Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 68

July 25, 2012

KZN holiday 2012

We were on holiday in KwaZulu-Natal from 8-23 July, travelling around and visiting friends and family. Some of the family visits are described in our family blog here. This post consists mainly of miscellaneous notes and observations about places and people we visited and how things have changed.

We lived in Durban until 1976, and in Melmoth in Zululand from 1977-1982, and though we have visited several times since we lived there, this time we noticed quite a lot of changes.

One change is that we got lost a lot.

There are lots of new roads, and some of the old roads have new names, and the signposting is bad.

Actually that started when we were still in the Free State, and leaving Vereeniging we were looking for the road to Heilbron, and were halfway to Parys when we realised we must have missed it. The signs were there when we retraced our steps, but they were not there in the other direction. In Ermelo we were looking for the road to Bethal. A sign said straight on, so we drove straight on, until we came to a T junction with no sign. The old North Coast Road (R 102) has been widened and straightened, so I could no longer recognise the turn-off to Mount Edgecombe. It was signposted on the way in to Durban, but not when one was leaving.

Forty years ago I drove between Tollgate and Queensburgh at least four times a week, going along Cato Manor Road. There used to be a little tin temple at the side of the road, and I wondered what had happened to it. It was only when Val was driving and I was in the passenger seat that I looked out of the window and saw that, since the road had been widened and straightened, it was now on the other side of the road, on a little looped off section of the old road. It was looking bright with a coat of new paint, and we went down to have a look. There were couple of women preparing something outside, and they struck a pose when they saw we were taking photos. The tin temple was a familiar landmark, but it had changed position.

Shree Gengaiammen Temple, Cato Manor, Durban

It was also nearly forty years ago that I asked a guy at the bigger Umbilo Temple nearby about the little tin temple beside the road. He told us that it was built on an anthill, and under the anthill lived a five-headed cobra. A bowl of milk was put out for the cobra every night, and it always drank it.

Wherever we went the conversation seemed to turn to education, and I blogged about that in another post, The disaster that is education in South Africa, but the picture is not all gloomy. We visited my cousin Jenny Aitchison and her husband John (who was a close friend when I was a student in Pietermaritzburg). John is working for the Department of Education in the production of maths textbooks, and he showed us a textbook for Grade III, which was much better than anything I had had when I was at school, and more advanced too. The distribution system may be seriously flawed, but the books themselves are much better.

Val Hayes, John & Jenny Aitchison

When we got to Melmoth we drove past All Saints Church, which looked older and more weathered, and the trees surrounding it were bigger. The flat crown tree in the rectory garden was enormous, with branches now spreading over the roof of the house, and our Christmas tree of 30 years ago, which we had planted outside the study window, was huge, and had split into two tops. With all the trees the lawn seemed to have struggled to survive, and the front garden looked a bit like a sandy yard.

All Saints Anglican Church, Melmoth, KZN

I got out of the car to take pictures, and two black shoolgirls, aged about 10, politely said hello, as did a woman who was walking along the pavement, and there was a pavement, which had not been there in our day. Actually the road had recently been resurfaced, and there were now proper gutters too.

Hammar Street, Melmoth, KZN – looking much better than when we lived there 30 years ago

The people made the place seem friendly. I walked back to take photos of the church, and four more black schoolgirls came down the hill and walked along the pavement. One of them asked me if I was Father Christmas, and took a photo of me. I didn’t have the presence of mind to take a photo of them, and afterwards wished I had. I asked which school they went to and they said Melmoth Combined School, which was up the hill somewhere. I said that when we lived here the Melmoth Primary School had been at the end of the road. They were in Grades 6 and 7. I was struck by their manner and behaviour. They spoke good English. They were not too shy to speak to strangers, they were neither subservient, shy nor cheeky. They were friendly and confident. Though there are many thing wrong in South Africa, there most be something going right to produce kids like that. It seemed like a cultural fusion. In traditional Zulu culture children are taught to be polite and greet adults, but also to be self-effacing and shy. In Western culture children are sometimes rude and pushy, or ignore adults altogether. These kids seemed to manifest the best of both. A chance encounter in the street is perhaps not much to judge by, but it would have been quite unthinkable to encounter children like those in the streets of Melmoth 30 years ago.

Some people we met spoke of a generation gap.

Peter Houston

I’m still doing research into the charismatic renewal in South African Christianity, and spoke to Peter Houston, a young Anglican priest who recently became Rector of Umhlali (see his blog here). He had recently been to a conference of Anglicans Ablaze, which was a joint conference of several Anglican renewal organisations, including Iviyo loFakazi bakaKristu (the Legion of Christ’s Witnesses), New Wine and others, and noticed that the clergy whose ministry had been shaped by the charismatic renewal were now retired or approaching retirement age, and were concerned that the youth no longer seemed to be interested. Peter believed that the younger generation were looking for something different. Ben Aldous, a young Anglican priest in Durban North had a similar view, and is doing research into Fresh Expressions, an Anglican movement in the UK, to see if it would be relevant to southern African Christianity.

Hamilton Mbatha, with whom we had worked closely in Melmoth 30 years ago, said something similar. He is now rertired in Melmoth, but still active in speaking at Iviyo conferences, and he too spoke of a generation gap.

Hamilton and Thembani Mbatha, Melmoth, 23 July 2012

Another retired priest, Meshack Vilakazi, also living in Melmoth, spoke in similar terms, but he is active in doing something about it, visiting prisons and talking to young offenders, and trying to reconcile them to their families and encouraging the families to support them so that they would not return to crime on leaving prison.

The people who were most pleased to see us as we travelled around were our Zululand friends, and especially the black Anglican clergy of the Diocese of Zululand – Patrick Gumede, Theophilus Ngubane, Hamilton Mbatha and Meshack Vilakazi. They are all retired now (like me) but something of that spirit was seen in the schoolgirls we spoke to in the street. There was something special about Zululand. Hamilton was the Regional Dean of Mthonjaneni deanery, which included Melmoth and KwaMagwaza nearby, and we worked closely together there.

KwaNzimela Conference & Training Centre, KwaMagwaza, KZN. This part looks much as it did 30 years ago.

KwaMagwaza was also the home of KwaNzimela, the diocesan conference centre, where Theophilus Ngubane and I used to hold training meetings for self-supporting clergy, who gathered there once a month. It was also the venue for the diocesan Partners in Mission consultation in 1982, and I had worked with Meshack Vilakazi and Patrick Gumede to plan it. Visitors from other “partner” dioceses came and were taken on as tour of the diocese, and prepared a report on what they saw as mission strengths and weaknesses. They prepared a report which was discussed at the consultation, where there were clergy and lay representatives of all the parishes.

