching my rucksack and guitar, I arrived at the ‘BIT Alternative Help and Information Centre,’ a hippy hangout on Westbourne Park Road which I’d often seen mentioned in the underground press. ‘Hi,’ I chirruped. ‘I’ve dropped out.’ I may even have babbled something about wanting to build the counter-culture. This boyish enthusiasm was met by groans from a furry freak slumped on the threadbare sofa. ‘Drop back in, man,’ he muttered through a dense foliage of beard. ‘You’re too late… It’s over.’ And so it was. The Prime Minister, Edward Heath, had declared a state of emergency in November, his fifth in just over three years…

The promise these passages (and he blurb on the cover) give of the reconciliation of private histories with public narrative is not fulfilled. We are not told whether or how Francis Wheen dropped back in, or how he spent the rest of the Seventies. He presumably survived, or he wouldn’t have written the book. So I was expecting a cultural history, but instead it was more of a political history, and the political history of the 1970s was laced with paranoia, at least according to Wheen.

So having established what the book is not, what is it?

It’s the public narrative turned inside out.

Those of us who lived through the Seventies remember some of the headlines, and some of the major events. But what Francis Wheen does is take us behind the scenes, backstage, as it were, to see the stage props, and the actors without their make up. What were the motives for the much publicised political decisions? What was Edward Heath really up to with his successive states of emergency? What was the story behind Watergate, or Nixon’s rapprochement with China, or the Allende coup in Chile? What was really going on with nihilistic terrorist groups like the Baader-Meinhof Gang, the Tupamaros urban guerrillas in Uruguay, or the Symbionese Liberation Army?

Wheen has trawled through the various memoirs, diaries, letters and papers published by people close to the seats of power, and revealed some of the conversations about and motives for some of the decisions that were announced in the press. These documents were not available at the time, and it is only now that the inside stories can be revealed. Books have been published, archives made available, and Wheen concludes that Nixon, Heath and most of the other world leaders at the time were barking mad and quite paranoid. The Seventies were the paranoid decade, and that paranoia was the decade’s major bequest to those who followed.

Most of us don’t have time to read those documents, and so Francis Wheen has done it for us and made a digest of it to save us the trouble.

The trouble is that his selection of events to record would not have been mine. The events that stood out for him were not those that stood out for me, even in the public narrative.

Living in South Africa we were only very vaguely aware of Britains “winter of discontent” and its “Who governs Britain?” election (Answer: Nobody).

The Yom Kippur War of 1973 (40th anniversary at time of writing, but Telkom alone knows when I’ll get to post this) made more of an impact. It meant the reopening of the Suez Canal, and within a few months I no longer looked out from my front door in Durban North on 30 or more ships in the roadstead waiting to enter Durban harbour, and one could walk on Durban’s beaches without the lumps of crude oil making them took like the aftermath of an explosion in a Marmite factory.

There were some consequences of the Yom Kippur War that Wheen does mention, though — reduced oil production, rising fuel prices, and fuel restrictions . The fuel restrictions (in South Africa) were announced in November 1973, with speed limits in towns of 50 km/h and on open roads of 80 km/h. On 30 November I was driving into town from Durban North along Umgeni Road — the traffic was preferable to the sleep-inducing boredom of driving on the freeway at 50 km/h. I stopped at a robot and an Indian guy in the car next to me shouted, “Have you filled your tank, petrol is going up to a Rand a gallon.” Several other people told me the same thing on that day. Rumours abounded, and queues at filling stations were long. Now I doubt if we’ll see the fuel price as low as a Rand a litre again. But back then we were suddenly aware that whether we used it quickly or slowly, oil had to come to an end some day. Someone somewhere said that if every adult male Indian used toilet paper, the world’s paper supply would be exhausted in two weeks. So yes, Wheen was right about that. The Seventies was a time of the feeling of an approaching disaster, of inflation and the imminent end of the world.

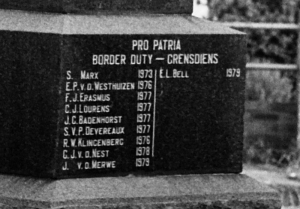

The Border War — a facet of the War Memorial in Vryheid

But in South Africa it was also the decade in which PW Botha and Magnus Malan decided to invade Angola (Wheen did not consult any diaries of their associates) and thus of what the South African public were led to believe was the “Border War”, though much of it took place a long way from any borders.

