Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 69

June 27, 2012

The Slap (book review)

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Last week I was at the Joint Conference of academic societies in the field of Religion and Theology in Pietermaritzburg, and the theme of the Southern African Missiological Society’s track was Migration, mission and theological education. I bought this book to read in the evenings before going to sleep, and found that in several different ways it reflected the theme of the conference. It was largely concerned with migrants, and it made me think of migrants and migration.

The book also changes in character and direction, as the viewpoint character changes, so that one is never sure where it will end up until one actually reaches the end.

It is set in Melbourne, Australia, and it begins being seen through the eyes of the host at a suburban barbecue. One of the guests slaps an obstreperous child, whose parents accuse the man of child abuse and call the police. The people at the barbecue (braai) are in some ways a cosmopolitan bunch, representing various diasporas of immigrants to Australia. It seems horribly middle-class and suburban, and in some ways familiar, like a white-middle-class South African suburban braai. But it has overtones of My big fat Greek barbie. Many of the families are Greek immigrants, or children and grandchildren of Greek immigrants. And that is familiar too. The Greek diaspora in Australia is not all that different from the Greek diaspora in South Africa, or in North America, for that matter. If you change the accents, the film My big fat Greek wedding could easily have been set in South Africa, right down to the hair styles.

Most of the characters are “wogs”, which in Australia seems to refer mainly to people of Mediterranean ancestry. The Australian vocabulary takes some getting used to. There are also “bogans”, which the wogs, or these particular wogs, despise — being lower-middle-class Anglo-Australians with a penchant for kitsch. The South African equivalents were perhaps those referred to in Jeremy Taylor’s song The balld of the southern suburbs.

So there are all these Diaspora people, and that links up with our conference theme of migrants and migrations.

The story is told from the viewpoint of different characters, and their views and backgrounds are very different. Some are suburban housewives, some are their husbands, some are teenagers, one is an old man — My big fat Greek funeral. But the action moves forward, so the characters do not see the same events, but rather each stage of the story is seen through the eyes of a different character.

There are also rather disconcerthing gaps. The book goes into great detail about the sexual encounters and fantasies of the characters, almost a throwback to 1980 novels with their obligatory shag (which often seemed to be there only because the publishers demanded it), yet in these suburban families we are not told the ages of most of the children. The boy who was slapped was 3 going on 4. And the teenagers are 17 going on 18, but the other children’s ages are unstated, so when we are told of the parents contemplating their sons or daughters sleeping or playing DVDs, it is difficult to form a picture of the size of the child they are looking at – somewhere in the 5-12 age range, but children grow a lot between those ages. So at some points there seems to be too much detail, and at others too little.

The book makes one aware of the Greek, Arab, Indian, Vietnamese and other diasporas in Australia. And that inevitably makes me think of other things that are not mentioned explicitly in the book, but perhaps are part of the the background: the obsession of the Australian media with “suspected asylum seekers”, for example. But though it is not mentioned in the book, there is also a South African diaspora in Australia. That particular one wasn’t mentioned at all at the conference either, as far as I am aware — most of those at the conference were concerned with migrants coming to South Africa, rather than leaving it.

Never having been to Australia, I have no idea how accurately it reflects Australian suburban life, but, as portrayed in the book, it seemed rather empty to me. Like the old man in the story, who reflects on his life, and how he migrated to Australia from Greece, It makes me look back on my own life, and make comparisons. And the outstanding difference was the struggle against apartheid, which dominated the greater part of my life. There seems to have been nothing like that in Australia. Of course there has been evil, there have been bad things, but they seem so petty by comparison. The child abuse of a man slapping a child at a suburban barbecue pales in comparison with thousands of children suffering from kwashiorkor, marasmus, pellagra and other nutritional deficiencies.It all seems so banal that they have to take refuge in booze, drugs and adultery.

On finishing the book one thing is pretty clear to me: I won’t be packing for Perth any time soon.

And I still haven’t made my mind up about the book. In some ways I want to give it four stars, but in others two. I think I’ll compromise and give it three.

June 25, 2012

Joint Conference on Religion and Theology (part 2)

Some more comments and observations on the Joint Conference of academic societies in the field of Religion and Theology (continued from Part 1).

One of the useful things about conferences like this one is networking — meeting other people who are working in similar fields of research, and reconnecting with old friends and meeting new people.

I was also hoping to meet some people who might be able to help me with our research project on the charismatic renewal movement in southern Africa.

Anne & Roger Tucker of the Presbyterian Church in Bloemfontein

On the first evening of the conference I met Roger and Anne Tucker of the Presbyterian Church, who had been involved in the charismatic renewal from the early days, when a group of Presbyterian ministers used to meet at Camp Jonathan in Eston, and were able to give me an outline history up to the present. Many of those I had known who were involved in it were either dead or overseas, and had been away from South Africa for so long that they were no longer in touch with more recent developments.

Roger and Anne has served in Vanderbijl Park, Port Elizabeth and Cape Town before going to Bloemfontein, so they had experience in various parts of the country.

One of the things that became apparent from our discussions also linked with some of the papers at the conference. Irvin Chetty read a paper on the New Apostolic Reformation movement, one branch of which was New Covenant Ministries, led by Dudley and Ann Daniel. Some charismatic Presbyterians, most notably the Durban North Presbyterian Church, led by its minister Charles Gordon, broke away from the Presbyterian Church and affiliated with New Covenant Ministries. This caused a backlash against the charismatic renewal movement in the Presbyterian Church.