Ivor Shapiro, the editor of the (now defunct) Anglican newspaper Seek came to cover the conference for the paper, and after a couple of days he took me aside and said, “Am I missing something, or do these people really love one another?”

Meshack Vilakazi

He had recently reported on a synod in another diocese, and there when people disagreed during the sessions, at tea time they would meet in caucusing groups and plot how to gain support for their position, and weaken the opposing viewpoints. And that, he said, was typical of most diocesan gatherings he had witnessed.

But in Zululand, he noticed something different. People who had disagreed vociferously in one of the sessions would get together at tea, and would be the best of friends. Yes, there was something special about Zululand, and people really did love one another. And seeing people, some of whom we hadn’t seen for 30 years, reminded us of that. They were genuinely very pleased to see us.

While some things at KwaNzimela looked the same, there were also changes. The trees surrounding the buildings were much taller, and so there was not as much of a view over the Nkwalini valley as there had been in the past.

There was also a an enormous hall being built. Apparently it was a project of the Mothers Union, who had raised the money to build it. It will probably be able to hold all those attending large gatherings like the diocesan youth conferences, Iviyo conferences, and Mothers’ Union conferences, but when we looked at it we were reminded of nothing so much as the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, which seems to favour that style of architecture.

Mothers’ Union Hall at KwaNzimela

There were some new smaller buildings under construction too, one of them a library, though the collection of books seemed rather sadly depleted from what it was 30 years ago. One that I used to read, and could not find this time, was The mind and face of Bolshevism by Rene Fulop Muller. It must have been a rare book, as I could not find any reference to it in web searches. Perhaps it was the only copy in the world, but now it seems to have gone.

Another change was the “animal tree”, which our children used to climb and play in when we went to KwaNzimela, and they used to imagine all kinds of animals in its branches. It had grown to about three times the sisze that it was 30 years ago.

The Animal Tree at KwaNzimela, July 2012

July 16, 2012

New book on Orthodox political theology

I’ve just received an announcement, by e-mail, about a new book on Orthodox political theology, which looks interesting.

Unfortunately the essential bibliographical information seems to be missing — no ISBN, no web links, so sorry I can’t refer anyone to it.

Unfortunately the essential bibliographical information seems to be missing — no ISBN, no web links, so sorry I can’t refer anyone to it.

But here is what I received:

Panel Explores the Political Stance of Orthodox Christianity

To mark the launch of the series “Doxa & Praxis: Exploring Orthodox Theology”

On Wednesday, July 4, 2012, Dr Pantelis Kalaitzidis, Director of the Volos Academy for Theological Studies, participated in a panel discussion which considered, among other things, the question: Why has Eastern Orthodoxy not developed a full-throated political theology? Dr Kalaitzidis cited a host of historical reasons for what he argues is the muted voice of Orthodox Christianity in the political sphere, including its subsumption to a variety of autocratic regimes, from the Ottoman Empire to the Soviet Union, and its caution about Western modernism. Better known for its robust ecclesiology and rich doctrinal and liturgical identity, Orthodox Christianity now faces the need for a theological framework to address tumultuous social and political change.

Dr Kalaitzidis offered his spirited critique of Orthodox Christians’ approaches to political life and political theology at a book launch at the World Council of Churches (WCC) offices in Geneva, where a joint publishing series called “Doxa & Praxis: Exploring Orthodox Theology” was announced. The publishing agreement is between WCC Publications and the Volos Academy for Theological Studies.

Dr Kalaitzidis, editor of the series, introduced its first two publications, Orthodox Theology in the Twenty-First Century, by Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, and Kalaitzidis’s own Orthodoxy and Political Theology. Responding to his book were Dr Tamara Grdzelidze of the Faith & Order Commission, and Dr Odair Pedroso Mateus, of the Ecumenical Institute at Bossey and the Faith & Order Commission. Both are WCC staff members.

While Dr Grdzelidze largely concurred with Kalaitzidis’s analysis and theological perspective, particularly its eschatological orientation, she also drew attention, for her part, to the massive suffering of ordinary Christians under various regimes and the need to respect their limited options for public witness. Dr Mateus highlighted the theological tensions raised by contextual and political theology by recalling competing presentations by Eastern Orthodox theologian John Meyendorff and liberation theologian José Míguez Bonino in a 1971 Faith & Order meeting in Louvain. At the end of the discussion that followed these presentations, Mr. George Lemopoulos, Deputy General Secretary of the World Council of Churches, conveyed a message from the WCC General Secretary, the Rev. Olav Fykse Tveit, in which he expressed his appreciation for the fruitful and constructive cooperation between the WCC and the Volos Academy and the fruits of this collaboration, which includes, among other things, the publishing series just presented.

July 13, 2012

Friends old and new

We had a fairly busy day today, meeting old and new friends in Pietermaritzburg.

Patrick Gumede

We started the morning by going to visit Nkosinathi Ndwandwe, suffragan bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Natal. We went to the Cathedral of the Nativity in town, and in the car park met another old friend, Patrick Gumede, whom we had known in Zululand, where he had been a senior priest in the Anglican Church there, at Nkonjeni near Mahlabathini. He moved to Pietermaritzburg shortly after we moved to Pretoria, and we hadn’t seen him for 30 years. He is now retired, but is still helping with taking services in various places.

We went to see Bishop Nkosinathi, whom I also hadn’t seen for 30 years. I wanted to interview him for our research project on the Charismatic Renewal movement, as he has written a book on the IViyo lo Fakazi bakaKristu (the Legion of Witnesses for Christ), I hadn’t known him as well as Patrick Gumede, since he was away at college most of the time we ere in Zululand, as a student at the Federal Theological Seminary in Edendale.

Nkosinathi Ndwandwe, Bishop Suffragan of the Anglican Diocese of Natal.

Bishop Nkosinathi very generously gave us two hours of his time, and it helped us to catch up on some of the developments in Iviyoover the last 30 years, and it was very important, as it is clear that the charismatic renewal movement is not as moribund as it had seemed to be. The charismatic renewal movement in the Anglican Church started with Iviyo in Zululand in the 1950s, and has continued to spread since then. In the 1960s and 1970s it appeared among white and coloured Anglicans in South Africa, but in the 1980s it seemed to dissipate into factionalism and go into decline, but it continued to grow among black Anglicans through IViyo. Bishop Nkosinathi attributed this to the quinessentually Anglican nature of Iviyo.It was rooted in Anglicanism, and grew out of Anglicanism, and did not, like the charismatic renewal among whites, borrow heavily from Pentecostal sources and so IViyo did not become embroiled in controversies over things like infant baptism or Pentecostal pneumatology, which caused the shattering of the movement among whites in the 1980s, with many leaving to form or join Neopentecostal denominations.

