Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 54

May 23, 2014

Goodbye Gmail, goodbye Yahoo mail

I think I signed up for Yahoo! Mail about the time it started, about 16-17 years ago. That was when the concept of webmail was relatively new, and it seemed to be a useful service, especially when travelling. Through Yahoo! Mail I was able to keep in touch with family and friends from Greece, Albania, and Italy, sending messages from Internet cafes.

Then they started trying to “improve” it, ignoring the adage “if it aint broke, don’t fix it.”

It became more complex and more difficult to use. Useful functions disappeared, and one never knew whether that was because they had hidden them or abolished them altogether, but looking for them wasted a lot of time.

Then along came Gmail.

Yahoo! Mail? Thanks, but no thanks

Seeing the mess that had been made of Yahoo! Mail, Google cut though the complexity and had an even simpler and less cluttered interface. It lacked a couple of features that Yahoo had (the ability to forward messages as attachments, for example — Gmail could only forward them as quoted text).

But now both of these pioneers of web mail seem to be in competition to make them harder to use. Instead of concentrating on improving the functionality, they have rather concentrated on the “user experience”, and this user’s experience can be summed up in one word — frustration.

They have added lots of bells and whistles, but at the same time they have removed most of the pistons and cylinders. They can do all sorts of fancy things, but getting them to send a plain and simple e-mail message is an exercise in frustration.

Last year our family web pages found a new home. They were originally hosted on Geocities, which was taken over by Yahoo and closed down So we found a new home for them where we set up our own site — khanya.org.za. And one of the facilities the host offers is an e-mail service, which includes webmail. And, oh joy, the Horde webmail editor has all the features that Yahoo! Mail had at its very best, before it sacrificed functionality to “user experience”.

The “user experience” the people at Google want you to have

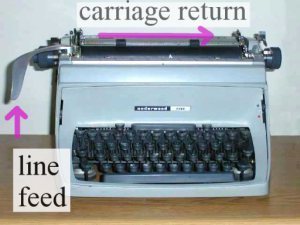

I’m not sure if the editor used in Gmail is the same as that used in Google Groups, but trying to read messages posted by members of Google Groups on Usenet has become extremely difficult, because paragraphs appear as one long line. The only way to make the messages readable to people reading them with proper newsreaders is for the writer to press the Enter key every 60-70 characters to create a new line. It seems that Google is trying to re-introduce the user experience of using a manual typewriter.

So it’s goodbye Yahoo! Mail, goodbye Gmail, hello Horde.

Now, if I’m travelling away from home, that’s what I’ll be using. We won’t be giving the address to the general public (to try to reduce spam), but just give it to family and friends.

If you have our Gmail or Yahoo! Mail address, please remove them. If you would like the new one, please ask.

Oh, and there’s another problem with Yahoo! Mail.

For about 6 months my Yahoo! Mail account did not work at all. I couldn’t log in, I couldn’t receive or send mail. During that time I asked people to use other mail addresses, so that by the time the service was restored (about 5-6 years ago) the only mail there was spam. And even today, the mail there is about 99,5% spam.

So when I look at my Yahoo! Mail mailbox (about once every 3 months or so) the main thing I do is delete the spam. The easiest way to do that is to mark all the mail as spam, and then unmark the one or two messages on the list that might not be spam. But here comes the new enhanced user experience. You can mark 50 messages as spam with one click, but trying to UNmark them doesn’t work. You click on the tick in the box but it won’t go away. Eventually the frustration (that enhanced user experience) becomes too much, and I just mark the whole lot as spam. So if you send me mail to my Yahoo address, the chances are good that it will end up being marked as spam, and then there is the possibility that the address you sent it from will end up on one or more spam black lists. If that happens to you, you can just put it down to experience — the Yahoo! enhanced user experience, of course.

May 18, 2014

Shades of darkness: a book that tells it like it was

Shades of Darkness by Jonty Driver

Shades of Darkness by Jonty Driver

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Another book that tells it like it was in the apartheid period in South Africa.

A comparison that immediately springs to mind is A dry white season by Andre Brink. In in Brink’s book there is a kind of Kafkaesque horror that builds up relentlessly as a white Afrikaans-speaking school teacher gradually discovers what lies behind the mask of the society he lives in.

Jonty Driver tells much the same kind of story, but from the perspective of an English-speaking South African. In Shades of Darkness Jamie Cathcart, a school teacher who has been living in exile in England since the 1960s, returns to South Africa in the 1980s to see his brother who is dying of cancer. His return reawakens memories of the past, lost friends and lost love. In a way the cancer that was destroying his brother’s life is an allegory of the cancer of the apartheid ideology that was eating South African society.

This book lacks the relentless build-up of horror in A dry white season, and in that sense it is more true to life. Much of the story deals with the ordinary things of life and death, health and sickness. For many white people who lived through the apartheid period, the underside of the society hardly intruded at all, and it was quite easy to ignore it and pretend that it was not there. For the protagonist of the story, however, it intrudes when some of his friends are detained by the Security Police, including one that he thought was completely a-political, and he becomes aware that he himself is under surveillance.

In some ways it is the story of my life and times, and at many points of the story I had a sort of “been there, done that” feeling. I don’t have a brother, much less one who was dying of cancer, but the kind of society that Driver describes is real; it really was like that.

It is also one of the few novels I have read where I have known the author, though I did not know him well. Jonty Driver was an acquaintance, not a friend. He was president of the National Union of South African Students (Nusas) when I was a student, so I met him at a few student gatherings in South Africa and in England, and at a friend’s wedding. But after reading this book, I feel I know him better, because in the book I think I can see the world through his eyes, and it looks quite similar in many ways to the world I saw. It’s also a human story of love and loss, joy and grief, revenge and mercy.

If you’ve never been in South Africa, don’t be put off reading it. Many people have enjoyed reading Doctor Zhivago even though they have never been to Russia, so you don’t need to have been to South Africa to enjoy reading this one.

