Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 51

December 20, 2014

Christianity, sin and morality

There is a controversy about Christianity and morality in the Orthodox blogosphere right now. It seems to have started with a blog post by Fr Stephen Freeman, Sin is not a moral problem, and to have escalated from there, though I may be wrong about that. The most recent post in the controversy that I have found is Fr Stephen’s Why morality is not Christian, where he answers his critics.

I’m not writing this with the intention of entering that particular controversy, but rather to apply an Orthodox take on morality to the question of “moral regeneration” in South Africa, which was all the rage a few years ago, but seems to have dropped out of sight recently.

One of the books I have found useful is The freedom of morality by Christos Yannaras. The notion of Christianity being closely tied to morality has been strong in Western theology, and led to the dominance of the “satisfaction” theory of the atonement developed by Anselm of Canterbury and later elaborated by Calvin of Geneva. Yannaras says that the satisfaction theory:

… was first formulated by Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109), drawing mainly on Tertullian: man’s sin is a disturbance in the divine ‘order of justice,’ and at the same time an affront to God’s honor and majesty. The greatness of the guilt for this disturbance and this affront is measured according to the dignity of Him who is affronted; so God’s infinite majesty and justice require an infinite recompense by way of expiation. Man, limited as he is, could not possibly provide such an infinite recompense, even if the whole of mankind were to be sacrificed to satisfy divine justice. Therefore God himself undertook to pay, in the person of His Son, the infinite ransom for the satisfaction of his justice. Christ was punished with death on the Cross to make atonement for sinful mankind.

As I have noted elsewhere, in this approach sin is seen primarily as something that God punishes us for, rather than as something that God rescues us from, and I think that is similar to the point that Fr Stephen Freeman is making.

I may be mistaken, but it seems to me that the controversy that has arisen over Fr Stephen Freeman’s articles is mainly in North America, and one of the critiques was written by Dylan Pahman, who is a research associate at the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion & Liberty, where he serves as assistant editor of the Journal of Markets & Morality. Now just a glance at the web page of the Acton Institute fills me with misgivings, and whatever it is, it is not Orthodox. I’m not sure that Lord Acton (the 19th-century Roman Catholic liberal historian, for whom it seems to be named) would altogether approve either.

I may be reading too much into this, but I think that Christos Yannaras had these trends in mind when he wrote (1984:131):

Going by the example of America and the pietistic basis of the ‘gospel of wealth’ that took shape there, one might venture to make a further assertion. The whole of mankind lives today in the trap of a lethal threat created by the polarization of two provenly immoral moralistic systems, and the constant expectation of a confrontation between them in war, perhaps nuclear war. On the one side is the pietistic individualism of the capitalist camp, and on the other the moralistic collectivism of the marxist dreams of ‘universal happiness.’ At least the latter refuses to cloak its aims under the forged title of Christian, while the name of Christianity continues to be blackened in the sloganizing of even the foulest dictatorships which support the workings of the capitalist system, upholding the pietistic ideal of individual ‘merit’.

When Yannaras wrote that the Cold War was still going strong, and since then the neoliberal ideology has strengthened while the Marxist one has weakened. The Bolsheviks attacked Orthodoxy mainly from without. They distanced themselves from it, and tried to exclude it from society and marginalise it. But it seems that neoliberalism is using different tactics, and is trying to infiltrate Orthodoxy, and undermine it from within.

How does any of this relate to the Moral Regeneration movement in South Africa?

Perhaps it was a response to public perceptions of moral degeneration — corruption in goverrnment in business, the high incidence of crime, and especially violent crime, in society. There is rape, domestic violence, armed robbery and other crimes, and all this seemed to suggest a need for moral regeneration. So the government, wanting to be seen to be doing the right thing, started a movement for moral regeneration.

The problem with this is that in a multicultural society it is very difficulty to get agreement on what constitutes moral and immoral behaviour. To give just one example, some people see abortion as a human right, while others see it as the denial of a human right, the right to life. In trying to find a definition of morality that everyone could agree on the Moral Regeneration movement came up with a statement so wishywashy as to be practically meaningless. This should suggest that moral regeneration is something that should be left to civil society rather than government agencies, and it is not something that the government ought to be spending lots of money on. But that should not be an excuse for immoral behaviour by people in government.

In the Orthodox Church, promoting moral regeneration might take the form of training priests in hearing confessions. A priest might ask a penitent specific questions, like “do you throw rubbish out of taxi windows?” The danger of asking such questions in a culture of what Yannaras describes as “immoral moralistic systems” is that the question might be understood as yet more moralising, and that is the danger that Fr Stephen Freeman points out. For Orthodox Christians, moral regeneration is not a goal, but it is a by-product of the new life in Christ.

