Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 73

March 10, 2012

Bible Seminar

Last Thursday I went to a seminar on the topic Which Bible is the normative "Word of God": Christians and their differing Bibles.

I was asked to speak on The coming-into-being, composition and authority of the Greek Orthodox Bible, but saw among the list of other speakers and participants a bunch of learned New Testament and Old Testament scholars, and, as a mere missiologist, I felt a bit like Daniel in the lion's den. In addition, I discovered that I was the only Orthodox Christian among a collection of Dutch Reformed dominees. The only other non-Orthodox there, as far as I could see, was the former Roman Catholic Archbishop of Pretoria, George Daniels.

Bible Seminar at Linquenda Landgoed

The first speaker gave a bird's eye view of the coming-into-being of the Bible, which pretty much covered all I could say on the subject, and the speaker after me was talking about theSeptuagint (in which he is a specialist), so I decided to do my missiological thing, and talk about the Bible in culture. So I changed the title toThe Bible in the Orthodox Church, and spoke about the cultural differences between the ways in which Orthodox and Protestants approached the Bible.

One of the biggest differences, of course, is that Protestantism came into being in a world in which there was a Bible. Before Gutenberg's invention of printing in the 15th century, and the publicatrion of printed Bibles, "The Bible", as a book you could hold, open, wave about or thump to emphasise a point, simply did not exist. The Orthodox Church never had a Bible. Instead it had "the Holy Scriptures", plural, and so one of the biggest differences between the Orthodox and Protestant approaches to the Bible is the difference between a manuscript culture and a print culture, the difference between communal reading and private, individualistic reading. If you're interested in reading a summary of what I said, you can find it here.

Bible Seminar at Linquenda Landgoed

It was a very pleasant gathering, however, and I think I learnt quite a lot from it. It was held at Linquenda Landgoed, somewhere between Broederstroom and Lanseria Airport, and it was arranged between an ourfit called Scriptorium and the Department of New Testament at the University of Pretoria. The are planning to hold similar gatherings in future, but as it was mostly in Afrikaans, I think that if they need another Orthodox speaker, I'll suggest that they invite Fr Kobus van der Riet.

And for Afrikaans-speaking people who would like to know more about Orthodoxy, see here Bedehuis Bethanie | Kerk van die Heilige Maria die Egiptenaar

March 5, 2012

Neal Cassady biography (book review)

Neal Cassady: The Fast Life of a Beat Hero by David Sandison

Neal Cassady: The Fast Life of a Beat Hero by David Sandison

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Some years ago I read another biography of Neal Cassady, The holy goof by William Plummer. The only book that Neal Cassady himself had published was a partial autobiography, The first third, so this is not a literary biography in the sense that Cassady was a famous author. His claim to (literary) fame was that he appears as a character in the novels of his friend Jack Kerouac and the poems of his friend Allen Ginsberg, and also in Go by John Clellon Holmes.

Kerouac and Ginsberg admired him tremendously, and he influenced their writing in several ways. He was the protagonist of Kerouac's On the road, thus providing the subject matter, but he also influenced Kerouac in his style of writing.

But reading the biography makes it difficult to see what others found to admire about Cassady. He doesn't really seem to live up to the epithet "holy". The "holy goof" has echoes of the saints called "holy fools", whose sometimes bizarre behaviour shocked respectable people. But this biography is perhaps a more sober one than Plummer's, and Cassady comes across as above all selfish and manipulative, and it is difficult to see how he managed to inspire such devotion and admiration in his friends. Perhaps the biography fails to capture some essential element of Cassady's character, or perhaps his friends failed to see what he was really like.

March 2, 2012

In a monastery garden

The Monastery of the Descent of the Holy Spirit near Pretoria has had its ups and downs since it was founded just over ten years ago. Hieromonk Seraphim has the pastoral care of the parish of Klerksdorp, and so is not in full-time residence. A young man, Justin, who is testibng his monastic calling, is in France studying ikonography. Another young man, Nikhon, stays at the monastery and looks after the church, and leads prayers if there is no priest, but does not think he is called to a celibate life.

The main church at the Monastery of the Descent of the Holy Spirit

Looking west from the monastery garden. On the left is the fig tree from which fig preserves are made for visitors

Monastery of the Descent of the Holy Spirit: Trapeza, bell tower and chapel

In a monastery garden

It is a quiet place, and a good place to come to pray.

February 26, 2012

A writer at war: letters and diaries of Iris Murdoch (review)

Iris Murdoch: A Writer at War: Letters and Diaries, 1939-1945 by Iris Murdoch

Iris Murdoch: A Writer at War: Letters and Diaries, 1939-1945 by Iris Murdoch

This book has three parts: a diary Iris Murdoch wrote as part of a student theatre company touring in the vicinity of Oxford just before the Second World War broke out, and correspondence with two friends during and immediately after the war — Frank Thompson, who was perhaps in love with her, and David Hicks, to whom she was briefly engaged, until he broke it off and married someone else.

The diary is quite a lively description of a travelling theatre company and those involved in it. Though war was imminent, it doesn't seem to have had much effect on Iris, then a communist, and rather opposed to war because of the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact.

The correspondence with Frank Thompson is more interesting, however. Iris Murdoch had then left university, and begun to work in the Treasury in London, while Frank Thompson, a Captain in the British Army, was serving in "the Middle East" — a rather vague term, reflecting wartime censorship.

For the most part we see both sides of the correspondence, though some letters are missing, and what stands out is that Frank Thompson's letters are far more interesting than Iris Murdoch's. Though the sub-title is "A writer at war", the war seems to impinge very little on her life. Her life seems undisturbed by air raid warnings, rationing, or any of the other characteristics of life in war-time London that one reads about in other books. It hardly seems to touch her at all, and her letters are quite uninformative.

Frank Thompson's, on the other hand, and very informative and interesting.

At one point he describes listening to Radio Moscow (perhaps from Tehran), in October 1942:

…From 10:30 to 12:30 at night I can pick up Radio Moscow on the wireless. From 11 onwards it send the news at slow dictation speed, and I find I can understand nearly every word. The reason for this slowness is that this programme is providing front-page copy for local newspapers all over the Union, whose editors tune in and take it down word for word. It is amusing to feel oneself at one, crouching over a small wireless at midnight, with the editors, fat and bearded, spectacled and cadaverous, small and electric, of the 'Kuznetsk Kommunist', the 'Bokhara Bolshevik', and 'Tomsk Truth'.

It's a marvellously evocative picture of one small scene during the war, but Iris provides nothing even remotely similar.