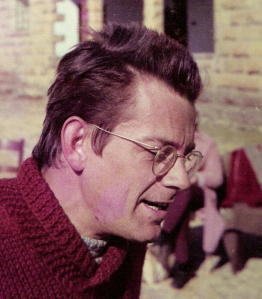

Errol (Pepsi) Narain

Another person who was involved in the early charismatic renewal was Errol (Pepsi) Narain, who had come from the USA to be at the conference. and read a paper on fundamentalism. In the audience for his paper was Ross Cuthbertson, who had been the priest in his parish when the charismatic renewal was at its height there, and later became a suffragan bishop in the Anglican Diocese of Natal. Ross is now retired, but I was able to visit him after the conference, and interview him about the charismatic renewal. Both he and Pepsi have become interested in a more generalised Western Christian mysticism, being especially interested in the works of Meister Eckhardt.

It was 30 years since I had last seen either of them, at a conference in Zululand on the charismatic renewal and the political crisis in South Africa. Ross Cuthbertson even remembered my exposition of Psalm 81/82 from that conference, and remarked that it was probably just as relevant today.

Jonathan Draper

Another old friend I met at the conference was Jonathan Draper, now Professor of New Testament at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. I had known him 35 years ago in the Anglican Diocese of Zululand, when I was responsible for post-ordination training, and he attended the training meetings. Now he is cutting down on his doctoral students in preparation for retirement. It’s getting on for two years since I had a doctoral student, and I’m beginning to feel that it would be nice to have that kind of contact with the academic world again.

The post-ordination training in Zululand was something special, though, and contributed quite a bit to the paper I read at the conference. There was one participant who had had no academic training. He had served as a lay minister for years, and had eventually been ordained. He was a big man, Posselt Mngomezulu. And at the beginning of almost every training he would start off by saying “I have a problem”, and he would go on to tell of some pastoral or mission problem, and in the subsequent discussion everyone tried to think it through theologically. If you can have pure maths and applied maths, this was applied theology, and it got people thinking theologically.

S.R. Mudau

A new and yet old acquaintance I met at the conference was S.R. Mudau, from the Lutheran Seminary across the road from the university. He told me that he was interested in liturgy, and was writing a dissertation on Lent. I was able to recommend a book that he did not know of, Great Lent by Alexander Schmemann.We discussed the differences between Western and Eastern observances of Lent.

But he knew me from when I had visited Venda in the 1980s, and stayed with Esrom Mulaudzi, and I learned that he had died last year. So we discovered that we had friends in common.

On Thursday night the Southern African Missiological Society (SAMS) had its dinner. We were one of the smaller societies represented at the conference, so there were only about 15 of us there, but it was a very pleasant and convivial occasion, held at the university staff club.

Thias Kgatla

Among those present at the dinner was Professor Thias Kgatla of the University of Pretoria. He has been been at most of the SAMS conferences I have been at over the last 20 years, though we haven’t met much on other occasions.

He read a paper on mission and forced migration. While most Christian churches opposed the forced removals of the apartheid regime, the white Afrikaans churches were generally silent at best, and for the most part supported the forced removals. Yet this was at the very time that the Dutch Reformed Church had a revival of mission interest, and a tremendous expansion of missionary work.

It was good to meet old friends and make new ones, but there were also some people at the conference that I hoped to have a chance to talk to, but somehow the opportunity never arose. Perhaps there’ll be another chance some time.

Links to other blog posts on JCRT 2012

Rock in the Grass (Pete Grassow): Indians in Natal

Rock in the Grass (Pete Grassow): Educating for Mission

Notes from underground: Luddite theology

June 23, 2012

Joint Conference on Religion and Theology (part 1)

From 18-22 June 2012 I attended the Joint Conference of academic societies in the field of Religion and Theology (JCRT 2012) , held at the Pietermaritzburg Campus of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (my alma mater – I studied for a BA there, 1963-65).

I drove down from Pretoria on Monday 18th June, and avoided the toll roads, so it probably took a little longer – 8 hours 22 minutes, to be precise, and the distance was 621 kilometres. There were lots of roadworks on some sections, especially between Leandra and Standerton, and over the Biggarsberg between Newcastle and Ladysmith. Last time I travelled this road they were working on the road over Laings Nek between Volksrust and Newcastle, but that section has now been completed.

I stayed in a self-catering cottage at the Little Europe Guest House 2 km from where the conference was being held, reasonably priced (R280 a night) and convenient.

Self-catering cottage at Little Europe Guest House – where I stayed for the conference

There were 16 participating societies, so the programme was quite complex, with several things going on at the same time. There was a fairly good representation of people from various African countries, and some overseas. On the other hand, some South Africans could not attend because the conference was very expensive.

Tea time at JCRT 2012

The conference opened with a plenary session of all the societies in the Hexagon Theatre to hear papers from Abdulkader Tayob on Islam in public life, and Madipoane Masenya women’s encounter with the Book of Ruth. She said there were not enough Boazs for single women.

Madipoane Masenya of Unisa speaking on African South African women and the book of Ruth, Gerald West in the chair

The first session on Tuesday morning had 10 events on the programme. As a member of the Southern African Missiological Society (SAMS) I thought I’d better go to our opening event, which was Dietrich Werner speaking on ecumenical networking and exchange of resources in theological education. Among their projects is a global survey on theological education, which they would like anyone involved in theological education to participate in. There is also a global theological library of online resources, which is available free of charge.

Karel August, Nico Botha (SAMS chairman) and Reggie Nel (SAMS)

The next two SAMS speakers didn’t turn up (perhaps because of the expense of the conference), but that gave me an opportunity to join in one of the sessions of the Church History Society, on Christian student groups in the 1960s and 1970s.

Christina Landman of the Church History Society

Bill Houston spoke on the University Christian Movement (UCM), 1967-1972, while Allen Goddard spoke on discipleship courses run by Hans Ferdinand Burki for the Students Christian Association (SCA), which had a profound effect on the organisation.