May 5, 2014

Are printed books an endangered species?

We often read stories to the effect that printed books are an endangered species, and will soon become extinct.

But according to this article, that is very far from the truth — Data Point: People Still Like to Read a Good (Printed) Book – Digits – WSJ:

Given the news coverage, you’d think the conversion at last of Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” into lines of ones and zeroes was some kind of nail in the coffin for the printed word. One of the last holdouts finally turned.

Not quite. Of the people in the U.S. who use the Internet, 46% say they still only read books that are printed, according to data from Harris Interactive that was charted by Statista. Another 16% say they read more printed books than e-books.

I only once read an e-book all the way through.

It was just before Western Hallowe’en a couple of years ago, and the people on the Coinherence-l mailing list for discussing the works of Charles Williams naturally started to talk about Williams’s novel All Hallows Eve.

I don’t have a copy — it’s out of print — and it would be too much schlepp to get in the car and drive 10 km to get a copy from the university library, so I downloaded one from Project Gutenberg and read it on screen.[1] I like having copies of favourite books in electronic format, preferably Ascii, for purposes of quoting and reference, but not for reading.

Why bother having a copy on your own computer when you can look up any book, including obscure ones, on Google Books?

But Google Books is a snare and a delusion. You can’t copy a paragraph or even a couple of sentences for quoting, and if you cite the URL where you found it, other people more often than not can’t find it. Google Books has much promise, poor performance. Project Gutenberg beats it hands-down.

It’s not just fiction, but software manuals too.

One of the reasons I still use MS Word 97 rather than the latest version is that I got a book on it, which I read in the bath, and so learnt to use it. I’ve never seen a hardcopy book on LibreOffice, and so I’ve never used it much. I had Evernote on my computer for some years, but never really used it until I found a hardcopy book on a sale that told me how to use it. If I’d found a similar book on Microsoft’s OneNote I might have preferred that, but I didn’t, so I’ve stuck with Evernote.

Take Our Poll

Notes

[1] All Hallows Eve may have been reprinted, but I haven’t seen a copy on sale in any bookshop in South Africa since the 1960s. And even back then the only place you could buy them was in the old Vanguard Bookshop in Johannesburg, which vanished long ago.

May 3, 2014

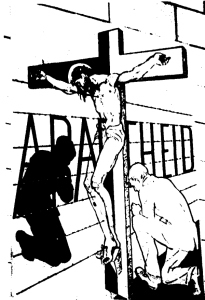

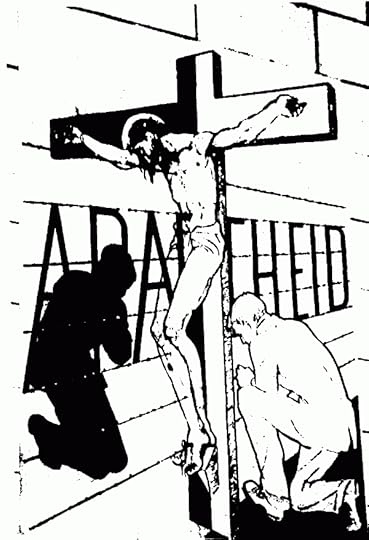

Racism in the Church

A few days ago someone posted a link on Facebook to a blog article that referred to some people recently received into the Orthodox Church who were apparently openly advocating racism: To My White Nationalist Brothers | WIT.

Only a few days ago, via the ubiquitous internet, a number of Orthodox Christians discovered that a new brother, Matthew Heimbach was welcomed into our midst, a member of an openly pro-White organization, the Traditionalist Youth Network.

The blog post has since been discussed quite widely in Orthodox internet forums, and it seems that the issue is not going to go away soon, so I thought it might be worth adding a few points.

Back in 1993 we had something similar in our parish, the Church of St Nicholas of Japan in Brixton, Johannesburg.

In the early 1990s there were a lot of new immigrants to South Africa from Eastern Europe, and several of them came to our parish because it was English-speaking (most of the others were Greek), and we included Slavonic hymns, especially when such immigrants were present.

One of these new immigrants was a young Bulgarian, and someone in the parish had helped him to find a job. Unfortunately, however, some of the people he worked with were members of the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB), an extreme right-wing white-supremacist organisation, and one Sunday after the Divine Liturgy, when we were having coffee, this young man, I’ll call him Bogdan (not his real name) was flaunting his newly-acquired AWB membership card.

I quote from what I wrote in my diary for Sunday 25 April 1993:

We went to the Divine Liturgy at Brixton, and Jethro and I were serving. At tea Bogdan told Cathy MacDonald he had joined the AWB, and an uproar ensued, with just about everyone trying to tell him he should have nothing to do with them. I said to him that joining the AWB here was like joining the Communist Party in Bulgaria and trying to bring back Stalinism. He said no, they were not like the communists, they were much closer to the Nazis. True enough, of course, but he thought that that made them better.

I said that they were Satanic, and that we should sprinkle his membership card with holy water and burn it. He denied it, saying they were Christian, and said it was all in the Bible – the sin of the Israelites was that they did not exterminate the natives in Canaan, and that the sin of the whites in South Africa was that they did not exterminate the blacks. The Australians and Americans were less sinful because they had done a better job of exterminating the natives. I showed him Revelation 7, where it said that there was a great crowd from every race, nation, people and language. And he said yes, but blacks are not people.

They really have brainwashed him, and the trouble is that they are using suckers like him to assassinate people like Chris Hani. Bogdan started quoting Andries Treurnicht, and was saying that he was a Doctor of Theology. I said he should consider two things – first that Treurnicht was not Orthodox, and second that, though he was conservative, he would never have said that blacks were not human.

This had a sequel a week later.