He tells entertaining stories retailed to him by an Armenian refugee who taught him Russian. On another occasion he writes:

I have spent all this Sunday afternoon sitting at a cafe with a Pole, meditating on the basic sadness of life. He let me read a letter from Tosia, his fiancee, who is still in German-occupied Poland. The dry ink itself seemed to ache with restrained longing and a courage that was only maintained by the most rigid self-control. Cut out all sententiousness about strength through suffering. Think of the millions of people to whom this war has brought nothing but utter irredeemable loss. Piotr and his Tosia are both close on forty. If the war leaves them botth alive and sane, they will still find little peace in an embittered and factious post-war Europe. For us, who are young, and have the faith that we can recast the world, the struggle that comes after will be bearable. But I feel deeply for the countless peaceable people, who can never because of age, or upbringing and environement which is as fortuitous as anything else in this world, be wholly with us and will never know peace in the one short life allotted to them.

Now that's a writer at war!

Iris Murdoch, on the other hand, just writes demanding more news, complaining that she hasn't had enough, and occasionally writes about her inner states, but rarely gives any news herself, other than that at one point she lost her virginity, and that a couple of friends got married.

Frank Thompson eventually went to the Balkans to assist the partisans on the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border, and was captured by Bulgarian fascists and shot.

From the few glimpses one sees in his letters, one wonders what sort of writer he might have been had he survived the war. I suspect that he might well have outshone Iris Murdoch.

The correspondence with David Hicks, towards the end of the war, is less satisfactory. We see only one side of it for the most part. Presumably David Hick's letters have been lost, except for the last, explaining why he has broken off their engagement to marry someone else.

Iris Murdoch had by this time left the Treasury, and gone to work with UNRRA, trying to sort out the lives of millions of displaced people (DPs) whose lives had been disrupted by the war. She was based first in Brussels, then in a monastery in the Netherlands, then at Salzburg, and finally at Innsbruck in Austria, where UNRRA had commandeered a hotel for its workers, halfway up a mountain, a funicular ride from the town, and a cable-car ride from the top of the mountain.

It's at this point that Iris begins to become a writer. In her letters to David, apart from her declarations of love and longing, she describes the characters in her novel and how they are developing. She complains that he doesn't write, and is unsure whether he was in Prague or Bratislava. It turns out that he was at the latter, working for the British Council. She wants to know what life is like there — whether the trams are running, whether it is possible to buy books, and so on. But that just highlights the fact that she says nothing about whether the trams are running in Innsbruck, and she tells very little about life there. She feels sorry for a Yugoslav boy who ran away after crashing an UNRRA truck, but doesn't describe him nearly as sympathetically as Frank Thompson does the Polish refugee.

The letters become more and more impassioned with longing, while all the time one knows that David Hicks is going to jilt her. But her longing for him doesn't stop her from having an affair with a French fellow worker, which she hopes David won't mind. He probably didn't, because by the time he got the letter telling him this, he'd already written his letter breaking off their engagement.

As a kind of footnote, I was interested to see that in the diary section Iris Murdoch mentions that Norrie McCurry came to see one of the performances of the Magpies, their travelling theatre group. She says nothing more about him by obviously knew him at Oxford, and perhaps in Belfast. Twenty-five years later, when I was at St Chad's College, Durham, and nearing the end of my time there, a fellow student, Alan Cox, was also ending his time and, about to be ordained in the Church of England, was looking for a parish to "serve his title", as they used to say.

The principal of St Chad's, John Fenton, recommended that he call on Norrie McCurry in Leeds, to see if he could serve his title there. I don't know whether he ever did get to meet Norrie McCurry, and in the end he served his title at Redditch, near Oldham in Lancashire. But it appears that Norrie McCurry was one of those parish priests who was a legend in his lifetime, and for years after he had died as well. Someone mentioned him recently in a comment in one of my other blog posts.

February 21, 2012

A missional church? Orthodox Church of St Nicholas of Japan, Brixton, Johannesburg

Last Sunday after the Divine Liturgy our parish had its Annual General Meeting, where various people reported on the state of the parish. There were the usual kinds of things at such meetings for a small parish — concern that expenditure exceeded income and so on. There were a couple of comments on fund-raising, but what I found interesting, and unusual, and refreshing was that most of the discussion was not on how money was to be raised, but rather on how it was spent. And one of the biggest items on the budget was outreach.

This post is not a report on the AGM, but rather a report on thoughts that it provoked in me, and reflections on the 25 years of existence of the parish.

Fr Athanasius Akunda

The parish priest, Fr Athanasius Akunda, gave a comprehensive report on the outreach ministry that he and others in the parish were involved in, from helping struggling mission congregations to caring for the poor and destitute.

Several people commented that the parish was, more than at some periods in the past, fulfilling its original vision of being a missional church. The aim of the community of St Nicholas was to be a place where Orthodox Christians in Johannesburg could worship in English, and to be a multiethnic community where people of all ethnic backgrounds would be welcome, and to make the Orthodox Christian faith better known in South Africa, and to be a South African Orthodox Church.

When we started there was some discussion about who the parton saint of the should be, and after discussing several saints, we chose St Nicholas of Japan. He was a Russian missionary who went to Japan in 1861, and planted a Japanese Church. There were never more than 5-6 Russian missionaries in Japan — most of the work of evangelisation was done by Japanese Christians themselves. St Nicholas saw his main role as teaching leaders who would in turn teach others (as in II Tim 2:2). We wanted a truly South African Orthodox Church, so he seemed a good example to follow.

Some members of the St Nicholas parish family in the early days (Pascha 1989) gathered to celebrate the receiving of some new members into the Church

The parish has remained small over the last 25 years. The average size of the congregation at the Divine Liturgy on Sundays has been about 30-70, and at Saturday Vespers about 15-20, and we usually received new members at Pascha, often on Holy Saturday, sometimes with a party on Easter Monday to celebrate.

Yet the parish has probably raised up more people eho are engaged in active Christian ministry than any other parish in the Archdiocese of Johannesburg and Pretoria (most of which are far bigger and wealthier). But God has taken most of these people away to work in other places.

There have been four parish priests in the last 25 years, all of them from other countries:

Fr Chrysostom Frank (American)

Fr Bertrand (Iakovos) Olechnowicz (American)

Fr Mihai (Mircea) Corpodean (Romanian)

Fr Athanasius Akunda (Kenyan)

When we started, we met in an Anglican church hall in Fairmount, in October 1987. Then we were given the use of a chapel at St Martin's in the Veld Anglican Church in Dunkeld, Johannesburg.

Pascha 1988 at St Martin's in the Veld, Dunkeld

Then in 1990 we began to use a Russian chapel in Yeoville, until, at the end of the year, we bought an old Pentecostal Church in Brixton, Johannesburg (the Brixton Tabernacle), and that has been our home since then.

