Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 65

October 6, 2012

Anglicans Ablaze, Part II

For the last couple of days I’ve been attending the Anglicans Ablaze conference in Bryanston, Johannesburg, mainly as part of my research into

the history of the charismatic renewal in Southern Africa.

I’ve already blogged about it here,but here are a few more observations, and some pictures.

There was a sprinkling of old fogeys, like me, who probably remembered the charismatic renewal of the 1970s, but there was a large majority of young

people, most of whom could probably barely remember the apartheid era.

Some of those who attended the Anglicans Ablaze conference this week.

The charismatic renewal is alive and well in the Anglican Church in southern Africa, and probably more healthy than it was in the past.

Many speakers said that the old sense of renewal on the one hand and social justice on the other has been cast into the past.

Also, in the past, outside a few places like Zululand and the Eastern Cape, the charismatic renewal was perceived as predominantly white. Now it

quite clearly isn’t.

One thing that wasn’t explicitly mentioned, but was strongly implicit throughout, is that it is now unashamedly denominational. Back in the

1970s the charismatic movement was strongly ecumenical, with many speaking of the Holy Spirit breaking down barriers between denominations,

especially between Pentecostals and non-Pentecostals.

That went sour in the 1980s, with the rise of the Neopentecostal denominations, which many Pentecostals and charismatics joined. Perhaps it was ironic that the conference was held on the premises of a Neopentecostal church.

I don’t remember anything like Anglicans Ablaze happening back in the 1970s and 1980s. There were ecumenical conferences, but never denominational ones. Yes, groups like IViyo in Zululand held conferences, but they were a particular organisation, and did not include all

Anglicans.

Sisters of the Community of the Holy Name in Zululand at the Anglicans Ablaze conference

And a youth leader reported from the Provincial Youth Council, which had met shortly before, saying that the youth were not the church of tomorrow

but the church of today, and wanted teaching so they could be more certain of their Anglican identity.

Many of those who chaired plenary sessions and introduced speakers were young people, who seemed far more confident than those of earlier generations. The theme was “a generation rising up”, and indeed it is.

A speaker from Nigeria, Grace Samson-Song, pointed out some of the differences between the generation rising up and previous generations:

10 years ago only doctors and drug dealers had cell phones

when did you last see a roll of film?

green was the colour of a crayon, now it’s a lifestyle

how many of you don’t have anything made in China in your house?

reality TV – you watch TV differently

most viewers of porn on the Internet are boys aged 12-16

but social media have overtaken porn as the most popular sites

In spite of this growth in the use of social media by the generation rising up, there were very few tweets on Twitter with the #AnglicansAblaze hashtag, of the percentage of young people there matched the proportions in the populatio0n as a whole.

October 4, 2012

Anglicans Ablaze

As part of my research into the history of the charismatic renewal movement, I visited the Anglicans Ablaze conference in Bryanston today.

Iy seems that the charismatic renewal is having a revival, among Anglicans at least. It was quite strong in the 1970s, and seemed to disintegrate in the 1980s, but a couple of years ago a group of Anglican renewal organisations, including IViyo loFakazi bakaKristu (the oldest), New Wine, Soul Survivor, and Growing the Church held a joint conference and decided to work together more closely. This was the second joint conference, and it was attended by over 1000 people.

[picture]

Anglicans Ablaze conference in Bryanston, Johannesburg

It was interesting to see some of the differences from the renewal of the 1980s. Back then there were only fleeting and almost accidental contacts between the black and white branches of the Anglican charismatic renewal, but here they were all obviously together.

Bishop Graham Cray from the Church of England, speaking on Fresh Expressions of Church

Back then there were also no all-Anglican charismatic conferences. Yes, there were IViyo conferences, but they were nearly all black, and only involved a few dioceses. White Anglicans mostly went to ecumenical conferences, and many were sucked off into Neopentecostal denominations, some of which started off as ecumenical organisations, and then formed their own denominations. This one was an all-Anglican (apart from the odd visitor, like me) and included people from Namibia to northern Mocambique.

But the biggest difference was perhaps that expressed by Bishop Graham Cray, from England, speaking on Transformed by the Holy Spirit, when he said that Christians are being called out of “consumer Christianity which exists to bless me, to a missional Christianity which is called to bless others”.

And that difference was seen in this conference too. There was almost traditional charismatic worship and ministry, but a lot of the workshops dealt with the nitty-gritty of ministry in places like the slums of Nairobi, excoriating the handout culture of foreign NGOs, which paid people to attend workshops, and rather encouraging the local churches in the slums to develop their own community development ministries.

In almost every way I thought it looked better and more hopeful than the charismatic renewal of the 1970s, with only one exception — the English songs didn’t seem nearly as good as the ones we sang back then. Perhaps it was just that I didn’t know any of them, but the ones in Zulu and Sotho seemed as good, even though I didn’t know any of them either.

I’ll be going back tomorrow, God willing, and will perhaps have a fuller picture then but it seems that something is still happening among the Anglicans. It mainly seems to be the Methodists that are so secretive.

Bishop Martin Breytenbach and the music group

October 2, 2012

Traditional Christianity

What medieval English and Welsh parish churches used to look like.

St Teilo’s Church in Wales

If you visit churches in Britain today, especially those built before 1500, you may not realise that their interior appearance owes much to the vandalism of the Puritan iconoclasts.

St Teilo’s Church in Wales is actually a museum reconstruction of what such churches probably looked like.

Hat-tip to A conservative blog for peace.

September 26, 2012

What shall I blog about?

