Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 70

May 27, 2012

Between Ascension and Pentecost

For Orthodox Christians the time between Ascension and Pentecost seems a strange hiatus. We have taken leave of Pascha, and so no longer sing “Christ is risen”. But we have not yet reached Pentecost, so we do not pray “O Heavenly King”. As in Pascha, there is no kneeling in church — that must wait until after the kneeling prayers at Pentecost Sunday Vespers. Something seems to be missing.

But it seems to be a time for preparation of leaders of the church.

The Twelve elect Matthias to replace Judas.

The Fathers of the First Ecumenical Council

It is the Afterfeast of the Ascension, and the commemoration of the Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council. The Gospel reading is from John 17, the prayer of Jesus for those who would lead the church after his ascension. The epistle reading is St Paul’s address to the elders of Ephesus. and both emphasis that teaching has been entrusted. The word the Father has entrusted to Jesus he has passed on to the twelve, who have all kept it, except for the Son of Perdition, Judas.

St Paul had declared to the elders of Ephesus the whole counsel of God. He had held nothing back — not Gnostic doctrine passed on secretly.

The emphasis is on structural ministries, the bishops, priest and deacons, rather than charismatic ministries — those come after Pentecost, since they are ministries given directly by the Holy Spirit. But these structural ministires for the ordering of the church, the ordained ministries of bishops, priests (elders) and deacons are put in place before the descent of the Holy Spirit. Certainly they will need the Holy Spirit’s power and guidance and wisdom to carry out their ministry. The Fathers of the First Ecumenical Council needed such wisdom to resist the false teaching of Arius, who wished to demote Christ to a mere creature.

It almost makes that ugly phrase in bureaucratese — “putting structures in place — seem useful after all. Because it’s a time of putting structures in place, to be animated by the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.

It’s almost like preparing for a long car journey — checking the tyre pressures, the brakes, oil levels and so on, and then packing everything in, and all it needs is the tongue of fire — the ignition spark, to set off.

Make a good pilgimage!

May 24, 2012

Tales from Dystopia XII: Vorsterism, sabotage and liberalism

Fifty years ago today my conversion to liberalism began, and the instrument of this conversion was a dominee in the Dutch Reformed Church by the name of Cruywagen. It was not his purpose to convert anyone to liberalism, quite the reverse. He was reported in the media as saying that anyone who did not support the Sabotage Bill, then before parliament, did not believe in the fall of man.

B.J. Vorster

The Sabotage Bill had been brought before the South African Parliament by the new Minister of Justice, Balthazar Johannes Vorster, and it was Vorster’s first major step in his rise to political prominence.

After the general election of 1961 Vorster was appointed Minister of Justice by prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd, and he immediately took steps to turn South Africa into a fully-fledged police state.

The main stages of this were the General Laws Amendment Acts of 1962 and 1963, and the Terrorism Act of 1967.

Fifty years ago the first General Laws Amendment Act was dubbed the Sabotage Act by the media, because among its other provisions was one that increased the penalties for politically-motivated sabotage, including the death penalty. One of the provisions also undermined the legal rule of presumption of innocence. If someone was charged with sabotage in terms of the Act, the onus was on them to prove that it was not done with political motivation.

This was ironic, since 20 years earlier Vorster had been an active member of the Ossewa Brandwag, an organisation that carried out acts of politically-motivated sabotage.

The Sabotage Bill also empowered the Minister of Justice (Vorster himself) to impose more severe restrictions on opponents of the National Party government. These restrictions, popularly known as “banning orders“, were now to include house arrest, and also made it an offence for anyone to publish any “speech, writing, utterance or statement” of a person subject to a banning order. As one lawyer commented, it would henceforth be illegal to play a tape recording of the gurglings that a banned person had made as an infant in a cot.

The Sabotage Bill had been announced by Vorster in the Senate on 15 February 1962, and provoked an intense political debate.

The Sabotage Bill was also a precursor of Vorster’s style of government, in which he tried to promote the image of kragdadigheid by legislation.[1] If someone behaved in a way that broke the law (and before Vorster came to power in 1961 there were many such laws passed by his predecessors), Vorster’s response was not to charge people under existing laws, but to pass a new law to make the behaviour doubly or triply illegal, and even then his preference was not to charge them in court, but rather to take administrative measures, by banning them without trial. Thus it was a kind of aggrandisement of power, giving more and more powers to the police in general, and himself in particular, to control and restrict people.

Previously a personwho painted anti-government graffiti on a wall could be charged with malicious damage to property. I am not aware of anyone being charged with that. But the Sabotage Bill greatly increased the penalties for such acts if done with political intent, and the prosecution did not have to show that they were done with political intent — the onus was upon the accused to prove that they weren’t.

B,J, Vorster

There had been a few acts of sabotage before Vorster introduced the Sabotage Bill in parliament — mainly attempts to blow up electricity pylons, few of which succeeded. But they gave Vorster the opportunity to manifest his kragdadigheid by introducing legislation to increase his own powers and those of the police.

He followed this up by another General Laws Amendment Act in 1963, which introduced 90-day detention without trial, something that was quite shocking to people in what was then called “the free world”, though 45 years later Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were anxious to introduce similar legislation in Britain, and George Bush and Barack Obama have been introducing or continuing it in the USA.

At the time the Sabotage Bill was being debated, there were still a lot of ex-soldiers around who had fought in WWII against Nazism, and to some people of that generation legislation like the Sabotage Act recalled Nazi tyranny. Christians in South Africa began taking an interest in the works of theologians like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, which were then being published in English and becoming more widely known. Bonhoeffer became known for his opposition to such tyranny, and so from about 1961 onwards there was also quite a lot of talk in South Africa of the ned for a “Confessing Church” similar to that in Nazi Germany. This intensified the debate about the Sabotage Bill, and subsequent legislation giving more power to the government.

The fact that Vorster had been a member of the pro-Nazi Ossewa Brandwag increased this still further. Someone dug up a statement Vorster had made in 1942, and spead it around:

We stand for Christian Nationalism, which is an ally of National Socialism. You may call the anti-democratic system dictatorship if you like; in Italy it is called Fascism, in Germany National Socialism, and in South Africa Christian Nationalism.

