Nate Silver's Blog, page 59

September 15, 2019

Do You Buy That … There Was No Clear Winner From The Third Democratic Debate?

September 13, 2019

Politics Podcast: What Happened When The Front-Runners Were All On Stage

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

The three polling leaders — Joe Biden, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders — shared a debate stage for the first time Thursday night. From the spin room floor in Houston, the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast broke down who came out on top and who struggled.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

September 11, 2019

Buy, Sell Or Hold? A Special Democratic Debate Edition

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): Welcome, everyone, to a special debate-focused preview edition of our weekly politics chat!! In recent weeks, we’ve talked a lot about the different strategies the candidates should use on the debate stage, who the lineup is good for (and who it’s bad for) and whether the field might be consolidating around a handful of candidates.

So today, let’s have a little fun with the question of candidate debate strategy and play a game of buy/sell/hold with PredictIt prop bets (plus some I made up). We checked the prices (given in cents) of a bunch of propositions at noon Eastern on Tuesday and then translated those prices into probabilities. (We know that’s not exactly right, but it’s close enough.)

And in case you forgot how to play buy/sell/hold:

Buy means: “I think the chances of this happening are higher than indicated.”

Sell means: “I think they’re lower.”

Hold means: “I’m a coward and am unwilling to take a stand.”

OK, let’s start with a

September 10, 2019

If Youâre Polling In The Low Single Digits, Youâre Probably Toast

Yesterday, I wrote about the middle and upper echelons of the Democratic field: those candidates who are polling in the mid-single-digits or higher. You can certainly posit a rough order of which of these candidates are more likely to win the nomination. Iâd much rather wager a few shekels on Joe Biden than Pete Buttigieg, for instance. But I donât think thereâs any hard-and-fast distinction between the top tier and the next-runners-up.

For candidates outside of that group — those polling in the low single digits, or worse — I have less-welcome news. I donât really care which order you place them in, because unless they turn it around soon, theyâre probably toast.

In this article, Iâm mostly referring to Cory Booker, Beto OâRourke, Julián Castro and Amy Klobuchar, who Iâll refer to as the BOCK candidates (Booker/OâRourke/Castro/Klobuchar) for short. Some of this also applies to candidates (e.g. Michael Bennet) who didnât make this weekâs debate at all, although theyâre in even worse shape. Iâm not counting Andrew Yang as part of this group, however. Heâs actually polling slightly better than the BOCKs, despite lower name recognition, and is more of a sui generis case.

Subjectively speaking, the BOCK group is a reasonably interesting and well-qualified set of candidates. At times, Iâve thought various members of this group were poised for a breakout. (I also thought some of them, such as Klobuchar, would come out of the gate stronger when they initially launched their campaigns.) If you fast-forwarded to next July and one of these candidates — Booker, say — was accepting the Democratic nomination in Milwaukee, it wouldnât be that surprising on some level. They have the sort of profile that resembles those of past presidential nominees.

But the BOCK candidates donât have the polling of those past nominees. And empirically, thatâs a pretty enormous problem for them. As my colleague Geoffrey Skelley discovered in his series on the predictive accuracy of early primary polls, only one candidate in the modern primary era has come back from averaging less than 5 percent in national polls in the second half of the year before the primary to win the nomination. That was Jimmy Carter, who did so in 1976. Given the number of candidates who failed to make it, that would make their chances of winning the nomination very low — somewhere on the order of 1 or 2 percent.

Now, you might look at someone like a Booker or a Klobuchar and assume that theyâre better qualified than the candidates who were polling in the low single digits in past nomination races. But thatâs not necessarily true. Sure, those races included plenty of Alan Keyeses and Dennis Kuciniches, but there were also plenty of other senators and governors who were highly plausible nominees but whose campaigns just never really gained traction.

Of course, there are a few caveats and qualifications. Geoffreyâs research covers polling across the entire second half of the pre-election year — that is, from July through December. If Booker or Klobuchar began surging in the polls now, they could finish above that 5 percent threshold over the six-month period. Also, these candidates are running full-fledged campaigns, whereas some of the low-polling names from past nomination cycles spent a lot more time flirting with whether to run or not.4 Meanwhile, Booker and Klobuchar (more so than OâRourke or Castro) have decent numbers of endorsements, which are historically a fairly predictive indicator, although most of those endorsements are from their home states.