Last week, when I moved my Notes from Underground blog from Blogger to WordPress, I wasn’t sure how to divide material between this one and that. I had previously decided according to which blogging software was most suitable for what I wanted to write, but now it is the same, so I thought I should divide it according to subject matter, and asked readers to help me by voting in polls here and here. Thanks very much to those who have done so, as it has helped me to decide.

Khanya blog readers wanted:

History — 25%

Culture — 21%

Missiology — 17%

Theology/Literature — 12,5%

Notes from Underground readers wanted:

Politics — 29%

History — 23%

Culture — 17%

Personal/Literature — 12%

Well that’s a fairly clear division, except perhaps for History and Literature.

So in future I’ll use Khanya for more academic subjects, especially in Missiology and Theology and History (but I’ll continue the Tales from Dystopia series, which are more personal). Literature and book reviews of non-fiction will mainly be in Khanya too.

I’ll use Notes from Underground for comments on current political issues, reviews of popular fiction (such as whodunits) and personal reminiscences (like the Mirbane article). There will still be some overlap, of course, but Khanya will tend to be more academic and serious, Notes from Underground more light-hearted and ephemeral.

I also used to use Notes from Underground for quick ‘n dirty links to interesting blog posts, as Blogger was a more suitable platform for that. But Tumblr is even better suited to that, and so I’ll rather use my Tumblr mini-blog, Marginalia, for quick links. In reviewing Notes from Underground to see which posts to keep and which to discard, I found many such links were broken, especially when bloggers had rather inconsiderately decided to delete their blogs. So here’s a plea to all bloggers: if you are going to stop blogging, just stop, and don’t delete your blog. Even if you don’t add to it, links to your older posts will still work, and thus won’t contribute to Internet entropy.

There are also still a lot of fairly serious articles on Notes from Underground, including some on the subjects that I’ll now mainly be writing about on Khanya. Here are some, mainly missiological, that I think might still be worth reading:

Evidence that demands a verdict? – Missiology, inculturation and modernity.

Tolerance – Has “tolerance” become a weasel word?

The Liberal Party of South Africa – an article that has been arbitrarily removed from two other web sites

The state should get out of the marriage business – marriage and other social and domestic partnerships

Spiritual Warfare — a group of us had a synchroblog on spiritual warfare

Rulers and authorities, territorial spirits, and spiritual warfare — church and state and other related issues

More thoughts on spiritual warfare — response to some of the posts in the synchroblog on spiritual warfare

St Constantine: scapegoat of the West — some Western missiologists and others really have it in for St Constantine, and blame him for just about every conceivable problem in the church

Consciousness of absurdity and the absurdity of consciousness — is there a ghost in the machine?

Psychedelic Christian Worship — a controversial church service in Durban, over 40 years ago

You can also find this list, and more, on the “About” page of Notes from Underground.

September 24, 2012

Heritage Day

Today, 24 September, is Heritage Day, and we are told that the theme for Heritage Day this year is “Celebrating the Heroes and Heroines of the Liberation Struggle in South Africa”

Well, I’d like to celebrate one of my own heroes of the liberation struggle, and probably very few people know anything about him, and I doubt if any streets have been renamed after him.

He was a peasant farmer by the name of Enock Mnguni.

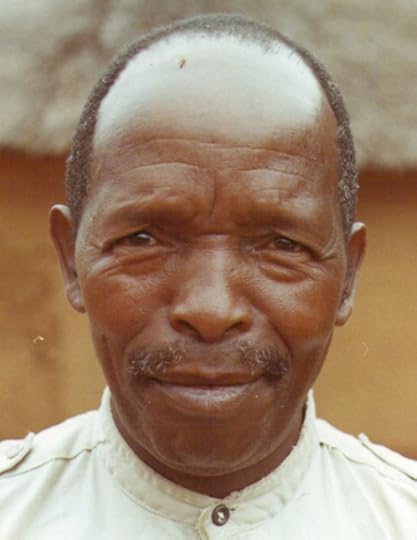

Enock Mnguni, hero of the liberation struggle

I don’t know a great deal about his life. His English was rudimentary, and my Zulu was even more rudimentary. So I ask anyone who knew and remembers him to add some more details in the comments space below.

I know that in 1960s he worked at Oxenham’s Bakery in Pietermaritzburg, where he led a strike, and that he was also detained in the 1960 State of Emergency. When I first met him he was a peasant farmer at Stepmore, on the Upper Mkhomazi River near Himeville. He and his wife belonged to an African independent Church, called the Ukukhanya Presbedia. It was founded by one Timothy Cekwane, who was (according to Bengt Sundkler) inspired by Halley’s Comet in 1910 to break away from the Presbyterian Church of Africa and form his own denomination, The women of the church wear distinctive red and green uniforms, and it is one of the few African independent churches that has red in its uniform. At Mnguni’s home at Stepmore there was special furniture in the rafters of the house, kept for the sole use of the church minister when he visited, The church was also, so its leaders, and everyone else said, strictly non-political. But Mnguni himself was not non-political. He was the chairman of the Stepmore branch of the Liberal Party, and was active in forming other branches in the Drakensberg foothills.

The police, and especially the Security Police, did their best to disrupt the meetings of the Liberal Party there and elsewhere. On one occasion there was to be a meeting of several branches all gathered together at Mnguni’s place. The day before the meeting the police arrested Mnguni on a trumped up charge of failing to pay his poll tax. Some speakers from Pietermaritzburg who had arrived by car heard about this, drove to Himeville police station and did a quick whipround to pay Mnguni’s bail, and the meeting went ahead. But it wasn’t always so easy.

But Mnguni persisted, and eventually he was banned. He was Enemy of the State number 1589.