In St Paul’s letters there is often a clear division. He begins by saying what God has done: transferred us from the dominion of darkness to the kingdom of his beloved Son (Col 1:13), blessed us with all spiritual blessings (Eph 1:3) . Then there is a “therefore” — because God has done all this for you, therefore you ought to live worthy of the calling by which you have been called. Morality is not an end, and it is not even a means to an end. To the extent that it is found, or ought to be found in Christians, it is a by-product of the end.

December 19, 2014

In Memoriam: Jeff Guy

It seems that I’ve reached the age when many of my contemporaries are dying, or thinking of doing so. On Tuesday I was talking to a friend who was speaking of this as the last summer, or perhaps the penultimate one. And on Wednesday I learned of the death of Jeff Guy, the historian, from friends on Facebook. I suppose that is one of the reasons I stay on Facebook, for where else would one learn of such things?

Jeff Guy, Steve Hayes & Thami Sibiya at a jam session at UKZN, Durban, 3 October 2001

I last saw Jeff Guy about 13 years ago, when he asked me to help one of his Masters’ students, Thami Sibiya, with a project. After our discussions I sat in on one of Jeff’s classes, which I enjoyed very much, and we went to a jazz session at the univerity cafeteria, which was also very enjoyable. We said we must keep in touch, which we did a bit by e-mail, and then lost touch again. So how would I have known that Jeff had died if it weren’t for Facebook, and learning about it from mutual friends?

For those who never knew him (and even for those who did) there’s an obituary here, and no doubt there will be more over the next few days, so I won’t try to compete by tryinbg to rehash his life story, but just say a few things about how I remember him.

We were fellow students at the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg (UNP as it was known in those days) in the mid-1960s, and attended the same History I and Philosophy I classes. So perhaps I could say I witnessed a great historian in the making, not that I knew it at the time, of course.

One of the most memorable things from that time was when the philosophy lecturer, a Mr Mecurio, did not turn up for a class one day. As I wrote in my diary (20 March 1964):

Mr Mercurio did not come to the philosophy lecture today. Yesterday he had talked about Hobbes’s conception of freedom as being the absence of external impediments, and discussed freedom in general. He discussed the libertarian and determinist arguments, and then said that neither could be proved, but while it is possible that we are not free, it would be illogical to assert it. To say “I am not free” would be invalid even if it were true.

So as he did not come, we continued the argument. Jeff Guy, a determinist, said, “Can you imagine an event or action that was not caused?” I think he is a bit of a Marxist, having come under the influence of Saul Bastomsky and Co, so we sat around discussing it, and trying to imagine an uncaused action or event, or the circumstances in which such a thing could take place.

I tended to the libertarian side of the argument myself, so disagreed with Jeff on that occasion, but discussions with him were never boring, even if one disagreed with him, it was always stimulating, and the class without the lecturer was more interesting, and we probably learned more from it, than if the lecturer had turned up, thanks in no small measure to Jeff Guy. And when I attended one of his history classes nearly fifty years later, there was the same spark, the same stimulation of interest in the students. Jeff Guy was not merely a historian, he was a trainer of historians, and able to stimulate in his students a love of history.

In the years in between I never saw him, though I read several of his books, and, as on the occasion of that classroom discussion, they were always interesting, even when one disagreed with him. And when we finally did meet again, it was as easy as taking up a conversation interrupted yesterday — not about determinism versis libertarianism, but about the history of Natal and Zululand.

I don’t think Thami Sibiya ever did finish his MA, or at least not on that topic. It was about an organisation called Iso loMuzi, formed at a place called Makhalafukwe in Melmoth, Zululand, in the 1980s. Since he did not publish it, I wrote up the material I gave to him, and posted it on ScribD here, if anyone is interested in reading about it. And that I wrote it up at all was probably stimulated by Jeff Guy.

So I will remember Jeff for discussions about libertianism and determinism, but even more for the simple pleasure of drinking beer and listening to jazz from the Paul Koko Quartet, and I wish we could have done that more.

December 14, 2014

What is your churchmanship?

This is a quintessentially Anglican question, and, though I’m no longer an Anglican, when a friend did a quiz on the topic on Facebook recently, I thought I would try it, just to see what the result would be.

This is what it said:

What is your Churchmanship

Final Result:

Liberal-to-Moderate Anglo-Catholic

You’re definitely Anglo-Catholic, however, unlike your Traditionalist brothers and sisters you think that the Church can lighten up a little. Female Priests and Bishops? Why Not? Welcoming place for LGBT Christians? Absolutely! Modern music in service? A few new hymns will do. Eucharist with the Priest not wearing a Chasuble? Not on your life in this place, Mister.