So, if you want to go to the mat and argue that Booker or one of the other BOCK candidates has, I donât know, a 5 percent chance of winning the nomination, Iâm not really going to argue with you. (And collectively, they have a better chance than they do individually, of course. Keep that in mind if youâre hate-reading this column a year from now because OâRourke won the nomination or something.)

But a lot of this smacks of special pleading, and ignores that the empirical evidence is fairly robust in this case: Lots of candidates have hoped to come back from polling in the low single digits to win their nominations, and almost none of them have done it. A somewhat larger group have emerged as factors in races that they ultimately didnât win — Rick Santorum in 2012, for example — but elections arenât something where close really counts. Nor are any of these candidates polling especially well in Iowa or New Hampshire, which is the path that dark-horse candidates (such as Carter or Santorum) usually take to enter the top tier.

Itâs also pretty hard to know what type of event might trigger a sudden surge in support for one of the BOCKs. Castro and Booker had strong nights in the first and second debates, respectively, and it barely moved the numbers for them. OâRourke saw a spike in media attention following the mass shooting in his home town of El Paso, Texas, and his support in polls didnât move much after that, either.

Moreover, Democrats are fairly satisfied with their field, and theyâre paying a relatively large amount of attention to the campaign as compared with similar stages in past nomination races. Thatâs also a bearish indicator for the BOCKs. Democrats arenât necessarily shopping around for fresh alternatives, in the way that Republicans were in 2011 and 2012, when Santorum, Newt Gingrich, Herman Cain and others surged and declined in the polls.

That may be because the top three to five candidates do a relatively good job of covering the various corners of the Democratic primary. College-educated voters tend to like Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris and Buttigieg; non-college voters have Biden and Bernie Sanders. Older voters tend to like Biden, whereas Sandersâs and Warrenâs supporters are younger. Moderates have Biden, while liberals have lots of alternatives. Biden is well-liked among black voters, and if they sour on him, thereâs Harris. Hispanic voters donât have an obvious first choice, and maybe thereâs a niche for a moderate candidate who isnât Biden for voters who think Biden is too old. But overall, the Democratic electorate is pretty well picked over.

Put another way, if youâre wondering why candidates such as Castro and Booker arenât gaining more traction despite seemingly having run competent campaigns, the answer may have less to do with them and more to do with the fact that the field has a lot of heavyweights. Biden is a former two-term vice president; Sanders was the runner-up last time and basically built an entire political movement, and Warren and Harris have been regarded as potential frontrunners since virtually the moment that Donald Trump won the White House. The years that produce volatile, topsy-turvy nomination races, such as the 1992 Democratic primary, tend to be those where a lot of top candidates sit out, perhaps because theyâre fearful of running against an incumbent with high approval ratings. Trump looks beatable, however, and almost all of the highly plausible Democratic nominees, save Sherrod Brown, ran. There isnât much oxygen for those at the top of the field, let alone for the candidates a few rungs down.

If You’re Polling In The Low Single Digits, You’re Probably Toast

Yesterday, I wrote about the middle and upper echelons of the Democratic field: those candidates who are polling in the mid-single-digits or higher. You can certainly posit a rough order of which of these candidates are more likely to win the nomination. I’d much rather wager a few shekels on Joe Biden than Pete Buttigieg, for instance. But I don’t think there’s any hard-and-fast distinction between the top tier and the next-runners-up.

For candidates outside of that group — those polling in the low single digits, or worse — I have less welcome news. I don’t really care which order you place them in, because unless they turn it around soon, they’re probably toast.

In this article, I’m mostly referring to Cory Booker, Beto O’Rourke, Julian Castro and Amy Klobuchar, who I’ll refer to as the BOCK candidates (Booker/O’Rourke/Castro/Klobuchar) for short. Some of this also applies to candidates (e.g. Michael Bennet) who didn’t make this week’s debate at all, although they’re in even worse shape. I’m not counting Andew Yang as part of this group, however. He’s actually polling slightly better than the BOCKs, despite lower name recognition, and is more of a sui generis case.