There was a small but steady flow of new members being received into the Orthodox Church.

New members being received on Holy Saturday, 1992 - Sean Noel-Barham and Zwelinzima Nyathela being chrismated

The inflow of new members was balanced by the outflow. Some people who were members of the parish in the past are now priests or deacons, but are now serving in other places. Jonathan Proctor is now a priest in St Paul, Minnesota in the USA. At least one has entered the monastic life.

Andrei Kashinski and Fr Chryosostom Frank

One of these was Andrei Kashinski. He grew up in Russia in the Bolshevik period, and was a leader of Komsomol, the communist youth movement, and worked as a factory manager. Then his life was shattered when his wife left him, so he decided to emigrate to get as far away from the scene of his sorrows as possible, and came to South Africa, and was baptised just before leaving Russia, though with little catechesis, as after the fall of Bolshevism thousands in Russia were being baptised.

Someone he met in a bar in Aliwal North said "I know someone who belongs to your church", and drove Andrei to the other end of the Free State, to Parys, where he met Danie Steyn, then a member of St Nicholas parish. So Andrei began to attend St Nicholas and learned the rudiments of Orthodoxy, and then decided to return home to Russia.

He went to the Danilov Monastery in Moscow, and asked to be allowed to sweep the floors. The Abbot asked him about his previous experience, and on learning that he had been a factory manager, both in Russia and South Africa, put him in charge of the rebuilding programme. In the Bolshevik period the monastery had been used as a reformatory for juvenile delinquents, and when the buildings were returned to the church by the state they were in very poor condition, and lots of rebuilding was necessary.

For a while Andrei thought of becoming a monk himself, but then met a girl and fell in love and married her. He was ordained as a parish priest, and now serves in a small country parish.

Fr Kobus van der Riet came to Orthodoxy at St Nicholas, and was ordained and now serves at the Church of St Constantine & Helen in Eldorado Park. Fr George Cocotos, then a deacon, ran a soup kitchen in central Johannesburg, and one of those who came to it, Phillip Marcos, was interested in Orthodoxy. Deacon George sent him to St Nicholas, and he and his son were baptised. Phillip gathered a number of people in Eldorado Park who used to come to St Nicholas, and many of them were baptised at St Nicholas by Archbishop Seraphim in July 2001. Eventually there were enough people from Eldorado Park to start a new parish there, and a house was converted into a church, and Fr Kobus celebrates the Divine Liturgy in Afrikaans, since most of the people there are Afrikaans-speaking.

Baptism at St Nicholas, July 2001. Most of those baptised on this occasion were from Eldorado Park

Dr Eddie van Wyk, a psychiatrist from Cape Town, used to visit St Nicholas when he could, from 1500 kilometres away. Eventually he too became Orthodox, and established an Orthodox retreat centre near Robertson in the Western Cape, and he is now Father Zacharias, and there too they have the Divine Liturgy in Afrikaans.

Olga d'Amico, a former parishioner, is now in a monastery at Serres, near Thessaloniki in northern Greece.

These are just a few of the stories that show that the Church of St Nicholas has acted as a kind of conduit, taking people in, and then sending them out again for ministry in other places, sometimes on other continents.

The first priest, Fr Chrysostom Frank, served from 1987-1996, and when he left there was a period of a little over a year when there was no priest. We nevertheless kept the church open, with Reader's Services, and occasional visits by priests from other parishes, especially Fr Alexandros from the neighbouring parish of Sophiatown, who is now Bishop of Nigeria.

Fr Bert (Iakovos) Olechnowicz came from the USA in 1988, and left at the end of 2001. There was again a problem of no priest, and Fr Mihai Corpodean, who had come to serve the Romanian community, but had no church, came to help us, and most of the Romanians joined in. When he left, Fr Athanasius again came, initially in a temporary capacity, along with various other work he was doing, but gradually became more permanent, as described above.

At times people in the parish have not always been happy about the outreach ministry, and sometimes there have been grumbles about various aspects of it. All this for other people, but we don't get much benefit. It has sometimes been rather grudging.

But at this annual general meeting there was a different atmosphere. People were pleased to see that the biggest item on the budget was outreach. And if money was short, well, we would just have to find more from somewhere.

One of the other big items on the budget now is housing for the parish priest. Fr Athanasius originally came to South Africa to help at Soshanguve, where the leaders of the African Orthodox Church had decided that they wanted to join the Patriarchate of Alexandria. Then it was decided to open a Catechetical School cum Seminary in Johannesburg, and a house was bought in Yeoville for that purpose, and Fr Athanasius moved there to be deputy dean. When Fr Mihai Corpodean and his family left South Africa to go to New Zealand, Fr Athanasius began to look after St Nicholas, and when the seminary was closed, he bscame its full-time parish priest, but now the seminary building has been sold, and he has nowhere to live, and so the parish is looking for suitable accommodation for him.

Fr Mihai (Mircea) Corpodean and family

Because St Nicholas was the first English-speaking Orthodox parish in Gauteng, it has tended to be rather eclectic, drawing people from all over Gauteng and beyond who want English serrvices. But the parish has become increasingly aware that there are relatively few local people in the church, from Brixton and surrounding suburbs — Auckland Park and Melville to the north; Hurst Hill, Newclare and Coronationville to the west; Crosby and Mayfair to the south; and Vrededorp and Cottesloe to the east. Those areas are thus our primary mission field. So some parishioners have done outreach in those local areas too.

One of the early objects of the mission Society of St Nicholas, which preceded and founded the parish, was to encourage the development of a truly South African Orthodoxy — not Greek or Russian or Serbian or Romanian, but drawing on all these traditions but also developing an indigenous Orthodoxy. What has happened, in fact, is that the parish has remained very cosmopolitan. On a typical Sunday there are people whose origins lie in Congo, Cyprus, Greece, Kenya, Malawi, Romania, Serbia, Zimbabwe and other places, and on some Sundays South Africans are less than half the population.But that, perhaps, is also an important witness in a society in which Xenophobia has sometimes been overt and violent, and even when it isn't, is still simmering not far below the surface.

And just last month a security guard, who lives in Brixton but hails from Limpopo Province, was baptised, and perhaps he can add another liturgical language, Tsonga, to our repertoire.

February 18, 2012

Capitalist ecclesiology – is its victory complete in the West?

The consumerist approach to religion seems to have stormed one of the last strongholds. For a while now the GetReligion website has been a kind of watchdog on media religion reporting, at least in the US. Their thesis is that the media generally don't "get" religion, and that stories with a religious angle are likely to be distorted as a result. But when I saw this article, I realised that all is lost So what sort of Anglican are you? | GetReligion:

There is an on-going fight over the Anglican brand in the U.S. between the Episcopal Church and the ACNA. The Episcopal Church is the "official" Anglican franchise in the U.S., but the ACNA is recognized by a majority of the world's Anglicans too as being a bona fide Anglican church.

