Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 71

May 1, 2012

May Day odds and sods

In the intervals in which the Internet was working I managed to pick up a few snippets from Facebook, Twitter and elsewhere, which seem worth recording in a more findable form.

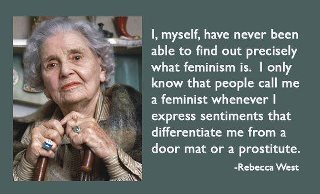

Someone posted this saying of Rebecca West on Facebook. and Pat McKenzie, former national secretary of the Liberal Party of South Africa, commented:

Someone posted this saying of Rebecca West on Facebook. and Pat McKenzie, former national secretary of the Liberal Party of South Africa, commented:

In I think 1961 Rebecca West was in South Africa writing a series on South Africa for the London Sunday Times. I drove her to Stanger to meet Chief Luthuli in E.V. Mohamed’s office. She was extremely friendly and was certainly no doormat and certainly had the gift of the gab. I hardly needed to open my mouth as she talked non-stop.

That, of course, was in the days when the London Sunday Times was a halfway decent newspaper, and not the disreputable rabid right-wing rag it is today.

Canon Eric James at Anglican Students Federation conference, Modderpport, July 1965

And then on Twitter I saw a retweeted announcement of the death of Eric James. The internet connection was too erratic and unreliable to confirm if it was the Eric James I knew, but if it is, there’s a picture of him.

I met him at the Anglican Students Federation annual conference held at Modderpport in July 1965, which he spoke on small groups in the church — house churches and similar small groups.

Six months later I scarpered to England with the SB after me, leaving at 6 hours notice. There was no time to make any arrangements for what I would do when I got there, and he took me in, a homeless, penniless semi-refugee, and I stayed with him for six weeks until I manage to find a job and digs of my own, so I have good reason to remember him with gratitude.

He was then general secretary of the Parish and People movement, and my one regret was that he didn’t take me with him on some of his trips as general secretary, as I thought I could have learnt something from that. But he certainly passed the Christian hospitality test. Memory eternal!

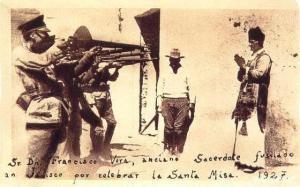

Catholic priest facing a firing squad in Mexico for saying Mass in public, 1932

And then someone posted this picture on Facebook.

It shows a Catholic priest facing a firin g squad for saying Mass in public in Mexico, in 1932.

Many years ago (about the same time that I met Eric James, I read Graham Greene’s novel The power and the glory, which was set in that period, and the protagonist is a rather pathetic little whiskey priest, on the run from the police, who is eventually caught, and faces the same fate. And on the night before his execution he realises that there is only one thing in this world that is at all important — to be a saint.

And that reminds me of something that Soren Kierkegaard said: “Onl;y one thing can be remembered eternally: to have suffered for the truth.”

And on the tomb of St Alphege (whose feast day was a few days ago) is the inscription, “He who dies for truth and justice dies for Christ.”

The man from Beijing by Henning Mankell (book review)

The Man from Beijing by Henning Mankell

The Man from Beijing by Henning Mankell

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

When I read the first couple of hundred pages or so, I was thinking that this was Henning Mankell’s best book ever. Judge Birgitta Roslin is on sick leave, and visits a village in the north of Sweden where a horifying mass murder has recently taken place, because her mother’s foster parents had lived there. She discovers that they had been killed, and also discovers some clues to the killer that the local police seem to be ignoring. The trail leads to China, which she visits with a friend.

Mankell reveals to the reader, though not to the protagonist, that the crime has political implications, and is linked to power struggles in the Chinese Communist Party.

While reading, I realised how little I know about China now. Like the protagonist, Judge Birgitta Roslin, I was quite interested in China in the 1960s. My interest was sparked by reading a book by Felix Greene, The wall has two sides, and one of the things that caught and held my interest was the mention of the fact that there were trolley buses I had a thing about trolley buses back then, and still interested in them even today, though there are now none left in South Africa.

When I was in England in 1966-68 there were bookshops in Tottenham Court Road, one called Colletts in particular, that sold magazines with pictures of China, and during the Great Cultural Revolution I acquired a copy of the “Little Red Book” of the thoughts of Chairman Mao, with cheap plastic cover, and read about paper tigers and bean curd tigers, and wondered what bean curds were. I didn’t go as far as Birgitta Roslin in ideentifiying with the Red Guards, but nevertheless rather liked the idea of fat-cat bureauscrats who had betrayed the revolution being sent to be re-educated by working among the peasants. Since I’m writing this on May Day, it seems an appropriate sentiment. I even made a couple of attempts to do things like that myself, with some other city friends.

[picture to go here when Firefox can find khanya.wordpress.com for long enough to post it]

When I returned to South Africa in 1968, that annus mirabilis of student power, I somewhat sadly left my copy of the “Little Red Book”, and a book on guerrilla warfare by Che Guevara, with a college friend, Alan Cox. It would have been crazy to bring them back to South Africa, as I fully expected my luggage to be searched on my return, though it wasn’t, and it would also not have been a good idea to have the SB find them in a raid, though they never raided me. The SB visited to take away my passport, and later to give me a banning order, but did not search the house, so I could have brought them back and kept them with impunity. Alan Cox was murdered in Pakistan a few years ago, so I’ll never discover what happened to my books.

I was still interested in China when I visited Hong Kong in 1985, taking a long bus ride and a long walk through paddy fields to climb a small hill from where one could look out over China, and see Guangdong, which is mentioned in Mankell’s book with its older transliteration of Canton. But after that, and especially after the Tianamnen Square massacre in 1989, I somehow lost interest.

Nineteen eighty-nine was another annus mirabilis, with freedom breaking out all over, and in many countries liberal ideals were beginning to be realised. In China, however, the liberalism extended only to economic liberalism, and any manifestations of political liberalism were brutally crushed. And so I lost interest in China. And I realised, reading Mankell’s book, that I would not be able to name the president of the most populous nation on earth, and still know nothing about him or his career.

I was interested in Mao, and somewhat less in Chou, and the Gang of Four I remember, but now I find China slightly distasteful — communist moralising combined with capitalist greed, even worse than Russia, where at least they have abandoned the pretence. But padding out pet food with melamine to enhance the protein levels seemed to me the most unscrupulous capitalist trick of all, and made me lose all interest in Chinese trade, Chinese goods, or even China itself.

Henning Mankel brings this struggle out in his book. It is part of the background to the story, yes, but at some points I think the story gets overwhelmed by Mankell’s didacticism. But then I suppose that I am not alone among his readers in being largely unaware of what has been happening in China in the last 25 years, and needing to be brought up to speed in order to follow the plot.

The plot also involves Chinese neo-colonialism in Africa, and at one point it seems to me that Mankell might be using his novel to make propaganda for Robert Mugabe’s regime in Zimbabwe. Of course it is always risky to assume that the views expressed by a character in a novel reflect the views of the author, but coming after the rather heavy didacticism of the preceding pages, I rather suspect that this does reflect Mankell’s view.

And I half agree with him. The Western condemnation of Zimbabwe by the likes of George Bush II and Tony Blair was indeed cynical and hypocritical. Mugabe liked to blame all his (and Zimbabwe’s) troubles on them, and on the sanctions that the Western powers imposed, and it seems that Mankell tends to agree.

But Mankell tells only half the story. Western sanctions were imposed after Zimbabwe’s economy crashed, and there was nothing that the Western powers could do to damage it more than the Mugabe regime had already done. Mankell also fails to point out that most of the opposition to the Mugabe regime came from the trade unions, a fact that Mugabe’s bombastic rhetoric about Western imperialism is caclulated to obscure, though it is recognised by Cosatu (the Congress of South African Trade Unions), a delegation from which was refused entrance into Zimbabwe. I might not have gone into all this detail in reviewing Mankell’s book, but since I’m writing this on May Day, it seemed worth doing.

If the book had fulfilled the promise it showed in the beginning, I might have given it five stars, but it has several serious flaws. One, as I have pointed out above, is its didacticism verging on propaganda for an oppressive regime. Another is that there are some serious unexplained plot holes.

In a whodunit, a murder mystery, one does not necessarily expect all the loose ends to be tied up, all questions answered, and the detectives to have all the answers in the end. But when some of the mysteries in the case are never solved, one at least expects the author to say so at the end. If the author does not mention them at the end, then one suspects that the author himself is unaware of the inconsistencies in the story.