We were then met in the cathedral car park by Michael Carstens, who came with us to show us the way to the Orthodox Church in Edendale, about 10 km to the west of Pietermaritzburg. Michael seemed to know so many of the same people that we knew that I was quite surprised that we hadn’t met before.

The Orthodox Church in Edendale was built, as far as I know, by our Bishop Damaskinos when he was a parish priest in Durban about 10-12 years ago, and is in the care of Reader Timothy Madlala, who attended the seminary in Nairobi. I had heard a lot about him (and the church) from other people, and so was pleased to meet him in person for the first time.

Michael Carstens, Reader Timothy Madlala & Val Hayes at Edendale, KZN

There is a house on the land, where Reader Timothy lives, and the church is built in the same style. There is also an outdoor baptistery, which can just be seen in the background of the picture above, with a cross-shaped font set into the ground.

Orthodox Church, Edendale, near Pietermaritzburg

Edendale has an interesting history. The land was bought and settled by black Methodists before the passing of the Natives Land Act of 1913 (which made it illegal for black people to buy land in “white” areas). But because it bordered on a black reserve, it was never expropriated by the apartheid government, and the people were never ethnically cleansed. It remained one of the few places where black people could own freehold land in South Africa right through the apartheid era.

While we were talking a group of young children came in and ran up and greeted us all with hugs and kisses. Michael Carstens remarked that such behaviour was very unEnglish, implying, I think that the hugging and kissing common in Orthodox culture was a little strange to the more reserved English-speaking cultures.

Reader Timothy with some of his young parishioners, 13 July 2012

I think it would also seem strange in traditional Zulu culture as well, where children do not rush to greet strangers, but rather keep in the background, and are still, in many households, expected to be “seen and not heard”. I took it as a sign that these children felt secure and loved, and at home in the church.

July 12, 2012

The disaster that is education in South Africa

The Limpopo school textbook scandal is only the tip of the iceberg. Eighteen years after the dawn of democracy there is still little sign of transformation of education in South Africa. Children who were born in 1994 should be completing high school this year, and are things any better for them?

We’ve been on holiday this week, visiting friends and family in various places in the Free State and KZN, and most of our conversations have been about the parlous state of South African education. Perhaps that’s because most of the people we have visited have been involved in education in one way or another, and so it was only natural that the conversation would turn to that, but I think it is more than that. I think lots of people are concerned about the failure of transformation.

We spent a couple of nights with my cousin Peter Badcock Walters, now retired at Clarens in the Free State. He spoko of preparing a model for educational development in the early 1990s for John Samuel, the ANC’s education fundi. The model analysed just about everry aspect of education, 29000 schools throughout the country, and what would be needed to improve them, and what it would cost.

What happened to John Samuel, I asked?

I heard him speak at Unisa nearly 20 years ago, and was impressed. As I wrote in my diary (13 October 1992):

In the morning the Africa Studies forum had a symposium on the reform and restructuring of the education system. John Samuel of the ANC spoke, very well I thought. He said that the universities needed to participate in the public debate on education policy. He also said that there were more than 6 million illiterate adults, yet no university was undertaking serious research into the problem. There were questions afterwards, and the Dean of the Faculty of Education said that in a democratic society a person had the right to be illiterate. That says a lot about the Faculty of Education. I was very impressed with John Samuel. There was a Dr Segal from the National Education Policy Initiative, who showed a lot of charts to show the present condition of education, which did not look good, and then went on to say that there were 21 universities and 16 technikons in the country, but there is no system of post secondary education. The bodies, such as the Committee of University Principals, that did exist could only act on matters they agreed on, which were almost entirely trivial. A Dr Lemmer then spoke on women in the universities, and pointed out that female academic staff hardly got a look in on the more senior posts.

And what happened to John Samuel? He was sidelined in the political scramble for the best jobs by people whose ambitio0n vastly exceeded their expertise, and is now retired.

In Pietermaritzburg we visited Colin Gardner, retired professor of English at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. I’d known him not only as a teacher, but also as chairman of the local branch of the Christian Institute and a fellow-member of the Liberal Party. After retiring from the university he became an ANC city-councillor for Pietermaritzburg and speaker of the city council. We chatter about various things, but the converstion kept turning to the poor state of education.We also visuted Bill Houston, who is doing research into the University Christian Movement, which appeared briefly on the South African scene between 1967 and 1972. But the conversation there kept turning to the failure of educational transformation.

Peter Badcock Walters told us that in Kenya, education is one thing that works well. They have been busily training teachers, and now have more than they need. Perhaps we could import some of them into South Africa, but it probably wouldn’t work, because SADTU (the South African Democratic Teachers Union) is determined to keep education in South Afirca in the Dark Ages of Bantu Education, or even worse, and would object to the very idea of having competent teachers. It’s not entirely SADTU’s fault, and a union is needed to protect teachers from incompetent officials, but it often seems to favour incompetent teachers as well. In one school, apparently, there were 90 pupils taking accounting, and five teachers. Ther teachers planned their work well, for their benefit, if not for the pupils. They put all 90 pupils in one class, and each teacher taught one day a week. That way they could each work one day, and have four days off.

And I recalled when we were planting a church at Tembisa in 2005. Some of the people were involved in a creche, which, when the children gre older, became a pre-primary school, and later a high school. When we were involved with it it was at the pre-primary stage, though still registered as a creche with the social welfare department rather than the education department. It had five teachers, all graduates, all Zimbabweans. They weren’t registered as teachers, merely as creche assistants, but it was very rare to have a pre-primary and infants school (up to grade 3) with graduate teachers. Back in the 1970s when I was manager of some farm schools built on church land in the Utrecht district it was quite acceptable for someone who had just passed Grade 8, with no teacher training at all, to teach the Grade 1 & 2 children. Such was Bantu Education, and our school system is still run on the same lines. But Zimbabwe and Kenya never had Bantu Education, and their teachers are probably the best in Africa.

But we also spoke of hope.

I have visited the schools of some of the young people in our church at Mamelodi, and I was impressed by the dedication of many of the teachers. The schools were often under-resourced, but in their matric year pupils went to extra classes at weekends. There were arranged by the teachers who were paid no extra for giving up their weekends to help their pupils. There are dedicated teachers out there.

One thing that made some of the people we spoke to hopeful was that in spite of a bad education system, some people seemed to come through it with their minds intact. Bill Houston spoke of a woman from the rural area of Pongola in north-eastern KwaZulu-Natal, who had begun her education in a rural school. She said that she found it difficult to explain to the people in her home village the work she currently does — she is a nuclear physicist.

And that reminded us of a time, 38 years ago, when we were involved with a church youth group in Durban North, a white middle class suburb. There was a controversy about corporal punishment in some of the local high schools, and the youth group wanted to discuss it. One member of the parish, Railton Loureiro, was a lecturer at a teacher training college, and we asked him to come and speak to the youth group.