It's bad enough when journalists refer to sports teams as "brands" and "franchises" (they were still "teams" until about 2-3 years ago, the change is relatively recent). But when a website that is a self-styled watchdog on the media actually introduces such language, things have really gone too far.

Now maybe I'm just a crusty old curmudgeon, a retired English editor exemplifying prescriptivist old-fogeyism, demanding that people write "proper" English.

But I think it is more than that. I don't think I'm just writing as an English editor, as a language purist.

I think I'm writing as a missiologist, as a theologian. Call me a crusty curmudgeonly old pedant if you like, but I'm concerned about this phenomenon at the theological rather than just the linguistic level.

As a missiologist I'm concerned with Christian mission, about how Christians proclaim and live out the good news of Jesus Christ in a broken and fallen world. How we are to preach the good news to the poor, heal the sick (without making false claims about it), cast out demons etc.

And one of the demons to be cast out is Mammon, and the spirit of Mammonism.

The missionaries, evangelists, prophets and proselytisers of Mammon have been going out into all the world from the West, making disciples of all nations and baptising them in the name of the Market, Profit, and the Spirit of Free Enterprise. One of the greatest prophets of the movement was Ayn Rand, whose ideas were first seen as marginal, but since the Reagan-Thatcher years have become increasingly mainstream in the West, and in other parts of the world through aggressive Western proselytism.

What is a "brand"?

Well, in the old days, it was a distinctive label for a commercial product, so that you could see who manufactured and sold it. KFC is both a brand and a franchise. A franchise, in the commercial sense, being a brand that is licensed to independent retailers with an agreement that they will sell products with that particular brand, and under certain special conditions.

Well, in the old days, it was a distinctive label for a commercial product, so that you could see who manufactured and sold it. KFC is both a brand and a franchise. A franchise, in the commercial sense, being a brand that is licensed to independent retailers with an agreement that they will sell products with that particular brand, and under certain special conditions.

Fast-food outlets are among the best-known franchises, but they are also found among car dealers and garages, which have a franchise to sell a particular make of vehicle or a particular brand of petrol. When I was young garages usually sold all brands, especially in the bigger towns. It was only one-pump country stores that sold only one brand of petrol. But now they are mostly franchises. If they are owned by the oil company, of course, they are not franchises, but wholly-owned subsidiaries.

Fast-food outlets are among the best-known franchises, but they are also found among car dealers and garages, which have a franchise to sell a particular make of vehicle or a particular brand of petrol. When I was young garages usually sold all brands, especially in the bigger towns. It was only one-pump country stores that sold only one brand of petrol. But now they are mostly franchises. If they are owned by the oil company, of course, they are not franchises, but wholly-owned subsidiaries.

When confined to such uses, terms like "brand" and "franchise" are meaningful and useful.

People talk about "separation between church and state", but no one seems to talk about separation between business and state. Oh yes, in the heady days of the mid 1990s, when democracy was a novelty and we all got excited about it, there were idealistic laws saying that members of parliament should disclose their commercial interests, and gifts that they had received, but now many of them have come to resent it, and even the State President himself, sworn to uphold the constitution, resists it.

And so commercial language and values take over everything, from sports teams to ecclesiology. And when respected religious journalists and media watchdogs start talking about "the Anglican brand" and "the Anglican franchise" we can know that we have a fully-fledged capitalist ecclesiology. Our mental furniture has been rearranged according to a Mammonist model, and our language shows it. As an Afrikaans proverb puts it, "Wat die hart van vol is, loop die mond van oor" ("What fills the heart overflows from the mouth").

And when that happens, perhaps we need to heed St Paul's words:

Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that you may prove what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect (Rom 12:2).

February 13, 2012

Tales from Dystopia X: The banality of evil

The phrase "the banality of evil" became prominent with the publication of Hannah Arendt's book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, on the trial of Adolph Eichmann in Jerusalem. Eichman, an administrator in the bureaucracy of Nazi death camps, thought that he was simply doing his job. The phrase "the banality of evil" describes the thesis that the great evils in history generally, and the Holocaust in particular, were not executed by fanatics or sociopaths, but rather by ordinary people who accepted the premises of their state and therefore participated with the view that their actions were normal.

But to me the concept behind the phrase is perhaps best illustrated by a passage from C.S. Lewis's novel Perelandra where the protagonist, Ransom, is watching the activities of a mad scientist, Weston, in trying to spoil a world as yet uncorrupted by evil. Weston engages in acts of wanton cruelty and destruction, torturing small animals, and then calls Ransom's name endlessly, and when Ransom replies, Weston says, "Nothing."

[Ransom] taught imself to keep silent in the end; not that the torture of resisting his impulse to speak was less than the torture of response but because something with him rose up to combat the the tormentor's assurance that he would yield in the end. If the attack had been of some more violent kind it might have been easier to resist. What chilled and almost cowed him was the union of malice with something nearly childish. For temptation, for blasphemy, for a whole battery of horrors, he was in some sort prepared, but hardly for this petty indefatigable nagging as of a nasty little boy at a preparatory school. Indeed no imagined horror could have surpassed the sense which grew within him as the slow hours passed, that this creature was, by all human standards, inside out — its heart on the surface and its shallowness at the heart. On the surface, great designs and an antagonism to Heaven which involved the fate of worlds: but deep within, when every veil had been pierced, was there, after all, nothing but a black puerility, an aimless empty spitefulness content to sate itself with the tiniest cruelties, as love does not disdain the smallest kindness?

Today is the fifth anniversary of this blog, which I started on 13 February 2007, when it seemed that Blogger was broken and would never be fixed. I thought I should write something to mark the occasion, and had just been writing elsewhere about events of 40 years ago, thought I would post them here too. "Elsewhere" is a mailing list where I communicate with people I worked with in the Anglican Church in Namibia, and have been posting extracts from my diary. And I think that those extracts from my diary can illustrate something of the banality of evil.

Extracts from diary of Stephen Hayes

These deal at some length with ministry to Anglicans in the Ovitoto Reserve in Namibia (then known as South West Africa) , and the lengths that government officials went to to try to prevent such ministry.

