Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 56

January 1, 2014

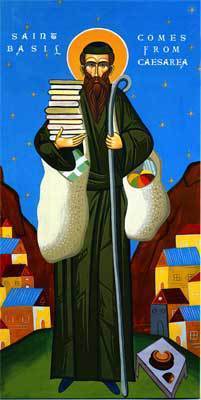

St. Basil teaches us to give!

"The bread which you do not use is the bread of the hungry; the garment hanging in your wardrobe is the garment of him who is naked; the shoes that you do not wear are the shoes of the one who is barefoot; the money that you keep locked away is the money of the poor; the acts of charity that you do not perform are so many injustices that you commit.

A good thought for St Basil's Day.

December 30, 2013

2013 in review

The WordPress.com stats helper monkeys prepared a 2013 annual report for Khanya blog. Many thnaks to those who took the time and trouble to comment on the posts.

Here’s an excerpt:

Madison Square Garden can seat 20,000 people for a concert. This blog was viewed about 62,000 times in 2013. If it were a concert at Madison Square Garden, it would take about 3 sold-out performances for that many people to see it.

Click here to see the complete report.

December 22, 2013

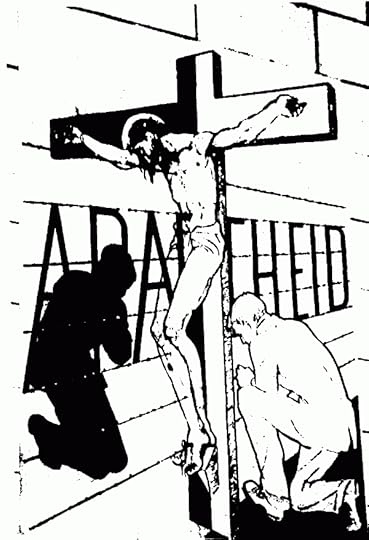

Apartheid and multicultural education

One of the characteristics of the apartheid ideology was that it was strongly, if somewhat selectively, opposed to multicultural education. This should not be surprising, since one of its fundamental premisses was that people of different cultures and ethnicities should not mix.

So, for example, apartheid educationists (or pedagogicians, as they liked to call themselves) said things like this:

… pedagogically it is the greatest conceivable injustice to a child if he is not educated completely within his own culture. A situation cannot be allowed to arise which causes conflict between the culture taught at home and that taught at school. As a result, children from minority groups often find themselves in an agonizing and bewildering dilemma accompanied by an identity crisis (Griessel et al. 1991:16).

or this, from the same source:

…it is irresponsible and unpedagogic to allow a teacher to ‘educate’ children from a different ethnic or cultural group than his own, because he cannot educate them according to the values and norms upheld in their own cultural communities.

If such an unpedagogic practice is followed the child is deprived of the opportunity to identify only with adults from his group. The child’s sense of identity is actually impaired and a feeling of inferiority arises when his teacher’s race, culture and mother tongue differ from his own. Without an identity, which can only be acquired by means of education in a particular culture, man cannot live a meaningful life (Griessel et al. 1991:172).[1]

These quotations are from a textbook on “Fundamental Pedagogics“, a pseudo-scientific ideology that was used to prop up the “Christian National Education” system put in place by the apartheid government, and taught to most teachers in the country.[2]

I was therefore a bit concerned when someone recently posted the following online:

Children will be confused as long as they live in multiple cultures incoherent internally and disharmonious in such proximity with each other. Study after study says that the kind of diversity so many people believe strengthens group and makes them more tolerant has the opposite effect. More than that it dangerously undermines our sense of self.

It looked to me very much like the kind of thing that was often said to justify apartheid education. When I pointed this out to the author, however, he took offence, and no useful discussion followed, perhaps because it was posted on Google+, which I find a poor medium for discussion. Nevertheless the question will not go away.

Apartheid education was based on the theory of “ownaffairs”, and nationalism was defined as “love of one’s own”.

B.J. Vorster, who later became prime minister of South Africa, equated Christian Nationalism with National Socialism and Fascism, and Christian National Education was developed to inculcate the principles of Christian Nationalism, though many Christian educationists who did not subscribe to the apartheid ideology described it as “neither Christian, nor national, nor education”.