He began by asking how they defined intelligence.

Each member of the group formulated a tentative definition, and when they had all had their say, Railton gave his own definition. “Intelligence,” he said, “is what you do when you don’t know what to do.”

He listened to the young people discussing the caning controversy. Some said that from experiencing unjust punishments at school they had learnt something about justice (not part of the syllabus in apartheid South Africa). Railton asked what they understood by words like “discipline”, and one boy said “the stick”, with no irony intended. Others objected to that, and saw a need for self-discipline. Then Railton said that they might not be able to change the education system, but they could use it. They needed to set their own goals, and see how they could use even a flawed education system to achieve them.

And if a nuclear physicist can come out of a rural school in the Ingwavuma district, then obviously some kids are doing just that.

July 7, 2012

The native school that caused all the trouble

The Native School that caused all the trouble by Philippe Denis

The Native School that caused all the trouble by Philippe Denis

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

For 30 years, a human generation, the Federal Theological Seminary of Southern Africa (Fedsem) was one of the best-known institutions for theological education on the sub-continent. It was born in controversy, it existed in controversy, and it died in controversy, a controversy that continued long after its death. And now, at last, someone has written a history of its brief career, like a meteorite flashing across the sky, twenty years after its death.

At one level it was a bold expression of ecumenism, where clergy of the Anglican, Congregational, Methodist and Presbyterian traditions were trained on the same campus. Yet it was that same ecumenism that ultimately killed it.

At another level it was a thorn in the side of the apartheid government. It was created by apartheid, it resisted apartheid, and the National Party regime tried to kill it. And in the end it died with the apartheid regime, not because of any direct action of the apartheid government, but because of its own internal contradictions.

I was never a student at Fedsem, and never taught there. I had friends who were students there, or who taught there, or both. My contacts with Fedsem were brief and fleeting, and many contradictory and almost incomprehensible stories came out of it. And now at last there is this history, that tells the story as a connected narrative, which enables one to see the wood for the trees.

The Fedsem story is a story of eviction, dispossession and homelessness. The theological colleges used by various denominations for training black clergy were build on the periphery of big cities. The white suburbs of those cities expanded and surrounded them, so that they became “blackspots” in “white” areas, something that the apartheid government could not and would not tolerate. So they had to move.

I knew some of the teachers and students at St Peter’s College (Anglican) in Rosettenville, Johannesburg, in the early 1960s, just before the move. The teachers were members of the Community of the Resurrrection (CR), an Anglican religious order. The CR fathers not only taught in the college, they conducted parish retreats and missions throughout Johannesburg. Across the road from the college was St Benedicts House, a retreat and conference centre, and once a month they held “shoe parties” which were attended by people from far and wide, where a speaker would speak on some topic of interest. That was where I met some of the students (one of them was Desmond Tutu). I also met some of the students at student conferences, and Brother Roger of the CR, who became something of a guru or spiritual elder to me. Brother Roger was a fundi on art and literature, and introduced me to authors I would otherwise never have read, like Samuel Beckett and the Beat Generation authors.

In the college library there was a sculpture of a black madonna by Leon Underwood, the man who taught the famous sculptor Henry Moore. At the end of 1962, when the college was about to move to the new campus at Alice, there was some discussion among the CR fathers about what to do with the sculpture. Brother Roger said they should take it to Alice, with the students, as a kind of symbol of black or African Christianity. It would have been prophetic of the Black Theology that was nurtured in Alice in the coming years. But taking it to Alice would have put it out of reach of the white art cognoscenti of Johannesburg, so in the end it stayed.

Brother Roger was quite enthusiastic about the new federal seminary in Alice, though he himself never taught there, but was transferred back to the CR’s mother house in Mirfield, England. Being forced to move was a bad thing, but it gave the opportunity for a new ecumenical experiment in theological education. The different denominational calleges would share the same campus, and have their own dormitories and dining halls and chapels, to do things in their own style, but they would have a shared library, and shared lectures in some subjects. It was a bit like the college system at some English universities, like Oxford, Cambridge and Durham, which seemed to work quite well.

The land on which the seminary was built at Alice was between a white and a black area, and the government, perhaps relieved at the idea that theological education was becoming a “border industry”, gave the assurance that the seminary could be built there, and would not be forced to move again. It was also adjacent to the University College of Fort Hare, and there was one school of thought that held that theological seminaries should be in or close to universities, so that students cvould study for degrees. There was one problem with this; the government had recently taken over the University College of Fort Hare, and was determined to change the culture of the institution. At that time there were “English” and “Afrikaans” universities in South Africa. The English ones generally encouraged a spirit of free enquiry, and wanted students to think for themselves. The Afrikaans university culture, however, was generally one of conformity. Fort Hare had previously been affiliated to Rhodes University, an “English” university, but when the government took it over with the intention of making it a Xhosa tribal college, the students resisted. The other tribal colleges initially tended to be more docile, because the students had known nothing else.

And the Federal Seminary likewise encouraged students to think for themselves, so it became a refuge for the For Hare students. The authorities at Fort Hare therefore tended to blame the Federal Seminary for student unrest on their own campus, and could not see that it was their own attempts to impose an alien model of education that was the primary cause of the unrest.

Twelve years after the Federal Seminary was established in Alice the land and buildings were expropriated by the government, and the staff and students were told to vacate the buildings two days before the new academic year began. In 1975 the seminary moved to temporary premises in Umtata, but the Transkei homeland authorities also felt threatened. by it, and after a year they had to move again, to the Edendale Lay Ecumenical Centre near Pietermaritzburg. After a few years the seminary acquired new land nearby in Imbali, and the the seminary was rebuilt, but on a more unitary model. The seminary moved into the new buildings in 1980.

In the paragraphs above, I’ve told some of the story that is not in the book, and it seems to me that the book does have some shortcomings in the way it tells the story.

One of the shortcomings is that the book is very thin on the first 7-8 years of the life of the seminary, which would surely have been formative years. The story is told mainly from the point of view of the seminary council, from minutes and memoranda and records of decisions. The staff and students barely feature. The human element of the story is missing. It is only with the emergence of Black Theology (which Fedsem nurtured and developed) in the early 1970s that the story begins to liven up.

But one thing that is apparent is that throughout the life of the seminary there were at least two different models of ecumenism, which sometimes clashed, and and it was that clash, an internal one, rather than external forces, which eventually destroyed the seminary. There was the federal model, favoured by the Anglicans, which we may call Fedsem, and the unitary model, favoured by the Congregationalists, which we may call Unisem. And reading the book one watches with fascinated horror, or horrified fascination, as the decisions made inexorably led to the disintegration of the seminary, the destruction of the buildings, and the end of the bold experiment in ecumenical theological education . The colleges of the different denominations are now as separated as they were before 1963, geographically and in every other way.