And I would say it is wrong, wrong, wrongity wrong.

Nearly fifty years ago I was about to study theology at St Chad’s College in Durham, which was then a recognised Anglican theological college, though not all the students were training to be Anglican clergy, and not all were studying theology. A sociology researcher, Bob Towler, came to interview me, and he interviewed all the others who were about to enter that and several other theological colleges. One of the questions he asked was What is your churchmanship?

He allowed five possible answers:

Anglo-Catholic

Prayer Book Catholic

Modern Churchman

Liberal Evangelical

Conservative Evangelical

My answer was “None of the above”.

That was not allowed, he said. It had do be one of the ones on the list.

I asked if he could put me down as an “AngloCatholic Conservative Evangelical”, but no, that was not allowed either.

He was puzzled by my response, and said that none of the other people he had interviewed had had any hesitation at all in saying what their churchmanship was. He had met a student who had previously been at St Chad’s College, Darryl Milner, who came from South Africa, and regarded him as a “Prayer Book Catholic”, and so said he would put me down as “Prayer Book Catholic” too, since I came from South Africa.

Bob Towler interviewed my cohort at various points in our career at St Chad’s (as he did with those attending other colleges), and eventually published his findings as The Fate Of The Anglican Clergy: A Sociological Study. I think he found our cohort at St Chad’s (1966-1968) quite weird, and perhaps that may have had something to do with St Chad’s being removed from the approved list of Anglican theological colleges.

Bob Towler interviewed my cohort at various points in our career at St Chad’s (as he did with those attending other colleges), and eventually published his findings as The Fate Of The Anglican Clergy: A Sociological Study. I think he found our cohort at St Chad’s (1966-1968) quite weird, and perhaps that may have had something to do with St Chad’s being removed from the approved list of Anglican theological colleges.

Towards the end of my time at St Chad’s, a fellow student and I attended a seminar on Orthodox theology for non-Orthodox theological students in April 1968. It was held at the World Council of Churches’ ecumenical study centre in Bossey, Switzerland, and ended up with Holy Week at St Sergius in Paris. It was organised by Professor Nikos Nissiotis of Athens University, and had speakers like Fr (now Bishop) John Zizioulas and several others.

In the last interview we had with Bob Towler before leaving St Chad’s I told him that I had finally decided on my churchmanship: Revolutionary Orthodox. But that too didn’t fit into the schme of his questionnaire, and perhaps it should have told me that I didn’t fit into the Anglican Church, but it took a few years more before I realised that.

In the last interview we had with Bob Towler before leaving St Chad’s I told him that I had finally decided on my churchmanship: Revolutionary Orthodox. But that too didn’t fit into the schme of his questionnaire, and perhaps it should have told me that I didn’t fit into the Anglican Church, but it took a few years more before I realised that.

You can find this stuff about my churchmanship on the About Me page of this blog.

As for the quiz, well, it just seemed to confirm that I don’t fit into the Anglican scheme of things, and probably never have. You can find it here and try it yourself.

It’s not a very good quiz, though. Some of the things it said explicitly contradicted answers I gave to some of the questions, so the basic design is flawed, but then no one takes these quizzes very seriously anyway, or do they?

December 12, 2014

Apartheid to blame for blackouts – Zuma

Johannesburg – South Africa’s energy problems were a product of apartheid and government was not to blame for the current blackouts, President Jacob Zuma said on Friday.

“The problem [is] the energy was structured racially to serve a particular race, not the majority,” Zuma told delegates at the Young Communist League’s congress in Cape Town.He said the ANC had inherited the power utility from the previous regime which had only provided electricity to the white minority.

“The problem [is] the energy was structured racially to serve a particular race, not the majority,” Zuma told delegates at the Young Communist League’s congress in Cape Town.He said the ANC had inherited the power utility from the previous regime which had only provided electricity to the white minority.

Twenty years into democracy, 11 million households had access to electricity, double the number in 1994, Zuma said in a speech prepared for delivery.

via Apartheid to blame for blackouts – Zuma | News24.

That is true, as far as it goes, but it is not the whole story.

Apartheid can be blamed for many things, but not for this.

Yes, the number of households with access to electricity has doubled since 1994, and for that we can thank the ANC government, and they did a good thing there.

But they failed to foresee that increasing the distribution of electricity required a corresponding increase of generating capacity,

Eskom foresaw this, but for ten years and more the ANC government blocked Eskom’s requests for funding to increase the generating capacity.

Apartheid is not to blame for this.

Eskom is not to blame for this.

The ANC government is to blame for this.