At the beginning of the service, when people went into the church they would take a small prosphora (offering bread) and write the names of people they wanted prayers for. These were then taken to the altar, and the priest would pray for the people listed, and for each one would put a small piece of the prosphora on the paten with the Lamb (communion bread) for each person prayed for. For those unfamiliar with this practice, it is described in more detail here and here. The small prosphora were then returned to the entrance of the church and the people who had put them there would take them, and eat them, or share them with those they had prayed for, and with others.

This is what I wrote in my diary for 2 May 1993:

We went to the Divine Liturgy at Brixton. Bogdan came, at the beginning of the service this time. There was a black guy there, from Zimbabwe. He had been there once before, and I took him to show him his way round the book. He was clutching a copy of the New World translation of the Bible, and I wondered if he was a Jehovah’s Witness. I helped him to find the scripture readings, and was struck by the poor translation. Stephen was “full of holy spirit”. The myrrh-bearing women went to the tomb to “grease” the body of Jesus, as if they were servicing a car.

I had put out a prosphora to pray for (names of various people, omitted). I got it after communion, and gave some to George, and to the black guy, and to Val and Mary. And afterwards Bogdan came up to me at tea, and wanted a Bible.

So I got him one, and he said he wanted to show me Mark 7:6: “Do not give dogs what is holy; do not throw your pearls in front of pigs; or they may trample them and turn on you and tear you to pieces.” And he said I had done something very evil in giving the prosphora to a kaffir, who is a dog, a pig, and not human. And so we went through all the things we had been through last week. I took him back into the church, and showed him the ikon of St Moses the Ethiopian, and he said he had not seen it before, but then he said such an ikon would not be found in a Greek church in South Africa.

Eventually Fr Chrysostom spoke to him, and said that he was setting himself up against the Orthodox Church, and following the teachings of heretics. When he started talking about kaffirs, Fr Chrysostom spoke to him angrily, and told him never, ever, to use that word in the church again. One thing it has done, however, is that I think it has clarified the issue for other people in the church. Some of the Russians found it incomprehensible, and said he (Bogdan) should read the Bible properly, and read it all.

Our priest, Fr Chrysostom, had been seconded to serve in our parish by the Orthodox Church in America (OCA), as there were no English-speaking priests in South Africa at that time, and Fr Chrysostom wrote to Metropolitan Theodosius of the OCA to ask for his advice on what to do about the pastoral problem posed by Bogdan. He was clearly getting his racist notions from the AWB, and not from Orthodox sources, but then was trying to recruit members of the parish to his racist cause.

A reply came from Metropolitan Theodosius in July 1993, just before Fr Chrysostom travelled overseas on a research trip. The letter did not mention Bogdan by name, but was couched in general terms, and said that if anyone advocated racism in the church, and continued to do so after being warned to desist by the priest, they should be excommunicated. I published this in our newsletter Evangelion which was read by many people in our parish, elsewhere in South Africa, and overseas.

When Fr Chrysostom returned from his overseas trip a couple of months later, he discovered, however, that some people in the parish had misunderstood Metropolitan Theodosius’s letter, and mistakenly thought that he was accusing everyone in the parish of being racist. But that is a different story.

The main point in this story is that Bogdan needed to choose between the teaching of the Orthodox Church and the teaching of the AWB, because his racist ideas came from the AWB and not from the Orthodox Church.

Another story can give a different example.

Back in the 1920s a disaffected black Episcopalian (Anglican) priest in the USA, George Alexander MacGuire, approached the Russian Orthodox bishop in America with a proposal for a black ethnic juridiction to be called the African Orthodox Church. MacGuire was aware that there was a Russian Orthodox Church, a Greek Orthodox Church, a Bulgarian Orthodox Church, and so he thought that there could also be a Black Orthodox Church. The Russian bishop explained that those national churches had come into being as a result of historical developments, but that those developments could not be elevated to a kind of theological principle, as MacGuire appeared to think.

Back in the 1920s a disaffected black Episcopalian (Anglican) priest in the USA, George Alexander MacGuire, approached the Russian Orthodox bishop in America with a proposal for a black ethnic juridiction to be called the African Orthodox Church. MacGuire was aware that there was a Russian Orthodox Church, a Greek Orthodox Church, a Bulgarian Orthodox Church, and so he thought that there could also be a Black Orthodox Church. The Russian bishop explained that those national churches had come into being as a result of historical developments, but that those developments could not be elevated to a kind of theological principle, as MacGuire appeared to think.

MacGuire eventually obtained episcopal consecration at the hands of an episcopus vagans, Rene Joseph Vilatte, and the African Orthodox Church he started eventually led to a big expansion of Orthodoxy in Africa, but I’ve told that story elsewhere in an article on Orthodox mission in tropical Africa.

There is a lot of racism and ethnocentrism to be found among Orthodox Christians, as among many other people. But that cannot be justified by the teaching of the church. It is always a sin that should be confessed.

Perhaps what we need is a clear statement on this from Orthodox bishops. I’ve heard many Orthodox bishops denounce racism individually, but there needs to be a clear statement of the teaching of the Church on this matter.

In the absence of such a statement, I’ll point to one that was made by South African Christians over 50 years ago. It was published by the South African Council of Churches, and I can see little or nothing in it that is incompatible with Orthodox theology. It was called A message to the people of South Africa and you can find a copy here.

April 27, 2014

The End of Dystopia: 20 Years of Freedom

Today is Freedom Day, and we are celebrating 20 years of freedom. It is also the second Sunday of Pascha, Thomas Sunday, when we recall St Thomas saying that he would not believe that Christ had risen until he could put his fingers into the holes in the hands of the one who was crucified.

This isn’t one of my series of Tales from Dystopia, on what life was like in South Africa under apartheid. It does not mark the end of those tales either — I may tell some more such tales, if the Spirit moves. But this is a kind of juxtaposition of memories of our first democratic election with the theme of Thomas Sunday. It was what I preached on in our house church in Atteridgeville this morning.