The National Party government, after it came to power in 1948, acted swiftly to establish Christian National Education and apartheid in education.

One obstacle to this was that the then province of Natal was not controlled by the National Party, and education was, in terms of the 1910 constitution of South Africa, a provincial responsibility. The Bantu Education Act made “Bantu Education” separate from “Education”, and was controlled by a new department of “Bantu Education”, which effectively took away control of education of education of black children from the provinces, and it became, along with its parent body, the Department of Bantu Administration and Development, a kind of state within a state.

The Department of Bantu Administration also effectively nationalised church schools for black children throughout South Africa. The government did not want to allow any schools that would teach anything other than the official ideology.

There was a lot of doublethink in this. Education was declared to be a racial “ownaffair”, but was controlled by the (white) National Party central government. The “Bantu” were to be encouraged to develop along their “own lines”, and those lines were laid down by the (white) central government. As Dr Verwoerd said when introducing the Bantu Education Bill in parliament:

There is no place for [the Bantu] in the European community above the level of certain forms of labour … What is the use of teaching the Bantu child mathematics when it cannot use it in practice? That is quite absurd. Education must train people in accordance with their opportunities in life, according to the sphere in which they live (see here, where there are more quotes on apartheid and education).

The provinces still retained control of education of white children, however, at least until 1983, when provinces were abolished and education became an “ownaffair” for whites, Asians and coloureds as well.

In the National Party-controlled provinces in the 1950s, Transvaal, Cape Province and Orange Gree State, there was a move away from parallel-medium and dual-medium schools, in which English-speaking and Afrikaans-speaking white children were taught in the same schools. In 1976, however, Soweto school children revolted against an attempt to impose dual-medium (Afrikaans and English) education in black schools.

In the National Party-controlled provinces in the 1950s, Transvaal, Cape Province and Orange Gree State, there was a move away from parallel-medium and dual-medium schools, in which English-speaking and Afrikaans-speaking white children were taught in the same schools. In 1976, however, Soweto school children revolted against an attempt to impose dual-medium (Afrikaans and English) education in black schools.

One area in which no multicultural education was allowed was religious education, in which the syllabus prescribed Calvinist Protestantism. This was no “ownaffair”. There was to be no diversity. In Asian “ownaffairs” schools Hindu and Muslim children learned side-by-side, but for their teachers, courses in Calvinist “Biblical Instruction” were compulsory, and they were taught that the law required them to teach that in their schools.

In white schools, even English-speaking ones, the same applied. One of our children, when in Grade 7 at Rietondale Primary School, objected to the superficial treatment of the split between Eastern and Western Christianity in their history textbook. She phoned our parish priest, who was a lecturer in church history at the University of South Africa, to ask if he would be willing to speak at the school about it. He was willing, but the school authorities were not. He was Orthodox, and that was definitely far too multicultural to fit into the Christian National Education pattern.

Even 20 years after the end of apartheid, the question of multicultural education continues to be a vexed one, and it is something I think we need to be discussing.

___________

Notes and references

[1] Griessel, G.A.J, Louw, G.J.J. & Swart, C.A. 1991. Principles of educative teaching. Pretoria: Acacia. ISBN: 0-86817-012-7.

[2] The University of South Africa, which was the biggest distance-education university in the southern hemisphere, had about 30000 students in the Education Faculty in any given year in the 1990s. Most of these were teachers seeking to improve their qualifications inorder to get promotion. The Education Faculty was notorious for being wedded to Fundamenal Pedagogics.

December 15, 2013

Madiba Magic strikes again

When we got back from church this morning we watched the last part of Nelson Mandela’s funeral on TV, and when the helicopters came past with the flag, I was reminded where I had seen that before, on the day of his inauguration at the Union Buildings nearly 20 years ago, on 10 May 1994. It was a memorable day in many ways.

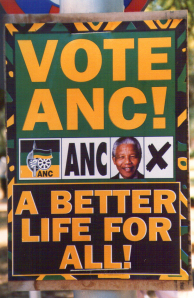

Elelction poster for the first democratic election in 1994. Promise fulfilled.