I can’t be specific about the biggest plot hole, because that would give away too much of the plot and spoil it for the reader, so I leave it as an exercise for the reader to find out.

April 28, 2012

Anton Chekhov, short story author (book review)

Chekhov: The Hidden Ground by Philip Callow

Chekhov: The Hidden Ground by Philip Callow

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) is known for his short stories and plays. I have not usuallly been a fan of short stories, except possibly in the science-fiction and horror genres, so I did not come across Chekhov’s works until about ten years ago.

Father Athanasius Akunda had just arrived in South Africa as a young deacon to help with mission work in the Orthodox Church. There were many people who wanted to become Orthodox, and some who might have potential to study at a seminary, but few who actually had the educational requirementss necessary for entering a seminary. So we discussed the possibility of having a bridging course, and Father Athanasius suggested that we have a kind of theology in literature course. He had himself taught English literature in high schools before he was ordained.

We wrote to various people we knew to recommend suitable reading material, which would help to improve people’s reading skills, and also help to introduce them to cultures shaped by Orthodoxy, which was quite unfamiliar to most people in South Africa. Father Thomas Hopko, of St Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in Crestwood, New York, recommended the short stories of Anton Chekhov, and in particular Bishop, Student, Nightmare, Easter Eve (On holy night), Murder, Princess, Letter, Cossack, Panikhida (Requiem), Uprooted, In Exile, On the Road, In Passion Week, Dreams.

So I took a couple of volumes of Chechov’s short stories out of the library, and was hooked.

I didn’t just read the ones that Fr Tom Hopko recommended, but I read them all.

A couple of years later we had the opportunity to put Fr Athanasius’s idea into practice, as a Catechetical School had been started in Yeoville, Johannesburg.

It was something that Father Athanasius and I had been discussing for a long time. He had taught literature in high school classes, but I had never taught such a thing. Would it work? Should we be trying it? Against all the principles of modern education, this had no specific outcomes, no specified assessment criteria. There was no hope that we could get accredited on this, but we were feeling our way. Where to?

The class was supposed to be the previous week, but that was cancelled in mourning for the death of the Pope and Patriarch and the three bishops and others with him. So the students had two weeks to read the two short texts.

The texts were The martyrdom of Polycarp and Chekhov’s short story, The bishop. We told them nothing other than that they were about two bishops, at different times and places, and both were about their deaths and the events immediately leading up to their deaths.

We had four students, for all of whom English was a second or third language. Each had a different home language from the other three. One, from Zimbabwe, spoke Shona; he had attended a Roman Catholic seminary, and was the intellectual of the group. Another was a refugee from Congo; English was his third language, his second language was French. The third, whose home language was North Sotho, really wanted to be a carpenter and was not academically inclined, but perhaps he had a poetic ear. And the fourth spoke Zulu; he was a political organiser, the leader of a youth choir, a go getter.

But the stories left the students in darkness. One said he could not penetrate the meaning. The Chekhov one took place in Holy Week, but that was about it.

So I asked them to read a few paragraphs aloud. The bishop goes home to the monastery where he lives. He is told his mother had called to see him. He is overjoyed to learn this, but it is too late to see her now. He begins to feel ill (the illness that will lead to his death (but we, the readers, and he, do not know this yet). He says his prayers, scrupulously and attentively, and at the same time thinks of his mother and his childhood, which seems happier in retrospect than it did at the time.

How does this compare with Polycarp? Polycarp too has a journey, but unlike Bishop Pyotr in Chekhov’s tale, he is on the run from the police, but eventually decides to give himself up. He too rides in a coach, but it isn’t his, but the police commissioner’s. He barks his shins as he gets down.

But there are other things too — Polycarp feeds the arresting officers, and I was reminded of Beyers Naude, who had died last week. When he was banned, the Security Police often used to watch his house, noting details of any visitors. And his wife, Tannie Ilse, would take them coffee and biscuits out to the car. As St Paul says, when your enemy is hungry, feed him. I’m supposed to be the teacher here, but I’m learning a great deal from reading these stories.

Are the students learning anything, I wonder? And, like Bishop Pyotr, my mind goes back to my youth, to English I tutorials with Christina van Heyningen and Glen Culpepper on the lawn in front of the Arts Block at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg. Did they too wonder if they were getting anything of their enthusiasm across to these rather dull students? When I was 23 I was remarkably dull and unresponsive to literature and writing. Perhaps I should have done something else, and waited till I was 63 before doing English literature classes at university. I’d certainly have appreciated them better then. As they say, youth is wasted on the young.

And then I remembered that in discussing this Father Athanasius and I did have specific outcomes in mind after all. Ambitious, unrealistic, and certainly not likely to be accepted as a Level 4 unit standard with the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). We wanted the students to write literature — in Shona, North Sotho, Zulu, and whatever language the Congolese student spoke at home. Perhaps, who knows, one of them may be the new Chekhov for that language. So we gave them an assignment: write your own story about a bishop. It can be fact or fiction, real or imaginary. How long? How many words? How many pages? As long as it takes to say what you have to say, no more and no less.

They had until the end of the semester to write them. Perhaps some might be worthy of publication. Yes, that’s an outcome. And it’s quite specific.

But the outcome was never achieved. None of the students wrote a story.

So I was glad that I had come to Chekhov’s stories at the age of 63, rather than the age of 23. I’d probably not have appreciated them at the younger age. And I learned from this biography that Chekhov was only halfway between those ages when he died. I learned that The Bishop was one of his mature stories, written at a time when he was looking forward to his own death, from TB. And I learned that it differed a great deal from the stories he wrote in his youth.

I also learned that Chekhov had largely lost his faith when he wrote most of his stories, and he said that the only thing that was left was that he loved the sound of church bells. I was reminded of Fyodor Dostoevsky‘s book The brothers Karamazov, in which there is a dog called Perezvon. which means “peal of bells”. In stories like “The bishop” one can see something of why and how the Orthodox Christian faith had so permeated Russian culture that the Bolsheviks were not able to eradicate it, even after 70 years, and I suspect that in such stories Chekhov passed on the seeds of faith, even though it was a faith he himself had lost.

April 27, 2012

Freedom Day

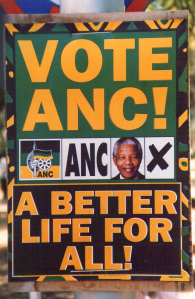

Today is Freedom Day in South Africa, and it marks 18 years since our first democratic elections, which took place over 3 days, from 27-29 April 1994, which also happened to be Holy Week.

I recall it by looking to see what I wrote in my diary at the time. It was also something that we wrote in a letter to friends and family, so it has some explanations I wouldn’t normally put in a diary entry, and it just seemed easiest to copy it into my diary as a description of the day. It was the only general election we have had where anyone could vote anywhere. There were no voters’ rolls, and non-citizens who were permanent residents were also allowed to vote. It was the most free and most inclusive election we have ever had.

Wednesday 27 April 1994

Last night at midnight we watched on TV as the old South African flag was hauled down, and the new one raised. A new era for South Africa has really begun. The country’s first democratic election actually began yesterday, with special votes being cast by people living abroad, and by the old, the infirm and invalids. There were problems in some places, mainly logistical, in getting supplies and equipment to all the right places for people to vote. Today was the first day of voting for the rest of us.

Last night at midnight we watched on TV as the old South African flag was hauled down, and the new one raised. A new era for South Africa has really begun. The country’s first democratic election actually began yesterday, with special votes being cast by people living abroad, and by the old, the infirm and invalids. There were problems in some places, mainly logistical, in getting supplies and equipment to all the right places for people to vote. Today was the first day of voting for the rest of us.

At 7:00 am we watched on TV as Nelson Mandela, the leader of the African National Congress (ANC), cast his vote in Inanda, Natal. He wanted to vote in Natal, because that is where the ANC started in 1912, and their struggle for political rights for black South Africans has therefore lasted 82 years. Inanda is also an area where there has been much political violence in recent years. There was then similar footage of Chief Gatsha Buthelezi, of the Inkatha Freedom Party, casting

his vote. Both had to move around a lot to pose for photographers wanting to record the historic moment.

Then we decided it was time to go and vote. Where? On impulse we decided to go to Mamelodi, a black township 14km away. So my wife Val and I set off, accompanied by daughter Bridget toting a camera. She won’t be old enough to vote till next year, but she wasn’t planning to miss the fun. Just before 8:00am the streets of Pretoria were absolutely dead. I’ve never seen the place so deserted. A yellow police van behind us was the only car we saw for most of the way to Mamelodi. Mamelodi had slightly more life than Pretoria. A couple of cars, and some pedestrians, but no buses or taxis. We drove through Mamelodi West, and saw no signs of activity.