I found this particularly interesting, as I was involved in some of the preliminary meetings that let to the formation of the UCM, which was originally seen as a replacement for the SCA, which split up into separate racial components to conform to the apartheid ideology. This was imposed by the Afrikaans section of the SCA (CSV) which was by far the most powerful, and so could dictate to the others. UCM lasted for five years and then folded for various reasons that Bill Houston discussed. But Allen Goddard’s paper suggested that the English and black components of the SCA got together again in the 1q970s, and so to some extent fulfilled at least part of the vision of the UCM.

Bill Houston – spoke on the University Christian Movement

Bill Houston is planning to write a book on the UCM, based on his thesis, and after the papers several people (including me) urged him to broaden it to cover Christian student organisations more generally.

One of those who urged this was Anthony Egan, also of the Church History Society, who had done some research on the National Catholic Federation of Students, which was one of the bodies involved in the founding of the UCM.

Another church history paper I heard was one by Radikobo Ntsimane, who spoke on religion and health, and noted that some 19th century missionaries involved in medical missions seemed to regard Western biomedicine as somehow “sacred” and African ideas of health and healing as “profane”.

Nico Botha of SAMS said he was trying to develop a theology of migration and miossion.

I read a paper on Mission, Migration and Theological Education, looking at some attempts to provide theoloigical education for migrants involved in mission.

Afe Adogame of the University of Edinburgh spoke at a plenary session of all the societies on the public face of new African Christianities – questing for the good things in life. As he says in the abstract of his paper,

…there has been a somewhat misleading generalisation of new African Christianities as ‘apolitical’, ‘this-worldly’ and lacking any conscious ‘social agenda’. Such controversial assumptions warrant a critical re-reading of African Christianity’s role in contemporary civil society. Attention needs to be given to the dynamics of new African Christianities in generating social, cultural and spiritual capital. I argue that new African Christianities contribute enormous bridging, bonding and linking social capital, but also confront barriers to development and civic engagement.

Afe Adogame and Stephen Hayes at JCRT 2012

One of the examples he gave was one of the Neopentecostal churches, Winners Chapel, which has 300 buses that commute members to Sunday Services, and 300 people are employed as drivers. Another, Canaanland, does not have purely religious spaces, but spaces for politics, gossip and other forms of interaction. They have banks, shopping centres, and social spaces. I was able to chat to him later, and discuss some of the differences between the Neopentecostal churches in Africa and some of the more traditional African Independent Churches (AICs).

One of those reading a paper for the Church History Society was Thomas Ninan, an Indian Orthodox priest who is studying at UKZN. He arranged an interesting interlude, having tea with a group of Greek ladies who meet regularly for a study group, one of whom is a relation of one the members of our parish of St Nicholas in Johasnnesburg, Ellie Mullinos. There was also a visiting Ethiopian Orthodox deacon at the tea party.

Some members of the Pietermaritzburg study group: Atty Zaverdinos, Annalise Zaverdinos, (uinknown), Mary and Marjye Mullinos, Leeba Thomas Ninan, Fr Thomas Ninan. The children in the front are Angel (9) and Thomas (4)

I can’t comment on the papers I didn’t hear (though we were given abstracts of all the papers, even those where the speakers did not turn up to deliver them). And there isn’t space here to comment adequately on the papers I did hear. As a general comment, some of the papers I did hear tended to be overloaded with abstract nouns like “love”, “peace” and “justice”. Good words all, but sometimes concrete examples would make the presentation clearer. One that did not suffer from this fault was by Sinenhlanhla Ngwenya of SAMS, who spoke on unaccompanied refugee minors from Zimbabwe in South Africa, and in particular their vulnerability to HIV/Aids. She was very specific, and called for a pastoral response. Whether anyone will respond to the call is a different question, but there is no mistaking what the call is. The problem with the abstract nouns is that it is too easy for people to say they have responded to the call, for who isn’t in favour of good things like love, peace and justice?

Tea time at JCRT 2012

Simanga Kumalo spoke at a plenary on developing church/state relations in a democratic South Africa, and noted that there were four different bodies that had been established to maintain contact between the state and religious leaders, and all four had been started as a result of initiatives from the state, not from the religious leaders.

One person who commented after his paper made a memorable remark: at liberation we thought that sin would either take early retirement or commit suicide; but it didn’t happen.

I think I need to continue this report on JCRT 2012 in another post, so this will be part 1, with part 2 to follow.

June 15, 2012

The boy who could see demons

The Boy Who Could See Demons by Carolyn Jess-Cooke

The Boy Who Could See Demons by Carolyn Jess-Cooke

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This is not really a review, but more a response to the Good Reads review prompt “What did you think?” So I’m writing more about thoughts inspired by the book than thoughts about the book itself.

Carolyn Jess-Cooke tells us that this book was inspired by The Screwtape letters by C.S. Lewis. The Screwtape letters is Lewis’s contribution to Christian ascetical theology, and takes the form of letters from a senior demon to his junior apprentice, giving him advice on how best to tempt his patient.

In The boy who could see demons 10-year-old Alex Broccoli is being treated by psychiatrist Anya Molokova. He tells her about the demons he can see, and especialy a demon Ruen, who says he is studying Alex as a research project. The story viewpoint switches back and forth between Alex and Anya. Anya is concerned that Alex needs in-patient care, partly because his father is absent, and his mother is suicidal.

The switch in viewpoints is interesting because in a way it shows something of the postmodern condition. As Walter Truett Anderson puts it in his book Reality isn’t what it used to be:

An experience that a premodern person might have understood as possession by an

evil spirit might be understood by a modern psychoanalytic patient as more mischief from the Id, and might be understood by a postmodern individual as a subpersonality making itself heard – might even, if you want to get really postmodern about it, be recognized as all three.