Friday 11 Feb 1972

Magdalena Bahuurua phoned up, and said her auntie had died, so I went out to see her, and arranged to go to Ovitoto to conduct the funeral. I took Lisa to the Alhambra to see "Bedknobs and broomsticks", which was rather fun, though not a brilliant movie.[1]

Notes and hindsight

Aletta Tooromba lived in Ovitoto Reserve, about 90 miles from Windhoek via Ohahandja by road, though considerably closer as the crow flies. For the previous year, once I had got a reliable vehicle, I had been going there to take her communion, and the other Anglican members of the family also joined in the services. Because the Anglicans had neglected then (the last priest who had gone there was Fr Ron Gestwicki, who had been deported s couple of years before) many of the family members had joined other denominations, like the St John Apostolic Faith Church and the St Philip Apostolic Faith Church.

Security Police report to Secretary of Justice dated 17 Dec 1971:

Twice this year he entered the Ovitoto Reserve without a permit, though he was fully aware that he needed a permit.His application for a permit was repeatedly rejected. This open provocation of HAYES put the Department of Bantu Administration and Development in great difficulty especially after the Attorney-General of S.W.A refused to institute a prosecution after his first offence. During the student riots in the north of S.W.A. there were regular reports of HAYES involvement in the organisation and development of events.

In an earlier, but much longer memorandum (28 pages), item 117 reads as

follows:

21/6/1971: Hayes let Aitchison know that he was forbidden by the superintendent of the Ovitoto Reserve to enter the reserve. On 5/6/1971 he actually entered the reserve without a permit, and afterwards let the magistrate know by letter what he had done. The Attorney General later refused any prosecution, saying that Hayes was busy with provocation, and that the case was doubtful.

What actually happened was that Magdalena Bahuurua, the leader of the Herero Anglicans, who had formerly been Bishop Mize's housekeeper, kept nagging me to take communion to her aunt, Aletta Tooromba, who was old and sickly and lived in Ovitoto.

I asked about this among the clergy of the diocese, and someone, I think George Pierce, advised me to write to the magistrate at Okahandja at ask for a permit. I did so, but heard nothing. Later I wrote a second letter, or perhaps the bishop wrote a second letter, but again there was no response, apart from a letter asking for proof that I was a minister, which was duly sent.

Magdalena, who was concerned that her aunt would die without receiving communion, kept urging me to go, so on one Saturday, having recently bought a new Daihatsu double-cab bakkie (which I named Strawberry, after the flying horse in C.S. Lewis's The magicians nephew), I went. Here is my diary entry relating to that:

Saturday 16 January 1971

I celebrated Mass at the Cathedral in the morning, and then went to pick up Magdalena to go to the Ovitoto Reserve. She was not at home, so I went to Magdalena Kaune's house, and she said they were only expecting to go tomorrow. I went to fetch Hiskia [2], and asked if he would like to come and interpret for me. He seemed quite pleased to come. By the time we had collected everyone and set off it was nearly 11:00 and we had ten people in all loaded in to Strawberry – seven in the cab and three on the back.

At Okahandja we turned off on to the Steinhausen road, and after going east for about twenty miles turned off into Ovitoto itself – and from there it was only a two wheel track, going over sand sometimes, and over rocks and bumps. Strawberry didn't seem to mind at all. Ovitoto itself was quite beautiful. Some parts were bare and overgrazed, but everywhere there were green trees, and in some places green grass and yellow flowers. At one place Magdalena said everyone must get off, and I must cross the river, and pay my respects to the Superintendent of the Ovitoto Reserve, Mr Pretorius. So I drove down the muddy river bank, crossed a sand bank, and went to his house on the other side, only to find that he was not in.

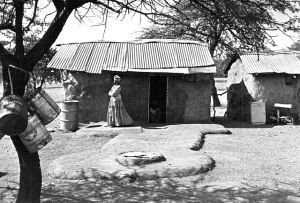

Aletta Tooromba's house at Oruua, Ovitoto, Namibia

We continued on our way, stopping at the store a little further on for a drink of water. The road got worse and worse, and we drove about fifteen miles over the hills and across riverbeds, with Madalena encouragingly pointing out the places where Fr Gestwicki had got stuck in the Landrover – but Strawberry never faltered. Finally we arrived at Oruuua. We first went to see Magdalena's family – her mother and sisters, and her sister's son, Mateus, of the Oruuano Church, to whom her father had left the care of the congregation there.

We then went down to her aunt's place, a couple of hundred metres away, and there was the house where we were to hold the service, empty but for a couple of chairs and a table, and Madalena's aunt, Aletta Tooromba, who could hardly walk. The floor had been newly plastered with cowdung, and there was a crucifix hanging on one wall. I arranged for Hiskia to read the Epistle, and Mateus to choose the hymns. I celebrated the Mass westward facing, in Herero, and Hiskia translated the sermon. It was about the best service I have ever been to in South West, because the congregation participated fully. There was no hesitation about the responses and they said practically all the service except the absolution and the canon. At the end we sang some of the Oruuano Church hymns, with clapping, and Magdalena walked out in disgust, but the rest of them all laughed at her, and in the end she came back laughing too. We then sang "Nkosi silelel' iAfrika" in Zulu and Herero, and the congregation said they liked it.

We went back up to Magdalena's mother's place, and Hiskia and I drank omaere with Mateus and talked, and we left about half an hour later. The journey back to Windhoek was much the same as on the way out, except that we went into to Okahandja, and visited some of the Anglicans there, and I arranged with Margriet Jaantjies to have a service there next Sunday.

_____

The next time I tried to visit Ovitoto was on 27 March 1971 – diary entry

follows:

Aletta Tooromba

I fetched Magdalena Bahuurua, Magdalena Kaune and other Herero Anglicans from Katutura and we then went to Ovitoto. On the way we crossed the Swakop River, which was flooding in quite a rush on one side, and we had to go down a steep bank to splash through it. Then we passed fields full of purple flowers. When we reached the superintendent's office, I went to see him, but he said he could not let me in without a permit. I explained to him that I had applied for one at the magistrate at Okahandja, and they had only asked for proof that I was a minister. He insisted that I needed a permit, so I went over to his office and wrote another application, and asked him to see that it was sent in. Then I collected the people who had waited at the other side of the river, and we went back to Okahandja. Magdalena Kaune was mad as a snake, and so were they all, because we had loaded up with great bags of mealie meal to give to her mother in Ovitoto.

We got back to Windhoek in the afternoon and Fr Frank phoned to say that Dick had left a message for him to ask him to tell us that Jenny Aitchison had phoned. It sounded bad, and we thought John might have been banned again.[3] We tried to phone the Smalls but got no reply, and later when we did tried to phone the Smalls but got no reply, and later when we did get through they said they had not seen the Aitchisons at all. We then tried the Richmonds, and spoke to Rose and John and Jenny were there, so we spoke to them. John said he had indeed been banned again, but he was not discouraged. He said the banning order was very similar to the last one, with a couple of new things added, such as not being allowed to write political letters. The government begins to seem the face of Satan incarnate, scattering the saints and making war on them.