The first democratic election, on 27 April 1994, fell in the middle of Holy Week.

There were some attempts by right wingers to disrupt the election — some bombs went off in the middle of Johannesburg. Inkatha planned to boycott the election, and 700 people died in fighting in the lead-up to the elction. Inkatha agreed to take place at the last minute, and the ballot papers had already been printed without them, so millions of stickers had to be printed to add to the ballot papers. The white right also predicted a bloodbath, and the world media were on hand to record it. Supermarket shelves in many places were empty, as people stocked up with tinned food, fearing the worst.

Some Orthodox parishes said that their parishioners were too scared to come to the Holy Week services, especially the evening ones, and the Archbishop gave special permission for them to be held at different times, in daylight. Our parish, St Nicholas of Japan in Brixton, decided not to change the times, and as a result we had record crowds at the services, as many of those who wanted services at the usual times came to us instead of going to their home parishes.

Here are some extracts from my diary for that day.

Last night at midnight we watched on TV as the old South African flag was hauled down, and the new one raised. A new era for South Africa has really begun. The country’s first democratic election actually began yesterday, with special votes being cast by people living abroad, and by the old, the infirm and invalids. There were problems in some places, mainly logistical, in getting supplies and equipment to all the right places for people to vote. Today was the first day of voting for the rest of us. At 7:00 am we watched on TV as Nelson Mandela, the leader of the African National Congress (ANC), cast his vote in Inanda, Natal. He wanted to vote in Natal, because that is where the ANC started in 1912, and their struggle for political rights for black South Africans has therefore lasted 82 years. Inanda is also an area where there has been much political violence in recent years. There was then similar footage of Chief Gatsha Buthelezi, of the Inkatha Freedom Party, casting his vote. Both had to move around a lot to pose for photographers wanting to record the historic moment.

Then we decided it was time to go and vote. Where? On impulse we decided to go to Mamelodi, a black township 14km away[1]. So Val and I set off, accompanied by daughter Bridget toting a camera. She won’t be old enough to vote till next year, but she wasn’t planning to miss the fun. Just before 8:00 am the streets of Pretoria were absolutely dead. I’ve never seen the place so deserted. A yellow police van behind us was the only car we saw for most of the way to Mamelodi. Mamelodi had slightly more life than Pretoria. A couple of cars, and some pedestrians, but no buses or taxis. We drove through Mamelodi West, and saw no signs of activity. Then we reached Mamelodi East, and saw some cars and people, and when we got closer, some posters from the IEC (Independent Electoral Commission). We stopped, parked next to the main road, and then walked into the grounds of a school – don’t even know what it was called. There was a policeman at the gate, and a newspaper seller. We bought some papers, and joined the end of a queue just inside the gate, that disappeared round the corner of the building. People silently filed in behind us. It was very quiet, almost solemn. The queue moved slowly, and when we reached the corner of the building, we saw it stretched right down the length of the building and to the far end of the netball field beyond.

South Africa’s first democratic election 27 April; 1994. Voters queuing in Mamelodi East.

A young IEC official came to ask if everyone had identity documents of some kind – those who didn’t were directed to another school next door, where they could get temporary voter cards. He also took a look at Bridget’s T-shirt, with the slogan “Masibeke uxolo phambili” (Let us look forward to peace) on it. He decided it wasn’t party propaganda, so it was OK. Party slogans etc. were not allowed within a certain radius of polling stations. We shuffled down the length of the building, and right round the netball field, then back to another building. There was very little talking, no pushing, no shoving, no queue jumping, no impatience. We were the only whites there. Occasionally people would greet someone they knew. One thing that struck me was that four out of five voters seemed to be male. Maybe women were planning to vote at another time, or maybe there were more male voters than female ones in Mamelodi. It took about 2 hours to reach the front of the queue.

Voters queuing in Mamelodi East, 27 April 1994

Our hands were checked under ultraviolet light to see that we had not voted before. Our identity documents were checked and stamped with invisible ink, our hands were sprayed with invisible ink, and we were given ballot papers to vote with. The ballot boxes already seemed to be pretty full. It looked as though they would need new ones fairly soon. As we were leaving the school grounds, some other whites walked in – the first we had seen. They were international observers monitoring the election. We had been told of the chaos and logistical problems at some of the other 9000+ polling stations in the country, but this one in Mamelodi East was pretty slick operation. The IEC deserves to be congratulated. There was also no violence, no intimidation, no canvassing and no soliciting. There wasn’t a party worker in sight from any of the parties. As far as we could see, voting at Mamelodi was certainly free and fair. It was a solemn, somewhat awesome occasion. We had seen the future, and it works.

When we got in the car, it was 10:00 am, and we rushed to Johannesburg 100 km away for a church service at 11:00. For Orthodox Christians this is Holy Wednesday, and in many Orthodox Churches the Holy Unction (anointing of the sick) is celebrated on this day. It is long – about 2 hours – another two hours of standing in church, praying for healing. Praying not just for healing of particular ailments, but for general healing, of ourselves, of our relationships, of our country and its wounds. It seemed entirely appropriate. And after the service there was a mingled smell of both – on the back on one’s hand was the slight lemon smell of the invisible ink from the voting, and on the palm was the smell of olive oil, the oil of healing. Kyrie eleison – Gospodi pomiliu – Lord have mercy. May the Lord indeed heal our land. Masibeke uxolo phambili – May we see peace ahead.

Because of the number of people voting, the voting was extended for another couple of days, and as we went to church on Holy Thursday and Good Friday, we passed the SABC (South African Broadcasting Corporation) headquarters in Auckland Park. They had closed off half of the double-carriageway to provide parking for foreign journalists, but by Good Friday most of them had left. The expected bloodbath had failed to materialise, but was happening 4000 km away, in Rwanda.