And President Mbeki apologised for this back in 2008.

As a Facebook friend, Wendy Landau, commented:

Actually people in the know have told me it is not Eskom’s fault but the ANC government’s who have faffed around for at least 15 years, playing around with options for new power stations, and playing around with ideas for privatization which attract in the same way as the arms deal did; it is a lack of decisive policy making and implementation by the government. Of course the Zuma culprits and their defenders will blame apartheid.

It’s an ill wind that blows nobody any good, however, and the ANC’s shortsightedness saved South Africa from an even worse disaster (that they were planning to bring about).

A Canadian aluminium-smelting firm had noticed that in South Africa electricity was cheaper than in most other places, and were negotiating to build an aluminium smelting plant in Richard’s Bay, with guaranteed cheap rates. You can be sure that the poor communities who had recently had electricity supplied to them would have their rates increased to subsidise it.

Now I learnt in school geography lessons that the most expensive thing in producing aluminium was the electricity needed for smelting it, and this was why it was big in Canada, because Canada had abundant hydro-electricity for smelting aluminium, no mattter where in the world it was mined.

Now I learnt in school geography lessons that the most expensive thing in producing aluminium was the electricity needed for smelting it, and this was why it was big in Canada, because Canada had abundant hydro-electricity for smelting aluminium, no mattter where in the world it was mined.

So why move the sdmelting operation to South Africa, which has mainly coal-fired power stations, which cause far more pollution than hydro-electricity? Because the poor suckers in Soweto would subsidise it, that’s why.

And, just in the nick of time, the espansion of electricity distribution to previously disadvantaged communities outran Eskom’s deliberately-limited supply in 2008, and there were rolling blackouts and load-shedding, so the plan for a smelting plant in Richard’s Bay was cancelled.

And only then did the ANC government wake up to the fact that if you are going to distribute electricity to more people, you need to generate more electricity. But it was too little, too late.

You can blame apartheid for many things, but you can’t blame it for this.

December 3, 2014

Of wheels and witches

I’ve just made my children’s story Of wheels and witches available as an e-book on Smashwords, where it can be downloaded in various formats.

It is probably suitable for children aged 9-12, and 25 and over.

It is probably suitable for children aged 9-12, and 25 and over.

In the story Jeffery Davidson, a schoolboy from Johannesburg, goes to spend the school holidays at a farm. There he meets Catherine, an orphan from England, Janet, a rich white farmer’s daughter, and Sipho, a poor black peasant’s grandson. They have fun riding horses and exploring caves, until they encounter an ominous symbol of a wheel, and through a witch they learn of a plot to harm Sipho’s father. In trying to find a way to warn him of the danger, they find themselves up against the power of the apartheid state, and they themselves are in danger.

It is available on Smashwords for US$ 2.99, though you can download a couple of sample chapters to see how you like it, and it might be suitable as a Christmas present for children aged 9-12.

It is possible to arrange for free copies for serious reviewers.

And reviewers, whether serious or not, are welcome to post comments below, though I would hope that you had read it first.

November 29, 2014

Patronal Feast of St Andrew’s Romanian Orthodox Church

A little less than two years ago the foundation stone of St Andrew’s Church, the first Romanian Orthodox Church in Africa, was blessed on a site in Glen Austin, Midrand. Today the congregation gathered to celebrate the Holy Apostle Andrew, and give thanks for the almost-completed temple.

St Andrew’s Church, Glen Austin

A brief doxology service was held in the open air next to the temple, to which people from other parishes in the Archdiocese of Johannesburg and Pretoria had been invited.

Clergy who attended, each representing a different nation: Dn Stephen Hayes (South African), Fr Razvan Tatu (Romanian), Fr George Cocotos (Greek) Fr Yonko (Bulgarian), Fr Daniel (Russian), Fr Isajlo (Serbian). Not in the picture was Fr Athanasius (Kenyan)

Of the clergy who attended, each one represented a different nationality, thought we weren’t able to get a photo of all of them together, as Fr Athanasius arrived a bit late and Fr Daniel had to leave a bit early.

St Andrew’s Church from the east. On the hill opposite is the largest modque in the southern hemisphere.

In the 1990s there was a visiting Romanian priest in South Africa, Fr Ioan Risnoveanu, and the first regular official priest was Fr Mihai Corpodean, who came in 2002. As there was no church building, and the Church of St Nicholas in Brixton had no priest, the bishop asked Fr Mihai to look after both communies. St Nicholas, which was intended to be multi-ethnic from the start, was happy to add Romanian to its liturgical languages, and still uses Romanian in some parts of the services. A piece of land was bought in Midrand.