In the 1960s, under Vorster, South Africa had turned into a police state, but with the accession of P.W. Botha there was a military take-over, By the end of the Seventies the “Border War” had mutated into the “total onslaught” and South Africa came to be ruled by a military junta which lasted throughout the 1980s.

So in Wheen’s book I was expecting more of a cultural history of the 1970s, though there was not much of that. But the book did inspire me to think of how we do reconcile our private histories with public narratives, even if Wheen does not deliver on this.

In July 1968 I sat with a college friend, Alaistair Wyse, in Hyde Park in London, making paper flowers, which we handed to passers-by as we made them. It was our contribution to the hippie peace movement, and perhaps, for me, the end of the Sixties.

A few days later I returned to South Africa after two years of study in the UK. If the Seventies were the paranoid decade for Britain and the USA, South Africa was an early adopter, South Africa became a fully-fledged paranoid society ten years earlier when B.J. Vorster became Minister of Justice in 1961, and just about every year after that new repressive legislation was introduced. So when I arrived home the paranoid society of the 1970s was already in full swing. Safari suits, combs in socks, short back & sides and Gunston (a brand of Rhodesian cigarettes, smoked by whites in support of Ian Smith’s UDI).

There were some other features of 1970s culture that Wheen also does not touch upon. Like Jesus Freaks.

In 1970 I was living in a community that was a cross between a new monastic community and a hippie commune, though some of our visitors tended to treat it as a crash pad. We called ourselves the Community of St Simon the Zealot, and reading, many years later, the Security Police’s exegesis of the name, was itself a study in paranoia, though we knew that at the time. We just didn’t have proof.

The community eventually disintegrated, partly because of conflicting ideals, and partly because some of us were deported. But it was also interesting, a few years later in Durban North, to meet some Jesus Freaks from America, a colony of the Children of God, who seemed to be doing somewhat better than we had, and whose secret booklet, Revolution for Jesus: how to do it seemed a lot more practical than the little red book of the Thoughts of Chairman Mau. I still have a copy in the Dutch translation, which I might some day finish translating back into English, unless someone can find the original.

At about the same time there was the film Brother Sun, Sister Moon which was possibly the alternative ideal of the decade, though it got mangled in copyright wars or something. Perhaps that is symbolic, because the rest of the decade was a constant stream of disaster movies — The Poiseidon adventure, The towering inferno, The taking of Pelham 123, The Hindenberg and more. Perhaps it is significant that several of them had remakes about 20-30 years later. I wonder why? That in itself is perhaps a cultural fact worth pondering.

October 8, 2013

No phone or Internet access

We have had no phone or Internet access for 11 days, and Telkom alone knows when it will be working again. As a result I haven’t been able to update this blog or approve new comments. Blogging will resume as soon as Telkom permits.

I’m posting this from my wife’s office, where I came to renew my liberary books.

No Internet access or phone

I haven’t been able to update this blog (or any of our other blogs) or approve new comments, since our phone and ADSL line has not been working for 11 days and Telkom alone knows when it will be working again.

September 25, 2013

A new home for our web pages

We have found a new home for our web pages at http://www.khanya.org.za.

These pages were formerly hosted by Bravenet at http://hayesfam.bravehost.com, but they haven’t worked at all for over a year now, and all attempts to communicate with Bravenet to find out what the problem was failed, so I revived an old parked domain of khanya.org.za, and we are now moving our web pages to there.

So if you have any links to any of our web pages at hayesfam.bravehost.com, please change the links to http://www.khanya.org.za.

We started these web pages in 1996, hosted by Geocities, which was taken over by Yahoo! which was the kiss of death for Geocities, as it was for so many other things taken over by Yahoo! Long before Geocities actually folded it was becoming unreliable and thew web pages were inaccessible for months at a time, so we moved them to Bravenet, but then that started to go the same way.

It will take a while to get all the pages up and linked properly again, so please be patient if you find “404 File Not Found” errors. Just click on the back button and try something else. And once the links within the site are working again, we still have to update content and fix external links, as things tended to get a bit chaotic with the Bravenet problems.

To see what is supposed to be on the site or linked to it, see here: Steve Hayes links and contact information.

September 16, 2013

Syrian civil war: no good outcome?

The threat of a US bombing of Syria, which seemed imminent last week, has receded somewhat, with US acceptance of the Russian proposal for the dismantling of Syrian chemical weapons. Some have been talking as though war has been averted, but it has not. The civil war in Syria, which has been going on for two years or more, continues, only without the air support that the rebels were hoping for. They had already sent their US backers a list of targets they wanted bombed.