St Nicholas Church, Brixton, Johannesburg, on Good Friday, 29 April; 1994

Twenty years later we look back on that day that for most of my life I thought I would never live to see.

And today it is Thomas Sunday, and I think about hands. The hands that St Thomas wanted to stick his fingers in the wounds of, before he would believe that Jesus had risen from the dead. Our hands as we walked out of church smelling on Holy Wednesday — the smell of freedom on one side, and the smell of healing on the other.

And there was more about hands in today’s Epistle reading:

Acts 5:12-20 (Epistle)

And through the hands of the apostles many signs and wonders were done among the people. And they were all with one accord in Solomon’s Porch.

Yet none of the rest dared join them, but the people esteemed them highly.

And believers were increasingly added to the Lord, multitudes of both men and women,

so that they brought the sick out into the streets and laid them on beds and couches, that at least the shadow of Peter passing by might fall on some of them.

Also a multitude gathered from the surrounding cities to Jerusalem, bringing sick people and those who were tormented by unclean spirits, and they were all healed.

Then the high priest rose up, and all those who were with him (which is the sect of the Sadducees), and they were filled with indignation, and laid their hands on the apostles and put them in the common prison.

But at night an angel of the Lord opened the prison doors and brought them out, and said, Go, stand in the temple and speak to the people all the words of this life.

The aposles laid hands on the sick, and they were healed. Hands of healing.

The Saducees laid hands on the aposltles and put them in prison. Hands of oppression.

Healing and freedom on the one hand, oppression on the other.

Let us speak the words of this life to the people, and use our own hands for healing and freedom, and never again for oppression.

_____

Notes

[1] In that first democratic election, the desire was to be as inclusive as possible. There was no voter’s roll, and anyone could vote anywhere they pleased. We wanted to go to Mamelodi to vote with people who had been denied the vote previously, because we thought it would be much more like the taste of freedom than the white suburbs.

In later elections there has been a voters roll, and we can now vote only at the polling station where we are registered, close to home.

April 22, 2014

Tales from Dystopia XVII: Ethnic cleansing and Christian objections to it

Fifty years ago today, on St George’s Day, 1964, Christian students at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg arranged a protest meeting against “blackspot removals”. “Blackspots” were black marks on the apartheid map showing land owned by black people in areas designated by the government for occupation by whites, and the government was dedicated to their removal by expropriating the land from the owners. Most of the occupiers of that land were peasant farmers.

The fate of black peasant farmers was not of particular interest to the overwhelmingly white student body at the university, though in that year there was also a student protest against the Bantu Laws Amendment Bill, which would make life for black people generally much more difficult. A few Christian students were aware of the ethnic cleansing that was taking place in the blackspot removals, and thought that it was a matter of Christian concern, if not of general student concern, and so organised a protest meeting.

Here is an extract from my diary for that day:

I composed a letter to the Minister of Bantu Administration and Development, about the theological objections to apartheid in general and blackspot removals in particular. I took it to Rob Hofmeyr, who agreed with it, and after lunch took it to Fr Sweet, who said it was “sound”.

John Aitchison came to see me, and we both went to see Ken Lemmon-Warde, who said he was not coming to the Ansoc meeting tonight, but was going to Durban to hear the gospel — from an evangelist called Eric Hutchings. The implication was that we didn’t have the gospel. Later he told us, when we had challenged him on that, that we had the bull by the hair on the middle of its belly, and not by its horns — whatever that means. He also said that the devil was climbing into us. John asked him if, as a Christian, he thought it was a good thing — blackspot removals, that is, and pointed out some of the advantages Ken said they had — like typhoid. Ken said it might be a good thing if they all died of typhoid, since they were all heathen anyway. We pointed out that the majority were probably Christian, and that even among the heathen, and those who did not believe in him, our Lord healed sickness.

In the evening we had the meeting — about 50 people came. Not many Christians — it probably wasn’t “spiritual” enough for them. Peta Conradie, Bridget Bailey, John Aitchison and Richard Thatcher were there from Ansoc. Mike and Wally sent their apologies. Ken Lemmon-Warde had gone to hear “the gospel” — according to St Eric. Peter Brown gave the facts about blackspot removals — a rough estimate of the number of people who would be affected, cases in which compensation was inadequate. In some cases owners had probably been paid less than half the value of their property. In Kumalosville land was expropriated and compensation was offered at R42.00 an acre. In exchange they were offered a free half-acre at Hobsland, with the option of buying another half acre for R110.00.

“The leaders of Judah have become like common land-thieves. I will vent my wrath on them like a flood. Ephraim is in agony and crushed in judgment, because his mind was bent on following false gods. That is why I am the moth which rots the fabric of Ephraim, I am the dry rot which ruins the house of Judah.”

Calvin Cook, the minister from the Presbyterian Church, spoke, giving theological reasons why we should oppose the removals. Then we voted on a resolution to be sent to the Minister of Bantu Administration and Development. About 45 were in favour of it and four were against, one of whom, Pat Erwin, stayed to argue afterwards.

The objections raised by some Christians to the holding of such a meeting, namely that it was secular and political rather than “spiritual” or “evangelical” was typical of the response of some white Christians to apartheid — that we should not be concerned about it, but rather be concerned with “the gospel”, which they defined rather narrowly.

The objection that those being removed were all heathen was typical of white ignorance at the time (I won’t say anything more about the callousness of the remark that it would be a good thing if they all died of typhoid).

John Lambert and other historians have since made a study of the black peasants who were the main victims of ethnic cleansing in Natal in the 1960s and 1970s, and has shown that they were mostly a group they called “the kholwa” (from Zulu amakholwa, “believers”). This group arose because life was uncomfortable for Christian believers under the Zulu monarchs and African chiefs, so they bought land that white colonists in Natal had appropriated, and settled there as peasant farmers and, in the 19th century, as transport riders.