When Alex is an in-patient in the institution, which has its own school, he regards some of the other children in his class as “psycho”, and is aware, at one level, that Anya regards him as a bit “psycho” too. Anya, from her professional point of view, regards Alex’s condition as a possible case of early onset schizophrenia, but at times finds herself forced to see it from his point of view, and that when he tells her things about herself that he could not possibly have known, he is speaking the truth when he says that he did not know them, but Ruen told him to say them.

This takes me back to another book I read nearly 50 years ago, The primal vision by John V. Taylor. It was on Christian presence amid African religion, and is still, I believe, tremendously valuable. It shows how Western Christianity, which has been strongly influenced and shaped by modernity, sometimes fails to cope with premodernity in Africa. One of the things that stood out for me about it is that Western culture tends to relate the causes of evil to internal things, whereas African culture tends to see them as external. So for Western culture one’s demons are all in one’s head, whereas in African culture they are in one’s environment. And it seemed to me that it is like different maps of the same territory. We all have our own constructions of reality, which differ according to our culture and experience, just as a geological and a political map of the same territory might be quite different. Nowadays, with Google maps and the like it is easier to see the different layers of maps that can be used to view the same territory.

I think I’ve mentioned before in this blog that when I was in Windhoek, more than 40 years ago, we received a letter from a group of psychotherapists in Chicago, saying that they were concerned about the mental health needs of the Third World (there was a Third World back then, though Namibia wasn’t going to be any part of it if the Nationalist government had its way). I thought about this letter for a long time. And I thought that sending a team of American urban psychotherapists to rural Namibia would be like sending a team of witchdoctors from Ovamboland to treat middle-class suburban housewives in greater Chicago. Their psychological ailments are so culturally bound that the therapists from both places would need to spend the next twenty years learning to understand the culture of their patients in order to get inside their skins.

Of course psychiatry is not just any psychotherapy, but is specifically medical. But even there, Western “scientific” medicine is bound by culture, perhaps even more bound in some ways, because of its claim to be “scientific” and therefore above subjective cultural considerations, and therefore fails to see how culturally bound it is.

Scientific medicine has made great advances in Africa, and great inroads into African thinking, but there can still be the dual viewpoint. In premodern Africa most diseases, other than minor coughs and colds, were thought to be caused by human malice expressed in witchcraft (see Tabona Shoko in African initiatives in healing ministry).

In Western medicine the germ theory of disease carries more weight. An African trained in Western scientific medicine would be aware that malaria is caused by the bite of a female anopheles mosquito that is infected by the malarial parasite, but might still ask, “who was responsible for sending that particular infected mosquito to bite me.”

To Westerners this might sound superstitious, but I recall that 25 years ago the drug Ritalin was routinely prescribed as a panacea for all kinds of ailments, including children being bored and daydreaming in class. Psychiatrists and schoolteachers alike seemed to be convinced of its miraculous properties. That seemed entirely superstitious to me.

The Africa of The primal vision lies 50 years in the past; Africa is modernising rapidly, and is a different place. People sometimes don’t realise how different it is. People talk about ubuntu as an African value, but very often seem to have forgotten what it means. There is an example of this here other things amanzi: chicken feet, hat-tip to my blogging friend Jenny Hillebrand, who also gives another example here Carpenter’s Shoes: The value of the individual.

But there are still cultural difference in the ways that illness is perceived, and perhaps, like the wave and particle theories of the transmission of light, there is a place for both.

And then there is a third way, that of Orthodox Psychotherapy by Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos, but I’d better save discussion of that for when I review that book.

June 12, 2012

This could go on for ever

I got an SMS:

Please call (number). Brought to you by MTN.

I called the number, and got taken to voice mail.

Instead of a beep and a place to leave a message, I heard:

You need not leave a message. MTN will conveniently leave a message asking this person to call you. Please press 1 to send this number or 2 to send another number.

This could go on for ever.

(Categorised under: technology, modern, blessings of)

June 11, 2012

Possible revision of Christian public holidays

The Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities will be holding public meetings later in June to discuss the desirability of retaining Christian public holidays because some have complained that these favour Christianity and discriminate unfairly against other religions. Christian public holidays face revision – Sowetan LIVE:

The public discussion meetings will take place in Gauteng, the Western Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and the Free State, according to a statement from the commission.

A number of “complaints and requests” have been received by the commission, concerning the fact that SA’s public holidays only acknowledge Christianity and discriminate unfairly against other religions.

As far as I am aware the only public holidays with Christian links are Good Friday and Christmas Day.

I read some comments from a Christian friend on Facebook urging that these holidays should be abolished and that Christians who want to observe those days as holidays should take those days as leave, which would show how sincere they are about them, and in some of the following comments by various people it was noted that these holidays affected business badly, and was destructive to the economy (I won’t link to it because Facebook is only visible to people who are members of Facebook).

I don’t have a dog in this particular fight really, because our Good Friday generally falls on a different day from the Western one, and my wife and children take leave then, or rearrange their work schedule, and I used to do that when I was working full-time too.

But that is easy to do when you are comfortable and white and middle class. It is not so easy for black working-class Christians, most of whom take Good Friday, in particular, very seriously indeed.

About 75% of South Africa’s population have claimed in censues to be Christian, and while not all take their faith seriously, quite a large number do, and most of those who do are poor and black, and make a considerable effort to go to church gatherings on Good Friday. And with Easter Monday also being a public holiday it makes it possible for churches to gather in ways not otherwise possible.

The Zion Christian Church’s Easter gatherings, when millions gather at Moria in Limpopo province, are well known, because it is the biggest Christian denomination in the country, but there are thousands of other denominations that hold similar gatherings.