(end of diary entry)

On the way back from the aborted trip to Ovitoto we sang a Herero chorus that seemed appropriate to the occasion:

Satana pita mondjira, matu tjaere okukumba

Matu hungire na Jsus, mukuru wokombanda

(Satan get out of the road, he tries to keep us from praying

we pray to Jesus, the God of the heavenly hosts.)

Satan had certainly tried, through his agent Mr Pretorius, to keep us from praying with old Aletta Tooromba.

I had also noted the Administrator's Proclamation which, according to Mr Pretorius, said that a permit was required to enter Ovitoto, and back in the Advertiser office on Monday (I worked as a proofreader with the local newspaper, the Windhoek Advertiser), where they had a copy of the Laws of South West Africa, I looked up the section that Mr Pretorius had referred to, and it said nothing whatever about needing a permit to enter the reserve. A permit was only needed if someone who was not already a resident wanted to "encamp or reside" there.

I concluded that Mr Pretorius was exceeding his authority in demanding a permit.

The next time I went was the visit recorded in the SB report above:

Saturday 5 Jun 1971

I woke at 7:15, and fetched Magdalena Bahuurua, and drove out to Ovitoto. We passed the superintendent's office without incident, so I suppose he didn't notice us. We drove on to Oruua. Magdalena's brother was there, and several big shots from the St Philip Church, so most of those who attended our service were children, about 25 altogether, with four communicants. Everyone seemed busy afterwards, so we left almost immediately, but at least Aletta Tooromba had received communion.

Oruua, Ovitoto, Namibia

We called in at Okahandja location to tell Margriet Jaantjies that the service would be late tomorrow, because I will be celebrating at the 9:30 Mass at the Cathedral. Margriet was out, however. I was half asleep driving back to Windhoek, and got back at 4:30. I went to the Diocesan Office and wrote a letter to the magistrate at Okahandja telling him I had been to Ovitoto without a permit. That way they can not accuse us of being underhand and subversive. Roger Ellick, the Methodist minister from Khomasdal, came in and had a look at the drawings of the new cathedral centre, and also arranged to come with me to Gobabis the next time I go there. Then I went to see Penny Whitford to arrange the hymns for the service tomorrow, and went home and went to bed early.

_______________

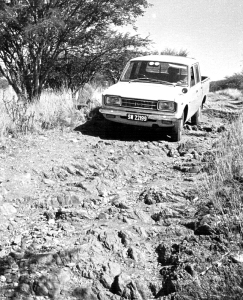

Returning from Oruua in the Ovitoto Reserve

Writing the letter to the magistrate at Okahandja was, I suppose, "provocation" of a kind. I wanted to provoke them into prosecuting me for entering Ovitoto without a permit, because I thought I had a rock-solid defence — that the law that they said demanded a permit demanded no such thing, and that no permit was needed to enter Ovitoto and return the same day. I thought that the waste of taxpayers money in all these bureaucratic machinations in a conspiracy to stop one sick old lady from receiving communion needed to be exposed. And also that government officials, like the reserve superintendent and the magistrate, were exceeding their authority.

The Attorney General had declined to prosecute, it is clear, because he knew the law, and knew that a prosecution would never succeed. The way the SB reports are worded suggests that they were dropping hints to the Minister of Justice that the Attorney General was politically unreliable, and that he needed to be replaced by a more compliant one. I wonder if he was transferred as a result.

One interesting part of the SB reports quoted above has nothing to do with Ovitoto:

"During the student riots (onluste) in the north of S.W.A. there were regular reports of HAYES involvement in the organisation and development of events."

I wonder where those "regular reports" emanated from, or if it was just something that the SB had sucked out of their thumbs.

The only thing I had done was to phone Toni Halberstadt (who was then teaching at the Anglican school in Odibo) to ask for news about the boycott of the opening of the recently-nationalised Ongwediva College, which Clive Cowley, the editor of the Windhoek Advertiser, was eager to publish, since he had been refused a permit to attend that event, which he had been informed of beforehand by a gloating Kurt Dahlmann, the editor of the sister paper, the Allgemeine Zeitung.

So there was this huge bureaucratic tizz, which involved correspondence and memos going back and forth between the Reserve Superintendent of Ovitoto, the Magistrate at Okahandja, the Department of Bantu Administration and Development in Windhoek (and probably Pretoria as well), the Security Police in Windhoek and Pretoria, the Commissioner of Police (KOMPOL — a nice Soviet-style acronym) in Pretoria, and the Secretary and Minister of Justice, all at the taxpayers' expense. And all of it aimed at stopping one sick old lady from receiving Holy Communion before she died.

It was altogether banal. And altogether evil.

Notes and references

[1] There is a description of the funeral of Aletta Tooromba, with pictures, here.

[2] Hiskia Uanivi was then a student at the Lutheran Seminary at Otjimbingue, and was spending part of his vacation in Windhoek.

[3] John and Jenny Aitchison lived in Pietermaritzburg. John had been a close friend when I was at university. He married my cousin Jennifer Growdon and later became Professor of Education at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. At the time of these events we produced a small Christian magazine called Ikon, which had to cease publication when all the editors were banned by the government.

Tales from Dystopia is a series of posts I am doing at irregular intervals, with memories of the apartheid era. Some of my fellow South African bloggers said that we should not forget what happened in our past, so that we can learn the lessons of history. So these posts are my contribution to that.

February 9, 2012

Popular culture, celebs and values

It seems, according to blogger Clarissa, that the time has come for me to be carted off to the dung-heap of existence, because I am out of sympathy with the values and aspirations of today's youth. As she puts it Tweens and Values | Clarissa's Blog:

I always say that the moment you experience the need to dump on the younger generation, you need to know: this is the day when you have become hopelessly, irredeemably old. If you feel like harping on the horrible values of today's kids and keep comparing them to how much better your values were when you were their age, congratulations! You are now completely ready to be carted of to the dungheap of existence. It doesn't matter how old you really are. A visceral dislike of younger people makes you old even if you are 25.

What are these values that I am so out of sympathy with?

According to a source quoted by a source quoted by blogger Clarissa, Being a celebrity is the 'best thing in the world' say children | Mail Online:

Children under 10 think being a celebrity is the "very best thing in the world" but do not think quite as much of God, a survey has revealed.

The poll of just under 1,500 youngsters ranked "God" as their tenth favourite thing in the world, with celebrity, "good looks" and being rich at one, two and three respectively.