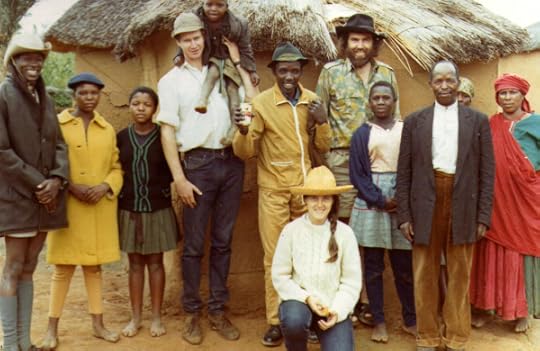

KwaMnguni, 1972. Mrs Mnguni, on the right in the picture, is wearing the Ukukhanya Presbedia church uniform.

Some years after the Liberal Party had been forced to disband, Enock Mnguni went to the Valley Trust to learn some improved agricultural methods to try to increase the yield of crops on his land. He went and learnt from a Mr Mazibuko, and came back and tried the methods he had learnt. He noted that the first fields where he tried the new methods gave increased yields of mealies, so he applied them generally..

A group of us went to visit him, and spent a couple of days there, helping him to build a chicken run. At night, sitting around the cooking fire chatting, he remarked how strange it was that some people knew just one thing. He cited Mr Mazibuko as a case in point. Mr Mazibuko knew a great deal about farming. He had to give him that. Mnguni was very impressed with his agricultural knowledge and expertise.

But Mr Mazibuko, said Mnguni, knew nothing at all about politics. In that area he was incredibly ignorant and naive. In his office at the Valley Trust Mr Mazibuko had a picture of Dr Verwoerd, and when Mnguni talked to him about politics, he appeared to know nothing.

There are many heroes of the liberation struggle, some well known, some unknown. But Enock Mnguni is one of the greatest heroes to me. He stood up for what was right, and persisted with patience and perseverance evenwhen the State did its best to stop him.

September 21, 2012

Notes from underground

I recently moved my blog Notes from underground from Blogger to WordPress.

I started this blog on WordPress at a time when Google were messing with the Blogger interface, and many dissatisfied Blogger users were moving their blogs. But at that time I still kept the old blog, and posted to both.

When the Blogger platform stabilised (after about 6 months were lots of things didn’t work) I posted stuff to both blogs, depending on which platform was most convenient. Each had its advantages and disadvantages.

WordPress was much better for graphics. It gave much more control over where and how pictures were posted, and allowed one to insert captions. Blogger did not allow captions, and now the graphics functionality has been still further reduced by not allowing you to chose the size or position of the picture.

WordPress is also much better in using simple HTML. If you chose Bold from the menu, WordPress simply surrounded the bold text with the normal HTML commands and , whereas Blogger would fill it up with a lot of incomprehensible stuff like and and whatnot. So WordPress was simplet to use.

But Blogger did have advantages.

One was that it allowed Javascript. That made it useful for social blogrolling widgets like the now defunct MyBlogLog and the almost defunct BlogCatalog. It made possible a live blogroll in the sidebar, which showed the latest posts in the blogs in one’s blogroll. The WordPress static blogroll isn’t nearly as good. You can go to a blog and see it hasn’t been updated for a year, and eventually you ignore it, so that by the time you do go there, the new post that you haven’t seen is several weeks old. With the Blogger blogroll, a new post on one of the linked blogs puts it at the top of the list.

Blogger was also good for quick ‘n dirty blog posts — it’s “Blog This” gadget let you copy text from a news item or another web site and comment on it — and that, after all, was the original purpose of blogs – a web log, a record of web sites you had visited and what you found interesting about them.

I found, however, that this blog, Khanya soon attracted more readers than Notes from underground. The difference was quite significant — something like 2-3 times as many readers. I don’t know whether this was because readers preferred the WordPress platform, or that something about WordPress made it easier to find.

The recent changes to the Blogger interface seemed to remove many of the things it had that were easier to use than WordPress. The editor has a much smaller typeface, which makes it harder for old fogeys like me to read. Menu items are hidden under cryptic symbols, so by the time you have found what you were looking for, you have forgotten what you were going to say anyway. It got in the way of writing. So I moved thre blog to WordPress.

I still left the old one there, though. I just won’t be adding to it.

I find it very annoying when people not only abandon a blog, but delete it. It breaks all kinds of links to articles they wrote. And there are lots of links to articles in Notes from underground from other blogs and web sites, not least from this one. So I’ll leave it there, I just won’t add to it.

So it’s moved to a new address, and all the old posts and comments have moved with it (I hope).

The problem is, how do I decide where to post stuff now?

With the blogging platform exactly the same, there are no longer any advantages to make me choose one in preference to the other.

One possibility would be to distinguish between them by posting different kinds of material on each.

In some ways I’ve tended to do that already. The old Blogger interface made it easier for the quick ‘n dirty blog post, so I would tend to post more ephemeral stuff on Notes from underground, more serious stuff on Khanya. If it was a book review, I tended to put trashy novel reviews on Notes from underground and reviews of more serious books on Khanya — not just because of the user interface, but because Khanya had more readers. But, especially in the early days, there was a lot of serious stuff on Notes from underground too.

So I’m asking for help from readers (and if you’ve managed to read this far, you must be a serious reader) to let me know what kind of material you like to read on blogs in general, and this blog in particular, and what you would most like to see in future articles on this blog. Please vote in the poll, and elaborate in comments if necessary. And if you read the Notes from undertground blog, please go and vote in the poll over there too. You can choose up to four.