Subjectively speaking, the BOCK group is a reasonably interesting and well-qualified set of candidates. At times, I’ve thought various members of this group were poised for a breakout. (I also thought some of them, such as Klobuchar, would come out of the gate stronger when they initially launched their campaigns.) If you fast forwarded to next July and one of these candidates — Booker, say — was accepting the Democatic nomination in Milwaukee, it wouldn’t be that surprising on some level. They have the sort of profile that resembles those of past presidential nominees.

But the BOCK candidates don’t have the polling of those past nominees. And empirically, that’s a pretty enormous problem for them. As my colleague Geoffrey Skelley discovered in his series on the predictive accuracy of early primary polls, only one candidate has come back from averaging less than 5 percent in national polls in the second half of the year before the primary to win the nomination. That was Jimmy Carter, who did so in 1976. Given the number of candidates who failed to make it, that would make their chances of winning the nomination very low — somewhere on the order of 1 or 2 percent.

Now, you might look at someone like a Booker or a Klobuchar and assume that they’re better qualified than the candidates who were polling in the low single digits in past nomination races. But that’s not necessarily true. Sure, those races included plenty of Alan Keyeses and Dennis Kuchinches, but there were also plenty of other senators and governors who were highly plausible nominees but whose campaigns just never really gained traction.

Of course, there are a few caveats and qualifications. Geoffrey’s research covers polling across the entire second half of the pre-election year — that is, from July through December. If Booker or Klobuchar began surging in the polls now, they could finish above that 5 percent threshold over the six-month period. Also, these candidates are running full-fledged campaigns, whereas some of the low-polling names from past nomination cycles spent a lot more time flirting with whether to run or not.1 Meanwhile, Booker and Klobuchar (more so than O’Rourke or Castro) have decent numbers of endorsements, which are historically a fairly predictive indicator, although most of thoss endorsements are from their home states.

So, if you want to go to the mat and argue that Booker or one of the other BOCK candidates has, I don’t know, a 5 percent chance of winning the nomination, I’m not really going to argue with you. (And collectively, they have a better chance than they do individually, of course. Keep that in mind if you’re hate-reading this column a year from now because O’Rourke won the nomination or something.)

But a lot of this smacks of special pleading, and ignores that the empirical evidence is fairly robust in this case: Lots of candidates have hoped to come back from polling in the low single digits to win their nominations, and almost none of them have done it. A somewhat larger group have emerged as factors in races that they ultimately didn’t win — Rick Santorum in 2012, for example — but elections aren’t something where close really counts. Nor are any of these candidates polling especially well in Iowa or New Hampshire, which is the path that dark-horse candidates (such as Carter or Santorum) usually take to enter the top tier.

It’s also pretty hard to know what type of event might trigger a sudden surge in support for one of the BOCKs. Castro and Booker had strong nights in the first and second debates, respectively, and it barely moved the numbers for them. O’Rourke saw a spike in media attention following the mass shooting in his home town of El Paso, Texas, and his support in polls didn’t move much after that, either.

Moreover, Democrats are fairly satisfied with their field, and they’re paying a relatively large amount of attention to the campaign as compared with similar stages in past nomination races. That’s also a bearish indicator for the BOCKs. Democrats aren’t necessarily shopping around for fresh alternatives, in the way that Republicans were in 2011 and 2012, when Santorum, Newt Gingrich, Herman Cain and others surged and declined in the polls.

That may be because the top three to five candidates do a relatively good job of covering the various corners of the Democratic primary. College educated voters tend to like Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris and Buttigieg; non-college voters have Biden and Bernie Sanders. Older voters tend to like Biden, whereas Sanders’s and Warren’s supporters are younger. Moderates have Biden, while liberals have lots of alternatives. Biden is well-liked among black voters, and if they sour on him, there’s Harris. Hispanic voters don’t have an obvious first choice, and maybe there’s a niche for a moderate candidate who isn’t Biden for voters who think Biden is too old. But overall, the Democatic electorate is pretty well picked over.