I suspect that those who complain about this as “unfair religious discrimination” are a tiny minority of people who are probably, most of them, fairly well-off. And the ones who think that having these holidays is bad for business seem to me to be coming perilously close to wanting to make the worship of Mammon the established religion in the country, to which everything else has to give way.

I think the main effect of such a move would be to unfairly discriminate against people who are poor and black.

It would be very interesting to see what would happen to such a proposal if the ZCC, for example, urged its members not to vote for any political party that proposed it. And if other denominations were to join in it could perhaps have a c0nsiderable political effect.

Of course it hasn’t reached the point of being a definite proposal yet, and for the moment the Commission is still collecting submissions and holding public meetings to discuss the desirability of changing things. If you are interested in making a submission to the commission you may do so here.

I suppose that, as an Orthodox Christian, I could complain that observing Western Good Friday as a public holiday is unfair discrimination. Of course we do have Christmas, except that Orthodox Christians on the Old Calendar observe Christmas on 7th January, which is not a public holiday in South Africa.

But I won’t complain, for the reasons given above.

We Orthodox Christians are a minority, and demanding that Western Good Friday be dropped as discriminatory when it is observed by millions of South African Christians would be remarkably selfish. And it would be discriminatory primarily against those who are poor and black. It would be racist.

June 9, 2012

The Hunger Games (book review)

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

When I began reading this book, I thought it was in the same genre as 1984 and Brave New World. It is set in a dystopian future, roughly in the area of the present USA, which in the book is called Panem, and is divided into twelve districts, each dedicated to one kind of economic activity. There had been thirteen districts, but one had been wiped out in a rebellion against the Capitol, a new capital city somewhere in the Rocky Mountains. To keep the districts in line each has to pay tribute in the form of a boy and a girl between the ages of 12 and 18, who have to fight to the death in an arena, with the last survivor being the victor, and entitled to live a life of luxury from then on.

The “tributes” are chosen by lot, but Katniss Everdeen, aged 16, volunteers to take her younger sister’s place. She sets off for the Capitol with the local baker’s son, who has occasionally been kind to her in the past, realising that they might have to kill each other.

Once they get into the arena, another genre crops up, William Golding‘s Lord of the Flies, which the scene in the arena resembles. I read other three books I have mentioned in my late teens, at the age at which I would have been eligible to have been chosen for the games had I been a subject of the fictional state of Panem. I’ve read all three of those books several times since, so it’s a genre that I find appealing, and have for a long time.

Though Brave New World and 1984 are set in the future (at least, in the case of 1984, at the time when it was written) they satirise present trends in society by extrapolating them into the future. In the case of Brave New World the main trend is mass production, and hedonistic pleasure seeking. In the case of 1984 it is the surveillance society, and in both there is the bombardment of citizens by propaganda to enforce conformity to a totalitarian society. In the case of Brave New World this is done primarily by distracting people by the pursuit of pleasure and recreation. In the case of 1984 it is done by fear and threat. And in The Hunger Games it is done by both.

The present trend that is extrapolated into the future in The Hunger Games is “reality” TV shows. One of the first of these, Big Brother, deliberately recalled 1984. In The Hunger Games it is this that places it in the same genre. Another such reality TV show is Survivor.

I bought The Hunger Games because people I knew had read it and blogged about it, and their comments made it sound interesting. And as I read The Hunger Games I thought it was as good as, if not better than the others I have mentioned. I had noticed that it was the first of a trilogy, and when I was about half-way through I was thinking that it was a seriously good book, and had just about made up my mind to buy the other books in the series. I was preparing to give it four or five stars on Good Reads.

But in the end I gave it only three stars, because about two-thirds of the way into the story the author seemed to have fumbled the ball and lost the plot. The climax built up, the tension mounted, and then suddenly the whole thing just collapsed. Or so it seemed to me.

I won’t say which point I think that was, for the sake of those who haven’t read the book, and some might disagree with me on that point anyway. But if you’ve read the book, feel free to say something about it in the comments, and so will I. If you haven’t read the book, don’t read the comments until you have, or have decided not to read it; then there won’t be any spoilers.

View all my reviews

June 4, 2012

Tales from Dystopia XIII: Police riot in cathedral

Forty years ago today (and yesterday) the police rioted in Cape Town Anglican Cathedral, and arrested the dean.

There have probably been many police riots, before and since, but I think that this was the first one to take place in a cathedral in the centre of a large South African city, so it is perhaps worth remembering.

It is also one that I was only very peripherally involved in, so I hope if anyone who was more directly involved in these events reads this, they will add their own memories of the events by way of comments.

On 1 June 1972 a group of students from the University of Cape Town staged a protest outside the Houses of Parliament, and several were arrested. The following day about 400 students, lecturers and Christian leaders gathered on the steps of the Cathedral to protest against against apartheid education. The cathedral was quite near to the Houses of Parliament, but was private property. The police arrived and ordered the students to disperse. They refused, claiming they were on private property. Without warning the police baton-charged the students. They fled into the Cathedral pursued by the police who beat up the students, some of them in front of the High Altar.

There is a good description of what happened next here The Witness:

UCT students numbering perhaps 400 were sitting on the cathedral main steps protesting about racial inequalities in education. After a discussion between police colonel Pieter Crous and a student leader over the use of a loud-hailer, a large squad of policemen suddenly baton-charged. The attack instruction was given by Brigadier Martinus Lamprecht, who later appeared in a series of Cape Times photos watching a snarling police sergeant club a student already sprawled on the pavement. Interviewed on the spot, in a shaken, trembling voice Lamprecht stated that the protest had become a “public meeting” and “these people refused to move, so I gave the order to disperse them”.

The police beatings were witnessed by thousands of members of the public and over the following days received widespread condemnatory press coverage.