So the war continues, and it is difficult to see how there can be a good outcome.

To begin with, the rebels may have been fighting for freedom and democracy, and President Bashar al-Assad’s violent repression of peaceful demonstrations led to a violent backlash which has no escalated into civil war, in which other parties, whose aims are anything but democratic, have joined in. Perhaps the meeting of the US and Russia and the agreement to dismantle chemical weapons could lead to more meetings, and the parties in the Syrian conflict could be brought together, but then what? What kind of political process could take place? It would take a miracle to bring peace in such a situation.

In 1959 an Anglican priest, Werner Pelz, who had gone to the UK as a Jewish refugee grm Nazism, and then been interned as an enemy alien, wrote, “We are afraid of our problems because we fear that nothing short of a miracle can solve them, that nothing short of a miracle can save us. But we are never saved by anything short of a miracle” (W. Pelz, Irreligious reflections on the Christian Church).

So perhaps that is all we can do — pray for a miracle.

And perhaps something of a miracle has already occurred, in that the relentless drive of the political leaders of USA and the UK to add fuel to the fires of war in other parts of the world has apparently been halted. It may have been war-weariness that led the British parliament to vote against armed intervention, and to try to facilitate peace rather than more conflict. President Vladimir Putin of Russia may have gauged the mood of the American people better than the American president, and better than the Western media, which have, for the most part, been advocating war, and been impatient with anything that hindered the rush to war. What the Western warmongers have failed to provide is any convincing evidence that the fire is more comfortable than the frying pan.

So the avoiding of the escalation of the war to an international conflict is already a miracle of sorts.

So what can be done by those far from the conflict? What can Christians in other places do to help Syrian Christians?

Even when the warmongers have been halted, or at least slowed, there is the danger that peacemakers, in their eagerness to help, can be counterproductive, and kill with kindness rather than with bombs. The urge to “Do something”, and the anguished cry of “We can’t just stand by and do nothing” too often leads to cultural imperialism.

The best thing that Western Christians can do for Syrian Christians is to learn from them, and there is a lot to learn.

A couple of years ago a US publication Christianity Today carried an article “What’s in a Name? Christians in Southeast Asia debate their right to refer to God as Allah.” Muslims were urging governments to make it illegal for Christians to refer to God as Allah. In places like Syria, Arabic-speaking Christians have always referred to God as Allah, and this had spread to other languages, such as those of Southeast Asia, that had been influenced by Arabic.

Some of the comments that follow the article show the most appalling ignorance. Here are a few examples:

A christian should never refer to the God of Abraham, Issac, and Jacob as being Allah, because the two are clearly different. Every christian believer should uphold and stand firm on what the Word of God teaches; any comprimise [sic] is clearly and unequivically [sic] unacceptable.

Allah is NOT the God of the Bible. The author states “Few question whether Allah is the God of the Bible—to Malaysian Christians, Allah is simply the word for God.” He is right. Not enough question it. Just because Allah tranlates to god does not mean we are talking about the same God.

There are also several comments on the article that contradict these, so the ignorance and chauvinism are not universal. Nevertheless, people who despise Syrian Christians because they address God in Arabic or Aramaic rather than English are not likely to be able to help them.

I hope that some of the other contributions to this synchroblog will help people in other parts of the world to learn more about Syrian Christianity.

Kidnapped Syrian bishops: Metropolitan Boulous Yazigi and Metropolitan Mar Gregorios Yohanna Ibrahim

Syria is the home of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and all the East, and they trace their bishops back to St Peter. It was in Antioch that the disciples of Jesus were first called “Christians” (Acts 11:26), so it ill-behoves johnny-come-latelys to tell Syrian Christians that they use the “wrong” name for God.

It was from Antioch that the first Christian missionaries set out to take the gospel to Europe (Acts 13).

As a result of the viccistudes of war and politics in the nearly 2000 years since then, Antioch is now in Turkey, and the seat of the Patriarchate has moved from Antioch to Damascus in the present-day state of Syria.

So before rushing to “help”, it is advisable to learn and to pray. Pray especially for the missing bishops, who were abducted on 22 April 2013.