Put another way, if you’re wondering why candidates such as Castro and Booker aren’t gaining more traction despite seemingly having run competent campaigns, the answer may have less to do with them and more to do with the fact that the field has a lot of heavyweights. Biden is a former two-term vice president; Sanders was the runner-up last time and basically built an entire political movement, and Warren and Harris have been regarded as potential frontrunners since virtually the moment that Donald Trump won the White House. The years that produce volatile, topsy-turvy nomination races, such as the 1992 Democratic primary, tend to be those where a lot of top candidates sit out, perhaps because they’re fearful of running against an incumbent with high approval ratings. Trump looks beatable, however, and almost all of the highly plausible Democratic nominees save Sherrod Brown ran. There isn’t much oxygen for those at the top of the field, let alone for the candidates a few rungs down.

September 9, 2019

Politics Podcast: How To Win This Week’s Debate

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

This Thursday, 10 Democrats vying for the presidential nomination will share a stage for the first time. We’ve discussed what strategies for the top three candidates — Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — might adopt, but the debate is also an opportunity for the lower-tier candidates to gain traction. In this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew devotes the entire episode to discussing what each candidate’s debate strategy might — or should — be.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Is It Really A Three-Candidate Race?

A much-discussed poll last month showing an effective three-way tie between Joe Biden, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders at the top of the Democratic primary field has since proven to be something of an outlier. But the narrative that the Democratic primary has collapsed down into a three-way race between Biden, Warren and Sanders is still going strong.

Now that we’re past the Labor Day holiday — traditionally a time when the pressure increases on lesser-running candidates to either improve their performance or to drop out — is the “three-way race” the right way characterize the primary? On ABC News’s This Week on Sunday, I gave a quick answer to this question.2 (p.s. Our “Do You Buy It?” segment on This Week, usually featuring yours truly, is airing almost every Sunday now, so we hope you’ll tune in!) But this is fairly challenging question, so let me give a longer answer here.

The question is challenging because it really involves two distinct components:

Are candidates who are polling in the low single digits — there are a lot of these candidates! — in deep trouble? Or do they have plenty of time to come back?

Among those candidates with more of a pulse in the polls, do Biden, Sanders and Warren form a clear top tier?

Let’s take these one at a time — today, we’ll try to define that top tier, and tomorrow we’ll explore whether any of the bottom-dwelling candidates have much of a prayer.

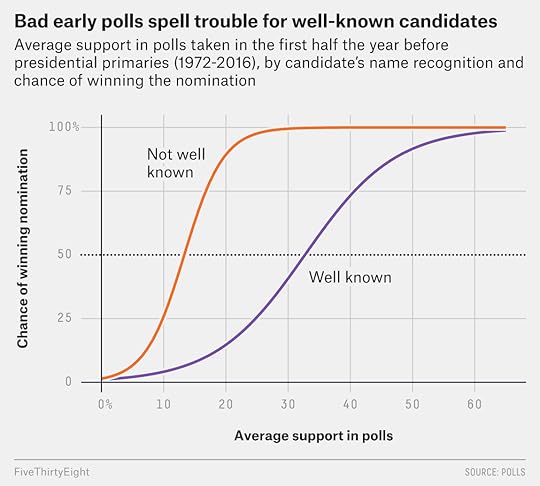

Defining the top tier is a challenge. To develop some very crude priors, let’s turn to my colleague Geoffrey Skelley’s research on the predictive accuracy of early primary polls, which included a chart showing how a candidate’s standing in national polls translates to his or her chances of winning the nomination:3

Depending on which polling average you look at, Biden’s currently polling at 28 to 30 percent, Warren’s at 18 to 19 percent, Sanders is perhaps just a hair below her at 15 to 18 percent, and Harris is at 7 or 8 percent. All of them would count as “well-known” candidates by our definition,4 although Harris is somewhat less well known than the others. They’re followed in the polls by two candidates who aren’t as well known: Pete Buttigieg at 4 or 5 percent, and Andrew Yang at about 3 percent. Historically, these less-well-known candidates have a lot more room to grow from single-digit polling.

If you look up each candidate in the chart, you’d come up with roughly the following for the odds of their winning the nomination. To be extra clear, this is just a simple calculation based only on national polls, not a FiveThirtyEight forecast. For a fun comparison, I’ll also show each candidate’s probability of winning the primary according to the betting market Betfair as of early Sunday evening:

Biden leads polls, but prediction markets favor Warren

Chance of winning the Democratic presidential nomination based on …

Candidate

national polls

Prediction market (Betfair)

Biden

35%

22%

Warren

15

33

Sanders

10

14

Harris

5

10

Buttigieg

5

5

Yang

5

5

Betfair price is as of Sept. 8 at 5:30 p.m.