Take Our Poll

September 19, 2012

Conflict, violence, and non-violence

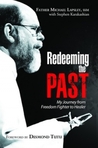

One of the issues that Father Michael Lapsley’s new book, launched recently, raises is the question of violence, non-violence and reconciliation. Just a few days after I read the book we had a discussion about conflict resolution in our parish, and so I’ve been thinking about it quite a lot.

Redeeming the Past: My Journey from Freedom Fighter to Healer by Michael Lapsley

Redeeming the Past: My Journey from Freedom Fighter to Healer by Michael Lapsley

In his book Father Michael describes how he was a pacifist, and then after coming to South Africa from his native New Zealand, he experienced a crisis of faith, and eventually he abandoned his pacifism, and joined the ANC and supported its armed struggle, and only returned to a ministry of reconciliation after South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994.

In my initial review of the book I mentioned that there was too much in it to write about in a single review, and that one of the effects, and indeed one of the objects of the book is to start a conversation, or a whole lot of conversations, so this is one of them.

In the book Fr Michael describes his conversion to the idea of the “just war”, or perhaps it could be called the “just revolution”.

Like Fr Michael, I became a pacifist in my late teens. In 1959 there was a debate between between two Anglican parish youth groups, of the parishes of Orange Grove and Yeoville in Johannesburg, on the topic “Euthanasia should be officially condoned”. Most thought that it should not, and after the debate the parish priest, Fr Cyril Britton, said that he was a pacifist and a communist. A couple of years later Brother Roger, of the Community of the Resurrection, spoke at a rally of the Anglican Young People’s Association (AYPA) at Krugersdorp, where there were representatives of about 20 different parishes. He gave a question for group discussion — would a Christian be justified in fighting in a war? Eight out of nine people in the group I was in said yes, they would, if the war was to the glory of God. I argued that no war was to the glory of God. It was the arguments they used in favour of militarism that pushed me in the direction of pacifism. I began reading about the Quakers, and when I saw an advertisement for the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship in an overseas magazine, I immediately wrote to them to ask for more information. Among the information they sent me was the interesting fact that three Anglican bishops in Southern Africa were card-carrying pacifists — Bishop Alpheus Zulu of Transkei, Bishop John Maund of Lesotho, and I think the third was the Bishop of Kimberley. I joined right away.

Michael Lapsley, having gone to Australia, joined an Anglican monastic order, the Society of the Sacred Mission (SSM), and was ordained, and was then sent by his order to South Africa, where he discovered that he had ceased to be a human being and had become a white man. He discovered that his life, like that of all South Africans, was determined by race, or skin colour, or, more specifically, “population group”, which determined where you could live, whom you could marry, where you could go and what you could do when you got there. It determined what school or university you could go to, what subjects you could study, and what jobs you could do. It determined what buses or trains you could travel on, and what door you could enter the station through, and more, much more.

The SSM in Durban were Anglican chaplains to students at three university campuses in Durban – one black, one white, and one Indian. One of the issues faced by white students was military conscription. Actually for most it wasn’t an issue at all. They just accepted it. All white males had to register for miliary service in the year they turned 17, and were liable to conscription for miliary service in the year they turned 18. In most cases they had to register when they were still at school. I did. But at the time that I did there was a ballot, and whether one actually did military service was the luck of the draw.

A friend of mine from the same church, the same age as me, was drawn. After leaving school in December, he went off to a military training camp for three months, after which he went to university with me. After that he had to go to another camp at the beginning of every year. As a full-time student he could have applied for deferment, and done his military training after graduation, but he decided it was better to “get it over with”, and so spent the next few years going to military camps every January. I didn’t. It was the luck of the draw.

And perhaps it was just as well, because at the age of 17 I hadn’t made up my mind about the Christian ethics of war. I might have gone, and succumbed to the militarist and racist indoctrination that army trainees were subjected to. Many did succumb to it, and the National Party government, realising the political advantages of this, abolished the ballot a few years later, and made military conscription for white males universal, and reduced the voting age from 21 to 18.

But some resisted. One army conscript got his introduction from the sergeant who told the rookies, “Now we are going to teach you how to shoot kaffirs.” He walked out. So I was told by the same Brother Roger who had got the youth at Krugersdorp to discuss the provocative question. He never told me what happened to the trainee, and when I met him a few years later (his name was Dave Tucker) I forgot to ask.

The National Party government did not like Fr Michael Lapsley’s influence on students, which threatened to undo all the work done by their indoctrination, and so, after three years in South Africa, he was deported. He went to Lesotho. And, as he puts it:

Over the course of the three years that I lived there, my conviction about what it meant to be a Christian gradually eroded and finally collapsed in the face of the shooting of innocent children. I began to realise that my understanding of the gospel did not take account of the sheer magnitude of evil. It was perhaps adequate to another time and place, but it had little to offer unarmed protestors facing a lethal barrage of bullets. As a result, I began more and more to question my pacifism. My faith had been my comfort in the midst of oppression. Now, I could no longer even depend on it, and, spiritually speaking, I felt the ground shifting under me…

I had gone to South Africa as a committed pacifist. I had refused high school military training in the face of peer pressure and the unspoken disapproval of my parents, and I thought my father was wrong to fight against Nazism in World War II. I regarded violence as the very antithesis of the gospel message of peace and love… So for me, pacifism was both a tactic and a principle of the gospel and I believed that non-violent methods were the only morally defensible way to deal with conflict…

As I preached non-violence to students, black and white, however, I began to notice that the apartheid state was extremely happy for me to tell black people that they shouldn’t use weapons to achieve their rights. Suggesting to white students that they shouldn’t go to the army, however, was another matter altogether. The conversation itself was illegal. So the state believed in non-violence for the oppressed but never hesitated to use violence to assert its own interests.