Immediately after the inauguration Nelson Mandela left for the FNB stadium, where there was a football match between South Africa and Zambia. South Africa won.

A year later he was there again for the final of the rugby world cup, and again South Africa won. The following year he was there for the the final of the African Cup of Nations, and again South Africa won. People began to talk about “Madiba magic”. His presence seemed to inspire our sportsmen to do their best.

Last Tuesday a memorial service was held for him at the same venue, and just about everything that could go wrong did. It was quite embarrassing to watch, even on TV. But the body of Madiba was not there. The Madiba magic had gone.

But today, at his funeral at Qunu, he was there, and things went very well. From what we could see on TV, it was dignified and well organised, and the nation, and the world, gave him a good send-off. They sang his favourite hymn again, Lisalis’ idinga lahko, and it sounded good, and not as disastrous as it was in the stadium. I think the organisers had learned a few things from Tuesday’s disaster, and got their act together. And perhaps it was the Madiba magic working, for one last time.

His coffin was escorted to the grave by marching soldiers, young men, black and white, marching together. And I wondered if, 30 years ago, some of their fathers had perhaps been facing each other on opposite sides of what was called, by the government of the time, “the Border War”, one side fighting to keep Nelson Mandela in jail until he died, and the other side fighting to free him, and all of us, from tyranny. And there they were, marching side-by-side, to say goodbye to the man who had spent his life trying to bring us together on the same side.

Waiting in the queue to vote in the first democratic election, in 1994, at a school in Mamelodi East.

While the first part of the service was going on we went to Mamelodi East for the Readers Service (Obednitsa) in the humble home of Christina Mothapo, 87 years old. We followed it with our own short memorial service for Madiba, just a few of us. It seemed appropriate, as it was the ninth day after his death.

Kontakion

With the saints give rest, O Christ

To the soul of Thy servant

Where sickness and sorrow are no more

Neither sighing, but life everlasting.

Ikos

Thou only art immortal

Who hast created and fashioned man

For out of the earth were we mortals made

And unto the same earth shall we return again

As Thou didst command when Thou madest me, saying unto me:

for dust thou art and unto dust shalt thou return

Whither we mortals all shall go

Making our funeral dirge the song:

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

And that was the same theme at the funeral service at Qunu. Nelson Mandela grew from that earth, and now he has returned to it at last. But we’ll miss his magic.

December 13, 2013

Sciences, humanities and genetic engineering – book review

The fires of Arcadia by G.B. Harrison

The fires of Arcadia by G.B. Harrison

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

The topic of the sciences versus the humanities seems to have come up quite a lot recently, and I blogged about it last month here The dissing of the humanities | Khanya. It has also come up in various discussion forums. In one such forum I was reminded of the Victorian myth of the polymath scientist, when the media make Richard Dawkins, a biologist, an instant expert on topics like philosophy, theology and history.

And then I picked up this book.

I’ve been gradually entering our books into a database, so that we can see which ones we’ve read and which ones we haven’t. We have sometimes bought books that we already have, so it’s not quite as silly as it may seem. But how we got this book, I cannot remember. A street book stall, perhaps. It was marked down from R1.95 to 59c to 10c, and perhaps we bought it just because it was cheap.

It’s written by a Shakespearian scholar, so it comes down firmly on the side of the humanities. It was published in 1966, just a year or two before student power demonstrations broke out all over. It would probably not appeal to feminists at all, as all the main characters are male, and the only strong female character is almost, but not quite, the villain of the piece. But it does highlight some of the problems and tensions that arise if the sciences and the humanities are kept apart, and 45 years later genetic engineering is still a live issue.

So I found it a surprisingly good read, but perhaps that’s because I’m prejudiced in favour of the humanities.

December 7, 2013

After Mandela, what?

The death of Nelson Mandela has prompted many attempts to assess and evaluate his life and works and achievements. On the day following his death my Facebook status/wall/timeline or whatever they call it now was filled with tributes from people around the world. Most were positive, especially those from South Africans.

The few negative responses I saw were mostly from American libertarians, which I think says more about American libertarians than it does about Nelson Mandela.

Some conspiracy theorists and malicious persons did their best to predict pogroms after his death, as described in this article Helter Skelter In South Africa? Alarmists Spread Fear That Whites Will Be Massacred After Nelson Mandela Dies.