Fr Rasvan, the parish priest of St Andrew’s with Fr Daniel, the priest of the neighbouring parish of St Sergius on the western side of Midrand.

In 2008 Fr Mihai left and went to New Zealand, and Fr Razvan came to take his place, and with his encouragement the parish started to build its church, which they hope will be blessed next year. In the mean time the community hold services in the Archbishop’s chapel at the Metropolis in Houghton.

The Doxology service for St Andrew

After the service lunch was served in a tent, and Fr Razvan thanked everyone who had contributed to the building of the temple and the building up of the church, including the Patriarch of Alexandria and the Archbishop of Johannesburg and Pretoria, His Eminence Metropolitan Damaskinos, without whose encouragement such progress would not have been possible.

Lunch in the tent after the sevice

Kontakion – Tone 2

Let us praise Andrew, the herald of God,

the namesake of courage,

the first-called of the Savior’s disciples

and the brother of Peter.

As he once called to his brother, he now cries out to us:

“Come, for we have found the One whom the world desires!”

November 20, 2014

A clergyman’s daughter: loneliness, nihilism and futility

George Orwell Omnibus: The Complete Novels: Animal Farm, Burmese Days, A Clergyman’s Daughter, Coming up for Air, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

George Orwell Omnibus: The Complete Novels: Animal Farm, Burmese Days, A Clergyman’s Daughter, Coming up for Air, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

The second novel of the collection I have read is A clergyman’s daughter, to which I give only three stars. Not that it’s a bad book, but it has some faults that I didn’t see in Burmese Days.

It to is set in the period between the great world wars of the 20th century, but this time in England. Dorothy Hare is the daughter of the widowed rector of a country parish in Suffolk. He takes care of the services, and she takes care of him, and the pastoral work of the parish, which keeps her busy from morning till night In addition she has to make costumes for plays, do fund raising, and keep the creditors at bay.

Eventually the strain gets too much for her, and she disappears. The parish gossip has it that she eloped with a neighbour, but she finds herself in London suffering from total amnesia, with no idea of her identity. She falls in with some people who are going hop-picking in Kent and loses herself in the rather mindless work, which Orwell describes in great detail. When the season is over she takes her meagre earnings back to London, and looks for a job, without success. Her memory gradually returns, but having no money she becomes one of the homeless street people of London.

Orwell is clearly drawing on his own experiences in describing this, as he did in another book, Down and out in Paris and London. Eventually Dorothy gets a job in a private school, which exhibits all the worst features of education. Dorothy tries to make lke learning more interesting for the children, but is thwarted by the proprietor of the school, whose sole aim is to make money.

One of the things I liked about the book was Orwell’s power of description, and in some ways he described my experience too. I once attended a private school, not as bad as the one in the book, to be sure, but there were certain similarities. It was Mountain Lodge Preparatory School in Magaliesberg, and, like the one in A clergyman’s daughter, it had a proprietor, a Mr Burnford, who did not teach, but rejoiced in the title of Bursar. I was there for three years, and each year the school had a different headmaster. Unlike the one in the book, however, the teachers were allowed to try to make learning interesting, all except one, the Afrikaans teacher, a Mrs Barr, whose authoritarianism led to two strikes among the pupils. When I was 11 the school closed, and Mr Burnford scarpered. There were all sorts of rumours, but we never did hear what really happened.

And Dorothy Hare, working at the school was friendless. Orwell describes this as follows:

There is perhaps no quarter of the inhabited world where one can be quite so completely alone as in the London suburbs. In a big town the thong and bustle at least give one the illusion of companionship, and in the country everyone is interested in everyone else — too much so, indeed. But in places like Southbridge, if you have no family and no home to call your own, you could spend half a lifetime without making a friend.

That was Dorothy’s experience in the book, and it was mine for 8 months in 1966, when I lived in a dingy bed-sit in Streatham, and worked at Brixton bus garage as a bus driver for London Transport. There were some South African friends I visited very o9ccasionally, but they were a long way away, and that part of the book particularly resonated with me.

But there was also a flaw in it. Orwell is trying to do a Dickens, and the school he describes is a 20th-century female equivalent of Dotheboys Hall. But his diatribe against private schools is a bit over the top, and becomes too didactic, and that is the biggest weakness of the book. Admittedly it is only a couple of paragraphs here and there, and nothing like the 70-odd pages of John Galt’s speech in Ayn Rand’s Atlas shrugged. But it remeinded me with a jolt that true art cannot be propaganda, and propaganda canno0t be art. Orwell seems to change gears from novelist to pamphleteer.