Then we reached Mamelodi East, and saw some cars and people, and when we got closer, some posters from the IEC (Independent Electoral Commission). We stopped, parked next to the main road, and then walked into the grounds of a school – don’t even know what it was called. There was a policeman at the gate, and a newspaper seller. We bought some papers, and joined the end of a queue just inside the gate, that disappeared round the corner of the building. People silently filed in behind us. It was very quiet, almost solemn. The queue moved slowly, and when we reached the corner of the building, we saw it stretched right down the length of the building and to the far end of the netball field beyond. A young IEC official came to ask if everyone had identity documents of some kind – those who didn’t were directed to another school next door, where they could get temporary voter cards. He also took a look at Bridget’s T-shirt, with the slogan “Masibeke uxolo phambili” (Let us look forward to peace) on it. He decided it wasn’t party propaganda, so it was OK. Party slogans etc. were not allowed within a certain radius of polling stations.

In the queue waiting to vote; Mamelodi East 27 Apr 1994

We shuffled down the length of the building, and right round the netball field, then back to another building. There was very little talking, no pushing, no shoving, no queue jumping, no impatience. We were the only whites there.

Occasionally people would greet someone they knew. One thing that struck me was that four out of five voters seemed to be male. Maybe women were planning to vote at another time, or maybe there were more male voters than female ones in Mamelodi.

It took about 2 hours to reach the front of the queue. Our hands were checked under ultraviolet light to see that we had

not voted before. Our identity documents were checked and stamped, our hands were sprayed with invisible ink, and

we were given ballot papers to vote with. The ballot boxes already seemed to be pretty full. It looked as though they would need new ones fairly soon. As we were leaving the school grounds, some other whites walked in – the first we had seen. They were international observers monitoring the election.

First democratic elections, 27 April 1994. Voters queuing up in Mamelodi East.

We had been told of the chaos and logistical problems at some of the other 9000+ polling stations in the country, but this one in Mamelodi East was pretty slick operation. The IEC deserves to be congratulated. There was also no violence, no intimidation, no canvassing and no soliciting. There wasn’t a party worker in sight from any of the parties. As far as we could see, voting at Mamelodi was certainly free and fair. It was a solemn, somewhat awesome occasion. We had seen the future, and it works.

St Nichiolas of Japan Orthodox Church, Brixton, Johannesburg. Good Friday, 29 April 1994

When we got in the car, it was 10:00 am, and we rushed to Johannesburg 100 km away for a church service at 11:00. For Orthodox Christians this is Holy Wednesday, and in many Orthodox Churches the Holy Unction (anointing of the sick) is celebrated on this day. It is long – about 2 hours – another two hours of standing in church, praying for healing. Praying not just for healing of particular ailments, but for general healing, of ourselves, of our relationships, of our country and its wounds. It seemed entirely appropriate. And after the service there was a mingled smell of both – on the back on one’s hand was the slight lemon smell of the invisible ink from the voting, and on the palm was the smell of olive oil, the oil of healing. Kyrie eleison – Gospodi pomiliu – Lord have mercy. May the Lord indeed heal our land. Masibeke uxolo phambili – May we see peace ahead.

[End of diary entry]

The voting lasted three days, and they had been declared public holidays to give everyone a chance to vote. Our experience of 2 hours in the queue showed that that was needed.

One thing I did not mention in my diary entry was the white panic. Supermarkets had empty shelves, especially where tinned goods usually were, as people stocked up for an expected siege.

Our church, St Nicholas in Brixton, Johannesburg, was the only parish in the Archdiocese of Johannesburg and Pretoria that had the normal Holy Week Services at the normal times. Other parishes had asked the Archbishop for permission to change the times of services because they expected “trouble”. At St Nicholas we discussed the Archbishop’s letter giving permission for this, and decided that Jesus didn’t change the time of his crucifixion because he expected “trouble”. It was trouble, and that was what it was all about. So we decided to go ahead with out regularly scheduled services, no matter what. And as a result of being the only parish to have services at the normal times, we had bigger congregations at the Holy Week services than at any other time, before or since, as people from all the other parishes who thought the panic was silly came to join us.

During the last days of Holy Week there are two services a day, each lasting 2-4 hours, so we appreciated the public holidays for the elections, as the roads remained quiet, as on the first day of the elections. Just before reaching the church we passed the headquarters of the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), and they had closed half the double-carriageway to provide parking for all the foreign journalists who had come to cover the elections, and, it seems, the bloodbath that they too expected. On the third day of the elections (Good Friday) half of them had gone, off to Rwanda, where the bloodbath was really taking place. [Diary resumes]

Holy Thursday 28 April 1994

We went to church early to get the flowers ready for the epitafion and then to the Vesperal Divine Liturgy at 11:00, and afterwards stayed until 4:00 pm doing the flowers, polishing the brass, etc. Pierre van Rijswijck was there, and kept saying how sorry he felt for the Afrikaners, because they had lost everything, even more than the Germans after the Second World War – their flag, their anthem etc. I couldn’t feel sympathetic, since they had gained what the rest of us had gained as well – an inclusive flag, and a more inclusive anthem. Those who reject them are probably a minority, and their behaviour seems more like the dwarfs in C.S. Lewis’s The Last Battle, who thought they were still in a stable. They’ll refuse to go to heaven because there are no “whites only” signs there.

Easter Sunday 1 May 1994

There were a lot of people in the church for the vigil – perhaps because most of the other parishes had moved their services to later in the morning for fear of violence during the elections. Quite a lot of them stayed for the Divine Liturgy, unlike most Greeks who rush off halfway through, and many stayed for the feast afterwards.

We got home at 4:30 am and went to bed, and then I woke up at 9:30 and we watched the TV for election results, but they

kept showing stuff with a puppet they had shown before, and didn’t show very much of the actual numbers, which is what we wanted to see. From what they did show it seemed that the smaller parties did better in the provincial elections than in the national ones.

In the evening Val and I went to the Pascha Vespers, with the gospel read in many languages. It is always a very peaceful and relaxed service, and this time was no exception. We stopped for a steak roll at the Steers in Auckland Park. On Wednesday it was full of foreign journalists, but now it was very quiet.

[end of diary entry]

The ANC won the election, and after that there were preparations for the inauguration of Nelson Mandela as the first democratically elected president. Pretoria was illuminated for the occasion.

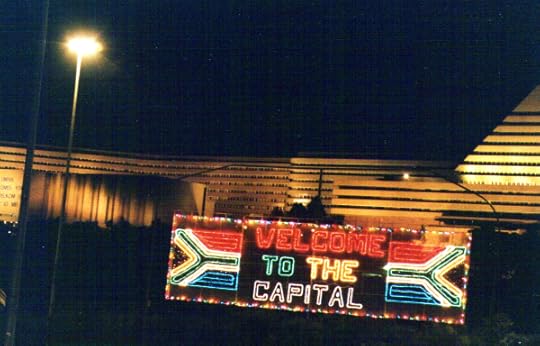

Pretoria illuminated for the presidential inauguration of Nelson Mandela, May 1994

Presidential Inauguration, Tuesday 10 May 1994

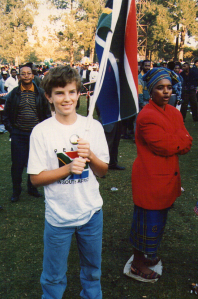

Jethro Hayes 13th birthda, 10 May 1994. At Union Buildings for presidential inauguration.

It was our son Jethro’s 13th birthday. We gave him presents, then went to the Union Buildings for the presidential inauguration ceremony. We parked at the Art Gallery, but had to walk right down to Hamilton Street and back to get into the grounds. There were police and ANC marshals doing body searches, but there was generally a friendly atmosphere.

We were quite early, and got up near the top end of the Botha lawn, where we could watch things on a big TV screen. The place filled up gradually. The proceedings were delayed because Al Gore, the American Vice President, was late and kept everybody waiting. He didn’t get any cheers when he arrived. There were loud cheers for archbishops Trevor Huddleston and Desmond Tutu, and for political leaders like Kenneth Kaunda, Fidel Castro and Yasser Arafat.

After the actual inauguration, which was very short, there was a 21 gun salute, and a fly-past by the air force (including nine Harvards and nine Dakotas in formation – probably a unique sight of so many antique aircraft), and helicopters flying the new flag. All produced great cheering, and singing of songs in praise of Mkhonto Wesizwe – “they’re ours now” seemed to be the general feeling.