Back then, in the 1970s, most South African church leaders were weak and vacillating, and tied themselves up in moral and ethical knots.

In 1968 many of them supported the Message to the People of South Africa, a document that examined the ideology of apartheid theologically, and ripped it to shreds. Apartheid, according to the Message was worse than heresy; it was a pseudogospel. In 1970, however, when the World Council of Churches’ Programme to Combat Racism gave grants to liberation movements, the church leaders denounced that as well, on the grounds that some of the liberation movements concerned espoused and practised violence. They continued, however, to provide chaplains to the South African Defence Force (SADF), and did not urge the members of their churches to resist service in the SADF on the grounds that it, and the government that it served, espoused and practised violence.

What many South African church leaders then said, in effect, was that violence for a good cause can never be justified, but violence for an evil cause can be justified. That such a position was morally and logically untenable did not seem to occur to them. In that, they adopted the position of the state: that violence used by the oppressed to overthrow their oppressors was illegitimate, while violence by the oppressor against the oppressed was legitimate.

After arriving in Lesotho and joining the ANC Michael Lapsley writes:

One of my first acts was to write an article entitled ‘Christianity and the just war’ in Sechaba, the ANC journal published in Dar-es-Salaam. In it I articulated some of the arguments from a faith perspective for supporting the armed struggle. While there is no doubt that non-violence is the morally superior way and is the preferred option wherever possible, there is nevertheless a long history within the Christian tradition of just war theory. St Thomas Aqunas developed the theory, not as an attempt to bless war, but as an attempt to say, ‘If there is to be war, there still needs to be a form of morality.’ Just war theory providees a sort of checklist that must be exhausted in order to conclude that a war is permissible. In the Sechaba article, i took apart the theory point by point and demonstrated how in my view the liberation struggle met its criteria. I emphasised that just war theory was not created to make it easy to justify killing, but to the contrary it was to provide as many moral safeguards as possible and to make sure that war is used only as a last resort.

At that point, I suppose, I differ from Michael Lapsley, in theory, if not in practice.

To explain why, I need to backtrack to the 1960s, when I became a convinced pacifist in 1961. I was on the mailing list of the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship (APF), and received their literature. I made contact with other groups with pacifist tendencies, such as the Catholic Worker in the USA. In South Africa I made contact with a saintly pacifist priest, Arthur Blaxall, who was the bosser-up of the local branch of the interdenominational Fellowship of Reconciliation.

In 1966 I went to the UK to study, and met members of the APF. I also became involved with the Christian Committee of 100, and took part in a small and embarrassingly ineffectual demo against the Vietnam War outside the American Embassy in London. I suggested that we sing a hymn, two verses of which read:

Thy kingdom come, O God

Thy rule O Christ begin

Break with thine iron rod

the tyranny of sin.

When comes the promised time

that war shall be no more

and lust, oppression, crime

shall flee thy face before.

I suggested it for the line about “war shall be no more”, which appealed to my pacifist sentiments, and, coming from South Africa, the reference to oppression put it in the category of oppressed and downtrodden people’s hymns, rather than boss-nation hymns.

But one of the other members objected to the first verse. “Break with Thine iron rod” suggested violence, and would therefore offend our principle of non-violence. It didn’t bother me, because I saw it as metaphorical — sin may be couching at the door, but it isn’t a human person with a right to life.

But it made me aware that many people saw pacifism in a kind of legalistic way, as a principle that one may not bend, or even an ideology. It was in fact part and parcel of the legalism of much Western theology, which is so concerned with “justification”. And that is just the other side of the coin from the notion of the “just war” and “justifiable homicide”.

I’ve already written about this at some length in another blog post on Pacifism, Orthodoxy and the “just war”, so I won’t say any more about it here.

There is one more thing I’d like to say here, though, and it is one that came up in our discussion on conflict resolution in our church last weekend — what is the place of compromise?

In some circumstances, perhaps, there is a place for compromise. At the moment there are miners on strike at Rustenburg over wage demands. The union leaders speak rather deprecatingly about wildcat strikes that shortcircuit the process of collective bargaining. But when the workers and the management get together (if they do, because they have been refusing to speak to each other) then the workers may demand a certain pay increase and the management maqy offer another one, and eventually they may compromise on something in between. Neither side gets exactly what they want, but they get something that they can live with. That is compromise, and it is an example of where compromise can be good.

But compromise is not always good.

To go back to South Africa of the 1970s, the World Council of Churches’ decision to give financial aid to liberation movements was a wake-up call to some South African Christians. They deprecated the WCC action, but realised that they had been coasting along and doing nothing.

The Anglican response was to set up a programme of “Human Relations and Reconciliation”, of which it was said:

We believe that this programme is a response to a crisis in faith. By this we mean that we recognise that the lives of individual Christians and the structures of the Church are so conformed to our apartheid society that we are unable to bear and effective witness to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. A radical reformation is urgently needed. This involves the recognition that if we take seriously the Programme of Human Relations and Reconciliation it will almost certainly mean, in the words of the Report of the Anglican Congress in Toronto in 1963, “the death of much that is familiar about our Churches now. It will mean radical change in our priorities. It means a willingness to forgo many desirable things in every church…”

Other denominations set up similar programmes, most of which were given names like “Justice and Reconciliation”.

This in itself is an example of compromise. Some wanted to emphasise Justice, others wanted to emphasise Reconciliation, and both sides gave good Christian reasons for doing so. So, as a compromise, such programmes often included both words.