The mindless activism of the “we’ve got to do something” may make the activists feel good, but it is sometimes better to think before acting. Feeling that one has to do something because people are dying very often just leads to the killing of more people, as it did in Yugoslavia (1999), Afghanistan (2002) and Iraq (2003).

____

This post is part of a synchroblog (syncronised blog) in which various people write about the same general theme from different points of view, and thus help one to see the bigger picture. Follow the links below to see the other posts. More links may be added later, as more people add their contributions. If you are participating in the synchroblog, please copy the links below and paste them to the end of our own post.

Fr John D’Alton (Antiochian Orthodox) of Fr John D’Alton on THE SYRIAN CIVIL WAR AND RESPONSES TO IT

Richard Fairhead (missional, evangelical, post/protestant, liberal/conservative, mystical/poetic, biblical, charismatic/contemplative, fundamentalist/Calvinist, Anabaptist/Anglican, Methodist, catholic, green, incarnational, depressed- yet hopeful, emergent, unfinished Christian) of Relational Journey on Who would Jesus bomb?

Ryan Peter (neo-evangelical) of Life-Ecstatic on Syria: The Show Must Go On

Steve Hayes (Orthodox Christian) of Khanya on Syrian civil war: no good outcome?

September 15, 2013

Bourgeois theology

People rarely queue around the block to buy a book. And when was the last time a prime minister had to ask the publisher for a copy as none was otherwise available? Philosopher, writer and former priest Mark Vernon tells the story of Honest To God.

It happened 50 years ago, in the spring of 1963. A book called Honest to God appeared on the shelves and caused a storm.

Before long, a million copies were sold in 17 languages. The author was a Church of England clergyman, John Robinson, the bishop of Woolwich in south London.

via BBC News – Viewpoint: When did people stop thinking God lives on a cloud?

I remember that time, and I remember buying and reading the book.

Honest to God by John A.T. Robinson

Honest to God by John A.T. Robinson

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

What can I say about a book that I read 50 years ago, and really have no desire to reread? It was the publishing sensation of its time, I suppose, and perhaps for the first time in decades got many people in the secular West buying and reading books about theology.

I bought the book for my mother, who had expressed an interest in reading it, and I read it too, mainly to see what the fuss was about. But I was disappointed. John A.T. Robinson seemed to be urging me to stop believing things about God I had never believed in the first place, and to replace them with things I had heard from people I regarded as religious quacks, and rejected.

Nevertheless the book did influence me quite strongly. It helped to being into focus things that I didn’t like in Western bourgeois theology, and to look for African threology and liberation theology instead. But that’s more about me than about the book, so it’s better said on my blog than on GoodReads.

Nevertheless the book did influence me quite strongly. It helped to being into focus things that I didn’t like in Western bourgeois theology, and to look for African threology and liberation theology instead. But that’s more about me than about the book, so it’s better said on my blog than on GoodReads.

My friend Tony McGregor recently drew attention to something he had written on The most influential books I’ve ever read and why?, and so I thought it might be interesting to reflect on the most influential books I read in 1963, and why.

I had just been at a conference of the Anglican Students Federation with Tony McGregor (and recently met him again for the first time since then, 50 years later). There was a bit of discussion of Honest to God at the conference, but two other books were also mentioned, so I read them first: The primal vision by John V. Taylor, and Images of God by A.C. Bridge. I also thought they were both much better than Honest to God.

I had just been at a conference of the Anglican Students Federation with Tony McGregor (and recently met him again for the first time since then, 50 years later). There was a bit of discussion of Honest to God at the conference, but two other books were also mentioned, so I read them first: The primal vision by John V. Taylor, and Images of God by A.C. Bridge. I also thought they were both much better than Honest to God.

I’ve already written something about The primal vision and Honest to God in a blog post on Christianity, paganism and literature, so I’ll try not to repeat too much of it here.

In Honest to God Robinson said, as one of the more famous reviews of his book headlined it, “Our image of God must go”. Robinson’s idea of “our” image of God was of an old man sitting on a cloud somewhere up in the sky. I’m not sure who had that image of God, or how many there were who held it, but I certainly didn’t.

But there is an interesting thing in church architecture: in the Western church there was a style of building churches with tall spires, pointing to a God “up there”.

But there is an interesting thing in church architecture: in the Western church there was a style of building churches with tall spires, pointing to a God “up there”.