To quote Clarissa once again, at some length, Tweens and Values | Clarissa's Blog

What are the values that the author of this piece classifies as good and which ones does he see as negative? The "good" values are Community Feeling, Benevolence, Image, Tradition, Spiritualism, Security, Conformity, and Popularity (these capital letters make me think of the precious writing style of XIXth century damsels locked up in boarding schools who capitalized words like Love, Friendship, and Betrayal in letters to their imaginary lovers. Bleh.) The "bad" or "unhealthy" values are Ambition, Comparison to Others, Attention Seeking, Conceitedness, Glamour, Fame, Physical Fitness, Hedonism, Financial Success, and Materialism.

Now, a question for everybody. What is the main difference between these two groups of values? To me, the answer is obvious. The good values are the ones that are likely to be experienced by people who live to serve their group. People who privilege such values are usually most comfortable in heavily patriarchal societies where an individual's interests don't matter a whole lot because the individual belongs to his or her group (family, clan, community.)

The bad values, however, are the ones that characterize modernized societies where an individual pursues his or her own interests and does not abdicate them in order to belong. Where the first group of values insists on conformity, the second one praises comparison to others, uniqueness, personal ambition. When you stop being a slave to tradition, you can concentrate on looking for your own ways to enjoy life (hedonism), take care of your body, and be successful.

If there had, indeed, been a shift in values that is described in the post I quoted and this shift occurred along the lines of moving away from communitarian, patriarchal values to more individualistic and personal ones, then that is great news, indeed. And if you disagree with me that such shift is a positive phenomenon, ask yourself how ready you are to have your parents decide what profession you choose, whom you marry, when and if you have children, etc.

I've quoted it at some length because at this point I disagree profoundly with Clarissa, but I don't think my disagreement has anything to do with dumping on the young.

To explain why I think this should be so, however, I have to go back to my own youth, though not as far as when I was 9 or 10. At that age we had no TV, no radio, and the peer pressure was all from school bullies and my main ambition in life was to escape their attention, and perhaps to be a pilot flying aeroplanes to remote places like my hero Biggles.

Ten years later, however, when I was 17-19, I read four books that influenced my approach to these values:

The organization man, by William H. Whyte

The hidden persuaders, by Vance Packard

Brave new world, by Aldous Huxley

1984, by George Orwell

The first two books both quote a third book (which I have not read), called The lonely crowd, which describes three kinds of people: tradition-directed, inner-directed and other-directed. Tradition-directed people largely belong to pre-modern societies, but in modern societies one finds both inner-directed and other-directed people. Tradition-directed people base their lives and values on those inherited from a time before they were born. Inner-directed people develop and set their own goals in life, and internalise their values, from whatever source they may be derived. Other-directed people take their direction from other people — their peer group, people they admire, people they want to please, and so on.

All four books of the books listed deal with other-directed societies, and see dangers in them. The organization man deals with big business, especially in America, and the way in which firms demand conformity in their employees. Whyte sees this as a danger that would stifle original thinking. The hidden persuaders deals with the advertising industry, and how advertisers seek to control people and make them behave in ways desirable for their clients. Both were written just over 50 years ago.

The other two books are older, and are works of fiction. They envisage other-directed societies in which people are controlled by the state, though in different ways. In both, however, there is a "director". In Brave new world there is a benevolent dictator, Mustapha Mond, who says that people are happier when they live controlled, predictable other-directed lives. In 1984 there is a malevolent dictator, Big Brother, who rules by fear. In both books there is a protagonist who is inner-directed or tradition-directed, who rebels against the system.

During the same period I took a sociology course at university, which was heavily based on the functionalist model of sociology, and the underlying assumption was that man was made for society, and not society for man. I once asked one of the sociology professors, G.K. Engelbrecht, who was speaking about how the church could help youth to adjust to society, what would happen if society was wrong, and youth could see that the emperor had no clothes. His response was a very emphatic "Youth must adjust!" and I almost expected his right arm to jerk up, Strangelove fashion, in a Hitler salute.

Now it seems to me that blogger Clarissa is saying, in the piece I quoted above, that values such as Ambition, Comparison to Others, Attention Seeking, Conceitedness, Glamour, Fame, Physical Fitness, Hedonism, Financial Success, and Materialism are not bad, but good, and that they are good because they are inner-directed. And I disagree on both counts.

First, I disagree that they are good. I won't go into that here, but I wrote about it recently as part of a Synchroblog on Extreme Economic Inequality. And the values she mentions are not, in my view, signs of being inner-directed, but are rather carefully inculcated by the hidden persuaders.

She writes of children watching TV shows, as if these reflected the values of children, but I doubt that that is so. They reflect the values that adults wish to inculcate in children, in order to make them obedient subjects of the consumer society. Millions of children can't all be celebs when they grow up, but they provide a wonderful marketing opportunity for people who sell celeb-related merchandise, and the hidden persuaders who create the demand for them.

I can never forget the day I bought my first pair of Levis.

It was on 8 January 1963 and I bought them at Haldon's in Jeppestown, Johannesburg, the only shop in South Africa that sold them. Jeppestown was a run-down slum then, and it probably still is today, unless it has been gentrified, which I very much doubt. It was an old-fashioned outfitters, with glass counters and wooden drawers with things like detachable collar studs. They never advertised, and certainly didn't advertise that they sold Levis. One learnt that by word of mouth.

The Levis were in a pile, flat, stiff as boards. The shop assistant told me to buy a pair two sizes too big ("They shrink, you know.")

They were rough and tough and real working jeans, and lasted for ages and ages and ages. They shrunk to fit and faded over the years.

They were the kind of thing the hidden persuaders hated. As Packard (1960:140) put it:

One ambitious and significant effort to tamper with out living pattern was a multimillion dollar campaign by the men's clothing industry to make men pay more attention to stylishness in their clothing. It seems that men were much too easily satisfied when it came to clothing. They wore suits for years upon years. Men's clothing sales stood still while other lines of enterprise were forging ahead. Several years ago the executive director of the National Fashion Previews of Men's Apparel Inc., diagnosed the trouble. 'The business suffers from a lack of obsolescence.'

And so they made Levis what they are today, and advertise them silly in an effort to get kids to desire them and despise those who wear other brands. So who's other-directed now?

I wouldn't be seen dead in a pair of Levis today.

Does that mean I'm dumping on kids and their values?

No, because back in the 50s and 60s some kids were inner-directed and some were other-directed, just as they are today. Some were dedicated followers of fashion, while some bucked the trend, just as they do today.

And, according to that survey, what do kids today think is bad? Being a celebrity is the 'best thing in the world' say children | Mail Online:

Meanwhile "killing" and "wars" head the list of the "very worst things in the world", followed by drunks, bullies, illness, smoking, stealing, divorce and being fat. Dying is in tenth place.