All right, there’s lots to unpack here. For one thing, based on national polls alone, Biden is still really in a tier by himself. It’s not just that polling at 28 or 30 percent is quite a bit higher than 17 or 18 percent. It’s also that the difference between Biden’s polling and the candidates below him falls within a range that, empirically, has been something of an inflection point as to who eventually wins the nomination or not. Candidates who are sitting in the mid-to-high teens — such as Warren and Sanders — don’t have a fantastic track record. A candidate in Biden’s position will still lose more often than not, but they have a considerably better record of success historically.

Of course, there’s no reason you should limit yourself to looking only at national polls. If you were building a predictive model at this stage, it would probably consist of some sort of amalgam of national polling adjusted for name recognition, early-state polling and endorsements, which are historically fairly predictive of nomination outcomes. In Iowa and New Hampshire, Biden looks weaker and Warren and Sanders (and to some extent Buttigieg) look a lot more viable. But endorsements are another story and those don’t look especially good for Warren and Sanders. Instead, Biden and Harris are well out in front in endorsements, although many potential endorsers are sitting on the sidelines.

The prediction markets deviate a lot from the objective data in the cases of Warren and Biden. They actually had her as being more likely to win the nomination than him (as of Sunday evening), even though he’s ahead in national polls and endorsements, and at worst tied with her in Iowa and New Hampshire (and way ahead in South Carolina). That isn’t necessarily wrong; it’s an early enough stage of the primary that I’d say there’s some room for subjectivity. But there are also some reasons to be cautious. The conventional wisdom has repeatedly expected Biden to implode when it hasn’t really happened yet. And frankly, the people trading in these markets — mostly younger and well-educated — aren’t your prototypical Biden voters.

And none of this makes it any easier to divide the candidates into tiers. For me, at least, the lines between the top several candidates are blurry. I’m pretty sure that I still like Biden’s chances better than Warren — as I said, that’s certainly where a statistical model would come out. But I wouldn’t wager a huge amount of money on that proposition. I think Warren has a few things going for her that Sanders doesn’t — less voter concern about her age, more room to make peace with the establishment and slightly better polling. But you could argue that they should basically be treated as tied.

I’m also not quite sure what to do with Harris. A “Party Decides” rubric that heavily emphasized endorsements and the ability to build a broad coalition would treat her as one of the favorites, while the polling wouldn’t. Then again, she’s had moments where she was polling better, and she could be poised to benefit if Biden falters among black voters or Warren does among college-educated ones. One reason to be pessimistic about the chances of candidates such as Cory Booker and Beto O’Rourke, in fact, is that if something did happen to one of the frontrunners, Harris would probably be first in line to benefit from that.

Overall, the best I can do is something like this:

Nate’s not-to-be-taken-too-seriously presidential tiers

For the Democratic nomination, as revised on Sept. 9, 2019

Tier

Sub-tier

Candidates

1

a

Biden

b

Warren

c

Sanders

d

Harris

2

Buttigieg

3

Yang, O’Rourke, Booker, Klobuchar, Castro

4

Everyone else

Note: Steve Bullock was demoted into the “everyone else” tier.

Even if you do have Biden, Warren and Sanders as your top three candidates (as I do), there’s no particular reason to draw a firm line at three candidates as opposed to some other number. If you’re just looking at national polls, then Biden’s still in a tier by himself. Prediction markets basically have it as a two-horse race between Warren and Biden. You can add Sanders to make it a top three… but factor in endorsements, and Harris probably also needs to join the group, which would leave us with four candidates. I don’t really put a lot of emphasis on money raised, as it hasn’t been a very predictive indicator historically, but if you did, you could add Buttigieg to the top tier and make it a top 5.

Perhaps this week’s debate will provide more clarity. If Warren has another strong debate and continues gaining in the polls, for instance, we might have a relatively clear two-way race between her and Biden. But the reality will probably be a lot messier.

September 4, 2019

2019 NFL Predictions

UPDATED AUG. 27, 2019, AT 5:52 PM

2019 NFL Predictions

For the regular season and playoffs, updated after every game.