After he introduced the Sabotage Bill, people began asking Vorster if he still stood by that statement, and he generally refused to answer. I was present on one occasion when this happened, when Vorster was speaking at a National Party meeting in the Pietermaritzburg City Hall. I was then a student at the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg (now University of KZN). The meeting was on 4 November 1963, and this is what I wrote in my diary at the time:

In the evening I went down to hear John Balthazar Vorster, the Minister of Justice. I went down with Maeder Osler, Gavin Stewart and Dizzy Drake, and we went a sat up in the gallery. There was a big mob of people we knew there — John Lloyd, Chris Roering, Harry Wilson, Jasper Cook, John Aitchison and many more, mostly from varsity, including Darrell Wood, Henry Bird, Richard Thatcher, and members of staff — Cake Manson, Saul Bastomsky and Glenn Culpeper.

Before the speakers came in there was some shouting across the hall. Some people on the other side shouted “Vrystaat, and we shouted “Natal”, although some thought we should have made it a refined and elegant “Natal” {different vowels in the Shaw alphabet}.[2] When the speakers came in most of the audience stood and clapped. The left — mostly up in the gallery with us — sat and booed. Then we all stood and sang the national anthem. The leader of the party in Natal, a guy called Potgieter, made a speech which sounded like a sermon. Then Vorster stood up and spoke. About 30 people in the gallery stood up and gave the Nazi salue, shouting “Heil Hitler! Heil Vorster!” The tough men the Nats had stationed behind us pulled one guy back into his seat, and he got up again and shouted “Heil Vorster!” He was pulled back several times and it nearly started a fight, but a deacon of the Dutch Reformed Church stopped it — blessed are the peacemakers!

Vorster began to speak. He said he wondered why the West didn’t support South Africa, and told people to take no notice of the vocal section of the audience. He said that there was a building on the hill, the last bastion of liberalism in Natal, but already there were cracks in it. He had, he said, 150 signatures of students who supported his action against Nusas.[3] He invited them to come on to the platform so that he could welcome them, but none did. He then said that the trouble about South Africa overseas was that misinformation was being propagated deliberately. Lloyd shouted “by Frankie Waring”.[4] Then he went on to talk about the United Party, and the resignation of Odell and Groenewald. He said

that Douglas Mitchell had said that if a few fleas fell off it made no difference to the dog, but there were so many fleas that the United Party must be a flea-ridden dog. Lloyd shouted, “Look where the fleas are going to.”

Vorster said that the United Party was dead and that it must eventually come to direct opposition between the conservative National Party on the one hand and the Progressive and Liberal Parties on the other, both of which were liberal — two horses harnessed to the same cart. He said that the vocal section of the audience had their own regiment — “Luthuli’s Own”, and we all shouted “that’s us”, and “Luthuli for President”, and cheered.[5]

He read out of a Nusas pamphlet, and it was so twisted that I didn’t find out until after the meeting what he had been referring to. He talked about communists, and trying to support communists and South Africa’s image overseas. It was actually an appeal to other unions of students to contribute towards a fund for students and lecturers who were arrested for political crimes, to help pay for their legal defence and support their families.

At one stage Lloyd shouted, “That’s twisted”, and Vorster said, “My friend who shouted ‘that’s twisted’ can come down and read it for himself it he wants to”. Lloyd went and sat on the platform and Vorster went on about “little pink liberals”. At the end, after Vorster had said that a part of the Nusas pamphlet referred to obtaining the best legal defence even in corrupt courts was an attempt to smear South Africa’s name overseas. Lloyd asked if the packing of the Supreme Court to get the Coloured voters off the roll was not a corruption of justice. He asked a couple of other things as well. Vorster replied by asking Lloyd if he thought our justice could be bought, and didn’t give a straight answer to his other questions. Sammy Osler asked why Vorster had told lies about Nusas, and said he was prepared to substantiate his arguments, but the chairman took no notice.

Then someone shouted, about the statement made by Vorster in 1942 — “We stand for Christian Nationalism. In Germany it is called National Socialism in Italy Fascism, and in South Africa Christian Nationalism”. He asked if Vorster was prepared to withdraw that statement. Vorster did not reply. The chairman said, “What do you know about it, you weren’t even born then”, and closed the meeting.[7]

Outside a guy asked Maeder Osler if he was prepared to have a discussion of his views. Sammy said yes, and the guy said, “Let’s go round the corner and fight it out.” Sammy said he defended his views with words, and if he couldn’t do that they weren’t worth defending, but he offered to beat the other guy up if he liked, and a Gestapo guy called van Rensburg said “Come on now, Maeder, don’t fight” and we went off. Van Rensburg seems quite a nice guy. We went and had coffee at Gavin Stewart’s place.[6]

The meeting was also interesting in that it marked a stage in the collapse of white resistance to the National Party regime.

Two years previously Verwoerd spoke in the Pietermaritzburg city hall, and he had to be brought into town by a back route to avoid student demonstrators on the main road. During the meeting sacks of flour were dropped on to the platform, and most of the audience were rowdy and heckling the speakers. The Nat supporters were a minority (I was not there, but read about it in press cuttings). At the 1963 meeting with Vorster, described above, the Nat supporters were in the majority, and there were only about 30 vociferous opponents, mostly students.

In 1965 Verwoerd spoke again. It was just after Smith’s UDI in Rhodesia, so the local and foreign press were there in force to hear what he said about it. He said nothing about it, but confined himself to making attacks on the United Party, the official (and ineffectual) parliamentary opposition. All he said about Rhodesia was that South Africa did not believe in interfering the the affairs of other countries, and that that was a matter for Rhodesia and Britain to sort out. And there was no heckling, no vociferous opposition. It was clear that, on the whole, white opposition to the NP had collapsed between 1961 and 1965. Before the meeting many of the audience were singing pro-Smith songs.

But, to get back to the Sabotage Bill, it was ds. Cruywagen’s statement that anyone who did not support the Sabotage Act did not believe in the fall of man that got me thinking and converted me to liberalism.