But apart from American libertarians and the loony right (like this idiot, who compared Mandela with Adolf Hitler, Joe Stalin, and Pol Pot) most people emphasised his positive achievements. Yes, the media tended to be hagiographical and uncritical, so that some suggested that they airbrushed his failings. But most of those who complained along these lines indicated as the “truth” the right-wing media that vilified him. There was a difference, though. The hagiographical articles can at least report things he actually said, even if somewhat selectively. In the time that the right-wing media vilified him, he could not be quoted, and the picture of him was coloured by the paranoia of the Security Police, who are also quoted in one of the more balanced articles of this type, here: Nelson Mandela: he was never simply the benign old man – Telegraph

But if we are thinking about what happens after Mandela, we already know. He retired as President and leader of the ANC nearly 15 years ago. We have seen what has happened. As my fellow blogger Macrina Walker puts it:

I suspect that one of the reasons many of us are so saddened at Madiba’s passing is that he was the last of a generation and represents an ideal that all-too-often appears to be crumbling. However much lip service people pay to a life of sacrifice and integrity, the reality is that such ideals are quickly undermined by the temptations of self-enrichment and easy pleasure. A virtuous life has never been easy, but it often seems as if we live in a world in which it is becoming more difficult.

via A Good Life: Saint Nicholas, Saint Anthony and Madiba | A vow of conversation.

The last of a generation

As someone pointed out on Twitter, three great trees fell at ten year intervals: Oliver Tambo in 1993, Walter Sisulu in 2003, and Nelson Mandela in 2013.

One is tempted to think that we will not see their like again.

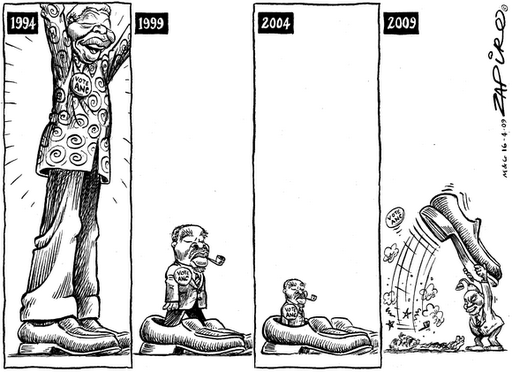

As Zapiro put it in a cartoon in 2009:

South Africa’s Presidents

Thabo Mbeki, for all his failings, was vastly better than some of his contemporaries, notably Tony Blair and George Bush.

But if we want to assess Nelson Mandela’s legacy, we need to look at the decade from 1989-1999.

1989 was the Annus Mirabilis, the wonderful year in which freedom was breaking out all over, and dictators fell in many countries, including South Africa. The seeds were sown a bit earlier when Mikhail Gorbachev in the USSR introduced policies of glasnost and perestroika, and in South Africa, with the fall of PW Botha in 1989, there was talk of Pretoriastroika. The release of Nelson Mandela and the unbanning of the ANC (and other opposition parties) in February 1990 opened the way for a new democratic era in South African politics.

There were bad things in that time too. There was a lot of political violence, and much of it was provoked by the so-called “Third Force”. Perhaps historians will eventually establish more clearly the nature of that violence, and the nature of the “Third Force”, but I don’t want to talk about that now.

My main memory of that period was that the ANC, in particular, seemed to be taking one of their own slogans seriously — that “the people shall govern”. A lot of energy and effort was put into soliciting public opinion and ideas on all kinds of things, from the content of the constitution to the promotion of education, art and culture. Conferences were held, submissions sought, and many of these things were subsequently incorporated into the constitution.

There was a feeling of “inclusiveness” in the best sense. If there were to be leaders, the leaders must be sensitive to the needs of the people, and must listen to the people. There was a Zulu proverb, that a chief is a chief because of the people. So there was a ferment of ideas, and a feeling that anything was possible.

This inclusiveness of was not the ideological western kind, but part of the African idea of ubuntu.