More NFL:Every team’s Elo historyCan you outsmart our forecasts?

Standings

Games

Quarterbacks

Show our quarterback-adjusted Elo forecast

Show our traditional Elo forecast

1636

NE-logoNew EnglandAFC East11-5+105.680%68%43%14%

1604

KC-logoKansas CityAFC West10-6+74.167%49%29%8%

1594

NO-logoNew OrleansNFC South10-6+64.562%45%25%7%

1584

PHI-logoPhiladelphiaNFC East10-6+66.264%50%27%8%

1583

LAR-logoL.A. RamsNFC West10-6+56.860%45%24%6%

1573

LAC-logoL.A. ChargersAFC West10-6+54.458%37%21%6%

1567

CHI-logoChicagoNFC North9-7+43.954%38%20%6%

1567

PIT-logoPittsburghAFC North9-7+51.757%40%21%6%

1546

DAL-logoDallasNFC East9-7+33.450%34%17%4%

1539

MIN-logoMinnesotaNFC North9-7+20.443%28%14%3%

1534

SEA-logoSeattleNFC West8-8+17.143%29%13%3%

1529

ATL-logoAtlantaNFC South8-8+11.539%24%13%3%

1526

BAL-logoBaltimoreAFC North8-8+17.443%27%13%3%

1522

HOU-logoHoustonAFC South8-8+6.841%29%12%3%

1522

GB-logoGreen BayNFC North8-8+8.338%22%11%3%

1515

CLE-logoClevelandAFC North8-8+13.441%25%12%3%

1508

-3CAR-logoCarolinaNFC South8-8+7.137%22%11%2%

1506

JAX-logoJacksonvilleAFC South8-8+4.139%27%11%2%

1503

TEN-logoTennesseeAFC South8-8-3.037%26%10%2%

1493

SF-logoSan FranciscoNFC West8-8-8.132%21%9%2%

1474

IND-logoIndianapolisAFC South7-9-24.227%18%6%1%

1468

BUF-logoBuffaloAFC East7-9-18.527%14%7%1%

1459

DEN-logoDenverAFC West7-9-44.020%10%4%

September 3, 2019

Politics Podcast: What A 10-Person Democratic Debate Means

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Last Thursday, ABC News finalized the lineup for the third Democratic primary debates — only 10 candidates will participate, and they will all take the stage on the same night. In this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew debates whether the field has been winnowed to 10 and looks at the potential dynamic of the third Democratic primary debate now that there’s only one night of action.

Plus, in a round of “Good Use of Polling or Bad Use of Polling?” the team discusses a Monmouth University poll released last week that suggests there is essentially a three-way tie between Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. The pollster who conducted the survey described it as an “outlier.” Does that matter?

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen . The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

How To Handle An Outlier Poll

It’s pretty rare that a pollster calls his own survey an “outlier.” But that’s exactly what happened last week after a Monmouth University poll showed an approximate three-way tie between Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Joe Biden. Patrick Murray, director of the Monmouth University Polling Institute — an A-plus-rated pollster according to FiveThirtyEight — issued a statement describing his latest Democratic primary poll as an outlier that diverged from other recent polls of the race. (Indeed, there were quite a few national polls last week, and most of them continue to show Biden in front, with about 30 percent of the vote, and Sanders and Warren in the mid-to-high teens.)

But Murray doesn’t have any real reason to apologize. Outliers are a part of the business. In theory, 1 in 20 polls should fall outside the margin of error as a result of chance alone. One out of 20 might not sound like a lot, but by the time we get to the stretch run of the Democratic primary campaign in January, we’ll be getting literally dozens of new state and national polls every week. Inevitably, some of them are going to be outliers. Not to mention that the margin of error, which traditionally describes sampling error — what you get from surveying only a subset of voters rather than the whole population — is only one of several major sources of error in polls.

What should you do about these seeming outliers? If you’re a pollster, you should follow Monmouth’s lead and publish them!! In fact, printing the occasional expectations-defying result is a sign that a pollster is doing good and honest work. Plus, sometimes those “outliers” turn out to be right. Ann Selzer’s final poll of Iowa’s U.S. Senate race in 2014, which showed Republican Joni Ernst ahead by 7 percentage points over her Democratic opponent, might have looked like an outlier at the time, but it was the only one that came close to approximating her 8.5-point margin of victory there. The small handful of polls that showed Donald Trump leading in Pennsylvania in 2016 look pretty good too, even though most Pennsylanvia polls had Hillary Clinton leading.