The Dean, the Very Revd Edward (Ted) King, ordered the police out of the Cathedral, and for the rest of the day the Cathedral was under siege. The students remained in the Cathedral and were joined by many more, while the police were outside firing teargas canisters at the Cathedral through the openings. Ted King was arrested for obstructing the course of justice as was his wife, and Theo Kotze, a Methodist minister who was Director of the Christian Institute..

The web site of the Anglican Diocese of Cape Town describes how the Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, the Most Revd Robery Selby Taylor, arrived on the scene

Later that evening into the Cathedral came Robert, he stepped into the pulpit and in a loud booming voice he began “It has been an long day and we are all very tired. The police have given me an undertaking that if we leave quietly we will not be molested. I therefore suggest you leave singly or in very small groups. Good night and God bless you.” And then almost as an after thought, he continued “By the way there is a service here tomorrow morning at 08h00, so would you please tidy up before you leave.” The calming effect which he had on that situation was quite amazing in fact almost surreal.

I had been in Cape Town a couple of weeks earlier, but missed these events, and was back in Pietermaritzburg, where students held protest demonstrations against the police riots in Cape Town. This is what I wrote in my diary 40 years ago:

Monday 5 June 1972

I went to town and bought newspapers. Friday’s police riot in Cape Town is still front-page news, and all sorts of protests are planned for today, including another one at Cape Town Cathedral.

I went home and wrote a little leaflet on “Church and community crisis”, an adaptation of something in the Free Church Collective Handbook published by the Berkeley Free Church, about first aid and defence against tear gas. I took it up to the university and gave it to John Morrison in the SRC office. News came that several people were arrested at Wits after an illegal march into town.

I went home and in the afternoon wrote letters and then walked into town. I walked past the Cathedral and there were about 150 students standing with placards, doing exactly what they had been doing in Cape Town last Friday, but this time the police weren’t rioting; there were just a few SB guys watching. I walked past the SB office and there were a whole lot of SB guys standing in what looked like a silent demo on the SB office steps, about 15 of them, all looking solemn in the rain.

On that occasion, at least, there was a marked contrast between the behaviour of the police in Cape Town and Pietermaritzburg.

The commemorative article in yesterday’s Witness, which is well worth reading, goes on to say:

The fact that a central Anglican building of worship had also been so defiled cut no ice with Prime Minister John Vorster who was quoted as saying “he was proud of his police” and he warned English-language universities “to get their house in order” or face extreme legislative sanctions.

National Party politicians liked to claim that they were defending “Western Christian civilization”, but on this occasion at least it was clear that the police were behaving like heathen barbarians.

Ten centuries earlier the heathen Danes invaded Kent, captured Canterbury, beat up and killed many of the citizens, and set fire to the cathedral. They captured the archbishop, Alphege, and demanded that the citizens pay a ransom for his release. Alphege refused, saying that the poor should not be burdened with having to pay for his release. The drunken Danes, celebrating their victory, pelted him with bones from their feast and beat him to death. His tomb is in Canterbury Cathedral, and bears the epitaph “He who dies for truth and justice dies for Christ”.

No one died in the police riot in Cape Town cathedral, though the savagery of the police was little different. But five years later Steve Biko died in a similar manner to St Alphege, and he surely deserves the same epitaph.

Postscript

A rather minor postscript to the story is that I thought that if a church building was defiled by bloodshed, as Cape Town Cathedral had, it needed to be cleansed or exorcised or something, but nobody seemed to be concerned to do that with the Cape Town cathedral. There were certainly no press reports of such a ceremony taking place.

I tried to learn more about this, and having seen that the publications department of the Anglican Church had advertised for sale a Rite of Exorcism I wrote to them to order a few copies. They responded by sending me their entire stock, without charge, saying that as no one had ever ordered a copy before, and I was the only one to do so, I might as well have all the extant copies.

When they arrived, however, I was disappointed to see that the rite was concerned only with the exorcism of demonised persons, and had nothing to say about the cleansing of defiled church buildings. I had to abandon my mental picture of the Archbishop of Cape Town, in full canonicals, wreathed in clouds of incense, solemnly exorcising the evil spirits of the apartheid police.

This can be the excuse for adding more quotes from John Davies’s book The faith abroad, which I reviewed recently:

Catholics who are competent in exorcism assert that, in their experience, demon-possession of individuals is very rare. And we have to acknowledge that the theologians who have tried to delete the demonic from our contemporary Christian witness have done so because they have been horrified by the terribly destructive effects of incompetent exorcism when practised on individuals. Unless we handle the exorcism stories in the gospels in this corporate style, we will find them being claimed by people who want to find in the Gospels a licence to get involved in the secret and irrational world of the occult, or who find satisfaction in diagnosing themselves, as individuals, to be possessed by demons. In my experience this self-diagnosis never accords with the marks of demonic possession as recognized by Jesus. But this is not to deny the reality of our supernatural warfare. There are demonic forces which threaten human beings, and the church is called to recognize and attack them. Every baptism is an exorcism, an attack on the powers of darkness, and every baptized person is enlisted as a member of the exorcizing community.

And, with special reference to the policemen who attacked the students on that occasion (and later, more seriously, in Soweto in 1976)

There are millions who are now victims of racism. I do not mean the victims of policies of low wages, migratory labour and racial injustice. I mean those whose minds are so attuned to racist lies that they cannot see the truth either about themselves or those they oppress. You can no more blame a young white man growing up in the Orange Free State for thinking that blacks are inferior than you can blame the man in the Gadarene graveyard for talking with the voice of Legion. But that does not mean that you fold your arms and say, “It’s hopeless.” Like Jesus you attack the demon and cherish the demon’s victim. This may look, to the rigid followers of political ideology, to involve compromise and blurred edges. Perhaps. But the use of demon-possession as a political and therapeutic model can save us from the propensity of some political activists to see everything in terms of blame and guilt. A moral intensity which insists on locating guilt, especially on especially on maximizing the guilt of one’s ideological adversary, is in a literal sense satanic; it positively depends on the enemy being as bad as possible, and therefore one sets oneself up in business to be a tempter. So those who try to solve problems by means of this sort of moralism themselves become victims of a kind of ideological demon.