Not that I disagree with him in the point he makes — there are plenty of private schools like the one he describes in South Africa today, though the government has tried to vet them and set standards through the South African Qualifications Authority.

Dickens could get away with that kind of novel, but I’m not sure that Orwell can. Orwell moves Dorothy a bit to conveniently from one social problem to another so he can write about it in novel form. It’s good, but it doesn’t quite come off as it does with Dickens. Nevertheless, if you want to read about zemblanity in education, it’s worth a read.

November 13, 2014

Burmese Days: the ugly face of colonialism

George Orwell Omnibus: The Complete Novels: Animal Farm, Burmese Days, A Clergyman’s Daughter, Coming up for Air, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

George Orwell Omnibus: The Complete Novels: Animal Farm, Burmese Days, A Clergyman’s Daughter, Coming up for Air, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Since this is a collection of novels, I’ll comment on each one separately as I read it, here on my blog, and when I’ve done with all of them may add some comments on the collected works on the Good Reads site. I begin with Burmese Days, because that was the first one in the collection that I hadn’t read, and it was one I had not even heard of.

I’d read Animal Farm and 1984 when I was young. They were well known. but Burmese Days I had never heard of. I suppose it was because I read the first two in the time of the Cold War, and Animal Farm with its expression of Orwell’s disillusionment with Bolshevism seemed very relevant at the time. 1984 was more chilling, and even more relevant in South Africa, with its theme of creeping totalitarianism. I read it at the time when the National Party was using increasingly totalitarian methods to tighten its grip on every aspect of South African sociaty, so many of us were amazed that the book was not banned since far more innocuous books had been banned, but this one remained freely available.

But Burmese Days is set in the halcyon days of British colonialism, between the two world wars, when the entirce colonial structure depended on the prestige of the white man, and it was above all necessary to keep the natives in their place. In 1926, the time in which the story is set, Burma was administereed as part of the Indian Empire. White men were gods, and it was this semi-divine status that enabled them to rule. One might say that never in the field of human government have so many been ruled by so few.

The gods, of course, had feet of clay, and what Orwell did for Bolshevism in Animal Farm he did for British colonialism in Burmese Days. No wonder one never heard of the book in the 1960s, when the empire was crumbling, and the white man’s prestige had gone. Today there is much talk of post-colonialism, and I think that if post-colonialism is to mean anything, then this book is an essentiual introduction, to get something of the flavour of colonialism itself.

I think in many ways it is quite a brilliant novel. In the first few chapters Orwell sets the scene, both physical– the sights and sounds and smells of Burma — and spiritual, the values of the colonial rulers, and their interactions with the natives. It is also a love story, not in the romantic Barbara Cartland sense, but in a much more real-life way.

Something of the atmosphere of the story was something I had caught glimpses of in my youth. When I was twelve years old I went to stay with a friend at the sugar experiment station in Mount Edgecombe in Natal, and there was a club there that we went to occasionally, for film shows, and occasional dinners. It was redolent with the atmosphere of colonialism, buffalo heads on the walls, ceiling fans lazily turning, chairs with the corners that stuck out between your legs, white table cloths, heavy silver cultery, starched table napkins, and obsequious Indian waiters. The club in the book, in the small village of Kyauktada in Upper Burma, isn’t nearly as posh as that, but it is similar in that it is the centre of the social life of the Europeans in the village.

If you want to be post-colonial, read this book. It gives the essential flavour of what post-colonialism is post. And it’s a good read.

October 19, 2014

Two visitors from the USA

This weekend there were two visitors from the USA at church events we attended.

The first was the patronal feast of St Thomas’s Serbian Orthodox Church in Sunninghill, which was attended by Bishop Mitrophan from the USA, and several clergy from nearby parishes. We were a bit late for Vespers, having got the time wrong.

Vespers and Litiya at the Patronal Feast of St Thomas’s, Sunninghill. The parish priest, Fr Isailo, censing the five loaves

Bishop Mitrophan is Professor of New Testament at the St. Sava School of Theology in Libertyville, Illinois, USA. After Vespers the congregation had supper in the church hall, while the parish choir sang Serbian folk songs, and then Bishop Mirtophan briefly addressed the people.

Bishop Mitrophan at the patronal feast of St Thomas’s Church, with, in the right of the picture, Fr Razvan Tatu, of St Andrew’s Romanian parish in Midrand

Bishop Mitrophan studied in Romania, and has translated several Romanian theological works into Serbian, and among the clergy who attended the celebrations was Fr Razvan Tatu of St Andrew’s Romanian parish in Midrand so they were able to converse in Romanian.

Supper at the St Thomas’s patronal festival

This morning, Sunday, we had another visitor, in more humble circumstances.