The research, carried out through schools and online, was by Luton First, sponsors and organisers of yesterday's National Kids' Day.

Asked what rules they would make if they were king or queen of the world, the number one response from the under-10s was to ban knives and guns. They would also put a stop to fighting and killing, telling lies, drugs, bullying, drunks, and smoking.

I'm cool with that.

If you really want to know my thoughts on the younger generation and their values, you can read about them here: The youth of today, and yesterday | Khanya.

February 7, 2012

Death comes to Pemberley – book review

Death Comes to Pemberley by P.D. James

Death Comes to Pemberley by P.D. James

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

P.D. James is known mainly as a writer of detective and other crime stories, though she has occasionally ventured into other genres like fantasy. In this book, however, she combines her main genre, crime fiction, with two others — the historical novel and fan fiction, or fanfic for short.

It is not often that established writers venture into the field of fan fiction, in which people write their own stories about the characters and settings created by other authors. In this case the author is Jane Austen and the characters are taken from her novel Pride and prejudice.

I thought I'd better re-read Pride and prejudice before reading this one, since this is a sequel and I'm glad I did so (reviewed in my previous post). P.D. James manages to keep the characters fairly faithful to Jane Austen's originals. The setting is reproduced faithfully too. The plot is believable as a follow-on to Pride and prejudice so one of the purposes of fan fiction is fulfilled — it enables readers to read more about characters they like and to follow their adventures.

What is missing, however, is the style and wit of Jane Austen. In contrast to Pride and prejudice, Death comes to Pemberley is a bit pedestrian. It's even a bit pedestrian compared with P.D. James's other novels. And perhaps that is why fan fiction rarely gets published; it seems easy, but it is actually more demanding if it is to be satisfying for anyone other than the person who wrote it. There seem to be several anachronisms, especially in vocabulary. I doubt that Jane Austen would ever have used the word "lifestyle", for example. I don't think the word even existed in her time.

So it is pleasant reading, and faithful to characters and setting, but no substitute for the real thing.

February 1, 2012

Pride, prejudice, and youth

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

My wife Val got Death comes to Pemberley by P.D. James as a Christmas present, and passed it on to me to read once she had finished it. It claims so be a sequel to Pride and prejudice, so I thought I'd better re-read the latter, since I had last read it about 50 years ago, before reading the new one.

Some books are disappointing when one re-reads them after a long time; they never seem to be as good as one remembered. But Pride and prejudice was far better than I had remembered it, and I found I had to add a couple of stars to its rating. Yesterday I had a number of things I needed to do, and I found that I never got them done, I had to go back to reading this book until I had finished it. It was a page-turner, as they like to say in the blurbs.

It's been around a long time, so I won't say much about the characters and the plot, assuming that most people have read it, and if you haven't, well, it's still selling 200 years after it was first published, so you shouldn't find it too hard to get a copy.

One of the things that did strike me the second time round was the characters. The main characters are extraordinarily well-drawn. I can't really remember what I thought the first time, but this is what struck me the second time.

So if I don't write about the plot and characters, what can I say about what I think of the book?

I can perhaps try to work out why I liked it so much more the second time than the first time.

And I think the reason is, well, pride and prejudice.

Pride and prejudice on my part, that is.

At the beginning of 1963 I went to study at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg (UNP), and one of the compulsory courses was English I. I had previously attended the University of the Witwatersrand and had already taken English I, twice. So I was a bit resentful about having to take it a third time. Couldn't they just give me a credit for it and let me study something more interesting? It was pride, you see.

The prejudice was a bit more complex.

At school I had read Brave new world by Aldous Huxley, and had been very impressed with it. When I got to Wits University, I didn't mind reading it again. It was, I thought, a Good Book. Another, which I had first encountered at the university was William Golding's Lord of the flies. It also struck me as being a very good book. Both had (then) been published within the last 25-30 years.

When I got to the Uuniversity of Natal, the books they gave us to read for English I were all so old. Joseph Conrad was relatively recent, but the others were by Jane Austen and people like that. In one tutorial I ventured to ask about it, and the lecturer, Christina van Heyningen told me that Jane Austen's books were timeless classics, and that people would still be reading them in 100 or 200 years time, long after Huxley and Golding had been forgotten. I was not inclined to believe her. My pride would not let me.

I also soon discovered that the English Department at UNP were, on the whole, great fans of F.R. Leavis, the Cambridge University critic, who narrowed down English literature, or at least novels, to authors like Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Joseph Conrad and D.H. Lawrence, dismissing the rest as inferior. One English Honours student once asked the professor whether he should read Ulysses and was advised not to, as it would "blunt your critical faculties".

Some of us studetns tended to rebel against this, and republished in a student magazine, the Anglican Witness a satire of their attitude, with a Leavis-style review of Winnie the Pooh, with the title "Another book to cross off your list", saying that now he had got down to D.H. Lawrence alone, not even Austen, Dickens and Conrad were worth reading. So we saw the English Department as prejudiced, and so I became prejudiced against any books they recommended.

The values of the characters in Jane Austen's novels also seemed screwed up to me. The characters, heroes and villains alike, all seemed to put a money value on everything, including love and marriage, and to assume that that was right and natural. Falling in love seemed to be very much governed by the fortune possessed by, or at least due to, the potential beloved. And everything else seemed to be governed by their artificial rules of politeness. It was an utterly alien culture, and difficult to enter into.

So there was pride, and prejudice, and youth. The first time I read it, I was the same age as the protagonists in the story. I despised them for their narrow sheltered English country gentry lives. What could they know about human relationships when they moved in such a stiflingly narrow social circle, and were so obsessed by social climbing?

On rereading it, I am fifty years older, and not a callow youth any more. I can see things in Jane Austen's writing I was blind to before. Her characters do indeed move within a narrow social circle, but for Jane Austen that makes it possible to pay less attention to the setting, and rather more to the relationships of people within it. The gentle satire that whooshed over my head the first time struck me forcibly this time. And the characters seemed sensitive to nuances of human behaviour that completely passed me by the first time.

Fifty years later I have had much more experience of different cultures, and learnt, to some extent, to adapt to different cultural worlds. and that perhaps makes it easier to adapt to the cultural world that Jane Austen's characters inhabit.

But I return to my first prejudice.

Can any English I student appreciate Jane Austen? Are they not too young, and too inexperienced to appreaciate her books? Is it not better to read works like Brave new world and Lord of the flies, and save Jane Austen for those who are old enough to appreciate her? Isn't youth wasted on the young?

And when I reread Brave new world after 40 years or so, I was disappointed. It wasn't nearly as good as I had found it at 16. Christina van Heyningen was right. Austen improved with the passing of time; the other books palled.