According to the authors this disintegration was unforeseen, and that is where I disagree with them. It could easily have been foreseen, and was foreseen. The authors appear to favour the Unisem model, and I suspect that that may be why they gloss over the first seven years or so of the seminary, when it developed within the federal model.

My bias is towards the Fedsem model, and it seems to me, after reading the book, that one of the biggest weaknesses is that they spoke of training people for “the ministry”, without really examining what they thought “the ministry” was. The problem was that the Anglican ministry was different from the Congregational ministry, and the Congregational ministry was different from the Methodist ministry and so on. But I would contend that even within the Anglican view of things, to speak of “the ministry” is to overlook the fact that there are, or should be, many ministries.

The authors quote a letter from Frederick Amoore, the Anglican Provincial Executive Officer, that explains the difficulty and the cultural differences from an Anglican point of view:

There is a good deal of concern among the Bishops about the tendency in some quarters to consider that the seminary is only an institution for theological instruction and for the award of degrees and diplomas. A good deal of the difficulty in relationships comes from the fact that this conception is very different from the Anglican idea of a theological college in which the regular daily life of prayer and worship and the formation of ministerial character and practice is at least as important, if not more so, than the theological instruction given (Denis & Duncan 2011:218).

On the Alice campus, each college (St Peters Anglican, Adams Congregational, John Wesley Methodist, and St Columba’s Presbyterian) had its own chapel, in which they could organise worship according to their own tradition. They could attend each other’s services, and l;earn about each other’s traditions without feeling that their own was threatened.

At Imbali, in the interests of fostering “unity”, there was only one chapel, owned by the Anglicans, but which was used by all. It was owned by the Anglicans because the Anglicans used it more, but it was the Congregationalists and Presbyterians who objected to the furnishings being too Anglican, yet were most insistent that there should be one chapel, to foster unity. But instead of fostering unity, the chapel, and worship generally, became a bone of contention.

The Alice campus showed the diversity of the different traditions participating in Fedsem, but when the Imbali campus was build, the superecumenists insisted that the architecture must emphasise unity (and uniformity) and eventually the different colleges were abolished, mainly at the insistence of Joe Wing and Francois Bill, who tended to be superecumenists. The authors of the book say (Denis & Duncan 2011:230)

Nobody anticipated on the day of Wing’s departure that Fedsem would close less than three years later. It is only with the distance of time that the merging of the three colleges into a single institution appears problematic. Rather than preventing interdenominational tensions, the new structure exacerbated them.

Yet the letter from Frederick Amoore, quoted above, ought to have made it obvious that this would happen. As the model of ministry the seminary was operating on moved further away from that in the minds of most Anglican bishops, the fewer bishops would send their students to the seminary. Some bishops, who had themselves been students at Fedsem, might continue to send students there for a while out of loyalty, but in the end even they would reach a point when they had to say that the training received did not meet the needs of the church.

On reading the book, I was struck by the insistence by what I have called the “superecumenists” on the desirability of uniformity of architecture, and the undesirability of diversity. It reminded me of the similar insistence by 19th-century European missionaries to South Africa that their converts should adopt European architectural styles and build square houses, and some even regarded the number of square houses among their flocks as a measure of their success.

On reading the book, I was struck by the insistence by what I have called the “superecumenists” on the desirability of uniformity of architecture, and the undesirability of diversity. It reminded me of the similar insistence by 19th-century European missionaries to South Africa that their converts should adopt European architectural styles and build square houses, and some even regarded the number of square houses among their flocks as a measure of their success.

I have concentrated on the ecumenism aspect of Fedsem because it was initially one of the greatest strengths of the project, but when overdone became one of its greatest weaknesses. I wonder whether things might have been different if the seminary had not been forced to move from Alice, and had been able to keep the federal structure, architecturally as well as in other ways.

.

But the book is very good in describing what happened, and putting the history (and the fragmented stories that one heard) in perspective.

July 6, 2012

A new beginning, a new hope

I have sometimes written in this blog about the Orthodox children’s home in Atteridgeville, and the parish there (see here, and here). This year the home experienced a setback, as the couple who were running it left. The parish priest of Atteridgeville was transferred to other duties. The main source of funding for the home dried up. Things were looking bleak.

Then this week we had a couple of meetings with some of the leaders of the parish there, which made things look hopeful again.

Angelos (Joel) Mokau spent three years in the Catechetical School in Yeoville, Johannesburg (now closed). But when he finished his course, he was not used in pastoral or evangelistic or any other kind of ministry, and went back to his home parish in Soshanguve. When the parish priest there, Fr Johannes Rakumako, died last year, Angelos helped to lead Readers’ services. Father Athanasius and I asked him how he saw his future ministry, and he said he would like to help the poor, especially old people and children. We suggested him to Fr Elias as a possible person to help run the children’s home in Atteridgeville.

I took him to the two meetings in Atteridgeville, and on the way there, he was much more observant and noticing of things than I was. I had travelled that road many times, but he pointed out things that I had not noticed. “There’s a hospice,” he said. “There’s a skills training centre.” He saw possibilities for ministry everywhere. We passed two young men who waved to us, so we stopped to chat briefly. “Give us work,” they said. As we went on I remarked that perhaps they could benefit from the skills training centre. Angelos said that the people who went to the centre probably came from somewhere else, and the local people would not use it.

Fr Elias had phoned to say he would be late, and so we chatted to two of the local leaders, Artemius Mangena and Demetrius Mahwayi. They were baptised in Mamelodi a few years ago. They have been unemployed for years, but have been involved in various community development projects. They told Angelos about one project that had folded — growing vegetables. It worked quite well for a while, and they provided vegetables for the children’s home, and sold them, but the someone stole their implements, and they suspected some people who were involved in the project, and that’s when it folded. They thought of reporting the theft to the police, but they only had suspicions, no evidence, and they thought it would just cause rifts in the local community. So they have started on another project, a poultry project, and have registered a cooperative, but will be more careful about getting people they can trust. Angelos made several useful suggestions.

Fr Elias still had not arrived, so we said the Third Hour together, led by Artemius and Angelos, and then Fr Elias and Fr Athanasius arrived. It was agreed that Angelos, Artemius and Demetrius would work together with other leaders to build up the parish and the children’s home again, and we would try to find financial support for Angelos to move there and work there full time. The thing that impressed me was how positive they were, and the way they looked at the situation and saw possibilities. It seems to me that Angelos would be a good model of what a deacon should be.

Atteridgeville leaders: Demetrius Mahwayi, Artemius Mangena, Fr Elias, Fr Athanasius, Angelos Mokau. Front row: Melania Nokuthula Sivanda, Jane Lubisi

Please pray for them, and for us all as we try to help and advise them.