But I had to become Orthodox to find the fullness of the Christian faith, and the missing thing that I looked for in vain forty years sgo. The Book of Needs (Trebnik) has prayers for the opening of a church desecrated by pagans or by heretics. Here is one of them:

O Lord, our God, who hast shown this temple to be Thy dwelling place, by the coming of Thy life-giving Spirit in the precious chrism, who didst sanctify the prophets and apostles: For the sake of our sins it has been permitted by Thee that Thy most pure altar be desecrated by those who, out of renunciation and impiety, have troubled and torn the Church of the most-pure Gospels, and of the traditions of the Apostles, Fathers and the Righteous.

Do Thou Thyself again, with merciful eyes, accepting us of the True Faith who have come unto Thee, and who, in repentance, have confessed our sins committed knowingly, and who desire to offer the pure and bloodless sacrifice to Thee in it, cleanse it from the defilement of them that have abused it, and, as Thou Thyself only art pure, manifest it, as it was before, filled with purity and the super-essential holy things, and as Thou only art able to sanctify them that Turn theitr hearts unto Thee, purify us also most completely from the counsels of the evil one, and of every doubt and division of thought. For Thou art our sancrification, and unto Thee do we send up glory: to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.

________________

Click here for more Tales from Dystopia.

June 2, 2012

Liza of Lambeth (book review)

Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham

Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This is Somerset Maugham’s first published novel, and of those of his that I’ve read, I think I like this one the best. About 12 years ago I bought several of his books cheap at a library sale, put them on a shelf and forgot them, and in the course of tidying the shelves I took them down to read, so I’ve been reading one after the other.

Liza of Lambeth is based on Maugham’s experience as a medical student in a poor part of London. Well it’s poor in parts. I once went to a garden party at Lambeth Palace, the London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and there’s nothing poor about that!

Liza is a young girl, a teenager, 18 years old, who saves enough from her job in a factory to buy a new dress, which she wears to a street party and has a jolly good time. Her mother, who is a bit of a hypochondriac, and also a bit of a boozer, thinks the money would have been better spent on booze for herself. But Liza is happy and carefree, and enjoys herself. And her joy and love of life are infectious, and spread to others.

Liza is a young girl, a teenager, 18 years old, who saves enough from her job in a factory to buy a new dress, which she wears to a street party and has a jolly good time. Her mother, who is a bit of a hypochondriac, and also a bit of a boozer, thinks the money would have been better spent on booze for herself. But Liza is happy and carefree, and enjoys herself. And her joy and love of life are infectious, and spread to others.

But gradually things start going badly for Liza. This partly because of her own choices, and partly because of the pressures of other people and society generally.

To say any more of the story would give away too much of the plot, but I will say that it still today, more than a century after it was written, gives an insight into the lives of poor people and the conditions in which they live. It’s an outsider’s view. As far as I know Somerset Maugham didn’t grow up in poverty himself, so he writes from observation, not from first-hand experience. And it is pretty good observation.

But books like this are probably not read by the poor. They are probably read mostly by fairly comfortable middle-class people like me. And from what I have observed of the life of poor people, though the time and the place may be different, there is much that is similar.

To give just one example, it’s the people in the streets. The book is about the inhabitants of one street, and they meet each other and talk to each other in the street. They sit on their doorsteps and talk to their neighbours.

Earlier this week I had a couple of hours to kill while my son wrote an exam, so went to visit a friend who lived nearby. Their gate was locked, so I called them on my cell phone, but there was no reply, so I thought I might as well sit in the car in the street and read my book.

It was a lower middle-class suburb. The houses were not pretentious. They were originally built by the Iskor steelworks nearby for housing their white workers, and were later sold off. But they had pleasant gardens and the street was quiet. Only one car passed. There was a tapping on the car window. It was a rather agitated bird, wondering what I was doing there. I waved and it and it went away. Two fat pigeons ambled across the street. A dog barked. In one of the houses nearby a baby cried briefly. A young black woman in a hoodie came walking over the hill and passed me, but there was no interaction between us. Another black woman with hair extensions came walking up the hill and went into the house over the road. But for the most part, nothing happened. And in our neighbourhood it is much the same.

But when we visit Mamelodi, a “previously disadvantaged” township, there are always people walking in the street, talking to each other, greeting neighbours. There are children playing games, hopscotch, cricket (as in Lambeth), football etc. On Sundays (which is when we mostly go there) a phrase from a poem I learnt at school comes to mind, “man’s heart expands to tinker with his car.” There are cars with bonnets up, cars being washed. On some Sundays there’s a Golf club — rows of Volkswagen Golfs with their bonnets up, with the owners hanging around discussing technical points.

The houses may be different, the language may be different, the clothes may be different, the time and the place may be different, but Maugham’s descriptions still ring true.

May 30, 2012

The faith abroad, by John Davies (book review)

The Faith Abroad by John D. Davies

The Faith Abroad by John D. Davies

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

In some ways it seems strange to be reading a book published 30 years ago for the first time, and more so because I know the author, and he used a story that I had told him in the book. Perhaps he told me about it and I forgot, or perhaps he forgot to tell me about it, because if I’d known about it I would almost certainly have cited it in my Master’s dissertation and my Doctoral thesis.