Symbolic doves were released, and circled over the city. When Verwoerd released one at the founding of the first republic, it fluttered to the ground and sat there. When one was released at Chris Hani’s funeral, it went into the grave. If such symbols mean anything, this one seemed to say that the time is indeed right for peace. When the Ciskei celebrated its “independence” the flagpole fell over. But apart from some delays (apparently caused by American security officials guarding US Vice-President Al Gore) this one went off without a hitch.

Thundering jets -- the sound of freedom

The theme of the concert afterwards was “one nation, many cultures”, though we went home before the end to watch South Africa thrash Zambia 2-1 in a soccer match. Maybe our team were still on a high, because it was indeed an exhilarating day.

In speeches since the election, and especially at the inauguration, Nelson Mandela has emphasised the theme of national unity. He sometimes wagged his finger, but it was not the imperious finger-wagging for which PW Botha was notorious. It was gentler, more grandfatherly. Perhaps what we were seeing was not so much the inauguration of the president as the adoption of the grandfather of the nation.

My own thoughts of that time were summed up by Psalm 125/126

When the Lord turned again the captivity of Sion: then were we like unto them that dream.

Then was our mouth filled with laughter: and our tongue with joy.

Then said they among the heathen: the Lord hath done great things for them.

Yes, the Lord hath done great things for us already: whereof we rejoice.

Turn our captivity, O Lord: as the rivers in the south.

They that sow in tears: shall reap in joy.

He that now goeth on his way weeping, and beareth forth good seed: shall doubtless come again with joy, and bring his sheaves with him.

When I read the last verse of the Psalm, I think of all the struggle heroes, like those I mentioned in the preceding post: Cosmas Desmond, Elliot Mngadi, Jerome Mbele, Mike Ndlovu, Enock Mnguni and countless others. Some lived to see that day, and some didn’t. But through their struggle, that day at last came.

Masibeke uxolo phambili!

April 25, 2012

Cosmas Desmond: human rights activist

Today, April 26, is the occasion of a memorial service in London for human rights activist Cosmas Desmond who died last month, so I thought it might be a suitable occasion to write something about him, and some of the issues that he was concerned with, so that those who knew him can be helped to remember, and those who didn’t know him can learn something of how he, as a Christian, worked for human rights.

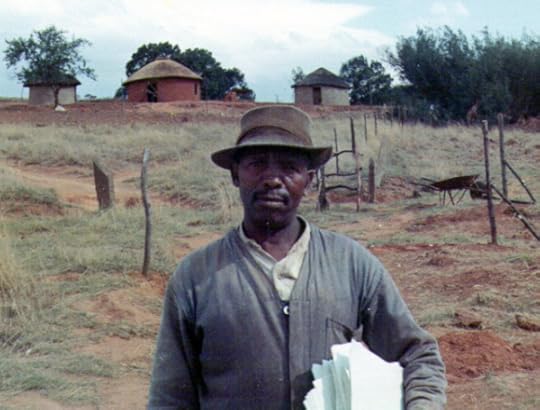

Cosmas Desmond, 1968

I first met Cosmas Desmond in September 1968, when I saw a friend, Shirley Davies, sitting with him at a table on a busy pavement in Eloff Street, Johannesburg. They were collecting signatures for a petition against population removals. Shirley introduced me to Cos, saying he was a Roman Catholic priest from the Diocese of Ermelo, which covered northern Natal and what was then the south-eastern Transvaal. That was an area where there had been a lot of forced removals, as part of the ethnic cleansing that took place in the implementation of apartheid.

It was when he was based at the Maria Ratchitz Mission, between Dundee and Ladysmith, that he became concerned about the forced removals. The Maria Ratchitz mission was an an area that had been proclaimed “white”, but had lots of black tenants who lived there and farmed. One of the mission practices in early days was to establish such farms, which were settled by early converts to Christianity, where they could be close to the church. It was a transplantation to Africa of the idea of a medieval European village. But now the area was “white”, and so the black tenants had to go. It was a “black spot” in the white area on the map, which must be rubbed out.

Shirley Davies collecting signatures in a petition against population removals in Eloff Street, Johannesburg.

I joined Shirley at the table while Cos went off for a well-deserved cup of coffee. And over the next few weeks I got to know him better. The government took no notice of the petition — it never did, but at least it made them aware that not everyone accepted their policies.

At that time the focus was on a resettlement area called Limehill, which was in Cos Desmond’s parish, and it was the place to which people from Maria Ratchitz were being moved, not only from church-owned farms, but from other places that had been declared “blackspots”, such as freehold land that had been bought by black syndicates before the Natives Land Act of 1913 prohibited such purchases.

I was familiar with the removals that were taking place because a few years before, in 1964 and 1965, as a student at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg, I was a member of the Liberal Party, which had been very active in fighting the blackspot removals, especially in Natal, and many of the party’s members were themselves under threat of removal. The Liberal Party had been forced to disband in May 1968, because of the passing of the Improper Interference Act, which prohibited multiracial political parties, and even interracial political discussions. Perhaps the government thought that that would be the end of resistance to its ethnic cleansing programme, but scarcely had the Liberal Party disbanded when Cos Desmond came on the scene, publicising the removals and the misery they caused.

In the same week that I met Cos Desmond the Message to the People of South Africa came out, and when a Zulu version became available we went on a tour of northern Natal, visiting some former members of the Liberal Party, and some of Cos Desmond’s former parishioners, distributing copies of the Messagewith its attack on the ideology of apartheid.

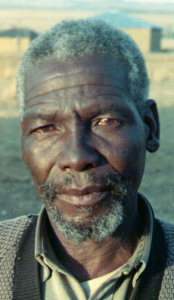

Elliot Mngadi

We drove to Ladysmith on 30 Septermber 1968, and spent the night at the Franciscan Priory there (Cos was at that time a member of the Franciscan Order), so it was on that trip that I really got to know him.

The next morning (1 October 1968) after breakfast at the priory with the other Franciscans, we went to see Elliot Mngadi. He had been the Northern Natal organiser for the Liberal Party, and chairman of the Northern Natal African Landowners Association, and was very active in opposing the removals until he was banned in 1964.

I will describe most of the rest of the day as I wrote it in my diary at the time. Though the description is quite long, it can also give a glimpse of what the time was like:

Cosmas and I went out to Roosboom to see Elliot Mngadi. We showed him the Message, and he glanced through it, and said he thought it very good, and that he was glad to see that the church is at last doing something. We explained the hope we had that it could be distributed among the laity and that they would put pressure on the church leaders to support it and put it into practice. He said he would help us in whatever way he could, but at present he had to go to see about a dead friend’s estate, as he was one of the executors of the will, and as that meant much counting of cattle, and waiting for a boy to run and fetch the cattle, he suggested that we come back in the afternoon.

We agreed to do that very thing, and decided to go off to see Neil Alcock, and drove to Maria Ratschitz, a Roman Catholic Church farm, which was near Lyell-Meran, where people were even now in the process of being moved out of the black spot to the rural Bantu city of Limehill.[1]

Cosmas told me that Church Agricultural Projects, while it was a step forward, was still very much of a capitalist venture. The people who owned cattle were encouraged to pool them in the venture, but it was more like investment in share capital, because the people who contributed cattle were very often families whose men were working in the town so the actual work on the farm was done by people who were paid wages to do it.

When we got there, the Alcocks were out, so we talked to the African bloke who worked in the office. We gave him a copy of the Message to read, and he too said it was about time that the church said this, but he thought it was too late, and that it was a waste of time distributing the Zulu version, becuse only the whites had the power to change the situation. He said he wasn’t prepared to do anything about it himself, because he didn’t want to end up on Robben Island. We tried to convince him that he could put pressure on the church, but having been brought up in an authoritarian church tradition, he said he thought the clergy must give the lead and tell the laity what to do, and not the other way round.

Another bloke there, a Methodist who was a health educator, seemed to have much the same ideas — scared to stick his neck out — and he said you could ask any of the people at Limehill whether they liked living there, and they would all say yes, and that they are satisfied, because they knew it would be the worse for them if they didn’t, and they would only get into trouble.

We left some copies of the message for Neil Alcock and Creina, and asked them to distribute them around the place. Then we drove on through Meran, and the government lorries were still coming through to take people over to Limehill, and the hills around were all over broken and abandoned houses. We went up to Inkunzi, and called at the house I had been to some three years before for a Liberal Party meeting, which had had to be cancelled because the car had broken down and we had arrived after dark. I wasn’t sure if I could remember the place, but it was the right one.