But after such programmes were established, there were complaints. Each side complained that too much emphasis was given to the other. But the problem (which Michael Lapsley also mentioned in his book) was that people often did not discuss their hidden presuppositions.

A compromise in a wage dispute can bring about a reconciliation, of sorts, between workers and management. A compromise between people who have been fighting can bring about a reconciliation between them. But very often what the advocates of “reconciliation” wanted was a reconciliation between good and evil. But there can be no reconciliation without repentance. If a man beats his wife, then if they are to be reconciled, he must repent of beating his wife, confess that sin and forsake it.

If a government is oppressing its people, then it must repent of that and stop doing it. But many of the advocates of “reconciliation” in the 1970s and 1980s were saying, in effect, that the oppressed should be reconciled to their oppressors, who would go right on oppressing them.

There were two different political principles at stake: on the one hand a race oligarchy, and on the other non-racial democracy. They are by their very nature irreconcilable. Perhaps our present problems spring from the fact that we have compromised and tried to combine them, so what we have now is a non-racial oligarchy, or what may perhaps better be described as a plutocracy.

It is good for people at enmity to be reconciled to one another, and that is an important part of conflict resolution. But the conflict between good and evil cannot be resolved by compromise. It can only be resolved by repentance — turning away from evil and embracing what is good.

September 18, 2012

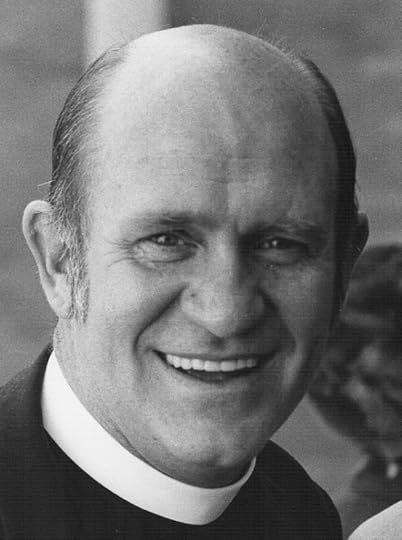

In Memoriam: Bishop Duncan Buchanan

Since I heard of his death (through a friend’s post on Facebook) about 10 days ago, I’ve been hoping to see an obituary of Duncan Buchanan, the late Anglican Bishop of Johannesburg, but there’s nothing to be found by Google, So i thought I would write something about him.

Not that I knew him as a bishop. After he became bishop of Johannesburg I think I only met him to talk to three times — first when our new Orthodox Church of St Nicholas of Japan was meeting in the Anglican church hall in Fairmount, Johannesburg, and the Dean of Johannesburg didn’t like it, so we appealed to Duncan, and he arranged for us to meet in the chapel of St Martin’s in the Veld at Dunkeld — I’m not sure what the dean thought about that.

The second time I met him was when he was on a team of people interviewing me for a job, which I didn’t get. And the third time was when I went to interview him about his memories of the charismatic renewal movement, about which I’m writing a book.

But I had quite a lot more contact with him before he became a bishop, so my memories of him are mainly of when he was younger.

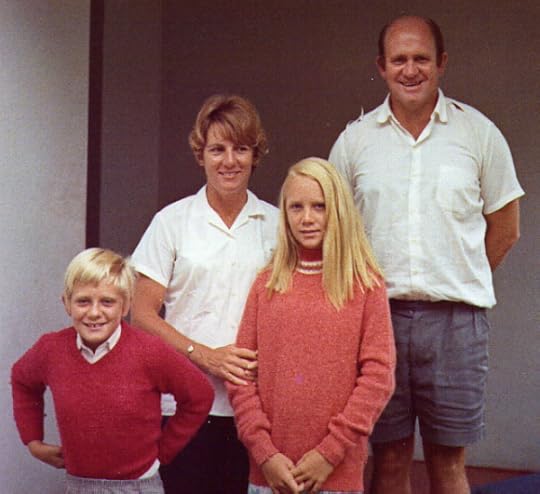

Di and Duncan, Jean and Anne Buchanan, Grahamstown, 1972

I knew Duncan by repute even before I met him.

In the early 1960s a group of us from the AYPA (Anglican Young People’s Association) at St Augustine’s Church in Orange Grove (the same parish that had the hall in Fairmount that we used for Orthodox services 25 years later) we were tidying the vestry and parish office and came across a pile of old parish magazines, and we got distracted by reading them, and there was an article about Duncan Buchanan, wishing him well as he went off to college or university. It was dated 1952, and one of the bits in the article that stuck in my mind was his habit of saying of other people’s weak jokes that “It was corny but clean.”

Duncan Buchanan, Pietermaritzburg, 1981

I first met Duncan in the flesh on 4 March 1963, when I went to a meeting of the Fellowship of Vocation, which was a group for wannabe clergy of the Anglican Diocese of Natal, which met once a month in Pietermaritzburg. Duncan was the warden of the fellowship, and came up from Amanzimtoti south of Durban for the meetings, a drive of about 70 miles each way. We said Evensong in one of the chapels of the Cathedral and then had a meeting in the hall. We talked about church history, and also about teaching people to pray rather than go to church. Duncan said it was far better to get on a man’s wavelength than to preach to him, and it is better to talk to men than to women. I thought that that was a bit sexist, but I was new there, so said nothing. It turned out to be one of this themes, perhaps as a result of experience in his parish.

I had just started as a student at the University of Natal, and asked Duncan if I could join the Fellowship of Vocation, which was somewhat problematic, because he needed a recommendation from the parish priest, and I had been in Pietermaritzburg for only a couple of weeks, and had only just met the parish clergy.