Kaycie (Xenia) Simmons, a lay missionary from California, who is working in our diocese for a year, came on the train from Johannesburg to visit our small mission congregation in Mamelodi East. We used to meet in a school classroom, but when they put up the rent to an unaffordable level, we started meeting in the houses of parishioners.

As usual, we had the Hours and Readers Service (Obednitsa), and, in honour of the visitor, a rather sumptuous lunch prepared by Grace Malahlela, in whose house we met.

Mamelodi congregation, Sunday 19 October, 2014

Kaycie has begun work among children in Brixton who attend St Nicholas Church there, and hopes to start something similar among the children in Mamelodi, and possibly arranging some meetings for women.

Pretoria is best, of course, at jacaranda time

The visitors arrived at a beautiful time of the year — late spring, when the jacaranda trees are blooming, and turning the steets and hills blue. We took Kaycie to see some of them, and she returned to Johannesburg in the car wehich our son Jethro helped her to buy, and has just fixed up so she can travel around for her ministry in various places.

October 6, 2014

Blessed are the crazy: Mental illness and the Christian faith

This post is part of a synchroblog[1] timed to coincide with the launch of a book, Blessed are the crazy by Sarah Griffith Lund. I’ve only just heard of the book, and don’t have a copy, so this post is in no sense a book review, but rather a few thoughts on the general theme. For more information on the book, see here.

It’s a difficult thing to write about, partly because the definition of mental illness keeps changing. What exactly is it? When I did Psychology I at university 50 years ago we did a brief survey of psychopathology, and a number of different kinds of mental illnesses were described. There were schizophrenics, paranoiacs and manic-depressives and a few other conditions mentioned, but most of the terms in my textbooks back then don’t seem to be in use today. So that makes me wonder about the social construction of mental illness — is mental illness just something in the mind of the beholder. Is it just a social construct that society imposes on people?

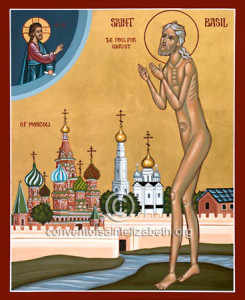

St Basil, Fool for Christ of Moscow

Back at the time that I was studying Psycho I, there was also a popular perception of psychology and related fields. There were psychologists, psychoanalysts and psychiatrists, and many people were not clear about the differences between them. Some people told me that psychologists were scientists and psychiatrists were quacks. I wasn’t sure about that. The Psychology we did at university was the study of behaviour of animals and human beings, and in part dealt with the physiology of behaviour — the senses, like vision, hearing, taste and so on. Psychiatry was a specialist field of medicine. You had to have a medical degree to practise as a psychiatrist, so I wondered about people who said that psychiatry was quackery.

Most of our textbooks for psychology was American, and one thing that made an impression on me was that they all said that believing that your telephone was tapped and that the police were reading your mail was a sign of mental illness and being out of touch with reality. But it was the textbooks that were out of touch with the reality of South Africa in 1964, and, I suspect, with the “homeland security” America of 2014, which reinforces the notion of the social construction of mental illness. Is believing that your phone may be tapped a sign of paranoia? Or is it a sign that you live in a paranoid society that is obsessed with spying on its citizens? When I looked at my government file from the apartheid era, there was frequent use of the term ‘n delikate bron (a sensitive source) , and it was clear that in many instances this referred to a little man in the post office who opened and read letters addressed to people overseas and noted the contents for the Security Police records. So who was paranoid, the citizens who thought that the State was spying on them, or the State that was actually spying on its citizens?

It gets more complicated than that. A friend of mine was a member of an interdenominational Bible study group under the auspices of the Christian Institute. One of the other members was a psychotherapist of some sort (I can’t remember if he was a psychoanalyst or a psychiatrist or something else) who was himself a mental patient in the Fort Napier Mental Hospital in Pietermaritzburg. And it turned out that he was being used by the Security Police as a spy to spy on others in the study group, and report on what they said. It seemed cruel and cynical to exploit an inmate of a mental institution in this way. A crazy society was using crazy people to spy on the sane.

This was not peculiar to South Africa, either. In the USSR the Bolsheviks incarcerated political dissidents in mental institutions on the grounds that they must be crazy not to appreciate the advantages of communist society.