I had been persuaded by a friend to join the Progressive Party, and worked for that party during the 1961 election campaign, and the MP for our constituency, Houghton, was the only one to be elected. That was Helen Suzman, who for the next 13 years was the only voice in South Africa’s parliament who seriously opposed the National Party’s totalitarian legislation. But I was not very happy about the Progressive Party’s franchise policy. Under the National Party the franchise policy was was based on race — all whites, and only whites, could vote for parliament (coloured voters had been moved to a separate roll in 1956, and black voters had been removed entirely in 1960. The black voters had been allowed to vote for white representatives — two communists and a Liberal). The Progressive Party proposed to move the qualification from race to class. The rich and educated of all races could vote.

Dominee Cruywagen said that anyone who did not support the Sabotage Bill did not believe in the fall of man. The logic of that escaped me. The Bible said “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom 3:23). To my mind, “all” included Vorster and and the police force. So it seemed to me that anyone who supported the Sabotage Bill must believe in the immaculate conception of Balthazar Johannes Vorster.

And by the same reasoning, the Liberal Party policy of “one man, one vote” seemed much better than the Progressive Party policy of votes for the rich and educated. If all have sinned, then no one is inherently more fit to rule than anyone else, and certainly not on the basis of skin colour, wealth or education.

So today I thank Dominee Cruywagen who, though it was not intention, put me on the path of liberalism, and helped to turn me into what Vorster would have called “a little pink liberalist.”

So I’m a pinko liberal, and proud of it.

_____

Tales from Dystopia is a series of blog posts I am writing on memories of the apartheid era. You can see a list of the other posts here.

Notes and references

1. Kragdadigheid is an Afrikaans word that is difficult to translate into English. Literally it means “mighty-deededness”, and in Vorster’s case the mighty deeds including the passing of redundant legislation as a tool of public relations.

2. At that period I wrote my diary in the Shaw alphabet, partly in order to learn it. It allowed one to represent several more English vowel sounds than the Roman alphabet. It never caught on. It was similar to shorthand in that many of the letters were s single stroke of the pen, and it took about a third less space on a page than the Latin alphabet.

3. Nusas: the National Union of South African Students

4. Frankie Waring was the Minister of Information.

5. Albert Luthuli was then president of the African National Congress (ANC). The ANC, and Luthuli himself, were then banned.

6. Maeder (Sammy) Osler was then President of the university SRC, and later President of Nusas. He was also a very fit rugby player.

7. The one who shouted the question was Saul Bastomsky, a classics lecturer at the university, who was himself banned about two years later. In reply to what the chairman of the meeting had said, “You weren’t even born then”, someone else shouted, yes he was, he was six years old.

Ascension Vespers in Midrand

Last night I went to Ascension Vespers and Litiya at St Sergius of Radonezh Russian parish in Midrand, where His Beatitude Theodoros, Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa served. His Eminence Damaskinos, Archbishop of Johannesburg and Pretoria, was present, together with a visiting bishop from Ghana. Several of the clergy of the Archdiocese of Johannesburg and Pretoria were present also present.

Priests at St Sergius of Radonezh Russian Orthodox Church for Vespers of the Ascension

The Pope was visiting southern Africa for the centenary of the Hellenic Community of Johannesburg, and also for the installation of a new bishop of Botswana (Orthodox Christians in Botswana were formerly under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Zimbabwe).

His Beatitude Theodoros, Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa, officiating at the Litiya

The Vespers included the Litiya, the blessing of five loaves, wheat, wine and oil, at which the Patriarch officiated, assisted by the parish priest, Fr Daniel.

Among the clergy present were Fr George Coconas and Fr George Cocotas (both Greek South Africans), Fr Pantelejmon (Serbian) and Fr Yonko (Bulgarian).

There were also ambassadors of several different countries present at the service, and the Patriarch greeted them afterwards. Among them were the Russian and Egyptian ambassadors, and several other countries were also represented.

The Patriarch greeting ambassaors who attended the Ascension Vespers

Afterwards there was a splendid feast in the church hall, with many toasts and much singing of “Many years”.

Patriarch Theodoros, with the Archbishops of Johannesburg and Ghana on his right and left respectively.

For anyone who reads this who is not Orthodox or South African, some of the significance of it may need to be explained.

The Orthodox Church was planted in Africa in Alexandria in Egypt in the first century by St Mark, who was a disciple of St Peter. Initially Christianity spread mainly among Jewish residents of Alexandria, and then gradually spread among Greeks and the local Egyptian population. By the end of the second century scriptures and liturgical texts had been translated into various local languages, and in the 3rd century it spread rapidly among the Egyptians, so that new bishoprics were created outside Alexandria, and the bishop of Alexandria (the original bishopric) became known as Pope, the father of the other bishops. This was long before the Bishop of Rome took the title Pope.

In the 7th century there was a split over a doctrinal question that had been decided at the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451, and those who accepted the Council of Chalcedon are known as “Greek” or “Eastern” Orthodox, while those who rejected it are known as “Coptic” or “Oriental” Orthodox. The Coptic Pope, Shenouda, died recently, as was reported in the news media, but Pope Theodoros is not his successor.

In South Africa Orthodoxy was established by immigrants, mostly Greeks, but also from Russia, Bulgaria, Romania and so on. But while there are parishes in which those languages are used (St Sergius in Midrand is Russian) they are one Orthodox Church, as was shown on this occasion by clergy of many different ethnic backgrounds being present, and also by the presence of ambassadors representing the various home countries. In places like North America, Orthodox Christians tend to be divided up into different ethnic “jurisdictions”, but this is not so in southern Africa, which has tried to avoid American “jurisdictionalism”.

May 23, 2012

Leavetaking of Pascha

Today, May 23, 2012, is the Feast of the Leavetaking of Pascha, and the Forefeast of the Ascension. It’s the last time we sing the Paschal Hymns until next year, and Paschal Matins is a repeat of the Easter Vigil service.