G.K. Chesterton once wrote a short story, The hammer of God, where someone had been murdered by a hammer thrown from a church tower. And one of the point that Chesterton made was related to the architecture. The murderer was putting himself in the place of God, looking down on men, and seeing them as insignificant, and being in a position to pass judgement on them. But the place for human beings was not up in the tower, looking down, but rather in the nave of the church, looking up; looking to God in humility, rather than looking down on men, with pride.

So the point is not the physical location of God, but the spiritual location of man, which Bishop John Robinson seems to have misinterpreted. But the spire, pointing beyond the church itself, can make it seem that God is otherwhere than here.

Orthodox Church architecture speaks of something different. There are no spires, bur rather domes. Unlike the spire pointing to a heaven up in the sky far away and beyond, the dome encloses the space, and speaks of heaven on earth. This is also reflected in an Orthodox greeting:

Orthodox Church architecture speaks of something different. There are no spires, bur rather domes. Unlike the spire pointing to a heaven up in the sky far away and beyond, the dome encloses the space, and speaks of heaven on earth. This is also reflected in an Orthodox greeting:

“Christ is in our midst”

“He is and ever shall be.”

Bishop John Robinson undertook to interpret three German theologians to an English audience: Rudolf Bultmann, Paul Tillich and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. I knew little of the works of Bultmann and Tillich, but I had read quite a lot of Bonhoeffer’s writings, and I thought that Robinson had grossly misinterpreted them. It looked to me like an English armchair theologian sitting in comfort and bowdlerising the teaching of Bonhoeffer, who had lived and worked in a crisis situation in Nazi Germany.

Bultmann believed that Christian teaching needed to be demythologised, but John V. Taylor in The primal vision showed that Western Christianity was too demythologised already, and needed to be remythologised by African thinking. Taylor began one of his chapters with a quote from Nicolas Berdyaev that has stuck with me ever since:

Myth is a reality immeasurably greater than concept. It is high time that we stopped identifying myth with invention, with the illusions of primitive mentality, and with anything, in fact, which is essentially opposed to reality… The creation of myths among peoples denotes a real spiritual life, more real indeed than that of abstract concepts and rational thought. Myth is always concrete and expresses life better than abstract thought can do; its nature is bound up with that of symbol. Myth is the concrete recital of events and original phenomena of the spiritual life symbolized in the natural world, which has engraved itself on the language memory and creative energy of the people… it brings two worlds together symbolically.

I was also influenced by a film, and the novel on which it was based, Sammy going south, which I reviewed at Sammy going south: book review | Notes from underground. It was about a ten-year-old English boy, Sammy Hartland, whose parents were killed in the Anglo-French bombing of Suez in 1956. His parents had told him of an aunt in Durban somewhere to the south, so he set out to walk to Durban to find her.

Film Sammy going south (1963, based on the novel of the same name (1961)

The South African Sunday Express, in its review, accused the film of pandering to currently fashionable views (what is now called political correctness), of showing white people as duplicitous villains and black people as kind to wandering orphans like Sammy. That wasn’t quite accurate, as there was also a white hunter who treated him well, but generally it was black people who treated Sammy as a person, and the white people he encountered who treated him as an object of exploitation and self-gratification.

This theme seemed to complement that of The primal vision, which espoused the African view that “a person is a person because of people” rather than the Western view of seeing people as “human resources” or “labour units” and generally as objects to be manipulated.

What Bishop John Robinson proposed to put in place of the outmoded image of God that he rejected reminded me of nothing so much as the theology of Nicol Campbell, who published a sentimental monthly booklet called The path of truth, which was lapped up by middle class white widows and divorcees living in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg. My mother took it for a while, but soon saw through it, especially after overhearing Nicol Campbell at a gathering speaking to an old school friend whom he had not seen for a long time, and as they exchanged “What are you doing now?” information Nicol Campbell said to his friend that there was money in religion, and he was making it hand over fist. That was well over 50 years ago, but there is money to be made from it still, as the undiminished flood of self-help and “inspirational” books from self-styled “life coaches” attests.

A couple of years later I met John Robinson. I went to England to study, and scarpered from South Africa at a few hours’ notice one step ahead of the security police. After a rather exhausting 48-hour journey I arrived at the home of Canon Eric James, who had offered to shelter me. Bishop John Robinson was having dinner with him, and we exchanged a few words. He was known as a theological liberal, and I was there at that time because I was a political liberalism, and our conversation showed me quite clearly that theological liberalism went hand in hand with political conservatism, because it was based on the fundamental idea that the church must adapt its theology to fit in with the status quo in the world. And, as G.K. Chresterton once put it, as long as the vision of heaven is always changing, the vision of earth will always remain exactly the same.