There was an old man sitting on the stoep, and we gave him a copy, but he did not seem terribly keen on it. The women, however, seemed quite interested. They said they knew of Peter Brown and Mike Ndlovu, but they had been told that if they ever had anything to do with that lot, they would be arrested. We explained that this was nothing to do with the Liberal Party, but was put out by the churches, and they turned out to be Anglicans, attached to St Chad’s.[2]

Cosmas, who speaks Zulu well, asked them if they would like to take some more copies of the Message to distribute, and the women said they would, but the old man said no, they would just take the ones they had, and show them to selected people. They seemed very timid. We said goodbye and left.

At Elandslaagte we turned off onto a farm road, which went through several gates, which were mostly open at this time of the year, but in summer when the crops are planted they are closed to stop the cattle wandering in the fields. At the end of this road lived a school teacher Cosmas knows, and we went to see her, but she had gone into Ladysmith and would not be back till 2:00.

We went on to St Chad’s, a few miles nearer Ladysmith. The new rector is Arthur Reynolds, and I don’t know him at all, but his wife is supposed to be some sort of relative of mine. There were a number of small children, one being fed by a nanny, and there seemed to be a whole army of servants running the place. Mrs Reynolds came out, a plump and dreamy sort of woman. She did not invite us in to discuss anything, but said her husband might be interested in the Zulu version of the message, and Cosmas said that she might as well take some, seeing they are easier to get rid of than they are to get. She said that the Krafts had moved to Zululand it it had been terrible for them because there had not been a house for them, and they had had to live in two rooms. Cosmas said to me afterwards that that was probably a good thing, since most of their parishioners had to live in two rooms too.[3]

We had promised to meet Mngadi at 3:30, and it was now only 2:00, so we went back to see the school teacher, Margaret Kunene. She was still not back, but we waited and had tea, and she then arrived on the bus. We showed her the Message, and she was quite pleased with it, but she said she found it difficult to understand since the Zulu translation was so bad. But she took a few anyway, and said she would distribute them. She had been a teacher at Ratschitz, but said she was now going to teach at a community school somewhere near Volksrust, and tried to persuade Cosmas to come next weekend to give her a lift there. and eventually he lent her the money for the transfer, reckoning that it would be cheaper than coming to give her a lift.

Jerome Mbele, former chairman of the Liberal Party branch at Acton Homes, west of Ladysmith.

. We then went back to Ladysmith and through to Roosboom, where we fetched Elliot. He said that he is secretary of his church, the Christian Catholic Church, and he might be in a position to get them to accept the Message. We drove first of all to Acton Homes, to see old man Mbele, who was out drinking beer with a neighbour, but came running when he saw us, and was overjoyed to have visitors. We went inside out of the wind, which was blowing very strongly, and sat down to discuss the Message. Elliot explained it to him, and then he read a bit, and he was overjoyed by that too, and said it was just the thing he had been waiting for.

Elliot went on explaining but old man Mbele sat there with a faraway look in his eyes, not taking anything in, but

busily planning how he would distribute it, and the meetings he would call. Elliot explained that we were not reviving the Liberal Party, but that the Message came from the churches. Mbele waved his hand impatiently, “I know, I know, we’re just calling it a different name.” He said he would go to the local minister (he and most of the other people in Acton Homes are Methodists). He also said he would distribute it in Hambrook and Green Point as well.

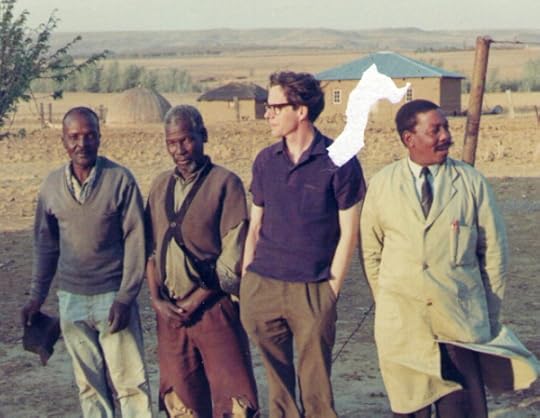

Cos Desmond, with Elliot Mngadi on his left and Jerome Mbele on his right, 1 October 1968

Elliot said it would be unwise to call big meetings, because the SB would suspect that the Liberal Party was reviving. So Mbele said no, he would discuss it with people in small groups, over tea, and read it out and see what could be done. We explained about the “Obedience to God” groups in Johannesburg, and suggested that they might start similar groups here. Mbele was so keen to go out delivering that we felt if we hadn’t been there, he would be off on his bicycle already. So we took a couple of photographs, and saw a couple of his friends, and left.

We went on to Rookdale, where Mike Ndlovu lives, arriving there at sunset. Mike was not yet home from work — he is a foreman at the creamery in Bergville — so we sat waiting for him for a while, and his wife composed tea. At 6:30 he had still not arrived, so we left, but left behind some of the copies of the Message, and Elliot said he would write to him or go to see him to explain what it was all about. We called at the creamery on the way back, but found that Mike had knocked off at 4:30, so I suppose he must have been visiting friends. We took Elliot back and dropped him at Roosboom, and then headed for Maritzburg. [End of diary entry]

We slept that night at the flat of my cousin Jenny Growdon, and talked to John Aitchison, who was till banned, and had been very active in campaigning against the blackspot removals until he was banned in 1965 (John and Jenny were married a few months later). We talked about the possibility of starting a Christian kibbutz or commune. The next morning we tried to see several people in Pietermaritzburg, including Peter Brown, the banned former chairman of the Liberal Party, but all were out. We went to Edendale to see the Anglican priest there, Fr Richard Masemola.

More diary extracts, Wednesday 2 October 1968

We went out to Edendale to see Fr Masemola; he wasn’t in, but his wife was, and she gave us some lemon squash. We left her some copies of the Message, and she said she would give one to Mr Rakabe, who is one of their parish representatives to Synod. She spoke of her children, one of whom has just finished matric and is hoping to go to Cambridge. She said her mother had been moved to Limehill, and is living there in a tent.

We left and called on Selby Msimang, but he too was out. We left some copies of the Message there for him, and went on our way. It was now quite cool, having got overcast. The road down the Umkomaas Valley had altered out of all recognition. It has been replaced by an altogether new road, cutting out all the bends and ups and downs. Rather sad in a way — the old one was more fun to drive along. The other side of the river was still as it had been, however, with the road winding steeply up the hill.

When we reached Bulwer it was about midday, and we stopped for petrol and had lunch at the hotel and a couple of beers also. Quite pleasant, really. We went on, and beyond Bulwer found the road had been widened. At the Pevensey turn off we came across a woman wearing the uniform of Mnguni’s church, and stopped to see if we could give her a lift, but she was going the other way. We gave her a copy of the Message, and she said that she couldn’t read, but would get someone to read it for her. She also said she knew and remembered me.[4]

We went on to Swamp, the little village near Pevensey, and there called on Mrs Keswa, who had been a leader of the Liberal Party around there. We first saw the old granny, who went off to call her daughter Emily. They were Anglicans. We gave them copies of the Message and explained it to them. The young Mrs Keswa said she had been kicked out of the church, because she had started practising as an isangoma, which is why she now goes around with no shoes on. She had always had these powers, she said, but now her grandfather and grandmother (who are both dead) have told her to use them, and she even helps white people. And even though she had been kicked out of the church, she still believed, and they seem quite willing to distribute the Message. and call meetings to discuss it.

Emily Keswa's home at Swamp, near Pevensey. The number on the door was not to facilitate postal deliveries; it rather indicated that the homestead was scheduled for removal.

Then we left and went on to Mnguni’s place. At first I didn’t recognise it, and thought that perhaps they had been moved, because there was a whole new system of buildings and fences, making his house inaccessible by car, but then we saw Mnguni, making a fence. He was very pleased to see us and came and sat in the car while we explained about the Message, and he too seemed to think it a good thing. We asked about Miya and Duma, and he said Miya was in Lesotho, but he would be seeing Duma on Saturday, and would give it to him then. I gave him the R10.00 that John had given me.