Yhis year was special, because it coincided with the visit of the Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria, Theodoros Ii, and so all the clergy were asked to meet him in the Archbishop’s Chapel in Johannesburg.

Leavetaking of Pascha in the Archbishop’s Chapel 23 May 2012

Patriarch Theodoros spoke at the end of the Divine Liturgy, and Archbishop Damaskinos of Johannesburg also had something to say.

His Beatitude Theodoros, Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and All Africa.

So we sang his Fimi:

His Beatitude Theodoros

Most Divine and Most Holy

Our Father and Shepherd, Pope and Patriarch

Of the Great City of Alexandria

Of Libya, Pentapolis and Ethiopiza

Of all the land of Egypt and all Africa

Father of Fathers, Shepherd of Shepherd

Bishop of Bishops, Thirteenth in line of the Apostles

And Judge of the Universe, Many Years!

Archbishop Damaskinos of Johannesburg and Pretoria addressing the clergy in the Presence of the Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa, Leavetaking of Pascha, 2012

After the Liturgy and the addresses, we were all given Easter eggs and had a nosh up in the Archbishop’s office.

I put my Easter egg in my pocket, and when I got home it had broken, and I had to clean it off my cell phone — just as well it was one of those that closes. I can’t think the keys would have worked too well if raw egg had gone all over them.

But that is the first time I have ever enountered a raw Easter egg. Usually they are hardboiled. But the phone still worked — the top photo above was taken with it.

May 21, 2012

The ups and downs of blogging

This blog, Khanya, using WordPress, has for several years been at least twice as popular as my other blog, Notes from underground, running on the Blogger platform.

In the last week, however, Notes from underground seems to have made a huge attempt to catch up, and, for the first time ever, instead of the majority of readers being in the USA, most of them have come from, of all places, Ukraine.

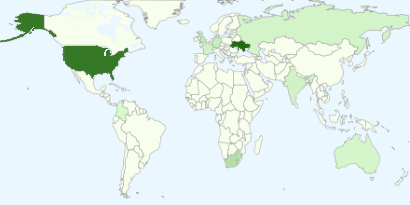

The map of where people came from looked like this:

And that in a week in which I wrote an article (on Notes from underground) that was highly critical of Blogger’s new and degraded interface, and lauding its old and improved one. Well, perhaps not in spite of, but because of, since lots of Blogger users are very disgruntled about about the new Blogger interface, and I predict that it will lead to another large migration of Blogger users to WordPress, in spite of the fact that WordPress has also chosen to ignore the “if it aint broke don’t fix it” rule.

But that too is not an adequate explanation, since that is not the most popular article.

The most-read article is one about Cosatu and the DA brawling in the streets of Joburg, and I wonder what about that might exercise such an attraction of readers from Ukraine.

It’s a strange, strange world we live in, Master Jack.

May 20, 2012

Missional or missionary?

I’m still reading about the Missional Church, which to some extent seems to have replaced the Emerging Church, so it seems that the term has emerged (sorry!) from the same circles, or at least that the circles overlapped, or used to.

What I haven’t managed to discover, however, is how the “missional church” differs from what used to be called the “missionary church”. So I’m hoping that someone, perhaps more than one someone, who knows the difference, will read this, and explain the difference for me.

Of course someone might ask what I understand by “missionary church” and that is not all that easy to explain. Someone once asked what the church is doing when it isn’t sitting in its pews, and I think that’s getting closer. Except, of course, that I don’t think proper churches have pews in the first place, and that the presence of pews is a prima facie symptom of a sedentary church, which is pretty well the opposite of a missionary church.

So the difference is in part the difference between the gathered church and the scattered church.

A friend of mine, John Davies, a retired Anglican bishop now working in Wales, observed that

In England - and in Wales - if you ask a priest how many people are in the parish, the reply will be something like ’15,000 people’ - the population of the area. In USA, Canada, and in much of S Africa, the reply will be something more like ’70 families’ - i.e. the number on the church roll.

That was something I noticed when I was studying in the UK 45 years ago, and that way of seeing things made me think that the Church of England, back then, was not a missionary church, because it would regard the 15000 people as part of its pastoral responsibility, or at least the pastoral responsibility of the parish priest. The parish priest was the “curate” (or “curator”), having the “cure of souls” of all those living within the parish boundaries. And back in those days part of the pastoral responsibility of the parish priest was to pay pastoral visits on all those 15000 people. “A house-going parson means a churchgoing people”, they used to say.

And this way of looking at things made me think that the Church of England failed to distinguish between pastoral and missionary work.

It seemed to me back then that a missionary church would see the 15000 as the mission field of that parish, and the 70 families as the mission team. And part of the job of the parish priest would be to train and equip the mission team.

That’s not all there is to it, of course, but that can give a rough idea of what I understand by a missionary church. And seeing it in that way was one of the reasons I opted to major in missiology rather than in pastoral (or “practical”) theology.

So my question is, how does the “missional church” differ from that?

May 18, 2012

Apartheid and racism in children’s literature

Apartheid and Racism in South African Children’s Literature, 1985-1995 by Donnarae MacCann

Apartheid and Racism in South African Children’s Literature, 1985-1995 by Donnarae MacCann

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

This book, as the title suggests, is an examination of children’s literature published in South Africa between 1985 and 1995, and consists for the most part of a series of book reviews.

The problem is that I haven’t read most of the books that it reviews, so this is not really a book review, but rather some thoughts on the subject matter of the book. I’ve only read one book that it covers, and that is Witch woman on the Hogsback by Carolyn Parker.

So if it deals with books that I haven’t read, why did I bother to read it?

The main reason is that I myself have tried writing a children’s books set in the apartheid period, which thus deals with apartheid and racism. So I was curious to see what the authors said about the topic, and I’m interested in the topic generally.

The book is harshly critical of most of the books it reviews, and not having read most of the books, I’m not really in a position to judge how valid the criticisms are. There is an epilogue dealing with two books that come in for praise: Let it come back by Karen Press and Chain of fire by Beverley Naidoo.