I had sometimes been at church synods that had been run along the lines of Western parliaments, where a motion was proposed and seconded and debated and amended and eventually a vote was taken, and the Ayes or the Noes had it. But sometimes black members of synod complained that this adversarial procedure was not in accord with African culture, where the matter was discussed until consensus was reached. And I saw this in a somewhat different setting, in the Anglican diocese of Zululand, where it happened. People would discuss something, and perhaps have different viewpoints, but when it had been thrashed out the bishop would sum up, and announce the decision. But it was not his decision alone, but that of the meeting. He was the voice of the people.

The first democratic election in South Africa was inclusive. There were no areas in which people were registered to vote. You could vote anywhere, and as long as you could prove that you were who you were, you could vote. There was the same spirit of inclusiveness in the Government of National Unity (GNU) that followed. Inkatha had threatened to boycott the election until the last minute, and as a result of their intransigence 700 people died. In the end they not only participated in the election, but in the GNU that followed. There was a deliberate effort to include them.

Nelson Rolihlala Mandela 1918-2013

The only holdout was the Democratic Party, which was based on white culture, and wanted to be an opposition, and therefore to oppose everything the government of National Unity did, good or bad, because the job of an opposition was to oppose and therefore to oppose everything on principle. That was part of the adversarial principle of law and politics, the “Westminster system” that South Africa had inherited from the British Empire.

The Annus Mirablilis of 1989 therefore marked the beginning of a miraculous decade of freedom in South Africa. Whether it did the same in Romania, Hungary, Poland, Russia, Ukraine, Azerbajan and other countries that had been freed from dictatorship at the same time, I don’t know. But in South Africa it was a good time to be alive, to savour new-found freedom, a time of seemingly limitless possibilities.

And Nelson Mandela was the one at the helm during this time, and so became the symbol, the “icon” (as the media would have it) of our new-found freedom.

But such things never last. There is always the worm in the apple.

The 19th-century liberal historian, Lord Acton, once famously said that all power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Between 1990 and 1994 the ANC was not in power. It had no patronage, and so could freely promote the free flow of ideas. It encouraged the people to speak, and it listened to what the people said. Some people, so inured to the oppressive rule of the past, were still afraid to speak. Some, so brainwashed by National Party propaganda, were incapable of hearing the ANC’s invitation to speak. Some, like the dwarfs in CS Lewis’s story The last battle, were still convinced that they were in a dark stable theatened by a monster, and not in the open air of freedom. But some people did speak, and the ANC listened.

But all power tends to corrupt, and after 1994 the ANC had power. Certain people began to see that if they could get themselves elected to the committee of the local ANC branch, they could influence the choice of candidates for local government elections or provincial elections, and thus influence the people who controlled the budget, and so the tenderpreneur was born.

Some people in the ANC still listened to the voice of the people, or tried to, but for an increasing number the voice of money grew louder and louder, and drowned out the voice of the people.

Thabo Mbeki was aware of this, and he warned about it in his address to the 52nd National Conference of the ANC at Polokwane in December 2007. But he wasn’t even preaching to the choir, because by then most of the choristers were there because they had money, and not because they could sing.

But I don’t think of that as Mandela’s legacy. Mandela’s legacy was that miraculous decade of 1989 to 1999, when anything seemed possible. And perhaps there are still some people around who caught the vision, and will pass it on to others, who may, sometime, work to realise it.

And in the mean time, we sing, with Parchment:

Yesterday’s dream didn’t quite come true

We fought for our freedom, and what did it do?

Now no one can see where they stand.

So let there be light in the land,

Let there be light in the people

Let there be God in our lives fromj now on.

December 6, 2013

Mandela — an icon, but of what?

Nelson Mandela has died, and most of the TV stations have programmes paying tribute to him — BBC, CNN, Sky, eNCA, SABC, Al Jazeera. Only Russia Today does not, they are more concerned about the situation in Ukraine.

Nelson Rolihlala Mandela 1918-2013

Over and over again journalists are referring to him as an “icon”. An “icon” of what? It still sounds vaguely blasphemous.

He has repeatedly told journalists (and the world) that he is not a saint, and that he rejects the depiction of him as any kind of saint. So if he is not a saint and not the icon of a saint, what is he?