In the long run, failure to publish results that pollsters presume to be outliers can yield far more embarrassment for the industry than the occasional funky-looking set of topline numbers. Suppressing outliers is a form of herding, a practice in which pollsters are influenced by other polls and strive to keep results within a narrow consensus. Herding makes polling averages less accurate, and it makes polling less objective. And more often than you’d think, it winds up being a case of the blind leading the blind. One recent example comes from Australia, where despite the Labor Party holding only a narrow and tenuous lead, pollsters declined to publish polls showing the conservatives narrowly ahead instead. The conservatives went on to a modest win, yielding a national controversy about polling that could have been avoided if the pollsters had trusted their numbers instead of the conventional wisdom.

About 99.99 percent of you reading this right now aren’t actually pollsters, though. So what’s my advice to you as news consumers when you encounter a poll that looks like an outlier?

To a first approximation, the best advice is to toss it into the average. Definitely do not assume that it’s the new normal. You don’t need to read dramatically headlined newspaper articles and watch breathless cable news segments about it. In a race with many polls, any one poll should rarely make all that much news. But you shouldn’t “throw out” the poll either. Instead, it should incrementally affect your priors. In the case of the Monmouth poll last week, for instance, you shouldn’t have assumed that the race had suddenly become a three-way tie, but you should have inched up your estimate of how well Sanders and Warren were doing compared with Biden.

For extra credit, pay attention to sample size. The Monmouth poll surveyed only 298 Democratic voters, which is small even by the standards of primary polls (which often survey fewer voters than general election polls do). Sample size is a complicated topic — as I mentioned, sampling error is only one source of polling error, and it’s not always the most important one. But as a rough rule of thumb, any poll with fewer than about 500 or 600 respondents is substantially more likely to have outlier-ish results because of sampling error than one that surveyed a larger number of voters. And polls with only 300 voters are especially likely to have issues.

So that’s the Polling 101 answer. When you see a poll that looks like an outlier, just throw it into the average. If you want, you can give some consideration to the sample size and the quality of the pollster.

But if you’ve read FiveThirtyEight for a while, you’ve probably heard that Polling 101 answer before. So I’m also going to give you the Polling 201 answer. But I want you to promise that you’ll abide by it fairly strictly, rather than interpret it too liberally. Pinky swear? OK, great. Then here goes:

If a poll shows a significant change in the race, you should tend to presume it’s an outlier unless it’s precipitated by a major news or campaign event.

Corollary: You should be much more open to the possibility that a poll reflects a real change if it’s among the first polls following a major news or campaign event.

What do I mean by a “major” news or campaign event? Some fairly specific types of things. When I made you pinky swear earlier, I was asking you to stick precisely to this list:

Debates.

Candidates entering or exiting the race, or clinching their nominations.

Primary and caucus results (e.g., the Iowa caucuses occur and that has knockoff effects on the next set of states).

The conventions.

The announcement of vice presidential candidates.

The final week of the campaign.

Spectacular, blockbuster news events that dominate the news cycle for a week or more. (There generally are only one or two of these per campaign cycle, if that many.)

The first five examples are fairly straightforward. The party conventions, for instance, almost always produce bounces, which then fade over the course of a few weeks. Debates can also produce shifts, which can range from permanent to (more often) ephemeral; Kamala Harris’s bounce faded after the first presidential debate, for instance. Be careful with the fifth category, vice presidential selections, since not many VPs are true game-changers. But an outside-of-the-box pick — i.e., Sarah Palin in 2008 — can sometimes produce a polling shift.

The sixth category, the end of the campaign, is less well-known as a source of polling movement, but the final days of the campaign can produce sharp shifts in the polls as undecided voters finally settle upon a candidate and as supporters of candidates who look like they can’t win (say, a Libertarian who is polling at 4 percent) hold their noses and pick one of the major contenders. Often, especially in primaries, this movement occurs fairly late — within the final week of the campaign or even the final 24 to 48 hours (in which case it may occur too late to show up in polls). There’s no guarantee that undecided voters will evenly divide themselves between the major candidates; in Wisconsin in 2016, for example, voters who decided in the final few days went almost 2-1 for Trump over Clinton.