The authors of Apartheid and racism in children’s literature are American, and I found this a little off-putting. Sometimes it appeared from what they had written that they had very little first-hand experience of how apartheid actually worked. Actually very few South Africans could claim to know how apartheid actually worked, because even those who lived through the entire period could only experience a tiny fraction of what was going on, and thus their perceptions were fragmentary. In addition, of course, the education system was designed to brainwash people into accepting the system as normal, and to that extent the American authors, coming from outside, will have a different perspective, which can be useful. Someone once likened this to someone walking into a smoke-filled room, where all the windows are closed and lots of people are smoking pipes and cigarettes and cigars. And the newcomer says, “Wow, it’s stuffy in here, why don’t you open the windows?” And someone in the room responds, “What do you know about it? You’ve just walked in.”

So an outside perspective can be useful, but also has its own shortcomings.

I found the best part of the book was the final chapter and the epilogue, where the authors give positive reviews of books they thought were good.

The authors say (p. 117):

When our literary critiques point to political and economic information, this is not to imply that the narrative should incorporate fact-laden material, but only that the novel should not distort it for white supremacist purposes. So how do the novelists cover the socio-political backgrounds they introduce? In a word, even in the post-1994 noverls, Blacks are portrayed as essentially unready for self-rule.

I was glad to read that at the end, because when reading their reviews of the books, it seemed that one of their main criticisms was that the authors had failed to include fact-laden material, and I was thinking that nothing could be more boring for children than filling the book with statistics.

The authors criticise some books for portraying children growing up in a situation of urban gangsterism, and say that this implies that all blacks are gangsters, or at least prone to gangsterism. Not having read the book, I don’t know, and I don’t really like reading such “urban realist” books, even when they are written for adults (I recall reading one, set in America, called Last exit to Brooklyn). One thing that does strike me about that, though, is that most of the authors are white, and I wonder how they can write about black children growing up in such a society when the white authors would be largely insulated from it by apartheid.

And that makes me think about my own attempts at writing children’s books.

My book is set in 1964, which was at the height of apartheid, before any of the architects of apartheid had expressed even the slightest doubt about the rightness of what they were doing and the kind of society they were trying to create. And part of my aim in writing was so that children of future generations could have some kind of an inkling of what it was actually like. Teenagers in the late 1990s had very little idea, and were already growing up in a different world.

But I’m white, and in the apartheid years it was difficult enough for white people to meet and get to know black adults, much less children. When adults write books for children, they must write about children they know, and much of it must be based on their own experience as children. And as a child, and even as an adult, I did not really encounter black children. The black people I encountered were adults. It was not until the late 1990s that I had much to do with black children and teenagers, and that was after apartheid, and so their experience was different.

So when I tried to write a novel about children in 1964, most of the viewpoint characters are white. And that means that if any children were ever to read the book, white children would probably be able to identify more easily with the viewpoint characters than black children. And there are some features of apartheid life that are described in the book, without being questioned. I suspect that McCann and Maddy might interpret this as approval of the system, and in a sense upholding it.

For example, at one point in my story the four children who are the main characters have to catch a train. Three of the children are white, and one is black, and they have to separate to travel in different coaches. Now at such a point it might be possible to have the children discuss the evil of segregation in public transport, but I don’t think that would be child-like behaviour. For children it is just one of the things that they have to live with an an adult-controlled world, and that they have to deal with as best they can. And for child readers in later periods, it can inform them that there was segregation in public transport back in those days, and when it caused problems to children, they did not question it, but found ways of getting around it.

But when children encountered manifest injustice, such as forced removals, they often did question it, because children tend to have a quite well-developed sense of what is fair and not fair. The problem for white children in that period was that they were generally insulated from it, by upbringing, education and laws like the Group Areas Act. So in trying to write a children’s novel about the period, one has to contrive a way of overcoming those barriers that doesn’t make the narrative contrived, artificial and so unconvincing.

McCann and Maddy criticise many of the novels they discuss because the contact between black and white children is in the context of the master-servant relationship. In a friendship between a black child and a white child, the white child’s parents are usually the employers of the parents of the black child, and that usually makes the relationship unequal from the start. I think it is a valid criticism, but how does one overcome it?

In my own story I tried to do this by making the black child the eldest of the four, and also the one most directly affected by the problem at hand, which is to warn his father, who has been banished to a far part of the country, that the police are plotting to have him killed.

But in trying to write this story, I realise that I was writing more for white children than for black children, and that part of the aim was to question the tendency of some whites to think that “apartheid was not so bad” and to pass on that attitude to their children.

Another aim might clash more directly with MacCann and Maddy, who are also critical of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Desmond Tutu’s Christian approach to forgiveness. They criticise religion generally, and Christianity in particular, for aiding and abetting apartheid. But they also criticise it for its tendency to forgive and not vindictively punish the perpetrators.

It has been said that where apartheid is concerned, in the notion of “forgive and forget”, it is blacks who do the forgiving and whites who do the forgetting. Part of the aim of my story was to counter the latter — the present may not be perfect, but we should not forget the darkness from which we have come. But what about the forgiveness part?

In the 1980s there was much talk, especially among white Christians, about “reconciliation”. Black Christians were more likely to talk about “justice”. Several Christian denominations at that time had departments of “Justice and Reconciliation”, which was a kind of compromise, but very little thought seems to have been given to what such departments ought to do, or about the relationship between justice and reconciliation, or about why Christians ought to be concerned about either justice or reconciliation. Most of those departments spent most of their time in ad hoc responses to various crises, of which there were plenty in those days, what with states of emergency, troops in the townships, assassinations and the “third force”.

There was also a “National Initiative for Reconciliation”, which I am sure was well-intentioned, though I think that those who started it did not perhaps give enough thought to the theological implications of the name, for I had read a book called Up to our steeples in politics that pointed out that the one who takes the initiative in reconciliation is God, and that human attempts to reconcile people usually go awry. In addition to which, it seemed to me that most white peoples’ idea of “reconciliation” was a matter of reconciling black people to living under apartheid. What reconciliations should mean is that people who were at enmity turn from hating to loving, but as used by many in South Africa in the 1980s it would have meant trying to reconcile good and evil.