Duncan was also involved in Faith in Action, a kind of ginger group in the Anglican Church of those days, which was concerned with things like liturgical reform, and more active laity, and the church being more outspoken about the political situation and such things. Some of us went to a national conference of Faith in Action in Grahamstown, where Duncan was one of the speakers. The group also produced a magazine of the same name, which Duncan edited for a while.

For three years, then, from 1963 to 1965, I saw Duncan fairly regularly at the Fellowship of Vocation meetings. He did not speak at all of them, but got other people to speak on various topics. Once a year the Durban and Pietermaritzburg branches met together at St Agnes’s Church in Kloof, and at one of them a churchwarden spoke about what the laity expected of the clergy, and at another, Alan Paton, a parishioner, spoke on the same topic.

The University of Natal was in the parish of St Alphege’s in Pietermaritzburg, and in many ways it practised what Faith in Action preached. It had a core of active members who took their Christian faith seriously, and tried to put it into action in their daily lives, and in their work. The Rector, Mervyn Sweet, encouraged this, as did the assistant priests, Rich Kraft (who later became Bishop of Pretoria) and Graham Povall.

At the end of 1964 Mervyn Sweet announced that he would be leaving St Alphege’s and going to the UK. A friend of mine, John Aitchison, who was also a member of the Fellowship of Vocation, and I discussed who his successor should be. And the only priest we could think of from within the diocese who might be a suitable successor was Duncan Buchanan. But it was not to be. The man who succeeded Mervyn Sweet turned out to be a dictator, who disliked the laity having too much say, and worked very hard to clericalise the parish. There were some heated discussions at parish council meetings when the new rector introduced private baptisms, and the lay members of the council gave the rector lessons on the theology of baptism, which he did not appreciate.

At the end of 1965 Duncan went to be sub-warden of St Paul’s Theological College in Grahamstown, and I went overseas to study at St Chad’s College in Durham. At the end of my studies at St Chad’s, rather than wait for a two-week term in September, I asked the Bishop of Natal if I could rather spend time in an African college to re-Africanise myself after more than two years in Europe, and so he arranged for me to spend a term at St Paul’s where Duncan was still the sub-warden, and so for the next couple of months I saw him almost every day.

I got to know him better then, though we didn’t always see eye-to-eye theologically. One discussion that I recorded in my diary may be worth sharing — Saturday 26 October 1968 (“Fronnie” refers to the warden, John Suggit):

We had Mass before supper, using the Liturgy for Africa, then after supper was Warden’s Hour, a sort of discussion of how the college is being run, and things which could be improved and so on. Some people complained about noise, and said that it got so bad that they couldn’t work. Others said they should then go and ask the people who were making the noise to be quiet, but they said they didn’t feel they could do that, so they just sat in their rooms “seething inside”, said Fronnie, and everyone laughed.

Then followed a general discussion on rules and discipline. Some people complained that observance of rules had become rather lax lately. Duncan said he thought this slight relaxation had led to a greater sense of fellowship and koinonia in the college. I said that the spirit of the rule was observed even if the letter wasn’t, and that this was a healthy state of affairs because it indicates that the rule has a real meaning and function in the college, while at the same time people are not becoming slaves to it. I also had an argument with Duncan and a couple of others who started rationalising about rules, and saying they taught the virtue of obedience. I disagree violently with this, and can see no virtue whatever in obedience per se — and it was this argument that Adolf Eichmann pleaded in his defence — that he was only obeying orders, as if that in itself is a virtue. I can see that it is good at times to obey. It is good to obey the right person in the right circumstances, but obedience is not always right.

We somehow got on to the oath of obedience to bishops, and here I argued with Gerald Francis, who didn’t fancy this very much, and I said that the bishop is given the power of the Holy Spirit, and his decisions are the decisions of the Spirit. Duncan at this point thought I was being sarcastic, and Fronnie said he was quite surprised that I maintained the divine right of bishops. But I do. The bishop derives his authority directly from Christ, and the Church is the Body of Christ, so the bishop derives his authority directly from the church.

Duncan preached a couple of rousing sermons in the College chapel on hope.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s I saw Duncan at least once a year at the annual meetings of the Anglican Church’s Department of Theological Education. By then he had become Warden of St Paul’s, while I was involved in in-service training in the Anglican diocese of Zululand. The meetings tended to get bogged down in repetitive arguments about “what kind of ministry are we training people for?” which never seemed to reach any conclusion. People came with all kinds of ideas on paper qualifications, but Duncan once said that he didn’t care what kind of paper qualifications people had when they went to St Paul’s, and that a Matric meant nothing to him. The only thing necessary was that they should be able to read, write and understand English.

September 16, 2012

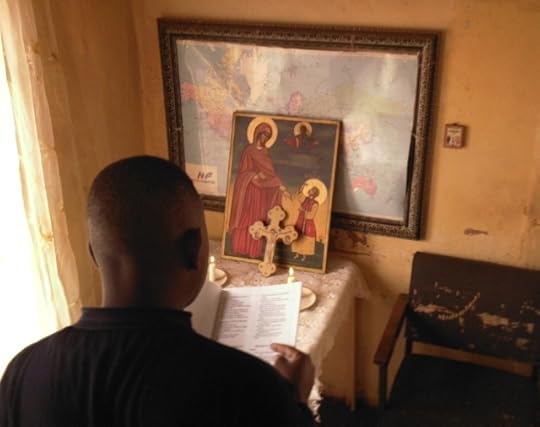

Atteridgeville Sunday

We went to Atteridgeville for the Hours and Readers Service. Angelos Mokau had gone to the children’s home at the beginning of the month, and we wanted to see how he was getting on. Angelos is a Reader, who spent three years at the catechetical school in Yeoville.