September 13, 2013

Satanism and satanic ritual abuse

A couple of weeks ago I was asked to review a document on Satanism and Satanic Ritual Abuse (SRA) in South Africa. I looked at the document, asked the opinions of some academic researchers who were more familiar with the topic than I was, and then sent my comments to the authors. I don’t want to say any more about the document and my comments on it here — it’s up to the authors to decide what they do with them.

But the document did set me thinking about the topic generally, though not for the first time.

A few years ago, prompted by reports of satanic ritual abuse in the media, I wrote an article Will the real satanists please stand up? Until a few weeks ago that was the article that had got the highest number of readers of this blog in a single day, so the topic must have been of some interest.

One of the things that the review has persuaded me to do is to distinguish between Satanism as a religion (with a capital S) and satanism as a Christian deviation (with a small s). Satanism as a religion dates back to the 1960s, when Anton LaVey wrote The Satanic Bible and founded the Church of Satan. But, as far as I have been able to discover, most cases of satanic ritual abuse have nothing to do with LaVeyan Satanism or members of the Church of Satan. They all seem to be linked to satanism with a small s, which is a Christian deviation, a Christian heresy.

I have raised this in an Internet forum that deals with the literature of the Inklings in particular, and Christian horror/fantasy literature in general. Charles Williams (one of the Inkings) refers to “satanism” in one of his novels, War in heaven, which was published in 1930, the year Anton LaVey was born, which indicates to me that LaVey cannot have copyright on the term; nor should he be regarded as the sole arbiter of its meaning. War in heaven also contains an incident which could be described as “satanic ritual abuse”. It is, of course, fictional, but it can serve to illustrate the usage of the terms.

In this extract from the novel, Gregory Persimmons, a publisher and a satanist, has invited his employee, Lionel Rackstraw, and his family to spend some time at his home, and has this conversation with Lionel:

Gregory turned his head to see better the young face from which this summary of life issued. He felt perplexed and uncertain; he had expected a door and found an iron barrier.

“But,” he said doubtfully, “had Judas himself no delight? There is an old story that there is rapture in the worship of treachery and malice and cruelty and sin.”

“Pooh,” Lionel said contemptuously; “it is the ordinary religion disguised; it is the church-going clerk’s religion. Satanism is the clerk at the brothel. Audacious little middleclass cock-sparrow!”

“You are talking wildly,” Gregory said a little angrily. “I have met people who have made me sure that there is a rapture of iniquity.”

“There is a rapture of anything, if you come to that,” Lionel answered; “drink or gambling or poetry or love or (I suppose) satanism. But the one certainty is that the traitor is always and everywhere present in evil and good alike, and all is horrible in the end.”

“There is a way to delight in horror,” Gregory said.

In a more recent case of satanic ritual abuse that came before the courts, the murder of Kirsty Theologo, the participants used the Christian Bible to justify their actions, not LaVey’s Satanic Bible. In most of the cases that I have read about, in the newspapers, the satanists were not even “the clerk at the brothel”; they were schoolchildren.

As far as I can see, in cases of satanic ritual abuse in South Africa:

most of the victims are white

most of the perpetrators are white

the perpetrators are usually teenagers or “young adults”

the perpetrators do not practise Satanism *as a religion*

the perpetrators practise satanism as a Christian deviation

This may not be statistically accurate, as it applies only to cases that have come to my notice through press reports, which may not be all that accurate.

There have also been ritual murders that have involved black people. For example: a few years ago a child was murdered near Pretoria and the body built into a hairdressers shop under construction. The aim, it emerged in court, was to increase the prosperity of the business. Now this was, by any standards, “ritual abuse”, though it probably wasn’t “satanic”. But such ritual abuse was found in pre-Christian societies in Europe too, as archaeologists have discovered, so it is not peculiarly African, and nor is it “colonial”.

In South Africa, most cases of satanic ritual murder have involved white teenagers.

How could this be, and what could be the cause of it?

Here is the germ of a hypothesis:

I recall that in the 1970s there were a number of books published by Evangelical publishers in the USA, warning of the dangers of “the occult”. I looked at several of them on the shelves of bookshops, and may even have one or two on my own shelves. As I recall, they were not very accurate, and most of them described, or at least hinted at, satanic conspiracies.