Enock Mnguni, former chairman of the Stepmore branch of the Liberal Party, with copies of the Message to the People of South Africa for distribution

Then we left, and Fr Desmond drove back to Ladysmith via Nottingham Road. We had run out of money by this stage, so at Ladysmith we called in at the friary to get some, and the nuns gave us supper. They are all Franciscans there, like Cosmas himself, and run practically the whole area between Ladysmith and Ermelo. When we were on our way back to Joburg he asked me how serious John and I were about this kibbutz and printing press idea, and I said we were fairly serious about it, and hoped it would come into being some day. He said a number of their order had only come here on the new one-year permits, and they were just now having to apply for renewals, and if they were not granted a number of them might be interested in trying to set up some sort of Christian kibbutz community in some neighbouring country.

The trip back to Joburg was largely routine and a bore. I took over halfway, and drove the rest of the way back home. When I arrived Mum said the SB had been to visit, saying they had a document for me from the Department of the Interior. She was convinced it was a banning order, but I told her the Department of the Interior issues passports, not banning orders, and they probably wanted to confiscate my passport. [end of diary entry][5]

Though the diary entries are rather long, I’ve included them because I believe that that trip may have helped influenc Cos to become a full-time campaigner against the forced removals. Up till then he had been concerned primarily as a parish priest whose parishioners were being moved, and he saw the conditions in the places that they had been removed to. On the trip he met others who had earlier been involved in the campaign against removals, and who had been banned as a result. Soon afterwards he was given funding to engage in research on the removals, and so he travelled around the country gathering information that was eventually published as The discarded people. And, as a result, he too was banned.

Some Natal Liberals who had been banned: Heather Morkill, Ken Hill, Selby Msimang, Cosmas Desmond, Jean Hill, Stephen Hayes, Enock Mnguni, E.V. Mohamed, John Aitchison, Peter Brown. 1976

The picture shows a group of Natal Liberals who had been banned, gathered to celebrate the lifting of John Aitchison’s second 5-year banning order. Cos Desmond was the only one who had not actually been a member of the Liberal Party, but he belongs in the picture because he too had taken up the fight against population removals, and he too had been banned as a result.

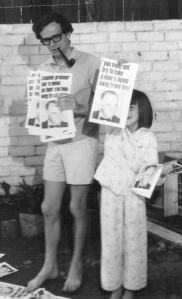

You must not take a man's home away from him." Cos Desmond and Elizabeth Davies burning surplus posters of the anti-removal campaign

Part of the subsequent campaign against the removals was based on something said by the then South African Prime Minister, John Vorster, in another context, “You must not try to take a man’s home away from him.” The saying, and Vorster’s picture, were printed on thousands of posters, because of course that was precisely what Vorster’s government had been doing. At the end of that particular campaign, there were a lot of surplus posters, and Cos and Elizabeth Davies took great pleasure in burning them in a bonfire.

While he was travelling around collecting material for his book Cos often stayed with the Davies family in Johannesburg. John Davies was the Anglican chaplain at the University of the Witwatersrand, and his wife Shirley was an active member of the Black Sash, a women’s group that also campaigned for human rights. Their children, Mary, Mark and Elizabeth, also appear with Cos in some of the pictures below.

Cos eventually left the Franciscan order (OFM), and married Alethea (Snoeks) McLagan, and they had three children.But even after leaving the Franciscans, he kept the name he had used in the Order, Cosmas, rather than reverting to his baptismal names, Patrick Anthony.

After his ban was lifted they went to the UK, where Cos took a broader interest in human rights by becoming the director of Amnesty International, which is concerned to care for political prisoners.

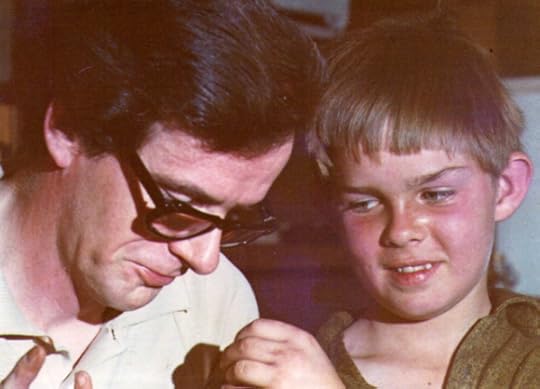

Cosmas Desmond and Mark Davies, 1969

He returned to South Africa in the 1990s, when apartheid was ending.

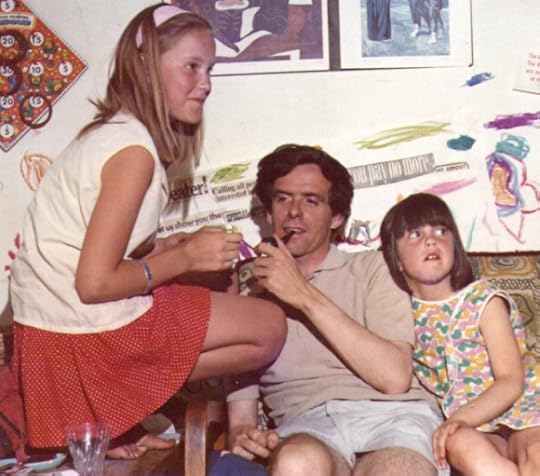

Cosmas Desmond with Mary and Elizabeth Davies, 1969.

This blog post is partly a kind of “in memoriam” for Cos Desmond, with my most vivid memories of him, but it is also to commemorate those others who were involved in the same stuggle against apartheid, ethnic cleansing, and the forced removals that took place to implement that grotesque ideology — Elliot Mngadi, Enock Mnguni, Mike Ndlovu, John Aitchison, Chris Shabalala, and others.

For more on Cosmas Desmond himself, see the excellent Guardian obituary here.

Back in the 1960s we did not use the term ethnic cleansing. We used terms such as “resettlement”, “relocation”, “blackspot removals”, “forced removals”. The term ethnic cleansing came into use in English during the Wars of the Yugoslav Succession in the 1990s, but it accurately describes what was going on in South Africa between 1950 and 1990, so I have used it in this article. The definition of ethnic cleansing is “the planned deliberate removal from a specific territory, persons of a particular ethnic group, by force or intimidation, in order to render that area ethnically homogenous.”[6]

The main human rights, or rather violations of them, dealt with in this post are included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Article 17.

(1) Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others.

(2) No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.

As for the theology, I’ve gone into that more generally in my other post on Theology and Human Rights.

But for the theological take on these specific violations of human rights, see the story of Naboth’s vineyard in I Kings 21.

And also:

Isaiah 5:8 Woe unto them that join house to house, that lay field to field, till there be no place, that they may be placed alone in the midst of the earth!

And finally:

Deuteronomy 27:17 Cursed be he that removeth his neighbour’s landmark. And all the people shall say, Amen.

____

Notes

[1] Neil Alcock was a farmer who started Church Agricultural Projects, the aim of which was to encourage church-owned farms like Maria Ratchitz and St Chad’s to develop into cooperative farms. He married Creina Bond, a former journalist who had written several stories on population removals for the Natal Daily News.

[2] St Chad’s was an Anglican mission farm, similar to Maria Ratchitz, east of Ladysmith.

[3] Ann Reynolds was in fact my second cousin, and it was my grandmother who had told me that we were related, though this was the first time I had met her. The Krafts were the Revd Richard Kraft and family, who had been at St Chad’s for nearly five years, before Rich Kraft was asked to be Director of Christian Education in the Anglican Diocese of Zululand. He later became Bishop of Pretoria and died in 2001.

[4] Enock Mnguni belonged to the UkuKhanya Presbedia Church, which had broken away from the Presbyterian Church in Africa. The women wore very distinctive red and green uniforms. It had been founded by Timothy Cekwane in 1910, inspired by visions after seeing Halley’s comet. The leaders and ministers made a great thing of being strictly non-political, which made Mnguni himself something of an anomaly, as chairmman of the local branch of the Liberal Party. The Security Police (SB), knowing this, tried to get the clergy of the church to put pressure on Mnguni to leave the Liberal Party, but they did not succeed. Mnguni did not bow to the pressure, and he was too valuable a member of the church for them to kick him out.

[5] The SB called back the next day and confiscated my passport.

[6] For more on ethnic cleansing in the Wars of the Yugoslav Succession, see my article on Nationalism, violence and reconciliation, and the Wikipedia article on ethnic cleansing.

Links

This post is part of a synchroblog on Theology and human rights. The topic was suggested by Phil Wyman, the originator of the synchroblog concept, but I’ve already said most of what I want to say on the theological basis for human rights in an earlier post here. Links to the other posts in the synchroblog will be posted below as they are received.

April 23, 2012

Migration, mission and theological education

I’m hoping to attend a conference in Pietermaritzburg in July on the topic of Migration, mission and theological education.