Lambert has shown that they were much more efficient farmers whan most whites, and that much of the fresh produce sold in cities like Durban and Pietermaritzburg, especially milk and vegetables, was produced by the kholwa. Immigrant white farmers could not compete in efficiency, and so in the late colonial period in Natal tried to induce the colonial government to introduce laws that would favour them and discriminate against black farmers. This process is detailed in Lambert’s thesis (see reference below).

It is estimated that in the apartheid era some 3-4 million people (most of them black) were ethnically cleansed to clean up the apartheid map, and the kholwa of Natal were among the main victims of this process.

It is estimated that in the apartheid era some 3-4 million people (most of them black) were ethnically cleansed to clean up the apartheid map, and the kholwa of Natal were among the main victims of this process.

This now has repercussions today, in the talk of land restitution.

The National Party government made enormous profits by expropriating land from black people with inadequate compensation and selling it to white people at much higher prices. Now there are moves to restore the land that was taken, but it brings new difficulties with it, because the people from whom the land was taken are long dead, and so the compensation will be given to their descendants. But just because your grandfather was a good and efficient farmer does not mean that you will be, and in many cases where the land has been returned, the descendants of the dispossessed owners resort to “people farming” becoming absentee landlords letting the land to landless people who work in the cities, and the land is not farmed.

I do not know what the solution to this problem is, but this is just one of the ways in which apartheid, though it officially died 20 years ago, still exercises a malign influence in the present as its chickens come home to roost.

This post is one of a series of Tales from Dystopia, describing what life was like in the apartheid era in South Africa.

___

Notes and References

Etherington, N.A. 1971. The rise of the kholwa in Southeast Africa. Yale University: Ph.D. thesis.

Hayes, Stephen. Was material self-interest more important than religious conviction to the Kholwa. Available online here.

Lambert, John. Africans in Natal, 1880-1899 : continuity, change and crisis in a rural society. (1986, Unpublished PhD thesis).

April 18, 2014

Centenary of St Alphege’s Church, Pietermaritzburg

Today is the centenary of St Alphege’s Anglican Church in Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg. On 19 April, 1914, a little wood and iron church was dedicated to St Alphege, a former Archbishop of Canterbury.

I wasn’t around 100 years ago, but I was at St Alphege’s 50 years ago, when the parish was celebrating its 50th anniversary. I was a student at what was then the University of Natal (now the University of KwaZulu-Natal, UKZN) and the university campus was in the parish, so St Alphege’s was the church attended by most Anglican students.

Revd Mervyn Sweet, Vicar of St Alphege’s in 1964.

When I went to the university in 1963 the vicar was the Revd Mervyn Sweet, and there were two assistant priests, Graham Povall and Richard Kraft (who later became Bishop of Pretoria). St Alphege’s was a very lively and active parish in those days. At a parish mission held in 1963 John Davies, the Anglican chaplain at Wits University, taught about the ideas of the oparish meeting and house churches, which were adopted by the parish, helped to build the sense of community in the parish.

At the end of 1963 Richard Kraft left to go to St Chad’s in the Ladysmith distict.

The old wood-and-iron church was still used as a hall, and the new brick church had been completed 9 years previously in 1955, but the parish was growing rapidly, and more housing was being built in the area, so there was much discussion about finding a new piece of land and building a new church. The parish councilo produced a map showing where parishioners lived, and they were negotiating to buy a more central site. The main one of interest is now occupied by the Ridge School (one parish councillor declared a conflict of interest — he worked for the education department and said they also had an eye on the site). In the end nothing came of the plans, and eventually a new church was built on the old site.

In 1964 the main Sunday Eucharist was at 7:00 am, and was Sung. There was another one at 8:30, said, though with hymns, attended by people who liked to sleep late. There was Evensong in Zulu at 3:00 pm, and in English at 7:00 pm

There was some dissatisfaction in the parish when the 1964 diocesan synod of the Anglican Diocese of Natal decided to change the title of the incumbents of parishes from “vicar” to “rector”, and at the same time decided to hive off the Zulu-speaking members and make them an “outstation” of St Mark’s Church in downtown Pietermaritzburg. This, in the view of St Alphege’s parish council, was creating an ecclesiastical Bantustan.

St Alphege’s Church, Scottsville, Pietermaritzburtg, 1964. The original wood-and-iron church, then used as a hall, can be seen on the left.

One of the things that St Alphege’s was known for in 1964 was its parish policy on baptism. There were no private baptisms arranged secretly with the priest. Most baptisms took place at the Sunday Eucharist, where everyone could see who was being received into the church and welcome them.

St Alphege’s Church, October 1964 (the jacarandas were blooming)

On this day 50 years ago, I was admitted as a parish councillor — the parish had decided at the annual vestry meeting, that there should be a student representative on tnhey parish council, and for that year, I was it.

St Alphege’s Church, Pietermaritzburg, 1964. The congregation were leaving after a confirmation service, and some of the candidates are in the front row.

Several of the other parish councillors were associated with the university as lecturers, and Roger Raab and Tony Eagle of the Physics Department were particularly active in the parish.

Interior of St Alphege’s Church in the 1960s

I don’t know if St Alphege’s parish are doing anything to celebrate their centenary this year, but if they are, my greetings to them on St Alphege’s day.

The 1960s were troubled times in South Africa, as apartheid was being applied more rigidly, and civil liberties were in decline.

St Alphege also lived in troubled times. England was being raided by Danish freebooters, and St Alphege was captured by them, and mocked, and eventually beaten to death with the bones of the cattle stolen from his flock. Some martyrs were stoned to death, St Alphege was boned to death.

I have seen his tomb in Canterbury cathedral in Enbland, and it has the inscription, “He who dies for truth and justice dies for Christ.” I good nthing to remember in South Africa of the 1960s.