July 4, 2012

Missiological mengelmoes: Diaspora and Fresh Expressions

This is a very traditional blog post, going back to the original meaning of a blog — web log — which is a record and commentary on various web sites visited. And there have been some interesting missiological blog posts recently that are worth a read, if you’re missiologically inclined.

To start off with there is Tall Skinny Kiwi: Nomads, Itinerants, and Diaspora Missiology:

Some conversation and action today regarding “people on the move”, global nomads [see my post], and “diaspora missiology”…

Lausanne 3 in Capetown was a great experience for me but there were a few frustrating moments for me, as a global nomad. One of them was deciding which geographical gathering of homies to attend each day. I just didn’t know which country or continent I was from. On the Lausanne website I was from USA. The Lausanne preparary meetings placed me in the UK, as part of the Europe group. But when I met the Aussies and Kiwis I decided to attend a few of their meetings, having lived in both countries. But generally, I felt quite homeless and unassigned to any geographical area.

Why is having a geographical location so important to everyone? Would they make the Apostle Paul attend the Tarsus group? Would Jesus be assigned to the Galileans? Would Abraham be stuck in a room drinking coffee with the residents of Ur?

This one struck me as interesting because of the recent Joint Conference on Religion and Theology that I attended in Pietermaritzburg, where the missiology track emphasised migration and theological education. At that conference most of the papers dealt with mission to migrants, as if the church was by nature static, and so it was about how a static church ministers to people on the move. Andrew Jones (the eponymous Tall Skinny Kiwi) reminds us that missionaries themselves are people on the move, something that seems to be part of the meaning of the term “missionary”.

But the term Diaspora seems to be getting a bit fuzzy. Missionaries are not, or should not be seen as a diaspora. Diaspora means “scattering”, and that is a term that could apply only to the first apostles who scattered from Jerusalem and planted churches all over. Subsequent missionaries do not disperse from a central point, but come from all sorts of places and go to all sorts of places.

Diaspora is a problem for Orthodox mission. Many Orthodox churches have been planted in various parts of the world by the Orthodox Diaspora, who have indeed been migrants as they have travelled for various reason to different parts of the world. But the churches they planted were often ethnocentric, and not really missional churches at all. There was a whole issue of a journal devoted to this phenomenon: Renewal in the Orthodox Churches: the diaspora | Khanya:

It is quite unusual for Western theological or missiological journals to publish anything written by Orthodox theologians and missiologists, or about Orthodox Christianity. But Studies in World Christianity (Edinburgh University Press) edited by Alastair Kee has just published an entire issue devoted to the theme “Renewal in the Orthodox Churches: the Diaspora”

I’ve written more about this here Orthodox diaspora and mission | The Lausanne Global Conversation and here Orthodox mission, diaspora and bizarre Protestant questions | Khanya.

One of the recent aspects of Christian mission has been the idea of Fresh Expression (of church). This has been tried in the UK, and in some other places, and a recent report to the Church of England synod notes that there have been over 1000 such fresh expressions in the Church of England, and more than 2000 in the Methodist Church in the UK. But there have been some questions about the ecclesiology of these Fresh Expressions. Opinionated Vicar: If it’s 3% Fresh, is it Fresh? comments

our Messy Church is probably one of those 1000, but it happens monthly, with a month off in the summer, and whilst it has some of the features of the church ‘event’, it’s not a congregation of Christian disciples. It might be called ‘church’, but it’s not a new, self-sustaining congregation, it’s series of branded events which might form a gateway to Christian faith for some. I wonder how many more of the 1000 are Fresh Expressions, but these are more expressions of outreach than of viable churches. Or am I being unfair?

July 3, 2012

The Hunger Games (review part 2)

Catching Fire by Suzanne Collins

Catching Fire by Suzanne Collins

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I wrote a review of the first book of the series, The Hunger Games but now I’m writing a combined review of the second and third books. The second one had its ups and downs, but they were neither as far up or as far down as the first volume.

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

The twelve districts of Panem are in rebellion against the Capitol, which has ruled and exploited them all, and reminded them all of their subjugation and the cost of rebellion by means of the cruel annual Hunger Games, where two children between the ages of 12 and 18 from each district are chosen by lot to fight to the death in a reality TV show.

The second book, Catching Fire begins with the victors of the Hunger Games from District 12 going on their victory tour, after being warned by President Snow that they must do everything they can to discourage the signs of rebellion that are beginning to appear in some of the districts.

Once again, to say much more of the story would reveal too much of the plot, but I can say that as it seemed to me that the first book started out well, and then plunged to a low point so that I felt as though I wanted to rewrite it, and then the second rose to a kind of comfortable mediocrity, which continues about two-thirds of the way through. But the last part of the third book rises again, almost to the level of the beginning of the story.

It reminded me in some ways of the freedom struggle against the Gaddafi regime in Libya last year, though the book was published the previous year, so perhaps it can be seen as a kind of prophetic prediction.

It is also a kind of parable, or as some might say, an allegory of colonialism, with the Capitol representing the metropolitan power, and the districts representing the colonies. If you are one of those who regards C.S. Lewis’s Narnia stories as “Christian allegory”, then this trilogy is certainly an allegory of colonialism, though I think in both cases it is a misuse of the term “allegory”.

It also raises questions about the moral ambiguity of all freedom struggles — is this truly a struggle for freedom, or is it merely a struggle for regime change?

June 30, 2012

What’s that you were saying?

I’m posting this for the first Orthodox synchroblog, on the words we use, and what we mean when we utter them. One of the things about the growth of electronic communications in the last 25 years or so is that people are communicating more with people in other countries, and find that even if we have a common language, like English, things can be misunderstood.

I’ve blogged about this before — here, for example A failure to communicate — words and meaning | Khanya — and for a while was thinking of recycling that post for the synchroblog. It is concerned with a term used frequently by Americans, “massive programs”, which people in other countries often find quite bewildering. But actually there is plenty more to say on the subject. On second thoughts, however, perhaps I have too much to say on the subject; I worked for a number of years as a newspaper proofreader, and later as an editor of academic texts, which sensitised, and some might say over-sensitised me to this kind of thing.

Where does one cross the line from trying to communicate accurately and clearly, on the one hand, and merely being pedantic on the other?

One example that made an indelible impression on me was when I was writing a history exam for the University of South Africa, and one of the questions said “motivate your answer”. I puzzled over this for about 15 minutes, and wondered what I was supposed to do. Should I give my motive for answering that question rather than another? Should I write something like “Answer, you’d better impress the examiner, or I will personally come and tear you up”?

The University of South Africa (Unisa) was a bilingual distance-education university, where students received printed study guides in either English or Afrikaans, but I suspected that most of the lecturers were Afrikaans speaking, and translated their exam questions into English. So when I got home after the exam I looked in an Afrikaans dictionary, and discovered that the Afrikaans word motiveer means “give reasons for”. No English dictionary, however, gave that meaning for “motivate”. And by then it was a bit too late.