That’s my abbreviation of the topic, which is actually quite a bit longer, namely, Migration, human dislocation, and the Good News: margins as centre in Christian mission and challenge to theological education.

If anyone is interested in attending, here are the details put out by the organisers, and you can find some more information here.

ETE OF WCC AND SAMS PRESENT: A COLLABORATIVE CONFERENCE IN THE JOINT CONFERENCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF KWAZULU-NATAL IN PIETERMARITZBURG FROM 18-22 JUNE 2012

INTRODUCTION

As a follow up to the collaborative conference between the Program for Ecumenical Theological Education (ETE) of the World Council of Churches (WCC) and the Southern African Missiological Society (SAMS) at the Joint Conference of academic societies in religion and theology at the University of Stellenbosch in 2009, ETE and SAMS will once again present a conference in the Joint Conference at the University of Kwazulu- Natal , Pietermaritzburg. The Pietermaritzburg conference takes place from 18-22 June 2012.

CONFERENCE THEME

We have chosen as a theme for the conference an adapted version of the theme for the 13th quadrennial assembly of the International Association for Mission Studies (IAMS) WHICH IS SCHEDULED FOR Toronto, Canada from 15-20 August 2012:

MIGRATION, HUMAN DISLOCATION, AND THE GOOD NEWS: MARGINS AS CENTRE IN CHRISTIAN MISSION AND CHALLENGE TO THEOLOGICAL EDUCATION

Apart from borrowing from IAMS, it was necessary also to cater for both ETE and SAMS. This explains why there is a clear cut missiological component as well as a component catering for ecumenical theological education. We are extremely happy to say that all of this feeds into the journey embarked upon by ETE in its vision on A JOURNEY OF HOPE FOR AFRICA. At the September 2002 conference at the Lutheran Conference Centre in Kempton Park in South Africa, the call for a new vision of life for Africans and the world, from the Harare Covenant of Africans at the 8th Assembly of the WCC, was echoed. In Kempton Park theological education was seen to be a vital area for the preparation and equipment of much needed new leadership for African churches and for countries who will give shape to a better future for all in the continent. Kempton Park sounded a clear call for the continued contextualisation of theological education and the development of textbooks in Africa by Africans. More issues in and for theological education were identified at the Maputo Assembly of the AACC in December 2008 like economic justice and good governance, conflict resolution, peace building and reconciliation, health and education and the issues of spirituality, identity and unity.

The theme chosen for the next Joint Conference in Pietermaritzburg could be seen as a follow up to all of these issues. It is quite amazing that migration has not really been identified yet as a major challenge to Christian mission and theological education in Africa. In a real sense therefore, the ETE-SAMS Conference in the Joint Conference focuses on a neglected and grossly under researched area.

SECOND AND FINAL CALL FOR PAPERS

(PLEASE NOTE THAT HOSE WHO HAVE ALREADY SUBMITTED ABSTRACTS TO REGGIE NEL NEED NOT DO SO AGAIN)

We offer those of you who have not yet submitted papers for the conference the opportunity to do so before 31 March 2012. Abstracts of between 150-200 words are to be submitted with Reggie Nel, who acts as coordinator of the research project. His e-mail address is as follows: RWNel@unisa.ac.za. A basic criterion is that the topic chosen should be aligned to the overall theme of the conference as shown above. A total of twenty four (24) one hour slots are allocated to ETE-SAMS which means that we need to find at least twenty presenters of papers. The other four slots will be used for meetings and sessions aimed at the strengthening of ties between ETE and SAMS as well as a discussion on the cooperation between different theological institutions. You will be notified by 15 April whether your abstract has been accepted. Full papers of not more than 6000 words must be submitted by 31 May 2012. The Harvard reference technique is to be used for the writing of the paper. In dealing with migration a wide range of issues come to mind: types of migration, security, socio-economic issues, political issues, cultural issues, health, transport, poverty, unemployment, children, women, racism, sexism, classism, xenophobia, violence, religion, ecology, education , peace building, conflict resolution, identity and unity etc. Important questions in choosing a topic for your paper will be: where is Christian mission located in all of these matters in their connectedness to migration? Where is the church located? Where is theological education located in these matters in a continent where migration has become a way of life? The papers should either be aimed at problem solving or hypothesis generating.

CONFERENCE COSTS

An early warning is hereby sounded that the conference is quite expensive. This is not to deter anybody from participating, but rather to encourage you to do careful planning in finding the necessary funding at your institution or elsewhere. To assist you in planning your participation in the conference carefully, please look at the following guide:

The registration fee is R950 per academic and R750 per student. There are two deadlines for registration: early registration closes on 30th April 2012 and late registration closes on 31st May 2012.

Conference bags will be available at R100 per piece

Travel costs

Accommodation costs (probably at the Seth Mokitimi Methodist Seminary) at R300 per person per night (4 nights @R300= R1200)

Subsistence (breakfast, lunch and dinner): at the Lutheran Theological Institute at R200 per person per day= R800

Conference dinner at R300 per person

Transport (internal): Local travel from the two airports, i.e, Orbi in Pietermaritzburg and Shaka in Durban will cost you R25 and R700 respectively one way; additional travel costs will be incurred if transport is needed between the conference venue and the residences which may amount to R100 for the four days.

WEATHER

The month of June is in the heart of winter in South Africa. In the area where the conference takes place it can become quite cold during winter time, particularly in the evenings. Temperatures range from 8-21 degrees Celsius during the day to between 0-5 degrees at night. You are therefore advised to bring warm clothes, a raincoat and an umbrella as it can quite easily rain any time of day.

CONCLUSION

Feedback on the 2009 Joint Conference suggests that for some it was quite a memorable occasion. Colleagues from South Africa were excited about meeting colleagues from Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. A new relationship with the AACC was established and needs to be taken forward now. Perhaps the Pietermaritzburg experience might even be greater. We are looking forward to seeing at least forty to fifty participants for the ETE-SAMS conference.

Yours in the missio Dei and in Ecumenical Theological Education

Dr Dietrich Werner

Program Coordinator: ETE of WCC

Prof Nico A Botha

General Secretary SAMS

I think it’s a pretty important topic, and though patterns of migration have changed over the last 50 years, in trying to discover the significance of present patterns and how to deal with them, it can also be instructive to look at attempts to deal with migration in the past. One of the major patterns of migration in South Africa in the past was, of course, the ethnic cleansing that took place between 1950 and 1990 to implement the apartheid policy, in which about 3-5 million people were forced to leave their homes.

Now, however, we perhaps have almost as many migrants, many of them refugees, from Zimbabwe, Congo and other countries, which has also led to an increase in xenophobia.

The expense of the conference is, however, a bit off-putting.

I’ve worked out that the cost for me to attend, travelling from Tshwane, is R4600.00. That’s roughly $US 615.00, or 385 British pounds; about my average monthly pension. It’s calculated on the basis of my travelling alone by car. If I went by plane I’d have to add the plane fare to that figure, and the cost of getting to the airport at this end (about R240 on the Gautrain). The cost of petrol to travel all the way from Pretoria is about the same as the cost of the transfer from King Shaka Airport to the Conference venue and back again. So if I can find one or two people to come with me in the car, sharing the petrol cost, it will come out a bit cheaper. Leave a comment below if you’re planning to travel to the conference from Tshwane and might be interested in joining me on the journey, but be warned, I don’t do toll roads, so there might be quite a bit of pothole dodging.

Call for contributions: Synchroblog on Theology and Human Rights

It has been suggested that we have a synchronised blog (Synchroblog) on the topic “Theology and Human Rights” on Thursday 26 April 2012.

If you would like to join in, then write your blog post on the topic. I suggest that people in the Americas do it in the morning, those in Africa and Europe do it about midday and those in East Asia, Australia, New Zealand etc do it in the evening.

As soon as you have posted your contribution, copy the URL for your post from your browser and send it to me in an e-mail message in the following format

NA Poster’s name

BL Poster’s blog name

TI Title of your post

URL Url of your post

REL Your religious background

EM Your e-mail address

If you use that format — with the preceding tags in capital letters followed by a single space, and each piece of information on a separate line (it can word-wrap), I will be able to import it straight into a database without re-typing, and produce a report with the HTML code for the links which can then be appended to your post. I will post them on my contribution, and the easiest thing will be to copy and paste them from there. But I will also send it by e-mail to all the registered contributors (to the e-mail address you provide, so don’t munge it).

If you send it to me by e-mail at

shayes (at) dunelm.org.uk

it will avoid cluttering up the mailing lists with lots of messages about addresses and titles of blog posts.