When I think of what Nelson Mandela means to me, what difference he has made to my life, a song comes to mind, a song we used to sing 30 years ago:

Thou hast turned my mourning into dancing for me

Thou hast put off my sackcloth

Thou has turned my mourning into dancing for me

And girded me with gladness.

That is a quotation from Psalm 29/30, and the whole Psalm is one that Nelson Mandela could have sung the day he was released from prison. But that is not quite what it means to me.

For 30 years, from 1964 to 1994, another psalm was never far from my thoughts, Psalm 125/126.

When the Lord turned again the captivity of Sion, then were we like unto them that dream

But for 30 years it seemed that it was no more than a dream, and the captivity was never turned, and whenever a friend was banned or detained without trial I thought of the other verses:

Turn our captivity O Lord, as the rivers in the south.

They that sow in tears shall reap in joy.

He that now goeth on his way weeping, and beareth forth good seed

Shall doubtless come again with joy, bringing his sheaves with him.

Then, after 30 years of waiting, that day finally came — on 27 April 1994, when we were able to vote for the first democratically-elected government in South Africa.

The Lord did eventually turn our captivity, and the instrument he used to do it, the image, the icon of our liberation, was Nelson Mandela.

So yes, there is a sense in which he was an icon. But in the context of those psalms, it can seen as more than an icon, but rather something like a messiah. And political messianism is a very dangerous thing.

But whatever the dangers may be, Nelson Mandela seems to have avoided them, perhaps because he fitted a role described by G.K. Chesteron:

Much vague and sentimental journalism has been poured out to the effect that Christianity is akin to democracy, and most of it is scarcely strong or clear enough to refute the fact that the two things have often quarrelled. The real ground upon which Christianity and democracy are one is very much deeper. The one specially and peculiarly un-Christian idea is the idea of Carlyle–the idea that the man should rule who feels that he can rule. Whatever else is Christian, this is heathen. If our faith comments on government at all, its comment must be this — that the man should rule who does NOT think that he can rule. Carlyle’s hero may say, “I will be king”; but the Christian saint must say “Nolo episcopari.” If the great paradox of Christianity means anything, it means this–that we must take the crown in our hands, and go hunting in dry places and dark corners of the earth until we find the one man who feels himself unfit to wear it. Carlyle was quite wrong; we have not got to crown the exceptional man who knows he can rule. Rather we must crown the much more exceptional man who knows he can’t.

And if there is one thing that stands out in Nelson Mandela’s career it that he did not see himself as a messiah, nor did he ever claim to be. He denied that he was a saint, and did not portray himself as a Moses-like figure, come to lead his people to freedom. He saw his position as leader of the ANC, and president of the country when the ANC won the 1994 election, as a matter of “cadre deployment”. It was a position in which he could serve the people, and he saw it as servant leadership.

“Cadre deployment” has a somewhat tarnished image nowadays. It is seen by many as a way in which party hacks and benefactors can be rewarded by giving them positions that they are often incompetent to hold. But for Nelson Mandela and his contemporaries it meant that he was not self-willed, choosing the job he liked, but served where his comrades wanted him to serve.

“Cadre deployment” has a somewhat tarnished image nowadays. It is seen by many as a way in which party hacks and benefactors can be rewarded by giving them positions that they are often incompetent to hold. But for Nelson Mandela and his contemporaries it meant that he was not self-willed, choosing the job he liked, but served where his comrades wanted him to serve.

He was not perfect; two failed marriages bear witness to that. But he was aware of his imperfections, and reminded people of them when they seemed inclined to treat him as a saint.

So I think yes, for me he is an icon, an icon of liberation and icon of servant leadership. But I wonder if that is what the media mean when they describe him as an “icon”?

In the prayer of absolution after confession, the priest prays over the penitent, Do thou thyself now be merciful to thy servant N. and grant unto him (her) an image of repentance, pardon and remission of sins…

I can think of two politicians who were icons, images, of repentance — John Profumo and Adriaan Vlok. But I suspect that those are the kinds of images that the media prefer to overlook, and they are not “icons” in the judgement of the media.

Nelson Mandela denied that he was a saint, but then all true saints did. He denied that he achieved anything on his own, but was simply one of the people who struggled together. When he gave his first public speech after being released from prison, he said it was the efforts of the people that had released him.