My inchoate hypothesis is that some people in South Africa read some of these books, and took them seriously, and that among those who did so were some policemen who, regarding themselves as experts as a result of what they had read, proposed and staffed the “occult crimes unit” of the South African Police.

They then, being not only experts, but policemen and thus authority figures, went round to schools to warn the youth about the dangers of meddling in “the occult”. Among the other disinformation they peddled were allegations that the peace symbol was satanic, and represented “the witch’s claw” and other such nonsense.

They were welcomed most enthusiastically in white Afrikaans-medium schools which tended to be the most authoritarian, and the most assiduous in pursuing the government’s indoctrination policy, known as “Christian National Education” (which was neither Christian, nor national, nor education).

In doing this, they provided the pupils at the schools with a marvellous tool for rebelling against the authoritarian education system, and some of them, in doing so, called themselves “satanists” and adopted the very symbols that they had been warned against in the lectures, based on the Evangelical books published in the USA, which warned of the dangers of “the

occult”.

So my hypothesis is that if you are looking for the roots of satanic ritual abuse in South Africa, they are probably to be found in certain American Evangelical publications of the 1970s.

This is not fact; it is a half-baked hypothesis.

But I think it would be interesting if some academic researchers picked it up and baked it.

August 31, 2013

Gray Falcon: Our Syria

As the USA threatens to bomb Syria, here is a comment from Serbia, which was on the receiving end of American bombing in 1999.

Commentary by Željko Cvijanović, Novi Standard (Belgrade), August 30, 2013.

Translated by GrayFalcon. Original here.

When the first missiles strike Syria and we are shown the first horrific images – carefully selected to scare us enough without riling us up too much – it would be nothing we haven’t seen before, in the case of some of us, lived through ourselves. “There is nothing new under the sun,” one could say. Except our eyes are less reliable than ever before. Because there are many new things here, and drawing on analogies can only help us see the heart of the matter – while missing everything else.

1.

America is being led into a new war by a president who got elected claiming to be the antithesis of his belligerent predecessor; who promised Americans hope through changes that would bring the country back from the pitfalls of Bush the Younger’s “wars on terror.” Today, the man who received a Nobel Peace Prize not so long ago as an advance payment for expected greatness, is declaring that it is not a question whether Syria will be bombed, but when.

At last — a humanitarian missile!

Meanwhile, heading the Department of Defense into the conflict is Chuck Hagel – one of the staunchest critics of Bush’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, a rare member of the Washington establishment who dared criticize Israel, and almost the lone advocate of dialogue with Iran – in other words, one of the most peaceful Pentagon principals since America began waging war beyond its borders.

Providing the diplomatic cover for missiles and bombers would be Vietnam veteran and anti-interventionist John Kerry, whose arrival at the head of the State Department this winter promised hope for a peaceful resolution of the Syrian conflict, due to his cordial relationship with Bashar al-Assad.

Last, but not least, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in this war will be four-star General Martin Dempsey, who opposed a direct intervention by offering a worrying estimate that such an adventure would require “hundreds of scenarios, thousand of soldiers, and billions of dollars.”

There have never been more doves at the top, never less support for a war in the American public, yet America has never been more belligerent. What gives?

via Gray Falcon: Our Syria, where you can read the full text.

August 28, 2013

The values of our time

In times of change, learners inherit the earth; while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists.

One of my Facebook friends posted that a couple of days ago, and I found myself feeling quite ambivalent about it, partly because of the book I have been reading — Various pets alive & dead by Marina Lewycka (more about that below), and partly because of some recent events, and responses to them.

In some ways I think that the statement is positive. I’ve always been in favour of lifelong learning. Though I’m officially retired, I welcome the opportunity to supervise postgraduate students because it enables me to learn more and to try to keep up, at least in my own field.

But the world in which I did most of my learning was the world of apartheid and the struggle against it, and, of course, that world no longer exists.

The thing about this book is that it gives a picture of the world that does exist now, and of the people who have inherited it because they were willing to learn its lessons and its values, and to apply them.

But I’m not sure that those values represent our generation’s hopes for a post-apartheid world, or even a post-Bolshevik world.

Various Pets Alive & Dead by Marina Lewycka

Various Pets Alive & Dead by Marina Lewycka

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

In many ways this is a novel for our time, a novel of our time. It’s about the generation gap, which has become inverted for the generation that invented (or provoked) the term “generation gap”. That’s my generation.