It rained last night, so everything was looking clean and scrubbed as we drove there, and we stopped to take pictures of some landmarks that we passed.

Blacksmith of Judea Apostolic Church

One of the landmarks is the Blacksmith of Judea Apostolic Church, though it seemed to be well and truly locked up on this Sunday morning. It’s another one to add to my database of African Independent Churches. It would be nice if we could have a church building like that where we could meet, but we meet in a small room in the children’s home.

The Blacksmith of Judea Apostolic Church

Some African Independent Churches have quite fanciful names, and sometimes there is quite an interesting story behind the name. It would be interewsting to know about the blacksmith of Judea.

A little further on we come to Brazzaville. Brazzaville is described as an “informal settlement”. We followed the water lorry delivering water to strategically placed tanks, and passed several people pushing wheelbarrows with plastic containers to collect their supply of water from the tanks, or going home with them loaded.

Brazzaville, west of Pretoria

There are poles set up for electricity, but no wires, so electricity and running water are unknown in Brazzaville. Perhaps one reason for that is that when people began building their houses here, it was actually an old army firing range, and children sometimes discover unexploded shells and grenades, and some have been hurt. So the City of Tshwane has stopped plans for services like water and electricity, and is planning to resettle the people in a safer place.

We reach the children’s home, right on the edge of the inhabited area, with densely packed wood and iron houses on one side, and bare veld on the other.

Angelos leads the Hours and Readers Service (Obednitsa, Typica).

Angelos reading the Obednitsa

At the end we chat to some of the people, especially the three leaders, Artemius, Demetrius and Sergius. They were all baptised together about 3 years ago.

Artemius, Demetrius and Sergius

They tell us about progress since we were last here a fortnight ago. They have mended the broken windows, and a start has been made on building the fowl run for the cooperative poultry project they are planning.

As we are leaving, a police van drives up. They have come to check on a woman they brought here the other night. She was abused by her “boyfriend”, who had stabbed her several times. The police took her to stay with friends, but he found her there, so they brought her here. Perhaps God wants a new ministry here, to abused women rather than abandoned children. Angelos asks the police to check up occasionally, to make sure that she is safe.

We drive him to town to get a taxi to Soshanguve, where his home is. On the way he says he wants to do a course in counselling. We ask what sort of counselling. People with HIV/Aids, and things like that, he says. We hope we can find something useful.

September 13, 2012

Most popular posts

“I’m interested to know– which of your posts has gotten the most traffic, and do you have any idea why?” Matushka Donna Farley asked on the Orthobloggers page on Facebook.

My immediate response was to say that mine was one I wrote just last week, on boycotting Woolworths. It appeared that Woolworths was threatening to fire staff who did not sign new contracts that would require them to work at any hour of the day or night 24/7/365. We have had mission congregations where most of the people are unemployed. We pray for them to find jobs, and then that’s the last we see of them because they are required to work on Sundays. But the cause I advocated was not popular — it was just that a few days later some white racists called for a boycott of Woolworths for a different reason, so the popularity of my post was rather coincidental. The previous most popular post was in 2008, on Will the real satanists please stand up.

But then I realised I was counting wrong — both those posts were the ones that caused most visitors to come to my blog on a single day. But the ones that actually get the most visitors (I was going to say the most readers, but then realised that people might come to the page, see it wasn’t what they were looking for, and go away after reading a couple of lines) are the following, which have all had over 1000 visitors, though I wonder how many people actually read them.

Top Posts for all days ending 2012-09-14 (Summarized)

All Time

Title

Views

Home page / Archives

51,250

What is Google installer, and why is it trying to access the Internet?

17,874

The appearance of Jesus Christ: redux

15,622

Stuff to do on Sunday if you’re bored

9,143

About me

7,838

Tales from Dystopia

6,099

Fighting crime — proactive or reactive?

4,506

More stuff to do on Sunday if you’re bored

2,814

The Church as the Liberated Zone

2,786

WordPress promoting porn?

2,772

Makwerekwere

2,484

Witchcraft, African and European

2,459

The legacy of apartheid and the culture of violence

2,340

The theology of Christian marriage

2,257

The youth of today, and yesterday

2,255

The appearance of Jesus Christ

2,096

Ethiopian Orthodox Church

2,067

Christianity and shamanism

1,983

Love is the measure: Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker

1,818

Bad theology: Vassula Ryden and Benny Hinn

1,790

Charismatic Renewal

1,658

Human Rights and Christian faith

1,615

Christian understandings of paganism and witchcraft

1,464

What is African? Race and identity

1,441

Salvation and atonement

1,441

How much is a (US) gallon of petrol in the rest of the world?

1,437

Khanya Blog

1,435

Angels and demons and egregores (book review)

1,423

Ostrov (The Island) — film

1,310

Who stole Halloween?

1,300

Gleanings from the Inklings

1,249

The end of an era — Anglo-Catholicism rides off into the sunset

1,224

Inculturation, indigenisation, syncretism and cultural appropriation

1,161

Mikhail Gorbachev as a Christian

1,150

Holy Glorious Great Martyr, Victorybearer and Wonderworker George (303)

1,123

Tolstoy Remains Snubbed in Russia – NYTimes.com

1,068

Holy Places–Thin Places

1,041

St Theodora the Iconodule

1,039

Adult content

1,024

The Hunger Games (book review)

1,008