But even with all that in mind, when MacCann and Maddy say that “Tutu and the majority of the [Truth and Reconciliation] Commissioners were in line with the ‘confess and repent’ approach to truth finding. Unfortunately the world at large offered few rebuttals, unlike its reaction to ‘ethnic cleansing’ in the Balkans, Pinochet-led assassination practices, and other grave human rtights cases” I get the impression that they think that “a more excellent way” would have been an Operation Highveld Storm, involving the carpet bombing of South Africa’s cities and destruction of the infrastructure, as Nato did to Yugoslavia in 1999, and Israel did to Lebanon in 2006, rather than what St Paul had in mind in I Corinthians 13.

And that is where I finally part ways with the outlook of MacCann and Maddy. I think the Balkans would have been a lot better off with a touch of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission than with the vindictive “justice” meted out by all parties on their perceived enemies. But I’ve already written about that here: Nationalism, violence and reconciliation, so enough already.

Heart of darkness (book review)

Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This is a difficult book to review without revealing too much of the plot to those who have not read it. Like several of Conrad’s books, it is a story within a story, a narration within a narration. Five sailors in a boat on the Thames settle down for the evening and the narrator describes how one of the others, Charles Marlow, tells a story about his experience on another river at another time.

Neither the unnamed first narrator, nor Marlow, the second narrator, is the protagonist. That role belongs to a man called Kurtz, who only gradually makes his appearance. Through his aunt who knows someone who knows someone, Marlow got a job as captain of a river steamer on a big river. He travels to an unnamed country for his job interview, and the office is guarded by two women in black, symbolising the growing darkness. And to take up his employment he travels on a French ship to an unnamed country with an unnamed big river. But it is clearly the Congo Free State, then being conquered by a Belgian company, whose white employees Marlowe describes as faithless pilgims, worshipping the ivory they extract from the country.

The greatest white employee of the company is Kurtz, who gets more ivory than anyone else. But Kurtz, it is said, is ill, and must be relieved. His station, however, is at the furthest point up the river, and before they can set out the boat must be repaired. Eventually they set out upriver, Marlow accompanied by black cannibal woodcutters, who cut the wood to fuel the boat, and the white pilgrims. As the river narrows and the forested banks get closer, Marlow feels he is sailing in to the heart of darkness.

I’ll say no more of the story, for fear of revealing too much of the plot, but will add that when I reached the end of the book, I went straight back to the beginning again, and started reading it again, because there are some things about the beginning that one does not really appreciate until the end. It begins at sunset, with the Thames being a river that ships sail down to all parts of the world, and as the dark settles over the river, it too becomes he heart of darkness, and the Roman legionaries that sailed up it thousands of years before must have experienced it rather similarly to Marlow’s experience on the big river.

When Marlow was a boy he looked at the big river on the map, and it looked like a snake. And the area on the map was white, because it was terra incognita to the mapmakers, but as the employees of the company travelled along it to exploit its resources, it darkened. And as Marlow travels up the river, he is alienated from both the white “pilgrims” and the black cannibals. He knows enough of them to predict their behaviour in certain circustances, and tries to avoid what he sees as the worst of it, but he feels unable to even try to penetrate their behaviour and attitudes, and discover the human beings behind it.

At some points one feels that Marlow is very much the detached observer, describing others with little empathy, but on looking as bit more deeply, one sees this is not the case, but Marlow is in a sense cut off by not being able to understand what makes others tick, and what he does see doesn’t seem attractive enough to him to make him want to learn more.

I think I’d probably have to read it ten times to review it adequately. I suspect it is the kind of book where one would find something new every time one reads it.

May 16, 2012

Liturgy, worship and digital doodads

A couple of weeks ago (that’s the ages of ages in blogging time) blogger Bosco Peters asked a question about the use of digital gadgetry, and especially projectors and screens, as aids to worship.

In a post with the title Luddite liturgy he writes Projector screens in church:

Recently I was in the congregation at a service where there were two large screens diagonally in the corners for the congregation, and one more facing the leadership in the stage/chancel/sanctuary area. And it was death by PowerPoint. Screens and PowerPoint may still feel “with it” for the oldies that dominate and lead – but it’s over two decades old now. Young people have not known a world in which it didn’t exist. Even the concept of “death by PowerPoint” is an issue realised more than a decade ago.

Sure, there’s possibly ways of incorporating digital images and contemporary technology etc. into worship. But let’s look at just a few issues that leaped out merely at this one service.

On reading that I was reminded of the occasion, a few years ago, when some Emerging Church people visited our parish (St Nicholas of Japan Orthodox Church, Brixton, Johannesburg) for Vespers. At tea after the service the visitors were invited to ask questions or make comments about the service they had just participated in, and one of them remarked that there was “nothing digital”.

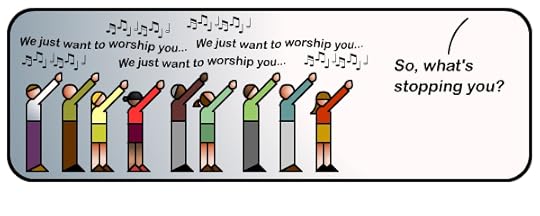

I’d seen Protestant worship where projectors and screens were used for worship, though on occasion I had failed to recognise it as worship. At the Amahoro Conference a few years ago there was “worship” on the programme, so I wandered into the hall where a band was practising some songs, and I hung around waiting for the worship to begin, but eventually the band packed up their instruments, moved off the stage and made way for the next speaker. It turned out that what I had taken to be the band practising was the “worship”.

From The ongoing adventures of ASBO Jesus (ASBO in Britain stands for “Anti-social Behaviour Order“)

Some of the comments in Bosco Peters’s post were also interesting. One remarked that they were still back in the stone age, using an overhead projector with transparencies rather than a digital projector with PowerPoint. But it seemed to me that the main point was being missed — whether projecting stuff onto screens in that manner is appropriate for worship at all. Overhead projectors, or digital projectors, it doesn’t matter. Both were designed primarily as educational tools, not as aids to worship.