At the time he wrote the book John Davies was head of the College of the Ascension in Selly Oak, Birmingham, UK. Its task was missiological and missionary (we would now call it “missional”) training for the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (USPG), one of the bigger Anglican missionary societies. It worked together with other colleges in Selly Oak, sharing resources and providing a wider experience for students. Originally the college was intended for training British missionaries to prepare them for work overseas, but John Davies and others shifted the emphasis so that a good proportion of students came from overseas for training.

John Davies and his wife Shirley had also worked in South Africa for 12 years, as missionaries of USPG. They worked in a variety of seetings, including the Afrikaner mielielande around Evander, and Empangeni in Zululand, and finally as Anglican chaplain of Wits University from 1963-1970.

Shirley Davies once explained to me that they were “missionaries”, and I said something like “aren’t we all?” And she said no, they were the old-fashioned kind; they had been sent by USPG, and were expected to send USPG an annual report of their activities. And that revealed to me one of the big differences between Anglican conceptions of mission in Britain and South Africa. In Britain, in the 1960s, “missionaries” went “abroad”{ (hence the title of the book) whereas in South Africa mission was what the church did when it wasn’t sitting in its pews. A former Anglican bishop of Johannesburg, Ambrose Reeves, told me that it was precisely for that reason that he had invited John Davies to come to Johannesburg in 1958.

And in his book John Davies explains the implications of some of these things. Missionaries who went from the UK to southern Africa in the second half of the 20th century were not, for the most part, engaged in primary evangelism. For the most part they became part of the local church and took part in its activities. John Davies does mention an exception to this – Ronald Wynne, who planted a church among Humbukushu refugees in Botswana. But for the most part the churches were already there and planted, except when the ethnic cleansing under apartheid got going. Then both the local-born clergy and the “missionaries” from overseas were for the most part caught flat-footed.

And in his book John Davies explains the implications of some of these things. Missionaries who went from the UK to southern Africa in the second half of the 20th century were not, for the most part, engaged in primary evangelism. For the most part they became part of the local church and took part in its activities. John Davies does mention an exception to this – Ronald Wynne, who planted a church among Humbukushu refugees in Botswana. But for the most part the churches were already there and planted, except when the ethnic cleansing under apartheid got going. Then both the local-born clergy and the “missionaries” from overseas were for the most part caught flat-footed.

In the UK, before coming to South Africa, John Davies was involved in a revival of parish life, and the sense of the parish church as a “mission station” in the parish of Halton, in Leeds. This is described in The parish comes alive by Ernie Southcott. It pioneered house churches, not as an alternative to the parish chruch (as they tended to become in the 1980s) but as an essential part of parish life.

In all this I have been talking about the author, and not said much of the content of the book, though some of these things are mentioned in the book in passing.

To me the book was well worth reading, and I’d be tempted to quote the whole book, given half a chance. But after seven years as a university chaplain (in which his bishop told him he was the most expensive priest in the diocese) and then as head of a missionary training institution, John Davies had some interesting reflections on academia and academic teaching, on scientific objectivity and the disinterested search for truth, which are worth repeating:

A church which is motivated by mission will be cautious about the academic claim to be disinterested or value-free. It will recognise that such a claim is a necessary aspect of academic freedom, with an importance which will be obvious to anyone who has seen what can happen when a university becomes merely a servant of a national ideology. But the ideal of a “value-free” or “scientific” pursuit of truth can also encourage people to be refugees from the world of struggle and commitment. Christian faith has to insist that the search for truth is not isolated from the needs of those who most need the changes which truth should bring — those for whom the structures and habits of the present order are a lie and a denial of the truth. A church which is motivated by mission will ask in whose interest the university exists; it will try to discover whether its presence is truly to the advantage of the poor or whether it is concerned primarily with the interest of its own minority. Particularly in the area of theology, a church which is inspired with the vision of the Body will ask whether a university’s theology is contributing to the power and prestige of an “expert” class, or whether it is contributing to the enabling of the whole people of God.

And, as an Orthodox Christian, I found it interesting to see how what he wrote was so relevant to Orthodox missiology, expecially the relation between mission on the one hand and liturgy and worship on the other. Near the beginning of the book he remarks that there are three parts of the mission process, or functions in the operation of the church:

Healing, reconciliation, boundary-breaking, an overthrow of forces that obstruct God’s design in creation (Acts 2:1-13)

The communication in words (Acts 2:14-39)

The formation of the community (Acts 2:40-47)

And then he says of worship:

Any consideration of mission must give major consideration to worship. But worship is not a fourth function to be tacked on to the other three. At every point it enables and underlines the other three. To fail to acknowledge this would be connive in one of the greatest causes of weakness in the church, namely the separating off of function from function, and the isolating of worship as just one among several options. Worship is the fundamental affirmation of the values which underlie all the programme: worship itself is turned into a self-justifying hobby unless the connections are stressed. And the rest of the programme grows weak in motivation unless the underlying values are renewed.

And again, towards the end of the book, he notes that mission is thankfulness (ie eucharist), not so much thanks for the things that distinguish us from others, for blessings like health, sanity or success in exams, but for the things we have in common with them.

The great thanksgiving in the eucharist requires us not to be thankful for the things which distinguish us from others, but for those things we have in common with others, our createdness at the hand of God, and the action of God in Christ through the Holy Spirit towards us and towards the whole human race. The Eucharist is a disciplining and a training of our motive and our self-image so that we find ourselves able to say, and to mean deeply, the simple prayer of Thomas Merton, “Thank God that I am as other men are.”

The eucharistic thanksgiving depends entirely on the nature of God as disclosed by Jesus. It is an approach to the Father through the Son.

And when one hears the Liturgy of St Basil, that is exactly what it is.