But in 1964-66 I also had a real encounter with real mental illness. The priest of the Anglican parish I then belonged to, whose clergy were also chaplains to the unviersity where I studied psychology (among other things), left at the end of 1964 to return to the UK, and became rector of a parish on the outskirts of London. In South Africa he was known as a dynamic preacher, and was also instrumental in building the parish into a lively Christian community. Within a couple of months of arriving in his new parish in England he had a mental breakdown. In 1966 I went to the UK to do post-graduate study, and sometimes stayed with this priest and his family during university vacations, and he was a completely different person. He could not focus or concentrate on anything for long, and would get a bee in his bonnet about relatively unimportant matters. He became irritable, and snapped at his children. I could see that in some sense he had “lost his mind”, and a mind is a terrible thing to lose.

St Xenia, Fool for Christ of St Petersburg

So if mental illness is a social construction, it is not only a social construction. There is more to it than that. In the case of this priest it was eventually diagnosed as some kind of chemical imbalance in the brain, and he was given drugs to treat the condition, but he was never quite the same again. Of course drugs to treat such conditions are the field of psychiatry, and so I was reminded that psychiatrists were not merely quacks but that mental illness was real, and they were trying to find ways to treat it.

And that raises the question of the relationship between the “mind” and the “brain”. Nowadays, with the ubiquity of personal computers, we can make an analogy. Problems with the mind are software problems, problems of the brain are hardware problems, but they also can’t be rigidly separated. But there isn’t space to go into all that here.

Going back another 50 years from the 1964, one comes to G.K. Chesterton, who a century ago wrote about the same kind of thing, and raised the question whether Christians were mad people in a sane world, or sane people in a mad world.

And if great reasoners are often maniacal, it is equally true that maniacs are commonly great reasoners. When I was engaged in a controversy with the Clarion on the matter of free will, that able writer Mr. R.B.Suthers said that free will was lunacy, because it meant causeless actions, and the actions of a lunatic would be causeless. I do not dwell here upon the disastrous lapse in determinist logic. Obviously if any actions, even a lunatic’s, can be causeless, determinism is done for. If the chain of causation can be broken for a madman, it can be broken for a man. But my purpose is to point out something more practical. It was natural, perhaps, that a modern Marxian Socialist should not know anything about free will. But it was certainly remarkable that a modern Marxian Socialist should not know anything about lunatics. Mr. Suthers evidently did not know anything about lunatics. The last thing that can be said of a lunatic is that his actions are causeless. If any human acts may loosely be called causeless, they are the minor acts of a healthy man; whistling as he walks; slashing the grass with a stick; kicking his heels or rubbing his hands. It is the happy man who does the useless things; the sick man is not strong enough to be idle. It is exactly such careless and causeless actions that the madman could never understand; for the madman (like the determinist) generally sees too much cause in everything. The madman would read a conspiratorial significance into those empty activities. He would think that the lopping of the grass was an attack on private property. He would think that the kicking of the heels was a signal to an accomplice. If the madman could for an instant become careless, he would become sane. Every one who has had the misfortune to talk with people in the heart or on the edge of mental disorder, knows that their most sinister quality is a horrible clarity of detail; a connecting of one thing with another in a map more elaborate than a maze. If you argue with a madman, it is extremely probable that you will get the worst of it; for in many ways his mind moves all the quicker for not being delayed by the things that go with good judgment. He is not hampered by a sense of humour or by charity, or by the dumb certainties of experience. He is the more logical for losing certain sane affections. Indeed, the common phrase for insanity is in this respect a misleading one. The madman is not the man who has lost his reason. The madman is the man who has lost everything except his reason.[2]

And going back another 30 years or so, we come to Léon Bloy, who said that Christians were called to be “Pilgrims of the Absolute”, and when someone asked him whether that might endanger his mental balance, Bloy replied Pilgrims of the Absolute:

Balance? The devil take it! He has indeed taken it long ago! I am a Christian who accepts the full consequences of my Christianity. What happened at the Fall? The entire world, you understand, with everything in it, lost its balance. Why on earth should I be the one to keep mine? The world and mankind were balanced as long as they were held fast in the arms of the Absolute. What the average man means by balance is the most dangerous one-sidedness into which a man can fall… the renunciation of his heavenly birthright for the pottage of this sinful world.

And that leads me back to another synchroblog, of six years ago, which completes the circle: Blessed are the foolish — foolish are the blessed | Notes from underground

______

Notes & References

[1] A synchroblog is when a number of bloggets blog on the same general topic on the same day, and link their blog posts to each other so that you can see the same topic from various points of view.

The links to the other posts will appear here as soon as they become available, so if you don’t see them now, please return in a day or two to find some other views on this topic. There is one link that will probably not be part of this synchroblog, and yet ought to be, so if you got this far, I urge you to read it: MYSTAGOGY: The Foundations of Orthodox Psychotherapy

[2] Chesterton, G.K. 1990. Orthodoxy: the romance of faith. New York: Image. ISBN: 0-385-01536-4