April 8, 2014

Kitchen Boy: authentic book, phony funeral

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

J.J. Kitching (known as “Kitchen Boy”) is a war hero, and a famous Springbok rugby player, so when he dies at the age of 81, his funeral is a significant occasion. The action of the story takes place in the lead-up to his death and the funeral itself, and the memories of him that are prompted in the minds of his family, friends, and others who knew him.

In his final illness he shares some of his war-time memories with his grandson, Sam. Different people come to his funeral, and even his close family are sometimes surprised at the range of his contacts and acquaintances, from the homeless philosopher who lived in a culvert, to the teetotaller manager of a hotel chain who was a customer of the brewery where he worked until he retired.

I’d read a couple of other books by Jenny Hobbs before, and bought this one becazuse I was impressed by them, and their authenticity to place and time. Thoughts in a makeshift mortuary had in some ways a similar theme to this one, the parents of a freedom-fighter who has been killed by the police, as they keep vigil over the body of a child they hardly knew, thoughts prompted by death.

When I began reading this one, I was very impressed at the apparent authenticity. Most of the novels we read in South Africa are published overseas, and are set in far-away places, so one often doesn’t know whether the descriotions are authentic or not.

But this one is set in Durban and Zululand, places where I have lived. The description of World War II soldiers and returning POWs wandering round Durban on arriving home sets the scene amazingly well. The description of Twiggie’s Pie Cart in Market Square in Pietermaritzburg revived memories of 50 years ago.

I recalled my uncle returning from the War. I was four years old and we stood on Salisbury Island and watched the flying boat come in dropping over the harbour entrance, landing on the bay. Many of my friends had fathers who had fought in the war. And we also had several uncles who had fought in the war. It was part of growing up. So the memories of J.J. Kitching, and his friends’ memories of him, were part of my growing up, and also part of the family history we have explored more recently.

My wife Val’s father would never spoeak about his wartime experiences, until one day we pleaded with him to tell us the story of “Shit in Italy”. He was captured at Tobruk and kept in a prison camp in Italy, from which he escaped. I wish we had had a tape recorder to record it, because we have now forgotten many of the details, but like the grandson Sam in the book, we were fascinated by the story.

Most of the memories are stirred and described during the funeral service, but that is where the story falls apart. The rugby players, young and old, are authentic. The ex-servicement, the MOTHs (Memorable Order of Tin Hats) are authentic. The homeless philososopher in the culvert may be stretching things a bit, but is plausible. But then the author has to go and spoil it all by introducing an altogether phony caricature of an Anglican bishop. The bishop is not an incidental character, because the funeral service is the setting for much of the book.

The funeral takes place in our time, no more than five years ago, but just about every detail rings false. I’m not familiar with the current Anglican funeral service, and haven’t been able to find out much since I started reading the book, but if I were writing a book that revolved around a funeral service, I’d do a lot more research than Jenny Hobbs appears to have done. The words of the service swing from Elizabethan to modern English. I once knew an Anglican bishop of Natal who might have entertained ambitious thoughts like the fictional bishop in the book, but he retired forty (40) years ago, and what we are presented with is a caricature from the 1950s, or even the 1920s, in a story set in about 2010. It’s OK to have a fictitious cathedral in a real city for the sake of the story. But it’s a pity that when there seems to have been so much research into some of the historical details (like the diets of prisoners in German POW camps), there has been so little into the hub that the story revolves around. Anglican bishops in South Africa are never referred to as “His Grace”, for one thing, and and there are numeous other bogus details.

Forty years ago I was present at quite a number of Anglican funerals in Durban, and even back then they were none of them like this. Sometimes they were pathetic — five MOTHs bidding farewell to a dead comrade, asking to play the Last Post, and one of them pulling out a tinny little portable tape recorder to play it. But nothing as phony as the one in this book. More recently, in about the same time frame as that of the book, I attended the civic funeral in Pretoria of Nico Smith, which had all sorts of military and civic dignitaries present and speaking. It wasn’t Anglican, but it gives and idea of how such things are done.

When I began reading the book, I thought I’d give it four or five stars, but the more I read, the more the rating dropped.

March 31, 2014

Farewell to Father Pantelejmon

Yesterday we went to the monastery of the Descent of the Holy Spirit for a farewell party for Father Pantelejmon (Jovanovic), who was leaving South Africa after serving for 11 years as the Rector of the Church of St Thomas the Apostle in Sunninghill Park in northern Johannesburg.

I first met Fr Pantelejmon when I went to Vespers at St Thomas’s on 15 March 2003, soon after he had arrived in the parish. We occasionally went there for Vespers as it was for a long time the closest parish to where we live that has Saturday-evening Vespers, but it was usually poorly attended, often only by the priest and his wife. This time there were 10 people present, and Fr Pantelejmon, a young priest, was encouraging the people to sing.

Fr Elias, Fr Pantelejmon & Deacon Stephen at the farewell party for Father Pantelejmon at the Descent of the Holy Spirit monastery in Gerardville

About 10 days later I visited the church again. I was taking an overseas visitor to the bishop’s office in Johannesburg, and took him past some of the other churches to show him the variety of parishes in our diocese — the Greek parish of the Annunciation in Pretoria, the Russian parish of St Sergius in Midrand, and the Serbian parish of St Thomas in Sunninghill. We arrived at St Thomas’s as they were about to start a Requiem Service for those who had been killed in the Nato bombing of Yugoslavia four years previously, and Fr Pantelejmon invited us to stay for it. There were only three other people there, all members of an immigrant family recently arrived from Serbia, who told us afterwards that Fr Pantelejmon had been in a monastery since he was 22, close to God, and was having a rather difficult time with the very secularised Serbian community in Johannesburg. Fr Pantelejmon asked me to write some articles on mission for his parish magazine, which I later did.