Marcus and Dora were part of a left-wing commune in the 1960s and 1970s and hoped that their children would grow up to share their ideals. Their daughter Clara is a teacher of rather prosaic subjects, but at least she is teaching working-class kids. Their mathematically-gifted son Serge, they believe, is working on a PhD in Cambridge, and seems set for a career of pure research, which will not prop up the blood-sucking capitalist system. What they do not know, and what he is too afraid to tell them, is that he has been head-hunted as a risk analyst by a firm of high-flying financiers, and is helping them to ride the rough seas of the financial crisis of 2008, and is what they would regard as immorally rich, and getting richer. His parents’ values and his upbringing give him occasional twinges of conscience, but he manages to suppress them quite easily, for the most part. He is a bit more worried about getting caught.

The third child, Oolie-Anna, has Down’s syndrome, and so lives at home, but her social worker keeps urging that she move out and become independent, because her aging parents will not be able to look after her for ever.

I read A short history of tractors in Ukrainian by Marina Lewycka about seven years ago. That was mainly about Ukrainian immigrants who had settled in Britain, and was both funny and sad.

This one is also funny and sad, but the main characters are British, and there is only one Ukrainian, who is not a viewpoint character. The viewpoint moves mostly between Doro, the mother, and her two children Clara and Serge, with Marcus having his say much more rarely. There is thus no protagonist, or perhaps one could say no human protagonist, because the real protagonist is the new capitalism, and its effects on its devotees and its victims.

It is set in Britain, but the kind of values it represents are very much evident in South Africa today as well.

Perhaps I could add a postscript about the values of different generations. A couple of days ago I wrote another blog post on an Afrikaans cultural award for two Orthodox priests | Khanya. After I wrote it, there was a report in the mainstream Afrikaans press about it, which I found after some help: Beeld : Ortodokse vertalers word vereer.

I got the hard copy edition of Beeld (27 Aug 2013), and the article was on page 3, at the bottom. At the top was a more general report on the event — the commemoration of 80 years of the Afrikaans Bible. In the middle of the page, separating the two linked articles, was one about the antics of Miley Cyrus on a VMA show. I’ve seen that there has been quite a lot of comments on that on Twitter, and elsewhere, though I haven’t read the article yet, so I don’t know what her antics were, nor what a VMA show is. I know I could read the article to find out, but I haven’t yet done so, and keep putting it off.

What I do know is that Miley Cyrus is a celeb of some sort, and that the learners who are willing to put some effort into learning all that there is to know about celebs, and to either become one or profit from their existence will inherit the earth.

But I’m not sure that that’s the kind of earth I want to inherit.

August 26, 2013

Orthodox mission in Rwanda

Our daughter Julia Bridget Hayes, who is studying theology in Athens and supporting herself by painting ikons, sent us this report aboout the mission outreach of her parish: “My Spiritual father and some of the youth from my parish went to Burundi and Rwanda on a mission trip (our parish built a church of St Alexios the Man of God in Burundi). Here is a short article and photos from Rwanda.“

With the Grace of God and following the strenuous efforts and prayers of his Eminence Innocent Bishop of Burundi and Rwanda, the first steps of the Orthodox Church in Rwanda began.

On Saturday 17-8-2013, his Eminence accompanied by Fr George Schinas and hierodeacon Nektarios Stogiannis and a team from the Church of St Dimitrios Loumbardiaris in Athens, as well as a group of women from Uganda organised a catechetical meeting with about 500 Rwandans. The meeting included an introduction by his eminence Bishop Innocent, dividing the local people into work groups, a concluding homily and a meal. Questions were asked and answers given on crucial matters of the Orthodox Faith. The Rwandan’s interest was genuine and their zeal for Orthodoxy is continually increasing.

The next day, on Sunday morning, a hierarchical Divine Liturgy was celebrated which our Rwandan brethren attended as catechumens and were amazed by the liturgical wealth of our Church.

After the Divine Liturgy there was an opportunity to share fellowship with the locals who prepared a meal for everyone with traditional African foods. On our departure it was clear that there was a renewal of their interest in baptism and their incorporation into Orthodoxy. It appears that our Trinitarian God is opening a new page for the One, Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church in the much suffering and hurting Rwanda. Christ opens His embrace to all. Let us pray that His Holy Will be done.

Julia Bridget Hayes

Website: www.ikonographics.net

E-mail: ikonographics@gmail.com