Afterwards we can discuss the Synchroblog on the forum Christianity and Society

April 21, 2012

Holocaust memorial

Holocaust Remembrance Day (Yom HaShoah) began in the evening of Wednesday, 18 April 2012, and ended in the evening of Thursday, 19 April 2012.

I didn’t know that, although I have seen quite a few blog posts that have referred to it, so obviously some people knew. I just wondered at why people were mentioning it all of a sudden.

One of the posts I read had this picture (hat-tip to The Poor Mouth), which I thought was quite telling.

The Hebrew caption reads Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day 5772

One of the thoughts that comes to mind is how little we have learned. People in many different parts of the world reacted with shock and horror when they heard of the extent of the Nazi attempt at genocide, and indeed those events added the word “genocide” to our vocabulary. Yet much of the force of the word has been lost because of attempts to trivialise it, and apply it to something less than the planned and deliberate attempt to exterminate a race of people.

Not all ethnically related violence is genocide, though sometimes people speak as if it were. And sometimes people use “genocide” as if it were not ethnic violence at all. All killing of other human beings is evil, but not all killing of other human beings is genocide. And so it is good to be reminded of what genocide really means.

It doesn’t mean just ethnically-related violence, nor does it mean killing a large number of people. Some referred to the killing of hundreds of thousands of Cambodians by the Khmer Rouge in 1975 as “genocide”, but it wasn’t. Cambodians killing Cambodians is not genocide. The reason for the killing was not that those who were killed belonged to another race, but because the people who were killed were considered to be not politically correct. Actually it wasn’t even that, because the killers didn’t even bother to find out the political views of many of those they killed. It was the raw assertion of political power. It was a case of “We can kill you so you had better do what we say, and even if you do what we say we may still kill you to convince others that we are serious, and so we will kill you just because we can.”

The killing of a similar number of people in Rwanda 20 years later was more like genocide, because it was based on ethnic hatred.

I mention these things because one of the worst trivialisations of the word “genocide” takes place right here in South Africa, and can be seen in web sites like this one. There are people who deliberately attempt to equate “farm murders” with “genocide”. This is a kind of mischievous propaganda that is calculated to deceive, though perhaps some of those who spread it are self-deceived by their own propaganda. They are trying to create the impression that “farm murders” are all part of a deliberate plan to exterminate the “Boer race”.

But let us examine the words more soberly and objectively.

“Farm murders” are murders that take place on farms, as opposed to, say, cities and suburbs. The “genocide” propagandists like to ascribe all these murders to a single cause: genocide. They do not provide any evidence for this assertion, other than gruesome pictures of murder victims. The picture itself is supposed to be “proof” that the motive was “genocide”.

But murders on farms, like murders in other places, take place from a variety of motives. To equate farm murders with “genocide” is simplistic.

Also, the “genocide” conspiracy theorists like to give the impression that all “farm murders” are murders of farmers. But they are not. Some farm murders are murders by farmers of their workers, or of trespassers, or of alleged tresspassers.

One motive for farm murders is labour disputes. There is a dispute between employers and employees which escalates to the point where one party kills the other. The police sometimes point out that very often a murderer is someone known to the victim — a family member or an employee or employer. And this applies to farm murders as well.

One of the common motives for farm murders is robbery, and robbery with violence, or the threat of violence, is all too common. For that purpose, farms are seen as a soft target because of their relative isolation. There is time for the robbers to make a getaway.

What I have not found is any evidence that the motive for farm murders is “genocide”. The perpetrators are sometimes caught, tried and convicted. In how many of these cases has the motive been proved to be “genocide”? If the genocide propagandists can show that this morive has been proved in the majority of cases (a 51% majority will do), then I will be prepared to take their contentions seriously. But until they do that, I will take their assertions with several bags of salt, and merely white racist propaganda. Sannie sê Sannie sal sewe sakke sout sleep.

Some of those who maintain the genocide theory refer to a slogan “Kill the Boer, kill the farmer”, coined by Peter Mokaba, an ANC leader, who used it a lot in the early 1990s. The media confused this slogan with a struggle song that contained the words “dubul’ amaBhunu”, which can be translated as ” shoot the Boers”. But, apart from Peter Mokaba’s silly and irresponsible slogan, there is a difference between “Boer” with a capital letter and “boer” with a small letter. There is a historical precedent: during the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) British troops came to South Africa in l;arge numbers to “dubul’ amaBhunu”, because while “boere” with a small “b” means “farmers”, “Boere” with a capital B meant citizens of the South African Republic (ZAR) and the Republic of the Orange Free State, which in that period were at war with the Britsh Empire and its local representatives, the Cape Colony and the Colony of Natal.

After the Anglo-Boer War, and the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, the National Party was formed to promote and develop the spirit and ideology (as they saw it) of the Boer Republics, and in the 1940s that spirit developed into the ideology of apartheid. Thus “Boer” and the Zulu version “iBhunu” came to represent the apartheid ideology and its supporters. And they called themselves “Boere”, no matter how urbanised they might be. And this was what the struggle song referred to — the destruction of the ideology of apartheid and the power of the apartheid regime.

And there is no ambiguity in the Zulu words. The Zulu word “amaBhunu” does not mean farmers, it means Afrikaner nationalists collectively. The Zulu word for farmer is “umlimi” (plural “abalimi”).

It was only the silliness of Peter Mokaba, and the supporters of the genocide conspiracy theory of “farm murders”, that led people to think otherwise.

Farm murders, whatever their motives, are horrible, but they are not genocide.

And the Holocaust Memorial day can remind us of what genocide really means.

April 18, 2012

Some online software tools

I’ve been having a look at some online software tools, several of which are new to me, and which some may find useful.

The first two came to me via Brigada, which is itself a tool worth noting. It has a mailing list that tells about resources, services and tools that might be useful to people involved in Christian mission.

This comes a couple of weeks too late, but it would be useful for people who are trying to compile lists of people to read the Book of Acts on Easter Eve, for for the Maundy Thursday Vigil (if Anglicans and Roman Catholics still have those).

It offers:

Simple wizards for creating your sign up

Public or private online group sign up

Automated email reminders

“Swapping” ability for schedule changes

Attractive and customizable templates

Easy administration tools and stats

Trello is a collaboration tool that organizes your projects into boards. In one glance, Trello tells you what’s being worked on, who’s working on what, and where something is in a process.

Good for planning a trip involving several people, and similar things.

The only hitch (according to Brigada) — it’s online only. So… there’s no Windows, Mac, or linux version.

I haven’t quite made up my mind about this one.

It’s supposed to tell you who you interact with on social networks, and who influences you and who you influence and things like that.

I’m not sure how well it works, though. I think it’s still a work in progress, and it seems to work mainly with Twitter, and not so well, so much, or at all, with other platforms.

Among the rather strange things Klout tells me is that I am influential in Singapore (first and last time I was there was back in 1985) and that I’m more influential in “Celebrities” than in “Christianity” — if you look at the tag cloud in the right side bar you’ll see that “Christianity” is quite big, and “celebrities”, if it appears at all, is very small.

I mostly use blogs, and use Twitter mainly to let people know when I’ve written a new blog post. And what I post on Twitter gets passed on to Facebook. But Klout doesn’t seem to pick up my blog posts or Facebook or Google+ interactions at all.

I learned about Klout via Blog Catalog, which, however, remains but a shadow of its former self. About 2-3 years ago someone decided to revamp the user interface, but never finished the job, so a lot of things no longer work, and the new interface is far more difficult to navigate than the old. There are many things that are impossible to navigate to from within the site, though you can still get to them through external links – a classic example of what comes if you ignore the adage, “If it aint broken, don’t fix it.”

But a member of Blog Catalog visited this blog, and showed up in the Blog Catalog widget in the right sidebar, so I visited their blog, and saw this post: Links to 22 Social Networking Sites. And that’s how I found Klout.

How do some of these tools interact?

The WordPress statistics show that very few people come to this blog from Twitter, so perhaps I’m wasting my time posting announcements of these posts on Twitter. And almost nobody bothers to retweet them. I quite often go to other people’s blog posts when I see them on Twitter, though I tend to ignore tweets without links, mainly because they lack context, and it is rare that anything meaningful (other than “Will be late for dinner tonight”) can be fitted into 140 characters. And that brings me to the last tool which is

… which shows the links posted in tweets on Twitter in a more readable and informative format. I find it very useful as a kind of digest of the best of the tweets from the people I’m following on Twitter, including my own. My only complaint is that sometimes its idea of what is important doesn’t always concide with mine.