Later on I was tutoring a theology student who was studying through Unisa, and he had to submit a written assignment on the “Apostolicum”. Neither of us had a clue what the “Apostolicum” was. It turned out to the the statement of faith usually referred to in English as “The Apostles Creed”. Orthodox Christians don’t use the “Apostles Creed”, but we use what Western Christians call the “Nicene Creed”, which we refer to as “The Symbol of Faith”. So we use different terms to refer to the same thing, and the same terms to refer to different things.

Some years later I was working for the University of South Africa myself, editing the study guides sent to students, and because of my past experience I was acutely conscious of the need for clarity. In reading the text, I would try to imagine it being read by a student in the mountains of Lesotho, snowbound in the middle of winter. She would be reading the English text, but her home language was Sesotho, and English was her second language. And the university lecturer who wrote the text would be Afrikaans speaking and the text would be in his second language. So there was a double translation going on. So if the student can’t understand the text, she might not find it easy to phone the lecturer to ask. The nearest telephone is at a country store 10 miles away over the mountain, and the pass is blocked with snow, and even if she manages to get there, the phone line could be down because of the snow. So it would be important to explain technical terms, and the technical terms should be explained using words that the student can find in a dictionary.

So sometimes meaning can be lost in transation.

But sometimes meaning can be lost even when there is no translation involved. People make use of words in new ways, and give them different meanings. Sometimes this is done deliberately. Sometimes it is part of a natural development of language.

The White Gaze

There are popularised technicalities, and technicalised everyday words. For example, some academics use the ordinary English word “gaze” in a technical sense that would be confusing to the non-specialist reader. My English dictionary says that “gaze” means to look long and fixedly, especially in wonder or admiration. But if you look in Wikipedia you can also learn that Foucault uses the term gaze in the distribution of power in various institutions of society. The gaze is not something one has or uses; rather, it is the relationship in which someone enters. “The gaze is integral to systems of power and ideas about knowledge”.’ This is not something that one can learn from the dictionary definition of the term; I’m not even sure that one can learn anything about it from reading that sentence in Wikipedia.

Gazeless

Another example, which has to do with the political history of South Africa, relates to racism. That word appeared in the early 1960s. The word that was previously used was “racialism”. In the early 20th century “racialism” referred to bad feeling between English and Dutch-speaking white people. Racialists were those who saw these groups as essentially opposed to each other, and who favoured political policies that would benefit one group rather than the other. English-speaking racialists, for example, wanted all teaching in schools to be in English, rather than Dutch (and later Afrikaans).

The term “racialism” gradually came to refer to relations between white people and black people in South Africa, or, as they were called in those days, “Europeans” and “Non-Europeans”. Non-Europeans were divided into “Indians” (later “Asiatics”, and later still “Asians”), “Coloureds” and “Natives” (later “Bantu). All these terms enjoyed periods of political correctness, and later came to be regarded as politically incorrect.

When the policy of apartheid was introduced in 1948, some people opposed it. They said that South Africa was a multiracial country, and that its government should also be multiracial. Politicians in neighbouring countries also used the term, but Roy Welensky, the prime minister of Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) gave multiracialism a bad name when he explained what he meant by it. It was not apartheid — the rigid separation of diffrerent races having political power in their “own” areas. It was rather a partnership between different races, like the partnership between horse and rider, with the white man being the rider and the black man being the horse.

It was then that others adopted the policy of nonracialism. This was the idea that race should cease to count as a category that determined anyone’s political, social or economic rights. In a nonracial society, race should not determine where you could live, whether or where you could vote, what kind of work you could do, where you could go to school or who you could associate with. Nonracialism was adopted as a political principle by various opposition groups in the 1950s and 1960s, notably the African National Congress (and various other groups in the Congress movement), the Liberal Party and others.

Nonracialism was not met with universal approval, even by those who opposed the National Party government and its apartheid policy, and some, who preferred an Africanist policy, broke away from the ANC to form the Pan Africanist Congress.

Perhaps because “racialism” had become a part of words like “multiracialism” and “nonracialism”, which referred to political and constitutional arrangements, it was gradually replaced by the shorter word “racism” to refer to the feeling of hostility and antagonism towards people perceived as belonging to other races. By the end of the 1960s “racialism” was hardly heard anymore; people spoke of “racism”.

Between 1990 and 1994 South Africa abandoned apartheid, and an ANC government was elected in 1994 with the aim of building a democratic and nonracial society. The National Party, which had advocated apartheid, dwindled and eventually disappeared from the scene. The Pan Africanist Congress, which still advocated an “Africanist” rather than a nonracial policy, never managed to get more than 1% of the vote. At one point some of their spokesmen had used the slogan “one settler, one bullet” as a counter to the nonracialist slogan of “one man, one vote”. After the elections people began joking about “One settler, one bullet, one percent.”

But more recently some people have been twisting these words, to claim that “nonracialism” is actually “racist” — see Whiteness Studies, Black Consciousness and non-racialism | Khanya. They have done this by importing words from an entirely different context (North America), and twisting them to discredit the aim of a democratic nonracial society that we struggled for for fifty years and more, and in many ways still have to build. In denigrating the idea of a nonracial democratic society, and denouncing it as “racist”, they don’t say what they want to put in its place. Or if they do, they have buried it in incomprehensible verbal mush.

In his novel 1984 George Orwell described this kind of thing as “newspeak” or “doublespeak”. People would shout slogans like “war is peace and peace is war”. And so, in South Africa today, people are saying that nonracialism is racism.

As George Orwell said, in his Politics and the English language

Now that I have made this catalogue of swindles and perversions, let me give another example of the kind of writing that they lead to. This time it must of its nature be an imaginary one. I am going to translate a passage of good English into modern English of the worst sort. Here is a well-known verse from Ecclesiastes:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

Here it is in modern English:

Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

_________

This post is part of an Orthodox synchroblog, that is, a number of Orthodox Christian bloggers have written blog posts on the same general topic on the same day, with links to the other posts on the same topic, so it should be possible to surf from onne post to the other, and read them all if one wants to.

The theme of this month’s synchroblog is “The words we use”.

If you have written a contribution for this synchroblog, you may copy this list of links and post it at the end of your own contribution.

Cristina Perdomo (Orthodox Christian — Orthodox Church in America (OCA)) of Reachingfromadistance on Cement

Dn Stephen Hayes (Orthodox Christian) of Khanya on What’s that you were saying?