Now Bosco Peters is Anglican, and there is a longstanding Anglican tradition, going back to the compilers of A Book of Common Prayer and possibly before, that sees edification as an important (if not the most important) component of worship. I discovered that from having had to write an essay, and answer an exam question on edification as part of worship in the Anglican college I attended.

The penny dropped when, during one of the college vacations, I hopped overt to Switzerland for a two-week course on “Orthodox theology and worship for non-Orthodox theological students”. There was a large contingent of East German students at the course (that was during the Cold War, in 1968). They were Lutherans, and suffered from culture shock. During a break between lectures one of them was emphatically asking “But what about the WORD?” We were standing by the chapel and I looked in and saw the ikon of Christ looking at me, and it suddenly clicked. He is “The Word”. He is the Wisdom, Word and Power of God.

I tried to explain that, but the Lutherans were unconvinced.

We moved on to St Sergius Seminary in Paris and shared Holy Week and Pascha with the students and congregation there, and when I returned to college I knew how it was that Anglican services had such a strong element of edification. After Orthodox worship they seemed excessively didactic, and Reformed services even more so.

So it may seem entirely appropriate for Anglicans to have screens all over their churches. But Bosco Peters still has doubts, as he makes clear when he says Projector screens in church:

We’ve recently been discussing, here, the projecting of the texts of readings onto a screen. Can someone please tell me when they were last at a play where the words of the play were projected onto a screen? Or is the general expectation at a play that the quality of the proclamation is sufficient? Do we have a lesser expectation at services?

Plays are not really edification, but entertainment, and so we are getting closer to the more Protestant end of things, the so-called “non-liturgical churches”, where worship tends to become confused with entertainment. But in the comments on Bosco Peters’s post too, this is not far below the surface, when some commenters wrote about “the worship experience”.

I’ve been there and done that too.

Partly inspired by the experience of Orthodox worship, I took part in planning and running a “psychedelic service” that got me fired as an Anglican deacon (if you’re interested in the details you can find them here: Notes from underground: Psychedelic Christian Worship — thecages). We were didactic even we were trying to get away from the didacticism of Anglican worship, and it was undoubtedly a learning experience, and one of the things I learned was that what we were trying to do was to organise a “worship experience” for people and that the essential ingedient was missing — that is, worship itself.

So Bosco Peters concluded that

…liturgy degenerated from powerful symbolic actions accompanied by interpretive words to hundreds of people staring at screens of words in the corners of the worship space…

When it comes to liturgy – I’m mostly a Luddite.

It seems to me that the use of this digital gadgetry is essentially incompatible with liturgy. Liturgy is “the work of the people”.

As Ugolnik (1990:138) puts it

Liturgics enacts a representation of reality, embedded within a text, and seeks to impose its framework of meaning upon a resistant world. It is not, in essence, an ‘alternative reality,’ representative of a world in which it is contained – in the way, say, Middlemarch is a fictional representation of a provincial English town. Liturgics seeks to impose the textual vision upon a resistant world, and make the world conform to it. There is a phenomenon of inversion which is very important to a Russian Orthodox sense of liturgy; liturgy is in itself a kind of ‘revolutionary’ act. In this way Alexander Schmemann sees the liturgy as enacting or celebrating the Kingdom of God, a spiritual kingdom of justice and liberation, within a world which does not accept it.

And as Fr Alexander Schmemann (1983:25-26) himself has said:

The Eucharist is a liturgy. And he who says liturgy today is likely to get involved in a controversy. For to some — the “liturgically minded” — of all the activities of the Church, liturgy is the most important, if not the only one. To others, liturgy is an esthetic and and spiritual deviation from the real task of the Church. There exist today “liturgical” and “non-liturgical” churches and Christians. But this controversy is unnecessary for it has its roots in one basic misunderstanding– the “liturgical” understanding of the liturgy. This is the reduction of the liturgy to “cultic” categories, its definition as a sacred act of worship, different as such not only from the “profane” area of life, but even from all other activities of the Church itself. But this is not the original meaning of the Greek word leitourgia. It meant an action by which a group of people become something corporately which they had not been as a mere collection of individuals — a whole greater than the sum of its parts. It meant also a function or “ministry” of a man or of a group on behalf of and in the interest of the whole community. Thus the leitourgia of ancient Israel was the corporate work of a chosen few to prepare the world for the coming of the Messiah. And in this very act of preparation they became what they were called to be, the Israel of God, the chosen instrument of His purpose.

Thus the Church itself is a leiturgia, a ministry, a calling to act in this world after the fashion of Christ, to bear testimony to Him and His kingdom. The eucharistic liturgy, therefore, must not be approached and understood in “liturgical” or “cultic” terms alone. Just as Christianity can — and must — be considered the end of religion, so the Christian liturgy in general, and the Eucharist in particular, are indeed the end of cult, of the sacred and religious act isolated from, and opposed to, the “profane” life of the community. The first condition for the understanding of liturgy is to forget about any specific “liturgical piety”

When a gathering of people are looking at a screen, they are not doing something together; they are rather passive recipients of something being done to them. It ceases to be liturgy and becomes manipulation, driven by the people managing the equipment. “Let us pray to the Lord: next slide”.

And when I try to think of this in the context of Orthodox worship, the incompatibility becomes obvious, for where can you put a screen in an Orthodox Church where it will not obscure some of the ikons?

Putting a screen in front of the ikons is replacing something having a deep, abiding and powerful symbolism with something superficial, banal and ephemeral.

But it is more. It breaks the community of the church.

Putting a screen in front of the ikons not only hides the ikons from the congregation, but it symbolically hides the congregation from the view of the saints depicted in the ikons. We are surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses, except for those we have chosen to exclude in favour of our own more ephemeral and self-centred concerns, our “worship experience”.

Orthodox Churches in Muslim countries are sometimes vandalised, because Muslims are iconoclasts. But they don’t usually vandalise the whole ikon, they just chisel out the eyes. And by putting a screen in front of the ikons we would in effect be doing the same thing.