Father Pantelejmon produced the best parish magazine in the diocese, in Serbian and English, lavishly illustrated, with news of the church, and teaching, and it was in itself an instrument of mission and evangelism. Through this and other means he built up a core of spiritual people in the parish, who took their Christian faith seriousdly. He encouraged them to take an interest in mission too. Unlike some clergy, who simply stick to their parishes, he always tried to attend diocesan clergy meetings, and tried to visit other parishes.

Fr Pantelejmon with members of the parish of St Thomas’s in Sunninghill who came to say goodbye to him at the monastery at Gerardville

When, in 2004, as a result of the funeral of Fr Simon Thamaga, a group of people in Tembisa expressed an interest in Orthodoxy, and with the blessing of the then Archbishop Seraphim we began holding services there and in nearby Klipfontein View, Fr Pantelejmon, as the priest of the nearest parish church to Tembisa, was very supportive, and the first group of people from there were baptised at St Thomas’s, with parishioners of St Thomas’s as their godparents.

Sometimes Fr Pantelejmon was joined by other monks from Serbia, which almost turned St Thomas’s Rectory into a skete, and when there were two priests it was easier for one of them to become involved in mission outreach, and so they helped, especially in Tembisa and Mamelodi.

Fr Pantelejmon and Fr Spiridon spoke at a gathering on youth day in 2006, telling the young people how they had had a monastic vocation after growing up in an atheistic communist society. And in December 2006 Fr Naum, another monk, spoke at a diocesan youth conference, with Fr Pantelejmon translating. I rather hoped that this might encourage some of the young people to consider monastic vocations themselves, but that hasn’t happened yet. There have been several attempts to start monasteries in South Africa, but as soon as one monk comes, and is joined by another, the first one leaves, or dies, or is ordained and sent to be a parish priest somewhere, and the whole thing fizzles out.

Over the years we got to know Fr Pantelejmon quite well, and St Thomas’s became a kind of second home for us. Because it was between Johannesburg and Pretoria, it was a good central meeting place to plan activities such as the youth conference, or mission out reach in various places.

Exery year in October, at their patronal festival, a visting bishop came from Serbia, and all clergy and parishes in the diocese were invited to join in. The local Archbishop was usually present, and there was often some special teaching from the visiting bishop.

Our family had adopted the Serbian custom of Slava, which we thought especially suitable for Africa, and Fr Pantelejmon sometimes came to our Slava, and helped us to make sure we did it the right way. One especially memorable one was in 2009, when it fell at a weekend, and we had it at St Nicholas Church, Brixton, after Vespers. You can read about it (and see pictures) here: Vespers and Slava.

Ather Pantelejmon also arranged for a mission society in Serbia to undertake the printing of Reader’s Service books in Zulu and English, an enormously useful resource for our mission congregations.

Now Father Pantelejmon has been recalled by the Patriarch of Serbia, and yesterday quite a large crowd from his old parish of St Thomas’sm turned out for a farewell party for him after the Divine Liturgy at the Monastery of the Descent of the Holy Spirit at Gerardville, west of Pretoria. It was quite impressive, because these are some of the people whose lives he has touched in his 11 years in South Africa, and who have become more spiritual as a result, so his 11 years have certainly not been wasted.

He does not know what will happen to him next, and will have to wait till he hears from the Patriarch of Belgrade about that. Perhaps he will return to his home monastery at Black River and spend some time there, and perhaps that is good for a monk who has spent a long time as a parish priest. But I have a niggling hope that he will get a blessing to return to South Africa, not as a parish priest, but as a monk, and that he will get a blessing from our bishop to bring four or five other monks with him, in the hope that they can reach critical mass, and that Orthodox monasticism will take off and grow in Southern Africa. In 11 years Father Pantelejmon has learnt quite a bit about South African life and culture, and that could make it easier for other monks from elsewhere to settle in.

March 21, 2014

Good Story, Bad Story

The ANC have kicked off their election campaign by saying that they have a good story to tell. And in many ways they do. When I compare South Africa today with South Africa 30 years ago, I would far rather live in the South Africa of today than be back under the rule of P.W. Botha’s securocrats. That is a good story, and it is a story worth telling.

But when we come to voting for the people who will represent us in parliament and provincial councils, we are not thinking about what happened 30 years ago, but rather what will be happening in the next five years.

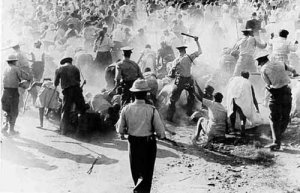

Sharpeville 1960

Yes, much that was broken has been fixed, but there is also much that was broken that is still broken, and on this Human Rights Day, when we recall the Sharpeville Massacre, and recall the Marikana Massacre of a couple of years ago, we can see that there is also a bad story, a story of broken promises, of failures in transformation.

There are things that still nneed to be fixed, as this article makes clear: Fish rot from the head | openDemocracy:

Torture is routine practice in South Africa’s police stations and prisons. A lineage of impunity, traced from apartheid, has meant de facto immunity for perpetrators. With South Africa celebrating its ‘Human Rights Day’ this weekend, the shocking reality behind its prison walls must be a central focus.

Much the “good story” took place in the first few years after the advent of our democracy in 1994, but there hasn’t been much since 2004. Most of the people who made the good story happen are retired or dead.

Marikana 2012

Twenty-five years ago I was working at the University of South Africa (Unisa), and the university was a microcosm of South Africa. The things that were most wrong with the country were also the things that were most wrong with the university. The three departments in the country that were worst were policing, health and education. And the worst courses in the university were Police Science, Nursing Science and those produced by the Education Faculty. But even after 1994, there was little effort to transform them.

At that point what was needed was a massive effort to train new teachers in new ways, and to retrain old ones. New policemen needed to be trained with different models of policing, to fit the vision of a new South Africa. But this did not happen. The old culture was perpetuated, with the results that we see today.