Susan Cushman (Orthodox Christian) of Pen & Palette on How We Use Our Words: “Christian” is Not an Adjective

June 29, 2012

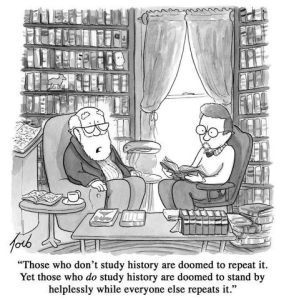

Apartheid wasn’t so bad – historian

A few days ago a well-known historian, Hermann Giliomee, wrote an article published in the newspaper Rapport with the headline Apartheid: Was dit dan net boos? (Apartheid: was it just evil, then?).

Giliomee is the author/editor of New history of South Africa, which claims to put the bias of apartheid-era textbooks behind it. I haven’t finished reading it yet, and haven’t reached his treatment of the apartheid period, but after reading the article in Rapport I’ll be reading it with a great deal more suspicion.

In the Rapport article, according to Giliomee, many politicians and political commentators are trying to create the impression that apartheid was an ideology that was uniquely evil and much more oppressive than the pre-1948 segregation policy.

As the journalist Piet Cillié put it in 1985, the impression is created that South Africa was a nice integrated multiracial community that was divided and fragmented by dictatorial NP-governments and so prevented from “developing the friendly relationships that it was heading for.”

According to this view of history, after 1948 the country was on a long economic, political and social downhill path, on which the retrogression was only halted in 1990.

Like Cillié, I think that this is a totally distorted understanding of history (my translation).

Giliomee goes on to say that South Africa would not have had such rapid economic development were it not for apartheid, and though he acknowledges that none of his propositions can be proved, the historian must nevertheless be prepared to think the unthinkable — the unthinkable, apparently, being that apartheid was not so bad after all.

He also quotes another historian, Herbert Butterfield, to the effect that if we try to judge the past with the moral insights of the present, we will just be creating a giant optical illusion.

In doing this, I suggest that Giliomee is himself trying to creat a giant optical illusion: he implies that we cannot judge apartheid by the moral insights of our time, but we must judge it by the standards of its own time. The problem with this is that apartheid was judged by the standards of its own time, and found wanting. Christian churches called apartheid a heresy, and worse than a heresy, a pseudogospel. This was not the judgement of a later age, judging by hindsight. It was a contemporary judgement. Quoting Butterfield at this point is disingenuous.

Giliomee’s main argument appears to be that apartheid was just a logical development of segregation policies that existed before 1940, and it was just an intensification of those earlier policies; in other words, it differed in degree, but not in kind, from the earlier policies.

He also speculates (in his terms, “thinking the unthinkable”) “Rapid racial integration could take place, or the country could experience 25 years of reasonable stability. Both could not take place at the same time.”

I don’t kniw of anyone who was proposing “rapid racial integration” before 1948, or even after 1990. Eighteen years after our first democratic nonracial elections, no “rapid racial integration” has taken place. If it hasn’t happened now, I doubt that it would have happened back then.

Giliomee speaks what might have happened if “liberal” policies had been introduced in the 1940s, but one could just as easily speculate on what might have happened if the Cape nonracial franchise had been introduced throughout the Union of South Africa in 1910. Or would that have been “unthinkable”?

Throughout the 20th century there were two opposite trends in South Africa — one towards greater segregation, and the other towards less. One gained the ascendency in 1948, and the other in 1990.

Giliomee also compares apartheid with segregation in the southern states of the USA in the same period, and implies that if such views were as widely accepted, they could not be all that bad.

He objects to commentators seeing apartheid as “uniquely evil”, but also objects to comparisons with Stalin, Hitler, Saddam Hussein and Pol Pot. If it is unique, however, then it is incomparable; it cannot be compared to anything else. And I think one could say with some fairness that though many bad things happened in South Africa before 1948, there was nothinmg to compare, in the scale of evil, with the treatment of American Indians in the USA. I read Bury my heart at Wounded Knee in 1973, at the height of apartheid. It impressed me and gave me some more insight into the workings of apartheid. And it also impressed me in that it seemed to be so much worse. Even apartheid at its worst could not match it.

But there was a qualitative difference between apartheid and pre-1948 segregation. The pre-1948 policies were racist, and they were based on racial prejudice. But for the most part they were ad-hoc policies, reactions to circumstances, based on this prejudice.

Where apartheid differed was that it was calculated and planned. It was proactive rather than reactive. It turned racial prejudice into an ideology. Even in that, however, it wasn’t unique, because the Nazis had done something similar. As B.J. Vorster said in 1942:

We stand for Christian Nationalism, which is an ally of National Socialism. You may call the anti-democratic system dictatorship if you like; in Italy it is called Fascism, in Germany National Socialism, and in South Africa Christian Nationalism.

Apartheid resulted in the deliberately-planned ethnic cleansing of 3-4 million people. That didn’t make it unique, but it did make it evil.

Before 1948 there were some people who thought segregation a good thing, and thought it should be continued, and even intensified. Others thought that racial prejudice was a bad thing, and wanted South Africa to move away from that system. Many thought it was manifestly unjust.

After 1948, however, the NP-government tried its best to suppress the second tendency. Apartheid was more than just a political policy of racial segregation. It was a totalitarian ideology. Thinking outside the apartheid box was forbidden. And the intention of the apartheid ideology was to make it unthinkable. Christian National Education was intended to indoctrinate children in schools so that they could only think in terms of apartheid and not be exposed to any contrary ideas. According to apartheid educationists (or pedagogicians, as they liked to call themselves) it was the “greatest possible injustice” for a child to be taught by someone of a different ethnic or cultural group. Think about that for a moment: “greatest possible”. You could starve a child, whip him, push burning cigarettes into her, lock him in a lightless cellar, make him slave in a mine or factory or farm at starvation wages, keep her as a sex slave, but none of those would be as great an injustice as being taught by a teacher of a different ethnic or cultural group.

There was quite a lot of resistance to the apartheid ideology in the early 1950s — the Torch Commando and the Defiance Campaign come to mind. It was not, as Giliomee, following Cillié, tries to present it. Apartheid was devised, and deliberately devised, to counter any tendency to think that a non-racial society would be desirable, a society in which, as Martin Luther King once put it, little black children and little white children would not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.

Cillié and Giliomee might maintain that this tendency did not exist, but it did. It existed in civil society alongside the tendency towards increased segregation. It manifested itself in civil society organisations, such as churches, and, despite what Cillié says, it ‘was divided and fragmented by dictatorial NP-governments and so prevented from “developing the friendly relationships that it was heading for.”‘

It seems all too easy for people like Giliomee to forget the darkness from which we have come, and to attempt to whitewash it and not merely to pretend that it didn’t happen, but to try to erase it from people’s memories. And it was to counter such tendencies that I’ve been writing a series of blog posts, Tales from Dystopia, to remember what it was actually like under the NP-dictatorship.