So you generally should pay more attention to polling movement in the final few days of the campaign. Frankly, this is the time when you should panic a bit if the polls are moving away from your candidate.1

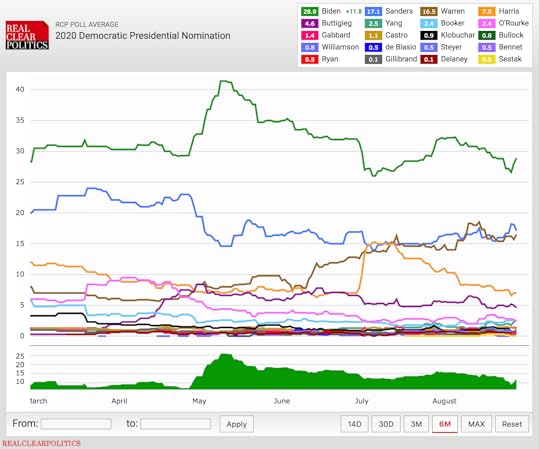

Essentially all of the polling shifts so far in the Democratic primary fall into one of the first two categories. Look at the RealClearPolitics average over the past six months, and the major changes you see are as follows:

A big bump for Biden after his entry to the race in late April, which faded over the course of several weeks.

A decline for Sanders coinciding with Biden’s entry into the race.

A big bounce for Harris, and a decline for Biden, after the first debate — both of which gradually reversed themselves.

An additional modest decline for Harris, and a modest increase for Warren, after the second debate.

A modest-sized bounce for Beto O’Rourke after he began his campaign.

And a bump for Pete Buttigieg in late April and early May.

So almost all of the sudden polling movement for the Democrats has been associated with debates or candidates launching their campaigns. The major exception is Buttigieg’s relatively abrupt surge, which may have been partly triggered by his town hall on CNN — certainly not an event that comes anywhere near qualifying under my seven categories above. Sharp polling movement sometimes does occur outside of these categories, but not very often. So you should err on the side of being conservative. It’s not that other sorts of news or campaign events can’t surprise you and change the polls. It’s just that you’d want to see several polls pointing toward a shift before you buy that they do.

The final category, blockbuster news stories, is the one where there’s the most room for subjectivity – and therefore the one you need to be most cautious about. Keep in mind that the overwhelming majority of news stories are less important to the campaign than they seem at the time. So if you’re the type of person whose life is caught up in the daily news cycle — or someone who works in politics for a living — you’re probably better off just ignoring this category entirely.

But stories that dominate the news cycle for a week or more and interrupt all other political coverage can change the polls, of course. To get a more objective idea of which stories qualify, you can look toward political aggregators like Memorandum, which archive their results to show which stories were dominating the news cycle on any given day. Many stories that people think of as political blockbusters really only last for two to three days.

What stories meet this threshold? In the 2018 midterms, probably only Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation. In 2016, the “Access Hollywood” tape and the Comey letter. In 2012, nothing, really. In 2008, the financial crisis was an ongoing story, but the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy on Sept. 15 touched off a series of acute events that reoriented the race. Events such as the publication of the Mueller report, Hurricane Katrina, the killing of Osama Bin Laden, the stock market crash of 1987 and the start of the Iraq War would also have qualified, had they occurred in the middle of election campaigns.

Let’s close with one more reason not to get all that excited about short-term polling swings. It’s one I’ve already alluded a couple times, but it probably can’t be emphasized enough. Polling shifts driven by campaign and news events often reverse themselves once the news cycle moves on to another topic. So even if the movement is real, it may be temporary. It will be highly relevant if the election is right around the corner, but less so if it’s several months away.

By contrast, gradual, long-term polling movement — of the sort that Warren has benefited from over the course of several months, for example — can be more durable. It’s entirely plausible that Warren has been gaining a point or two every few weeks not because of any specific news stories but just as a result of persuasion as voters become more familiar with her campaign. If you’re a Warren fan, that’s what should get you excited — and not the next outlier poll that comes along.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 730 followers