Many saints have also withdrawn from public life for a period, or even for their whole lives. St Seraphim of Sarov lived as a hermit for 17 years before he was called to any public ministry. And in a sense Nelson Mandela’s 27 years in prison were a similar kind of preparation. He emerged with a kind of wisdom analogous to that of startsi, spiritual elders.

He may not have been a saint, in the formal sense, but perhaps he was the image of a saint, an icon of liberation and servant leadership.

December 5, 2013

SA needs ‘radical reconciliation’ | Daily Maverick

This article in the Daily Maverick says that South Africa needs radical reconciliation, because there is a correlation between race and class. SA needs ‘radical reconciliation’ | Daily Maverick:

This is very much the central theme of this year’s findings: that the gap between the rich and the poor in South Africa is seen as the biggest source of division in the country by its citizens. This in fact is not new; income disparity has been cited in this position consistently since 2003. Race is now seen as only the fourth most divisive issue: to quote the survey, “It seems that, in the perceptions of citizens, race relations are steadily improving as class relations get worse”.

But hold up, those who love to jump on class, rather than race, now being South Africa’s cause celebre. The survey’s findings also show that wealth disparity still happens overwhelmingly along racial lines. In terms of the living standards measure (LSM), there are a higher percentage of black South Africans in the lowest four LSM groups than any other race group. By contrast, fully 73,3% of white South Africans fall within the two highest LSM groups. The IJR spells it out clearly: “Material inequality is the biggest obstacle to national reconciliation, but the majority of the materially excluded are black South Africans”.

but it goes on to say:

To quote the survey: “White South Africans feel the least disempowered in the face of big business and the most disempowered in the face of local government. Conversely, black South Africans feel the most empowered in the face of local government, and the least empowered in the face of capital”.

I am reminded, once again, of an English friend who said, in the 1960s, “When South Africa has sorted out the problem of the blacks and the whites, it will only then come to face the real issue: the haves and the have-nots.”

The article is very interesting, and the findings of the survey seem to coincide with my perceptions and observations.

But for me that puts a big question mark over the solution suggested in the heading of the article, and the question is tentatively raised in the concluding paragraph:

Wale suggested at the Barometer’s launch that some of the early impetus around the notion of “reconciliation” itself is flagging. “During 1994 and the transition, people did a lot of work around citizen awareness of reconciliation,” she said. “There’s a bit of apathy now. I think that we still need to do that work of consciousness-raising on what the past means in the present, across race groups.”

The notion of “reconciliation” has been a rather ambiguous one for a long time, going back a long time before 1994. When people pointed out that apartheid was unjust, and that we needed therefore to struggle for justice, there were always some who thought that justice was too harsh, and that we should couple it with “reconciliation”. I’ve said quite a lot about that in another post, so I won’t repeat it all here.

I think that it is probably a good thing that the early impetus given to “reconciliation” is flagging, because there has been a lot of reconciliation, and reconciliation is not necessarily what is most urgently needed.

Though there is indeed a correlation between class and race, and most of the poorest people in the country are black, trying to shift the emphasis back on to race and reconciliation, as the article in the Daily Maverick does, could lead to people looking for the wrong solutions in the wrong places. By saying it’s still a racial thing, it is all to easy to think that if some government policy or programme is designed to benefit black people, it will therefore benefit the poor, because the majority of the poor are black. But that does not necessarily work like that. Most of the BEE programmes have not been Black Economic Empowerment, but Black Elite Enrichment.

And this can be seen in some parts of the article itself.

For the last 20 years the majority of white children have enjoyed a huge privilege that the majority of black children have not — going to school with children of other races. And I suspect that this is one of the factors that has led to race dropping to fourth place as the most divisive issue, with income disparity being number 1.

This does not mean that whites don’t need to change their attitudes — the survey found that “Almost 40% of white South Africans surveyed disagreed with the statement: The Apartheid government wrongly oppressed the majority of South Africans.”

But the majority of black children do not have the opportunity to meet children of other races at school. Twenty years after the end of apartheid, in most schools in the country, all the teachers, and all the pupils are black. And those are also the schools of the poor, in the poorest areas areas of the city, and the poorest rural areas. Those are the schools with the poorest equipment and other facilities.