If you can understand this, you may able to know something of the difference between the Orthodox Christian view of worship, and that of most Western Christians, certainly most Protestants.

May 5, 2012

Orthodox Christianity and fantasy literature

An interesting discussion seems to be developing in the Orthodox blogosphere about whether Orthodox Christians should write, or even read, fantasy literature. They are referring to the works of writers like C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien — Christian (though not Orthodox) authors who wrote fantasy fiction.

The answer of this blogger, Lily Parascheva Rowe, seems to be that fantasy literature is a definite No-No for Orthodox Christians: Is it Orthodox to Read and Write Allegory/Fantasy Children’s Books?:

Fantasy, on the other hand, is a pure expression of the passions. Basically it’s whatever the mind imagines ends up on paper. So then we end up with werewolves and vampires and a celebration of evil that in the modern genre completely lacks what the original characters were intended to portray. In this way, a genre that was meant to lead someone toward Christ now pulls them in the opposite direction by tantalizing every wicked fantasy and passion imaginable, and infusing it with a lustful voyeurism so that people constantly want more and more perverse and graphic fantasies. The other thing I notice about fantasy vs allegory is that modern fantasy generally has some sort of romantic involvement of the characters. This would be fine except for the fact that the romantic involvement doesn’t reflect Christ’s relationship with the Church or anything like a Christian marriage. Often, it could even be described as downright pornographic.

But Fr Andrew Stephen Damick disagrees Orthodoxy, Allegory and Fantasy | Roads from Emmaus:

Phantasia is a danger in ascetical writings not because it uses the imagination. Rather, it is a use of the imagination that fixates the heart on created things. More specifically, it is a fixation that is an obstacle to the pure prayer of the heart. In pursuing meditative prayer, the ascetic (who is not just the monastic, but all of us) is called upon not to try to imagine God, to picture Him, or to become obsessed with any created image in order to reach Him, because doing so is essentially idolatry. It is also simply prejudicial, just like relating to any human person by means of imagination rather than through encounter.

But fantasy (even the specific literary genre that goes by that name) isn’t about prejudicial obsessions with created things that block us off from God. If imagination qua imagination were only phantasia in the sense that the monastic fathers warn us of, then many of the great Fathers of the Church would be in rather deep trouble, for a good many of them had rather thorough educations in fiction—even in explicitly pagan literature.

Like Fr Andrew I would take issue with Rowe on the question of allegory, and especially the notion that allegory is good, and fantasy is bad. The writings of the church fathers are full of allegory, and many of them interpret the holy scriptures allegorically, but I think it is questionable whether writers like C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien used allegory, even in their fantasy stories.

One can find examples of phantasia in literature. One fairly well-known example is Scott Fitzgerald’s The great Gatsby, where a central theme is the image one has of a person superseding the reality until it becomes an idol, and almost totally unrelated to the real person. It is this, as Fr Andrew points out, that is the kind of phantasia that the fathers wrote about as being one of the passions we should aim to bring under control. But The great Gatsby is not fantasy literature, nor is it allegory.

If we want to see true allegory in 20th-century literature, possibly the best example is George Orwell’s Animal Farm. It is fantasy literature too, in the sense that the situation it depicts does not literally form part of our experience of the real world. Animals don’t run farms in the world of everyday experience, but it is allegory in the correspondence of characters and events with historical events in our world.

In the works of Tolkien and Lewis (and one might as well include the novels of Charles Williams in this too) there isn’t such a correspondence. Of course all their works are illuminated by the Christian values of the authors, and the death of Aslan in Narnia in The lion, the witch and the wardrobe has some parallels with the crucifixion of Christ in our world, but it is not an allegory of it. It would be very difficult to find the allegorical counterpart of the witch in that story in our world. It is easier to find counterparts of Maugrim the wolf, the chief of the witch’s secret police in our world, but it could be applied to any head of any secret police in any country. Maugrim does not, for example, represent Heinrich Himmler, the head of the Nazi Gestapo, for instance, as true allegory would require, even if Lewis had some of his police in mind as models. It could equally well represent OGPU, or the KGB, or the South African Security Police of the apartheid era. I sometimes used to refer to them as “Maugrim” in letters to friends back them, and I wonder whether their functionary whose job it was to steam open the letters of suspected subversives understood the reference. But Maugrim was not an allegory for Himmler or Beria or even Warrant Officer Van Resnburg of the Pietermaritzburg SB.

C.S. Lewis himself had some interesting things to say about allegory (and as a professor of literature I think he probably knew what he was talking about). He wrote to Tolkien on 7 December 1929, after reading Tolkien’s poem on Beren and Luthien, “The two things that come out clearly are the sense of reality in the background and the mythical value: the essence of a myth being that it should have no taint of allegory to the maker and yet should suggest incipient allegories to the reader.”

So perhaps we should not be talking about “allegory” or “fantasy”, but rather about “myth”.

Lewis and Tolkien, and probably Williams too, were not so much interested in writing allegory, or even fantasy, but rather at writing Christian myths. And of myth Nicolas Berdyaev has said:

Myth is a reality immeasurably greater than concept. It is high time that we stopped identifying myth with invention, with the illusions of primitive mentality, and with anything, in fact, which is essentially opposed to reality… The creation of myths among peoples denotes a real spiritual life, more real indeed than that of abstract concepts and rational thought. Myth is always concrete and expresses life better than abstract thought can do; its nature is bound up with that of symbol. Myth is the concrete recital of events and original phenomena of the spiritual life symbolized in the natural world, which has engraved itself on the language memory and creative energy of the people… it brings two worlds together symbolically (Berdyaev, Freedom and the Spirit).

I think that these two blog posts, that of Lily Parascheva Rowe and of Fr Andrew Stephen Damick, could spark off an interesting discussion on the literary genres — fantasy, allegory, myth — and the Christian faith. Blog comments can help, but are rather limited, and comments on one blog may be missed by readers of the other, so for more flexible discussion I suggest the Neoinklings discussion forum be used. You can find more information about it and how you can join if you click here: NeoInklings Forum (Eldil).