Is their biggest need reconciliation?

And who or what do they need to be reconciled to?

I suspect that their biggest enemy is poverty; but poverty is not really what they need to be reconciled to.

The ANC came to power in 1994 with the slogan “the people shall govern” still fresh in the minds of the electorate.

But today in South Africa, as in the rest of the world, it is the 1% who govern.

December 2, 2013

Do you visit Romania when you’re bored?

One of the puzzling things about blogging is which posts seem to catch people’s attention, and which posts people read most.

Today the post that got most readers was Visitors from Romania. It’s been the most popular post of the last week. I posted that at the beginning of the year when there seemed to be an extraordinary number of visitors from Romania. At the time I wondered if it might be because the foundation stone of the new Romanian parish in Midrand was to be laid that week. But no, that got much fewer visitors, from Romania or anywhere else.

Today the post that got most readers was Visitors from Romania. It’s been the most popular post of the last week. I posted that at the beginning of the year when there seemed to be an extraordinary number of visitors from Romania. At the time I wondered if it might be because the foundation stone of the new Romanian parish in Midrand was to be laid that week. But no, that got much fewer visitors, from Romania or anywhere else.

But though the Visitors from Romania page got the most visitors today (so far) there doesn’t seem to be a single visitor from Romania today. So why are non-Romanians so interested in visitors from Romania?

Something similar happened a few years ago, when another blogger noticed that the most common search term that brought people to her blog was “What to do on Sunday if your bored” [sic]. To test this, I wrote a post on the topic, and it did seem to attract more visitors than other posts that I thought were more interesting. But that was using search terms, and there don’t seem to be any search terms being used that would account for the number of non-Romanians interested in visitors from Romania today.

It’s one of those blogging mysteries that will probably never be solved.

December 1, 2013

A rushing mighty wind

This morning we went to Mamelodi East, as we do on alternate Sundays, for the Hours and Readers Service at Christina Mothapo’s house. But this time we just said a few prayers, and left, because they were busy trying to clean up the house after storm damage last Thursday.

A heavy hailstorm wept through Mamelodi East, and all the old township houses with corrugated asbestos roofs had holes in the roofs, including the Mothapo house.

Christina Mothapo’s house, with plastic bags on the roof, to try to block the holes smashed through by the hailstones.

We took the Malahlela family back home, and they had had several windows smashed by the hail, and nearly every building we passed had all the windows on the south side broken by the hailstones.

Mamelodi East is a working class area, and most of the people living there have no insurance. All the people in our congregation had suffered damage to their houses from the storm. The corrugated asbsetos roofs are particularly bad. They were erected in the apartheid time, as council houses for rent, but when apartheid ended people were given the option of freehold ownership. But now asbestos is seen as unsafe as building material, so when the asbestos roof sheets are broken, they are difficult to replace, which makes life even more difficult for people living in such houses.

Christina Mothapo’s house on the inside, in the sitting room where we normally hold services, showing the holes in the roof

We ourselves didn’t escape from storm damage.

Last night there was a rushing mighty wind at about 10:00 pm, with the trees doing an energetic dance that looked quite spectacular. Suddenly there were sounds of a dog fight, right outside the window, and there was a strange dog in our garden that our dogs had pounced on. We wondered how it had got in, and assumed it had been frightened by the storm, and run away, though that that point there was little thunder and lightning, and no rain, just the wind howling in the electric wires, and making the trees dance.

This morning we discovered how the dog had got in — the wind had blown down the wall between our garden and that of the neighbours.

The wall that blew down last night

We hope that the damage to this wall, unlike the roofs and windows of the people of Mamelodi East, will be covered by insurance.

Brick wall blown down by the wind

On the way to Mamelodi we saw several other signs of the storms — mainly uprooted trees.

And when Val was taking Simon to work, there was a rather amusing sign — a Hummer stuck in the mud when it tried to cross the grass verge on to the main road instead of going around the proper way It seems that a Hummer isn’t actually an off-road vehicle, but was just made to look like one.

This Hummer, stuck outside the Botanic Gardens, didn’t get too far off road during the storms